by DGR News Service | Mar 8, 2021 | Education, Movement Building & Support, Repression at Home, Strategy & Analysis

In this article Max Wilbert outlines the political and environmental need for security culture. He offers recommendations to secure communications.

By Max Wilbert

For 50 days, the Protect Thacker Pass camp has stood here in the mountains of northern Nevada, on Northern Paiute territory, to defend the land against a strip mine.

Lithium Americas, a Canadian corporation, means to blow up, bulldoze, or pave 5,700 acres of this wild, biodiverse land to extract lithium for “green” electric cars. In the process, they will suck up billions of gallons of water, import tons and tons of waste from oil refineries to be turned into sulfuric acid, burn 11,000 gallons of diesel fuel per day, toxify groundwater with arsenic, antimony, and uranium, harm wildlife from Golden eagles and Pronghorn antelope to Greater sage-grouse and the endemic King’s River pyrg, and lay waste to traditional territories still used by people from the Fort McDermitt reservation and the local ranching and farming communities.

The Campaign to Protect Thacker Pass

They claim this is an “environmentally sustainable” project. We disagree, and we mean to stop them from destroying this place.

Thus far, our work has been focused on outreach and spreading the word. For the first two weeks, there were only two of us here. Now word has begun to spread. The campaign is entering a new stage. There are new opportunities opening, but we must be cautious.

How Corporations Disrupt Grassroots Resistance Movements

Corporations, faced with grassroots resistance, follow a certain playbook. We can look at the history of how these companies respond to determine their strategies and the best ways to counteract them.

Corporations like Lithium Americas Corporation generally do not have in-house security teams, beyond basic security for facilities and IT/digital security. Therefore, when faced with growing grassroots resistance, their first move will be to hire an outside corporation to conduct surveillance, intelligence gathering, and offensive operations.

Private Military Corporations (PMCs) are essentially mercenaries acting largely outside of government regulation or democratic control. They are hired by private corporations to assist in their interests and act as for-hire businesses with few or no ethical considerations. Some examples of these corporations are TigerSwan, Triple Canopy, and STRATFOR.

PMCs are often staffed with U.S. military veterans, and employ counterinsurgency techniques and skills honed during the invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan, or other military operations. And in many cases, these PMCs collaborate with public law enforcement agencies to share information, such that law enforcement is essentially acting as a private contractor for a corporation.

Disruption Tactics Used by Corporate Goon Squads

PMCs can be expected to deploy four basic tactics.

- Intelligence Gathering

First, they will attempt to gather as much information on protesters as possible. This begins with what is called OSINT — Open Source Intelligence. This simply means combing through open records on the internet: Googling names, scrolling through social media profiles and groups, and compiling information that is publicly available for anyone who cares to look.

Other methods of information gathering are more active, and include physical surveillance (such as flying a helicopter overhead, as occurred today), signals intelligence (attempting to capture cell phone calls, emails, texts, and website traffic using a device like a Stingray also known as an IMSI catcher), and infiltration or human intelligence (HUMINT). This last is perhaps the most important, the most dangerous, and the most difficult to combat.

- Disruption

Second, they will attempt to disrupt the protest. This is often done by using the classic tactics of COINTELPRO to plant rumors, false information, and foment infighting to weaken opposition.

During the protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline, one TigerSwan infiltrator working inside the protest camps wrote to his team that

“I need you guys to start looking at the activists in your area and see if there are individuals who are vulnerable. They’re broke, always talking about needing gas money or whatever. Maybe they’re disillusioned, depressed a little. Life is fucking them over. We can buy them a bus ticket to any camp they want if they’re willing to provide intel. We win no matter what. If they agree to inform for pay, we get intel. If they tell our pitchman to go f*** himself/herself, the activist will start wondering who did take the money and it’ll cause conflict within the activist groups and it won’t cost us anything.”

In 2013, there was a leak of documents from the private intelligence company STRATFOR, which has worked for the American Petroleum Institute, Dow Chemical, Northrup Grumman, Coca Cola, and so on. The leaked documents revealed one part of STRATFOR’s strategy for fighting social movements. The document proposes dividing activists into four groups, then exploiting their differences to fracture movements.

“Radicals, idealists, realists and opportunists [are the four categories],” the leaked documents state. “The Opportunists are in it for themselves and can be pulled away for their own self-interest. The Realists can be convinced that transformative change is not possible and we must settle for what is possible. Idealists can be convinced they have the facts wrong and pulled to the Realist camp. Radicals, who see the system as corrupt and needing transformation, need to be isolated and discredited, using false charges to assassinate their character is a common tactic.”

As I will discuss later on, solidarity and movement culture is the best way to push back against these methods.

Other examples of infiltration and disruption have often focused on:

- Increasing tensions around racist or sexist behavior

- Targeting individuals with drug or alcohol addictions to become informants

- Using sex appeal and relationship building to get information

- Acting as an “agent provocateur” to encourage protesters to become violent, even to the point of supplying them with bombs, in order to secure arrests

- Spreading rumors about inappropriate behavior to sew discord and mistrust

- Intimidation

The third tactic used by these companies is intimidation. They will use fear and paranoia as a deliberate form of psychological warfare. This can include anonymous threats, shows of force, visible surveillance, and so on.

- Violence

When other methods fail, PMCs and public law enforcement will ultimately resort to direct violence, as we have seen with Standing Rock and many other protest movements.

As I have written before, colonial states enforce their resource extraction regimes with force, and we should disabuse ourselves of notions to the contrary. Vigilante violence is also always a concern. When people seek to defend land from destruction, men with guns are usually dispatched to arrest them, remove them from the site, and lock them in cages.

How to Resist Against Surveillance and Repression

There are specific techniques we can deploy to protect ourselves, and by extension, protect the land at Thacker Pass. These techniques are called “security culture.”

Security culture is a set of practices and attitudes designed to increase the safety of political communities. These guidelines are created based on recent and historic state repression, and help to reduce paranoia and increase effectiveness.

Security culture cannot keep us 100% safe, all the time. There is risk in political action. But it helps us manage risks that do exist, and take calculated risks when necessary to achieve our goals.

The first rule of security culture is this: be cautious, but do not live in fear. We cannot let their intimidation be effective. Creating paranoia is a key goal for PMCs and other repressive organizations. When they make us so paranoid we no longer take action, reach out to potential allies, or plan and carry out our campaigns, they win using only the techniques of psychological warfare. When we are fighting to protect the land and water, we are doing something righteous, and we should be proud and stand tall while we do this work.

The second rule of security culture is that solidarity is how we overcome paranoia, snitchjacketing, and rumor-spreading. We must act with principles and in a deeply ethical and honorable way. Work to build alliances, friendships, and trust—while maintaining good boundaries and holding people accountable. This is the foundation of a good culture.

In regards to infiltration, security culture recommends the following:

- It’s not safe nor a good idea to generally speculate or accuse people of being infiltrators. This is a typical tactic that infiltrators use to shut movements down.

- Paranoia can cause destructive behavior.

- Making false/uncertain accusations is dangerous: this is called “bad-jacketing” or “snitch-jacketing.”

- Build relationships deliberately, and build trust slowly. Do not share sensitive information with people who don’t need to know it. There is a fine line between promoting a campaign and sharing information that could put someone at risk.

- Good security culture focuses on identifying and stopping bad behavior.

- Do not talk to police or law enforcement unless you are a designated liaison.

Secure communications are an important part of security culture.

Here are some basic recommendations to secure your communications.

- Email, phone calls, social media, and text messages are inherently insecure. Nothing sensitive should be discussed using these platforms.

- Preferably, use modern secure messaging apps such as Signal, Wire, or Session. These apps are free and easy to use.

- We recommend setting up and using a VPN for all your internet access needs at camp. ProtonVPN and Firefox VPN are two reputable providers. These tools are easy to use after a brief initial setup, and only cost a small amount. Invest in security.

We must also remember that secure communications aren’t a magic bullet. If you’re communicating with someone who decides to share your private message, it’s no longer private. Use common sense and consider trust when using secure communications tools.

Security culture also warns us not talk about some sensitive issues, including:

- Your or someone else’s participation in illegal action.

- Someone else’s advocacy for such actions.

- Your or someone else’s plans for a future illegal action.

- Don’t talk about illegal actions in terms of specific times, people, places, etc.

Note: Nonviolent civil disobedience is illegal, but can sometimes be discussed openly. In general, the specifics of nonviolent civil disobedience should be discussed only with people who will be involved in the action or those doing support work for them. It’s still acceptable (even encouraged) to speak out generally in support of monkeywrenching and all forms of resistance as long as you don’t mention specific places, people, times, etc.

Conclusion

Security is a very important topic, but is challenging. There are so many potential threats, and we are not used to acting in a secure way. That’s why we are working to create a “security culture”—so that our communities of resistance are always considering security, assessing threats, studying our opposition, and creating countermeasures to their methods.

This article is only a brief introduction to the topic of security culture. Moving forward, we will be providing regular trainings in security culture to Protect Thacker Pass participants.

Most importantly, do not let this scare you, and do not be overwhelmed. Simply take one security measure at a time, begin to study it, and then implement better protocols one by one. We use the term “security culture” because security is a mindset that should be developed and shared.

Resources:

Recommended topics of study:

by DGR News Service | Jan 23, 2021 | Human Supremacy

by Cara Judea Alhadeff, PhD

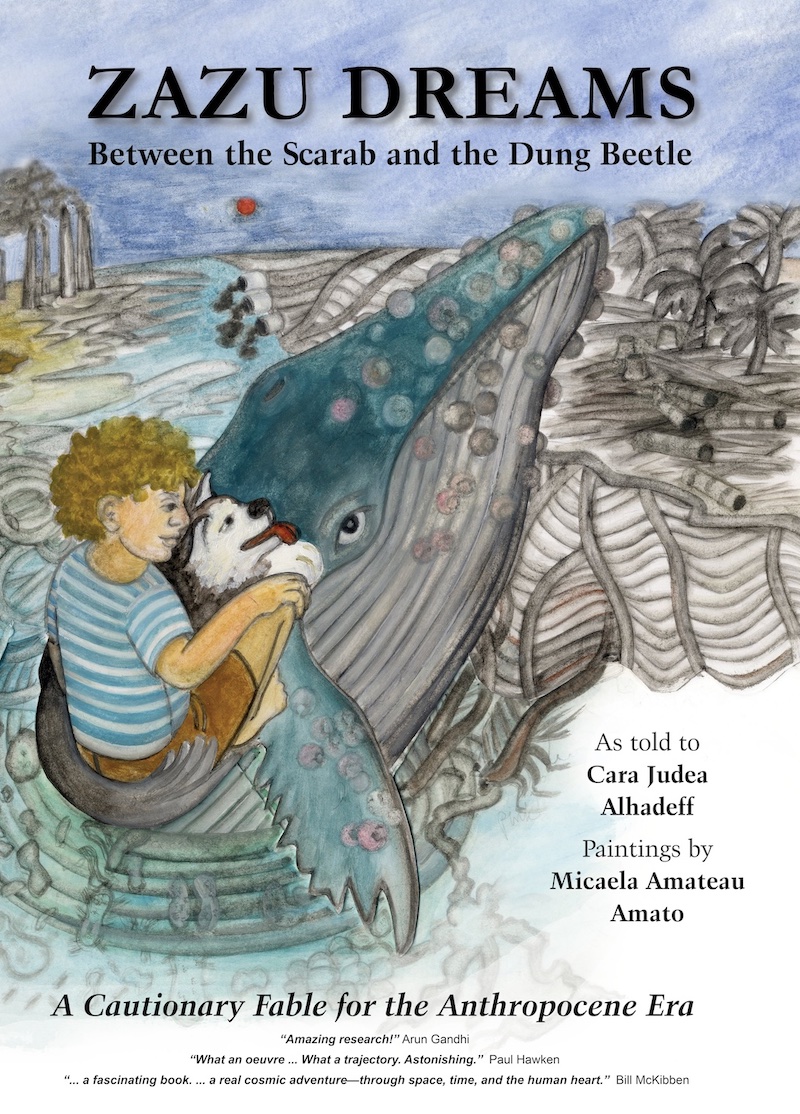

Paintings in this post are by Micaela Amateau Amato from Zazu Dreams: Between the Scarab and the Dung Beetle, A Cautionary Fable for the Anthropocene Era.

The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House —Audre Lorde

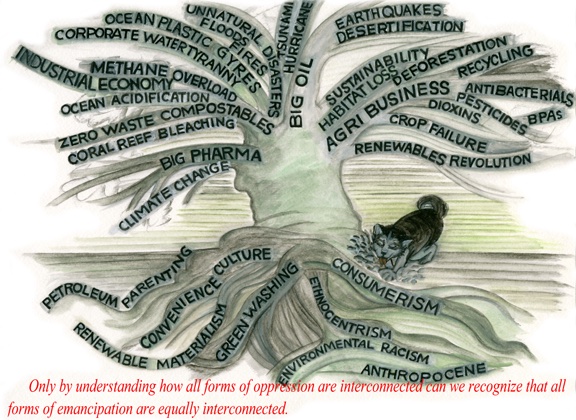

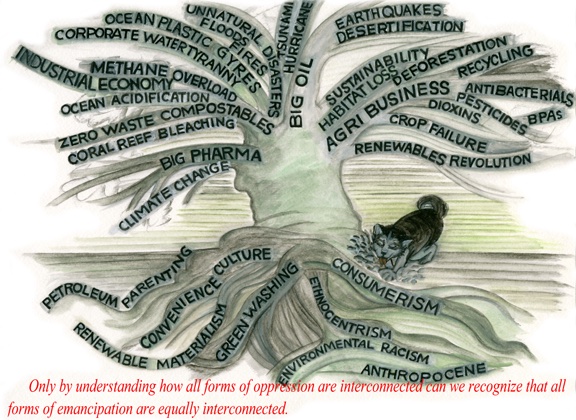

As with our shift from our systemically racist culture to one rooted in mutual respect for multiplicity and difference, we must practice caution during our transition out of our global petroculture. This vigilance should not be based on the motivation, but on the underlying false assumptions and strategies that perceived sustainability and “alternative” agendas offer. The implicit assumptions embedded in the concept of sustainability maintains the status quo. At this juncture of geopolitical, ecological, social, and corporeal catastrophes, we must critically question clean/green solutions such as the erroneously-named Renewable Energies Revolution. I suggest we face both the roots and the implications of how perceived solutions to our climate crisis, like “renewable” energies, may unintentionally sustain ecological devastation and global wealth inequities, and actually divert us from establishing long-term, regenerative infrastructures.

On the surface, sustainability agendas appear to offer critical shifts toward an ecologically, economically, and ethically sound society, but there is much evidence to prove that #1: these structural changes must be accompanied by a psychological shift in individuals’ behavior to effectively shut down consumer-waste convenience culture; and, #2: the core of too many green/clean solutions is rooted in the very essence of our climate crisis: privatized, industrialized-corporate capitalism. For example, in his The Age of Disinformation1, Eric Cheyfitz alerts us: The Green New Deal is a “capitalist solution to a capitalist problem.” It claims to address the linked oppressions of wealth inequity and climate-crisis, yet its proposed solutions avoid the very roots of each crisis.

My challenge is rooted in three interrelated inquiries:

- How are our daily choices reinforcing the very racist systems we are questioning or even trying to dismantle?

- How are the alternatives to fossil-fuel economies and environmental racism reinforcing the very systems we are questioning or even trying to dismantle?

- What can we learn from indigenous philosophies and socialist ecofeminist movements in order to establish viable, sustainable, regenerative infrastructures—an Ecozoic Era?

As we transition to supposedly carbon-free electricity, we must be attentive to the ways in which we unconsciously manifest the very racist hegemonies we seek to dislodge; we must be cautious of the greening-of-capitalism that manifests as “green colonialism” through a new dependency on what is falsely identified as “renewable” energies. Currently, human and natural-world habitat destruction are implicit in the mass production and disposal infrastructures of most “renewable energies:” solar, wind, biomass/biofuels, geothermal, ethanol, hydrogen, nuclear, and other ostensible renewables2.

This includes our technocratic petroleum-pharmaceutical addictions that use technologies to create “sustainability.” Even if policy appears to be in alignment with environmental ethics, we are consistently finding that policy change simply replaces one hegemony, one cultural of domination, with another—particularly within the framework of neoliberal globalization. Only when we acknowledge the roots of our Western imperialist crisis, can we begin to decolonize and revitalize all peoples’ livelihoods and their environments.

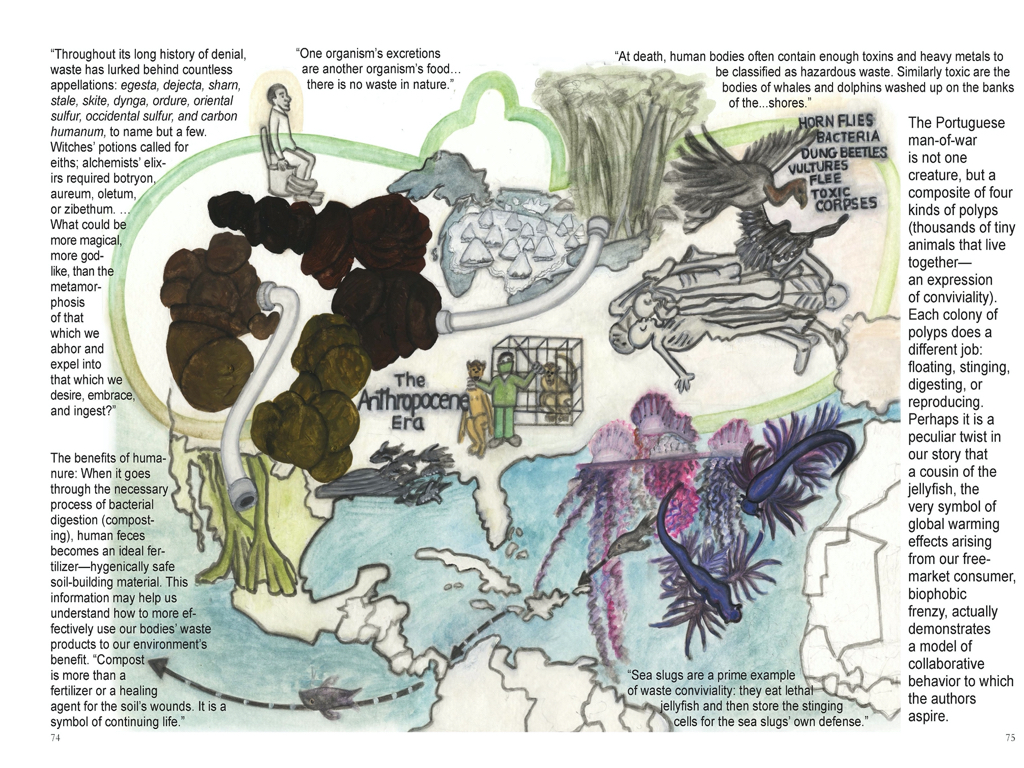

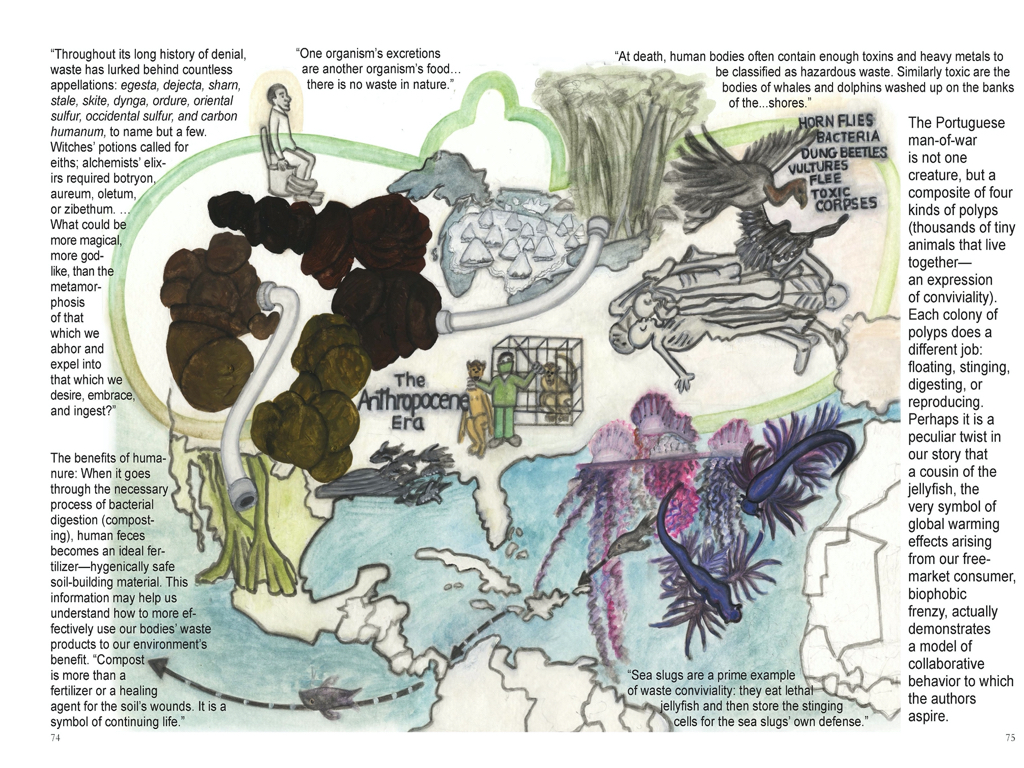

Zazu Dreams: Between the Scarab and the Dung Beetle, A Cautionary Fable for the Anthropocene Era3, my climate justice book that explores the perils of the Anthropocene, challenges cultural habits deeply embedded in our calamitous trajectory toward global ecological and cultural, ethnic collapse. The book’s main character reflects: “We have this crazy idea that anything ‘green’ is good—but we know that there is no clear-cut good and evil. What happens when the very solution causes more problems than the original problem it was supposed to fix?”

How we measure our ecological footprint4 and global biocapacity is often riddled with paradox—particularly in the face of green colonialism, or what I call humanitarian imperialism5. The litany of our collusion with corporate forms of domination is infinite within the Anthropocene Era (increasingly characterized as the Plasticene). Disinformation campaigns spread by fossil-fuel interests deeply root us in assimilationist consumerism. The Zazu Dreams’ characters witness social and environmental costs of subjugating others through both fossil-fuel-obsessed economies and their “green” replacements. Vaclav Smil warns us of this “Miasma of falsehood.” This implies replacing one destructive socializing norm—petro-pharma cultures sustained by fossil-fuel addicted economics—with another: purportedly “renewable” energies. These energies (I don’t call them renewable, because they are not “renewable” and not carbon-free)6, like fossil-fuels, are rooted in barbaric colonialist extractive industries. Once again, the “solution” is precisely the problem. Greenwashing is a prime example of the ways in which capitalism dictates our alleged freedom. Free market is a euphemism for economic terrorism. The “green economy has come to mean…the wholesale privatization of nature.”7 Consumerism becomes the default for making supposedly ethical choices.

In Deep Green Resistance, Lierre Keith urges us: “We can’t consume our way out of environmental collapse; consumption is the problem”. Even within the 99%, consumers are capitalism. Without convenience-culture/mass consumer-demand, the machine of the profit-driven free market would have to shift gears. We can’t blame oil companies without simultaneously implicating ourselves, holding our consumption-habits equally responsible. How can we insist government and transnational corporations be accountable, when we refuse to curb our buying, using, and disposal habits? We don’t have to go far back in our cross-cultural histories of nonviolent resistance and civil disobedience to learn from world-changing examples of strikes, unions, boycotts, expropriation, infrastructural sabotage, embargoes, and divestment protests.

Yet, most contemporary transition movements are founded in the very system they are trying to dismantle. Our perceived resources, these alternative forms of energy proposed to power our public electrical grids, are misidentified under the misleading misnomers: labels such “renewable”/ “sustainable” / “clean”/ “green”. How is “clean” defined? For whom? There is not a clear division between clean energy and dirty energy/dirty power—clean isn’t always clean. Neoliberal denial of corporeal and global interrelationships instills conformist laws of conduct that continually replenish our toxic soup in which we all live. One perceived solution to help us transition is to create alternatives to fossil fuel-addicted economies, as proposed, for example, through The United States’ proposed Green New Deal and its focus on allegedly “renewable” energies. However well-intentioned, these supposed alternatives perpetuate the violence of wasteful behavior and destructive infrastructures. Even if temporarily abated, they ultimately conserve the original crisis.

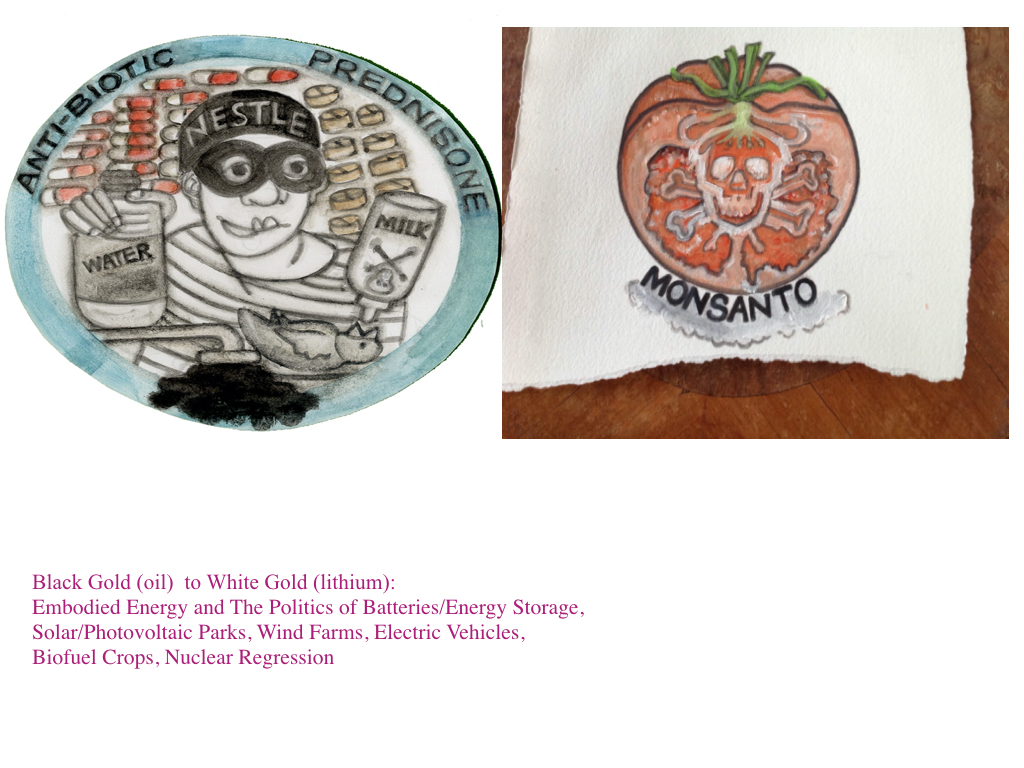

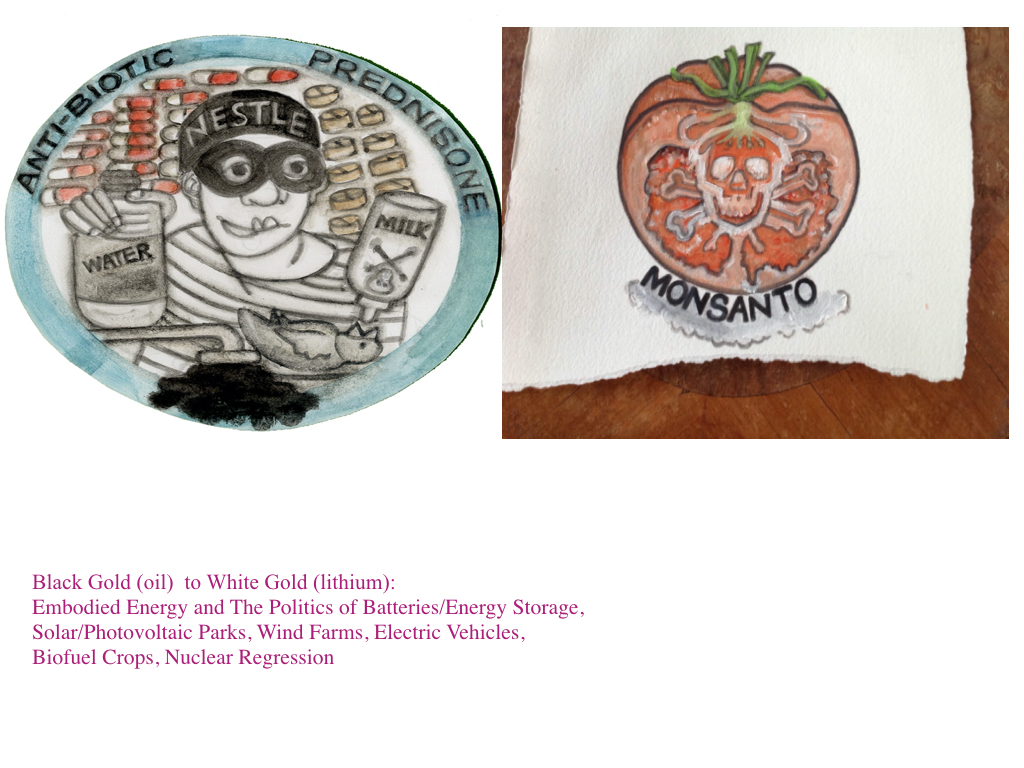

Below I address specific technologies that are falsely identified as “renewable” energy; technologies that actually reinforce the very problem they are trying to solve.

1. Solar/Photovoltaic and Wind Technologies: Given the proposed solutions using industrial solar and wind harvesting, Western imperialism has and will continue to dominate global relations. “Clean energy” easily gets soiled when it is implemented on an industrial scale. Western imperialist practices are implicit in solar cell and storage production (mining and other extractive industries) and disposal infrastructures. Congruently, industrial wind farms—aka: “blenders in the sky,”(chopping up migrating birds & bats) use exorbitant resources to produce and implement (both the wind turbines and their infrastructure), and devastate migrating wildlife (bats and birds, critical to healthy ecosystems and some of whom are endangered species).

Both wind and solar energies require vast quantities of fossil fuels to implement them on a grand scale. As we have seen throughout both California and China (two examples among too many), massive solar-energy sites/solar industrial complexes strip land bare—displacing human populations and migration routes of both wildlife and people for acres of solar fields, substations, and access roads—all of which require incredibly carbon-intensive concrete. Consuming massive tracts of land, 100-1000 times more land area is required for wind and solar, as well as for biofuel energy production than does fossil-fuel production.

2. Hydro-Power Technology: Large-scale dams for hydro-power have also historically had cataclysmic effects on indigenous peoples and their lands. Although macro-hydro, like fracking, has

finally been recognized for its calamitous consequences, perversely, it is still proposed as a viable alternative to fossil-fuel economies.

3. Battery Technology: Let’s begin with a California-based scenario: According to the Union of Concerned Scientists and their Climate Vulnerability Index (CVI) in California, fine particulate pollution harms African-American communities 43% more than predominantly white communities, Latino 39% more, and Asian-American communities 21% more. As if tailpipe emissions are the only humanitarian catastrophe, one “clean solution” is the electric vehicle for public transportation and for personal consumption. Completely ignoring the embodied energy involved, this perceived solution displaces the costs of environmental racism—once again exported out of the US into the global south—in this case to Boliva where lithium (essential for battery production) is primarily mined. Cobalt, also essential to battery production, is mined in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Like lithium, cobalt’s environmental and humanitarian costs are unconscionable—including habitat destruction, child slavery, and deaths. Eventually, production is followed by solar technology and battery e-waste dispersed throughout Asia, South America, and Africa. Additionally, rarely considered are the fossil-fuel sources used to supply the electricity for those private and public electric vehicles. And, of course most frequently, the poorest US populations work in and live near those coal mines/power plants/fracking stations.

The Renewable Energies Movement claims that our global addiction to oil (“black gold”) should be replaced by lithium (“white gold”). What we are not considering is that extracting lithium and converting it to a commercially viable form consumes copious quantities of water—drastically depleting availability for indigenous communities and wildlife, and produces toxic waste (that includes an already growing history of chemical leaks poisoning rivers, thus people and other animals). Paul Hawken‘s phrase “renewable materialism” counsels us that this hyper-idealized shift from a fossil-fuel paradigm to “renewable” energies is not a solution. Furthermore, these energies are LOW POWER DENSITY: they produce very little energy in proportion to the energy required to institutionalize them.

As the main character in Zazu Dreams prompts: “Even if we find great alternatives to fossil fuels, what if renewable energies become big business and just maintain our addiction to consumption? (…) Replacing tar sands or oil-drills or coal power plants with megalithic ‘green’ energy is not the solution—it just masks the original problem—confusing ‘freedom’ with free market and free enterprise”. We must now act on our knowledge that the renewable “revolution” is dangerously carbon intensive. And, as the authors of Deep Green Resistance caution us: “The new world of renewables will look exactly like the old in terms of exploitation.”

ENDNOTES

- Eric Cheyfitz, Age of Disinformation: The Collapse of Liberal Democracy in the United States. New York: Routledge, 2017.

- Surrogate band-aids that are frequently equal to or worse than what is being replaced include: bioplastics, phthalates replacements, and HFC’s. 1.Compostable disposables, also known as bioplastics, are most frequently produced from GMO-corn monoculture and “composted” in highly restricted environments that are inaccessible to the general public. Due to corn-crop monoculture practices that are dependent on agribusiness’s heavy use of pesticides and herbicides (for example, Monsanto’s Round-Up/glyphosate), compostable plastics are not a clean solution. Depending on their production practices, avocado pits may be a more sustainable alternative. But, the infrastructure and politics of actually “composting” these products are extraordinarily problematic. These not-so eco-friendly products rarely make it into the high temperatures needed for them to actually decompose. Additionally, their chemical compounds cause extreme damage to water, soil, and wildlife. They cause heavy acidification when they get into the water and eutrophication (lack of oxygen) when they leach nitrogen into the soil. 2.The trend to replace Bisphenol A (BPA) led to even more debilitating phthalates in products. 3.Lastly, we now know that hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), “ozone-friendly” replacements, are equally environmentally destructive as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs).

- Cara Judea Alhadeff, Zazu Dreams: Between the Scarab and the Dung Beetle, A Cautionary Fable for the Anthropocene Era. Berlin: Eifrig Publishing, 2017.

- The term “carbon footprint” was actually normalized through shame-propaganda by BP’s advertising campaigns. “The carbon footprint sham: A ‘successful, deceptive’ PR campaign,” Mark Kaufman, https://mashable.com/feature/carbon-footprint-pr-campaign-sham/

- Under the guise of the common good and universal values, humanitarian imperialism has emerged as a neo-colonialist method of reproducing the unquestioned status quo of industrialized, “First World” nations. For a detailed deracination of these fantasies (for example, taken-for-granted concepts of equality, poverty, standard of living), see Wolfgang Sachs’ anthology, The Development Dictionary: A Guide to Knowledge as Power. Although the term humanitarian imperialism is not explicitly used, all of the authors explore the hierarchical, ethnocentric assumptions rooted in development politics and unexamined paradigms of Progress. As public intellectuals committed to the archeology of prohibition and power distribution, we must extend this discussion beyond the context of international development politics and investigate how these normalized tyrannies thrive in our own backyard.

- The air and sun are renewable, but giant wind and solar installations are not.

- Jeff Conant, “The Dark Side of the ‘Green Economy,’” Yes! Magazine, August 2012, 63.

by DGR News Service | Oct 3, 2020 | Culture of Resistance, Movement Building & Support, Women & Radical Feminism

Excerpted from the book Deep Green Resistance — Chapter 15: Our Best Hope by Lierre Keith.

Featured Image: Women in 1919 Revolution in Egypt via Flickr

5. Deep Green Resistance means repair of human cultures

That repair must, in the words of Andrea Dworkin, be based on “one absolute standard of human dignity.” That starts in a fierce loyalty to everyone’s physical boundaries and sexual integrity. It continues with food, shelter, and health care, and the firm knowledge that our basic needs are secure. And it opens out into a democracy where all people get an equal say in the decisions that affect them. That includes economic as well as political decisions. There’s no point in civic democracy if the economy is hierarchical and the rich can rule through wealth.

People need a say in their material culture and their basic sustenance.

For most of our time on this planet, we had that. Even after the rise of civilization, there were many social, legal, and religious strictures that protected people and society from the accumulation of wealth. There exists an abundance of ideas on how to transform our communities away from domination and accumulation and toward justice and human rights. We don’t lack analysis or plans; the only thing missing is the decision to see them through.

We also need that new story that so many of the Transitioners prioritize. It’s important to recognize first that not everyone has lost their original story. There are indigenous peoples still holding on to theirs. According to Barbara Alice Mann,

The contrast between western patriarchal and Iroquoian matriarchal thought could not be more clear.… I do not think it is possible to examine the real impetus behind mother-right unless we walk boldly up to the spiritual underpinnings of its systems. By the same token, we cannot free ourselves of the serious damage of patriarchy, unless we appreciate where matriarchy’s spiritual allegiances lie.

The Iroquois are unapologetic about the fact that spirit informs and undergirds all our social, economic, and governmental structures. Every council of any honor begins with thanksgiving, that is, an energy-out broadcast, to make way for the energy in-gathering required by the One Good Mind of Consensus. When a council fails, people just assume that the faithkeeper who opened it did a poor job in the thanksgiving department. In a thanksgiving address, all the spirits of Blood and Breath (or Earth and Sky) are properly gathered and acknowledged, with the ultimate acknowledgment being that the One Good Mind of Consensus requires the active participation of not just an elite but everyone in the community. This is a foundational insight of all matriarchies.

She describes a culture where “things happen by consultation, not by fiat,” based on a spiritual understanding of everyone’s participation in the cosmos rather than the “paranoid isolation” brought on by the temper tantrums of a sociopathic God. This is the difference between cultures of matriarchy and patriarchy, egalitarianism and domination, participation and power.

Such stories need to be told, but more, they need to be instituted. All the stories in the world will do no good if they end with the telling.

One institution that deserves serious consideration is a true people’s militia. Right now in the United States only the right wing is organizing itself into an armed force. In 2009, antigovernment militias, described by the Southern Poverty Law Center as “the paramilitary arm of the Patriot movement,” grew threefold, from forty-two to 127. We should be putting weapons in the hands of people who believe in human rights and who are sworn to protect them, not in those of people who feel threatened because we have a black president.

If jack-booted, racist, and increasingly paranoid thugs coalesce into an organized movement with its eye on political power, we don’t need to relive Germany in 1936 to know where it may end, especially as energy descent and economic decline continue. Contemporaneous with a people’s militia would be training in both the theory and practice of mass civil disobedience to reject illegitimate government or a coup if that comes to pass. Gene Sharp’s Civilian-Based Defense explains how this technique works with successful examples from history. His book is a curriculum that should be added to Transition Towns and other descent preparation initiatives.

But if the people with the worst values are the ones with the guns and the training, we may be very sorry. This is a dilemma with which progressives and radicals should be grappling. A large and honorable proportion of the left believes in nonviolence, a belief that for many reaches a spiritual calling. But societies through history and currently around the globe have degenerated into petty tyrannies with competing atrocities. Personal faith in the innate goodness of human beings is not enough of a deterrent or shield for me.

A true people’s militia would be sworn to uphold human rights, including women’s rights. The horrors of history include male sexual sadism on a mass scale. Women are afraid of men with guns for good reason. But rape is not inevitable. It’s a behavior that springs from specific social norms, norms that a culture of resistance can and must confront and counteract, whether or not we have a people’s militia. We need a zero tolerance policy for abuse, especially sexual abuse.

Military organizations, like any other culture, can promote rape or stop it. Throughout history, soldiers, especially mercenary soldiers, have often been granted the “right” to rape and plunder as part of their payment. Other militaries have taken strong stands against rape. Writes Jean Bethke Elshtain, “The Israeli army … are scrupulous in prohibiting their soldiers to rape. The British and United States armies, as well, have not been armies to whom rape was routinely ‘permitted,’ with officers looking the other way, although British and American soldiers have committed ‘opportunistic’ rapes. Even in the Vietnam War, where incidents of rape, torture and massacre emerged, raping was sporadic and opportunistic rather than routine.” The history of military atrocities against civilians is a history; it’s not universal, and it’s not inevitable. Elshtain continues,

“War is not a freeform unleashing of violence; rather, fighting is constrained by considerations of war aims, strategies and permissible tactics. Were war simply an unbridled release of violence, wars would be even more destructive than they are.”

Western nations, over hundreds of years, assembled an unwritten code of conduct for militaries, known as the “customary law of war,” which tried to limit the suffering of soldiers and to safeguard civilians. This was eventually codified into the Hague Convention Number IV of 1907 and the Geneva Convention of 1949. These attempted to limit looting and property destruction and to protect noncombatants. The Uniform Code of Military Justice is very clear that rape is unacceptable, and even gets the finer points of how “consent” with an armed assailant is a pretty meaningless concept. Elshtain also notes that “[the] maximum punishment for rape is death. Thus, interestingly, rape is a capital offense under the Uniform Code of Military Justice, by contrast to most civilian legal codes.

Getting the command structure to take rape and human rights abuses seriously is, of course, the next step. As Elshtain points out, “It is difficult to bring offenders to trial unless the leaders of the military forces are themselves determined to ferret out and punish tormentors of civilian populations. Needless to say, if the strategy is itself one of tormenting civilians, rapists are not going to be called before a bar of justice.”

It will be up to the founders and the officers of new communities to set the norms and to make those norms feminist from the beginning. The following would go a long way toward helping create a true people’s militia, and not just another organization of armed thugs to “trample the grass”—the women and girls who so often suffer when men fight for power.

- Female officers. Women must be in positions of authority from the beginning, and their authority needs absolute respect from male officers.

- Training curriculum that includes feminism, rape awareness, and abuse dynamics, and a code of conduct that emphasizes honorable character in protecting and defending human rights.

- Zero tolerance for misogynist slurs, sexual harassment, and assault amongst all members.

- Clear policies for reporting infringements and clear consequences.

- Background checks to exclude batterers and sex offenders from the militia.

- Severe consequences for any abuse of civilians.

A people’s militia could garner widespread support by following a model of community engagement, much as the Black Panthers grew through their free breakfast program. Besides basic activities like weapons training and military maneuvers, the militia could help the surrounding community with the kind of services that are always appreciated: delivering firewood to the elderly or fixing the roof of the grammar school. The idea of a militia will make some people uneasy, and respectful personal and community relationships would help overcome their reticence.

by DGR News Service | Sep 29, 2020 | Culture of Resistance, Movement Building & Support, The Solution: Resistance

Excerpted from the book Deep Green Resistance — Chapter 15: Our Best Hope by Lierre Keith.

Featured image: Felix Mittermeier via Unsplash

3. Deep Green Resistance must be multilevel.

There is work to be done—desperately important work—aboveground and underground, in the legal sphere and the economic realm, locally and internationally. We must not be divided by a diversionary split between radicalism and reformism. One more time: the most militant strategy is not always the most radical or the most effective. The divide between militance and nonviolence does not have to destroy the possibility of joint action. People of conscience can disagree. They can also respectfully choose to work in different arenas requiring different tactics. I can think of no scenario in which a program to provide school cafeterias with food straight from local, grass-based farms would be advanced by explosives. In contrast, a project to save the salmon would do well to consider such an option.

Every movement for justice struggles with the subject. Violence, including property destruction, should not be undertaken without serious reflection and ethical, even spiritual, investigation. Better to accept that as individuals we will arrive at different answers—but that we have to build a successful movement despite those differences.

That shouldn’t be hard, considering that this entire culture has to be replaced. We need every level of action and every passion brought to bear. The Spanish Anarchists stand as a great example of a broad and deep effort to transform an entire society. Writes Murray Bookchin, “The great majority of these [affinity] groups were not engaged in terrorist actions. Their activities were limited mainly to general propaganda and to the painstaking but indispensable job of winning over individual converts.” The café was where all that discussion and proselytizing happened, just as it happened in pubs for the Irish and the IRA. The anarchists in Barcelona took over railroads, factories, public utilities, retail and wholesale businesses, and ran them by workers’ committees. They also created their own police force to patrol their neighborhoods, and revolutionary tribunals to mete out justice. Before the Fascist victory, the anarchists in Andalusia created communal land tenure arrangements, stopped using money for internal exchange of goods, and established directly democratic popular assemblies for their governance. They also started over fifty alternative schools across the country. Their educational ideas spread through Europe, landing in England where they were taken up by A. S. Neill at his famous Summerhill. From there, the concept of free schools migrated to the US. If you are involved with any student-directed, alternative education, you are a direct descendent of the Spanish Anarchists.

Every institution across this culture must be reworked or replaced by people whose loyalty to the planet and to justice is absolute. A DGR movement understands the necessity of both aboveground and underground work, of confronting unjust institutions as well as building alternative institutions, of every effort to transform the economic, political, and social spheres of this culture. Whatever you are called to do, it needs to be done.

It is unlikely that a political candidate on the national or even state level will have a chance of winning on a platform of truth telling, at least not in the United States. The industrial world needs to reduce its energy consumption to that of Brazil or Sri Lanka. That this reduction is inevitable doesn’t make it any more palatable to the average American, who will likely only give up his entitlement when it’s pried from his cold, dead fingers. At the local level, the political process may be more amenable to radical truth telling, especially in progressive enclaves. For those with the skills and interest, running for local office could yield results worth the effort. It could also scale up to other communities. What kinds of institutional change could be affected at the local level is a question worth asking.

From outside, a vast amount of pressure is needed to stop fossil fuel and other industrial extractions. Legislative initiatives, boycotts, direct action, and civil disobedience must be priorities. We need to form groups like Climate Camp, which started in 2006 with a teach-in and protest at a coal-fired plant in West Yorkshire, England. They’ve blockaded the European Carbon Exchange in London, protested runway expansion at Heathrow Airport, and are taking action against BP for its participation in the tar sands. In their own words,

The climate crisis cannot be solved by relying on governments and big businesses with their “techno-fixes” and other market-driven approaches.… We must therefore take responsibility for averting climate change, taking individual and collective action against its root causes and to develop our own truly sustainable and socially just solutions. We must act together and in solidarity with all affected communities—workers, farmers, indigenous peoples and many others—in Britain and throughout the world.

If the referendums and court decisions and market solutions fail, if the civil disobedience and blockades aren’t enough, a Deep Green Resistance is willing to take the next step to stop the perpetrators.

In the UK, someone is feeling the urgency. On April 12, 2010, the machinery at Mainshill coal site was sabotaged, machinery that was Mordorian in its destructive power: “a 170 tonne face scrapping earth mover.” The coal was slated for the Drax Power Station, “recognised as the most polluting in the UK.”

According to their communiqué:

Sabotage against the coal industry will continue until its expansion is halted.

This is a simple vow, an “I do” to every living creature. Deep Green Resistance remembers that love is a verb, a verb that must call us to action.

by DGR News Service | Aug 30, 2020 | The Solution: Resistance

This post has been crossposted from Albert-Einstein Institute.

Practitioners of nonviolent struggle have an entire arsenal of “nonviolent weapons” at their disposal. Listed below are 198 of them, classified into three broad categories: nonviolent protest and persuasion, noncooperation (social, economic, and political), and nonviolent intervention. A description and historical examples of each can be found in volume two of The Politics of Nonviolent Action, by Gene Sharp.

THE METHODS OF NONVIOLENT PROTEST AND PERSUASION

Formal Statements

1. Public Speeches

2. Letters of opposition or support

3. Declarations by organizations and institutions

4. Signed public statements

5. Declarations of indictment and intention

6. Group or mass petitions

Communications with a Wider Audience

7. Slogans, caricatures, and symbols

8. Banners, posters, and displayed communications

9. Leaflets, pamphlets, and books

10. Newspapers and journals

11. Records, radio, and television

12. Skywriting and earthwriting

Group Representations

13. Deputations

14. Mock awards

15. Group lobbying

16. Picketing

17. Mock elections

Symbolic Public Acts

18. Displays of flags and symbolic colors

19. Wearing of symbols

20. Prayer and worship

21. Delivering symbolic objects

22. Protest disrobings

23. Destruction of own property

24. Symbolic lights

25. Displays of portraits

26. Paint as protest

27. New signs and names

28. Symbolic sounds

29. Symbolic reclamations

30. Rude gestures

Pressures on Individuals

31. “Haunting” officials

32. Taunting officials

33. Fraternization

34. Vigils

Drama and Music

35. Humorous skits and pranks

36. Performances of plays and music

37. Singing

Processions

38. Marches

39. Parades

40. Religious processions

41. Pilgrimages

42. Motorcades

Honoring the Dead

43. Political mourning

44. Mock funerals

45. Demonstrative funerals

46. Homage at burial places

Public Assemblies

47. Assemblies of protest or support

48. Protest meetings

49. Camouflaged meetings of protest

50. Teach-ins

Withdrawal and Renunciation

51. Walk-outs

52. Silence

53. Renouncing honors

54. Turning one’s back

THE METHODS OF SOCIAL NONCOOPERATION

Ostracism of Persons

55. Social boycott

56. Selective social boycott

57. Lysistratic nonaction

58. Excommunication

59. Interdict

Noncooperation with Social Events, Customs, and Institutions

60. Suspension of social and sports activities

61. Boycott of social affairs

62. Student strike

63. Social disobedience

64. Withdrawal from social institutions

Withdrawal from the Social System

65. Stay-at-home

66. Total personal noncooperation

67. “Flight” of workers

68. Sanctuary

69. Collective disappearance

70. Protest emigration (hijrat)

THE METHODS OF ECONOMIC NONCOOPERATION: ECONOMIC BOYCOTTS

Actions by Consumers

71. Consumers’ boycott

72. Nonconsumption of boycotted goods

73. Policy of austerity

74. Rent withholding

75. Refusal to rent

76. National consumers’ boycott

77. International consumers’ boycott

Action by Workers and Producers

78. Workmen’s boycott

79. Producers’ boycott

Action by Middlemen

80. Suppliers’ and handlers’ boycott

Action by Owners and Management

81. Traders’ boycott

82. Refusal to let or sell property

83. Lockout

84. Refusal of industrial assistance

85. Merchants’ “general strike”

Action by Holders of Financial Resources

86. Withdrawal of bank deposits

87. Refusal to pay fees, dues, and assessments

88. Refusal to pay debts or interest

89. Severance of funds and credit

90. Revenue refusal

91. Refusal of a government’s money

Action by Governments

92. Domestic embargo

93. Blacklisting of traders

94. International sellers’ embargo

95. International buyers’ embargo

96. International trade embargo

THE METHODS OF ECONOMIC NONCOOPERATION: THE STRIKE

Symbolic Strikes

97. Protest strike

98. Quickie walkout (lightning strike)

Agricultural Strikes

99. Peasant strike

100. Farm Workers’ strike

Strikes by Special Groups

101. Refusal of impressed labor

102. Prisoners’ strike

103. Craft strike

104. Professional strike

Ordinary Industrial Strikes

105. Establishment strike

106. Industry strike

107. Sympathetic strike

Restricted Strikes

108. Detailed strike

109. Bumper strike

110. Slowdown strike

111. Working-to-rule strike

112. Reporting “sick” (sick-in)

113. Strike by resignation

114. Limited strike

115. Selective strike

Multi-Industry Strikes

116. Generalized strike

117. General strike

Combination of Strikes and Economic Closures

118. Hartal

119. Economic Shutdown

THE METHODS OF POLITICAL NONCOOPERATION

Rejection of Authority

120. Withholding or withdrawal of allegiance

121. Refusal of public support

122. Literature and speeches advocating resistance

Citizens’ Noncooperation with Government

123. Boycott of legislative bodies

124. Boycott of elections

125. Boycott of government employment and positions

126. Boycott of government depts., agencies, and other bodies

127. Withdrawal from government educational institutions

128. Boycott of government-supported organizations

129. Refusal of assistance to enforcement agents

130. Removal of own signs and placemarks

131. Refusal to accept appointed officials

132. Refusal to dissolve existing institutions

Citizens’ Alternatives to Obedience

133. Reluctant and slow compliance

134. Nonobedience in absence of direct supervision

135. Popular nonobedience

136. Disguised disobedience

137. Refusal of an assemblage or meeting to disperse

138. Sitdown

139. Noncooperation with conscription and deportation

140. Hiding, escape, and false identities

141. Civil disobedience of “illegitimate” laws

Action by Government Personnel

142. Selective refusal of assistance by government aides

143. Blocking of lines of command and information

144. Stalling and obstruction

145. General administrative noncooperation

146. Judicial noncooperation

147. Deliberate inefficiency and selective noncooperation by enforcement agents

148. Mutiny

Domestic Governmental Action

149. Quasi-legal evasions and delays

150. Noncooperation by constituent governmental units

International Governmental Action

151. Changes in diplomatic and other representations

152. Delay and cancellation of diplomatic events

153. Withholding of diplomatic recognition

154. Severance of diplomatic relations

155. Withdrawal from international organizations

156. Refusal of membership in international bodies

157. Expulsion from international organizations

THE METHODS OF NONVIOLENT INTERVENTION

Psychological Intervention

158. Self-exposure to the elements

159. The fast

a) Fast of moral pressure

b) Hunger strike

c) Satyagrahic fast

160. Reverse trial

161. Nonviolent harassment

Physical Intervention

162. Sit-in

163. Stand-in

164. Ride-in

165. Wade-in

166. Mill-in

167. Pray-in

168. Nonviolent raids

169. Nonviolent air raids

170. Nonviolent invasion

171. Nonviolent interjection

172. Nonviolent obstruction

173. Nonviolent occupation

Social Intervention

174. Establishing new social patterns

175. Overloading of facilities

176. Stall-in

177. Speak-in

178. Guerrilla theater

179. Alternative social institutions

180. Alternative communication system

Economic Intervention

181. Reverse strike

182. Stay-in strike

183. Nonviolent land seizure

184. Defiance of blockades

185. Politically motivated counterfeiting

186. Preclusive purchasing

187. Seizure of assets

188. Dumping

189. Selective patronage

190. Alternative markets

191. Alternative transportation systems

192. Alternative economic institutions

Political Intervention

193. Overloading of administrative systems

194. Disclosing identities of secret agents

195. Seeking imprisonment

196. Civil disobedience of “neutral” laws

197. Work-on without collaboration

198. Dual sovereignty and parallel government

Without doubt, a large number of additional methods have already been used but have not been classified, and a multitude of additional methods will be invented in the future that have the characteristics of the three classes of methods: nonviolent protest and persuasion, noncooperation and nonviolent intervention.

It must be clearly understood that the greatest effectiveness is possible when individual methods to be used are selected to implement the previously adopted strategy. It is necessary to know what kind of pressures are to be used before one chooses the precise forms of action that will best apply those pressures.

[1] Boston: Porter Sargent, 1973 and later editions.

Featured image: General strike in Catalonia in February 2019. Photo by Òmnium Cultural, CC-BY-SA 2.0.