by DGR News Service | Nov 2, 2021 | Climate Change, Education, Human Supremacy, Indirect Action, The Problem: Civilization, The Solution: Resistance

This is an excerpt from the book Bright Green Lies, P. 20 ff

By Derrick Jensen, Lierre Keith and Max Wilbert

What this adds up to should be clear enough, yet many people who should know better choose not to see it. This is business-as- usual: the expansive, colonizing, progressive human narrative, shorn only of the carbon. It is the latest phase of our careless, self-absorbed, ambition-addled destruction of the wild, the unpolluted, and the nonhuman. It is the mass destruction of the world’s remaining wild places in order to feed the human economy. And without any sense of irony, people are calling this “environmentalism.”1 —PAUL KINGSNORTH

Once upon a time, environmentalism was about saving wild beings and wild places from destruction. “The beauty of the living world I was trying to save has always been uppermost in my mind,” Rachel Carson wrote to a friend as she finished the manuscript that would become Silent Spring. “That, and anger at the senseless, brutish things that were being done.”2 She wrote with unapologetic reverence of “the oak and maple and birch” in autumn, the foxes in the morning mist, the cool streams and the shady ponds, and, of course, the birds: “In the mornings, which had once throbbed with the dawn chorus of robins, catbirds, doves, jays, and wrens, and scores of other bird voices, there was now no sound; only silence lay over the fields and woods and marshes.”3 Her editor noted that Silent Spring required a “sense of almost religious dedication” as well as “extraordinary courage.”4 Carson knew the chemical industry would come after her, and come it did, in attacks as “bitter and unscrupulous as anything of the sort since the publication of Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species a century before.”5 Seriously ill with the cancer that would kill her, Carson fought back in defense of the living world, testifying with calm fortitude before President John F. Kennedy’s Science Advisory Committee and the U.S. Senate. She did these things because she had to. “There would be no peace for me,” she wrote to a friend, “if I kept silent.”6

Carson’s work inspired the grassroots environmental movement; the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA); and the passage of the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, and the Endangered Species Act. Silent Spring was more than a critique of pesticides—it was a clarion call against “the basic irresponsibility of an industrialized, technological society toward the natural world.”7 Today’s environmental movement stands upon the shoulders of giants, but something has gone terribly wrong with it. Carson didn’t save the birds from DDT so that her legatees could blithely offer them up to wind turbines. We are writing this book because we want our environmental movement back.

Mainstream environmentalists now overwhelmingly prioritize saving industrial civilization over saving life on the planet. The how and the why of this institutional capture is the subject for another book, but the capture is near total. For example, Lester Brown, founder of the Worldwatch Institute and Earth Policy Institute—someone who has been labeled as “one of the world’s most influential thinkers” and “the guru of the environmental movement”8—routinely makes comments like, “We talk about saving the planet.… But the planet’s going to be around for a while. The question is, can we save civilization? That’s what’s at stake now, and I don’t think we’ve yet realized it.” Brown wrote this in an article entitled “The Race to Save Civilization.”9

The world is being killed because of civilization, yet what Brown says is at stake, and what he’s racing to save, is precisely the social structure causing the harm: civilization. Not saving salmon. Not monarch butterflies. Not oceans. Not the planet. Saving civilization. Brown is not alone. Peter Kareiva, chief scientist for The Nature Conservancy, more or less constantly pushes the line that “Instead of pursuing the protection of biodiversity for biodiversity’s sake, a new conservation should seek to enhance those natural systems that benefit the widest number of [human] people…. Conservation will measure its achievement in large part by its relevance to [human] people.”10 Bill McKibben, who works tirelessly and selflessly to raise awareness about global warming, and who has been called “probably America’s most important environmentalist,” constantly stresses his work is about saving civilization, with articles like “Civilization’s Last Chance,”11 or with quotes like, “We’re losing the fight, badly and quickly—losing it because, most of all, we remain in denial about the peril that human civilization is in.”12

We’ll bet you that polar bears, walruses, and glaciers would have preferred that sentence ended a different way.

In 2014 the Environmental Laureates’ Declaration on Climate Change was signed by “160 leading environmentalists from 44 countries” who were “calling on the world’s foundations and philanthropies to take a stand against global warming.” Why did they take this stand? Because global warming “threatens to cause the very fabric of civilization to crash.” The declaration con- cludes: “We, 160 winners of the world’s environmental prizes, call on foundations and philanthropists everywhere to deploy their endowments urgently in the effort to save civilization.”13

Coral reefs, emperor penguins, and Joshua trees probably wish that sentence would have ended differently. The entire declaration, signed by “160 winners of the world’s environmental prizes,” never once mentions harm to the natural world. In fact, it never mentions the natural world at all.

Are leatherback turtles, American pikas, and flying foxes “abstract ecological issues,” or are they our kin, each imbued with their own “wild and precious life”?14 Wes Stephenson, yet another climate activist, has this to say: “I’m not an environmentalist. Most of the people in the climate movement that I know are not environmentalists. They are young people who didn’t necessarily come up through the environmental movement, so they don’t think of themselves as environmentalists. They think of themselves as climate activists and as human rights activists. The terms ‘environment’ and ‘environmentalism’ carry baggage historically and culturally. It has been more about protecting the natural world, protecting other species, and conservation of wild places than it has been about the welfare of human beings. I come at from the opposite direction. It’s first and foremost about human beings.”15

Note that Stephenson calls “protecting the natural world, protecting other species, and conservation of wild places” baggage. Naomi Klein states explicitly in the film This Changes Everything: “I’ve been to more climate rallies than I can count, but the polar bears? They still don’t do it for me. I wish them well, but if there’s one thing I’ve learned, it’s that stopping climate change isn’t really about them, it’s about us.”

And finally, Kumi Naidoo, former head of Greenpeace International, says: “The struggle has never been about saving the planet. The planet does not need saving.”16 When Naidoo said that, in December 2015, it was 50 degrees Fahrenheit at the North Pole, much warmer than normal, far above freezing in the middle of winter.

1 Paul Kingsnorth, “Confessions of a recovering environmentalist,” Orion Magazine, December 23, 2011.

2 Rachel Carson, Silent Spring (Greenwich, CT: Fawcett Publishing, 1962), 9.

3 Ibid, 10.

4 Ibid, 8.

5 Ibid, 8.

6 Ibid, 8.

7 Ibid, 8.

8 “Biography of Lester Brown,” Earth Policy Institute.

9 Lester Brown, “The Race to Save Civilization,” Tikkun, September/October 2010, 25(5): 58.

10 Peter Kareiva, Michelle Marvier, and Robert Lalasz, “Conservation in the Anthropocene: Beyond Solitude and Fragility,” Breakthrough Journal, Winter 2012.

11 Bill McKibben, “Civilization’s Last Chance,” Los Angeles Times, May 11, 2008.

12 Bill McKibben, “Global Warming’s Terrifying New Math,” Rolling Stone, August 2, 2012.

13 “Environmental Laureates’ Declaration on Climate Change,” European Environment Foundation, September 15, 2014. It shouldn’t surprise us that the person behind this declaration is a solar energy entrepreneur. It probably also shouldn’t surprise us that he’s begging for money.

14 “Wild and precious life” is from Mary Oliver’s poem “The Summer Day.” House of Light (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1992).

15 Gabrielle Gurley, “From journalist to climate crusader: Wen Stephenson moves to the front lines of climate movement,” Commonwealth: Politics, Ideas & Civic Life in Massachusetts, November 10, 2015.

16 Emma Howard and John Vidal, “Kumi Naidoo: The Struggle Has Never Been About Saving the Planet,” The Guardian, December 30, 2015.

by DGR News Service | Dec 21, 2020 | Direct Action

Excerpted from Chapter 8, “Organizational Structure,” of the book Deep Green Resistance: Strategy to Save the Planet by Derrick Jensen, Lierre Keith, and Aric McBay.

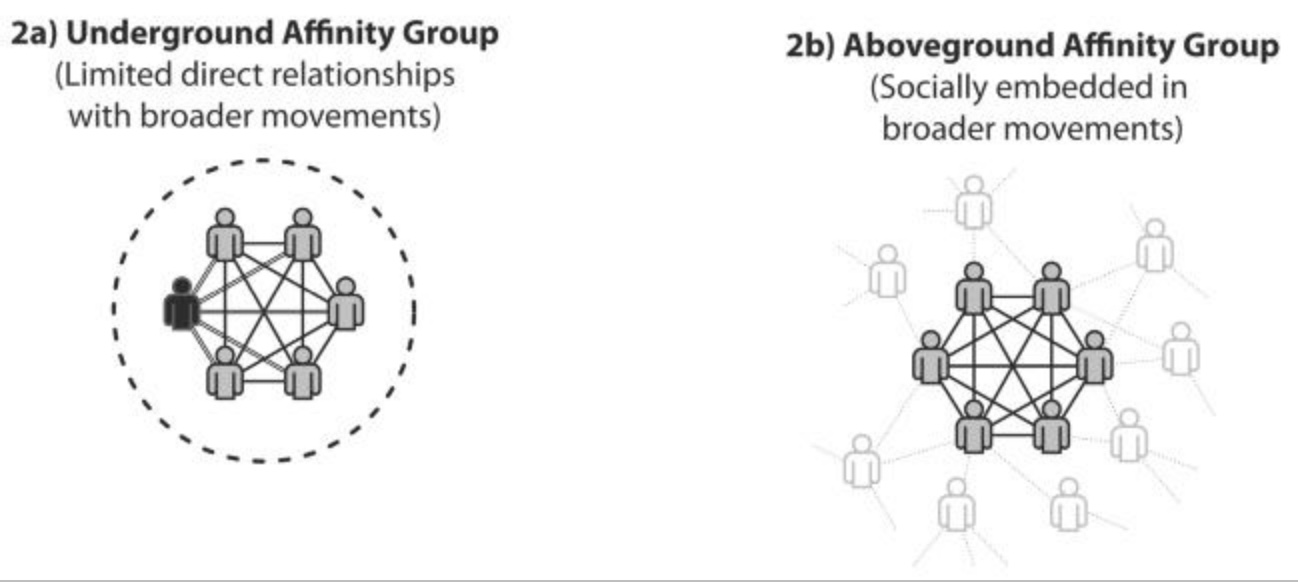

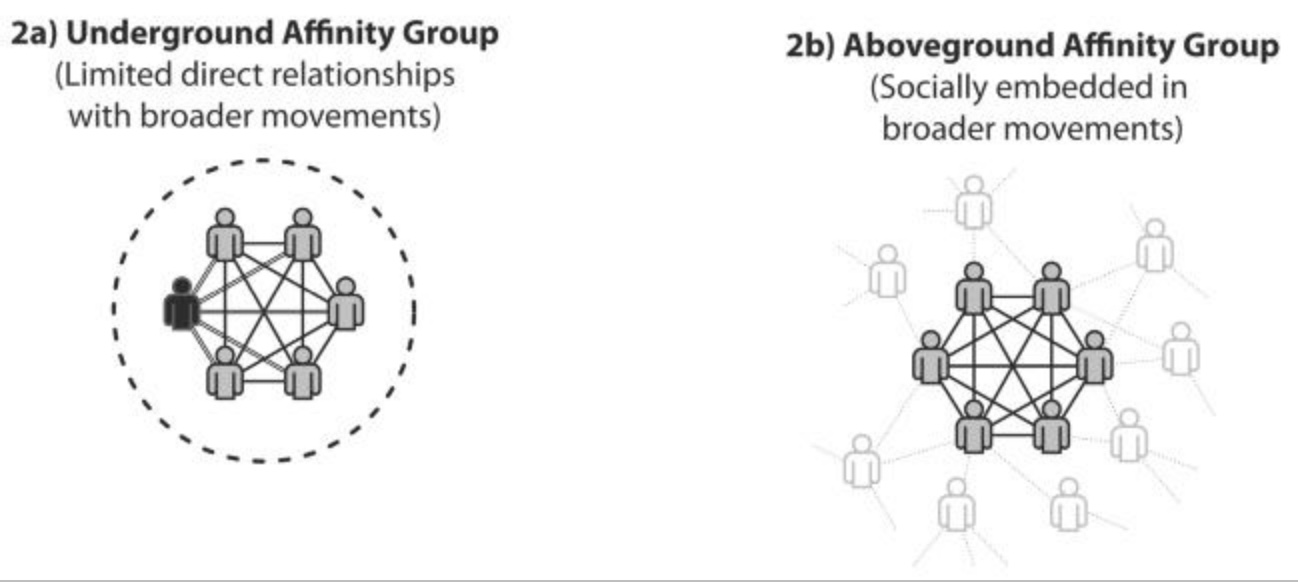

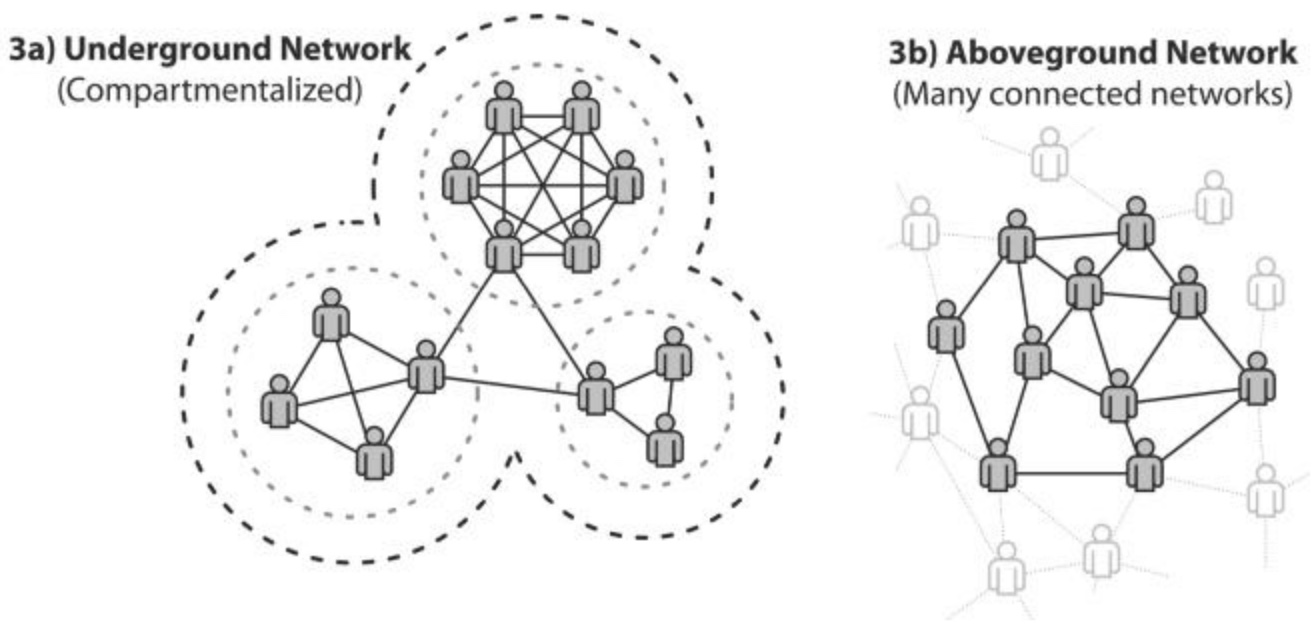

The most basic organizational unit is the affinity group. A group of fewer than a dozen people is a good compromise between groups too large to be socially functional, and too small to carry out important tasks. The activist’s affinity group has a mirror in the underground cell, and in the military squad. Groups this size are small enough for participatory decision making to take place, or in the case of a hierarchal group, for orders to be relayed quickly and easily.

Figure 8-2

The underground affinity group (Figure 8-2a, shown here with a distinct leader) has many benefits for the members. Members can specialize in different areas of expertise, pool their efforts, work together toward shared goals, and watch each others’ backs. The group can also offer social and emotional support that is much needed for people working underground. Because they do not have direct relationships with other movements or underground groups, they can be relatively secure. However, due to their close working relationships, if one member of the group is compromised, the entire affinity group is likely to be compromised. The more members are in the group, the more risk involved (and the more different relationships to deal with). Also because the affinity group is limited in size, it is limited in terms of the size of objectives it can go after, and their geographic range.

Aboveground affinity groups (Figure 8-2b) share many of the same clear benefits of a small-scale, deliberate community. However, they may rely more on outside relationships, both for friends and fellow activists. Members may also easily belong to more than one affinity group to follow their own interests and passions. This is not the case with underground groups—members must belong only to one affinity group or they are putting all groups at risk.

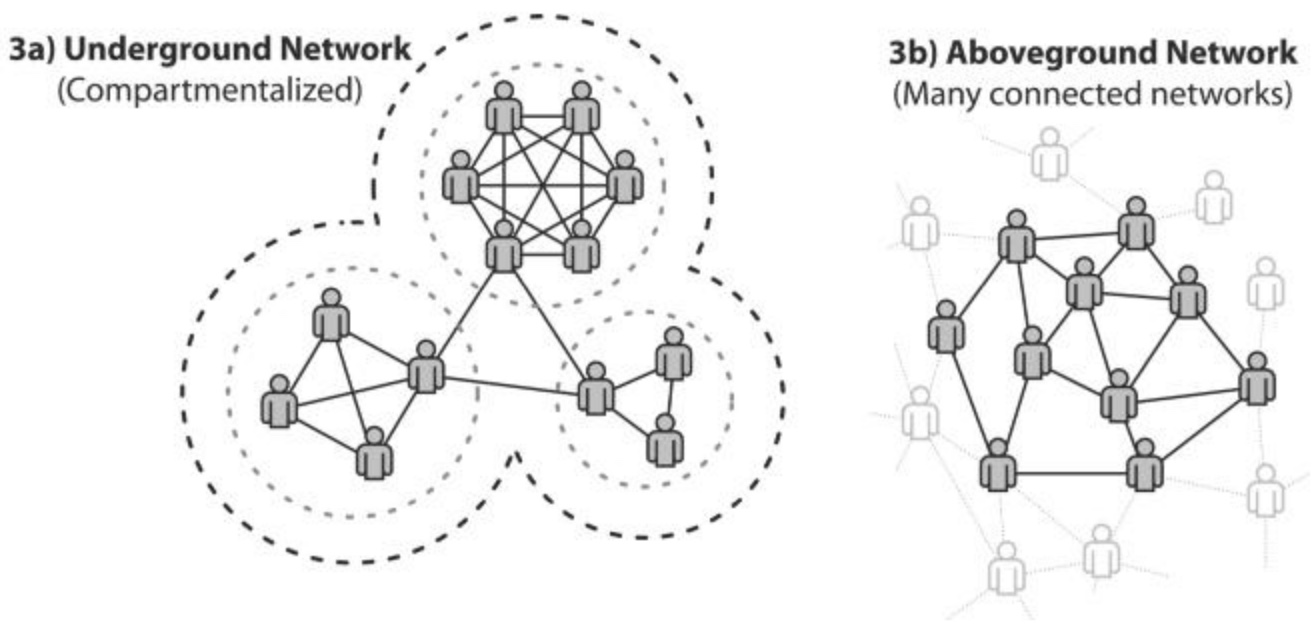

The obvious benefit of multiple overlapping aboveground groups is the formation of larger movements or “mesh” networks (Figure 8-3b). These larger, diverse groups are better able to get a lot done, although sometimes they can have coordination or unity problems if they grow beyond a certain size. In naturally forming social networks, each member of the group is likely to be only a few degrees of separation from any other person. This can be fantastic for sharing information or finding new contacts. However, for a group concerned about security issues, this type of organization is a disaster. If any individual were compromised, that person could easily compromise large numbers of people. Even if some members of the network can’t be compromised, the sheer number of connections between people makes it easy to just bypass the people who can’t be compromised. The kind of decentralized network that makes social networks so robust is a security nightmare.

Figure 8-3

Underground groups that want to bring larger numbers of people into the organization must take a different approach. A security-conscious underground network will largely consist of a number of different cells with limited connections to other cells (Figure 8-3a). One person in a cell would know all of the members in that cell, as well as a single member in another cell or two. This allows coordination and shared information between cells. This network is “compartmentalized.” Like all underground groups, it has a firewall between itself and the aboveground. But there are also different, internal firewalls between sections.

Such a network does have downsides. Having only a single link between cells is beneficial, in that if one cell is compromised, it is much more difficult to compromise other cells. However, the connection is also more brittle. If a “liaison” is removed from the network or loses communication for whatever reason, then the network may be broken up. A backup plan for regaining communication can reduce the damage from this, but increase the level of risk. Also, the nonhierarchal nature of this network means that choosing actions can be more difficult. The more cells are involved, the larger the number of people who must have critical information in order to make decisions. That said, these groups can be very effective and functional. The famous Underground Railroad was a decentralized underground network.

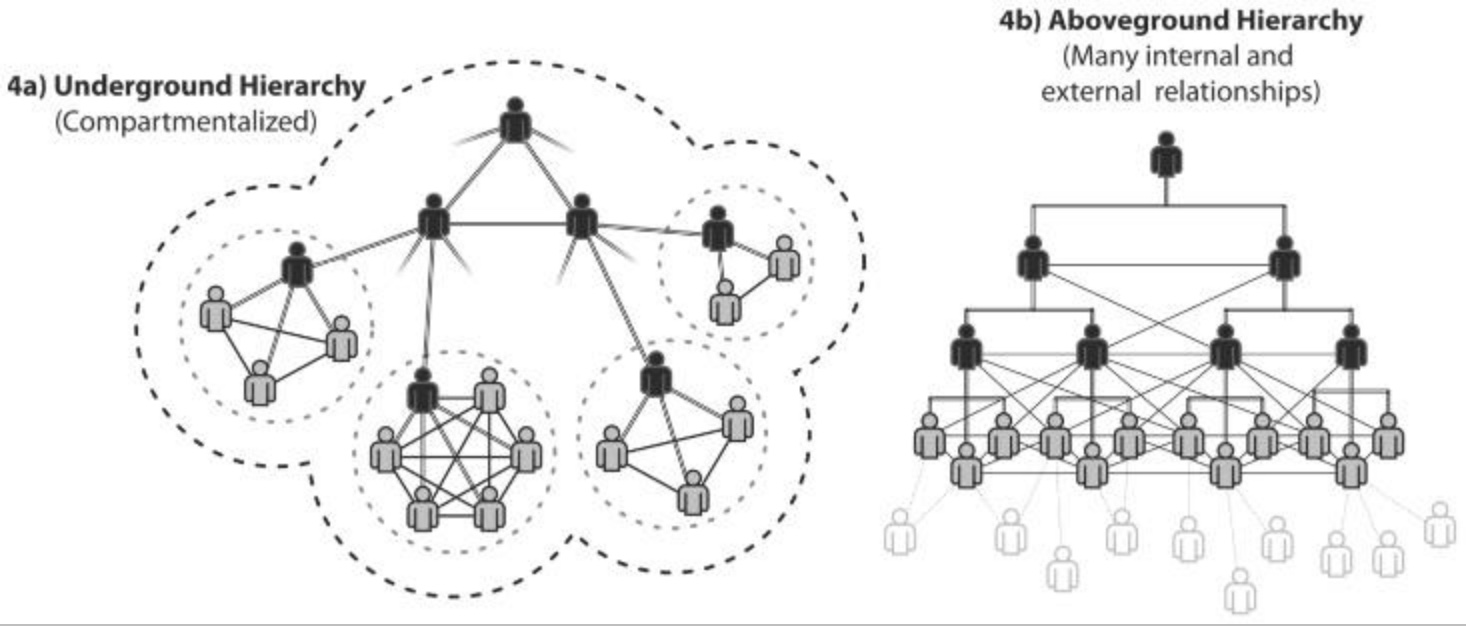

Figure 8.4

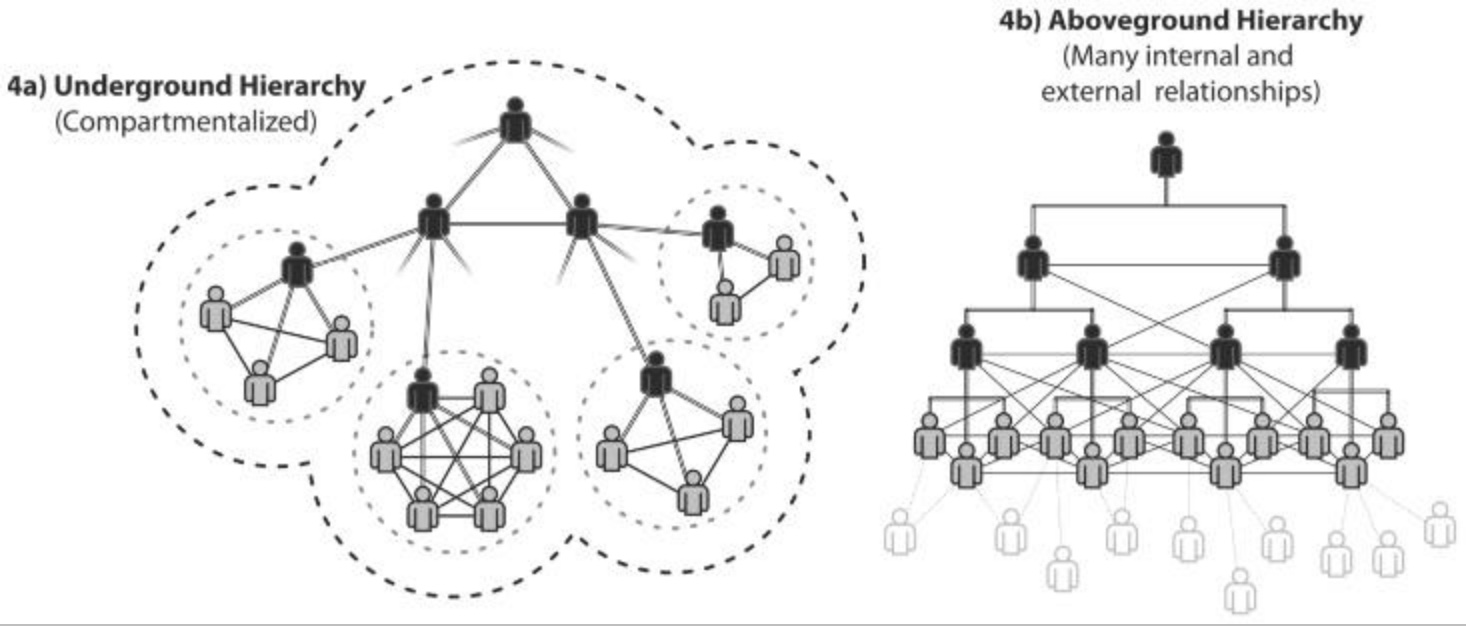

Some of these problems are addressed in both aboveground and underground groups through the use of a hierarchy. In underground hierarchies (Figure 8-4a), large numbers of cells can be connected and coordinated through branching, pyramidal structures. These types of groups have vastly greater potential than smaller networks. Their numbers make for increased risk, yes, but that increased risk can be reduced by the use of specialized counterintelligence cells within the network and wide-ranging coordinated attacks.

Aboveground hierarchies (Figure 8-4b) are quite familiar and common, in part because they are highly effective ways of coordinating large numbers of people to accomplish a specific objective. As shown, aboveground hierarchies facilitate many relationships between people in different parts of the hierarchy. This lack of compartmentalization might be good in terms of productivity, but not in terms of security.

There are very specific situations in which it may be acceptable to send information through an underground group’s firewall. The recruitment process necessarily involves communication with people outside the group. However, these people would not be active in aboveground movements, and, at least initially, they would only know one member of the organization in one cell. Of course, there are no direct relationships between people in the underground and aboveground groups.

In certain situations, one-way (and likely anonymous) communications may take place across the firewall. Informants who want to give information to the resistance network may pass on information to a member of an internal intelligence group. However, the intelligence group would not share information about identities or the network with those people. Information may also travel one-way in the opposite direction. The underground groups may want to send communiqués or other information to the media or press office. Of course, any communication across the firewall, even those thought anonymous, entails a certain small amount of risk. Therefore, the benefits must outweigh the risks.

All of the examples illustrated are simplified and generalized. Resistance groups in history have had a wide variety of internal structures based on these general templates. They often had to make a deliberate compromise between organizational security (which comes from loosely connected and decentralized cells) and organizational effectiveness (which comes from more densely connected and centralized cells).

by DGR News Service | Nov 27, 2020 | Agriculture, Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Climate Change, Mining & Drilling, Toxification

The Problem

by Lierre Keith

From the introduction to the book Deep Green Resistance: Strategy to Save the Planet.

“You cannot live a political life, you cannot live a moral life if you’re not willing to open your eyes and see the world more clearly. See some of the injustice that’s going on. Try to make yourself aware of what’s happening in the world. And when you are aware, you have a responsibility to act.”

—Bill Ayers, cofounder of the Weather Underground.

A black tern weighs barely two ounces. On energy reserves less than a small bag of M&M’s and wings that stretch to cover twelve inches, she flies thousands of miles, searching for the wetlands that will harbor her young. Every year the journey gets longer as the wetlands are desiccated for human demands. Every year the tern, desperate and hungry, loses, while civilization, endless and sanguineous, wins.

A polar bear should weigh 650 pounds. Her energy reserves are meant to see her through nine long months of dark, denned gestation, and then lactation, when she will give up her dwindling stores to the needy mouths of her species’ future. But in some areas, the female’s weight before hibernation has already dropped from 650 to 507 pounds. Meanwhile, the ice has evaporated like the wetlands. When she wakes, the waters will stretch impassably open, and there is no Abrahamic god of bears to part them for her.

The Aldabra snail should weigh something, but all that’s left to weigh are skeletons, bits of orange and indigo shells. The snail has been declared not just extinct, but the first casualty of global warming. In dry periods, the snail hibernated. The young of any species are always more vulnerable, as they have no reserves from which to draw. In this case, the adults’ “reproductive success” was a “complete failure.” In plain terms, the babies died and kept dying, and a species millions of years old is now a pile of shell fragments.

What is your personal carrying capacity for grief, rage, despair?

We are living in a period of mass extinction. The numbers stand at 200 species a day. That’s 73,000 a year. This culture is oblivious to their passing, feels entitled to their every last niche, and there is no roll call on the nightly news.

There is a name for the tsunami wave of extermination: the Holocene extinction event. There’s no asteroid this time, only human behavior, behavior that we could choose to stop. Adolph Eichman’s excuse was that no one told him that the concentration camps were wrong. We’ve all seen the pictures of the drowning polar bears. Are we so ethically numb that we need to be told this is wrong?

There are voices raised in concern, even anguish, at the plight of the earth, the rending of its species. “Only zero emissions can prevent a warmer planet,” one pair of climatologists declare. James Lovelock, originator of the Gaia hypothesis, states bluntly that global warming has passed the tipping point, carbon offsetting is a joke, and “individual lifestyle adjustments” are “a deluded fantasy.” It’s all true, and self-evident.

“Simple living” should start with simple observation: if burning fossil fuels will kill the planet, then stop burning them.

But that conclusion, in all its stark clarity, is not the popular one to draw. The moment policy makers and environmental groups start offering solutions is the exact moment when they stop telling the truth, inconvenient or otherwise. Google “global warming solutions.” The first paid sponsor, Campaign Earth, urges “No doom and gloom!! When was the last time depression got you really motivated? We’re here to inspire realistic action steps and stories of success.” By “realistic” they don’t mean solutions that actually match the scale of the problem. They mean the usual consumer choices—cloth shopping bags, travel mugs, and misguided dietary advice—which will do exactly nothing to disrupt the troika of industrialization, capitalism, and patriarchy that is skinning the planet alive.

As Derrick has pointed out elsewhere, even if every American took every single action suggested by Al Gore it would only reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 21 percent. Aric tells a stark truth: even if through simple living and rigorous recycling you stopped your own average American’s annual one ton of garbage production, “your per capita share of the industrial waste produced in the US is still almost twenty-six tons. That’s thirty-seven times as much waste as you were able to save by eliminating a full 100 percent of your personal waste.”

Industrialism itself is what has to stop.

There is no kinder, greener version that will do the trick of leaving us a living planet. In blunt terms, industrialization is a process of taking entire communities of living beings and turning them into commodities and dead zones. Could it be done more “efficiently”? Sure, we could use a little less fossil fuels, but it still ends in the same wastelands of land, water, and sky. We could stretch this endgame out another twenty years, but the planet still dies. Trace every industrial artifact back to its source—which isn’t hard, as they all leave trails of blood—and you find the same devastation: mining, clear-cuts, dams, agriculture. And now tar sands, mountaintop removal, wind farms (which might better be called dead bird and bat farms).

No amount of renewables is going to make up for the fossil fuels or change the nature of the extraction, both of which are prerequisites for this way of life. Neither fossil fuels nor extracted substances will ever be sustainable; by definition, they will run out. Bringing a cloth shopping bag to the store, even if you walk there in your Global Warming Flip-Flops, will not stop the tar sands. But since these actions also won’t disrupt anyone’s life, they’re declared both realistic and successful.

The next site’s Take Action page includes the usual: buying light bulbs, inflating tires, filling dishwashers, shortening showers, and rearranging the deck chairs. It also offers the ever-crucial Global Warming Bracelets and, more importantly, Flip-Flops. Polar bears everywhere are weeping with relief.

The first noncommercial site is the Union of Concerned Scientists. As one might expect, there are no exclamation points, but instead a statement that “[t]he burning of fossil fuel (oil, coal, and natural gas) alone counts for about 75 percent of annual CO2 emissions.” This is followed by a list of Five Sensible Steps. Step One? No, not stop burning fossil fuels—“Make Better Cars and SUVs.” Never mind that the automobile itself is the pollution, with its demands—for space, for speed, for fuel—in complete opposition to the needs of both a viable human community and a living planet. Like all the others, the scientists refuse to call industrial civilization into question. We can have a living planet and the consumption that’s killing the planet, can’t we?

The principle here is very simple.

As Derrick has written, “[A]ny social system based on the use of nonrenewable resources is by definition unsustainable.” Just to be clear, nonrenewable means it will eventually run out. Once you’ve grasped that intellectual complexity, you can move on to the next level. “Any culture based on the nonrenewable use of renewable resources is just as unsustainable.” Trees are renewable. But if we use them faster than they can grow, the forest will turn to desert. Which is precisely what civilization has been doing for its 10,000 year campaign, running through soil, rivers, and forests as well as metal, coal, and oil. Now the oceans are almost dead and their plankton populations are collapsing, populations that both feed the life of the oceans and create oxygen for the planet.

What will we fill our lungs with when they are gone? The plastics with which industrial civilization is replacing them? In parts of the Pacific, plastic outweighs plankton 48 to 1. Imagine if it were your blood, your heart, crammed with toxic materials—not just chemicals, but physical gunk—until there was ten times more of it than you. What metaphor is adequate for the dying plankton? Cancer? Suffocation? Crucifixion?

But the oceans don’t need our metaphors. They need action. They need industrial civilization to stop destroying and devouring. In other words, they need us to make it stop.

Which is why we are writing this book.

THE DEEP GREEN RESISTANCE BOOK

Strategy to Save the Planet:

https://deepgreenresistance.net/en/resistance/the-problem/the-problem/

by DGR News Service | Oct 3, 2020 | Culture of Resistance, Movement Building & Support, Women & Radical Feminism

Excerpted from the book Deep Green Resistance — Chapter 15: Our Best Hope by Lierre Keith.

Featured Image: Women in 1919 Revolution in Egypt via Flickr

5. Deep Green Resistance means repair of human cultures

That repair must, in the words of Andrea Dworkin, be based on “one absolute standard of human dignity.” That starts in a fierce loyalty to everyone’s physical boundaries and sexual integrity. It continues with food, shelter, and health care, and the firm knowledge that our basic needs are secure. And it opens out into a democracy where all people get an equal say in the decisions that affect them. That includes economic as well as political decisions. There’s no point in civic democracy if the economy is hierarchical and the rich can rule through wealth.

People need a say in their material culture and their basic sustenance.

For most of our time on this planet, we had that. Even after the rise of civilization, there were many social, legal, and religious strictures that protected people and society from the accumulation of wealth. There exists an abundance of ideas on how to transform our communities away from domination and accumulation and toward justice and human rights. We don’t lack analysis or plans; the only thing missing is the decision to see them through.

We also need that new story that so many of the Transitioners prioritize. It’s important to recognize first that not everyone has lost their original story. There are indigenous peoples still holding on to theirs. According to Barbara Alice Mann,

The contrast between western patriarchal and Iroquoian matriarchal thought could not be more clear.… I do not think it is possible to examine the real impetus behind mother-right unless we walk boldly up to the spiritual underpinnings of its systems. By the same token, we cannot free ourselves of the serious damage of patriarchy, unless we appreciate where matriarchy’s spiritual allegiances lie.

The Iroquois are unapologetic about the fact that spirit informs and undergirds all our social, economic, and governmental structures. Every council of any honor begins with thanksgiving, that is, an energy-out broadcast, to make way for the energy in-gathering required by the One Good Mind of Consensus. When a council fails, people just assume that the faithkeeper who opened it did a poor job in the thanksgiving department. In a thanksgiving address, all the spirits of Blood and Breath (or Earth and Sky) are properly gathered and acknowledged, with the ultimate acknowledgment being that the One Good Mind of Consensus requires the active participation of not just an elite but everyone in the community. This is a foundational insight of all matriarchies.

She describes a culture where “things happen by consultation, not by fiat,” based on a spiritual understanding of everyone’s participation in the cosmos rather than the “paranoid isolation” brought on by the temper tantrums of a sociopathic God. This is the difference between cultures of matriarchy and patriarchy, egalitarianism and domination, participation and power.

Such stories need to be told, but more, they need to be instituted. All the stories in the world will do no good if they end with the telling.

One institution that deserves serious consideration is a true people’s militia. Right now in the United States only the right wing is organizing itself into an armed force. In 2009, antigovernment militias, described by the Southern Poverty Law Center as “the paramilitary arm of the Patriot movement,” grew threefold, from forty-two to 127. We should be putting weapons in the hands of people who believe in human rights and who are sworn to protect them, not in those of people who feel threatened because we have a black president.

If jack-booted, racist, and increasingly paranoid thugs coalesce into an organized movement with its eye on political power, we don’t need to relive Germany in 1936 to know where it may end, especially as energy descent and economic decline continue. Contemporaneous with a people’s militia would be training in both the theory and practice of mass civil disobedience to reject illegitimate government or a coup if that comes to pass. Gene Sharp’s Civilian-Based Defense explains how this technique works with successful examples from history. His book is a curriculum that should be added to Transition Towns and other descent preparation initiatives.

But if the people with the worst values are the ones with the guns and the training, we may be very sorry. This is a dilemma with which progressives and radicals should be grappling. A large and honorable proportion of the left believes in nonviolence, a belief that for many reaches a spiritual calling. But societies through history and currently around the globe have degenerated into petty tyrannies with competing atrocities. Personal faith in the innate goodness of human beings is not enough of a deterrent or shield for me.

A true people’s militia would be sworn to uphold human rights, including women’s rights. The horrors of history include male sexual sadism on a mass scale. Women are afraid of men with guns for good reason. But rape is not inevitable. It’s a behavior that springs from specific social norms, norms that a culture of resistance can and must confront and counteract, whether or not we have a people’s militia. We need a zero tolerance policy for abuse, especially sexual abuse.

Military organizations, like any other culture, can promote rape or stop it. Throughout history, soldiers, especially mercenary soldiers, have often been granted the “right” to rape and plunder as part of their payment. Other militaries have taken strong stands against rape. Writes Jean Bethke Elshtain, “The Israeli army … are scrupulous in prohibiting their soldiers to rape. The British and United States armies, as well, have not been armies to whom rape was routinely ‘permitted,’ with officers looking the other way, although British and American soldiers have committed ‘opportunistic’ rapes. Even in the Vietnam War, where incidents of rape, torture and massacre emerged, raping was sporadic and opportunistic rather than routine.” The history of military atrocities against civilians is a history; it’s not universal, and it’s not inevitable. Elshtain continues,

“War is not a freeform unleashing of violence; rather, fighting is constrained by considerations of war aims, strategies and permissible tactics. Were war simply an unbridled release of violence, wars would be even more destructive than they are.”

Western nations, over hundreds of years, assembled an unwritten code of conduct for militaries, known as the “customary law of war,” which tried to limit the suffering of soldiers and to safeguard civilians. This was eventually codified into the Hague Convention Number IV of 1907 and the Geneva Convention of 1949. These attempted to limit looting and property destruction and to protect noncombatants. The Uniform Code of Military Justice is very clear that rape is unacceptable, and even gets the finer points of how “consent” with an armed assailant is a pretty meaningless concept. Elshtain also notes that “[the] maximum punishment for rape is death. Thus, interestingly, rape is a capital offense under the Uniform Code of Military Justice, by contrast to most civilian legal codes.

Getting the command structure to take rape and human rights abuses seriously is, of course, the next step. As Elshtain points out, “It is difficult to bring offenders to trial unless the leaders of the military forces are themselves determined to ferret out and punish tormentors of civilian populations. Needless to say, if the strategy is itself one of tormenting civilians, rapists are not going to be called before a bar of justice.”

It will be up to the founders and the officers of new communities to set the norms and to make those norms feminist from the beginning. The following would go a long way toward helping create a true people’s militia, and not just another organization of armed thugs to “trample the grass”—the women and girls who so often suffer when men fight for power.

- Female officers. Women must be in positions of authority from the beginning, and their authority needs absolute respect from male officers.

- Training curriculum that includes feminism, rape awareness, and abuse dynamics, and a code of conduct that emphasizes honorable character in protecting and defending human rights.

- Zero tolerance for misogynist slurs, sexual harassment, and assault amongst all members.

- Clear policies for reporting infringements and clear consequences.

- Background checks to exclude batterers and sex offenders from the militia.

- Severe consequences for any abuse of civilians.

A people’s militia could garner widespread support by following a model of community engagement, much as the Black Panthers grew through their free breakfast program. Besides basic activities like weapons training and military maneuvers, the militia could help the surrounding community with the kind of services that are always appreciated: delivering firewood to the elderly or fixing the roof of the grammar school. The idea of a militia will make some people uneasy, and respectful personal and community relationships would help overcome their reticence.

by DGR News Service | Oct 1, 2020 | Culture of Resistance, Movement Building & Support

Excerpted from the book Deep Green Resistance — Chapter 15: Our Best Hope by Lierre Keith.

4. Deep Green Resistance requires repair of the planet

This principle has the built-in prerequisite, of course, of stopping the destruction. Burning fossil fuels has to stop. Likewise, industrial logging, fishing, and agriculture have to stop. Denmark and New Zealand, for instance, have outlawed coal plants—there’s no reason the rest of the world can’t follow.

Stopping the destruction requires an honest look at the culture that a true solar economy can support. We need a new story, but we don’t need fairy tales, and the bread crumbs of windfarms and biofuels will not lead us home.

To actively repair the planet requires understanding the damage. The necessary repair—the return of forests, prairies, and wetlands—could happen over a reasonable fifty to one hundred years if we were to voluntarily reduce our numbers. This is not a technical problem: we actually do know where babies come from and there are a multitude of ways to keep them from coming. As discussed in Chapter 5, Other Plans, overshoot is a social problem caused by the intersections of patriarchy, civilization, and capitalism.

People are still missing the correct information. Right now, the grocery stores are full here. In poor areas, the so-called food deserts may be filled with cheap carbohydrates and vegetable oil, but they are still full. But how many people could any given local foodshed actually support, and support sustainably, indefinitely? Whatever that number is, it needs to be emblazoned like an icon across every public space and taken up as the baseline of the replacement culture. Our new story has to end, “And they lived happily ever after at 20,000 humans from here to the foothills.”

This is a job for the Transitioners and the permaculture wing, and so far, they’re getting it wrong. The Peak Oil Task Force in Bloomington, Indiana, for instance, put out a report entitled Redefining Prosperity: Energy Descent and Community Resilience. The report recognizes that the area does not have enough agricultural land to feed the population. They claim, however, that there is enough land within the city using labor-intensive cultivation methods to feed everyone on a “basic, albeit mostly vegetarian diet.” The real clue is that “vegetarian diet.” What they don’t understand is that soil is not just dirt. It is not an inert medium that needs nothing in order to keep producing food for humans. Soil is alive. It is kept alive by perennial polycultures—forests and prairies. The permanent cover protects it from sun, rain, and wind; the constant application of dead grass and leaves adds carbon and nutrients; and the root systems are crucial for soil’s survival, providing habitat for the microfauna that make land life possible.

Perennials, both trees and grasses, are deeply rooted. Annuals are not. Those deep roots reach into the rock that forms the substrate of our planet and pull up minerals, minerals which are necessary for the entire web of life. Without that action, the living world would eventually run out of minerals. Annuals, on the other hand, literally mine the soil, pulling out minerals with no ability to replace them. Every load of vegetables off the farm or out of the garden is a transfer of minerals that must be replaced. This is a crucial point that many sustainability writers do not understand: organic matter, nitrogen, and minerals all have to be replaced, since annual crops use them up.

John Jeavons, for instance, claims to be able to grow vast quantities of food crops with only vegetable compost as an input on his Common Ground demonstration site. But as one observer writes,

Sustainable Laytonville visited Common Ground. The gardens could only supply one meal a day because they didn’t have enough compost. The fallacy with Biointensive/Biodynamic and Permaculture is that they all require outside inputs whether it’s rock phosphate or rock dusts, etc. There is no way to have perpetual fertility and take a crop off and replace lost nutrients with the “leftovers” from the area under cultivation … even if the person’s urine, poop and bones were added back.

I have built beautiful garden soil, dark as chocolate and with a scent as deep, using leaves, spoiled hay, compost, and chickens. But I eventually was forced to realize the basic arithmetic in the math left a negative number. I was shifting fertility, not building it. The leaves and hay may have been throwaways to the lawn fetishists and the farmers, but they were also nutrients needed by the land from which they were taken. The suburban backyard that produced those leaves needed them. If I was using the leaves, the house owner was using packaged fertilizer instead. The addition of animal products—manure, bloodmeal, bonemeal—is essential for nitrogen and mineral replacement, and they are glaringly absent in most calculations I’ve seen for food self-sufficiency. Most people, no matter how well-intentioned, have no idea that both soil and plants need to eat.”

Annual crops use up the organic matter in the soil, whereas perennials build it. Processes like tilling and double digging not only mechanically destroy soil, they add oxygen, which causes more biological activity. That activity is the decay of organic matter. This releases both carbon and methane. One article in Science showed that all tillage systems are contributors to global warming, with wheat and soy as the worst. This is why, historically, agriculture marks the beginning of global warming. In contrast, because perennials build organic matter, they sequester both carbon and methane, at about 1,000 pounds per acre. And, of course, living forests and prairies will not stay alive without their animal cohorts, without the full complement of their community.

So be very wary of claims of how many people can be supported per acre in urban landscapes. It is about much more than just acreage. If you decide to undertake such calculations, consider that the soil in garden beds needs permanent cover. Where will that mulch come from? The soil needs to eat; where will the organic material and minerals come from? And people need to eat. We cannot live on the thin calories of vegetables, no matter how organic, to which 50,000 nerve-damaged Cubans can attest. So far, the Transitioners, even though many of them have a permaculture background, seem unaware of the biological constraints of soil and plants, which are, after all, living creatures with physical needs. In the end, the only closed loops that are actually closed are the perennial polycultures that this planet naturally organizes—the communities that agriculture has destroyed.

But as we have said, people’s backyard gardens are of little concern to the fate of our planet. Vegetables take up maybe 4 percent of agricultural land. What is of concern are the annual monocrops that provide the staple foods for the global population. Agriculture is the process that undergirds civilization. That is the destruction that must be repaired. Acre by acre, the living communities of forests, grasslands, and wetlands must be allowed to come home. We must love them enough to miss them and miss them enough to restore them.

The best hope for our planet lies in their restoration. Perennials build soil, and carbon is their building block. A 0.5 percent increase in organic matter—which even an anemic patch of grass can manage—distributed over 75 percent of the earth’s rangelands (11.25 billion acres) would equal 150 billion tons of carbon removed from the atmosphere. The current carbon concentrations are at 390 ppm. The prairies’ repair would drop that to 330 ppm. Peter Bane’s calculations show that restoring grasslands east of the Dakotas would instantaneously render the United States a carbon-sequestering nation. Ranchers Doniga Markegard and Susan Osofsky put it elegantly: “As a species, we need to shift from carbon-releasing agriculture to carbon-sequestering agriculture.”

That repair should be the main goal of the environmental movement. Unlike the Neverland of the Tilters’ solutions, we have the technology for prairie and forest restoration, and we know how to use it. And the grasses will be happy to do most of the work for us.

The food culture across the environmental movement is ideologically attached to a plant-based diet. That attachment is seriously obstructing our ability to name the problem and start working on the obvious solutions. Transition Town originator Rob Hopkins writes, “Reducing the amount of livestock will also be inevitable, as large-scale meat production is an absurd and unsustainable waste of resources.” Raising animals in factory farms—concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs)—and stuffing them with corn is absurd and cruel. But animals are necessary participants in biotic communities, helping to create the only sustainable food systems that have ever worked: they’re called forests, prairies, wetlands. In the aggregate, a living planet.

That same ideological attachment is the only excuse for the blindness to Cuban suffering and for the comments that 30 percent of Cubans are “still obese.” That figure is supposed to reassure us: see, nobody starves in this regime. What such comments betray is a frank ignorance about human biology. Eating a diet high in carbohydrates will make a large percentage of the population gain weight. Eating any sugar provokes a surge of insulin, to control the glucose levels in the bloodstream. The brain can only function within a narrow range of glucose levels. Insulin is an emergency response, sweeping sugar out of the blood and into the cells for storage. Insulin has been dubbed “the fat storage hormone” because this is one of its main functions. Its corresponding hormone, glucagon, is what unlocks that stored energy. But in the presence of insulin, glucagon can’t get to that energy. This is why poor people the world over tend to be fat: all they have to eat is cheap carbohydrate, which trigger fat storage. If the plant diet defenders knew the basics of human biology, that weight gain would be an obvious symptom of nutritional deficiencies, not evidence of their absence. Fat people are probably the most exhausted humans on the planet, as minute to minute their bodies cannot access the energy they need to function. Instead of understanding, they are faced with moral judgment and social disapproval across the political spectrum.

I don’t want any part of a culture that inflicts that kind of cruelty and humiliation on anyone. Shaun Chamberlin writes, “The perception of heavy meat eaters could be set to change in much the same way that the perception of [SUV] drivers has done.” Even if he was right that meat is inherently a problem, this attitude of shaming people for their simple animal hunger is repugnant. Half the population—the female half—already feels self-loathing over every mouthful, no matter what, and how little, is on their plates. Food is not an appropriate arena for that kind of negative social pressure, especially not in an image-based culture saturated in misogyny. Food should be a nourishing and nurturing part of our culture, including our culture of resistance. If Chamberlin wants an appropriate target for social shaming, he can start with men who rape and batter, and then move on to men who refuse to get vasectomies—that would be a better use of his moral approbation.

Getting past that ideological attachment would also bring clarity to the bewildered attitude that underlies many of these “radical” writers’ observations about dietary behavior. Accepting that humans have a biological need for nutrient-dense food, it’s no longer a surprise that when poor people get more money, they will buy more meat. They’re not actually satisfied on the nutritional wonders of a plant-based diet. Ideology is a thin gruel and imposing it on people who are chronically malnourished is not only morally suspect, it won’t work. The human animal will be fed. And if we had stuck to our original food, we would not have devoured the planet.

Restoring agricultural land to grasslands with appropriate ruminants has multiple benefits beyond carbon sequestration. It spells the end of feedlots and factory farming. It’s healthier for humans. It would eliminate essentially all fertilizer and pesticides, which would eliminate the dead zones at the mouths of rivers around globe. The one in the Gulf of Mexico, for instance, is the size of New Jersey. It would stop the catastrophic flooding that results from annual monocrops, flooding being the obvious outcome of destroying wetlands.

It also scales up instantly. Farmers can turn a profit the first year of grass-based farming. This is in dramatic contrast to growing corn, soy, and wheat, in which they can never make a profit. Right now six corporations, including Monsanto and Cargill, control the world food supply. Because of their monopoly, they can drive prices down below the cost of production. The only reason farmers stay in business is because the federal government—that would be the US taxpayers—make up the difference, which comes to billions of dollars a year. The farmers are essentially serfs to the grain cartels, and dependent on handouts from the federal government. But grass-fed beef and bison can liberate them in one year. We don’t even need government policy to get started on the most basic repair of our planet. We just need to create the demand and set up the infrastructure one town, one region at a time.

Land with appropriate rainfall can grow two steers per acre. But those steers can be raised in two ways. You can destroy the grasses, plant corn, and feed that corn to CAFO steers, making them and their human consumers sick in the process. Or you can skip the fossil fuels and the torture, the habitat destruction, the dead zones that used to be bays and oceans, and let those steer eat grass. Either method produces the same amount of food for humans, but one destroys the cycle of life while the other participates in it. I can tell you with certainty which food the red-legged frogs and the black-footed ferrets are voting for: let them eat grass.

Repairing those grasslands will also profoundly restore wildlife habitat to the animals that need a home. Even if the rest of the above reasons weren’t true, that repair would still be necessary. The acronym HANPP stands for “human appropriation of net primary production.” It’s a measure of how much of the biomass produced annually on earth is used by humans. Right now, 83 percent of the terrestrial biosphere is under direct human influence, and 36 percent of the earth’s bioproductive surface is completely dominated by humans. By any measure, that is vastly more than our share. Humans have no right to destroy everyone else’s home, 200 species at a time. It is our responsibility not just to stop it, but to fix it. Civilizations are, in the end, cultures of human entitlement, and they’ve taken all there is to take.

Featured image: Soy plantation via Pixabay