by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 15, 2016 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Lobbying

Featured image: A bull buffalo lies dead, just outside Yellowstone’s north boundary. Photo by Stephany Seay, Buffalo Field Campaign

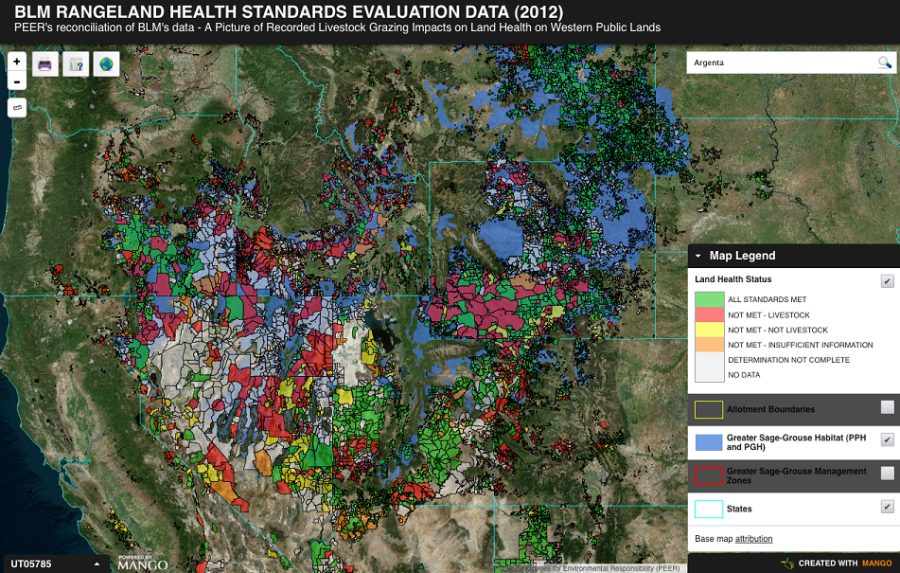

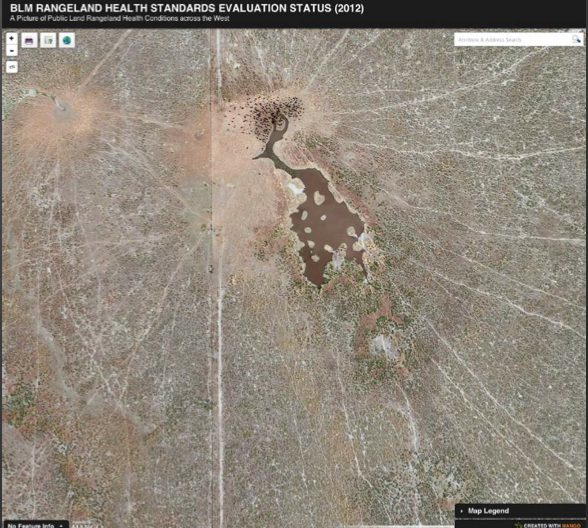

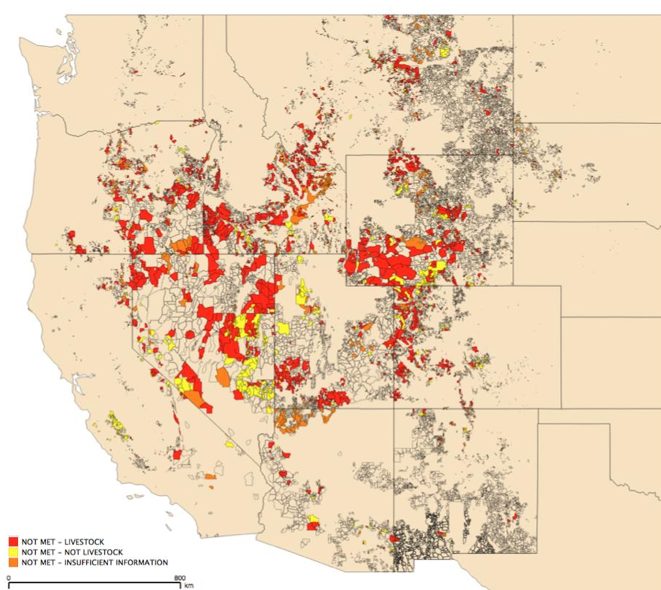

On January 12, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) denied Endangered Species Act protection for the iconic Yellowstone Bison. The agency’s decision comes 14 months after Western Watersheds Project and Buffalo Field Campaign petitioned to list these bison as an endangered or threatened species. The groups sought federal protection for the Yellowstone bison because these unique bison herds are harmed by inadequate federal and state management and other threats. In the finding, the USFWS now agrees that the Yellowstone bison are a distinct population of bison, reversing its 2011 position.

“If buffalo are to recover as a wild species in their native ecosystem, science must prevail over politics,” said BFC Executive Director Dan Brister. “The best available science indicates a listing under the Endangered Species Act is necessary to ensure the survival of this iconic species.”

“Friends of Animals is committed to protecting the last wild bison in America. We are disappointed in USFWS’s finding and suspect that the decision was improperly influenced by the interests of private ranchers in the area. We are reviewing the agency’s decision and plan to take further legal action if necessary,” stated attorney Michael Harris of Friends of Animals Wildlife Law Program.

“We petitioned the USFWS to list the Yellowstone bison because of clear management inadequacies and growing threats to this key population of wild bison. The USFWS decision is disappointing because protection under the Endangered Species Act is the only way to counter the management inadequacies and growing threats,” stated Michael Connor of Western Watersheds Project.

The groups’ petition catalogues the many threats that Yellowstone bison face. Specific threats include: extirpation from their range to facilitate livestock grazing, livestock diseases and disease management practices by the government, overutilization, trapping for slaughter, hunting, ecological and genomic extinction due to inadequate management, and climate change.

Federal and state policies and management practices threaten rather than protect the Yellowstone bison and their habitat. Since 2000, more than 4,000 bison have been captured from their native habitat in Yellowstone National Park and slaughtered. The Forest Service issues livestock grazing permits in bison habitat. The states of Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming forcefully remove or kill bison migrating beyond the National Park borders.

Once numbering tens of millions, there were fewer than 25 wild bison remaining in the remote interior of Pelican Valley in Yellowstone National Park at the turn of the 20th Century. The 1894 Lacey Act, the first federal law specifically safeguarding bison, prevented the extinction of these few survivors.

The agency’s justification can be found online at:

http://buffalofieldcampaign.org/ESA_90_Day_Finding.pdf

The petition to list Yellowstone bison is available online at http://www.buffalofieldcampaign.org/ESAPetition20141113.pdf

Visit Buffalo Field Campaign for field updates

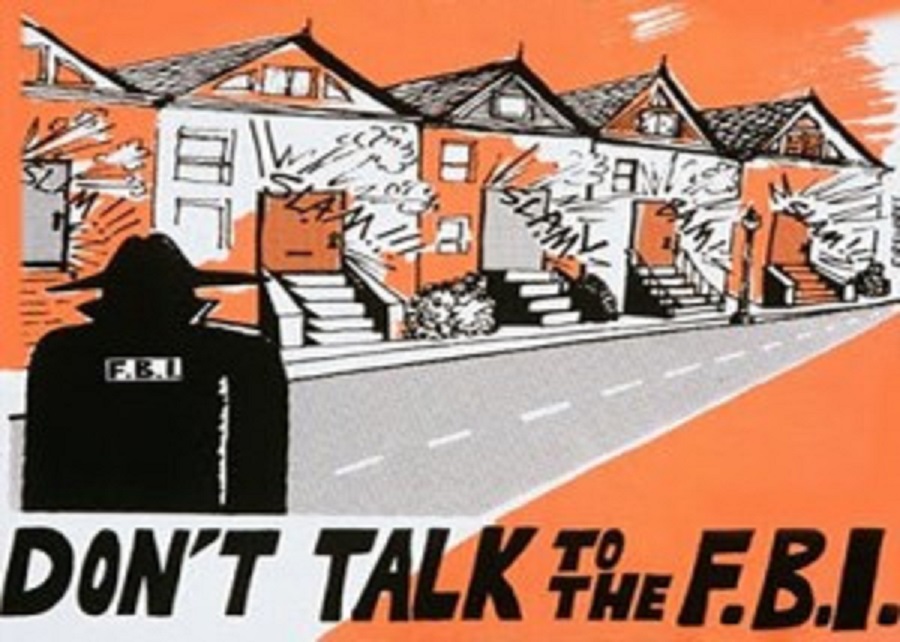

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 14, 2016 | Repression at Home

By Mark Hand / CounterPunch

Federal Bureau of Investigation and Department of Homeland Security agents have contacted more than a dozen members of Deep Green Resistance (DGR), a radical environmental group, including one of its leaders, Lierre Keith, who said she has been the subject of two visits from the FBI at her home.

The FBI’s most recent contact with a DGR member occurred Jan. 8 when two FBI agents visited Rachael “Renzy” Neffshade at her home in Pittsburgh, PA. The FBI agents began the visit by asking her questions about a letter she had sent several months earlier to Marius Mason, an environmental activist who was sentenced in 2009 to almost 22 years in prison for arson and property damage.

Neffshade told CounterPunch she refused to answer any questions from the FBI agents. Based on the line of inquiry, Neffshade concluded the FBI agents were not necessarily looking into gathering further information about Mason. “It seemed like they were pursuing an investigation into me, but who knows? I didn’t answer any of their questions,” she said. “It’s important to remain silent to law enforcement as an activist. It is a vital part of security culture.”

DGR, formed about four years ago, requires its members to adhere to what the group calls a “security culture” in order to reduce the amount of paranoia and fear that often comes with radical activism. On its website, DGR explains why it is important not to talk to police agents: “It doesn’t matter whether you are guilty or innocent. It doesn’t matter how smart you are. Never talk to police officers, FBI agents, Homeland Security, etc. It doesn’t matter if you believe you are telling police officers what they already know. It doesn’t matter if you just chit chat with police officers. Any talking to police officers, FBI agents, etc. will almost certainly harm you or others.”

Keith, along with Derrick Jensen and Aric McBay, co-authored a book published in 2011, Deep Green Resistance, on which the DGR group is largely based. DGR describes itself as an “aboveground organization that uses direct action in the fight to save our planet.” On its website, DGR states there is a need for a separate “underground that can target the strategic infrastructure of industrialization.”

In the “Deep Green Resistance” book, the authors ask, “What if there was a serious aboveground resistance movement combined with a small group of underground networks working in tandem?”

“[T]he undergrounders would engage in limited attacks on infrastructure (often in tandem with aboveground struggles), especially energy infrastructure, to try to reduce fossil fuel consumption and overall industrial activity,” the authors write in the book. “The overall thrust of this plan would be to use selective attacks to accelerate collapse in a deliberate way, like shoving a rickety building.”

In speeches and writings, Jensen, a co-leader of DGR, often ponders this question: “Every morning when I wake up I ask myself whether I should write or blow up a dam.” He also has argued about the necessity of using any means necessary “to stop this culture from killing the planet.” Jensen said he has not been questioned by the FBI about his involvement with DGR. He is also unaware of any DGR members who have been arrested for their work with the group.

In late 2014 and early 2015, the FBI contacted about a dozen DGR members either by telephone or through in-person visits. Max Wilbert, a professional photographer and one of the founding members of DGR, said the FBI contacted him on his cell phone during this period. “I immediately said that I wasn’t going to answer any questions and hung up the phone,” Wilbert told CounterPunch. “This is the best way to deal with this sort of government repression. As soon as they know that you will answer questions, they will keep coming after you.” If activists refuse to answer questions, the FBI or other police agencies are more likely to leave the person alone, he said.

In September 2015, Wilbert was among a group of DGR members detained at the U.S.-Canada border as they were on their way to attend a speech by author Chris Hedges in Vancouver, British Columbia. The group was eventually denied entry into Canada.

Wilbert said the Canadian border guards seemed to be searching for a reason to deny the DGR members entry. After focusing on some women’s self-defense gear in the car (some people in the vehicle were planning to offer a free class on self-defense in British Columbia), the border guards’ questions started turning to each person’s activism.

Making sure he was honest with the officers, Wilbert told the Canadian border guards that he had volunteered to take photographs of Hedges’ scheduled speech. “They said that they suspected I was entering the country to work illegally,” he said.

After getting turned back by the Canadian guards, the vehicle’s occupants faced additional scrutiny by U.S. border agents. At the U.S. border, the questions became much more political in nature. The U.S. guards asked Wilbert and his colleagues about the groups they belonged to and the ideas that these groups promoted. “Officers from the Canadian side even came over and spoke with the U.S. officers about us,” he said.

U.S. border guards confiscated Wilbert’s laptop computer. “Under U.S. law, they can legally copy your entire hard drive and keep the contents for something like 30 days,” he said. After a few hours, the border guards returned the computer. But Wilbert chose to get rid of the laptop after the search because he was concerned the government agents had tampered with it.

The Department of Homeland Security also has demonstrated an interest in the environmental group. DGR member Deanna Meyer, who lives in Colorado, was asked by a DHS agent during a visit to her home if she would be interested in “forming a liaison,” according to a July 6, 2015, article in Earth Island Journal. The agent reportedly told Meyer he wanted to “head off any injuries or killing of people that could happen by people you know.” Meyer refused to cooperate with the DHS agent.

Wilbert views the federal police agencies’ ongoing actions against DGR members as harassment and intimidation. “It makes a mockery of free speech and democracy. We may advocate for radical and revolutionary ideas, but our work is legal. We are nonviolent. We are peaceful people,” he said.

The federal government’s treatment of DGR members is similar in some ways to how political activists were treated during the Red Scare era of the 1950s, contended Wilbert. A relative of blacklisted Hollywood screenwriter Dalton Trumbo is a member of DGR and a friend of Wilbert’s. Her childhood was marked by government surveillance, blacklisting and intimidation, he said. Pointing to Dalton Trumbo and other victims of the McCarthyite period, Wilbert emphasized these tactics are not new.

“This government uses intimidation and violence because these tactics are brutally effective. For me and the people I work with, we expect pushback,” Wilbert said. “That doesn’t make it easy, but in a way, this sort of attention validates the fact that our strategy represents a real threat to the system of power in this country. They’re scared of us because we have a plan to hit them where it hurts.”

The police scrutiny of DGR members is continuing at the same time local and federal police agencies maintain a hands-off approach to the takeover of a federal government installation in eastern Oregon by an armed right-wing militia. Some of the militia members claim they would be willing to kill if police attempted to end their occupation of the federal wildlife refuge.

If environmental activists staged an armed occupation of a coal-fired power plant, coal export terminal, or hydroelectric facility in the Western United States, they would be subject to an intense and immediate response by police agencies, Wilbert said. “The federal government doesn’t really give a damn, by and large, about what happens in the open West, at least when it’s wealthy white people doing the occupying,” he said. “But any occupation that actually threatened their power would see swift retribution. That is one of the main jobs of the police: to protect the rich and business interests against the people.”

DGR has learned that the “Deep Green Resistance” book is part of the FBI’s library at the agency’s offices in Quantico, Va. “They’re definitely aware of us. We have filed a Freedom of Information Act request to find out what kind of information the FBI is gathering,” Wilbert said. “But those requests were denied because they involve active investigations.”

When FBI agents visited her home in Pittsburgh, Neffshade said she felt fear during the questioning. She tried to remain calm. “I felt pressure to respond to their questions because, hey, I’ve been taught that it’s rude to just stand in silence when someone is speaking to you,” she explained. “I maintained silence long enough to gather my thoughts about which phrases are appropriate to say to law enforcement. After they left, I felt shaky and had to fight off feelings of paranoia.”

Before they left, the FBI agents handed Neffshade a business card and said, “If you change your mind, here is contact information.” Neffshades immediately contacted members of DGR to let them know the FBI had showed up on her doorstep.

While the FBI visit will make her more careful about what she writes in letters to prisoners, Neffshade said she has no plans to retreat from her involvement with DGR.

Mark Hand has reported on the energy industry for more than 25 years. He can be found on Twitter @MarkFHand.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 13, 2016 | Alienation & Mental Health

By Will Falk / Deep Green Resistance Great Basin

Featured image: Utah snow by Max Wilbert

Sitting on the patio at the Park City Library on a crisp September afternoon, I admire the beauty of this season’s new dusting of snow on mountains awash in the golds, reds, and greens of fall. I arrived in Park City last week thinking I will live in Utah again for the first time in almost 10 years.

The mountains’ timelessness makes it hard to believe it’s been 10 years since I packed my parents’ 1992 black Chevy suburban on a cold December night in Cedar City in 2005 before making the long drive to Iowa to be closer to my family in the Midwest. The joy that the sight of new snow has always produced for me makes it hard to believe its been 10 years since I last watched the good, thick Utah snow gather behind me to cloud the scene from my rear-view mirror as I pulled away softening the reminders of what and who I left behind.

Almost immediately after recognizing this beauty, I feel a deep pang of anxiety. I have been reading about the impacts climate change will have on Utah’s snow. I know, for example, that many scientists agree with Porter Fox, the author of DEEP: The Story of Skiing and the Future of Snow, that there will be no snow in Utah by the end of this century if climate change cannot be stopped.

My memories make it incredibly painful to imagine a Utah without snow, but this is the reality confronting us. Loving the snow as I do and understanding what the snow means to both humans and non-humans in Utah, I cannot help but call human-produced climate change “suicidal.”

***

I am intimately familiar with suicide. Sometime in the ten years after leaving Utah, I developed what my doctors have called “major depressive disorder.” When I was a public defender in Kenosha, WI, I tried to kill myself in April, 2013 and, again, in August, 2013.

I have spent the last two years trying to understand the darknesses that led me to attempt to take my own life those two times. I’ve always possessed a certain type of melancholy, but it takes more than a simple disposition for melancholy to develop suicidal depression.

Many theories exist for why I took the road to attempted suicides.

First, I have a history of traumatic head injuries including a brain contusion I suffered in a high school football game. I cannot remember what happened, but I do remember watching the game film the next morning and seeing my head bounce like a ball on the turf after I was knocked completely off my feet. I do not know if I suffered full-blown concussions playing college football at the University of Dayton, but I do remember my head hurting an awful lot. This theory supports the view that depression is truly a mental illness. My doctors tell me my brain struggles to recycle serotonin, and that this could be a result of the head injuries.

Another theory roots the depression I experience in my history of disconnection from any one place. I’ve never lived anywhere for long and this perpetual moving creates a feeling of spiritual vertigo for me. I was born in Evansville, IN, moved to Bedford, IN, moved to Salt Lake City, went to Cedar City, UT, re-joined my family in Waterloo, IA, headed to Dayton for college, then Madison, WI for law school, and on to Milwaukee to work in the public defender’s office. I lived in all of these places before I was 26. Each uprooting came with its own specific pains. Eventually, however, like a plant who will not take to new soil, I rejected the idea I could ever grow roots anywhere.

The final theory for my suicide attempts – and the one that makes the most sense to me – points to an overwhelming mixture of exhaustion, guilt, and despair I built as a public defender watching client after client dragged away to prison while I woke every morning to read news reports of ever more environmental destruction. I worked 60 and 70 hour weeks and it never seemed to matter. I could not keep my clients out of prison. I brought my case files home and some nights woke up at 3 AM to get a head start on the day. The more I lost, the stronger my feelings of guilt grew. It was my fault. I needed to work harder. The harder I worked, the more exhausted I became. The more exhausted I became, the harder it was to fight the guilt. The more guilt I felt, the harder I told myself I needed to work.

On top of this, I recognized – and still do – the fact that the planet’s life support systems are under attack by forces like climate change causing a growing number of scientists to predict human extinction by as soon as 2050. Carcinogens have seeped so deeply into the earth that every mother in the world has contaminants like dioxin in her breast milk; humans have successfully poisoned the most sacred physical bond between mother and child.

Meanwhile, nearly 50 percent of all other species are disappearing. Between 100-200 species a day are going extinct around the world. One quarter of the world’s coral reefs have been murdered. In the United States, alone, 95% of old growth forests are gone. In 70 countries worldwide there are no longer any original forests at all.

I often try to apologize for listing off these facts, or explain that perhaps I fixate on these things because I have a mental illness. I will not do that any longer. These atrocities are happening. Unless you are a sociopath, to truly contemplate these facts, to understand what they mean, to feel their implications comes with a profound emotional cost. I might have a mental illness, but it is natural to feel despair when confronted with the possibility of the destruction of all life on the planet.

***

I return to Utah after spending two years on the road supporting indigenous-led land-based environmental struggles. Why, just months after trying to commit suicide, did I set out for the front lines of the environmental movement?

Well, my experiences tell me that emotional states like despair, by themselves, are illusions and cannot hurt me on their own. Afflicted as I often am with a poor self-esteem and feelings of inadequacy, I learned that even when those thoughts arise, I do not have to entertain them. I can let them flash across the movie screen in my mind without ever attaching any meaning to them.

Despair by itself cannot kill me. I can kill me. Feeling the despair, I can grind several pills into powder, snort the powder to numb the pain, and then drink down the rest of the pills. Similarly, feeling the despair, I could put a gun to my temple or jump from a bridge. But, in each of these cases, it will not be the despair that kills me. It will be a physical action that kills me.

I find this realization to be deeply empowering. While I cannot always control my emotional state, I can control my actions. No matter how much despair I feel, I can refuse to act on that despair. Following this idea, I started to understand that I was not going to heal my mental illness with thoughts alone. I was not going to think my way out of depression. In order to heal, I needed to take tangible steps to alleviate the despair I was feeling.

First, I went up to central British Columbia to volunteer at the Unist’ot’en Camp. The Unist’ot’en Camp is an indigenous cultural center and pipeline blockade on the traditional, unceded territory of the Unist’ot’en clan of the Wet’suwet’en First Nation. I helped to build a bunkhouse on the precise GPS coordinates of a pipeline that would carry fossil fuels from the Fort McMurray tar-sands in Alberta over Unist’ot’en territory to a refinery in Kitimat, BC where the fossil fuels would be processed and shipped to be burned in markets world wide. I helped to break trails and walked the trapline on Unist’ot’en territory in the winter. Most of my time was spent sleeping on floors and couches in Victoria, BC as I volunteered for fundraising and organizing efforts to support the Camp.

I ran out of money in Canada and found it difficult to find work as a non-citizen, so I returned to my parents’ home in San Ramon, CA. Before long, though, I was encouraged to head to Hawai’i to write about Kanaka Maolis’ (native Hawaiians’) efforts to prevent the Thirty Meter Telescope from being constructed on the summit of their most sacred mountain, Mauna Kea. I spent 37 nights at 9,200 feet sleeping on the cold ground. I saw more snow than beaches in Hawai’i and was present when the police tried to force a way through 800 Kanaka Maoli as they blocked the construction equipment from gaining Mauna Kea’s summit. The police arrested 12 people that day, but were forced to turn back when boulders were rolled into the one road leading to the construction site.

Sometimes people try to thank me for my environmental activism. I always want to tell them not to thank me. I had to do it. All the thanks should go to the Unist’ot’en Clan and Kanaka Maoli for their bravery in protecting the Earth.

There’s a darker side to my decision to give up on a mainstream lifestyle to more effectively support environmental causes. I quit my job, gave up my apartment lease, sold my car, and broke up with the woman I was dating (a woman who stayed with me through the suicide attempts) in order to take off for Canada. It was not long before my money ran out and I was relying entirely on the generosity of others to help me along the way.

There are times when I wonder if it really is all that brave to turn my back on the normal responsibilities adults in this culture must attend to for basic survival. Getting a real job terrifies me. Maybe all I was doing on the road was avoiding putting my life back together after the suicide attempts?

***

While I ponder the snow from the Park City Library, I am reminded that I should be working on several of the online content writing gigs I have taken in an effort to re-build a sustainable income for myself. While I was on the road, I got sick of being broke. I became profoundly lonely for familiar places. I began to crave consistency in my day-to-day life.

I have a friend here in Park City, for example – the truest kind of friend who earned my trust after years of selfless communication and sincere concern for my well-being – who reminded me while I was on the road that I was always welcome in Utah. Her words were deeply encouraging, but I also knew I might not have enough money to get to Utah to see her. The truth is, to maintain relationships, you have to – at least sometimes – see those with whom you seek relationship.

The content writing gigs are a reminder of the long path facing me back to financial self-sufficiency. I would be lying if I did not confess the despair I sometimes feel when I realize just how out of control I let my personal life get. My student loans did not pay themselves. My resume can not magically produce an explanation for the hole in my work history. I still do not have enough money in my bank account to pay a first month rent and deposit to secure my own place to live.

Looking at my situation, the darkness begins to creep back in. I feel a deep sense of guilt wondering if I’ve sold out the environmental movement in order to build a community for myself. What right do I have to slow down right now? How can I look the Unist’ot’en Clan or Kanaka Maoli in the eye while their homes are under attack and I’m writing content for personal injury lawyers? Seeing the beauty of the snow on Park City’s peaks, knowing Utah may soon be too hot for snow to exist, why am I not running back to the front lines?

When these thoughts begin to spiral, I know I am in danger. I begin to hear that old whispering, suggesting a way out. I remember that there is a route to numb this confusion. It would not take too much of an effort to make it all fade away.

There the snow is again, though, and I know I will never try to kill myself again. I see the dark, heavy clouds weighing on the mountains’ shoulders. The chill in the air is a comfort because it brings the promise of water. As the powder spreads down the mountainsides, I know for another season, at least, there will be snowmelt, the streams will swell, and life will flourish across the land.

The snow in Park City brings a lesson. The snow is the future. Where there is snow, there is water and where there is water, there is life. Despair is the inability to see a livable future. Those who are destroying the planet are also destroying our future. When they clear-cut a forest, they clear-cut the future for those living in the forest. When they dam a river, they dam that river’s future. When they burn their fossil fuels and boil the Earth’s temperatures so that the snow in Park City disappears, they’re burning and boiling Park City’s future.

The snow, then, gives me my medicine for despair. The snow is the future. Fight for the snow, fight to ensure that the snow will continue to fall, and seeing the snow fall will bring the ability to see a livable future.

Colorado Plateau, southern Utah

Thoughts of suicide still sometimes fleet across my mind. Suicide’s mystique fades after you’ve gone through the spiritual process and the physical actions to produce your own death. The scariest part about it is that it really isn’t that scary at all. Suicide can come so easily.

But, the snow falls, and I know I cannot help the snow if I am dead. I am still engaged in war with my own demons and have had to re-consider my capacity, but if I can defeat those demons maybe I can become a stronger activist than I ever thought possible. The snow is too beautiful, the joy I feel seeing the snow is too strong, and the first stirrings of a feeling of belonging in Park City are too compelling for me to ever give in like that again.

Will Falk is a former public defender turned environmental writer and activist. He has been engaged in support for aboriginal sovereignty on the front lines at the Unist’ot’en Camp in so-called British Columbia and on Mauna Kea in Hawai’i. He is in the process of moving to Park City, Utah.