by DGR News Service | Sep 29, 2020 | Culture of Resistance, Movement Building & Support, The Solution: Resistance

Excerpted from the book Deep Green Resistance — Chapter 15: Our Best Hope by Lierre Keith.

Featured image: Felix Mittermeier via Unsplash

3. Deep Green Resistance must be multilevel.

There is work to be done—desperately important work—aboveground and underground, in the legal sphere and the economic realm, locally and internationally. We must not be divided by a diversionary split between radicalism and reformism. One more time: the most militant strategy is not always the most radical or the most effective. The divide between militance and nonviolence does not have to destroy the possibility of joint action. People of conscience can disagree. They can also respectfully choose to work in different arenas requiring different tactics. I can think of no scenario in which a program to provide school cafeterias with food straight from local, grass-based farms would be advanced by explosives. In contrast, a project to save the salmon would do well to consider such an option.

Every movement for justice struggles with the subject. Violence, including property destruction, should not be undertaken without serious reflection and ethical, even spiritual, investigation. Better to accept that as individuals we will arrive at different answers—but that we have to build a successful movement despite those differences.

That shouldn’t be hard, considering that this entire culture has to be replaced. We need every level of action and every passion brought to bear. The Spanish Anarchists stand as a great example of a broad and deep effort to transform an entire society. Writes Murray Bookchin, “The great majority of these [affinity] groups were not engaged in terrorist actions. Their activities were limited mainly to general propaganda and to the painstaking but indispensable job of winning over individual converts.” The café was where all that discussion and proselytizing happened, just as it happened in pubs for the Irish and the IRA. The anarchists in Barcelona took over railroads, factories, public utilities, retail and wholesale businesses, and ran them by workers’ committees. They also created their own police force to patrol their neighborhoods, and revolutionary tribunals to mete out justice. Before the Fascist victory, the anarchists in Andalusia created communal land tenure arrangements, stopped using money for internal exchange of goods, and established directly democratic popular assemblies for their governance. They also started over fifty alternative schools across the country. Their educational ideas spread through Europe, landing in England where they were taken up by A. S. Neill at his famous Summerhill. From there, the concept of free schools migrated to the US. If you are involved with any student-directed, alternative education, you are a direct descendent of the Spanish Anarchists.

Every institution across this culture must be reworked or replaced by people whose loyalty to the planet and to justice is absolute. A DGR movement understands the necessity of both aboveground and underground work, of confronting unjust institutions as well as building alternative institutions, of every effort to transform the economic, political, and social spheres of this culture. Whatever you are called to do, it needs to be done.

It is unlikely that a political candidate on the national or even state level will have a chance of winning on a platform of truth telling, at least not in the United States. The industrial world needs to reduce its energy consumption to that of Brazil or Sri Lanka. That this reduction is inevitable doesn’t make it any more palatable to the average American, who will likely only give up his entitlement when it’s pried from his cold, dead fingers. At the local level, the political process may be more amenable to radical truth telling, especially in progressive enclaves. For those with the skills and interest, running for local office could yield results worth the effort. It could also scale up to other communities. What kinds of institutional change could be affected at the local level is a question worth asking.

From outside, a vast amount of pressure is needed to stop fossil fuel and other industrial extractions. Legislative initiatives, boycotts, direct action, and civil disobedience must be priorities. We need to form groups like Climate Camp, which started in 2006 with a teach-in and protest at a coal-fired plant in West Yorkshire, England. They’ve blockaded the European Carbon Exchange in London, protested runway expansion at Heathrow Airport, and are taking action against BP for its participation in the tar sands. In their own words,

The climate crisis cannot be solved by relying on governments and big businesses with their “techno-fixes” and other market-driven approaches.… We must therefore take responsibility for averting climate change, taking individual and collective action against its root causes and to develop our own truly sustainable and socially just solutions. We must act together and in solidarity with all affected communities—workers, farmers, indigenous peoples and many others—in Britain and throughout the world.

If the referendums and court decisions and market solutions fail, if the civil disobedience and blockades aren’t enough, a Deep Green Resistance is willing to take the next step to stop the perpetrators.

In the UK, someone is feeling the urgency. On April 12, 2010, the machinery at Mainshill coal site was sabotaged, machinery that was Mordorian in its destructive power: “a 170 tonne face scrapping earth mover.” The coal was slated for the Drax Power Station, “recognised as the most polluting in the UK.”

According to their communiqué:

Sabotage against the coal industry will continue until its expansion is halted.

This is a simple vow, an “I do” to every living creature. Deep Green Resistance remembers that love is a verb, a verb that must call us to action.

by DGR News Service | Sep 24, 2020 | The Problem: Civilization

Excerpted from the book Deep Green Resistance — Chapter 15: Our Best Hope by Lierre Keith.

Fairy Tales are more than true; not because they tell us that dragons exist, but because they tell us that dragons can be beaten.

—G. K. Chesterton

The IRA had Sinn Fein. The abolition movement had the Underground Railroad, Nat Turner and John Brown, and Bloody Kansas. The suffragists had organizations that lobbied and educated, and then the militant WSPU that burned down train stations and blew up golf courses. The original American patriots had printers and farmers and weavers of homespun domestic cloth, and also Sons of Liberty who were willing to bodily shut down the court system. The civil rights movement had the redefinition of blackness in the Harlem Renaissance and the stability, dignity, and community spirit of the Pullman porters, and then four college students willing to sit down at a lunch counter and face the angry mob. The examples are everywhere across history. A radical movement grows from a culture of resistance, like a seed from soil. And just like soils must have the cradling roots and protective cover of plants, without the actual resistance, no community will win justice or human rights against an oppressive system.

Our best hope will never lie in individual survivalism. Nor does it lie in small groups doing their best to prepare for the worst. Our best and only hope is a resistance movement that is willing to face the scale of the horrors, gather our forces, and fight like hell for all we hold dear. These, then, are the principles of a Deep Green Resistance movement.

1. Deep Green Resistance recognizes that this culture is insane.

A DGR movement understands that power is sociopathic and hence there will not be a voluntary transformation to a sustainable way of life. Providing “examples” of sustainability may be helpful for specific projects geared toward people who are anxious about their survival, but they are not a broad solution to a culture addicted to power and domination. Since this culture went viral out of the Tigris-Euphrates River Valley, it has encountered untold numbers of sustainable societies, some of them profoundly peaceful and egalitarian, and its response has been to wipe them out with a sadism that is incomprehensible. As one example among millions, Christopher Columbus’s officers preferred their rape victims between the ages of ten and twelve.

The pattern repeats itself across time and culture wherever civilization has risen. Civilization requires empire, colonies to dominate and gut. Domination requires a steady supply of hierarchy, objectification, and violence. As Ellen Gabriel, one of the participants in the Oka uprising, said, “We were fighting something without a spirit.… [t]hey were like robots.” The result is torture, rape, and genocide. And the deep heart of this hell is the authoritarian personality structured around masculinity with its entitlement and violation imperative.

Lundy Bancroft, writing about the mentality of abusive men, writes, “The roots [of abuse] are ownership, the trunk is entitlement, and the branches are control.” You could not find a clearer description of civilization’s 10,000 year reign of terror.

by DGR News Service | Jul 2, 2020 | The Solution: Resistance

Chapter 8: Organizational Structure

An excerpt from the book Deep Green Resistance: Strategy to Save the Planet.

There is one thing you have got to learn about our movement. Three people are better than no people.

—Fannie Lou Hamer, civil rights leader

Resistance organizations can be divided into aboveground (AG) and underground (UG) groups. These groups have strongly divergent organizational and operational needs, even when they have the same goals. Broadly speaking, aboveground groups do not carry out risky illegal actions, and are organized in ways that maximize their ability to use public institutions and communication structures. Underground groups exist primarily to carry out illegal or repressed activities and are organized in ways that maximize their own security and effectiveness.

Some aboveground groups do carry out illegal activities as part of a campaign of civil disobedience, or they break or bend lesser laws as a means of causing disruption or confronting power (for example, through “illegal” protests). These groups often occupy something of an awkward middle ground, a subject we’ll return to. As police become more draconian and punishments more severe, such groups may split into underground and aboveground factions, with some members refraining from illegal acts out of fear of punishment, while others seek to escalate their actions.

There has to be a partition, a firewall, between aboveground and underground activities. Some historical aboveground groups have tried to sit on the fence and carry out illegal activities without full separation. Such groups worked in places or times with far less pervasive surveillance than any modern society. Their attempts to combine aboveground and underground characteristics sometimes resulted in their destruction, and severe consequences for their members.

In order to be as safe and effective as possible, every person in a resistance movement must decide for her- or himself whether to be aboveground or underground. It is essential that this decision be made; to attempt to straddle the line is unsafe for everyone.

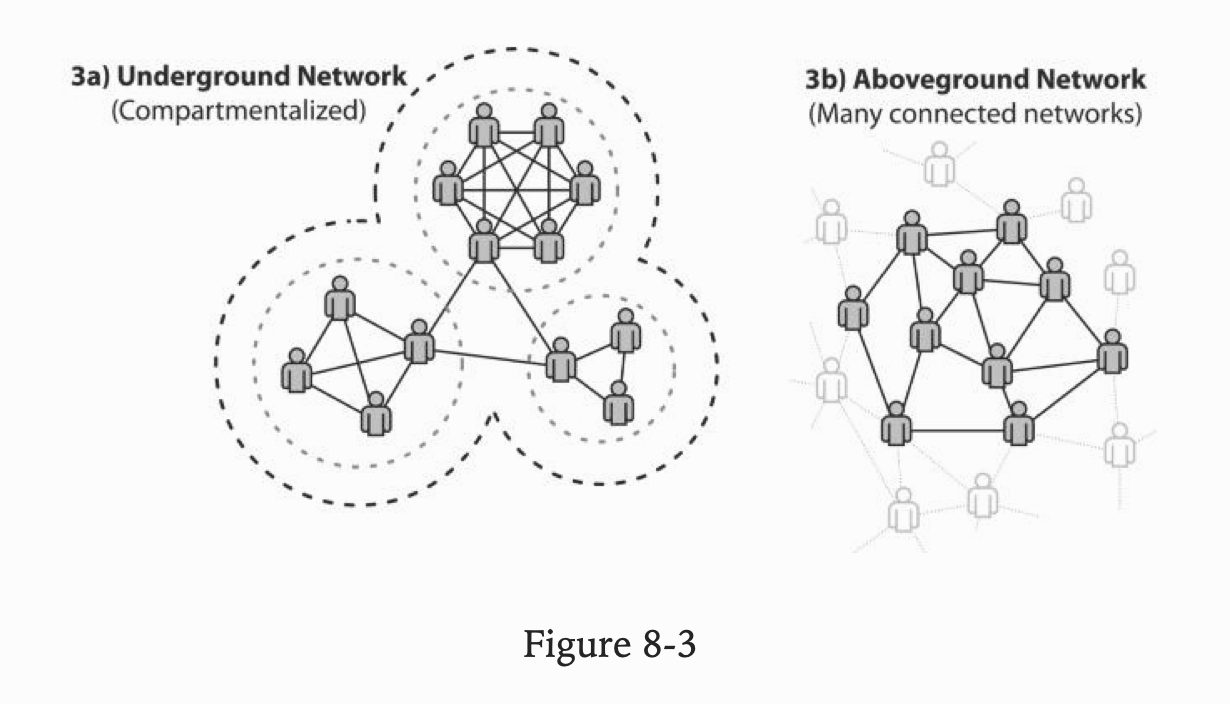

The differences between aboveground and underground organizing are expressed in every facet of a group’s structure and practice. Some of these differences are summarized in the table to the left.

Regardless of whether they are aboveground or underground, any group which carries out effective resistance activity will be considered a threat by those in power, and those in power will try to disrupt or destroy it.

Basic Organizational Structures

Within both aboveground and underground activism there are several templates for basic organizational structures. These structures have been used by every resistance group in history, although not all groups have chosen the approach best suited for their situations and objectives. It is important to understand the pros, cons, and capabilities of the spectrum of different organizations that comprise effective resistance movements.

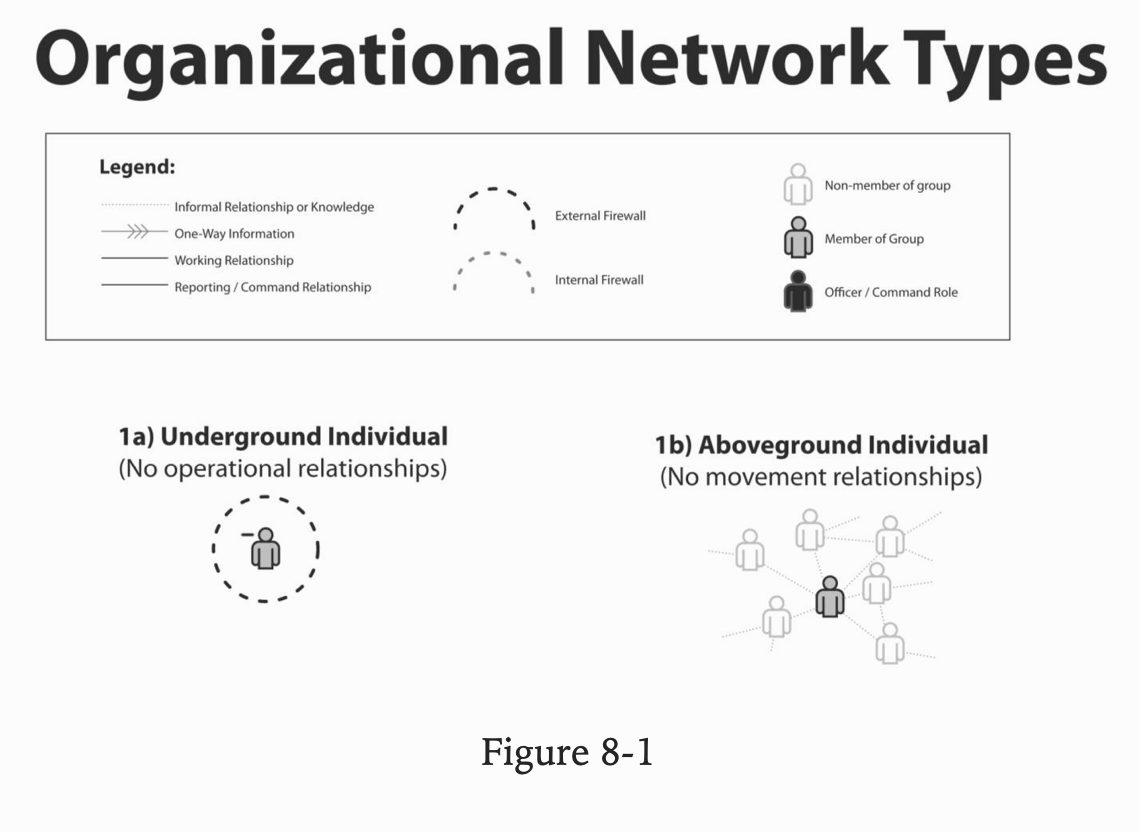

The simplest “unit” of resistance is the individual. Individuals are highly limited in their resistance activities. Aboveground individuals (Figure 8-1b) are usually limited to personal acts like alterations in diet, material consumption, or spirituality, which, as we’ve said, don’t match the scope of our problems. It’s true that individual aboveground activists can affect big changes at times, but they usually work by engaging other people or institutions. Underground individuals (Figure 8-1a) may have to worry about security less, in that they don’t have anyone who can betray their secrets under interrogation; but nor do they have anyone to watch their back. Underground individuals are also limited in their actions, although they can engage in sabotage (and even assassination, as all by himself Georg Elser almost assassinated Hitler).

Individual actions may not qualify as resistance. Julian Jackson wrote on this subject in his important history of the German Occupation of France: “The Resistance was increasingly sustained by hostility of the mass of the population towards the Occupation, but not all acts of individual hostility can be characterized as resistance, although they are the necessary precondition of it. A distinction needs to be drawn between dissidence and resistance.” This distinction is a crucial one for us to make as well. Jackson continues, “Workers who evaded [compulsory labor], or Jews who escaped the round-ups, or peasants who withheld their produce from the Germans, were transgressing the law, and their actions were subversive of authority. But they were not resisters in the same way as those who organized the escape of [forced laborers] and Jews. Contesting or disobeying a law on an individual basis is not the same as challenging the authority that makes those laws.”

Individual actions may not qualify as resistance. Julian Jackson wrote on this subject in his important history of the German Occupation of France: “The Resistance was increasingly sustained by hostility of the mass of the population towards the Occupation, but not all acts of individual hostility can be characterized as resistance, although they are the necessary precondition of it. A distinction needs to be drawn between dissidence and resistance.” This distinction is a crucial one for us to make as well. Jackson continues, “Workers who evaded [compulsory labor], or Jews who escaped the round-ups, or peasants who withheld their produce from the Germans, were transgressing the law, and their actions were subversive of authority. But they were not resisters in the same way as those who organized the escape of [forced laborers] and Jews. Contesting or disobeying a law on an individual basis is not the same as challenging the authority that makes those laws.”

Of course, one’s options for resistance are greatly expanded in a group.

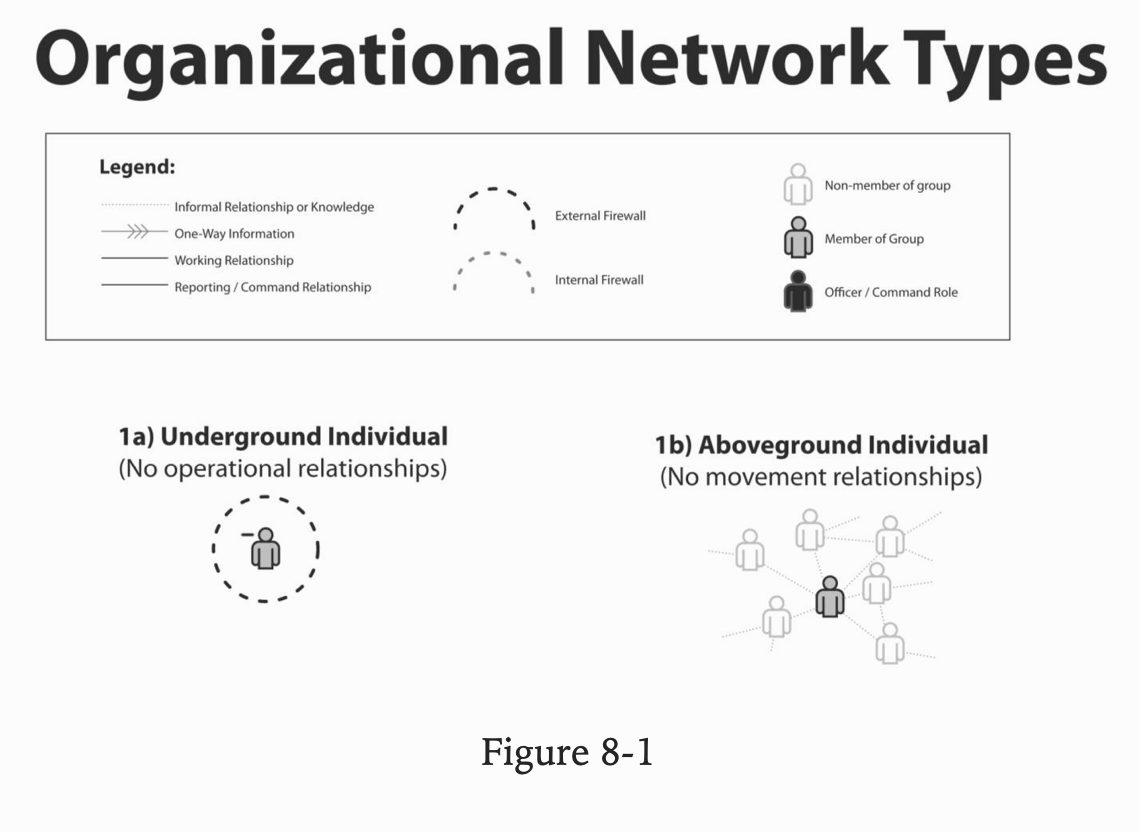

The most basic organizational unit is the affinity group. A group of fewer than a dozen people is a good compromise between groups too large to be socially functional, and too small to carry out important tasks. The activist’s affinity group has a mirror in the underground cell, and in the military squad. Groups this size are small enough for participatory decision making to take place, or in the case of a hierarchal group, for orders to be relayed quickly and easily.

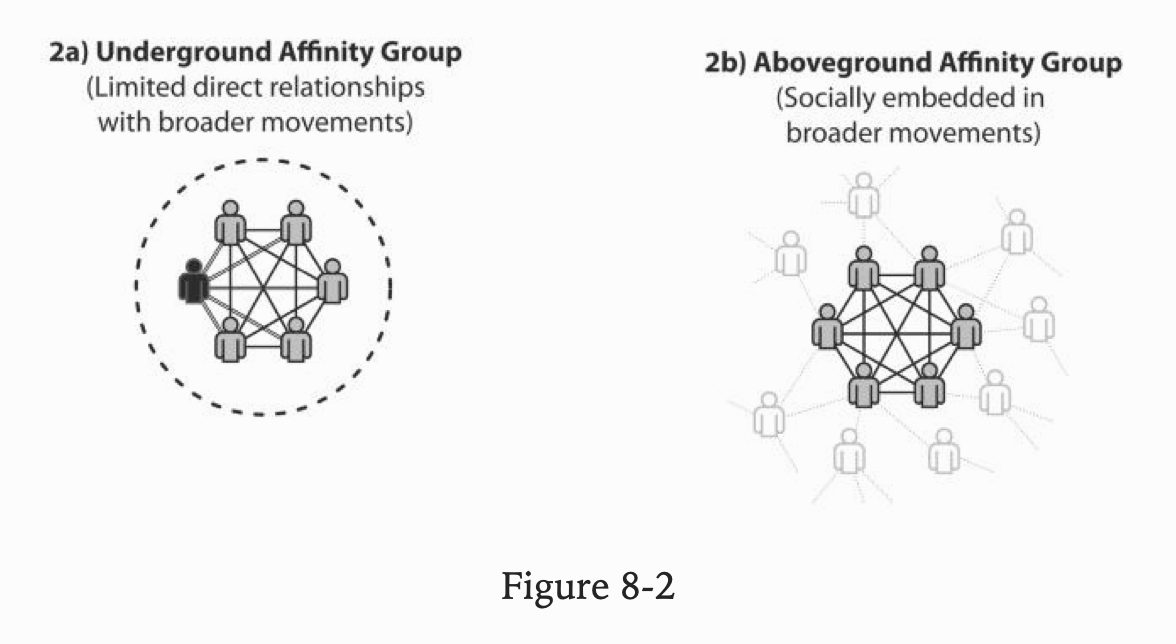

The underground affinity group (Figure 8-2a, shown here with a distinct leader) has many benefits for the members. Members can specialize in different areas of expertise, pool their efforts, work together toward shared goals, and watch each others’ backs. The group can also offer social and emotional support that is much needed for people working underground. Because they do not have direct relationships with other movements or underground groups, they can be relatively secure. However, due to their close working relationships, if one member of the group is compromised, the entire affinity group is likely to be compromised. The more members are in the group, the more risk involved (and the more different relationships to deal with). Also because the affinity group is limited in size, it is limited in terms of the size of objectives it can go after, and their geographic range.

Aboveground affinity groups (Figure 8-2b) share many of the same clear benefits of a small-scale, deliberate community. However, they may rely more on outside relationships, both for friends and fellow activists. Members may also easily belong to more than one affinity group to follow their own interests and passions. This is not the case with underground groups—members must belong only to one affinity group or they are putting all groups at risk.

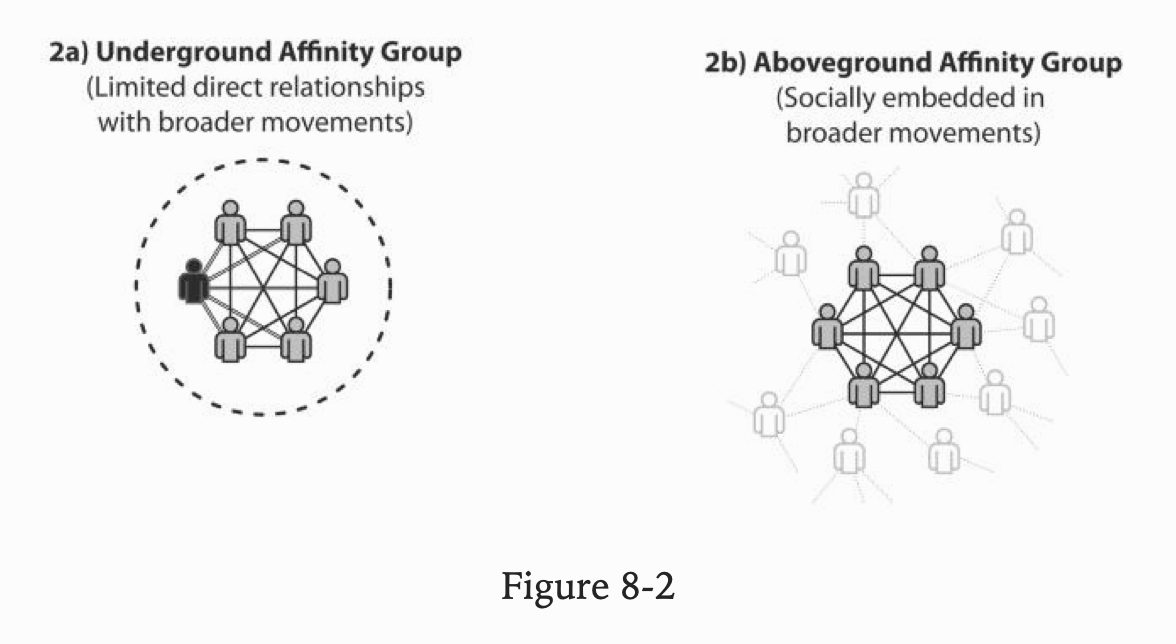

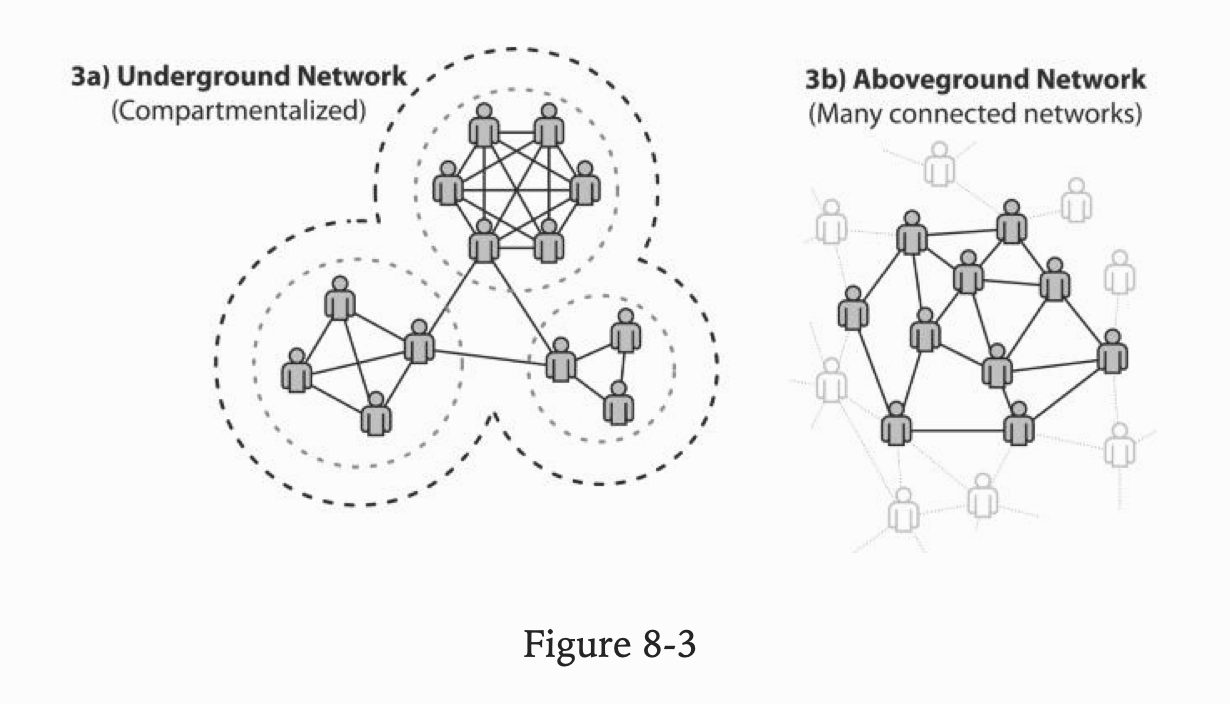

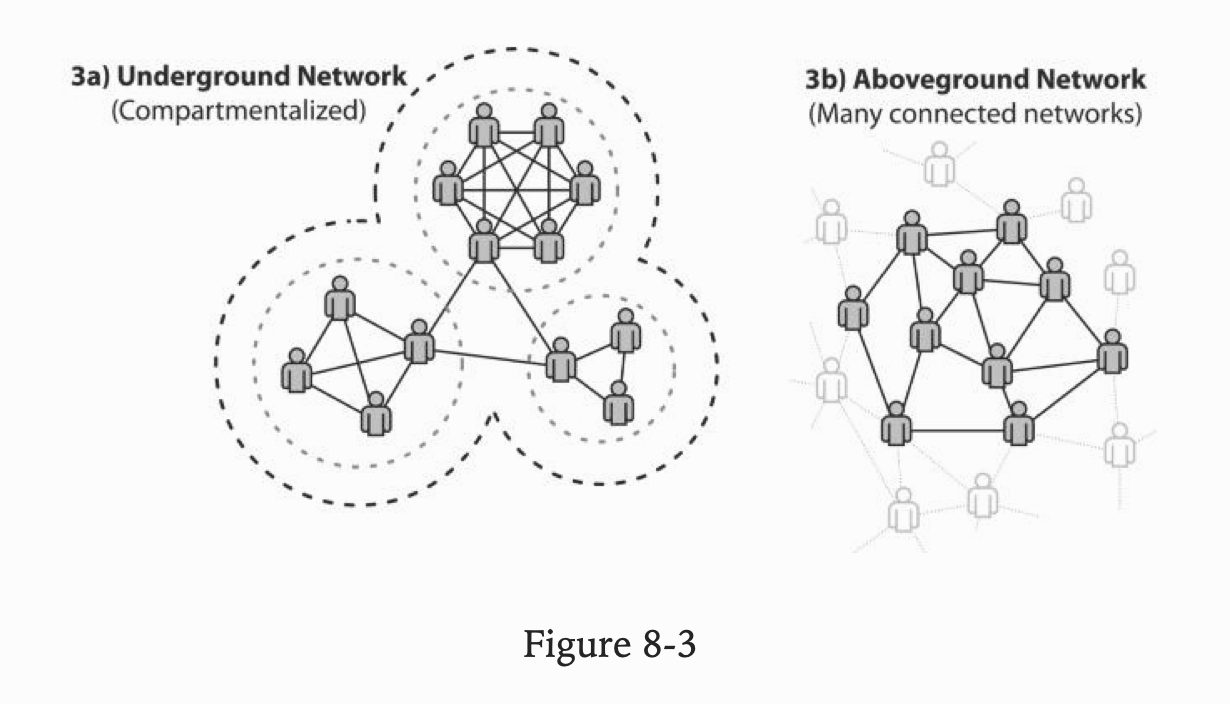

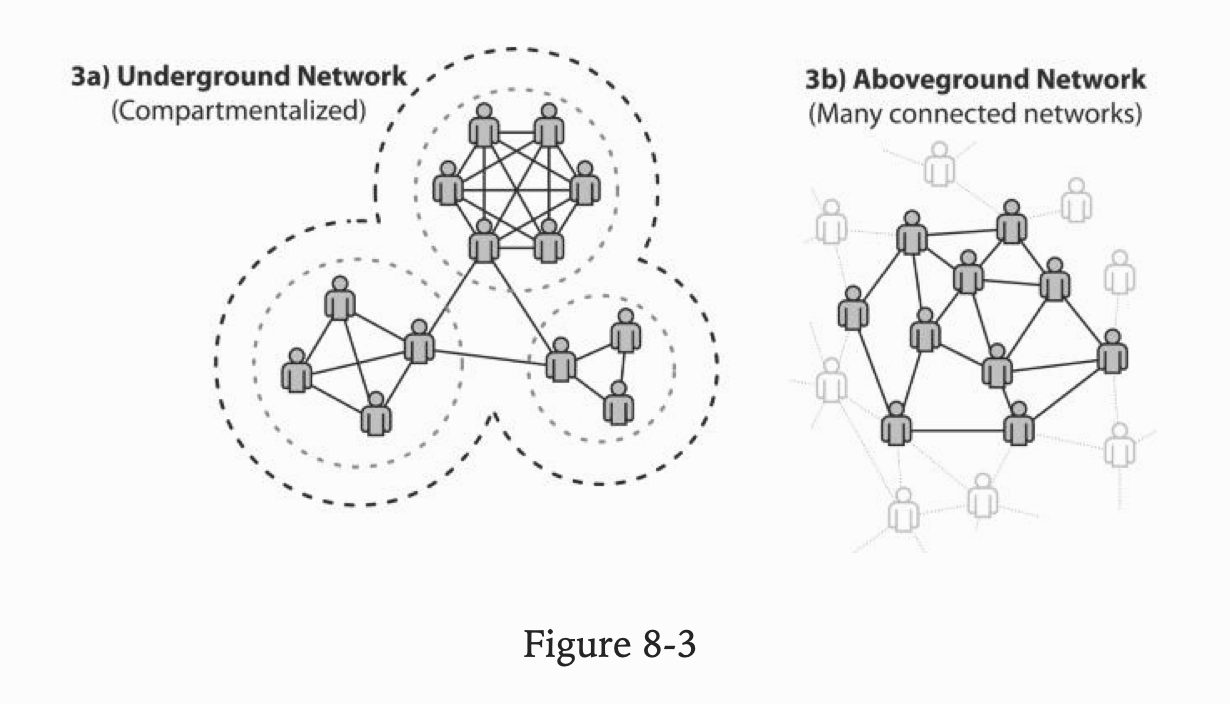

The obvious benefit of multiple overlapping aboveground groups is the formation of larger movements or “mesh” networks (Figure 8-3b). These larger, diverse groups are better able to get a lot done, although sometimes they can have coordination or unity problems if they grow beyond a certain size. In naturally forming social networks, each member of the group is likely to be only a few degrees of separation from any other person. This can be fantastic for sharing information or finding new contacts. However, for a group concerned about security issues, this type of organization is a disaster. If any individual were compromised, that person could easily compromise large numbers of people. Even if some members of the network can’t be compromised, the sheer number of connections between people makes it easy to just bypass the people who can’t be compromised. The kind of decentralized network that makes social networks so robust is a security nightmare.

The obvious benefit of multiple overlapping aboveground groups is the formation of larger movements or “mesh” networks (Figure 8-3b). These larger, diverse groups are better able to get a lot done, although sometimes they can have coordination or unity problems if they grow beyond a certain size. In naturally forming social networks, each member of the group is likely to be only a few degrees of separation from any other person. This can be fantastic for sharing information or finding new contacts. However, for a group concerned about security issues, this type of organization is a disaster. If any individual were compromised, that person could easily compromise large numbers of people. Even if some members of the network can’t be compromised, the sheer number of connections between people makes it easy to just bypass the people who can’t be compromised. The kind of decentralized network that makes social networks so robust is a security nightmare.

Underground groups that want to bring larger numbers of people into the organization must take a different approach. A security-conscious underground network will largely consist of a number of different cells with limited connections to other cells (Figure 8-3a). One person in a cell would know all of the members in that cell, as well as a single member in another cell or two. This allows coordination and shared information between cells. This network is “compartmentalized.” Like all underground groups, it has a firewall between itself and the aboveground. But there are also different, internal firewalls between sections.

Underground groups that want to bring larger numbers of people into the organization must take a different approach. A security-conscious underground network will largely consist of a number of different cells with limited connections to other cells (Figure 8-3a). One person in a cell would know all of the members in that cell, as well as a single member in another cell or two. This allows coordination and shared information between cells. This network is “compartmentalized.” Like all underground groups, it has a firewall between itself and the aboveground. But there are also different, internal firewalls between sections.

Such a network does have downsides. Having only a single link between cells is beneficial, in that if one cell is compromised, it is much more difficult to compromise other cells. However, the connection is also more brittle. If a “liaison” is removed from the network or loses communication for whatever reason, then the network may be broken up. A backup plan for regaining communication can reduce the damage from this, but increase the level of risk. Also, the nonhierarchal nature of this network means that choosing actions can be more difficult. The more cells are involved, the larger the number of people who must have critical information in order to make decisions. That said, these groups can be very effective and functional. The famous Underground Railroad was a decentralized underground network.

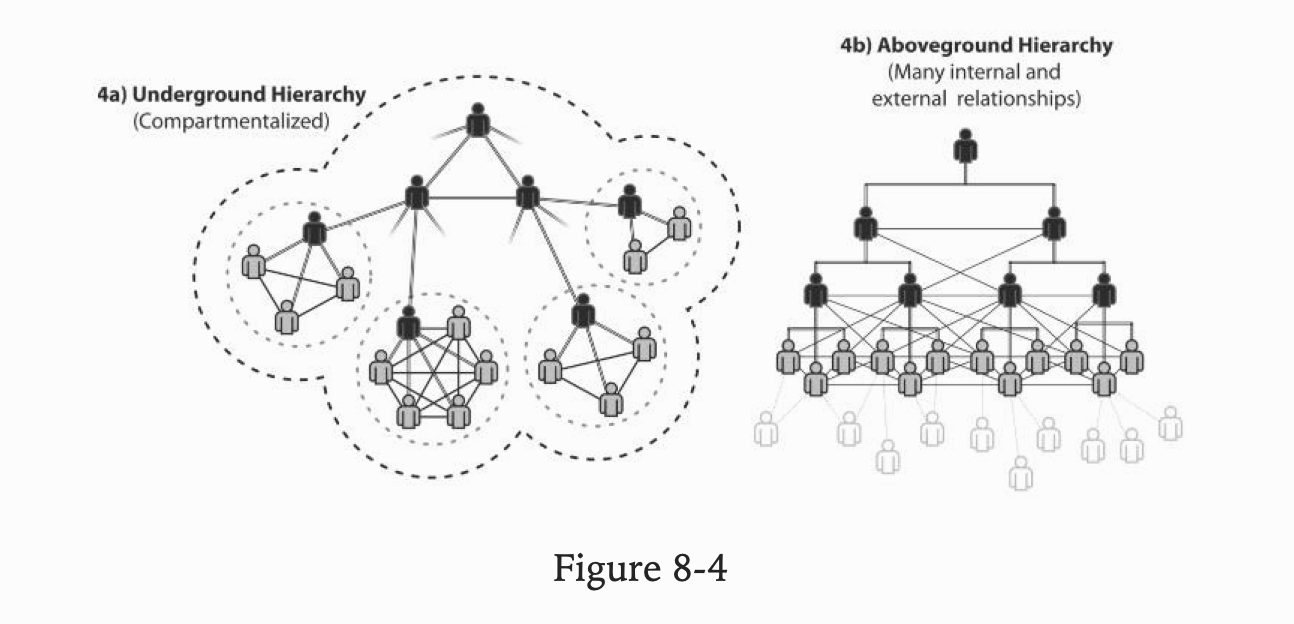

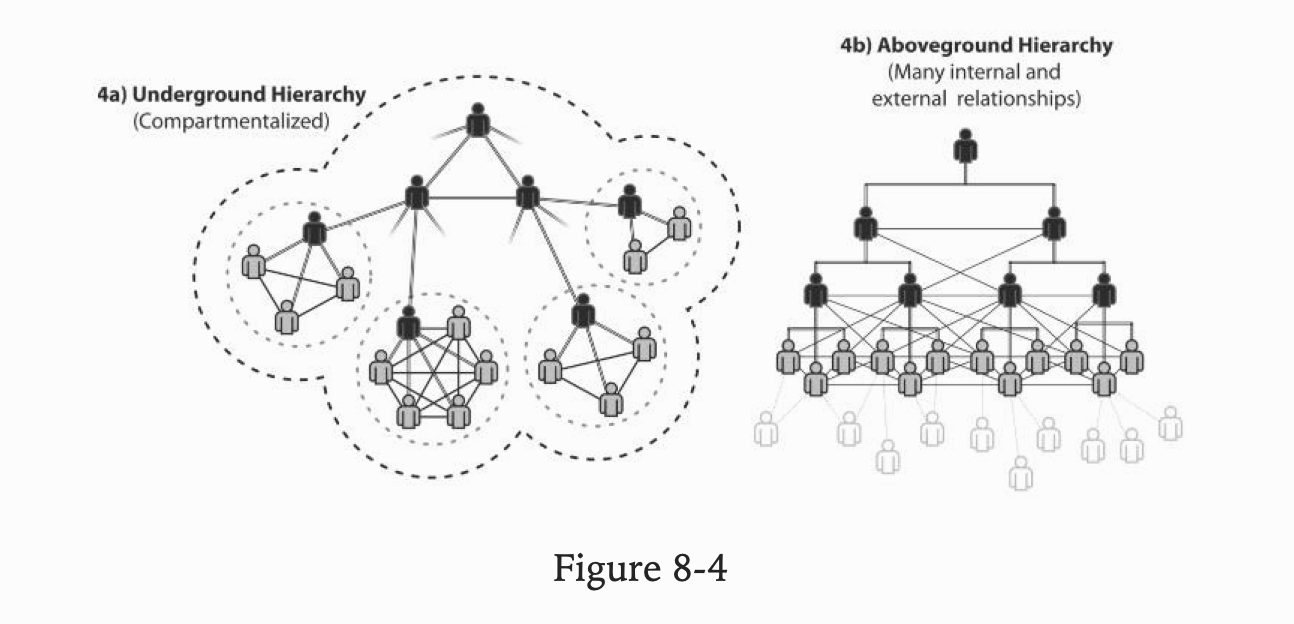

Some of these problems are addressed in both aboveground and underground groups through the use of a hierarchy. In underground hierarchies (Figure 8-4a), large numbers of cells can be connected and coordinated through branching, pyramidal structures. These types of groups have vastly greater potential than smaller networks. Their numbers make for increased risk, yes, but that increased risk can be reduced by the use of specialized counterintelligence cells within the network and wide-ranging coordinated attacks.

Aboveground hierarchies (Figure 8-4b) are quite familiar and common, in part because they are highly effective ways of coordinating large numbers of people to accomplish a specific objective. As shown, aboveground hierarchies facilitate many relationships between people in different parts of the hierarchy. This lack of compartmentalization might be good in terms of productivity, but not in terms of security.

There are very specific situations in which it may be acceptable to send information through an underground group’s firewall. The recruitment process necessarily involves communication with people outside the group. However, these people would not be active in aboveground movements, and, at least initially, they would only know one member of the organization in one cell.  Of course, there are no direct relationships between people in the underground and aboveground groups.

Of course, there are no direct relationships between people in the underground and aboveground groups.

In certain situations, one-way (and likely anonymous) communications may take place across the firewall. Informants who want to give information to the resistance network may pass on information to a member of an internal intelligence group. However, the intelligence group would not share information about identities or the network with those people. Information may also travel one-way in the opposite direction. The underground groups may want to send communiqués or other information to the media or press office. Of course, any communication across the firewall, even those thought anonymous, entails a certain small amount of risk. Therefore, the benefits must outweigh the risks.

All of the examples illustrated are simplified and generalized. Resistance groups in history have had a wide variety of internal structures based on these general templates. They often had to make a deliberate compromise between organizational security (which comes from loosely connected and decentralized cells) and organizational effectiveness (which comes from more densely connected and centralized cells).

by DGR News Service | Jun 27, 2020 | The Solution: Resistance

Today we share an excerpt from the book Deep Green Resistance: Strategy to Save the Planet. This selection comes from Chapter 12: Introduction to Strategy and it contains a brief observation on how most activists lack a clean and concise strategy as well as an overview of the Principles of War & Strategy.

I do not wish to kill nor to be killed, but I can foresee circumstances in which both these things would be by me unavoidable. We preserve the so-called peace of our community by deeds of petty violence every day. Look at the policeman’s billy and handcuffs! Look at the jail! Look at the gallows! Look at the chaplain of the regiment! We are hoping only to live safely on the outskirts of this provisional army. So we defend ourselves and our hen-roosts, and maintain slavery.

—Henry David Thoreau, “A Plea for Captain John Brown”

Anarchist Michael Albert, in his memoir Remembering Tomorrow: From SDS to Life after Capitalism, writes, “In seeking social change, one of the biggest problems I have encountered is that activists have been insufficiently strategic.” While it’s true, he notes, that various progressive movements “did just sometimes enact bad strategy,” in his experience they “often had no strategy at all.”

It would be an understatement to say that this inheritance is a huge problem for resistance groups. There are plenty of possible ways to explain it. Because we sometimes don’t articulate a clear strategy because we’re outnumbered and overrun with crises or immediate emergencies, so that we can never focus on long-term planning. Or because our groups are fractured, and devising a strategy requires a level of practical agreement that we can’t muster. Or it can be because we’re not fighting to win. Or because many of us don’t understand the difference between a strategy and a goal or a wish. Or because we don’t teach ourselves and others to think in strategic terms. Or because people are acting like dissidents instead of resisters. Or because our so-called strategy often boils down to asking someone else to do something for us. Or because we’re just not trying hard enough.

One major reason that resistance strategy is underdeveloped is because thinkers and planners who do articulate strategies are often attacked for doing so. People can always find something to disagree with. That’s especially true when any one strategy is expected to solve all problems or address all causes claimed by progressives. If a movement depends more on ideological purity than it does on accomplishments, it’s easy for internal sectarian arguments to take priority over getting things done. It’s easier to attack resistance strategists in a burst of horizontal hostility than it is to get things together and attack those in power.

The good news is that we can learn from a few resistance groups with successful and well-articulated strategies. The study of strategy itself has been extensive for centuries. The fundamentals of strategy are foundational for military officers, as they must be for resistance cadres and leaders.

Principles of War and Strategy

The US Army’s field manual entitled Operations introduces nine “Principles of War.” The authors emphasize that these are “not a checklist” and do not apply the same way in every situation. Instead, they are characteristic of successful operations and, when used in the study of historical conflicts, are “powerful tools for analysis.” The nine “core concepts” are:

Objective. “Direct every military operation toward a clearly defined, decisive, and attainable objective.” A clear goal is a prerequisite to selecting a strategy. It is also something that many resistance groups lack. The second and third requirements—that the objective be both decisive and attainable—are worth underlining. A decisive objective is one that will have a clear impact on the larger strategy and struggle. There is no point in going after one of questionable or little value. And, obviously, the objective itself must be attainable, because otherwise efforts toward that operation objective are a waste of time, energy, and risk.

Offensive. “Seize, retain, and exploit the initiative.” To seize the initiative is to determine the course of battle, the place, and the nature of conflict. To give up or lose the initiative is to allow the enemy to determine those things. Too often resistance groups, especially those based on lobbying or demands, give up the initiative to those in power. Seizing the initiative positions the fight on our terms, forcing them to react to us. Operations that seize the initiative are typically offensive in nature.

Mass. “Concentrate the effects of combat power at the decisive place and time.” Where the field manual says “combat power,” we can say “force” more generally. When Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest summed up his military theory as “get there first with the most,” this is what he was talking about. We must engage those in power where we are strong and they are weak. We must strike when we have overwhelming force, and maneuver instead of engaging when we are outmatched. We have limited numbers and limited force, so we have to use that when and where it will be most effective.

Economy of Force. “Allocate minimum essential combat power to secondary efforts.” In order to achieve superiority of force in decisive operations, it’s usually necessary to divert people and resources from less urgent or decisive operations. Economy of force requires that all personnel are performing important tasks, regardless of whether they are engaged in decisive operations or not.

Maneuver. “Place the enemy in a disadvantageous position through the flexible application of combat power.” This hinges on mobility and flexibility, which are essential for asymmetric conflict. The fewer a group’s numbers, the more mobile and agile it must be. This may mean concentrating forces, it may mean dispersing them, it may mean moving them, or it may mean hiding them. This is necessary to keep the enemy off balance and make that group’s actions unpredictable.

Unity of Command. “For every objective, ensure unity of effort under one responsible commander.” This is where some streams of anarchist culture come up against millennia of strategic advice. We’ve already discussed this under decision making and elsewhere, but it’s worth repeating. No strategy can be implemented by consensus under dangerous or emergency circumstances. Participatory decision making is not compatible with high-risk or urgent operations. That’s why the anarchist columns in the Spanish Civil War had officers even though they despised rulers. A group may arrive at a strategy by any decision-making method it desires, but when it comes to implementation, a hierarchy is required to undertake more serious action.

Security. “Never permit the enemy to acquire an unexpected advantage.” When fighting in a panoptican, this principle becomes even more important. Security is a cornerstone of strategy as well as of organization.

Surprise. “Strike the enemy at a time or place or in a manner for which they are unprepared.” This is key to asymmetric conflict—and again, not especially compatible with a open or participatory decision-making structures. Resistance movements are almost always outnumbered, which means they have to use surprise and swiftness to strike and accomplish their objective before those in power can marshal an overpowering response.

Simplicity. “Prepare clear, uncomplicated plans and clear, concise orders to ensure thorough understanding.” The plan must be clear and direct so that everyone understands it. The simpler a plan is, the more reliably it can be implemented by multiple cooperating groups.

In fact, these strategic principles might as well come from a different dimension as far as most (liberal) protest actions are concerned. That’s because the military strategist has the same broad objective as the radical strategist: to use the decisive application of force to accomplish a task. Neither strategist is under the illusion that the opponent is going to correct a “mistake” if this enemy gets enough information or that success can occur by simple persuasion without the backing of political force. Furthermore, both are able to clearly identify their enemy. If you identify with those in power, you’ll never be able to fight back. An oppositional culture has an identity that is distinct from that of those in power; this is a defining element of cultures of resistance. Without a clear knowledge of who your adversary is, you either end up fighting everyone (in classic horizontal hostility) or no one, and, in either case, your struggle cannot succeed.

Featured image by Denis Fadeev, CC BY SA 3.0 unported.

by DGR News Service | Jun 9, 2020 | The Problem: Civilization

Today we share an excerpt of the book Deep Green Resistance: Strategy to Save the Planet. This selection comes from Chapter 2: Civilization and other Hazards. In the preceding pages, various ecological crises were presented.

The media report on these crises as though they [ecological crises] are all separate issues. They are not. They are inextricably entangled with each other and with the culture that causes them. As such, all of these problems have important commonalities, with major implications for our strategy to resist them.

These problems are urgent, severe, and worsening, and the most worrisome hazards share certain characteristics:

1. They are progressive, not probabilistic.

These problems are getting worse. These problems are not hypothetical, projected, or “merely possible” like Y 2K, asteroid impacts, nuclear war, or super-volcanoes. These crises are not “possible” or “impending”-they are well underway and will continue to worsen. The only uncertainty is how fast, and thus how long our window of action is.

2. They are rapid, but not instant.

These crises arose rapidly, but often not so rapidly as to trigger a prompt response; people get used to them, a phenomenon called the “shifting baselines syndrome.” For example, wildlife populations are often compared to measures from fifty years ago, instead of measures from before civilization, which makes the damage seem much less severe than it actually is. Even trends which appear slow at first glance (like global warming) are extremely rapid when considered over longer timescales, such as the duration of the human race or even the duration of civilization.

3. They are nonlinear, and sometimes runaway or self-sustaining.

The hazards get worse over time, but often in unpredictable ways with sudden spikes or discontinuities. A 10 percent increase of greenhouse gases might produce 10 percent warming or it might cause far more. Also, the various crises interact to create cascading disasters far worse than any one alone.

Hurricanes (such as Katrina) may be worsened by global warming and by habitat destruction in their paths (Katrina’s impact was worsened by wetlands destruction). The human impact may then be worsened further by poverty and the use of the police, military, and hired mercenaries (like Blackwater) to impede the ability of those poor people to move freely or access basic and necessary supplies.

4. These crises have long lead or lag times.

The problems are often created long before they become a visible issue. They also grow or accelerate exponentially, such that action must be taken well in advance of the crisis to be effective. Although an alert minority is usually aware of the issue, the problem may have become very serious and entrenched before gaining the attention, let alone the action, of the majority.

Peak oil was predicted with a high degree of accuracy in 1956. The greenhouse effect was discovered in 1824, and industrially caused global warming was predicted by Swedish scientist Svante Arrhenius in 1867.

5. Hazards have deeply rooted momentum.

These crises are rooted in the most fundamental practices and infrastructure of civilization. Social convention, the concentration of power, and dominant economic systems all prevent the necessary changes. If I ran a corporation and tried to be genuinely sustainable, the company would soon be out-competed and go bankrupt.’ If I were a politician and I banned the majority of unsustainable practices, I would promptly be ejected from office (or more likely, assassinated).

6. They are industrially driven.

In virtually all cases, industry is the primary culprit, either because it consumes resources itself (e.g., oil and coal) or permits resource extraction and global trade that would otherwise be extremely difficult (e.g., bottom trawling) . Furthermore, industrial capitalism and industrial governments offer artificial subsidies for ecocidal practices that would not otherwise be economically tenable. Factors like overpopulation (as discussed shortly) are secondary or tertiary at best.

7. They provide benefits to the powerful and costs to the powerless.

The acts that cause these crises-all long-standing economic activities-offer short-term benefits to those who are already powerful. But these hazards are most dangerous and damaging to the people who are poorest and most powerless.

8. They facilitate temporary victories and permanent losses.

No successes we might have are guaranteed to last as long as industrial civilization stands. Conversely, most of our losses are effectively permanent. Extinct species cannot be resurrected. Overdrawn aquifers or clear-cut forests will not return to their original states on timescales meaningful to humans.

The destruction of land-based cultures, and the deliberate impoverishment of much of humanity, results in major loss and long-term social trauma. With sufficient action, it’s possible to solve many of the problems we face, but if that action doesn’t materialize in time, the effects are irreversible.

9. Proposed “solutions” often make things worse.

Because of all the qualities noted above, analysis of the hazards tends to be superficial and based on short-term thinking. Even though analysts who look at the big picture globally may use large amounts of data, they often refuse to ask deeper or more uncomfortable questions.

The hasty enthusiasm for industrial biofuels is one manifestation of this. Biofuels have been embraced by some as a perfect ecological replacement for petroleum. The problems with this are many, but chief among them is the simple fact that growing plants for vehicle fuel takes land the planet simply can’t spare. Soy, palm, and sugar cane plantations for oil and ethanol are now driving the destruction of tropical rainforest in the Amazon and Southeast Asia.

Critics like Jane Goodall and the Rainforest Action Network argue that the plantations on rainforest land destroy habitat and water cycles, worsen global warming, destroy and pollute the soil, and displace land-based peoples. This so-called solution to the catastrophe of petroleum ends up being just as bad-if not worse-than petroleum.

10. The hazards do not result from any single program.

They tend to result from the underlying structure and essential nature of civilization, not from any particular industry, technology, government, or social attitude. Even global warming, which is caused primarily by burning fossil fuels, is the result of many kinds of industries using many kinds of fossil fuels as well as deforestation and agriculture.

To learn more about the true environmental costs of renewable energy, read Bright Green Lies to be released in 2021.

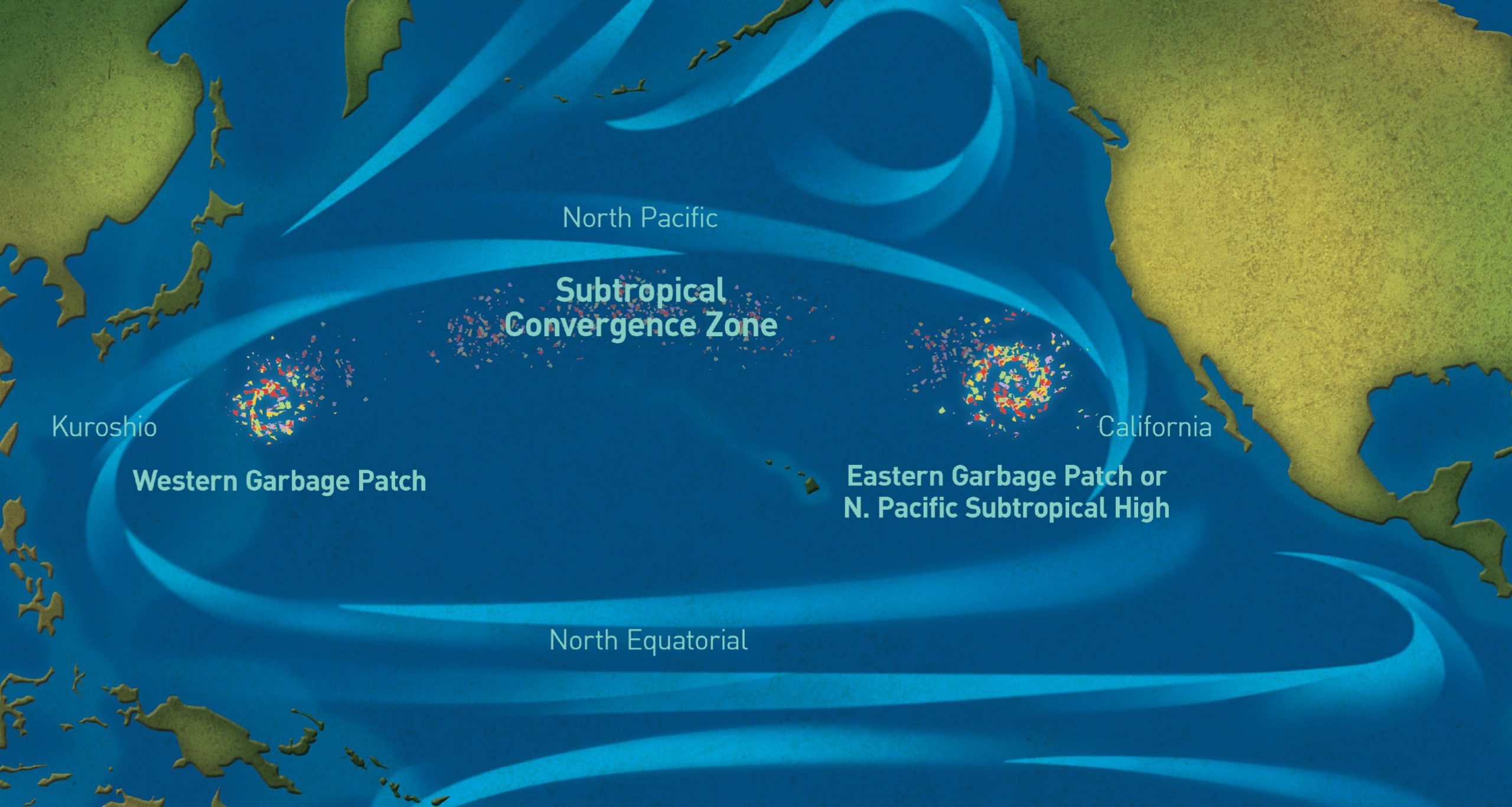

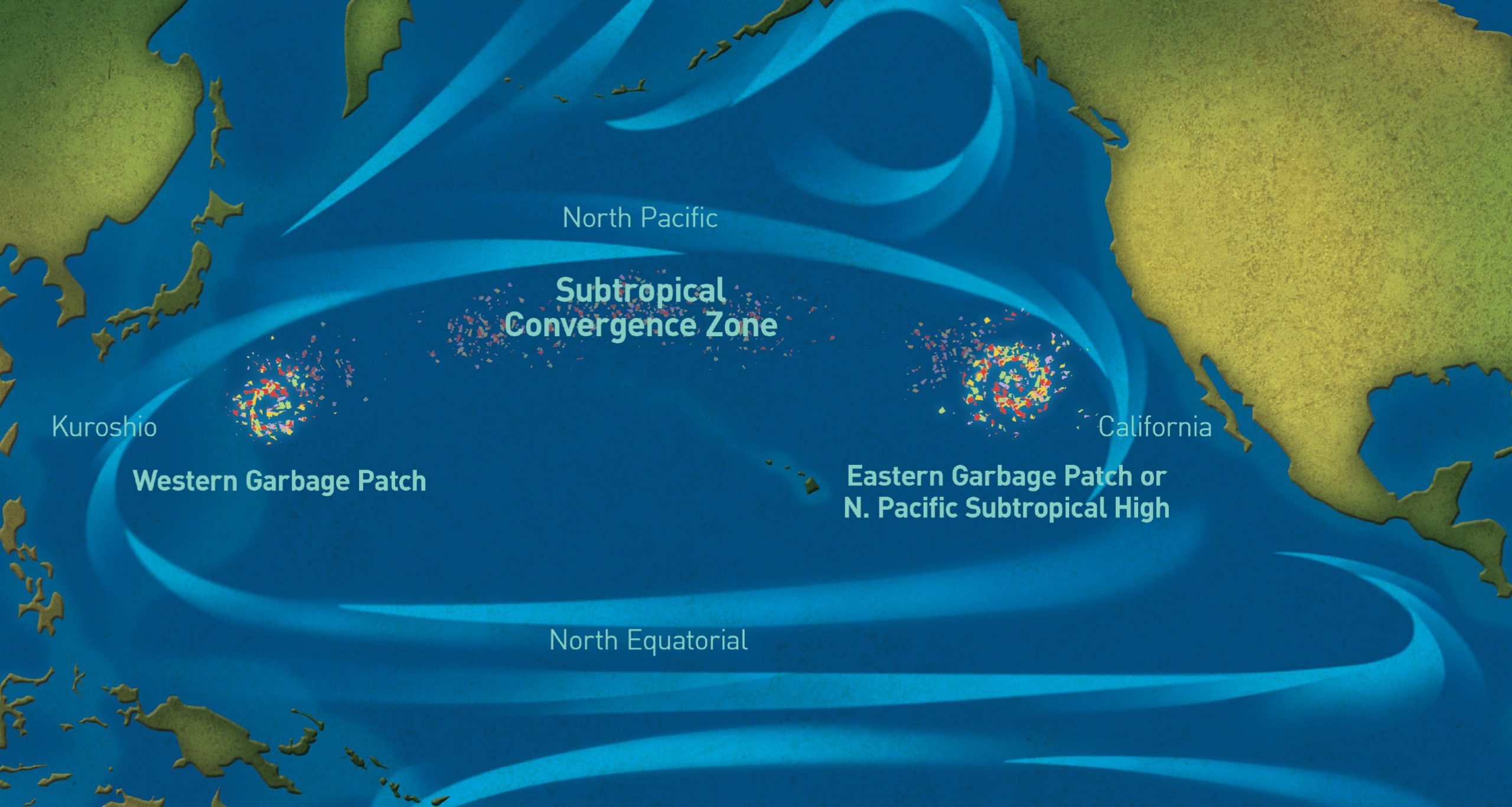

Featured image depicts major floating garbage patches in the Pacific Ocean.