by DGR News Service | Aug 15, 2022 | ANALYSIS, The Problem: Civilization

We were warned for decades about the death march we are on because of global warming. And yet, the global ruling class continues to frog-march us towards extinction.

By Chris Hedges / ScheerPost

The past week has seen record-breaking heat waves across Europe. Wildfires have ripped through Spain, Portugal and France. London’s fire brigade experienced its busiest day since World War II. The U.K. saw its hottest day on record of 104.54 Fahrenheit. In China, more than a dozen cities issued the “highest possible heat warning” this weekend with over 900 million people in China enduring a scorching heat wave along with severe flooding and landslides across large swathes of southern China. Dozens of people have died. Millions of Chinese have been displaced. Economic losses run into the billions of yuan. Droughts, which have destroyed crops, killed livestock and forced many to flee their homes, are creating a potential famine in the Horn of Africa. More than 100 million people in the United States are under heat alerts in more than two dozen states from temperatures in the mid-to-upper 90s and low 100s. Wildfires have destroyed thousands of acres in California. More than 73 percent of New Mexico is suffering from an “extreme” or “severe” drought. Thousands of people had to flee from a fast-moving brush fire near Yosemite National Park on Saturday and 2,000 homes and businesses lost power.

It is not as if we were not warned. It is not as if we lacked scientific evidence. It is not as if we could not see the steady ecological degeneration and species extinction. And yet, we did not act. The result will be mass death with victims dwarfing the murderous rampages of fascism, Stalinism and Mao Zedong’s China combined. The desperate response is to burn more coal, especially with the soaring cost of natural gas and oil, and extend the life of nuclear power plants to sustain the economy and produce cool air. It is a self-defeating response. Joe Biden has approved more new oil drilling permits than Donald Trump. Once the power outages begin, as in India, the heat waves will exact a grim toll.

“Half of humanity is in the danger zone, from floods, droughts, extreme storms and wildfires,” U.N Secretary General António Guterres told ministers from 40 countries meeting to discuss the climate crisis on July 18. “No nation is immune. Yet we continue to feed our fossil fuel addiction.”

“We have a choice,” he added. “Collective action or collective suicide.”

The Anthropocene Age – the age of humans, which has caused extinctions of plant and animal species and the pollution of the soil, air and oceans – is accelerating. Sea levels are rising three times faster than predicted. The arctic ice is vanishing at rates that were unforeseen. Even if we stop carbon emissions today – we have already reached 419 parts per million – carbon dioxide concentrations will continue to climb to as high as 550 ppm because of heat trapped in the oceans. Global temperatures, even in the most optimistic of scenarios, will rise for at least another century. This assumes we confront this crisis. The earth is becoming inhospitable to most life.

The average global temperature has risen by about 1.1 Celsius (1.9 degrees Fahrenheit) since 1880. We are approaching a tipping point of 2 degrees Celsius when the biosphere will become so degraded nothing can save us.

The ruling class for decades denied the reality of the climate crisis or acknowledged the crisis and did nothing. We sleepwalked into catastrophe. Record heat waves. Monster droughts. Shifts in rainfall patterns. Declining crop yields. The melting of the polar ice caps and glaciers resulting in sea level rise. Flooding. Wildfires. Pandemics. The breakdown of supply chains. Mass migrations. Expanding deserts. The acidification of the oceans that extinguishes sea life, the food source for billions of people. Feedback loops will see one environmental catastrophe worsen another environmental catastrophe. The breakdown will be nonlinear. These are the harbingers of the future.

Social coercion and the rule of law will disintegrate. This is taking place in many parts of the global south. A ruthless security and surveillance apparatus, along with heavily militarized police, will turn industrial nations into climate fortresses to keep out refugees and prevent uprisings by an increasingly desperate public. The ruling oligarchs will retreat to protected compounds where they will have access to services and amenities, including food, water and medical care, denied to the rest of us.

Voting, lobbying, petitioning, donating to environmental lobby groups, divestment campaigns and protesting to force the global ruling class to address the climate catastrophe proved no more effective than scrofula victims’ superstitious appeals to Henry VIII to cure them with a royal touch. In 1900 the burning of fossil fuel – mostly coal – produced about 2 billion tons of carbon dioxide a year. That number had risen threefold by 1950. Today the level is 20 times higher than the 1900 figure. During the last 60 years the increase in CO2 was an estimated 100 times faster than what the earth experienced during the transition from the last ice age.

The last time the earth’s temperature rose 4 degrees Celsius, the polar ice caps did not exist and the seas were hundreds of feet above their current levels.

You can watch my two-part interview with Roger Hallam, the co-founder of the resistance group Extinction Rebellion, on the climate emergency here and here.

There are three mathematical models for the future: a massive die-off of perhaps 70 percent of the human population and then an uneasy stabilization; extinction of humans and most other species; an immediate and radical reconfiguration of human society to protect the biosphere. This third scenario is dependent on an immediate halt to the production and consumption of fossil fuels, converting to a plant-based diet to end the animal agriculture industry – almost as large a contributor to greenhouse gasses as the fossil fuel industry – greening the deserts and restoring rainforests.

We knew for decades what harnessing a hundred million years of sunlight stored in the form of coal and petroleum would do to the climate. As early as the 1930s British engineer Guy Stewart Callendar suggested that increased CO2 was warming the planet. In the late 1970s into the 1980s, scientists at companies such as Exxon and Shell determined that the burning of fossil fuels was contributing to rising global temperature.

“[T]here is concern among some scientific groups that once the effects are measurable, they might not be reversible and little could be done to correct the situation in the short term,” a 1982 internal briefing for Exxon’s management noted.

NASA’s Dr. James Hansen told the U.S. Senate in 1988 that the buildup of CO2 and other gasses were behind the rise in heat.

But by 1989 Exxon, Shell and other fossil fuel corporations decided the risks to their profits from major curbs in fossil fuel extraction and consumption was unacceptable. They invested in heavy lobbying and funding of faux research and propaganda campaigns to discredit the science on the climate emergency.

Christian Parenti in his book Tropic of Chaos: Climate Change and the New Geography of Violence quotes from “The Age of Consequences: The Foreign Policy and National Security Implications of Global Climate Change,” a 2007 report produced by the Center for Strategic and International Studies and the Center for a New American Security. R. James Woolsey, former director of the Central Intelligence Agency, writes in the report’s final section:

In a world that sees two meter sea level rise, with continued flooding ahead, it will take extraordinary effort for the United States, or indeed any country, to look beyond its own salvation. All of the ways in which human beings have dealt with natural disasters in the past…could come together in one conflagration: rage at government’s inability to deal with the abrupt and unpredictable crises; religious fervor, perhaps even a dramatic rise in millennial end-of-day cults; hostility and violence towards migrants and minority groups, at a time of demographic change and increased global migration; intra-and interstate conflict over resources, particularly food and fresh water. Altruism and generosity would likely be blunted.

The profits from fossil fuels, and the lifestyle the burning of fossil fuels afforded to the privileged on the planet, overrode a rational response. The failure is homicidal.

Clive Hamilton in his Requiem for a Species: Why We Resist the Truth About Climate Change describes a dark relief that comes from accepting that “catastrophic climate change is virtually certain.”

“But accepting intellectually is not the same as accepting emotionally the possibility that the world as we know it is headed for a horrible end,” Hamilton writes. “It’s the same with our own deaths; we all ‘accept’ that we will die, but it is only when death is imminent that we confront the true meaning of our mortality.”

Environmental campaigners, from The Sierra Club to 350.org, woefully misread the global ruling class, believing they could be pressured or convinced to carry out the seismic reconfigurations to halt the descent into a climate hell. These environmental organizations believed in empowering people through hope, even if the hope was based on a lie. They were unable or unwilling to speak the truth. These climate “Pollyannas,” as Hamilton calls them, “adopt the same tactic as doom-mongers, but in reverse. Instead of taking a very small risk of disaster and exaggerating it, they take a very high risk of disaster and minimize it.”

Humans have inhabited cities and states for 6,000 years, “a mere 0.2 percent of the two and a half million years since our first ancestor sharpened a stone,” the anthropologist Ronald Wright notes in A Short History of Progress. The myriad of civilizations built over these 6,000 years have all decayed and collapsed, most through a thoughtless depletion of the natural resources that sustained them.

The latest iteration of global civilization was dominated by Europeans, who used industrial warfare and genocide to control much of the planet. Europeans and Euro-Americans launched a 500-year-long global rampage of conquering, plundering, looting, exploiting and polluting the earth – as well as killing the indigenous communities, the caretakers of the environment for thousands of years – that stood in the way. The mania for ceaseless economic expansion and exploitation, accelerated by the Industrial Revolution two and a half centuries ago, has become a curse, a death sentence.

Anthropologists, including Joseph Tainter in The Collapse of Complex Societies, Charles L. Redman in Human Impact on Ancient Environments and Ronald Wright in A Short History of Progress, have laid out the familiar patterns that lead to systems breakdown. Civilizations, as Tainter writes, are “fragile, impermanent things.” Collapse, he writes, “is a recurrent feature of human societies.”

This time the whole planet will go down. There will, with this final collapse, be no new lands left to exploit, no new peoples to subjugate or new civilizations to replace the old. We will have used up the world’s resources, leaving the planet as desolate as the final days of a denuded Easter Island.

Collapse comes throughout human history to complex societies not long after they reach their period of greatest magnificence and prosperity.

“One of the most pathetic aspects of human history is that every civilization expresses itself most pretentiously, compounds its partial and universal values most convincingly, and claims immortality for its finite existence at the very moment when the decay which leads to death has already begun,” the theologian Reinhold Niebuhr writes in Beyond Tragedy: Essays on the Christian Interpretation of Tragedy.

The very things that cause societies to prosper in the short run, especially new ways to exploit the environment such as the invention of irrigation or use of fossil fuels, lead to disaster in the long run. This is what Wright calls the “progress trap.”

“We have set in motion an industrial machine of such complexity and such dependence on expansion,” Wright notes, “that we do not know how to make do with less or move to a steady state in terms of our demands on nature.”

The U.S. military, intent on dominating the globe, is the single largest institutional emitter of greenhouse gasses, according to a report from Brown University. This is the same military that has designated global warming a “threat multiplier” and “an accelerant of instability or conflict.”

The powerlessness many will feel in the face of ecological and economic chaos will unleash further collective delusions, such as fundamentalist beliefs in a god or gods who will come back to earth and save us. The Christian right provides a haven for this magical thinking. Crisis cults spread rapidly among Native American societies in the later part of the 19th century as the buffalo herds and the remaining tribes faced extermination. The Ghost Dance held out the hope that all the horrors of white civilization — the railroads, the murderous cavalry units, the timber merchants, the mine speculators, the hated tribal agencies, the barbed wire, the machine guns, even the white man himself — would disappear. Our psychological hard wiring is no different.

The greatest existential crisis of our time is to at once be willing to accept the bleakness before us and resist. The global ruling class has forfeited its legitimacy and credibility. It must be replaced. This will require sustained mass civil disobedience, such as those mounted by Extinction Rebellion, to drive the global rulers from power. Once the rulers see us as a real threat they will become vicious, even barbaric, in their efforts to cling to their positions of privilege and power. We may not succeed in halting the death march, but let those who come after us, especially our children, say we tried.

Chris Hedges is a Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist who was a foreign correspondent for fifteen years for The New York Times, where he served as the Middle East Bureau Chief and Balkan Bureau Chief for the paper. He previously worked overseas for The Dallas Morning News, The Christian Science Monitor, and NPR. He is the host of show The Chris Hedges Report.

Photo by Catalin Pop on Unsplash.

by DGR News Service | Jun 25, 2022 | ANALYSIS, The Problem: Civilization

Editor’s note: Marxism and Collapse is a new organization formed “for information and debate on the scientific sources surrounding the existential problems facing humanity in the short term (ecological crisis, energy collapse, overpopulation, resource depletion, pandemics, atomic war) and the need for a new strategic programmatic framework in the face of an inevitable nearby process of civilisational collapse and human extinction.” They reached out to Deep Green Resistance member Max Wilbert recently and invited him to participate in this written debate with Noam Chomsky and Miguel Fuentes. His comments are published here for the first time.

A few notes. First, while it is impossible to work for social change without contending with Marx and his legacy, Deep Green Resistance is not a Marxist organization. Although several of our organizers do consider themselves Marxists, others reject Marxism. Nonetheless, we see great value in dialogue with Marxist organizations and communities, just as we value in dialogue with Conservative or Libertarian organizations. Open dialogue, debate, and discussion is essential, and we are glad to see some strains of Marxism beginning to seriously contend with the unfolding ecological crisis.

Second, this debate includes comments from Guy McPherson, a man who Deep Green Resistance cut ties with after allegations surfaced of sexual misconduct. We would have preferred to remove McPherson’s comments, but left them here at the insistence of Marxism and Collapse. Be wary of this man.

This is part 1 of a 2 part written debate.

Introduction

The following is the first part of the interview-debate “Climate Catastrophe, Collapse, Democracy and Socialism” between the linguist and social scientist Noam Chomsky, one of the most important intellectuals of the last century, the Chilean social researcher and referent of the Marxist-Collapsist theoretical current Miguel Fuentes, and the American scientist Guy McPherson, a specialist in the topics of the ecological crisis and climate change. One of the most remarkable elements of this debate is the presentation of three perspectives which, although complementary in many respects, offer three different theoretical and political-programmatic approaches to the same problem: the imminence of a super-catastrophic climate change horizon and the possibility of a near civilisational collapse. Another noteworthy element of this debate is the series of interpretative challenges to which Chomsky’s positions are exposed and that give this discussion the character of a true “ideological contest” between certain worldviews which, although as said before common in many respects, are presented as ultimately opposed to each other. In a certain sense, this debate takes us back, from the field of reflection on the ecological catastrophe, to the old debates of the 20th century around the dilemma between “reform or revolution”, something that is undoubtedly necessary in the sphere of contemporary discussions of political ecology.

Question 1:

Marxism and Collapse: In a recent discussion between ecosocialist stances and collapsist approaches represented by Michael Lowy (France), Miguel Fuentes (Chile) and Antonio Turiel (Spain), Lowy constantly denied the possibility of a self-induced capitalist collapse and criticized the idea of the impossibility of stopping climate change before it reaches the catastrophic level of 1.5 centigrade degrees of global warming. Do you think that the current historical course is heading to a social global downfall comparable, for example, to previous processes of civilization collapse or maybe to something even worse than those seen in ancient Rome or other ancient civilizations? Is a catastrophic climate change nowadays unavoidable? Is a near process of human extinction as a result of the overlapping of the current climate, energetic, economic, social and political crisis and the suicidal path of capitalist destruction, conceivable? (1) (Marxism and Collapse)

Noam Chomsky:

The situation is ominous, but I think Michael Lowy is correct. There are feasible means to reach the IPPC goals and avert catastrophe, and also moving on to a better world. There are careful studies showing persuasively that these goals can be attained at a cost of 2-3% of global GDP, a substantial sum but well within reach – a tiny fraction of what was spent during World War II, and serious as the stakes were in that global struggle, what we face today is more significant by orders of magnitude. At stake is the question whether the human experiment will survive in any recognizable form.

The most extensive and detailed work I know on how to reach these goals is by economist Robert Pollin. He presents a general review in our joint book Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal. His ideas are currently being implemented in a number of places, including some of the most difficult ones, where economies are still reliant on coal. Other eco-economists, using somewhat different models, have reached similar conclusions. Just recently IRENA, —the International Renewable Energy Agency, part of the UN– came out with the same estimate of clean energy investments to reach the IPCC goals.

There is not much time to implement these proposals. The real question is not so much feasibility as will. There is little doubt that it will be a major struggle. Powerful entrenched interests will work relentlessly to preserve short-term profit at the cost of incalculable disaster. Current scientific work conjectures that failure to reach the goal of net zero Carbon emissions by 2050 will set irreversible processes in motion that are likely to lead to a “hothouse earth,” reaching unthinkable temperatures 4-5º Celsius above pre-industrial levels, likely to result in an end to any form of organized human society.

Miguel Fuentes:

Noam Chomsky highlights the possibility of a global warming that exceeds 4-5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels within this century in his previous response, which according to him could mean, literally, the end of all forms of organised human society. Chomsky endorses what many other researchers and scientists around the world are saying. A recent report by the Breakthrough National Centre for Climate Restoration, for example, points to 2050 as the most likely date for the onset of widespread civilisational collapse. The central idea would be that, due to a sharp worsening of the current climate situation, and the possible transformation by the middle of this century of a large part of our planet into uninhabitable, a point of no return would then be reached in which the fracture and collapse of nation states and the world order would be inevitable . At the same time, he states that the needed goals to avert this catastrophe which will lay the foundations for a transition to “clean energy”, and a more just society, would still be perfectly achievable. Specifically, Chomsky says that this would only require an investment of around 2-3% of world GDP, the latter within the framework of a plan of “environmental reforms” described in the so-called “Green New Deal” of which he is one of its main advocates.

Let’s reflect for a moment on the above. On the one hand, Chomsky accepts the possibility of a planetary civilisational collapse in the course of this century. On the other hand, he reduces the solution to this threat to nothing more than the application of a “green tax”. Literally the greatest historical, economic, social, cultural and even geological challenge that the human species and civilisation has faced since its origins reduced, roughly speaking, to a problem of “international financial fundraising” consisting of allocating approximately 3% of world GDP to the promotion of “clean energies”. Let’s think about this again. A danger that, as Chomsky puts it, would be even greater than the Second World War and could turn the Earth into a kind of uninhabitable rock, should be solved either by “international tax collection” or by a plan of limited “eco-reforms” of the capitalist economic model (known as the “Green New Deal”).

But how is it possible that Chomsky, one of the leading intellectuals of the 20th century, is able to make this “interpretive leap” between accepting the possibility of the “end of all organised human society” within this century and reducing the solution to that threat to what would appear to be no more than a (rather timid) cosmetic restructuring of international capitalist finance? Who knows! What is certain, however, is that Chomsky’s response to the climate threat lags far behind not only those advocated by the ecosocialist camp and even traditional Marxism to deal with the latter, based on posing the link between the problem of the root causes of the ecological crisis and the need for a politics that defends the abolition of private ownership of the means of production as a necessary step in confronting it. Moreover, Chomsky’s treatment of the ecological crisis seems to be inferior to that which characterises all those theoretical tendencies which, such as the theory of degrowth or a series of collapsist currents, advocate the imposition of drastic plans of economic degrowth and a substantial decrease in industrial activity and global consumption levels. The latter by promoting a process of “eco-social transition” which would not be reduced to a mere change in the energy matrix and the promotion of renewable energies, but would imply, on the contrary, the transition from one type of civilisation (modern and industrial) to another, better able to adapt to the new planetary scenarios that the ecological crisis, energy decline and global resource scarcity will bring with them.

But reducing the solution of the climate catastrophe to the need for a “green tax” on the capitalist market economy is not the only error in Chomsky’s response. In my view, the main problem of the arguments he uses to defend the possibility of a successful “energy transition” from fossil fuels to so-called “clean energy” would be that they are built on mud. First, because it is false to say that so-called “clean energies” are indeed “clean” if we consider the kind of resources and technological efforts required in the implementation of the energy systems based on them. Solar or wind energy, for example, depend not only on huge amounts of raw materials associated for their construction with high polluting extractive processes (e.g., the large quantities of steel required for the construction of wind turbines is just one illustration of this), but also on the use of extensive volumes of coal, natural gas or even oil. The construction of a single solar panel requires, for instance, enormous quantities of coal. Another striking example can be seen in the dependence of hydrogen plants (specially the “grey” or “blue” types) on vast quantities of natural gas for their operations. All this without it ever being clear that the reduction in the use of fossil fuels that should result from the implementation of these “clean” technologies will be capable of effectively offsetting a possible exponential increase in its “ecological footprint” in the context of a supposedly successful energy transition .

Secondly, it is false to assume that an energy matrix based on renewable energies could satisfy the energy contribution of fossil fuels to the world economy in the short or medium term, at least, if a replication of current (ecologically unviable) patterns of economic growth is sought. Examples of this include the virtual inability of so-called “green hydrogen” power plants to become profitable systems in the long term, as well as the enormous challenges that some power sources such as solar or wind energy (highly unstable) would face in meeting sustained levels of energy demand over time. All this without even considering the significant maintenance costs of renewable energy systems, which are also associated (as said) with the use of highly polluting raw materials and a series of supplies whose manufacture also depend on the use of fossil fuels .

But the argumentative problems in Chomsky’s response are not limited to the above. More importantly is that the danger of the climate crisis and the possibility of a planetary collapse can no longer be confined to a purely financial issue (solvable by a hypothetical allocation of 3% of world GDP) or a strictly technical-engineering challenge (solvable by the advancement of a successful energy transition). This is because the magnitude of this problem has gone beyond the area of competence of economic and technological systems, and has moved to the sphere of the geological and biophysical relations of the planet itself, calling the very techno-scientific (and economic-financial) capacities of contemporary civilisation into question. In other words, the problem represented by the current levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, or those related to the unprecedented advances in marine acidification, Arctic melting, or permafrost decomposition rates, would today constitute challenges whose solution would be largely beyond any of our scientific developments and technological capabilities. Let’s just say that current atmospheric carbon dioxide levels (already close to 420 ppm) have not been seen for millions of years on Earth. On other occasions I have defined this situation as the development of a growing “terminal technological insufficiency” of our civilisation to face the challenges of the present planetary crisis .

In the case of current atmospheric CO2 concentrations, for example, there are not and will not be for a long time (possibly many decades or centuries), any kind of technology capable of achieving a substantial decrease of those concentrations. This at least not before such concentrations continue to skyrocket to levels that could soon guarantee that a large part of our planet will become completely uninhabitable in the short to medium term. In the case of CO2 capture facilities, for instance, they have not yet been able to remove even a small (insignificant) fraction of the more than 40 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide emitted each year by industrial society . Something similar would be the situation of other ecological problems such as the aforementioned increase in marine acidification levels, the rise in ocean levels or even the increasingly unmanageable proliferation of space debris and the consequent danger it represents for the (immediate) maintenance of contemporary telecommunication systems. In other words, again, increasing threatening problems for which humanity has no effective technologies to cope, at least not over the few remaining decades before these problems reach proportions that will soon call into question our very survival as a species.

Unsolvable problems, as unsolvable as those that would confront anyone seeking to “restore” a clay pot or a glass bottle to its original state after it has been shattered into a thousand fragments by smashing it against a concrete wall! To restore a glass of the finest crystal after it has been smashed to pieces? Not even with the investment of ten, a hundred world GDPs would it be possible! This is what we have done with the world, the most beautiful of the planetary crystals of our solar system, blown into a thousand pieces by ecocidal industrialism! To restore? To resolve? Bollocks! We have already destroyed it all! We have already finished it all! And no “financial investment” or “technological solution” can prevent what is coming: death! To die then! To die… and to fight to preserve what can be preserved! To die and to hope for the worst, to conquer socialism however we can, on whatever planet we have, and to take the future out of the hands of the devil himself if necessary! That is the task of socialist revolution in the 21st century! That is the duty of Marxist revolutionaries in the new epoch of darkness that is rising before us! That is the mission of Marxism-Collapsist!

Max Wilbert:

Throughout history, all civilizations undermine their own ecological foundations, face disease, war, political instability, and the breakdown of basic supply chains, and eventually collapse.

Modern technology and scientific knowledge does not make us immune from this pattern. On the contrary, as our global civilization has harnessed more energy, expanded, and grown a larger population than ever before in history, the fall is certain to be correspondingly worse. What goes up must come down. This is a law of nature. The only question is, when?

Professor Chomsky’s argument that collapse of civilization can be averted at a relatively minor cost by diverting 2-3% of global GDP to transition to renewable energy and fund a *Global Green New Deal* does not contend with the physical constraints civilization faces today. The global energy system, which powers the entire economy, is the largest machine in existence and was built over more than a century during a period of abundant fossil fuels and easy-to-access minerals and raw materials. It was powered by the *last remnants of ancient sunlight*, fossil fuels condensed into an extremely dense form of energy that is fungible and easily transportable.

That era is over. Accessible reserves of minerals, oil, and gas are gone, and we are long since into the era of extreme energy extraction (fracking, deepwater drilling, arctic drilling, tar sands, etc.). Simply replacing fossil fuels with solar and wind energy and phasing out all liquid and solid fuel (which still makes up roughly 80% of energy use) in favor of electrification of transportation, heating, etc. is not a simple task in an era of declining energy availability, increasing costs, extreme weather, political and financial instability, and resource scarcity. And these so-called “renewable” technologies still have major environmental impacts (for example, see solar impacts on desert tortoise, wind energy impacts on bat populations, and lithium mining impacts on sage-grouse), even if they do reduce carbon emissions—which is not yet proven outside of models.

In practice, renewable energy technologies seem to be largely serving as a profitable investment for the wealthy, a way to funnel public money into private hands, and a distraction from the scale of the ecological problems we face (of which global warming is far from the worst) and the scale of solutions which are needed. This is, as Miguel Fuentes points out, a rather timid cosmetic restructuring of the dominant political and economic order.

In our book *Bright Green Lies: How the Environmental Movement Lost Its Way and What We Can Do About It*, my co-authors and I call this “solving for the wrong variable.” We write: “Our way of life [industrial modernity] doesn’t need to be saved. The planet needs to be saved from our way of life… we are not saving civilization; we are trying to save the world.” Scientists like Tim Garrett at the University of Utah model civilization as a “heat engine,” a simple thermodynamic model that will consume energy and materials until it can no longer do so, then collapse. Joseph Tainter, the scholar of collapse, writes that “in the evolution of a society, continued investment in complexity as a problem-solving strategy yields a declining marginal return.” This is our reality.

Whether sanity prevails and we succeed in building a new politics and new societies organized around rapidly scaling down the human enterprise to sustainable levels, or we continue down the business-as-usual path we are on, the future looks either grim or far more dire. Global warming will continue to worsen for decades even if, by some miracle, we are able to dismantle the fossil fuel industry and restore the ecology of this planet. The 6th mass extinction event and ecological collapse aren’t a distant future. We are in the depths of these events, and they’ve been getting worse for centuries. The question is not “can we avoid catastrophe?” It’s too late for that. The question is, “how much of the world will be destroyed?” Will elephants survive? Coral reefs? Tigers? The Amazon Rainforest? Will humans? What will we leave behind?

I want to leave behind as much biodiversity and ecological integrity as possible. Human extinction seems unlikely, at least in coming decades, unless runaway global warming accelerates faster than predicted. “Unlikely” is not “impossible,” but there are 8 billion of us, and we are profoundly adaptable. I am far less worried about human extinction than about the extinction of countless other species—100 per day. I am far more worried about the collapse of insect populations or phytoplankton populations (which provide 40% of all oxygen on the planet and are the base of the oceanic food web). The fabric of life itself is fraying, and we are condemning unborn human generations to a hellish future and countless non-humans to the extinction. Extinction will come for humans, at some point. But at this point, I am not concerned for our species, but rather for the lives of my nephews and their children, and the salmon on the brink of extermination, and the last remaining old-growth forests.

Guy McPherson:

There is no escape from the mass extinction event underway. Only human arrogance could suggest otherwise. Our situation is definitely terminal. I cannot imagine that there will be a habitat for Homo sapiens beyond a few years in the future. Soon after we lose our habitat, all individuals of our species will die out. Global warming has already passed two degrees Celsius above the 1750 baseline, as noted by the renowned Professor Andrew Glikson in his October 2020 book “The Event Horizon”. He wrote on page 31 of that book: “During the Anthropocene, greenhouse gas forcing increased by more than 2.0 W/m2, equivalent to more than > 2°C above pre-industrial temperatures, which is an abrupt (climate change) event taking place over a period not much longer than a generation”.

So yes. We have definitely passed the point of no return in the climate crisis. Even the incredibly conservative Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has already admitted the irreversibility of climate change in its 24 September 2019 “Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate”. A quick look around the globe will also reveal unprecedented events such as forest fires, floods and mega-droughts. The ongoing pandemic is just one of many events that are beginning to overwhelm human systems and our ability to respond positively.

All species are going extinct, including more than half a dozen species of the genus Homo that have already disappeared. According to the scientific paper by Quintero and Wiens published in Ecology Letters on 26 June 2013, the projected rate of environmental change is 10.000 times faster than vertebrates can adapt to. Mammals also cannot keep up with these levels of change, as Davis and colleagues’ paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on 30 October 2018 points out. The fact that our species is a vertebrate mammal suggests that we will join more than 99% of the species that have existed on Earth that have already gone extinct. The only question in doubt is when. In fact, human extinction could have been triggered several years ago when the Earth’s average global temperature exceeded 1.5 degrees Celsius above the 1750 baseline. According to a comprehensive overview of this situation published by the European Strategy and Policy Analysis System in April 2019, a “1.5 degree increase is the maximum the planet can tolerate; (…) in a worst-case scenario, [such a temperature increase above the 1750 baseline will result in] the extinction of humanity altogether”.

All species need habitat to survive. As Hall and colleagues reported in the Spring 1997 issue of the Wildlife Society Bulletin: “We therefore define habitat ‘as the resources and conditions present in an area that produce occupancy, including survival and reproduction, of a given organism. Habitat is organism-specific; it relates the presence of a species, population or individual (…) to the physical and biological characteristics of an area. Habitat implies more than vegetation or the structure of that vegetation; it is the sum of the specific resources needed by organisms. Whenever an organism is provided with resources that allow it to survive, that is its habitat’”. Even tardigrades are not immune to extinction. Rather, they are sensitive to high temperatures, as reported in the 9 January 2020 issue of Scientific Reports. Ricardo Cardoso Neves and collaborators point out there that all life on Earth is threatened with extinction with an increase of 5-6 degrees Celsius in the global average temperature. As Strona and Corey state in another article in Scientific Reports (November 13, 2018) raising the issue of co-extinctions as a determinant of the loss of all life on Earth: “In a simplified view, the idea of co-extinction boils down to the obvious conclusion that a consumer cannot survive without its resources”.

From the incredibly conservative Wikipedia entry entitled “Climate change” comes this supporting information: “Climate change includes both human-induced global warming and its large-scale impacts on weather patterns. There have been previous periods of climate change, but the current changes are more rapid than any known event in Earth’s history.” The Wikipedia entry further cites the 8 August 2019 report “Climate Change and Soils”, published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The IPCC is among the most conservative scientific bodies in history. Yet it concluded in 2019 that the Earth is in the midst of the most rapid environmental change seen in planetary history, citing scientific literature that concludes: “These rates of human-driven global change far exceed the rates of change driven by geophysical or biospheric forces that have altered the trajectory of the Earth System in the past (Summerhayes 2015; Foster et al. 2017); nor do even abrupt geophysical events approach current rates of human-driven change”.

The Wikipedia entry also points out the consequences of the kind of abrupt climate change currently underway, including desert expansion, heat waves and wildfires becoming increasingly common, melting permafrost, glacier retreat, loss of sea ice, increased intensity of storms and other extreme environmental events, along with widespread species extinctions. Another relevant issue is the fact that the World Health Organisation has already defined climate change as the greatest threat to global health in the 21st century. The Wikipedia entry continues: “Under the 2015 Paris Agreement, nations collectively agreed to keep warming ‘well below 2.0 degrees C (3.6 degrees F) through mitigation efforts’”. But Professor Andrew Glikson already pointed out as we said in his aforementioned book The Event Horizon that the 2 degrees C mark is already behind us. Furthermore, as we already indicated, the IPCC also admitted the irreversibility of climate change in its “Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate”. Therefore, 2019 was an exceptional year for the IPCC, as it concluded that climate change is abrupt and irreversible.

How conservative is the IPCC? Even the conservative and renowned journal BioScience includes an article in its March 2019 issue entitled “Statistical language supports conservatism in climate change assessments”. The paper by Herrando-Perez and colleagues includes this information: “We find that the tone of the IPCC’s probabilistic language is remarkably conservative (…) emanating from the IPCC’s own recommendations, the complexity of climate research and exposure to politically motivated debates. Harnessing the communication of uncertainty with an overwhelming scientific consensus on anthropogenic climate change should be one element of a broader reform, whereby the creation of an IPCC outreach working group could improve the transmission of climate science to the panel’s audiences”. Contrary to the conclusion of Herrando-Perez and colleagues, I cannot imagine that the IPCC is really interested in conveying accurate climate science to its audiences. After all, as Professor Michael Oppenheimer noted in 2007, the US government during the Reagan administration “saw the creation of the IPCC as a way to prevent the activism stimulated by my colleagues and me from controlling the political agenda”.

Question 2:

Marxism and Collapse: Have the human species become a plague for the planet? If so, how can we still conciliate the survival of life on Earth with the promotion of traditional modern values associated with the defence of human and social rights (which require the use of vast amounts of planetary resources) in a context of a potential increase of world’s population that could reach over twelve billion people this century? The latter in a context in which (according to several studies) the maximum number of humans that Earth could have sustained without a catastrophic alteration of ecosystems should have never exceeded the billion. Can the modern concept of liberal (or even socialist) democracy and its supposedly related principles of individual, identity, gender, or cultural freedom survive our apparent terminal geological situation, or it will be necessary to find new models of social organization, for example, in those present in several indigenous or native societies? Can the rights of survival of living species on Earth, human rights, and the concept of modern individual freedom be harmoniously conciliated in the context of an impending global ecosocial disaster?

Noam Chomsky:

Let’s begin with population growth. There is a humane and feasible method to constrain that: education of women. That has a major effect on fertility in both rich regions and poor, and should be expedited anyway. The effects are quite substantial leading to sharp population decline by now in parts of the developed world. The point generalizes. Measures to fend off “global ecosocial disaster” can and should proceed in parallel with social and institutional change to promote values of justice, freedom, mutual aid, collective responsibility, democratic control of institutions, concern for other species, harmony with nature –values that are commonly upheld by indigenous societies and that have deep roots in popular struggles in what are called the “developed societies” –where, unfortunately, material and moral development are all too often uncorrelated.

Miguel Fuentes:

Chomsky’s allusions to the promotion of women’s education and the social values of justice, freedom, mutual aid, and harmony with nature, as “moral values” disconnected from a broader critique of the industrial system, capitalism, and the class society within which threats such as global warming have been generated and aggravated, become mere phrases of good intentions. On the contrary, the realization of these principles must be thought within a context of a large-scale world social transformation. The latter if those principles are to be effective in combatting the challenges facing humanity today and the kind of civilisational crisis that is beginning to unfold as a product of the multiple eco-social (ecological, energy and resource) crises that are advancing globally. In other words, a process of historical transformation that can envisage the abolition of the current ecocidal industrial economic system, and its replacement by one in which production, exchange and distribution can be planned in accordance with social needs.

But even a traditional socialist approach to these problems, such as the one above, also falls short of accounting for the kind of planetary threats we face. Let’s put it this way, the discussion around the ecological crisis and the rest of the existential dangers hanging over the fate of our civilisation today really only begins, not ends, by giving it a proper Marxist contextualisation. One of the underlying reasons for this is that the traditional socialist project itself, in all its variants (including its more recent ecosocialist versions), would also already be completely insufficient to respond to the dangers we are facing as a species. That is, the kind of dangers and interpretative problems that none of the Marxists theoreticians of social revolution over the last centuries had ever imagined possible, from Marx and Engels to some of the present-day exponents of ecosocialism such as John Bellamy Foster or Michael Lowy .

One of these new types of problems that revolutionary theories are facing today is that of the current uncontrolled demographic growth rates of humanity. A problem that would already confer on us, amongst other things, the condition of one of the worst biological (or, in our case, “biosocial”) plagues existing to this day. This if we consider the absolutely devastating role that our species has been exerting on the biosphere in the last centuries. A plague that would be even comparable in its destructive power to that represented by the cyanobacteria that triggered the first mass extinction event on Earth some 2.4 billion years ago, although in our case at an even more accelerated and “efficient” pace than the latter. Is this statement too brutal? Maybe, from a purely humanist point of view, alien to the kind of problems we face today, but not from an eminently scientific perspective. Or can there be any doubt about our condition as a “planetary plague” for any ecologist studying the current patterns of behaviour, resource consumption and habitat destruction associated with our species? Too brutal a statement? Tell it to the more than 10.000 natural species that become extinct every year as a result of the role of a single species on the planet: ours! Tell it to the billions of animals killed in the great fires of Australia or the Amazon a few years ago! Tell it to the polar bears, koalas, pikas, tigers, lions, elephants, who succumb every year as a product of what we have done to the Earth! Very well, we are then a “plague”, although this term would only serve to classify us as a “biological species”, being therefore too “limited” a definition and lacking any social and historical perspective. Right?

Not really. The fact that we possess social and cultural systems that differentiate us from other complex mammals does not mean that our current status as a “plague of the world” should be confined to the biological realm alone. On the contrary, this just means that this status could also have a certain correlation in the social and cultural dimension; that is, in the sphere of the social and cultural systems particular to modern society. To put it in another way, even though our current condition of “plague of the world” has been acquired by our species within the framework of a specific type of society, mode of production and framework of particular historical relations, characteristic of industrial modernity, this does not mean that this condition should be understood as a merely historical product. That is, excluding its biological and ecological dimension. In fact, beyond the differentiated position and role of the various social sectors that make up the productive structure and the socio-economic systems of the industrial society (for example, the exploiting and exploited social classes), it is indeed humanity as a whole: rich and poor, entrepreneurs and workers, men and women, who share (all of us) the same responsibility as a species (although admittedly in a differentiated way) for the current planetary disaster. An example of the above. Mostly everything produced today by the big multinationals, down to the last grain of rice or the last piece of plastic, is consumed by someone, whether in Paris, London, Chisinau or La Paz. And we should also remember that even biological plagues (such as locusts) may have different consumption patterns at the level of their populations, with certain sectors being able to consume more and others consuming less. However, just because one sector of a given biological plague consumes less (or even much less), this sector should not necessarily be considered as not belonging to that plague in question.

Another similar example: it is often claimed in Marxist circles (sometimes the numbers vary according to each study) that 20% of humanity consumes 80% of the planetary resources. This means that approximately 1.600.000.000.000 people (assuming a total population of 8 billion) would be the consumers of that 80% of planetary resources; that is, a number roughly equivalent to three times the current European population. In other words, what this sentence really tells us is that a much larger segment of the world’s population than the capitalist elites (or their political servants) would also bear a direct, even grotesque, responsibility for the unsustainable consumption patterns that have been aggravating the current planetary crisis. Or, to put it in more “Marxist” terms, that a large percentage (or even the totality) of the working classes and popular sectors in Europe, the United States, and a significant part of those in Latin America and other regions of the so-called “developing countries”, would also be “directly complicit”, at least in regards of the reproduction of the current ecocidal modern urban lifestyle, in the destruction of our planet.

But let us extend the discussion to the remaining 80% of humanity; that is, to the approximately 6.400.000.000.000 people who consume 20% of the planetary resources used in a year. To begin with, let us say that 20% of global resources is not a negligible percentage, representing in fact a fifth of them and whose production would be associated with substantial and sustained levels of environmental destruction. The latter in the context of an ever-growing world population that possibly should never have exceeded one billion inhabitants, so that we would have been in a position today to stop or slow down the disastrous impact we are having on ecosystems. Let us not forget that the number of people included in this 80% of the world’s population is more than four times higher than the entire human population at the beginning of the 20th century, which means that the number of basic resources necessary for the survival of this sector is an inevitable pressure on the earth’s natural systems, even if consumption levels are kept to a minimum.

In short, there is therefore no doubt that humanity has indeed become one of the worst planetary plagues in the history of terrestrial life, constituting this a (fundamental) problem in itself for contemporary revolutionary thought and, more generally, for the human and social sciences as a whole. In other words, a problem that today would not be solved by a mere change in the mode of production, the class structure, or the socio-political system, but would be associated with the very “genetics” of the development of industrial society. That is to say, a society based on a particularly destructive (voracious) form of human-nature relationships, which would be at the same time the “structural basis” of all possible and conceivable models of it (capitalists, socialists or any other type). Whether in the framework of a neo-liberal market economy or a socialist and/or collectivist planned economy, it is the industrial system and modern mass society in all its variants, whether capitalist or socialist, its mega-cities, its productive levels, its consumption patterns and lifestyles, its “anthropocentric spirit”, structurally associated with certain demographic patterns in which the Earth is conceived as a mere space for human consumption and reproduction… that is the main problem.

Is it possible to reconcile current levels of overpopulation with the survival requirements of our species? No. We have become a planetary plague and will remain a planetary plague until such time as, by hook or by crook (almost certainly by crook) our numbers are substantially reduced and remain at the minimum possible levels, for at least a few centuries or millennia. Is it possible to solve the problem of overpopulation and at the same time defend the legitimacy of traditional modern values associated with the promotion of human and social rights, at least as these values have been understood in recent centuries? No. Modernity has failed. Modernity is dead. We are going to have to rethink every single one of our values, including the most basic ones, all of them. We are going to have to rethink who we are, where we are going and where we come from. The existence of almost 8 billion people on our planet today, and moreover the likely increase of this number to one that reaches 10 or even 12 billion is not only incompatible with the realisation of the very ideals and values of modern democracy in all its variants (capitalists or socialists), but also with the very survival of our species as a whole and, possibly, of all complex life on Earth. This simply because there will be nowhere near enough resources to ensure the realization of these values (or even our own subsistence) in such a demographic context (there simply won’t be enough food and water). Our situation is terminal. Modernity is dead. Democracy is dead. Socialism is dead. And if we want these concepts -democracy or socialism- to really have any value in the face of the approaching catastrophe, then we will have to rethink them a little more humbly than we have done so far.

Modern civilisation has borne some of the best fruits of humanity’s social development, but also some of the worst. We are in some ways like the younger brother of a large family whose early successes made him conceited, stupid and who, thinking of himself as “master of the world”, began to lose everything. We are that young man. We should therefore shut up, put our ideologies (capitalists and socialists) in our pockets, and start learning a little more from our more modest, slower and more balanced “big brothers”; for example, each of the traditional or indigenous societies which have been able to ensure their subsistence for centuries and in some cases even millennia. The latter while industrial society would not even have completed three centuries before endangering its own existence and that of all other cultures on the planet. In a few words, start learning from all those traditional societies that have subsisted in the context of the development of social systems that are often much more respectful of ecological and ecosystemic balances. Those “ecosocial balances” which are, in the end, in the long view of the evolution of species, the real basis for the development of any society… because without species (be they animal or plant), any human culture is impossible. Scientific and technological progress? Excellent idea! But perhaps we could take the long route, think things through a bit more, and achieve the same as we have achieved today in two centuries, but perhaps taking a bit longer, say ten, twenty or even a hundred centuries? Who’s in a hurry? Let us learn from the tortoise which, perhaps because it is slow, has survived on Earth for more than 220 million years, until we (who as Homo sapiens are no more than 250.000 years old) came along and endangered it.

Max Wilbert:

Human population is a hockey-stick graph that corresponds almost exactly with rising energy use. Most of the nitrogen in our diet comes from fossil fuel-based fertilizers. Norman Borlaug, the plant breeder who won the Nobel Peace Prize for his work on the Green Revolution, said in his acceptance speech that “we are dealing with two opposing forces, the scientific power of food production and the biologic power of human reproduction… There can be no permanent progress in the battle against hunger until the agencies that fight for increased food production and those that fight for population control unite in a common effort.”

Ideally, this situation could be dealt with humanely by education and making family planning and women’s health services available. The best example of this actually comes from Iran, where under a religious theocracy in the wake of the Iran-Iraq war, birth rates were reduced from around 7 children per woman to less than replacement in little more than a decade (the policy was since reversed, and Iran’s land and water is paying the price). Technically, it’s quite easy to solve overpopulation humanely; reduce birth rates to less than replacement levels, then wait. Politically, it’s much harder. As we’ve seen with the recent fall of abortion rights in the US, the political battle for control of women’s reproduction is alive and well, and basic ecology is anathema to many political leaders and populations.

Unless we take action to reduce our population willingly, it will happen unwillingly as the planet’s ecology fails to be able to support us. That will be harsh. Any species that exceeds the carrying capacity of the environment it lives in will experience a population crash, usually due to starvation, disease, and predation. That’s our choice. Either we make the right decisions, or we pay the price.

The difference between our situation today and the Indus Valley civilization or the Roman Empire is that today civilization is globalized. The collapse of global industrial civilization, as I wrote above, is coming. I don’t believe it can be stopped at this point; in fact, I believe it is already in progress. But collapse is also not simply an overnight chaotic breakdown of all social order. We can define collapse as a rapid simplification of a complex society characterized by breakdown of political and social institutions, a return to localized, low energy ways of life, and usually a significant reduction in population (which is a nice way of saying, a lot of people die).

Collapse should be looked at as having good and bad elements. Good elements, from my perspective, include reducing consumption and energy use, localizing our lives, and having certain destructive institutions (for example, the fossil fuel industry) fade away. Bad elements might include breakdown of basic safety and rising violence, mass starvation, disease, and, for example, the destruction of local forests for firewood if electricity is no longer available for heating. Some aspects of collapse have elements of both. For example, the collapse of industrial agriculture would be incredibly beneficial for the planet but would lead to mass human die offs.

If collapse is coming regardless of what we want, it’s our moral and ecological responsibility to make the best of the situation by assisting and accelerating the positive aspects of collapse (for example, by working to reduce consumption and dismantle oil infrastructure) and help prevent or mitigate the negative aspects (for example, by working to reduce population growth and build localized sustainable food systems).

As I write this, I am looking into a meadow between 80-year-old oak trees. A deer and her fawn are walking through the grass. Birds are singing in the trees. A passenger jet roars overhead, and the hum of traffic floats over the hills. There is a fundamental contradiction between industrial civilization and ecology, and the organic tensions created by this contradiction are rising. These are dire and revolutionary times, and it is our responsibility to navigate them.

Guy McPherson:

As ecologists have been pointing out for decades, environmental impacts are the result of human population size and human consumption levels. The Earth can support many more hunter-gatherers than capitalists seeking more material possessions. Unfortunately, we are stuck with the latter rather than the former. Ecologists and environmentalists have been proposing changes in human behaviour since at least the early 20th century. These recommendations have fallen on deaf ears. However, even if it is possible to achieve substantial changes in human behaviour, and if they result in an effective slowing down or stopping of industrial activity, it is questionable whether this is a useful means of ensuring our continued survival. One reason for this lies in the knowledge of what the effect of “aerosol masking” could mean for the climate crisis.

The “climate masking” effect of aerosols has been discussed in the scientific literature since at least 1929, and consists of the following: at the same time as industrial activity produces greenhouse gases that trap part of the heat resulting from sunlight reaching the Earth, it also produces small particles that prevent this sunlight from even touching the surface of the planet. These particles, called “aerosols”, thus act as a kind of umbrella that prevents some of the sunlight from reaching the earth’s surface (hence this phenomenon has also been referred to as “global dimming”) . In other words, these particles (aerosols) prevent part of the sun’s rays from penetrating the atmosphere and thus inhibit further global warming. This means, then, that the current levels of global warming would in fact be much lower than those that should be associated with the volumes of greenhouse gases present in the atmosphere today (hence the designation of this phenomenon as “climate masking”). To put it in a simpler way, the global warming situation today would actually be far more serious than is indicated not only by the very high current global temperatures, but also by the (already catastrophic) projections of rising global temperatures over the coming decades. This is especially important if we consider the (overly optimistic) possibility of a future reduction in the amount of aerosols in the atmosphere as a result of a potential decrease in greenhouse gas emissions over the next few years, which should paradoxically lead, therefore, to a dramatic increase in global temperatures.

Global temperatures should then not only be much higher than they are today, but the expected rise in global temperatures will necessarily be more intense than most climate models suggest. According to the father of climate science, James Hansen, it takes about five days for aerosols to fall from the atmosphere to the surface. More than two dozen peer-reviewed papers have been published on this subject and the latest of these indicates that the Earth would warm by an additional 55% if the “masking” effect of aerosols were lost, which should happen, as we said, as a result of a marked decrease or modification of industrial activity leading to a considerable reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. This study suggests that this could potentially lead to an additional (sudden) increase in the earth’s surface temperature by about 133% at the continental level. This article was published in the prestigious journal Nature Communications on 15 June 2021. In conclusion, the loss or substantial decrease of aerosols in the atmosphere could therefore lead to a potential increase of more than 3 degrees Celsius of global warming above the 1750 baseline very quickly. I find it very difficult to imagine many natural species (including our own) being able to withstand this rapid pace of environmental change.

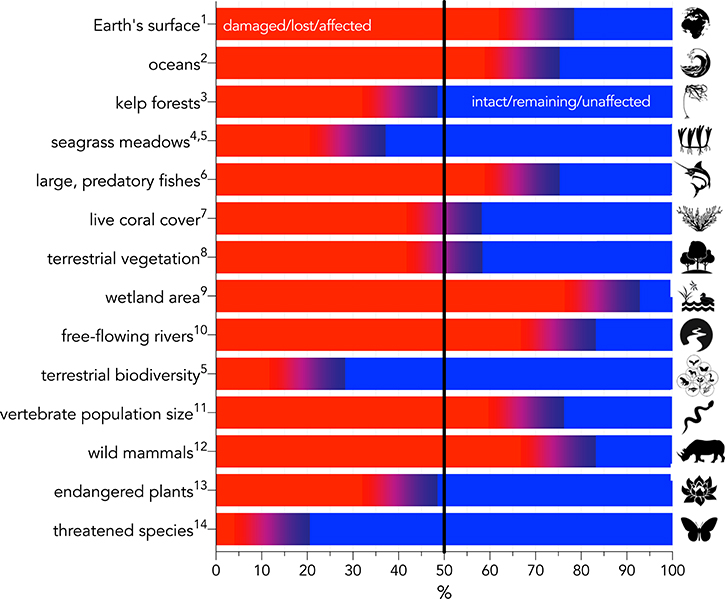

In reality, a mass extinction event has been underway since at least 1992. This was reported by Harvard professor Edward O. Wilson, the so-called “father of biodiversity”, in his 1992 and 2002 books The Diversity of Life and The Future of Life, respectively. The United Nations Environment Programme also reported in August 2010 that every day we are leading to the extinction of 150 to 200 species. This would thus be at least the eighth mass extinction event on Earth. The scientific literature finally acknowledged the ongoing mass extinction event on 2 March 2011 in Nature. Further research along these lines was published on 19 June 2015 in Science Advances by conservation biologist Gerardo Ceballos and colleagues entitled “Accelerated human-induced losses of modern species: entering the sixth mass extinction”. Coinciding with the publication of this article, lead author Ceballos stated that “life would take many millions of years to recover and that our species would probably soon disappear”. This conclusion is supported by subsequent work indicating that terrestrial life did not recover from previous mass extinction events for millions of years. It is true, however, that indigenous perspectives can help us understand ongoing events. However, I am convinced that rationalism is key to a positive response to these events.

Noam Chomsky is an American linguist, philosopher, cognitive scientist, historian, social critic, and political activist. He adheres to the ideas of libertarian socialism and anarcho-syndicalism. He advocates a New Green Deal policy as one of the ways of dealing with the ecological crisis.

Miguel Fuentes is a Chilean social researcher in the fields of history, archaeology, and social sciences. International coordinator of the platform Marxism and Collapse and exponent of the new Marxist-Collapsist ideology. He proposes the need for a strategic-programmatic updating of revolutionary Marxism in the face of the new challenges of the Anthropocene and the VI mass extinction.

Max Wilbert is an organizer, writer, and wilderness guide. He has been part of grassroots political work for 20 years. He is the co-author of Bright Green Lies: How The Environmental Movement Lost Its Way and What We Can Do About It, which was released in 2021. He is the co-founder of Protect Thacker Pass and part of Deep Green Resistance.

Guy McPherson is an American scientist, professor emeritus of natural resources, ecology, and evolutionary biology. He adheres to anarchism and argues the inevitability of human extinction and the need to address it from a perspective that emphasises acceptance, the pursuit of love and the value of excellence.

The final version of this document has been edited by Dutch archaeologist Sven Ransijn.

Notes

The debate between Michael Lowy, Miguel Fuentes, and Antonio Turiel (which also included critical comments by Spanish Marxist ecologist Jaime Vindel, Argentinean left-wing leader Jorge Altamira and Chilean journalist Paul Walder) can be reviewed in full in the debate section of the Marxism and Collapse website at the following link: www.marxismoycolapso.com/debates.

by DGR News Service | May 1, 2022 | ACTION

Editor’s note: The ability to work with others who we may disagree is fundamental to organizing in a socially fractured, multi-polar world. But doing so is difficult, distasteful, and increasingly rare in our filter-bubble modern experience, where people we disagree with are purged in service of the creation of ideological echo chambers. Today’s essay speaks to the necessity and challenges of such coalition-building.

Before we begin, we would like to share with you some actionable advice for coalitions. Building principled alliances depends on a series of steps that must be undertaken with intelligence and great care:

1. Movement Building. You cannot build an alliance as an individual. Alliances are built between organizations. We will assume here you have already done the work of identifying the core issues you are trying to address, articulating your core values, and bringing together a team/organization to take action.

2. Objectives. Alliances depend on you clearly understanding what you are trying to achieve. Determine your objectives. Ensure they are SMART and practical. You may also wish to sequence objectives along a timeline towards your broader strategic goals.

3. Understand the Political Context. Conduct a spectrum of allies exercise. Identify communities, individuals, and organizations who are involved in the situation or may be swayed to take part, and how sympathetic they are to your perspective.

4. Determine Potential Allies. Determine which organizations you will focus on for alliance building. Usually, this is not the “easy allies” who will work with you regardless of what you do. Instead, pivotal allies are often found among the ranks of those who are ambivalent or opposed to your organization in some way. Focus on key individuals, usually either formal or informal leaders. Research these people and identify areas of overlap, shared values, and how to effectively communicate with them.

5. Build Relationships and Negotiate. Talk with potential allies. Begin to build a relationship. Do not gloss over disagreements, but focus on areas of mutual benefit and overlapping values. Propose specific ways work together towards shared goals. Keep in mind that collaboration can fall along a spectrum from public to private, that political considerations may prevent certain approaches, and that building trust takes time.

By Jaskiran Dhillon / ROAR Magazine

They called it the heat dome.

The hottest temperatures ever recorded in the US Pacific Northwest and far southwest Canada appeared in the summer of 2021 with the force of an invisible, slow-motion siege. Meteorologists tracking the silently rising tidal wave of heat broadcasted maps painted in shades of crimson, alerting a sleeping public to a summer gone blazing red. The headlines said it all: “This Summer Could Change Our Understanding of Extreme Heat,” “Sweltering Temperatures Expected Across U.S. Due to Heat Dome,” and “Western Canada Burns and Deaths Mount After World’s Most Extreme Heat Wave in Modern History.”

Created through a high pressure system that causes the atmosphere to trap very warm air — and precipitated, in part, through heat emerging from increasingly warming oceans — a heat dome produces extreme temperatures at ground level that can persist for days or even weeks. In British Columbia, Canada, thermometers were registering the air at an alarming 49.6 degrees Celsius, with similar highs in the states of Washington and Oregon, immediately south of the border, exposing US and Canadian residents to the type of extreme weather events countries in the Global South have been experiencing for years. But this kind of heat does not just live in the air that we breathe — it envelopes everything it touches, leaving a trail of death, destruction, and urgent questions about the future.

For climate scientists who have been studying the intensification of heat wavesover the last decade, the results of the heat dome were predictably devastating. The British Columbia Coroners Service identified 569 heat related deaths between June 20 to July 29, and 445 of them occurred during the heat dome. A human body exposed to severe and relentless heat is a body under duress, a body working overtime: when subjected to an elevation in air temperatures, our bodies draw additional blood to the skin to dissipate heat — a natural cooling system designed to maintain optimal body temperature. This process becomes more strained when the temperature continues to rise, without the reprieve of cooling; oxygen consumption and metabolism both escalate, leading to a faster heart rate and rapid breathing. Above 42 degrees Celsius, enzyme and energy production fail and the body is in danger of developing a systemic inflammatory response. Eventually, multi-system failure can occur.

And humans were not the only beings impacted. According to an article published in The Atlantic in July 2021, billions of mussels, clams, oysters, barnacles, sea stars and other intertidal species also died. A number of land-based species also fared badly, buckling in the sweltering and suffocating air, creating a dystopic tale of “desperate and dying wildlife.”

To put it plainly: the physiological stress of extreme heat on living organisms is life threatening — in particular for human beings: baking to death is a real possibility if you do not have access to cooling systems, or if you are one of the millions of people who live in parts of the world where climate change has increased your chances of exposure to extreme heat and comprehensive adaptation strategies have yet to be developed.

Our bodies are not meant to work this hard under these kinds of conditions — and neither is the planet.

A Profound Imbalance of Power

So how did we arrive here? A rapid attribution analysis of the heat dome conducted by a global team of scientists revealed that the occurrence of this kind of heat wave was virtually impossible without human-caused climate change. Their results came with a strong warning: “our rapidly warming climate is bringing us into uncharted territory that has significant consequences for health, well-being and livelihoods. Adaptation and mitigation are urgently needed to prepare societies for a very different future.” The situation is only expected to get more dire — three billion people could live in places as hot as the Sahara by 2070 unless we address climate change with radical action and address it now.

The Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, released in August 2021, mirrors a similarly grave picture of our current climate reality and forecast of what lies ahead. In a bold, oppositional move against national governments who have edited the findings of such assessments in the past, a group of scientists leaked the third part of the report which reveals, in unequivocal terms, how fossil fuel industries propped up by state governments are some of the largest contributors to our current environmental condition and what needs to be done to shift course.

The report reminds us that human influence has warmed the climate at a rate that is unprecedented in at least the last 2000 years with a near-linear relationship between cumulative anthropogenic CO2 emissions and the global warming they cause. This means that we are no longer waiting for the arrival of climate change — it is here. It lives in the stifling hot air we breathe during unanticipated heat waves. It is the reason droughts are becoming more severe and at the same time flooding is driving millions of peoples’ lives into chaos, precariousness, and displacement. It explains why Arctic ice has reached its lowest levels since at least 1850. Ocean acidification exists because of it. And it is the driver behind environmental conditions that are expected to produce 200 million climate migrants over the next 30 years. We do not need more evidence. The science could not be more clear.

Human influence has warmed the climate at a rate that is unprecedented in at least the last 2000 years.

The answer to how we ended up here, however, cannot be collapsed into a homogenized “all of us are to blame” scenario that does little to differentiate how countries like the United States and other western nations have produced the vast majority of the carbon emissions that have led to this point of immense and disastrous planetary change. The US has contributed more to the problem of excess carbon dioxide than any other country on the planet, with the largest carbon footprints made by wealthy communities — the higher the household income, the greater the emissions. In fact, a Scientific American article explains that the United States, with less than 5 percent of the global population, uses about a quarter of the world’s fossil fuel resources — burning up nearly 23 percent of the coal, 25 percent of the oil, 27 percent of the aluminum and 19 percent of the copper.

A recent Oxfam report, Confronting Carbon Inequality, provides staggering revelations about the way correlations between wealth and carbon emissions extend out to the global context: the richest 1 percent on the planet are responsible for more than double the emissions of the poorest half of humanity, and the richest 10 percent in the world are accountable for over half of all emissions. Wealthy individuals and communities, though, are not the only source of dangerous and excessive carbon emissions — global corporations dedicated to the ongoing development and flourishing of fossil fuel energy infrastructure are also a major, if not the largest, part of the problem.