by DGR News Service | Jul 30, 2016 | ANALYSIS, Colonialism & Conquest, Repression at Home, The Problem: Civilization

Aric McBay

Originally published at inthewake.org

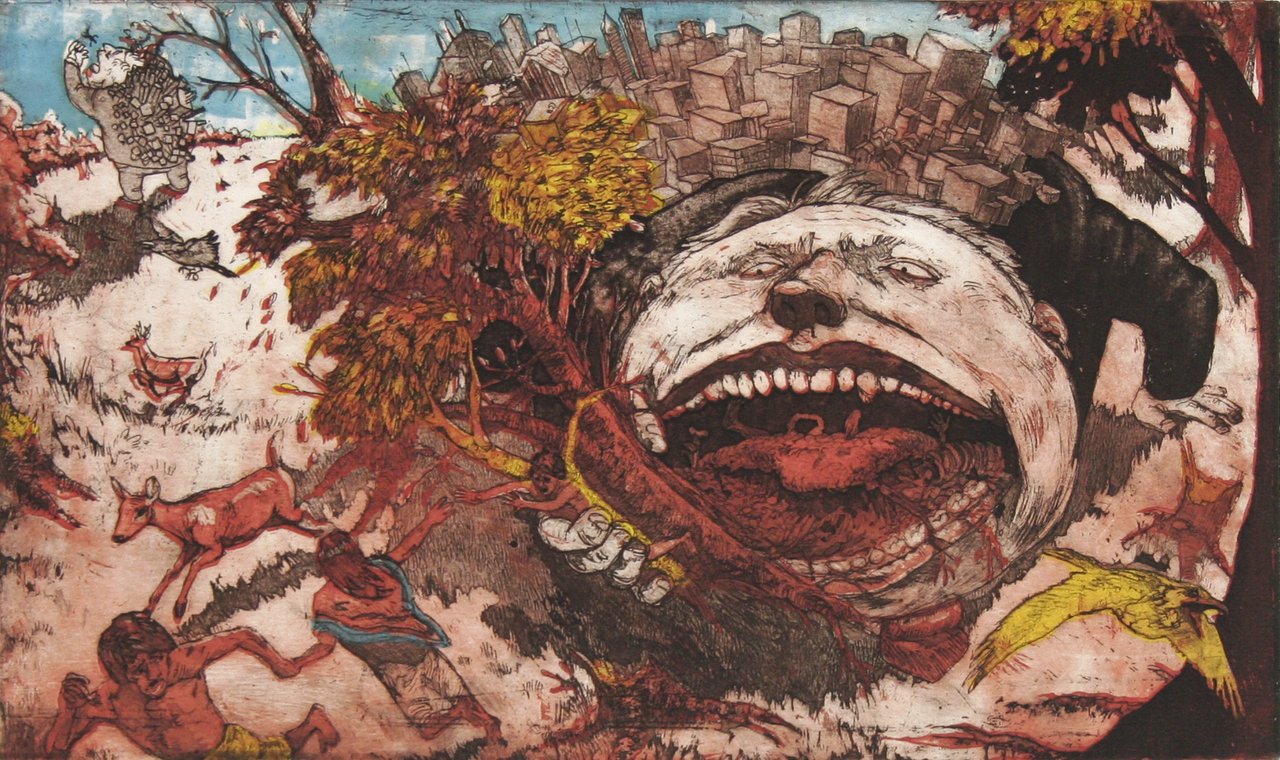

When some people hear that we want to “end civilization” they initially respond negatively, because of their positive associations with the word “civilization.” This piece is an attempt to clarify, define and describe what I mean by “civilization.”

One dictionary definition1 reads:

civilization

- a society in an advanced state of social development (eg, with complex legal and political and religious organizations); “the people slowly progressed from barbarism to civilization” [syn: civilisation]

- the social process whereby societies achieve civilization [syn: civilisation]

- a particular society at a particular time and place; “early Mayan civilization” [syn: culture, civilisation]

- the quality of excellence in thought and manners and taste; “a man of intellectual refinement”; “he is remembered for his generosity and civilization” [syn: refinement, civilisation]

The synonyms include “advancement,” “breeding,” “civility,” “cultivation,” “culture,” “development,” “edification,” “education,” “elevation,” “enlightenment,” “illumination,” “polish,” “progress,” and “refinement”. Of course. As Derrick Jensen asks, “can you imagine writers of dictionaries willingly classifying themselves as members of ‘a low, undeveloped, or backward state of human society’?”

In contrast, the antonyms of “civilization” include “barbarism,” “savagery,” “wilderness,” and “wildness.” These are the words that civilized people use to refer to those they view as being outside of civilization—in particular, indigenous peoples. “Barbarous,” as in “barbarian,” comes from a Greek word, meaning “non-Greek, foreign.” The word “savage” comes from the Latin “silvaticus” meaning “of the woods.” The origins seem harmless enough, but it’s very instructive to see how civilized people have used these words2:

barbarity

- The quality of being shockingly cruel and inhumane [syn: atrocity, atrociousness, barbarousness, heinousness]

- A brutal barbarous savage act [syn: brutality, barbarism, savagery]

savagery

- The quality or condition of being savage.

- An act of violent cruelty.

- Savage behavior or nature; barbarity.

These associations of cruelty with the uncivilized are, however, in glaring opposition to the historical record of interactions between civilized and indigenous peoples.

Let us take one of the most famous examples of “contact” between civilized and indigenous peoples. When Christopher Columbus first arrived in the “Americas” he noted that he was impressed by the indigenous peoples, writing in his journal that they had a “naked innocence … They are very gentle without knowing what evil is, without killing, without stealing.”

And so he decided “they will make excellent servants.”

In 1493, with the permission of the Spanish Crown, he appointed himself “viceroy and governor” of the Caribbean and the Americas. He installed himself on the island now divided between Haiti and the Dominican republic and began to systematically enslave and exterminate the indigenous population. (The Taino population of the island was not civilized, in contrast to the civilized Inca who the conquistadors also invaded in Central America.) Within three years he had managed to reduce the indigenous population from eight million to three million. By 1514 only 22,000 of the indigenous population remained, and after 1542 they were considered extinct.3

The tribute system, instituted by [Columbus] sometime in 1495, was a simple and brutal way of fulfilling the Spanish lust for gold while acknowledging the Spanish distaste for labor. Every Taino over the age of fourteen had to supply the rulers with a hawk’s bell of gold every three months (or, in gold-deficient areas, twenty-five pounds of spun cotton; those who did were given a token to wear around their necks as proof that they had made their payment; those did not were … “punished” – by having their hands cut off … and [being] left to bleed to death.4

More than 10,000 people were killed this way during Columbus’ time as governor. On countless occasions, these civilized invaders engaged in torture, rape, and massacres. The Spaniards

… made bets as to who would slit a man in two, or cut off his head at one blow; or they opened up his bowels. They tore the babes from their mother’s breast by their feet and dashed their heads against the rocks … They spitted the bodies of other babes, together with their mothers and all who were before them, on their swords.5

On another occasion:

A Spaniard … suddenly drew his sword. Then the whole hundred drew theirs and began to rip open the bellies, to cut and kill – men, women, children and old folk, all of whom were seated off guard and frightened … And within two credos, not a man of them there remains alive. The Spaniards enter the large house nearby, for this was happening at its door, and in the same way, with cuts and stabs, began to kill as many as were found there, so that a stream of blood was running, as if a number of cows had perished.6

This pattern of one-way, unprovoked, inexcusable cruelty and viciousness occurred in countless interactions between civilized and indigenous people through history.

This phenomena is well-documented in excellent books including Ward Churchill’s A Little Matter of Genocide: Holocaust and Denial in the Americas, 1492 to the Present, Kirkpatrick Sale’s The Conquest of Paradise: Christopher Columbus and the Columbian Legacy, and Dee Brown’s Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West. Farley Mowat’s books, especially Walking on the Land, The Deer People, and The Desperate People document this as well with an emphasis on the northern and arctic regions of North America.

There is also good information in Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States and Voices of a People’s History of the United States. Eduardo Galeando’s incredible Memory of Fire trilogy covers this topic as well, with an emphasis on Latin America (this epic trilogy reviews numerous related injustices and revolts). Jack D Forbes’ book Columbus and Other Cannibals: The Wetiko Disease of Exploitation, Imperialism and Terrorism is highly recommended. You can also find information in Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies, although I often disagree with the author’s premises and approach.

The same kind of attacks civilized people committed against indigenous peoples were also consistently perpetrated against non-human animal and plant species, who were wiped out (often deliberately) even when civilized people didn’t need them for food; simply as blood-sport. For further readings on this, check out great books like Farley Mowat’s extensive and crushing Sea of Slaughter, or Clive Ponting’s A Green History of the World: The Environment and the Collapse of Great Civilizations (which also examines precivilized history and European colonialism).

With this history of atrocity in mind, we should (if we haven’t already) cease using the propaganda definitions of civilized as “good” and uncivilized as “bad” and seek a more accurate and useful definition. Anthropologists and other thinkers have come up with a number of somewhat less biased definitions of civilization.

Nineteenth century English anthropologist E B Tylor defined civilization as life in cities that is organized by government and facilitated by scribes (which means the use of writing). In these societies, he noted, there is a resource “surplus”, which can be traded or taken (though war or exploitation) which allows for specialization in the cities.

Derrick Jensen, having recognized the serious flaws in the popular, dictionary definition of civilization, writes:

I would define a civilization much more precisely, and I believe more usefully, as a culture – that is, a complex of stories, institutions, and artifacts – that both leads to and emerges from the growth of cities (civilization, see civil: from civis, meaning citizen, from latin civitatis, meaning state or city), with cities being defined – so as to distinguish them from camps, villages, and so on – as people living more or less permanently in one place in densities high enough to require the routine importation of food and other necessities of life.

Jensen also observes that because cities need to import these necessities of life and to grow, they must also create systems for the perpetual centralization of resources, yielding “an increasing region of unsustainability surrounded by an increasingly exploited countryside.”

Contemporary anthropologist John H Bodley writes: “The principle function of civilization is to organize overlapping social networks of ideological, political, economic, and military power that differentially benefit privileged households.”7 In other words, in civilization institutions like churches, corporations and militaries exist and are used to funnel resources and power to the rulers and the elite.

The twentieth century historian and sociologist Lewis Mumford wrote one of my favourite and most cutting and succinct definitions of civilization. He uses the term civilization

… to denote the group of institutions that first took form under kingship. Its chief features, constant in varying proportions throughout history, are the centralization of political power, the separation of classes, the lifetime division of labor, the mechanization of production, the magnification of military power, the economic exploitation of the weak, and the universal introduction of slavery and forced labor for both industrial and military purposes.8

Taking various anthropological and historical definitions into account, we can come up with some common properties of civilizations (as opposed to indigenous groups).

- People live in permanent settlements, and a significant number of them in cities.

- The society depends on large-scale agriculture (which is needed to support dense, non-food-growing urban populations).

- The society has rulers and some form of “aristocracy” with centralized political, economic, and military power, who exist by exploiting the mass of people.

- The elite (and possibly others) use writing and numbers to keep track of commodities, the spoils of war, and so on.

- There is slavery and forced labour either by the direct use of physical violence, or by economic coercion and violence (through which people are systematically deprived of choices outside the wage economy).

- There are large armies and institutionalized warfare.

- Production is mechanized, either through physical machines or the use of humans as though they were machines (this point will be expanded on in other writings here soon).

- Large, complex institutions exist to mediate and control the behaviour of people, through as their learning and worldview (schools and churches), as well as their relationships with each other, with the unknown, and with the nature world (churches and organized religion).

Anthropologist Stanley Diamond recognized the common thread in all of these attributes when he wrote; “Civilization originates in conquest abroad and repression at home”.9

This common thread is control. Civilization is a culture of control. In civilizations, a small group of people controls a large group of people through the institutions of civilization. If they are beyond the frontier of that civilization, then that control will come in the form of armies and missionaries (be they religious or technical specialists). If the people to be controlled are inside of the cities, inside of civilization, then the control may come through domestic militaries (ie, police). However, it is likely cheaper and less overtly violent to condition of certain types of behaviour through religion, schools or media, and related means, than through the use of outright force (which requires a substantial investment in weapons, surveillance and labour).

That works very effectively in combination with economic and agricultural control. If you control the supply of food and other essentials of life, people have to do what you say or they die. People inside of cities inherently depend on food systems controlled by the rulers to survive, since the (commonly accepted) definition of a city is that the population is dense enough to require the importation of food.

For a higher degree of control, rulers have combined control of food and agriculture with conditioning that reinforces their supremacy. In the dominant, capitalist society, the rich control the supply of food and essentials, and the content of the media and the schools. The schools and workplaces act as a selection process: those who demonstrate their ability to cooperate with those in power by behaving properly and doing what they’re told at work and school have access to higher paying jobs involving less labour. Those who cannot or will not do what they’re told are excluded from easy access to food and essentials (by having access only to menial jobs), and must work very hard to survive, or become poor and/or homeless. People higher on this hierarchy are mostly spared the economic and physical violence imposed on those lower on the hierarchy. A highly rationalized system of exploitation like this helps to increase the efficiency of the system by reducing the chance of resistance or outright rebellion of the populace.

The media’s propaganda systems have most people convinced that this system is somehow “natural” or “necessary”—but of course, it is both completely artificial and a direct result of the actions of those in power (and the inactions of those who believe that they benefit from it, or are prevented from acting through violence or the threat of violence).

In contradiction to the idea that the dominant culture’s way of living is “natural,” human beings lived as small, ecological, participatory, equitable groups for more than 99% of human history. There are a number of excellent books and articles comparing indigenous societies to civilization:

These sources show there were healthy, equitable and ecological communities in the past, and that they were the norm for countless generations. It is civilization that is monstrous and aberrant.

Living inside of the controlling environment of civilization is an inherently traumatic experience, although the degree of trauma varies with personal circumstance and the amounts of privilege different people have in society. Derrick Jensen makes this point very well in A Language Older than Words (Context Books, 2000), and Chellis Glendinning covers it as well in My name is Chellis.

Endnotes

1. Definition of “civilization” is from WordNet R 2.0, 2003, Princeton University

2. Definitions of “barbarity” and “savagery” are from The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition, 2000, Houghton Mifflin Company.

3. I owe many of the sources in this section to the research of Ward Churchill. The figure of eight million is from chapter six of Essays in Population History, Vol I by Sherburn F Cook and Woodrow Borah (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971). The figure of three million is from is from a survey at the time by Bartolome de Las Casas covered in J B Thatcher, Christopher Columbus, two volumes (New York: Putnam’s, 1903-1904) Vol 2, page 384 ff. They were considered extinct by the Spanish census at the time, which is summarized in Lewis Hanke’s The Spanish Struggle for Justice in the Conquest of America (Philapelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1947) page 200 ff.

4. Sale, Kirkpatrick. The Conquest of Paradise: Christopher Columbus and the Columbian Legacy (New York: Alfred A Knopf, 1990) page 155.

5. de Las Casas, Bartolome. The Spanish Colonie: Brevisima revacion (New York: University Microfilms Reprint, 1966).

6. de Las Casas, Bartolome. Historia de las Indias, Vol 3, (Mexico City: Fondo Cultura Economica, 1951) chapter 29.

7. Bodley, John H, Cultural Anthropology: Tribes, States and the Global System. Mayfield, Mountain View, California, 2000.

8. Mumford, Lewis. Technics and Human Development, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, New York, 1966, page 186.

9. Diamond, Stanley, In Search of the Primitive: A Critique of Civilization, Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick, 1993, page 1.

Photo by Henry Chen on Unsplash

by DGR News Service | Apr 17, 2016 | Colonialism & Conquest, Human Supremacy, Prostitution

Featured image: Mining in Seite Suyos, Bolivia. (Credit: Wikimedia Commons user Mach Marco)

By Derrick Jensen / Deep Green Resistance

When living the dream means others will die

I want to tell you three stories of winning and losing, of selfishness and sacrifice, of this culture.

Story one. Last spring I gave a talk in a small farming community in northwestern Illinois. I drove there from my previous talk in Wisconsin, passing through prime agricultural territory, which is to say cleared and plowed and empty cornfield after cleared and plowed and empty cornfield. When I got to my destination, a delightful retired teacher took me to see the last remaining unplowed prairie in the county. It was more or less downtown, between a busy street and yet another field devoted to agriculture. As he led me across the slender tract, I couldn’t stop weeping at the sight of flowers who were once common and now barely hanging on, butterflies who were once common and now barely hanging on, a mother goose protecting her nest. My (human) host told me that even though this is the last six acres left—just six acres out of 360,000 in the county—the neighboring landowner refuses to stop applying insecticides and herbicides, which of course drift across the fenceline.

That evening, after he introduced me, I took the stage, sat down, and faced a roomful of members of this farming community. I thanked them for their hospitality, told them of my experiences of the previous twenty-four hours, then said, “I think the plow is the most destructive artifact humans have ever created. It destroys every living being on a piece of ground and converts that land to solely human use.”

The members of this farming community looked back at me. One gave a grim smile, then said, “Those plows paid for our houses.”

I nodded, smiled just as grimly, and responded, “That’s precisely the problem, isn’t it?”

Story two begins with me receiving an issue of my alumni magazine from the Colorado School of Mines, which featured an article titled “Hitting Paydirt.” The article tells stories of several “tremendously rewarding” discoveries. There’s a twenty-six-year-old CSM grad who discovered a “virgin deposit” of 2 million ounces of gold. Another grad discovered what became mines in environmentally ravaged Ireland; environmentally ravaged, war-torn, and rape-plagued Somalia; and environmentally ravaged, war-torn, rape-plagued, and slavery- and child-labor-infested Mauritania (the article, of course, only listed the countries, not their misfortunes, many of which are caused or exacerbated by resource extraction). But the story I want to focus on happened in Bolivia, where CSM grad Larry Buchanan, in the employ of a transnational mining corporation (with an address in the Cayman Islands for tax haven purposes, and having since that time gone through bankruptcy and changed its name, emerging as essentially the same company but without the debt), saw what seemed like a promising geological formation. He looked more closely, and found at the center of the deposit a village, complete with ancient stone church.

Buchanan describes it like this: “The silver deposit lay on the surface, mineralized ledges cropped out everywhere around and below a little indigenous village of rock, adobe and grass thatch, called San Cristobal. The cobblestone streets were paved with silver-bearing rock. The rock walls of the houses literally were laced with silver veins. You couldn’t take a step without touching silver. But somehow [sic] it had been overlooked [sic] by everyone [sic].”

He unintentionally answers his own question as to why these indigenous peoples had never put in an open pit mine: “The Quechua culture of southwestern Bolivia is one of multiple gods and spirits, one with a profound respect for the earth in general and curiously [sic], for rocks in particular. They believe rocks are their direct ancestors, living souls that speak, think, feel emotions, and have distinct personalities.”

Buchanan again: “We discovered nearly a half billion tonnes of those silver-plated ancestors of the Quechua. [Yes, he actually said that.] After a year of work, the engineers calculated it contained nearly a billion ounces of silver, enough ore to last seventeen years of intensive mining. The computer models proved it feasible: the profits would be more than enormous and the mine would become a money-machine. [Yes, he actually said that.] It was a company maker, a world-class discovery, a perfect setup.” The only thing in his way was “that poverty-stricken little village right on top of it. If we wanted to make a mine, San Cristobal had to go.”

But the village didn’t go down without a fight—between white people. Buchanan’s wife was against moving the village and forced Buchanan to sleep on the couch, only relenting when Buchanan agreed that they would move to the village for a while to bear witness to the destruction they were causing (or, to use his words, “the opportunities we were offering the people”). This strikes me as a classic example of the conservative/liberal one-two punch of oppression, with the conservative perceiving the oppression as good in itself, while the liberal bears witness to the oppression without doing much of anything to stop it. So Buchanan and his wife watched as people dug up bones from the village’s four-hundred-year-old cemetery to move to their new compound eleven kilometers away. Buchanan joined village elders as they crawled around the cemetery to beg forgiveness for disturbing the dead. He watched as bulldozers leveled the village in just four hours. It was all very difficult for him: “There were times I was literally brought to tears when I would contemplate what the people lost due to my discovery.”

What was once a living village where people resided with their ancestors in the walls, their gods all around them, is now a huge toxic hole in the ground. But it’s all good. Buchanan believes the people now live better lives in the compound; transnational corporations have made 70 billion dollars; and, best of all, Buchanan and his wife wrote a book about it all. “I came to learn life holds so much more of value than just a few billion dollars worth of silver,” he says. Having learned this valuable lesson, Buchanan moved on to other projects, and believes he has just recently discovered another billion-ounce deposit somewhere else.

Story three involves New Zealand tae kwon do athlete Logan Campbell, who funded his dream of reaching the Olympics through being a pimp. He made a lot of money providing women’s bodies for men to use. He even made a video to recruit women into working for him. The advertisement had lots of pretty pictures of women leaping for joy in fields, standing contemplatively on beaches, and sharing warm hugs with happy children. One female voice-over gushed, “When I was a little girl, I used to dream of a life of liberty.” Another asked, “Did you enjoy that? I sure did.” One said, “I’m living the dream.” And another said, “You deserve it.” The ad never did describe precisely what the “it” is that women deserve, but I think most of us would agree that most little girls don’t dream of economically coerced sexual relations with strangers not of their choosing, of years of post-traumatic stress disorder, of broken psyches and broken genitals and broken lives.

The point, really, is that Logan Campbell did get to live his dream. He went to the Olympics on the bodies of women, just like Buchanan’s “tremendously rewarding find” came at the expense of San Cristobal and its deities, and just as plows pay for houses at the expense of everyone else in the biological community. These are all dreams of fame, accomplishment, money, even what we consider necessities, like the way we feed ourselves and the way we financially accumulate. The problem is, all these dreams are someone else’s nightmare.

These stories are not merely what is wrong with this culture, they are the fundamental ethos of this culture: the fulfillment of personal, social, and cultural dreams at the expense of all others. No sane culture would in any way extol any of these stories. So long as these stories are seen as the fulfillment of dreams, where the subjugation of others is not seen as subjugating them but rather as helping them to “live the dream”; so long as this culture considers actions that lead to the destruction of ancient ways of life as “rewarding finds,” where your own murderous behavior is seen as “offering opportunities” for the victims; so long as we find it not only acceptable but right and just to convert the lives of others and the life-support system of the entire planet itself into fodder for us, there is little hope for life on this planet.

Originally published in the January/February 2013 issue of Orion

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Mar 21, 2016 | Strategy & Analysis

By Stephanie McMillan / One Struggle

This essay originally appeared in Idées Nouvelles Idées Prolétariennes. Featured artwork by Stephanie McMillan

Individualism is the ideology of competition, of capitalism. It consists of prioritizing one’s perceived immediate personal interests above collective interests, and being blind to the fact that one’s long-term personal interests actually correspond to the interests of the whole. This leads people to behave in ways that are detrimental to the collective, and ultimately to each individual as well.

Under capitalism, society does not meet the needs of the people, and we are structurally prevented from meeting our needs collectively. Capitalism’s engine is competition. There is competition between classes as well as within classes. Within the working class, the capitalist system pits each person (or family) against all others in a struggle for survival.

Humans are social animals who, before agriculture arose and society was divided into classes, lived in bands. Our species evolved with a natural tendency to cooperate. But when people living under capitalism attempt to express this tendency, they are sharply discouraged. For example, when strangers spontaneously assist one another after a disaster, they are quickly dispersed and ordered to leave this task to the state.

The capitalist class holds ideological hegemony (dominance and control) over the whole society. They exert constant pressure to shape our ideas, thoughts, and emotions in ways that serve them. Therefore, unless we make a conscious contrary effort, the ideologies that serve this dominant class are spontaneously felt as “normal” or “natural.”

Individualism is a powerful ideological weapon that the capitalist class (the bourgeoisie) uses to crush the subjectivity of the working class (the proletariat), and thus to prevent the potential liberation of the world from capitalist rule. Individualism is promoted and fortified by every possible cultural and economic means. We are indoctrinated from birth. Parents are compelled to teach their children to survive in the competitive framework (which they have no choice about living in) by “getting ahead,” to “look out for number one,” to put oneself in the best position possible (i.e., through education, or seeking a rich mate) to accumulate wealth for personal security.

Individualism is the ideology of the petit bourgeoisie (those who circulate capital by selling either services or goods, who tend to aspire to belong to the ruling class). It manifests itself as the striving for market power, for personal advancement, for comforts, for security and stability within the framework of the system. In contrast, proletarian ideology seeks to overturn the capitalist system and meet our needs collectively. But capitalism has been able to indoctrinate even members of the working class in petit bourgeois ways of thinking, to manipulate them into acting against their own interests, in ways that benefit capitalists instead.

Artwork by Stephanie McMillan

As proletarian militants, we are no less subject to ideological domination than anyone else. The difference is that we are consciously aware of it, to varying degrees, and thus we are able to combat it. In order to fight the system, we must fight its dominant ideologies at every level: in society as a whole, in our organizations, and in our own individual hearts and minds.

This is an active and constant process of struggle. It will continue even after the ruling class has been defeated politically— we are so deeply conditioned that it may take generations to uproot their poisonous ideas. Ultimately, it will require that we construct a society (an economy, in particular) that retains no structural or social mechanism for rewarding individualism.

We should not be ashamed to discover individualism in our own hearts, or shame others for manifesting it— it is inevitable in capitalist society. Instead, the way to fight it is to bring it to light, examine it in relation to our overall political goals, and then consciously reject it (over and over again, as it will constantly re-arise).

Ideological strength requires an underpinning of political unity; these advance together. The motive for struggle on the ideological front is not to serve some abstract morality, but to achieve a specific political goal.

Individualism is not the same as individuality. Combatting individualism does not mean that everyone must be identical (which is impossible anyway) or that anyone should suppress their own thoughts, desires, or particular characteristics. On the contrary, we must recognize the value of each individual as inherent, and at the same time as it relates to the collective. Each person has specific strengths to contribute to our common work, and these should be enhanced and supported. Our weaknesses should be shared so we can help each other overcome them. We appreciate diversity and differences among us, which contribute to a dynamic social/political life, increasing our range of possibilities in action and thought. (In fact, for any motion to occur at all, in a dialectical process, differences are required, by definition). In groups, as in any aspect of the natural world, diversity ensures resilience, flexibility, adaptability, and evolution.

In order to struggle against individualism, we must recognize its manifestations. In political organizations, there are many ways that this destructive ideology materializes. They include (not exclusively) these 12 common types:

1) Misplaced priorities. Nothing is as important and urgent as crushing capitalism. Nothing. Countless lives will continue to be destroyed until we accomplish this task. The future existence of all life on Earth is at risk as long as this system exists. Everything we do should be, in some way, in service to our cause. Of course our basic needs must be met, which beyond self-reproduction (subsisting) also include maintaining one’s health and balance (mental, emotional, physical, social and cultural). These should support and renew our capacity to contribute to revolution. Even if we eliminate frivolous activities from our lives, we still have to make difficult choices about how we spend our time, because the system keeps us very busy in our effort to survive and meet our responsibilities. (This overload is intentionally devised so we are too overwhelmed to resist). Therefore we have to constantly evaluate how much energy we give to particular activities, make correct choices even when they are painful, and order our lives in favor of the revolutionary struggle.

2) Competition among ourselves. This can involve using one’s experience, knowledge, accomplishments, abilities or personality to gain personal power or prestige, and to repress the collective will. Instead, we should all strive to strengthen our collective democratic functioning by assisting each comrade to express her/himself, to overcome weaknesses, build strength, and maximize participation. We should struggle among ourselves within a framework of overall unity, in order to discover the truth together, and not attempt to impose one’s own will over others (whether their disagreements are verbalized or silent), or monopolize any aspect of work. Individual power without collective power is useless and can never defeat our enemy.

3) A lack of commitment. In order to increase consumption of commodities, capitalist society obsessively pushes self-indulgence as an ideal. (“Because you’re worth it.”) It has created concepts of “comfort,” “fun” and “satisfaction” that correspond to their economic need for us to buy things. Whatever doesn’t please us in the moment, we are encouraged to abandon and replace. This leads to a market-based approach to life, including toward nature, love, spirituality, political work, and everything else. Unfortunately, political work is not comfortable, fun, and instantly gratifying in the ways that we are conditioned to desire. Instead it is challenging, complex, and requires immense persistence. When this fact is discovered, a common response is to abandon it.

4) Laziness. Some people believe they’ve performed a great deed by joining an organization and declaring support for the cause. They stop here, congratulating themselves and posting revolutionary quotations all over Facebook. But this is like confusing the starting point in a marathon with the finish line. We can’t stand on unearned laurels, but have to run the full distance: to do the hard work of constructing theory, defining a political line, and building organizations—pushing ourselves through to victory and beyond.

5) Passivity. Letting others always take the lead, and refusing to take initiative (once a collective approach has been decided) is an avoidance of responsibility. Each person should strive to participate and contribute to the maximum of her/his potential, to express ideas without fear, and be willing to do whatever work is necessary.

6) Hero/martyr complex. While it’s essential to work to one’s maximum capacity and strive to increase it, it can be tempting to overestimate what one’s capacity actually is. A juggler with too many eggs will drop some of them. Similarly, taking on too many tasks and making too many commitments will result in failure to carry all of them out. Unreliability leads to uncertainty and paralysis for the other members of an organization, who have interconnected tasks that depend on one another for success. In addition, it could cause the person to burn out, rendering them totally ineffective. Instead of attempting personally to handle every task, we should help others share responsibilities. We have to accept that some tasks will not be accomplished (as well or at all) until sufficient collective capacity is built.

7) Defensive/aggressive ego. In a collective endeavor, criticism should never be personal; thus there is no reason to be personally offended by it. We should not only be willing to listen to criticism with an open mind, but to welcome constructive criticism, and learn to evaluate our own work in the spirit of understanding our weaknesses in order to overcome them. Criticism of the work of a comrade or ally should always be offered in a constructive manner, with the intention of assisting their work. An alternative should be suggested along with it. We should not pick each other apart for every small mistake (which can be very demoralizing), but focus on fundamental issues.

8) Self-expression. Intellectuals (especially in academia) attempt to generate novel ideas for professional or “personal branding” purposes, rather than focusing on constructing theory to concretely assist class struggle. This is theory for theory’s sake, or intellectualism. This practice converts theory into just another commodity, a gift to our enemy. The way to combat this is to produce our ideas (in whatever form) collectively. For artists, the concept of “art for art’s sake” is a way to justify creating work without political or social content. This means squandering one’s creativity and skills by offering them for the benefit of the ruling class, instead of for the working class. Intellectuals and artists should participate in other areas of political work, or they won’t fully understand their subjects.

9) Self-esteem. Working hard is good, but not so good if there is an underlying motive of elevating one’s own social position or being the center of attention. We do not need to build our self-esteem by seeking admiration, praise and flattery. Our self-respect and sense of connection should come from being an effective social agent for our class, connected to countless others within a historical process. We should appreciate one another as comrades, and let each other know when we’re doing good work, but not be motivated by a desire for public recognition.

10) Friend sourcing. Because of the atomization of our society, and consequent feelings of isolation, sometimes people join and use organizations as a means to alleviate loneliness, to make friends or develop relationships, whereas it should be the other way around: allowing friendships to arise from a foundation of political unity. If the personal aspect of a relationship is made primary over the political aspect, this can interfere with political functioning. Political agreement or disagreement can be falsely based on emotion. Underlying conflicts can manifest as personal attacks hidden under the guise of political disagreements, picking quarrels, harassment, or avoidance of common work because of discomfort. This creates a negative atmosphere which can sidetrack people’s attention and undermine group cohesion. There is no room for drama in political organizations. We should focus on our overall goal, and be good comrades first, friends second.

11) Liberalism. Tolerating destructive behavior because one doesn’t like conflict or want to “rock the boat,” allows that behavior to continue and increase. Manifestations of liberalism include gossiping behind people’s backs instead of bringing up problems collectively, failing to take opportunities to assert revolutionary ideas in appropriate situations, witnessing (or being subject to) oppressive acts or speech without saying anything, failing to hold comrades accountable, supporting or attacking views based on feelings about the person expressing them, and tolerating mediocrity in our work. These all result in an unprincipled peace that can lead to group apathy.

12) Going off the rails. The members of a revolutionary organization act only within the framework of political unity. Strength comes from disciplined collectivity, and individual initiative must be based on this foundation. Taking action as an individual in ways that have no relationship to collectively agreed-upon strategy or goals can be dangerous. For example, committing an illegal act (impulsively or from a concealed plan) without the knowledge and agreement of the collective, puts others at risk, damages collective work, and destroys mutual trust. Failing to take the safety of the organization seriously and to abide by its security protocols is inexcusable.

Everything in capitalist society is geared to stop us from organizing to fight for revolution. We feel constant pressure to cave in to individualism. We are tempted with possibilities for self-advancement if we abandon the struggle, or are threatened with the opposite if we don’t fall in line. If we insist on rejecting individualism, this can cost us our jobs. Friends may tell us we’re crazy, boring, or depressing to talk to. Our family members might tell us that we are failing in our responsibilities to them when we devote time to political work. On TV and in movies, we are given poisonous models of human behavior.

Resisting all these influences is class struggle on the ideological front. We have to keep our bearings, pick our battles wisely, and refuse to kneel down under pressure. In our organizations, we must assist one another to overcome individualism and all enemy influences.

Artwork by Stephanie McMillan

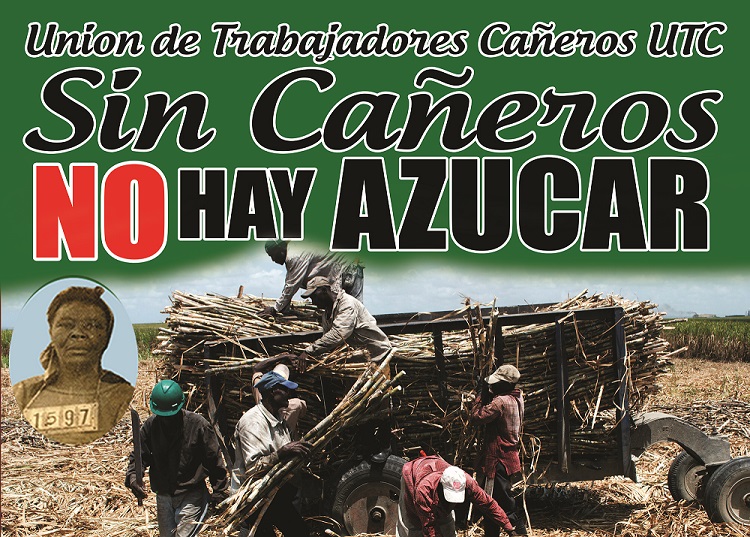

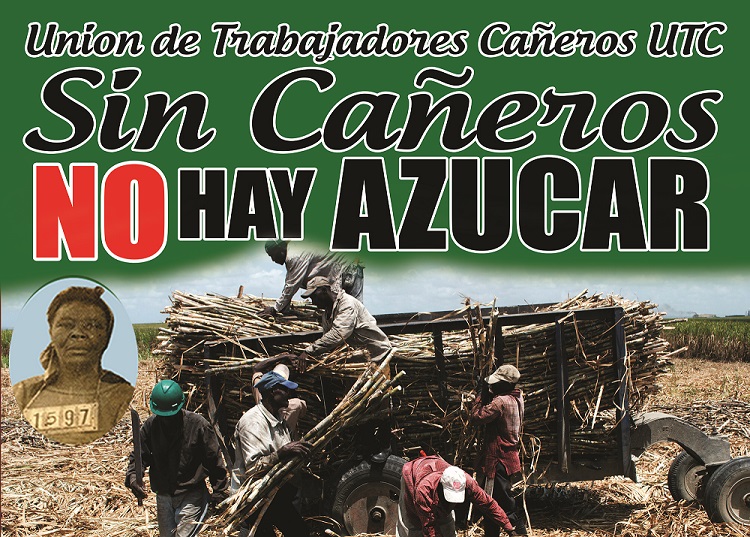

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Dec 17, 2015 | Worker Exploitation, Worker Solidarity

By One Struggle

On what I earn, I can’t afford shoes… We are poor, poor, poor. There are days we go to bed without food. – Batey worker from the film, “The Price of Sugar”

In the sugar plantations or bateyes of Dominican Republic, cane cutters often work barefoot. They can’t afford shoes. They can barely afford food, for that matter, despite the fact that they often work a minimum of 12 hours a day, doing the back-breaking work of cutting sugar cane by hand.

On the other side of the border that divides Hispaniola, Haitian garment workers in Port Au Prince recently blockaded a Korean factory because of bounced paychecks. For years, Haitian garment workers have been fighting wage theft and to be paid the inadequate legal minimum wage – still not enough to live off of.

Whatever the product is – the pair of pants, the t-shirt – we are the ones producing it. We labor hard, and don’t get paid. – Haitian garment worker of SOTA in Port Au Prince

This week Unión De Trabajadores Cañeros De Los Bateyes (Union of the Bateyes of Sugarcane Workers) and Sendika Ouvriye Takstil ak Abiman (SOTA) (Union of Textile and Garment Workers) will meet to discuss their common struggles against exploitation.

Specifically, they are meeting about recent actions of the DR government to strip people of Haitian descent of their citizenship. This has mostly affected the poor – cane cutters, street vendors, and service laborers. In bringing attention and their perspective to this struggle, the groups’ intentions are to put down false divisions of racism and nationalism, with the goal of working together against their common enemy – the Haitian and Dominican ruling classes.

SOTA is affiliated with the autonomous workers’ organization, Batay Ouvriye (BO) (Workers Fight), which will host a series of meetings, a press conference, and direct action in Port Au Prince.

According to one of the event organizers, “They will be three Haitian cane workers, one Dominican cane worker and the coordinator of the union. The presence of the Dominican cane worker is to deny the nationalist option and to put the class situation in concrete relief, in contrast to the bourgeois organizations here who pretend to defend their ‘compatriots.’”

There is a long history of animosity between Haiti and Dominican Republic. Both nationalism and racism are deep rooted. The DR won its independence, not from European colonialists, but from Haiti. Since then, Haitians living in the DR have faced discrimination, and thousands of Haitians and Dominicans of Haitian descent were massacred under Dominican dictator, Rafael Trujillo.

In 2013, the Dominican Supreme Court retroactively withdrew citizenship from anyone born in the DR to undocumented immigrants, with the provision that persons who submitted the proper documentation could apply for legal residency. The deadline for this application was summer 2015. However, many who submitted this paperwork, along with hundreds of dollars in fees, never received any notice or proper documentation from the government. Thousands of Haitians and Dominicans of Haitian descent left the DR, or were rounded up and dropped at the Haitian/Dominican border, often without being able to gather their belongings or to alert their families.

So now, there are hundreds of thousands of people rendered stateless, living in temporary shanty-towns along the border. They’ve been told that if they get documentation proving their country of origin from the Haitian government, then they can apply for Dominican citizenship or work visas. In fact, the Haitian government was paid by the Dominican government to facilitate this process, but Haitians living in limbo on the border have seen no results from this transaction.

Another issue affecting cane workers and low-wage laborers is that for years many paid into social security in the DR. Once they stopped working, they apply for their pensions, submitting the required paperwork to DR government and received nothing. Or, if they’ve been deported, they have no means of claiming their pension either.

This situation is not just about racism or nationalism. It is an issue of the ruling classes of both countries exploiting and stealing from the poor and working class. This summer, many demonstrations were held, especially in New York and Miami, with calls for travel boycotts against the DR and urgent appeals to avert a humanitarian crisis. Most of these demands have been voiced from people outside of the DR/Haiti, or removed from the exploitation of the bateyes and the temporary shanty-towns.

The aim with this series of meetings between workers from both countries is to bring attention to calls and demands led by the workers and people directly affected by these struggles. These are the people whose demands should be amplified, and calls for action should be followed.

Here in the U.S. we use Dominican sugar in our coffee every day. Our clothing is made in sweatshops, often sewn in Haiti (thanks to HELP and HOPE Acts). Capitalism and imperialism give us no choice, no say in how goods are produced. Our sugar and our clothing are the results of wage theft and a politic of misery for the working class in dominated countries. Boycotts and conscious consumerism pretend that with our purchasing, exploitation can be ameliorated. In reality, it is merely shifted to another part of the world. We need to understand the dynamics of capitalism/imperialism, its inherent exploitation, and we must address these issues from the interests of the working class. Who better to lead this effort than the workers themselves?

Read more at One Struggle

by DGR Editor | Sep 27, 2015 | Agriculture, Indigenous Autonomy

by Kim Hill, Deep Green Resistance Australia

Why did the Australian aborigines never develop agriculture?

This question was posed in the process of designing an indigenous food garden, and I could hear the underlying assumptions of the enquirer in his tone. Our culture teaches that agriculture is a more desirable way to live than hunting and gathering, and agriculturalist is more intelligent and more highly evolved than a hunter gatherer.

These assumptions can only be made by someone indoctrinated by civilization. It’s a limited way to look at the world.

I was annoyed by question, and judged the person asking it as ignorant of history and other cultures, and unimaginative. Since many would fit this label, I figured I’m better off answering the question.

This only takes some basic logic and imagination, I have no background in anthropology or whatever it is that would qualify someone to claim authority on this subject. You could probably formulate an explanation by asking yourself: How and why would anyone develop agriculture?

First consider the practicalities of a transition from hunting and gathering to agriculture.

What plants would be domesticated? What animals? What tools would they use? How would they irrigate?

Why would anyone bother domesticating anything that is plentiful in the wild?

To domesticate a plant takes many generations (plant generations, and human generations) of selecting the strongest specimens, propagating them in one place, caring for them, protecting them from animals and people, from the rain and wind and sun, keeping the seeds safe. This would be incredibly difficult to do, it would take a lot of dedication, not just from one person but a whole tribe for generations. If your lifestyle is nomadic, because food is available in different places in different seasons, there is no reason to make the effort to domesticate a plant.

Agriculture is high-risk. There are a lot of things that could destroy a whole crop, and your whole food supply for the year, as well as your seed stock for the next. A storm, flood, fire, plague of insects, browsing mammals, neighbouring tribes, lack of rain, disease, and no doubt many other factors. A huge amount of work is invested in something that is likely to fail, which would then cause a whole community to starve, if there isn’t a back-up of plentiful food in the wild.

Agriculture is insecure. People in agricultural societies live in fear of crop failure, as this is their only source of food. The crops must be defended. The tools, food storage, water supply and houses must also be defended, and maintained. Defended from people, animals, and insects. Growing and storing all your food in one place would attract all of these. Defence requires weapons, and work.

Agriculture requires settlement. The tribe must stay in one place. They cannot leave, even briefly, as there is constant maintenance and defending to do. Settlements then need their own infrastructure: toilets, water supply, houses, trading routes as not all the food needs can be met from within the settlement. Diseases spread in settled areas.

Aboriginal people travel often, and for long periods of time. Agriculture is not compatible with this way of life.

Agriculture is a lot of work. The farmers must check on the crop regularly, destroy diseased plants, remove weeds, irrigate, replant, harvest, save seeds, and store the crop. Crops generally are harvested for only a few weeks or months in the year, and if they are a staple, must be stored safely and be accessible for the rest of the year.

Domesticated animals require fencing, or tethering, or taming. They would be selectively bred for docility, which is a weakness not a strength, so a domesticated animal would be less healthy than a wild animal.

The people too become domesticated and lose strength with the introduction of agriculture. The wild intelligence needed to hunt and gather would be lost, as would the relationships with the land and other beings.

Agriculture requires a belief in personal property, boundaries, and land ownership. Australian aborigines knew that the land owned the people, not the other way around, so would never have treated the land in this way.

Agriculture needs a social hierarchy, where some people must work for others, who have more power by having more wealth. The landowner would have the power to supply or withhold food. Living as tribal groups, aborigines probably wouldn’t have desired this social structure.

Cultivated food has less nutrition than wild food. Agriculturalists limit their diet to plants and animals that can easily be domesticated, so lose the diversity of tastes and nutrients that make for an ideal human diet. Fenced or caged animals can only eat what is fed to them, rather than forage on a variety of foods, according to their nutritional needs. Domesticated plants only access the nutrients from the soil in the field, which becomes more depleted with every season’s crop. Irrigation causes plants to not send out long roots to find water, so domesticated plants are weaker than wild plants.

Agriculture suggests a belief that the world is not good enough as it is, and humans need to change it. A land populated with gods, spirits or ancestors may not want to be damaged, dug, ploughed and irrigated.

Another thought is that agriculture may develop from a belief in scarcity – that there is not enough food and it is a resource that needs to be secured. Indigenous belief systems value food plants and animals as kin to be in relationship with, rather than resources to exploit.

Agriculture isn’t an all-or-nothing thing. Indigenous tribes engage with the landscape in ways that encourage growth of food plants. People gather seeds of food plants and scatter them in places they are likely to grow. Streams are diverted to encourage plant growth. Early explorers witnessed aboriginal groups planting and irrigating wild rice. Tribes in North Queensland were in contact with Torres Strait Islanders who practiced gardening, but chose not to take this up on a large scale themselves.

A few paragraphs from Tim Low’s Wild Food Plants of Australia:

The evidence from the Torres Strait begs the question of why aborigines did not adopt agriculture. Why should they? The farming life can be one of dull routine, a monotonous grind of back-breaking labour as new fields are cleared, weeds pulled and earth upturned. The farmer’s diet is usually less varied, and not always reliable, and the risk of infectious disease is higher…It is not surprising that throughout the world many cultures spurned agriculture.

Explorer Major Mitchell wrote in 1848: ‘Such health and exemption from disease; such intensity of existence, in short, must be far beyond the enjoyments of civilized men, with all that art can do for them; and the proof of this is to be found in the failure of all attempts to persuade these free denizens of uncivilized earth to forsake it for tilled soil.’

After all this, I’m amazed that anyone ever developed agriculture. The question of why Australian aborigines never developed agriculture is easily answered and not as interesting as the question it brings up for me: why did twentieth century westerners never develop hunter-gatherer lifestyles?

From Stories of Creative Ecology January 5, 2013