by DGR News Service | May 23, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Colonialism & Conquest, Education, Human Supremacy, Strategy & Analysis, The Problem: Civilization

This is part 4 of a series that originally appeared on ClimateandCapitalism. You can read part 1, part 2 and part 3.

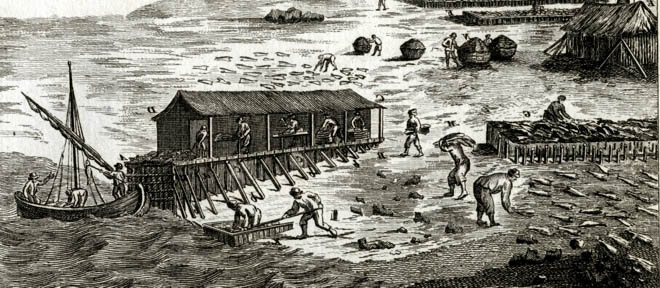

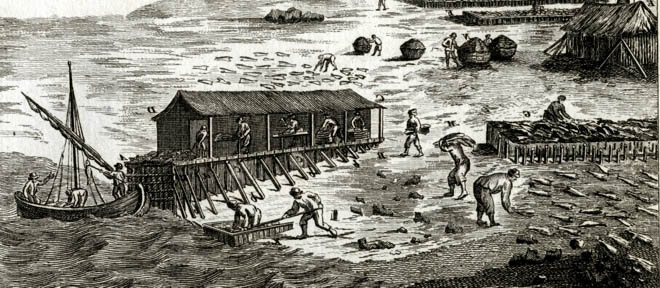

Featured image: Processing cod in a 16th Century Newfoundland ‘Fishing Room’

THE FISHING REVOLUTION

Centuries before the industrial revolution, the first factories transformed seafood production

By Ian Angus

Marxist historians have been debating the origin of capitalism since the 1940s. It is true, as Eric Hobsbawm once commented, that “nobody has seriously maintained that capitalism prevailed before the 16th century, or that feudalism prevailed after the late 18th,”[1] but despite years of vigorous discussion in many excellent books and articles, there is still no consensus on when, where and how the new system formed and became dominant.[2]

This article does not try to resolve the debate or propose a new grand narrative. My goal, rather, is to draw attention to an important aspect of early capitalism that has been almost entirely ignored by all of the participants: the development and growth of intensive fishing in the North Sea and northwestern Atlantic Ocean in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

‘An immense fishing enterprise’

As we will see, transatlantic fishing in the 1500s was one of the world’s first capitalist industries. But even if that were not true, recent research into its size and scope demonstrates its extraordinary importance to the economic history of that period.

Part Two of this article discussed the work of Selma Barkham, whose archival research documented the previously unknown large-scale Basque whaling operations in the Strait of Belle Isle.

Similarly, Laurier Turgeon of Laval University has shown that the transatlantic cod fishing industry was much larger than previously thought. His work, based on archival records in French port cities, documents “an immense fishing enterprise that has been largely overlooked in the maritime history of the North Atlantic.” In the second half of the sixteenth century, “the French Newfoundland vessels represented one of the largest fleets in the Atlantic. These 500 or so ships had a combined loading capacity of some 40,000 tons burden [56,000 cubic meters], and they mobilized 12,000 fishermen-sailors each year.”

To those must be added annual crossings by some 200 Spanish, Portuguese and English ships.

“The Newfoundland fleet surpassed by far the prestigious Spanish fleet that trafficked with the Americas, which had only half the loading capacity and half as many crew members…. The Gulf of the Saint Lawrence represented a site of European activity fully comparable to the Gulf of Mexico or the Caribbean. Far from being a marginal space visited by a few isolated fishermen, Newfoundland was one of the first great Atlantic routes and one of the first territories colonized in North America.”[3]

Historian Peter E. Pope reaches a similar conclusion in his award-winning study of early English settlements in Newfoundland:

“By the later sixteenth century, European commercial activity in Atlantic Canada exceeded, in volume and value, European trade with the Gulf of Mexico, which is usually treated as the American center of gravity of early transatlantic commerce … The early modern fishery at Newfoundland was an enormous industry for its time, and even for our own.[4]

In the same period, close to 1,000 ships sailed annually to the North Sea from Holland, Zeeland and Flanders. The Netherlands-based fishing industry was so important that Philip II used part of his American gold and silver to finance warships that protected the Dutch herring fleet from attacks by French and Scottish privateers.

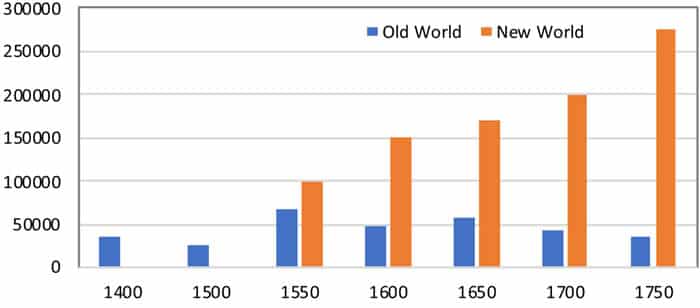

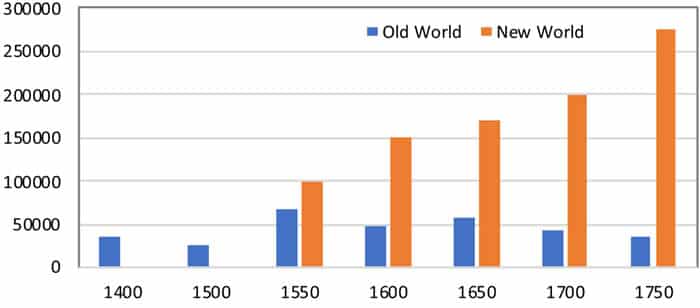

In the 1400s, the Dutch fleet in the North Sea caught and processed huge volumes of fish, making herring the most-widely consumed fish in northern Europe. In the 1500s, the North Sea herring catch remained stable while the Newfoundland fishery transformed the market — in 1580, Newfoundland fishers brought back 200,000 tonnes of cod, more than double the North Sea herring catch in its best year. By the end of the century, cod had replaced herring as the most important commodity fish in Europe, by a large margin. This graph shows the growth of herring and cod sold in continental Europe from 1400 to 1750.

Old and New World supplies (tonnes) of herring and cod to European market. (Source: Holm et al, “The North Atlantic Fish Revolution ca. AD 1500” Quaternary Research, 2018)

It is clear that in the 1500s intensive fishing became a major industry, an important component of the revolutionary social and economic changes then underway across Europe.

The first capitalist factories

In 1776, in the first chapter of The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith famously attributed the “greatest improvements in the productive powers of labor” to “the effects of the division of labor,” in what he called manufactories. In some pin-making establishments, for example, “about eighteen distinct operations … are all performed by distinct hands,” By dividing up the tasks, pin factories produced many times more pins than would have been possible if each worker made them individually.[5]

Less famous, perhaps, is the particular emphasis that Karl Marx placed on the importance of division of labor in manufacture, his term for “combining together different handicrafts under the command of a single capitalist” [6] before the introduction of machinery in the industrial revolution. “The division of labor in the workshop, as practiced by manufacture, is an entirely specific creation of the capitalist mode of production.”[7]

A recent book claims that production by division of labor was invented in the 1470s, on Portuguese sugar plantations on the island of Madeira. The assignment of different activities to different groups of slaves shows, the authors say, that “the plantation was the original factory.”[8]

While that was an important development, it was not the first case of factory food production. Over half a century earlier, as we saw in Part One, Dutch merchants, shipbuilders, and fishworkers introduced a sophisticated division of labor to produce food in much greater volume — not a luxury product like sugar, but a mass commodity, seafood. The large, broad-bottomed herring busses, in which teams of workers captured, processed and preserved fish in the North Sea, have a strong claim to being the first capitalist factories.

French fishers used similar vessels, called bankers or bank ships, on Newfoundland’s Grand Banks in the 1500s. Laurier Turgeon describes a typical division of labor in “the precursor of our factory ships,” as the cod were hooked and hauled up:

“All eviscerating or dressing operations were carried out on deck where activity had turned well and truly into assembly-line production. The ship’s boys grabbed the fish [from one of the fishers] and threw it onto the splitting-table. The ‘header’ severed the head, gutted it, and in the very same movement, pushed it towards the ‘splitter’ at the opposite end of the table. Two or three deft strokes of the knife sufficed to remove the backbone, after which the ‘dressed’ filet dropped down the hatch into the ship’s hold. There, the salter laid it out between two thick layers of salt.”

Work continued apace from dawn to dark, even overnight when the catch was particularly good. Every bank ship was “a workshop for the preparation and curing of fish” and the workers’ activity “resembled 19th-century factory labor in many respects.”[9]

The inland cod fishery also involved an assembly-line division of labor, in facilities built each year on Newfoundland’s stony beaches. A journal kept by ship’s surgeon James Yonge in the 1600s, summarized here by historian Peter Pope, describes the factory-like operation of Newfoundland fishing stations, called fishing rooms by English fishworkers.

“If fishing was good, the crews would head for their fishing rooms in late afternoon, each boat with as many as one thousand or twelve hundred fish, weighing altogether several tonnes. … The shore crews began the task of making fish right on the stage head, the combination wharf and processing plant where the fish was unloaded. A boy would lay the fish on a table for the header, who gutted and then decapitated the fish…. The cod livers were set aside and dumped into a train vat, where the oil rendered in the sun. The header pushed the gutted fish across the table to the splitter, who opened the fish and removed the spine…. Untrained boys moved the split fish in handbarrows and piled it up for an initial wet-salting. This salting required experience and judgment, as Yonge stressed: ‘A salter is a skillful officer, for too much salt burns the fish and makes it break, and wet, too little makes it redshanks, that is, look red when dried, and so is not merchantable.’ …

“After a few days in salt, the shore crews would rinse the fish in seawater and pile it on a platform of beach stones, called a horse, for a day or two before spreading it out to dry on a cobble beach or on flakes, rough wooden platforms covered with fir boughs or birch bark….. At night and in wet weather, the fish being processed had to be turned skin side up or collected in protected heaps. After four or five days of good weather, it was ready to be stored in carefully layered larger piles containing about fifteen hundred fish.”[10]

On long beaches, there could be multiple fishing rooms with workers from many ships in close proximity. As Pope writes, “This sophisticated division of labor, the large size of the production unit, together with the time discipline imposed by a limited fishing season gave the dry fishery some of the qualities of later manufacturing industries.”[11]

The sixteenth century fishing rooms and bank ships were factories, long before the industrial revolution.

‘A distinctly capitalist institution’

In Capital, Marx argues that merchant activity as such — buying cheap in one place and selling dear in another — did not undermine the feudal mode of production, nor did craftsmen who made and sold their own products. It was the integration of manufacture and trade that laid the basis for a new social order: “the production and circulation of commodities are the general prerequisites of the capitalist mode of production.”[12] The actual transition to capitalism, he wrote, occurred in three ways: some merchants shifted into manufacturing; some merchants contracted with multiple independent craftsmen; and some craftsmen expanded their operations to produce for the market themselves.[13]

But, as Maurice Dobb comments in Studies in the Development of Capitalism, the problem with schematic transition schemas, including Marx’s, is that the actual process was “a complex of various strands, and the pace and nature of the development differ widely in different countries.”[14]

For example, Selma Barkham found that Basque whaling expeditions to Labrador were organized and financed by what she calls money-men: “men with a solid financial background, and a good deal of experience, both in money-raising and in the insurance industry.”[15]

In England, on the other hand, as Gillian Cell shows, the Newfoundland fishery was “run by men of limited capital … [It] was primarily the preserve of the west-countrymen,” not London’s merchant grandees, and certainly not money-men. The largest capital expense, the ship itself, was typically shared among several investors. “Most commonly a ship would be divided into thirty-two parts, any number of which might be owned by the same merchant, but on occasion there might be as many as sixty-four.” In other cases, investors reduced their cost and risk by leasing ships, with no payment due until they returned.[16]

The investors hired a captain who hired the sailors and fishers, and contracted with a victualler who provided fishing gear, boats, barrels, salt, and other essentials, including food and drink for a long voyage. One person might play multiple roles — the captain and victualler might also be investors, for example.

A capitalist enterprise requires capital; it also requires workers. The very existence of intensive fishing in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries shows that there were thousands of men and boys in England and western Europe whose livelihood depended on working in the distant fishing factories.

It was arduous and dangerous work that took them away from home for most of the year. Just travelling to and from the fishing grounds took a month or more each way, in crowded wooden ships that might sink at any time. Maritime historian Samuel Elliot Morrison described the sixteenth century Newfoundland fishery as “a graveyard of ships” — more merchant ships were lost at sea in the years 1530-1600 than in all of World War II.[17]

And yet captains apparently had no difficulty in recruiting full crews of skilled and unskilled workers every year.

Little research has been done on the social origins of these workers, but it is surely significant that the rapid expansion of long-distance fishing in England in the 1500s coincided with a wave of rural enclosures and consolidation, in which “the traditional peasant community was undermined as layers of better-off peasants became wealthy yeoman farmers, some entering the ranks of the gentry, while others were pauperized and proletarianized — and on a massive scale.”[18] In the long sixteenth century (roughly 1450 to 1640), “great masses of men [were] suddenly and forcibly torn from their means of subsistence, and hurled onto the labor-market as free, unprotected and rightless proletarians.”[19]

In the Netherlands in the mid-1500s, about five percent of the male population worked in the herring industry.[20] There, and in England, France and Spain, a growing number of men who had formerly supplemented their diet and income with occasional fishing now had to work for others — having lost their land, they turned to the sea full time. Some may still have owned small plots of land and others probably worked as agricultural laborers between voyages, but all were part of a new maritime working class whose labor enriched a rising class of merchant-industrialists.

As we saw in Part One, workers on Dutch herring busses were often paid fixed wages. That was rare on English and French ships: usually, the gross proceeds from selling the catch were divided in three — one-third for the investors, one-third for the victualler, and one-third for the captain and crew. The captain took the largest part of the crew’s share, while workers received different amounts depending on their skill and experience, with laborers and boys receiving the least. Share payment reduced the investors’ losses when the catch was small or lost. It was also a form of labor discipline: as an English merchant wrote, because the fisherworkers’ income depended on the size of the catch, there was “lesse feare of negligence on their part.”[21]

From a purely legal standpoint, the merchants, shipowners, victuallers and fishworkers on each expedition were part of a joint venture, but as Daniel Vickers writes, that formality did not change the fundamental class relationship.

“Relations between merchants and their men remained in substance those of capital and labor. Merchants still garnered the lion’s share of the profits (and bore most of the losses); they retained complete ownership of the vessel, provisions, and gear throughout the voyage; and they could do with their capital what they wished once the fish had been sold. By early modern standards of economic organization, this transatlantic fishery was a distinctively capitalist institution.”[22]

Ecological Impact

Beginning in the early 1600s, a few English mariners sailed an additional 900 miles or so from Newfoundland to the area now known as New England. All were astonished by the abundance of fish — and especially by their size.

- John Brereton, 1602: “Fish, namely Cods, which as we encline more unto the South, are more large and vendible for England and France than the Newland fish.”

- James Rosier, 1605: Compared to Newfoundland cod, New England cod were “so much greater, better fed, and abundant with traine [oil]” and “all were generally very great, some they measured to be five foot long, and three foot about.”

- Robert Davies, 1607: “Hear wee fysht three howers & tooke near to hundred of Codes very great & large fyshe bigger & larger fyshe then that which coms from the bancke of the new Foundland.”[23]

Newfoundland and New England cod are separated by geography, but they are the same species. The difference in size and abundance wasn’t caused by genetics, but by a century of intensive fishing. Marine biologist Callum Roberts explains:

“By the time of these voyages, Newfoundland cod had been intensively exploited for a hundred years, and fishing there had evidently already had an impact on fish numbers and size. Catching fish reduces their average life span. Since fish like cod continue growing throughout their life span, fishing therefore reduces the average size of individuals in a population. The Newfoundland fishery had driven down the average size of cod, and the relatively unexploited stocks in New England became a reminder of the past.”[24]

A recent study estimates that until the late 1800s the annual catch was less than 10% of the total cod population[25], far below the level deemed sustainable in the twentieth century. That, together with the fact that the catch increased, year after year, seems to imply that in the early modern fishing had little or no impact, but that is misleading, because the total cod population was composed of distinct local populations. Since fishing operations tended to stay in areas where fish congregated, local cod populations could be, and were, diminished by intensive fishing.

By 1600, for example, in the area known as the English shore, “fishers made, on average, only about 60 percent of the catch per boat that they had come to expect.”[26] The total catch remained high because some fishers worked harder, using more boats or staying at sea longer, while others shifted geographically, targeting less depleted populations as far away as the aptly named Cape Cod in Massachusetts.

“As human fishing removed larger, more mature fish from each substock, the chances of abrupt swings in the reproductive rate increased. In short, even at the seemingly ‘moderate’ levels of the 1600s and 1700s, fishing altered the age (and perhaps gender) structures, size, weight, and spawning and feeding habits, and the overall size of codfish stocks in the North Atlantic.”[27]

Cod are among the most prolific vertebrates on earth. Mature females release 3 to 9 million eggs a year: someone once calculated that if they all grew to maturity, in three years it would be possible to walk across the ocean in their backs. In reality, only a few hatch and few of those avoided being eaten as larvae, but under normal conditions (i.e. before intensive fishing) enough survived to maintain a stable population in the trillions. Intensive fishing disrupted that metabolic and reproductive cycle, but the total number of cod was so great that it took nearly five centuries for the world’s largest fishery to collapse.

A Fishing Revolution

In 2018, a team of environmental historians led by Poul Holm proposed that the birth and rapid growth of intensive fishing in Newfoundland should be called the Fish Revolution. A careful study of the fishery’s size, its impact on European markets and diets, and its environmental effects led them to conclude that historians “have grossly underestimated the historical economic significance of the fish trade, which may have been equal to the much more famed rush to exploit the silver mines of the Incas.” The Fish Revolution was “a major event in the history of resource extraction and consumption. … [that] permanently changed human and animal life in the North Atlantic region.”

“The wider seafood market was transformed in the process, and the marine expansion of humans across the North Atlantic was conditioned by significant climatic and environmental parameters. The Fish Revolution is one of the clearest early examples of how humans can affect marine life on our planet and of how marine life can in return influence and become, in essence, a part of a globalizing human world.”[28]

That conclusion synthesizes a large body of recent research. It is, I think, absolutely correct as far as it goes, but it needs to be supported a deeper understanding of the social and economic drivers of change. In brief, the Fish Revolution was caused by a Fishing Revolution.

The success of the North Sea and Newfoundland fisheries depended on merchants who had capital to invest in ships and other means of production, fishworkers who had to sell their labor power in order to live, and a production system based on a planned division of labor. It would not have been possible in the Middle Ages, because none of those elements existed. The long-distance fishing operations of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries were among the first examples, and very likely the largest examples, of what Marx called manufacture — “a specifically capitalist form of the process of social production.”[29]

In the Fishing Revolution, capital in pursuit of profit organized human labor to turn living creatures into an immense accumulation of commodities. From 1600 on, up to 250,000 metric tonnes of cod a year were caught, processed, and preserved in Newfoundland and transported across the ocean for sale. That increased production supported a qualitative increase in the volume of fish consumed in Europe — and it began the long-term depletion of ocean life that in our time has pushed cod and many other ocean species to the brink of extinction.

+ + + + + +

Many questions remain. How did the huge increase in fish from Newfoundland affect coastal and regional fisheries in Europe? Who were the workers who joined long distance fishing fleets? Did the same men return year after year, or was it a temporary expedient for some? How did the merchants who financed the expeditions invest their profits? We know that merchants who invested in American colonies tended to support Parliament when Civil War broke out in England the 1640s, but what about the West Country capitalists who organized transatlantic fishing? How were North Atlantic ecosystems affected by the large-scale removal of top predators?

More research is needed, but the existence of a large fishing industry during what Marx called the age of manufacture is beyond doubt. Despite that, historians debating the origin of capitalism have rarely mentioned the industry that employed more working people than any field other than farming. I hope this article contributes to a more rounded picture, and shows that no account of capitalism’s origins is complete if it omits the development and growth of intensive fishing in the centuries when capitalism was born.

This four-part article on intensive fishing and the birth of capitalism is part of my continuing project on metabolic rifts. Your constructive comments, suggestions, and corrections will help me get it right. -IA

Notes

[1] Eric Hobsbawm, “From Feudalism to Capitalism,” in The Transition from Feudalism to Capitalism, ed. Rodney Hilton (Verso, 1978), 162.

[2] Since the 1980s, the two leading schools of thought have been Political Marxism, associated with Robert Brenner, and World-systems Analysis, associated with Immanuel Wallerstein. For recent work from those currents, see: Xavier Lafrance and Charles Post, eds., Case Studies in the Origins of Capitalism (Palgrave MacMillan, 2019); and Christopher K. Chase-Dunn and Salvatore J. Babones, eds., Routledge Handbook of World-systems Analysis (Routledge, 2012).

Important books that critique and move beyond both approaches include: Henry Heller, The Birth of Capitalism (Pluto, 2011); Neil Davidson, How Revolutionary Were the Bourgeois Revolutions? (Haymarket, 2012); and Alexander Anievas and Kerem Nişancıoğlu, How the West Came to Rule (Pluto 2015).

[3] Laurier Turgeon, “Codfish, Consumption, and Colonization: The Creation of the French Atlantic World During the Sixteenth Century,” in Bridging the Early Modern Atlantic World, ed. Caroline A. Williams (Routledge, Taylor & Francis, 2016) 37-38.

[4] Peter E. Pope, Fish into Wine: The Newfoundland Plantation in the Seventeenth Century (University of North Carolina Press, 2004) 13, 22.

[5] Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations (Modern Library, 2000) 3-5.

[6] Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, trans. Ben Fowkes, vol. 1, (Penguin Books, 1976), 456-7.

[7] Marx, Capital, vol. 1, 480.

[8] Raj Patel and Jason W. Moore, A History of the World in Seven Cheap Things (University of California Press, 2017) 14-16.

[9] Laurier Turgeon, The Era of the Far-Distant Fisheries: Permanence and Transformation, (Centre for Newfoundland Studies, 2005) 40, 39.

[10] Pope, Fish Into Wine, 25-28. The relevant section of Yonge’s journal is online at https://www.heritage.nf.ca/articles/exploration/james-yonge-journal-extract-1663.php

[11] Pope, Fish Into Wine, 171-2.

[12] Marx, Capital, vol. 1, 473.

[[13] Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, trans. David Fernbach, vol. 3, (Penguin Books, 1981), 452-5)

[14] Maurice Dobb, Studies in the Development of Capitalism, (International Publishers, 1963 [1947]), 126.

[15] Selma Huxley Barkham, “The Basque Whaling Establishments in Labrador 1536-1632 — A Summary,” Arctic 37, no. 4 (December 1984) 517.

[16] Gillian T. Cell, English Enterprise in Newfoundland, 1577-1660, Kindle ed. (University of Toronto Press, 1969), chapter 1.

[17] Samuel Eliot Morison, The European Discovery of America: The Northern Voyages (Oxford University Press, 1971), 268.

[18] David McNally, Against the Market: Political Economy, Market Socialism and the Marxist Critique (Verso, 1993), 10.

[19] Marx, Capital, vol. 1, 876.

[20] James D. Tracy, “Herring Wars: The Habsburg Netherlands and the Struggle for Control of the North Sea, ca. 1520-1560,” Sixteenth Century Journal 24, no. 2 (Summer 1993) 254

[21] Sir David Kirke in 1639, quoted in Pope, Fish Into Wine, 161.

[22] Daniel Vickers, Farmers & Fishermen: Two Centuries of Work in Essex County, Massachusetts, 1630-1850 (University of North Carolina Press, 1994), 89-90.

[23] Brereton, Rosier, and Davies quoted in Callum Roberts, The Unnatural History of the Sea (Island Press, 2007) 37-38.

[24] Callum Roberts, The Unnatural History of the Sea (Island Press, 2007), 38.

[25] G. A. Rose, “Reconciling Overfishing and Climate Change with Stock Dynamics of Atlantic Cod (Gadus morhua) over 500 Years,” Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences (September 2004), 1553-1557.

[26] Peter Pope, “Early estimates: Assessment of catches in the Newfoundland cod fishery, 1660-1690,” quoted in John F. Richards, The Unending Frontier: An Environmental History of the Early Modern World (University of California Press, 2005), 567.

[27] John F. Richards, The Unending Frontier: An Environmental History of the Early Modern World (University of California Press, 2005), 569.

[28] Poul Holm et al., “The North Atlantic Fish Revolution (ca. AD 1500),” Quaternary Research, 2019, 1-15.

[29] Marx, Capital, vol. 1, 486.

![The History Of Thacker Pass [Dispatches from Thacker Pass]](https://dgrnewsservice.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2021/02/Thacker-Pass-Max-Wilbert.jpeg)