by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 3, 2017 | Strategy & Analysis

This is the nineteenth installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

via Deep Green Resistance UK

In this run of five posts, I am assessing the environmental movement using the twelve principles of strategic nonviolence conflict as described by Peter Ackerman and Christopher Kruegler. [1] The principles are designed to address the major factors that contribute to the success or failure of nonviolent campaigns. Read more about the principles in the introductory post here. Read how the environmental movement relates to the first principle here and the second to fifth principles here.

- Attack the opponent’s strategy for consolidating control

This principle relates to Gene Sharp’s idea of undermining a regime’s sources of power (see post 6).

The mainstream environmental movement partially meets this principle. There are a small number of campaigns and groups that attempt to increase the economic costs of extractive industries, through occupation, blocking and sabotage. But with limited numbers of people willing to do this, the impact is minimum.

Fossil fuel divestment campaigns rely on businesses and institutions acting against their reason for being – concentrating wealth. So any company divesting from fossil fuels is going to be so small or marginal it won’t make any difference. Companies are legally obliged to maximise profits for their shareholders. Ninety companies are responsible for two thirds of greenhouse gas emissions since the start of industrial revolution. Coal companies have to produce coal. Oil companies have to produce oil. No matter how much we divest, if there is still demand for these things then they will continue to be extracted. The global economy cannot function without them. Ultimately, the divestment campaigns will only change the ownership of some shares from public institutions to private one.

Power and control over the population is maintained by a lack of access to land, which requires most of us to work jobs we don’t want to do, wasting our time and energy so we can afford food, shelter and heating. It’s hard work to make any money in the capitalist system, even for those who do have land, and it requires the use of industrial equipment, with the negative impacts this has on the land.

The most significant strategy for the state to maintain power and control is its willingness to use violence. Western governments pretend that they run democracies with police forces that are there to serve the public and use legitimate violence (see post 3). The mainstream environmental movement has completely failed to even identify this as a problem, let alone start thinking about how to tackle it.

- Mute the impact of the opponents’ violent weapons

Ackerman and Kruegler suggest a several options here: get out of harm’s way, confuse and fraternise with opponents, disable the weapons, prepare people for the worst effects of violence, and reduce the strategic importance of what may be lost to violence.

This principle is not really applicable in industrialised countries, because so far direct violence against environmental activists has been limited, in an attempt to continue the pretence of democracy. Activists have taken to filming the police at protests and demonstrations, to capture when the police step over the line. Violence against environmental activists is a serious problem in less-industralised countries.

- Alienate opponents from expected bases of support

This principle relates to Gene Sharp’s idea of “Political Jiu-Jitsu,” where violent states exposes what it is capable of and will to do to maintain its power and control (see post 6). For many of those following the conflict but sitting on the sidelines, this may result in them joining the fight against the state.

Governments in industrialised countries have learned that if their repression is too harsh, it radicalises people to a cause. So they now use little or no violence if possible and instead use much more subtle methods to control dissent. Therefore this principle is not applicable, but with repression on the gradual increase, that may soon change.

- Maintain nonviolent discipline

Ackerman and Kruegler argue that maintaining nonviolent discipline is not arbitrary or a moralistic choice, but instead is strategically advantageous. Although, they add that it’s not possible or desirable to morally, politically or strategically rule the use of force out. They recommend avoiding sabotage and demolition, while admitting nonviolent sabotage might be acceptable, if only to be done to prevent greater harms, with no harm to humans.

The mainstream environmental movement does conform to this principle. Nonviolence ideology is very strong across the movement and in most groups. When talking to mainstream environmentalists about the need to use force to defend ourselves and the planet, I generally get the “it won’t be successful as the state is too powerful” argument. Others say that the state uses violence so we shouldn’t, morally. Another argument I hear is concerned that using force may result in the state using heavy repression, which could hurt of kill the movement, people involved or their family and friends.

There are also a number of brave individuals outside the mainstream environmental movement that use sabotage to stop the destruction taking place.

- Assess events and options in light of levels of strategic decision making

Ackerman and Kruegler identify five levels of strategic decision making: policy, operational planning, strategy, tactics and logistics.

- Policy is similar to “grand strategy” – what and how shall we fight, how will we know if we’ve won or lost, what costs are willing to bear and inflict to meet our objective.

- Operation planning lays out how success is expected to occur – what nonviolent methods to use, and a vision of the steps necessary to reach a desired outcome.

- Strategy determines how a group will deploy its human and material assets – it adjusts constantly as things change.

- Tactics inform individual encounters or confrontations with opponents.

- Logistics refer to the whole range of tasks the support the strategy and tactic – including finances, resources, and necessary materials.

The mainstream environmental movement fails at the principle. Due to its broadness it has multiple “grand strategies” that include raising awareness, education, market-based responses such as carbon trading, living in alternative ways outside the system, and divestment campaigns. There is no coherent operational planning across the movement. Some groups and campaigns do follow the practice of developing strategies and tactics but most do not, and are instead reacting to the onslaught of this culture on the living world.

Many say that environmentalists need to frame the cause in a way that engages people. I believe the environmental movement has tried that in a number of ways. Taking fracking as an example: the poisoning of groundwater has motivated a large number of people to protest, but not enough to result in a mass movement.

So how is our movement going to convince a sufficient number of people that the global capitalist economy and industrial society need to end?

This is the nineteenth installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

Endnotes

- Peter Ackerman and Christopher Kruegler lay out twelve principle of strategic nonviolent conflict in their book Strategic Nonviolent Conflict: The Dynamics of People Power in the Twentieth Century

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Mar 22, 2017 | Strategy & Analysis

This is the eighteenth installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

via Deep Green Resistance UK

In this run of five posts, I am assessing the environmental movement using twelve principles of strategic nonviolence conflict. [1] The principles are designed to address the major factors that contribute to the success or failure of nonviolent campaigns. Read more about the principles in the introductory post here. Read how the environmental movement relates to the first principle here.

- Develop organisation strength

Although some individuals can make a difference, successful resistance is carried out by groups. Nonviolent resistance organisations need to develop certain capabilities. They must adapt to changing situations, make decisions under pressure, and communicate these decisions to mobilisation. They need to be capable of concealments, dispersion and surprise. Ackerman and Kruegler describe three strata of organisation: leadership, operational corps, and the broad civilian population.

The mainstream environmental movement has failed to develop organisation strength. It has a large number of groups, but due to the broadness of the movement and multiple aims there is a distinct lack of organised structure and coordination. Individuals and groups in the mainstream environmental movement are generally left-leaning or follow an anarchist philosophy of decentralised organising. This has resulted in a movement of small groups that avoid structure and hierarchy, all focusing on their specific issue. This can have its advantages if a small local grassroots group is tackling a local problem, but is a serious weakness if trying to build a united movement to stop climate change and the destruction of the global biosphere.

Many in the movement are too busy squabbling over which reformist solution is best or which lifestyle choices and new technologies will allow their comfortable lives to continue. Unlike those on the right, who are very focused on their goal of maximising profits at any cost.

- Secure access to critical material resources

These are needed to ensure the physical survival of resisters and so they can carry out nonviolent actions. This principle is focused on a nonviolent conflict situation where resisters need to ensure they have the basic necessities of life so they can maintain the campaign until success.

The mainstream environmental movement does have access to critical material resources, although it has not been tested in a serious nonviolent conflict. Many in the movement are middle class in paid employment with access to funds and professional skills. Large parts of the environmental movement have also been co-opted by corporations resulting in ineffective Non-Government Organisations (NGOs).

- Cultivate external assistance

This is either direct or indirect support for the campaign from outside the immediate arena of conflict. It may be public acts of support, direct material aid; or third parties may launch sanctions of their own.

I do not think this principle is directly applicable to the mainstream environmental movement due to its international scope. Environmentally minded billionaires could be looked to, to provide this external assistance. Naomi Klein in her a book This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The Climate dedicates a chapter to exploring the contributions of Richard Branson, Warren Buffett, Bill Gates etc and find they are basically looking for technology to save the day.

- Expand the repertoire of sanctions

Gene Sharp lists 198 nonviolent methods. Ackerman and Kruegler suggest five questions to ask when choosing which methods to use:

- Which methods will allow the resisters to seize and retain the initiative?

- Are the methods easily replicable?

- Can the methods be performed at different times and places without special training and preparations? And can the methods be dispersed or concentrated at will?

- Do the methods make sense from an economy of force and risk versus return perspective?

- Are the methods being used in a planned sequence that will build momentum and maximize their impact, while also maintaining flexibility?

The mainstream environmental movement partly meets this principle in that it does use a wide range of nonviolent methods, that are replicable. But the movement preference for media stunts results in it failing to seize and retain the initiative or build momentum in any significant way. The environmental movement does not carry out many acts of omission (see the Taxonomy of Action diagram). It mostly focuses on the “Indirect Action” areas of the acts of commission such as lobbying, protests and symbolic actions, education and awareness raising, and support work and building alternatives. Of course it is up against corporate media and disinterested public, but nevertheless does little to actively confront or threaten the current power arrangements.

The number of people in the environmental movement who are willing to use nonviolent methods to challenge power are low, and because there is little focus on collective strategy or coordination, they fail to employ an economy of force. Also, the movement’s “politics of the comfort zone” culture (see post 13) mean that few are even willing to get arrested, let alone anything more serious. The movement certainly doesn’t have the numbers and popular support of, say, the 2010 French pension reform strikes. This movement had 3.5 million people at its height, and sadly that campaign had limited success.

On a positive note, there have been a number of recent mass actions that have had an effect. In 2015, 1500 people from across Europe entered a lignite mine in the Rhineland, Germany and shut it down. In May 2016, 300 people shut down Ffos-y-fran coal mine, the UK’s biggest mass trespass of a mine. Also in May 2016 over 3,500 people shut down Vattenfall’s Ende Gelände lignite coal operations in Germany in a mass action of civil disobedience. Coal trains, diggers, power plants were all disrupted.

This is the eighteenth installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

Endnotes

- Peter Ackerman and Christopher Kruegler lay out twelve principle of strategic nonviolent conflict in their book Strategic Nonviolent Conflict: The Dynamics of People Power in the Twentieth Century

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Mar 13, 2017 | Strategy & Analysis

This is the seventeenth installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

via Deep Green Resistance UK

In the next four posts I will assess the environmental movement based on the twelve principles of strategic nonviolent conflict that Peter Ackerman and Christopher Kruegler lay out in their book Strategic Nonviolent Conflict: The Dynamics of People Power in the Twentieth Century. The principles are designed to address the major factors that contribute to the success or failure of nonviolent campaigns. The authors stress that the principles are exploratory rather than definitive. Read more about the principles in the introductory post to this run of posts here.

- Formulate functional objectives

Here we are looking for a clear goal and subordinate objectives. Five criteria help formulate functional objectives. They need to be concrete and specific enough to be achievable within a reasonable time frame. They need to include a diverse range of nonviolent methods. They need to maintain the main interests of the protesters rather than the adversary. They must attract the widest possible support within the relevant society. The objectives need to appeal to the values and interests of external parties to gain their support.

The mainstream environmental movement fails on this principle – formulate functional objectives. It does use a wide range of nonviolent methods, but fails to meet the other four criteria. Most critically, because it’s so large and diverse, it has no clear goal or objectives. I have run a number of workshops on this topic and none of the participants can agree on the goal and objectives of the environmental movement, and get confused between the goals and objectives of the whole movement or specific campaigns. Generally they all want a livable planet in the future and they seem to go about this by trying to convince everyone else that they need to take environmental issues seriously. This slow burn, paradigm shift strategy is not proving effective.

The movement also fails to determine its response based on what needs to happen in the material realm; versus, say, the taking-issues-seriously realm–in light of very pessimistic scientific forecasts–so fails to identify functional and appropriate objectives. Building a mass movement to transition to a sustainable society might have been possible if it had happened in the twentieth century, but we are now out of time and need drastic action to leave the fossil fuels in the ground.

The environmental movement also struggles because nature is currently viewed as property. So those that own parts of nature are legally allowed destroy them, with some minimal limitations. The more nature you own the more nature you can destroy. The environmental movement has been urging a more careful use of that property – environmental regulation. Attorney Thomas Linzey explains that successful movements take property like African American slaves or women before suffrage and convert them from the status of property, to a person or rights-bearing entity. There has never been an environmental movement that has focused on this, and anyone who has suggested it has been labeled radical or crazy. [1]

The environmental movement fails to attract wide support because it is telling people about a problem in the future that will mean they have to change their lives dramatically now. Of course there is also the whole issue of how the culture turn living systems into products to make money, but many don’t seem to notice this. This causes people’s denial reflexes to kick in so many find excuses not to think about it or act: “the science is wrong;” “the government will handle it;” “I recycle so I do my bit;” “they’ll find a technology to sort it out.” And because industrialised countries have such atomised societies with no community, then there is no moral code for anyone to answer to, just the made-up laws from the state.

There is much written about the psychological reasons why people fail to engage and act on climate change and environmental destruction, with seven books recently published on the subject.

The American Psychological Association task force identified six barriers to people acting:

- uncertainty about climate change;

- mistrust of scientists/officials;

- denial;

- undervaluing risks so deal with them later;

- lack of control – individual actions too small to make a difference;

- habit – ingrained behaviours are slow to change.

A recent report from ecoAmerica and the Center for Research on Environmental Decisions (CRED) at Columbia University’s Earth Institute — entitled “Connecting on Climate: A Guide to Effective Climate Change Communication,” identified seven psychological reasons that are stopping us from acting on climate change:

- psychological distance – too far in the future;

- finite pool of worry – people can only worry about a certain amount at once;

- emotional numbing – people get emotionally overloaded;

- confirmation bias and motivated reasoning – people seek out and retain information that matches their world view;

- defaults – people are overly biased in favor of the status quo;

- discounting – people value loss of money far in the future as less important that money now;

- ideology – political beliefs are deeply felt and highly emotional, even though it’s not clear how we come to these conclusions.

The phenomenon that psychologists call the “passive bystander effect” is relevant here. If people feel powerless they will deliberately maintain a level of ignorance so that they can claim that they know less than they do and wait for someone else to act first, to protect themselves.

Another recognised strategy to avoid dealing with climate change is to keep it out of your “norms of attention”. Basically people use selective framing so they don’t have to think about climate change most of the time. Opinion polls find that people define it as either a global issue, or far in the future. Others might say it’s only a theory or blame other countries. The fact that climate change is now seen as an environmental issue also resulted in it being excluded from their primary concerns or “norms of attention.” They can say “I’m not an environmentalist” or “The economy and jobs are more important.”

Without a functional, accurate analysis of a situation, there can be no way to formulate functional objectives to confront it. Because most peoples’ norms of attention are not focused on the actual gravity and immediacy of global warming, any organisation formulating functional objectives only accounts for a small number of actively engaged resisters, and what they can realistically accomplish.

More to follow.

Endnotes

- Thomas Linzey interviews with Derrick Jensen http://resistanceradioprn.podbean.com/e/resistance-radio-thomas-linzey-102013/ and http://prn.fm/resistance-radio-thomas-linzey-06-19-16/

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 28, 2016 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Indirect Action

Featured image: Candelaria residents erect a fence around the Suyul Lagoon to help protect it from intruders. (Waging Nonviolence/Sandra Cuffe)

By Sandra Cuffe / Waging Nonviolence

The reeds and grasses are as tall as Sebastián Pérez Méndez, if not taller. The vegetation is so thick it’s hard to see the water in the Suyul Lagoon that he and other local Maya Tzotzil residents are working hard to protect. Pérez Méndez crosses the road to point out where aquatic plants serve as a natural filter for the water as it flows out the lagoon, located in the highlands of Chiapas, in southern Mexico.

“The water is under threat,” he said. Pérez Méndez is the top authority of the Candelaria ejido, a tract of communally-held land in the municipality of San Cristóbal de las Casas. “We’re not going to allow it.”

Communities in Chiapas are organizing to protect the Suyul Lagoon and communal lands from a planned multi-lane highway between the city of San Cristóbal de las Casas and Palenque, where Mayan ruins are a popular tourist destination. Candelaria residents continue to take action locally to protect the lagoon. They also traveled from community to community along the proposed highway route, forming a united movement opposing the project.

It all started back in 2014 when government officials showed up in Candelaria looking for ejido authorities, including Pérez Méndez’ predecessor. It was the first residents had heard about plans for the highway. The indigenous inhabitants had not been consulted and were not shown detailed plans.

“They realized that [the government officials] were only seeking signatures,” Pérez Méndez said.

No one person or group is authorized to make a decision that would affect ejido lands, however, and there are strict conditions in place to ensure elected ejido leaders are accountable to members, he explained. An extraordinary assembly was held to discuss the highway project.

The Candelaria ejido was established in 1935, a year after a new agrarian law enacted during the Lázaro Cárdenas administration led to widespread land reform throughout Mexico. More than 2,000 people live in the 1,600-hectare ejido, and more than 800 of them are ejidatarios — legally recognized communal land holders whose rights have been passed down for generations. Only ejidatarios as a whole have the power to make decisions on issues like the highway project.

Candelaria residents paint over graffiti to fix up a roadside sign proclaiming their opposition to the highway project. (Waging Nonviolence/Sandra Cuffe)

“The ejido said no,” said Guadalupe Moshan, who works for the Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Human Rights Center, or FrayBa, supporting Candelaria and other communities in Chiapas. “They didn’t sign.”

Candelaria leaders sought assistance from FrayBa in 2014, after they were approached by government officials and pressured to sign a document indicating their consent to the highway project that would involve a 60-meter-wide easement through communally-held lands. Officials told community members that the highway was already approved and that they would be well compensated, but that there would consequences if they refused to sign, Moshan said.

“They told them they would suspend government programs and services,” she explained. In the days following the extraordinary ejido assembly rejecting the project, there was unusual activity in the area, according to Moshan. Helicopters flew over theejido, unknown individuals entered at night, and trees were marked, she said.

Protecting the Suyul Lagoon remains at the heart of Candelaria’s opposition to the planned highway. The lagoon provides potable water not only for Candelaria, but also for several nearby communities, said ejido council secretary Juan Octavio Gómez. Aside from the highway itself, project plans eventually shown to the community leaders include a proposed eco-tourism complex right next to the lagoon. That isn’t in the communities’ interest, Gómez explained.

“Water is life. We can’t live without it,” he said. “Without this lagoon, we don’t have another option for water.”

Fed by a natural spring, the Suyul Lagoon never runs dry. Local residents are careful to protect the water and lands in the ejido, where the majority of residents live from subsistence agriculture, sheep rearing and carpentry. They engage in community reforestation, but have plans to plant more trees, Gómez said.

The Suyul Lagoon is also sacred to local Maya Tzotzil. Ceremonies held every three years in its honor involve rituals, offerings, music and dance.

“It is said that it’s the navel of Mother Earth,” Pérez Méndez said.

Candelaria residents didn’t sit back and relax after rejecting the highway project in their extraordinary assembly. They have been organizing ever since. The Suyul Lagoon lies just outside the Candelaria ejido, but it belongs to ejidatarios by way of an agreement with the supportive land owner. Aside from the highway project and potential eco-tourism complex, the lagoon has caught the attention of companies, whose representatives have turned up in the area expressing interest in establishing a bottling plant.

It’s cold in February up in the highlands, but community members have been out all day, erecting a fence around the Suyul Lagoon to protect it from intruders. White fence posts are visible under the treeline across the sea of reeds. Like so many other local initiatives, fence materials are collectively financed by the ejido and the labor is all voluntary, communal work.

While residents continue stringing barbed wire from post to post, others take paintbrushes to one of their roadside signs. Locals have erected large signs next to roads in and around their ejido, announcing their opposition to the tourist highway.

A sign along the road leading to Candelaria informs passers-by of opposition to the planned super-highway. (Waging Nonviolence/Sandra Cuffe)

“We’re also already organized with the other communities,” Pérez Méndez said. “All the communities reject the super-highway.”

After they were approached by government officials, Candelaria ejido residents traveled from community to community along the entire planned highway route. Some communities hadn’t heard of the project at all, while others said they were pressured into signing documents indicating their consent, Pérez Méndez said. As a result of Candelaria’s visits, community organizing along the highway route led to the formation of a united front of opposition, the Movement in Defense of Life and Territory.

Candelaria also recently got together with other indigenous communities in the highlands to issue a joint statement rejecting the tourist super-highway and a host of other government and corporate projects and policies.

“Our ancestors, our grandfathers and our grandmothers have always taken care of these blessed lands, and now it’s our turn to [not only take] care of the lands, but also to defend them,” reads the February 10 communiqué.

“The neoliberal capitalist system, in its ambition to exploit natural assets, invades our lands,” the statement continues. “The government and transnational companies are violently imposing their mega-projects.”

Back along the edge of the Suyul Lagoon, Candelaria residents continue to string barbed wire from post to post. They’ve been at it for a while now, according to Pérez Méndez, but they’ve now stepped up their efforts and hope to finish the fence by the end of the month.

Pérez Méndez surveys the progress, protected from the unrelenting sun and icy wind by his hat and white sheep’s wool tunic. He becomes pensive when asked if he thinks communities will be able to defeat the highway project.

“Yes,” the ejido leader said, after giving it some thought. “We can stop it.”

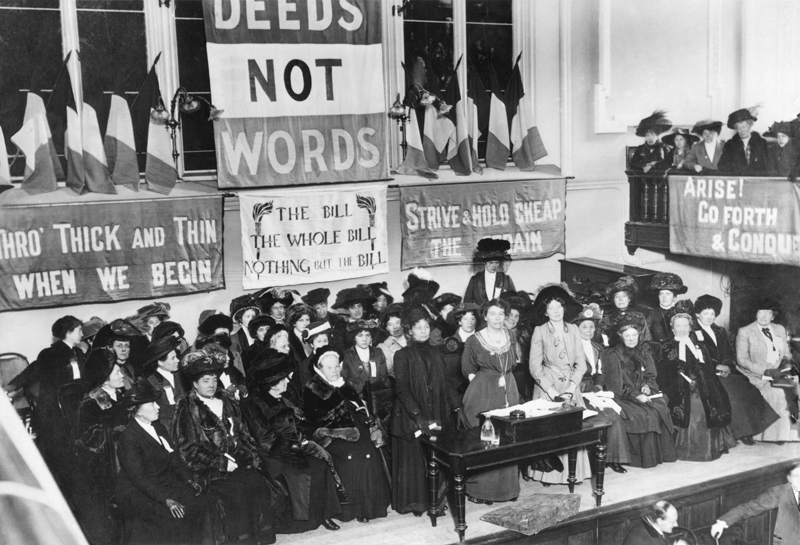

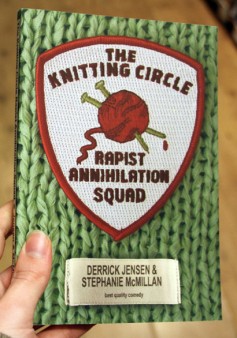

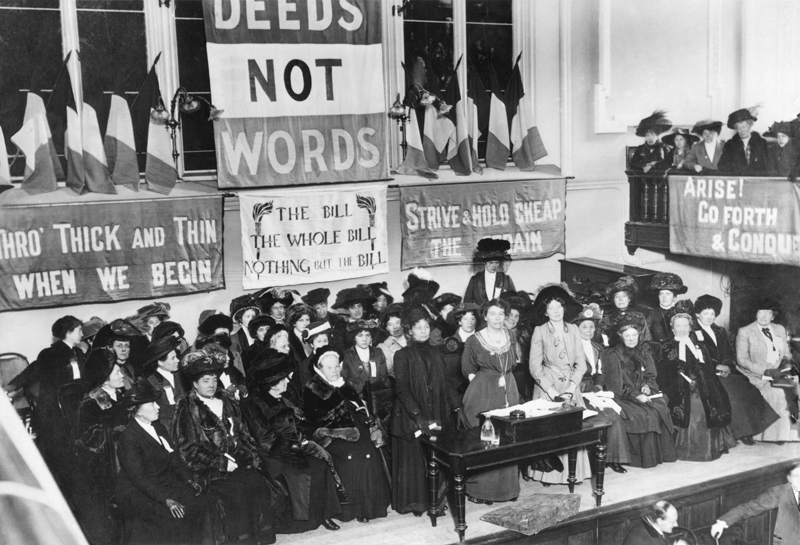

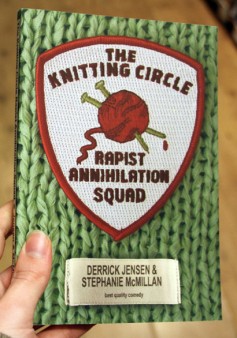

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 13, 2016 | Male Violence, Movement Building & Support, Strategy & Analysis, Women & Radical Feminism

This is the second part of a series. Read the first part at Toward Strategic Feminist Action.

By Tara Prema / Gender is War

Developing an effective response to the worldwide crisis of male violence

Strategic Feminism is a framework for collective action against patriarchal violence. The framework is based on acknowledging that the struggle for women’s liberation can – and must – adapt the lessons of asymmetric conflicts, such as guerrilla uprisings against occupying armies. We can apply the lessons of successful insurgencies to our aboveground organizing. And we must do so. It is a matter of life and death: every minute, men rape, abuse, abduct, and murder girls and women. Time is short – we must prepare for worse still to come.

Strategic Feminism draws on the excellent analysis of asymmetric conflict in Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. In Part One, we discussed the crisis of male violence against women and sketched a solution based on organizing for action in our communities. Here in Part Two, we look at more ways to begin and sustain our work for radical social change.

We call this model Strategic Feminism because it’s outcome-oriented and focused on creating a movement that addresses the material conditions affecting women’s lives.

Sustaining a movement: Feminism in collapse

How can we create a movement in a time of collapse? How do we come together as a force for change when individuals burn out, groups fall apart, and coalitions fracture? When feminists are fighting each other on questions of gender, motherhood, sexuality, and privilege?

And how to do we take these steps now, when every day brings more signs of cultural, economic, and environmental collapse? How do we adapt our strategies to a world order that is reeling from one crisis to the next? This is our challenge.

As radical women, we must pledge to protect each other and the places we love, just as women have done since the time they burned us as witches.

Keeping the spirit

Keeping the spirit

At the core of this movement, there is an intangible force with a measurable impact. It’s an attitude, a mindset, a determination that compels us to push back against oppression. It’s the warrior mindset, the stand-and-fight stance of someone defending her home and the ones she loves.

Many burn with righteous anger. This is important – anger lets us know when people are hurting us and the ones we love. It’s part of the process of healing from trauma. Anger can rouse us from depression and move us past denial and bargaining. It is a step toward acceptance and taking action.

Rewriting the trauma script includes asserting our truth and lived experiences, and naming abuses instead of glossing over them. It includes discovering (and rediscovering) that we can rely on each other instead of on men. It’s mustering the courage to confront male violence. But it’s not going to be easy.

Acknowledge and #NameTheProblem

We can’t fight a problem we can’t identify, especially when it is deliberately obscured. It’s not surprising that naming the problem has become a political act. And the problem is male violence against women. We shouldn’t have to say “she was raped” when we know that “men raped her.”

Reclaim what was taken from us

- Learning (and re-learning and reminding each other) that our bodies and spirits belong to us, we deserve to be safe, and we have the capacity to defend ourselves

- Fighting isolation and connecting with other women who have a similar fighting spirit

- Creating a culture of resistance to male violence

Taking action

Strategies are the paths to the goal. Tactics are the means to implement strategies. Part of a strategy for sustaining a movement is networks of peer support, mutual aid, and solidarity. We start by coming together with our peers, women who share the same goals and principles.

Goal: Develop a thriving network capable of effective action

Strategy: Find women allies and start a group

Tactics:

Start with a small circle: each one invite one.

Start with a small circle: each one invite one.- When you get an invitation, go!

- Use a petition or sign-on letter to gather potential recruits.

- Screen and interview volunteers.

- Discuss and write up a basis of unity

- Hold meetings, discussions, films, work parties, and benefit shows.

- Keep a signup sheet and a list of participants.

- Retain volunteers through appreciation and peer support.

- Raise money for projects and community campaigns.

Strategy: Start with an existing group

- Entryism – add members until your crew has a majority

- Headhunting – join in order to recruit members to your group

- Affinity group – organize an action team within the group

- Symbiosis – utilize the group’s resources and membership for your project

Strategy: Build a coalition

- Circulate a sign-on letter

- Organize against a common political enemy

- Host an event: A symposium, press conference, rally, or direct action

- Pledge to support and not publicly denounce each other

- Collaborate together on an ongoing project

Strategy: Keep each other safe and supported

- Have designated safe houses and emergency plans

- Set up a legal defence fund and legal team before they’re needed

- Create a mutual aid network so women activists can support each other

- Make and distribute an activist safety/security plan to stop online hackers and physical attackers

- Prioritize peer support and peer counseling, whether it’s formal or informal.

- Keep a “not wanted” list to weed out known disruptors

- Host group self-defense and security awareness trainings

Choosing our battles

How do we decide on a particular project, campaign, action or strategy? We can ask:

- Is it effective? What will it achieve?

- What are our goals (immediate and long-term )? How does this action lead there?

- Who is working with us?

- Do we have community support? From which communities?

- What decision-makers are we targeting?

- What are our strategies and tactics? (Legal, confrontational, revolutionary?)

- Do we have the resources? (People power, funds, vehicle?)

- How can we get the resources? (Recruiting, crowdfunding, direct appeals?)

- What are the possible negative outcomes? How can we mitigate the negatives?

Some actions and projects aren’t intended to lead to concrete results – they are symbolic in nature but still useful for boosting morale, getting media attention, and recruiting volunteers.

Male allies

Male allies can – and should – make substantial contributions to the movement. Consider asking women what we need to sustain our work, and then providing that without judgment or trying to exercise veto power. Men who take on ally roles should turn to other men for peer support and take time to debrief with them regularly.

Remember to regroup

Every campaign, project, and group will stall eventually. We invariably reach the point when it seems our efforts are going nowhere and our adversaries are dragging us down. This is when we must re-group and re-commit ourselves or fail. Every goal worth fighting for is going to face a serious backlash from those in power.

In spite of all our planning, our groups and coalitions still fall apart due to lack of unity, loss of commitment, burnout, and the divisive pressures of racism, classism, misogyny, and disruption from outsiders. Overall, things are not going to get better on their own. In the endgame of capitalism, the situation for women as a class worldwide is deteriorating at a fearsome rate. It’s up to us to prepare for the worst.

In the short term, this anti-feminist backlash is intensifying. Planning now is crucial. Some readers may not see the immediate need for this laundry list of tactics and strategies. But the day is coming when the need for community networks of trust will be urgent, because so much of what we rely on now has collapsed.

These notes come from unceded indigenous territory on the frontier of resistance to the western patriarchal invasion.

Keeping the spirit

Keeping the spirit Start with a small circle: each one invite one.

Start with a small circle: each one invite one.