by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 15, 2017 | White Supremacy, Worker Exploitation

by Alex Jensen / Local Futures

While misogyny, racism, and ethnic taunts were conspicuous signposts on Donald Trump’s path to the White House, much of that road was paved with “populist”, “anti-establishment” and “anti-globalization” rhetoric. Trump’s inaugural address featured numerous populist lines (e.g. “What truly matters is not which party controls our government, but whether our government is controlled by the people”), attacks on the status quo (“The establishment protected itself, not the citizens of our country”), and barbs aimed at globalization (“One by one, the factories shuttered and left our shores, with not even a thought about the millions upon millions of American workers left behind.”)

Are these themes accurate predictors of how Mr. Trump and his administration will govern for the next four years?

Hardly. Long before the election, it was widely pointed out that the populist platitudes issuing from the silver-spooned mouth of a billionaire plutocrat represented little more than elite hucksterism. [1] Of course, post-election, the band of fellow billionaire corporate rascals and knaves Trump assembled for his cabinet and close advisors should have put an end to this fatuous ‘anti-establishment’, ‘populist’ charade once and for all. As one observer noted, “Trump’s cabinet has begun to resemble a kind of cross between the Fortune 500 rich list, a financier’s reunion party and a military junta.” [2]

What about Trump as an ‘anti-globalization’ crusader? Apart from the inconvenient fact that his own loot was built upon global outsourcing and the exploitation of cheap labor abroad for which ‘globalization’ is shorthand, the fact is that a “former Chamber [of Commerce] lobbyist who has publicly defended NAFTA and outsourcing more generally was appointed to Trump’s transition team dealing with trade policy.” [3] Did anyone really buy the notion that the swaddled child of corporate globalization had morphed into a working-class hero battling the ravages of that same globalization?

Some of Trump’s voters were undoubtedly among those who have been economically marginalized by globalization and wealth inequality – the common folk on whose behalf populism historically emerged. No doubt some allowed Trump’s populist, anti-globalization legerdemain to blind them to his scapegoating of fellow displaced working-class victims of globalization – aka immigrants from non-European countries. That these constituted the majority of his voters, however, is questionable. As Jeet Heer argued convincingly back in August,

“Rather than a populist, Trump is the voice of aggrieved privilege—of those who already are doing well but feel threatened by social change from below, whether in the form of Hispanic immigrants or uppity women. … Far from being a defender of the little people against the elites, Trump plays to the anxiety of those who fear that their status is being challenged by people they regard as their social inferiors.” [4]

In other words, Donald Trump is no populist, but an “authoritarian bigot”[5], and his election represents the victory of the rich – and a victory for corporate globalization. He is “not an outlier, but instead the essence of unrestrained capitalism.” [6] (To be clear, this should in no way be read as an implicit endorsement of the neoliberal Democratic Party, whose economic and trade policies are largely pro-corporate as well.)

To see Trump as an anti-globalization crusader is to misunderstand one of the main structural features of globalization itself: the concentration of wealth by fewer and fewer corporations and the consequent widening of the gulf between rich and poor. According to a recent report, [7] here are some relevant trends from 1980 to 2013 – roughly the period of hyper globalization:

- Corporate net profits increased about 70 percent;

- Three-quarters of this increase went to the largest corporations (those with over $1 billion in annual sales);

- Just 10 percent of publicly listed companies account for 80 percent of corporate profits; the top quintile earns 90 percent;

- Two-thirds of 2013 global profits were captured by corporations from rich, industrialized countries;

- During this period in these same “rich countries”, labor’s share of national income has plummeted. Needless to say, labor in poorer countries has not fared better – indeed, exploitation of labor’s “cheapness” in the poorer countries is the sine qua non of this spasm of corporate profits.

As Martin Hart-Landsberg explains in his summary of the report, “the rise in corporate profits has been largely underpinned by a globalization process that has shifted industrial production to lower wage third world countries, especially China; undermined wages and working conditions by pitting workers from different communities and countries against each other; and pressured core country governments to dramatically lower corporate taxes, reduce business regulations, privatize public assets and services, and slash public spending on social programs.” [8]

This strategy has not “helped lift hundreds of millions to escape poverty over the past few decades”, as is repeatedly, unquestioningly claimed in the mainstream media. [9] As scholar Jason Hickel has shown, such a claim rests on propagandistic World Bank-sponsored poverty statistics; if poverty were to be measured more accurately, “We would see that about 4.2 billion people live in poverty today. That’s more than four times what the World Bank would have us believe, and more than 60% of humanity. And the number has risen sharply since 1980, with nearly 1 billion people added to the ranks of the poor over the past 35 years.” [10]

Additionally, inequality has reached nauseating heights: the latest analysis by Oxfam shows that “Eight men own the same wealth as the 3.6 billion people who make up the poorest half of humanity.” [11] Globalization – an abbreviated way of describing the worldwide evisceration of regulations hampering corporate profits and the institutionalization of those that enhance them – is an engine of extreme inequality and corporate power, within and between countries, full stop. It is not cosmopolitanism, humanism, global solidarity, multicultural understanding and tolerance, or any of the other noble liberal virtues claimed for it by its votaries. In fact, while a ‘borderless’ world was seen as the pinnacle of the globalization project, physical barriers at the world’s borders have actually increased by nearly 50 percent since 2000 [12] – with the US, India and Israel alone building an astounding 5,700 km of barriers. [13]

Widespread hostility towards globalization by the working class in ‘rich countries’ is understandable and justified. The problem is that this animosity is being misdirected against fellow working-class victims of corporate profiteering (“immigrants”, “the Chinese”), and not against the banks and corporations that are the source of working-class misery. This is the strange creature called ‘right-wing anti-globalization’, or, ‘right-wing populism’ – concepts that seem rather contradictory insofar as right-wing politics is about defending and strengthening status quo arrangements of power, privilege and hierarchy. Anti-globalization, on the other hand, is about challenging the gross inequality and injustice of the status quo; and populism – historically at least – is supposed to be about advancing the interests of common people and creating a more egalitarian society. [14]

Nonetheless, it is common in the mainstream media for ‘anti-globalization’ to appear on the ugly right-wing and reactionary side of a simplified binary ledger of political ideologies. It is listed, almost automatically, alongside such distasteful qualities as “inward-looking” and “anti-immigrant”, while the opposite side is ascribed noble qualities like “tolerance” and “solidarity”. This is merely a recycling of the popular (and very much corporate-sponsored) notion of globalization-as-humanizing-global-village. This Thomas Friedman-esque framing works to deflate the would-be critic of corporate globalization by threatening to tar her by association with reactionaries and xenophobes.

To accede to this binary framing would be a grave error, since it further empowers the existing system of corporate exploitation and wealth concentration. However, because there is undeniably an element of the anti-immigrant, xenophobic right that is also – at least rhetorically – anti-globalization, it is absolutely essential for the left to articulate in the clearest terms possible an anti-globalization stance rooted in international solidarity, intercultural openness and exchange, environmental justice, pluralism, fraternity, solidarity, and love, and to continually expose the fact that globalization is intolerant of differences in its relentless dissemination of a global consumer monoculture. In other words, the right should not be allowed to hijack the anti-globalization discourse, and contaminate and confuse it with racist, anti-immigrant sentiment, nor let localization – the best alternative to globalization – become equated with nativism, nationalism, xenophobia etc. It is unfortunate that we have to do this, since peoples’ movements against globalization and for decentralization/re-localization have already clearly drawn this distinction, indeed emerged in large measure in opposition to global injustice. But do it we must, since the corporate media is happily using the rise of the right-wing to discredit the spirited, leftist opposition to globalization that has stalled such corporate power grabs as TPP, CETA, and TTIP.

Should the left make common cause with those on the right when it comes to opposing globalization, irrespective of our profound opposition to the rest of the rightist agenda? Can we hold our noses and engage with this strange bedfellow to slay our ‘common’ foe, globalization? I do not think so. Not only is right-wing anti-globalization based on a deeply flawed and internally incoherent analysis, more importantly the political expediency of the implicit message – “as long as you join us in opposing corporate free trade treaties, your xenophobia, racism et al. can be temporarily ignored and tacitly tolerated” – is noxious and inexcusable.

Fortunately, a number of writers and activists have already been busy on the critical project of framing an inclusive anti-globalization stance. Chris Smaje, agrarian and writer of the Small Farm Future blog in the UK has spelled out a vision of “left agrarian populism” that is genuinely anti-establishment and pro-people (all people), is based on and strengthens local economies, and is fiercely internationalist. [15] Localist and internationalist? Yes. Localization of economic activity is, perhaps counter-intuitively, supportive of greater global collaboration, understanding, compassion and intellectual-cultural exchange, while corporate-controlled economic globalization has hardened, and even produced, cultural/national friction and competition.

Political theorist Chantal Mouffe has similarly acknowledged the right-wing hijacking of legitimate political discontentment against corporate elitism across Europe, the answer to which, she says, must involve “the construction of another people, promoting a progressive populist movement that is receptive to those democratic aspirations and orients them toward a defense of equality and social justice. Conceived in a progressive way, populism, far from being a perversion of democracy, constitutes the most adequate political force to recover it and expand it in today’s Europe.” [16]

Degrowth scholar-activists Francois Schneider and Filka Sekulova have, in line with Smaje’s left-green localism-populism, articulated the important concept of ‘open-localism’ or ‘cosmopolitan localism’. “Open-localism”, they write, “does not create borders, and cherishes diversity locally. It implies reducing the distance between consumer and producers … being sensitive to what we can see and feel, while being cosmopolitan”. [17] These visions, and many other related ones, provide an important foundation for social justice and environmental activists to build upon in boldly reclaiming the anti-globalization narrative and resistance in these difficult times.

Alex Jensen is Project Coordinator at Local Futures/International Society for Ecology and Culture. He has worked in the US and India, where he co-ordinated Local Futures’ Ladakh Project from 2004-2015. He has also been an associate of the Sambhaavnaa Institute of Public Policy and Politics in Himachal Pradesh, India. He has worked with cultural affirmation and agro-biodiversity projects in campesino communities in a number of countries, and is active in environmental health/anti-toxics work.

Endnotes

[1] See for example Naureckas, Jim, “Hey NYT – the ‘Relentless Populist’ Relented Long Ago”, Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting, January 22, 2017; Lynch, Conor, “Don’t be fooled: Trump’s populist economic rhetoric is a fraud”, Salon, July 9, 2016; Paarlberg, Michael, “Donald Trump is a pretend populist – just look at his economic policy”, The Guardian, August 10, 2016.

[2] Warner, J. (2016) “Donald Trump’s cabinet of oil men and generals is just what’s needed to get US out of its rut “, The Telegraph, December 16, 2016.

[3] Hart-Landsberg, M. (2016) ‘Confronting Capitalist Globalization’, Reports from the Economic Front.

[4] Heer, J. (2016) ‘Donald Trump Is Not a Populist. He’s the Voice of Aggrieved Privilege’, New Republic, 24 August.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Cuadros, A. (2016) ‘The Other Buffett Rule; or why better billionaires will never save us’, The Baffler, No. 33.

[7] McKinsey Global Institute (2015). “Playing to Win: the new global competition for corporate profits”, September 2015.

[8] Hart-Landsberg, M. (2016) ‘The Trump Victory’, Reports from the Economic Front, 18 November, 2016.

[9] See for example Pylas, P. and Keaten, J. (2017) ‘Will Trump end globalization? The doubt haunts Davos’ elite‘, Associated Press, January 20, 2017.

[10] Hickel, J. (2015) “Could you live on $1.90 a day? That’s the international poverty line”, The Guardian, November 1, 2015.

[11] Oxfam (2017) ‘Just 8 men own same wealth as half of humanity’, Oxfam International Press Release, 16 January, 2017.

[12] Harper’s Index, ‘Percentage by which the number of international borders with barriers has increased since 2014: 48’, Harper’s Magazine, January 2017.

[13] Jones, R. (2012) Border Walls: Security and the War on Terror in the United States, India and Israel, London: Zed Books.

[14] cf. Heer 2016, op.cit.

[15] Smaje, C. (2016) ‘Why I’m still a populist despite Donald Trump: elements of a left agrarian populism’, Small Farm Future, 17 November.

[16] Mouffe, C. (2016) ‘The populist moment’, Open Democracy, 21 November.

[17] Schneider, F. and Sekulova, F. (2014) ‘Open-localism’, paper presented at the 2014 International Conference on Degrowth, Leipzig, Germany.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 30, 2017 | Strategy & Analysis

by Derrick Jensen

When I find myself in times of trouble, I’m less interested in Mother Mary’s wisdom than I am in Joe Hill’s: Don’t mourn; organize.

There’s a sense in which Trump’s election is a surprise, similar to how we somehow seem to be continually surprised when easily predictable negative consequences of this way of life come to pass. So we’re surprised when bathing the world in insecticides somehow causes crashes in insect populations, when covering the world in endocrine disrupters somehow leads to the disruption of endocrine systems, when damming and dewatering rivers somehow kills the rivers, when murdering oceans somehow murders oceans, when colonialism somehow destroys the lives of the colonized, when capitalism somehow destroys communities and the natural word, when rape culture somehow leads to rape, and so on. And we’re surprised when a racist, woman-hating culture elects a racist man who hates women.

But there are also many senses in which the rise of Trump or someone very like him was entirely predictable.

An empire in decay leads to a desperate push to the fore of values manifested by Trump: woman-hatred, racism, the scapegoating of those who impede empire, and a willingness to do whatever it takes to maintain that empire, to “make America [Greece, Rome, Britain, China] great again.”

When those who have been able to exploit others with impunity find their way of life (and more to the point, the exploitation and entitlement upon which their way of life is based) crumbling, what do they do?

We’ve seen this before. Why did lynchings of African-Americans go up soon after the Civil War and the end of chattel slavery? Why did the KKK rise again in the 1910s and 1920s? What is the relationship between Germany’s economic collapse in the 1920s and the rise of Nazi fascism?

Nietzsche provides one answer: “One does not hate when one can despise.”

So long as one’s exploitation of others proceeds relatively smoothly, one can merely despise those one exploits (despise, from the root de-specere, meaning to look down upon). So long as I have unfettered access to the lives and labor of, say, African-Americans, everything is, from my perspective, A-Okay. But impinge in any way on my ability to exploit, and watch the lynchings begin. The same is true for my access to other so-called resources as well, whether these “resources” are “timber resources,” “fisheries resources,” cheap plastic crap from China, or sexual and reproductive access to women. So long as the rhetoric of superiority works to maintain the entitlement, hatred and direct physical force remain underground. But when that rhetoric begins to fail, force and hatred waits in the wings, ready to explode.

Oh, but we wouldn’t do that, would we? Well, what if someone told you that no matter how much you paid to purchase title to some piece of land, the land itself does not belong to you. No longer may you do whatever you wish with it. You may not cut the trees on it. You may not build on it. You may not run a bulldozer over it to put in a driveway. Would you get pissed? How if these outsiders took away your computer because the process of manufacturing the hard drive killed women in Thailand. They took your clothes because they were made in sweatshops, your meat because it was factory-farmed, your cheap vegetables because the agricorporations that provided them drove family farmers out of business, and your coffee because its production destroyed rain forests, decimated migratory songbird populations, and drove African, Asian, and South and Central American subsistence farmers off their land. They took your car because of global warming, and your wedding ring because mining exploits workers and destroys landscapes and communities. Imagine if you began losing all of these parts of your life that you have seen as fundamental. I’d imagine you’d be pretty pissed. Maybe you’d start to hate the assholes doing this to you, and maybe if enough other people who were pissed off had already formed an organization to fight these people who were trying to destroy your life—I could easily see you asking, “What do these people have against me anyway?”—maybe you’d even put on white robes and funny hats, and maybe you’d even get a little rough with a few of them, if that was what it took to stop them from destroying your way of life. Or maybe you would vote for anyone who promised to make your life great again, even if you didn’t really believe the promises.

The American Empire is failing. Real wages have been declining for decades, for the entire lifetime of most people living today in the U.S. Indeed if real wages peaked in 1973, the last of those who entered the workforce in a time of universally increasing expectations are retiring. Sure, some sectors of the economy have done well, but what of those left behind? What of those whose livelihoods have been destroyed by a globalized economy, by the shifting of jobs to China, Vietnam, Bangladesh?

What happens to people in a time of declining expectations? What is the relationship between these declining expectations and the rise of fascism?

Two decades ago now a long-time activist said to me that Walmart and its cheap plastic crap was the only thing standing between the United States and a fascist revolution.

But cheap plastic crap can only put off fascism for so long.

There’s a difference between the ends of previous empires and the end of the current empire. That difference is global ecological collapse. Empires are always based not only on the exploitation of the poor but on the existence of new frontiers. Any expanding economy–and all empires are by definition expanding economies—need to continue expanding or collapse. America grew because there was always another ridge to cross with another forest to cut on the far side, always another river to dam, another school of fish to find and net. And the forests are gone. The rivers are gone. The fish are gone. The pyramid scheme upon which both civilization and more recently capitalism are based has reached its endgame.

And rather than honestly and effectively addressing the predicament into which not only we ourselves but the world has been pushed, it’s far easier to lie to ourselves and to each other. For some—and Democrats generally choose this lie—the lie can be that despite all evidence, capitalism need not be destructive of the poor and of the natural world, that the “invisible hand of Adam Smith” can, as Bill Clinton put it, “have a green thumb.” We just have to do capitalism nicely. And another lie—this one more favored by Republicans and manifested by Trump—is that the sources of our misery do not inhere in capitalism but rather come from Mexicans “stealing our jobs” and not remembering their proper place, from women no longer remembering their proper place, from African Americans no longer remembering their proper place. Their proper place of course being in service to us. And of course those damn environmentalists—“Enviro-Meddlers,” as some call them—are to blame for denying us access to that last one percent of old growth forest, that last one percent of fish. This lie blames anyone and anything other than the end of empire.

All of which brings us to the Democrats’ responsibility for Trump’s election. There has not been a time in my adult life—I’m 55—when Democrats have maintained more than the barest pretense of representing people over corporations. Through this time Democrats have functionally played good cop to the Republicans’ bad cop, as Democrats have betrayed constituency after constituency to serve the corporations that we all know really run the show. For generations now Democrats have known and taken for granted that those of us who care more for the earth or for justice or sanity than we do increased corporate control will not jump ship and support the often open fascists on “the other side of the aisle,” so these Democrats have calmly sidled further and further to the right.

Bad cop George Bush the First threatened to gut the Endangered Species Act. Once he had us good and scared, in came good cop Bill Clinton, who did far more harm to the natural world than Bush ever did by talking a good game while gutting the agencies tasked with overseeing the Act. Clinton, like any good cop in this farcical play, claimed to “feel our pain” as he rammed NAFTA down our throats.

What were we going to do? Vote for Bob Dole? Not bloody likely.

Obama made a big deal of delaying the Keystone XL as he pushed to build other pipeline after other pipeline, and as he opened up ever more areas to drilling. He pretended to “wage a war on coal” while expanding coal extraction for export.

What were we going to do? Vote for Mitt Romney?

For too long the primary and often sole argument Democrats have used in election after election is, “Vote for me. At least I’m not a Republican.” And as terrifying as I find Trump, Giuliani, Gingrich, Ryan, et al, this Democratic argument is not sustainable. Fool me five, six, seven, eight times, and maybe at long last I won’t get fooled again.

What we must finally realize is that the good cop act is, too, simply an act, and that neither the good cops nor the bad cops have ever had our interests at heart.

The primary function of Democrats and Republicans alike is to take care of business. The primary function is not to take care of communities. The primary function is not to take care of the planet. The primary function is to serve the interests of the owning class, by which I mean the owners of capital, the owners of society, the owners of the politicians.

We have seen over the last couple of generations a consistent ratcheting of American politics to the right, until by now our political choices have been reduced to on the one hand a moderately conservative Republican calling herself a Democrat, and on the other a strutting fascist calling himself a Republican. If we define “left” as being at minimum against capitalism, there is no functional left in this country.

For all of these reasons the election of Trump is no surprise.

But there’s another reason, too. The US is profoundly and functionally racist and woman-hating, nature hating, poor hating, and based on exploiting humans and nonhumans the world over. So why should it surprise us when someone who manifests these values is elected? He is not the first. Andrew Jackson anyone?

If that activist was right so many years ago, that cheap plastic crap from Walmart was the only thing standing between us and fascist revolution (and of course this cheap plastic crap merely pushed this social and natural destructiveness elsewhere) then he had to know also that cheap plastic crap is not a long term bulwark against fascism. It can only keep those chickens at bay for so long before they come home to roost.

The good cop/bad cop game is a classic tool used by abusers. You can do what I say, or I can beat you. You can sell me your cotton for 50 cents on the dollar, or I can hang you on a tree next to the last black man who refused my offer. Germans offered Jews the choices of different colored ID cards, and many Jews spent a lot of energy trying to figure out which color was better. But the whole point was to keep them busy while convincing them they held some responsibility for their own victimization.

I’ve long been guided by the words of Meir Berliner, who died fighting the SS at Treblinka, “When the oppressors give me two choices, I always take the third.”

By choosing the third I don’t mean simply choosing a third party candidate and perceiving yourself as pure and above the fray, as capitalism still continues to kill the planet.

I mean recognizing the truths about this whole exploitative, unsustainable, racist, woman-hating system. Recognizing that the function of politicians in a capitalist system is to act very much like human beings as they enact what is good for capital, as they facilitate, rationalize, put in place, and enforce a socio-pathological system. Recognizing that capital—including the functionaries of capitalism called “politicians”—will not act in opposition to capital because it is the right thing to do. These functionaries will not act in opposition to capital because we ask nicely. They will not act in opposition to capital because capitalism impoverishes the poor worldwide. They will not act in opposition to capital because capitalism is killing the planet. They will not act in opposition to capital. Period.

The power they wield, and the way they wield it, is not a mistake. It is what capitalism does.

Which brings us to Joe Hill. Don’t simply complain about Trump. Don’t simply throw up your hands in despair. Don’t fall into the magical thinking that the good cops would, if just unhindered by those bad cops, do the right thing or act in your best interests. Don’t fall into the magical thinking that capitalists will act other than they do. And certainly don’t take for granted that somehow magically we and the world will get out of this predicament, that somehow magically an anti-capitalist movement will spontaneously generate, or an anti-racist movement, a pro-woman movement, a movement to stop this culture from killing the planet. These movements emerge only through organized struggle. And someone has to do the organizing. Someone has to do the struggling. And it has to be you, and it has to be me.

A doctor friend of mine always says that the first step toward cure is proper diagnosis. Diagnose the problems, and then you become the cure.

You make it right.

So what I want you to do in response to the election of Donald Trump is to get off your butt and start working for the sort of world you want. Don’t mourn the election of Trump, organize to resist his reign, and organize to destroy the stranglehold that the Capitalist Party has over political processes, the stranglehold that capitalists and racists and woman-haters have over the planet and over all of our lives.

For more of Derrick Jensen’s analysis of racism, hatred, and the violence of civilization, see his book The Culture of Make Believe

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 8, 2017 | Lobbying, Strategy & Analysis

Featured image: Cofan Indigenous leader Emergildo Criollo looks over an oil contaminated river hear his home in northern Ecuador. Photo by Caroline Bennett / Rainforest Action Network (flickr). Some rights reserved.

by Kiana Herold / Intercontinental Cry

Indigenous battles to defend nature have taken to the streets, leading to powerful mobilizations like the gathering at Standing Rock. They have also taken to the courts, through the development of innovative legal ways of protecting nature. In Ecuador, Bolivia and New Zealand, indigenous activism has helped spur the creation of a novel legal phenomenon—the idea that nature itself can have rights.

The 2008 constitution of Ecuador was the first national constitution to establish rights of nature. In this legal paradigm shift, nature changed from being held as property to a rights-bearing entity.

Rights are typically given to actors who can claim them—humans—but they have expanded especially in recent years to non-human entities such as corporations, animals and the natural environment.

The notion that nature has rights is a huge conceptual advance in protecting the Earth. Prior to this framework, an environmental lawsuit could only be filed if a personal human injury was proven in connection to the environment. This can be quite difficult. Under Ecuadorian law, people can now sue on the ecosystem’s behalf, without it being connected to a direct human injury.

The Kichwa notion of “Sumak Kawsay” or “buen vivir” in Spanish translates roughly to good living in English. It expresses the idea of harmonious, balanced living among people and nature. The idea centers on living “well” rather than “better” and thus rejects the capitalist logic of increasing accumulation and material improvement. In that sense, this model provides an alternative to the model of development, by instead prioritizing living sustainably with Pachamama, the Andean goddess of mother earth. Nature is conceived as part of the social fabric of life, rather than a resource to be exploited or as a tool of production.

The Preamble of the Ecuadorian Constitution reads:

“We women and men, the sovereign people of Ecuador recognizing our age-old roots, wrought by women and men from various peoples, Celebrating nature, the Pacha Mama (Mother Earth), of which we are a part and which is vital to our existence…. Hereby decide to build a new form of public coexistence, in diversity and in harmony with nature, to achieve the good way of living, the sumac kawsay.”

The traditional Quechua relation to the natural world is firmly rooted in the Constitution. The interchangeable use of nature and Pacha Mama testifies to the indigenous influence on the Constitution.

The concept and the praxis

In the 1970s, Christopher Stone, an American environmental legal scholar, articulated the legal notion of the rights of nature in his widely read essay Should Trees Have Standing? Stone envisioned a new way of conceptualizing nature through law that broke with the existing paradigm of the commodification of nature, often established through law.

Property rights are a primary example of commodifying the natural world. When treated as property, nature incurs damages that often go unrecognized. Stone writes that an argument for “personifying” nature can best be considered from a welfare economics perspective. Under capitalist economic logic, many externalities that negatively impact the environment are not registered when calculating the cost of an action. Transforming nature legally from mere property to a rights-holding entity would force byproduct environmental effects of production to factor into cost calculations. Under this framework, nature would be better protected.

Incorporating rights of nature into a national constitution is a powerful paradigm shift, but may seem hypocritical and idealistic given states’ continuing dependence on extractive industries. In Ecuador, 14.8 percent of the GDP comes from profits from natural resources as of 2014.

Moreover, under Ecuadorian law, the rights of nature are subject to principles of so-called national development. Article 408 of the constitution stipulates that all natural resources are the property of the state, and that the state can decide to exploit them if deemed to be of national importance, as long as it “consults” the affected communities. However, there is no state obligation to abide to the result of the consultation to these communities– a gaping hole in full protection of these environments and the people living within them.

Nonetheless, Ecuador’s Constitution was a significant step in changing the legal paradigm of rights to one that is inclusive of nature.

Bolivia follows

Bolivia followed in Ecuador’s footsteps. Evo Morales, the first indigenous head of state in Latin America, was elected in 2005 and called for a constitutional reform that ultimately established rights to nature in 2009.

Again, indigenous philosophies were instrumental in the formulation of Bolivia’s new Constitution. The constitution’s preamble states that Bolivia is founded anew “with the strength of our Pachamama,” placing the indigenous understanding of nature as central to the very creation of the revised political state. Like in Ecuador, the Bolivian Constitution allows anyone to legally defend environmental rights.

Bolivia’s government soon instituted the Law of Mother Earth in 2010, later re-coining it as the Framework Law of Mother Earth and Integral Development to Live Well. The law lays out a number of rights for nature, such as the right to life and to exist, to pure water, clean air, to be free from toxic and radioactive pollution, a ban on genetic modification, and freedom from interference by mega-infrastructure and development projects that disturb the balance of ecosystems and local communities.

Part of the rationale behind the law is the hope of helping the environment through reducing causes of climate change, which is directly in Bolivia’s interests. Increasing temperatures in Bolivia pose problems to the nation’s farming sector and water supply.

Again, however, this legal concept does not match economic realities. The rights of nature are directly at odds with extractive industries that are intimately tied to Bolivia’s model of economic development. Despite legal frameworks defending the rights of nature, Bolivia’s profits from natural resources comprise 12.6 percent of the GDP as of 2014.

But there are alternatives to the Andean experience. Across the Pacific, New Zealand has also granted a legal status of personhood to specific rivers and forest, thus enabling the environment itself to have rights.

The New Zealand Take on Rights of Nature

Unlike Ecuador and Bolivia, New Zealand’s rights of nature are not embedded in its constitutional law, but rather protect specific natural entities. Native communities in New Zealand were instrumental in creating new legal frameworks that give legal personhood, and thus rights, to land and rivers.

New Zealand has bestowed legal personhood on the 821-square mile Te Urewara Park, and the Whanganui River, the nation’s third-largest river. This was part of the government’s reparation efforts for the historical injustice at the foundation of New Zealand’s state: colonial conquest of land from native peoples.

The Tuhoe tribe’s ancestral homeland is currently the Te Urewara Park. With the imposition of colonial governance, most of their land was taken from them without consultation, resulting in great spiritual and socio-economic losses. The land was designated a national park in 1954.

The Tuhoe tribe never signed the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi with the British Crown, which stripped the tribe of their sovereign right over their land. They have since contested the British assertion of sovereignty that undergirds the formation of the modern New Zealand state.

Their centuries-long struggle finally yielded results. As part of New Zealand’s reparation process towards Indigenous Peoples, the national government negotiated with the Tuhoe tribe regarding their historic land. In 2012 the Tuhoe tribe accepted the Crown’s offer of financial reparations, a historical account and apology and co-governance of Te Urewera lands. The national government renounced ownership of the land, giving the land its own personhood.

Under this framework, the land is now a legal entity in itself, owned neither by the government nor the Tuhoe tribe. The land is no longer property. It is its own untamed natural presence in and of itself, with, as per native understanding, its own life force and identity.

The land is now co-governed by the Tuhoe people and the New Zealand government.

The 2014 Te Urewara Act declares the park “a place of spiritual value.” The Act acknowledges that it is the sacred home of the Tuhoe people, integral to their “culture, language, customs and identity,” while also being of intrinsic value to all New Zealanders.

In a similar process of granting legal personhood, the local Maori tribe, the Iwi, helped the Whanganui River earn legal personhood status in 2014 after winning a long-fought court case.

This was part of a centuries-long struggle that the Whanganui tribes undertook to protect the river. Since the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, the river has been subject to gravel extraction, water diversion for hydro-electric plans, and river bed works to better navigability, under protest from local tribes.

The Maori fought to protect the river through a series of court cases beginning in 1938, defending their claim to the management of the river as its rightful guardian. Throughout the court cases, negotiations were undergirded by the native saying “Ko au te awa, ko te awa ko au,” which translates to “I am the river and the river is me.” This reflects native philsophies of reciprocal and equal relations between people and nature.

New Zealand’s attorney general Chris Finlayson was quoted in the New York Times as acknowledging the Maori perspective as formative in the granting of rights to these natural entities, saying “In their worldview, ‘I am the river and the river is me,’” he said. “Their geographic region is part and parcel of who they are.”

Expanding Legal Horizons?

The legal concept of rights of nature signal the influence of Indigenous Peoples as political actors in state-making, fundamentally reimagining law and how the natural world is conceived. These ideas present a revolutionary rupture in the conventional anthropocentric understanding of sovereignty, and a realignment of how the natural world is valued. In fact, they could chart the path forward for a new understanding of mankind’s relation to the natural world, even if they operate within the legal structures that are not conducive to indigenous philosophies.

It is true that the rights of nature as they currently stand have deep limitations, particularly given the ongoing extraction of non-renewable natural resources in Ecuador and Bolivia. Problems of corruption, environmental inequality and economic dependence on extractive industries are major challenges to the full realization of the rights of nature.

Yet small acts can lead to lasting change. This shift in the way we relate to and legally protect nature, however small and plagued by obstacles, could be an incremental step toward a more sustainable relation to the planet that could allow us to preserve the earth for future generations.

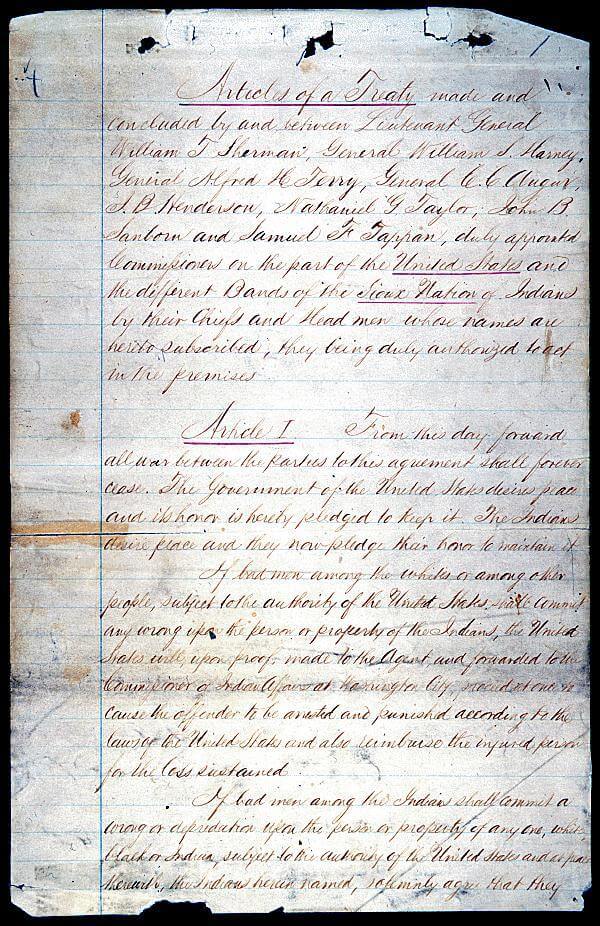

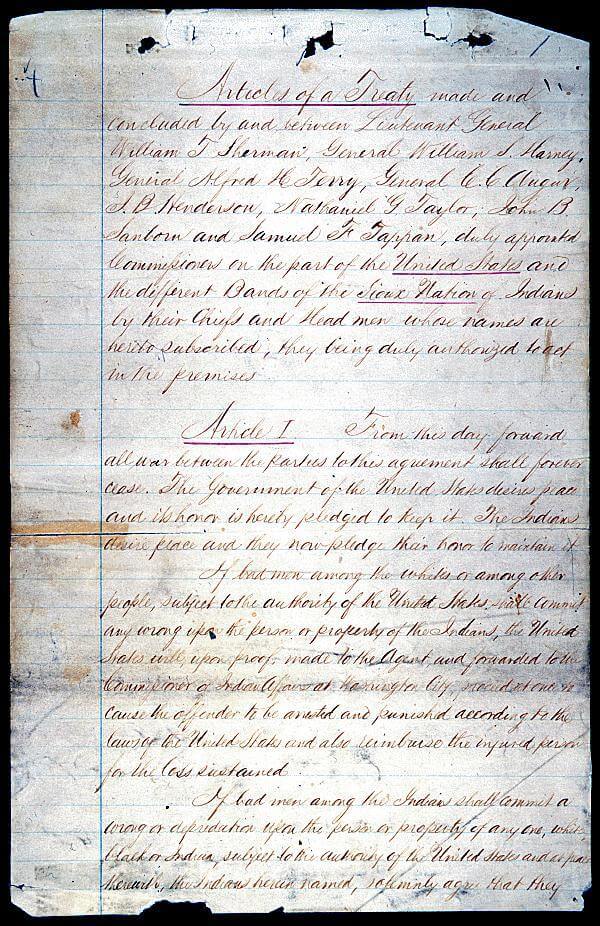

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 15, 2016 | Colonialism & Conquest

If treaties are the supreme law of the land, as the U.S. Constitution states, then how is it that treaties can be so easily broken by a government that claims to uphold a respect for the law? An even more unsettling question: how is it that the trail of broken treaties has been able to span generations under an outdated, imperial logic unknown to the majority of the U.S. citizens? The founding of the United States is predicated on this painful contradiction between principles of equality and rule of law on one side, and the colonial appropriation of land from native peoples who have inhabited them for millennia, on the other.

The current resistance against the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) is inscribed in this contradiction, making evident the non-rule of law when it comes to appropriating native lands.

The history of Standing Rock is marked by the history of colonization predicated on the Doctrine of Discovery. The progressive erosion of its Sioux territory goes hand in hand with the logic of terra nullius, which framed land in the Americas as “empty” in order to justify settler colonization.

The Sioux Nation has historically engaged in sovereign government-to-government relations with the US government. The first treaty in which the two parties engaged as diplomatic equals was the Treaty of Fort Laramie of 1851. It was the U.S. government who sought the treaty to allow for safe passage of the influx of settlers travelling west through Sioux territory during the Gold Rush from the east coast to California.

The process of negotiating the Treaty of Fort Laramie followed the colonial settler standard used in contemporary treaty negotiations. While the process was equal in theory to the traditional communal decision-making processes under which many Native Nations operated, the colonial method, which uses elected representatives, heavily favored the interests of the colonial government. Ultimately, the treaty established distinct territories for just under 10 Great Plain tribes. The treaty also permitted settlers to travel on the Platte River Road, achieving the U.S. government’s goal.

The 1851 treaty defined Sioux territory as the land where the DAPL is now being constructed. The territory fell within the western half of modern South Dakota, northwest Nebraska, a portion of northeast Wyoming, and a small part of southeast Montana and southwest North Dakota.

From the very beginning, various parties continuously broke the Treaty of Fort Laramie. Many tribes, unaware of the existence of the treaty, continued to carry out raids on tribes on legally different territories. Furthermore, settlers increasingly trespassed into the treaty territories, disrupting the buffalo hunting grounds of Native Nations. The settlers’ wrongful presence on native land led to various hostile skirmishes and bloody battles in which natives were massacred often without provocation.

But the violation of the Treaty of Fort Laramie didn’t stop there. Over the years, the U.S. government has continued to appropriate Sioux land in an ongoing process of colonization that disregards the treaty. (See map.)

In 1861, the discovery of gold in present-day Montana accentuated the flood of fortune-seekers overrunning Sioux lands in violation of the decade-old Laramie Treaty. Sioux protests to defend their rights and territory were ignored, so the Sioux took matters into their own hands to stop the trespassers. The U.S. responded by sending in a military presence.

Instead of adhering to the terms of the treaty, the U.S. government attempted to negotiate another treaty more preferential to its interests. Treaty making, instead of a diplomatic engagement between two equally powerful sovereign nations had turned into a destructive means of grabbing land and resources from native people; a form of “conquest by law” as per the book by Lindsay G. Robertson.

The result was a second treaty of Fort Laramie signed in 1868. This new treaty shrank the territorial boundaries of the Great Sioux Reservation in exchange for the U.S. federal government’s removal of all existing forts in the Powder River area, among other specifications. Yet it was a flawed treaty from the start. Most importantly, it stipulates that no changes can be made to the legally binding agreement unless ¾ of all adult Sioux males consent. Many members of the Sioux nation, particularly those within the boundaries of the territory signed the treaty. But many more bands residing north of the Bozeman Trail, such as the Hunkpapa and Sihasapa bands, did not. The treaty was not signed by three quarters of all adult Sioux males.

Yet, again, the U.S. government violated the treaty. The second Laramie treaty granted the tribes the right of regulating the entry of persons into their territory. Article II of the 1868 Treaty stipulates that nobody can enter the territory without tribal permission. But time and time again settlers have encroached on Sioux territory.

Some Americans may know that in 1874 the U.S. government sent George Custer with a group of scientists to search for natural resources, especially gold, in the isolated mountain range known today as the Black Hills. The gold they found led to an influx of miners, again in direct violation of the treaty.

Eventually, the U.S. government decided to pursue its strategy of land appropriation without bothering with the pretense of legality. The Sioux learned to be wary of treaties with the U.S. and refused to sign away their land.

In 1877, Congress unilaterally passed an act removing the sacred Black Hills from the Great Sioux Reservation, without the ¾ consent of the Sioux mandated by the Laramie Treaty of 1868. This illegal grab of sacred land brought no legal repercussions to the party that violated the treaty—the U.S. government.

In 1889, Congress again diminished the Great Sioux Reservation with the Dawes Act and Allotment Act, partitioning it into six sections, one of which was the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation. This opened up parts of the reservation to outside settlement, even though the native government still controls all reservation lands.

Sioux struggles for water are embedded in such displacements. In 1948, the U.S. government began construction of Oahe Dam, despite resistance from local tribes. Its creation flooded tribal land and forced a quarter of the reservation’s inhabitants to move.

In 1958, a federal court ruled that Lake Oahe was part of the Standing Rock territory according to the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty. In this ruling the court said, “Where there is a treaty with Indians which would otherwise restrict the Congress, Congress can abrogate the treaty in order to exercise its sovereign right.” The court openly articulated the self-arrogated right of the U.S. government to go back on treaty obligations with Native Americans to unilaterally exercise its sovereign power.

The U.S. did just that, taking the Lake Oahe land from the Standing Rock tribe through legislation passed by Congress in September 1958 [Public Law 85-915].

Legal abrogation, or repealing legislation, dispenses with any idea of fair treaty making between equals. It undermines native sovereignty, following a racist logic of colonial elimination. It dispenses with numerous prior legal precedents that granted Native Americans some rights, such as the Indian Appropriations Act of 1871, which declared that no treaty obligation with an Indian nation before March 3, 1871 can be “invalidated or impaired.” It puts into question the idea of the “federal Indian trust responsibility,” articulated in the Seminole Nation v. United States case of 1942, which entailed an obligation on the part of the U.S. government to protect tribal treaty rights, land, assets and resources, per the Department of the Interior Indian Affairs branch.

As a federally recognized tribe, the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe is legally entitled to these obligations. However, as history has shown, U.S. principles and laws do not seem to have the same meaning when it comes to Native Americans.

The United States claim that it can abrogate treaties with Native Americans has been upheld by US courts as legal. Law in our modern eyes carries the weight of legitimacy.

But because something is legal does not make it right. In the case of the Sioux, alongside every other Native American nation, laws and treaties have all too often been used not as a protective shield, or even as a neutral arbitrator, but as a weapon. That weapon is predicated on a racist, colonial history that invalidated native people’s rights to their land, to their sovereignty, to their cultural expression, to their very lives.

Whether it is the gold rush or the oil rush, the U.S government continues even now to invade native land and break treaties. The proposed DAPL would pass under Lake Oahe, the land that was openly, “legally” taken from the Sioux tribe in 1958 by Congress, despite the prior 1868 Treaty that had legally granted the Sioux rights to the land.

Today’s protests at Standing Rock today can only be fully understood in light of this colonial legacy, which from the beginning proclaimed that native lands were empty and that native people, were, in effect, nothing more than the rocks, the trees, the water that they now so valiantly strive to protect.

Let us fight against this narrative, and show through Standing Rock that native tribes are sovereign nations that possess the inherent right to life on their territories. Let us show that Native American lands are not empty, but that proud sovereign peoples live there, alongside the earth, water, rocks and trees, wind and sky, encompassing a vibrant fullness in their long defense of life.

There never was terra nullius. The only emptiness to be found exists in the hollow promises of the United States, in the historic lack of equitable substance in the U.S. legal system.

In that spirit, many U.S. citizens are now, finally, refusing to turn a blind eye to the trail of broken treaties. They stand with Standing Rock, and are petitioning President Obama to honor the treaties (petition here): “The Native nations have upheld their end of the bargain; it is time the U.S. government did the same.”

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 12, 2016 | Protests & Symbolic Acts

by Brett Spencer / Intercontinental Cry

On Monday, November 7th, the day after Nicaragua’s primary elections, supporters of the Miskito indigenous party, Yapti Tasba Masraka Nanih Aslatakanka, or Sons of Mother Earth (YATAMA), took to the streets of Puerto Cabezas to celebrate a regional victory for Indigenous Peoples. It had just been announced that Brooklyn Rivera, the leader of YATAMA, had won political office.

Supporters of YATAMA celebrate news of victory during a speech by Brooklyn Rivera. Photo: Brett Spencer

Local polls concluded that YATAMA had secured the victory despite numerous allegations of electoral fraud. Nine out of twelve people IC interviewed at four polling stations in Puerto Cabezas reported the fraud in favor of the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN), led by Nicaragua’s current president, Daniel Ortega.

“There is serious doubt about the transparency, the cleanliness and the purity of this process,” said Mr. Rivera. Other than YATAMA, “there is no real opposition” and “no international observation of the elections,” he concluded.

Despite these allegations, YATAMA supporters planned to march across the town at 2:00 pm. However, it was learned around that time that the victory would not be acknowledged until the vote was recounted in Managua, without the presence of YATAMA officials.

The announcement created a sense of unease as the streets filled with Miskito of all demographics in support of Brooklyn Rivera’s re-election as a deputy in the National Assembly.

Mr. Rivera was ousted from office in September of 2015, following a rise in violence over an endemic land conflict between the Miskito and Sandinista settlers known to the Miskito as colonos.

Puerto Cabezas reacts to news of a YATAMA victory. Photo: Brett Spencer

The indigenous population swelled the streets with gracious enthusiasm following an optimistic speech by Mr. Rivera. However, shortly after the start of the march, police began to line the main street in riot gear, preventing the march from continuing.

Miskito youth began throwing stones at the officers and the police began firing rubber bullets into the crowd, provoking more outrage. A group of YATAMA supporters overtook the governor’s office, removing office equipment including computers. The crowd began to compile makeshift weapons to fend off the police, who began using tear gas in an attempt to disperse the crowd.

Many of the women and children took safety in a bar overlooking the conflict, only to have tear gas thrown at them by the police officers.

Police fire rubber bullets at Miskito youth: Brett Spencer

“This was suppose to be a peaceful march, but the police started instigating,” said Walt, who works at the bar where we took safety. “But the people have to march to get results around here, otherwise the result would not be the same.”

YATAMA’s supporters eventually overtook the police around 6:00 pm, who retreated to the police station. After the sun had set, a group of Miskito youth, angry with the police for stopping the march, broke into several shops owned by Sandinista supporters.

Photo: Brett Spencer

The following morning, the local Sandinista radio station, Bilwi Stereo, blamed the conflict on the participation of foreigners, discrediting the power and agency of YATAMA’s wide support base. Puerto Cabezas became militarized overnight, with trucks of heavily armed soldiers patrolling the empty streets.

The streets remained calm but ill at ease, as relations between the Miskito and the Sandinista government continue to deteriorate. “We need something better for our people,” said Hector Williams, the Wihta Tara, or “Great Judge” of the Miskito separatist movement. “This is La Moskitia, it is not Nicaragua.”