by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Dec 1, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Decisive Ecological Warfare” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

There’s a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, makes you so sick at heart, that you can’t take part, you can’t even passively take part, and you’ve got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels, upon the levers, upon all the apparatus, and you’ve got to make it stop!

—Mario Savio, Berkeley Free Speech Movement

To gain what is worth having, it may be necessary to lose everything else.

—Bernadette Devlin, Irish activist and politician

BRINGING IT DOWN: COLLAPSE SCENARIOS

At this point in history, there are no good short-term outcomes for global human society. Some are better and some are worse, and in the long term some are very good, but in the short term we’re in a bind. I’m not going to lie to you—the hour is too late for cheermongering. The only way to find the best outcome is to confront our dire situation head on, and not to be diverted by false hopes.

Human society—because of civilization, specifically—has painted itself into a corner. As a species we’re dependent on the draw down of finite supplies of oil, soil, and water. Industrial agriculture (and annual grain agriculture before that) has put us into a vicious pattern of population growth and overshoot. We long ago exceeded carrying capacity, and the workings of civilization are destroying that carrying capacity by the second. This is largely the fault of those in power, the wealthiest, the states and corporations. But the consequences—and the responsibility for dealing with it—fall to the rest of us, including nonhumans.

Physically, it’s not too late for a crash program to limit births to reduce the population, cut fossil fuel consumption to nil, replace agricultural monocrops with perennial polycultures, end overfishing, and cease industrial encroachment on (or destruction of) remaining wild areas. There’s no physical reason we couldn’t start all of these things tomorrow, stop global warming in its tracks, reverse overshoot, reverse erosion, reverse aquifer drawdown, and bring back all the species and biomes currently on the brink. There’s no physical reason we couldn’t get together and act like adults and fix these problems, in the sense that it isn’t against the laws of physics.

But socially and politically, we know this is a pipe dream. There are material systems of power that make this impossible as long as those systems are still intact. Those in power get too much money and privilege from destroying the planet. We aren’t going to save the planet—or our own future as a species—without a fight.

What’s realistic? What options are actually available to us, and what are the consequences? What follows are three broad and illustrative scenarios: one in which there is no substantive or decisive resistance, one in which there is limited resistance and a relatively prolonged collapse, and one in which all-out resistance leads to the immediate collapse of civilization and global industrial infrastructure.

NO RESISTANCE

If there is no substantive resistance, likely there will be a few more years of business as usual, though with increasing economic disruption and upset. According to the best available data, the impacts of peak oil start to hit somewhere between 2011 and 2015, resulting in a rapid decline in global energy availability.1 It’s possible that this may happen slightly later if all-out attempts are made to extract remaining fossil fuels, but that would only prolong the inevitable, worsen global warming, and make the eventual decline that much steeper and more severe. Once peak oil sets in, the increasing cost and decreasing supply of energy undermines manufacturing and transportation, especially on a global scale.

The energy slide will cause economic turmoil, and a self-perpetuating cycle of economic contraction will take place. Businesses will be unable to pay their workers, workers will be unable to buy things, and more companies will shrink or go out of business (and will be unable to pay their workers). Unable to pay their debts and mortgages, homeowners, companies, and even states will go bankrupt. (It’s possible that this process has already begun.) International trade will nosedive because of a global depression and increasing transportation and manufacturing costs. Though it’s likely that the price of oil will increase over time, there will be times when the contracting economy causes falling demand for oil, thus suppressing the price. The lower cost of oil may, ironically but beneficially, limit investment in new oil infrastructure.

At first the collapse will resemble a traditional recession or depression, with the poor being hit especially hard by the increasing costs of basic goods, particularly of electricity and heating in cold areas. After a few years, the financial limits will become physical ones; large-scale energy-intensive manufacturing will become not only uneconomical, but impossible.

A direct result of this will be the collapse of industrial agriculture. Dependent on vast amounts of energy for tractor fuel, synthesized pesticides and fertilizers, irrigation, greenhouse heating, packaging, and transportation, global industrial agriculture will run up against hard limits to production (driven at first by intense competition for energy from other sectors). This will be worsened by the depletion of groundwater and aquifers, a long history of soil erosion, and the early stages of climate change. At first this will cause a food and economic crisis mostly felt by the poor. Over time, the situation will worsen and industrial food production will fall below that required to sustain the population.

There will be three main responses to this global food shortage. In some areas people will return to growing their own food and build sustainable local food initiatives. This will be a positive sign, but public involvement will be belated and inadequate, as most people still won’t have caught on to the permanency of collapse and won’t want to have to grow their own food. It will also be made far more difficult by the massive urbanization that has occurred in the last century, by the destruction of the land, and by climate change. Furthermore, most subsistence cultures will have been destroyed or uprooted from their land—land inequalities will hamper people from growing their own food (just as they do now in the majority of the world). Without well-organized resisters, land reform will not happen, and displaced people will not be able to access land. As a result, widespread hunger and starvation (worsening to famine in bad agricultural years) will become endemic in many parts of the world. The lack of energy for industrial agriculture will cause a resurgence in the institutions of slavery and serfdom.

Slavery does not occur in a political vacuum. Threatened by economic and energy collapse, some governments will fall entirely, turning into failed states. With no one to stop them, warlords will set up shop in the rubble. Others, desperate to maintain power against emboldened secessionists and civil unrest, will turn to authoritarian forms of government. In a world of diminishing but critical resources, governments will get leaner and meaner. We will see a resurgence of authoritarianism in modern forms: technofascism and corporation feudalism. The rich will increasingly move to private and well-defended enclaves. Their country estates will not look apocalyptic—they will look like eco-Edens, with well-tended organic gardens, clean private lakes, and wildlife refuges. In some cases these enclaves will be tiny, and in others they could fill entire countries.

Meanwhile, the poor will see their own condition worsen. The millions of refugees created by economic and energy collapse will be on the move, but no one will want them. In some brittle areas the influx of refugees will overwhelm basic services and cause a local collapse, resulting in cascading waves of refugees radiating from collapse and disaster epicenters. In some areas refugees will be turned back by force of arms. In other areas, racism and discrimination will come to the fore as an excuse for authoritarians to put marginalized people and dissidents in “special settlements,” leaving more resources for the privileged.2 Desperate people will be the only candidates for the dangerous and dirty manual labor required to keep industrial manufacturing going once the energy supply dwindles. Hence, those in power will consider autonomous and self-sustaining communities a threat to their labor supply, and suppress or destroy them.

Despite all of this, technological “progress” will not yet stop. For a time it will continue in fits and starts, although humanity will be split into increasingly divergent groups. Those on the bottom will be unable to meet their basic subsistence needs, while those on the top will attempt to live lives of privilege as they had in the past, even seeing some technological advancements, many of which will be intended to cement the superiority of those in power in an increasingly crowded and hostile world.

Technofascists will develop and perfect social control technologies (already currently in their early stages): autonomous drones for surveillance and assassination; microwave crowd-control devices; MRI-assisted brain scans that will allow for infallible lie detection, even mind reading and torture. There will be no substantive organized resistance in this scenario, but in each year that passes the technofascists will make themselves more and more able to destroy resistance even in its smallest expression. As time slips by, the window of opportunity for resistance will swiftly close. Technofascists of the early to mid-twenty-first century will have technology for coercion and surveillance that will make the most practiced of the Stasi or the SS look like rank amateurs. Their ability to debase humanity will make their predecessors appear saintly by comparison.

Not all governments will take this turn, of course. But the authoritarian governments—those that will continue ruthlessly exploiting people and resources regardless of the consequences—will have more sway and more muscle, and will take resources from their neighbors and failed states as they please. There will be no one to stop them. It won’t matter if you are the most sustainable eco-village on the planet if you live next door to an eternally resource-hungry fascist state.

Meanwhile, with industrial powers increasingly desperate for energy, the tenuous remaining environmental and social regulations will be cast aside. The worst of the worst, practices like drilling offshore and in wildlife refuges, and mountaintop removal for coal will become commonplace. These will be merely the dregs of prehistoric energy reserves. The drilling will only prolong the endurance of industrial civilization for a matter of months or years, but ecological damage will be long-term or permanent (as is happening in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge). Because in our scenario there is no substantive resistance, this will all proceed unobstructed.

Investment in renewable industrial energy will also take place, although it will be belated and hampered by economic challenges, government bankruptcies, and budget cuts.3 Furthermore, long-distance power transmission lines will be insufficient and crumbling from age. Replacing and upgrading them will prove difficult and expensive. As a result, even once in place, electric renewables will only produce a tiny fraction of the energy produced by petroleum. That electric energy will not be suitable to run the vast majority of tractors, trucks, and other vehicles or similar infrastructure.

As a consequence, renewable energy will have only a minimal moderating effect on the energy cliff. In fact, the energy invested in the new infrastructure will take years to pay itself back with electricity generated. Massive infrastructure upgrades will actually steepen the energy cliff by decreasing the amount of energy available for daily activities. There will be a constant struggle to allocate limited supplies of energy under successive crises. There will be some rationing to prevent riots, but most energy (regardless of the source) will go to governments, the military, corporations, and the rich.

Energy constraints will make it impossible to even attempt any full-scale infrastructure overhauls like hydrogen economies (which wouldn’t solve the problem anyway). Biofuels will take off in many areas, despite the fact that they mostly have a poor ratio of energy returned on energy invested (EROEI). The EROEI will be better in tropical countries, so remaining tropical forests will be massively logged to clear land for biofuel production. (Often, forests will be logged en masse simply to burn for fuel.) Heavy machinery will be too expensive for most plantations, so their labor will come from slavery and serfdom under authoritarian governments and corporate feudalism. (Slavery is currently used in Brazil to log forests and produce charcoal by hand for the steel industry, after all.)4 The global effects of biofuel production will be increases in the cost of food, increases in water and irrigation drawdown for agriculture, and worsening soil erosion. Regardless, its production will amount to only a small fraction of the liquid hydrocarbons available at the peak of civilization.

All of this will have immediate ecological consequences. The oceans, wracked by increased fishing (to compensate for food shortages) and warming-induced acidity and coral die-offs, will be mostly dead. The expansion of biofuels will destroy many remaining wild areas and global biodiversity will plummet. Tropical forests like the Amazon produce the moist climate they require through their own vast transpiration, but expanded logging and agriculture will cut transpiration and tip the balance toward permanent drought. Even where the forest is not actually cut, the drying local climate will be enough to kill it. The Amazon will turn into a desert, and other tropical forests will follow suit.

Projections vary, but it’s almost certain that if the majority of the remaining fossil fuels are extracted and burned, global warming would become self-perpetuating and catastrophic. However, the worst effects will not be felt until decades into the future, once most fossil fuels have already been exhausted. By then, there will be very little energy or industrial capacity left for humans to try to compensate for the effects of global warming.

Furthermore, as intense climate change takes over, ecological remediation through perennial polycultures and forest replanting will become impossible. The heat and drought will turn forests into net carbon emitters, as northern forests die from heat, pests, and disease, and then burn in continent-wide fires that will make early twenty-first century conflagrations look minor.5 Even intact pastures won’t survive the temperature extremes as carbon is literally baked out of remaining agricultural soils.

Resource wars between nuclear states will break out. War between the US and Russia is less likely than it was in the Cold War, but ascending superpowers like China will want their piece of the global resource pie. Nuclear powers such as India and Pakistan will be densely populated and ecologically precarious; climate change will dry up major rivers previously fed by melting glaciers, and hundreds of millions of people in South Asia will live bare meters above sea level. With few resources to equip and field a mechanized army or air force, nuclear strikes will seem an increasingly effective action for desperate states.

If resource wars escalate to nuclear wars, the effects will be severe, even in the case of a “minor” nuclear war between countries like India and Pakistan. Even if each country uses only fifty Hiroshima-sized bombs as air bursts above urban centers, a nuclear winter will result.6Although lethal levels of fallout last only a matter of weeks, the ecological effects will be far more severe. The five megatons of smoke produced will darken the sky around the world. Stratospheric heating will destroy most of what remains of the ozone layer.7 In contrast to the overall warming trend, a “little ice age” will begin immediately and last for several years. During that period, temperatures in major agricultural regions will routinely drop below freezing in summer. Massive and immediate starvation will occur around the world.

That’s in the case of a small war. The explosive power of one hundred Hiroshima-sized bombs accounts for only 0.03 percent of the global arsenal. If a larger number of more powerful bombs are used—or if cobalt bombs are used to produce long-term irradiation and wipe out surface life—the effects will be even worse.8 There will be few human survivors. The nuclear winter effect will be temporary, but the bombing and subsequent fires will put large amounts of carbon into the atmosphere, kill plants, and impair photosynthesis. As a result, after the ash settles, global warming will be even more rapid and worse than before.

Nuclear war or not, the long-term prospects are dim. Global warming will continue to worsen long after fossil fuels are exhausted. For the planet, the time to ecological recovery is measured in tens of millions of years, if ever.9 As James Lovelock has pointed out, a major warming event could push the planet into a different equilibrium, one much warmer than the current one.10 It’s possible that large plants and animals might only be able to survive near the poles.11 It’s also possible that the entire planet could become essentially uninhabitable to large plants and animals, with a climate more like Venus than Earth.

All that is required for this to occur is for current trends to continue without substantive and effective resistance. All that is required for evil to succeed is for good people to do nothing. But this future is not inevitable.

Image: public domain

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Aug 10, 2018 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction

by Wanted9867 / Reddit

I have lived on 300 acres in west central Florida near the coast for 29 years. I could write a book about what I have seen growing up, but now…now I don’t want to talk about what is left there. Perhaps though, I should.

Little…nothing. The land was a sawmill between 1903-1915 but before and since it was untouched. Signs of the old sawmill are still there, the stills to boil out turpentine are still standing. The woods are quiet now. There are no squirrels left in the trees. The undergrowth is perpetually dry when it’s not raining every day. There is no in-between. The giant Pileated woodpeckers that used to float beneath the canopy between the trees are long gone. The monkey sized fox squirrels disappeared around 2000. I recall seeing the last one in January of 2001, his big bushy tail flowing behind him as he ran up a tall pine tree. I didn’t at the time know of the change that this indicated. The fireflies that would fill the yard beneath the oak trees by the tens of thousands during those steamy late summer evenings are gone now. I haven’t seen one of the fly looking variety since 1997. My dad used to tell me stories that as a kid he’d pull those glowing tails off and stick them on the headlights of his model cars. And how I’d roll my eyes and complain how I’d heard that story before…Jesus, Dad I miss those days now. I found one single firefly this summer- but a different variety…some type of beetle and the first in near two decades. I frantically scrambled to catch him and hold him carefully in my hand. “Where are the rest of you?” I cried.

The tortoise holes are still there- abandoned. The rattlesnake dens beneath the palmettos are empty. The vile bugs I feared so much I now miss. The palmetto bugs, the spiders, the beetles, the variety…where did all the moths go? How heartbreaking it is to remember falling asleep hearing that old purple bug zapper light buzzing downstairs on the porch. In the mornings I’d pick through the hundreds of dead moths. Now there is nothing. At night…now only mosquitoes. 20 years ago the night sky would be filled with bats eating the moths and other flying insects. We had a single apparently sick and very very small bat nest in the back shed back in the winter of 2008. He was so small. He hung there for weeks before finally leaving as well. He never came back. None have returned since.

In the woods there were once deer, boar, turkey, foxes, bobcats and all manner of Florida wildlife. They have all gone now. In the sandy patches I would walk to as a child to look at the hundreds of animals tracks there are now none. No animals cross these areas any longer aside from the occasional raccoon or opossum. The variety is gone, there seems to be nothing left. The trees are still there…for now. The woods are still alive, but their heartbeat is faint. The animals within are now gone. Its soul.

It is sterile and frightening. Echoing like an empty gym.

This property was the last bastion for miles around. Untouched for a hundred years. Then, siege was laid upon it. Roads border this chunk of land on three sides. Across these roads used to be vast stretches of similarly untouched land where I assume these vanished animals would roam to. The streets used to be silent at night, traffic during the days was always minimal. Currently these roads are being widened and traffic is dense. There is nowhere left for the animals to roam to, and they died as a result.

Now these adjacent stretches of land were wiped clean. In 2006 they began developing thousands of acres into subdivisions. Scouring the earth clean and wiping out any trace of anything that came before. Thousands of acres wiped clean, fire hydrants and sewers dug in, roads lain, street signs erected…but then something funny. The bubble burst. The paper chase, the thoughtless, senseless, sickening race that resulted in this utter rape ended. The contractors put up their tools and went home. It was over, completed. Now everything was quiet.

This was an extremely rural area. Land was readily available but nobody had any real reason to come here. 2008 came and these enormous empty plots of planned land sat empty save for 3 or 4 model homes. It is like some sort of Orwellian dystopia. Three homes spaced out across a 200 acre planned and laid out subdivision. I can think of at least five major subdivisions within 5 miles of the house that fit this description. It makes me feel sick. Such destruction, such immense waste. Sometimes I want to scream and beat my fists on the ground. Gas stations and hotels and strip malls and retail centers all erupted from the earth long after the housing bubble burst. The corporate boom would continue its rape of my home town for some time yet. Now they too are empty. FOR RENT signs in the windows of the empty strip malls. Gas stations boarded up. The Taco Bell that closed and has traded hands 10 times between various failed franchises…the waste of it all crushes my soul.

I no longer feel comfortable going into the woods I grew up in. It is too empty and it feels different. It always feels as if something is watching me. I feel it may be the trees gazing upon me knowing the destruction, the hideous things we have done to them. I feel guilt.

It is only 2018. What have we done? How were we all so blind? The Matrix struck far closer to home than I think we all gave it credit for.

The way it was was the best it was ever gonna get. I realize that now looking back on my childhood.

We do not have much time left, I hope. I am rather confident of it.

Editor’s note: this originally appeared as commentary titled “Trust your senses. We are all front-line observers to species/habitat destruction in our own backyards” on the Reddit community r/collapse, and has been republished with permission of the author.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Aug 5, 2018 | The Problem: Civilization

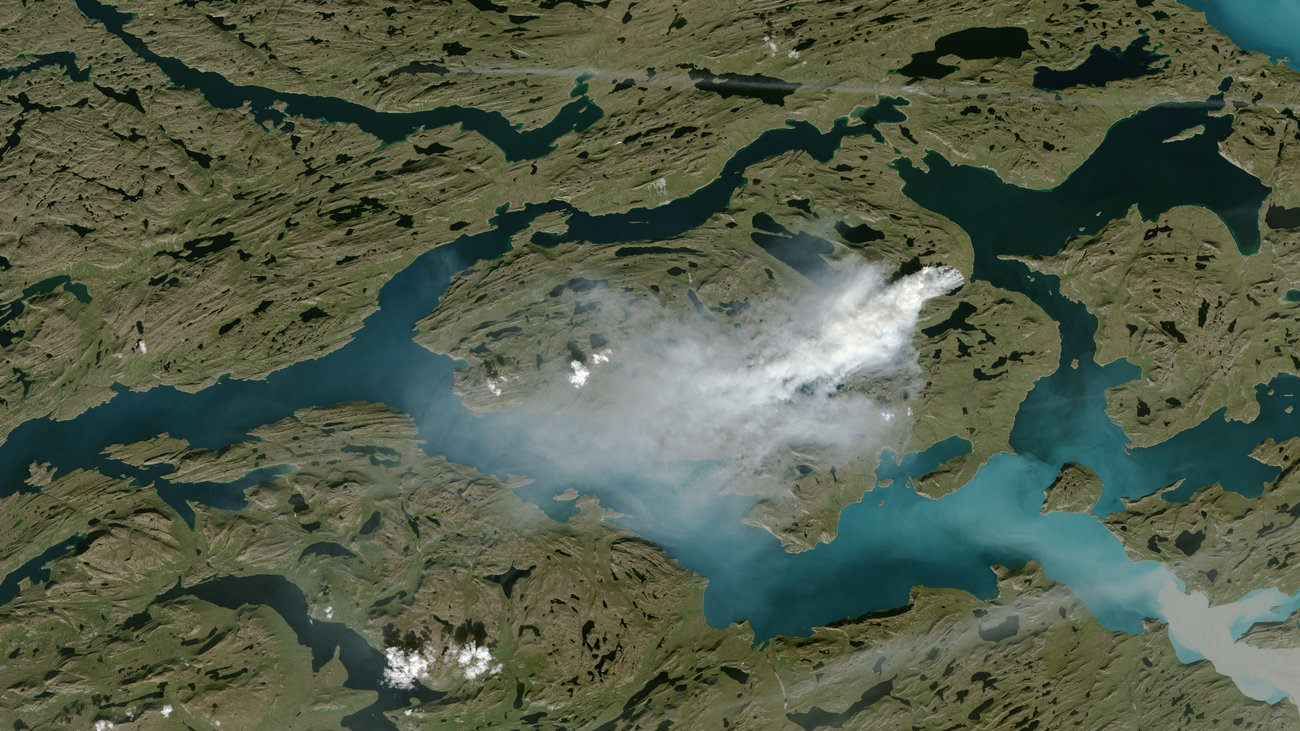

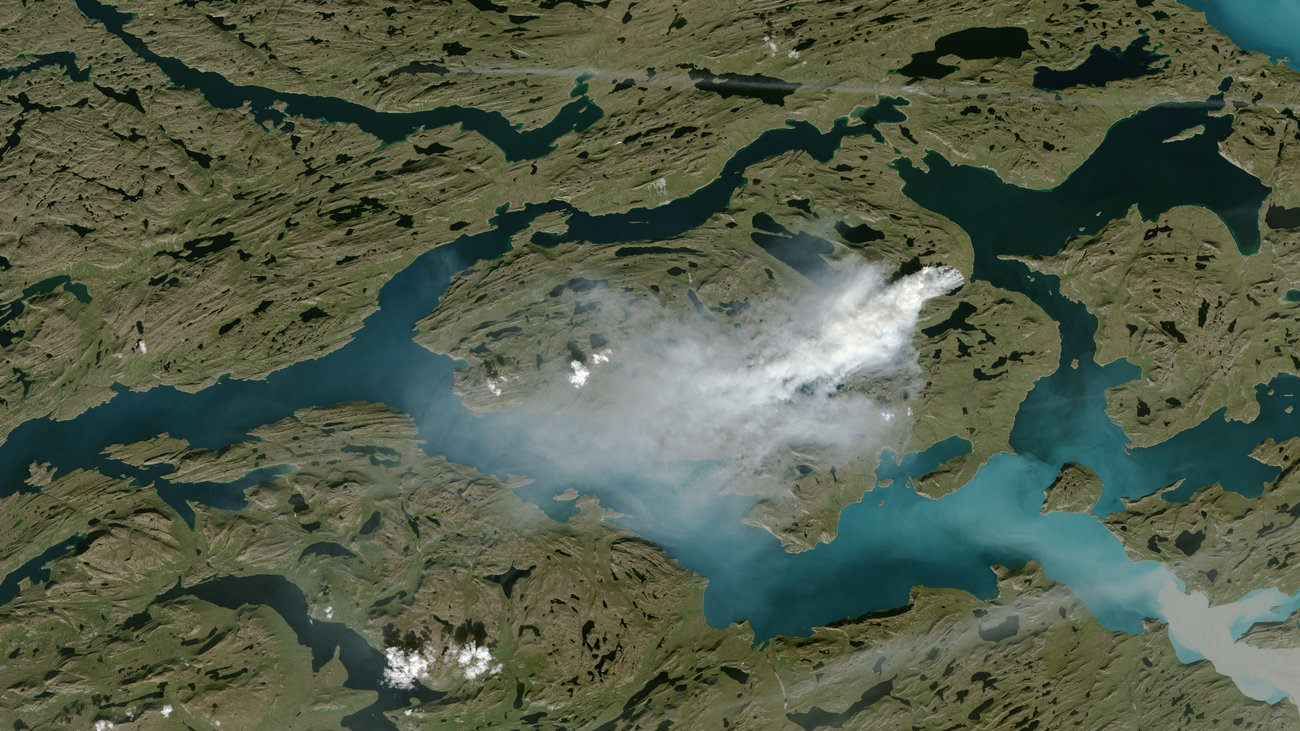

Featured image: satellite photograph of wildfire raging in Greenland, as seen from space. NASA Earth Observatory

by Pray for Calamity

It is easy to get lost. The digital world exists parallel to the real, and just by flicking a finger across a piece of glass, one can open a doorway to all of the happenings any other human has written of, or photographed, or filmed. My morning ritual includes making a cup of tea, hopefully before my daughter has woken, and through the steam that rises from my cup I read what news of the wider world has come through my various feeds.

Fires rage in the Arctic, and in Greece, and in the American West. Heat has gripped the globe from Japan to Algeria to Portugal. There are floods, and parched farm fields, desperate refugees, and the most grotesque horror show of state sponsored famine and homicide in Yemen.

Pounding footsteps move across the floor from my daughter’s bedroom through the kitchen. I exit the digital. My daughter lumbers to me with tired eyes and I know she wants to be picked up, and to be held.

“Oh, my girl. My wonderful girl.”

She doesn’t say anything, her head on my shoulder, facing away so that I can smell her long hair. My exhale is deep and satisfied. She is right where I want to be. An hour later as we walk our stone driveway to go feed our chickens and ducks, I watch her small legs plodding along in pink plastic rain boots. The air is cool, actually, and I realize that this is my real, and that all of those terrible things I read about in the quiet dawn are far away, if they exist at all.

—

I have a fascination with orienteering. A while back a friend gave me his compass, which his father had given to him. I already had a compass, a cheap one that stayed packed in my camping bag. This new one my friend gave to me is much nicer. It has a weight to it that makes it feel significant and truthful, like the weight of a proper kitchen knife or an old, leather bound dictionary.

Upon receiving this gift from my friend, I realized I only ever used a compass to figure out which direction was which, but that I really had no idea how to properly use a compass in accordance with a map. So I began to read instructions on how to do so online, and even watched some videos on orienteering.

The word “orient” is saddled with an enormous historical and social burden. It is a derivation of the latin word for “east,” (the opposite being “occident,” a derivation of “west”) and is typically used to refer to the continent of Asia. Of course, what is “east” (or west, for that matter) really depends on where you are standing, so to conceive of the orient as Asia is to be speaking from a European perspective geographically, or at least as one influenced by European perspective. This is all rather contemporary though, as in Ancient Rome, anything south of the city of Rome was the Orient, as they had drawn in their minds an east-west line running through that city, and made determinations based on whether one lived above or below it. We seem to often set ourselves as a fixed point, the pivot of the spinning needle that whirls around us.

A map is wonderful, as it is a representation of terrain. But if you don’t know where you are, a map can be worse than useless. A compass is very useful, as it can point you in a cardinal direction. But without a map, the name of any given direction becomes trivia.

To “orient” seems to literally mean to find east, the direction we know we can reliably look to find the rising sun. When lost, one must orient themselves or remain so. One must align the compass with the map before shooting a bearing and heading out into the wilderness.

—

In my moments of greater clarity, I want to absolve myself of all political inclination. If I ask myself, point blank, “what is it I am most concerned about?” the answer comes quite quickly: Ecology, the living world. My great worry regarding the world at large centers on the fact that human industrial civilization is every day bringing the web of life closer to the brink of total collapse. Through climate change, extinctions, pollution, the promulgation of invasive species, and the conversion of wild spaces into regions managed and exploited for extraction and production, human civilization is destroying everything upon which it stands. With such an insurmountable threat bearing down, it seems silly to get drawn into conflicts over petty human arguments. Of course, most of what is trumpeted by the TV and print news seems to be just this, at least in comparison to the storm looming over us.

But it happens. I get pulled into the gyre. Despite my desire to stay focused on the material world beneath my feet, the political nature of industrial collapse maintains itself as undeniably evident. As the conditions under which people exist continue to get worse, conflicts expand, and those in power exploit these circumstances for their own gain. Thus it is that ideologues create out groups of others – immigrants, Muslims, black folk, the poor – who they soak with blame for the downward trend lines that define our age. So it is that we have endless wars at home and abroad, with piles of dead victims of drone assassination and cages full of terrified children.

Like it or not, collapse is political. Will the downward slope of Hubbert’s peak be pocked with debt prisons or bread lines? Will the despair of climate chaos be met with concentration camps or communes? Will we slouch towards Olduvai while erecting walls or by tearing them down? Even if we believe all our best efforts will fail us, even if we believe that the wounds we have inflicted on the world are too deep to heal, and that a great suffering is certain, wouldn’t at the end of it all we prefer to fail at decency than to succeed at evil?

Of course, determining the difference can be quite tricky. All men mean well, it is said. Good and evil are meaningless terms, like north and south. If you know nothing of the terrain, if you have no map, you’re likely to just walk downhill because it’s easier.

—

“The core question that brings liberalism, conservatism, nationalism and identity politics into conflict with each other is a fundamental one: who has the authority to describe society? Whose version of history will be heard?”

This is an excerpt from a recent editorial in The Guardian by William Davies entitled, “The Free Speech Panic: How the Right Concocted a Crisis.” I was struck by the clarity of this concept. So much of the current argument, or rather, the tangled mess of arguments surrounding politics, individual identity, national identity, and so forth stems from this very conundrum. Who gets to draw the map? By whose standards do we orient ourselves?

Daily the world is changing in ways that were not foretold by those who have been tasked with explaining reality. By neglecting to confront the crisis of net energy decline, by declining to confront the crisis of debt based money on a finite planet, by declining to confront the crisis of ecological overshoot, the social caste of media makers and politicians have left people scraping to understand the knock on effects that have rippled through society because of these very crises.

People are finding themselves lost in a wilderness of information that runs contrary to the official “everything is fine” narrative put forth by the state and capital. In this rugged and dark place, people are seeking to orient themselves so that they can understand just what is required of them in order to survive and to provide a future for themselves and their families. Whether it is a young college student wondering if it makes sense to take on a debt load in order to attain an education, or a middle age worker wondering why the hell it is so damn hard to pay for a home, and food, and healthcare for their family, people eventually recognize that the explanations for the world around them that they are being fed by those in power do not match the geography of their day to day existence.

When the political narrative one has been given fails, all a person can do is look around and scan the horizon for recognizable features, looking for enough of the familiar so they can finally mark an X and at least understand where exactly they stand.

To orient oneself in a social space can be difficult, and one ultimately does so by recognizing who they are not. Other people become boundary markers, warnings of what not to do, how not to be. Group identities form, people join teams, they carry flags, we don’t necessarily know who we are, but we damn well know we aren’t them.

You’re with us or you’re against us. Better dead than red. Bash the fash! West is best. Resist! Traitor!

Who gets to draw the map? As climate change progresses and the wealth gap grows wider and the pain and struggle of every day life grows more intolerable for the average person, this question will be the hill we die on.

—

My wife plunges a knife into a dark green watermelon. It is near perfectly round and about the size of a bowling ball. The second one we pulled from our garden this summer, it is at a perfect stage of ripeness. Standing in the kitchen the three of us spit small black seeds into a glass bowl as we enjoy the sweetness of the fruit.

The rinds get dumped in the chicken paddock, and I lock the door to the coop. The sun has set behind me as I walk silently back towards the house. Even when we tell people how to get here, our little plot of land can be very hard to find.

Originally published on Pray for Calamity. Republished with permission.