by DGR Colorado Plateau | Mar 8, 2015 | Property & Material Destruction, Repression at Home, Strategy & Analysis

In 1993 Michael Carter was arrested and indicted for underground environmental activism. Since then he’s worked aboveground, fighting timber sales and oil and gas leasing, protecting endangered species, and more. Today, he’s a member of Deep Green Resistance Colorado Plateau, and author of the memoir Kingfishers’ Song: Memories Against Civilization.

Time is Short spoke with him about his actions, underground resistance, and the prospects and problems facing the environmental movement. Due to the length of the interview, we’ve presented it in three installments; go to Part II here, and Part III here.

Time is Short: Can you give a brief description of what it was you did?

Michael Carter: The significant actions were tree spiking—where nails are driven into trees and the timber company warned against cutting them—and sabotaging of road building machinery. We cut down plenty of billboards too, and this got most of the media attention. We did this for about two years in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, about twenty actions. My brother Sean was also indicted. The FBI tried to round up a larger conspiracy, but that didn’t stick.

TS: How did you approach those actions? What was the context?

MC: We didn’t know a lot about environmental issues or political resistance, so we didn’t have much understanding of context. We had an instinctive dislike of clear cuts, and we had the book The Monkey Wrench Gang. Other people were monkeywrenching, that is, sabotaging industry to protect wilderness, so we had some vague ideas about tactics but no manual, no concrete theory. We knew what Earth First! was, although we weren’t members. It was a conspiracy only in the remotest sense. We had little strategy and the actions were impetuous. If we’d been robbing banks instead, we’d have been shot in the act.

Nor did we really understand how bad the problem was. We thought that deforestation was damaging to the land, but we didn’t get the depth of its implications and we didn’t link it to other atrocities. We just thought that we were on the extreme edge of the marginal issue of forestry. This was before many were talking about global warming or ocean acidification or mass extinction. It all seemed much less severe than now, and of course it was. The losses since then, of species and habitat and pollution, are terrible. No monkeywrenching I know of did anything significant to stop that. It was scattered, aimed at minor targets, and had no aboveground political movement behind it.

Clearcuts in the Swan Valley, MT near Loon Lake on the slope of Mission Mountains. Photo by George Wuerthner.

TS: What was the public response to your actions?

MC: They saw them as vandalism, mindlessly criminal, even if they were politically motivated. This was before 9/11, before the Oklahoma City bombing; the idea of terrorism wasn’t so powerful, so our actions weren’t taken nearly as seriously as they would be now.

We were charged by the state of Montana with criminal mischief and criminal endangerment. The state’s evidence was solid enough we thought we couldn’t win a trial, so we pled guilty on the chance the judge wouldn’t send us to prison. Our defense was to say, “We’re sorry we did it, it was motivated by sincerity but it was dumb.” And that was true. We were able to get our charges reduced from criminal endangerment to criminal mischief. I got a 19 year suspended prison sentence, Sean got 9 years suspended. We both had to pay a lot of money, some $40,000, but I only spent three months in county jail and Sean got out of a jail sentence altogether. We were lucky.

TS: As you said, this was before the obsessive fear of terrorism. How do you think that played into your trial and indictment, and how do you think it would be different today?

MC: Had it happened after any big terrorism event, they would have sent us to prison, there’s no doubt about that. States have to maintain a level of constant fear and prove themselves able to protect citizens.

The irony was, I’m not sure I wanted to be serious—there seemed to be something protective in not being all that effective, in being intentionally quixotic, in being a little cute about it. There was a particularly comical aspect to cutting down billboards, and that was helpful only when I was arrested. It made it look less like terrorism and more like reckless things I did when I was drunk, and a lot of people approved of it because they thought billboards were tacky. I want to emphasize that cutting down billboards is nothing I’d advise anyone to consider, only that a little bit of public approval made a surprising difference to my morale, and may have positively influenced sentencing. But the point, of course, is to be effective and not get caught in the first place. These days, if someone gets caught in underground actions, they will be in a lot more trouble than ever before.

TS: How did you get caught?

We left fingerprints and tire tracks, we rented equipment under our own names—like an acetylene torch used to cut down steel billboard posts—and we told people who didn’t need to know about it. We assumed we were safe if they didn’t catch us in the act and because our fingerprints weren’t on file, and we couldn’t have been more wrong. The cops can subpoena anyone’s fingerprints, and use that evidence for something in the past. The importance of security can’t be overstated—and we didn’t have any. Even with a couple rudimentary precautions, we might have saved ourselves the whole ordeal of getting caught. If we’d read the security chapter of Dave Foreman’s book Ecodefense, I don’t think we would have even come under suspicion. Anyone taking any action, above- or underground, needs to take the time to learn security well.

It’s not just saving yourself the anguish of arrest and prison time. If you’re rigorous about security, you might be able to have a real chance at changing how the future of the planet plays out. You can have no impact at all in a jail cell. In our case, we definitely could have stopped timber sales with tree spiking even though that tactic was extremely unpopular politically. It was seen as an act of violence against innocent lumber mill workers instead of a preventative measure to protect forests. The dilemma never got past that stage, though. We had little chance of having any reasoned tactical considerations—let alone making reasoned decisions—because we were always a little too afraid of being caught. With good reason, it turns out.

TS: What have you learned from your experience? Looking back on what you did all those years ago, what’s your perspective on your actions now? Is there anything you would have done differently?

MC: Well I definitely would have taken steps to not get caught. I would have picked my targets more carefully, and I would have entered into an understanding with myself that while my enemy is composed of people, it’s only a system, inhuman and relentless. It can’t be reasoned with; it has no sanity, no sense of morality, no love of anything. Its job is to consume. I would have tried to focus on that guiding fact, and not on the people running it or who were dependent on it. I would have tried to find the weaknesses in the system, and then attacked those.

I’d have tried not to allow my emotions to dictate my strategy or actions. Emotions might get me there in the first place—I don’t think you could get to such a desperate point without a strong emotional response—but once I arrived at the decision to act, I would have done everything I could to think like a soldier, find a competent group to join with, and pick expensive and hard-to-replace targets.

TS: I assume you didn’t just wake up one day and decide to attack bulldozers and billboards. What was your path from being apolitical to having the determination and the passion to do what you did?

MC: When I was struggling with high school, my brother loaned me a stack of Edward Abbey books, which presented the idea that wilderness is the real world, precious above all else. The other part was living in northwest Montana, where you see deforestation anywhere you look. You can’t not notice it, and there’s something about those scalped hills and skid trails and roads that triggers a visceral, angry response. It’s less abstract than atmospheric carbon or drift-net fishing. You don’t see those things the way you see denuded mountainsides. My family heated the house with wood, and we would sometimes get it out of slash piles in the middle of clearcuts. I had lots of firsthand exposure to deforested land. I wondered why the Sierra Club didn’t do something about it, how it could be allowed. We would occasionally go to Canada, and it was even worse up there. No one can feel despair like a teenager, and I had it in spades. If Greenpeace won’t stop this, I reasoned, well then I will.

I started building an identity around this, though, and that’s disastrous for a person choosing underground resistance. You naturally want others to know and appreciate your feelings and accomplishments, especially when you’re young, but the dilemma underground fighters face is that they must present another, blander identity to the world. That’s hard to do.

TS: You were fairly isolated in your actions, and you’ve emphasized the importance of a larger context. Do you see those two ideas connecting? Do you think saboteurs should be acting in a larger movement?

MC: I think saving the planet relies completely on the coordinated actions of underground cells coupled with an aboveground political movement that isn’t directly involved in underground actions. When I was underground, I had no hope of building a network, mostly because of a lack of emotional and political maturity. I also didn’t have the technological or strategic savvy, or a means of communicating with others. The actions themselves were mostly symbolic, and symbolic actions are a huge waste of risk. They’re a waste of political capital too. Most everyone is going to disagree with underground activism and it’s not going to change anyone’s mind about the policy issue—hardly anything will—so it has to count in the material realm. If people are ready and willing to risk their lives and their freedom then they should fight to win, not just to make some sort of abstract point.

TS: After you were arrested, what support—if any—did you receive from folks on the outside, and what support would you have wanted to receive?

MC: The most important support was financial, but there wasn’t a lot of it. Our plea bargain didn’t guarantee we wouldn’t go to prison. We were also worried that the feds would indict us for racketeering, an anti-Mafia charge with serious minimum sentencing. If we’d had more legal defense financing we’d of course have felt a lot more secure, but twenty years of reflection tells me we didn’t really deserve it considering how poorly we executed the actions, what little effect they caused.

That sounds like I’m being awfully hard on myself, and hindsight is always 20/20, but the point is that a legal crisis is exhausting and expensive. Your community will question whether your actions are worthy of the price they’ll have to pay if you’re caught. My actions were not.

Even so, I appreciated any sort of support. Hearing from the outside in jail is better than you’d believe. A lot of Earth First! Journal readers sent me anonymous letters. I wrote back and forth with one of the women who was jailed for noncooperation with a federal grand jury investigating the Animal Liberation Front in Washington. Seeing approving letters to the editor in the papers was also great. Just knowing that the whole world isn’t your enemy, that someone is thinking about you and appreciates what you did, is priceless.

Artwork by Stephanie McMillan

TS: Do you still think militant and illegal forms of direct action and sabotage are justified? Why?

MC: I do, yes. In an ideal world I don’t think violence is the best way to accomplish anything, but obviously this isn’t an ideal world. Our circumstances are getting worse and worse—overpopulation, pollution, oceanic dead zones, you name it—and any options for a decent and dignified future for humanity are dwindling day by day, so what choice does that leave us? Individual attempts at sustainable living won’t work so long as the industrial system is running. The dismantling of infrastructure is the most important missing piece right now. It’s where the system is most vulnerable, so it should be employed right away. It can be effective, but it has to be responsible, careful, and extraordinarily smart.

One of the reasons underground political actions are so unpopular is that they’re always presented as attacks on individuals, rather than on a system. I think it’s important to reframe sabotage as strikes on an unjust, destructive system, and that civilization is not us, and not the highest expression of human endeavor, but only an idea. Civilization is masquerading as humanity, but that’s not what it is. Civilization is only one sort of cultural plan, a way of creating unsustainably large human settlements, based entirely on agriculture which itself is completely unsustainable.

The argument that militant actions are counterproductive has a little bit of merit because the scale they’ve happened on hasn’t been large enough to have any impact. For example, the Earth Liberation Front burning SUV’s. You’re left with the political fallout, the mainstream activists distancing themselves and all the other bad stuff that comes with it, but you don’t have any measurable gain, in reducing carbon emissions, say. Sabotage needs to happen on a larger scale, against more expensive targets, to be impactful. Fighters need to think big. That’s how militaries accomplish their goals—by acting against systems. They blow up bridges, they take out buildings, they disable the enemy arsenal, they kill the enemy—that’s how they function. I agree activists don’t want to identify with militarism, but it’s foolhardy to not consider what’s actually going to get the job done, and militaries know how to do that. No moral code will matter if the biosphere collapses. Doctrinal non-violence isn’t going to have any relevance in a world that’s 20 degrees hotter than it is now.

I wish an effective movement could be nonviolent, but we just don’t have enough social cohesion to orchestrate that kind of thing. There’s so few of us who give a shit, and we’re scattered, isolated, and disenfranchised. We don’t have adequate numbers, influence, or power, and I don’t see that changing. Everywhere we look we’re losing, because we don’t have a movement that can say, “No. You’re not going to do that. We will stop this, whatever it takes,” and back that up. Aboveground activists need to advocate a lesser evil, to continually pose the question of what is worse: that some property was destroyed, or that sea shells are dissolving in acid oceans? Underground activists need to act that out. It’s not a rhetorical question.

We need to remember, too, that small numbers of people can engineer profound changes when their actions are wisely leveraged. Very few took part in the resistance movements of World War II, but they made all the difference to ultimately defeating the Axis.

Interview continues here.

Time is Short: Reports, Reflections & Analysis on Underground Resistance is a bulletin dedicated to promoting and normalizing underground resistance, as well as dissecting and studying its forms and implementation, including essays and articles about underground resistance, surveys of current and historical resistance movements, militant theory and praxis, strategic analysis, and more. We welcome you to contact us with comments, questions, or other ideas at undergroundpromotion@deepgreenresistance.org

by DGR News Service | Oct 7, 2014 | Repression at Home

By Deep Green Resistance Steering Committee

Recently, persons working for the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation and the Joint Terrorism Task Force have contacted multiple DGR members by phone and in-person visits to their homes. These agents attempted to get members to talk about their involvement with DGR, have asked for permission to enter members’ homes, and contacted members’ families.

DGR strategy and community rests upon a diligent adherence to security culture – a set of principles and behavior norms meant to help increase the safety of resistance communities in the face of state repression. All members are required to review and agree to our guidelines upon requesting membership, and we routinely hold org-wide refresher calls to remind everyone. We understand that while these guidelines can help increase our safety from state repression, unfortunately we cannot ever guarantee complete protection.

DGR is strictly an aboveground organization. As per our code of conduct, our members do not engage in underground or extra-legal tactics, and any member who violates our code of conduct forfeits their DGR membership. We advocate for a strategy that can effectively address the converging threats to the living world. Such a strategy is a threat to the ruling system, and state repression should be expected. DGR is dedicated to remaining effective while also doing all we can to increase member safety. We will not be intimidated into compromising our work, and we remain committed to amplifying the voice of resistance against injustice and ecocide.

Read our security culture guidelines.

by DGR News Service | Jun 21, 2014 | Gender, Repression at Home

By Max Wilbert / Deep Green Resistance

Despite the seeming popularity of environmental and social justice work in the modern world, we’re not winning. We’re losing. In fact, we’re losing really badly. [1]

Why is that?

One reason is because few popular strategies pose real threats to power. That’s not an accident: the rules of social change have been clearly defined by those in power. Either you play by the rules — rules which don’t allow you to win — or you break free of the rules, and face the consequences.

Play By The Rules, or Raise the Stakes

We all know the rules: you’re allowed to vote for either one capitalist or the other, vote with your dollars,[2] write petitions (you really should sign this one), you can shop at local businesses, you can eat organic food (if you can afford it), and you can do all kinds of great things!

But if you step outside the box of acceptable activism, you’re asking for trouble. At best, you’ll face ridicule and scorn. But the real heat is reserved for movements that pose real threats. Whether broad-based people’s movements like Occupy or more focused revolutionary threats like the Black Panthers, threats to power break the most important rule they want us to follow: never fight back.

State Tactic #1: Overt Repression

Fighting back – indeed, any real resistance – is sacrilegious to those in power. Their response is often straightforward: a dozen cops slam you to the ground and cuff you; “less-lethal” weapons cover the advance of a line of riot police; the sharp report of SWAT team’s bullets.

This type of overt repression is brutally effective. When faced with jail, serious injury, or even death, most don’t have the courage and the strategy to go on. As we have seen, state violence can behead a movement.

That was the case with Fred Hampton, an up-and-coming Black Panther Party leader in Chicago, Illinois. A talented organizer, Hampton made significant gains for the Panthers in Chicago, working to end violence between rival (mostly black) gangs and building revolutionary alliances with groups like the Young Lords, Students for A Democratic Society, and the Brown Berets. He also contributed to community education work and to the Panther’s free breakfast program.

These activities could not be tolerated by those in power: they knew that a charismatic, strategic thinker like Hampton could be the nucleus of revolution. So, they decided to murder him. On December 4, 1969, an FBI snitch slipped Hampton a sedative. Chicago police and FBI agents entered his home, shot and killed the guard, Mark Clark, and entered Hampton’s room. The cops fired two shots directly into his head as he lay unconscious. He was 21 years old.

The Occupy Movement, at its height, posed a threat to power by making the realities of mass anti-capitalism and discontent visible, and by providing physical focal points for the dissent that spawns revolution. While Occupy had some issues (such as the difficulties of consensus decision-making and generally poor responses to abusive behavior inside camps), the movement was dynamic. It claimed physical space for the messy work of revolution to happen, and represented the locus of a true threat.

The response was predictable: the media assaulted relentlessly, businesses led efforts to change local laws and outlaw encampments, and riot police were called in as the knockout punch. It was a devastating flurry of blows, and the movement hasn’t yet recovered. (Although many of the lessons learned at Occupy may serve us well in the coming years).

State Tactic #2: Covert Repression

Violent repression is glaring. It gets covered in the news, and you can see it on the streets. But other times, repression isn’t so obvious. A recent leaked document from the private security and corporate intelligence firm Strategic Forecasting, Inc. (better known as STRATFOR) contained this illustrative statement:

Most authorities will tolerate a certain amount of activism because it is seen as a way to let off steam. They appease the protesters by letting them think that they are making a difference — as long as the protesters do not pose a threat. But as protest movements grow, authorities will act more aggressively to neutralize the organizers.

The key word is neutralize: it represents a more sophisticated strategy on behalf of power, a set of tactics more insidious than brute force.

Most of us have probably heard about COINTELPRO (shorthand for Counter-Intelligence Program), a covert FBI program officially underway between 1956 and 1971. COINTELPRO mainly targeted socialists and communists, black nationalists, Civil Rights groups, the American Indian Movement, and much of the left, from Quakers to Weathermen. The FBI used four main techniques to undermine, discredit, eliminate, and otherwise neutralize these threats:

- Force

- Harassment (subpoenas, false accusations, discriminatory enforcement of taxation, etc.)

- Infiltration

- Psychological warfare

How can we become resilient to these threats? Perhaps the first step is to understand them; to internalize the consequences of the tactics being used against us.

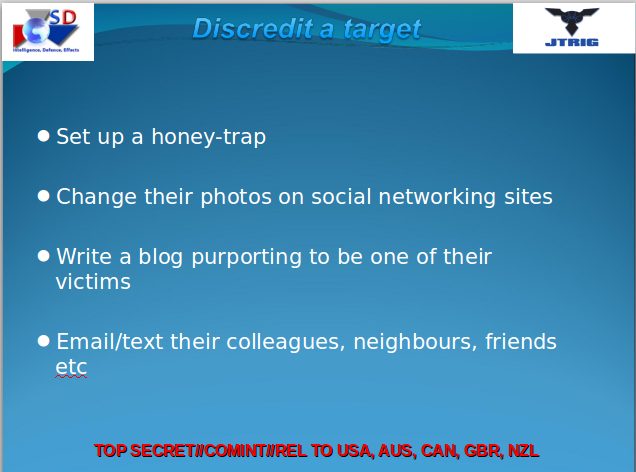

The JTRIG Leaks

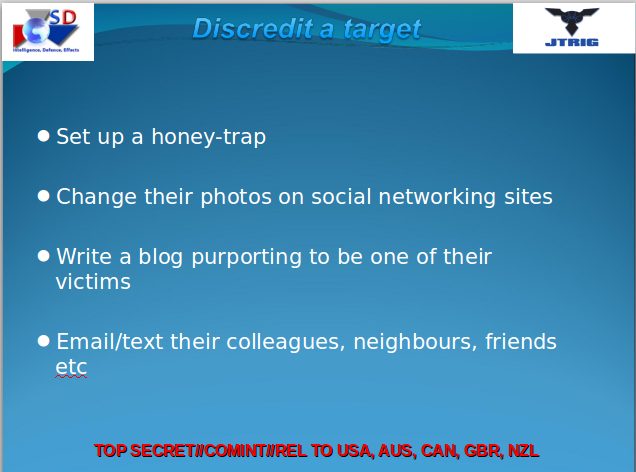

On February 24 of this year, Glenn Greenwald released an article detailing a secret National Security Agency (NSA) unit called JTRIG (Joint Threat Research Intelligence Group). The article, which sheds new light on the tactics used to suppress social movements and threats to power, is worth quoting at length:

Among the core self-identified purposes of JTRIG are two tactics: (1) to inject all sorts of false material onto the internet in order to destroy the reputation of its targets; and (2) to use social sciences and other techniques to manipulate online discourse and activism to generate outcomes it considers desirable. To see how extremist these programs are, just consider the tactics they boast of using to achieve those ends: “false flag operations” (posting material to the internet and falsely attributing it to someone else), fake victim blog posts (pretending to be a victim of the individual whose reputation they want to destroy), and posting “negative information” on various forums.

It shouldn’t come as a total surprise that those in power use lies, manipulation, false information, fake identities, and “manipulation [of] online discourse” to further their ends. They always fight dirty; it’s what they do. They never fight fair, they can never allow truth to be shown, because to do so would expose their own weakness.

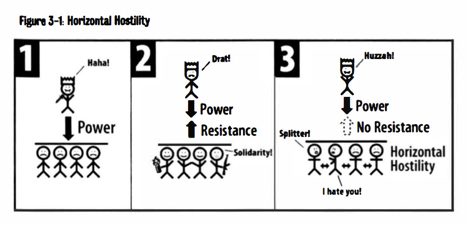

As shown by COINTELPRO, this type of operation is highly effective at neutralizing threats. Snitchjacketing and divisive movement tactics were used widely during the COINTELPRO era, and encouraged activists to break ties, create rivalries, and vie against one another. In many cases, it even led to violence: prominent, good hearted activists would be labeled “snitches” by agents, and would be isolated, shunned, and even killed.

As a friend put it,

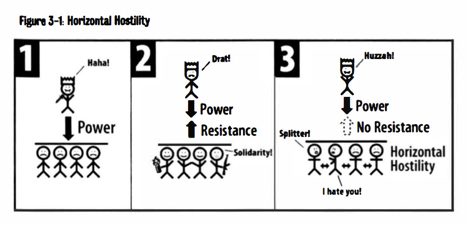

“By encouraging horizontal, crowdsourced repression, activists’ focus is shifted safely away from those in power and towards each other.”

Are Activists Targeted?

Some organizations have ideas so revolutionary, so incendiary that they pose a threat all by themselves, simply by existing.

Deep Green Resistance is such a group. If these tactics are being used to neutralize activist groups, then Deep Green Resistance (DGR) seems a prime target. Proudly Luddite in character, DGR believes that the industrial way of life, the soil-destroying process known as agriculture, and the social system called civilization are literally killing the planet – at the rate of 200 species extinctions, 30 million trees, and 100 million tons of CO2 every day. With numbers like that, time is short.

With two key pieces of knowledge, the DGR strategy comes into focus. The first is that global industrial civilization will inevitably collapse under the weight of its own destructiveness. The second is that this collapse isn’t coming soon enough: life on Earth could very well be doomed by the time this collapse stops the accelerating destruction.

With these understandings, DGR advocates for a strategy to pro-actively dismantle industrial civilization. The strategy (which acknowledges that resisters will face fierce opposition from governments, corporations, and those who cling to modern life) calls for direct attacks on critical infrastructure – electric grids, fossil fuel networks, communications, etc. – with one goal: to shut down the global industrial economy. Permanently.

The strategy of direct attacks on infrastructure has been used in countless wars, uprisings, and conflicts because it is extremely effective. The same strategies are taught at military schools and training camps around the planet, and it is for this reason – an effective strategy – that DGR poses a real and serious threat to power. Of course, writing openly about such activities and then taking part in them would be stupid, which is why DGR is an “aboveground” organization. Our work is limited to building a culture of resistance (which is no easy feat: our work spans the range of activities from non-violent resistance to educational campaigns, community organizing, and building alternative systems) and spreading the strategies that we advocate in the hope that clandestine networks can pull off the dirty work in secret.

When I speak to veterans – hard-jawed ex-special forces guys – they say the strategy is good. It’s a real threat.

Threat Met With Backlash

That threat has not gone unanswered. In a somewhat unsurprising twist, given the information we’ve gone over already, DGR’s greatest challenges have not come from the government, at least not overtly. Instead, the biggest challenges have come from radical environmentalists and social justice activists: from those we would expect to be among our supporters and allies. The focal point of the controversy? Gender.

The conflict has a long history and deserves a few hours of discussion and reading, but here is the short version: DGR holds that female-only spaces should be reserved for females. This offends many who believe that male-born individuals (who later come to identify as female) should be allowed access to these spaces. It’s all part of a broader, ongoing disagreement between gender abolitionists (like DGR and others), who see gender as the cultural lattice of women’s oppression, and those who view gender as an identity that is beyond criticism.

(To learn more about the conflict, view Rachel Ivey’s presentation entitled The End of Gender.)

Due to this position, our organization has been blacklisted from speaking at various venues, our organizers have received threats of violence (often sexualized), and our participation in a number of struggles has been blocked – at the expense of the cause at hand.

A Case Study in JTRIG?

Much of the anti-DGR rhetoric has been extraordinary, not for passionate political disagreement, but for misinformation and what appears to be COINTELPRO-style divisiveness. Are we the victims of a JTRIG-style smear campaign?

On February 23 of this year, the Earth First! Newswire released an anonymous article attacking Deep Green Resistance. The main subject of the article was the ongoing debate over gender issues.

(Although perhaps debate is the wrong word in this case: Earth First! Newswire has published half a dozen vitriolic pieces attacking DGR. They seem to have an obsession. On the other hand, DGR has never used organizational resources or platforms to publish a negative comment about Earth First.)

Here are a few of the fabrications contained in the February 23 article:

- “Keith and Jensen [DGR co-founders] do not recognize the validity of traditionally marginalized struggles [like] Black Power.” (a wild, false claim, given the long and public history of anti-racist work and solidarity by those two. [3])

- DGR members have “outed” transgender people by posting naked photos of them. (Completely false not to mention obscene and offensive.[4])

- DGR is “allied with” gay-to-straight conversion camps. (The lies get ever more absurd. DGR has countless lesbian and gay members, including founding members. Lesbian and gay members are involved at every level of decision making in DGR.)

- DGR requires “genital checks” for new members. (I can’t believe we even have to address this – it’s a surreal accusation. It is, of course, a lie.)

If these claims weren’t so serious, they would be laughable. But lies like this are no laughing matter.

Here is one illustrative list of tactics from the JTRIG leaks:

“Crowdsourced Repression”

The timing of these events – the Earth First! Newswire article followed the very next day by Greenwald’s JTRIG article – is ironic. Of course, it made me think: are we the victims of a JTRIG-style character assassination? Or am I drawing conclusions where there are none to be drawn?

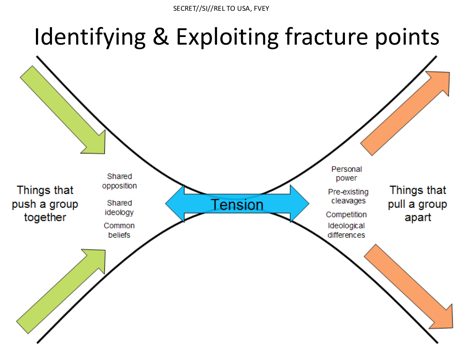

The campaigns against DGR do have many of the hallmarks of COINTELPRO-style repression. They are built on a foundation of political differences magnified into divisive hatred through paranoia and the spread of hearsay. In the 1960s and 70s, techniques that seem similar were used to create divisions within groups like the Black Panthers and the American Indian Movement.

Ultimately, these movements tore themselves apart in violence and suspicion; the powerful were laughing all the way to the bank. In many cases, we don’t even know if the FBI was involved; what is certain is that the FBI-style tactics – snitchjacketing, rumormongering, the sowing of division and hatred – were being adopted by paranoid activists.

In some ways, the truth doesn’t really matter. Whether these activists were working for the state or not, they served to destroy movements, alliances, and friendships that took decades or generations to build.

I’ll be clear: I don’t mean to claim that the “Letter Collective” (as the anonymous authors of the February 23 article named themselves) are agents of the state. To do so would be a violation of security culture. [5] Modern activists seem to have largely forgotten the lessons of COINTELPRO, and I am wary of forgetting those lessons myself. Snitchjacketing is a bad behavior, and we should have no tolerance for it unless there is substantive evidence.

But members of the “Letter Collective”, at the very least, have violated security culture by spreading rumors and unsubstantiated claims of serious misconduct. Good security culture practices preclude this behavior. In the face of JTRIG and the modern surveillance and repression state, careful validation of serious claims is the least that activists can do. Didn’t we learn this lesson in the 60s?

Divide and Conquer

By itself, verifying rumors before spreading them is a poor defense against the repression modern activists face. Instead, we must challenge divisiveness itself: one of the biggest threats to our success.

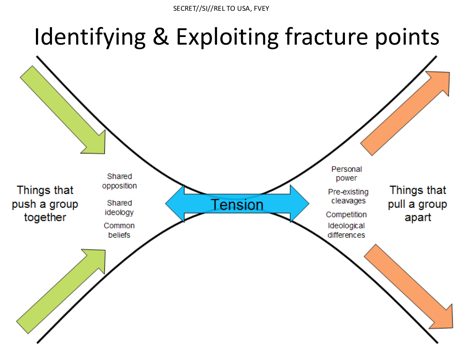

The 2011 STRATFOR leak included information about corporate strategies to neutralize activist and community movements. Essentially, STRATFOR advocates dividing movements into four character types: radicals, idealists, realists, and opportunists. These camps can then be dealt with summarily:

First, isolate the radicals. Second, “cultivate” the idealists and “educate” them into becoming realists. And finally, co-opt the realists into agreeing with industry. [6]

This is how movements are neutralized: those who should be allies are divided, infighting becomes rampant, and paranoia rules the roost. To combat these strategies, we must understand the danger they represent and how to counter them.

Fight Repression With Solidarity

We all want to win. We want to end capitalism, reverse ecological collapse, and build a culture in which social justice is fundamental. Many of us have different specific goals or strategies, but we must find similarities, overlaps, and areas where we can work together.

As Bob Ages, commenting on STRATFOR’s divide-and-conquer tactics, put it in a recent piece:

“Our response has to be the opposite; bridging divides, foster mutual understanding and solidarity, stand together come hell or high water.”

Many people across the left share 80% or more of their politics, and yet constructive criticism and mature discussion of disagreements is the exception, not the rule. We need more thoughtful behavior. Don’t spread rumors, don’t tear down other activists, and don’t forget who the real enemy is. Don’t waste your time fighting those who should be your allies – even if they are only partial allies. Let’s disagree, and let our disagreements help us learn more from each other and build alliances.

In the end, that’s our only chance of winning: together.

References

Max Wilbert lives in the Pacific Northwest, where he works to support indigenous resistance to industrial extraction projects, anti-racist initiatives, and radical feminist struggles as part of Deep Green Resistance. He makes his living as a writer and photographer, and can be contacted at max@maxwilbert.org.

From Dissident Voice

by DGR News Service | Apr 21, 2014 | Repression at Home

By Jeremy Hance / Mongabay

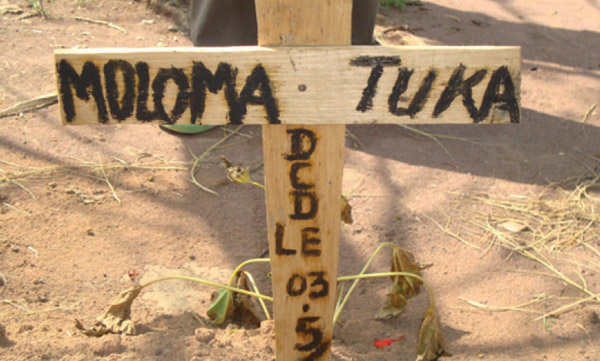

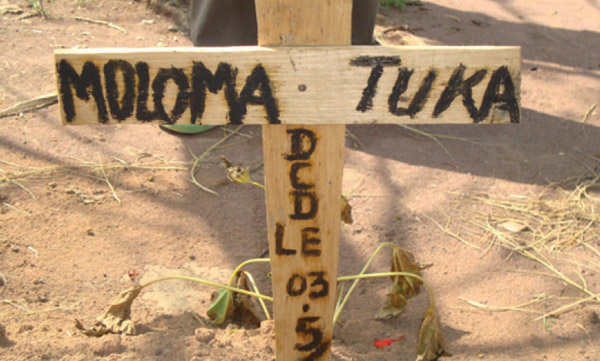

At least 908 people were murdered for taking a stand to defend the environment between 2002 and 2013, according to a new report today from Global Witness, which shows a dramatic uptick in the murder rate during the past four years. Notably, the report appears on the same day that another NGO, Survival International, released a video of a gunman terrorizing a Guarani indigenous community in Brazil, which has recently resettled on land taken from them by ranchers decades ago. According to the report, nearly half of the murders over the last decade occurred in Brazil—448 in all—and over two-thirds—661—involved land conflict.

“There can be few starker or more obvious symptoms of the global environmental crisis than a dramatic upturn in killings of ordinary people defending rights to their land or environment,” said Oliver Courtney of Global Witness. “Yet this rapidly worsening problem is going largely unnoticed, and those responsible almost always get away with it. We hope our findings will act as the wake-up call that national governments and the international community clearly need.”

But as grisly as the report is, it’s likely a major underestimation of the issue. The report covers just 35 countries where violence against environmental activists remains an issue, but leaves out a number of major countries where environmental-related murders are likely occurring but with scant reporting.

“Because of the live, under-recognized nature of this problem, an exhaustive global analysis of the situation is not possible,” reads the report. “For example, African countries such as Nigeria, Democratic Republic of Congo, Central African Republic and Zimbabwe that are enduring resource-fueled unrest are highly likely to be affected, but information is almost impossible to gain without detailed field investigations.”

In fact, reports of hundreds of additional killings in countries like Ethiopia, Myanmar, Venezuela, and Zimbabwe were left out due to lack of rigorous information.

Even without these countries included, the number of environmental activists killed nearly approaches the number of journalists murdered during the same period—913—an issue that gets much more press. Environmental activists most at risk are people fighting specific industries.

“Many of those facing threats are ordinary people opposing land grabs, mining operations and the industrial timber trade, often forced from their homes and severely threatened by environmental devastation,” reads the report. “Indigenous communities are particularly hard hit. In many cases, their land rights are not recognized by law or in practice, leaving them open to exploitation by powerful economic interests who brand them as ‘anti-development’.”

As if to highlight these points, Survival International released a video today that the groups says shows a gunman firing at the Pyelito Kuê community of Guarani indigenous people. The incident injured one woman, according to the group. The Guarani have been campaigning for decades to have land returned to them that has been taken by ranchers.

“This video gives a brief glimpse of what the Guarani endure month after month—harassment, intimidation, and sometimes murder, just for trying to live in peace on tiny fractions of the ancestral land that was once stolen from them,” the director of Survival International, Stephen Corry, said. “Is it too much to expect the Brazilian authorities, given the billions they’re spending on the World Cup, to sort this problem out once and for all, rather than let the Indians’ misery continue?”

According to the report, two major drivers of repeated violence against environmental activists are a lack of attention to the issue and widespread impunity for perpetrators. In fact, Global Witness found that only ten people have been convicted for the 908 murders documented in the report, meaning a conviction rate of just 1.1 percent to date.

“Environmental human rights defenders work to ensure that we live in an environment that enables us to enjoy our basic rights, including rights to life and health,” John Knox, UN Independent Expert on Human Rights and the Environment said. “The international community must do more to protect them from the violence and harassment they face as a result.”

From Mongabay: “Nearly a thousand environmental activists murdered since 2002“

by DGR News Service | Feb 24, 2014 | Rape Culture, Repression at Home

By William Falk / Deep Green Resistance

The San Diego Police Department scares me. All police, for that matter, scare me.

I’m writing this because I cannot drown out the sharp pops of a burst of police gunfire hanging on the still desert air.

I heard the eerily common sound of gunshots as I watched a video of police shooting an unarmed 20 year-old black man named D’Andre Berghardt near Red Rock Canyon in Nevada the other day with my partner.

A few days before viewing the video, we were on our way to Red Rock Canyon for a rock-climbing trip with friends. Highway 159 provides access to the canyon, but was closed due to a “police incident.” We made a mental note to check on the incident when we got home.

Back at home, safe on our couch in the living room, we started the video. The video was taken by two men sitting in their car as the entire encounter unfolded. You can see three or four cars stopped with drivers gawking on. There is even a bicyclist sitting on her bike seat calmly absorbing the scene.

The video opened with two officers, guns drawn, on either side of Berghardt. The officers spoke with Berghardt for a minute or so. Our disbelief grew as one officer pepper sprayed Berghardt. I paused the video to explain I’ve read that pepper spray often makes people vomit. A moment later, we watched Berghardt double over. We listened to the men taking the video asking, “Why don’t they just cuff him?” Then we watched as the officers taser Berghardt. I stopped the video again to say that tasering often causes the recipient to defecate in his or her pants. A few of the cars started turning around and driving past the scene.

Finally, my partner who is much braver than me and much more vocal, yelled out, “Why doesn’t some one do something!?”

All I could manage to say was, “I would be scared. The cops have their guns out. I’m not talking to a cop with his gun drawn.”

Then we finished the video as Berghardt eventually ran from officers who had pepper sprayed him and tasered him into an open police vehicle before being shot multiple times from a few feet away. Then, he died.

After watching the video, we learned that Berghardt had been walking down Highway 159 asking cyclists for water and telling them to “have a good ride.”

And now: I cannot drown out the sharp pops of a burst of police gunfire hanging on the still desert air.

It is time that we do something.

***

I’m writing this because I cannot drown out the voices of the women who have so bravely – despite tears, shaking voices, traumatic recollections, and even government-paid stalkers – told their stories of sexual assault at the hands of the SDPD.

With the recent news that the City Attorney’s office paid a private investigator to follow for 23 days and videotape one of former SDPD Officer Anthony Arrevalos’ sexual assault victims and now the news that another SDPD officer, Chris Hays, has been arrested on suspicion of committing false imprisonment and misdemeanor sexual battery while on duty, my fear of the police is growing stronger and stronger.

These disturbing sexual abuse allegations (and convictions) are not just here in San Diego, either. A quick Google search shows that almost identical cases of abuse are happening all over the country. Do any of these stories sound familiar? A few weeks ago in Dallas an officer allegedly told a woman he wouldn’t take her to jail if she would have sex with him. Last summer a school police officer in Eugene, OR was convicted of sexually abusing six women while on-duty and off-duty and several more women came forward after conviction. And, in Chicago, two officers are accused of raping a woman they offered a ride home while on-duty.

I have to be honest. I’ve never liked the police. It started when I was younger. I’ve always worn my hair long and have been pulled over too many times to have a cop let me go after explaining, “You have to admit, you do look like you probably have drugs on you.”

Then, I became a public defender, and learned first hand just how bad the police can be. There were too many times when I requested video evidence from squad car cameras only to find the officer ‘forgot’ to turn the camera on. Too many times I overheard senior officers telling junior officers how to testify in the hallway before hearings. Too many times I watched as police officers were cleared of claims of excessive force. Too many times I’ve seen women coming forward to report sexual abuse at the hands of police officers.

***

I’m afraid of the police. I’m particularly afraid of the SDPD because I live here, and because we keep getting report after report of their violence.

I’m also very angry. There are people who are responding to criticisms of the police with the tired rebuttal “If you don’t do anything wrong, you don’t have anything to be afraid of.”

D’Andre Berghardt wasn’t doing anything wrong. The women in Eugene, OR assaulted by a school cop weren’t doing anything wrong. The woman who took a ride home from police officers before being raped by both of them wasn’t doing anything wrong.

And what about the definition of “wrong?” It’s not wrong to smoke recreational marijuana in Washington, but it is in most of the rest of the country. Many states still have anti-sodomy laws on the books. It was wrong at one time in this country to harbor run away slaves.

And what about when the right thing to do is “wrong”? For example, who do you think is going to show up first with guns drawn if outraged citizens decided to dismantle California’s fracking sites? Who showed up at Wounded Knee in 1973 when indigenous peoples demanded the federal government honor their treaties? Who murdered Fred Hampton? Who smuggled cocaine from Nicaragua into the US? Who is teaching children to shoot likenesses of immigrants at the border? Who is shooting the immigrants?

I am afraid of the police. You should be, too, even if you’re doing nothing wrong. They will throw their phony reports at us. They will harass us if we speak too loudly. Their City Attorney will send stalkers to report on our sexual habits. And, yes, they might even point their guns at some of us.

But, we must be brave.

It is time that we do something.

From San Diego Free Press: http://sandiegofreepress.org/2014/02/im-afraid-of-the-sdpd/

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 15, 2014 | Obstruction & Occupation, Repression at Home

By Cal Winslow

Will Parrish needs your support. He now faces eight years in prison; in addition, $490,000 in fines, “restitution”. And for what? For delaying a freeway, the “Redwood Highway” – the California 101.

Parrish is a journalist here in Willits, in Mendocino County. He is also an activist and a teacher. His trial is scheduled for the County Courthouse in Ukiah, at 8:30 AM, on January 28th.

Will’s crime must be peculiarly Californian, a crime against a freeway. It must, from the grave, be raising Ronald Reagan’s hackles, jolting his memory. We’re told, incessantly in the media, this delay also enrages our ordinary travelers; drivers, it seems, now delayed five minutes (or so) along the main street of Willits on the trip to Eureka.

Willits, Eureka, Mendocino, Humboldt, why here? In this wildest corner of the state? “California’s transportation infrastructure – once the freeway wonder of the world – now lags hopelessly behind…”, Mike Davis tells us this, and quite rightly, but you can’t say they’re not trying. The issue here is a bypass.

Mike’s down south, where the people are. Things are different here. There are fewer than 5000 people in Willits, its population in decline; there are just about 90,000 people in Mendocino County, a few more than in new Mayor Bill De Blasio’s Brooklyn neighborhood. But this is a big County, nearly 100 miles south to north. We have lots of elbow room. And that’s Mendocino; take 101 north and there’s hardly anyone at all. The shrewd driver, once in southern Humboldt, can easily make up the time. Then it’s the supermax at Pelican Bay in nothing flat.

But it doesn’t matter, it’s systemic. Caltrans, the state’s mega transportation department is pushing the bypass at Willits; it’s wanted it for a long time. It’s for our own good, of course. And Caltrans has a plan. A master plan? Indeed it’s had this very plan for twenty years (it seems it’s always a good time for a new freeway). Caltrans has proposed and is now building a $200 million, six mile, four-lane freeway the size of Interstate 5.

Willits is “the Gateway to the Redwoods”, drivers learn this from a large arch they pass under (not from actual trees). They also navigate a five mile stretch of two lane traffic, two lights, then an array of shops, etc., few really worth slowing down for. The one real problem, let’s be fair here, is the snag where state route 20, at Safeway and a light, turns off to Fort Bragg and the Coast. It is a bottleneck. I’ve seen rush hour traffic backed up two or three blocks, delays of five minutes or so. But let’s have some perspective on this. We’re out in the country, on our way to the Redwoods, the few remaining. We’re just not talking about the BQE on Monday morning or the Santa Monica Freeway on Tuesday nights.

So $200 million? California is just clawing itself out of the recession. We’ve hardly had time to catch our breath, how will we undo the damage done to our schools, our services, our health and welfare? Costs still figure even here, even in this latest boomlet. Caltrans likes to keep it quiet, but the first stage of the freeway bypass will be only two lanes, though construction will prepare for an eventual four. Back to Mike Davis, there’s something more than meets the eye here, something “primal”.

Good, sensible people in Willits have been fighting the bypass here for twenty years; they’ve challenged Caltrans every foot of the way – they’ve demanded proper public input, attention to environmental regulations, a haven for rare birds, and protection of wetlands, this last elemental, primary in terms of survival here in (too) thirsty California. It’s amazing, the persistence of these people. And they’ve been willing to seek compromises – perhaps a smaller project. But Caltrans has been patient too (and with 22,000 employees, the state’s huge contractors on your side, also the local politicians, building trades unions, etc., I suppose it’s easy to be patient).

Will Parish is a new-comer of sorts to this (a new-comer in California? Is that an oxymoron?). He’s been up here in Mendocino County for just four years, and we’re very lucky for it. Will grew up in Santa Cruz, his parents teachers, his home fronting a Redwood forest, his childhood sanctuary. Will went to UC Santa Cruz, majoring there in Sociology and Journalism. The administration apparently considered the Journalism School a problem (a sure sign it was doing its job), and used the 2003 round of cuts to get rid of it. Will reckons he’s the last of its graduates.

Will, as a journalist, sought out issues of power and war; he dug into the roots of the Bay Area’s war connections, in particular those in the UC system – no shortage of material there. Nuclear weapons, nuclear power appalled him. And he combined writing with activism; he is a journalist in the best tradition of our muckrakers, a writer “with his boots on the ground”. This is a good expression, I think; I’m taking it from my mentor, the late Edward Thompson, in his own time a relentless opponent of the war machine, of nuclear weapons in particular, writer and activist.

Close Counterpunch readers will remember Will’s many contributions including: How Imperial San Franciscans Loot the Planet (February 26-28 2010 with Darwin Bond-Graham) and Who Runs the University of California? (March 01, 2010 with Bond-Graham). And here in wine country his focus has been the burgeoning wine industry: see pieces including In the Shadow of the Gallos; Sonoma County, Banana Republic of Wine Grapes (January 21-23, 2011).

In Mendocino Will began with a focus has been the burgeoning wine industry, its owners, its workers and its place in the economy (see, for example, In the Shadow of the Gallos; Sonoma County, Banana Republic of Wine Grapes, Counterpunch, January 21-23, 2011). And on the wetlands of the Little Lake Valley.

“When I first came here, Willits, I fell in love with the tranquility here, with the mountains, the boggy marshes, the grasslands, the eco-diversity, the space. And no freeway. The 101 stops just south of Willits – that makes it a different world here.

“My journalism, my practice, has always been to scan the horizon, to look for the most pressing problems, to look for the problems that most need addressing.

“The bypass issue struck me as a really big problem, a thing that really needed addressing. And that meant getting involved; I can’t write and not be involved.” (See “The Insanity of the Willits Bypass”, in the Ukiah Blog, January 8th, 2013)

Here’s an example:

“As Willits’ settlers set about gridding the land and marketing it to cattle ranchers and timber merchants, they rapidly removed the wetlands. They did the same to the Pomo villagers and wildlife — waterfowl, pelicans, vast herds of Tule elk and antelope, etc. — that had dwelled among the marshes and springs for so long. The early Euroamerican pioneers incised streambeds, redirected creeks, constructed artificial drainage ditches, and ripped apart the hardpan layers of topsoil that contained the water, allowing it to seep slowly into the ground.

“Some of the moisture that time had stored on the land remains, though, most notably within the marshy area on the north end of the valley, extending across Route 101 on the west and Reynolds Highway on the east. The area acts as a collection point for three creeks that flow through the valley. It is then drained by Outlet Creek, a tributary of the Eel River. Among its other contributions to what might be called the “real world” of inland Mendocino County, Outlet Creek provides the longest remaining run for the endangered Coho salmon of any river tributary in California.

In June, Will climbed a wick drain “stitcher”, a giant machine there to plant tens of thousands of drainage tubes along the path of freeway construction, tubes to drain the wetlands and stabilize the earth upon which the highway will be built – in the process destroying Little Lake Valley wetlands, the largest Northern California wetlands to be drained in any single project in the past fifty years. So David and Goliath again. Will: “Caltrans is a scofflaw agency that, by virtue of a failed political and regulatory system, is facing no other forms of real accountability for causing immense and probably irreversible destruction of Little Lake Valley.”

An important argument in this entire conflict is that the whole project is illegal, Caltrans having violated nearly every regulation possible.

“I threw myself in because the more I came to understand this the more upset I became. The Willits project epitomizes so much of everything that is wrong; it epitomizes the power dynamics that underlie all the problems I see in society.”

Will lived on a platform, more than fifty feet up, for eleven days. Will is six foot five, no, not a basketball player, rather tennis, a large, attentive, kind man, hair flowing like Clay Matthew’s, only dark brown. Gentle, yes. Passive, no. Will on the stitcher was a figure not to be missed. And the California Highway Patrol (CHP) took every precaution in bringing him down – precaution meaning that they overwhelmed him, attacking with swat teams, climbing specialists (a career path), hoisted in giant bucket loaders, prepared with saws specifically designed to cut him loose. But not until the entire project had been halted.

This story has not generated the emotion, the energy of Julia Butterfly Hill’s but it demands our attention, as do dozens of such projects here in California’s Northwest. They are fundamental contests. They are about our future. In the stitcher Will lived in a sort of house arrest, surrounded on the ground by dozens of the small army of CHP troopers brought into Willits. He was deprived of food; the CHP even arrested six people who attempted to bring him supplies. He went six days without food, surviving an unseasonal rain storm, also bitter cold.

Construction started in February, 2013, but was delayed until spring. Will was not the first to be arrested. There were others, tree sitters, people who sat down in the paths of bulldozers (West Bank weapons) – fifty people in all have been arrested, these people too demand our support. They include a core of those who have kept this crusade alive, all these years. In truth, it’s been a small group that has kept this issue alive; many were the young at heart – often 50, 60, even 70 year olds, but tenacious. Against them the troopers, the choppers, the armed vehicles.

Will is charged with trespassing, “unlawful entry”. (He is also charged with two “resisting arrests”.) So Will and his supporters expected him to be charged with two or three two misdemeanors. Some tree sitters have yet to be charged with anything. The Mendocino County District Attorney, David Eyster, typical of the small town bullies we suffer as DA’s, offered a plea bargain, but this left Will subject to restitution. Will refused, asked for a jury trial. Infuriated, Eyster made a package of the misdemeanors; charging Will instead with 16 misdemeanors, these with a cumulative maximum eight-year jail sentence. As it happens, Caltrans then piled on with a demand for $490.000.02 in restitution. The costs of delay!

I have heard it said that the sentence demanded in this case is unusual, harsh in nominally liberal and eco-friendly Mendocino County. True, this isn’t South Carolina, and it is also true that there is something of a history of tolerance in this County. And there is radicalism of a certain kind; many here are on alert for peak oil, Fukushima, broken bridges, marine protectors, black choppers. And thank heavens for it. But, for the few who will remember, Tony Craver and Norm Vroman are gone. Still, there is a curious way in which Eyster relates to the growers, so he often gets a pass. But he’s not on his own, he’s certainly not the only bully in the County, and he’s not the only one who is happy to not see our biggest industries’ bad behaviors.

Will has lived up to his self-pledge to seek out the most pressing problems, and to get to the bottom of them. In this case he’s found wetlands. And water, fundamentals for all California, and no small concern here in California, now in the grips of an historic drought. Wetlands take us to water and water to the growers. The grape growers here are not mom and pop operations; they are more likely Silicon Valley veterans, wealthy people with more money than they know what to do with. They come here to concoct boutique wines; but premium wine production touches everything, from the price of land to the very structure of labor, and not for the better. They create the groomed landscape that the Anderson Valley has become. But they also consume the water; now, as we await our rainy season, we have dry creeks and depleted rivers. And they bring pesticides, and all the nasty environmental procedures that are the unmentionables in an eco-friendly County. And these are not on David Eyster’s agenda. And salmon that still don’t come back. Will Parrish is our Lincoln Steffens (The Shame of the Cities, 1904). And they don’t like him.

There is a similar story with our biggest industry, that is, with “the crop”, marijuana. Of course it’s an underground economy; of course it has its victims, its innocents. Yet it too is extractive in the worst senses; it too drains our streams, poisons them, it drives up the price of land, it too takes the profits away. It creates our culture of secrecy; ask no questions, it stretches out the class divide while thriving on illusions of community. No wonder Mendocino is still a poor County, its schools struggle, its public services all but non-existent. Our “infrastructure” crumbles – our County roads? No help from Caltrans for these. And Will has had the courage to say this.

So why is Eyster being the bully? I think we have a conspiracy here, but it’s an open conspiracy, its origins, its cast of characters is right here for all to see. Caltrans wants roads, big roads; the builders want to build. Eyster’s job, grease the wheels. It’s systemic. Why would he not be the bully? A few examples will quiet things down, or so he seems to think. He’s got Will Parrish on deck.

The 101 is named the Redwood Highway and for good reason. Its construction began in the twenties – for us in the North it begins on the Golden Gate Bridge; it then passes through a series of lovely valleys until it reaches the mountains of northern Mendocino County, then it follows the South Fork of the Eel toward Eureka and on to the Oregon border. Its initial construction was promoted as a pathway to a tourist’s paradise, that is, the motoring tourist. It opened up a new world, magnificent yet until then inaccessible. The 101 had on offer – for those with cars – giant trees, raging wild rivers, steep canyons, rugged mountains, there to see, yet all without a step out the door.

There was another intention, however. By the twenties, the coastal Redwood forests were all but exhausted; the depression of the thirties put an end to the “harvest”. There remained, however, millions of acres of old growth Redwood, just out of reach of the coastal mills. Not, however, out of reach of the truck, the bulldozer and the chain saw. The 101 cleared the way that led to the final ravaging of the forest; in sheer destruction it far surpassed that of the late nineteenth century, though the old images – man vs. tree – still dominate our imagination of this history. The result, today fewer than four percent of the old growth survives. Second and third growth forests still are cut; there is farming. But the great Redwood forests, once a common of unimaginable value, a true wonder of the world, remain only terribly wounded, and almost all as private property, no trespassing.

This part of California, its “wildest” corner, grabs people, it moves them. It’s got Will and the Willits tree sitters, Warbler and the others, the bulldozer blockaders (I think of Rachel Corrie), its geriatric Wobblies facing down the troopers. And Willits is not the only site of conflict. Caltrans wants the road widened at Richardson Grove; it wants the road up to Oregon straightened. Never mind our remaining giant trees. Never mind the Smith River canyon, the path to the sea of California’s only undammed river.

I see the conspiracy when I drive home from the City, up the 101 to Cloverdale. It’s not hidden. The traffic on an afternoon is of course catastrophe in Northern Marin and on through Sonoma to Santa Rosa. So the solution? There are massive projects now in place, ever widening the highway, knocking down whatever is left in its path, so far almost to Windsor.

In its path, strip malls and giant box stores follow, one after another; sometimes it’s as if we’re in a tunnel of Mall. Then comes the sprawl.

And so it continues, the highways will soon be jammed again; Caltrans will push on northwards. Development. Plunder. Profit. It’s a “primal scene”, Mike Davis (Ecology of Fear) again. The widenings, the bypasses, these are “the familiar tremors heralding an eruption of growth that will wipe away human and natural history”.

Will and his comrades see this, the insanity of it all. They understand that this will not stop at Cloverdale or Ukiah. They understand the damage being done – “to human and natural history”.

The wetlands in Little Lake Valley are small, really; they have already been damaged by the agriculturalists of a century ago. Are they worth saving? I wondered if the Willits fighters had not perhaps exaggerated.

Counterpunch readers will recognize Ignacio Chapela as the microbial ecologist and mycologist at the University of California, Berkeley, known for exposure of the flow of transgenes into wild maize.

Ignacio explains, “The highland wetlands are the basis of the health of the whole environment, this includes all the ecosystems downstream, they are the basis for everything, our water, the diversity of species, everything is at stake.”

“Will is a young investigative reporter, one of a kind. He’s not afraid of pursuing questions to their ultimate consequence. It’s not surprising at all to me that he’s working on wetlands, he understands environmental problems deeply and has the unique capacity to make these clear in his writings.

“It would be a terrible loss for California, also for environmental journalists everywhere, if he is silenced – even slowed down.

“I want to do whatever I can to do to support him and I want invite everyone to join us.”

So do I.

————————-

Support Will in Court. Ukiah County Courthouse, 8:30 am, January 28, 2014

Send messages to: Mendocino District Attorney David Eyster at Eysterd@co.mendocino.ca.us

or to

Supervisor Fifth District, Dan Hamburg at Hamburgd@co.mendocino.ca.us

Contributions can be sent to: Little Lake Valley Legal Fund/Will Parrish, Box 131, Willits, CA 95490