by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jul 28, 2015 | Climate Change, Lobbying, Strategy & Analysis

By Thomas Linzey / CELDF

Four years ago, as we were leaving Spokane to help rural Pennsylvania communities stop frack injection wells and gas pipelines, this region’s environmental groups couldn’t stop talking about “stopping the coal trains.”

After people in British Columbia – including NASA’s top climate scientist James Hansen – were arrested for blocking oil trains; and after people in Columbia County, Oregon have now proposed a countywide ban on new fossil fuel trains, one would think that both the Spokane City Council and the region’s environmental groups would have begun to take strong steps here to, well, actually stop the coal trains.

After all, there is now almost universal agreement that the continued use of fossil fuels threatens almost every aspect of our lives – from scorching the climate to acidifying the oceans and fomenting widespread droughts.

But it seems that both the Council and this region’s environmental groups have resigned themselves to being silent accomplices to this slow-moving disaster.

A few weeks ago, at a forum on coal and oil trains, rather than propose a citywide ban on oil and coal trains, those groups instead focused on the dangers of train derailments and coal dust – two real issues to be sure – but ones that fall completely short of recognizing the underlying problems posed by the trains.

If the problem is derailments and dust, then the solution is to reinforce and cover the railroad cars. That may or may not happen, but even if it does, it doesn’t solve the fundamental problem posed by the coal and oil trains. Instead, such a stance broadcasts the message from the City of Spokane and this region’s environmental groups that the coal and oil trains are okay as long as they are “safe.”

The real problem, of course, is that the fossil fuels that the oil and coal trains carry – when used the way they are intended to be used – can never be made “safe” because their guaranteed combustion is slowly boiling the very planet on which we live.

At the end of Spokane City Council President Ben Stuckart’s presentation at the forum last week, he spoke about his dead-end meetings with state and federal officials, whose doors were open to the energy and railroad corporations but not to communities affected by the trains. Stuckart declared that he wasn’t sure that anything short of laying down on the tracks would stop the coal and oil trains.

For one brief shining moment, it seemed that the heavens had parted and what we’re really up against – a governmental system controlled by the very corporations it is ostensibly supposed to regulate – came shining through.

As I watched, people across the room began to shout and applaud; and then, just as quickly as it had come, it passed, as the hosts of the forum steered everyone back to their latest moving target – this time, urging people to write letters begging Governor Inslee to stop proposed oil and gas exports. In other words, now nicely asking the Governor to stop more oil and coal trains from invading Spokane.

I then realized why I stopped going to those gatherings – I stopped because the form of activism proposed by the groups actually strips us of the belief that we’re capable of doing anything by ourselves, as a community, to actually stop the trains. Writing letters reinforces a hopelessness of sorts – that we’re completely dependent on the decision by others to “save” us, and that we’re incapable of taking action to save ourselves.

It would be akin to the civil rights movement writing letters to congress instead of occupying the lunch counter or the seats at the front of the bus. Or Sam Adams sending a letter to King George urging him to put safety bumpers on the ships carrying tea, rather than having a tea party by dumping casks of tea in the harbor.

Until we confront the energy and railroad corporations directly, they will continue to treat Spokane as a cheap hotel. We need to ban and stop the trains now – using everything that we can – before future generations wonder why we spent so much time sending letters and so little time protecting them.

Thomas Alan Linzey, Esq., is the Executive Director of the Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund and a resident of the City of Spokane. The Legal Defense Fund has assisted over two hundred communities across the country, including the City of Pittsburgh, to adopt local laws stopping corporate factory farms, waste dumping, corporate water withdrawals, fracking, and gas pipelines. He is a cum laude graduate of Widener Law School and a three-time recipient of the law school’s public interest law award. He has been a finalist for the Ford Foundation’s Leadership for a Changing World Award, and is a recipient of the Pennsylvania Farmers Union’s Golden Triangle Legislative Award. He is admitted to practice in the United States Supreme Court, the Third, Fourth, Eighth, and Tenth Circuit Courts of Appeals, the U.S. District Court for the Western and Middle Districts of Pennsylvania, and the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Linzey was featured in Leonardo DiCaprio’s film 11th Hour, assisted the Ecuadorian constitutional assembly in 2008 to adopt the world’s first constitution recognizing the independently enforceable rights of ecosystems, and is a frequent lecturer at conferences across the country. His work has been featured in the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, Mother Jones, the Nation magazine, and he was named, in 2007, as one of Forbes’ magazines’ “Top Ten Revolutionaries.” He can be reached at tal@pa.net.

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Jun 22, 2015 | Building Alternatives, Gender, Strategy & Analysis

In 1993 Michael Carter was arrested and indicted for underground environmental activism. Since then he’s worked aboveground, fighting timber sales and oil and gas leasing, protecting endangered species, and more. Today, he’s a member of Deep Green Resistance Colorado Plateau, and author of the memoir Kingfishers’ Song: Memories Against Civilization.

Time is Short spoke with him about his actions, underground resistance, and the prospects and problems facing the environmental movement. The first part of this interview is available here, and the second part here.

Time is Short: You mentioned some problems of radical groups—lack of respect for women and lack of a strategy. Could you expand on that?

Michael Carter: Sure. To begin with, I think both of those issues arise from a lifetime of privilege in the dominant culture. Men in particular seem prone to nihilism; I certainly was. Since we were taught—however unwittingly—that men are entitled to more of everything than women, our tendency is to bring this to all our endeavors.

I will give some credit to the movie “Night Moves” for illustrating that. The men cajole the woman into taking outlandish risks and they get off on the destruction, and that’s all they really do. When an innocent bystander is killed by their action, the woman has an emotional breakdown. She’s angry with the men because they told her no one would get hurt, and she breaches security by talking to other people about it. Their cell unravels and they don’t even explore their next options together. Instead of providing or even offering support, one of the men stalks and ultimately kills the woman to protect himself from getting caught, then vanishes back into mainstream consumer culture. So he’s not only a murderer but ultimately a cowardly hypocrite, as well.

Honestly, it appears to be more of an anti-underground propaganda piece than anything. Or maybe it’s just a vapid film, but it does have one somewhat valid point—that we white Americans, particularly men, are an overprivileged self-centered lot who won’t hesitate to hurt anyone who threatens us.

Artwork by Stephanie McMillan

That’s a fictional example, but any female activist can tell you the same thing. And of course misogyny isn’t limited to underground or militant groups; I saw all sorts of male self-indulgence and superiority in aboveground circles, moderate and radical both. It took hindsight for me to recognize it, even in myself. That’s a central problem of radical environmentalism, one reason why it’s been so ineffective. Why should any woman invest her time and energy in an immature movement that holds her in such low regard? I’ve heard this complaint about Occupy groups, anarchists, aboveground direct action groups, you name it.

Groups can overcome that by putting women in positions of leadership and creating secure, uncompromised spaces for them to do their work. I like to reflect on the multi-cultural resistance to the Burmese military dictatorship, which is also a good example of a combined above- and underground effort, of militant and non-violent tactics. The indigenous people of Burma traditionally held women in positions of respect within their cultures, so they had an advantage in building that into their resistance movements, but there’s no reason we couldn’t imitate that anywhere. Moreover, if there are going to be sustainable and just cultures in the future, women are going to be playing critical roles in forming and running them, so men should be doing everything possible to advocate for their absolute human rights.

As for strategy, it’s a waste of risk-taking for someone to cut down billboards or burn the paint off bulldozers. It’s important not to equate willingness with strategy, or radicalism and militancy with intelligence. For example, I just noticed an oil exploration subcontractor has opened an office in my town. Bad news, right? I had a fleeting wish to smash their windows, maybe burn the place down. That’ll teach ‘em, they’ll take us seriously then. But it wouldn’t do anything, only net the company an insurance settlement they’d rebuild with and reinforce the image of militant activists as mindless, dangerous thugs.

If I were underground, I’d at least take the time to choose a much more costly and hard-to-replace target. I’d do everything I could to coordinate an attack that would make it harder for the company to recover and continue doing business. And I’d only do these things after I had a better understanding of the industry and its overall effects, and a wider-focused examination of how that industry falls into the mechanism of civilization itself.

By widening the scope further, you see that ending oil and gas development might better be approached from an aboveground stance—by community rights initiatives, for example, that have outlawed fracking from New York to Texas to California. That seems to stand a much better chance of being effective, and can be part of a still wider strategy to end fossil fuel extraction altogether, which would also require militant tactics. You have to make room for everything, any tactic that has a chance of working, and begin your evaluation there.

To use the Oak Flat copper mine example, now the mine is that much closer to happening, and the people working against it have to reappraise what they have available. That particular issue involves indigenous sacred sites, so how might that be respectfully addressed, and employed in fighting the mine aboveground? Might there be enough people to stop it with civil disobedience? Is there any legal recourse? If there isn’t, how might an underground cell appraise it? Are there any transportation bottlenecks to target, any uniquely expensive equipment? How does timing fit in? How about market conditions—hit them when copper prices are down, maybe? Target the parent company or its other subsidiaries? What are the company’s financial resources?

An underground needs a strategy for long-term success and a decision-making mechanism that evaluates other actions. Then they can make more tightly focused decisions about tactics, abilities, resources, timing, and coordinated effort. The French Resistance to the Nazis couldn’t invade Berlin, but they sure could dynamite train tracks. You wouldn’t want to sabotage the first bulldozer you came across in the woods; you’d want to know who it belonged to, if it mattered, and that you weren’t going to get caught. Maybe it belongs to a habitat restoration group, who can say? It doesn’t do any good to put a small logging contractor out of business, and it doesn’t hurt a big corporation to destroy machinery that is inexpensive, so those questions need to be answered beforehand. I think successful underground strikes must be mostly about planning; they should never, never be about impulse.

TS: There are a lot of folks out there who support the use of underground action and sabotage in defense of Earth, but for any number of reasons—family commitments, physical limitations, and so on—can’t undertake that kind of action themselves. What do you think they can do to support those willing and able to engage in militant action?

MC: Aboveground people need to advocate underground action, so those who are able to be underground have some sort of political platform. Not to promote the IRA or its tactics (like bombing nightclubs), but its political wing of Sinn Fein is a good example. I’ve heard a lot of objections to the idea of advocating but not participating in underground actions, that there’s some kind of “do as I say, not as I do” hypocrisy in it, but that reflects a misunderstanding of resistance movements, or the requirements of militancy in general. Any on-the-ground combatant needs backup; it’s just the way it is. And remember that being aboveground doesn’t guarantee you any safety. In fact, if the movement becomes effective, it’s the aboveground people most vulnerable to harm, because they’re going to be well known. In that sense, it’s safer to be underground. Think of the all the outspoken people branded as intellectuals and rounded up by the Nazis.

The next most important support is financial and material, so they can have some security if they’re arrested. When environmentalists were fighting logging in Clayoquot Sound on Vancouver Island in the 1990s, Paul Watson (of the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society) offered to pay the legal defense of anyone caught tree spiking. Legal defense funds and on-call pro-bono lawyers come immediately to mind, but I’m sure that could be expanded upon. Knowing that someone is going to help if something horrible happens, combatants can take more initiative, can be more able to engineer effective actions.

We hope there won’t be any prisoners, but if there are, they must be supported too. They can’t just be forgotten after a month. As I mentioned before, even getting letters in jail is a huge morale booster. If prisoners have families, it’s going to make a big difference for them to know that their loved ones aren’t alone and that they will have some sort of aboveground material support. This is part of what we mean when we talk about a culture of resistance.

TS: You’ve participated in a wide range of actions, spanning the spectrum from traditional legal appeals to sabotage. With this unique perspective, what do you see as being the most promising strategy for the environmental movement?

MC: We need more of everything, more of whatever we can assemble. There’s no denying that a lot of perfectly legal mainstream tactics can work well. We can’t litigate our way to sustainability any more than we can sabotage our way to sustainability; but for the people who are able to sue the enemy, that’s what they should be doing. Those who don’t have access to the courts (which is most everyone) need to find other roles. An effective movement will be a well-organized movement, willing to confront power, knowing that everything is at stake.

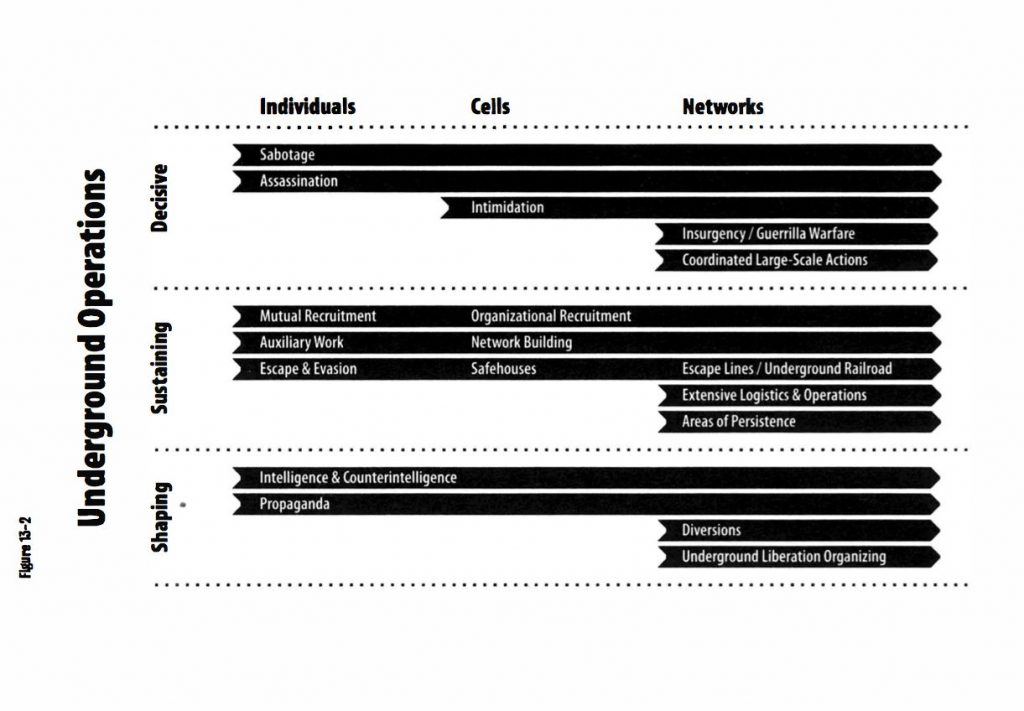

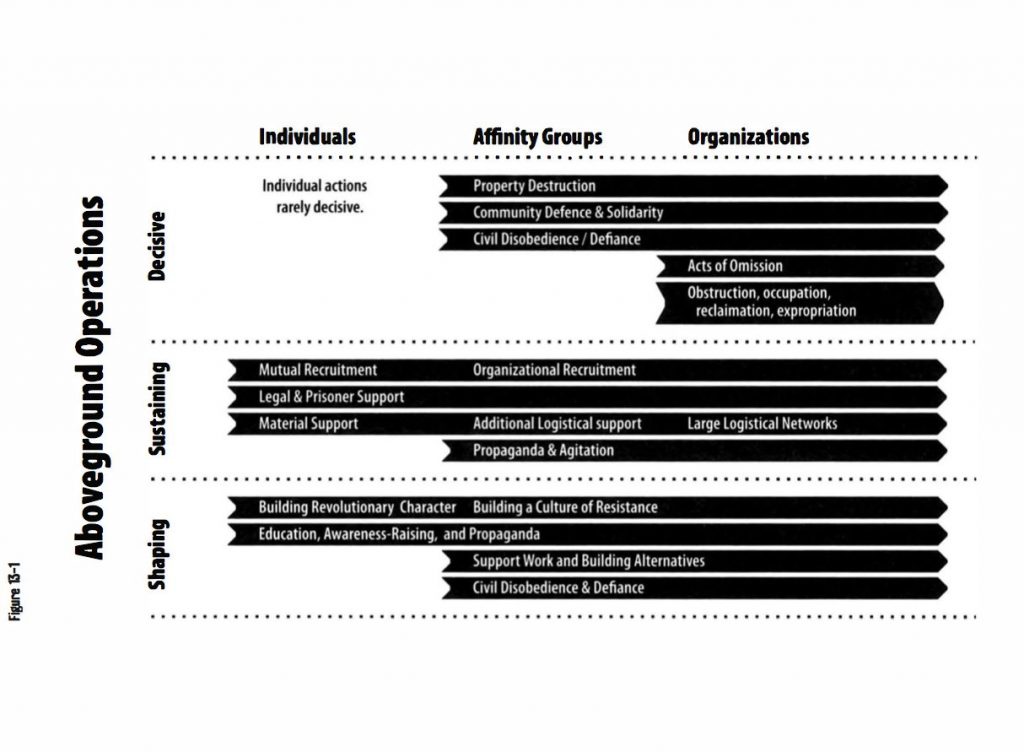

Decisive Ecological Warfare is the only global strategy that I know of. It lays out clear goals and ways of arranging above- and underground groups based on historical examples of effective movements. If would-be activists are feeling unsure, this might be a way for them to get started, but I’m sure other plans can emerge with time and experience. DEW is just a starting point.

Remember the hardest times are in the beginning, when you’re making inevitable mistakes and going through abrupt learning curves. When I first joined Deep Green Resistance, I was very uneasy about it because I still felt burned out from the ‘90s struggles. What I’ve discovered is that real strength and endurance is founded in humility and respect. I’ve learned a lot from others in the group, some of whom are half my age and younger, and that’s a humbling experience. I never really understood what a struggle it is for women, either, in radical movements or the culture at large; my time in DGR has brought that into focus.

Look at the trans controversy; here are males asking to subordinate women’s experiences and safe spaces so they can feel comfortable. It’s hard for civilized men to imagine relationships that aren’t based on the dominant-submissive model of civilization, and I think that’s what the issue is really about—not phobia, not exclusionary politics, but rather role-playing that’s all about identity. Male strength traditionally comes from arrogance and false pride, which naturally leads to insecurity, fear, and a need to constantly assert an upper hand, a need to be right. A much more secure stance is to recognize the power of the earth, and allow ourselves to serve that power, not to pretend to understand or control it.

TS: We agree that time is not on our side. What do you think is on our side?

TS: We agree that time is not on our side. What do you think is on our side?

MC: Three things: first, the planet wants to live. It wants biological diversity, abundance, and above all topsoil, and that’s what will provide any basis for life in the future. I think humans want to live, too; and more than just live, but be satisfied in living well. Civilization offers only a sorry substitute for living well to only a small minority.

The second is that activists now have a distinct advantage in that it’s easier to get information anonymously. The more that can be safely done with computers, including attacking computer systems, the better—but even if it’s just finding out whose machinery is where, how industrial systems are built and laid out, that’s much easier to come by. On the other hand the enemy has a similar advantage in surveillance and investigation, so security is more crucial than ever.

The third is that the easily accessible resources that empires need to function are all but gone. There will never be another age of cheap oil, iron ore mountains, abundant forest, and continents of topsoil. Once the infrastructure of civilized humanity collapses or is intentionally broken, it can’t really be rebuilt. Then humans will need to learn how to live in much smaller-scale cultures based on what the land can support and how justly they treat one another. That will be no utopia, of course, but it’s still humanity’s best option. The fight we’re now engaged in is over what living material will be available for those new, localized cultures—and more importantly, the larger nonhuman biological communities—to sustain themselves. What polar bears, salmon, and migratory birds need, we will also need. Our futures are forever linked.

Time is Short: Reports, Reflections & Analysis on Underground Resistance is a bulletin dedicated to promoting and normalizing underground resistance, as well as dissecting and studying its forms and implementation, including essays and articles about underground resistance, surveys of current and historical resistance movements, militant theory and praxis, strategic analysis, and more. We welcome you to contact us with comments, questions, or other ideas at undergroundpromotion@deepgreenresistance.org

by DGR News Service | Dec 19, 2014 | Culture of Resistance, Education

Will Falk / Deep Green Resistance

originally published at Generation Alpha

The proper cure requires the proper diagnosis.

On November 22 and 23, the Fertile Ground Environmental Institute offered the proper diagnosis for the ecological crises we all face to over 700 attendees at Earth at Risk 2014. Focusing on environmental and social justice, the conference brought together seemingly disparate voices to weave together diverse perspectives to offer a comprehensive response to global destruction. The keynote speakers were Vandana Shiva, Alice Walker, Chris Hedges, Thomas Linzey, and Derrick Jensen.

Shiva detailed how multi-national corporations like Monsanto and DuPont are using genetically modified organisms (GMO) to undermine local communities’ ability to produce their own food. Walker shared her experiences as a Pulitzer Prize winning author to give an artist’s perspective for the necessity of solidarity with women. Hedges drew upon nearly two decades as a foreign war correspondent to argue for the moral imperative of resistance to topple industrial civilization. Linzey, an attorney, illustrated how citizens come to him asking for help drafting ordinances against fracking and are converted into revolutionary cadre when they learn through the legal system that they do not live in a democracy. Jensen addressed the question “Why are so few of us fighting back?” with an explanation that most of us in this culture are suffering from complex post-traumatic stress disorder.

Time is short and Earth at Risk displayed the appropriate urgency in the face of total environmental destruction. Studies around the world confirm what we feel in our hearts to be true. A recent study by the World Wildlife Fund and the Zoological Society of London shows that half the world’s population of wild animals has died off since 1970. This is consistent with the findings of the University College of London showing insect populations crashing 50 percent in the last 35 years. Human destruction is necessarily implicated in the death of the natural world. We know, for example, dioxin – a known carcinogen – is now found in every mother’s breast milk.

A mere conference is insufficient to stop the madness, but Earth at Risk offered the most complete examination the movement has seen to date offering six panel discussions to go with the five keynote speakers. The first day was devoted to sustainability and featured panel discussions titled Colonization and Indigenous Life, Indicators of Ecological Collapse, and Building Resistance Communities. The second day was devoted to social justice with panels covering Capitalism and Sociopathology; Race, Militarism, and Masculinity; and Confronting Misogyny.

Personal Reflections

In a world gone mad, there are simply too few resisters struggling on. This is one of the reasons we are losing so badly. I left Earth at Risk feeling that patriarchy, colonialism, and capitalism are the most serious threats to a living world. To save the world, alliances must be built on all fronts. While our movements remain relatively small, strength can be maximized in this way.

Earth at Risk’s speakers illuminated opportunities for coalition building and pointed out weak spots in the system ripe for targeting. There were too many highlights to document in one article, but my favorite moments included native Hawaiian filmmaker Anne Keala Kelly’s stinging remarks on the colonization of Hawaii and implorations for real decolonizing help from the mainland during the Colonization and Indigenous Life panel. Fighting for Hawaiian sovereignty would necessarily involve undermining the United States’ military presence there. Hawaii is the site of the United States’ Pacific Command that polices over half the world’s population.

During the Building Communities of Resistance panel, Mi’kmaw warrior Sakej Ward described how native warrior societies protect land bases so they may support the next seven generations. He drew attention to the 500 years of experience North American indigenous peoples have in resisting colonization and offered this experience as a valuable resource.

I was deeply moved by the entire conversation during the Race, Militarism, and Masculinity panel where military veterans Kourtney Mitchell, Vince Emanuele, Stan Goff, and Doug Zachary called on men to topple the patriarchy, stop rape, and support women with actions instead of words.

I attended the conference as a director of the Vancouver Island Community Forest Action Network (VIC FAN) in support of Unist’ot’en clan spokeswoman Freda Huson and Wet’suwet’en hereditary chief Dini Ze Toghestiy who spoke on the Building Communities of Resistance panel about their experiences at the Unist’ot’en Camp. The Unist’ot’en Camp occupies the unceded territory of the Unist’ot’en Clan of the Wet’suwet’en people and is a pipeline blockade sitting on the proposed routes of 17 fossil fuel pipelines in central British Columbia.

My visits to the Unist’ot’en Camp have taught me the strength in connecting the rationales for different social and environmental movements under one banner. It has also taught me how to think strategically. The Camp, as just one of many examples present at Earth at Risk, incorporates principles of indigenous sovereignty and environmentalism to bring activists from both communities together to combat imperialism and fossil fuels. More importantly, perhaps, the Camp demonstrates how a handful of volunteers can effectively neutralize huge, multi-corporate projects by focusing physical strength on chokepoints in industrial infrastructure. From a strategic perspective, the military-industrial complex wrecking the world runs on fossil fuels. Corking the fossil fuels would be a grievous blow to the dominant culture’s ability to continue business as usual.

Additionally, I am a member of the worldwide social and environmental justice organization Deep Green Resistance (DGR) based on the strategy developed by Lierre Keith, Derrick Jensen, and Aric McBay in the book Deep Green Resistance. DGR played a large role organizing the event. Keith brilliantly points out that, “Militarism is a feminist issue. Rape is an environmental issue. Environmental destruction is a peace issue.”

Hearing Kourtney Mitchell explain how his education in pro-feminism enabled to him to overcome the inherently abusive training he received as an infantry soldier in Georgia’s National Guard proved this to me. When Derrick Jensen was confronted for describing the destruction of the natural world in terms of rape and sexual violence and he refused to stop making the connection on grounds that both hinge on men’s perceived entitlement to violation, I understood that radical feminists and radical environmentalists were logical allies. Finally, hearing Richard Manning explain how dire the world’s lack of topsoil has become drove the point home that those of us sick of war would do well to defend the land’s ability to support food.

Finally, the Earth at Risk 2014 website promised to craft “game-changing responses to address the converging crises we face.” The conference successfully fulfilled its promise. The truth is we simply do not have the numbers to mount an effective resistance movement without forming coalitions between groups serious about stopping the murder of the planet and other humans.

I wrote earlier that a conference is insufficient to stop the madness. This is still true, but Earth at Risk 2014 accurately analyzed the world’s sicknesses and gave us a treatment plan to work from. Now, it’s time for all of those fighting so hard in our various causes to link up in solidarity to bring down the patriarchy, stop capitalism, and undermine the colonialism that is killing humans and obliterating the natural world.

by DGR News Service | Sep 6, 2014 | Agriculture, Education, Lobbying

By Norris Thomlinson / Deep Green Resistance Hawai’i

Open Sesame examines the importance of seeds to humans as the genesis of nearly all our domesticated foods. It details the tremendous loss in varietal diversity of our crops over the last century, due in large part to increasing corporate control over the seed market.

Farmers and gardeners in every region once had access to dozens of varieties of each vegetable and staple crop, finely adapted to the specific growing season, temperatures, rainfall patterns, insects, diseases, and soils of their area. With few people now saving their own seed, we’ve entrusted our food supply to a handful of seed companies selling the same handful of varieties to growers across the US. This will prove increasingly problematic as climate chaos increases divergence from climatic norms. We need a return to seed saving and breeding of numerous local varieties, each starting from a baseline adaptation to the specific conditions of each area. Diversity gives a better chance of avoiding complete catastrophic crop failure; this variety may yield in the heavy rains of one year, while that variety may succeed in the drought of the next.

The film shows beautiful time lapse sequences of seeds sprouting and shooting into new life. Even rarer, it shows people feeling very emotional about seeds, displaying extra-human connections we normally only see with domesticated pets, and hinting at the human responsibility of respectful relationship with all beings described by so many indigenous people. The movie highlights great projects from seed schools and the Seed Broadcast truck educating people on why and how to save seed, to William Woys Weaver and others within Seed Savers Exchange doing the on-the-ground work of saving varieties from extinction, to Hudson Valley Seed Library trying to create a viable business as a local organic seed company.

Civilization and Agriculture

Unfortunately, Open Sesame has an extremely narrow focus. Though it rightly brings up the issue of staple crops, which many people ignore in their focus on vegetables, it trumpets our dependence on grains, even showing factory farmed cattle, pigs, and chickens in an uncritical light. This assumption that humans need annual crops reveals an ignorance of agriculture itself as a root cause of our converging environmental crises. Even before industrialism accelerated the destruction and oppression, civilization and its cities, fed by organic agriculture, was eroding soil, silting up waterways, turning forests into deserts, and instituting slavery and warfare. Though the diminished diversity within our food crops should indeed cause concern, the far greater biodiversity loss of mass species extinctions under organic agriculture should spark great alarm, if not outright panic.

In one scene, the documentary shows a nighttime urban view of industrial vehicles and electric lights, bringing to mind the planetary destruction enacted by the creation and operation of these technologies. Beneath the surface, this scene contains further social and imperialistic implications of packing humans into artificial and barren environments. The residents of this scene are fully reliant on imported food and other resources, often stolen directly, and all grown or mined from land stolen from its original human and non-human inhabitants. But the film goes on to point out, without any irony, that all civilizations began with humans planting seeds, as if the only problem we face now is that industrialization and corporate control applied to agriculture threaten the stability of otherwise beneficial systems.

In a similar disconnect, Open Sesame proclaims the wonders of gardening, farming, and “being in nature” while showing simplified ecosystem after simplified ecosystem ― annual gardens and fields with trees present only in the background, if at all. As any student of permaculture or of nature could tell you, the disturbed soil shown in these human constructions is antithetical to soil building, biodiversity, and sustainability. The film describes seeds “needing” our love and nurturing to grow, positioning us as stewards and playing dangerously into the dominating myth of human supremacism. Such dependence may (or may not) be true of many of our domesticated crops and animals, but I think it crucial to explicitly recognize that in indigenous cultures, humans are just one of many equal species living in mutual dependence.

Though the documentary chose not to tackle those big-picture issues, it still could have included perennial polycultures, groups of long-lived plants and animals living and interacting together in support of their community. For 99% of our existence, humans met our needs primarily from perennial polycultures, the only method proven to be sustainable. The film could have chosen from hundreds of modern examples of production of vegetables, fruit, and staple foods from perennial vegetable gardens, food forests, and grazing operations using rotating paddocks. Even simplified systems of orchards and nutteries would have shown some diversity in food production options. Besides being inherently more sustainable in building topsoil and creating habitat, such systems rely much less on seed companies and help subvert their control.

Liberal vs Radical

The Deep Green Resistance Youtube Channel has an excellent comparison of Liberal vs Radical ways of analyzing and addressing problems. In short, liberalism focuses on individual mindsets and changing individual attitudes, and thus prioritizes education for achieving social change. Radicalism recognizes that some classes wield more power than others and directly benefit from the oppressions and problems of civilization. Radicalism holds these are not “mistakes” out of which people can be educated; we need to confront and dismantle systems of power, and redistribute that power. Both approaches are necessary: we need to stop the ability of the powerful to destroy the planet, and simultaneously to repair and rebuild local systems. But as a radical environmentalist, I found the exclusively liberal focus of Open Sesame disappointing. There’s nothing inherently wrong with its take on seed sovereignty; the film is good for what it is; and I’m in no way criticizing the interviewees doing such great and important work around seed saving and education. But there are already so many liberal analyses and proposed solutions in the environmental realm that this film’s treatment doesn’t really add anything new to the discussion.

A huge challenge I have with liberal environmentalism is its leap of logic in getting from here (a world in crisis) to there (a truly sustainable planet, with more topsoil and biodiversity every year than the year before.) Open Sesame is no exception: it has interview after interview of individuals carrying out individual actions: valuable, but necessarily limited. Gary Nabham speaks with relief on a few crop varieties saved from extinction by heroic individual effort, but no reflection is made on the reality of how much we’ve lost and the inadequacy of this individualist response. We see scene after scene of education efforts, especially of children. We’re left with a vague hope that more and more people will save their own seed, eventually leading to a majority reclaiming control over their plantings while the powerful agribusiness corporations just fade away. This ignores the institutional blocks deliberately put in place precisely by those powerful companies.

The only direct confrontation shown is a defensive lawsuit begging that Monsanto not be allowed to sue farmers whose crops are contaminated by patented GMOs from nearby fields. The lawsuit isn’t even successful, and the defeated farmers and activists are shown weary and dejected, but with a fuzzy determination that they can win justice if they keep trying hard enough. The film could instead have built on this example of the institutionalized power we’re up against and explored more radical approaches to force change. Still within the legal realm, CELDF (Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund) helps communities draft and pass ordinances banning things like factory farming, removing corporate personhood, and giving legal rights to nature within a municipality or county. Under such an ordinance, humans could initiate a lawsuit against agricultural operations leaching chemicals and sediment, on behalf of an impacted river. This radical redistribution of decision making directly confronts those in power and denies them the right to use it against the community and the land.

In the non-legal realm, underground direct attacks and aboveground nonviolent civil disobedience have successfully set back operations when people have cut down GMO papayas, burned GMO sugar beets, and sabotaged multiple fields and vineyards. The ultimate effectiveness of these attacks deserves a whole discussion in and of itself, but they would have been worth mentioning as one possible tactic for ending agribusiness domination of our food supplies.

In a perfect demonstration of the magical thinking that wanting something badly enough will make it happen, the documentary concludes with a succession of people chanting “Open sesame!” We’ve had 50 years of experience with this sort of environmentalism, long enough to know it’s not working. We also know that we, and the planet, have no time left to waste. We need to be strategic and smart in our opposition to perpetrators of destruction and in our healing of the damage already done. The Decisive Ecological Warfare strategy of Deep Green Resistance offers a possible plan for success, incorporating all kinds of people with all kinds of skills in all kinds of roles. If you care about the world and want to change where we’re headed, please read it, reflect on it, and get involved in whatever way makes the most sense for you.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 29, 2013 | Lobbying, Mining & Drilling

By Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund

Earlier today, the County Commission of Mora County, located in Northeastern New Mexico, became the first county in the United States to pass an ordinance banning all oil and gas extraction.

Drafted with assistance from the Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund (CELDF), the Mora County Community Water Rights and Local Self-Government Ordinance establishes a local Bill of Rights – including a right to clean air and water, a right to a healthy environment, and the rights of nature – while prohibiting activities which would interfere with those rights, including oil drilling and hydraulic fracturing or “fracking,” for shale gas.

Communities across the country are facing drilling and fracking. Fracking brings significant environmental impacts including the production of millions of gallons of toxic wastewater, which can affect drinking water and waterways. Studies have also found that fracking is a major global warming contributor, and have linked the underground disposal of frack wastewater to earthquakes.

CELDF Executive Director Thomas Linzey, Esq., explained, “Existing state and federal oil and gas laws force fracking and other extraction activities into communities, overriding concerns of residents. Today’s vote in Mora County is a clear rejection of this structure of law which elevates corporate rights over community rights, which protects industry over people and the natural environment.”

He stated further that, “This vote is a clear expression of the rights guaranteed in the New Mexico Constitution which declares that all governing authority is derived from the people. With this vote, Mora is joining a growing people’s movement for community and nature’s rights.”

CELDF Community Organizer and Mora County resident, Kathleen Dudley, added, “The vote of Mora Commission Chair John Olivas and Vice-Chair Alfonso Griego to ban drilling and fracking is not only commendable, it is a statement of leadership that sets the bar for communities across the State of New Mexico.” She explained that the ordinance calls for an amendment to the New Mexico Constitution that “elevates community rights above corporate property rights.”

Mora County joins Las Vegas, NM, which in 2012 passed an ordinance, with assistance from CELDF, which prohibits fracking and establishes rights for the community and the natural environment. CELDF assisted the City of Pittsburgh, PA, to draft the first local Bill of Rights which prohibits fracking in 2010. Communities in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Maryland, New York, and New Mexico have enacted similar ordinances.

Mora County joins over 150 communities across the country which have asserted their right to local self-governance through the adoption of local laws that seek to control corporate activities within their municipality.

From CELDF: