![Decade Long Gag Order for Speaking Out [Press Release]](https://dgrnewsservice.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2023/06/kilian-karger-CTkLczb9HeA-unsplash-1080x675.jpg)

by DGR News Service | Jun 26, 2023 | NEWS, Repression at Home, Toxification

Editor’s Note: This press release from CELDF (Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund) describes a gag order put against an activist, Tish O’Dell, for talking about her concerns on the use of an industrial byproduct in her community. The gag order was placed in 2012. Since then, tests have affirmed that not only was the product toxic, it is also high in radioactive elements. Lawsuits by big corporations against activists are one of the tools used to shut down any form of resistance. We have talked about it also in the context of the lawsuit against activists and tribal members involved in protecting Thacker Pass. After a decade during which new research has been conducted, Tish O’Dell has appealed for a termination on the gag order.

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

June 19, 2023

Contact:

Terry Lodge, Attorney CELDF

419-205-7084

tjlodge50@yahoo.com

Tish O’Dell

tish@celdf.org

440-552-6774

OHIO, Cuyahoga County – On Friday, June 16, a motion was filed in the Cuyahoga Court of Common Pleas for relief from judgment for Tish O’Dell to terminate the permanent injunction from a Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation (SLAPP) filed against her in March 2012 by Duck Creek Energy which claimed defamation and loss of business profits.

O’Dell had been active at the time, educating both her community, elected leaders and neighbors about the harmful effects of urban oil/gas drilling happening in her community of Broadview Heights and surrounding communities by sending emails, posting information online and attending community meetings. In the process, she had learned of Duck Creek Energy’s road de-icer, AquaSalina, which according to Duck Creek Energy President, Dave Mansbery, was a byproduct of oil/gas drilling. O’Dell’s concern increased upon learning, from test results reported to the Ohio Department of Natural Resources (ODNR), about the high levels of substances like benzene, toluene and ethylbenzene contained within the supposedly harmless de-icer. These substances are known to be carcinogenic. She also continued to conduct more research on ODNR’s website and in other places in order to inform herself and educate others as to what takes place during the drilling process and fracking.

“When I learned that AquaSalina was being used on my community’s streets as well as in neighboring communities, I wanted to inform people about what I had learned,” said O’Dell. “I felt people needed to know what was being spread on the roads that they, their kids, and their pets were walking on. And common sense indicated to me that what is spread on our streets gets into our air and our lawns and goes down street drains to water supplies. I knew the oil/gas industry was powerful, but I also believed in my right and everyone’s right to free speech and the right to question the government and their decisions. I had never heard of a SLAPP lawsuit until there was a knock at my front door and the person asked if I was Tish O’Dell and told me ‘You’ve been served’.”

After a year of court filings, depositions, and much pressure directed against O’Dell’s inclination to go to trial, a settlement was signed in the fall of 2013. Part of the settlement involved granting a permanent injunction, an extraordinary remedy in a defamation case, against O’Dell, prohibiting her from using certain words to describe the product AquaSalina. During this time Mansbery began bottling and selling the product on store shelves in local hardware stores and even at several Lowe’s locations in Ohio. This afforded activists and scientists the opportunity to purchase the product and begin testing it. And in the decade since, there has been much research and testing of the product by the state agency ODNR, universities, Rolling Stone Magazine and other publications. The tests affirmed that not only was the product chemically toxic, it is also high in radioactive elements, Radium 226 and 228. In October 2021 the Ohio Department of Transportation stopped using AquaSalina in part because of the environmental concerns.

Because these recent test results and scientific research papers didn’t exist in 2012, O’Dell is filing this motion to dissolve the court order so she can again speak freely and warn people about the dangers of this product to both humans and nature. There have been several attempts over the past few years to pass a law at the state level which would make a commodity out of this drilling byproduct. And with the state opening up leasing of park land for fracking this year, there will be more brine produced.

“SLAPP suits are just another tool used by industry and corporations to silence and intimidate those who speak out against them and their activities,” stated Wyatt Sugrue, Chicago attorney. “The goal is not only to silence journalists, individuals and organizations, but to also make others afraid to speak up. In recent years there have been high profile cases of SLAPP suits against John Oliver and HBO, Mother Jones Magazine and recently Texas Gubernatorial candidate Beto O’Rourke who was served with a SLAPP by the CEO of Energy Transfer Partners, Kelcy Warren.”

As stated in the motion:

The Ohio court system has in essence allowed a limited-purpose public figure, Duck Creek Energy, to immunize itself from public scrutiny, and the court system is acting as the personal police force for the company to stop such scrutiny.

“What I have learned over the past decade is how our system, controlled by an elite minority, is quashing the people’s constitutional rights. I witnessed this first hand working with so many great people across the state who were also attempting to protect their own communities and nature. They inspired me to do this,” stated O’Dell. “I can’t just tell others to stand up for their rights and what they believe in and to have courage even when it seems scary, and not practice what I preach.”

A recent article by EarthJustice, September 2022, sums it up, “We aspire for the courts to be an institution that upholds the rights of all, however, SLAPP suits are a way for the rich and powerful to abuse the court system and turn it into a tool that silences individuals and organizations. SLAPP suits disguise themselves as legitimate lawsuits, and while most end up being dismissed, their real goal is quashing legitimate dissent and protest in the process. Protesting is one of the cornerstones of our democracy, a right so important in the early days of our country that it is explicitly included in the first amendment. One thing is clear. Our courts must uphold this right for everyone and cannot become tools for the rich and powerful to abuse power and limit the ability of all of us to seek justice and speak out against issues impacting our communities.”

In the O’Rourke SLAPP, it has been discovered that Warren, the plaintiff, has also made campaign contributions to six of the nine Texas Supreme Court Justices that could ultimately hear the case.

According to CELDF Attorney Terry Lodge, “Ending the gag order on Tish O’Dell is important to our work as an organization. CELDF works with community members and activists throughout the state and country to assert their constitutional and democratic rights to expose harms and stand up for protecting the community and nature. If the wealthy and powerful can file lawsuits to silence their voices, those must always be opposed.”

Photo by Kilian Karger on Unsplash

by DGR News Service | Jun 23, 2023 | ACTION, Obstruction & Occupation

Editor’s Note: In order to deter the tribal members and activists from fighting for Thacker Pass, Lithium Nevada has sued them. Unsurprisingly, as a corporation, they have greater funds to sustain their legal action. We appeal for all who can to support in whatever way you can. The details for financial donations are at the end of the post.

Lithium Nevada Corporation has filed a lawsuit against Protect Thacker Pass and seven people for opposing the Thacker Pass lithium mine.

The lawsuit is similar to what is called a “Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation,” or SLAPP suit, aimed at shutting down free speech and protest. The suit aims to ban the prayerful land defenders from the area and force them to pay monetary damages which could total millions of dollars.

“This lawsuit is targeting Native Americans and their allies for a non-violent prayer to protect the 1865 Thacker Pass massacre site,” said Terry Lodge, attorney working with the group. “These people took a moral stand in the form of civil disobedience. They are being unjustly targeted with sweeping charges that have little relationship to the truth, and we will vigorously defend them.”

The lawsuit targets Dean Barlese, respected elder and spiritual leader from the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe, Dorece Sam from the Fort McDermitt Paiute-Shoshone Tribe, Bhie-Cie Zahn-Nahtzu (Te-Moak Shoshone and Washoe), Bethany Sam from the Standing Rock Sioux and Kutzadika’a Paiute Tribes, Founding Director of Community Rights US Paul Cienfuegos, and Max Wilbert and Will Falk of Protect Thacker Pass, which is also named in the suit.

They are charged with Civil Conspiracy, Nuisance, Trespass, Tortious Interference with Contractual Relations, Tortious Interference with Prospective Economic Advantage, and Unjust Enrichment.

As part of the lawsuit, Lithium Nevada has been granted a Temporary Restraining Order which restricts the defendants and “any third party acting in concert” with them from interfering with construction, blocking access roads, or even being in the area. The accused parties are not involved in planning further protest activity at the mine site.

Regardless, these allegations are alarming to the Great Basin Native American communities who believe their religious practices are protected by the American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978. The lawsuit’s language places fear in the hearts of Native American people who want to pray and visit their ancestors’ gravesites.

The case references instances of non-violent prayer and protest that took place on April 25th, and a prayer camp named after Ox Sam (survivor of the 1865 massacre and ancestor of Dorece Sam and Dean Barlese) which was established at Thacker Pass on May 11th. On June 8th, that camp was raided and dismantled by police. One young indigenous woman was arrested and transported to jail inside a pitch-black box. In the aftermath of the raid, a ceremonial fire was extinguished, sacred objects were put in trash bags, and tipi poles were broken.

The American Indian Religious Freedom Act states that it is “the policy of the United States to protect and preserve for American Indians their inherent right of freedom to believe, express, and exercise the traditional religion of the American Indian…including…access to sites.”

Dorece Sam, President of the Native American Church of the State of Nevada:

“I take my grandkids to Peehee Mu’huh to teach them to pray for our unburied ancestors whose remains are scattered there, to collect our holy plants, to hunt and fish, and to collect medicinal herbs. The ancestors who were killed at Thacker Pass have never been given the proper prayers for their spirits. Lithium Nevada is desecrating our unceded lands and our ancestors’ resting places.”

Dean Barlese, respected elder and spiritual leader from the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe:

“The Indian wars are continuing in 2023, right here. America and the corporations who control it should have finished off the ethnic genocide, because we’re still here. My great-great-grandfather fought for this land in the Snake War and we will continue to defend the sacred. Lithium Nevada is a greedy corporation telling green lies.”

Bethany Sam:

“Our people couldn’t return to Thacker Pass for fear of being killed in 1865, and now in 2023 we can’t return or we’ll be arrested. Meanwhile, bulldozers are digging our ancestors graves up. This is what Indigenous peoples continue to endure. That’s why I stood in prayer with our elders leading the way.”

Bhie-Cie Zahn-Nahtzu:

“Lithium Nevada is a greedy corporation on the wrong side of history when it comes to environmental racism and desecration of sacred sites. It’s ironic to me that I’m the trespasser because I want to see my ancestral land preserved.”

Paul Cienfuegos:

“Virtually every single accusation against us is a lie, and of course the corporation’s leaders know this. But our actions have scared them, so they are lashing out against classic nonviolent direct-action tactics. And this is yet another prime example of why we need to dismantle the structures of law that grant so many so-called constitutional ‘rights’ to business corporations, like access to the courts.”

Max Wilbert, Protect Thacker Pass:

“Around the world, a land defender is killed every two days. Murdering activists is hard to get away with in the United States, so corporations do this instead. This lawsuit is aimed at destroying the lives of people non-violently defending the land. But we’re not giving up. There are millions of people opposing this mine, and this fight will continue.”

Will Falk:

“I’ve been involved in directly petitioning the courts for two years to enforce tribal rights to consultation without success. Now Paiutes and Shoshones are being sued for peacefully defending the final resting places of their massacred ancestors. Lithium Nevada is just another mining corporation bullying Native Americans once again. This pattern has got to stop.”

Lithium Nevada corporation has been locked in legal battles since 2021, when four environmental groups, a local rancher, and several tribes sued the Federal Government to attempt to overturn the permits for the mine. The suits allege failures of consultation, violation of endangered species law and water laws, and dozens of other infractions. The most recent filing in an ongoing Federal Court case brought by three local tribes was filed on Friday, arguing that Lithium Nevada needs to halt construction while it consults with tribes about the Thacker Pass massacre sites. The 9th Circuit Court of Appeals in California will hear oral arguments in other cases later this month.

The news comes as Lithium Nevada’s parent corporation, Lithium Americas, has been implicated in four alleged human rights violations and environmental crimes related to their lithium mining operation in Cauchari-Oloroz, Argentina.

The defendants are seeking attorneys to join the legal defense team, and monetary donations to their legal defense fund. You can donate via credit or debit card, PayPal (please include a note that your donation is for Thacker Pass legal defense), or by check.

by DGR News Service | Jun 16, 2023 | Colonialism & Conquest, Mining & Drilling, NEWS, Obstruction & Occupation, Repression at Home

Editor’s Note: The following are two press releases by Ox Sam Camp. As communities get more radical against corporations, corporations use their power against them. This is not the first time that this has happened and it will not be the last. As activists, it is necessary for us to understand the risk associated with any action against the system. The earlier we understand this, the better we can strategize.

The article is followed by a short reflection piece by Elisabeth Robson on the need for the environmental movement to put our allegiance with the natural world, as is demonstrated in this fight to protect Thacker Pass.

Ox Sam Camp Raided by Police at Thacker Pass

One Arrested as Prayer Tipis Are Dismantled and Ceremonial Items Confiscated

6/8/23

Contact: Ox Sam Camp

OxSam.org

THACKER PASS, NV — On Wednesday morning, the Humboldt County Sheriff’s department on behalf of Lithium Nevada Corporation, raided the Ox Sam Newe Momokonee Nokutun (Ox Sam Indigenous Women’s Camp), destroying the two ceremonial tipi lodges, mishandling and confiscating ceremonial instruments and objects, and extinguishing the sacred fire that has been lit since May 11th when the Paiute/Shoshone Grandma-led prayer action began.

One arrest took place on Wednesday at the direction of Lithium Nevada security. During breakfast, law enforcement arrived. Almost immediately without warning, a young Diné female water protector was singled out by Lithium Nevada security and arrested, not given the option to leave the camp. Two non-natives were allowed to “move” in order to avoid arrest. The Diné woman was quickly handcuffed and subsequently loaded into a sheriff’s SUV for transport to Winnemucca for processing.

While on the highway, again without warning or explanation, she was transferred into a windowless, pitch-black holding box in the back of a pickup truck. “I was really scared for my life,” the woman said. “I didn’t know where I was or where I was going. I know that MMIW is a real thing, and I didn’t want to be the next one.” She was transported to Humboldt County Jail, where she was charged with criminal trespass and resisting arrest, then released on bail.

Just hours before the raid, Ox Sam water protectors could be seen for the second time this week bravely standing in the way of large excavation equipment and shutting down construction at the base of Sentinel Rock.

To many Paiute and Shoshone, Sentinel Rock is a “center of the universe,” integral to many Nevada Tribes’ way of life and ceremony, as well as a site for traditional medicines, tools, and food supply for thousands of years. Thacker Pass is also the site of two massacres of Paiute and Shoshone people. The remains of the massacred ancestors have remained unidentified and unburied since 1865, and are now being bulldozed and crushed by Lithium Nevada for the mineral known as “the new white gold.”

Since May 11th, despite numerous requests by Lithium Nevada workers, the Humboldt County Sheriff Department has been reticent and even unwilling to arrest members of the prayer camp, even after issuing three warnings for blocking Pole Creek Road access to Lithium Nevada workers and sub-contractors, while allowing the public to pass through.

“We absolutely respect your guys’ right to peacefully protest,” explained Humboldt County Sheriff Sean Wilkin on May 12th. “We have zero issues with [the tipi] whatsoever… We respect your right to be out here.”

On March 19th the Sheriff arrived again, serving individual fourteen-day Temporary Protection Orders against several individuals at camp. The protection orders were granted by the Humboldt County Court on behalf of Lithium Nevada based on sworn statements loaded with misrepresentations, false claims, and, according to those targeted, outright false accusations by their employees. Still, Ox Sam Camp continued for another week. The tipis, the sacred fire, and the prayers remained unchallenged for a total of twenty-seven days of ceremony and resistance.

The scene at Thacker Pass this week looked like Standing Rock, Line 3, or Oak Flat. As Lithium Nevada’s workers and heavy equipment tried to bulldoze and trench their way through the ceremonial grounds surrounding the tipi at Sentinel Rock, the water protectors put their bodies in the way of the destruction, forcing work stoppage on two occasions.

Lithium Nevada’s ownership and control of Thacker Pass only exists because of the flawed permitting and questionable administrative approvals issued by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). BLM officials have refused to acknowledge that Peehee Mu’huh is a sacred site to regional Tribal Nations and have continued to downplay and question the significance of the double massacre through two years of court battles.

Three tribes — the Reno-Sparks Indian Colony, Summit Lake Paiute Tribe, and Burns Paiute Tribe — remain locked in litigation with the Federal Government, challenging the BLM’s permit process from the beginning. The tribes filed their latest response to the BLM’s Motion to Dismiss on Monday. BLM is part of the Department of the Interior, which is led by Deb Haaland (Laguna Pueblo).

On Wednesday, at least five Sheriff’s vehicles, several Lithium Nevada worker vehicles, and two security trucks arrived at the original tipi site that contained the ceremonial fire, immediately adjacent to Pole Creek Road. The one native water protector was arrested without warning, while others were issued with trespass warnings and allowed to leave the area. Once the main camp was secured, law enforcement then moved up to secure and dismantle the tipi site at Sentinel Rock, a mile away.

There is a proper way to take down a tipi and ceremonial camp, and then there is the way Humboldt County Sheriffs proceeded on behalf of Lithium Nevada Corporation. Tipis were knocked down, tipi poles were snapped, and ceremonial objects and instruments were rummaged through, mishandled, and impounded. Empty tents were approached and secured in classic SWAT-raid fashion. One car was towed. As is often the case when lost profits lead to government assaults on peaceful water protectors, Lithium Nevada Corporation and the Humboldt County Sheriffs have begun to claim that the raid was done for the safety of the camp members and for public health.

Josephine Dick (Fort McDermitt Paiute-Shoshone), who is a descendent of Ox Sam and one of the matriarchs of Ox Sam Newe Momokonee Nokutun, made the following statement in response to the raid:

“As Vice Chair of the Native American Indian Church of the State of Nevada, and as a Paiute-Shoshone Tribal Nation elder and member, I am requesting the immediate access to and release of my ceremonial instruments and objects, including my Eagle Feathers and staff which have held the prayers of my ancestors and now those of Ox Sam camp since the beginning. There was also a ceremonial hand drum and medicines such as cedar and tobacco, which are protected by the American Indian Religious Freedom Act.

In addition, my understanding is that Humboldt County Sherriff Department along with Lithium Nevada security desecrated two ceremonial tipi lodges, which include canvasses, poles, and ropes. The Ox Sam Newe Momokonee Nokutun has been conducting prayers and ceremony in these tipis, also protected by the American Indian Religious Freedom Act. When our ceremonial belongings are brought together around the sacred fire, this is our Church. Our Native American Church is a sacred ceremony. I am demanding the immediate access to our prayer site at Peehee Mu’huh and the return of our confiscated ceremonial objects.

The desecration that Humboldt County Sherriffs and Lithium Nevada conducted by knocking the tipis down and rummaging through sacred objects is equivalent to destroying a bible, breaking The Cross, knocking down a cathedral, disrespecting the sacrament, and denying deacons and pastors access to their places of worship. It is in direct violation of my American Indian Religious Freedom rights. This violation of access to our ceremonial church and the ground on which it sits is a violation of Presidential Executive Order 13007.

The location of the tipi lodge that was pushed over and destroyed is at the base of Sentinel Rock, a place our Paiute-Shoshone have been praying since time immemorial. After two years of our people explaining that Peehee Mu’huh is sacred, BLM Winnemucca finally acknowledged that Thacker Pass is a Traditional Cultural District, but they are still allowing it to be destroyed.”

Josephine and others plan to make a statement on live stream outside the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office in Winnemucca on the afternoon of Friday, June 9th around 1pm.

Another spiritual leader on the front lines has been Dean Barlese from the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe. Despite being confined to a wheelchair, Barlese led prayers at the site on April 25th which led to Lithium Nevada shutting down construction for a day, and returned on May 11th to pray over the new sacred fire as Ox Sam camp was established.

“This is not a protest, it’s a prayer,” said Barlese. “But they’re still scared of me. They’re scared of all of us elders, because they know we’re right and they’re wrong.”

Land Defenders Arrested, Camp Raided After Blocking Excavator

First arrests are underway and camp is being raided after land defenders halted an excavator this morning at Thacker Pass.

6/7/23

OROVADA, NV — This morning, a group of Native American water protectors and allies used their bodies to non-violently block construction of the controversial Thacker Pass lithium mine in Nevada, turning back bulldozers and heavy equipment.

The dramatic scene unfolded this morning as workers attempting to dig trenches near Sentinel Rock were turned back by land defenders who ran and put their bodies between heavy equipment and the land.

Now they are being arrested and camp is being raided.

Northern Paiute and Western Shoshone people consider Thacker Pass to be sacred. So when they learned that the area was slated to become the biggest open-pit lithium mine in North America, they filed lawsuits, organized rallies, spoke at regulatory hearings, and organized in the community. But despite all efforts over the last three years, construction of the mine began in March.

That’s what led Native American elders, friends and family, water protectors, and their allies to establish what they call a “prayer camp and ceremonial fire” at Thacker Pass on May 11th, when they setup a tipi at dawn blocking construction of a water pipeline for the mine. A second tipi was erected several days later two miles east, where Lithium Nevada’s construction is defacing Sentinel Rock, one of their most important sacred sites.

Sentinel Rock is integral to many Nevada Tribes’ worldview and ceremony. The area was the site of two massacres of Paiute and Shoshone people. The first was an inter-tribal conflict that gave the area it’s Paiute name: Peehee Mu’huh, or rotten moon. The second was a surprise attack by the US Cavalry on September 12th, 1865, during which the US Army slaughtered dozens. One of the only survivors of the attack was a man named Ox Sam. It is some of Ox Sam’s descendants, the Grandmas, that formed Ox Sam Newe Momokonee Nokotun (Indigenous Women’s Camp) to protect this sacred land for the unborn, to honor and protect the remains of their ancestors, and to conduct ceremonies. Water protectors have been on-site in prayer for nearly a month.

On Monday, Lithium Nevada Corporation also attempted to breach the space occupied by the water protectors. As workers maneuvered trenching equipment into a valley between the two tipis, water protectors approached the attempted work site and peacefully forced workers and their excavator to back up and leave the area. According to one anonymous land defender, Lithium Nevada’s action was “an attempted show of force to fully do away with our tipi and prayer camp around Sentinel Rock.”

Ranchers, recreationists, and members of the public have been allowed to pass without incident and water protectors maintain friendly relationships with locals. Opposition to the mine is widespread in the area, and despite repeated warnings from the local Sheriff, there have been no arrests. Four people, including Dorece Sam Antonio of the Fort McDermitt Paiute-Shoshone Tribe (an Ox sam descendant) and Max Wilbert of Protect Thacker Pass, have been targeted by court orders barring them from the area. They await a court hearing in Humboldt County Justice Court.

“Lithium Nevada is fencing around the sacred site Sentinel Rock to disrupt our access and yesterday was an escalation to justify removal of our peaceful prayer camps,” said one anonymous water protector at Ox Sam Camp. “Lithium Nevada intends to desecrate and bulldoze the remains of the ancestors here. We are calling out to all water protectors, land defenders, attorneys, human rights experts, and representatives of Tribal Nations to come and stand with us.”

“I’m being threatened with arrest for protecting the graves of my ancestors,” says Dorece Sam Antonio. “My great-great Grandfather Ox Sam was one of the survivors of the 1865 Thacker Pass massacre that took place here. His family was killed right here as they ran away from the U.S. Army. They were never buried. They’re still here. And now these bulldozers are tearing up this place.”

Another spiritual leader on the front lines has been Dean Barlese, a spiritual leader from the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe. Despite being confined to a wheelchair, Barlese led prayers at the site on April 25th (shutting down construction for a day) and returned on May 11th.

“I’m asking people to come to Peehee Mu’huh,” Barlese said. “We need more prayerful people. I’m here because I have connections to these places. My great-great-great grandfathers fought and shed blood in these lands. We’re defending the sacred. Water is sacred. Without water, there is no life. And one day, you’ll find out you can’t eat money.”

The 1865 Thacker Pass massacre is well documented in historical sources, books, newspapers, and oral histories. Despite the evidence but unsurprisingly, the Federal Government has not protected Thacker Pass or even slowed construction of the mine to allow for consultation to take place with Tribes. In late February, the Federal Government recognized tribal arguments that Thacker Pass is a “Traditional Cultural District” eligible for the National Register of Historic Places. But that didn’t stop construction from commencing.

“This is not a protest, it’s a prayer,” said Barlese. “But they’re still scared of me. They’re scared of all of us elders, because they know we’re right and they’re wrong.”

For more, go to Ox Sam Camp.

Hug Trees Not Pylons

By Elizabeth Robson

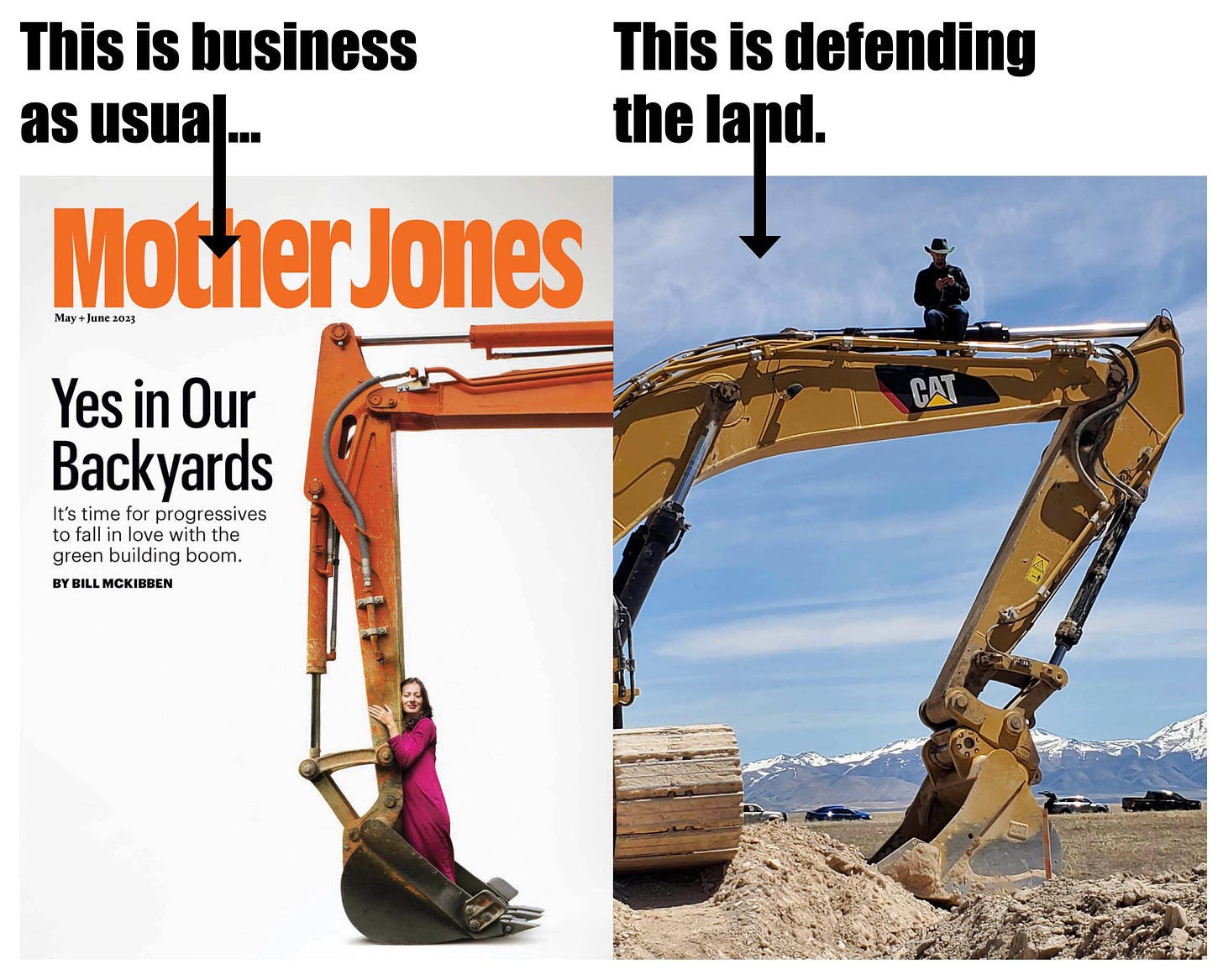

In the past couple of weeks both The Economist and Mother Jones have published covers showing people embracing industrial objects and exhorting “environmentalists” to get on board with the green building boom.

The Economist cover shows a man hugging a massive steel electric grid pylon and says “Hug Pylons Not Trees: The Growth Environmentalism Needs.” The Mother Jones cover shows a woman hugging an excavator, and says “Yes in Our Backyards: It’s time for progressives to fall in love with the green building boom.”

The latter is made even worse by the fact that it is Bill McKibben saying this. We expect relentless pro-industry, pro-growth propaganda from The Economist. But Mother Jones? Bill McKibben? McKibben begins his article in Mother Jones, Getting to Yes, by saying “I’m an environmentalist” and then proceeds to spend multiple pages telling us exactly how he is not an environmentalist but rather a pro-technology industrialist. To solve our “biggest problems” he pleads with us to “say yes” to “solar panels, wind turbines, and factories to make batteries and mines to extract lithium.”

Max Wilbert, co-founder of Protect Thacker Pass, climbed on top of an excavator on April 25, 2023 to protest the Thacker Pass Lithium Mine, currently being constructed in northern Nevada by Lithium Nevada Corporation. He was there with about 25 other people including Northern Paiute Native Americans Dorece Sam and Dean Barlese, who spent the day blocking mine construction and saying prayers to this land considered sacred by their people.

In Max’s book, Bright Green Lies, he describes “environmentalists” like McKibben as “bright greens”. These “environmentalists” understand that environmental problems exist and are serious, but believe that green technology and consumerism will allow us to continue our current lifestyles indefinitely. As Max writes: “The bright greens’ attitude amounts to: ‘It’s less about nature, and more about us.’”

In his Mother Jones article, McKibben illustrates how he’s less about nature, and all about us (meaning humans, our technologies, and our lifestyles). “Emergencies demand urgency,” he writes, and what he urges us is not to stop destroying nature, the source of all life on planet Earth, but rather to destroy more of it, by building more industry and mining more, for “electrons… a crop we badly need.”

McKibben acknowledges that “repeating the mistakes of our history” by building “a lithium mine on sacred territory in Nevada” is “truly unforgivable,” but then immediately dismisses the concerns of regional tribes by saying that “if we can’t make a quick energy transition, then the impact of that will be felt most by the poorest.” Does he not understand that for many traditional cultures and traditional spiritual practitioners, everywhere is sacred? Does he not understand that everywhere not already destroyed by industry is home to someone — sage-grouse, pronghorn, endangered spring snails, swallows, endangered trout, old growth sagebrush, and so many more? Apparently he does not, or perhaps he doesn’t care, because his article is all about promoting industry, nature be damned.

“So there’s one general rule you could derive: If something makes climate change worse, then we shouldn’t do it,” McKibben writes. I agree. Does McKibben think the 150,000 tons of CO2 the Thacker Pass lithium mine will emit per year don’t count? Clearly those emissions will make climate change worse. Does he think that the carbon emissions caused by digging up thousands of acres of ancient soil at Thacker Pass don’t count either? And what about the 700,000 tons per year of molten sulfur trucked into Thacker Pass from oil refineries; where will that molten sulfur come from if it doesn’t come from oil refineries, and do those oil refineries and their CO2 emissions not count? If we use McKibben’s rule, then clearly the Thacker Pass lithium mine should not be built, and yet he urges us to support more lithium mining.

McKibben and those pursuing the “electrify everything” agenda promoted by The Economist and Mother Jones are stuck in blinders about climate change. McKibben exposes these blinders when he writes: “slowing down lithium mining likely means extending the years we keep on mining coal.” He believes that this is our choice: lithium mining and batteries and electric vehicles, or coal and CO2 emissions. To him and the “electrify everything” crowd those are the only two options.

But there is another option: we can resist industrial culture and work to end it. We can block construction equipment rather than embracing it. We can dramatically lower our profligate energy use — no matter how it’s powered. We can protect the land and the natural communities, including human communities, that depend on unspoiled land, unpolluted soil, clean air, and clean water. We can be real environmentalists, deep green environmentalists, who understand that we must live within the limits of the natural world, and work to transform ourselves, our culture, our economy and our politics to put the health and well-being of the natural world first.

We can be more like Max and Dorece and Dean and the other activists who stood their ground to protect the land at Thacker Pass. We can block excavators, not hug them. Our very lives depend on it.

by DGR News Service | Jan 20, 2023 | ACTION, The Problem: Civilization

Editor’s Note: Even when local governing units make decisions for the welfare of the environment, state laws are designed to crush them. The following story covers how a small town is getting sued for passing a local ordinance to prevent pollution from factory farms. The basis of the lawsuit is that the ordinance is against the state law of Wisconsin. This story was originally published by Grist. You can subscribe to its weekly newsletter here.

This lawsuit is far from one of its kind. Similar lawsuits have been filed against a local government for trying to protect the environment against corporate interests. DGR News Service covered a series regarding the fight of Lake Eerie Bill of Rights in the state of Ohio. Read more about it here.

By John McCracken / Grist

The small community of Laketown, Wisconsin, home to just over 1,000 people and 18 lakes, is again at the center of a battle over how communities can regulate large, industrial farming operations in their backyards.

The town, which is half an hour from the Minnesota border, is the target of a lawsuit supported by the state’s largest business lobbying group, which claims the town board overstepped its role when it passed a local ordinance to prevent pollution from concentrated animal feeding operations, or CAFOs*.

Filed in Polk County Circuit Court in October, the lawsuit pits local farmers against the municipality, where decisions are made by a single town chair and two supervisors. Wisconsin Manufacturers & Commerce, or WMC, a lobbying group that defines itself as the state’s “largest and most influential business association” is representing the residents suing the town through its litigation center.

Early this year, WMC sent a letter to the town board that they would see legal action if the ordinance was not repealed. The notice of claim, sent in April, argues the town passed an ordinance with various illegal provisions under state law. The Wisconsin Manufacturers & Commerce Litigation Center, who have previously filed lawsuits to rollback state protections against water pollution, did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

“They see this ordinance, if not challenged, as something that may become more the norm around the state,” Adam Voskuil, staff attorney for the nonprofit law office Midwest Environmental Advocates, told Grist. This law office has issued its support for Laketown’s ordinance in the past but is not representing the municipality in this ongoing litigation.

As the agricultural industry increasingly forces farmers to “get big or get out,” CAFOs have become plentiful across Wisconsin and the country at large, with more and more animals living on CAFO operations in recent years. The size of these farms varies within a state but generally are seen as operations with 2,000 or more pigs, 700 or more dairy cattle, or over 1,000 beef cattle.

The growth of these operations has been linked to public health problems like various cancers as well as infant death and miscarriages, caused by water contaminated with waste runoff from farms. On the other side of Wisconsin, residents in Kewaunee County have seen manure coming out of their faucets from one the largest CAFOs in the state, who sued the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resource last year when they were denied a request to nearly double their size.

As more confined animal feeding operations, like the hog farm pictured, pop up across the country, towns and counties have attempted to regulate their growth. chayakorn lotongkum / Getty Images Grist

When communities try to respond with local-level enforcement, both industry interests and a lack of power at the local level cause townships to get creative with their responses.

Every state has some form of a “right-to-farm” law, which stops farms from being targeted for nuisances related to the daily operations of the industry, such as odor, noise, and effects on the environment. From there, each state has some form of a regulatory process that outlines how large farms are allowed to operate.

In Iowa, which leads the country in CAFOs, the state government sets all regulatory requirements and local towns and counties are out of luck when it comes to enforcement, according to John Robbins, Planning and Zoning Administrator for Cerro Gordo County, Iowa. He said the county once had a restrictive ordinance for CAFO zoning on the books, but after a state law took control, counties now have “very limited authority.”

Last year, when a Missouri hog farm spilled 300,000 gallons of waste into nearby waterways, two counties attempted to regulate CAFOs differently than the state government. Those counties had to sue to challenge state-level laws and are now awaiting trials in the state Supreme Court.

Further West, Gooding County, Idaho has seen the whole gambit of what Wisconsin towns could be facing. In 2007, the central Idaho county named after a famed state sheep rancher passed an ordinance regulating CAFOs in the county limits. A month later, industry groups Idaho Dairymen’s Association and Idaho Cattle Association started a court battle with the county that ended two years later, with the state supreme court ruling in the county’s favor. Gooding County’s legal representatives did not respond to a request for comment.

Wisconsin’s Livestock Facility Siting Law generally restricts how local municipalities can stop or slow new CAFOs or expansions to current facilities. This law is at the crux of arguments in opposition to Laketown and other surrounding communities’ proposed or passed ordinances.

Other Wisconsin communities have enacted local level ordinances to regulate these large farms. In 2016, northern Bayfield County enacted a CAFO ordinance that imposed a one-time fee and required operators to have increased manure storage options. After a large hog farm estimated to produce over 9 million gallons of manure a year was proposed in Polk County a few years ago, the county attempted a moratorium on CAFOs, but the measure did not pass.

Since then, at least five neighboring towns of Laketown have passed similar ordinances.

“This is one of the first times I’ve seen a town refuse to back down to some of these letters.”

Adam Voskuil, Midwest Environmental Advocates staff attorney

The Laketown ordinance that sparked the lawsuit is an operations ordinance, unlike Bayfield’s ordinance which focused on zoning. Laketown CAFO operators are asked to file a one-time fee equal to a dollar for every animal unit as well as give detailed plans of how they will prevent ground and air pollution stemming from their facilities. Passed in 2021, the ordinance states it is based upon Laketown’s obligation to “protect the health, safety and general welfare of the public.”

All along the way, industry groups Venture Dairy Cooperative and the Wisconsin Dairy Alliance, its website features the slogan “Fighting for CAFOs Every Day,” have sent threatening letters to towns that passed ordinances or moratoriums, with the help of WMC.

“This is standard operating procedure for the Big Ag boys,” said Lisa Doerr, a Laketown resident of over 20 years who raises horses and commercially farms hay and alfalfa with her husband.

Doerr has been involved at the local level in opposition to CAFO since Polk County learned of a proposed 26,000-hog farm. Doerr, who worked with the Large Livestock Town Partnership, a multi-town committee that examines the environmental impact of CAFOs, said she worried that the landscape of the town and county would change if local action wasn’t taken.

“The name of our town is Laketown because we’ve got lakes everywhere,” she said. “We still have a middle class farming community. We haven’t had corporate ag take over everything.”

In its recently filed response letter, Laketown’s attorney said WMC’s argument falls flat as it is based solely on the state-level zoning law, while the town’s ordinance regulates the operations and conduct of a facility. They also noted that since the ordinance passed, no facilities have applied for a permit, which means the town has not yet enforced any actions WMC says are unlawful. Laketown board chair Daniel King declined to comment, citing the ongoing lawsuit.

Midwest Environmental Advocates attorney Voskuil said he was heartened to see that Laketown has been holding its ground. “This is one of the first times I’ve seen a town refuse to back down to some of these letters,” he said.

Farther south in Wisconsin, another county is reeling from letters threatening legal action. Crawford County, which borders Iowa, enacted a CAFO moratorium in 2019 but did not renew the moratorium after studying the issue for a year. Forest Jahnke, a coordinator with the Crawford Stewardship Project, said the decision to not renew the moratorium was highly influenced by the deluge of similar threats of litigation and backlash, which had a “chilling effect” on efforts to move forward.

“The fear of litigation is a very strong and deep one in our local municipalities and county governments,” Jahnke, who was a member of the committee studying the CAFO moratorium in Crawford County, said.

Since the moratorium rolled back, the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources greenlit a Crawford County hog farm, home to 8,000 pigs and expected to generate 9.4 million gallons of manure each year

Featured Image: Hog farm by via Wikimedia (CC BY 2.0)

by DGR News Service | Mar 4, 2022 | ACTION, Culture of Resistance, Education, Movement Building & Support, Repression at Home, Strategy & Analysis

Editor’s note: People who confront the destruction of the planet find a legal system that prioritizes corporations and not uncommonly become the targets of police surveillance. Unless we take precautions, police surveillance tools can uncover our plans and organizational structures—and can contribute to a culture of paranoia that discourages action.

This training, from the Freedom of the Press Foundation, consists of interactive materials for learning what sort of tools law enforcement agencies use against journalists, but the material is practically applicable for organizers as well. We encourage our readers to study this material and consider appropriate countermeasures.

by Freedom of the Press Foundation

The Digital Security Training team at Freedom of the Press Foundation works with news organizations to better protect themselves, their colleagues, and sources by upgrading their security posture. In an environment where journalists are increasingly under attack, experiencing targeted hacking, harassment, and worse, we want to see systemic change in the way news organizations learn about and address their digital security concerns. While journalists come from many professional backgrounds, one place we can most reliably address this need for digital security education systemically is within journalism schools, where students are already learning many of the skills they will need in a contemporary newsroom. We know many programs feel underprepared for education of this kind, so we built this curriculum to better support J-schools’ goals for digital security education.

Below, we have created modules responsive to a variety of digital security topics. We intend for this resource to be used by journalism professors and educators looking for a starting point for digital security education. Ultimately, it’s our hope that by tinkering with these materials, you might take advantage of the parts most useful or inspiring to you, and make this curriculum your own.

Police Surveillance Tools Training

This section on surveillance tools used by law enforcement is discussion focused, and intends to get students to think critically about the relationship between surveillance, privacy, and transparency. It begins with lecture canvassing a variety of law enforcement surveillance technology, based on research from from the Electronic Frontier Foundation. Afterward, the module opens into an activity to investigate surveillance technology used in a location of their choice, followed by a discussion of their interpretation of law enforcement surveillance technologies they’ve discovered.

Prerequisites

Threat modeling

Legal requests in the U.S.

Estimated time

60-70 minutes

Objectives

- Upon successful completion of this lesson, students will be able to distinguish between technology commonly used by law enforcement to conduct surveillance in physical spaces.

- Students will be able to identify which of these tools are used in a specific physical location, based on publicly-accessible reporting tools.

Why this matters

The technical capabilities of law enforcement actors may affect journalists’ threat models when conducting work in risky situations. For example, when meeting a sensitive source their location may be tracked through a constellation of surveillance equipment, or their phone numbers and current call or text data may be scooped up when covering protests.

Homework

(Before class)

Sample slides

Credit to Dave Maass and the Electronic Frontier Foundation for these slides, with minor modifications.

Law enforcement surveillance tech (Google Slides)

Activities

Have students open up Atlas of Surveillance and report back for the group with surveillance technology used in a location where they’ve lived in the U.S. (e.g., where their hometown is; the campus).

Questions for discussion

- In terms of their ability to compromise journalistic work, which one of these technical law enforcement capabilities is most concerning to you? What makes it concerning?

- If that’s not especially concerning, why is that?

- Out of respect for peoples’ privacy, are there any issues you think should be “off the table” for journalistic coverage? If so, what are those issues, and why do you think they should be off the table?

- We often talk about privacy for people, but transparency for institutions. Why the distinction? Are there times when individual actions demand transparency, and when institutions have a meaningful claim to privacy?

This article was first published by the Freedom of the Press Foundation. It is republished under the CC-BY-NC 2.0 license. Banner image: Police training using bodycams via flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0).

![Decade Long Gag Order for Speaking Out [Press Release]](https://dgrnewsservice.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2023/06/kilian-karger-CTkLczb9HeA-unsplash-1080x675.jpg)