by DGR Colorado Plateau | Jun 22, 2015 | Building Alternatives, Gender, Strategy & Analysis

In 1993 Michael Carter was arrested and indicted for underground environmental activism. Since then he’s worked aboveground, fighting timber sales and oil and gas leasing, protecting endangered species, and more. Today, he’s a member of Deep Green Resistance Colorado Plateau, and author of the memoir Kingfishers’ Song: Memories Against Civilization.

Time is Short spoke with him about his actions, underground resistance, and the prospects and problems facing the environmental movement. The first part of this interview is available here, and the second part here.

Time is Short: You mentioned some problems of radical groups—lack of respect for women and lack of a strategy. Could you expand on that?

Michael Carter: Sure. To begin with, I think both of those issues arise from a lifetime of privilege in the dominant culture. Men in particular seem prone to nihilism; I certainly was. Since we were taught—however unwittingly—that men are entitled to more of everything than women, our tendency is to bring this to all our endeavors.

I will give some credit to the movie “Night Moves” for illustrating that. The men cajole the woman into taking outlandish risks and they get off on the destruction, and that’s all they really do. When an innocent bystander is killed by their action, the woman has an emotional breakdown. She’s angry with the men because they told her no one would get hurt, and she breaches security by talking to other people about it. Their cell unravels and they don’t even explore their next options together. Instead of providing or even offering support, one of the men stalks and ultimately kills the woman to protect himself from getting caught, then vanishes back into mainstream consumer culture. So he’s not only a murderer but ultimately a cowardly hypocrite, as well.

Honestly, it appears to be more of an anti-underground propaganda piece than anything. Or maybe it’s just a vapid film, but it does have one somewhat valid point—that we white Americans, particularly men, are an overprivileged self-centered lot who won’t hesitate to hurt anyone who threatens us.

Artwork by Stephanie McMillan

That’s a fictional example, but any female activist can tell you the same thing. And of course misogyny isn’t limited to underground or militant groups; I saw all sorts of male self-indulgence and superiority in aboveground circles, moderate and radical both. It took hindsight for me to recognize it, even in myself. That’s a central problem of radical environmentalism, one reason why it’s been so ineffective. Why should any woman invest her time and energy in an immature movement that holds her in such low regard? I’ve heard this complaint about Occupy groups, anarchists, aboveground direct action groups, you name it.

Groups can overcome that by putting women in positions of leadership and creating secure, uncompromised spaces for them to do their work. I like to reflect on the multi-cultural resistance to the Burmese military dictatorship, which is also a good example of a combined above- and underground effort, of militant and non-violent tactics. The indigenous people of Burma traditionally held women in positions of respect within their cultures, so they had an advantage in building that into their resistance movements, but there’s no reason we couldn’t imitate that anywhere. Moreover, if there are going to be sustainable and just cultures in the future, women are going to be playing critical roles in forming and running them, so men should be doing everything possible to advocate for their absolute human rights.

As for strategy, it’s a waste of risk-taking for someone to cut down billboards or burn the paint off bulldozers. It’s important not to equate willingness with strategy, or radicalism and militancy with intelligence. For example, I just noticed an oil exploration subcontractor has opened an office in my town. Bad news, right? I had a fleeting wish to smash their windows, maybe burn the place down. That’ll teach ‘em, they’ll take us seriously then. But it wouldn’t do anything, only net the company an insurance settlement they’d rebuild with and reinforce the image of militant activists as mindless, dangerous thugs.

If I were underground, I’d at least take the time to choose a much more costly and hard-to-replace target. I’d do everything I could to coordinate an attack that would make it harder for the company to recover and continue doing business. And I’d only do these things after I had a better understanding of the industry and its overall effects, and a wider-focused examination of how that industry falls into the mechanism of civilization itself.

By widening the scope further, you see that ending oil and gas development might better be approached from an aboveground stance—by community rights initiatives, for example, that have outlawed fracking from New York to Texas to California. That seems to stand a much better chance of being effective, and can be part of a still wider strategy to end fossil fuel extraction altogether, which would also require militant tactics. You have to make room for everything, any tactic that has a chance of working, and begin your evaluation there.

To use the Oak Flat copper mine example, now the mine is that much closer to happening, and the people working against it have to reappraise what they have available. That particular issue involves indigenous sacred sites, so how might that be respectfully addressed, and employed in fighting the mine aboveground? Might there be enough people to stop it with civil disobedience? Is there any legal recourse? If there isn’t, how might an underground cell appraise it? Are there any transportation bottlenecks to target, any uniquely expensive equipment? How does timing fit in? How about market conditions—hit them when copper prices are down, maybe? Target the parent company or its other subsidiaries? What are the company’s financial resources?

An underground needs a strategy for long-term success and a decision-making mechanism that evaluates other actions. Then they can make more tightly focused decisions about tactics, abilities, resources, timing, and coordinated effort. The French Resistance to the Nazis couldn’t invade Berlin, but they sure could dynamite train tracks. You wouldn’t want to sabotage the first bulldozer you came across in the woods; you’d want to know who it belonged to, if it mattered, and that you weren’t going to get caught. Maybe it belongs to a habitat restoration group, who can say? It doesn’t do any good to put a small logging contractor out of business, and it doesn’t hurt a big corporation to destroy machinery that is inexpensive, so those questions need to be answered beforehand. I think successful underground strikes must be mostly about planning; they should never, never be about impulse.

TS: There are a lot of folks out there who support the use of underground action and sabotage in defense of Earth, but for any number of reasons—family commitments, physical limitations, and so on—can’t undertake that kind of action themselves. What do you think they can do to support those willing and able to engage in militant action?

MC: Aboveground people need to advocate underground action, so those who are able to be underground have some sort of political platform. Not to promote the IRA or its tactics (like bombing nightclubs), but its political wing of Sinn Fein is a good example. I’ve heard a lot of objections to the idea of advocating but not participating in underground actions, that there’s some kind of “do as I say, not as I do” hypocrisy in it, but that reflects a misunderstanding of resistance movements, or the requirements of militancy in general. Any on-the-ground combatant needs backup; it’s just the way it is. And remember that being aboveground doesn’t guarantee you any safety. In fact, if the movement becomes effective, it’s the aboveground people most vulnerable to harm, because they’re going to be well known. In that sense, it’s safer to be underground. Think of the all the outspoken people branded as intellectuals and rounded up by the Nazis.

The next most important support is financial and material, so they can have some security if they’re arrested. When environmentalists were fighting logging in Clayoquot Sound on Vancouver Island in the 1990s, Paul Watson (of the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society) offered to pay the legal defense of anyone caught tree spiking. Legal defense funds and on-call pro-bono lawyers come immediately to mind, but I’m sure that could be expanded upon. Knowing that someone is going to help if something horrible happens, combatants can take more initiative, can be more able to engineer effective actions.

We hope there won’t be any prisoners, but if there are, they must be supported too. They can’t just be forgotten after a month. As I mentioned before, even getting letters in jail is a huge morale booster. If prisoners have families, it’s going to make a big difference for them to know that their loved ones aren’t alone and that they will have some sort of aboveground material support. This is part of what we mean when we talk about a culture of resistance.

TS: You’ve participated in a wide range of actions, spanning the spectrum from traditional legal appeals to sabotage. With this unique perspective, what do you see as being the most promising strategy for the environmental movement?

MC: We need more of everything, more of whatever we can assemble. There’s no denying that a lot of perfectly legal mainstream tactics can work well. We can’t litigate our way to sustainability any more than we can sabotage our way to sustainability; but for the people who are able to sue the enemy, that’s what they should be doing. Those who don’t have access to the courts (which is most everyone) need to find other roles. An effective movement will be a well-organized movement, willing to confront power, knowing that everything is at stake.

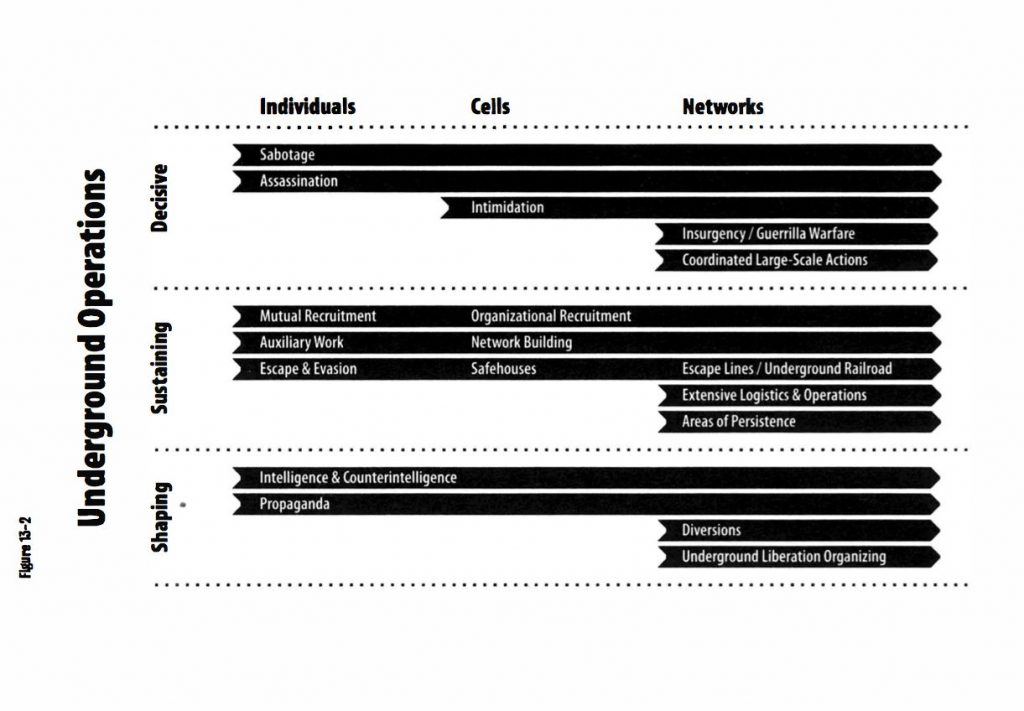

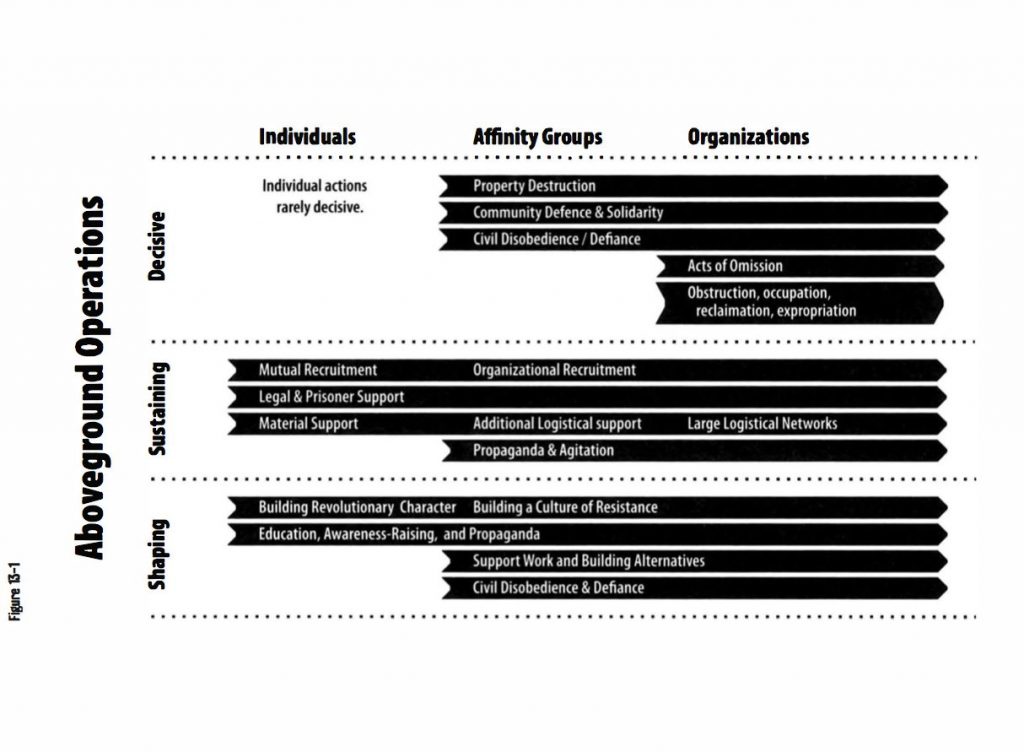

Decisive Ecological Warfare is the only global strategy that I know of. It lays out clear goals and ways of arranging above- and underground groups based on historical examples of effective movements. If would-be activists are feeling unsure, this might be a way for them to get started, but I’m sure other plans can emerge with time and experience. DEW is just a starting point.

Remember the hardest times are in the beginning, when you’re making inevitable mistakes and going through abrupt learning curves. When I first joined Deep Green Resistance, I was very uneasy about it because I still felt burned out from the ‘90s struggles. What I’ve discovered is that real strength and endurance is founded in humility and respect. I’ve learned a lot from others in the group, some of whom are half my age and younger, and that’s a humbling experience. I never really understood what a struggle it is for women, either, in radical movements or the culture at large; my time in DGR has brought that into focus.

Look at the trans controversy; here are males asking to subordinate women’s experiences and safe spaces so they can feel comfortable. It’s hard for civilized men to imagine relationships that aren’t based on the dominant-submissive model of civilization, and I think that’s what the issue is really about—not phobia, not exclusionary politics, but rather role-playing that’s all about identity. Male strength traditionally comes from arrogance and false pride, which naturally leads to insecurity, fear, and a need to constantly assert an upper hand, a need to be right. A much more secure stance is to recognize the power of the earth, and allow ourselves to serve that power, not to pretend to understand or control it.

TS: We agree that time is not on our side. What do you think is on our side?

TS: We agree that time is not on our side. What do you think is on our side?

MC: Three things: first, the planet wants to live. It wants biological diversity, abundance, and above all topsoil, and that’s what will provide any basis for life in the future. I think humans want to live, too; and more than just live, but be satisfied in living well. Civilization offers only a sorry substitute for living well to only a small minority.

The second is that activists now have a distinct advantage in that it’s easier to get information anonymously. The more that can be safely done with computers, including attacking computer systems, the better—but even if it’s just finding out whose machinery is where, how industrial systems are built and laid out, that’s much easier to come by. On the other hand the enemy has a similar advantage in surveillance and investigation, so security is more crucial than ever.

The third is that the easily accessible resources that empires need to function are all but gone. There will never be another age of cheap oil, iron ore mountains, abundant forest, and continents of topsoil. Once the infrastructure of civilized humanity collapses or is intentionally broken, it can’t really be rebuilt. Then humans will need to learn how to live in much smaller-scale cultures based on what the land can support and how justly they treat one another. That will be no utopia, of course, but it’s still humanity’s best option. The fight we’re now engaged in is over what living material will be available for those new, localized cultures—and more importantly, the larger nonhuman biological communities—to sustain themselves. What polar bears, salmon, and migratory birds need, we will also need. Our futures are forever linked.

Time is Short: Reports, Reflections & Analysis on Underground Resistance is a bulletin dedicated to promoting and normalizing underground resistance, as well as dissecting and studying its forms and implementation, including essays and articles about underground resistance, surveys of current and historical resistance movements, militant theory and praxis, strategic analysis, and more. We welcome you to contact us with comments, questions, or other ideas at undergroundpromotion@deepgreenresistance.org

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Apr 25, 2015 | Agriculture, Building Alternatives, Strategy & Analysis

In 1993 Michael Carter was arrested and indicted for underground environmental activism. Since then he’s worked aboveground, fighting timber sales and oil and gas leasing, protecting endangered species, and more. Today, he’s a member of Deep Green Resistance Colorado Plateau, and author of the memoir Kingfishers’ Song: Memories Against Civilization.

Time is Short spoke with him about his actions, underground resistance, and the prospects and problems facing the environmental movement. The first part of this interview is available here, and the third part here.

Time is Short: Your actions weren’t linked to other issues or framed in a greater perspective. How important do you think having well-framed analysis is in regards to sabotage and other such actions?

Michael Carter: It is the most important thing. Issue framing is one of the ways that dissent gets defeated, as with abortion rights, where the issue is framed as murder versus convenience. Hunger is framed as a technical difficulty—how to get food to poor people—not as an inevitable consequence of agriculture and capitalism. Media consumers want tight little packages like that.

In the early ‘90s, wilderness and biodiversity preservation were framed as aesthetic issues, or as user-group and special interests conflict; between fishermen and loggers, say, or backpackers and ORVers. That’s how policy decisions and compromises were justified, especially legislatively. My biggest aboveground campaign of that time was against a Montana wilderness bill, because of the “release language” that allowed industrial development of roadless federal lands. Yet most of the public debate revolved around an oversimplified comparison of protected versus non-protected acreage numbers. It appeared reasonable—moderate—because the issue was trivialized from the start.

That sort of situation persists to this day, where compromises between industry, government, and corporate environmentalists are based on political framing rather than biological or physical reality—an area that industry or motorized recreationists would agree to protect might have no capacity for sustaining a threatened species, however reasonable the acreage numbers might look. Activists feel obliged to argue in a human-centered context—that the natural world is our possession, whether for amusement or industry—which is a weak psychological and political position to be in, especially for underground fighters.

Artwork by Stephanie McMillan

When I was one of them, I never felt I had a clear stance to work from. Was I risking a decade in prison for a backpacking trail? No. Well then what was I risking it for? I chose not to think that deeply, just to rampage onward. That was my next worst mistake after bad security. Without clear intentions and a solid understanding of the situation, actions can become uncoordinated, and potentially meaningless. No conscientious aboveground movement will support them. You can get entangled in your own uncertainty.

If I were now considering underground action—and of course I’m not, you must choose to be aboveground or underground and stick with it, another mistake I made—I would view it as part of a struggle against a larger power structure, against civilization as a whole. It’s important to understand that this is not the same thing as humanity.

TS: You called civilization a plan based on agriculture. Could you expand on that?

MC: Nothing else that the dominant culture does, industrial forestry and fishing, generating electricity, extracting fossil fuels, is as destructive as agriculture. None of it’s possible without agriculture. There’s some forty years of topsoil left, and agriculture is burning through it as if it will last forever, and it can’t. Topsoil is the sand in civilization’s hourglass, the same as fossil fuels and mineral ores; there is only so much of it. When it comes to physical limits, civilization has no rationality, or even a sense of its own ultimate self-interest; only a hidden-in-plain-sight secret that it’s going to consume everything. In a finite world it can never function for long, and all it’s doing now is grinding through the last frontiers. If civilization is still continuing twenty years from now, it won’t matter how many wilderness areas are designated; civilization is going to consume those wilderness areas.

TS: How is that analysis helpful? If civilization can never be sustained, doesn’t that remove any hope of success?

MC: If we’re serious about protecting life and promoting justice, we have to acknowledge that civilized humanity will never voluntarily take the steps needed for a sustainable way of life, because its history is entirely about war and occupation. That’s what civilization does: wage war and occupy land. It appears as though this is progress, that it’s humanity itself, but it’s not. Civilization will always make power and dominance its priority, and will never allow its priority to be challenged.

Artwork by Stephanie McMillan

For example, production of food could be fairly easily converted from annual grains to perennial grasses, producing milk, eggs, and meat. Polyface Farms in Virginia has demonstrated how eminently possible this is; on a large scale that would do enormous good, sequestering carbon and lowering diabetes, obesity, and pesticide and fertilizer use. But grass can’t be turned into a commodity; it can’t be stored and traded, so it can never serve capitalism’s needs. So that debate will never come up on CNN, because it falls so far outside the issue framing. Hardly anyone is discussing what’s really wrong, only which capitalist or nation state will get to the last remaining resources first and how technology might cope with the resulting crises.

Another example is the proposed copper mine at Oak Flat, near Superior, Arizona. The Eisenhower administration made the land off-limits to mining in 1955, and in December 2014 the US Senate reversed that with a rider to a defense authorization bill, and Obama signed it. Arizona Senator John McCain said, “To maintain the strength of the most technologically-advanced military in the world, America’s armed forces need stable supplies of copper for their equipment, ammunition, and electronics.” See how he justifies mining copper with military need? He’s closed the discussion with an unassailable warrant, since no one in power—and hardly anyone in the public at large—is going to question the military’s needs.

TS: Are you saying there’s no chance of voluntary reform?

MC: I’m saying that it’s going to be a fight. Significant social change is usually involuntary, contrary to popular notions about “being the change you want to see in the world” and “majority rules.” Most southern whites didn’t want the US Civil Rights Movement to exist, much less succeed. In the United States democracy is mostly a fictional theory anyway, because a tiny financial and political elite run the show.

For example, in the somewhat progressive state of Oregon, the agriculture lobby successfully defeated a measure to label foods containing genetically modified organisms. A majority of voters agreed they shouldn’t know what’s in their food, their most intimate need, because those in power had enough money to convince them. There’s little hope in trying to reason with the people who run civilization, or who are otherwise trapped by it, politically or financially or however. So long as the ruling class is able to extract wealth from the land and our labor, they will. If they’ve got the machinery and fuel to run their economy, they will eventually find the political bypasses to make it happen. It will consume lives and land until there’s nothing left to consume. When the soil is gone, that’s essentially it for the human species.

Oak Flat, Arizona

What’s the point of compromising with a political system that’s patently insane? A more sensible way of approaching the planet’s predicament would be to base tactical decisions on a strategy to strip power from those who are destroying the planet. This is the root, what we have to mean when we call it a radical—root-focused—struggle.

Picture a world with no food, rising temperatures, disease epidemics, drought, war. We see it unfolding now. This is what we’re fighting against. Or rather we’re fighting for a world that can live, a world of forests and prairies and free flowing rivers that build and stabilize soil and sustain biological diversity and abundance. Our love of the world must be what guides us.

TS: You’re suggesting a struggle that completely changes how humans have arranged themselves, the end of the capitalist economy, the eventual collapse of the nation-state model of society. That sounds impossibly difficult. How might resisters approach that?

MC: We can begin by building a movement that functions as a cultural replacement for the culture we’re stuck in now. Since civilized culture isn’t going to support anyone trying to take it apart, we need other systems of material, psychological, and emotional support.

This would be particularly important for an underground movement. Ideally they would have a community that knows their secrets and works alongside them, just as militaries do. Building that network will be difficult to do in secret, because if they’re observing tight security, how do they even find others who agree with them? But because there’s little one or two people can do by themselves, they’ll have to find ways to do it. That’s a problem of logistics, however, and it’s important to separate it from personal issues.

When I was doing illegal actions, I wanted people to notice me as a hardcore environmentalist, which under the circumstances was foolish and narcissistic to the point of madness. If you have issues like that—and lots of people do, in our bizarre and hurtful culture—you need to resolve them with self-reflection and therapy, not activism. The most elegant solution would be for your secret community to support and acknowledge you, to help you find the strength and solidarity you need to do hard and necessary work, but there are substitutes available all the same.

TS: You’ve been involved with aboveground environmental work in the years since your underground actions. What have you worked on, and what are you doing now?

MC: I first got involved with forestry issues—writing timber sale appeals and that sort of thing. Later I helped write petitions to protect species under the Endangered Species Act. I burned out on that, though, and it took me a long time to get drawn back in. Aboveground people need the support of a community, too—more than ever. Derrick Jensen’s book A Language Older Than Words clarified the global situation for me, answered many questions I had about why things are so difficult right now. It taught me to be aware that as civilized culture approaches its end, people are getting ever more self-absorbed, apathetic, and cruel. Those who are still able to feel need to stand by each other as well as they can.

When Deep Green Resistance came into being, it was a perfect fit, and I’ve been focused on helping build that movement. Susan Hyatt and I are doing an essay series on the psychology of civilization, and how to cultivate the mental health needed for resistance. I’m also interested in positive underground propaganda. Having stories to support what people are doing and thinking is important. It helps cultivate the confidence and courage that activists need. That’s why governments publish propaganda in wartime; it works.

TS: So you think propaganda can be helpful?

MC: Yes, I do. The word has a negative connotation for some good reasons, but I don’t think that attempting to influence thoughts and actions with media is necessarily bad, so long as it’s honest. Nazi Germany used propaganda, but so did George Orwell and John Steinbeck. If civilization is brought down—that is, if the systems responsible for social injustice and planetary destruction are permanently disabled—it will require a sustained effort for many years by people who choose to act against most everything they’ve been taught to believe, and a willingness to risk their freedom and lives to bring it about. Entirely new resistance cultures will be needed. They will require a lot of new stories to sustain a vision of who humans really are, and what our lives are for, how they relate to other living things. So far as I know there’s little in the way of writing, movies, any sort of media that attempts to do that.

Edward Abbey wrote some fun books, and they were all we had; so we went along hoping we’d have some of that fun and that everything might come out all right in the end. We no longer have that luxury for self-indulgence. I’m not saying humor doesn’t have its place—quite the opposite—but the situation of the planet and social situation of civilization is now far more dire than it was during Abbey’s time. Effective propaganda should reflect that—it should honestly appraise the circumstances and realistically compose a response, so would-be resisters can choose what their role is going to be.

This is important for everyone, but especially important for an underground. In World War II, the Allies distributed Steinbeck’s propaganda novel The Moon is Down throughout occupied Europe. It was a short, simple book about how a small town in Norway fought against the Nazis. It was so mild in tone that Steinbeck was accused by some in the US government of sympathizing with the enemy for his realistic portrayal of German soldiers as mere people in an awful situation, and not superhuman monsters. Yet the occupying forces would shoot anyone on the spot if they caught them with a copy of the book. Compare that to Abbey’s books, and you see how far short The Monkey Wrench Gang falls of the necessary task.

TS: Can you suggest any contemporary propaganda?

Derrick Jensen’s Endgame books are the best I can think of, and the book Deep Green Resistance. There’s some negative-example propaganda worth mentioning, too. The book A Friend of the Earth, by T.C. Boyle. The movies “The East” and “Night Moves” are both about underground activists, and they’re terrible movies, at least as propaganda for effective resistance. “The East” is about a private security firm that infiltrates a cell whose only goals are theater and revenge, and “Night Moves” is even worse, about two swaggering men and one unprepared woman who blow up a hydroelectric dam.

The message is, “Don’t mess with this stuff, or you’ll end up dead.” But these films do point out some common problems of groups with an anarchistic mindset: they tend to belittle women and they operate without a coherent strategy. They’re in it for the identity, for the adrenaline, for the hook-up prospects—all terrible reasons to engage. So I suppose they’re worth a look for how not to behave. So is the documentary film “If a Tree Falls,” about the Earth Liberation Front.

Social change movements can suffer from problems of immaturity and self-infatuation just like individuals can. Radical environmentalism, like so many leftist causes, is rife with it. Most of the Earth First!ers I knew back in the ‘90s were so proud of their partying prowess, you couldn’t spend any time with them without their getting wasted and droning on about it all the next day. One of the reasons I drifted away from that movement was it was so full of arrogant and judgmental people, who seemed to spend most of their time criticizing their colleagues for impure living because they use paper towels or drive an old pickup instead of a bicycle.

This can lead to ridiculous guilt-tripping pissing matches. It’s no wonder environmentalists have such a bad reputation among the working class, when they’re indulging in self-righteous nitpicking that’s really just a reflection of their own circumstantial advantages and lack of focus on effectively defending the land. Tell a working mother to mothball her dishwasher because you heard it’s inefficient, see how far you get. It’s one of the worst things you can say to anyone, especially because it reinforces the collective-burden notion of responsibility for environmental destruction. This is what those in power want us to think. Developers build new golf courses in the desert, and we pretend we’re making a difference by dry-brushing our teeth. Who cares who’s greener than thou? The world is being gutted in front of our eyes.

Interview continues here.

Time is Short: Reports, Reflections & Analysis on Underground Resistance is a bulletin dedicated to promoting and normalizing underground resistance, as well as dissecting and studying its forms and implementation, including essays and articles about underground resistance, surveys of current and historical resistance movements, militant theory and praxis, strategic analysis, and more. We welcome you to contact us with comments, questions, or other ideas at undergroundpromotion@deepgreenresistance.org

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Mar 8, 2015 | Property & Material Destruction, Repression at Home, Strategy & Analysis

In 1993 Michael Carter was arrested and indicted for underground environmental activism. Since then he’s worked aboveground, fighting timber sales and oil and gas leasing, protecting endangered species, and more. Today, he’s a member of Deep Green Resistance Colorado Plateau, and author of the memoir Kingfishers’ Song: Memories Against Civilization.

Time is Short spoke with him about his actions, underground resistance, and the prospects and problems facing the environmental movement. Due to the length of the interview, we’ve presented it in three installments; go to Part II here, and Part III here.

Time is Short: Can you give a brief description of what it was you did?

Michael Carter: The significant actions were tree spiking—where nails are driven into trees and the timber company warned against cutting them—and sabotaging of road building machinery. We cut down plenty of billboards too, and this got most of the media attention. We did this for about two years in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, about twenty actions. My brother Sean was also indicted. The FBI tried to round up a larger conspiracy, but that didn’t stick.

TS: How did you approach those actions? What was the context?

MC: We didn’t know a lot about environmental issues or political resistance, so we didn’t have much understanding of context. We had an instinctive dislike of clear cuts, and we had the book The Monkey Wrench Gang. Other people were monkeywrenching, that is, sabotaging industry to protect wilderness, so we had some vague ideas about tactics but no manual, no concrete theory. We knew what Earth First! was, although we weren’t members. It was a conspiracy only in the remotest sense. We had little strategy and the actions were impetuous. If we’d been robbing banks instead, we’d have been shot in the act.

Nor did we really understand how bad the problem was. We thought that deforestation was damaging to the land, but we didn’t get the depth of its implications and we didn’t link it to other atrocities. We just thought that we were on the extreme edge of the marginal issue of forestry. This was before many were talking about global warming or ocean acidification or mass extinction. It all seemed much less severe than now, and of course it was. The losses since then, of species and habitat and pollution, are terrible. No monkeywrenching I know of did anything significant to stop that. It was scattered, aimed at minor targets, and had no aboveground political movement behind it.

Clearcuts in the Swan Valley, MT near Loon Lake on the slope of Mission Mountains. Photo by George Wuerthner.

TS: What was the public response to your actions?

MC: They saw them as vandalism, mindlessly criminal, even if they were politically motivated. This was before 9/11, before the Oklahoma City bombing; the idea of terrorism wasn’t so powerful, so our actions weren’t taken nearly as seriously as they would be now.

We were charged by the state of Montana with criminal mischief and criminal endangerment. The state’s evidence was solid enough we thought we couldn’t win a trial, so we pled guilty on the chance the judge wouldn’t send us to prison. Our defense was to say, “We’re sorry we did it, it was motivated by sincerity but it was dumb.” And that was true. We were able to get our charges reduced from criminal endangerment to criminal mischief. I got a 19 year suspended prison sentence, Sean got 9 years suspended. We both had to pay a lot of money, some $40,000, but I only spent three months in county jail and Sean got out of a jail sentence altogether. We were lucky.

TS: As you said, this was before the obsessive fear of terrorism. How do you think that played into your trial and indictment, and how do you think it would be different today?

MC: Had it happened after any big terrorism event, they would have sent us to prison, there’s no doubt about that. States have to maintain a level of constant fear and prove themselves able to protect citizens.

The irony was, I’m not sure I wanted to be serious—there seemed to be something protective in not being all that effective, in being intentionally quixotic, in being a little cute about it. There was a particularly comical aspect to cutting down billboards, and that was helpful only when I was arrested. It made it look less like terrorism and more like reckless things I did when I was drunk, and a lot of people approved of it because they thought billboards were tacky. I want to emphasize that cutting down billboards is nothing I’d advise anyone to consider, only that a little bit of public approval made a surprising difference to my morale, and may have positively influenced sentencing. But the point, of course, is to be effective and not get caught in the first place. These days, if someone gets caught in underground actions, they will be in a lot more trouble than ever before.

TS: How did you get caught?

We left fingerprints and tire tracks, we rented equipment under our own names—like an acetylene torch used to cut down steel billboard posts—and we told people who didn’t need to know about it. We assumed we were safe if they didn’t catch us in the act and because our fingerprints weren’t on file, and we couldn’t have been more wrong. The cops can subpoena anyone’s fingerprints, and use that evidence for something in the past. The importance of security can’t be overstated—and we didn’t have any. Even with a couple rudimentary precautions, we might have saved ourselves the whole ordeal of getting caught. If we’d read the security chapter of Dave Foreman’s book Ecodefense, I don’t think we would have even come under suspicion. Anyone taking any action, above- or underground, needs to take the time to learn security well.

It’s not just saving yourself the anguish of arrest and prison time. If you’re rigorous about security, you might be able to have a real chance at changing how the future of the planet plays out. You can have no impact at all in a jail cell. In our case, we definitely could have stopped timber sales with tree spiking even though that tactic was extremely unpopular politically. It was seen as an act of violence against innocent lumber mill workers instead of a preventative measure to protect forests. The dilemma never got past that stage, though. We had little chance of having any reasoned tactical considerations—let alone making reasoned decisions—because we were always a little too afraid of being caught. With good reason, it turns out.

TS: What have you learned from your experience? Looking back on what you did all those years ago, what’s your perspective on your actions now? Is there anything you would have done differently?

MC: Well I definitely would have taken steps to not get caught. I would have picked my targets more carefully, and I would have entered into an understanding with myself that while my enemy is composed of people, it’s only a system, inhuman and relentless. It can’t be reasoned with; it has no sanity, no sense of morality, no love of anything. Its job is to consume. I would have tried to focus on that guiding fact, and not on the people running it or who were dependent on it. I would have tried to find the weaknesses in the system, and then attacked those.

I’d have tried not to allow my emotions to dictate my strategy or actions. Emotions might get me there in the first place—I don’t think you could get to such a desperate point without a strong emotional response—but once I arrived at the decision to act, I would have done everything I could to think like a soldier, find a competent group to join with, and pick expensive and hard-to-replace targets.

TS: I assume you didn’t just wake up one day and decide to attack bulldozers and billboards. What was your path from being apolitical to having the determination and the passion to do what you did?

MC: When I was struggling with high school, my brother loaned me a stack of Edward Abbey books, which presented the idea that wilderness is the real world, precious above all else. The other part was living in northwest Montana, where you see deforestation anywhere you look. You can’t not notice it, and there’s something about those scalped hills and skid trails and roads that triggers a visceral, angry response. It’s less abstract than atmospheric carbon or drift-net fishing. You don’t see those things the way you see denuded mountainsides. My family heated the house with wood, and we would sometimes get it out of slash piles in the middle of clearcuts. I had lots of firsthand exposure to deforested land. I wondered why the Sierra Club didn’t do something about it, how it could be allowed. We would occasionally go to Canada, and it was even worse up there. No one can feel despair like a teenager, and I had it in spades. If Greenpeace won’t stop this, I reasoned, well then I will.

I started building an identity around this, though, and that’s disastrous for a person choosing underground resistance. You naturally want others to know and appreciate your feelings and accomplishments, especially when you’re young, but the dilemma underground fighters face is that they must present another, blander identity to the world. That’s hard to do.

TS: You were fairly isolated in your actions, and you’ve emphasized the importance of a larger context. Do you see those two ideas connecting? Do you think saboteurs should be acting in a larger movement?

MC: I think saving the planet relies completely on the coordinated actions of underground cells coupled with an aboveground political movement that isn’t directly involved in underground actions. When I was underground, I had no hope of building a network, mostly because of a lack of emotional and political maturity. I also didn’t have the technological or strategic savvy, or a means of communicating with others. The actions themselves were mostly symbolic, and symbolic actions are a huge waste of risk. They’re a waste of political capital too. Most everyone is going to disagree with underground activism and it’s not going to change anyone’s mind about the policy issue—hardly anything will—so it has to count in the material realm. If people are ready and willing to risk their lives and their freedom then they should fight to win, not just to make some sort of abstract point.

TS: After you were arrested, what support—if any—did you receive from folks on the outside, and what support would you have wanted to receive?

MC: The most important support was financial, but there wasn’t a lot of it. Our plea bargain didn’t guarantee we wouldn’t go to prison. We were also worried that the feds would indict us for racketeering, an anti-Mafia charge with serious minimum sentencing. If we’d had more legal defense financing we’d of course have felt a lot more secure, but twenty years of reflection tells me we didn’t really deserve it considering how poorly we executed the actions, what little effect they caused.

That sounds like I’m being awfully hard on myself, and hindsight is always 20/20, but the point is that a legal crisis is exhausting and expensive. Your community will question whether your actions are worthy of the price they’ll have to pay if you’re caught. My actions were not.

Even so, I appreciated any sort of support. Hearing from the outside in jail is better than you’d believe. A lot of Earth First! Journal readers sent me anonymous letters. I wrote back and forth with one of the women who was jailed for noncooperation with a federal grand jury investigating the Animal Liberation Front in Washington. Seeing approving letters to the editor in the papers was also great. Just knowing that the whole world isn’t your enemy, that someone is thinking about you and appreciates what you did, is priceless.

Artwork by Stephanie McMillan

TS: Do you still think militant and illegal forms of direct action and sabotage are justified? Why?

MC: I do, yes. In an ideal world I don’t think violence is the best way to accomplish anything, but obviously this isn’t an ideal world. Our circumstances are getting worse and worse—overpopulation, pollution, oceanic dead zones, you name it—and any options for a decent and dignified future for humanity are dwindling day by day, so what choice does that leave us? Individual attempts at sustainable living won’t work so long as the industrial system is running. The dismantling of infrastructure is the most important missing piece right now. It’s where the system is most vulnerable, so it should be employed right away. It can be effective, but it has to be responsible, careful, and extraordinarily smart.

One of the reasons underground political actions are so unpopular is that they’re always presented as attacks on individuals, rather than on a system. I think it’s important to reframe sabotage as strikes on an unjust, destructive system, and that civilization is not us, and not the highest expression of human endeavor, but only an idea. Civilization is masquerading as humanity, but that’s not what it is. Civilization is only one sort of cultural plan, a way of creating unsustainably large human settlements, based entirely on agriculture which itself is completely unsustainable.

The argument that militant actions are counterproductive has a little bit of merit because the scale they’ve happened on hasn’t been large enough to have any impact. For example, the Earth Liberation Front burning SUV’s. You’re left with the political fallout, the mainstream activists distancing themselves and all the other bad stuff that comes with it, but you don’t have any measurable gain, in reducing carbon emissions, say. Sabotage needs to happen on a larger scale, against more expensive targets, to be impactful. Fighters need to think big. That’s how militaries accomplish their goals—by acting against systems. They blow up bridges, they take out buildings, they disable the enemy arsenal, they kill the enemy—that’s how they function. I agree activists don’t want to identify with militarism, but it’s foolhardy to not consider what’s actually going to get the job done, and militaries know how to do that. No moral code will matter if the biosphere collapses. Doctrinal non-violence isn’t going to have any relevance in a world that’s 20 degrees hotter than it is now.

I wish an effective movement could be nonviolent, but we just don’t have enough social cohesion to orchestrate that kind of thing. There’s so few of us who give a shit, and we’re scattered, isolated, and disenfranchised. We don’t have adequate numbers, influence, or power, and I don’t see that changing. Everywhere we look we’re losing, because we don’t have a movement that can say, “No. You’re not going to do that. We will stop this, whatever it takes,” and back that up. Aboveground activists need to advocate a lesser evil, to continually pose the question of what is worse: that some property was destroyed, or that sea shells are dissolving in acid oceans? Underground activists need to act that out. It’s not a rhetorical question.

We need to remember, too, that small numbers of people can engineer profound changes when their actions are wisely leveraged. Very few took part in the resistance movements of World War II, but they made all the difference to ultimately defeating the Axis.

Interview continues here.

Time is Short: Reports, Reflections & Analysis on Underground Resistance is a bulletin dedicated to promoting and normalizing underground resistance, as well as dissecting and studying its forms and implementation, including essays and articles about underground resistance, surveys of current and historical resistance movements, militant theory and praxis, strategic analysis, and more. We welcome you to contact us with comments, questions, or other ideas at undergroundpromotion@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 16, 2015 | Human Supremacy, Strategy & Analysis

By Anonymous / Deep Green Resistance UK

In retrospect, all revolutions seem inevitable. Beforehand, all revolutions seem impossible.

—Michael McFaul, U.S. National Security Council

When I talk to people about the Deep Green Resistance (DGR) Decisive Ecological Warfare (DEW) strategy to end the destructive culture we know as industrial civilisation, I get comments like “So you want a revolution.” Some include the word “armed” or “violent” before “revolution.” I explain that DGR is advocating for militant resistance to industrial civilisation that will involves sabotage of infrastructure. We we are not advocating for the harming of any human or non-human living beings.

There are a number of ways that groups can challenge those who rule: revolutions, coup d’etats, rebellions, terrorism, non-violent resistance, insurgency, guerrilla warfare and civil war. This article will explore what causes revolutions, the stages of revolutions, communist revolutions, anarchist revolutions, the automatic revolution theory, and if a revolution is likely now. In future articles, we will explore what we can learn from studying past and present insurgency, guerrilla warfare, and non-violent resistance.

Methods for Challenging Those Who Rule

In Coup d’etat: A Practical Handbook, Edward Luttwak describes a coup d’etats (coup) as a method that: “Operates in that area outside the government but within the state which is formed by the permanent and professional civil service, the armed forces and the police. The aim is to detach the permanent employees of the state from the political leadership, and this can not usually take place if the two are linked by political, ethnic or traditional loyalties.” [1] So it’s about separating the permanent bureaucrat machinery of the state from the political leadership. The top decision-making offices are seized without changing the system of their predecessors.

Luttwak makes a distinction between revolutions, civil wars, pronunciamiento (a form of military rebellion particular to Spain, Portugal and Latin America in the nineteenth century), putsch (led by high ranking military officers), and a war of national liberation/insurgency. He explains that coups use some elements of all of these, but unlike them may not necessarily be assisted by the masses or a military or armed force. Those attempting a coup will not be in charge of the armed forces at the start of the coup and will hope to win their support if the coup is going to be successful. They will also not initially control any tools of propaganda so can’t count on the support of the people. Luttwak is clear that coups are politically neutral, so the policies of the new government can’t be predicted to be “right”or “left.”

The political scientist Samuel P. Huntington identifies three classes of coup d’etat:

1. Breakthrough coup d’etat—a revolutionary army overthrows a traditional government and creates a new bureaucratic elite.

2. Guardian coup d’etat—The stated aim of such a coup is usually improving public order and efficiency, and ending corruption.

3. Veto coup d’etat—occurs when the army vetoes the people’s mass participation and social mobilisation in governing themselves.

A list of Coup d’etats from the present going back to BC 876 are listed here. Well known examples are the Nazis in Germany in 1933 and the Iranian Revolution, 1978-‘79.

A rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is any act by group that refuses to recognise, or seeks to overthrow, the authority of the existing government. They can use violent or non-violent methods. Any attempts that fails to change a regime are called rebellions. Uprisings are usually unarmed or minimally armed popular rebellions. Insurrections generally involve some degree of military training and organisation, and the use of military weapons and tactics by the rebels. [2]

DGR members would never consider carrying out or advocating for terrorism. Most governments conduct state terrorism on a daily basis via the police, army, and the prison system, and DGR members are working against this in our aboveground organising. In Insurgency & Terrorism: From Revolution to Apocalypse, Bard E. O’Neill defines terrorism as “the threat or use of physical coercion, primarily against noncombatants, especially civilians, to create fear in order to achieve various political objectives.” [3]

In Insurgency & Terrorism: From Revolution to Apocalypse, O’Neill defines Insurgency as a “struggle between a nonruling group and the ruling authorities in which the nonruling group consciously uses political resources (e.g. organisational expertise, propaganda, and demonstrations) and violence to destroy, reformulate, or sustain the basis of legitimacy of one or more aspects of politics.” Recent examples are in Iraq and Palestine. [4]

And guerrilla warfare is described by O’Neill as “highly mobile hit-and-run attacks by lightly to moderately armed groups that seek to harass the enemy and gradually erode his will and capability. Guerrillas place a premium on flexibility, speed and deception.” Examples include Umkhonto we Sizwe, the armed wing of the African National Congress (ANC) in South Africa, and the Zapatistas in Mexico. [5]

In War of the Flea: The Classic Study of Guerrilla Warfare, Robert Taber describes a guerrilla fighter:

When we speak of the guerrilla fighter, we are speaking of the political partisan, an armed civilian whose principle weapon is not his rifle or his machete, but his relationship to the community, the nation in and for which he fights. Insurgency, or guerrilla war, is the agency of radical social or political change, it is the face and the right arm of the revolution. [6]

In The Politics of Nonviolent Action, Gene Sharp defines nonviolent action as “the belief that the exercise of power depends on the consent of the ruled who, by withdrawing that consent, can control and even destroy the power of their opponent. In other words, nonviolent action is a technique used to control, combat and destroy the opponent’s power by nonviolent means of wielding power.” [7] Well known nonviolent campaigns include the Gandhi’s Salt March campaign in 1930 and the US Civil Rights Movement of 1954–68.

A civil war is a conventional war between organised groups in the same state, which can include conflict between elements in the national armed forces. Both sides aim to take control of the country or region.

What Causes Revolutions?

Each of these methods or a combination of all may lead to a revolution. I find the word “revolution” a tired and overused concept. Everyone has a slightly different understanding of what a revolution is. The online Oxford dictionary defines a revolution as: “A forcible overthrow of a government or social order, in favor of a new system,” a complete change to the existing political system.

In Revolutions: A Very Short Introduction, Jack A. Goldstone defines a revolution “in terms of both observed mass mobilization and the institutional change, and a driving ideology carrying a vision of social justice. Revolution is the forcible overthrow of a government through mass mobilization (whether military or civilian or both) in the name of social justice, to create new political institutions.” Goldstone describes two great visions of revolutions, the heroic uprising of the downtrodden masses guided by leaders to overthrow unjust rulers. The second vision is eruptions of popular anger that produce violence and chaos. He observes that the history of revolutions shows both visions are present and they are vary widely. [8]

Professor Crane Brinton’s 1938 book The Anatomy of Revolution compares the English Revolution/Civil War, the American Revolution, the French Revolution, and the Russian Revolution of 1917. He identified a number of conditions that are present as causes for major revolutions. Many of the conditions are present now, including: general discontent; hopeful people accepting less than they hoped for; growing bitterness between social classes; governments not responding to the needs of society, and not managing their finances effectively.

Goldstone identifies five elements that result in a stable society becoming unstable, where the conditions for revolution are then favorable. These are:

1. poor management of finances;

2. alienation and opposition among the elites;

3. revolutionary mobilisation builds around some form of popular anger at injustice;

4. an ideology develops that mobalises diverse groups and presents a shared narrative of resistance;

5. a revolution requires favorable international relations.

In industrialised countries governments are clearly mismanaging their finances. This is combined with a general feeling of inequality in our society and the need for social change.

There still needs to be an event or events to lead to a revolution. Goldstone describes structural and transient causes. Structural causes are long-term and large-scale trends that erode social structures and relationships. Transient causes are chance events, by individuals or groups, which highlight the impact of longer term trends and encourage further resistance.

Structural Causes

1. Demographic change is a common structural change. Rapid population growth can produce large numbers of youth cohorts, who struggle to find work and are easily attracted to new ideologies for social change.

2. A shift in the pattern of international relations. War and international economic competition can weaken governments and empower new groups. Both of these causes can result in a number of states in a regional becoming unstable. Then if an event in one state results in a revolution, it can result in revolutionary outbreaks in others. These are known as revolutionary waves.

3. Uneven economic development. If the poor and middles classes fall noticeably far behind the elite, this may create popular grievances.

4. A new pattern of exclusion or discrimination against particular groups develops. For example if up-and-coming groups are excluded from joining the elite, they may look at other options.

5. The evolution of “personalist regimes” where the rulers hang onto power, relying on a small circle of corrupt family members and cronies. This will weaken or alienate the professional military and business elites.

Transient Causes

Transient causes are sudden events that push a society to become unstable. These can include: spikes in inflation, especially in food prices; defeat in war; and riots and demonstrations that challenge state authority. If the state is then seen to be repressing ordinary members of society with just grievances, it can lead to popular perceptions of the regime as dangerous, illegitimate, and unjust.

Transient events occur regularly in many countries and do not result in revolutions. Structural causes are needed to create the underlying instability, which allows the transient event to cause people to turn against the state more openly and in large numbers. [9]

The Stages of Revolutions

Brinton identifies revolutions having four stages: the Old Order, the Rule of the Moderates, then the Reign of Terror, and finally the Thermidorian Reaction (return of stability).

Goldstone also identifies four similar different stages: state breakdown, post revolution power struggle, new government consolidation, and a second radical phase some years after. He observes that strong and skillful leaders are needed to take advantage of the structural and transient causes if a revolution is to be successful. He identifies visionary and organisational leaders. Visionary leaders are prolific writers and generally brilliant public speakers, who articulate the faults of the old society and make a powerful case for change. Organisational leaders are great organisers of revolutionary armies and/or bureaucracies. They work out how to put the visionary leaders’ idea into practice. In some cases individuals act as both the visionary and organisational leader. [10]

Communist Revolutions

Revolutionary socialism is a view that revolution is necessary to transition from capitalism to socialism. This is not necessarily a violent event, but instead it is the seizure of political power by mass movements of the working class so they control the state. Social/Proletarian revolutions are generally advocated by socialists, communists, and some anarchists. Revolutionary socialism includes a number of social and political movements that may define “revolution” differently from one another.

A communist revolution is a proletarian revolution, generally inspired by the ideas of Marxism to replace capitalism with communism, with socialism as an intermediate stage. Marx believed that proletarian revolutions will inevitably happen in all capitalist countries.

Chapters 22 and 23 of Robert B Asprey’s War in the Shadows: The Guerrilla in History give a very useful summary of the Russian Revolution from 1825 to the October Revolution in 1917, then up to the end of the Russian Civil War in 1922. The Russian people had suffered many years of terrible conditions resulting in protests, uprisings and then harsh repression by a number of Russian Czars. Following Russia’s disastrous involvement in World War One, a St. Petersburg army garrison mutinied, leading to February Revolution and the end of the monarchy. A Provisional Government formed that continued Russia’s involvement in the war. The people had no desire to keep fighting but the new government did not seem to understand this. The October Revolution followed when the Bolsheviks, led by Lenin and Trotsky, took over the government. A civil war followed until 1922, with Lenin’s Red Army fighting to regain control of Russia against the Imperialist White armies and regional guerrilla dissidents, who were supported with troops from Britain, America, France and Italy. By 1922 the allied forces had left Russia and the White armies had been defeated. Lenin was left with a devastated Russia, industry at a standstill, inflation, agriculture at an all-time low and large peasant revolts in 1920-‘21. Droughts caused widespread famine in 1921-‘22, and it’s estimated that five million people died from starvation. [11]

There is a clear pattern of communist revolutions resulting in authoritarian, repressive governments. And most communist states have eventually had to give into Capitalism. The World Revolution that Marx dreamed of looks very unlikely.

Anarchist Revolutions

Anarchism is a political philosophy that aims to create stateless societies often defined as self-governed voluntary institutions. The International Anarchist Federation (IFA) fights for “the abolition of all forms of authority whether economic, political, social, religious, cultural or sexual. The construction of a free society, without classes or States or frontiers, founded on anarchist federalism and mutual aid. The action of the IAF—IFA shall always be based on direct action, against parliamentarism and reformism, both on a theoretical and practical point of view.”

Insurrectionary Anarchism is based on belief that the state will not wither away: “Attack is the refusal of mediation, pacification, sacrifice, accommodation and compromise in struggle. It is through acting and learning to act, not propaganda, that we will open the path to insurrection—although obviously analysis and discussion have a role in clarifying how to act. Waiting only teaches waiting; in acting one learns to act. Yet it is important to note that the force of an insurrection is social, not military.” [12]

Michael Schmidt’s recent book The Cartography of Revolutionary Anarchism describes five waves of Anarchism. [13] He describes a number of Anarchist Revolutions: the Mexican Revolution 1910-‘20, the Anarchist uprising against the Bolsheviks 1917-‘21, Ukrainian Revolution and Free Territory/Makhnovia 1917-‘21, Manchurian Revolution in Northeast Asia 1929-‘31, Spanish Revolution 1936-‘39, and the Chiapas conflict/Zapatista uprising in southern Mexico 1994.

In 2007 a group calling itself the Invisible Committee released The Coming Insurrection. It describes the decline of capitalism and civilisation through seven circles of alienation: self, social relations, work, the economy, urbanity, the environment, and civilisation. It then goes on to describe how a revolutionary struggle may evolve through “communes” – a general term to mean any group of people coming together to take on a task – to form into an underground network out of sight and then carry out acts of sabotage and confrontation with the state.

Automatic Revolution Theory

Ted Trainer’s recent article [14] encourages the Transition movement to think more radically and describes the “automatic revolution” theory: “If more and more people join in gradually building up alternative systems, then eventually it will all somehow have added up to revolution and the existence of the new society we want to see.”

This sums up the majority of the liberal environmental movement very well; a sort of blind faith that if enough positive stuff is done and the movement gets enough people on board, it will lead to a sustainable society. It doesn’t seem to consider the ongoing, wholesale destruction happening to the natural world or that we are fast approaching—or may have passed—the point of no return for runaway climate change. Most liberal environmentalists want a new sustainable society with all the comforts and conveniences that they currently have. So, by default, they want to reform the current system, which is nonrevolutionary. Reformists aim to change policies that determine how economic, psychological, and political benefits of a society are distributed. That’s not going to work for the environmental crisis.

To have a truly sustainable society, industrial civilisation needs to end. Otherwise, it will consume all resources that can be extracted from the earth and result in a devastated world that can not support life. The wars, death and suffering in the medium term will be horrific. Also it’s not that it’s just going to get hot—and it is going to get hot, even if we stop emitting greenhouse gases now—but climate change is going to cause the seasons to become erratic, and that’s a serious problem for growing food.

Revolution now?

A number of writers, journalists and celebrities are now calling for revolt or revolution in response to the environmental crisis. Of course each has their own interpretation of what “revolution” means. Naomi Klein recently observed that how climate science is telling us all to revolt. Chris Hedges argues that the system is unreformable and our only choice is mass civil disobedience. Comedian Russell Brand is now talking about the need for a revolution.

Robert Steele, former Marine and ex-CIA case officer, believes that the preconditions for revolution exist in most western countries: “What revolution means in practical terms is that balance has been lost and the status quo ante is unsustainable. There are two ‘stops’ on greed to the nth degree: the first is the carrying capacity of Earth, and the second is human sensibility. We are now at a point where both stops are activating.”

DGR Strategy—Decisive Ecological Warfare (DEW)

Where does DGR’s Strategy Decisive Ecological Warfare fit into all this? First, are the preconditions for revolution present? Well it depends where you look. If we focus on the industrialised world and work from Brinton and Goldstone’s criteria, and Steele’s analysis, then yes, that’s where we’re heading. What form might it take—violent or nonviolent, mass movement or guerrilla warfare?

Noam Chomsky believes that if a revolution is going to be possible then “it has to have dedicated support by a large majority of the population. People who have come to realize that the just goals that they are trying to attain cannot be attained within the existing institutional structure because they will be beaten back by force. If a lot of people come to that realization then they might say well we’ll go beyond, what’s called reformism, the effort to introduce changes within the institutions that exist. At that point the questions at least arise. But we are so remote from that point that I don’t even see any point speculating about it and we may never get there.”

We in DGR would agree with Chomsky that in the West, we are far away from a large majority of people calling for a just, truly sustainable world and accepting the radical consequences of this. The environmental movement has been trying to tackle the issues using a range of nonviolent methods for decades and is failing. So we urgently need to look at what other methods could work.

Militant Resistance—Sabotage

In 1960 Nelson Mandela was tasked by the ANC in setting up its military wing called Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK). I find his thoughts on the direction MK could take very useful:

In planning the direction and form that MK would take, we considered four types of violent activities: sabotage, guerrilla warfare, terrorism and open revolution. For a small and fledgling army, open revolution was inconceivable. Terrorism inevitably reflected poorly on those who used it, undermining any public support it might otherwise garner. Guerrilla warfare was a possibility, but since the ANC had been reluctant to embrace violence at all, it made sense to start with the form of violence that inflicted the least harm against individuals: sabotage.

Because Sabotage did not involve loss of life, it offered the best hope for reconciliation among the races afterwards… Sabotage had the added virtue of requiring the least manpower.

[15]

If we look at today’s situation in industrialised countries, guerrilla warfare and open revolution are not possible and terrorism is not acceptable, which leaves sabotage. The DEW strategy is made up of four phases, with an aboveground movement and underground network working in tandem. The aboveground groups indirectly support the underground network, although there is no direct contact between the two. The aboveground movement is made up from many groups working on land restoration, ending oppression, legally working to stop environmental destruction, community resilience including meeting basic needs and alternative institutions. An underground network would be made up of a variety of autonomous cells to carry out acts of sabotage against destructive infrastructure. The fossil fuels need to be left in the ground and the destruction of the natural world needs to stop. (include stuff about veterans saying DEW could work).

We do not believe there is any way to reform this insane culture. DGR is calling for revolutionary, systemic change. We would prefer a nonviolent transition to a truly sustainable society, but because this looks unlikely industrial civilisation needs to end and the most effective way to do this is through the sabotage of infrastructure by an underground network. If successful, DGR’s devolutionary strategy will indirectly result in a complete change to the existing political system, a reset. It is indirect because we are not advocating for armed militancy to overthrow any governments like past revolutions or for a strategy of attrition. But instead for underground cells to strategically target infrastructure weak points to cause system disruption and cascading system failures, resulting in the collapse of industrial activity and civilisation. It’s time for all environmentalists to decide if they want systemic change or to keep trying to reform the unreformable.

Finally, I’d like to quote Frank Coughlin’s description of the Zapatistas idea of revolution:

It is based in the “radical” idea that the poor of the world should be allowed to live, and to live in a way that fits their needs. They fight for their right to healthy food, clean water, and a life in commune with their land. It is an ideal filled with love, but a specific love of their land, of themselves, and of their larger community. They fight for their land not based in some abstract rejection of destruction of beautiful places, but from a sense of connectedness. They are part of the land they live on, and to allow its destruction is to concede their destruction. They have shown that they are willing to sacrifice, be it the little comforts of life they have, their liberty, or their life itself.

Endnotes

1. P19 – Luttwak, Edward. (1988) Coup d’etat: A Practical Handbook. Cambridge, USA. Harvard University Press.

2. P8 – Goldstone, Jack A. (2014) Revolutions: A Very Short Introduction, New York, Oxford University Press

3. P33 – O’Neill, Bard E. (2005) Insurgency & Terrorism: From Revolution to Apocalypse. 2nd Ed. Washington, D.C. Potomac Books.

4. P15 – O’Neill, Bard E. (2005) Insurgency & Terrorism: From Revolution to Apocalypse. 2nd Ed. Washington, D.C. Potomac Books.

5. P35 – O’Neill, Bard E. (2005) Insurgency & Terrorism: From Revolution to Apocalypse. 2nd Ed. Washington, D.C. Potomac Books.

6. P10 – Taber, Robert. (2002) War of the Flea: The Classic Study of Guerrilla Warfare. Washington, D.C. Potomac Books.

7. P4 – Sharp, Gene. (1973) The Politics of Nonviolent Action. Boston. Porter Sargent Publisher.

8. P1 – Goldstone, Jack A. (2014) Revolutions: A Very Short Introduction, New York, Oxford University Press

9. P20 – Goldstone, Jack A. (2014) Revolutions: A Very Short Introduction, New York, Oxford University Press

10. P26 – Goldstone, Jack A. (2014) Revolutions: A Very Short Introduction, New York, Oxford University Press

11. P284 Asprey, Robert B. (1975) War in the Shadows: The Guerrilla in History. New York. Doubledday & Company, Inc.

12. From Do or Die Issue 10. http://www.eco-action.org/dod/no10/anarchy.htm. Also read more about Insurrectionary Anarchism here: http://www.ainfos.ca/06/jul/ainfos00232.html).

13. Schmidt, Michael. (2013) Cartography of Revolutionary Anarchism. Oakland. AK Press. Anarchist Revolutionary Waves. The First Wave 1868-1894, Second Wave 1895-1923, Third Wave 1924-1949, Fourth Wave 1950-1989 and the Fifth Wave 1989 to the Present

14. Ted Trainer article – Transition Townspeople, We Need To Think About Transition: Just Doing Stuff Is Far From Enough! http://blog.postwachstum.de/transition-townspeople-we-need-to-think-about-transition-just-doing-stuff-is-far-from-enough-20140801

15. Mandela, Nelson. (1995) Long Walk to Freedom: The Autobiography of Nelson Mandela. London. Abacus.

Time is Short: Reports, Reflections & Analysis on Underground Resistance is a biweekly bulletin dedicated to promoting and normalizing underground resistance, as well as dissecting and studying its forms and implementation, including essays and articles about underground resistance, surveys of current and historical resistance movements, militant theory and praxis, strategic analysis, and more. We welcome you to contact us with comments, questions, or other ideas at undergroundpromotion@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 6, 2014 | Property & Material Destruction

By Norris Thomlinson / Deep Green Resistance Hawai’i

To most of us with no military experience, the Decisive Ecological Warfare strategy (DEW) of Deep Green Resistance can seem abstract. The aboveground efforts of rebuilding local food systems, local economies, and local decision making are straight-forward and well known to citizens engaged in any sort of social justice or environmental activity. More confrontational public direct action and nonviolent civil disobedience are familiar to most activists, from historical examples of women’s suffrage and civil rights movements to modern fights like the tar sands blockade and the Unis’tot’en Camp. However, the crucial underground role of directly attacking critical infrastructure, though it sounds exciting in theory, has little grounding in our daily experience or even in the history we’ve learned.

This is probably a deliberate omission from our history books, as sabotage is a highly effective tactic for small groups, outnumbered and outsupplied by opposing forces. In any situation of asymmetric warfare, sabotage plays an important role. This is precisely why the DEW strategy depends on one or more underground resistance groups carrying out unpredictable attacks on infrastructure to cause cascading systems failures. The aboveground work of slowing down destruction and building alternatives is crucial to easing the transition to a sane and sustainable way of living, but only decisive action by an underground can stop the entire juggernaut of industrial civilization in the time available to us before complete biotic collapse.

In 1987, Captain Howard Douthit III of the US Air Force published a thesis on “The Use and Effectiveness of Sabotage As a Means of Unconventional Warfare – An Historical Perspective From World War I Through Viet Nam.” Douthit performed an extensive literature search on the subject, and his report describes historical concepts and many specific instances of sabotage. He makes the subject much more accessible to the layperson, and demonstrates the effectiveness of sabotage in a wide range of circumstances.

Douthit provides summaries of different aspects of historical sabotage, distinguishing between forms such as passive (carried out by people forced to work for the occupying power) vs active, land-based vs aquatic targets, and targets of vehicles vs industry vs utilities. He found that among the most often used (and presumably most effective) forms of active sabotage were the use of explosives and mines, cutting power and communications lines, and arson. The most common targets included fuel depots, supply warehouses, oil pipelines, ships, railway infrastructure and trains, roads (including bridges & tunnels), communications infrastructure, and electrical facilities.

Sabotage groups that were better organized, trained, and supplied were able to pull off more complex and effective actions, often causing disruptions behind enemy lines in coordination with traditional military maneuvers on the front lines. But even small, amateur, destitute groups such as the Viet Cong were able to leverage the little they had to inflict disproportionate damage on their enemies.

Conventional forces had an extremely difficult time preventing the sabotage:

The only countermeasure that stopped sabotage was the manpower-prohibitive act of exterminating the saboteurs. Committing the number of forces necessary for effective counter-sabotage also produced too much of a drain on the front line. Indeed, as this fact became known, sabotage efforts increased in a deliberate move to force the enemy to guard against sabotage in the rear area. Thus, this research indicated there were no effective countermeasures to sabotage.

Douthit concludes:

[H]istory supported the thesis that sabotage is an effective means of warfare. Sabotage was used against both strategic and tactical targets. It was proven capable of being used near the front line, in the rear areas, and even in support areas out of the theater.

[…]

Sabotage can be used against both tactical and strategic targets.

Any nation, rich or poor, large or small can effect sabotage against an aggressor.

Sabotage is an economical form of warfare, requiring only a mode of transportation (possibly walking), a properly trained individual, and an applicable sabotage device.

To read more, download the PDF of “The Use and Effectiveness of Sabotage As a Means of Unconventional Warfare” (6.3 MB). For a detailed review of sabotage operations organized by chronological period and by country, start reading at page 13 of the report (page 25 in the PDF), or jump straight to the conclusions starting on page 92 (104 in the PDF).