Where it all began

On a road on the outskirts of Des Moines — a city home to numerous insurance companies — large trees tower above the wooden row houses, providing shade on a hot July day.

Above the porch of one of the houses hangs a small sign that reads “Catholic Worker House.” In front of the back part of the building are tables and benches with people sitting on them. Music is playing, people are singing, someone is asleep on a bench.

In the kitchen of the house, Jessica Reznicek stands in front of the stove and slices five chicken breasts, freeing the meat from the bones. Next to them is a large pot of mashed potatoes, into which she generously spreads butter. “Our guests love butter,” Reznicek laughs. The kitchen looks as if many meals have been cooked there. Posters with anti-war messages and protest slogans are hung around the small room. On the windowsill in front of Reznicek is a statue of a bishop with a rosary around his neck.

Twice a week, Jessica Reznicek cooks for the homeless guests who come here. Usually they eat together in the living room, but since the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic, the food is distributed through the window.

“I like the days when I’m in charge of the kitchen. It takes my mind off all the things that are going on in my head,” Reznicek says as she begins washing a mountain of dishes.

Two years have passed since her protests were made public. A year ago, Jessica Reznicek moved back into the community, spending time there on house arrest. Here, where it all began, her long journey ends. She has one week left before needing to report to prison.

Just before the food is served, the kitchen and living room fill up. Two of Reznicek’s friends are there, residents of the house and volunteers from outside — together they begin to serve food to the guests.

Reznicek has been in and out of the house for 10 years. Most people know her story: “The one who blew up the pipeline?” asks Jimmy — one of the homeless guests — laughing as he tastes the still-warm mashed potatoes. The fact that she will soon be gone saddens many of the residents. For the majority of them, prison is a familiar place. But no one here has been incarcerated as long as Jessica Reznicek will be.

The Dingman House, named after a late bishop in Des Moines, is one of four side-by-side buildings of the Catholic Worker community. Christianity and anarchism meet here. In these self-organized “houses of hospitality,” which function independently of the church, people live and work among the poor in the spirit of the Sermon on the Mount. The Christian message of social justice and solidarity with the marginalized becomes everyday practice. There is not much overlap with the institutional Catholic Church. In the bathroom, where homeless guests can shower, there are free condoms; trans people find shelter here and women sometimes lead church services.

Preparations for prison

The Berrigan House across the street — named after two priests who became known for their actions of civil disobedience against the Vietnam War — has always been a place of resistance, where protest actions are planned and activists find shelter. This is where Reznicek prepared her actions against the pipeline.

As in the house next door, the walls are covered with posters calling for resistance against war, racism and injustice. It is a colorful, chaotic and untidy atmosphere. Reznicek and her friends Alex and Monty sit at the table in the living room. The two are among her closest supporters. They just had a video conversation with Reznicek’s lawyer to discuss the final steps before she goes to jail.

A month after Reznicek is sentenced to eight years in prison, they launched a campaign called “Water Defenders Are Never Terrorists.” Within a few weeks, they were able to collect thousands of signatures. Their goal: a petition to President Joe Biden and Congress demanding the terrorism charges be dropped.

The list of things to do before Reznicek goes to prison is long: return the electronic ankle bracelet, pick up the copy of her high school transcript she needs so she won’t have to attend classes in jail. T-shirts demanding her release are to be printed. Reznicek also wants to develop photos that Alex will later send to her in prison so she can decorate her cell with them. But they also want to see her favorite musical Rent, go dancing one more time, invite friends and celebrate. There is a lot of laughter when the three get together.

Jessica Reznicek’s supporters Monty and Alex in the Christian Berrigan House. (Cristina Yurena Zerr)

After the meeting, Jessica Reznicek packs a vacuum cleaner and cleaning supplies and heads out. With permission from her probation officer, she started cleaning private homes a year ago. She also worked at a pizzeria from time to time.

Why is Jessica Reznicek willing to spend eight years of her life in prison because of her commitment to clean water? She was studying political science in Des Moines and married when she learned about the Occupy Wall Street movement in 2011. Shortly after, she decided to go to New York for the protests. This meant the end of her marriage. From the East Coast, she began a new life of sorts, always on the move, searching for a way to make her contribution to a more just world.

Reznicek traveled twice to Palestine and Israel, where she was deported for protesting in solidarity with the Palestinian people. She visited the Zapatistas in Mexico and spent time in Central America with the Indigenous people of Guatemala. In South Korea, she protested the construction of a U.S. Navy base. “So I feel like all of these experiences culminated at this point in my life when I heard about the Dakota Access Pipeline.”

The Catholic Worker community in Des Moines was central to her politicization. She stumbled upon the organization after returning to Iowa from New York. There begins what she later calls a conversion: a return to the Christian faith and her Catholic roots. At the same time, this means a radicalization in the struggle against injustice: Jesus Christ is seen Catholic Workers as a revolutionary who stood up for the disenfranchised, for the weak and the poor. He wanted to drive the kings from their thrones and bring justice. And he died on the cross without resisting his judgement.

Three months after Jessica Reznicek made her actions public in 2017, the Berrigan home was surrounded by the FBI. “It was like 4:30 in the morning when they were pounding on the door. The house was actually shaking. I ran downstairs and could see around 50 agents through the window with big guns and vests.”

When she opened the door, the house was stormed by about 50 uniforms. She was thrown to the ground and held at gunpoint, she said.

She then spent a year in hiding, calling it her wanderings. “I wasn’t necessarily underground. I think that I was running and I was hiding, but it was not exclusively from the federal government. I was not hiding from prison. I was hiding from everything.”

When she broke down after 10 months in Colorado, she finally realized she needed help. It won’t come from people or places, Reznicek says, but from her relationship with God. After this experience, she realized she wanted to live in a place where she could encounter God, so she decided to enter a Benedictine convent as a novice. But no sooner does she arrive than Reznicek is again picked up by the FBI and charged. They send her back to Des Moines — to the Berrigan home — to await the verdict under house arrest.

For the last four days before she goes to prison, Jessica Reznicek was given permission to visit the sisters at the convent community in Duluth. After her incarceration, she would like to move there or — if that’s not possible — live as close to the convent as she can.

On August 11th, Benedictine sisters drove Jessica Reznicek to the women’s prison in Wascea, Minnesota, four hours away. There, 714 women currently live behind the walls and fences.

Three hundred miles to the north is the town of Bemidji, home of Energy Transfer, the energy company to which Reznicek will be in debt for the rest of her life. A new pipeline called Line 3 has been under construction at this location for several years. As with the Dakota Access Pipeline, the region’s Indigenous inhabitants — the Anishinaabe and Ojibwe tribes — will be most affected by the project.

“Today I feel sad to be saying my final goodbyes to loved ones,” Reznicek said. “I am strengthened, however, knowing that I’m still standing with integrity during this very important moment in history, as there truly is no other place to be standing at a time like this.”

With these words she takes leave of her friends and turns to face the prison gates.

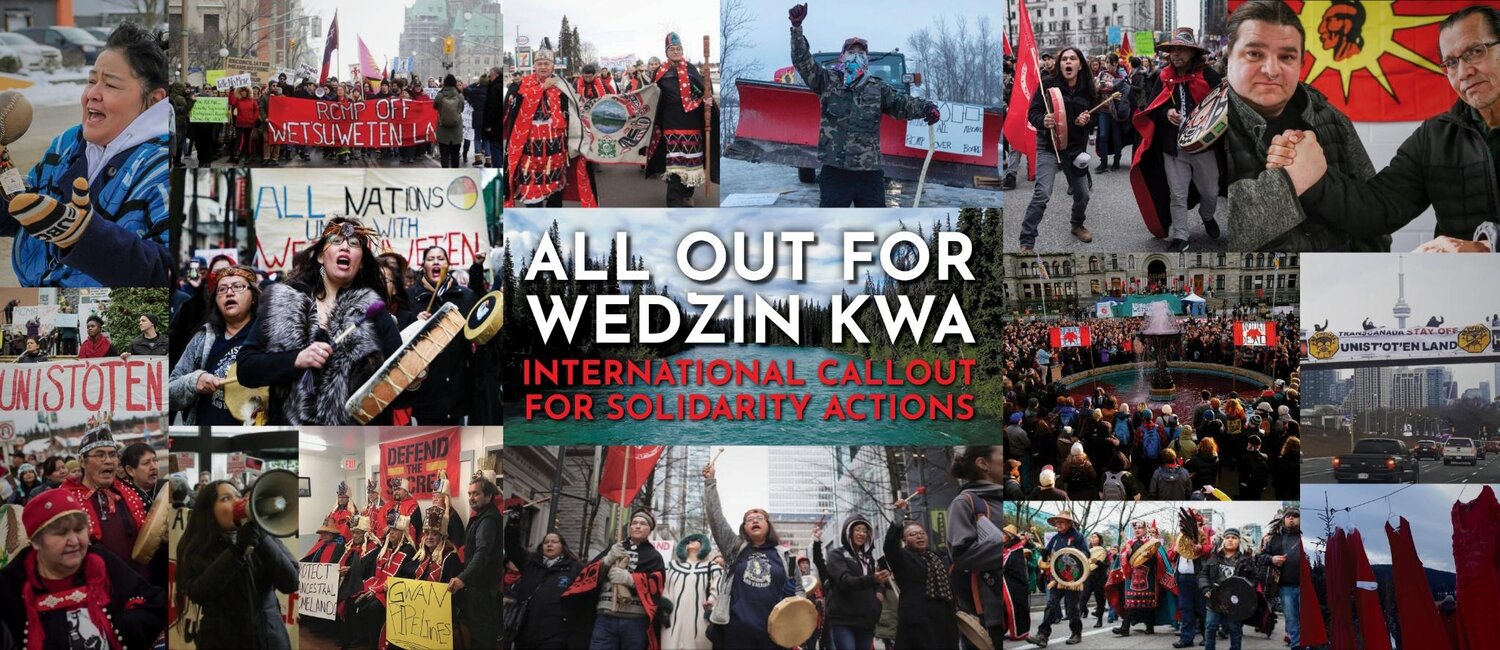

![]() Issue a solidarity statement from your organization or group and tag us.

Issue a solidarity statement from your organization or group and tag us.![]() Host a solidarity rally or action in your area.

Host a solidarity rally or action in your area.![]() Pressure the government, banks, and investors. http://yintahaccess.com/take-action-1

Pressure the government, banks, and investors. http://yintahaccess.com/take-action-1![]() Donate. http://go.rallyup.com/wetsuwetenstrong

Donate. http://go.rallyup.com/wetsuwetenstrong![]() Spread the word. #WetsuwetenStrong #AllOutForWedzinKwa #ShutDownCanada

Spread the word. #WetsuwetenStrong #AllOutForWedzinKwa #ShutDownCanada