by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 30, 2018 | Colonialism & Conquest

Featured image: The Aguaprieta pipeline crosses the Yaqui River (Río Yaqui), the water source for the Yaqui, an indigenous tribe residing in the Yaqui Valley in Sonora, Mexico. Photo: Tomas Castelazo (CC). As far as one Yaqui community is concerned, the pipeline will never be completed.

by Gabriella Rutherford / Intercontinental Cry

In 2013, Enrique Peña Nieto’s government deregulated Mexico’s energy sector, opening it up to foreign investors for the first time 75 years. In what he called an “historic opportunity”, the Mexican President proclaimed “This profound reform can lift the standards of living for all Mexicans.”

But not everyone stands to see their quality of life materially improve from the deregulated sector. Such is the case for the Yaquí Peoples in Sonora state, Mexico, whose territory is currently home to an 84-kilometre stretch of natural gas pipeline.

The Aguaprieta (Agua Prieta) pipeline starts out in Arizona and stretches down 833km to Agua Prieta, in the northeastern corner of the Mexican state of Sonora—cutting through Yaqui territory along the way.

Once completed, the pipeline would also cross Yaqui River (Río Yaqui), the Yaqui’s main source of water.

More than a few Yaqui are adamant that they will see no benefits from the project. “The gas pipeline doesn’t help us, it only benefits businessmen, factory owners, but not the Yaqui” said Francisca Vásquez Molina, a Yaquí from the Loma de Bacúm community.

As with Keystone XL and Dakota Access pipelines, the Aguaprieta project comes with its own share of risks.

In addition to the considerable environmental impact that stems from the pipeline’s construction, the high methane content of natural gas could bring on disaster. Rodrigo Gonzalez, natural resources and environmental impact expert, maintains that in the event of a gas explosion all human, plant and animal life within a one-kilometre radius surrounding the explosion would be lost. Anyone within the second kilometre would risk second and third-degree burns.

In the community of Loma de Bacúm, the gas pipeline is just 700 m from houses. In nearby Estación Oroz, it is 591m from a primary school.

Gonzalez has pointed out that another viable route for the pipeline was initially considered by the company that could have avoided Yaqui territory altogether. He suggests this route was ultimately rejected to save costs. “At the beginning of the project, two routes were mooted. That which didn’t cross indigenous territory cost 400 million pesos whilst that which puts Yaquí lives at risk costs 100 million pesos.”

IEnova, the company behind the pipeline, has repeatedly made assurances that all due safety procedures have been followed in construction and that the risk of accidents is minimal but this has not been enough to assuage the fear or anger of everyone opposing the gas pipeline.

In a public statement last year, the group Solidaridad Tribu Yaquí said, “This is a people that say no to a megaproject of death, dispossession and destruction[…]These rich men don’t care about the life of one, two, or three people, much less if they are indigenous… [they] don’t care if the Yaqui culture is exterminated. What is important to these rich men is to conclude the work and pocket all the profits to be brought about by the appropriation of the Yaqui territory.”

Not all Yaquí communities are united in rejecting the gas pipeline, however. Indeed, of the eight Yaquí communities consulted, only the Loma de Bacúm community refused to give their consent to the project. The other seven communities chose to accept the compensation offered. This decision has sadly resulted in tensions between Loma de Bacúm and the other communities. Things reached a critical point in October 2016 where one Yaquí member died and thirty injured in a confrontation involving different Yaquí communities.

Seemingly alone in their struggle, the Loma de Bacúm Yaquí have consistently resisted the Aguaprieta pipeline. In April 2016, they successfully fought to be granted a moratorium on its construction. When, in 2017, it became clear that IEnova, would carry on regardless and that neither federal nor state or authorities could be counted on for support, the Loma de Bacúm community resorted to more drastic measures. On May 21, community members removed cables which had been laid down in the preliminary stages of the gas pipeline construction. Then, after another court ruling that IEnova should remove all infrastructure within 24 hours fell on deaf ears, on August 22 the community went ahead and cut a 25-foot section out of the live gas pipeline, despite the grave risks they ran in doing so. As a result of the community’s actions in August, IEnova was forced to cut off the gas flow in the area and it has remained out of service ever since.

The community has been accused of sabotage and vandalism to IEnova property but the community maintains that IEnova, a company owned by US-based Sempra Energy, is trespassing on their land and holds them responsible for all damage brought on by the construction of a pipeline to which they never consented.

In a video shared on Facebook, one community member explained “If you want to have us killed, there’s no problem. We’re not scared of that… We’re not scared of this company nor this project…All that the Yaquí tribe is asking for is that the law is upheld and that federal and state government respect it. If you want to have us killed, go ahead there’s no problem but we’ll defend our land and that is our right.”

In September 2017, a judge once again found in favour of the Yaquí community ruling that IEnova did not have the right to enter Yaquí territory to repair the gas pipeline. Whether this latest ruling will carry more weight with both local and state authorities than the previous ones remains to be seen.

For the time-being, the stand-off looks set to continue. Loma de Bacúm has made it clear it will not back down until the pipeline is removed or rerouted. “If they want to build a pipeline. that’s fine”, said community spokesperson Guadalupe Flores, “but it will not pass through here.” At the same time, IEnova refuses to accept that one small community can curtail their plan to use Yaquí territory in order to provide electricity to the Comisión Federal de Electricidad (CFE), the country’s largest electric utility. Nor does it seem willing to brazenly defy the court’s latest ruling, at least for the time-being.

The struggle in Loma de Bacúm echoes loudly among all Indigenous Peoples who are grappling to make sure the resource sector cannot run roughshod over human rights and environmental concerns; but it is perhaps loudest in Mexico. Since the new energy policy went into effect, four other pipeline projects have been suspended. Looking ahead, a “shale offensive” is now set to begin later this year should the PRI retain power in July, leading to a proliferation of similar conflicts.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 29, 2018 | Colonialism & Conquest

Featured image: Tomas was contacted between 2001 to 2003 and now lives in the Amazon region where one of the deadliest roads has been proposed. © David Hill/Survival International

by Survival International

Peru has approved a law that could devastate several uncontacted Amazon tribes.

The law declares “in the national interest” the construction of roads in the remote Ucayali region that borders Peru and Brazil.

The area lies inside the Uncontacted Frontier, home of the highest concentration of uncontacted tribes on Earth.

Several illegal roads that cut through uncontacted Indians’ lands have already been opened up. Thousands of illegal gold miners operate in the region, and have polluted dozens of rivers with mercury.

Uncontacted tribes face catastrophe unless their land is protected. They have the right to their land under Peruvian and international law.

Road building in the Amazon almost always leads to a devastating influx of settlers, loggers and ranchers.

Pope Francis, speaking from the region just days before the road law was passed, said: “Never before has there been a greater threat to indigenous peoples’ lands.

“We must break with the historical paradigm that sees the Amazon as an inexhaustible resource for other countries, without taking into account its inhabitants.”

Survival is calling on the Peruvian government to scrap road building plans inside the Uncontacted Frontier.

by DGR News Service | Jan 16, 2018 | Agriculture

Agriculture did not arise from need so much as it did from relative abundance. People stayed put, had the leisure to experiment with plants, lived in coastal zones where floods gave them the model of and denizens of disturbance, built up permanent settlements that increasingly created disturbance, and were able to support a higher birthrate because of sedentism.

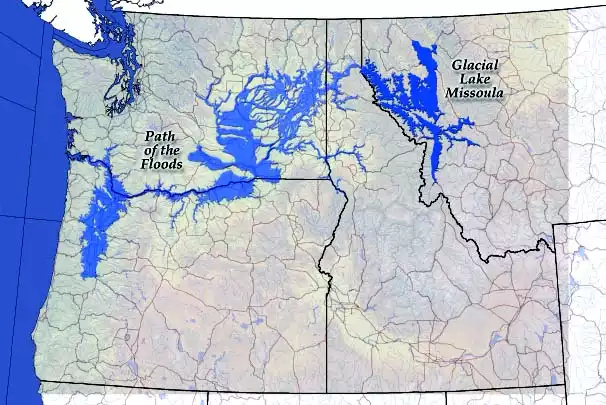

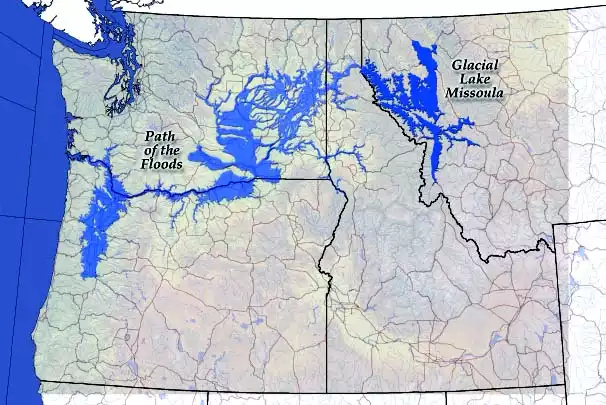

Area altered by Glacial Lake Missoula floods.

In the Middle East, this conjunction of forces occurred about ten thousand years ago, an interesting period from another angle. That date, the start of what is called the Neolithic Revolution, also coincides closely with the end of the last glaciation. As I write this, I sit in a spot that was then at the bottom of a huge lake. I live in a valley that held a lake famous to geologists, glacial Lake Missoula. The valley was formed by an ice dam that sat a couple hundred miles from here, and as the glaciers melted, the ice dam broke and re-formed many times, each time draining in a few hours a body of water the size of today’s Lake Michigan. That’s disturbance. The record of these floods can be clearly read today in giant washes and blowouts throughout the Columbia River basin in Washington State. Within the mouth of the Columbia River, several hundred miles downstream, is a twenty-five-mile-long peninsula made of sand washed downstream in these floods.

When the glaciers retreated, such catastrophic events were happening with increased frequency in floodplains around the world, especially in the Middle East. Juris Zarins of the University of Missouri has suggested that these massive disturbances and floods underlie the central Old Testament myths—the great flood, but also the Garden of Eden. Following a specific description in Genesis of the site of Eden, Zarins traces what he speculates are the four rivers of the Tigris and Euphrates system mentioned there. They would have converged in what is now the Persian Gulf, but during glaciation this would have been dry land. Further, it would have been an enormously productive plain, the sort of place that would have naturally produced an abundance of food without farming.

We call it the Garden of Eden, but it was not a garden; it was not cultivated. In fact, in Genesis, God is vengeful and specific in throwing Adam and Eve out of paradise; his punishment is that they will begin gardening. Says God, “In the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread, till thou return unto the ground.” God made good on his threat, and the record now shows just how angry he was. The children of Adam and Eve would hoe rows of corn. “To condemn all of humankind to a life of full-time farming, and in particular, arable farming, was a curse indeed,” writes Colin Tudge.

At about the same time that the shapes of seeds and of butchered sheep bones were changing, so were the shapes of villages and graves. Grave goods—tools, weapons, food, and comforts—were by then nothing new in the ritual of human burials. There is even some evidence, albeit controversial, that Neanderthals, an extinct branch of the family, buried some of their dead with flowers. Burial ritual was certainly a part of hunter-gatherer life, but the advent of agriculture brought changes.

For instance, one of the world’s richest collections of early agricultural settlements lies in the rice wetlands of China’s Hupei basin on the upper Yangtze River. The region was home to the Ta-hsi culture that domesticated rice between 5,500 and 6,000 years ago. Excavation of 208 graves there found many empty of anything but the dead, while others were elaborately endowed with goods. The same pattern emerges worldwide, one of the key indicators that, for the first time in human history, some people were more highly regarded than others, that agriculture conferred social status—or, more important, more goods—to a few people.

Some of early agriculture’s graves contained headless corpses, corresponding to archaeologists finding skulls in odd places and conditions. Skulls in the Middle East, for instance, were plastered to floors or into special pits. Some of the skulls had been altered to appear older. Archaeologists take this as a sign of ancestor worship, reasoning that because of the permanent occupation of land, it became important to establish a family’s claim on the land, and veneration of ancestors was a part of that process. So, too, was a rise in the importance of the family as opposed to the entire tribe, a switch that further evidence bears out.

Coincident with this was a shift in the villages themselves. Small clutches of simple huts gave way to larger collections, but with a qualitative change as well. Some houses became larger than others. At the same time, storage bins, granaries, began to appear. Cultivated grain, more so than any form of food humans had consumed before, was storable, not just through the year, but from year to year. It is hard to overstate the importance of this simple fact as it would play out through the centuries, later making possible such developments as, for instance, the provisioning of armies. But the immediate effect of storage was to make wealth possible. The big granaries were associated with the big houses and the graves whose headless skeletons were endowed with a full complement of grave goods.

Reconstruction of the tomb of King Midas; Museum of Anatolian Civilizations, Ankara, Turkey

The Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara, Turkey, holds one of the world’s most impressive assemblages of early agricultural remnants, including a reconstruction of a grave from a nearby city once ruled over by King Midas. He was a real guy, and his region was indeed known for its wealth in gold, taken from the Pactolus River. Yet the grave unearthed at Gordium (home of the Gordian knot) once thought to be Midas’s (but now identified as that of another in his line) was not full of gold. It was full of storage vessels for grain.

Of course to assert that agriculture’s grain made wealth possible is to assert that it also created poverty, a notion that counters the just-so story. The popular contention is that agriculture was an advance, progress that enriched humanity. Whatever the quality of our lives as hunter-gatherers, our numbers had become such that hunger forced this efficiency. Or so the story goes.

We have seen that agriculture in fact arose from abundance. More important, wealth, as distinct from abundance, is one of those dichotomous ideas only understood in the presence of its opposite, poverty. If we are to seek ways in which humans differ from all other species, this dichotomy would head the list. This is not to say that hunter-gatherers did not experience need, hard times, even starvation, just as all other animals do. We would be hard-pressed, however, to find communities of any social animal except modern humans in which an individual in the community has access to fifty, a hundred, a thousand times, or even twice as many resources as another. Yet such communities are the rule among post-agricultural humans.

Some social animals do indeed have hierarchy. Chickens and wolves have a pecking order, elk a herd bull, and bees a queen. Yet the very fact that we call the reproductive female in a hive of bees the “queen” is an imposition on animals of our ideas of hierarchy. The queen doesn’t rule, nor does she have access to forty times more food than she needs; nor does the alpha male wolf. Among elk, the herd bull is the first to starve during a rough winter, because he uses all his energy reserves during the fall rut.

The notion that agriculture created poverty is not an abstraction, but one borne out by the archaeological record. Forget the headless skeletons; they represent the minority, the richest people. A close examination of the many, buried with heads and without grave goods, makes a far more interesting platform for the question of why agriculture. Another approach to this question would be to walk the ancient settlement of Cahokia, just outside of St. Louis, Missouri, and ask: Why all these mounds?

Monk’s Mound in the ancient city of Cahokia

Cahokia was occupied until about six hundred years ago by the corn, squash, and bean culture of what is now the midwestern United States. There are a whole series of towns abandoned for no apparent reason just before the first Europeans arrived. “Mounds” understates the case, especially to those thinking the grand monuments of antiquity are part of the Old World’s lineage alone.

They are really dirt pyramids, a series of about a hundred, the largest rising close to a hundred feet high and nearly one thousand feet long on a side at its base. The only way to make such an enormous pile of dirt then was to carry it in baskets mounted on the backs of people, day in, day out, for lifetimes.

Much has been made of the creative forces that agriculture unleashed, and this is fair enough. Art, libraries, and literacy, are all agriculture’s legacy. But around the world, the first agricultural towns are marked by mounds, pyramids, temples, ziggurats, and great walls, all monuments reaching for the sky, the better to elevate the potentates in command of the construction. In each case, their command was a demonstration of enormous control over a huge force of stoop labor, often organized in one of civilization’s favorite institutions: slavery. The monuments are clear indication that, for a lot of people, life did not get better under agriculture, an observation particularly pronounced in Central America. There, the long steps leading to the pyramids’ tops are blood-stained, the elevation having been used for human sacrifice and the dramatic flinging of the victim down the long, steep steps.

Aside from its mounds, though, Cahokia is useful for considering the just-so story of agriculture’s emergence because it lies in the American Midwest, was relatively recent, and was largely contiguous and contemporaneous with surrounding hunter-gatherer territories. Like most agricultural societies, the mound builders coexisted with nomad hunters. Both groups were part of a broad trading network that brought copper from Michigan’s Upper Peninsula to what is now St. Louis, and seashells from the southeastern Atlantic Coast to Montana’s Sweet Grass Hills. This coexistence gives us a chance to compare lives by comparing skeletons.

We know from their remains that the farmers were smaller, the result of general deprivation and abuse. The women, especially, were smaller. The physiques that make up a modern women’s soccer or basketball team were simply unheard of among agricultural peoples, from farming’s beginnings to only very recent times. On average, we moderns (and only those of us in the richest parts of the world) are just beginning to regain the stature that we had as hunter-gatherers, who throughout time were on average as tall as North Americans are today.

Part of this decline stems from poor diet, especially for those who provided the stoop labor. Some of it is inherent in sedentism. Almost every locale’s soil and water are deficient in one mineral or another, a fact that was not a problem for nomadic hunter-gatherers. By moving about and taking food from a variety of niches, they balanced one locale’s deficiencies against another’s excess. This is also true for the early sedentary cities that relied on seafood. They didn’t move, but the fish did, bringing with them minerals from a wide range of places.

More important, however, grain’s availability as a cheap and easily stored package of carbohydrates made it the food of the poor. It allowed one to carry baskets of dirt day after day, but its lack of nutritional balance left people malnourished and stunted. The complex carbohydrates of grains are almost instantly reduced to sugars by digestion, sometimes simply from being chewed. The skeletal record of farming peoples shows this as tooth decay, an ailment nonexistent among contemporary hunter-gatherers.

That same grain, however, could be ground to soft, energy-rich gruels that had been unavailable to previous peoples, one of the more significant changes. The pelvises from female skeletons show evidence of having delivered more children than their counterparts in the wild. The availability of soft foods meant children could be weaned earlier—at one year instead of four. Women then could turn out the masses of children that would grow up to build pyramids and mounds.

‘The maid-servant that is behind the mill’. Grinding grain on a saddle quern; Egyptian statuette. (Drawing by Martin Watts).

They could also grind the grain. Theya Molleson of the Natural History Museum in London has found a common syndrome among these women’s skeletons: the toes and knees are bent and arthritic, and the lower back is deformed. She traces this to the saddle quern, a primitive stone rolling-pin mortar and pestle used for grinding grain. These particular deformities mark lives of days spent grinding.

The baseline against which these deformities and rotten teeth are measured is just as clear. For instance, paleopathologists who have studied skeletal remains of hunter-gatherers living in the diverse and productive systems of what is now central California found them “so healthy it is somewhat discouraging to work with them.” As many societies turned to agriculture in the early days, they did so only to supplement or stabilize a basic existence of hunting and gathering. Among these people, paleopathologists found few of the difficulties associated with people who are exclusively agricultural.

The marks of agriculture on subsequent groups, however, are unmistakable. In his book The Day Before America, William H. MacLeish summarizes the record of a group in the Ohio River valley: “Almost one-fifth of the Fort Ancient settlement dies during weaning. Infants suffer growth arrests indicating that at birth their mothers were undernourished and unable to nurse well. One out of a hundred individuals lives beyond fifty. Teeth rot. Iron deficiency, anemia, is widespread, as is an infection produced by treponemata” (a genus of bacteria that causes yaws and syphilis).

The inclusion here of communicable diseases is significant and consistent with the record worldwide. Sedentary people were often packed into dense, stable villages where diseases could get a foothold, particularly those diseases related to sanitation, like cholera and tuberculosis. Just as important, the early farmers domesticated livestock, which became sources of many of our major infectious diseases, like smallpox, influenza, measles, and the plague.

Summarizing evidence from around the world, researcher Mark Cohen ticks off a list of diseases and conditions evident in skeletal and fecal remains of early farmers but absent among hunter-gatherers. The list includes malnutrition, osteomyelitis and periostitis (bone infections), intestinal parasites, yaws, syphilis, leprosy, tuberculosis, anemia (from poor diet as well as from hookworms), rickets in children, osteomalacia in adults, retarded childhood growth, and short stature among adults.

Such ills were obviously hard on the individual, as were the slavery, poverty, and oppression agriculture seems to have brought with it. And all of this seems to take us further from answering the question: Why agriculture? Remember, though, that this is an evolutionary question.

The question of agriculture can easily get tangled in values, as it should. Farming was the fundamental determinant of the quality (or lack thereof) of human life for the past ten thousand years. It made us, and makes us, what we are. We have long assumed that this fundamental technology was progress, and that progress implies an improvement in the human condition. Yet framing the question this way has no meaning. Biology and evolution don’t care very much about quality of life. What counts is persistence, or, more appropriately, endurance—a better word in that it layers meanings: to endure as a species, we endure some hardships. What counts to biology is a species’ success, defined as its members living long enough to reproduce robustly, to be fruitful and multiply. Clearly, farming abetted that process. We learned to grow food in dense, portable packages, so our societies could become dense and portable.

We were not alone in this. Estimates say our species alone uses forty percent of the primary productivity of the planet. That is, of all the solar energy striking the surface, almost half flows through our food chain—almost half to feed a single species among millions extant. That, however, overstates the case, in that a select few plants (wheat, rice, and corn especially) and a select few domestic animals (cattle, chickens, goats, and sheep for the most part, and, as a special case, dogs) are also the beneficiaries of human ubiquity. We and these species are a coalition, and the coalition as a whole plays by the biological rules. Six or so thousand years ago, some wild sheep and goats cut a deal in the Zagros Mountains of what is now Turkey. A few began hanging around the by-then longtime wheat farmers and barley growers of the Middle East. The animals’ bodies, their skeletal remains, show this transition much as the human bones do: they are smaller, more diseased, more battered and beaten, but they are more numerous, and that’s what counts. By cutting this deal, the animals suffer the abuses of society, but today they are among the most numerous and widespread species on the planet, along with us and our food crops.

Simultaneously, a whole second order of creatures—freeloaders and parasites—were cutting the same deal. Our crowding and our proximity to a few species of domestic animals gave microorganisms the laboratory they needed to develop more virulent, more enduring, and more portable configurations, and they are with us in this way today, also fruitful and multiplied. At the same time, the ecological disturbance that was a precondition of agriculture opened an ever broadening niche, not just for our domestic crops, but for a slew of wild plants that had been relegated to a narrow range. Domesticated cereals, squashes, and chenopods are not the only plants adapted to catastrophes like flood and fire. There is a range of early succession colonizers, a class of life we commonly call weeds. They are an integral part of the coalition and, as we shall see, almost as important as our evolved diseases in allowing the coalition to spread.

In all of this we can see the phenomenon that biologists call coevolution. In the waxing and waning of species that characterizes all of biological time, change does not occur in isolation. Species changeto respond to change in other species. Coalitions form. Domestication was such a change. Human selection pressure on crops and animals can be read so clearly in the archaeological record because the archaeological record is a reflection of the genetic record. We re-formed the genome of the plants just as surely as (and more significantly than) any of the most Frankensteinian projects of genetic manipulation plotted by today’s biotechnologists. The shape of life changed.

Can the same be said of the domesticates’ effects on us? Did they reengineer humans? After all, we can see the change in the human body clearly written in the archaeological record. Or at least we can if for a second we allow ourselves to lapse into Lamarckianism. In 1809, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck set forth a pre-Darwinian theory of evolution that suggested that environmentally conditioned changes in an individual would be inherited by the subsequent generations. That is, to put it in modern terms, conditioning changes the genome. This would imply that a spaniel with a docked tail would spawn stub-tailed progeny, or that a weightlifter’s children would emerge from the womb with bulging biceps. We know this is false. (Mostly we know—there are some valid neo-Lamarckian arguments.) Many of the changes in humans I’ve cited above are in fact responses to the changing conditions brought on by agriculture: the malnutrition, disease, and deformed bones were not inherited, but battered into place with each new generation.

These changes are the result of cultural, not biological, evolution. Do not discount such changes as unimportant; culture evolves as surely—and as inexorably and anarchically—as do our bodies, and it does indeed have enormous effect on our quality of life. Poverty is a direct result of cultural evolution, and despite ten thousand years of railing and warning against it, the result is still, as Christ predicted, that the poor are always with us.

By bringing this distinction between biological and cultural evolution into play, I mean to set a higher hurdle for the argument that agriculture was a powerful enough leap in technology to be read in our genome. Agriculture was social evolution, but at the same time it also instigated genuine biological evolution in humans.

Take the example of sickle-cell anemia. As with many inherited diseases, the occurrence of sickle-cell anemia varies by ethnic group, but it is particularly common in those from Africa. The explanation for this was a long time coming, until someone finally figured out that what we regard as a disease is sometimes an adaptation, a result of natural selection. Sickle-cell anemia confers resistance to malaria, which is to say, if one lives in an area infested with malaria, it is an advantage, not a disease; it is an aid to living and reproducing and passing on that gene for the condition. The other piece of this puzzle emerged only very recently. In 2001, Dr. Sarah A. Tishkoff, a population geneticist at the University of Maryland, reported the results of analysis of human DNA and of the gene for sickle-cell anemia. The gene variant common in Africa arose roughly eight thousand years ago, and some four thousand years ago in the case of a second version of the gene common among peoples of the Mediterranean, India, and North Africa. This revelation came as something of a shock for people who thought malaria to be a more ancient disease. Its origins coincide nicely with those of agriculture, which scientists say is no accident. The disturbance—clearing tropical forests first in Africa, and later in those other regions—created precisely the sort of conditions in which mosquitoes thrive. Thus, malaria is an agricultural disease.

There are similar and simpler arguments to be made about lactose intolerance, an inherited condition mostly present among ethnic groups without a long agricultural history. People who had no cows, goats, or horses had no milk in their adult diet. Our bodies had to evolve to produce the enzymes to digest it, a trick passed on in genes. Lactose is a sugar, and leads to a range of diet-related intolerances. The same sort of argument emerges with obesity and sugar diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and even alcoholism. All are widespread in hunter-gatherer groups suddenly switched to an agricultural diet of dense carbohydrates and sugars. The ability of some people to survive these radical foods evolved only slowly through drastic selection pressure.

All of this points to coevolution, which is the deepest answer to the question of why agriculture. The question implies motive, which is to say we chose agriculture because it was somehow better. There are indeed arguments that it was. Yes, life might have gotten harder in the short term, but storable food provided some measure of long-term security, so there was a bargain of sorts. And while the skeletal remains show a harsh life for the masses, the wealthy were clearly better off and had access to resources, luxury, and security far beyond anything a hunter-gatherer ancestor could imagine. Yet we can raise all the counterarguments and suggest they at least balance the plusses, a contention bolstered by modern experience. That is, we have no clear examples of colonized hunter-gatherers who willingly, peacefully converted to farming. Most went as slaves; most were dragged kicking and screaming, or just plain died.

The coevolution argument provokes a clearer answer to the question: Why agriculture? We are speaking of domestication, a special kind of evolution we also call taming. We tamed the plants and animals so they could serve our ends, a sort of biological slavery, but if coevolution is true, the converse must also be true. The plants and animals tamed us. In biological terms, wheat is successful; its success is built on the fact that it tamed humans. Wheat altered us, altered our genome, to use us.

—

This is an excerpt from Against the Grain by Richard Manning

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 13, 2018 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction

Editor’s note: On January 8, 2018, a federal judge dismissed US government’s criminal charges against Nevada rancher Cliven Bundy, two of his sons and another man linked to militia groups, over procedural errors made by the prosecution. This is a history of the Bundy grazing allotment.

by Center for Biological Diversity

• The Bundy family began grazing on federal public lands near Gold Butte, Nevada, in 1954 – lands located in the recently designated Gold Butte National Monument – some of the driest and most fragile desert in North America.

• In 1973 the Bundys were granted their first federal grazing permit. Given the aridity and fragility of the desert, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) issued a permit for grazing in this ephemeral range, which is subject to environmental and other conditions. Ephemeral range in the southwest desert region does not consistently produce forage for grazing.

• In 1989 the desert tortoise was granted protection under the federal Endangered Species Act because of widespread destruction of its fragile desert habitat by livestock grazing, urbanization and other factors.

• In 1991, the U.S. and Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) issued a draft Biological Opinion (BO) governing the management of desert tortoise habitat. The BLM developed a timetable to meet its requirements and shared the requirements and timetable with permittees, including Cliven Bundy, whose cattle grazed in tortoise habitat. The BLM requested and FWS then agreed to delay implementation of the BO until 1993.

• On February 26th, 1993, Cliven Bundy sent two “Administrative Notices of Intent” to the BLM asserting that the BLM has no legal jurisdiction over federal public lands, and stating his intent to graze cattle, “pursuant to my vested grazing rights.” Bundy stopped paying his grazing fees after February 28th of 1993.

• The BLM sent Bundy a notice that his request for a grazing application had not been received and requested that he re-submit within one week or BLM action would be taken.

• On July 13, 1993, BLM sent Bundy a Trespass Notice and Order to Remove which set a timeline for cattle removal given his non-payment of fees. Later BLM extended the timetable at Bundy’s request.

• On September 30, 1993, the Nevada State BLM Director requested injunctive relief—action from the court—to address Bundy’s unlawful cattle grazing.

• On January 24, 1994 BLM tried to deliver to Bundy a proposed decision to cancel his permit, request payment of trespass damages, and order the removal of trespass livestock. When BLM delivered the notice, Bundy’s son tore up the document. The torn document was recovered and used as evidence of illegal grazing by the BLM in court.

• On March 3, 1994, Cliven Bundy, given his refusal to recognize federal authority to own and administer federal lands, sent payment for his grazing permit to Clark County instead of the BLM. The county refused Bundy’s payment for lack of jurisdiction.

• In 1998, the U.S. Attorney filed suit requesting that the federal district court order Bundy to remove his cattle and pay outstanding grazing fees and fines totaling now more than $150,000.

• In October 1998, the BLM approved a new Resource Management Plan for the Las Vegas Field Office. The plan allowed for the closure of grazing allotments in critical tortoise habitats, including the Bunkerville allotment.

• On November 3, 1998, United States District Judge Johnnie Rawlinson permanently enjoined Bundy from grazing his livestock within the Bunkerville allotment. Rawlinson assessed fines against Bundy, affirmed federal authority over federal land, and wrote that “[t]he government has shown commendable restraint in allowing this trespass to continue for so long without impounding Bundy’s livestock.” Cite.

• Bundy refused to comply with the order. He filed an emergency motion for stay to try and halt the court ruling while he appealed the case to the Ninth Circuit Court.

• On May 14th, 1999, the Ninth Circuit Court denied Bundy’s appeal and upheld the district court decision ordering the removal of Bundy’s cattle from the Bunkerville allotment. Cite.

• On September 17th, 1999, after Bundy refused to comply with the court’s earlier orders, the Federal District Court again ordered Bundy to comply with the earlier permanent injunction and assessed additional fines.

• In December 1998, in order to mitigate harm to desert tortoise from urban sprawl, Clark County purchased the federal grazing permit to the Bunkerville Allotment for $375,000. The county retired the allotment to protect the desert tortoise. With the ongoing trespass cattle, Clark County inquired as to the rights of Cliven Bundy to be on the allotment. In a July, 2002 memo the BLM stated that the “Mr. Bundy has no right to occupy or graze livestock in the Bunkerville grazing allotment. Two court decisions, one in Federal District Court and another in the Circuit Court of Appeals,

fully supports our positions.”

• On April 2, 2008 the BLM sent Bundy a notice of cancellation, cancelling Bundy’s range improvement permit and a cooperative agreement. The notice called for the removal of his range improvements, such as gates and water infrastructure.

Cattle have been grazing in the vast Gold Butte area since an armed standoff between the government and self-styled militia in 2014.

Kirk Siegler/NPR

• On May 9, 2008 Cliven Bundy sent a document entitled “Constructive Notice” to local, county, state, and federal officials, including the BLM. It claimed that Bundy had rights to graze on the Bunkerville Allotment; it called on state and county officials to protect those rights from the federal government; and it responded to the BLM’s April 2 Notice of Cancellation by saying he has not ignored it, and that he will do whatever it takes to protect grazing rights.

• In 2011, BLM sent Bundy a cease-and-desist order and notice of intent to roundup his trespass cattle.

• In 2012, BLM aerial surveys estimated about 1000 trespass cattle remained.

• In April 2012, the BLM at the last moment canceled plans to roundup trespass cattle to ensure the safety of people involved in the roundup after Cliven Bundy made violent threats against BLM.

• On July 2013, U.S. District Court of Nevada again affirmed that Bundy has no legal rights to graze cattle. It ordered Bundy to remove his cattle from public lands within 45 days and authorized the U.S. government to seize and impound any remaining cattle thereafter. Cite.

• In October 2013, after an appeal by Bundy, the federal court again affirmed that Bundy had no legal right to graze cattle on federal public lands. The court ordered the removal of cattle within 45 days and ordered Bundy not to interfere with the round-up. Cite.

• In March 2014, the BLM issued a notice of intent to impound Bundy’s trespass cattle and closed the area to the public for the duration of the action.

• On April 5, 2014 the roundup began.

• On April 9, 2014 heavily armed militia from across the U.S. converged on the Bundy ranch to confront federal officials conducting the roundup.

• On April 12, about 300 cattle that had been rounded up and held in a corral were released by the BLM after the heavily armed militia confronted and aimed rifles at federal agents. The BLM canceled the roundup out of safety concerns for employees and the public.

• In April 2015, Bundy held a weekend barbecue and “Liberty Celebration” to mark the one-year anniversary of the standoff.

• In June, 2015, shots were fired near public land surveyors working in the Gold Butte area. BLM orders all employees to stay away from Gold Butte.

• On Feb 11, 2016, Cliven Bundy was arrested at the Portland, Oregon airport on his way to support his son’s paramilitary occupation of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in Oregon.

• As of February, 2017, Bundy’s trespass cattle continue to graze illegally on federal public lands near Gold Butte.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 12, 2018 | Agriculture, Building Alternatives

by Frances Moore Lappé / Local Futures

People yearn for alternatives to industrial agriculture, but they are worried. They see large-scale operations relying on corporate-supplied chemical inputs as the only high-productivity farming model. Another approach might be kinder to the environment and less risky for consumers, but, they assume, it would not be up to the task of providing all the food needed by our still-growing global population.

Contrary to such assumptions, there is ample evidence that an alternative approach—organic agriculture, or more broadly “agroecology”—is actually the only way to ensure that all people have access to sufficient, healthful food. Inefficiency and ecological destruction are built into the industrial model. But, beyond that, our ability to meet the world’s needs is only partially determined by what quantities are produced in fields, pastures, and waterways. Wider societal rules and norms ultimately shape whether any given quantity of food produced is actually used to meet humanity’s needs. In many ways, how we grow food determines who can eat and who cannot—no matter how much we produce. Solving our multiple food crises thus requires a systems approach in which citizens around the world remake our understanding and practice of democracy.

Today, the world produces—mostly from low-input, smallholder farms—more than enough food: 2,900 calories per person per day. Per capita food availability has continued to expand despite ongoing population growth. This ample supply of food, moreover, comprises only what is left over after about half of all grain is either fed to livestock or used for industrial purposes, such as agrofuels.1

Despite this abundance, 800 million people worldwide suffer from long-term caloric deficiencies. One in four children under five is deemed stunted—a condition, often bringing lifelong health challenges, that results from poor nutrition and an inability to absorb nutrients. Two billion people are deficient in at least one nutrient essential for health, with iron deficiency alone implicated in one in five maternal deaths.2

The total supply of food alone actually says little about whether the world’s people are able to meet their nutritional needs. We need to ask why the industrial model leaves so many behind, and then determine what questions we should be asking to lead us toward solutions to the global food crisis.

Vast, Hidden Inefficiencies

The industrial model of agriculture—defined here by its capital intensity and dependence on purchased inputs of seeds, fertilizer, and pesticides—creates multiple unappreciated sources of inefficiency. Economic forces are a major contributor here: the industrial model operates within what are commonly called “free market economies,” in which enterprise is driven by one central goal, namely, securing the highest immediate return to existing wealth. This leads inevitably to a greater concentration of wealth and, in turn, to greater concentration of the capacity to control market demand within the food system.

Moreover, economically and geographically concentrated production, requiring lengthy supply chains and involving the corporate culling of cosmetically blemished foods, leads to massive outright waste: more than 40 percent of food grown for human consumption in the United States never makes it into the mouths of its population.3

The underlying reason industrial agriculture cannot meet humanity’s food needs is that its system logic is one of disassociated parts, not interacting elements. It is thus unable to register its own self-destructive impacts on nature’s regenerative processes. Industrial agriculture, therefore, is a dead end.

Consider the current use of water in agriculture. About 40 percent of the world’s food depends on irrigation, which draws largely from stores of underground water, called aquifers, which make up 30 percent of the world’s freshwater. Unfortunately, groundwater is being rapidly depleted worldwide. In the United States, the Ogallala Aquifer—one of the world’s largest underground bodies of water—spans eight states in the High Plains and supplies almost one third of the groundwater used for irrigation in the entire country. Scientists warn that within the next thirty years, over one-third of the southern High Plains region will be unable to support irrigation. If today’s trends continue, about 70 percent of the Ogallala groundwater in the state of Kansas could be depleted by the year 2060.4

Industrial agriculture also depends on massive phosphorus fertilizer application—another dead end on the horizon. Almost 75 percent of the world’s reserve of phosphate rock, mined to supply industrial agriculture, is in an area of northern Africa centered in Morocco and Western Sahara. Since the mid-twentieth century, humanity has extracted this “fossil” resource, processed it using climate-harming fossil fuels, spread four times more of it on the soil than occurs naturally, and then failed to recycle the excess. Much of this phosphate escapes from farm fields, ending up in ocean sediment where it remains unavailable to humans. Within this century, the industrial trajectory will lead to “peak phosphorus”—the point at which extraction costs are so high, and prices out of reach for so many farmers, that global phosphorus production begins to decline.5

Beyond depletion of specific nutrients, the loss of soil itself is another looming crisis for agriculture. Worldwide, soil is eroding at a rate ten to forty times faster than it is being formed. To put this in visual terms, each year, enough soil is washed and blown from fields globally to fill roughly four pickup trucks for every human being on earth.6

The industrial model of farming is not a viable path to meeting humanity’s food needs for yet another reason: it contributes nearly 20 percent of all anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, even more than the transportation sector. The most significant emissions from agriculture are carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide. Carbon dioxide is released in deforestation and subsequent burning, mostly in order to grow feed, as well as from decaying plants. Methane is released by ruminant livestock, mainly via their flatulence and belching, as well as by manure and in rice paddy cultivation. Nitrous oxide is released largely by manure and manufactured fertilizers. Although carbon dioxide receives most of the attention, methane and nitrous oxide are also serious. Over a hundred-year period, methane is, molecule for molecule, 34 times more potent as a heat-trapping gas, and nitrous oxide about 300 times, than carbon dioxide.7

Our food system also increasingly involves transportation, processing, packaging, refrigeration, storage, wholesale and retail operations, and waste management—all of which emit greenhouses gases. Accounting for these impacts, the total food system’s contribution to global greenhouse gas emissions, from land to landfill, could be as high as 29 percent. Most startlingly, emissions from food and agriculture are growing so fast that, if they continue to increase at the current rate, they alone could use up the safe budget for all greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.8

These dire drawbacks are mere symptoms. They flow from the internal logic of the model itself. The reason that industrial agriculture cannot meet the world’s needs is that the structural forces driving it are misaligned with nature, including human nature.

Social history offers clear evidence that concentrated power tends to elicit the worst in human behavior. Whether for bullies in the playground or autocrats in government, concentrated power is associated with callousness and even brutality not in a few of us, but in most of us.9 The system logic of industrial agriculture, which concentrates social power, is thus itself a huge risk for human well-being. At every stage, the big become bigger, and farmers become ever-more dependent on ever-fewer suppliers, losing power and the ability to direct their own lives.

The seed market, for example, has moved from a competitive arena of small, family-owned firms to an oligopoly in which just three companies—Monsanto, DuPont, and Syngenta—control over half of the global proprietary seed market. Worldwide, from 1996 to 2008, a handful of corporations absorbed more than two hundred smaller independent companies, driving the price of seeds and other inputs higher to the point where their costs for poor farmers in southern India now make up almost half of production costs.10 And the cost in real terms per acre for users of bio-engineered crops dominated by one corporation, Monsanto, tripled between 1996 and 2013.

Not only does the industrial model direct resources into inefficient and destructive uses, but it also feeds the very root of hunger itself: the concentration of social power. This results in the sad irony that small-scale farmers—those with fewer than five acres—control 84 percent of the world’s farms and produce most of the food by value, yet control just 12 percent of the farmland and make up the majority of the world’s hungry.11

The industrial model also fails to address the relationship between food production and human nutrition. Driven to seek the highest possible immediate financial returns, farmers and agricultural companies are increasingly moving toward monocultures of low-nutrition crops such as corn—the dominant US crop—that are often processed into empty-calorie “food products.” As a result, from 1990 to 2010, growth in unhealthy eating patterns outpaced dietary improvements in most parts of the world, including the poorer regions. Most of the key causes of non-communicable diseases are now diet-related, and by 2020, such diseases are predicted to account for nearly 75 percent of all deaths worldwide.12

A Better Alternative

What model of farming can end nutritional deprivation while restoring and conserving food-growing resources for our progeny? The answer lies in the emergent model of agroecology, often called “organic” or ecological agriculture. Hearing these terms, many people imagine simply a set of farming practices that forgo purchased inputs, relying instead on beneficial biological interactions among plants, microbes, and other organisms. However, agroecology is much more than that. The term as it is used here suggests a model of farming based on the assumption that within any dimension of life, the organization of relationships within the whole system determines the outcomes. The model reflects a shift from a disassociated to a relational way of thinking arising across many fields within both the physical and social sciences. This approach to farming is coming to life in the ever-growing numbers of farmers and agricultural scientists worldwide who reject the narrow productivist view embodied in the industrial model.

Recent studies have dispelled the fear that an ecological alternative to the industrial model would fail to produce the volume of food for which the industrial model is prized. In 2006, a seminal study in the Global South compared yields in 198 projects in 55 countries and found that ecologically attuned farming increased crop yields by an average of almost 80 percent. A 2007 University of Michigan global study concluded that organic farming could support the current human population, and expected increases without expanding farmed land. Then, in 2009, came a striking endorsement of ecological farming by fifty-nine governments and agencies, including the World Bank, in a report painstakingly prepared over four years by four hundred scientists urging support for “biological substitutes for industrial chemicals or fossil fuels.”13 Such findings should ease concerns that ecologically aligned farming cannot produce sufficient food, especially given its potential productivity in the Global South, where such farming practices are most common.

Ecological agriculture, unlike the industrial model, does not inherently concentrate power. Instead, as an evolving practice of growing food within communities, it disperses and creates power, and can enhance the dignity, knowledge, and the capacities of all involved. Agroecology can thereby address the powerlessness that lies at the root of hunger.

Applying such a systems approach to farming unites ecological science with time-tested traditional wisdom rooted in farmers’ ongoing experiences. Agroecology also includes a social and politically engaged movement of farmers, growing from and rooted in distinct cultures worldwide. As such, it cannot be reduced to a specific formula, but rather represents a range of integrated practices, adapted and developed in response to each farm’s specific ecological niche. It weaves together traditional knowledge and ongoing scientific breakthroughs based on the integrative science of ecology. By progressively eliminating all or most chemical fertilizers and pesticides, agroecological farmers free themselves—and, therefore, all of us—from reliance on climate-disrupting, finite fossil fuels, as well as from other purchased inputs that pose environmental and health hazards.

In another positive social ripple, agroecology is especially beneficial to women farmers. In many areas, particularly in Africa, nearly half or more of farmers are women, but too often they lack access to credit.14 Agroecology—which eliminates the need for credit to buy synthetic inputs—can make a significant difference for them.

Agroecological practices also enhance local economies, as profits on farmers’ purchases no longer seep away to corporate centers elsewhere. After switching to practices that do not rely on purchased chemical inputs, farmers in the Global South commonly make natural pesticides using local ingredients—mixtures of neem tree extract, chili, and garlic in southern India, for example. Local farmers purchase women’s homemade alternatives and keep the money circulating within their community, benefiting all.15

Besides these quantifiable gains, farmers’ confidence and dignity are also enhanced through agroecology. Its practices rely on farmers’ judgments based on their expanding knowledge of their land and its potential. Success depends on farmers’ solving their own problems, not on following instructions from commercial fertilizer, pesticide, and seed companies. Developing better farming methods via continual learning, farmers also discover the value of collaborative working relationships. Freed from dependency on purchased inputs, they are more apt to turn to neighbors—sharing seed varieties and experiences of what works and what does not for practices like composting or natural pest control. These relationships encourage further experimentation for ongoing improvement. Sometimes, they foster collaboration beyond the fields as well—such as in launching marketing and processing cooperatives that keep more of the financial returns in the hands of farmers.

Going beyond such localized collaboration, agroecological farmers are also building a global movement. La Via Campesina, whose member organizations represent 200 million farmers, fights for “food sovereignty,” which its participants define as the “right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods.” This approach puts those who produce, distribute, and consume food—rather than markets and corporations—at the heart of food systems and policies, and defends the interests and inclusion of the next generation.

Once citizens come to appreciate that the industrial agriculture model is a dead end, the challenge becomes strengthening democratic accountability in order to shift public resources away from it. Today, those subsidies are huge: by one estimate, almost half a trillion tax dollars in OECD countries, plus Brazil, China, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Russia, South Africa, and Ukraine.16 Imagine the transformative impact if a significant share of those subsidies began helping farmers’ transition to agroecological farming.

Any accurate appraisal of the viability of a more ecologically attuned agriculture must let go of the idea that the food system is already so globalized and corporate-dominated that it is too late to scale up a relational, power-dispersing model of farming. As noted earlier, more than three-quarters of all food grown does not cross borders. Instead, in the Global South, the number of small farms is growing, and small farmers produce 80 percent of what is consumed in Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa.17

The Right Path

When we address the question of how to feed the world, we need to think relationally—linking current modes of production with our future capacities to produce, and linking farm output with the ability of all people to meet their need to have nutritious food and to live in dignity. Agroecology, understood as a set of farming practices aligned with nature and embedded in more balanced power relationships, from the village level upward, is thus superior to the industrial model. This emergent relational model offers the promise of an ample supply of nutritious food needed now and in the future, and more equitable access to it.

Reframing concerns about inadequate supply is only the first step toward necessary change. The essential questions about whether humanity can feed itself well are social—or, more precisely, political. Can we remake our understanding and practice of democracy so that citizens realize and assume their capacity for self-governance, beginning with the removal of the influence of concentrated wealth on our political systems?

Democratic governance—accountable to citizens, not to private wealth—makes possible the necessary public debate and rule-making to re-embed market mechanisms within democratic values and sound science. Only with this foundation can societies explore how best to protect food-producing resources—soil, nutrients, water—that the industrial model is now destroying. Only then can societies decide how nutritious food, distributed largely as a market commodity, can also be protected as a basic human right.

This post is adapted from an essay originally written for the Great Transition Initiative.

Featured image: TompkinsConservation.org

Endnotes

1. Food and Agriculture Division of the United Nations, Statistics Division, “2013 Food Balance Sheets for 42 Selected Countries (and Updated Regional Aggregates),” accessed March 1, 2015, http://faostat3.fao.org/download/FB/FBS/E; Paul West et al., “Leverage Points for Improving Global Food Security and the Environment,” Science 345, no. 6194 (July 2014): 326; Food and Agriculture Organization, Food Outlook: Biannual Report on Global Food Markets (Rome: FAO, 2013), http://fao.org/docrep/018/al999e/al999e.pdf.

2. FAO, The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2015: Meeting the 2015 International Hunger Targets: Taking Stock of Uneven Progress (Rome: FAO, 2015), 8, 44, http://fao.org/3/a-i4646e.pdf; World Health Organization, Childhood Stunting: Context, Causes, Consequences (Geneva: WHO, 2013), http://www.who.int/nutrition/events/2013_ChildhoodStunting_colloquium_14Oct_ConceptualFramework

_colour.pdf?ua=1; FAO, The State of Food and Agriculture 2013: Food Systems for Better Nutrition (Rome: FAO, 2013), ix, http://fao.org/docrep/018/i3300e/i3300e.pdf.

3. Vaclav Smil, “Nitrogen in Crop Production: An Account of Global Flows,” Global Geochemical Cycles 13, no. 2 (1999): 647; Dana Gunders, Wasted: How America Is Losing Up to 40% of Its Food from Farm to Fork to Landfill (Washington, DC: Natural Resources Defense Council, 2012), http://www.nrdc.org/food/files/wasted-food-IP.pdf.

4. United Nations Environment Programme, Groundwater and Its Susceptibility to Degradation: A Global Assessment of the Problem and Options for Management (Nairobi: UNEP, 2003), http://www.unep.org/dewa/Portals/67/pdf/Groundwater_Prelims_SCREEN.pdf; Bridget Scanlon et al., “Groundwater Depletion and Sustainability of Irrigation in the US High Plains and Central Valley,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109, no. 24 (June 2012): 9320; David Steward et al., “Tapping Unsustainable Groundwater Stores for Agricultural Production in the High Plains Aquifer of Kansas, Projections to 2110,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110, no. 37 (September 2013): E3477.

5. Dana Cordell and Stuart White, “Life’s Bottleneck: Sustaining the World’s Phosphorus for a Food Secure Future,” Annual Review Environment and Resources 39 (October 2014): 163, 168, 172.

6. David Pimentel, “Soil Erosion: A Food and Environmental Threat,” Journal of the Environment, Development and Sustainability 8 (February 2006): 119. This calculation assumes that a full-bed pickup truck can hold 2.5 cubic yards of soil, that one cubic yard of soil weighs approximately 2,200 pounds, and that world population is 7.2 billion people.

7. FAO, “Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Agriculture, Forestry, and Other Land Use,” March 2014, http://fao.org/resources/ infographics/infographics-details/en/c/218650/; Gunnar Myhre et al., “Chapter 8: Anthropogenic and Natural Radiative Forcing,” in Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis (Geneva: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2013), 714, http://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar5/wg1/WG1AR5_Chapter08_FINAL.pdf.

8. Sonja Vermeulen, Bruce Campbell, and John Ingram, “Climate Change and Food Systems,” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 37 (November 2012): 195; Bojana Bajželj et al., “Importance of Food-Demand Management for Climate Mitigation,” Nature Climate Change 4 (August 2014): 924–929.

9. Philip Zimbardo, The Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn Evil (New York: Random House, 2007).

10. Philip Howard, “Visualizing Consolidation in the Global Seed Industry: 1996–2008,” Sustainability 1, no. 4 (December 2009): 1271; T. Vijay Kumar et al., Ecologically Sound, Economically Viable: Community Managed Sustainable Agriculture in Andhra Pradesh, India (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2009), 6-7, http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTSOCIALDEVELOPMENT/Resources/244362-1278965574032/CMSA-Final.pdf.

11. Estimated from FAO, “Family Farming Knowledge Platform,” accessed December 16, 2015, http://www.fao.org/family-farming/background/en/.

12. Fumiaki Imamura et al., “Dietary Quality among Men and Women in 187 Countries in 1990 and 2010: A Systemic Assessment,” The Lancet 3, no. 3 (March 2015): 132–142, http://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/langlo/PIIS2214-109X%2814%2970381-X.pdf.

13. Jules Pretty et al., “Resource-Conserving Agriculture Increases Yields in Developing Countries,” Environmental Science & Technology 40, no. 4 (2006): 1115; Catherine Badgley et al., “Organic Agriculture and the Global Food Supply,” Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems 22, no. 2 (June 2007): 86, 88; International Assessment of Agricultural Knowledge, Science and Technology for Development, Agriculture at a Crossroads: International Assessment of Agricultural Knowledge, Science and Technology for Development (Washington, DC: Island Press, 2009).

14. Cheryl Doss et al., “The Role of Women in Agriculture,” ESA Working Paper No. 11-02 (working paper, FAO, Rome, 2011), 4, http://fao.org/docrep/013/am307e/am307e00.pdf.

15. Gerry Marten and Donna Glee Williams, “Getting Clean: Recovering from Pesticide Addiction,” The Ecologist (December 2006/January 2007): 50–53,http://www.ecotippingpoints.org/resources/download-pdf/publication-the-ecologist.pdf.

16. Randy Hayes and Dan Imhoff, Biosphere Smart Agriculture in a True Cost Economy: Policy Recommendations to the World Bank (Healdsburg, CA: Watershed Media, 2015), 9, http://www.fdnearth.org/files/2015/09/FINAL-Biosphere-Smart-Ag-in-True-Cost-Economy-FINAL-1-page-display-1.pdf.

17. Matt Walpole et al., Smallholders, Food Security, and the Environment (Nairobi: UNEP, 2013), 6, 28, http://www.unep.org/pdf/SmallholderReport_WEB.pdf.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 11, 2018 | The Problem: Civilization

Featured image: Police cam video of Daniel Shaver (pictured at right with his daughters) just before being killed by Mesa, Arizona Police Department officer Philip Brailsford. Brailsford was acquitted of second-degree murder in the case.

by Pray for Calamity

Cold air bites at the tip of my nose and the upper rim of my ears as I crunch across the driveway to the wood pile. Pulling from a rick consisting mostly of ash, I load my arms. We burned through the last rick of wood too quickly. Subzero temperatures moved in right after the winter solstice, and for weeks they held strong, the winds at night drawing the heat from our cabin through every crack and seam. Wool blankets cover the windows, and we trade light for heat. At night we nestle into our bed as a family, buried under our down comforter, which can effectively create an ecosystem all its own. Before sunrise though, I will feel my cheeks getting cold, and I will head to the kitchen to find the last embers of the fire on the verge of extinguishing. In the dark I will snap small sticks with my hands, then feed them into the steel belly of the woodstove, and layer split wood on top of that. I wait, watching, listening. When I am sure that the fire has taken, I head back towards bed with the orange flicker lighting the way.

—

The year has rolled over on the calendars of western humans, and the northern hemisphere has had its shortest day in this particular planetary revolution around the sun. It is a time of transitions and resolutions, reflections of the year passed and goals laid out for the year to come. Personally, I feel that we are in a time of exposure. Open secrets once whispered and acknowledge but never loudly spoken are no longer able to be contained. An obvious example of this is the so-called “me too” movement in which powerful men in politics and entertainment who used their status to sexually assault others were publicly exposed, which then blew open the door for women in a variety of industries and lifestyles to report on the bosses and colleagues who used their positions as leverage to seek and sometimes force sexual attention. Basically, a lot of men in a lot of places of power have been using that power to harass and assault women (and yes, sometimes other men) and a lot of dirty laundry has been aired all at once.

Open secrets are not uncommon in our society. Uncomfortable truths that we all come to know, but fear to speak about lest our murmurings disturb the delicate balance of our universe, and tip the whole order into disarray. One of these open secrets that is getting more and more attention is the fact that the police in the United States are arguably a bigger threat to many people than criminals. With nary a legal or civil consequence for their actions to be had, police killed another thousand or so Americans in 2017. The case of former Mesa, Arizona cop Philip Brailsford being acquitted of murdering Daniel Shaver attracted a lot of attention after the body cam video of the event was released, and the general public viewed what was essentially a snuff film with horror, aghast as Brailsford smugly derided the weeping father Shaver who begged for his life before being murdered. Most of the population now accepts that the police and justice systems by and large treat black Americans far differently, and far worse, than they treat white Americans.

Of course, when a nasty truth comes to light, especially a truth that cuts right through the heart of a person’s – or nation’s – identity, there are those who will flat refuse to believe it. In the case of the many exposed men who have been accused of sexual assault and rape, there are cadres of defenders who nit-pick each case looking to find where the accuser is either lying, or perhaps sought or deserved her treatment. It is just so with the issue of police in America. With each new horror show of a news story, even those complete with heartbreaking video as in the case of Daniel Shaver, there are defenders of the system, professional analyzers who find the moment the victim screwed up by not, in their moments of terror, following some command or by having made some innocuous and unconscious movement of the hand. Then they scream, “See! He deserved to die!”

To these reactionaries desperate to believe that everything is OK, women who are abused and harassed by their bosses and colleagues deserve it if they ever take a meeting with a man alone, and untrained and fearful civilians must act with professional precision while teams of academy graduates laden with military firearms and earning a government wage can ignore standards and statutes alike while engaging in murderous street justice.

However, if we believe all these stories of rape and assault, we then have to start examining our culture and try to understand their source. If we believe that the police are racist and unnecessarily violent and murderous, then we have to start examining our culture and try to understand why. Such digging leads to dangerous places for the egos and identities of many. Our lies are pillars that hold up entire institutions and ways of viewing ourselves and the world around us. We have cursed and damned so many people to live out their days in slums or cages, if we haven’t just flat out killed them. If these sentences of impoverishment, imprisonment, and death were all the extension of a society built on lies, then that would make us some pretty terrible people.

Yes, better to not look down that well.

—

I find myself in a bookstore fairly regularly, and I have noticed that over the past few years, there has been significant growth in the survival magazine market. Of course, there are the homestead magazines, the gardening magazines, the hunting magazines, and the straight up gun fetish magazines, but then the other day I noticed something new. It was a magazine that had on its cover a man, a boy, and a woman, all presumably a family. They carried packs, radios, and firearms. A setting sun painted their faces a golden hue, or who knows, maybe it was a distant nuclear blast, as they stood near a ruined vehicle in some scrubland. The father was handsome with chiseled cheek bones, and the lightest Hollywood smattering of dirt across his brow. In true marketing fashion, this was a magazine with a good looking family surviving a civilization-ending EMP blast, bug out bags in tow.

Seeing this I thought to myself that I think it is basically an open secret now that our society is fucked. We are fucked, and no one is coming to save us. Things are going to get steadily worse and worse until the entire façade of civil life breaks into a series of dysfunctional pieces, and deep down, everybody knows it.

A few weeks ago a friend came over to my house, and as she helped me truck firewood from the front of our land to the house, I made a comment about this to test my theory. I cannot now remember how I snuck it into the conversation, but at some point I said, “We’re fucked,” in regards to the future stability of our climate and the world of human comings and goings. She looked at me with a light, knowing smile, and very sincerely said, “Oh yeah.” I might as well have told her that the sun would set.

Of course, my friends are not exactly going to be a random sampling of the population, and they are all going to fall under an umbrella of social consciousness and ecological concern, to be sure, but the increase in television shows, magazines, and books that all orbit the topic of surviving the collapse of society, to me, is telling. For now, we can treat the topic with a bit of irony should we not find ourselves in like company, and laugh at the commercial selling dehydrated beef stroganoff that one can store in their closet for emergencies.

But the idea is out there. Years’ worth of promised solutions to energy and ecological woes have not been delivered. The fires are worse, the floods are more frequent, and still the powers that be are drilling and scraping for every last bit of hydrocarbon. I think most people assumed that somewhere, some group of serious people was laying out the roadmap of transition, and making sure that it would be implemented. The consequences are rolling in as expected, but the global solutions are nowhere to be found. A few companies absorb government subsidies and put out press releases to keep the investors chomping at the bit, but a look around does not show me a world much different than the one in which I walked as a child thirty years ago.

If it becomes understood that this society as it exists has no future, that would mean we have to ask ourselves serious questions about how, or if, we are going to survive. That is a deep, black well indeed.

—

With a night rain came warm air. Gray morning light expands through the wood revealing a half decayed carpet of leaves. Only islands of snow remain, and they are thin and vulnerable. I have eagerly awaited this warm front. The straw in duck and chicken houses needs tossing, and when out in the animal yards I begin to survey first the damage; a plastic rain collection barrel has burst at its base. Then I look to the work; scraping away the ground in front of every gate and door, as the heave of frozen Earth has made opening and closing most of them quite difficult, and no fix was to be had during zero range temperatures.

Animal gates and hen house doors that cannot be closed again once open are not a problem that can be ignored. Raccoons and foxes are particularly hungry this time of year, I can only imagine. A day or two above freezing are opportunities not to be squandered. Winter is only beginning.