by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 22, 2018 | Repression at Home

Featured image: On August 31, 2016, “Happy” American Horse from the Sicangu Nation locked himself to construction equipment as a direct action against the Dakota Access pipeline. Credit: Desiree Kane, CC BY 3.0

by Steve Horn / DeSmog

On the heels of Iowa and Ohio, Wyoming has become the third state to introduce a bill criminalizing the type of activities undertaken by past oil and gas pipeline protesters.

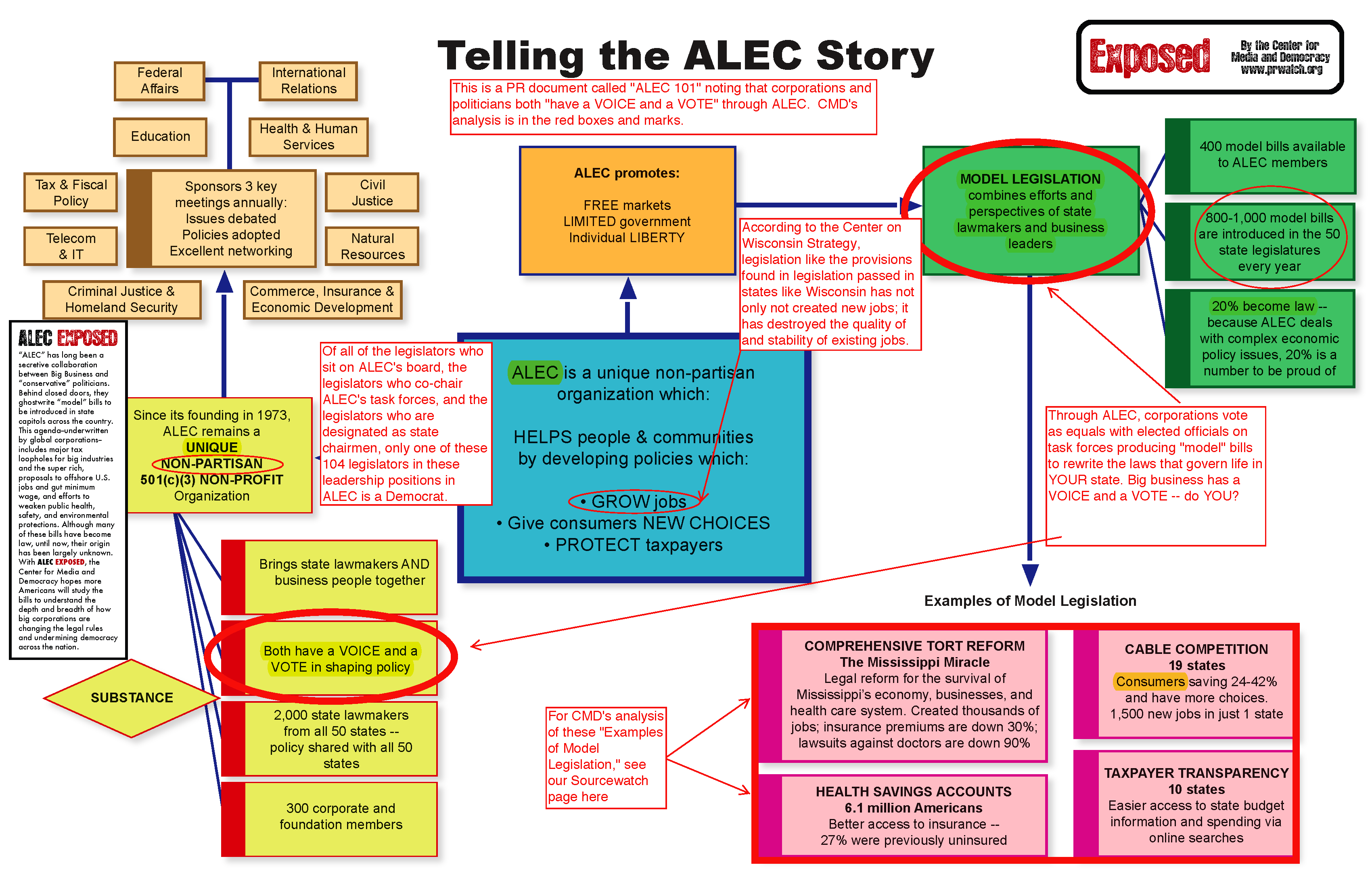

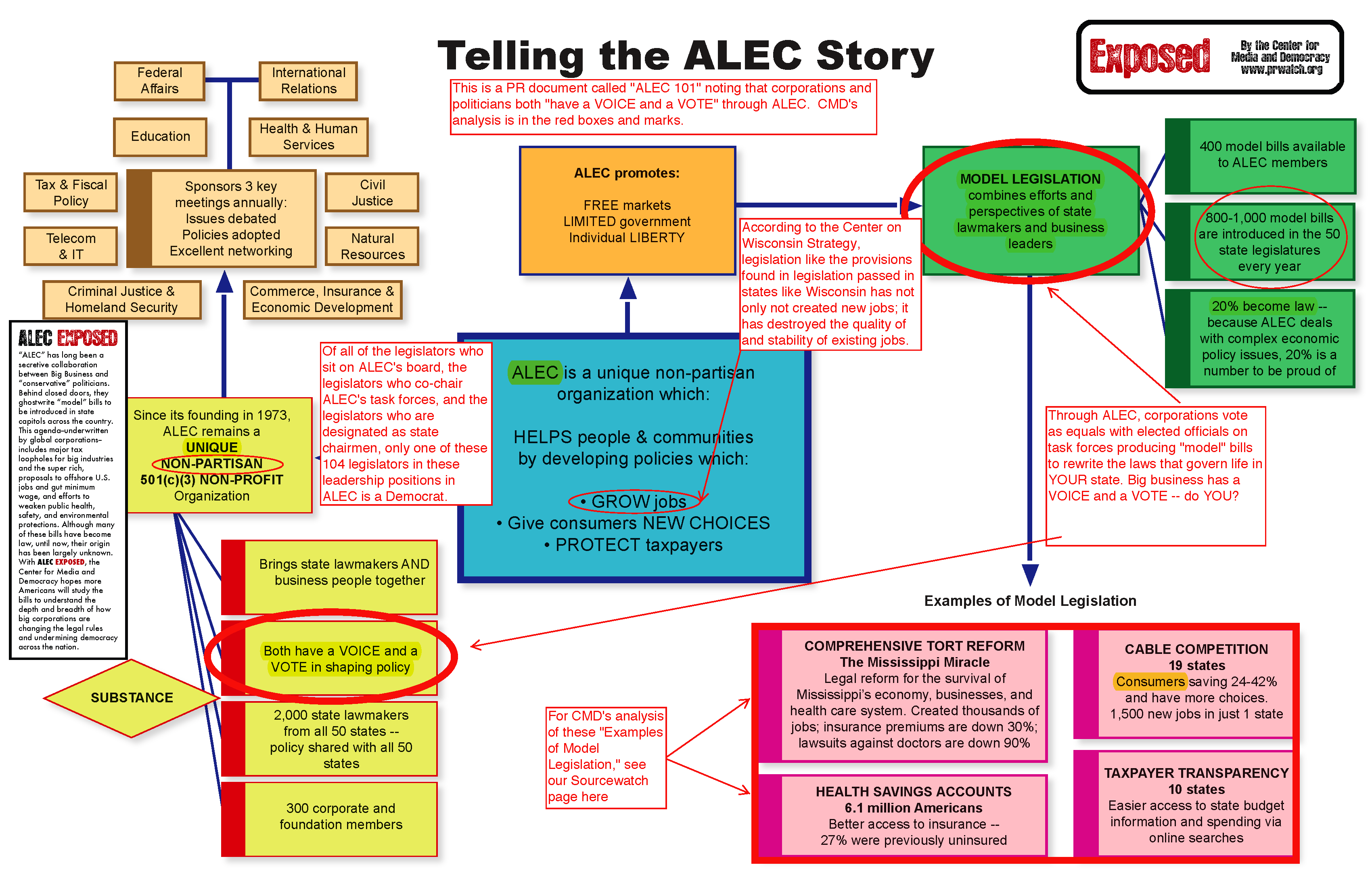

One of the Wyoming bill’s co-sponsors even says it was inspired by the protests led by the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe against the Dakota Access pipeline, and a sheriff involved in policing those protests testified in support of the bill at a recent hearing. Wyoming’s bill is essentially a copy-paste version of template legislation produced by the conservative, corporate-funded American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC).

At the organization’s December meeting, ALEC members voted on the model bill, the Critical Infrastructure Protection Act, which afterward was introduced in both Iowa and Ohio.

Like the ALEC version, Wyoming’s Senate File 74 makes “impeding critical infrastructure … a felony punishable by imprisonment for not more than ten (10) years, a fine of not more than one hundred thousand dollars ($100,000.00), or both.” Two of the bill sponsors of SF 74, Republican Sens. Eli Bebout and Nathan Winters, are ALEC members. SF 74 has passed unanimously out of its Senate Judiciary Committee and now moves onto the full floor.

ALEC‘s model bill, in turn, was based on two Oklahoma bills, HB 1123 and HB 2128. The Sooner State bills, now official state law, likewise impose felony sentencing, 10 years in prison, and/or a $100,000 fine on individuals who “willfully damage, destroy, vandalize, deface, or tamper with equipment in a critical infrastructure facility.” As DeSmog has reported, the Iowa bill has the lobbying support of Energy Transfer Partners — the owner of the Dakota Access pipeline (DAPL) which runs through the state — as well as that of the American Petroleum Institute and other oil and gas industry companies.

ALEC brings together primarily Republican Party state legislators and lobbyists to enact and vote on “model” legislation at its meetings, which take place several times a year. Within different task forces at these meetings, corporate lobbyists can voice their support or critiques of bills, while also getting a vote. Those bills often then are introduced as legislation in statehouses nationwide, as in this latest example in Wyoming.

Hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) in Wyoming has helped the state vastly increase its natural gas production and spurred pipeline build-out. However, multiple studies in recent years have also linked fracking-related activities around the small town of Pavilion to groundwater contamination.

Image: Center for Media and Democracy

Targeting ‘Ecoterrorism’

Wyoming’s bill, like the ALEC model bill and one of the Oklahoma bills, includes language implicating any organization “found to be a conspirator” and lobbing a $1 million fine on any group which “aids, abets, solicits, encourages, hires, conspires, commands, or procures a person to commit the crime of impeding critical infrastructure.”

State Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Leland Christensen, a Republican and one of the bill’s co-sponsors, said when he introduced the bill that legislative language was needed to hold accountable those “organizations that sponsor this kind of ecoterrorism.”

The fiscal note for the Wyoming bill says that the “fiscal impact to the judicial system is indeterminable,” while also discussing the prospective costs of incarcerating people under the auspices of the legislation.

“The Department of Corrections states that the impact of the bill is indeterminable as there is currently no way to accurately estimate the number of offenders that will be sentenced pursuant to the bill,” reads the fiscal note. “Each year of incarceration currently costs the state approximately $41,537 per inmate, including medical costs. Each year of community supervision costs the state approximately $2,000 per inmate.”

ALEC Model Confirmed

One co-sponsor of the Wyoming bill, its sole Democratic supporter, Rep. Stan Black, told WyoFile.com that the bill was inspired by what took place at the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation and that SF 74 was based on the ALEC model bill.

Shortly after ALEC members voted to adopt the Oklahoma legislation as a model bill, Oklahoma’s HB 1123 was also adoptedby the corporate-funded Council of State Governments (CSG) as a piece of “Shared State Legislation” (SSL) at its own annual meeting held just a week later.

One of the state legislative officials sitting on CSG‘s Committee on Shared State Legislation, North Dakota’s Republican Rep. Kim Koppelman, has a long history of involvement with ALEC, and throughout 2017 he spoke critically of the Indigenous-led movement against the Dakota Access pipeline.

ND Rep. Kim Koppelman; Photo Credit: North Dakota Legislature

“One of the major issues we dealt with was several bills introduced in response to the violent protests at the site of the Dakota Access pipeline,” Koppelman wrote in a February 2017 article halfway through the North Dakota Legislature’s session. “As you may know, peaceful protests led by Native American tribes began this summer but they attracted others from throughout the nation and deteriorated into illegal occupation of sites on federal land, trespassing on private land, blocking of roadways and some incidents of violence.”

At the beginning of 2017, Koppelman co-sponsored three pieces of North Dakota legislation, which crack down on pipeline protests. Two of them passed and are now state law.

The bills “struck a good balance to ensure everyone’s constitutional right to peacefully protest, which we cherish, but to provide for appropriate consequences when anyone crosses the line into anarchy, terrorizing or destruction of property,” wrote Koppelman in his article. “These bills have been fast tracked to give law enforcement the tools they need.”

After DeSmog filed an open records request pertaining to Koppelman’s ALEC and CSG efforts in this area, he told DeSmog, “I have no documents or records concerning the subject of your request but, even if I did, you should be aware that, under North Dakota Century Code Section 44-04-18.6, communications and records of a member of the North Dakota Legislative Assembly are not subject to disclosure.”

In a follow-up email exchange, Koppelman told DeSmog that he “had no role in bringing the bill” to CSG and does not know who did so.

“Frankly, I don’t even specifically recall the bill you’ve inquired about, without going back to review it,” Koppelman told DeSmog. “I also don’t recall who may have supported or opposed it at that meeting, either on the Committee or among the members of the public in the audience.”

For the ALEC bill, Koppelman also said he could not speak to its origins as a model or who has pushed it at the state-level since becoming a model. When asked by DeSmog if CSG records the Shared State Legislation meetings or keeps minutes, Koppelman said that he does not believe so “because the result of meetings and the committee’s work is in the published volume” of Shared State Legislation which CSG disseminates annually.

CSG has in the past, though, kept meeting minutes of its SSL voting sessions, doing so as recently as 2014. Those minutes included an attendance list, which listed nearly three times the number of lobbyists present as state legislators and showed industry attendees representing both the American Gas Association and the Consumer Energy Alliance.

According to a letter obtained and published by HuffPost, the ALEC model bill has also enjoyed the backing of the American Gas Association, American Chemistry Council, American Fuel & Petrochemical Manufacturers (AFPM), and Marathon Petroleum.

Industry, Cops Push ALEC Bill in Wyoming

According to a follow-up story by WyoFile.com, the Wyoming Senate Judiciary Committee had Wyoming Business Alliance lobbyist Cindy DeLancey, rather than the lead sponsor, Sen. Christensen, introduce the bill in front of the committee.

Before taking over as head of the Wyoming Business Alliance, DeLancey worked as a director of government and public affairs for BP, where she did “government and public affairs support for the Leadership Team of the Lower 48 North Business Unit,” according to her LinkedIn profile. DeLancey’s Wyoming Business Alliance biography also shows that she formerly served as the chair of the Petroleum Association of Wyoming’s Government and Public Relations Committee. She did not respond to a request for comment.

Wyoming Business Alliance steering committee members include representatives from the Petroleum Association of Wyoming, Chesapeake Energy, Devon Energy, and Jonah Energy. Petroleum Association of Wyoming leadership committees consist of representatives from companies such as Devon Energy, Chesapeake Energy, BP, Anadarko Petroleum, and other companies, while its board of directors lists officials from those companies, plus ExxonMobil, EOG Resources, Halliburton, Williams Companies, and others.

WyoFile.com has reported that, according to a document received from Sen. Christensen, the Petroleum Association and other oil and gas companies have also come out as official supporters of the bill, along with law enforcement representatives. The Wyoming bill’s official backers include the Wyoming Association of Sheriffs and Chiefs of Police, the Wyoming Business Alliance, the Petroleum Association of Wyoming, the Wyoming Petroleum Marketers Association, American Fuel and Petrochemical Manufacturers (AFPM), Holly Frontier Corporation, Anadarko Petroleum, and ONEOK.

According to a special events calendar obtained by DeSmog, the Wyoming Business Alliance hosted a reception at the Cheyenne Botanic Gardens on February 12, just days after Wyoming bill SF 74 was introduced on February 9.

On March 1, ALEC will also host a reception at the Nagle-Warren Mansion Cheyenne, according to that calendar, with invited guests asked to RSVP to Wendy Lowe or David Picard. Picard currently has no oil and gas industry lobbying clients, according to his lobbying disclosures, but his lobbying firm’s website says he formerly did so for companies such as Shell, BP, and Marathon. He did not respond to a request for comment for this story.

According to lobbying disclosure forms, Lowe works as a lobbyist for Williams Companies, a major pipeline company with over 3,700 miles of pipeline laid in Wyoming. Lowe also formerly served as associate director of the Petroleum Association of Wyoming, according to her LinkedIn Profile.

Credit: Wyoming State Legislature

Lowe, the private sector chairwoman for ALEC in Wyoming as of 2014, won the state chair of the year award from ALEC in 2012. She has also previously received corporate-funded “scholarship” gifts to attend ALEC meetings as an official Wyoming representative, according to a 2013 report published by the nonprofit watchdog group Center for Media and Democracy.

An ALEC newsletter from May 2011 shows that, at an ALEC event Lowe co-hosted in 2011 in Wyoming, she praised the organization for “creating a unique environment in which state legislators and private sector leaders can come together, share ideas, and cooperate in developing effective policy solutions.”

The Center for Media and Democracy also reported in 2014 that Lowe, a former Peabody Energy lobbyist, gave a presentation titled, “Increasing Travel Reimbursement Income” at an ALEC meeting in Chicago in 2013. But Lowe told DeSmog that, although she attended the Senate hearing on the bill, she did not know about it until it was proposed and is not lobbying for it.

National Sheriffs: DAPL Full Circle

At a state Senate Judiciary Committee hearing on the Wyoming bill, Laramie County Sheriff Danny Glick also came out in support of the legislation, warning that a situation similar to Standing Rock could happen in Wyoming.

“One of our Niobrara county commissioners already has graffiti going up — ‘No DAPL’ — in that area up there,” Glick said at the hearing, referring to the shorthand for the Dakota Access pipeline. Glick, an Executive Committee member and Immediate Past President of the National Sheriffs’ Association, was one of the most supportive sheriffs pushing what has been characterized as a heavy-handed and militaristic reaction by law enforcement to the activism at Standing Rock.

Under the direction of Glick, Laramie County sent officers to the Dakota Access protests under the auspices of the Emergency Management Assistance Compact (EMAC), triggered after North Dakota’s Republican Governor Jack Dalrymple issued an emergency order on August 19, 2016. Glick too, spent time at Standing Rock and spoke at a press conferencealongside Morton County Sheriff Kyle Kirchmeier on October 6, 2016.

Laramie County Sheriff Glick. Credit: National Sheriffs’ Association Facebook Page

Glick, who attended a roundtable meeting at the White House in February 2017 with President Donald Trump and other sheriffs, was also previously CC‘d on a set of emails obtained by DeSmog and Muckrock in which the National Sheriffs’ Association and public relations firms it had hired wrote talking points in an attempt to discredit those who participated at Standing Rock. Those talking points said to describe the anti-pipeline movement as rife with “anarchists” and “Palestinian activists” who used violence and possessed “guns, knives, etc.”

‘Worst Instincts of Power’

Critics say the Wyoming bill could have far-reaching and negative impacts, if it becomes law, both in terms of criminal sentencing and for First Amendment rights. The American Civil Liberties Union of Wyoming, for example, has come out against the bill on both grounds.

The Sierra Club in Wyoming agreed, saying in an email blast that the bill is “explicitly designed to crush public opposition to projects like the Dakota Access and Keystone pipelines, by preventing the kind of protests that occurred at Standing Rock.”

Even people representing industry interests and within the Republican Party have come out against the bill as it currently reads.

“This bill appeals to the absolute worst instincts of power,” Larry Wolfe, a Wyoming attorney who represents the oil and gas industry, said at a hearing about the bill, according to WyoFile.com. “We the powerful must protect things that are already protected under existing law.”

Republican Senator Cale Case largely echoed the concerns put forward by Wolfe.

“This country has been through WWII, civil unrest in the 1960s and a heck of a lot more, but we didn’t need legislation like this,” Case conveyed in an email to WyoFile.com. “Good laws already exist to protect property without this chilling impact on free speech.”

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 30, 2018 | Colonialism & Conquest

Featured image: The Aguaprieta pipeline crosses the Yaqui River (Río Yaqui), the water source for the Yaqui, an indigenous tribe residing in the Yaqui Valley in Sonora, Mexico. Photo: Tomas Castelazo (CC). As far as one Yaqui community is concerned, the pipeline will never be completed.

by Gabriella Rutherford / Intercontinental Cry

In 2013, Enrique Peña Nieto’s government deregulated Mexico’s energy sector, opening it up to foreign investors for the first time 75 years. In what he called an “historic opportunity”, the Mexican President proclaimed “This profound reform can lift the standards of living for all Mexicans.”

But not everyone stands to see their quality of life materially improve from the deregulated sector. Such is the case for the Yaquí Peoples in Sonora state, Mexico, whose territory is currently home to an 84-kilometre stretch of natural gas pipeline.

The Aguaprieta (Agua Prieta) pipeline starts out in Arizona and stretches down 833km to Agua Prieta, in the northeastern corner of the Mexican state of Sonora—cutting through Yaqui territory along the way.

Once completed, the pipeline would also cross Yaqui River (Río Yaqui), the Yaqui’s main source of water.

More than a few Yaqui are adamant that they will see no benefits from the project. “The gas pipeline doesn’t help us, it only benefits businessmen, factory owners, but not the Yaqui” said Francisca Vásquez Molina, a Yaquí from the Loma de Bacúm community.

As with Keystone XL and Dakota Access pipelines, the Aguaprieta project comes with its own share of risks.

In addition to the considerable environmental impact that stems from the pipeline’s construction, the high methane content of natural gas could bring on disaster. Rodrigo Gonzalez, natural resources and environmental impact expert, maintains that in the event of a gas explosion all human, plant and animal life within a one-kilometre radius surrounding the explosion would be lost. Anyone within the second kilometre would risk second and third-degree burns.

In the community of Loma de Bacúm, the gas pipeline is just 700 m from houses. In nearby Estación Oroz, it is 591m from a primary school.

Gonzalez has pointed out that another viable route for the pipeline was initially considered by the company that could have avoided Yaqui territory altogether. He suggests this route was ultimately rejected to save costs. “At the beginning of the project, two routes were mooted. That which didn’t cross indigenous territory cost 400 million pesos whilst that which puts Yaquí lives at risk costs 100 million pesos.”

IEnova, the company behind the pipeline, has repeatedly made assurances that all due safety procedures have been followed in construction and that the risk of accidents is minimal but this has not been enough to assuage the fear or anger of everyone opposing the gas pipeline.

In a public statement last year, the group Solidaridad Tribu Yaquí said, “This is a people that say no to a megaproject of death, dispossession and destruction[…]These rich men don’t care about the life of one, two, or three people, much less if they are indigenous… [they] don’t care if the Yaqui culture is exterminated. What is important to these rich men is to conclude the work and pocket all the profits to be brought about by the appropriation of the Yaqui territory.”

Not all Yaquí communities are united in rejecting the gas pipeline, however. Indeed, of the eight Yaquí communities consulted, only the Loma de Bacúm community refused to give their consent to the project. The other seven communities chose to accept the compensation offered. This decision has sadly resulted in tensions between Loma de Bacúm and the other communities. Things reached a critical point in October 2016 where one Yaquí member died and thirty injured in a confrontation involving different Yaquí communities.

Seemingly alone in their struggle, the Loma de Bacúm Yaquí have consistently resisted the Aguaprieta pipeline. In April 2016, they successfully fought to be granted a moratorium on its construction. When, in 2017, it became clear that IEnova, would carry on regardless and that neither federal nor state or authorities could be counted on for support, the Loma de Bacúm community resorted to more drastic measures. On May 21, community members removed cables which had been laid down in the preliminary stages of the gas pipeline construction. Then, after another court ruling that IEnova should remove all infrastructure within 24 hours fell on deaf ears, on August 22 the community went ahead and cut a 25-foot section out of the live gas pipeline, despite the grave risks they ran in doing so. As a result of the community’s actions in August, IEnova was forced to cut off the gas flow in the area and it has remained out of service ever since.

The community has been accused of sabotage and vandalism to IEnova property but the community maintains that IEnova, a company owned by US-based Sempra Energy, is trespassing on their land and holds them responsible for all damage brought on by the construction of a pipeline to which they never consented.

In a video shared on Facebook, one community member explained “If you want to have us killed, there’s no problem. We’re not scared of that… We’re not scared of this company nor this project…All that the Yaquí tribe is asking for is that the law is upheld and that federal and state government respect it. If you want to have us killed, go ahead there’s no problem but we’ll defend our land and that is our right.”

In September 2017, a judge once again found in favour of the Yaquí community ruling that IEnova did not have the right to enter Yaquí territory to repair the gas pipeline. Whether this latest ruling will carry more weight with both local and state authorities than the previous ones remains to be seen.

For the time-being, the stand-off looks set to continue. Loma de Bacúm has made it clear it will not back down until the pipeline is removed or rerouted. “If they want to build a pipeline. that’s fine”, said community spokesperson Guadalupe Flores, “but it will not pass through here.” At the same time, IEnova refuses to accept that one small community can curtail their plan to use Yaquí territory in order to provide electricity to the Comisión Federal de Electricidad (CFE), the country’s largest electric utility. Nor does it seem willing to brazenly defy the court’s latest ruling, at least for the time-being.

The struggle in Loma de Bacúm echoes loudly among all Indigenous Peoples who are grappling to make sure the resource sector cannot run roughshod over human rights and environmental concerns; but it is perhaps loudest in Mexico. Since the new energy policy went into effect, four other pipeline projects have been suspended. Looking ahead, a “shale offensive” is now set to begin later this year should the PRI retain power in July, leading to a proliferation of similar conflicts.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 7, 2018 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction

Featured image: The critically endangered North Atlantic right whale is a species of utmost concern should seismic airgun blasting be allowed off the Atlantic coast. Photo Credit: Moira Brown and New England Aquarium.

by Mike Gaworecki / Mongabay

The Trump Administration has unveiled its plan to open nearly all of the United States’ coastal waters to oil and gas drilling.

U.S. Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke announced the National Outer Continental Shelf Oil and Gas Leasing Program for 2019-2024 yesterday, which includes a proposal to open up more than 90 percent of the country’s continental shelf waters to future exploitation by oil and gas companies. The draft five-year plan also proposes the largest number of offshore oil and gas lease sales in U.S. history.

“Responsibly developing our energy resources on the Outer Continental Shelf in a safe and well-regulated way is important to our economy and energy security, and it provides billions of dollars to fund the conservation of our coastlines, public lands and parks,” said Secretary Zinke. “Today’s announcement lays out the options that are on the table and starts a lengthy and robust public comment period. Just like with mining, not all areas are appropriate for offshore drilling, and we will take that into consideration in the coming weeks.”

The Obama Administration blocked drilling on about 94 percent of the outer continental shelf, but, in April 2017, Trump issued an executive order that called for a review of the 2017-2022 Five Year Outer Continental Shelf Oil and Gas Leasing Program finalized under Obama in favor of implementing Trump’s so-called “America-First Offshore Energy Strategy.”

The draft five-year plan that has just been released by the Trump Administration’s Interior Department would open up 25 of 26 outer continental shelf regions to drilling. The North Aleutian Basin, which lies off the northern shore of the Alaska Peninsula and extends into the Bering Sea, was the only region exempted from drilling in the new plan, the New York Times reports.

The Interior Department proposes to hold 47 lease sales in those 25 regions — including 19 off the coast of Alaska, 12 in the Gulf of Mexico, nine in the Atlantic Region, and seven in the Pacific Region. “This is the largest number of lease sales ever proposed for the National [Outer Continental Shelf] Program’s 5-year lease schedule,” the Interior Department said in a statement.

Earlier moves by the Trump Administration to open the U.S. Atlantic coast to drillinghave already drawn fierce opposition. An alliance of more than 41,000 businesses and 500,000 fishing families from Florida to Maine was joined by fishery management councils for the Mid-Atlantic, New England, and the South Atlantic regions in speaking out against oil exploration and development in the Atlantic. One of their chief concerns is the incredibly disruptive exploration technique known as seismic airgun blasting, which would need to be used to determine how much oil is actually underneath the floor of the Atlantic Ocean off the U.S. East Coast given that oil drilling has been banned there for decades.

Drilling in the Pacific Ocean off the U.S. West Coast has been banned since a 1969 oil spill in Santa Barbara, California. Local officials there also vowed to fight the Trump Administration’s move to open their coastal waters to the oil and gas industry: “For more than 30 years, our shared coastline has been protected from further federal drilling and we’ll do whatever it takes to stop this reckless, short-sighted action,” California Governor Jerry Brown, Oregon Governor Kate Brown, and Washington Governor Jay Inslee said in a joint statement.

Continue reading at Mongabay

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 3, 2018 | Lobbying

Featured image: Yaqui community gathering Credit: Andrea Arzaba, CC BY–SA 4.0

by Steve Horn / DeSmog

Since Mexico privatized its oil and gas resources in 2013, border-crossing pipelines including those owned by Sempra Energy and TransCanada have come under intense scrutiny and legal challenges, particularly from Indigenous peoples.

Opening up the spigot for U.S. companies to sell oil and gas into Mexico was a top priority for the Obama State Department under Hillary Clinton.

Mexico is now facing its own Standing Rock-like moment as the Yaqui Tribe challenges Sempra Energy’s Agua Prieta pipeline between Arizona and the Mexican state of Senora. The Yaquis in the village of Loma de Bacum claim that the Mexican government has failed to consult with them adequately, as required by Mexican law.

Indigenous Consultations

Under Mexico’s new legal approach to energy, pipeline project permits require consultations with Indigenous peoples living along pipeline routes. (In addition, Mexico supported the adoption of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which includes the principle of “free, prior and informed consent” from Indigenous peoples on projects affecting them — something Canada currently is grappling with as well.)

It was a similar lack of indigenous consultation which the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe said was the impetus for lawsuits and the months-long uprising against the Dakota Access pipeline near the tribe’s reservation in Cannon Ball, North Dakota, in late 2016. Now, according to Bloomberg and Mexican reporter Gema Villela Valenzuela for the Spanish language publication Cimacnoticias, history is repeating itself in the village of Loma de Bacum in northwest Mexico.

Agua Prieta, slated to cross the Yaqui River, was given the OK by seven of eight Yaqui tribal communities. But the Yaquis based in Loma de Bacum have come out against the pipeline passing through their land, even going as far as chopping out a 25 foot section of pipe built across it.

“The Yaquis of Loma de Bacum say they were asked by community authorities in 2015 if they wanted a 9-mile tract of the pipeline running through their farmland — and said no. Construction went ahead anyway,” Bloomberg reported in a December 2017 story. “The project is now in a legal limbo. Ienova, the Sempra unit that operates the pipeline, is awaiting a judicial ruling that could allow them to go in and repair it — or require a costlier re-route.”

As the legal case plays out in the Supreme Court of Justice in Mexico, disagreements over the pipeline and its construction in Loma de Bacum have torn the community apart and even led to violence, according to Cimacnoticias.

Construction of the pipeline “has generated violence ranging from clashes between the community members themselves, to threats to Yaqui leaders and women of the same ethnic group, defenders of the Human Rights of indigenous peoples and of the land,” reported Cimacnoticias, according to a Spanish-to-English translation of its October 2016 story.

“They explained that there have been car fires and fights that have ended in homicide. Some women in the community have had to stay in places they consider safe, on the recommendation of the Yaquis authorities of the town of Bácum, because they have received threats after opposing signing the collective permit for the construction of the pipeline.”

TransCanada’s Troubles Cross Another Border

While best known for the Canada-to-U.S. Keystone XL pipeline and the years-long fight to build that proposed tar sands line, the Alberta-based TransCanada has also faced permitting issues in Mexico for its proposed U.S.-to-Mexico gas pipelines.

According to a December 2017 story published in Natural Gas Intelligence, TransCanada’s proposed Tuxpan-Tula pipeline is facing opposition from the indigenous Otomi community living in the Mexican state of Puebla. With Tuxpan-Tula, TransCanada hopes to send natural gas from Texas to Mexico via an underwater pipeline named the Sur de Texas-Tuxpan pipeline into the western part of the country.

The Otomi community recently won a successful bid in Mexican district court to stop construction of Tuxpan-Tula.

“At a recent hearing on an indoor soccer court at the foot of Cerro del Brujo, or Shaman’s Hill, in the southern Mexican state of Puebla, a district judge sided with an indigenous community and ordered construction” of the pipeline to halt, Natural Gas Intelligence reported. “[T]he court made the order in response to pleas from the local Otomi indigenous community, which claims that the construction would disturb sacred ground.”

Energy sector privatization in Mexico, decried by the country’s left-wing political parties and leading 2018 presidential contender Andrés Manuel López Obrador, has actually opened up the sort of legal opportunities that the Otomi have pursued in court.

“What is new in Mexico is the requirement that indigenous communities should be consulted,” Ramses Pech, CEO of the energy analysis group Caraiva y Asociados, told Natural Gas Intelligence. “That kind of consultation has long been a part of any project in the U.S. and other countries, but not so here. It was obviously needed in Mexico, too, but it has added to the complexities of the Mexican legal system in areas such as land and rights of way.”

In the U.S., the tribal consultation process is governed by the National Historic Preservation Act’s Section 106. That law gave the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe standing to sue U.S. government agencies, though ultimately unsuccessfully, for what the tribe alleged were violations which took place during the inter-agency permitting process.