by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jun 19, 2016 | Prostitution

By Cherry Smiley / Feminist Current

The full decriminalization of prostitution has received considerable mainstream media attention of late: On May 5, the New York Times published an article by Emily Bazelon called, “Should Prostitution be a Crime?” and on May 26, Amnesty International formally adopted a position in favour of the total decriminalization of prostitution.

Neither Bazelon’s article nor Amnesty International’s “sex work” policy take into meaningful account the ways in which prostitution functions as a system of colonialism that disproportionately targets Indigenous women and girls. Through these policies and positions, prostitution is sanitized and whitewashed into “sex work,” leaving Indigenous women and girls and our sisters of colour to deal with the consequences.

Today, as the result of the sustained work of Indigenous women and men, increasing numbers of individuals and organizations are beginning to recognize the importance of land to the survival, cultures, and well-being of Indigenous Peoples and the ways in which colonialism violently disrupts these relationships. Slowly, non-Indigenous people are beginning to understand the concept of “unceded territories” and acknowledge the exploitation of lands and “resources” that were forcibly removed from the care of Indigenous Peoples.

Male colonizers were thieves who took what wasn’t theirs because they believed they were entitled to it. But this entitlement didn’t stop at lands — these men decided they were also entitled to the bodies of Indigenous women and girls. According to research done by Melissa Farley, Jacqueline Lynne, and Ann Cotton, Indigenous women and girls in Canada were prostituted through early forts and military bases, and as “country wives” of white fur traders. Indigenous women and girls were targeted for prostitution in part because of lies told about them: they were “squaws” and “savages” who always wanted sex with white men. Prior to the invasion of North America, prostitution didn’t exist among the Indigenous Nations I have encountered — rather, prostitution was imposed on Indigenous women and girls by male colonizers. Entitlement to land continues today as non-Indigenous people live on and exploit Indigenous lands for profit, and entitlement to bodies continues in crisis levels of male violence against Indigenous women and girls.

In her article, Bazelon quotes Liesl Gerntholtz, Executive Director of the Women’s Rights Division at Human Rights Watch (HRW), another organization that has taken a position supporting the total decriminalization of prostitution:

“You’re often talking about women who have extremely limited choices. Would I like to live in a world where no one has to do sex work? Absolutely. But that’s not the case. So I want to live in a world where women do it largely voluntarily, in a way that is safe.”

Gerntholtz and HRW have apparently concluded that it is impossible to imagine a world without prostitution and, in doing so, disregard Indigenous histories and send the message to Indigenous women and girls that we are not worth fighting for. In taking this position, HRW reaffirms the racist myth that Indigenous women and girls (and women of colour) are disproportionately consenting to engage in prostitution because they so desire sex with white men. If we don’t recognize and fight back against the racist, sexist, and capitalist inequalities that funnel women and girls into prostitution and fight back against male entitlement, our only answer to the overrepresentation of Indigenous women and girls in the sex industry becomes: “Because they are ‘squaws’ who desire sex with strangers in disproportionate numbers to white women.” Is this the lie we want to continue to tell to Indigenous women and girls and the message we want to send to the men who buy and sell them?

Unfortunately, Bazelon and HRW can’t (or won’t) challenge male entitlement. Instead, women and girls are told they simply need to find better and “safer” ways to accommodate unchallenged male entitlement to our bodies.

The messages I received from the time I was a girl were meant to keep me “safer”: don’t talk to strangers, don’t walk alone at night, don’t wear short skirts. This messaging (always directed at girls and women) aims to constrain our movements and actions in the name of “safety.” Where is the messaging to boys and men not to rape? Where is the messenging that tells men and boys that they are not entitled to sex whenever, however, and with whoever they want? Where is the challenge to male entitlement to bodies and lands?

We see examples of male entitlement everywhere. The recent case of the Stanford rapist, Brock Turner, is a perfect example. His actions, as well as the light sentence, defence, minimization, and disbelief of Turner’s actions by his father and others, is an example of rape culture: a culture that allows, condones, and even celebrates the rape of women and girls by men. This culture affects all women and girls, but Indigenous women and women of colour in particular ways, leading one to question whether Turner would have even been charged or convicted had his victim been Indigenous or a woman of colour.

Watching these cases, Indigenous women and women of colour see that even a woman with white privilege received a horrific response to her sexual assault, leading us to ask, “If this happened to a woman with a relative level of privilege, what will happen to us?” Regardless of the race of the victim, what all women live through as victims of sexual assault and the ways our lives are constrained by male violence (or the threat of male violence) is a direct result of the patriarchal culture we live in.

Turner raped a woman because he felt entitled to her body. Male entitlement is a foundation of rape culture, yet many who claim to criticize rape culture simultaneously support the decriminalization of pimps and johns, thereby failing to recognize that the very same male entitlement that supports rape culture also fuels the sex industry.

Amnesty says their new policy, “does not argue that there is a human right to buy sex or a human right to financially benefit from the sale of sex by another person.” What the organization doesn’t seem to realize is that, without consequences for the actions of pimps and johns, their policy green-lights and condones those actions. Amnesty International’s policy naturalizes male entitlement to bodies (and lands) by refusing to acknowledge it as part of the foundation of patriarchy, racism, and capitalism and by refusing to challenge it accordingly.

To be clear, I am critiquing the system of prostitution, not the women and girls who are in prostitution. In the same way, I critique Canada’s horrific residential school system without criticizing residential school survivors and critique rape culture without blaming women and girls who have been raped. There is no shame in engaging in prostitution; Indigenous women and girls have been targeted for prostitution since the invasion of Canada by white men. The fact that Indigenous women and girls survive at all in a genocidal culture that hates us and hates all women is nothing short of a victory. But we deserve more than just survival — we deserve fulfilling, joyful lives that are free from male violence or the threat of male violence. We deserve to engage in sexual acts of our choosing, with partners that we choose, who consider our humanity and pleasure, without any form of threat or coercion, economic or otherwise. All those who sell sex should of course be decriminalized and all women and girls should have access to the things we need to build those fulfilling, joyful lives, like safe and affordable housing, nutritious food and clean water, access to education and employment opportunities, and a recognition of our rights to our lands, languages, and cultures. I don’t judge those who find themselves selling sex, but I do judge the men who choose to pay for or profit from the sexual exploitation of women and girls — the vast majority of whom are poor, Indigenous, and of colour. In Canada today, girls are sexualized from a very young age and women still only earn 72 per cent of what men earn for similar work; let’s not pretend girls begin their lives on equal footing.

I’ve witnessed a lot of online praise for Bazelon’s article and Amnesty International’s new policy, and sadly, I’m unsurprised at this show of support. When the status quo (male entitlement) isn’t being challenged, celebration is to be expected. I’m sure many johns and pimps applauded Bazelon’s article and Amnesty’s new sex work policy.

A number of well-meaning individuals and organizations refer to reports by HRW and Amnesty International regarding violence against Indigenous women and girls in Canada as important research in regard to this issue. However, due to these organizations’ position on prostitution, it is obvious to me that neither has an understanding of colonialism and the consequences of this ongoing process on the lives of Indigenous women and girls. Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, and Bazelon fail to understand that, on a fundamental level, white male entitlement to bodies and lands is harmful and sometimes deadly, and that white male entitlement to bodies and lands must always be challenged. Prostitution is the colonization of bodies, and at its heart, is an expression of patriarchy, racism, and capitalism. This is about wealthy, white male domination and control.

I suggest that writers like Bazelon educate themselves further on colonialism and what it means before publishing further on these issues, and that HRW and Amnesty International refrain from commenting on any issue of male violence against Indigenous women and girls in Canada until they are willing to take a stand against male entitlement to women’s bodies and lands.

These positions and arguments are contradictory and cannot be reconciled to advocate for an end to violence against Indigenous women and girls on one hand, and for pimps and johns to buy and sell Indigenous women, without consequence, on the other. Indigenous women and girls don’t need “allies” that refuse to challenge colonialism in Canada and colonial ideologies within themselves.

Cherry Smiley is a feminist activist and artist from the Thompson and Navajo nations. She is a co-founder of Indigenous Women Against the Sex Industry and was the recipient of a 2013 Governor General’s Award in Commemoration of the Person’s Case and the 2014 winner of The Nora and Ted Sterling Prize in Support of Controversy. Follow her .

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jun 18, 2016 | Colonialism & Conquest

By Laura Hobson Herlihy / Cultural Survival

The Miskitu people (pop. 185,000) live in Muskitia, a rainforest region that stretches along the Central American Caribbean coast from Black River, Honduras to just south of Bluefields, Nicaragua. Two-thirds of Muskitia and the Miskitu people reside in Nicaragua. The Miskitu people in Nicaragua today are in a crisis situation. Armed mestizo colonists are attacking their communities, pillaging and confiscating their rainforest lands. This article is a cry for help.

The Miskitu people have legal ownership of their lands guaranteed by Nicaraguan Law 445, the ILO Convention 169, and the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People. Yet, mestizo colonists (called, colonos) from the interior and Pacific coast have invaded, and now illegally occupy, nearly half of their lands. In September 2015, violence over land conflicts erupted in the Miskitu territories of Wangki Twi-Tasba Raya and Li Aubra. These territories are located near the Coco or Wangki River, the international border between Nicaragua and Honduras.

Since September, mestizo colonists with automatic weapons have killed, injured, and kidnapped more than 80 Miskitu men with impunity. In fear for their lives, between 1-2,000 Miskitu refugees have fled to Waspam and Puerto Cabezas-Bilwi and Honduran border communities. The refugees–mainly women, children, and elders–are suffering from starvation and lack medical supplies. Children have not attended school for six months. Meanwhile, periodic attacks continue on Miskitu communities in Wangki Twi-Tasba Raya.

Much of the violence now occurring revolves around article 59 of the Communal Property Law (law 445). Article 59 requires the Nicaraguan state to complete saneamiento, the cleansing or the removal of colonists and industries from Indigenous and Afro-descendant territories. The current Nicaraguan government publically agreed to saneamiento but has not responded. Similarly, the government still has not provided protection to the Miskitu communities under attack or assistance to the refugees. As a result of the government’s delayed reaction to the crisis, the Miskitu people now suspect the Sandinista (FSLN) state to be complicit with the colonists’ invasion of their Indigenous territories.

In a separate but related issue, the FSLN government passed the Canal Law (Act 840) that approved the Chinese-backed (HKND) inter-oceanic canal to cut through the ancestral homeland of the Indigenous and Afro-descendant peoples along the Nicaraguan Caribbean coast. Tensions are rising over Indigenous territoriality and land rights, especially between the Miskitu people and President Daniel Ortega’s Sandinista government. The tense situation over land rights today bares eerie similarities to the war-torn years of the 1980s in Nicaragua, when Ortega first served as President (1985-1990) and the Miskitu fought as counter-revolutionary warriors in the Contra war within the Sandinista revolution (1979-1990).

As a US anthropologist who has worked for over twenty years with the Honduran and Nicaraguan Miskitu people, I had the opportunity to attend the 2016 United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (May 9-20). On Thursday, May 12, I recorded Miskitu leader Brooklyn Rivera’s intervention in the session, “Dialogue with Indigenous Peoples.” Rivera has served as the Líder Máximo (literally, Highest Leader) of the Nicaraguan Miskitu people for over 30 years; after rising to power as a military leader in the revolution and war, Rivera in 1987 founded and became the long-term director of the Indigenous organization Yatama (Yapti Tasba Masraka Nanih Aslatakanka/Sons of Mother Earth). Special thanks to Costa Rican anthropologist Fernando Montero (ABD, Columbia) for transcribing Rivera’s United Nations intervention in Spanish and translating it to the English below.

English Version

My name is Brooklyn Rivera. I am both a son and the highest leader of the Miskitu people of the Nicaraguan Muskitia. As we know, the rights of Indigenous peoples are essentially human rights. According to Article 1 of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Indigenous people have the right, both as peoples and as individuals, to the full enjoyment of their human rights and fundamental liberties. In my country of Nicaragua, the rights of Indigenous people have suffered severe setbacks in the last several years. Indeed, the current Sandinista government–contrary to its rhetoric in international forums and in flagrant violation of the rights of Indigenous peoples–freely acts against Indigenous peoples, advancing a consistent policy of aggression and internal colonialism.

Consider the following within the specific sphere of Indigenous peoples’ rights: the government imposes violence against our communities by means of settlers who invade ancestral territories, carrying out armed attacks, murders, kidnappings, rape, and displacement, producing refugees, most of whom are women, children, and people of old age. All this occurs in the face of governmental and institutional passivity, even complicity. Moreover, the Nicaraguan government is currently implementing a policy of militarization in our communities and fishing territories, committing murders such as that of our brother and leader Mario Lehman last September. In like manner, the government is overtly trampling on our communities’ right to ancestral autonomy by interfering with the election of their leaders according to their own practices and customs, devoting itself to destroying the structure and traditional procedures of our communities with the aim of replacing them with the so-called Sandinista Leadership Committees, part of their party structure. In this way they create and impose a spurious and noxious structure parallel to Indigenous authorities. You will understand that, by applying this policy, the government and the ruling party are fomenting division within families and communities, destroying their social fabric, cultural values and [imposing] heightened suffering and poverty. In addition, in open violation of the right to work, the Sandinista government denies jobs and government positions to Indigenous professionals and technicians, demanding that they become members of their party before considering them for these positions.

With regard to the sphere of the environment of our peoples in Nicaragua, I must first point out the dispossession of lands and territories suffered by Miskitu communities perpetrated by cattle ranchers, mining companies, and wealthy sectors linked to the government and the ruling party, who use settlers as spearheads. In this invasion, armed settlers arrive in our lands, advance the agricultural frontier, occupy extensions of territory, and destroy the habitats and ecosystems of Indigenous peoples, preying on their fauna, flora, and marine ecology. Needless to say, this extractivist policy involves the looting of ancestral communal resources such as forests, flora, mineral resources, water resources, and land itself with the illegal land sales in which settlers participate. I must also mention the promotion of megaprojects such as the interoceanic canal and the Tumarin hydroelectric dam in Awaltara, both of which violate Indigenous peoples’ right to prior, free, and informed consent. These megaprojects render entire communities vulnerable to disappearing along with their culture and language. This is the case of the Rama people, a small, vulnerable people in danger of extinction who reside in the Southern Moskitia. In the face of this crude reality and despite its demonstrated lack of political will and its disrespect for international laws and institutions—not to mention my own arbitrary, illegal expulsion from the National Parliament—once again we demand from the Nicaraguan government:

1. The immediate application of the recommendations issued last December by the UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, in reference to the cleansing [“saneamiento”] of Indigenous territories and the protection of our communities in the face of settler invasion;

2. The immediate enactment of the precautionary measures suggested by the OAS’ Human Rights Commission on behalf of the Indigenous communities in the regions of Tasba Raya and Wangki Li Auhbra (location in the municipality of Waspam), approved in October 2015 and expanded in January 2016;

3. The immediate launch of a process of genuine dialogue and negotiation with Indigenous peoples via their organizations and leaders to reach real solutions based on respect for Indigenous peoples and the recognition of their dignity, as outlined in existing frameworks;

4. Finally, the immediate restitution of the undersigned as legislator, in accordance with his status as a popularly elected official put in power thanks to the votes of Indigenous peoples, whose constitutional and legal rights were violated with my arbitrary and illegal expulsion from Parliament.

I end my intervention by asking all participants, especially the Indigenous peoples in this forum, to engage in active solidarity with the Indigenous peoples of Nicaragua and their organizations as they resist and demand dignity, rights, and justice from the Sandinista government in Nicaragua.

Thank you, Mr. President.

En Espanol

Soy Brooklyn Rivera, hijo del pueblo mískitu de la Mosquitia nicaragüense y su dirigente principal. Como sabemos, los derechos de los pueblos indígenas son esencialmente derechos humanos. Como se establece en el artículo 1 de la Declaración de la ONU sobre los Pueblos Indígenas, los indígenas tienen derecho como pueblos o como individuos al disfrute pleno de todos sus derechos humanos y las libertades fundamentales. El país de donde vengo yo, Nicaragua, en los últimos años ha experimentado un grave retroceso en el ejercicio de los derechos de nuestros pueblos indígenas, recogido en el marco legal interno y externo del país. En efecto, el actual gobierno sandinista, contrario a su retórica en los foros internacionales y en abierta violación de los derechos de los pueblos indígenas reconocidos en la Constitución Política y en las demás leyes y los instrumentos internacionales suscritos, se dedica a actuar libremente en su contra impulsando toda una política de agresión y colonialismo interno.

Veamos: en el ámbito específico de los derechos humanos de nuestros pueblos indígenas, a través de los colonos invasores de los territorios ancestrales, impone una situación de violencia en contra de nuestras comunidades mediante ataques armados, cometiendo asesinatos, secuestros, violaciones y desplazamentos, produciendo refugiados, mayormente niños, mujeres y ancianos. Todo esto ocurre ante la pasividad y aun la complicidad del gobierno y sus instituciones. Más aún, el gobierno nicaragüense implementa una política de militarización de las comunidades y las áreas de pesca, en las que cometen asesinatos como en el caso del crimen del hermano dirigente Mario Lehman ocurrido en el mes de septiembre pasado. De la misma forma, el gobierno aplica un abierto atropello al derecho de autonomía ancestral de nuestras comunidades en la elección de sus autoridades basada en los usos y costumbres, cuando a través de sus turbas partidarias y con el acompañamiento de sus policías y hasta de militares, aún así sin el mínimo respeto a las leyes y formas organizativas propias, se empecina en destruir la estructura y los procedimientos tradicionales de nuestras comunidades con el fin de sustituirlos con los llamados Comités de Liderazgo Sandinista, una estructura de su partido en el poder, creando e imponiendo así una estructura espuria y nociva, paralela a las autoridades indígenas. Como comprenderán, aplicando esta política el gobierno y su partido crean división entre las familias y comunidades, destruyendo sus tejidos sociales, valores culturales y mayor sufrimiento y pobreza. Además, el gobierno sandinista en abierta discriminación al derecho al trabajo, niega a los profesionales y técnicos de los pueblos indígenas el derecho al trabajo cuando exige que debe convertir a ser miembro de su partido para ocupar cargos o empleo en el país.

En relación al ámbito del medio ambiente de nuestros pueblos en Nicaragua, debo iniciar señalando el despojo de las tierras y territorios que sufren las comunidades en la Mosquitia de parte de los terratenientes ganaderos, empresas mineras y grupos adinerados vinculados al gobierno y a su partido, utilizando a los colonos como punta de lanza. En la invasión, los colonos armados llegan a nuestras tierras, aplican un avance agropecuario, ocupan extensiones de territorio y destruyen los hábitats y los ecosistemas de los pueblos indígenas, cometiendo depredaciones ambientales en su fauna, flora y entorno marino. Lógicamente, con esta política extractivista pasa por el saqueo de los bienes comunales ancestrales tales como los bosques, la flora, los recursos mineros, los recursos hídricos y la misma tierra con el tráfico ilegal de parte de los colonos. También aquí debo mencionar el impulso de los megaproyectos tales como el canal interocéanico y el hidroeléctrico Tumarín en Awaltara, en ambos casos violentando el derecho al consentimiento previo, libre e informado de los pueblos, impulsan sus megaproyectos en los que exponen la desaparición de comunidades enteras junto con su cultura y su idioma. Tal es el caso del pueblo Rama, pueblo pequeño, vulnerable y en proceso de extinción, ubicado en la Mosquitia Sur. Ante esta cruda realidad y a pesar de su falta de voluntad política demostrada y de su irrespeto a las leyes y las instituciones internacionales, así como de mi expulsión arbitrario e ilegal del Parlamento Nacional, como un esfuerzo de solución al conflicto impuesto, una vez más exigimos al gobierno nicaragüense:

- La inmediata aplicación de las recomendaciones de la Relatora Especial de las Naciones Unidas sobre los Derechos de los Pueblos Indígenas, emitidas en el mes de diciembre pasado, referentes al cumplimiento de la etapa de saneamiento de los territorios y de la protección de nuestras comunidades ante la invasión de los colonos;

- El inmediato cumplimiento de las medidas cautelares presentadas de parte de la Comisión de Derechos Humanos de la OEA a favor de las comunidades indígenas de la zona de Tasba Raya y de Wangki Li Auhbra en el municipio de Waspam, y abrobadas en el mes de octubre 2015 y ampliadas en enero de 2016;

- La inmediata apertura de un proceso genuino de diálogo y negociaciones con los pueblos indígenas a través de sus organizaciones y líderes que conduzcan a unas soluciones reales basadas en el respeto y el reconocimiento de la dignidad y los derechos de nuestros pueblos reconocidos en las normativas;

- Finalmente, la restitución inmediata del suscrito como legislador electo popularmente con los votos de sus pueblos indígenas, violentando mis derechos constitucionales y legales con el despojo arbitrario e ilegal cometido durante mi expulsión del Parlamento.

Termino mi intervención requiriendo a todas y todos los participantes, mayormente a los pueblos indígenas de este foro, una solidaridad activa con los pueblos indígenas y sus organizaciones en Nicaragua en el marco de su resistencia y demanda de dignidad, derecho y justicia ante el gobierno sandinista en Nicaragua.

Gracias, Presidente.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 18, 2016 | Alienation & Mental Health, Indigenous Autonomy

Featured image: An indigenous youth from Kwalikum First Nation sings. Photo: VIUDeepBay @flickr. Some Rights Reserved.

By Courtney Parker and John Ahni Schertow / Intercontinental Cry

The spiraling rate of suicide among Canada’s First Nations became a state of crisis in Attawapiskat this week after 11 people in the northern Ontario community attempted to take their own lives in one night.

The First Nation was so completely overwhelmed by the spike in suicide attempts that leaders declared a state of emergency. Crisis teams were soon deployed by various agencies to help the community cope with the horror. Meanwhile, as news coverage of the shocking situation spread, activists occupied the Toronto office of Indigenous and Northern Affairs to demand the federal government provide immediate and long-term support to properly address the situation in Attawapiskat.

At least 100 people from the small Cree community have attempted suicide since September. This alarming number—5 per cent of Attawapiskat’s population—is symptomatic of a larger and more pervasive problem in Canada.

While cancer and heart disease are the leading causes of death for the average Canadian, for First Nations youth and adults up to 44 years of age the leading cause of death is suicide and self-inflicted injuries.

According to Health Canada, the suicide rate for First Nations male youth (age 15-24) is 126 per 100,000 compared to 24 per 100,000 for non-indigenous male youth. For First Nations women, the suicide rate is 35 per 100,000 compared to 5 per 100,000 for non-indigenous women.

Handling this situation through a lens of crisis management simply will not do.

In order to bring an end to this long-standing crisis, there are systemic, cyclical and multi-generational issues that must first be addressed, with special attention given to ongoing disruptions in individual and cultural identity.

Historical impacts of colonization, compounded by Canada’s ongoing policies of forced assimilation, are pulling today’s First Nation youth further and further away from their core cultural identities. These identities and cultures have the power to protect and sustain all First Nation youth, and provide them with the resilience they need to overcome whatever individual factors may place them at risk for suicide.

Noting that the Pimicikamak Cree Nation in central Manitoba also responded to the epidemic by declaring their own state of emergency in March, national chief of the Assembly of First Nations, Perry Bellegarde recently proclaimed:

“We need a sustained commitment to address longstanding issues that lead to hopelessness among our peoples, particularly the youth.”

Bellegarde further lamented the lack of specially trained community health workers. He also cited Attawapiskat First Nation’s need for a mental health worker, a youth worker, and proper fiscal support to train workers in the community to respond.

Mainstream media has its own role to play.

Research has shown that merely talking about the devastating indigenous suicide epidemic can have unspeakably damaging consequences.

In 2007, a Canadian research team compiled a comprehensive report entitled, “Suicide Among Aboriginal People in Canada.” The text goes into great detail about how the media should—and should not—handle this extremely delicate subject matter.

“Mass media—in the form of television, Internet, magazines, and music—play an important role in the lives of most contemporary young people. Mass media may influence the rate and pattern of suicide in the general population (Pirkis and Blood, 2001; Stack, 2003; 2005). The media representation of suicides may contribute to suicide clusters. Suicide commands public and government attention and is often perceived as a powerful issue to use in political debates. This focus, however, can inadvertently legitimize suicide as a form of political protest and thus increase its prevalence. Research has shown that reports on youth suicide in newspapers or entertainment media have been associated with increased levels of suicidal behaviour among exposed persons (Phillips and Cartensen, 1986; Phillips, Lesyna,and Paight, 1992; Pirkis and Blood, 2001). The intensity of this effect may depend on how strongly vulnerable individuals identify with the suicides portrayed.

Phillips and colleagues (1992) offer explicit recommendations on the media handling of suicides to reduce this contagion effect. The emphasis is on limiting the degree of coverage of suicides, avoiding romanticizing the action, and presenting alternatives. There is some evidence that this may actually reduce suicides that follow in the wake of media reporting (Stack, 2003). Many Canadian newspaper editors have adopted policies to minimize the reporting of suicide to reduce their negative impact (Pell and Watters, 1982). Suicide prevention materials can also be disseminated through the media. The media can also contribute to mental health promotion more broadly by presenting positive images of Aboriginal cultures and examples of successful coping and community development.”

Even greater than the need for more socially responsible media, is the need for more proactive and community-specific solutions on the ground.

There is a growing body of evidence demonstrating the value of taking protective measures to prevent suicide by preserving and promoting the regular use of traditional indigenous languages.

In 2008, researchers Chandler and Lalonde published a report entitled, “Cultural Continuity as a Protective Factor Against Suicide in First Nations Youth.” In their review, they touched on an inherent risk in raising the conversation on the indigenous suicide epidemic to the international level – though it is particularly severe in Canada, it is indeed global – describing how it may obstruct community-based and community-specific solutions from emerging. Findings also confirmed that individual and community markers of cultural continuity – such as language retention – can form a protective barrier against the staggering incidence rates of suicide ravaging First Nations like Attawapiskat and the Pimicikamak Cree Nation.

Chandler and Lalonde conclude that:

“First Nations communities that succeed in taking steps to preserve their heritage culture, and that work to control their own destinies, are dramatically more successful in insulating their youth against the risks of suicide.”

In 1998, the same research team—Chandler and Lalonde—published a preliminary report detailing some of the most salient markers of cultural continuity among First Nations. Noted protective factors included: land claims; self-governance; autonomy in education; autonomy in police and fire services; autonomy in health services; and the presence of cultural facilities.

Interestingly, indigenous self-governance was discovered to be the strongest protective factor of all. Lower levels of suicide rates were also measured in communities exhibiting greater control over education, and in communities engaged in collective struggles for land rights—or, as they often call it Latin America: ‘La Lucha’!

In 2009, another research team that included Art Napoleon, Cree language speaker, language and culture preservationist and faith-keeper, issued a call for more research on the association between native language retention and reduced rates of indigenous youth suicide. They also called for more inter-tribal dialogues and community based, culturally tailored, strategy building. Their report detailed a host of other significant protective factors such as: honoring the connection between land and health; recognizing traditional medicine; spirituality as a protective factor; maintaining traditional foods; and, maintaining traditional activities.

Yet, perhaps the most compelling evidence to date connecting cultural continuity—and specifically, language retention—with reductions in First Nation suicide rates came in 2007, from research team, Hallett, Chandler and Lalonde. Their analyses demonstrated that rates of language retention among First Nations had the strongest predictive power over youth suicide rates, even when held amongst other influential constructs of cultural continuity. Their conclusions hold shocking implications about the dire importance of native language preservation and retention efforts and interventions.

“The data reported above indicate that, at least in the case of BC, those bands in which a majority of members reported a conversational knowledge of an Aboriginal language also experienced low to absent youth suicide rates. By contrast, those bands in which less than half of the members reported conversational knowledge suicide rates were six times greater.”

It is important to drive this point home. In the First Nation communities where native language retention was above 50 per cent (with at least half of the community retaining or acquiring conversational fluency) suicide rates were virtually null, zero. Yet in the bands where less than half of community members demonstrated conversational fluency in their native tongue, suicide rates spiked upwards of 6 times the rates of surrounding settler communities.

It is also worth noting how overall spikes in suicide prevalence found in Indigenous communities around the world indicate a strong correlation with the socio-political marginalization brought on by colonization. In other words, the suicide epidemic—which is at heart a crisis of mental health—is directly related to, if not directly caused by, the loss of culture and identity set in motion by colonialism.

Cultural continuity—and perhaps most specifically, native language preservation and retention—plays a crucial role in overcoming the ongoing native suicide epidemic—and indeed near universal barriers to indigenous mental health—once and for all First Nations, on a community by community basis.

by DGR News Service | Feb 12, 2016 | Culture of Resistance, Strategy & Analysis

Edited transcription of an interview by John Carico for The Fifth Column

How do you feel about Dr. Jill Stein and the Green Party of America?

I’m not a huge fan of the Green Party. I did a talk ten years ago at the Bioneers conference, which is about social change and environmentalism. One year their tagline was “the shift is hitting the fan,” about paradigm shifting. The thing that broke my heart was, so far as I know, I was the only person there who talked about power and psychopathology. I don’t think you can talk about social change without talking about power, and I don’t think you can talk about the destruction of the planet without talking about psychopathology. The Green Party has a lot of really good ideas, but how do you actually put them in place, given that those in power are sociopaths and the entire system rewards sociopathic behavior?

That doesn’t mean we need to give up or do nothing. A doctor friend of mine says the first step to a cure is proper diagnosis. If part of the disease that’s killing the planet is this sociopathological behavior, then fighting that sociopathological behavior needs to be part of our response.

I have voted Green in a couple of elections, and would vote again for a local Green. On the national level, the voting I’ve done was pretty much symbolic. I voted for Nader. I voted for a friend one time. The last time that I voted for any mainstream candidate was against Reagan in ‘84, and you pretty much had to vote against Reagan. But, interestingly, in 1980 I voted for Reagan and then realized I was an idiot, and voted Democrat in ’84. By ’88, I had an awakening and realized the whole system was just full of crap.

I do believe in voting on a local level. Voting on a national level may not change much, but locally, you can protect some things.

What warnings would you give young environmentalists as to how to differentiate green-washing from effective efforts?

The best way we learn is by making mistakes. The advice I give to young activists is to find what they love and defend it. Probably at some point, when they run up against the economic system, they’ll find themselves screwed over. That’s a lesson we all have to learn.

By the mid 1990s, I had already recognized that this culture is inherently destructive, but the “salvage rider” was still a big lesson for me. In ’95, activists all over the country had been able to shut down the Forest Service timber sales using the appeal process. Basically, if you could show the timber sales were breaking the law, you could appeal to have them stopped. Then they would have to produce a new document. Then you would stop them again by showing where they violated the Clean Water Act, Clean Air Act, etc. We were successful enough that Congress passed the salvage rider, wherein any timber sales that they wanted would be exempt from environmental regulations. The lesson was that any time you win using their rules to stop the injustice and stop the destruction, they will change the rules on you. There is really no substitute for learning this lesson yourself.

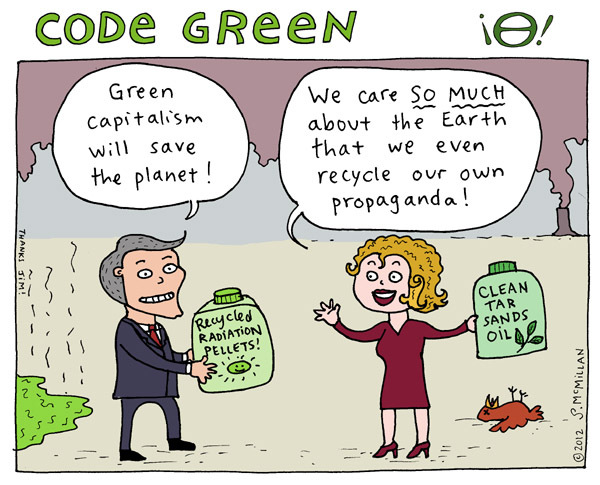

Artwork by Stephanie McMillan

Recognizing Greenwashing comes down to what so many indigenous people have said to me: we have to decolonize our hearts and minds. We have to shift our loyalty away from the system and toward the landbase and the natural world. So the central question is: where is the primary loyalty of the people involved? Is it to the natural world, or to the system?

What do all the so-called solutions for global warming have in common? They take industrialization, the economic system, and colonialism as a given; and expect the natural world to conform to industrial capitalism. That’s literally insane, out of touch with physical reality. There has been this terrible coup where sustainability doesn’t mean sustaining the natural ecosystem, but instead means sustaining the economic system.

So when figuring out if something is greenwashing, ask, “Does this thing primarily help sustain the economic system or the natural world?”

That’s one of the problems I have with industrial solar and wind energy. They are primarily aimed at extending the party, not aimed at protecting salmon.

I would also ask young people to think about the linkages. A solar cell may be really groovy and you can power your pot grow but where did the solar cell come from? It required mining. It required global infrastructure. Even climate activists ignore these linkages. I heard one activist say, “Solar power has no costs, only benefits.” Tell that to the lake in Bhatu, China, who is now completely dead as a result of rare earth mining. Tell that to the people, human and nonhuman, who no longer can sustain themselves from the lake or from the land poisoned all around it.

A friend of mine says, “A lot of environmentalists start by wanting to protect one specific piece of land, and move on to questioning the entire culture of western civilization.” Once you start asking the questions, they don’t stop. “Why are they trying to destroy this piece of land?” leads to, “Why do they want to destroy other pieces of land?” Then you ask, “Why do we have an economic system based on destroying land? What is the history of this economic system? What happens when it runs out of frontiers? What happens when you have overshoot?” It’s important for young activists never to stop asking those questions.

Can you name successful revolutions of the past that you think we should look to when forming our own strategies? Where colonizing powers withdrew, and left the economy to its people?

Economy is a really hard word when you have a global economic system. We can talk about the Irish kicking the British out, or the Vietnamese kicking out the United States, but the real winner in Vietnam is Coca Cola, because Vietnam is still tied into the global economic system.

I think it’s great that the Indians and Irish kicked out the British and that the Vietnamese kicked out the U.S., so I’m not attacking revolution when I say this. But one of the problems is that when you defeat a certain mindset, it will often find expression in another way. When the United States illegalized chattel slavery, the underlying entitlement, where white people felt entitled to the lives and labor of the African Americans, was still there and found expression in a new way with the Jim Crow Laws. We see this all the way up to today with mass incarceration of African American males in such shameful ways. Like I said earlier, we need to keep looking at the linkages and, unfortunately, this makes one depressed. Because when you see a victory, oftentimes, you also see a backlash and a reconfiguration and reestablishment of the underlying bigotry.

We see this too with monotheism’s movement toward science, especially mechanistic science, where the world is not alive. The monotheism of the Christian sky-god did the initial heavy lifting by taking meaning out of the world and leaving it up there. Mechanistic science is really just an extension. We can say, “Wow, we really got rid of the superstition and the bigotry that has to do with Christianity,” but this belief in science is even scarier. At least with the Christian sky-god there was someone above humans. Now humans are making themselves into this new god and think they control the whole planet.

Having said that as a preamble, the film The Wind That Shakes the Barley highlights one of the smart things the Irish did. The film starts off with all these Irish guys playing hurling. When I saw this at first, I thought, “What the hell does this have to do with the Irish liberation struggle?” As I mentioned, one of the things we have to do is to decolonize ourselves. They did this in part by playing Irish sports, using Gaelic Language, and reading Gaelic Literature. A successful revolution begins with breaking identification with the dominat system. First comes the emotional part. After that, it’s all strategy and tactics; you look around and ask, “What do we want to do, blow something up, vote, peaceful strikes?”

This ties back into everything we’ve talked about so far. Are we identifying with a system or are we identifying with those we are trying to protect? We can say the civil rights movement was successful in the sense that African Americans now have a provisional right to vote. Of course mass incarceration targets black males and thus takes away their right to vote, but the movement was still successful in that it accomplished some aims. This was done by identifying as black voters. So, identifying is very important.

Several years out from the writing of Decisive Ecological Warfare, is there anything you would change in terms of strategy that you’ve learned since?

We don’t know because no one is doing it. All I know is that there are more than 450 dead zones in the world and only one of those has recovered — in the Black Sea. The Soviet Union collapsed, making agriculture no longer economically feasible there. They stopped agriculture and the dead zone has recovered enough that they now have a commercial fishery. That makes clear to me that the planet will bounce back when this culture stops killing it, presuming there’s anything left.

The image that keeps coming to mind is this body, which is the earth, and it keeps bleeding out because it’s been stabbed 300 times. All these people are trying to heal this body, and they are doing CPR and putting on bandages and everything else. But they’re not stopping the killer who’s still stabbing the person to death. We have to stop that primary damage. We have to recognize that we can’t have it all. We can’t have a way of life that relies on industrial capitalism and continue to have a planet.

Now, I haven’t really answered your question, mostly because of what I said at first: nobody’s doing it, so we don’t know what mistakes there are in the strategy. I’ve been saying for fifteen years that if space aliens came down to earth and were doing what industrial civilization is doing to the planet, we would put in place Decisive Ecological Warfare. We would destroy their infrastructure. This is an important point. We can make a very strong argument that World War II was won by the Allies, primarily in the killing fields of Russia. But I would argue that either first or second most important was the destruction of German industrial capacity. Similarly, the North won the Civil War not just because they had better generals, but because they destroyed the South’s capacity to wage war.

I don’t care how we do it; we can do it by voting, if that works. But we have to find a way to stop this culture from waging war on the planet.

Will Potter’s Green Is the New Red talks about the crackdown against Green movements. Do you have any advice for people who want to speak openly about resistance but are afraid of the repercussions? Where is the line between security culture and the need for movement building? The Invisible Committee says we need to tie the actions that have been done into a narrative. Is the problem that the media never covers the actions of those who, for instance, did direct action against fracking in New Jersey, and that any direct action the media does cover seems to follow the horrible lone wolf narratives? Do you think this stifles our movement?

What you say makes a lot of sense. Coverage of direct actions, and the true reasons behind those actions, can’t be left to mainstream media. The movement needs people aboveground who can publish the narrative, and another separate group which is underground, to actually do it. Both roles are critical, but we need a firewall. Many activists have been arrested partly because they tried to do both. We in Deep Green Resistance are trying to fill that aboveground role, as is the North American Animal Liberation Front Press Office.

As for security culture…I think, sometimes, about the whole marijuana legalization movement (I realize this isn’t so much a successful revolutionary movement as a successful social movement). They’ve done a good job pushing an agenda that would have been unthinkable thirty years ago. They’ve done this by using this model, by being below ground with the growers and above ground with NORML. We can say the same thing about the IRA.

You need that firewall when you live in a security state, but we shouldn’t feel unnecessarily paranoid. Although surveillance is everywhere and they pretend they are God, those sitting at the top are not actually omniscient. Living in northern California, where the pot economy basically runs the entire economy, has helped me to a healthy understanding that the Panopticon is not as all seeing as it wants to be. (Again, I know there is a difference between A) growing marijuana, which many cops probably smoke or view with sympathy, and B) ending capitalism, which would freak out all the cops.)

I’m very naive about many things, including drug culture. But I used to teach at Pelican Bay, a Supermax Prison, and students told me that if you dropped them into any city in the world, they could find drugs within 15 minutes. I couldn’t even find a bathroom in 15 minutes! That means the underground economy is surviving the Panopticon very well; it isn’t omniscient.

The Green Scare did not succeed because of the power of the Panopticon, or because of brilliant police work. The cases of sabotage were solved by good old-fashioned stoolie, because Jake Ferguson was an abuser, junkie and a snitch. Basic security culture probably would have defeated the investigations.

Can you give a critique of anarchists and why you see a lot of their work as ineffective?

I had a conversation a couple years ago with a very famous, dedicated anarchist who has some critiques of anarchism, but didn’t want me to use his name because he knows if he says anything critical about anarchism he will get death threats. One of the big problems is that anarchism is open membership, in that anyone can become an anarchist simply by identifying as an anarchist. He says many who call themselves anarchist, aren’t; they are just antisocial and have found an ideological excuse for their bad behavior. He says anarchists have a long tradition of fighting for the eight-hour work day, or fighting againt fascism as in Spain. He says there needs to be a way to kick out people who are simply sociopaths who call themselves anarchists. I mean, here’s a quote by an anarchist/queer theorist: “Smashing the institutions of patriarchal racist capitalism goes hand in hand with being a repulsive perverted freak.” Seriously? We’re supposed to put this person in the same category as Goldman or Kropotkin? Are we going to let that person in, even if they are just a prick? Any group will have nutjobs: Republicans, Democrats, stamp collectors. But anarchism is so small, so vocal, and so open that the nut jobs really stand out and can discredit the larger group.

I’m also concerned about effectiveness. The individualist anarchists (as opposed to collectivist anarchists) have an active hostility toward organization. DGR isn’t alone in getting attacked for this, for being perceived as hierarchical. I’ve seen writing on this going back 40 years, with anybody who believes you can have an organization with a stable schema immediately being attacked as Stalinist. They attack the organization simply because it’s an organization. There is a great line by Samuel Huntington that says “The west won the world, not by the strength of its ideals, but by its application of organized violence.” (He’s actually a supporter of the western empire; he says it’s a good thing.)

I talk about this in Endgame. I have become convinced that the single most important invention of the dominant culture, which has allowed it to destroy the planet, is the top-down bureaucratic military style organization. I’m not saying we need to model our organizations after this, but it is really effective. It is how this culture was able to murder the Native Americans. They had one big army. In my experience, people can generally be very contentious. It’s really hard to get together on the same page.

I had a friend who was trying to start an environmental organization years ago. An indigenous member warned that 95% of the time would be spent dealing with personality conflicts, and the other 5% actually doing the work. It’s an accomplishment, albeit a terrible one, that the U.S. Military gets 5 million people to act toward one aim: killing brown people, or whatever it is they are doing. They have propaganda on TV and in print, they have the capitalist system which rewards bad behavior, they have an organizational schema and, on the other side, we are supposed to defeat them without being organized?

Civil War General McClellan lost against Lee due to piecemeal efforts. McClellan attacked in one place and Lee moved his troops back. McClellan attacked another place, and Lee moved his troops back. The Turkish military had a strategy of attacking in piecemeal, and lost every battle for nearly two hundred years. The Russians would attack en masse and the Turkish army would send in one unit at a time and get slaughtered. Nathan Bedford Forrest, a terrible racist but brilliant Civil War strategist, said, “The way you win a battle is getting there first with the most.” In any conflict you want local superiority.

You asked why I see anarchist strategy as oftentimes ineffective: if you’re fighting an organized force, you should try to be organized as well.

Can you give a definition of Radical Feminism, and a response to some of your detractors who’ve accused DGR of transphobia?

The question I would ask is “Given that we live in a rape culture, do you believe women have the right to bathe, sleep, organize, and gather, free from the presence of males?” If you do believe that women have that right, you will be accused of transphobia; you will receive death threats. If you are a woman, you will receive rape threats. I’ve been de-platformed over this, some trans activists have threatened to kill the children of DGR activists over this. All because I believe that women have the right to gather free from the presence of males.

I want to make clear that no one in DGR is telling anyone how to live. I don’t give a shit! I’m not saying people who identify as trans should get paid less for their work, or that they shouldn’t have whatever sexual partner they want. I’m not suggesting they should be kicked out of their house, or should be de-platformed from a university, or that anything bad should happen to them.

Somebody wrote me and said, “I have a a little five-year-old boy who loves to wear frilly clothes, loves to dance ‘like a girl’, and sing ‘like a girl’; doesn’t this make him transgender?” I wrote back and asked, “Are you saying only little girls can wear frilly clothes? Why can’t we just say ‘this is a little boy who likes to play with dolls, and sing in a high voice?’ Why can’t we just love and accept this child for who he is? What does it even mean to dance ‘like a girl’? ”

Shoddy thinking makes me angry. I know the trans allies are going to get mad when I say, “Women should be able to gather alone” because they will then ask, “Who are women? Aren’t trans who identify as women, in fact women?” My definition of woman is human female, and my definition of female is based on biology. Some species are dimorphic. Just like there are male marijuana plants and female marijuana plants, and male hippopotami and female hippopotami, there are male humans and female humans.

I want to say two things before anyone offers a counter-definition of ‘woman’:

1. A definition cannot be tautological. You cannot use a word to define itself. You cannot say, “A woman is someone who identifies as a woman,” any more than you can say, “A square is something that sort of resembles a square.”

2. A definition must have a clearly defined metric. If I said, “Here is a three sided thing, it’s a square,” you would say, “No, it’s not a square because a square has 4 sides.” You have to be able to verify. I can say I’m a vegetarian but I had great ribs for dinner. This destroys not only the word ‘vegetarian’ but also the word ‘definition.’ I would ask those who disagree with my definition, “What is your better definition that is verifiable, for the word ‘woman’?” and second, “Is the fact that I have a different definition for the word ‘woman’, which is defensible linguistically, so important that you think it’s acceptable for men to threaten to rape women?”

I’ve never publically discussed this point before, but I think this is an important issue to discuss. It’s part of a larger post-modern social movement that values what we think and what we feel over what is real. This takes us right back to the greenwashing, with people saying, “We have to come up with the economy we want.” No, first we have to figure out what the Earth will allow!

This culture has a deep hate for the embodied and for what is natural. Here’s a great example: I have coronary artery disease, and I told my doctor I was feeling better since I had been diagnosed. This was right before Obamacare kicked in, so I didn’t have insurance yet. The pain got less in that time, and I asked why. The doctor said that when the arteries get clogged, the body sends out capillaries all around it to basically do its own version of bypass surgery. I had never heard that before. We all think it’s some miraculous thing when someone cuts open your chest and does bypass surgery, but we don’t even think about it when the body does it itself. There is tremendous wisdom of knowledge in the body, and we have to learn to respect it. This is important, both on a larger global scale and on the personal scale. I think it’s really important to recognize how this culture devalues the body. How I feel is way less important than what is.

Can you talk a bit about left sectarianism?

This goes back to the machine-like organizational structure of the dominant culture, which I am not valorizing, but do recognize as really fucking effective. It’s been able to get people past sectarianism.

Over the years, I’ve gotten thousands of pieces of hate mail, of which only a couple hundred were from right wingers. I’ve gotten hate mail from anti-car activists because I drive a car, vegans because I eat meat, and anarchists because I believe in laws against rape. I’ve never understood why animal rights activists and hunters don’t work together to protect the habitat. I wouldn’t have a problem with that. I do believe in temporary alliances. Once that’s done, animal rights activists can sabotage the hunts.

There’s a great example from 300 or 400 CE. These two sects of Christianity fought, same name but one had an umlaut, and one didn’t. They killed each other — hundreds of people! — over the question “Do you believe the fires of hell are literal or figurative?”

I was talking to a guy about the left always attacking each other. He mentioned that where he lived in West Virginia, there used to be a single KKK chapter consisting of three brothers. Now they have three chapters, because they can’t stand each other. So it’s not just a problem on the left.

Instead of getting mad at sectarianism, which I’ve been doing for the past fifteen years, we need to figure out what to do about it. It’s probably part of the human condition.

My friend Jeanette Armstrong, an indigenous activist and writer, told me once, “We, in our community, have just as many squabbles as white people do. The difference is I know my great-grandchild might marry your great-grandchild, so we figure out how to get along.” I really like that. I think we just have to ask “What are we really trying to do?”

What’s wrong with me having a really strong disagreement with a trans activist, for example, and them having a really strong disagreement with me? We can both continue doing our work and, at worst, ignore each other. There are plenty of people with whom I disagree. Families have different political views all the time and still love each other.

The question I’ve been asked over the years that cracks me up is what it’s like at my house on Thanksgiving. One of my sisters is a petroleum engineer, and she used to be married to a guy who did cyanide heat leaching and owned a gold mine. Now she’s married to a guy who used to work for the NSA and now works for the Israeli Military. What do we talk about? We talk about football. My brother is a huge Seattle Seahawks fan, so go, Hawks! I don’t talk about environmental stuff; it’d just start an argument. So I don’t understand why we activists can’t agree to disagree.

Noam Chomsky, who really disagrees with the anti-industrial perspective, is another great example. I was scheduled to give a talk in Scotland, and they wanted to ask me about Chomsky blasting anti-industrialism. I really disagree with him on this, but I really respect his work, so my agent, a really smart person and also Chomsky’s agent, said just to say “I’m not attacking Chomsky. We just have a disagreement on this.” I don’t understand why we can’t do this more often. There is a limit, of course. Roman Polanski is a rapist, so it makes sense to talk about his personal life.

I can’t stand Richard Dawkins, have critiqued his work a lot, and have heard, individually, that he’s pompous. But I’ve never heard that he’s a rapist or anything so I don’t know why I wouldn’t just keep my critiques focused on his work.

I think film is really detrimental to communication, because it’s so removed from real life and the way we communicate. In order to move a film story forward, you need dramatic tension. So a lot of times you have people fighting who wouldn’t fight in real life, and because we learn to communicate from the stories we take in, we learn to be even more contentious than we otherwise would be.

I know someone who was on Bill Maher and was relatively polite. They got mad and said, “If you are ever on the show again, you have to interrupt people and be contentious, because that’s what makes the show work. We want Jerry Springer, we want people to throw chairs.” We may not really want that, but that’s what works for the spectacle. And then we learn that’s acceptable behavior.

I’m writing a book right now with a coauthor. We had a significant conflict Saturday, but both parties handled it in a mature fashion. We still have a significant disagreement, but we strengthened our friendship because we handled it maturely.

What are your thoughts on Prison Abolition?

When talking about prison abolition, I get a little nervous because I can’t wrap my head around it. Obviously the prison system is horrendous. But I’m not a prison abolitionist, because when I taught at the Supermax, the students agreed that the only way for prison abolition to work is if you’re going to kill a bunch of people. I knew a kid who was put out for prostitution at age four, and really, what chance did this kid have? He was really fucked up by the time he was six. Another kid was living on the streets of Oklahoma at six with his little brother. This guy is now doing life for murder. Probably the first time he knew where his next meal was coming from was when he got to prison.

My creative writing students used to pass around jellybeans, but warned me never to take anything from one inmate. He had tortured a person to death, and since getting to prison, he’d poisoned three people. Something, obviously, had happened to this guy.

A friend had a student who said to her, “I am so broken, I need to be kept out of society.”

Another guy — not sure if he was executed or died on death row — killed his wife and kid and put each heart in a separate pocket because “the blood couldn’t mix.” When he was on trial, he pulled out one of his eyes because “that’s how the feds were putting stuff into his brain.” That didn’t work, so he pulled out his other eye and ate it. I’m not saying he needed to be in prison as it currently exists, but he definitely needed to be separated from society. Or removed. What do you do with Ted Bundy?

I’m not saying that Ted Bundy makes the case for locking up some fifteen year old, and I’m not saying we shouldn’t eliminate for-profit prisons and the prison industrial complex. And I’m mostly against the death penalty — though I think Tony Hayward of BP should be executed, it’s outrageous as it is because it’s racist and classist. But the whole culture is completely messed up, and we can’t simply abolish all prisons without addressing the rest of the problems.

I had a student who said if he could change one thing about society’s perception of drug dealers, he’d destroy the stereotype of the drug dealer in an Armani suit. He said, “You try living in Oakland with three children and working at McDonalds; you can’t do it. Drug dealing puts food on the table.” Now he’s in prison which doesn’t help anybody.

Before I went to work in the prison system, I was completely apolitical on the drug war, because I never thought about it. But I became highly politicized because a lot of my students would have been perfectly fine neighbors as long as you either A) kept them off drugs, or B) made the drug legal like cigarettes. Many of my stdents did terrible things to get money for drugs, but if it had just been like cigarettes, they never would have murdered people.

One student was in because he was a marijuana dealer in the 1970s, and shot dead someone who tried to rob him. If he had been a shoe salesman and shot someone who tried to rob him, he wouldn’t have gone to jail for even one night, much less for the rest of his life.

A friend who was a police abolitionist went into communities known for police brutality, and got push back because the police are only one threat. The communities also have armed drug gangs, sometimes just as organized and just as nasty as the cops. The local people had no interest in police abolition until there was a community defense that made it practical. Similarly, Craig O’Hara said that anarchism is not about the eradication of all laws, but about making society such that you don’t need them. That’s it, exactly. You can’t push theoretical ideals at the expense of what people need for safety right now. I’ve seen anarchists get mad at women for calling the cops for rape!

I talked to Christian Parenti years ago about police. He observed that police have two functions: to stop meth addicts from bashing in the head of Grandma, and to bash in the heads of strikers. Two roles: to protect and serve, and to protect and serve the capitalists. Police like to emphasize the prior, whereas anti-police activists like to emphasize the latter. Parenti said they spend most of their time making sure people don’t drive 80 mph through a school zone. I don’t have a problem with someone getting a ticket for driving 80 mph through a school zone. But their most important social role is to bash in the heads of strikers.

We need to realize that our broad cultural conditions are really really, really terrible, and that something needs to be done about Ted Bundy until we have a society where Ted Bundys aren’t made.