by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 11, 2017 | Colonialism & Conquest, NEWS, Repression at Home

The Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta is a unique pyramid-shaped mountain on the northern tip of the Andes in northern Colombia. On its slopes live four separate but related peoples: the Arhuaco (or Ika), Wiwa, Kogi, and Kankuamo. Together they number more than 30,000.

The mountain’s peak is over 5,000m high. Rising from the shores of the Caribbean, the lower plains are clad in tropical forest, turning to open savannah and cloud forest higher up.

To the Indians, the Sierra Nevada is the heart of the world. It is surrounded by an invisible ‘black-line’ that encompasses the sacred sites of their ancestors and demarcates their territory.

by Survival International

Yoryanis Isabel Bernal Varela, 43, was a leader of the Wiwa tribe and a campaigner for both indigenous and women’s rights.

The Wiwa are one of four tribes that live on the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, a unique pyramid-shaped mountain in northern Colombia. The Sierra Nevada Indians believe it is their responsibility to maintain the balance of the universe.

Bernal Varela is the latest victim in a long line of attacks against Sierra Nevada leaders, who have been at the forefront of the indigenous movement in South America. Many Indians have been killed by drug gangs, left-wing guerrillas and the army.

In November 2012 Rogelio Mejía, the leader of one of the other Sierra Nevada tribes, the Arhuaco, narrowly escaped an assassination attempt.

José Gregorio Rodríguez, secretary of the Wiwa Golkuche organization, stated: “Indigenous people are being threatened and intimidated. Today they murdered our comrade and violated our rights. Our other leaders must be protected.”

The problem is not limited to Colombia. Indigenous activists throughout Latin America are being murdered for campaigning against the theft of their lands and resources. The murderers are seldom brought to justice.

In January, Mexican Tarahumara indigenous leader Isidro Ballenero López was killed. In 2005 he had received the prestigious Goldman prize for his fight against illegal deforestation.

Photo by Denise Leisner on Unsplash

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 10, 2017 | Colonialism & Conquest

by Henry Geddes and Martin Valdiviezo /

translated by Angélica Almazán / Intercontinental Cry

Long before it was used by early European settlers to establish the Massachusetts Bay Company–and later, the Massachusetts Bay Colony–the term “Massachusetts” referred to an Algonquian-speaking nation known as the Massachuset. One of dozens of smaller nations that made up the Wampanoag Nation, the Massachuset lived in what is now the eastern side of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, a region that includes the City of Boston. The name “Massachuset” means “At or about the great hill” in the Algonquian language.

The Massachuset’s territory was home to numerous hills and stone structures that lent themselves to burial mounds, ceremonial sites and other religious practices. While many of these sites were undoubtedly lost to the ravages of colonialism, the legacy of the Massachuset invariably remains in the land itself. And so too that of other indigenous nations inhabiting the surrounding area.

Massachusetts–the U.S. state–is home to another legacy. It is the site of the first wave of European colonization that resulted in the decimation of First Nations in North America. While the Massachuset disappeared by 1800, the Mohegan, the Mohican and the greater Wampanoag Nation endured. Efforts such as the modern tradition of “Thanksgiving” have nevertheless obscured the violent nature of the encounter. Even now, Indigenous Peoples continue to struggle for their territorial and cultural rights across the breadth of the U.S. landscape, as the Sioux at Standing Rock can attest in their struggle against the oil pipeline project in North Dakota.

There is another chapter of this struggle currently playing out in the Western Massachusetts town of Shutesbury. Lake Street Development Partners LLC wants to build a 6-megawatt power plant, euphemistically labelled as the Wheelock Tract ‘Solar Farm’ Project to veil an otherwise ecologically disastrous initiative to clear 28.6 acres of healthy forest where the Mohican Peoples claim to have cemeteries and other ceremonial sites.

The Shutesbury Planning Board approved this project in June 2016 even though members of the Narragansett and Wampanoag tribes had previously expressed their concern for an enterprise that would potentially undermine their cultural property rights.

Currently, the project has been stopped by a court order initiated by an individual of Mohawk ancestry to start an investigation that allows Narragansett and Wampanoag representatives with relevant expertise in identifying indigenous cultural property to confirm the existence of archaeological sites on the land in question.

The developers, Lake Street Corporation and the owners of the W.D. Cowls land, have so far refused to give indigenous representatives access to the location to confirm (or not) the presence of indigenous cultural property. The developers intend to enforce an archaeological report conducted by SWCA, an environmental consulting firm from Arizona. According to SWCA’s report, there are no ceremonial sites in the region.

SWCA came to this conclusion without having performed a sub-surface scan to determine if there are human remains.

The research that led to the report sparked controversy because of its lack of cultural and geographic context that might have been provided by qualified indigenous experts on local native cultures, a critique made by external reviewers that included several high profile archaeologists. The debate on the existence of indigenous archaeological remains is crucial to determine the legal foundations and the political instruments that can sustain the cultural property rights of First Nations in Massachusetts and beyond.

Besides the threat to the cultural property rights of the Mohican People, as well as the affront to biodiversity and carbon sequestration involved in clearing almost 30 acres of forest, preliminary research results in Great Britain and the U.S. regarding the actual ecological impact of industrial-scale solar arrays errs on the side of caution until the research is more conclusive.

Numerous oil and hydroelectric projects are ongoing causes for conflicts between energy corporations, Indigenous Peoples and environmental groups, since they involve the destruction or expropriation of ancestral remains and territories. Allegedly, the development of alternative energy projects (such as solar power) could reconcile the interests of these three parties. However, this case shows that solar power projects can have negative social and environmental consequences when designed to privilege capitalist and colonial private interests.

It is important to observe that this debate on the Shutesbury indigenous archaeological heritage is taking place in a context of huge structural inequalities marked by the long-term disregard for indigenous treaties and rights, one that has denigrated indigenous cultures and even denied that they still exist in states like Massachusetts. Such cultural subjugation is still being massively practiced through the statements of public officials and the Media, as well as in books, movies and educational programs that make Indigenous Peoples and their cultural heritage invisible. This is a manifestation of the political marginalization of Indigenous Peoples in Massachusetts that facilitates the appropriation of their legacy. Nevertheless, the recognition of the indigenous cultures in the U.S. and in the world is a fundamental topic of human rights, and it is crucial for the establishment of fair and inclusive democratic societies.

A common thread in the situation of our indigenous brothers in Anglo America and Latin America, from Canada to Chile, is the need to fight against the Eurocentric order to ensure their universal rights to territory, as well as respect for their cultural properties and rights to a dignified and peaceful life. To a greater or lesser extent, despite their democratic and sometimes multicultural or intercultural constitutions, these States continue to reproduce the colonial legacy. The decolonization of the Americas is as crucial for the recognition of our Indigenous Peoples as it is for the fulfillment of the democratic ideals of freedom, equality and solidarity within each one of its States. The stones on the great hills of Massachusetts do matter as sacred spaces and ceremonial sites for all Americans.

Henry Geddes: Associated Professor, Communication Department, University of Massachusetts-Amherst

Martín Valdiviezo: Postdoctoral Researcher. Communication Department, University of Massachusetts-Amherst, Assistant Professor. Education Department. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 9, 2017 | Colonialism & Conquest

by Intercontinental Cry

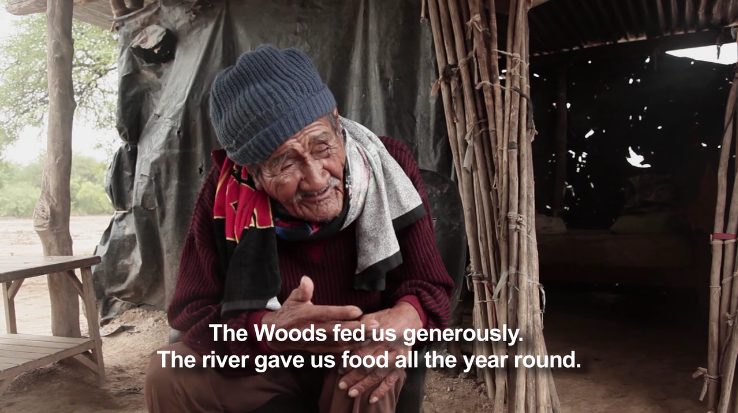

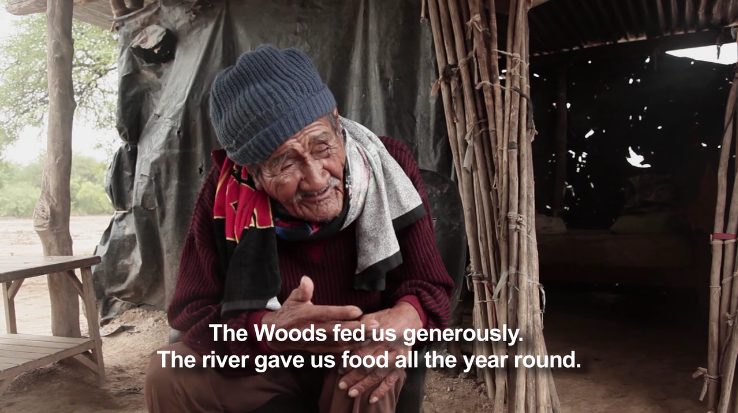

“Na Sam” is a documentary film that sheds light on the modern Chorote way of life.

After being subjugated into a group of insecure land occupiers on their own land, the Chorote have arrived at a desperate pass.

Located in the central-western Chaco region of Argentina, the Chorote are witnessing the desertification of their homeland, widespread soil impoverishment and a loss of biodiversity stemming from indiscriminate felling of native forest and extensive cattle rearing enterprises

Industrial harm to the Pilcomayo River–a crucial source of fresh water and fish–has caused even more damage. The river now presents high levels of mercury contamination and other heavy metals due to spillages in the mining areas of neighboring countries.

Various other development plans, implemented on Chorote lands without consultation, have caused further alteration and degradation to areas of traditional use, leading to increased malnutrition and poverty and reduced access to fresh water.

Beneath this surface of harm, the Chorote are struggling now more than ever to maintain their language and traditions, and their cultural heritage, while adapting to this changing world.

Theirs is culture that is dueling to exist after generations of invisibility and oppression.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 28, 2017 | Colonialism & Conquest, NEWS, Repression at Home

by Courtney Parker / Intercontinental Cry

The climate of violence endemic to the ongoing resource wars, illegal occupation, violent siege, and politically motivated land grabs of Nicaragua’s North Caribbean Autonomous Region, is continuing to escalate.

On Wednesday evening, January 25, the death of a well-known Tuahka Indigenous leader was confirmed – Camilo Frank López was shot in the forehead and killed while leaving a local bar with his cousin. López was the current Tuahka Indigenous Territorial Government Prosecutor.

López’s first cousin, Eloy Frank, who was the Deputy Foreign Minister Secretary for Indigenous Affairs of the Presidency, also suffered an injury to his arm in the attack.

The killing took place in an area known as the ‘Mining Triangle’.

Nicaragua is often lauded for its low crime rates compared to more systemic cultures of violence found in Central American nations such as Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala. However, the region where this latest killing took place, largely known as La Muskitia, has been host to intensifying violent conflict as the legal territories of Indigenous Peoples, such as the Mayagna and the Miskitu, are encroached upon by Mestizo settlers from the interior and Atlantic regions of Nicaragua.

Many claim the illegal settlers are affiliated with the ruling Sandinista political party, who have much to gain economically from seizing and exploiting the resource rich region. Estimates have held that around 85% of Nicaragua’s intact natural resource preserves are contained there; and thanks to ongoing Indigenous stewardship, much of the biodiversity is currently preserved and remains intact.

The binational Indigenous nation of Muskitia, which extends into Honduras, is also home to the second largest tropical rainforest in the western hemisphere – second only the Amazon in size and commonly referred to as “the lungs of Central America”– and many endangered species of animals.

Photo by Mario von Rotz on Unsplash

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 24, 2017 | Colonialism & Conquest, Indigenous Autonomy

Featured image: A Yukpa woman tends laundry high in the clouds of the Yukpa lands, which rise over 3000 meters in the Sierra Perijá on the border of Colombia and Venezuela.

by Nicholas Parkinson / Intercontinental Cry

A community of indigenous Yukpa saw their land reduced to a third of what it once was due to violence and intimidation. Now Colombia’s Land Restitution Unit is helping the community return to their lands.

The spiritual equilibrium essential to the Yukpa community is off balance. Ancestral burial grounds have been desecrated by invaders; the trees that house the spirits are being cut down; and the wild game that Yukpa men once hunted with zeal is no longer available. The same limitations preventing the community from practicing its culture are preventing Yukpa parents from passing these activities, words, and stories down to new generations.

“The loss of culture is very real. Our children won’t know anything about the Yukpa if we aren’t rescued from extinction. If we don’t have space to preserve our culture, I guarantee that in thirty years, our culture will disappear,” says Andrés Vence, council leader of a Yukpa community consisting of 120 families living on 300 hectares in the Sierra Perijá on the border of Venezuela and Colombia.

“Culture’s longevity depends on territory.”

The yukpa believe that land is the key to allowing their culture, customs and beliefs to flourish.

There are an estimated 6,000 Yukpa remaining in Colombia, and the majority live on autonomous lands known as resguardos. Over the past thirty years, the Yukpa community living in La Laguna has been victim to abuse and intimidation stemming from the armed conflict. The community has also seen its ancestral lands become increasingly occupied by “outsiders,” whom they refer to as colonists. Now, the community is pushing back by launching an ethnic restitution claim that seeks to recover 964 hectares of land and allow the community the space it needs to flourish.

HUMILIATION AND ABUSE

In 1982, the guerrilla group known as the FARC came to Yukpa territory to recruit. Andrés Vence was abducted for eight days to be indoctrinated. He and the Yukpa resisted, but then another guerrilla group known as ELN arrived the following year. After the ELN abducted several young men, Vence and his men–armed with just bows and arrows–marched into the guerrilla camp and took their children back, saying the Yukpa would not participate in any war.

A Yukpa security guard, still armed with bow and arrow.

When the Colombian military entered the scene in the mid-1990s, the situation turned for the worst. Yukpa families could no longer move freely from house to house, leading to the systematic abandonment of more than 900 hectares of land. For years, military checkpoints restricted the flow of food between families. As if that wasn’t bad enough, paramilitary groups—who were often the same members of the military—came to the Yukpa villages at night to terrorize the community.

“They abused and humiliated us,” says Vence. “I think it was all in the hopes that we would open our mouths and say something that gave them the right to murder us.”

Andrés Vence, mayor and leader of the Yukpa community making the restitution claim.

DOCUMENTED HISTORY

In 2015, the regional Land Restitution Unit (LRU) in Cesar focused on “characterization studies,” an essential piece of evidentiary material that documents the background, victimization, and suffering of indigenous communities who wish to reclaim their land. Characterization is a critical step in substantiating an ethnic restitution claim. The USAID-funded Land and Rural Development Program* partnered with the LRU to expedite the process.

Over the course of six months, researchers visited the Yukpa, where they interviewed individual members and held focus groups. They also collected materials from the government, non-governmental organizations, academic texts, and the media. The end result was nearly 200 pages of history, mapping, experience, and evidence presenting how the armed conflict contributed to the decimation of the Yukpa’s culture, livelihood, and overall prosperity.

In addition to carrying out the characterization studies, USAID helped regional restitution offices improve coordination with partner members of the Victims Assistance and Comprehensive Reparations System and municipal officials.

“The partnership gave us operating capacity. Without this support, we would have taken another one or two years to get to this case,” says Jorge Chávez, Director of the Land Restitution Unit in Cesar.

The document will be filed as part of the Yukpa community’s land restitution claim, which will go before a restitution judge before the end of the year. By law, judges must issue a ruling within six months after a restitution claim is filed in the court. In Cesar, the Yukpa case will be the third ethnic restitution case to reach the courts, making the department an important player in the nationwide effort to heal the historic rift between the government and Indigenous Peoples.

Colombia’s indigenous communities are often the country’s most vulnerable. Over the past five years, Colombian restitution judges have issued three ethnic restitution sentences, delivering over 124,000 hectares of land back to indigenous communities.

There are currently over 24 ethnic restitution cases in the characterization phase that stand to affect over 10,000 families in Colombia.

“All over the country, there are ethnic restitution cases reaching judges. The LRU is in its fifth year and these cases are becoming more and more important to resolve. This particular case is very important because the Yukpa are losing their cultural identity, and we recognize that,” according to Chávez.

In its five years, restitution judges have issued three ethnic restitution sentences, delivering over 124,000 hectares of land back to indigenous communities.

As the Yukpa wait on the judge’s ruling, the case’s progress has emboldened Vence to mobilize the community—including the older citizens known as Yimayjas—to transmit the collective memory and cultural skills like weaving mochilas, practicing spiritual rites, and crafting shields to fend off malignant spirits.

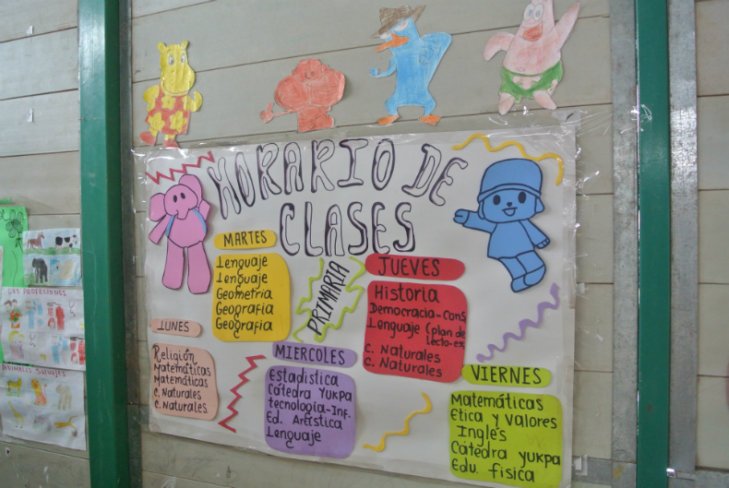

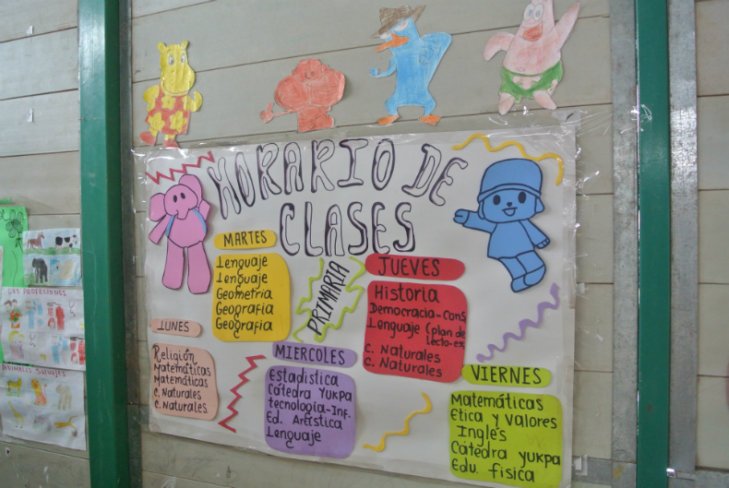

Every Wednesday and Friday, Yukpa children attend “Yukpa studies” at the only school in the resguardo.

A favorable ruling will be key to restoring Yukpa faith in the Colombian government. “We’ve put pressure on the government for many years to do this, so our hope is temporary. We watch television, and indigenous culture is never part of the conversation. Indigenous communities are the most vulnerable,” explains Vence.

* Nicholas Parkinson works for the Land and Rural Development Program.

Nicholas is an NGO writer currently based in Bogota, Colombia and working on a large land tenure program that sets out to strengthen government land administration agencies to better serve millions of victims displaced by the violence. Over the past six years, he has worked mainly on agriculture-focused projects in Ethiopia, Liberia, Uganda and Somalia, among others. He specializes in NGO documentation and teaches local writers how to create attention-grabbing stories for their NGOs. On his weblog you can find stories from his immigrant life, some thoughts on development aid, and a strong dose of rock climbing and adventure.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 23, 2017 | Colonialism & Conquest

Featured image: Without access to their ancestral land, the Baka’s health has deteriorated and they face an uncertain future. © Survival International

by Survival International

An internal report commissioned by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) into the impact of its conservation work in Cameroon on Baka “Pygmies” has been leaked after WWF denied it existed. It reveals:

—WWF knew that the Baka had not been consulted over the national parks which have taken over their land. However, the organization has since maintained publicly that there was “a high level of … community consent.”

—Some ecoguards patrolling the area “behave like masters and lords” towards the Baka, mounting “crackdowns” that are “terrifying.” Despite this, a WWF spokesman described the ecoguards as “performing their designated function of protecting the forests and securing the access and areas of forest communities, including … the Baka.”

—Many perpetrators of abuses are not disciplined when violations are reported by the communities “despite the communities’ condemnation, with proof.” WWF, however, continues to say publicly, “When unacceptable behavior has come to WWF’s attention… WWF has taken the issue up directly and emphatically with [the government], and improved behavior has seemed to follow.”

—“Most of the local villages are affected [by ecoguard abuse]” – but WWF maintained in a written submission to the OECD that “the possibility of ecoguard abuse does not currently seem to be a high priority for most Baka communities.”

This Baka man was beaten by guards. Survival has spoken to dozens of similar victims across the Congo Basin.

© Survival International

Contrary to its own guidelines, WWF has never released the report, despite requests from Survival International and Baka activists. In an interview with the environmental magazine Mongabay, WWF’s “Head of Issues Management” Phil Dickie denied that WWF had commissioned any investigation into Survival’s allegations.

Survival International lodged a formal complaint in February 2016 with the Swiss National Contact Point of the OECD over WWF’s activities in Cameroon. The complaint was admitted in December 2016, the first time a non-profit organization has been scrutinized in this way.

One Baka man said: “The forest used to be for the Baka but not anymore. We would walk in the forest according to the seasons but now we’re afraid. How can they forbid us from going into the forest? We don’t know how to live otherwise. They beat us, kill us and force us to flee.”

Survival’s Director Stephen Corry said: “WWF commissions a report to look into its effect on the Baka, presumably including claims of abuse committed by the ecoguards it funds. The report confirms the abuse is widespread and routine. WWF then denies the report exists. It’s time for this big conservation organization to square up to the responsibilities it has to those who have seen their land stolen for conservation. And it’s time the world woke up to the horror that’s going on in the name of conservation. It’s not just Cameroon and not just WWF: the conservation industry has a history of taking tribal people’s land. It’s green colonialism and we’re doing all we can to fight it. Many conservationists know that tribal peoples are the best guardians of the natural world which is why the big conservation organizations should start listening to them rather than conspiring in their destruction.”

See here for a comparison of what WWF’s internal report says about Baka abuse with what WWF have said publicly, and what the Baka say. The full report is available on request.

“Pygmy” is an umbrella term commonly used to refer to the hunter-gatherer peoples of the Congo Basin and elsewhere in Central Africa. The word is considered pejorative and avoided by some tribespeople, but used by others as a convenient and easily recognized way of describing themselves.