by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 28, 2017 | Colonialism & Conquest, NEWS, Repression at Home

by Courtney Parker / Intercontinental Cry

The climate of violence endemic to the ongoing resource wars, illegal occupation, violent siege, and politically motivated land grabs of Nicaragua’s North Caribbean Autonomous Region, is continuing to escalate.

On Wednesday evening, January 25, the death of a well-known Tuahka Indigenous leader was confirmed – Camilo Frank López was shot in the forehead and killed while leaving a local bar with his cousin. López was the current Tuahka Indigenous Territorial Government Prosecutor.

López’s first cousin, Eloy Frank, who was the Deputy Foreign Minister Secretary for Indigenous Affairs of the Presidency, also suffered an injury to his arm in the attack.

The killing took place in an area known as the ‘Mining Triangle’.

Nicaragua is often lauded for its low crime rates compared to more systemic cultures of violence found in Central American nations such as Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala. However, the region where this latest killing took place, largely known as La Muskitia, has been host to intensifying violent conflict as the legal territories of Indigenous Peoples, such as the Mayagna and the Miskitu, are encroached upon by Mestizo settlers from the interior and Atlantic regions of Nicaragua.

Many claim the illegal settlers are affiliated with the ruling Sandinista political party, who have much to gain economically from seizing and exploiting the resource rich region. Estimates have held that around 85% of Nicaragua’s intact natural resource preserves are contained there; and thanks to ongoing Indigenous stewardship, much of the biodiversity is currently preserved and remains intact.

The binational Indigenous nation of Muskitia, which extends into Honduras, is also home to the second largest tropical rainforest in the western hemisphere – second only the Amazon in size and commonly referred to as “the lungs of Central America”– and many endangered species of animals.

Photo by Mario von Rotz on Unsplash

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Dec 10, 2016 | Colonialism & Conquest

Mayanga family slaughtered by illegal colonizers while planting food on traditional land

Warning: this article includes graphic images that some readers may find disturbing.

by Courtney Parker / Intercontinental Cry

In a shocking escalation of the ongoing violent conflict devastating the Indigenous binational autonomous nation of Moskitia, a Mayanga family of three was killed in a brutal attack by ‘Colonos’ at the Llano Sucio site of the Alamikamba community in the Awala Prinsu territory on November 27, 2016. The attack sent shockwaves through the already war torn territories of Moskitia.

The family’s names and ages were documented by community members; and, the Miskito community continues to seek international solidarity amidst this tragedy and related ongoing devastation. The Mayanga individuals who lost their lives in this most recent and exceptionally brutal attack, have been identified as:

Bernicia Dixon Peralta, age 30 (family and community members claim she was between 3 and 5 months pregnant);

Photo: Cejudhcan Derechos Humanos

Feliciano Benlis Flores, age 37;

Photo: Cejudhcan Derechos Humanos

And, their 11 year old son, Feliciano Benlis Dixon.

Photo: Cejudhcan Derechos Humanos

Reports from the community indicate the family was on the receiving end of threats from invading Colonos – heavily armed Mestizo settlers encroaching on Miskito territory, acting as agents of a large scale land grab. They also say these threats were fully realized last weekend while the family was attempting to plant seeds on their traditional land.

Eklan James Molina, mayor of Alamikamba, which is located in the municipality of Prinzapolka, has demanded a thorough investigation of the massacre. In a statement to one of the few independent news outlets in Nicaragua, La Prensa, he charged: “As mayor, I ask the police and the army to follow up on the case. You have to get to the bottom of why it [occurred].”

In the article published by La Prensa, unverified claims surfaced suggesting the deceased family’s land had been illegally sold to the violent, encroaching settlers by a mysterious third party. Nancy Elizabeth Henriquez, deputy of the YATAMA Indigenous political party – the only real political opposition to the Sandinista state in the region at this time – has dismissed such claims as already having been settled in a court of law; and, explicitly categorized this recent massacre as a revenge killing. In her statement to La Prensa, she relayed, “The owner sued and won the right [to the land] that is theirs; and the Colonos killed the entire family for revenge.” She cited ongoing ethnic clashes as one potential reason the Nicaraguan National Police continue to allow such atrocities to take place with impunity.

Moskitia, a lesser known conflict zone where the violent and heavily armed Meztizo settlers from the Pacific coast and interior of Nicaragua continue to invade traditional and legal Miskito land, has been experiencing escalations in terrorism and violence since June of 2015, according to an official statement issued by the Miskito Council of Elders in August of this year. In a statement published by The Ecologist in October, the elders explained:

“Since ancient times we’ve [cared for] our forests, because apart from being our only means of sustenance, we understand that any alteration to [them] attracts risks; alters our form of life; puts existence itself at risk; causes drastic changes [to] the climate; alters the ecosystem; and breaks our link with our ancestors.

[For] little more than five years, [we] have experienced the largest internal colonization [of] our history. The presence of ‘Colonos’ has drastically altered our form of life. In such a short time [the invasion] has destroyed tens of thousands of hectares of our forests, which has led to [the drying of] our rivers, [causing] the animals [to] migrate and the climate to alter, and us to emigrate. Our large forests are now deserts, occupied for the livestock, and [we] can do nothing to curb the advance of the settlers as they have the support of the Government of Nicaragua and [we] are alone.”

***

At this point, the much hyped November presidential election in Nicaragua has come and gone. President Daniel Ortega managed to further consolidate power and formally establish the foundations for a family dynasty and authoritarian dictatorship. All fanfare aside, Fidel Castro’s recent death means little in a pragmatic sense to the quasi-socialist, former Sandinista revolutionary, Ortega; his contradictory embrace of neoliberalism has carved out even more geopolitical space for a disturbing emerging brand of neoliberal authoritarianism – more in line with Putin’s newly conservative Russia, the theocratic regime of Iran, and the authoritarian capitalism embraced by China, than Fidel’s revolutionary ideals in Cuba. It is thus likely no coincidence that all three of the aforementioned nations have sought a stake in the notorious Nicaragua trans-oceanic canal. After mounting skepticism regarding whether the environmentally catastrophic, human rights disaster would actually come to fruition, recent reports have cited the monstrous development project may be poised to move forward after all. At least 11 non-violent protestors were recently injured amid the growing anti-canal movement.

Another recent report from La Prensa indicates the continued violent expansion of the agricultural frontier into the Indigenous nation of Moskitia – which includes the second largest tropical rainforest in the Western Hemisphere after the Amazon, referred to as the ‘lungs of Mesoamerica’ – may also be tied to Russia’s increasing imperialist presence in the region. A key player in the re-militarization of Nicaragua, Russia recently sold the impoverished nation an estimated 80 million dollars’ worth of military war tanks (some suggesting to suppress ongoing internal dissent) and is launching a strange new imperial drug war in the region. It is unclear what stake Russia has in fighting a drug war in Central America, but the La Presna report suggests that they may be hoping for a payoff in agricultural land appropriated through recent land grabs and ongoing deforestation.

Featured image: A young Miskitu girl stands before an armed indigenous resistance force in Muskitia, Nicaragua. From Ecologist Special Report: The Pillaging of Nicaragua’s Bosawás Biosphere Reserve, by Courtney Parker

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Sep 11, 2016 | Gender

by Meghan Murphy / Feminist Current

Planned Parenthood, as you may know, is the largest single provider of reproductive health services in the United States. The non-profit defines itself as “leading the reproductive health and rights movement,” and has supported millions and millions of women, over the past century, in accessing pregnancy tests, contraceptives, sex education, STD tests, abortions, and more. But do they know how women’s reproductive systems work?

Recent actions leave us guessing.

On September 2nd, Planned Parenthood tweeted, “Menstruators in New York started to #TweetTheReceipt celebrating the repealed tampon tax — but some are still charged.”

Many were left wondering what a “menstruator” was — previous to this, we’d all simply referred to each other as “women.” But it seems that Planned Parenthood’s social media intern is not the only one confused about the fact that literally only female bodies are capable of menstruating.

Marie Solis, a writer for Mic responded to the immediate push back from women, angered at having been reduced, essentially, to bleeders, by explaining, “Not everyone who menstruates is a woman! @PPact is using ‘menstruators’ to be inclusive.”

Inclusive of whom, you might ask? Solis responds, “‘Menstruators’ is meant to include trans men, for example, who may still menstruate.”

Conundrumy! How is it possible for a human being — trans or not — to menstruate if they do not, in fact, have ovaries and a uterus? Well, hold on to your hats, folks — the answer is: it’s not possible. Every single person who menstruates has a female body. Does this make you feel uncomfortable? Apparently it makes Planned Parenthood uncomfortable, which is odd, as they, of all people, should understand these basic facts about women’s bodies, as experts and educators on the very topic of women’s bodies.

Despite the fact that numerous women were kind enough to remind Planned Parenthood that it was ok to acknowledge that women’s bodies are real things that exist and are different from men’s bodies, the non-profit was back at it again the very next day, tweeting, “Purvi Patel has been released from prison, but people continue to be criminalized for their pregnancy outcomes.”

Who are these “people” who “continue to be criminalized for their pregnancy outcomes,” you might also ask. Has a man ever, in all of history, been criminalized for his pregnancy outcome? The answer, of course, is no. That has literally never happened. Purvi Patel was jailed because she has a female body, and that female body, once pregnant, miscarried. Apparently, punishing women based on the way their pregnancies end is ever-popular in the U.S., as well as in many other countries. This practice has put countless women’s lives in danger and contributes to our ongoing marginalization, but hey, no need to acknowledge this reality as a gendered one. Women’s rights are people’s rights, after all.

Oh wait, that’s not right.

You see, the reason patriarchy exists is because men decided they wanted control over women’s sexual and reproductive capacities. Not people’s sexual and reproductive capacities — women’s. Sexual subordination is a gendered phenomenon, no matter how you identify, and for an organization that exists to advocate on behalf of women — due to their female biology (you know, the thing that placed them, whether or not they chose it or like it, within an oppressed class of people) — to erase that is unconscionable.

A woman is an adult female human — it really is as simple as that. And understanding how that reality is at the root of our ongoing oppression under patriarchy is one thing that is not up for debate.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 18, 2016 | Alienation & Mental Health, Indigenous Autonomy

Featured image: An indigenous youth from Kwalikum First Nation sings. Photo: VIUDeepBay @flickr. Some Rights Reserved.

By Courtney Parker and John Ahni Schertow / Intercontinental Cry

The spiraling rate of suicide among Canada’s First Nations became a state of crisis in Attawapiskat this week after 11 people in the northern Ontario community attempted to take their own lives in one night.

The First Nation was so completely overwhelmed by the spike in suicide attempts that leaders declared a state of emergency. Crisis teams were soon deployed by various agencies to help the community cope with the horror. Meanwhile, as news coverage of the shocking situation spread, activists occupied the Toronto office of Indigenous and Northern Affairs to demand the federal government provide immediate and long-term support to properly address the situation in Attawapiskat.

At least 100 people from the small Cree community have attempted suicide since September. This alarming number—5 per cent of Attawapiskat’s population—is symptomatic of a larger and more pervasive problem in Canada.

While cancer and heart disease are the leading causes of death for the average Canadian, for First Nations youth and adults up to 44 years of age the leading cause of death is suicide and self-inflicted injuries.

According to Health Canada, the suicide rate for First Nations male youth (age 15-24) is 126 per 100,000 compared to 24 per 100,000 for non-indigenous male youth. For First Nations women, the suicide rate is 35 per 100,000 compared to 5 per 100,000 for non-indigenous women.

Handling this situation through a lens of crisis management simply will not do.

In order to bring an end to this long-standing crisis, there are systemic, cyclical and multi-generational issues that must first be addressed, with special attention given to ongoing disruptions in individual and cultural identity.

Historical impacts of colonization, compounded by Canada’s ongoing policies of forced assimilation, are pulling today’s First Nation youth further and further away from their core cultural identities. These identities and cultures have the power to protect and sustain all First Nation youth, and provide them with the resilience they need to overcome whatever individual factors may place them at risk for suicide.

Noting that the Pimicikamak Cree Nation in central Manitoba also responded to the epidemic by declaring their own state of emergency in March, national chief of the Assembly of First Nations, Perry Bellegarde recently proclaimed:

“We need a sustained commitment to address longstanding issues that lead to hopelessness among our peoples, particularly the youth.”

Bellegarde further lamented the lack of specially trained community health workers. He also cited Attawapiskat First Nation’s need for a mental health worker, a youth worker, and proper fiscal support to train workers in the community to respond.

Mainstream media has its own role to play.

Research has shown that merely talking about the devastating indigenous suicide epidemic can have unspeakably damaging consequences.

In 2007, a Canadian research team compiled a comprehensive report entitled, “Suicide Among Aboriginal People in Canada.” The text goes into great detail about how the media should—and should not—handle this extremely delicate subject matter.

“Mass media—in the form of television, Internet, magazines, and music—play an important role in the lives of most contemporary young people. Mass media may influence the rate and pattern of suicide in the general population (Pirkis and Blood, 2001; Stack, 2003; 2005). The media representation of suicides may contribute to suicide clusters. Suicide commands public and government attention and is often perceived as a powerful issue to use in political debates. This focus, however, can inadvertently legitimize suicide as a form of political protest and thus increase its prevalence. Research has shown that reports on youth suicide in newspapers or entertainment media have been associated with increased levels of suicidal behaviour among exposed persons (Phillips and Cartensen, 1986; Phillips, Lesyna,and Paight, 1992; Pirkis and Blood, 2001). The intensity of this effect may depend on how strongly vulnerable individuals identify with the suicides portrayed.

Phillips and colleagues (1992) offer explicit recommendations on the media handling of suicides to reduce this contagion effect. The emphasis is on limiting the degree of coverage of suicides, avoiding romanticizing the action, and presenting alternatives. There is some evidence that this may actually reduce suicides that follow in the wake of media reporting (Stack, 2003). Many Canadian newspaper editors have adopted policies to minimize the reporting of suicide to reduce their negative impact (Pell and Watters, 1982). Suicide prevention materials can also be disseminated through the media. The media can also contribute to mental health promotion more broadly by presenting positive images of Aboriginal cultures and examples of successful coping and community development.”

Even greater than the need for more socially responsible media, is the need for more proactive and community-specific solutions on the ground.

There is a growing body of evidence demonstrating the value of taking protective measures to prevent suicide by preserving and promoting the regular use of traditional indigenous languages.

In 2008, researchers Chandler and Lalonde published a report entitled, “Cultural Continuity as a Protective Factor Against Suicide in First Nations Youth.” In their review, they touched on an inherent risk in raising the conversation on the indigenous suicide epidemic to the international level – though it is particularly severe in Canada, it is indeed global – describing how it may obstruct community-based and community-specific solutions from emerging. Findings also confirmed that individual and community markers of cultural continuity – such as language retention – can form a protective barrier against the staggering incidence rates of suicide ravaging First Nations like Attawapiskat and the Pimicikamak Cree Nation.

Chandler and Lalonde conclude that:

“First Nations communities that succeed in taking steps to preserve their heritage culture, and that work to control their own destinies, are dramatically more successful in insulating their youth against the risks of suicide.”

In 1998, the same research team—Chandler and Lalonde—published a preliminary report detailing some of the most salient markers of cultural continuity among First Nations. Noted protective factors included: land claims; self-governance; autonomy in education; autonomy in police and fire services; autonomy in health services; and the presence of cultural facilities.

Interestingly, indigenous self-governance was discovered to be the strongest protective factor of all. Lower levels of suicide rates were also measured in communities exhibiting greater control over education, and in communities engaged in collective struggles for land rights—or, as they often call it Latin America: ‘La Lucha’!

In 2009, another research team that included Art Napoleon, Cree language speaker, language and culture preservationist and faith-keeper, issued a call for more research on the association between native language retention and reduced rates of indigenous youth suicide. They also called for more inter-tribal dialogues and community based, culturally tailored, strategy building. Their report detailed a host of other significant protective factors such as: honoring the connection between land and health; recognizing traditional medicine; spirituality as a protective factor; maintaining traditional foods; and, maintaining traditional activities.

Yet, perhaps the most compelling evidence to date connecting cultural continuity—and specifically, language retention—with reductions in First Nation suicide rates came in 2007, from research team, Hallett, Chandler and Lalonde. Their analyses demonstrated that rates of language retention among First Nations had the strongest predictive power over youth suicide rates, even when held amongst other influential constructs of cultural continuity. Their conclusions hold shocking implications about the dire importance of native language preservation and retention efforts and interventions.

“The data reported above indicate that, at least in the case of BC, those bands in which a majority of members reported a conversational knowledge of an Aboriginal language also experienced low to absent youth suicide rates. By contrast, those bands in which less than half of the members reported conversational knowledge suicide rates were six times greater.”

It is important to drive this point home. In the First Nation communities where native language retention was above 50 per cent (with at least half of the community retaining or acquiring conversational fluency) suicide rates were virtually null, zero. Yet in the bands where less than half of community members demonstrated conversational fluency in their native tongue, suicide rates spiked upwards of 6 times the rates of surrounding settler communities.

It is also worth noting how overall spikes in suicide prevalence found in Indigenous communities around the world indicate a strong correlation with the socio-political marginalization brought on by colonization. In other words, the suicide epidemic—which is at heart a crisis of mental health—is directly related to, if not directly caused by, the loss of culture and identity set in motion by colonialism.

Cultural continuity—and perhaps most specifically, native language preservation and retention—plays a crucial role in overcoming the ongoing native suicide epidemic—and indeed near universal barriers to indigenous mental health—once and for all First Nations, on a community by community basis.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 11, 2016 | Colonialism & Conquest, Toxification

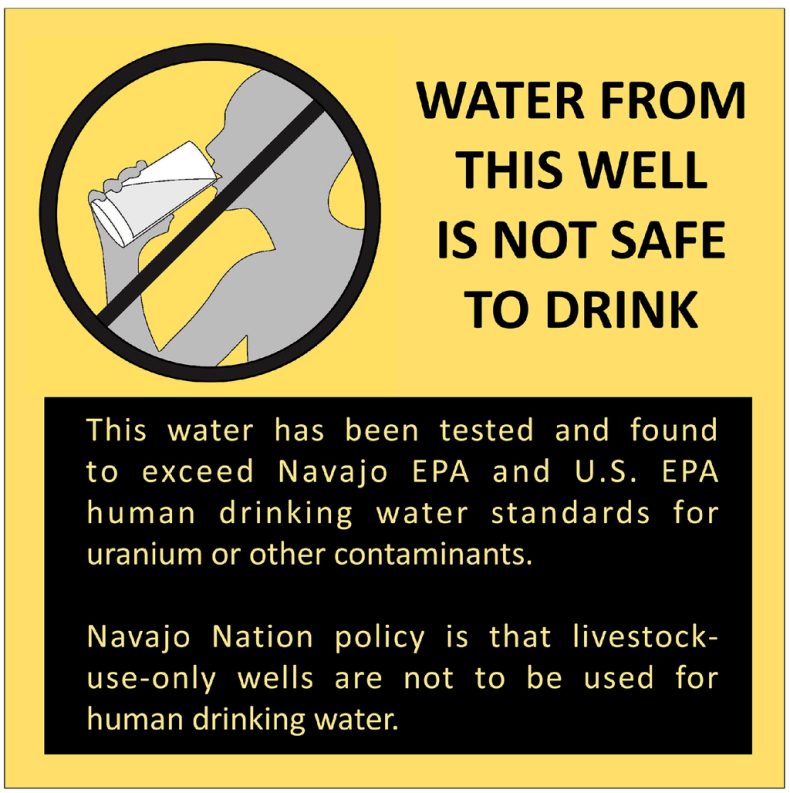

Featured image: Figure from EPA Pacific Southwest Region 9 Addressing Uranium Contamination on the Navajo Nation

By Courtney Parker / Intercontinental Cry

Recent media coverage and spiraling public outrage over the water crisis in Flint, Michigan has completely eclipsed the ongoing environmental justice struggles of the Navajo. Even worse, the media continues to frame the situation in Flint as some sort of isolated incident. It is not. Rather, it is symptomatic of a much wider and deeper problem of environmental racism in the United States.

The history of uranium mining on Navajo (Diné) land is forever intertwined with the history of the military industrial complex. In 2002, the American Journal of Public Health ran an article entitled, “The History of Uranium Mining and the Navajo People.” Head investigators for the piece, Brugge and Gobel, framed the issue as a “tradeoff between national security and the environmental health of workers and communities.” The national history of mining for uranium ore originated in the late 1940’s when the United States decided that it was time to cut away its dependence on imported uranium. Over the next 40 years, some 4 million tons of uranium ore would be extracted from the Navajo’s territory, most of it fueling the Cold War nuclear arms race.

Situated by colonialist policies on the very margins of U.S. society, the Navajo didn’t have much choice but to seek work in the mines that started to appear following the discovery of uranium deposits on their territory. Over the years, more than 1300 uranium mines were established. When the Cold War came to an end, the mines were abandoned; but the Navajo’s struggle had just begun.

Back then, few Navajo spoke enough English to be informed about the inherent dangers of uranium exposure. The book Memories Come to Us in the Rain and the Wind: Oral Histories and Photographs of Navajo Uranium Miners and Their Families explains how the Navajo had no word for “radiation” and were cut off from more general public knowledge through language and educational barriers, and geography.

The Navajo began receiving federal health care during their confinement at Bosque Redondo in 1863. The Treaty of 1868 between the Navajos and the U.S. government was made in the good faith that the government – more specifically, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) – would take some responsibility in protecting the health of the Navajo nation. Instead, as noted in “White Man’s Medicine: The Navajo and Government Doctors, 1863-1955,” those pioneering the spirit of western medicine spent more time displacing traditional Navajo healers and knowledge banks, and much less time protecting Navajo public health. This obtuse, and ultimately short-sighted, attitude of disrespect towards Navajo healers began to shift in the late 1930’s; yet significant damage had already been done.

Founding director of the environmental cancer section of the National Cancer Institute (NCI), Wilhelm C. Hueper, published a report in 1942 that tied radon gas exposure to higher incidence rates of lung cancer. He was careful to eliminate other occupational variables (like exposure to other toxins on the job) and potentially confounding, non-occupational variables (like smoking). After the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) was made aware of his findings, Hueper was prohibited from speaking in public about his research; and he was reportedly even barred from traveling west of the Mississippi – lest he leak any information to at-risk populations like the Navajo.

In 1950, the U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS) began to study the relationship between the toxins from uranium mining and lung cancer; however, they failed to properly disseminate their findings to the Navajo population. They also failed to properly acquire informed consent from the Navajos involved in the studies, which would have required informing them of previously identified and/or suspected health risks associated with working in or living near the mines. In 1955, the federal responsibility and role in Navajo healthcare was transferred from the BIA to the USPHS.

In the 1960’s, as the incidence rates of lung cancer began to climb, Navajos began to organize. A group of Navajo widows gathered together to discuss the deaths of their miner husbands; this grew into a movement steeped in science and politics that eventually brought about the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA) in 1999.

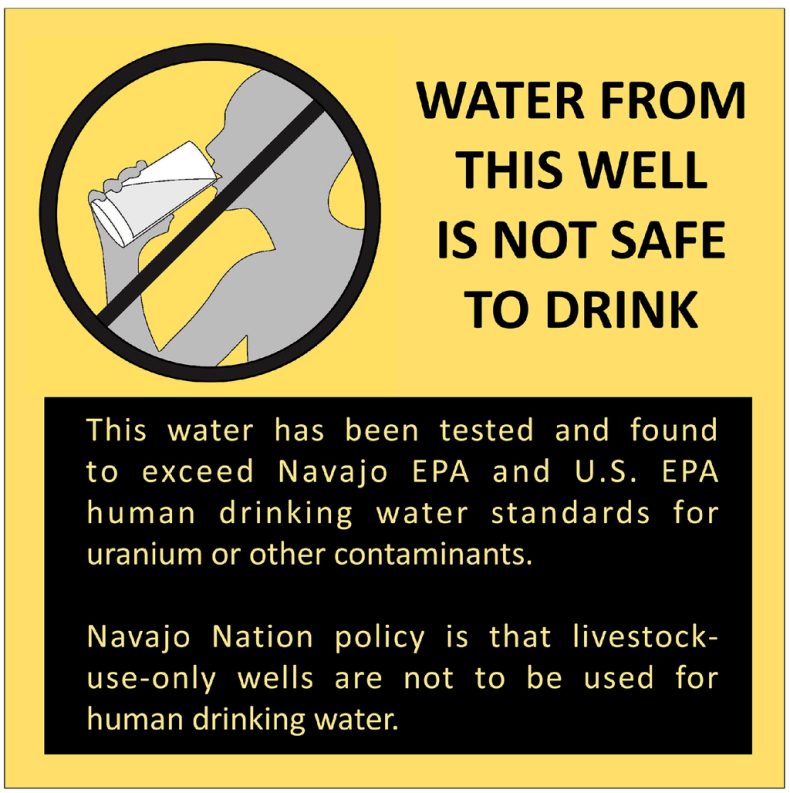

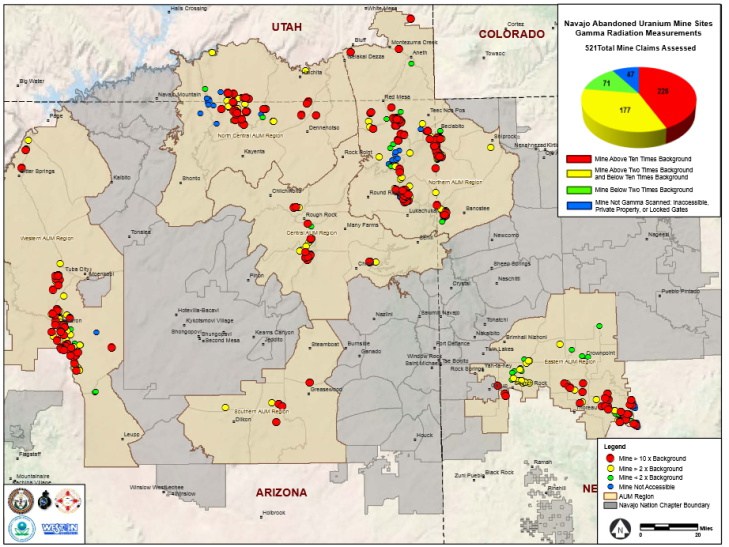

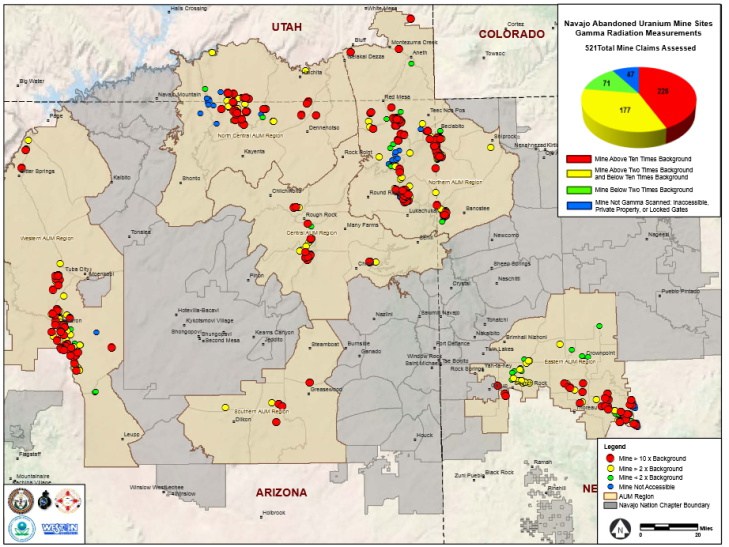

Cut to the present day. According to the US EPA, more than 500 of the existing 1300 abandoned uranium mines (AUM) on Navajo lands exhibit elevated levels of radiation.

Navajo abandoned uranium mines gamma radiation measurements and priority mines. US EPA

The Los Angeles Times gave us a sense of the risk in 1986. Thomas Payne, an environmental health officer from Indian Health Services, accompanied by a National Park Service ranger, took water samples from 48 sites in Navajo territory. The group of samples showed uranium levels in wells as high as 139 picocuries per liter. Levels In abandoned pits were far more dangerous, sometimes exceeding 4,000 picocuries. The EPA limit for safe drinking water is 20 picocuries per liter.

This unresolved plague of radiation is compounded by pollution from coal mines and a coal-fired power plant that manifests at an even more systemic level; the entire Navajo water supply is currently tainted with industry toxins.

Recent media coverage and spiraling public outrage over the water crisis in Flint, Michigan has completely eclipsed the ongoing environmental justice struggles of the Navajo. Even worse, the media continues to frame the situation in Flint as some sort of isolated incident.

Madeline Stano, attorney for the Center on Race, Poverty & the Environment, assessed the situation for the San Diego Free Press, commenting, “Unfortunately, Flint’s water scandal is a symptom of a much larger disease. It’s far from an isolated incidence, in the history of Michigan itself and in the country writ large.”

Other instances of criminally negligent environmental pollution in the United States include the 50-year legacy of PCB contamination at the Mohawk community of Akwesasne, and the Hanford Nuclear Reservation (HNR) situated in the Yakama Nation’s “front yard.”

While many environmental movements are fighting to establish proper regulation of pollutants at state, federal, and even international levels, these four cases are representative of a pervasive, environmental racism that stacks up against communities like the Navajo and prevents them from receiving equal protection under existing regulations and policies.

Despite the common thread among these cases, the wave of righteous indignation over the ongoing tragedy in Flint has yet to reach the Navajo Nation, the Mohawk community of Akwesasne, the Yakama Nation – or the many other Indigenous communities across the United States that continue to endure various toxic legacies in relative silence.

Current public outcry may be a harbinger, however, of an environmental justice movement ready to galvanize itself towards a higher calling, one that includes all peoples across the United States, and truly shares the ongoing, collective environmental victories with all communities of color.