by DGR News Service | Apr 21, 2023 | ANALYSIS, Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Climate Change, Mining & Drilling

Editor’s Note: Mainstream environmental organizations propose electric vehicles (EVs) as a solution to every environmental crisis. It is not only untrue, but a delusion. It does not matter to the hundreds of lives lost whether they were killed for extraction of fossil fuel for traditional internal combustion (IC) cars, or for extraction of materials necessary for manufacturing EVs. What matters is that they are dead, never to come back, and that they died so a portion of humans could have convenient mobility. DGR is organizing to oppose car culture: both IC and EVs.

By Benja Weller

I am a rich white man in the richest time, in one of the richest countries in the world (…)

Equality does not exist. You yourself are the only thing that is taken into account.

If people realized that, we’d all have a lot more fun.

ZDF series Exit, 2022, financial manager in Oslo,

who illegally traded in salmon

Wir fahr’n fahr’n fahr’n auf der Autobahn

Vor uns liegt ein weites Tal

Die Sonne scheint mit Glitzerstrahl

(We drive drive drive on the highway

Ahead of us lies a wide valley

The sun shines with a glittering beam)

Kraftwerk, Single Autobahn / Morgenspaziergang, 1974

Driving a car is a convenient thing, especially if you live in the countryside. For the first time in my life I drive a car regularly, after 27 years of being “carless”, since it was left to me as a passenger. It’s a small Suzuki Celerio, which I call Celery, and fortunately it doesn’t consume much. Nevertheless, I feel guilty because I know how disturbing the engine noise and exhaust fumes are for all living creatures when I press the gas pedal.

So far, I have managed well by train, bus and bicycle and have saved a lot of money. As a photographer, I used to take the train, then a taxi to my final destination in the village and got to my appointments on time. Today, setting off spontaneously and driving into the unknown feels luxurious.

However, my new sense of freedom is in stark contrast to my understanding of an intact environment: clean air, pedestrians and bicyclists are our role models, children can play safely outside. A naive utopia? According to the advertising images of the car industry, it seems as if electric cars are the long-awaited solution: A meadow with wind turbines painted on an electric car makes you think everything will be fine.

“Naturally by it’s very nature.” says the writing on an EV of the German Post, Neunkirchen, Siegerland (Photo by Benja Weller)

In Germany, the car culture (or rather the car cult) rules over our lives so much that not even a speed limit on highways can be achieved. The car industry has been receiving subsidies from the government for decades and journalists are ridiculed when they write about subsidies for cargo bikes.

Right now, this industry is getting a green makeover: quiet electric cars that don’t emit bad air and are “CO2 neutral” are supposed to drive us and subsequent generations into an environmentally friendly, economically strong future. On Feb. 15, 2023, the green party Die Grünen published in its blog that the European Union will phase out the internal combustion engine by 2035: “With the approval of the EU Parliament on Feb. 14, 2023, the transformation of the European automotive industry will receive a reliable framework. All major car manufacturers are already firmly committed to a future with battery-electric drives. The industry now has legal and planning certainty for further investment decisions, for example in setting up its own battery production. The drive turnaround toward climate-friendly vehicles will create future-proof jobs in Europe.”

That’s good news – of course for the automotive industry. All the old cars that will be replaced with new ones by 2035 will bring in more profit than old cars that will be driven until they expire. That the EU along with the car producers, are becoming environmentalists out of the blue is hard to believe, especially when you see what cars drive on German roads.

In recent years, a rather opulent trend became apparent: cars with combustion engines became huge in size and gasoline consumption increased, all in times of ecological collapse and global warming. These oversized SUVs are actually called sport-utility vehicles, even if you only drive them to get beer at the gas station. Small electric cars seem comfortable enough and have a better environmental footprint than larger SUVs. But the automotive industry is not going to let the new electromobility business go to waste that easily and is offering expensive electric SUVs: The Mercedes EQB 350 4matic, for example, which weighs 2.175 tons and has a 291-hp engine, costs €59,000 without deducting the e-car premium.

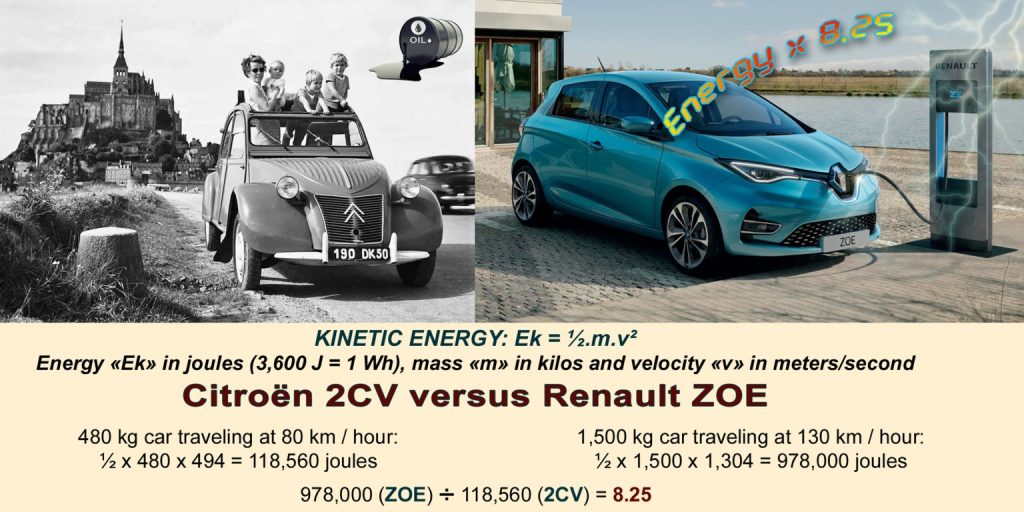

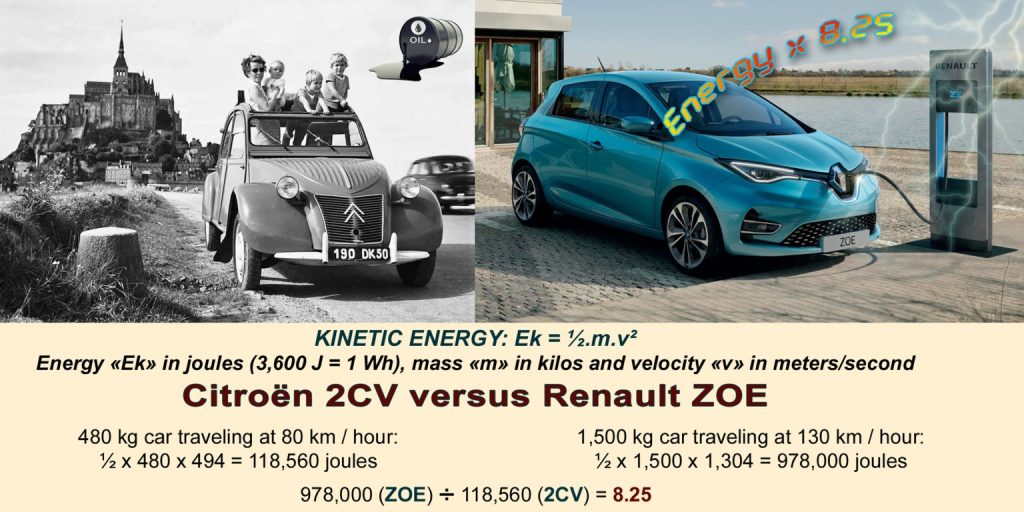

Comparing the Citroen 2CV and the Renault Zoe electric car shows that the Zoe uses about 8 times more kinetic energy. (Graph by Frederic Moreau)

If we look at all the production phases of a car and not just classify it according to its CO2 emmissions, the negative impact of the degradation of all the raw materials needed to build the car becomes visible. This is illustrated by the concept of ecological backpack, invented by Friedrich Schmidt-Bleek, former head of the Material Flows and Structural Change Department at the Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment and Energy. On the Wuppertal Institute’s website, one can read that “for driving a car, not only the car itself and the gasoline consumption are counted, but also proportionally, for example, the iron ore mine, the steel mill and the road network.”

“In general, mining, the processing of ores and their transport are among the causes of the most serious regional environmental problems. Each ton of metal carries an ecological backpack of many tons, which are mined as ore, contaminated and consumed as process water, and weigh in as material turnover of the various means of transport,” the Klett-Verlag points out.

Car production requires large quantities of steel, rubber, plastic, glass and rare earths. Roads and infrastructure suitable for cars and trucks must be built from concrete, metal and tar. Electric cars, even if they do not emit CO2 from the exhaust, are no exception. Added to this is the battery, for which electricity is needed that is generated at great material expense, a never-ending cycle of raw material extraction, raw material consumption and waste production.

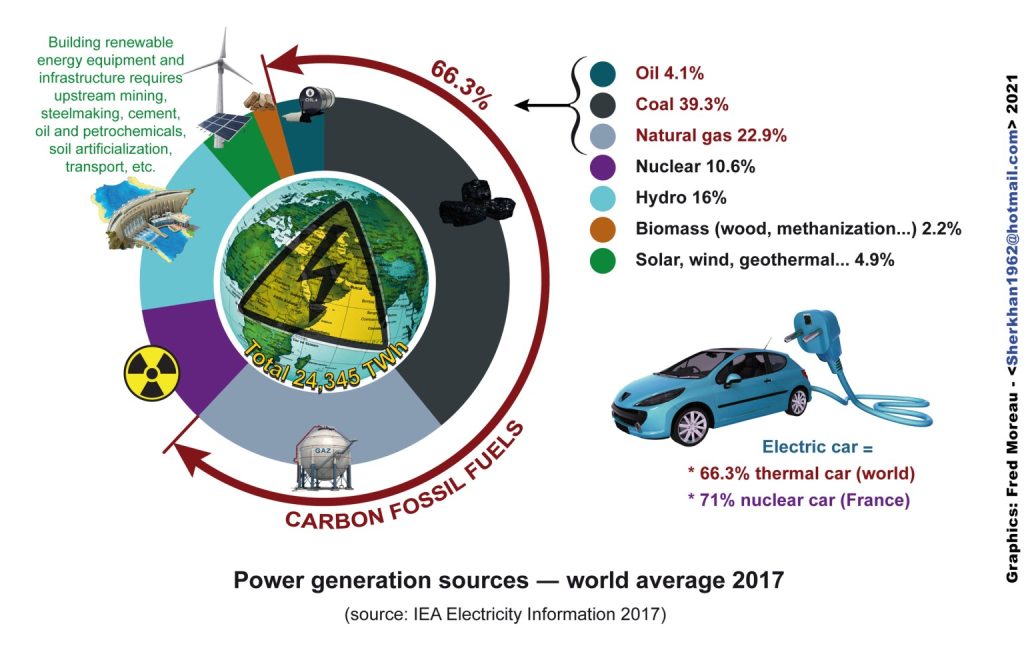

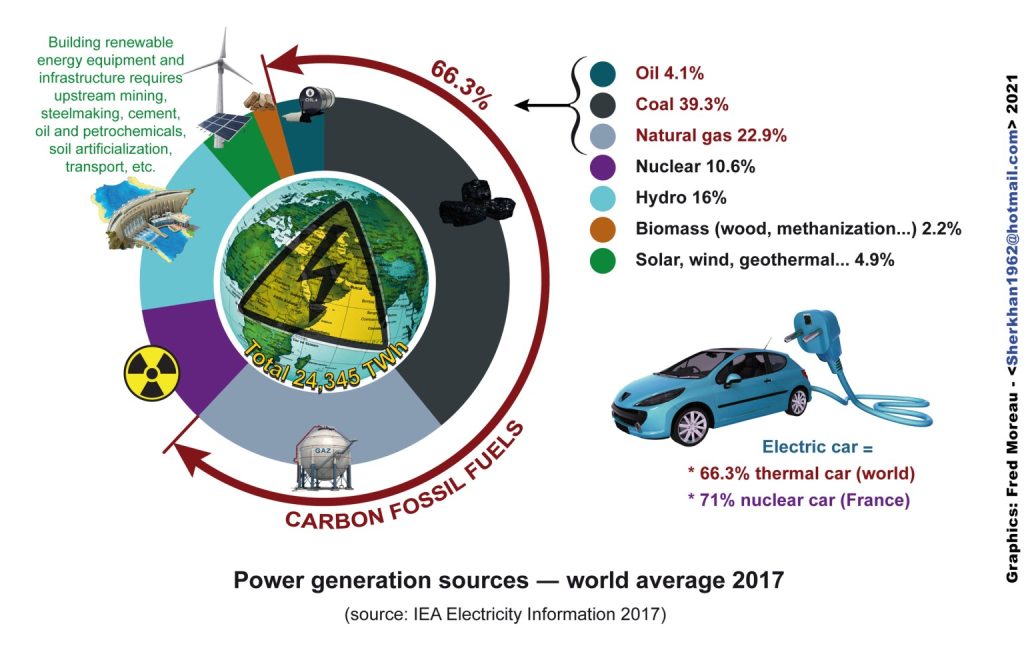

Power generation sources for electric vehicles (Graph by Frederic Moreau)

Lithium is a component of batteries needed for electric cars. For the production of these batteries and electric motors, raw materials are used “that are in any case finite, in many cases already available today with limited reserves, and whose extraction is very often associated with environmental destruction, child labor and overexploitation,” as Winfried Wolf writes in his book Mit dem Elektroauto in die Sackgasse, Warum E-Mobilität den Klimawandel beschleunigt (With the electric vehicle into the impasse, why e-mobility hastens climate change).

What happens behind the scenes of electric mobility, which is touted as “green,” can be seen in the U.S. campaign Protect Thacker Pass. In northern Nevada, a state in the western U.S., resistance is stirring against the construction of an open-pit mine by the Canadian company Lithium Americas, where lithium is to be mined. Here, a small group of activists, indigenous peoples and local residents have united to raise awareness of the destructive effects of lithium mining for electric car batteries and to prevent the lithium mine in the long term with the Protect Thacker Pass campaign.

Thacker Pass is a desert area (also called Peehee muh’huh in the native language of the Northern Paiute) that was originally home to the indigenous peoples of the Northern Paiute, Western Shoshone, and Winnemuca Tribes. The barren landscape is still home to some 300 species of animals and plants, including the endangered Kings River pyrg freshwater snail, jack rabbit, coyote, bighorn sheep, golden eagle, sage grouse, and pronghorn, and is home to large areas of sage brush on which the sage grouse feeds 70-75% of the time, and the endangered Crosby’s buckwheat.

For Lithium Americas, Thacker Pass is “one of the largest known lithium resources in the United States.” The Open-pit mining would break ground on a cultural memorial commemorating two massacres perpetrated against indigenous peoples in the 19th century and before. Evidence of a rich historical heritage is brought there by adjacent caves with burial sites, finds of obsidian processing, and 15,000-year-old petroglyphs. For generations, this site has been used by the Northern Paiute and Western Shoshone tribes for ceremonies, traditional gathering and hunting, and educating young Native people. Now it appears that the history of the colonization of Thacker Pass is repeating itself.

According to research by environmental activists, the lithium mine would lower the water table by 10 meters in one of the driest areas in the U.S., as it is expected to use 6.4 billion gallons of water per year for the next 40 years. This would be certain death for the Kings River pyrg freshwater snail. Mining one ton of lithium generally consumes 1.9 million liters of water at a time when there is a global water shortage.

The mine would discharge uranium, antimony, sulfuric acid and other hazardous substances into the groundwater. This would be a major threat to animal and plant species and also to the local population. Their CO2 emissions would come up to more than 150,000 tons per year, about 2.3 tons of CO2 for every ton of lithium produced. So much for CO2-neutral production! Thanks to a multi-billion dollar advertising industry, mining projects are promoted as sustainable with clever phrases like “clean energy” and “green technology”.

About half of the local indigenous inhabitants are against the lithium mine. The other half are in favor of the project, hoping for a way out of financial hardship through better job opportunities. Lithium Americas’ announcement that it will bring an economic boost to the region sounds promising when you look at the job market there. But there’s no guarantee that working conditions will be fair and jobs will be payed well. According to Derrick Jensen, jobs in the mining industry are highly exploitative and comparable to conditions in slavery.

Oro Verde, The Tropical Forest Foundation, explains: “With the arrival of mining activities, local social structures are also changing: medium-term social consequences include alcohol and drug problems in the mining regions, rape and prostitution, as well as school dropouts and a shift in career choices among the younger generation. Traditional professions or (subsistence) agriculture are no longer of interest to young people. Young men in particular smell big money in the mines, so school dropouts near mines are also very common.”

Seemingly paradoxically, modern industrial culture promotes a rural exodus, which in turn serves as an argument for the construction of mines that harm the environment and people. Indigenous peoples have known for millennia how to be locally self-sufficient and feed their families independently of food imports. This autonomy is being repeatedly snatched away from them.

Erik Molvar, wildlife biologist and chair of the Western Watersheds Project, says of the negative impacts of lithium mining in Thacker Pass that “We have a responsibility as a society to avoid wreaking ecological havoc as we transition to renewable technologies. If we exacerbate the biodiversity crisis in a sloppy rush to solve the climate crisis, we risk turning the Earth into a barren, lifeless ball that can no longer sustain our own species, let alone the complex and delicate web of other plants and animals with which we share this planet.”

We share this planet with nonhuman animal athletes: The jack rabbit has a size of about 50cm (1.6 feet), can reach a speed of up to 60 km/h (37mph) and jump up to six meters (19.7 feet) high from a standing position. In the home of the jack rabbit, 25% of the world’s lithium deposits are about to be mined. To produce one ton of lithium, between 110 and 500 tons of earth have to be moved per day. Since lithium is only present in the clay rock in a proportion of 0.2-0.9%, it is dissolved out of the clay rock with the help of sulfuric acid.

According to the Environmental Impact Statement from the Thacker Pass Mine (EIS), approximately 75 trucks are expected to transport the required sulfur each day to convert it to sulfuric acid in a production facility built on site. This means that 5800 tons of sulfuric acid would be left as toxic waste per day. Sulfur is a waste product of the oil industry. How convenient, then, that the oil industry can simply continue to do “business as usual.”

Nevada Lithium, another company that operates lithium mines in Nevada states: “Electric vehicles (EVs) are here. The production of lithium for the batteries they use is one of the newest and most important industries in the world. China currently dominates the market, and the rest of the world, including the U.S., is now responding to secure its lithium supply.” The demand for lithium is causing its prices to skyrocket: Since the demand for lithium for the new technologies is high and the profit margin is 46% according to Spiegel, every land available will be used to mine lithium.

Lithium production worldwide would have to increase by 400% to meet the growing demand. With this insane growth rate as a goal, Lithium Americas has begun initial construction at Thacker Pass on March 02, 2023. But environmentalists are not giving up, they are holding meetings, educating people about the destructive effects of lithium mining, and taking legal action against the construction of the mine.

Let’s take a look at the production of German electric cars.

Meanwhile, this is the third attempt to bring electric cars to the market in Germany. In the early 20th century, Henry Ford’s internal combustion engine cars replaced electric-powered cars on the roads.

Graph by Frederic Moreau

“In fact, three decades ago, there were similar debates about the electric car as today. In 1991, various models of electric vehicles were produced in Germany and Switzerland,” writes Winfried Wolf. “At that time, it was firmly assumed that the leading car companies would enter into the construction of electric cars on a large scale.”

He goes on to write about a four-year test on the island of Rügen that tested 60 electric cars, including models by VW, Opel, BMW and Daimler-Benz passenger cars from 1992 to 1996. The cost was 60 million Deutsche Mark. The Institute for Energy and Environmental Research (IFEU) in Heidelberg, commissioned by the Federal Ministry of Research, concluded that electric cars consume between 50 percent (frequent drivers) and 400 percent more primary energy per kilometer than comparable cars with internal combustion engines. The test report states that the Federal Environment Agency (UBA) in Berlin also sees its rejection of the electric car strategy confirmed.

There is no talk of these test results in times of our current economic crisis: also German landscapes and its water bodies must make way for a “green” economic policy. We can see the destructive effects of electric car production centers in the example of Grünheide, a town in Brandenburg 30 km from Berlin.

Manu Hoyer, together with other environmentalists in the Grünheide Citizens’ Initiative, rebel against the man who wants to discover life on other planets because the Earth is not enough: Elon Musk. She explains in an article by Frank Brunner in the magazine Natur how Tesla proceeded to build the Gigafactory Berlin-Brandenburg with supposedly 12,000 employees: First, they deforested before there was even a permit, and when it was clear that the electric car factory would be built, Tesla planted new little trees elsewhere as compensation.

The neutral word “deforestation” does not explain the cruel process behind it: Wildlife have their habitat in trees, shrubs and in burrows deep in the earth. In the Natur article, Manu Hoyer recalls that the sky darkened “with ravens waiting to devour the dead animals among the felled trees.”

In the book The Day the World Stops Shopping, J.B. MacKinnon describes, based on a study of clearing in Australia, that the scientific consensus is that the majority, and in some cases all, of the individuals living at a site will die when the vegetation disappears.

It doesn’t sound pretty, but it’s the reality when you read that animals are “crushed, impaled, mauled or buried alive, among other things. They suffer internal bleeding, broken bones or flee into the street where they are run over.” Many would stubbornly resist giving up their habitat.

In this, they are like humans. Nobody gives up her piece of land or his house without a fight when it is taken away from him; animals and humans both love the good life. But the conditions of wild animals play no role in our civil society, they should be available anytime to be exlpoited for our needs.

In order not to incite nature lovers, legal regulations are supposed to lull them into the belief that what is happening here is morally right. Behind this is a calculus by the large corporations, which in return for symbolic gestures can continue the terror against nature blamelessly.

In December 2022, Tesla was granted permission to buy another 100 hectares of forest to expand the car factory site to 400 hectares. The entire site had long been available for new industrial projects, although it is also a drinking water protection area. The Gigafactory uses 1.4 million cubic meters of water annually in a federate state plagued by drought.

Manu Hoyer tells Deutschlandfunk radio that dangerous chemicals are said to have leaked only recently and contaminated firefighting water seeped into the groundwater during a fire last fall. Another environmentalist, Steffen Schorcht, who studied biocybernetics and medical technology, criticizes local politicians for their lethargy in the face of environmental destruction. He sees no other way to fight back than to join forces with other citizens and international organizations outside of politics.

The beneficiaries are not the people who make up the bulk of the population. Tesla cars go to drivers who are happy to spend 57,000€ for a car with a maximum of 535 horsepower.

I can still remember how, as a child, I used to drive with my parents on vacation to the south of France, Italy or Austria in the Citroën 2CV model (two horsepower). Such a car trip was more adventure than luxury, but the experiences during the simple camping vacations in Europe’s nature have remained formative childhood memories.

The author sitting on the hood of a Citroën 2CV in Tuscany, Italy, 1989 (Photo: private)

Today, we have to go a big step further than just living a “simple life” individually. The car industry is pressing the gas pedal, taking the steering wheel out of our hands and driving us into the ditch. It’s time to get out, move our feet and stand up against the car industry.

The BDI, Federation of German Industries, writes in its 2017 position paper on the interlocking of raw materials and trade policy in relation to the technologies of the future that without raw materials there would be no digitalization, no Industry 4.0 and no electromobility. This statement confirms that our western lifestyle can only be financed through the destruction of the last natural habitats on Earth.

The mining of lithium and other so-called “raw materials” for new technologies is related to our culture, which imposes a techno-dystopia on the functioning organism Earth, that nullifies all biological facts. If we want to save the world, it seems to me, we should not become lobbyists for the electric car industry. Rather, we should organize collectively, learn from indigenous peoples, defend the water, the air, the soil, the plants, the wildlife, and everyone we love. The brave environmentalists in Grünheide and Thacker Pass are showing us how.

Homo sapiens have done well without cars for 200,000 years and will continue to do so. All we need is the confidence that our feet will carry us.

Wir fahr’n fahr’n fahr’n auf der Autobahn, Kraftwerk buzzed at the time

as an ode to driving a car

I glide over the asphalt to the points in lonely nature,

give myself a time-out from the confines of the small town

Bus schedules in German villages are an old joke

Buy me a Mercedes Benz, cried Janis Joplin devotedly,

without an expensive car, life is only half as valuable

Car-free Sundays during the oil crisis as a nostalgic anecdote

Driving means freedom and compulsion at the same time, asphalt is forced upon topsoil

with millions of living beings per tablespoon of earth

You must go everywhere: To the supermarket, to school, to work, to the store,

to the club, to friends, and to the trail park

Be yourself! they tell you, but without a car you’re not yourself,

on foot with a lower social status than on wheels

The speed limit dismissed each time, which party stands for the wild nature,

our ancient living room? Don’t vote for them, they deceive too

Believe yourself! they say, but what else can you believe, grown up believing

that this civilization is the only right one

Drive, drive, drive and the airstream flies in your hair –

Freedom, the one moment you have left

Featured image: A view of Thacker Pass by Max Wilbert

by DGR News Service | Feb 10, 2023 | ACTION, Mining & Drilling, Obstruction & Occupation

Editor’s Note: Due to their early adoption of renewables, Germany has been hailed as an example by mainstream environmentalists. The myth that Germany is cutting back on fossil fuel has already been debunked in Bright Green Lies. With their main supplier of fossil fuel going to war with Ukraine, Germany is facing a crisis. They are vying for alternate sources, which they have found under their own soil in Lützerath. They are trying to evacuate a hundred villages to get coal under their ground. In a brave attempt to defend their land, the people are putting up a fight against the German state.

Today’s post consists of three separate pieces. The first is a Common Dreams piece covering police brutality against the local communities. The second is a firsthand account of one of those many protestors who joined the local villagers in fighting the German state. This account explores the need for training and militant resistance to industrial civilization. The post finally culminates in an excerpt from Derrick Jensen’s Endgame.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Deep Green Resistance, the News Service or its staff.

“The most affected people are clear, the science is clear, we need to keep the carbon in the ground,” said Greta Thunberg at the protest.

By Julia Conley / CommonDreams

The way was cleared for the complete demolition of the German village of Lützerath and the expansion of a coal mine on Monday after the last two anti-coal campaigners taking part in a dayslong standoff with authorities left the protest site.

The two activists—identified in media reports by their nicknames, “Pinky” and “Brain”—spent several days in a tunnel they’d dug themselves as thousands of people rallied in the rain over the weekend and hundreds occupied the village, which has been depopulated over the last decade following a constitutional court ruling in favor of expanding a nearby coal mine owned by energy firm RWE.

As Pinky and Brain left the 13-foot deep tunnel, which police in recent days have warned could collapse on them contrary to assessments by experts, other campaigners chainedthemselves to a digger and suspended themselves from a bridge to block access to Lützerath, but those demonstrations were also halted after several hours.

Protesters and their supporters have condemned the actions of law enforcement authorities in the past week as police have violently removed people from the site, including an encampment where about 100 campaigners have lived for more than two years to protest the expansion of RWE’s Garzweiler coal mine.

The vast majority of protesters were peaceful during the occupation. German Interior Minister Nancy Fraeser said Monday that claims of police violence would be investigated while also threatening demonstrators with prosecution if they were found to have attacked officers.

“If the allegations are confirmed then there must be consequences,” said Fraeser.

Fridays for Future leader Greta Thunberg joined the demonstrators last week, condemning the government deal with RWE that allowed the destruction of Lützerath as “shameful” before she was also forcibly removed from the site on Sunday.

“Germany is really embarrassing itself right now,” Thunberg said Saturday of the plan to move forward with the demolition of the village, as thousands of people joined the demonstration. “I think it’s absolutely absurd that this is happening the year 2023. The most affected people are clear, the science is clear, we need to keep the carbon in the ground.”

“When governments and corporations are acting like this, are actively destroying the environment, putting countless of people at risk, the people step up,” she added.

Campaigners have warned that the expansion of the Garzweiler coal mine will make it impossible for Germany to meet its obligation to reduce carbon emissions and have condemned the government, including the Green Party, for its agreement with RWE. Under the deal, the deadline for coal extraction in Germany was set at 2030.

RWE’s mine currently produces 25 million tonnes of lignite, also known as brown coal, per year.

Extinction Rebellion demonstrators in the Netherlands said last week that the protest in the village “is not so much about preserving Lützerath itself.”

“It symbolizes resistance to everything that has to make way for fossil energy while humanity is already on the edge of the abyss due to CO2 emissions,” said the group.

“The people in power will not disappear voluntarily; giving flowers to the cops just isn’t going to work. This thinking is fostered by the establishment; they like nothing better than love and nonviolence. The only way I like to see cops given flowers is in a flower pot from a high window.” — William S. Burroughs

By Agent Eagle

I

Thousands of people storming a village occupied by police. It was not the revolution, but it was close.

A demonstration had been announced for January 14, a Saturday, in Keyenberg, which is next to Lützerath, Germany. Underneath the villages and their fertile loess soil lies lignite. The German government, the world’s number one lignite miner with 140 million tons extracted a year, dispossessed the residents of approximately 100 villages around the strip mine Garzweiler 2 utilizing laws from Nazi Germany. The police occupy and defend the area that is now in the possession of the energy firm RWE from the people.

Despite attempts at forced evacuation, a couple of activists were still holding out in Lützerath, underground or in the trees. However, since the police had disbanded their community kitchen and thrown out all paramedics, their time was running out.

Therefore, on Saturday, we knew we would make a last attempt at reoccupying the village.

The weather was stormy, which was an advantage in the end because it disabled armored water cannon trucks. The mud was sticky. The rain was heavy. There were police around the entire village, police along the horizon, police as far as the eye can see. Yet thousands of people marched to Lützerath despite the police doing everything they could to prevent us from doing so by using tear gas, batons, riot shields, dogs, horses, anti-riot water cannons, a helicopter and military tactics. It was a siege that began when one of the people organizing the legal demo told us to ignore the police and go for the village.

A group of hooded activists in black marched right through the police lines, throwing smoke bombs and shooting fireworks. Of around 35,000 people, approximately 5,000-10,000 joined in, but we progressively kept losing more on the way to Lützerath. We advanced by taking land and by breaking through police lines, for example by distracting the police, so we could push through elsewhere. Then the police rearranged and it all began anew. It took 6-7 hours to even get to the village.

By then it was almost dawn. Most of the people were deciding to turn around.

The police managed to surround the entire village. They had erected two special fences around the village and the surrounding woods. They had also built a road through the strip mine, so they could bring in ordnance while they prevented all of our vehicles from getting through.

***

II

Lützerath leaves an impression. A mark on the consciousness of the people. Some are confronted with the violence of the machine for the very first time. The lifeless bodies of protestants being dragged through the mud by policemen. Running and panicked screams. A heavily armed policeman coming at you, swinging his baton, bellowing, hitting you in the face, despite you raising your arms. In such a moment you become fully conscious of the absurdity and brutality of a system that does not protect you but the interests of a company tearing the life from this very earth. You notice you do not have a weapon because somebody told you that you were prohibited from carrying one. But he does, and he is using it.

You also see the people coming together to lift a woman in a wheelchair over an earth wall. You see the crowd forming a protective circle, shouting and pulling on a policeman who is pushing a screaming woman. I felt something very special that is hard to describe. A solidarity that does not need words.

***

III

Over a hundred people were hurt, some severely. The police won, the area was evacuated and flattened in the cruelest way possible. Landmarks that were supposed to go to museums were destroyed. Still, some people are holding out to slow down the monstrous rotary excavator. If RWE manages to mine just one quarter of the amount of lignite it plans to mine, if Lützerath falls, the earth will warm more than 1.5°.

The reason we failed in the end was not hunger. Nor exhaustion. Nor lack of equipment. The reason we failed was morale. Morale was, of course, low from hours of wading through mud and static battles with the police, but people can push through hardships and overcome fear. For this, they need motivation. That could look like a leader giving them a goal and pointing them in the right direction, or knowing that reinforcement is on the way.

What we would have needed was a detailed plan, experience and more structure. A tighter, more responsive form of organization led by people with an iron will. Numbers can only do so much. If he has a weapon, and is willing to use it, and you do not have a weapon and you are not willing to take risks, then he wins. More militant activists led the push, and most of them were carried off by police fairly early on.

I believe the “activisti,” as they are called here, would have profited from training. For example, many people were too timid to effectively advance, so what would have helped is a kind of military structure with leaders and strategically positioned militant activists.

If we could do it again, I would make sure we would have brought the right equipment along and that the people who knew how to carry and use it were protected until arriving at the fence. In Germany, you are not allowed to bring “protective weapons” to demonstrations, meaning any kind of armor to protect you from police violence. I would have disregarded that. In the deciding moment of this battle, right before the fence, I would have given people shields and armor that a group would have carried up until then and I would have told them to shield the people breaking into the fence.

I would have brought smoke grenades, balloons and water guns filled with colorful paint and pepper spray and maybe even a truck with a hose mounted on top to send the police into chaos. We could have made a coordinated effort to storm into their rows and to disarm them, put bags over their heads, use the pepper spray, colors and flash grenades to blind them and tie them up.

We could have notified people of our plans without alerting police via messenger groups.

We could have driven a truck into the outer fence, maybe put wooden planks over the gap between the fences and climbed over it.

We could have used drones to scout and carrier drones to bring supplies.

We could have stormed the perimeter and disabled or even taken over the water cannon truck.

In the ensuing confusion we could have brought in material for barricades. The fences would have worked to our advantage: we would have barricaded ourselves inside and around it. At night, we would have laid down bricks and spikes to keep the police from bringing in reinforcements. We could have sabotaged the police cars that were already there — it is easy to pop their tires. Or we could have taken them, crashed them and used them for the barricades. People in the very densely populated Ruhrgebiet could have sabotaged police stations and laid fires the whole night to keep the police busy. We could have held our position until morning.

For all of this, we would have needed high amounts of coordination and structure and also morale to keep it coming. Everyone would have needed to lose their fear of state violence and to fight till the bitter end.

Agent Eagle is a German radical feminist and an environmental activist.

By Derrick Jensen/Endgame

“Some failures to act at the right time with the right tactic (violent or nonviolent) may set movements back or move them forward. The trick is knowing when and how to act. Well, that’s the first trick. The real trick is kicking aside our fear and acting on what we already know (because, truly, we depend on those around us, and they are dying because they depend on us, too).

I asked a friend what he thought is meant by the phrase, ‘Every act of violence sets back the movement ten years.’

He responded, ‘More often than not, before I say anything radical or militant at all in any sort of public forum, I wonder who is taking in my words. And I wonder what will be the consequences if I say something that may threaten the worldview of those in power.’

He paused, then continued, ‘I think identity has a lot to do with resistance to violent acts. It’s pretty apparent to us all at a very early age that you’re absolutely forbidden by the master to use the ‘tools of the master to destroy the master’s house.’ Imagine a child who is routinely beaten with a two-by-four, who one day picks it up and fights back. Imagine especially what happens to this child if he’s not yet big enough to effectively fight back, to win. Not good. On the larger scale I don’t think many people are willing to identify themselves with these types of acts or with anyone willing to commit these types of acts simply because it is forbidden by those in power and therefore to be feared.’

Another short pause, and then he concluded, ‘The way I see it, the phrase about setting the movement back is coming from a place of fear. It surely can’t be coming from the perspective of successful pacifist resistance to the machine. If it did, we wouldn’t be here discussing how to stop the atrocities committed by this culture.’

Near the end of our book Welcome to the Machine: Science, Surveillance, and the Culture of Control, George Draffan and I wrote, ‘A high-ranking security chief from South Africa’s apartheid regime later told an interviewer what had been his greatest fear about the rebel group African National Congress (ANC). He had not so much feared the ANC’s acts of sabotage or violence — even when these were costly to the rulers — as he had feared that the ANC would convince too many of the oppressed majority of Africans to disregard ‘law and order.’ Even the most powerful and highly trained ‘security forces’ in the world would not, he said, have been able to stem that threat.’

As soon as we come to see that the edicts of those in power are no more than the edicts of those in power, that they carry no inherent moral or ethical weight, we become the free human beings we were born to be, capable of saying yes and capable of saying no.”

Endgame, Derrick Jensen

Photo by Markus Spiske on Unsplash

by DGR News Service | Jan 3, 2020 | Movement Building & Support

This excerpt from Chapter 4 of the book Deep Green Resistance: Strategy to Save the Planet was written by Lierre Keith. Click the link above to purchase the book or read online for free.

Tell me, what is it you plan to do

with your one wild and precious life?

—Mary Oliver, poet

The culture of the left needs a serious overhaul. At our best and bravest moments, we are the people who believe in a just world; who fight the power with all the courage and commitment that women and men can possess; who refuse to be bought or beaten into submission, and refuse equally to sell each other out. The history of struggles for justice is inspiring, ennobling even, and it should encourage us to redouble our efforts now when the entire world is at stake. Instead, our leadership is leading us astray. There are historic reasons for the misdirection of many of our movements, and we would do well to understand those reasons before it’s too late.1

The history of misdirection starts in the Middle Ages when various alternative sects arose across Europe, some more strictly religious, some more politically utopian. The Adamites, for instance, originated in North Africa in the second century, and the last of the Neo-Adamites were forcibly suppressed in Bohemia in 1849.2 They wanted to achieve a state of primeval innocence from sin. They practiced nudism and ecstatic rituals of rebirth in caves, rejected marriage, and held property communally. Groups such as the Diggers (True Levelers) were more political. They argued for an egalitarian social structure based on small agrarian communities that embraced ecological principles. Writes one historian, “They contended that if only the common people of England would form themselves into self-supporting communes, there would be no place in such a society for the ruling classes.”3

Not all dissenting groups had a political agenda. Many alternative sects rejected material accumulation and social status but lacked any clear political analysis or egalitarian program. Such subcultures have repeatedly arisen across Europe, coalescing around a common constellation of themes:

■ A critique of the dogma, hierarchy, and corruption of organized religion;

■ A rejection of the moral decay of urban life and a belief in the superiority of rural life;

■ A romantic or even sentimental appeal to the past: Eden, the Golden Age, pre-Norman England;

■ A millenialist bent;

■ A spiritual practice based on mysticism; a direct rather than mediated experience of the sacred. Sometimes this is inside a Christian framework; other examples involve rejection of Christianity. Often the spiritual practices include ecstatic and altered states;

■ Pantheism and nature worship, often concurrent with ecological principles, and leading to the formation of agrarian communities;

■ Rejection of marriage. Sometimes sects practice celibacy; others embrace polygamy, free love, or group marriage.

Within these dissenting groups, there has long been a tension between identifying the larger society as corrupt and naming it unjust. This tension has been present for over 1,000 years. Groups that critique society as degenerate or immoral have mainly responded by withdrawing from society. They want to make heaven on Earth in the here and now, abandoning the outside world. “In the world but not of it,” the Shakers said. Many of these groups were and are deeply pacifistic, in part because the outside world and all things political are seen as corrupting, and in part for strongly held moral reasons. “Corruption groups” are not always leftist or progressive. Indeed, many right-wing and reactionary elements have formed sects and founded communities. In these groups, the sin in urban or modern life is hedonism, not hierarchy. In fact, these groups tend to enforce strict hierarchy: older men over younger men, men over women. Often they have a charismatic leader and the millenialist bent is quite marked.

“Justice groups,” on the other hand, name society as inequitable rather than corrupt, and usually see organized religion as one more hierarchy that needs to be dismantled. They express broad political goals such as land reform, pluralistic democracy, and equality between the sexes. These more politically oriented spiritual groups walk the tension between withdrawal and engagement. They attempt to create communities that support a daily spiritual practice, allow for the withdrawal of material participation in unjust systems of power, and encourage political activism to bring their New Jerusalem into being. Contemporary groups like the Catholic Workers are attempts at such a project.

This perennial trend of critique and utopian vision was bolstered by Romanticism, a cultural and artistic movement that began in the latter half of the eighteenth century in Western Europe. It was at least partly a reaction against the Age of Enlightenment, which valued rationality and science. The image of the Enlightenment was the machine, with the living cosmos reduced to clockwork. As the industrial revolution gained strength, rural lifeways were destroyed while urban areas swelled with suffering and squalor. Blake’s dark, Satanic mills destroyed rivers, the commons of wetlands and forests fell to the highest bidder, and coal dust was so thick in London that the era could easily be deemed the Age of Tuberculosis. In Germany, the Rhine and the Elbe were killed by dye works and other industrial processes. And along with natural communities, human communities were devastated as well.

Romanticism revolved around three main themes: longing for the past, upholding nature as pure and authentic, and idealizing the heroic and alienated individual. Germany, where elements of an older pagan folk culture still carried on, was in many ways the center of the Romantic movement.

How much of this Teutonic nature worship was really drawn from surviving pre-Christian elements, and how much was simply a Romantic recreation—the Renaissance Faire of the nineteenth century—is beyond the scope of this book. Suffice it to say, there were enough cultural elements for the Romantics to build on.

In 1774, German writer Goethe penned the novel The Sorrows of Young Werther, the story of a young man who visits an enchanting peasant village, falls in love with an unattainable young woman, and suffers to the point of committing suicide. The book struck an oversensitive nerve, and, overnight, young men across Europe began modeling themselves on the protagonist, a depressive and passionate artist. Add to this the supernatural and occult elements of Edgar Allan Poe’s work, and, by the nineteenth century, the Romantics of that day resembled modern Goths. A friend of mine likes to say that history is same characters, different costumes—and in this case the costumes haven’t even changed much.4

Another current of Romanticism that eventually influenced our current situation was bolstered by philosopher Jean Jacques Rosseau,5 who described a “state of nature” in which humans lived before society developed. He was not the creator of the image of the noble savage—that dubious honor falls to John Dryden, in his 1672 play The Conquest of Granada. Rousseau did, however, popularize one of the core components that would coalesce into the cliché, arguing that there was a fundamental rupture between human nature and human society. The concept of such a divide is deeply problematical, as by definition it leaves cultures that aren’t civilizations out of the circle of human society. Whether the argument is for the bloodthirsty savage or the noble savage, the underlying concept of a “state of nature” places hunter-gatherers, horticulturalists, nomadic pastoralists, and even some agriculturalists outside the most basic human activity of creating culture. All culture is a human undertaking: there are no humans living in a “state of nature.”6 With the idea of a state of nature, vastly different societies are collapsed into an image of the “primitive,” which exists unchanging outside of history and human endeavor.

Indeed, one offshoot of Romanticism was an artistic movement called Primitivism that inspired its own music, literature, and art. Romanticism in general and Primitivism in particular saw European culture as overly rational and repressive of natural impulses. So-called primitive cultures, in contrast, were cast as emotional, innocent and childlike, sexually uninhibited, and at one with the natural world. The Romantics embraced the belief that “primitives” were naturally peaceful; the Primitivists tended to believe in their proclivity to violence. Either cliché could be made to work because the entire image is a construct bearing no relation to the vast variety of forms that indigenous human cultures have taken. Culture is a series of choices—political choices made by a social animal with moral agency. Both the noble savage and the bloodthirsty savage are objectifying, condescending, and racist constructs.

Romanticism tapped into some very legitimate grievances. Urbanism is alienating and isolating. Industrialization destroys communities, both human and biotic. The conformist demands of hierarchical societies leave our emotional lives inauthentic and numb, and a culture that hates the animality of our bodies drives us into exile from our only homes. The realization that none of these conditions are inherent to human existence or to human society can be a profound relief. Further, the existence of cultures that respect the earth, that give children kindness instead of public school, that share food and joy in equal measure, that might even have mystical technologies of ecstasy, can serve as both an inspiration and as evidence of the crimes committed against our hearts, our culture, and our planet. But the places where Romanticism failed still haunt the culture of the left today and must serve as a warning if we are to build a culture of resistance that can support a true resistance movement.

In Germany, the combination of Romanticism and nationalism created an upswell of interest in myths. They spurred a widespread longing for an ancient or even primordial connection with the German landscape. Youth are the perennially disaffected and rebellious, and German youth in the late nineteenth century coalesced into their own counterculture. They were called Wandervogel or wandering spirits. They rejected the rigid moral code and work ethic of their bourgeois parents, romanticized the image of the peasant, and wandered the countryside with guitars and rough-spun tunics. The Wandervogel started with urban teachers taking their students for hikes in the country as part of the Lebensreform (life reform) movement. This social movement emphasized physical fitness and natural health, experimenting with a range of alternative modalities like homeopathy, natural food, herbalism, and meditation. The Lebensreform created its own clinics, schools, and intentional communities, all variations on a theme of reestablishing a connection with nature. The short hikes became weekends; the weekends became a lifestyle. The Wandervogel embraced the natural in opposition to the artificial: rural over urban, emotion over rationality, sunshine and diet over medicine, spontaneity over control. The youth set up “nests” and “antihomes” in their towns and occupied abandoned castles in the forests. The Wandervogel was the origin of the youth hostel movement. They sang folk songs; experimented with fasting, raw foods, and vegetarianism; and embraced ecological ideas—all before the year 1900. They were the anarchist vegan squatters of the age.

Environmental ideas were a fundamental part of these movements. Nature as a spiritual source was fundamental to the Romantics and a guiding principle of Lebensreform. Adolph Just and Benedict Lust were a pair of doctors who wrote a foundational Lebensreform text, Return to Nature, in 1896. In it, they decried,

Man in his misguidance has powerfully interfered with nature. He has devastated the forests, and thereby even changed the atmospheric conditions and the climate. Some species of plants and animals have become entirely extinct through man, although they were essential in the economy of Nature. Everywhere the purity of the air is affected by smoke and the like, and the rivers are defiled. These and other things are serious encroachments upon Nature, which men nowadays entirely overlook but which are of the greatest importance, and at once show their evil effect not only upon plants but upon animals as well, the latter not having the endurance and power of resistance of man.7

Alternative communities soon sprang up all over Europe. The small village of Ascona, Switzerland, became a countercultural center between 1900 and 1920. Experiments involved “surrealism, modern dance, dada, Paganism, feminism, pacifism, psychoanalysis and nature cure.”8 Some of the figures who passed through Ascona included Carl Jung, Isadora Duncan, Mikhail Bakunin, Peter Kropotkin, Vladimir Lenin, Leon Trotsky, and an alcoholic Herman Hesse seeking a cure. Clearly, social change—indeed, revolution—was one of the ideas on the table at Ascona. This chaos of alternative spiritual, cultural, and political trends began to make its way to the US. On August 20, 1903, for instance, an anarchist newspaper in San Francisco published a long article describing the experiments underway at Ascona.

As we will see, the connections between the Lebensreform, Wandervogel youth, and the 1960s counterculture in the US are startlingly direct. German Eduard Baltzer wrote a lengthy explication of naturliche lebensweise (natural lifestyle) and founded a vegetarian community. Baltzer-inspired painter Karl Wihelm Diefenbach, who also started a number of alternative communities and workshops dedicated to religion, art, and science, all based on Lebensreform ideas. Artists Gusto Graser and Fidus pretty well created the artistic style of the German counterculture in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Viewers of their work would be forgiven for thinking that their paintings of psychedelic colors, swirling floraforms, and naked bodies embracing were album covers circa 1968. Fidus even used the iconic peace sign in his art.

Graser was a teacher and mentor to Herman Hesse, who was taken up by the Beatniks. Siddhartha and Steppenwolf were written in the 1920s but sold by the millions in the US in the 1960s. Declares one historian, “Legitimate history will always recount Hesse as the most important link between the European counter-culture of his [Hesse’s] youth and their latter-day descendants in America.”9

Along with a few million other Europeans, some of the proponents of the Wandervogel and Lebensreform movements immigrated to the United States at the beginning of the twentieth century. The most famous of these Lebensreform immigrants was Dr. Benjamin Lust, deemed the Father of Naturopathy, quoted previously. Write Gordon Kennedy and Kody Ryan, “Everything from massage, herbology, raw foods, anti-vivisection and hydro-therapy to Eastern influences like Ayurveda and Yoga found their way to an American audience through Lust.”10 In Return To Nature, he railed against water and air pollution, vivisection, vaccination, meat, smoking, alcohol, coffee, and public schooling. Any of this sound a wee bit familiar? Gandhi, a fan, was inspired by Lust’s principles to open a Nature Cure clinic in India.

The emphasis on sunshine and naturism led many of these Lebensreform immigrants to move to warm, sunny California and Florida. Sun worship was embraced as equal parts ancient Teutonic religion, health-restoring palliative, and body acceptance. It was much easier to live outdoors and scrounge for food where the weather never dropped below freezing. Called Nature Boys, naturemensch, and modern primitives, they set up camp and began attracting followers and disciples. German immigrant Arnold Ehret, for instance, wrote a number of books on fasting, raw foods, and the health benefits of nude sunbathing, books that would become standard texts for the San Francisco hippies. Gypsy Boots was another direct link from the Lebensreform to the hippies. Born in San Francisco, he was a follower of German immigrant Maximillian Sikinger. After the usual fasting, hiking, yoga, and sleeping in caves, he opened his “Health Hut” in Los Angeles, which was surprisingly successful. He was also a paid performer at music festivals like Monterey and Newport in 1967 and 1968, appearing beside Jefferson Airplane, Jimi Hendrix, and the Grateful Dead. Carolyn Garcia, Jerry’s wife, was apparently a big admirer. Boots was also in the cult film Mondo Hollywood with Frank Zappa.

The list of personal connections between the Wandervogel Nature Boys and the hippies is substantial, and makes for an unbroken line of cultural continuity. But before we turn to the 1960s, it’s important to examine what happened to the Lebensreform and Wandervogel in Germany with the rise of Nazism.

This is not easy to do. Fin de siècle Germany was a tumult of change and ideas, pulling in all directions. There was a huge and politically powerful socialist party, the Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (Social Democratic Party of Germany), or SPD, which one historian called “the pride of the Second International.”11 In 1880, it garnered more votes than any other party in Germany, and, in 1912, it had more seats in Parliament than any other party. It helped usher in the first parliamentary democracy, including universal suffrage, and brought a shorter workday, legal workers’ councils in industry, and a social safety net. To these serious activists, the Wandervogel and Lebensreform, especially “the more manifestly idiotic of these cults,”12 were fringe movements. To state the obvious, the constituents of SPD were working-class and poor people concerned with survival and justice, while the Lebensreform, with their yoga, spiritualism, and dietary silliness, were almost entirely middle class.

Here we begin to see these utopian ideas take a sinister turn. The seeds of contradiction are easy to spot in the völkisch movement entry on Wikipedia, which states, “The völkisch movement is the German interpretation of the populist movement, with a romantic focus on folklore and the ‘organic.’ . . . In a narrow definition it can be used to designate only groups that consider human beings essentially preformed by blood, i.e. inherited character.”

Immediately, there are problems. The völkisch is marked with a Nazi tag. One Wikipedian writes, “Personally I consider it offensive to claim that an ethnic definition of ‘Folk’ equals Nationalism and/or Racism.” Another Wikipedian points out that the founders of the völkisch concept were leftist thinkers. Another argues, “With regard to its origins . . . the völkisch idea is wholeheartedly non-racist, and people like Landauer and Mühsam (the leading German anarchists of their time) represented a continuing current of völkisch anti-racism. It’s understandable if the German page focuses on the racist version—a culture of guilt towards Romanticism seems to be one of Hitler’s legacies—but these other aspects need to be looked at too.”13

Who is correct? Culture, ethnicity, folklore, and nationalism are all strands that history has woven into the word. But völk does have a first philosopher, Johann Gottfried von Herder, who founded the whole idea of folklore, of a culture of the common people that should be valued, not despised. He urged Germans to take pride in their language, stories, art, and history. The populist appeal in his ideas—indeed, their necessity to any popular movement—may seem obvious to us 200 years later, but at the time this valuing of a people’s culture was new and radical. His personal collection of folk poetry inspired a national hunger for folklore; the brothers Grimm were one direct result of Herder’s work. He also argued that everyone from the king to the peasants belonged to the völk, a serious break with the ruling notion that only the nobility were the inheritors of culture and that that culture should emulate classical Greece. He believed that his conception of the völk would lead to democracy and was a supporter of the French Revolution.

Herder was very aware of where the extremes of nationalism could lead and argued for the full rights of Jews in Germany. He rejected racial concepts, saying that language and culture were the distinctions that mattered, not race, and asserted that humans were all one species. He wrote, “No nationality has been solely designated by God as the chosen people of the earth; above all we must seek the truth and cultivate the garden of the common good.”14

Another major proponent of leftist communitarianism was Gustav Landauer, a Jewish German. He was one of the leading anarchists through the Wilhelmine era until his death in 1919 when he was arrested by the Freikorps and stoned to death. He was a mystic as well as being a political writer and activist. His biographer, Eugene Lunn, describes Landauer’s ideas as a “synthesis of völkisch romanticism and libertarian socialism,” hence, “romantic socialism.”15 He was also a pacifist, rejecting violence as a means to revolution both individually and collectively. His belief was that the creation of libertarian communities would “gradually release men and women from their childlike dependence upon authority,” the state, organized religion, and other forms of hierarchy.16 His goal was to build “radically democratic, participatory communities.”17

Landauer spoke to the leftist writers, artists, intellectuals, and youths who felt alienated by modernity and urbanism and expressed a very real need—emotional, political, and spiritual—for community renewal. He had a full program for the revolutionary transformation of society. Rural communes were the first practical step toward the end of capitalism and exploitation. These communities would form federations and work together to create the infrastructure of a new society based on egalitarian principles. It was an A to B plan that never lost sight of the real conditions of oppression under which people were living. After World War I, roughly one hundred communes were formed in Germany, and, of those, thirty were politically leftist, formed by anarchists or communists. There was also a fledgling women’s commune movement whose goal was an autonomous feminist culture, similar to the contemporary lesbian land movement in the US.

Where did this utopian resistance movement go wrong? The problem was that it was, as historian Peter Weindling puts it, “politically ambivalent.”18 Writes Weindling, “The outburst of utopian social protest took contradictory artistic, Germanic volkish, or technocratic directions.”19 Some of these directions, unhitched from a framework of social justice, were harnessed by the right, and ultimately incorporated into Nazi ideology. Lebensreform activities like hiking and eating whole-grain bread were seen as strengthening the political body and were promoted by the Nazis. “A racial concept of health was central to National Socialism,” writes Weindling. Meanwhile, Jews, gays and lesbians, the mentally ill, and anarchists were seen as “diseases” that weakened the Germanic race as a whole.

Ecological ideas were likewise embraced by the Nazis. The health and fitness of the German people—a primary fixation of Nazi culture—depended on their connection to the health of the land, a connection that was both physical and spiritual. The Nazis were a peculiar combination of the Romantic and the Modern, and the backward-looking traditionalist and the futuristic technotopians were both attracted to their ideology. The Nazi program was as much science as it was emotionality. Writes historian David Blackborn,

National socialism managed to reconcile, at least theoretically, two powerful and conflicting impulses of the later nineteenth century, and to benefit from each. One was the infatuation with the modern and the technocratic, where there is evident continuity from Wilhelmine Germany to Nazi eugenicists and Autobahn builders; the other was the “cultural revolt” against modernity and machine-civilization, pressed into use by the Nazis as part of their appeal to educated élites and provincial philistines alike.20

Let’s look at another activist of the time, one who was political. Erich Mühsam, a German Jewish anarchist, was a writer, poet, dramatist, and cabaret performer. He was a leading radical thinker and agitator during the Weimar Republic, and won international acclaim for his dramatic work satirizing Hitler. He had a keen interest in combining anarchism with theology and communal living, and spent time in the alternative community of Ascona. Along with many leftists, he was arrested by the Nazis and sent to concentration camps in Sonnenburg, Brandenburg, and finally Oranienburg. Intellectuals around the world protested and demanded Mühsam’s release, to no avail. When his wife Zenzl was allowed to visit him, his face was so bruised she didn’t recognize him. The guards beat and tortured him for seventeen months. They made him dig his own grave. They broke his teeth and burned a swastika into his scalp. Yet when they tried to make him sing the Nazi anthem, he would sing the International instead. At his last torture session, they smashed in his skull and then killed him by lethal injection. They finished by hanging his body in a latrine.

The intransigent aimlessness and anemic narcissism of so much of the contemporary counterculture had no place beside the unassailable courage and sheer stamina of this man. Sifting through this material, I will admit to a certain amount of despair: between the feckless and the fascist, will there ever be any hope for this movement? The existence of Erich Mühsam is an answer to embrace. Likewise, reading history backwards, so that Nazis are preordained in the völkish idea, is insulting to the inheritors of this idea who resisted Fascism with Mühsam’s fortitude. There were German leftists who fought for radical democracy and justice, not despite their communitarianism, but with it.

Our contemporary environmental movement has much to learn from this history. Janet Biehl and Peter Staudenmaier, in their book Ecofascism: Lessons from the German Experience,21 explore the idea that fascism or other reactionary politics are “perhaps the unavoidable trajectory of any movement which acknowledges and opposes social and ecological problems but does not recognize their systemic roots or actively resist the political and economic structures which generate them. Eschewing societal transformation in favor of personal change, an ostensibly apolitical disaffection can, in times of crisis, yield barbaric results.”22

The contemporary alterna-culture won’t result in anything more sinister than silliness; fascism in the US is most likely to come from actual right-wing ideologues mobilizing the resentments of the disaffected and economically stretched mainstream, not from New Age workshop hoppers. And friends of Mary Jane aren’t known for their virulence against anything besides regular bathing. German immigrants brought the Lebensreform and Wandervogel to the US, and it didn’t seed a fascist movement here. None of this leads inexorably to fascism. But we need to take seriously the history of how ideas which we think of as innately progressive, like ecology and animal rights, became intertwined with a fascist movement.

An alternative culture built around the project of an individualistic and interior experience, whether spiritual or psychological, cannot create a resistance movement, no matter how many societal conventions it trespasses. Indeed, the Wandervogel manifesto stated, “We regard with contempt all who call us political,”23 and their most repeated motto was “Our lack of purpose is our strength.” But as Laqueur points out,

Lack of interest in public affairs is not civic virtue, and . . . an inability to think in political categories does not prevent people from getting involved in political disaster . . . The Wandervogel . . . completely failed. They did not prepare their members for active citizenship. . . . Both the socialist youth and the Catholics had firmer ground under their feet; each had a set of values to which they adhered. But in the education of the free youth movement there was a dangerous vacuum all too ready to be filled by moral relativisim and nihilism.24

We are facing another disaster, and if we fail there will be no future to learn from our mistakes. That same “lack of interest”—often a stance of smug alienation—is killing our last chance of resistance. We are not preparing a movement for active citizenship and all that implies—the commitment, courage, and sacrifice that real resistance demands. There is no firm moral ground under the feet of those who can only counsel withdrawal and personal comfort in the face of atrocity. And the current Wandervogel end in nihilism as well, repeating that it’s over, we can do nothing, the human race has run its course and the bacteria will inherit the earth. The parallels are exact. And the outcome?

The Wandervogel marched off to World War I, where they “perished in Flanders and Verdun.”25 Of those who returned from the war, a small, vocal minority became communists. A larger group embraced right-wing protofascist groups. But the largest segment was apolitical and apathetic. “This was no accidental development,” writes Laqueur.26

The living world is now perishing in its own Flanders and Verdun, a bloody, senseless pile of daily species. Today there are still wood thrushes, small brown angels of the deep woods. Today there are northern leopard frogs, but only barely. There may not be Burmese star tortoises, with their shells like golden poinsettias; the last time anyone looked—for 400 hours with trained dogs—they only found five. If the largest segment of us remains apolitical and apathetic, they we’ll all surely die.

Part II will be published next week. For references, visit this link to read the book Deep Green Resistance: Strategy to Save the Planet online or to purchase a copy.

by DGR News Service | Jan 5, 2019 | Movement Building & Support

Coming to a political consciousness is not a painless task. To overcome denial means facing the everyday, normative cruelty of a whole society, a society made up of millions of people who are participating in that cruelty, and if not directly, then as bystanders with benefits. A friend of mine who grew up in extreme poverty recalled becoming politicized during her first year in college, a year of anguish over the simple fact that “there were rich people and there were poor people, and there was a relationship between the two.” You may have to face full-on the painful experiences you denied in order to survive, and even the humiliation of your own collusion. But knowledge of oppression starts from the bedrock that subordination is wrong and resistance is possible. The acquired skill of analysis can be psychologically and even spiritually freeing.

– Lierre Keith

by Stroke

Strictly speaking, all of my problems, the whole drama of my life and suffering, can be summarized in one word: poverty.

From birth, it seems to have been my destiny, the element that determines my life the most. I really don’t want to see myself as a victim. But I can no longer accept the widespread opinion (one could also call it dominant ideology) that everyone is responsible for his or her own destiny; that everyone can make it, if he or she only strives and works hard enough. Because this is simply wrong.

I have tried seriously for many years to gain a foothold in the world of work. I am smart, educated, have a well-groomed appearance, and two academic degrees. But it’s not my fault.

My “mistake” was merely to enter the “labour market” shortly after the introduction of Gerhard Schroeder’s Agenda 2010 and the associated Hartz “reforms”.

What the poor need to understand, is that poverty is a political goal, because poverty is a fundamental pillar of capitalism.

Money, at least in theory, is nothing more than a means of exchange. But as it is used in reality, it is an ideological instrument of power with a quasi-religious character which is used with increasing brutality.

As Max Wilbert writes in a recent interview, “The world today is being run by people who believe in money as a god. They’re insane, but they have vast power, and they’re using that power in the real world. That’s the physical manifestation of their violent, corrupt ideology.”

In his book Endgame, the writer Derrick Jensen radically deconstructs the “religion” of money. He writes: “There are no rich people in the world, and there are no poor people. There are just people. The rich may have lots of pieces of green paper that many pretend are worth something—or their presumed riches may be even more abstract: numbers on hard drives at banks—and the poor may not. These “rich” claim they own land, and the “poor” are often denied the right to make that same claim. A primary purpose of the police is to enforce the delusions of those with lots of pieces of green paper. Those without the green papers generally buy into these delusions almost as quickly and completely as those with. These delusions carry with them extreme consequences in the real world.”

Money is power. Poverty is an immaterial prison. And the Hartz-laws, with the contemptuous ideology and systematic agitation (classism) behind them, are an immaterial concentration camp.

Welcome to fascism 2.0, the smart fascism of the 21st century.

First of all: I am aware that the comparison with the concentration camps is sensitive. In no way do I want to trivialize the horror of the physical Nazi concentration camps. Under no circumstances should this comparison be understood as a disregard for the suffering of the victims and their descendants.

I am talking about an immaterial concentration camp to make it clear that this time it is mainly ideological walls in which the inmates are held prisoner.

This ideology, however, has some functional parallels with the real concentration camps. And these practices have been incorporated into a legal framework in German legislation, namely the SGB II, colloquially called Hartz Laws.

Expropriation: Whoever ends up in the immaterial concentration camp HartzIV is systematically expropriated. He/she is forced to sell any “usable property”, including saved retirement provisions. Without Newspeech one could also simply say: They are robbed.

Disenfranchisement: Rights enshrined in the German Basic Law, such as the right to freedom of movement and free choice of occupation, no longer apply. “HartzIV is an open prison system,” says entrepreneur Götz Werner. In fact, HartzIV recipients are subject to the so-called “Accessibility Order”, i.e. they must be reachable at any time by letter post in order to be able to come to the authority the next day and immediately be available for a job offer.

Forced labour: HartzIV recipients must accept any “reasonable work” under threat of sanctions. The journalist Susan Bonath writes about this: “The unemployed, for example, were assigned to do clean-up work or collect garbage in cities, they had to maintain green spaces and monuments or to read aloud in nursing homes. All models had and have one thing in common: those affected work at extremely low wages, from which they alone cannot live. Compulsory work models for outsourced workers are not inventions of modern capitalists. Let us recall the workhouses whose history stretches from the early modern period to the industrial age. The German fascists established the Reich Labour Service. The aim of those in power behind it is clear: they wanted to make the unemployment that was increasingly produced in times of crisis invisible and – more or less brutally – to prevent those affected through employment from thinking about their situation.”

There have been cases where women have been advised by the authorities to prostitute themselves, because – thanks also to Gerhard Schröder – this is now nothing more than a legal job in the service sector.

Demoralization: Recipients are regularly summoned to appointments under threat of sanctions and interrogated like criminals, furthermore demoralized with the apportionment of blame and shame to be “difficult to mediate”. The institutions are operating a perfidious psycho-terror in order to scare their victims (called “customers” in neoliberal Newspeech) and systematically demoralize them. With the words of anti-HartzIV activist Manfred Bartl: “At no point is it really about ‘the human being’, but about either breaking him or her and/or making him or her identify with his ongoing oppression. But where this succeeds, nobody resists against this regime any more, because then everyone believes it: I am obviously to blame myself, I have experienced it often enough in the meantime…hence the problem of mass unemployment are not the unemployed, who only had to be “improved”, as the Hartz IV regime repeatedly circulates, but it’s the increasingly inhuman “labour market” on the one hand and the Social Code II, which literally keeps them out, on the other!

Exclusion, stigmatization and the creation of a new class of people: Indeed, the entire design of the HartzIV ideological concentration camp aims to create a new class of people in Germany who did not previously exist in this way. And it aims to keep the new lower class powerless and dependent. Resistance is suffocated from the outset by a perfidious, sophisticated mixture of ideology, class division through systematic propaganda in the corporate media, the greatest possible economic dependence and the permanent fear of those affected through the threat of sanctions.

Philosopher Byung-Chul Han, who studies the neoliberal psycho politics, comments: “It’s madness how scared the Hartz people live here. They are held in this bannoptikum, (a panopticon is a type of institutional building and a system of control designed by the English philosopher and social theorist Jeremy Bentham in the late 18th century. It is a design where a guard can watch all the prisoners from the middle. The term panopticon is nowadays used as a synonym for the global mass surveillance. A bannopticon in this sense is a prison in which the inmates are banned, becoming invisible for the public) so that they do not break out of their fear-cell. I know many Hartzer, they are treated like garbage. In one of the richest countries in the world, Germany, people are treated like scum. Dignity is taken away from them. Of course, these people do not protest because they are ashamed. They blame themselves instead of blaming or accusing society. No political action can be expected from this class.”

With the new class, the institutions created by the Hartz laws administer an army of workers who are supplied at the lowest level and who must be available, mobile, and flexible as possible at all times for any form of work. As such they exert enormous pressure on those who still have regular jobs. The Agenda 2010 was therefore also an effective instrument for wage dumping and the creation of a new, gigantic low-wage sector, for which Gerhard Schröder received great praise from his colleagues from France and other European countries.

The declared aim of the institutions (Newspeech Jobcenter) is to provide the unemployed with jobs that secure their livelihood, i.e. to get them out of unemployment (and thus out of unemployment statistics) as quickly as possible. However, this goal is nothing more that another of the usual neoliberal lies. In reality, very few people manage to escape from dependence. The authorities thus also administer a large part of the working poor, who work, but whose wages are below the HartzIV level. They fall out of the official statistics, but remain dependent and under the full control of the authorities with all the measures mentioned above.

The propaganda often proves to be a self-fulfilling prophecy for the new class in a familiar way: derided as lazy alcoholics, many actually end up as apathetic alcoholics in order to endure their hopeless existence.

This is indeed a contemptuous treatment of a class of people who are no longer worth anything in our culture. They are superfluous, rubbish, rejects, waste. We‘ve seen this before.

It’s therefore not surprising that HartzIV recipients have a significantly increased stress level. Physicians know that chronic stress is one of the most common causes of life-threatening cardiovascular disease and strokes. Those who die of stress and anxiety or end up in the medical-industrial complex are excluded from unemployment statistics. This is how concentration camps work today.

But in smart fascism 2.0, violence is ideologically much better packaged and gets along without its direct physical forms, because direct, physical violence always generates resistance, which the system must suppress or avoid.

The modern ruling class no longer needs to get their hands dirty. Instead, they use what Rainer Mausfeld calls “Soft Power”:

“The most important goal is to neutralize the will of the population to change society, or to divert attention to politically irrelevant goals. In order to achieve this in the most robust and consistent way possible, manipulation techniques aim at much more than just political opinions. They aim at a targeted shaping of all aspects that affect our political, social and cultural life, as well as our individual ways of life. To a certain extent, they aim to create a ‘new human being’ whose social life merges into the role of the politically apathetic consumer. In this sense they are totalitarian, so that the great democracy-theorist Sheldon Wolin rightly speaks of an ‘inverted totalitarianism’, a new form of totalitarianism that is not perceived by the population as totalitarianism.”