by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Sep 29, 2018 | Colonialism & Conquest

by Jo Woodman and Alicia Kroemer / Intercontinental Cry

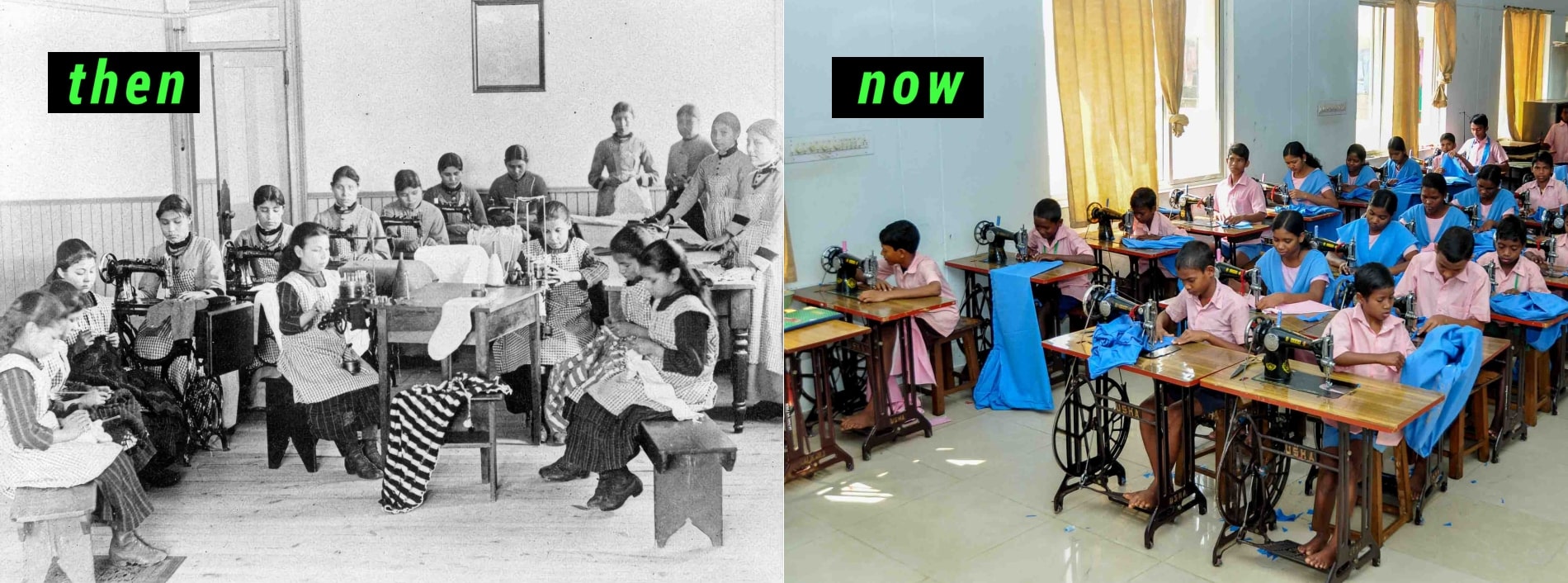

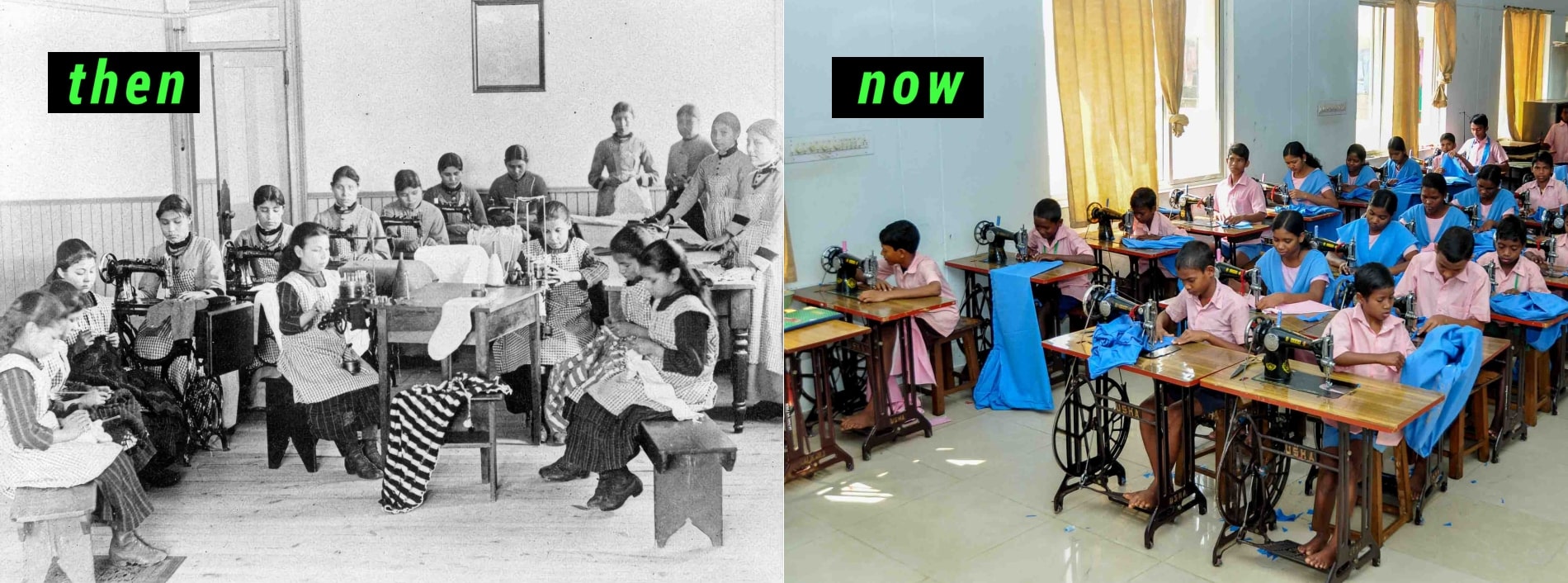

On September 30, communities across Canada will be commemorating ‘Orange Shirt Day’, an annual event that is helping Canadians remember the thousands of Indigenous children who died in Residential Schools, and to reflect on the intergenerational trauma that was caused by the Residential school system. Similar school systems were also run in the US, New Zealand and Australia with terrible consequences for Indigenous children and communities.

Stswecem’c Xgat’tem First Nation elder Phyllis Jack Webstad founded Orange Shirt Day in 2013, after she shared her childhood experience at the St. Joseph’s Mission residential school in William’s lake, British Columbia.

Residential school staff stripped her of her favourite orange shirt the day she was taken from her family. As Residential school survivor Vivian Timmins said today, “The orange day shirt is a commonality for all Native Residential School Survivors because we had our personal items taken away which was a tactic to erase our personal identity. Maybe it was a piece of clothing, but it represented our memory that connected us to families. Today is a time to honour the children and youth that didn’t make it home. It’s a time to remember Canada’s dark history, to educate and ensure such history is never repeated.”

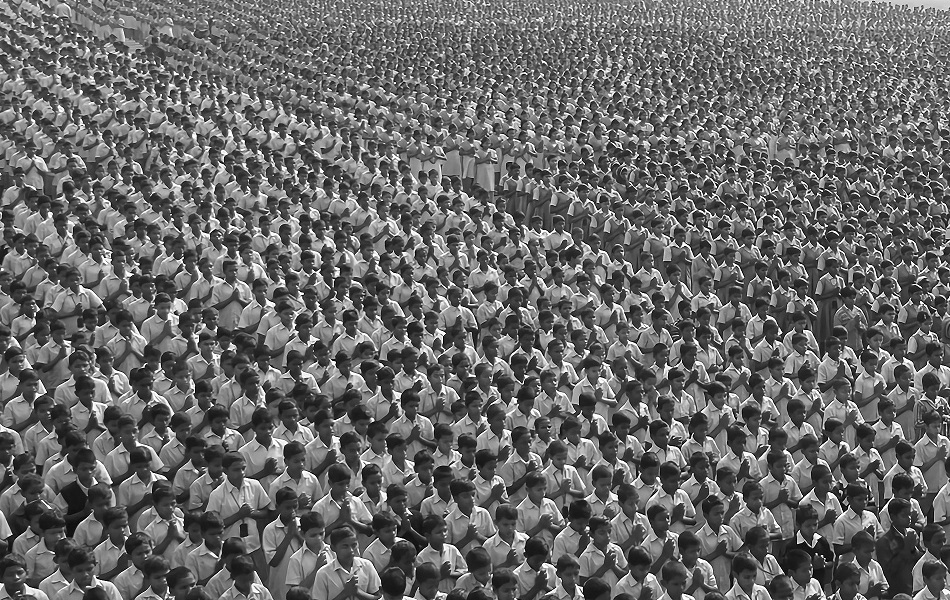

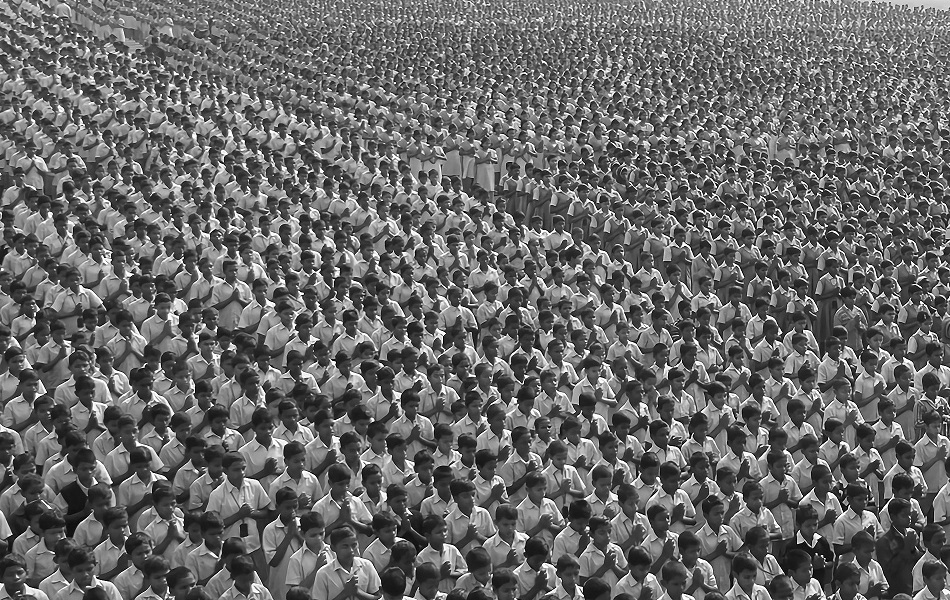

Alarmingly, that history is being repeated in many parts of the world. According to Survival International, there are nearly one million tribal and Indigenous children across Asia, Africa, and South America who are currently attending institutions that bear a striking resemblance to Canada’s residential schools.

Indigenous artist RG Miller’s haunting autobiographical painting recalls the horrific abuse he experienced at residential school. Photo Courtesy RG Miller

A horrifying legacy lives on

The horrifying legacy of residential schools is being repeated, on a massive scale, because the attitudes and intentions underlying Canada’s residential school system live on.

Tribal and Indigenous children around the world are being coerced from their families and sent to schools that strip them of their identity and often impose upon them alien names, religions, and languages.

Extractive industries and fundamentalist religious organizations are frequently pulling the strings behind these institutions.

One residential mega-school in India—which boasts it is “home” to 27,000 Indigenous children—states publicly that it aims to turn “primitive” tribal children from “liabilities into assets, tax consumers into tax payers.”

Its partners include the very mining companies that are trying to wrest control of the lands these children truly call home.

Parents have described the school as a “chicken farm” where children feel like “prisoners.”

An expert on Adivasi education told us, “Their whole minds have been brainwashed by a kind of education that says, ‘Mining is good’, ‘Consumerism is good’, ‘Your culture is bad.’ Tribal residential schools are institutions which are erasing the autobiography of each child to replace it with what fits the ‘mainstream’. Isn’t it a crime in the name of schooling?”

Without urgent change, many distinct peoples could be wiped out in just a few generations, because the the youth in these schools are taught to see their families and traditions as ‘primitive’, ‘backward’ and inferior to ‘mainstream’ society so that they turn their backs on their languages, religions and lands.

Survivors of Canada’s residential schools are beginning to speak out against these culture-destroying institutions.

“What’s happening right now at these residential schools in India and beyond is very similar to what happened with the residential schools in Canada”, says Roberta Hill

Roberta Hill is a survivor of the Mohawk Institute in Brantford, Canada, where she was abused by the pastor and school staff in the 1950s and 60s. She sees the strong parallels between her experience and that of Indigenous children in these modern culture destroying schools: “What’s happening right now at these residential schools in India and beyond is very similar to what happened with the residential schools in Canada – this separation of Indigenous children from their family, language, and culture is a very destructive force. My experience at residential school was traumatizing. I was taken from my family at the age of six and put in the school where I experienced a lot of abuse and isolation. If this is happening again now, then there needs to be international attention. It needs to stop or else they are going to go through the same thing that we went through. It will cause irreparable damage – not only to the Indigenous children attending, but to the future generations of that community.”

RG Miller, a prominent Indigenous artist from Canada states: “My horrific experience at Native residential school destroyed my connection with community, family, and my culture. The abuses I suffered there completely broke any sense of trust or intimacy with anyone or anything including God, spouses, and children for the rest of my life.”

Over the past two decades, thousands of residential school survivors have shared their stories of abuse; but there are thousands of other children who will never be able to tell their own stories because they passed away while they were in a residential school. Other children, like Chanie Wenjack, died while trying to escape. The young Ojibwe boy ran away from his residential school in Ontario, trying desperately to reach home, 600 km away. He died of hunger and exposure at the age of 12 in 1966.

Half a century later—and 12,000km away—Norieen Yaakob, her brother Haikal and five of their friends, fled their residential school in Malaysia. The children, who belong to the Temiar—one of the Orang Asli tribes of central Malaysia—ran away to avoid a beating from their teacher. 47 days later, Norieen and one other little girl were found, starving but alive. The other five children died, including Haikal and seven-year-old Juvina.

Juvina’s father, David, told us, “The police said, “Why are you bothering us with this problem?” We felt hopeless. It was only on the sixth day that the authorities began their search and rescue mission for the children. But they told us parents to stay behind. They said if we went in it would just be to secretly give food to the missing children that we were supposedly hiding. They accused us of faking the whole incident to gain attention and force the government to help us more. That was what they thought of us… [Finally] they found a child’s skull and we could not identify immediately whose child it was. We had to wait for the post-mortem. I could not recognize my own child.” The families are currently taking the authorities to court in a case that the world should be watching.

Norieen Yaakob of the Temiar tribe of Malaysia barely survived running away from her residential school. She was found 47 days after fleeing her school; five other children died.

The terrible truth is that Indigenous children are dying in these schools. In tribal residential schools in Maharashtra state in India, over one thousand deaths have been recorded since 2000, including many suicides. With echoes of the traumas experienced in Canada, many parents never learn that their children are ill until it is too late, and they often never know the cause of death.

There are also a frightening number of cases of physical and sexual abuse, very few of which reach the justice system. Government schools across Asia and Africa are often staffed by teachers who have no connection to, or respect for, the communities they serve. Teacher absences are common, and abuse goes unseen and unreported. The potential for devastating damage is extremely high.

Survival International will soon launch a campaign to expose and oppose these culture destroying schools and to demand greater Indigenous control of education, before it is too late for these children, their communities, and their futures.

There is certainly a need for it. These schools endanger lives and strip away identities, but they also deny children the right to choose a tribal future.

The ability of Indigenous Peoples to live well and sustainably on their lands depends on their intricate knowledge, which takes generations to develop and a lifetime to master. To survive and thrive in the Kalahari Desert or to herd reindeer across the Arctic tundra cannot be learnt in residential schools, or on occasional school vacations.

What’s more, in this current age of severe environmental degradation, climate change and mass extinctions, Indigenous Peoples play a crucial role in preserving the world’s ecosystems. They are the best guardians of their lands and they should be respected and listened to if we have any hope of survival for future generations.

Rather than erasing their knowledge, skills, languages, and wisdom through culture-destroying residential schools, we must allow them to be the authors of their own destinies as stewards and protectors of their own lands.

Tribal children in Indonesia learning on their land, in their language. Photo: Sokola Rimba

Dr. Jo Woodman is running Survival International’s upcoming Indigenous Education campaign. She has spent two decades researching and campaigning on Indigenous rights issues, focused on the impacts of forced ‘development’, conservation and schooling on tribal communities.

Alicia Kroemer holds a PhD in political science from the university of Vienna on collective memory and residential schools in Canada, with publications, films, and lectures on the topic. She serves on the board of Indigenous rights NGO Incomindios in Zurich, where she is a human rights educator and UN representative. She also works as a research consultant for Minority Rights Group and Survival International in London, UK. She is interested in allyship, advocating and promoting human rights, with a special focus on Indigenous rights globally.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jul 26, 2018 | Lobbying

Featured image: Molleturo communities visit the site of the Rio Blanco mine to make sure the activities are suspended as required by a court order.

by Manuela Picq / Intercontinental Cry

Last June, an Ecuadorean court ordered the suspension of all mining activities by a Chinese corporation in the highlands of Rio Blanco, in the Molleturo area of the Cajas Nature Reserve. It was a local court in Cuenca that gave the historic sentence: a court shut down an active mine for the first time in the history of Ecuador. Judge Paúl Serrano determined that the Chinese private corporation Junefield/Ecuagoldmining South America had failed to consult with the communities as required by Ecuador’s Constitution and by the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

Judge Serrano deemed the mining activity illegal and ordered the corporation to immediately suspend all its activities. Within two weeks, local communities accompanied police forces and local government officials in monitoring that the court order was respected.

Police and Molleturo communities discuss procedures to monitor the suspension of mining activities. Photo: Manuela Picq

The company appealed, and pressure was on the rise for the following hearing. The Chinese corporation privately offered $18 million to community leaders. Ecuador’s President, the Minister of Mines and the Minister of the Environment visited the province to pressure the local courts and indigenous communities to accept the mining activity. They defended “sustainable” mining as a form of development.

Affected communities consolidated their resistance, monitoring the access to the mine to impede mine workers to enter their territories, building support from neighboring communities, and informing the international community of the legal stakes.

Photo: Manuela Picq

On July 23, 2018, the court met again to either ratify or revert the decision to suspend mining activities in Rio Blanco. The court listened to all sides along with some expert testimonies; but there were discrepancies among the judges who postponed their verdict for another week.

Molleturo’s lasting vigilance for their waters

The Rio Blanco mine is located in the Molleturo-Mollepongo region, above ten thousand feet in the Andes. The mining license encompasses approximately six thousand hectares of paramos, lakes, and primary forests that nourish eight important rivers. This area replenishes the water system of the Cajas National Park, one of the largest and most complex water systems of Ecuador, which covers over a million hectares and holds immense water reserves.

The area is recognized as a natural biosphere reserve by UNESCO. These mountains have long been the home of Kañari-Kichwa indigenous communities. There are 12 archeological sites in the Molleturo area alone: the most famous one is the Paredones archeological site, located right by the mine.

Photo: Manuela Picq

The area is also a vital supply of water. These paramos provide water to 72 communities in Molleturo, freshwater to towns in the southern coast of Ecuador and to the city of Cuenca, the country’s third largest city which praises the quality of its drinking water.

The Rio Blanco mine is expected to be active for seven years, removing about 800 tons of rock per day and using cyanide to extract gold and silver. This entails an estimate of one thousand liters of water per hour that would be contaminated with deadly toxic waste, including arsenic, before being thrown back into rivers and soil.

Local indigenous communities were never consulted prior to the development of the project that would benefit from a recent Ecuadorean law incentivizing foreign investment. Nor did they give their consent to the licensing of their territories to the Junefield corporation. They reject the mine because it would contaminate their waters.

Photo: Manuela Picq

Women are at the forefront of the resistance that began almost two decades ago, when the mining license was first issued. Molleturo communities have been arguing in defense of water more or less actively over the last decade and a half but stepped it up when the mine started its activity in May 2018. Protests exploded, and a group burned out the miner’s living quarters.

Nobody was hurt in the explosion, but the police intervened, heavily armed, to militarize the area. The next day, protesters called in the president of Ecuador’s Confederation of Kichwa People Peoples for help, Yaku Perez Guartambel, but workers from the mine kidnapped him for eight hours, threatening to kill him. Tensions boiled to new heights.

Prior consultation as a fundamental indigenous human right

The Judge ordered the suspension on the mine–invoking constitutional and international indigenous rights to prior consultation.

Rosa, a delegate from the Andean Network of Indigenous Organizations (CAOI), discusses the territorial dimension of self-determination to community members gathered in the páramos of the Cajas mountain range. Photo: Manuela Picq

Since 1989, Art. 6 of the International Labor Organization Convention 169 safeguards indigenous rights to prior consultation on projects taking place on indigenous territories. Art. 18 of UNDRIP establishes indigenous rights to participate in decision making relating to their territories, and Art. 19 establishes that states must consult “in good faith” to obtain indigenous “prior, free, and informed consent: about legislative of administrative measures impacting their communities. In 2016, Art. 25 of the American Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples reiterated these principles in the context of the Organization of American States.

Prior consultation is not a simple law; it constitutes a fundamental human right of indigenous peoples because their existence is intimately tied to their territories. Their culture, lifeways, and community structures are woven into territorial autonomy.

An Amicus Curiae from a Chinese environmental lawyer

About half a dozen amicus curiaes were presented to Cuenca’s court supporting the communities right to prior consultation, from a range of organizations including the Environmental Defense Law Center, Ecuador’s Ecumenic Commission of Human Rights (CEDHU) and the Ecuadorian group Critical Geographies. Amicus were presented by scholars from Ecuadorean and American universities, including Universidad Internacional del Ecuador, Universidad de Cuenca, Universidad San Francisco de Quito, American University, and Coastal Carolina University.

Environmental lawyer Jingjing Zhang, from Beijing, submitted an amicus in which she provided an overview of relevant Chinese laws and regulations. She testified to the court on July 23, 2018, explaining that China ratified the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2007, thus supporting prior consultation and consent for any project on their territories. She reminded the words of the Chinese delegate at the 13th Session of the UN Permanent forum on Indigenous Issues (2014): “ the international community is duty bound to fully meet the legitimate requests of indigenous peoples, to promote and protect their basic human rights and freedoms, to safeguard the natural environment and resources on which their survival depends” and China “firmly supports the promotion and protection of the basic human rights and fundamental freedoms of all indigenous peoples around the world. ”

Jingjing testifies to the court in Cuenca, July 23 2018, with an interpreter. Photo: Manuela Picq

She explained to the court that China has regulations establishing that enterprises may not violate international treaties ratified by the Chinese government and that they are bound by the laws and environmental regulations of the host country. She stated that The Communist Party of China (CPC), State Council, and various government agencies have issued policy guidelines that encourage Chinese companies to focus on ecological environmental protection in their foreign investments. In her view, the Chinese government has deep concerns on the law-abiding and environmental performance of Chinese companies operating overseas.

Her amicus concluded that China’s Environmental Protection Law, Environmental Impact Assessment Law, and the Government Information Disclosure Regulation have strict provisions on the public participation rights of citizens. These regulations are based on the same principles and contain similar provisions to the Ecuadorian norms on the rights of indigenous peoples to prior consultation.

One step forward or two sets back?

The court sentence to suspend the mine marked a milestone of hope to Indigenous peoples and nature defenders. Yet the old tactics of legal warfare are still in use. Within a week of the court sentence, over 20 nature defenders were criminalized, eight of them charged with the crime of sabotage.

The private corporation Junefield/Ecuagoldmining South America did not have to do engage in public debate, Ecuador’s government is taking the lead. It was the Ministry of the Interior who accused indigenous peoples to defend the interests of the Chinese corporation. “The state proves that it is the best lawyer of mining companies,” says Yaku Perez Guartambel.

Will the criminalization of nature defenders continue? For now, judges are holding off a final verdict, and as the clock ticks political and economic pressures thicken. Molleturo leader Fausto Castro says that communities want their right to life back, and that they seek a peaceful solution to this mining conflict. It is indeed an achievement that serious confrontations were avoided, but this may not last forever. Yesterday, when the Judge staved off sentence as hundreds of nature defenders awaited outside the courtroom, many expressed their fears: “if the court reverts its sentence to benefit the State, it is a declaration of war.”

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Mar 14, 2018 | Indigenous Autonomy

Featured image: Indigenous women gathered at the Independence Plaza to hand down their demands to the president. Credit: Yasunidos

by Pablo Orellana Matute / Intercontinental Cry

PUYO, ECUADOR – As in many spots around the globe, Women’s Day in Ecuador was marked by manifestations vindicating their role within society. For Indigenous women in the country, this was no exception. Unlike the short-lived momentum of the date, however, their strategy extended well beyond commemorative schedules. Their objective was clear: Their voices had to reach the country’s Presidential Palace.

For over nine months, political dialogues between Indigenous organizations and President Lenin Moreno’s government have left scattered results. Yet the gap from words to deeds remains firmly in place. The government’s reluctance to fully implement compromises was exposed when, early this month, the Minister of Hydrocarbons announced that a further oil auction is underway despite an explicit commitment to the contrary.

Or worse, when Ecuadorian Minister of Mines Rebeca Illescas, in a clear act of defiance, bypassed Indigenous legitimate leaders and introduced a co-opted low-rank Indigenous representative to give support to the country’s participation at the Prospectors and Developers Association in Canada (PDAC), a major mining investment event earlier this month, a move that was promptly repudiated by Shuar Indigenous Leaders.

Negotiations with the Moreno administration continue with no promising prospects despite all these low blows. Yet what the government did not see coming was that an unexpected group of major players is starting to take its toll on the discussions with a voice of their own: Indigenous women.

March in Puyo on Women’s Day. Credit: Andrés Viera V.

From the heart of Ecuador’s Amazon

In Puyo, the capital of Pastaza –Ecuador’s biggest Amazonian province–, Indigenous women from all over the Amazon region started off their own efforts to further pressure the government. Leaders of seven nationalities including the Andoa, Achuar, Kichwa, Shuar, Shiwiar, Sapara and Waorani were present at the event.

Led by female Indigenous leaders from the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of the Ecuadorian Amazon (CONFENAIE), the main Indigenous organizations in the Oriente region, the movement strategically crafted a bold agenda that extended for four days.

On March 8, seizing the visibility of the date, the events set off with a march that set the tone for their demands in defense of their territories. Around 350 Indigenous women from across the Ecuadorian Amazon marched down the streets of Puyo to speak up against the extractivist industries.

The message was clear: They had had more than enough of the contamination and exploitation of their territories.

March in Puyo reassembling Indigenous female leaders from seven nationalities of the Amazon region. Credit: Yasunidos

The march was followed by a three-day gathering in Union Base, a landmark concentration spot at the outskirts of Puyo from where major Indigenous protests have been launched in the past. IC Magazine attended the event, which included the establishment of a women-only Assembly of Amazonian Women. For the inaugural session on Friday, March 9, around 400 assembly members had registered, including female leaders and representatives from across the country who had responded to the call of the organizers.

Upon inaugurating what was going to be a three-day session before embarking on a trip to the country’s capital, Elvia Dagua, CONFENAIE’s Leader of Women, reminded the audience that “Women’s Day is not March 8 alone, but every single day of the year.” This, she said, is because there is no life without women, before inviting the few male attendants to also join their cause.

“Together, men and women, we are going to defend our Mother Earth,” she said, as she opened the floor for participants to intervene.

According to Patricia Gualinga, a well-known Indigenous leader of the Sarayaku community and also a participant of the congress, the goal of this series of events is to make women’s voices and proposals heard. In her view, their aim is to awaken public opinion in the face of their latent fearsof what lies ahead. The government, Gualinga told IC Magazine, is calling for another oil auction in the South-East of the country’s Amazon, which is the reason why women are raising their voices in unity.

Leading panel for the Assembly of Amazonian Women on March 9 in Union Base. Credit: Ursula Cliff

Towards a different relationship with Nature

Throughout the opening session, assembly participants were asked to share their own experiences with extractivist activities, as well as to advance concrete proposals for overcoming them. Be it caused by mining or oil extraction activities, stories portraying violence and discrimination cut across themes that marked the interventions.

A participant at the Assembly of Amazonian Women. Credit: Ursula Cliff

Another recurring topic was the importance of such events in bringing together efforts to speak with one voice. Alexandra Proaño Malaver, president of the Andoa nationality located in the province’s far eastern border with Peru, expressed to IC Magazine her desire for local communities to further be included in such events.

“For us women, to talk about the defense of our territories and of life itself, we should do it from the communities” she said. The struggle should not only come from those women who live in the city, she explained, for it is “us, Indigenous women, that day by day are sowing and harvesting […] and thus sustaining life in our communities.”

Far from excluding men, all female leaders talked about a certain gender balance. Proaño, for instance, reckoned that “equity between man and woman is very important for [them]” while pointing out the experiences within her own nationality. A point that was further corroborated by Gualinga when she said, “We do not exclude men; we actually strengthen the relationship between (women and men).”

“This is simply a kind of space where we women regain our own voice,” she added.

Patricia Gualinga’s intervention in the Assembly of Amazonian Women unveiling the Kawsak Sacha project of the Sarayaku community. Credit: Andrés Viera V.

During her long-awaited intervention within the assembly, Patricia Gualinga unveiled her community’s proposal for overcoming the constant failures of what in her view are top-down approaches for the protection of the Amazon. Elaborated by members of the Sarayaku community, Kawsak Sacha, Living Forest in Kichwa is a new scheme when it comes to natural conservation, she said, that leaves the responsibility of the protection of the Amazon in the hands of Indigenous people.

In her view, this is a proposal that intends “to change the conception of everything that we have been taught at school,” for it is based on her own ancestral traditions and Indigenous ways of relating to Nature. The project’s goal, she said, is “to transform the whole scheme on which the current and obsolete economic system is based.”

Without providing further details as to the specifics of the project besides a major launch event in Quito in the coming months, Gualinga’s intervention served rather to spur the mood of the audience.

“This is a proposal for and by us; nobody has done the thinking for us,” she proclaimed in a boost to the pride of Indigenous women and their holistic relation to Nature that they want to share with the world.

Alicia Cahuiya, another experienced Indigenous leader from the Waorani nationality located in Yasuní National Park, shared with IC Magazine some key insights as to the overall message they are trying to send. “The government needs to understand that these are ancestral territories,” she said. “We don’t want more oil and mining companies; our territories need to be respected.”

Confronted with the government’s continued neglect, their message seems to preserve the living voices of the Amazon. “This is our home; here we have lagoons, waterfalls and animals and they all have spirits,” Cahuiya said, the government needs to grasp that “they all need to be included and heard, because our lives are interconnected with theirs.”

Waorani leader, Alicia Cahuiya, intervening in front of the Assembly of Amazonian Women to expose the dangers of the oil industry within the Yasuní National Park. Credit: Andrés Viera V.

Standing up in unity, directly defying power

The working sessions in Puyo resulted in a document that incorporated all their demands. The next and final destination was Quito, Ecuador’s capital, to hand down their ‘mandate’ to the President himself.

Indeed, on Monday, March 12, the march reached the capital for a press conference scheduled at the Independence Plaza, right in front of the Presidential Palace.

The collectively crafted document called Mandate of Amazonian Women included 22 specific requests headed by the most urgent demand: rejecting what they consider “illegal contracts or agreements between local authorities and any oil, mining, hydroelectric or logging company,” for “we are more than 50% of the Indigenous population, we are the carriers of life and take care of our families and Mother Earth.”

The document also included, among others, their rejection to the upcoming oil auction of 16 blocks located in Ecuador’s South-East Amazon region, their request to overturn recent oil concessions in blocks 79, 83, 74, 75 and 28, as well as their solidarity and demands for the liberation of Indigenous leaders Bosco Wisum and Freddy Taish, arbitrarily imprisoned for their upfront rejection of mining activities in Shuar territories in Morona Santiago, the country’s southernmost Amazon province.

Despite mild police repression in front of the Presidential Palace, the leaders of the Indigenous women conveyed their willingness to stay until the President hears them. As of the time of this publication, Lenin Moreno had not given any response. Whether he will attend those demands or not, the message has been clear. The striking echo of their demands will be hard to ignore, for voices of the Amazon have now joined their cause.

Indigenous women gathered at the Independence Plaza to hand down their demands to the president. Credit: Yasunidos

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Aug 28, 2017 | Toxification

Peak oil extraction has passed and extraction will decline from this point onward. No industrial renewables are adequate substitutes. Richard C. Duncan sums it up in his “Olduvai Theory” of industrial civilization. Duncan predicted a gradual per capita energy decline between 1979 and 1999 (the “slope”) followed by a “slide” of energy production that “begins in 2000 with the escalating warfare in the Middle East” and that “marks the all-time peak of world oil production.” After that is the “cliff,” which “begins in 2012 when an epidemic of permanent blackouts spreads worldwide, i.e., first there are waves of brownouts and temporary blackouts, then finally the electric power networks themselves expire.”34 According to Duncan, 2030 marks the end of industrial civilization and a return to “global equilibrium”—namely, the Stone Age.

Natural gas is also near peak production. Other fossil fuels, such as tar sands and coal, are harder to access and offer a poor energy return. The ecological effects of extracting and processing those fuels (let alone the effects of burning them) would be disastrous even compared to petroleum’s abysmal record.

Will peak oil avert global warming? Probably not. It’s true that cheap oil has no adequate industrial substitute. However, the large use of coal predates petroleum. Even postcollapse, it’s possible that large amounts of coal, tar sands, and other dirty fossil fuels could be used.

Although peak oil is a crisis, its effects are mostly beneficial: reduced burning of fossil fuels, reduced production of garbage, and decreased consumption of disposable goods, reduced capacity for superpowers to project their power globally, a shift toward organic food growing methods, a necessity for stronger communities, and so on. The worst effects of peak oil will be secondary—caused not by peak oil, but by the response of those in power.

Suffering a shortage of fossil fuels? Start turning food into fuel or cutting down forests to digest them into synthetic petroleum. Economic collapse causing people to default on their mortgages? Fuel too expensive to run some machines? The capitalists will find a way to kill two birds with one stone and institute a system of debtors prisons that will double as forced labor camps. A large number of prisons in the US and around the world already make extensive use of barely paid prison laborers, after all. Mass slavery, gulags, and the like are common in preindustrial civilizations. You get the idea.

Featured image: Mogolokwena Platinum Mine, South Africa

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | May 12, 2017 | Education, Indigenous Autonomy

Featured image: Indigenous women carry the banner of the VIII Pan Amazonian Social Forum (FOSPA) during the opening march from downtown Tarapoto to Universidad San Martin on April 28. Photo: Manuela Picq

by Manuela Picq / Intercontinental Cry

Ever since European colonial powers started disputing borders on its rivers in the seventeenth century, the vast Amazon rainforest—known simply as Amazonia—has been under siege.

Amazon Peoples always resisted the colonial invasion, even after the borders were ultimately settled with the Amazon rainforest getting divided into the territories of nine states. They’ve had no choice. After all, the insatiable lust for ‘wealth at any cost’ did not lessen with time; the siege continued through the nineteenth century, in part with the rubber boom that gave way to the automobile boom.

The attack rages on even now, with the intensive push to extract everything the Amazon holds including oil, minerals, water, and land for agriculture and soy production.

Nations states are leading the land-grab, fostering environmental conflicts that kill nature defenders (most of them indigenous), displace communities, and destroy rivers for megaprojects. The organization Pastoral da Terra estimates that half a million people are directly affected by territorial conflicts in the Brazilian Amazon. About 90% of Brazilian land conflicts happen in Amazonia; 70% of murders in land conflicts take Amazon lives.

That is why people responded to “the call from the forest,” or “el llamado del bosque” in Spanish. This was the motto of the VIII Pan-Amazonian Social Forum, or Foro Social Pan Amazónico (FOSPA), that just gathered 1500 people in the town of Tarapoto, Peru.

The VIII Pan Amazonian Social Forum in Tarapoto, Peru

Photo: Manuela Picq

FOSPA is a regional chapter of the well-established World Social Forum. It is based on the same model that brings together social movements, associations and individuals to find alternatives to global capitalism. From April 28 to May 1, indigenous peoples, activists, and scholars from various parts of Amazonia got together in the campus of Universidad Nacional San Martin.

FOSPA is an important space, not only because the region is at the forefront of the climate crisis but also because it represents 40% of South America and spreads across nine countries—Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname, and French Guyana. The 370 indigenous nations in the region are an increasingly smaller part of a booming Amazon population that surpasses 33 million.

This VIII forum was well organized in an Amazon campus with comfortable work space and the shade of mango trees. In the absence of Wi-Fi, participants gathered around fruit juices and Amazon specialties baked in banana leaves at the food fair. The organizing committee, led by Romulo Torres, was most proud of creating the new model of pre-forum. For the first time, there were 11 pre-forums organized in 6 of the 9 Amazon countries to prepare the agendas.

The forum started with a celebratory march through Tarapoto. During three days, participants discussed the challenges of extractive development and land grab across the region. There was in total nine working groups organized around issues such as territoriality, megaprojects, climate change, food sovereignty, cities, education and communication.

During the opening march in defense of Amazonia, Elvira and Domingo, from Ecuador’s Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of the Amazon (Confeniae) walk along Carlos Perez Guartambel, from the Andean Network of Indigenous Organizations (CAOI) and Ecuador’s Confederation of Kichwa Peoples (Ecuarunari). Photo: Manuela Picq

“Development is the problem”

Speakers strongly criticized models of development based on extractive industries. “Development is the problem, not the solution,” said Carlos Pérez Guartambel, from the Andean Network of Indigenous Organizations (CAOI) and the Confederation of Kichwa Peoples of Ecuador (ECUARUNARI).

Speakers blamed the political left for being equally invested as the right in extractive development, destroying life in the name of development. Toribia Lero Quishpe, from the CAOI and the Council of Ayllus Markas of the Quillasuyu (CONAMAQ) argued that this investment in capitalist gains corrupted the government of Evo Morales, who licensed over 500 rivers to multinational companies.

Gregorio Mirabal, from the Indigenous Network of the Amazon River Valley (COICA) and Venezuela’s Organization of Indigenous Peoples of the Amazon (ORPIA) denounced a massive land grab by the state in the Orinoco region. He said the government is licensing land to mining companies from China and Spain to promote “ecological mining.” Indigenous populations, in turn, have not had a single land title recognized in 18 years and are denied rights to prior consultation.

Ongoing French colonization in Amazonia

A working group discusses the decolonization of power and self-government in Peru. Photo: Manuela Picq

One of the working groups focused on the decolonization of power; French Guyana being the last standing colonial territory in South America.

Rafael Pindard headed a delegation from the Movement for Decolonization and Social Emancipation (MDES) to generate awareness about Amazon territories that remain under the colonial control of France.

Amazon forests constitute over 90% of French Guyana. Delegates described laws that forbid Indigenous Peoples to fish and hunt on their ancestral territories. They explained the mechanisms of forced assimilation—the French state refuses to recognize the existence of six Indigenous Peoples, claiming that in France there is only one people, the French.

The Women’s Tribunal

The forceful participation of women was one of the forum’s most inspiring aspects. Amazon women held a strong presence in the march, plenary sessions and held a special working group on women.

The highlight was the Tribunal for Justice in Defense of the Rights of Pan-Amazonian and Andean Women. Four judges convened at the end of each day to listen to specific cases of women defenders. They heard individual as well as collective cases. Peruvian delegates presented the case of Maxima Acuña, a water defender from the Andean highlands of Cajamarca who faces death threats. Brazilian representatives from Altamira presented the case of the Movement Xingu Vivo para Sempre, which organizes resistance against the Belo Monte Dam.

The Women’s Tribunal also heard cases from across the continent. Liliam Lopez, from the Confederation of Indigenous Peoples of Honduras (COPINH), presented the emblematic case of Berta Cáceres, assassinated in 2016 for leading the resistance in defense of rivers. Delegates from Chile presented the case of Lorenza Cayuhan, a Mapuche political prisoner jailed in Arauca for defending territory and forced to give birth handcuffed.

Initiatives

Many working groups called for a paradigm shift to move away from economic approaches that treat nature as a resource. Participants defended indigenous notions of living well, or vivir bien in Spanish.

There were many initiatives presented throughout the gathering. The working group on food sovereignty proposed to recover native produce and exchange seeds, for instance, through seed banks.

The final proposals of all working groups hang in the main tent allowing participants to add suggestions before the elaboration of the final document. Photo: Manuela Picq

Delegates from the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of the Ecuadorian Amazon (CONFENIAE) and the organization Terra Mater presented a collaborative project to protect 60 million acres of the mighty Amazon River’s headwaters – the Napo, Pastaza, and Marañon River watersheds in Ecuador and Peru. The Sacred Headwaters project seeks to ban all forms of extractive industries in the watershed and secure legal titles to indigenous territories.

Wrays Pérez, President of the Autonomous Territorial Government of the Wampís Nation (GTAN Wampís) explained practices of indigenous autonomy. The Wampís, who have governed their territories for seven thousand years, have successfully preserved over a million hectares of forests and rivers in Santiago and Morona, Peru. The Wampís Nation designed its own legal statute based on Peruvian and international law, including those protecting the collective rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Amazon communication

Radio Nave covered FOSPA, organizing live interviews and debates with participants. Photo: Manuela Picq

Many venues emphasized the importance of Amazon communication. All workshops and plenary sessions were transmitted live through FOSPATV and remain available on FOSPA’s webpage.

Community radios and medias covered the forum and interviewed participants, such as Radio Marañón, Radio La Nave, and Colombia’s Radio Waira Stereo 104 (Indigenous Zonal Organization of the Putumayo OZIP).

Documentary films played in the evenings, followed by discussions. The Brazilian documentary film “Belo Monte: After the Flood” played in Spanish for the first time, followed by a debate with people affected by hydro-dams in the Brazilian and Bolivian Amazons. Other films presented include “Las Damas de Azul”, “La Lagrima de Aceite” y “Labaka.”

The Tarapoto Declaration

A plenary assembly announces the final Declaration of Tarapoto, May 1 2017. Photo: Manuela Picq

The forum closed with the Carta de Tarapoto, a declaration in defense of life containing 24 proposals. The declaration collected the key demands of all working groups. It demands that states respect international indigenous rights and recognize integral territories. It invites communities to fight pervasive corruption attached to megaprojects and suggests communal monitoring to stop land-grabbing.

The declaration stresses the shared concerns and alliances of Amazonian and Andean peoples, explicitly recognizing how the two regions are interrelated and interdependent. It denounces state alliances with mining, oil, and hydroprojects. It defines extractive megaprojects as global capitalism and a racist civilizing project.

It echoes FOSPA’s intergenerational dimension, celebrating elders as a source of historical knowledge to guide the preservation of Amazon lifeways. Youth groups, who had their own working group, demanded that states recognize the rights of nature.

Women concerns are the focus of four points. In addition to making the Women’s Tribunal a permanent feature of FOSPA, the declaration calls for the end of all forms of violence against women and the recognition of women’s invisible labor. It asks for governments to detach from religious norms to follow international women rights.

In closing, the declaration expresses solidarity with peoples who live in situation of conflict, whose territories are invaded, and who are criminalized for defending the rights of nature.

It is in that spirit that the organizing committee decided to hold the next FOSPA in Colombia. Defenders of life are killed weekly despite the peace process, revealing a political process tightly embedded in the licensing of territories to extractive industries like gold mining.

The Colombian Amazon is calling. May it be a powerful wakeup call across and beyond the Amazons.