For David Gulpilil, Sunsmart and the Earth, with love and thanks.

Written December 6 – 16, 2021

This is still being revised because it’s so difficult to find the words and tie everything together, but I thought I’d put this out in the open now.

A week ago a longtime friend died on the same day as a beloved representative of Australian Indigenous culture, and all week I have tried in vain to bring myself to write about it, in my desire to honour both of them. Each time before today, when I sat down at the keyboard, my mind became as blank as the virtual page.

Each day I got through my morning outdoors chores, had lunch, and then fell into a paralytic kind of sleep, as my mind autonomously decreed, “And now you will let go and rest, and heal.” Two to three hours later my consciousness would surface into a vast sense of calm and of open space. I thought very little emerging from sleep. I mostly just was, immersed in the rustle of the wind in the trees, the patter of occasional rain showers on the roof, the chattering of birds in the garden, the cries of black cockatoos in the forest behind the house. I was aware of my heart beating and the breath going in and out of me, and I felt and understood deeply both that I am part of the ecosystem out here, and that I am loved. No small things.

I am loved most obviously and comprehensively by my husband, and too by some of my friends. But I also feel profoundly embraced by what Australian Indigenous people call country, and have felt that way since I arrived here as a blow-in from Europe at age 11. The Australian bush got under my skin, it welcomed me, it was simultaneously like a friend and a cathedral filled with wonder. Remnant pieces of ancient Gondwana, resplendent and humming with life, echoing with vast time and timelessness, to those whose senses and minds and hearts are open. Places that teach you about nature, and about who you really are. “Development” opportunities and cash cows to many of the non-Indigenous who came after, who are destroying country, culture and biodiversity at alarming speeds.

In my young adulthood, wishing to protect country from the harm being inflicted on it, I worked as an environmental scientist and soon found out for myself that the people in charge who make the policy decisions about the Australian environment largely ignore the advice of the professionals that are employed to offer it. I remembered then that as a 12-year-old beginning middle school back in 1983, we had been shown an episode of Behind the News in which environmental scientists were warning that the Murray River would turn into an ecological disaster unless we changed the way we did things. In 1995, the Murray was worse instead of better; and in 2021, it is a dying place, like the Great Barrier Reef, like so many places in Australia once glorious with life.

So I became an educator, teaching people about life and its intricacies, science, literature, language and respect for nature and community. In midlife we got the opportunity to tree change, and in doing so, to steward 62 hectares of country, 50 hectares of which had escaped the white man’s bulldozer and, thanks to the prior landholder’s use of Indigenous-style fire management, also on his adjacent blocks, is a rare example of fabulously biodiverse Australian remnant vegetation on agricultural land.

My husband grew up in the Perth Hills doing fire management with the rather enlightened volunteer bushfire brigade there, and between us we had the skills and passion to look after the place and defend it from harm, such as being bulldozed by a tree corporation for their blue gum monocultures, or being made into a picnic area for sheep and goats, which would have sounded its death knell; or indeed, being left without active fire management as much of the remnant bushland in the district is, inviting – especially in this era of anthropogenic climate change – future Black Saturdays, and doom for wildlife and people alike.

But even in the absence of catastrophic bushfires, lack of traditional fire management of the sclerophyll results in ecological impoverishment, in plant species being choked out by a few opportunists and by dead, dry material that, in this dry-summer ecosystem, isn’t adequately decomposed by the fungi and other microbes which break down dead materials and recycle nutrients in most ecosystems. The Australian sclerophyll has come to depend on fire to do this – not catastrophic bushfires, but the kind of small, controlled, small-area, comparatively cool patchwork burns conducted at the right time of year to avoid animal nesting and to quickly recycle the nutrient-rich ash into growing things at the start of the rainy season, in autumn.

Indigenous Australians had managed the land in this way for many thousands of years before the European invasion, and the absence of traditional fire management from these ecosystems is one of the major drivers of biodiversity loss in Australia, behind wholesale destruction of Australian flora and fauna in land clearing for housing and agriculture, which has wiped out in excess of 80% of Australian ecosystems in many agricultural and suburban areas.

As a professional person in the environmental sciences, I was unable to effect the conservation of a single hectare of Australian ecosystem; as private citizens, my husband and I are actively conserving 50 hectares, as a service to nature and the community, and with no government help or tax concessions. Landcare was gutted long since, and most of the financial breaks for environmental work are designed to go to the big boys these days, even though they’re mostly just greenwashing, rather than being real environmental stewards.

My husband and I were so conscious, from the beginning, of the paradox that we were using white regulations about land title to follow in the footsteps of the Indigenous Australians who had stewarded the area for over 30,000 years before either of us ever breathed, or any European had set foot in this country.

Given the alternatives, we felt it was the right thing to do. Soon after we bought the place, we had a visit from one of the old residents born in the local farming community who had been involved in the fire management of our block and the surrounding areas since he was a young adult, who took Indigenous fire management methods seriously. “You have a patch of rare brown boronias – they need a fire this year so the tea-trees don’t choke them,” he said to us. We were newcomers, and so happy to talk to a person who knew the local bush intimately. He showed us the patch in question. We burnt it that autumn, and two years later we could smell the abundant flowers at our house on easterly winds.

We walk the tracks of our 50 hectare conservation area several times a week, which over ten years has added up to thousands of walks and a close familiarity with the landscape and its flora and fauna. After a couple of years of living here, we found it surprisingly intuitive to steward the place – if you look and listen, the land tells you what it needs. You understand which areas need a fire and which ones need to be left alone right now. You see the footprints of the foraging animals, you see where the tea-trees and dead wood are choking the place, you see the flush of healthy seedlings of species that were being crowded out and the sea of wildflowers two years after you burn a patch, and the native animals feeding abundantly in the lush regenerating areas, and the bandicoot tunnels in the adjacent dense old-growth areas where small marsupials find shelter – their “bedrooms” across the track from the “restaurant”. It is a joy and a privilege to be stewarding a piece of Gondwana, and to think of the people who did it before you for tens of thousands of years.

I went to middle school with exactly one Indigenous person, who sat next to me in what was called Social Studies class when it was read from the textbook that “Captain Cook discovered Australia” and we looked sideways at each other with wry smiles – the person whose ancestors had apparently lived in Australia for tens of thousands of years without discovering it, and the new arrival who was constantly told to “go back where you came from” by white people who didn’t get it when I said to them, “That’s funny, you don’t look very black to me!”

My deskmate, of course, understood my point, while the go-back-where-you-came-from brigade didn’t seem to understand their own hypocrisy – or how disgusting their behaviour was. They enjoyed disparaging others. On a daily basis, we heard “jokes” about boongsand poofters and spastics and dole bludgers, and heard various migrant groups referred to as wogs and teatowels and Nazis (…that last one, such an illustrative example of psychological projection). These “jokes” were especially favoured by immature, chestbeating males who would say, “Why don’t you laugh, don’t you have a sense of humour?”

The groups these bullies enjoyed kicking the most were Indigenous people, new migrants (or anyone with a different accent or appearance or tradition), refugees, people with disabilities, the unemployed and anyone LGBTIQ. And the bullies ruled the roost in that little dairy, beef and ALCOA town in the mid-80s, just as they still do in our parliament and public institutions in 2021, where significant proportions of employees are harassed, bullied and discriminated against in the workplace.

Australian society is still a difficult, unfair and hurtful thing, masquerading under this national myth of mateship and the fair go, but as I said at the start of this piece, one place I always felt unequivocally welcome from the beginning in this country was the Australian bush which the settlers have been so busy destroying and neglecting. I’ve since heard Indigenous people saying that country loves you if you love country. I did and it did. The Australian bush was my safe, welcoming and nurturing place from the beginning, where I could get away from the pain of a dysfunctional family of origin and from the pain of a dysfunctional society, and be embraced in its wonder and beauty, in a very physical way. I’ve never felt out of place out in the bush, or afraid. It’s chiefly dysfunctional people who make you feel out of place and afraid.

It bamboozles me that some people just see unattractive scrub when they traverse bushland, something best turned into a European-style park, car park, suburban subdivision or shopping centre. It bamboozles me that people are seriously afraid of snakes and spiders and “creepy-crawlies” when they won’t harm you if you leave them alone and when people are a thousand times more likely to come to harm as a result of driving on a road, eating modern non-food, or falling over. Ecosystems support life and diversity, are our biological cradle, are the place that will recycle us for the benefit of other beings after death if we don’t go out of our way (as our culture does) to lock our chemically embalmed corpses away six feet underground in solid boxes in what I think of as the final act of greed from a species that sits at the top of the food chain eating, eating, eating everything and then unwilling to give itself back at the end.

My husband and I love the bush, spent much time in it from childhood, recreationally walk bushland trails in National Parks and other conservation areas, and attempt to conserve the dwindling wild ecosystems both directly, by our own stewardship of a conservation area, and indirectly by reducing our environmental footprint – i.e. by reducing the amount of energy and resources we consume, by not reproducing above replacement rate, by reducing waste and growing increasing amounts of our own food, by being actively involved in revegetation efforts, by accepting and sharing information and experience, by collaborating instead of competing. To be a conservationist runs in the opposite direction to being a consumer, and that’s not an easy thing when you’ve grown up in a consumer society.

These days I mostly walk bush trails with my own two feet – and we document some of this with photos and stories on South Coast Wilderness Walks. But it wasn’t always that way. A lot of my early exploration of the Australian bush was done solo on horseback, because I lived on a farm as a teenager. Horses were available, and were willing hiking partners long before I found other humans who were interested in spending time in the bush. It’s also much safer to be in the bush on a horse than by yourself, especially as a teenage girl – not because of nature per se, but because of the existence of dysfunctional people.

On a good horse you can stay away and get away very effectively from people who mean to harm you, even if those people are in 4WDs or on trail bikes. Horses will always be superior to people and their machines out in the wild, and if you have enough skill and partnership with the horse and you know where to go, the horse, who has an unerring instinct for danger and for effective flight, will actively keep you safe. No mechanised mode of transport will catch you on narrow, winding, obstacle-strewn trails. I was chased on a couple of occasions, presumably by idiots who enjoy making trouble for others rather than axe murderers (but it’s not that big a leap), and they never even got close before they lost us altogether.

There were other benefits to being on horseback when in the bush. For example, the wildlife always hung around more when I was on a horse, whereas when I was on foot it took off. I think it thought I was less scary on the back of a huge herbivore. So horses had a role in shaping my love of the bush, especially in being able to get close to wildlife. And this brings me to the death of a long-time friend I was telling you about at the start of this piece.

A week ago, I lost a horse I’d had for a long, long time to a horrible disease. We had to put him down because he was becoming so debilitated despite everything we did to try to help him. This horse loved the bush and spent 12 years with me riding on access tracks through bushland where we live. I’d known him since his birth nearly 25 years before and had a chance to adopt him in 2009.

Losing a horse like that is like losing a dog you’ve loved – a big dog, who’s carried you around and taken you on adventures. My horse seemed to think I had some kind of disability because I was so slow compared to him, and seemed to think of himself as my special-needs wheelchair. If I was off him between gates, as soon as we got through the last one back into bushland, he’d stop and look at me and encourage me to climb back on so we could get back to moving along at a more respectable speed and not just walk. Here he is from those days:

A link to a documented ride in the bush from three summers ago, complete with many photographs and ecological commentary, that will give you a better idea of what it’s like to ride a horse in nature: Aussie Trail Outing With Camera

And you might think 25 is old for a horse, but the others who have died here were 28, 32 and 34. The youngest of those had the same illness and the middle one had cancer. She had still been getting prizes in ridden show classes we’d entered her in on a whim at the age of 27 just because she was looking in such great shape. Here she is at age 28.

The oldest was totally out of molars in his lower jaw and the supplementary feeding that had extended his life for five extra years since he began losing teeth could no longer keep him in good condition, so we put him down before he experienced unacceptable loss of quality of life. Romeo spent much of these last five years hanging out with us around the house, with a gold access pass to the garden, in which he mowed the lawns.

The death of a friend is always tough, whether they have two legs or four. It’s even tougher when you have to arrange their death, make that decision on behalf of them, which is something you generally don’t have to do with other humans, but something you often have to do with companion animals. So I had to arrange the ways and means and setting, and gave it careful thought.

Sunsmart, who was named for his habit of finding shade to rest in from the time he was born, died in the bush he loved, and he was happy and relaxed that morning, on an outing with us and eating oats we’d brought along, and he didn’t know a thing about it because the person who put him down is great with animals and a fantastic marksman. His body is now going back to the ecosystem – we do natural open burials here – and the local songbirds will soon be powered by the insects that are recycling his body. I will like that he will return to me in birdsong, sad as I am that his time here is over.

The morning after my four-legged friend was put down, I heard that David Gulpilil had died the same day as him. That was again so very sad – and he too dying too young because of a horrible illness. And yet for some reason it was comforting to me that the horse I loved and David Gulpilil had gone on the same day. They were both from the bush and all sorts of fabulous. My horse had died on country, and if Gulpilil now needed a horse for whatever reason (I know, it’s irrational, but anyway), this one was certainly going to look after him. (Anna, a Maori woman who was staying with us last week, said to me, “Not irrational, it’s nice, and anyway, watch your cattle for disturbance because he’ll still be running around in spirit!”)

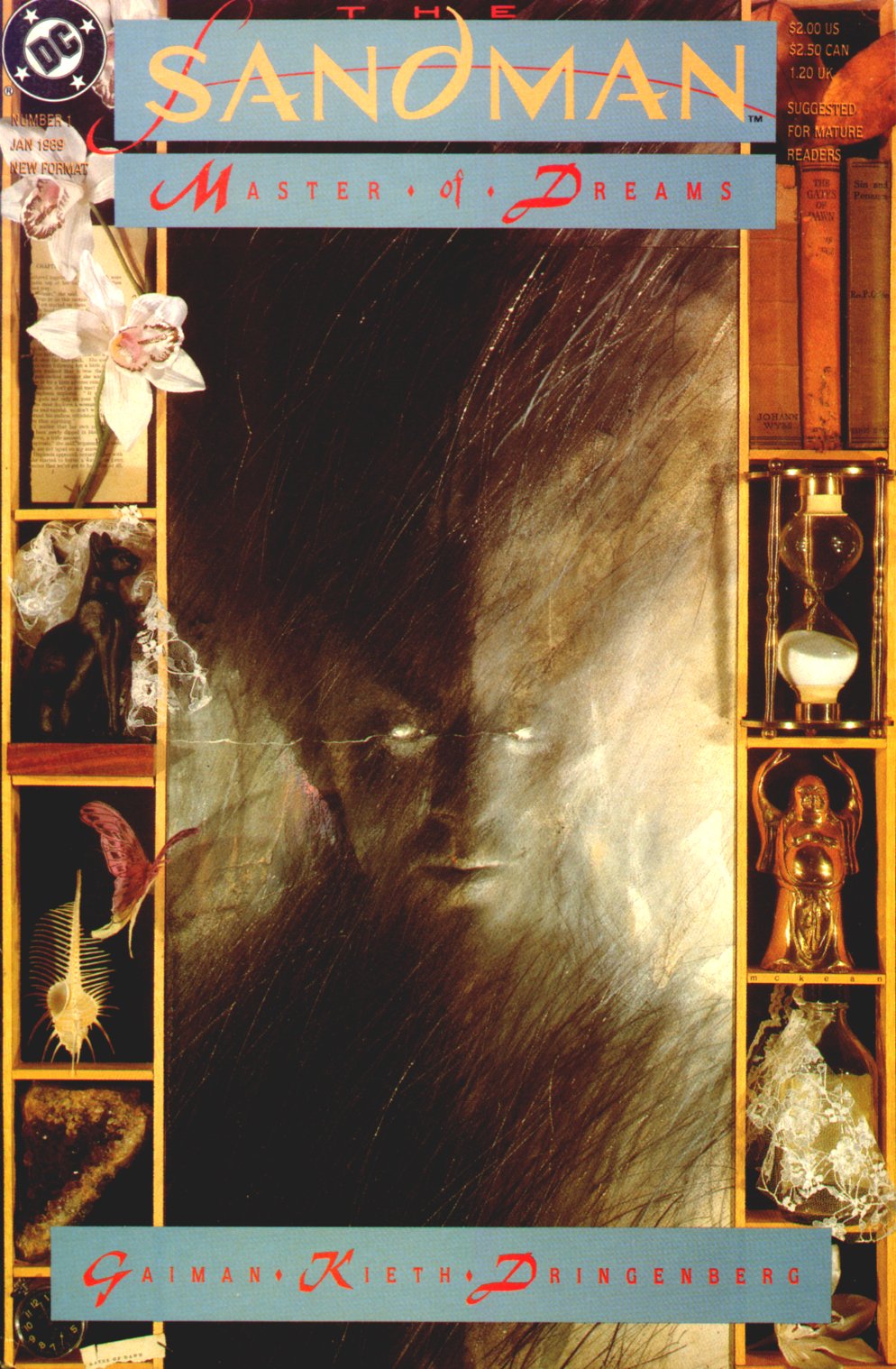

It was comforting to think of them riding into the sunset together. Brett says, “We make narratives with which to comfort ourselves, and that can be a good thing.” And indeed, starting from the time when euthanasia became a serious prospect several weeks earlier – when we were very consciously assessing the horse’s quality of life day by day – my husband started lending me another fantastic narrative to help with times like this and with life in general, in the shape of his Sandman collection.

Neil Gaiman’s Sandman is very cerebral and funny and sad and thought-provoking. It’s a constructed mythology about the seven Endless: Dream (main character), Death, Destiny, Destruction, Desire, Despair and Delirium – seven siblings who are anthropomorphic personifications who have to do their jobs in the universe. Death is the best of them I think – it’s a she, a very cool person, who’s nothing like the Grim Reaper, she’s more like a social worker and ultra compassionate and kind; and Dream is an interesting character. Delirium (who used to be Delight before she grew up) is kind of endearing. Destruction rebels against his role by withdrawing to the country to paint and write poetry, both of which are criticised by his talking dog. Brett’s one-sentence-summary: It’s the Prince of Stories in a story about stories. It also has a lot of beautiful visual art.

Often it is the art which confronts the difficult things about life while also celebrating the beautiful that is helpful when we’re faced with painful realities – whether visual art or film or written words or music. Sandman is one example, and Gulpilil’s work another. Gulpilil, in his art – he was a dancer, a painter, an actor, a storyteller – confronted terrible things, and celebrated beautiful things, and I thank him for it.

I heard about Gulpilil’s death on the radio, early in the morning the day after he and our Sunsmart died. My husband dropped the dog and me at our northeast gate on his way to work so I could avoid the ryegrass-laden pasture and associated allergic reactions, and take a walk around the outside boundaries of our conservation area – the forested ridge in the west, the valley floor transect in the south, and the forested ridge in the east, on the way back to the house. It was the first time I had been in the bush since the horse’s death the morning before. I was sad.

Yet as I walked along in the still-gentle light in the cool of the early morning, breathing in the scents of eucalyptus and earth and wildflowers, listening to the rustling of the leaves and branches in the breeze and the morning song of over a dozen species of bird – honeyeaters, whistlers, wrens, robins, ravens, magpies, kookaburras, various parrots and cockatoos, their shapes flitting in and out of light and shadow in the canopy – I felt a lightening of my body and heart. I walked, I breathed, and I felt the place embrace me, and teach me about life and death, and sustain me, and I felt my own part in the sustaining of the place and the millions of unsung lives which depend on this place, lives that are real and valuable and sacred, as my own life is real and valuable and sacred. I felt the cycle of life, how we come from earth and return to it and how our building blocks are stardust and go around and around through different forms of life, and have done so since before the dinosaurs died out 65 million years ago.

And because it felt right, out there in the bush, I began to talk to Gulpilil in my heart. Yolngu Kingfisher, I said – for Gulpilil means Kingfisher – we are sorry to lose you, and thankful for the life you had. I talk to you from country. Not Yolngu country, from Noongar country – but from country nevertheless. Yesterday a horse I loved died on country, the day you died. You would have liked him – he was kind to me and loved the bush and moved like poetry, like lightning. If you see him, and you want to look after him, he will look after you, I can guarantee you that. And say hello to my grandmother for me, if you see her. Other side of the world, long time ago, but I loved her, and she loved me. I will remember all of you with love.

That evening I watched Storm Boy for the first time.

It’s a beautiful film. I cried buckets, including when Gulpili’s character Fingerbones says at the end, after he has shown Storm Boy the grave of his beloved pelican, and a just-hatched nestling:

“Maybe Mr Percival starting over again. Bird like him never die.”