by DGR Editor | Oct 10, 2015 | Mining & Drilling

by Kim Hill

Ten things environmentalists need to know about renewable energy:

1. Solar panels and wind turbines aren’t made out of nothing. They are made out of metals, plastics, chemicals. These products have been mined out of the ground, transported, processed, manufactured. Each stage leaves behind a trail of devastation: habitat destruction, water contamination, colonization, toxic waste, slave labour, greenhouse gas emissions, wars, and corporate profits. Renewables can never replace fossil fuel infrastructure, as they are entirely dependent on it for their existence.

2. The majority of electricity that is generated by renewables is used in manufacturing, mining, and other industries that are destroying the planet. Even if the generation of electricity were harmless, the consumption certainly isn’t. Every electrical device, in the process of production, leaves behind the same trail of devastation. Living communities—forests, rivers, oceans—become dead commodities.

3. The aim of converting from conventional power generation to renewables is to maintain the very system that is killing the living world, killing us all, at a rate of 200 species per day. Taking carbon emissions out of the equation doesn’t make it sustainable. This system needs not to be sustained, but stopped.

4. Humans, and all living beings, get our energy from plants and animals. Only the industrial system needs electricity to survive, and food and habitat for everyone are being sacrificed to feed it. Farmland and forests are being taken over, not just by the infrastructure itself, but by the mines, processing and waste dumping that it entails. Ensuring energy security for industry requires undermining energy security for living beings (that’s us).

5. Wind turbines and solar panels generate little, if any, net energy (energy returned on energy invested). The amount of energy used in the mining, manufacturing, research and development, transport, installation, maintenance and disposal of these technologies is almost as much—or in some cases more than—they ever produce. Renewables have been described as a laundering scheme: dirty energy goes in, clean energy comes out. (Although this is really beside the point, as no matter how much energy they generate, it doesn’t justify the destruction of the living world.)

6. Renewable energy subsidies take taxpayer money and give it directly to corporations. Investing in renewables is highly profitable. General Electric, BP, Samsung, and Mitsubishi all profit from renewables, and invest these profits in their other business activities. When environmentalists accept the word of corporations on what is good for the environment, something has gone seriously wrong.

7. More renewables doesn’t mean less conventional power, or less carbon emissions. It just means more power is being generated overall. Very few coal and gas plants have been taken off line as a result of renewables.

8. Only 20 per cent of energy used globally is in the form of electricity. The rest is oil and gas. Even if all the world’s electricity could be produced without carbon emissions (which it can’t), it would only reduce total emissions by 20 per cent. And even that would have little impact, as the amount of energy being used globally is increasing exponentially.

9. Solar panels and wind turbines last around 20-30 years, then need to be disposed of and replaced. The production process, of extracting, polluting, and exploiting, is not something that happens once, but is continuous and expanding.

10. The emissions reductions that renewables intend to achieve could be easily accomplished by improving the efficiency of existing coal plants, at a much lower cost. Given that coal or gas plants are required for back-up of all intermittent renewables, this shows that the whole renewables industry is nothing but an exercise in profiteering with no benefits for anyone other than the investors.

Further Reading:

Green Technology and Renewable Energy

Ten Reasons Intermittent Renewables (Wind and Solar PV) are a Problem

The Myth of Renewable Energy

A Problem With Wind Power

Green Illusions: The Dirty Secrets of Clean Energy and the Future of Environmentalism

In China, the true cost of Britain’s clean, green wind power experiment: Pollution on a disastrous scale

Originally published on Stories of Creative Ecology

by DGR News Service | Oct 9, 2022 | ANALYSIS

Editor’s note: Contrary to what mainstream environmental organizations assert, so-called “renewable” energy is NOT a solution to the ecological crisis we are facing. It would require a tremendous amount of energy to mine materials; transport and transform them through industrial processes like smelting; turn them into solar panels, wind turbines, batteries, vehicles, infrastructure, and industrial machinery plus installation and maintenance. This is all done using the same systems of power which is currently used for conventional fossil fuels. The resulting emissions from these process will only add to the business as usual emissions. While the wind and sun may be “renewable,” the turbines, solar panels, the raw materials that go into making them, and the lands and oceans they impact certainly are not. They require tons of carbon emissions to produce so they are not carbon free and not green. Calling them “green” is greenwashing.

The proposed mass adoption of “renewable” energy on a hitherto undreamed of scale has made the issue of energy (power) density extremely important . In its simplest terms, power density can be understood as: ‘how big does my power station have to be, in order to generate the power I want?’ The most useful metric is the land (or sea) area that will be used up. Here, we encounter the most easily understood, and the most insoluble of “renewable” energy’s problems. Compared to fossil fuel, it’s power density is very very low. Thus, they require larger areas of land to produce. This land is someone’s home, someone’s sacred site, someone’s source of food, water and air. We just don’t hear about them, because they are the wild beings, the nonhumans treated as disposables by civilization. The humans that inhabit the land are indigenous peoples who are yet to be fully assimilated into the industrial culture. Here, we can see colonialism and extractive economics come together.

The following article describes the plans for different “renewable” energy plants in California and Nevada. The article also demonstrates how the plans for big “renewables” actively reinforce the existing structures of power, with the energy companies lobbying to disincentivize decentralized and community-controlled rooftop solars in favor of big projects that are destroying the neighbors.

By Joshua Frank/Counterpunch

There is a lot of hot air blowing around the West these days, blustery claims that geothermal, wind, massive solar installations, nuclear power, along with a smattering of hydroelectric dams, will help the country achieve a much-needed reduction in climate-altering emissions. Certainly, there is money to be made off of this energy transition, and on paper, a few do appear to be far less damaging than coal-fired power plants and natural gas operations.

That’s if, of course, you ignore the toll these energy ventures have on the lands and people they exploit. Right now, not far from where I live in Southern California, solar companies are gobbling up public and private lands for future solar and wind projects.

Across the border in Nevada, desert is under threat of being developed in the name of fighting climate change. In the rich and biodiverse Dixie Valley, located in the middle of sacred Shoshone and Paiute lands, a massive geothermal project called the Dixie Meadows Geothermal Development Project faced a fierce legal challenge this past year. Geothermal, like hydroelectric dams, is often cited as a renewable energy source, since the technology harnesses heat from the earth to produce electricity, which in theory (as long as it doesn’t stop raining, surprise!), is endless.

Even so, large geothermal plants consume a lot of land and spit out a lot of water. The Dixie Meadows project, which was proposed in Nevada, was one such “green” energy plan that, if built, would suck up over 40,000 thousand acre-feet of water every single year, the result of which would be devasting. Dixie’s delicate wetlands habitat, unique to this stretch of the Great Basin, is home to the imperiled black-freckled Dixie Valley toad, and even a slight alteration of surface water conditions could spell extinction for this rare little toad. Birds too use Dixie’s natural spring water as migratory stopovers. Dixie Meadows is a literal oasis in the desert and has been for tens of thousands of years.

“The United States has repeatedly promised to honor and protect indigenous sacred sites, but then the BLM approved a major construction project nearly on top of our most sacred hot springs. It just feels like more empty words,” said Fallon Paiute-Shoshone Tribal Chairwoman Cathi Tuni following the announcement of the Dixie Meadows project. “This location has long been recognized as being of vital significance to the Tribe. There are geothermal plants elsewhere in Dixie Valley and the Great Basin that we have not opposed, but construction of this plant would build industrial power plants right next to a sacred place of healing and reflection, and risks damaging the water in the springs forever. We have a duty to protect the hot springs and its surroundings, and we will do so.”

On December 16, 2021, The Fallon Paiute-Shoshone Tribe and the Center of Biological Diversity (Center) sued the BLM over its approval of the Dixie Meadows geothermal project, and in early August were successful in stopping it from moving forward.

“I’m thrilled that yet again the bulldozers are grinding to a halt as a result of our legal actions,” said Patrick Donnelly, Great Basin director at the Center. “Nearly every scientist who has evaluated this project agrees that it puts the Dixie Valley toad in the crosshairs of extinction. This agreement gives the toad a fighting shot.”

***

About 270 miles south of Dixie Meadows, another “green” energy plan is in the works near the remote Searchlight, Nevada. The Kulning Wind Project, proposed by Eolus Vind AB, a Swedish power developer, is not unlike other wind projects that were halted in 2017 and 2018 after an outcry from local Tribes and conservationists. Kulning, like the prospects that were shot down, is massive and would include 68 wind turbines spanning 9,300 acres of federal lands on the site of the proposed Avi Kwa Ame (Ah-VEE kwa-meh) National Monument. Like Dixie Meadows, Kulning would greatly impact local wildlife.

“[The] development would likely undermine the use of the region by bighorn sheep and would introduce an unnecessary wildfire risk, threatening Wee Thump and South McCullough wildernesses, among many other concerns,” says Paul Selberg, director of Nevada Conservation League. “Decisions on where to develop renewable energy must be evaluated critically and placed in areas that are appropriate.”

The real question is; are expansive energy projects, be they fossil fuels or “green”, ever really “appropriate”? Indigenous communities and conservationists are wary.

The land outside Searchlight where these huge twirling wings are to be erected is considered a sacred “place of creation” to 12 local tribes, including the Havasupai, Hualapai, Kumeyaay, Maricopa, Mojave, Pai Pai, Quechan, and Yavapai. Opponents of the development, led by a broad coalition of tribes, point out that this stretch of the Mojave is some of the most pristine, in-tact wilderness in the Southwest.

Joshua trees (known as sovarampi to the Southern Paiute) in this area, which make up the largest Joshua forest in Nevada, will be destroyed if the project moves forward. These distinctive, twisted trees are already facing a bleak future in the West. Mojave’s high desert is becoming even hotter and drier than normal, dropping nearly 2 inches from its average of just over 4.5 inches of annual rainfall just a decade ago. The result: younger Joshua trees, which grow at a snail’s pace of 3 inches per year, are perishing before they reach a foot in height. Their vanishing is an indicator that these peculiar trees will not be replenished once they grow old and die, and they are dying at a startling rate.

While it has not received as much attention as Bears Ears or Gold Butte, Avi Kwa Ame National Monument is equally important as an ecological and cultural site, which would span 450,000 acres, protecting the delicate landscape from energy developers (to support the proposed monument, you can sign a petition here).

At the center of this onslaught of development is California’s quest to end the use of fossil fuels. Most of the energy in the state, one of the largest energy consumers in the country, is generated from utility-scale wind and solar, which, as of 2016, has required over 400,000 square kilometers of land to produce. This development, because it is billed as “green” energy, has received little scrutiny from the broader environmental movement. As a result, studies on the effects on biodiversity and threatened species, like the Desert Tortoise, are virtually non-existent.

***

In Northern Nevada, a similar fight is raging over Thacker Pass, where a proposed mine would produce upwards of 80,000 tons of lithium per year, a mineral that is crucial for most electric car batteries. Lithium Nevada, the company spearheading the Thacker project, is facing strong pushback from activists and members of Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone, among others.

“Places like Thacker Pass are what gets sacrificed to create that so-called clean energy,” says author and activist Max Wilbert. “It is easy to say the sacrifice is justifiable if you do not live here.”

Indigenous communities are equally upset at the plan.

“Annihilating old-growth sagebrush, Indigenous peoples’ medicines, food, and ceremonial grounds for electric vehicles isn’t very climate conscious,” said Arlan Melendez, the chair of the Reno-Sparks Indian Colony.

Opposition to the lithium mine has invigorated a new, vibrant protest movement in Nevada, led by Indigenous activists that see these developments for what they are: a continuation of settler-colonialism, an onslaught fully supported by the Democrats and the Biden Administration. In the case of EVs, Biden’s 2021 American Jobs Plan earmarked $174 billion to promote electric vehicles. The Thacker mine, claims Lithium Nevada, is central to those efforts.

There are also alternatives to lithium like seawater, sodium, and glass batteries. While none are environmentally benign, the impacts do vary. Maria Helena Braga a scientist at the University of Porto in Portugal, who has been researching glass battery technology, believes glass has the brightest future. “It’s the most eco-friendly cell you can find,” claims Braga.

Recently, researchers at the University of California San Diego’s Center for Interdisciplinary Environmental Justice disagreed that we need to mine our way out of climate change, stating that in order to curb greenhouse gas emissions we would have to decrease our output by 80% over the next thirty years. EVs, they claim, would only reduce greenhouse gases by 6%. In other words, the destruction these mines cause is not worth such little benefit. A larger, far more significant transition is needed.

***

In addition to technological advances (and the need to consume less), the energy grid itself must be revamped, from centralized sources of energy like coal or natural gas to a decentralized network of producers, where existing homes and commercial buildings are required to install solar on their rooftops. Big utilities, like PG&E in California, which has been responsible for causing over 1,500 fires and hundreds of deaths in the state, are not pleased with the push for community-controlled, decentralized power. In fact, in an effort to disincentivize rooftop solar, California regulators, after heavy lobbying from energy companies, are currently pushing to slash residential solar incentives, making the transition even more difficult, while supporting large desert developments in the process.

Hundreds of plans for large renewable energy projects are currently in the works in California, New Mexico, and Nevada, and one by one they are set to destroy vast stretches of desert habitat. In 2015, researchers from UC Berkeley and UC Riverside looked at 161 proposed and operational solar plants. What they found was startling. Only 10-15 percent of the projects in California were located in areas that would have little impact on their surroundings. In other words, 85% of these would harm the environments where they’re located.

“We would hope that if a developer was on the ground and saw that, oh, this is a really important area for migratory birds, maybe we should look at that Walmart commercial roof down the road, and collaborate with them rather than putting it here,” said the study’s lead author Rebecca Hernandez, a scientist at UC Berkeley.

While the push for decentralizing is paramount, some argue that locating green energy installations in already impacted areas, like brownfields, is a good alternative. Yet this is rarely the most profitable choice. At the heart of the problem is that public lands in the desert west are inexpensive. The Bureau of Land Management leases huge parcels of these lands for dirt cheap, which in turn incentivizes large-scale wind and solar projects — projects that support Biden’s climate plan, where companies like PG&E will continue to control the grid and small-scale projects will be difficult and expensive to build.

If the goal of clean, green energy is to offset the wrath of climate catastrophe, yet damages sensitive habitats in the process, are these projects even worthwhile? That’s a question environmentalists and others must grapple with. Certainly, they are good for profit margins, but the evidence is mounting that they are also devastating to desert ecology.

JOSHUA FRANK is the managing editor of CounterPunch. He is the author of the forthcoming book, Atomic Days: The Untold Story of the Most Toxic Place in America, published by Haymarket Books. He can be reached at joshua@counterpunch.org. You can troll him on Twitter @joshua__frank.

Featured image by Antonio Garcia via Unsplash

by DGR News Service | Jan 23, 2021 | Human Supremacy

by Cara Judea Alhadeff, PhD

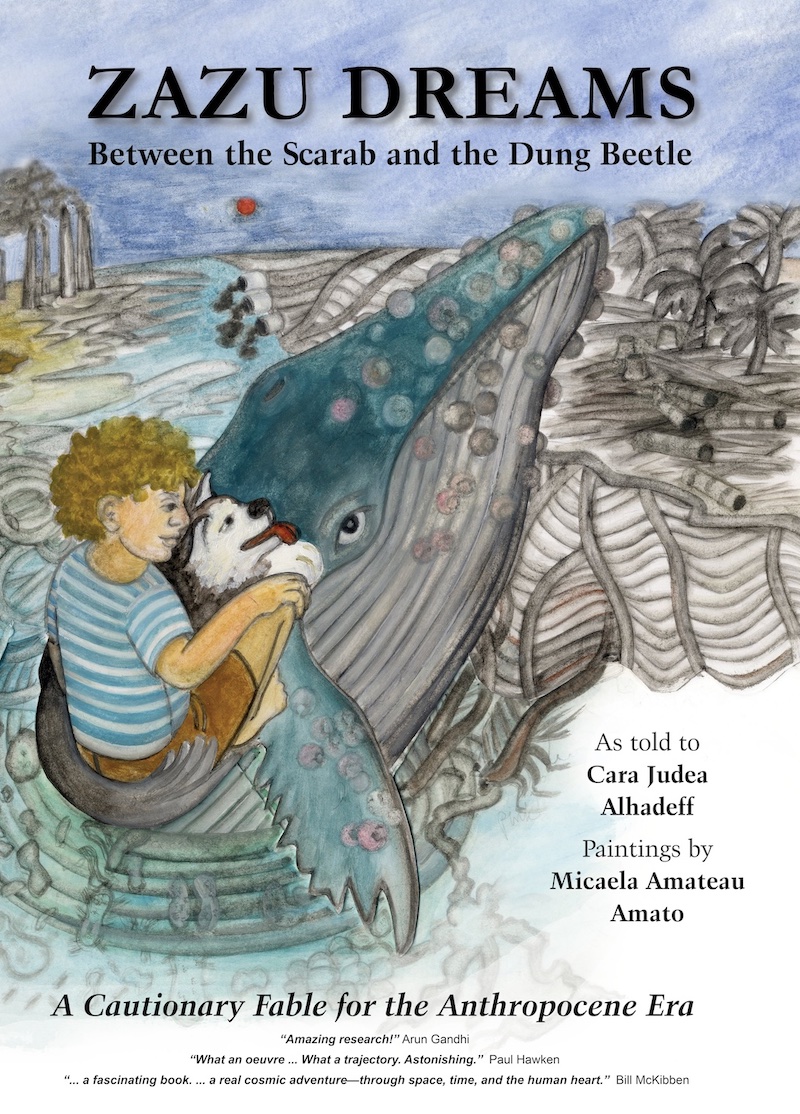

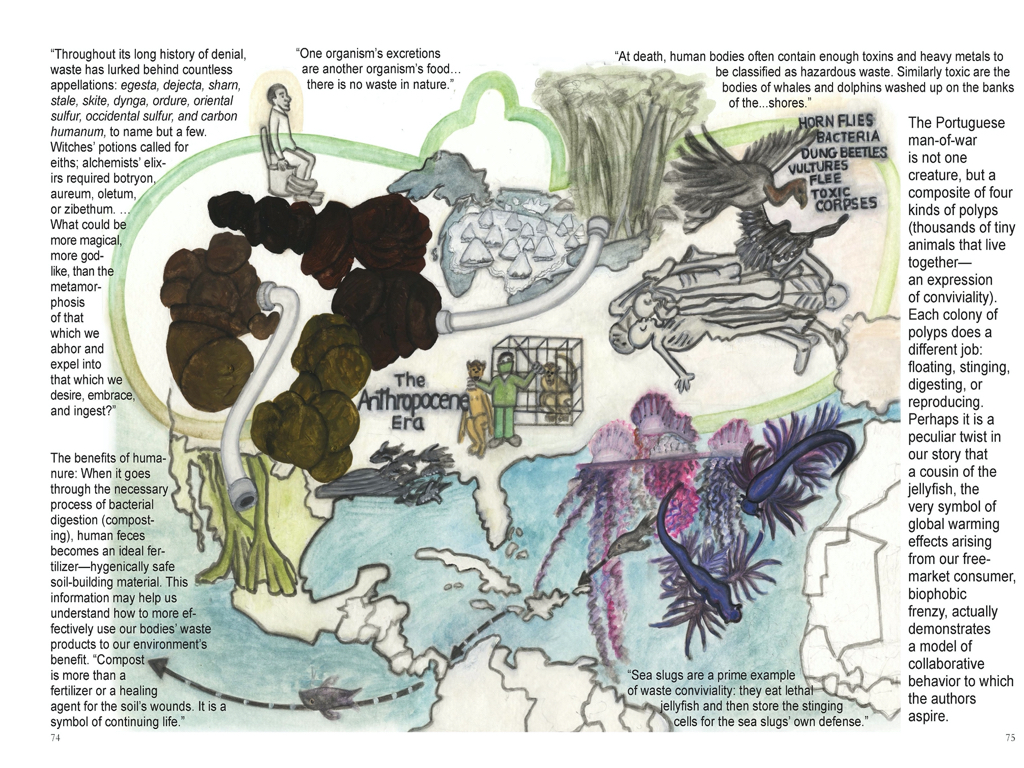

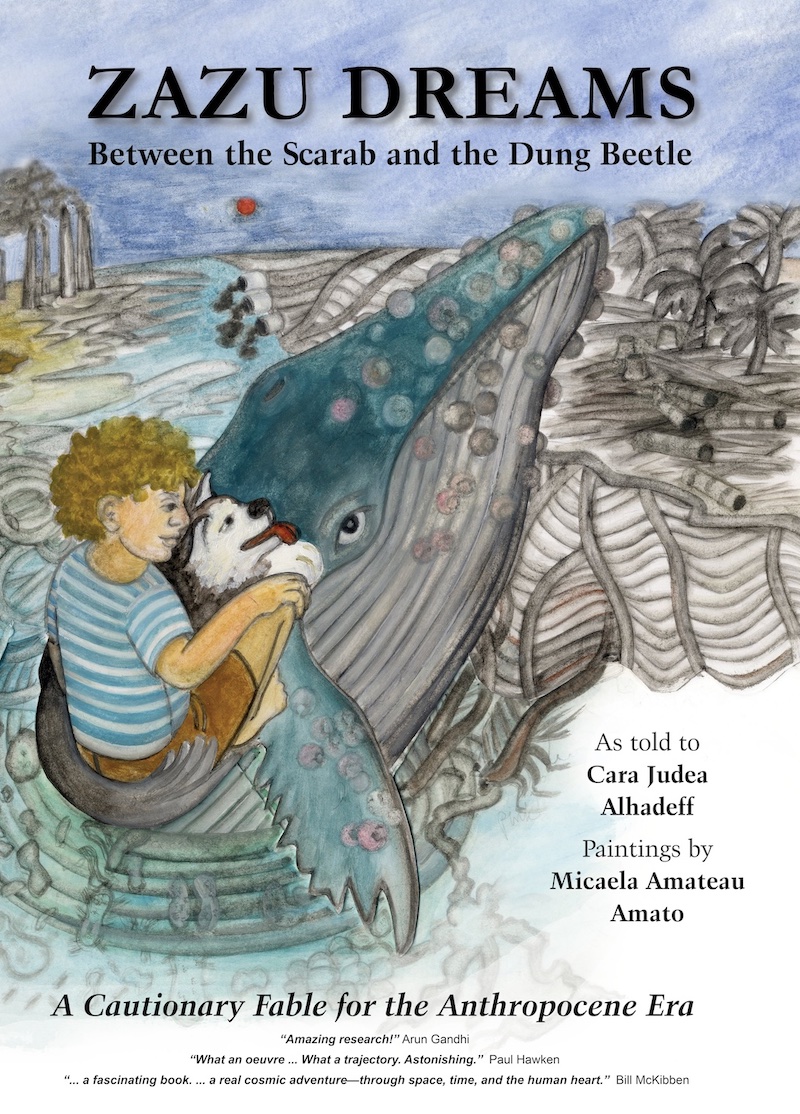

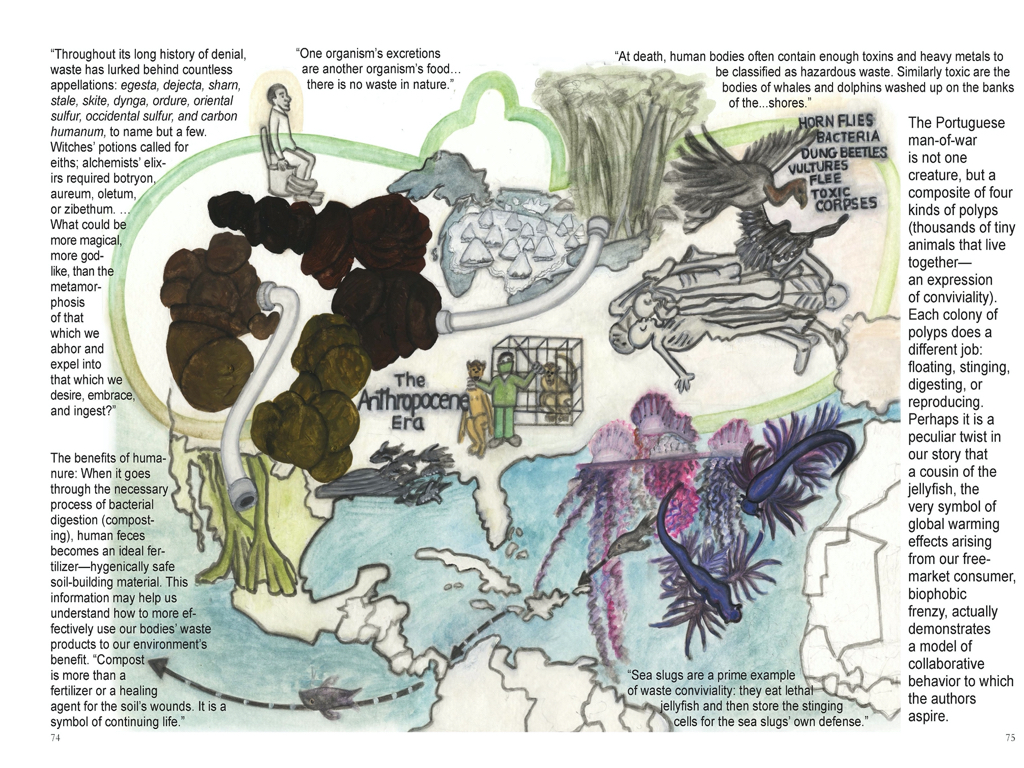

Paintings in this post are by Micaela Amateau Amato from Zazu Dreams: Between the Scarab and the Dung Beetle, A Cautionary Fable for the Anthropocene Era.

The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House —Audre Lorde

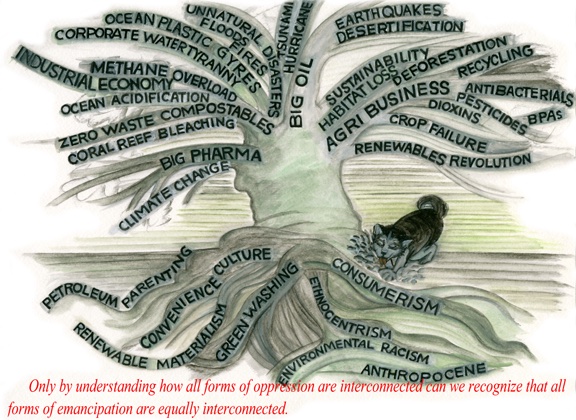

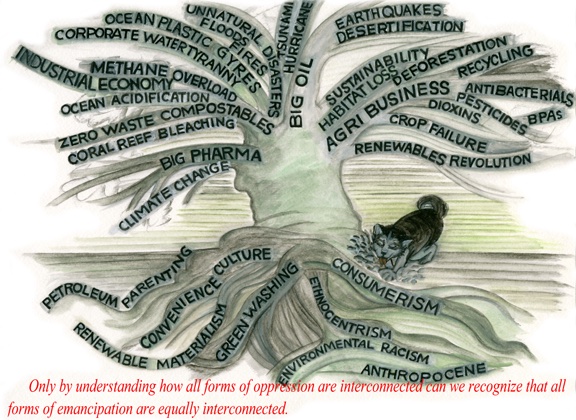

As with our shift from our systemically racist culture to one rooted in mutual respect for multiplicity and difference, we must practice caution during our transition out of our global petroculture. This vigilance should not be based on the motivation, but on the underlying false assumptions and strategies that perceived sustainability and “alternative” agendas offer. The implicit assumptions embedded in the concept of sustainability maintains the status quo. At this juncture of geopolitical, ecological, social, and corporeal catastrophes, we must critically question clean/green solutions such as the erroneously-named Renewable Energies Revolution. I suggest we face both the roots and the implications of how perceived solutions to our climate crisis, like “renewable” energies, may unintentionally sustain ecological devastation and global wealth inequities, and actually divert us from establishing long-term, regenerative infrastructures.

On the surface, sustainability agendas appear to offer critical shifts toward an ecologically, economically, and ethically sound society, but there is much evidence to prove that #1: these structural changes must be accompanied by a psychological shift in individuals’ behavior to effectively shut down consumer-waste convenience culture; and, #2: the core of too many green/clean solutions is rooted in the very essence of our climate crisis: privatized, industrialized-corporate capitalism. For example, in his The Age of Disinformation1, Eric Cheyfitz alerts us: The Green New Deal is a “capitalist solution to a capitalist problem.” It claims to address the linked oppressions of wealth inequity and climate-crisis, yet its proposed solutions avoid the very roots of each crisis.

My challenge is rooted in three interrelated inquiries:

- How are our daily choices reinforcing the very racist systems we are questioning or even trying to dismantle?

- How are the alternatives to fossil-fuel economies and environmental racism reinforcing the very systems we are questioning or even trying to dismantle?

- What can we learn from indigenous philosophies and socialist ecofeminist movements in order to establish viable, sustainable, regenerative infrastructures—an Ecozoic Era?

As we transition to supposedly carbon-free electricity, we must be attentive to the ways in which we unconsciously manifest the very racist hegemonies we seek to dislodge; we must be cautious of the greening-of-capitalism that manifests as “green colonialism” through a new dependency on what is falsely identified as “renewable” energies. Currently, human and natural-world habitat destruction are implicit in the mass production and disposal infrastructures of most “renewable energies:” solar, wind, biomass/biofuels, geothermal, ethanol, hydrogen, nuclear, and other ostensible renewables2.

This includes our technocratic petroleum-pharmaceutical addictions that use technologies to create “sustainability.” Even if policy appears to be in alignment with environmental ethics, we are consistently finding that policy change simply replaces one hegemony, one cultural of domination, with another—particularly within the framework of neoliberal globalization. Only when we acknowledge the roots of our Western imperialist crisis, can we begin to decolonize and revitalize all peoples’ livelihoods and their environments.

Zazu Dreams: Between the Scarab and the Dung Beetle, A Cautionary Fable for the Anthropocene Era3, my climate justice book that explores the perils of the Anthropocene, challenges cultural habits deeply embedded in our calamitous trajectory toward global ecological and cultural, ethnic collapse. The book’s main character reflects: “We have this crazy idea that anything ‘green’ is good—but we know that there is no clear-cut good and evil. What happens when the very solution causes more problems than the original problem it was supposed to fix?”

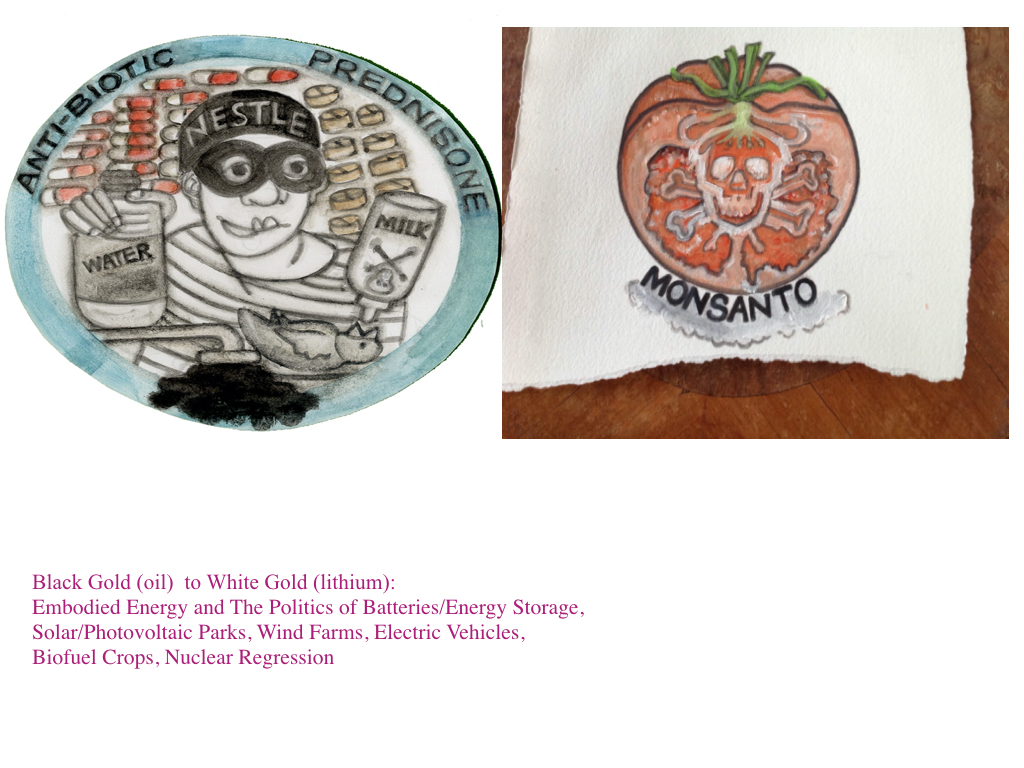

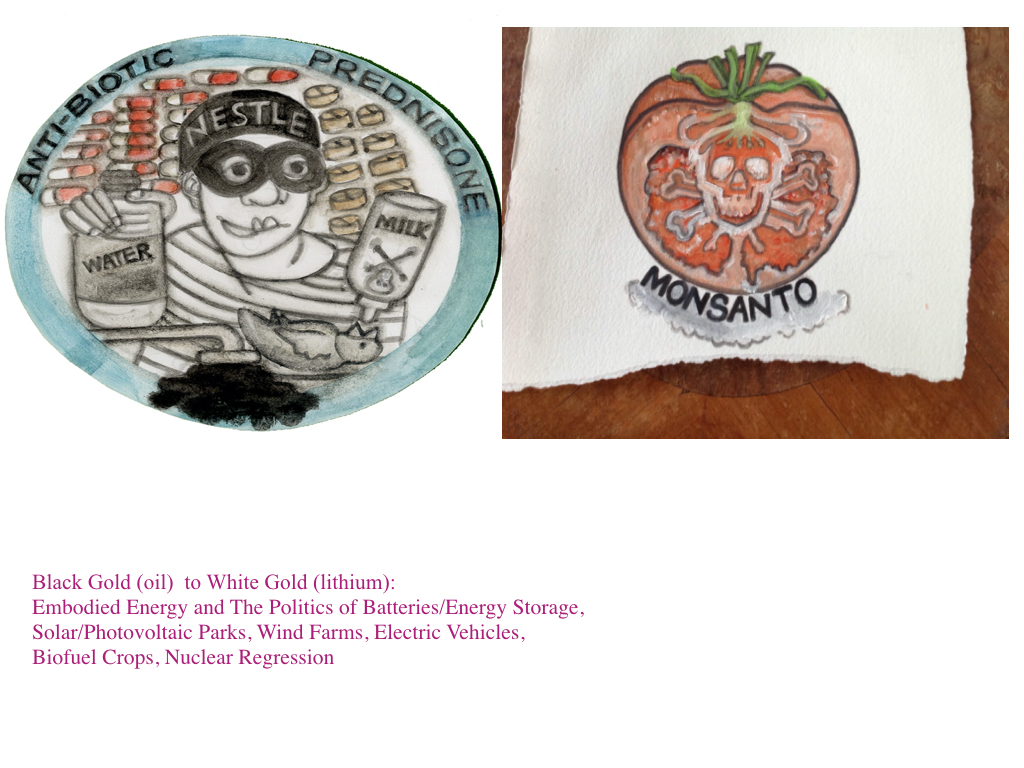

How we measure our ecological footprint4 and global biocapacity is often riddled with paradox—particularly in the face of green colonialism, or what I call humanitarian imperialism5. The litany of our collusion with corporate forms of domination is infinite within the Anthropocene Era (increasingly characterized as the Plasticene). Disinformation campaigns spread by fossil-fuel interests deeply root us in assimilationist consumerism. The Zazu Dreams’ characters witness social and environmental costs of subjugating others through both fossil-fuel-obsessed economies and their “green” replacements. Vaclav Smil warns us of this “Miasma of falsehood.” This implies replacing one destructive socializing norm—petro-pharma cultures sustained by fossil-fuel addicted economics—with another: purportedly “renewable” energies. These energies (I don’t call them renewable, because they are not “renewable” and not carbon-free)6, like fossil-fuels, are rooted in barbaric colonialist extractive industries. Once again, the “solution” is precisely the problem. Greenwashing is a prime example of the ways in which capitalism dictates our alleged freedom. Free market is a euphemism for economic terrorism. The “green economy has come to mean…the wholesale privatization of nature.”7 Consumerism becomes the default for making supposedly ethical choices.

In Deep Green Resistance, Lierre Keith urges us: “We can’t consume our way out of environmental collapse; consumption is the problem”. Even within the 99%, consumers are capitalism. Without convenience-culture/mass consumer-demand, the machine of the profit-driven free market would have to shift gears. We can’t blame oil companies without simultaneously implicating ourselves, holding our consumption-habits equally responsible. How can we insist government and transnational corporations be accountable, when we refuse to curb our buying, using, and disposal habits? We don’t have to go far back in our cross-cultural histories of nonviolent resistance and civil disobedience to learn from world-changing examples of strikes, unions, boycotts, expropriation, infrastructural sabotage, embargoes, and divestment protests.

Yet, most contemporary transition movements are founded in the very system they are trying to dismantle. Our perceived resources, these alternative forms of energy proposed to power our public electrical grids, are misidentified under the misleading misnomers: labels such “renewable”/ “sustainable” / “clean”/ “green”. How is “clean” defined? For whom? There is not a clear division between clean energy and dirty energy/dirty power—clean isn’t always clean. Neoliberal denial of corporeal and global interrelationships instills conformist laws of conduct that continually replenish our toxic soup in which we all live. One perceived solution to help us transition is to create alternatives to fossil fuel-addicted economies, as proposed, for example, through The United States’ proposed Green New Deal and its focus on allegedly “renewable” energies. However well-intentioned, these supposed alternatives perpetuate the violence of wasteful behavior and destructive infrastructures. Even if temporarily abated, they ultimately conserve the original crisis.

Below I address specific technologies that are falsely identified as “renewable” energy; technologies that actually reinforce the very problem they are trying to solve.

1. Solar/Photovoltaic and Wind Technologies: Given the proposed solutions using industrial solar and wind harvesting, Western imperialism has and will continue to dominate global relations. “Clean energy” easily gets soiled when it is implemented on an industrial scale. Western imperialist practices are implicit in solar cell and storage production (mining and other extractive industries) and disposal infrastructures. Congruently, industrial wind farms—aka: “blenders in the sky,”(chopping up migrating birds & bats) use exorbitant resources to produce and implement (both the wind turbines and their infrastructure), and devastate migrating wildlife (bats and birds, critical to healthy ecosystems and some of whom are endangered species).

Both wind and solar energies require vast quantities of fossil fuels to implement them on a grand scale. As we have seen throughout both California and China (two examples among too many), massive solar-energy sites/solar industrial complexes strip land bare—displacing human populations and migration routes of both wildlife and people for acres of solar fields, substations, and access roads—all of which require incredibly carbon-intensive concrete. Consuming massive tracts of land, 100-1000 times more land area is required for wind and solar, as well as for biofuel energy production than does fossil-fuel production.

2. Hydro-Power Technology: Large-scale dams for hydro-power have also historically had cataclysmic effects on indigenous peoples and their lands. Although macro-hydro, like fracking, has

finally been recognized for its calamitous consequences, perversely, it is still proposed as a viable alternative to fossil-fuel economies.

3. Battery Technology: Let’s begin with a California-based scenario: According to the Union of Concerned Scientists and their Climate Vulnerability Index (CVI) in California, fine particulate pollution harms African-American communities 43% more than predominantly white communities, Latino 39% more, and Asian-American communities 21% more. As if tailpipe emissions are the only humanitarian catastrophe, one “clean solution” is the electric vehicle for public transportation and for personal consumption. Completely ignoring the embodied energy involved, this perceived solution displaces the costs of environmental racism—once again exported out of the US into the global south—in this case to Boliva where lithium (essential for battery production) is primarily mined. Cobalt, also essential to battery production, is mined in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Like lithium, cobalt’s environmental and humanitarian costs are unconscionable—including habitat destruction, child slavery, and deaths. Eventually, production is followed by solar technology and battery e-waste dispersed throughout Asia, South America, and Africa. Additionally, rarely considered are the fossil-fuel sources used to supply the electricity for those private and public electric vehicles. And, of course most frequently, the poorest US populations work in and live near those coal mines/power plants/fracking stations.

The Renewable Energies Movement claims that our global addiction to oil (“black gold”) should be replaced by lithium (“white gold”). What we are not considering is that extracting lithium and converting it to a commercially viable form consumes copious quantities of water—drastically depleting availability for indigenous communities and wildlife, and produces toxic waste (that includes an already growing history of chemical leaks poisoning rivers, thus people and other animals). Paul Hawken‘s phrase “renewable materialism” counsels us that this hyper-idealized shift from a fossil-fuel paradigm to “renewable” energies is not a solution. Furthermore, these energies are LOW POWER DENSITY: they produce very little energy in proportion to the energy required to institutionalize them.

As the main character in Zazu Dreams prompts: “Even if we find great alternatives to fossil fuels, what if renewable energies become big business and just maintain our addiction to consumption? (…) Replacing tar sands or oil-drills or coal power plants with megalithic ‘green’ energy is not the solution—it just masks the original problem—confusing ‘freedom’ with free market and free enterprise”. We must now act on our knowledge that the renewable “revolution” is dangerously carbon intensive. And, as the authors of Deep Green Resistance caution us: “The new world of renewables will look exactly like the old in terms of exploitation.”

ENDNOTES

- Eric Cheyfitz, Age of Disinformation: The Collapse of Liberal Democracy in the United States. New York: Routledge, 2017.

- Surrogate band-aids that are frequently equal to or worse than what is being replaced include: bioplastics, phthalates replacements, and HFC’s. 1.Compostable disposables, also known as bioplastics, are most frequently produced from GMO-corn monoculture and “composted” in highly restricted environments that are inaccessible to the general public. Due to corn-crop monoculture practices that are dependent on agribusiness’s heavy use of pesticides and herbicides (for example, Monsanto’s Round-Up/glyphosate), compostable plastics are not a clean solution. Depending on their production practices, avocado pits may be a more sustainable alternative. But, the infrastructure and politics of actually “composting” these products are extraordinarily problematic. These not-so eco-friendly products rarely make it into the high temperatures needed for them to actually decompose. Additionally, their chemical compounds cause extreme damage to water, soil, and wildlife. They cause heavy acidification when they get into the water and eutrophication (lack of oxygen) when they leach nitrogen into the soil. 2.The trend to replace Bisphenol A (BPA) led to even more debilitating phthalates in products. 3.Lastly, we now know that hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), “ozone-friendly” replacements, are equally environmentally destructive as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs).

- Cara Judea Alhadeff, Zazu Dreams: Between the Scarab and the Dung Beetle, A Cautionary Fable for the Anthropocene Era. Berlin: Eifrig Publishing, 2017.

- The term “carbon footprint” was actually normalized through shame-propaganda by BP’s advertising campaigns. “The carbon footprint sham: A ‘successful, deceptive’ PR campaign,” Mark Kaufman, https://mashable.com/feature/carbon-footprint-pr-campaign-sham/

- Under the guise of the common good and universal values, humanitarian imperialism has emerged as a neo-colonialist method of reproducing the unquestioned status quo of industrialized, “First World” nations. For a detailed deracination of these fantasies (for example, taken-for-granted concepts of equality, poverty, standard of living), see Wolfgang Sachs’ anthology, The Development Dictionary: A Guide to Knowledge as Power. Although the term humanitarian imperialism is not explicitly used, all of the authors explore the hierarchical, ethnocentric assumptions rooted in development politics and unexamined paradigms of Progress. As public intellectuals committed to the archeology of prohibition and power distribution, we must extend this discussion beyond the context of international development politics and investigate how these normalized tyrannies thrive in our own backyard.

- The air and sun are renewable, but giant wind and solar installations are not.

- Jeff Conant, “The Dark Side of the ‘Green Economy,’” Yes! Magazine, August 2012, 63.

by DGR News Service | Oct 12, 2020 | Building Alternatives

This piece from Low-Tech Magazine examines the practice of coppicing trees for firewood and other uses. The author argues that this practice offers a sustainable, low-tech, small-scale alternative to industrial logging, and doesn’t threaten to accelerate global warming. While we don’t agree with every element of this piece, it is a very important article.

by Kris De Decker / Low-Tech Magazine

From the Neolithic to the beginning of the twentieth century, coppiced woodlands, pollarded trees, and hedgerows provided people with a sustainable supply of energy, materials, and food.

Pollarded trees in Germany. Image: René Schröder (CC BY-SA 4.0).

How is Cutting Down Trees Sustainable?

Advocating for the use of biomass as a renewable source of energy – replacing fossil fuels – has become controversial among environmentalists. The comments on the previous article, which discussed thermoelectric stoves, illustrate this:

- “As the recent film Planet of the Humans points out, biomass a.k.a. dead trees is not a renewable resource by any means, even though the EU classifies it as such.”

- “How is cutting down trees sustainable?”

- “Article fails to mention that a wood stove produces more CO2 than a coal power plant for every ton of wood/coal that is burned.”

- “This is pure insanity. Burning trees to reduce our carbon footprint is oxymoronic.”

- “The carbon footprint alone is just horrifying.”

- “The biggest problem with burning anything is once it’s burned, it’s gone forever.”

- “The only silly question I can add to to the silliness of this piece, is where is all the wood coming from?”

In contrast to what the comments suggest, the article does not advocate the expansion of biomass as an energy source. Instead, it argues that already burning biomass fires – used by roughly 40% of today’s global population – could also produce electricity as a by-product, if they are outfitted with thermoelectric modules. Nevertheless, several commenters maintained their criticism after they read the article more carefully. One of them wrote: “We should aim to eliminate the burning of biomass globally, not make it more attractive.”

Apparently, high-tech thinking has permeated the minds of (urban) environmentalists to such an extent that they view biomass as an inherently troublesome energy source – similar to fossil fuels. To be clear, critics are right to call out unsustainable practices in biomass production. However, these are the consequences of a relatively recent, “industrial” approach to forestry. When we look at historical forest management practices, it becomes clear that biomass is potentially one of the most sustainable energy sources on this planet.

Coppicing: Harvesting Wood Without Killing Trees

Nowadays, most wood is harvested by killing trees. Before the Industrial Revolution, a lot of wood was harvested from living trees, which were coppiced. The principle of coppicing is based on the natural ability of many broad-leaved species to regrow from damaged stems or roots – damage caused by fire, wind, snow, animals, pathogens, or (on slopes) falling rocks. Coppice management involves the cutting down of trees close to ground level, after which the base – called the “stool” – develops several new shoots, resulting in a multi-stemmed tree.

A coppice stool. Image: Geert Van der Linden.

A recently coppiced patch of oak forest. Image: Henk vD. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Coppice stools in Surrey, England. Image: Martinvl (CC BY-SA 4.0)

When we think of a forest or a tree plantation, we imagine it as a landscape stacked with tall trees. However, until the beginning of the twentieth century, at least half of the forests in Europe were coppiced, giving them a more bush-like appearance. [1] The coppicing of trees can be dated back to the stone age, when people built pile dwellings and trackways crossing prehistoric fenlands using thousands of branches of equal size – a feat that can only be accomplished by coppicing. [2]

The approximate historical range of coppice forests in the Czech Republic (above, in red) and in Spain (below, in blue). Source: “Coppice forests in Europe”, see [1]

Ever since then, the technique formed the standard approach to wood production – not just in Europe but almost all over the world. Coppicing expanded greatly during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when population growth and the rise of industrial activity (glass, iron, tile and lime manufacturing) put increasing pressure on wood reserves.

Short Rotation Cycles

Because the young shoots of a coppiced tree can exploit an already well-developed root system, a coppiced tree produces wood faster than a tall tree. Or, to be more precise: although its photosynthetic efficiency is the same, a tall tree provides more biomass below ground (in the roots) while a coppiced tree produces more biomass above ground (in the shoots) – which is clearly more practical for harvesting. [3] Partly because of this, coppicing was based on short rotation cycles, often of around two to four years, although both yearly rotations and rotations up to 12 years or longer also occurred.

Coppice stools with different rotation cycles. Images: Geert Van der Linden.

Because of the short rotation cycles, a coppice forest was a very quick, regular and reliable supplier of firewood. Often, it was cut up into a number of equal compartments that corresponded to the number of years in the planned rotation. For example, if the shoots were harvested every three years, the forest was divided into three parts, and one of these was coppiced each year. Short rotation cycles also meant that it took only a few years before the carbon released by the burning of the wood was compensated by the carbon that was absorbed by new growth, making a coppice forest truly carbon neutral. In very short rotation cycles, new growth could even be ready for harvest by the time the old growth wood had dried enough to be burned.

In some tree species, the stump sprouting ability decreases with age. After several rotations, these trees were either harvested in their entirety and replaced by new trees, or converted into a coppice with a longer rotation. Other tree species resprout well from stumps of all ages, and can provide shoots for centuries, especially on rich soils with a good water supply. Surviving coppice stools can be more than 1,000 years old.

Biodiversity

A coppice can be called a “coppice forest” or a “coppice plantation”, but in reality it was neither a forest nor a plantation – perhaps something in between. Although managed by humans, coppice forests were not environmentally destructive, on the contrary. Harvesting wood from living trees instead of killing them is beneficial for the life forms that depend on them. Coppice forests can have a richer biodiversity than unmanaged forests, because they always contain areas with different stages of light and growth. None of this is true in industrial wood plantations, which support little or no plant and animal life, and which have longer rotation cycles (of at least twenty years).

Coppice stools in the Netherlands. Image: K. Vliet (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Sweet chestnut coppice at Flexham Park, Sussex, England. Image: Charlesdrakew, public domain.

Our forebears also cut down tall, standing trees with large-diameter stems – just not for firewood. Large trees were only “killed” when large timber was required, for example for the construction of ships, buildings, bridges, and windmills. [4] Coppice forests could contain tall trees (a “coppice-with-standards”), which were left to grow for decades while the surrounding trees were regularly pruned. However, even these standing trees could be partly coppiced, for example by harvesting their side branches while they were alive (shredding).

Multipurpose Trees

The archetypical wood plantation promoted by the industrial world involves regularly spaced rows of trees in even-aged, monocultural stands, providing a single output – timber for construction, pulpwood for paper production, or fuelwood for power plants. In contrast, trees in pre-industrial coppice forests had multiple purposes. They provided firewood, but also construction materials and animal fodder.

The targeted wood dimensions, determined by the use of the shoots, set the rotation period of the coppice. Because not every type of wood was suited for every type of use, coppiced forests often consisted of a variety of tree species at different ages. Several age classes of stems could even be rotated on the same coppice stool (“selection coppice”), and the rotations could evolve over time according to the needs and priorities of the economic activities.

A small woodland with a diverse mix of coppiced, pollarded and standard trees. Image: Geert Van der Linden.

Coppiced wood was used to build almost anything that was needed in a community. [5] For example, young willow shoots, which are very flexible, were braided into baskets and crates, while sweet chestnut prunings, which do not expand or shrink after drying, were used to make all kinds of barrels. Ash and goat willow, which yield straight and sturdy wood, provided the material for making the handles of brooms, axes, shovels, rakes and other tools.

Young hazel shoots were split along the entire length, braided between the wooden beams of buildings, and then sealed with loam and cow manure – the so-called wattle-and-daub construction. Hazel shoots also kept thatched roofs together. Alder and willow, which have almost limitless life expectancy under water, were used as foundation piles and river bank reinforcements. The construction wood that was taken out of a coppice forest did not diminish its energy supply: because the artefacts were often used locally, at the end of their lives they could still be burned as firewood.

Harvesting leaf fodder in Leikanger kommune, Norway. Image: Leif Hauge. Source: [19]

Coppice forests also supplied food. On the one hand, they provided people with fruits, berries, truffles, nuts, mushrooms, herbs, honey, and game. On the other hand, they were an important source of winter fodder for farm animals. Before the Industrial Revolution, many sheep and goats were fed with so-called “leaf fodder” or “leaf hay” – leaves with or without twigs. [6]

Elm and ash were among the most nutritious species, but sheep also got birch, hazel, linden, bird cherry and even oak, while goats were also fed with alder. In mountainous regions, horses, cattle, pigs and silk worms could be given leaf hay too. Leaf fodder was grown in rotations of three to six years, when the branches provided the highest ratio of leaves to wood. When the leaves were eaten by the animals, the wood could still be burned.

Pollards & Hedgerows

Coppice stools are vulnerable to grazing animals, especially when the shoots are young. Therefore, coppice forests were usually protected against animals by building a ditch, fence or hedge around them. In contrast, pollarding allowed animals and trees to be mixed on the same land. Pollarded trees were pruned like coppices, but to a height of at least two metres to keep the young shoots out of reach of grazing animals.

Pollarded trees in Segovia, Spain. Image: Ecologistas en Acción.

Wooded meadows and wood pastures – mosaics of pasture and forest – combined the grazing of animals with the production of fodder, firewood and/or construction wood from pollarded trees. “Pannage” or “mast feeding” was the method of sending pigs into pollarded oak forests during autumn, where they could feed on fallen acorns. The system formed the mainstay of pork production in Europe for centuries. [7] The “meadow orchard” or “grazed orchard” combined fruit cultivation and grazing — pollarded fruit trees offered shade to the animals, while the animals could not reach the fruit but fertilised the trees.

Forest or pasture? Something in between. A “dehesa” (pig forest farm) in Spain. Image by Basotxerri (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Cattle grazes among pollarded trees in Huelva, Spain. (CC BY-SA 2.5)

A meadow orchard surrounded by a living hedge in Rijkhoven, Belgium. Image: Geert Van der Linden.

While agriculture and forestry are now strictly separated activities, in earlier times the farm was the forest and vice versa. It would make a lot of sense to bring them back together, because agriculture and livestock production – not wood production – are the main drivers of deforestation. If trees provide animal fodder, meat and dairy production should not lead to deforestation. If crops can be grown in fields with trees, agriculture should not lead to deforestation. Forest farms would also improve animal welfare, soil fertility and erosion control.

Line Plantings

Extensive plantations could consist of coppiced or pollarded trees, and were often managed as a commons. However, coppicing and pollarding were not techniques seen only in large-scale forest management. Small woodlands in between fields or next to a rural house and managed by an individual household would be coppiced or pollarded. A lot of wood was also grown as line plantings around farmyards, fields and meadows, near buildings, and along paths, roads and waterways. Here, lopped trees and shrubs could also appear in the form of hedgerows, thickly planted hedges. [8]

Hedge landscape in Normandy, France, around 1940. Image: W Wolny, public domain.

Line plantings in Flanders, Belgium. Detail from the Ferraris map, 1771-78.

Although line plantings are usually associated with the use of hedgerows in England, they were common in large parts of Europe. In 1804, English historian Abbé Mann expressed his surprise when he wrote about his trip to Flanders (today part of Belgium): “All fields are enclosed with hedges, and thick set with trees, insomuch that the whole face of the country, seen from a little height, seems one continued wood”. Typical for the region was the large number of pollarded trees. [8]

Like coppice forests, line plantings were diverse and provided people with firewood, construction materials and leaf fodder. However, unlike coppice forests, they had extra functions because of their specific location. [9] One of these was plot separation: keeping farm animals in, and keeping wild animals or cattle grazing on common lands out. Various techniques existed to make hedgerows impenetrable, even for small animals such as rabbits. Around meadows, hedgerows or rows of very closely planted pollarded trees (“pollarded tree hedges”) could stop large animals such as cows. If willow wicker was braided between them, such a line planting could also keep small animals out. [8]

Detail of a yew hedge. Image: Geert Van der Linden.

Hedgerow. Image: Geert Van der Linden.

Pollarded tree hedge in Nieuwekerken, Belgium. Image: Geert Van der Linden.

Coppice stools in a pasture. Image: Jan Bastiaens.

Trees and line plantings also offered protection against the weather. Line plantings protected fields, orchards and vegetable gardens against the wind, which could erode the soil and damage the crops. In warmer climates, trees could shield crops from the sun and fertilize the soil. Pollarded lime trees, which have very dense foliage, were often planted right next to wattle-and-daub buildings in order to protect them from wind, rain and sun. [10]

Dunghills were protected by one or more trees, preventing the valuable resource from evaporating due to sun or wind. In the yard of a watermill, the wooden water wheel was shielded by a tree to prevent the wood from shrinking or expanding in times of drought or inactivity. [8]

A pollarded tree protects a water wheel. Image: Geert Van der Linden.

Pollarded lime trees protect a farm building in Nederbrakel, Belgium. Image: Geert Van der Linden.

Location Matters

Along paths, roads and waterways, line plantings had many of the same location-specific functions as on farms. Cattle and pigs were hoarded over dedicated droveways lined with hedgerows, coppices and/or pollards. When the railroads appeared, line plantings prevented collisions with animals. They protected road travellers from the weather, and marked the route so that people and animals would not get off the road in a snowy landscape. They prevented soil erosion at riverbanks and hollow roads.

All functions of line plantings could be managed by dead wood fences, which can be moved more easily than hedgerows, take up less space, don’t compete for light and food with crops, and can be ready in a short time. [11] However, in times and places were wood was scarce a living hedge was often preferred (and sometimes obliged) because it was a continuous wood producer, while a dead wood fence was a continuous wood consumer. A dead wood fence may save space and time on the spot, but it implies that the wood for its construction and maintenance is grown and harvested elsewhere in the surroundings.

Image: Pollarded tree hedge in Belgium. Image: Geert Van der Linden.

Local use of wood resources was maximised. For example, the tree that was planted next to the waterwheel, was not just any tree. It was red dogwood or elm, the wood that was best suited for constructing the interior gearwork of the mill. When a new part was needed for repairs, the wood could be harvested right next to the mill. Likewise, line plantings along dirt roads were used for the maintenance of those roads. The shoots were tied together in bundles and used as a foundation or to fill up holes. Because the trees were coppiced or pollarded and not cut down, no function was ever at the expense of another.

Nowadays, when people advocate for the planting of trees, targets are set in terms of forested area or the number of trees, and little attention is given to their location – which could even be on the other side of the world. However, as these examples show, planting trees closeby and in the right location can significantly optimise their potential.

Shaped by Limits

Coppicing has largely disappeared in industrial societies, although pollarded trees can still be found along streets and in parks. Their prunings, which once sustained entire communities, are now considered waste products. If it worked so well, why was coppicing abandoned as a source of energy, materials and food? The answer is short: fossil fuels. Our forebears relied on coppice because they had no access to fossil fuels, and we don’t rely on coppice because we have.

Our forebears relied on coppice because they had no access to fossil fuels, and we don’t rely on coppice because we have

Most obviously, fossil fuels have replaced wood as a source of energy and materials. Coal, gas and oil took the place of firewood for cooking, space heating, water heating and industrial processes based on thermal energy. Metal, concrete and brick – materials that had been around for many centuries – only became widespread alternatives to wood after they could be made with fossil fuels, which also brought us plastics. Artificial fertilizers – products of fossil fuels – boosted the supply and the global trade of animal fodder, making leaf fodder obsolete. The mechanisation of agriculture – driven by fossil fuels – led to farming on much larger plots along with the elimination of trees and line plantings on farms.

Less obvious, but at least as important, is that fossil fuels have transformed forestry itself. Nowadays, the harvesting, processing and transporting of wood is heavily supported by the use of fossil fuels, while in earlier times they were entirely based on human and animal power – which themselves get their fuel from biomass. It was the limitations of these power sources that created and shaped coppice management all over the world.

Harvesting wood from pollarded trees in Belgium, 1947. Credit: Zeylemaker, Co., Nationaal Archief (CCO)

Transporting firewood in the Basque Country. Source: Notes on pollards: best practices’ guide for pollarding. Gipuzkoaka Foru Aldundía-Diputación Foral de Giuzkoa, 2014.

Wood was harvested and processed by hand, using simple tools such as knives, machetes, billhooks, axes and (later) saws. Because the labour requirements of harvesting trees by hand increase with stem diameter, it was cheaper and more convenient to harvest many small branches instead of cutting down a few large trees. Furthermore, there was no need to split coppiced wood after it was harvested. Shoots were cut to a length of around one metre, and tied together in “faggots”, which were an easy size to handle manually.

It was the limitations of human and animal power that created and shaped coppice management all over the world

To transport firewood, our forebears relied on animal drawn carts over often very bad roads. This meant that, unless it could be transported over water, firewood had to be harvested within a radius of at most 15-30 km from the place where it was used. [12] Beyond those distances, the animal power required for transporting the firewood was larger than its energy content, and it would have made more sense to grow firewood on the pasture that fed the draft animal. [13] There were some exceptions to this rule. Some industrial activities, like iron and potash production, could be moved to more distant forests – transporting iron or potash was more economical than transporting the firewood required for their production. However, in general, coppice forests (and of course also line plantings) were located in the immediate vicinity of the settlement where the wood was used.

In short, coppicing appeared in a context of limits. Because of its faster growth and versatile use of space, it maximised the local wood supply of a given area. Because of its use of small branches, it made manual harvesting and transporting as economical and convenient as possible.

Can Coppicing be Mechanised?

From the twentieth century onwards, harvesting was done by motor saw, and since the 1980s, wood is increasingly harvested by powerful vehicles that can fell entire trees and cut them on the spot in a matter of minutes. Fossil fuels have also brought better transportation infrastructures, which have unlocked wood reserves that were inaccessible in earlier times. Consequently, firewood can now be grown on one side of the planet and consumed at the other.

The use of fossil fuels adds carbon emissions to what used to be a completely carbon neutral activity, but much more important is that it has pushed wood production to a larger – unsustainable – scale. [14] Fossil fueled transportation has destroyed the connection between supply and demand that governed local forestry. If the wood supply is limited, a community has no other choice than to make sure that the wood harvest rate and the wood renewal rate are in balance. Otherwise, it risks running out of fuelwood, craft wood and animal fodder, and it would be abandoned.

Mechanically harvested willow coppice plantation. Shortly after coppicing (right), 3-years old growth (left). Image: Lignovis GmbH (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Likewise, fully mechanised harvesting has pushed forestry to a scale that is incompatible with sustainable forest management. Our forebears did not cut down large trees for firewood, because it was not economical. Today, the forest industry does exactly that because mechanisation makes it the most profitable thing to do. Compared to industrial forestry, where one worker can harvest up to 60 m3 of wood per hour, coppicing is extremely labour-intensive. Consequently, it cannot compete in an economic system that fosters the replacement of human labour with machines powered by fossil fuels.

Coppicing cannot compete in an economic system that fosters the replacement of human labour with machines powered by fossil fuels

Some scientists and engineers have tried to solve this by demonstrating coppice harvesting machines. [15] However, mechanisation is a slippery slope. The machines are only practical and economical on somewhat larger tracts of woodland (>1 ha) which contain coppiced trees of the same species and the same age, with only one purpose (often fuelwood for power generation). As we have seen, this excludes many older forms of coppice management, such as the use of multipurpose trees and line plantings. Add fossil fueled transportation to the mix, and the result is a type of industrial coppice management that brings few improvements.

Coppiced trees along a brook in ‘s Gravenvoeren, Belgium. Image: Geert Van der Linden.

Sustainable forest management is essentially local and manual. This doesn’t mean that we need to copy the past to make biomass energy sustainable again. For example, the radius of the wood supply could be increased by low energy transport options, such as cargo bikes and aerial ropeways, which are much more efficient than horse or ox drawn carts over bad roads, and which could be operated without fossil fuels. Hand tools have also improved in terms of efficiency and ergonomics. We could even use motor saws that run on biofuels – a much more realistic application than their use in car engines. [16]

The Past Lives On

This article has compared industrial biomass production with historical forms of forest management in Europe, but in fact there was no need to look to the past for inspiration. The 40% of the global population consisting of people in poor societies that still burn wood for cooking and water and/or space heating, are no clients of industrial forestry. Instead, they obtain firewood in much of the same ways that we did in earlier times, although the tree species and the environmental conditions can be very different. [17]

A 2017 study calculated that the wood consumption by people in “developing” societies – good for 55% of the global wood harvest and 9-15% of total global energy consumption – only causes 2-8% of anthropogenic climate impacts. [18] Why so little? Because around two-thirds of the wood that is harvested in developing societies is harvested sustainably, write the scientists. People collect mainly dead wood, they grow a lot of wood outside the forest, they coppice and pollard trees, and they prefer the use of multipurpose trees, which are too valuable to cut down. The motives are the same as those of our ancestors: people have no access to fossil fuels and are thus tied to a local wood supply, which needs to be harvested and transported manually.

African women carrying firewood. (CC BY-SA 4.0)

These numbers confirm that it is not biomass energy that’s unsustainable. If the whole of humanity would live as the 40% that still burns biomass regularly, climate change would not be an issue. What is really unsustainable is a high energy lifestyle. We can obviously not sustain a high-tech industrial society on coppice forests and line plantings alone. But the same is true for any other energy source, including uranium and fossil fuels.

Written by Kris De Decker. Proofread by Alice Essam.

* Subscribe to our newsletter.

* Support Low-tech Magazine via Paypal or Patreon.

* Buy the printed website.

References:

[1] Multiple references:

Unrau, Alicia, et al. Coppice forests in Europe. University of Freiburg, 2018.

Notes on pollards: best practices’ guide for pollarding. Gipuzkoako Foru Aldundia-Diputación Foral de Gipuzkoa, 2014.

A study of practical pollarding techniques in Northern Europe. Report of a three month study tour August to November 2003, Helen J. Read.

Aarden wallen in Europa, in “Tot hier en niet verder: historische wallen in het Nederlandse landschap”, Henk Baas, Bert Groenewoudt, Pim Jungerius and Hans Renes, Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed, 2012.

[6] While leaf fodder was used all over Europe, it was especially widespread in mountainous regions, such as Scandinavia, the Alps and the Pyrenees. For example, in Sweden in 1850, 1.3 million sheep and goats consumed a total of 190 million sheaves annually, for which at least 1 million hectares deciduous woodland was exploited, often in the form of pollards. The harvest of leaf fodder predates the use of hay as winter fodder. Branches could be cut with stone tools, while cutting grass requires bronze or iron tools. While most coppicing and pollarding was done in winter, harvesting leaf fodder logically happened in summer. Bundles of leaf fodder were often put in the pollarded trees to dry. References:Logan, William Bryant. Sprout lands: tending the endless gift of trees. WW Norton & Company, 2019.

A study of practical pollarding techniques in Northern Europe. Report of a three month study tour August to November 2003, Helen J. Read.

Slotte H., “Harvesting of leaf hay shaped the Swedish landscape“, Landscape Ecology 16.8 (2001): 691-702.

[8] This information is based on several Dutch language publications:Handleiding voor het inventariseren van houten beplantingen met erfgoedwaarde. Geert Van der Linden, Nele Vanmaele, Koen Smets en Annelies Schepens, Agentschap Onroerend Erfgoed, 2020.

Handleiding voor het beheer van hagen en houtkanten met erfgoedwaarde. Thomas Van Driessche, Agentschap Onroerend Erfgoed, 2019

Knotbomen, knoestige knapen: een praktische gids. Geert Van der Linden, Jos Schenk, Bert Geeraerts, Provincie Vlaams-Brabant, 2017.

Handleiding: Het beheer van historische dreven en wegbeplantingen. Thomas Van Driessche, Paul Van den Bremt and Koen Smets. Agentschap Onroerend Erfgoed, 2017.

Dirkmaat, Jaap. Nederland weer mooi: op weg naar een natuurlijk en idyllisch landschap. ANWB Media-Boeken & Gidsen, 2006.

For a good source in English, see: Müller, Georg. Europe’s Field Boundaries: Hedged banks, hedgerows, field walls (stone walls, dry stone walls), dead brushwood hedges, bent hedges, woven hedges, wattle fences and traditional wooden fences. Neuer Kunstverlag, 2013.

If line plantings were mainly used for wood production, they were planted at some distance from each other, allowing more light and thus a higher wood production. If they were mainly used as plot boundaries, they were planted more closely together. This diminished the wood harvest but allowed for a thicker growth.

[9] In fact, coppice forests could also have a location-specific function: they could be placed around a city or settlement to form an impenetrable obstacle for attackers, either by foot or by horse. They could not easily be destroyed by shooting, in contrast to a wall. Source: [5]

[10] Lime trees were even used for fire prevention. They were planted right next to the baking house in order to stop the spread of sparks to wood piles, haystacks and thatched roofs. Source: [5]

[11] The fact that living hedges and trees are harder to move than dead wood fences and posts also has practical advantages. In Europe until the French era, there was no land register and boundaries where physically indicated in the landscape. The surveyor’s work was sealed with the planting of a tree, which is much harder to move on the sly than a pole or a fence. Source: [5]

[12] And, if it could be brought in over water from longer distances, the wood had to be harvested within 15-30 km of the river or coast.

[16] However, chainsaws can have adverse effects on some tree species, such as reduced growth or greater ability to transfer disease.

[17] Multiple sources that refer to traditional forestry practices in Africa:

Leach, Gerald, and Robin Mearns. Beyond the woodfuel crisis: people, land and trees in Africa. Earthscan, 1988.

Leach, Melissa, and Robin Mearns. “The lie of the land: challenging received wisdom on the African environment.” (1998)

Cline-Cole, Reginald A. “Political economy, fuelwood relations, and vegetation conservation: Kasar Kano, Northerm Nigeria, 1850-1915.” Forest & Conservation History 38.2 (1994): 67-78.

by DGR News Service | Jun 4, 2020 | ANALYSIS, Human Supremacy

Grassroots activist Suzanna Jones observes how even long-time environmentalists can become misled.

Faulty: Bill McKibben’s Crisis Logic

By Suzanna Jones

Vermont has a reputation for producing sturdy New England farm folk – hardscrabble people who lived full lives in challenging conditions. Our neighbors, Frank and Virginia, were prime examples. Living well into their eighties, they never owned a car or a phone, and never went on a vacation; they saved and reused everything, and grew their own food. Despite – or probably because of – the simplicity of their lives, they were happy.

Now there is a different kind of folk in the Green Mountain landscape. You’ll find them rushing to the airport in their hybrid car, smartphone glued to their hands, trying to catch a plane for their vacation abroad. Often well-meaning and ‘progressive’, they tend to look down on people like Frank and Virginia for not being ‘green’ enough. The reality, of course, is that these self-described environmentalists have a far greater impact on the Earth than those older Vermonters did.

Mainstream notions of monetary and career ‘success’ lead us to dismiss simpler ways of life. Unfortunately, this leaves us utterly wedded to the economic system that lies behind all our environmental problems, including climate change.

Crisis Logic

Bill McKibben‘s recent appearance in Hardwick to promote his new book, Falter, got me thinking about this. Back in 2008 McKibben correctly identified our growth-obsessed economy as the source of the ecological collapse we face today, explaining that when the economy grows larger than necessary to meet our basic needs, its social and environmental costs outweigh any benefits.

He pointed out that our consumerist way of life – in which we strive for more no matter how much we already have – is one of the ways corporations keep our bloated economy growing. The irony, he added, is that perennial accumulation does not even make us happy. But now, sadly, McKibben studiously avoids criticizing the very economy he once fingered as the source of our environmental crisis.

During his talk he referred to Exxon’s ‘big lie’: the company knew about climate change long ago but hid the truth. Ironically, McKibben’s presentation did something similar by hiding the fact that his only ‘solution’ to climate change – the rapid transition from fossil fuels to industrial renewables – actually causes astounding environmental damage.

Out of the Back Comes Modernity

Solar power, he said, is “just glass angled at the sun, and out the back comes ‘modernity’.” But solar is much more than just glass. One example? Like wind power, it requires the environmentally devastating – and fossil-fuel based – mining of rare earth metals. And that ‘modernity’ coming out the back? That is the lifestyle that is killing the planet.

McKibben extolled the virtues of Green Mountain Power’s industrial ‘renewable’ developments, failing to mention that GMP sells the Renewable Energy Credits (RECs) from those projects to out-of-state utilities, thereby subsidizing the production of dirty energy elsewhere. He also neglected to say that one of GMP’s parent companies is tar sands giant Enbridge, which owns a $1.5 billion stake in the Dakota Access Pipeline and is currently working to use Vermont as a corridor for future fracked-gas transport.

Therein Lies the Deception

McKibben once claimed that “every turn of the blade” of an industrial wind turbine “reduces fossil fuel consumption somewhere.” When the RECs are sold, however, this is simply untrue. And while the production and installation of every turbine has serious environmental costs, every reduction in consumption really does reduce fossil fuel use somewhere, while simultaneously reducing environmental impacts.

Renewables only make sense in tandem with drastic reductions in energy consumption, and are best implemented through small-scale, grid-free efforts. But what we have instead is corporations continuing to market the psychotic American dream – powered by ‘renewables’! This co-opted response to climate change is no longer about protecting nature from the ever expanding human nightmare, it is about sustaining the comforts and luxuries we feel entitled to. It is business-as-usual disguised as concern for the Earth. It is utterly empty, but it serves the destructive economy.

Though not Mckibben’s intent, this is what he implicitly supports.

Changing the Fuel Does Not Stop Ecocide

Climate change is a crisis, but it is only one of many ways the planet is being destroyed. Changing the fuel that runs the system that is killing the planet is not a solution. An effective response would resemble shifting towards the way Frank and Virginia lived. It won’t look ‘cool’, or stroke the attention-seeking narcissism of social media addicts, but it would have immediate benefits.

That shift will require a major rethinking of our lives and economy; it asks us to have the maturity, courage, humility and wisdom to put nature and her needs first. McKibben deserves credit for sounding the alarm about climate change early on, but now he should tell people the unvarnished truth: that if we cannot sacrifice our comforts, luxuries and rapid mobility because we love this Earth, then there really is no hope.

Suzanna Jones lives off grid on a small farm in Northern Vermont. She has been fighting injustice, destruction of the land, and industrial wind projects for decades and has been arrested several times.

Featured image by Hotshot977, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. To repost this or any other content on this website, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org.