by DGR News Service | Feb 17, 2020 | Defensive Violence, People of Color & Anti-racism

Long before the Civil War, black abolitionists shared the consensus that violence would be necessary to end slavery. Unlike their white peers, their arguments were about when and how to use political violence, not if.

By Randal Maurice Jelks / Boston Review

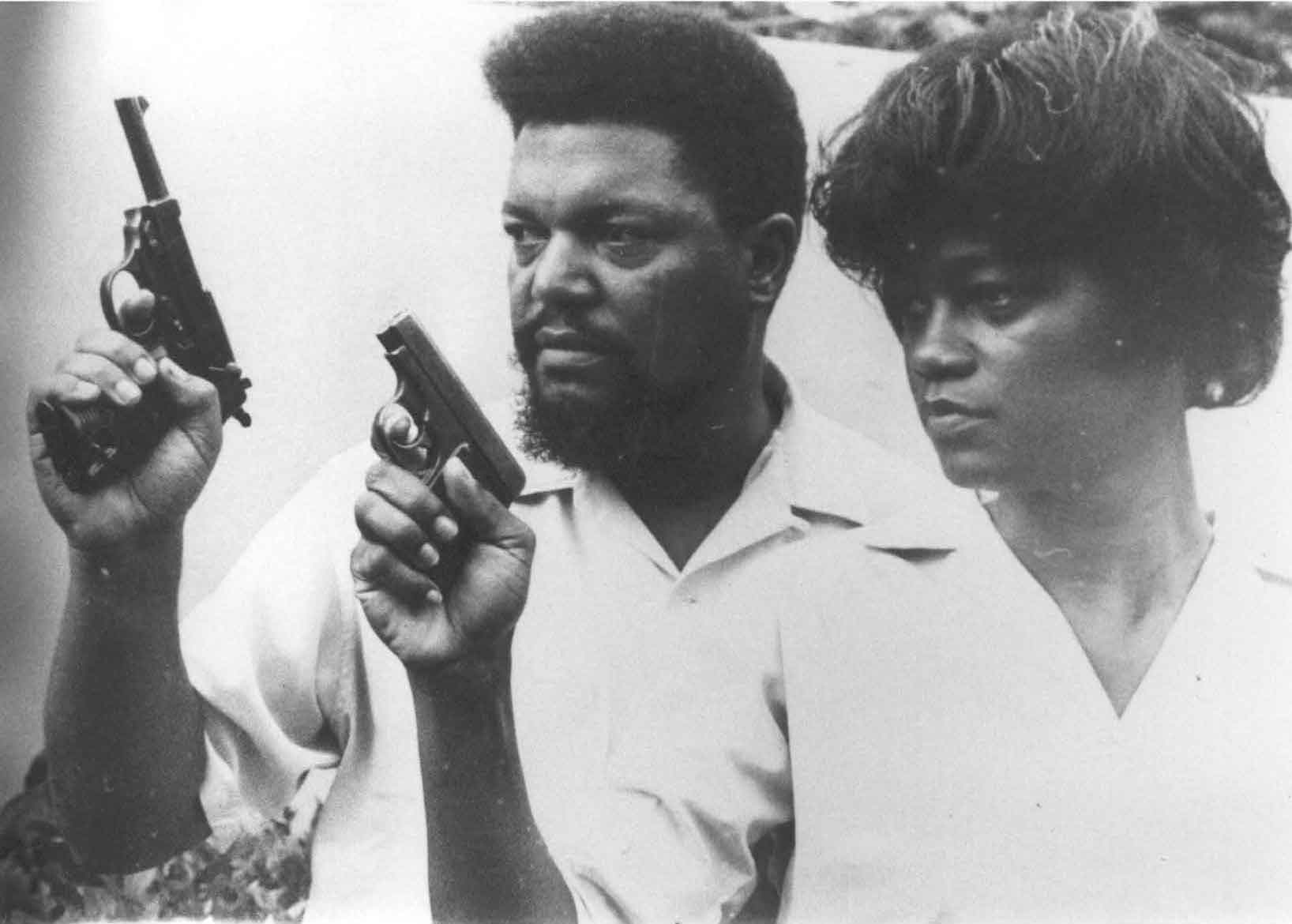

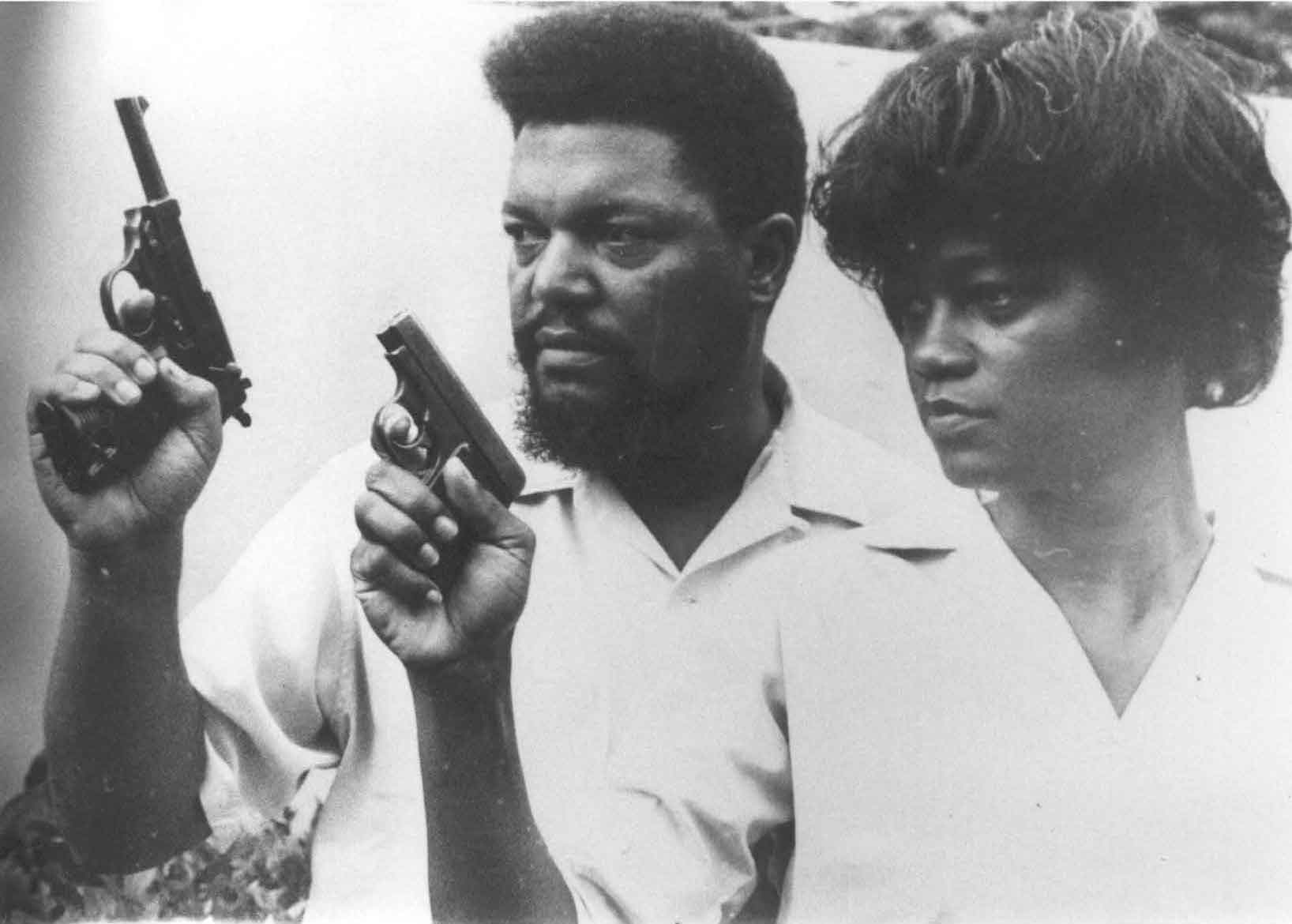

Reviewing “Force and Freedom: Black Abolitionists and the Politics of Violence,” by Kellie Carter Jackson. University of Pennsylvania Press. Featured image: Mabel and Robert Williams, advocates and practitioners of armed self-defense, a longtime tradition in the Black community, during the civil rights movement.

Although Thomas Jefferson opined to James Madison in 1787 “that a little rebellion now and then is a good thing, and as necessary in the political world as storms in the physical,” he did not have in mind a rebellion by his own forced laborers at Monticello. In fact, when the Second Amendment was drafted two years later, it was intentionally Janus-faced: it aimed to preserve the fruit of U.S. rebellion by arming citizens against an English invasion, even as it also empowered local militias to squash Native and slave rebellions.

The planter class understood that enslavement required complete dominance, including a monopoly on violence. South Carolina’s 1739 Stono Rebellion still loomed large in their memories: enslaved Kongolese warriors had raided guns and ammunition from a local store and killed more than two dozen whites before being defeated. And in 1791, the ink barely dry on the Constitution, Haiti erupted like Mount Vesuvius and challenged the dominion of slavocracy throughout the Americas. The brutally shrewd U.S. leaders realized that slave rebellions were always possible and that firearms had to be kept out of the hands of the enslaved.

Blacks understood this too: slavery was done through violence and would only be ended through violence. Enslaved men and women on the German Coast of Louisiana (today the East Bank of greater New Orleans), for example, inspired by The Declaration of the Universal Rights of Man, sought to emancipate themselves in 1811 by marching toward New Orleans with agricultural tools repurposed as military weapons. Though unsuccessful, they knew that the only certain way to destroy the institution of slavery was to destroy the people who owned their bodies. In a different sort of way, it is a view that was also held by black revolutionaries, in the United States and abroad, in the twentieth century.

Kellie Carter Jackson’s brilliant new Force and Freedom constructs a bridge between these two moments—between the slave rebellions of the early Republic and the armed self-defense and revolutionary violence of twentieth-century black radicals—by filling in the less familiar history of how nineteenth-century abolitionists articulated their support for black armed self-defense and political violence. Her book stands well alongside other recent histories, such as Richard Blackett’s The Captive’s Quest for Freedom: Fugitive Slaves: Fugitive Slaves, the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, and the Politics of Slavery (2017); Martha Jones’s Birthright Citizens: A History of Race and Rights in Antebellum America (2018); and, Manisha Sinha’s The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition (2016). Like these, Carter Jackson places African Americans centrally as agentive in shaping the United States in the mid-nineteenth century. Moreover, her book serves as a kind of prequel to histories of armed resistance during the civil rights era, including Charles Cobb, Jr.’s This Nonviolence Stuff Will Get You Killed: How Guns Made the Civil Rights Movement Possible (2014), Lance Hill’s The Deacons of the Defense: Armed Resistance and the Civil Rights Movement (1964), and Akinyele Omowale Umoja’s We Will Shoot Back: Armed Resistance in the Mississippi Freedom Movement (2013). These works vividly describe how armed self-defense was used in discrete locales in Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi to advance democratic freedoms, in a militaristic forerunning of Oakland’s Black Panther Party.

What sets Carter Jackson’s book apart as both unique and challenging is her focus on how nineteenth-century black women and men specifically used and thought about political violence as a tool in defense of themselves. In this way, Carter Jackson shows how they—with varying degrees of fretfulness—muddled distinctions between small acts of private armed self-defense and more expressly political forms of violence. Her book therefore helps us to also better understand historical continuities between black perspectives on revolutionary violence in the early Republic and the era of civil rights.

Long before the National Rifle Association (NRA) came in to being, Americans of African descent understood the need for arms to protect themselves. They lived in a slaveholding society where escapees and free people were daily jeopardized by slavery’s federal statutory enforcements. The original Fugitive Slave Clause of the Constitution (Art. IV, § 2) stated:

No person held to service or labour in one state, under the laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in consequence of any law or regulation therein, be discharged from such service or labor, but shall be delivered up on claim of the party to whom such service or labour may be due.

This clause in practice deprived alleged runaways of anything like due process. It placed bounties on the heads of fugitives and was frequently a justification for the kidnapping of the freeborn and manumitted. Thus, while the Constitution ostensibly protected individual liberties, it also codified the coercive force necessary to keep enslavement intact. This is why abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison vehemently charged that the Constitution was “the source and parent of all the other atrocities—‘a covenant with death, and an agreement with hell.’”

It would of course eventually take violence to terminate this “covenant with death”—indeed, the deaths of over half a million Americans. All subsequent generations have sought to better understand the precise course that led to the Civil War, and for much of that time, the perspectives of whites on both sides, including white abolitionists such as Garrison, have dominated historical inquiry. Until quite recently, very little had been written about how black communities, enslaved, manumitted, and freeborn, thought about the politics of violence. Just what did autonomy and political freedoms mean to them? How precious was it to protect? How did their communities actively defy the laws that protected slavery?

Force and Freedom dives into the debates among disparate communities of free and enslaved people about when and how to use political violence. Contrary to Kanye West’s bizarre notion that slavery was “a choice,” blacks frequently fought their enslavement by whatever means available to them, including arms, and theorized openly about the salutary nature of political violence. Carter Jackson begins with freeborn abolitionist David Walker’s 1829 publication of his Appeal. The Appeal was a riotous Molotov cocktail. It radically called for slavery’s destruction. Walker’s flammable prose set planters on edge:

The whites want slaves, and want us for their slaves, but some of them will curse the day they ever saw us. As true as the sun ever shone in its meridian splendor, my colour will root some of them out of the very face of the earth. They shall have enough of making slaves of, and butchering, and murdering us in the manner which they have.

Two year after Walker published his clarion call for violent self-manumission, a version of it was attempted by the men and women who organized alongside Nat Turner in South Hampton County, Virginia. Turner’s band attempted to annihilate slaveowners and with them enslavement itself. Turner and Walker were both inspired by Haiti’s success with the violent and complete eradication of enslavement.

Following in the footsteps of Eugene Genovese’s influential Roll, Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made (1974), Carter Jackson offers further evidence that there was never such a thing as a negotiated acquiescence among U.S. slaves to the condition of their enslavement. But whereas Genovese argued that the numerical size of the enslaved population in the United States limited mass rebellions, Carter Jackson demonstrates that the U.S. freeborn population continuously fostered armed rebellion and that political violence was always a widespread topic of conversation among both enslaved and free blacks. And she connects armed actions, debates, and public conversations together to demonstrate a growing collective radicalism among black abolitionists.

Between 1830 and the start of the Civil War, freeborn blacks and former slaves collectively asserted their political freedoms in increasingly direct and forceful ways. By then, black abolitionist had arrived at a loose consensus that slavery’s systemic violence would require systemic retaliatory violence if it were to be destroyed. In other words, Carter Jackson shows that when and how to use political violence—rather than if—was the persistent topic of debate, and the answer was always a moving target, with varied opinions among abolitionists. Abolitionists of all stripes faced dangers, but black abolitionists faced more dangers. So they debated questions such as: What were the relative political advantages of various ways of deploying violence? When was the time to skirt an escapee across the Canadian border, when to raid a jail to rescue a fugitive, and when to have a shootout with slavecatchers?

A missing component in Force and Freedom is the religious context for abolitionists’ discussion of both moral suasion and armed violence. Many of the black abolitionists discussed by Carter Jackson based their ideas upon their black Protestantism. We must take seriously, for example, Frederick Douglass’s foray into becoming Methodist clergy, as well as Frances Ellen Watkins Harper’s and Harriet Tubman’s spiritual motivations for freedom. Though she writes of Henry Highland Garnet’s “Call to Rebellion” speech at the 1843 Negro Convention, Carter Jackson does not mention his “unflinching Calvinist ethics” that framed his understanding of human liberty. My point, borrowing from an unpublished paper by historian James Bratt on Garnet’s ethic of self-defense, is that there were many ways that political violence was understood by abolitionists, and religion influenced them all. My criticism here is aimed less at Carter Jackson than at U.S. cultural studies in general, which tends to insufficiently explore how religion illuminates African American history. In this case, religion motivated some people to armed insurrection—included Nat Turner—even as it informed broader conversations about whether political violence was justifiable, and, if so, when. Radical white abolitionist John Brown’s last words during his 1859 sentencing for trying to capture the federal Armory at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, testifies to the religiosity that prevailed:

This court acknowledges, as I suppose, the validity of the law of God. I see a book kissed here which I suppose to be the Bible, or at least the New Testament. That teaches me that all things whatsoever I would that men should do to me, I should do even so to them. It teaches me, further, to ‘remember them that are in bonds, as bound with them.’ I endeavored to act up to that instruction. I say, I am yet too young to understand that God is any respecter of persons. I believe that to have interfered as I have done as I have always freely admitted I have done in behalf of His despised poor, was not wrong, but right. Now, if it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice, and mingle my blood further with the blood of my children and with the blood of millions in this slave country whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel, and unjust enactments, I submit; so let it be done!

Force and Freedom would have also been enriched by a sustained engagement with Cedric J. Robinson’s argument, in Black Movements in America (1997), that freedom meant slightly different things among those who were enslaved and those who had been born free. For Robinson, this meant that views about the aims of force could be sorted into class tiers: a privileged one—mainly what is covered in Carter Jackson’s history—which aimed for a use of violence that would perfect rather than abolish the existing order; and one held among the masses, who saw little worth preserving and hoped for the violence of a cleansing flood. Whether or not Robinson was absolutely right in his assessment is a matter of debate, but he was correct that the sometimes-uneasy dialogue between the freeborn and the enslaved shaped the terrain upon which the black politics of the Civil War and post-Emancipation eras have played out.

Nonetheless, Carter Jackson’s rich history stands as evidence that, whatever differences of opinion existed between freeborn and enslaved blacks, their views were more similar to each other’s than they were to those of even many abolitionist whites. John Brown notwithstanding, as W. E. B. DuBois noted in Black Reconstruction in America (1935), most whites—including abolitionists—were terrified of the idea of armed African Americans:

Arms in the hands of the Negro aroused fear both North and South. . . . But, it was the silent verdict of all America that Negroes must not be allowed to fight for themselves. They were, therefore, dissuaded from every attempt at self-protection or aggression by their friends as well as their enemies.

And that has largely remained the case, as Robert F. Williams noted in 1962 in Negroes with Guns:

When people say that they are opposed to Negroes ‘resorting to violence’ what they really mean is that they are opposed to Negroes defending themselves and challenging the exclusive monopoly of violence practiced by white racists.

This is perhaps most dramatically embodied by the NRA’s persistent silence on the issue of black gun ownership. Williams directly challenged the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and Congress on Racial Equality’s reliance on nonviolent protest as, in effect, a form of false consciousness. And set within this genealogy, it becomes clear that Malcolm X’s speeches on armed self-defense were not an aberration, but in keeping with a long tradition.

In James McBride’s 2013 National Book Award–winning novel The Good Lord Bird, Onion, the chief protagonist, offers this observation of John Brown:

He knowed what he wanted to do. But as to the exactness of it—and I knowed many has studied it and declared this and that and the other on the subject—Old John Brown didn’t know exactly what he was gonna do from sunup to sundown on the slavery question.

I draw this quote in to return to the point that there is a fundamental difference between acts of armed self-defense and revolutionary violence to overthrow a state. Here a distinction must be made—and although black radical abolitionists were not always fully transparent about the distinction in their public writing and speaking, they were certainly attentive to it in private. John Brown’s plan to capture the arsenal at Harpers Ferry would have come nowhere close to hobbling the U.S. government; he would have needed to control the mass manufacturing of weapons. This is why black abolitionists he attempted to recruit, including Frederick Douglass, were so cautious about his plan. They feared, with varying degrees of consternation, that attacking the state might bring even more hell into their lives. Small acts of armed resistance in the cause of freedom were one thing, full-scale war was another.

Brown’s raid, however, anticipated—and likely sped—the nation’s unraveling over enslavement. The dam, which black abolitionists had steadily tried to crack, finally broke. And when it burst, 600,000 people lay dead. Carter Jackson’s book does not consider this question of scale and cost, but it is one that we as democratic denizens must always keep in mind as we critically think through the levels of armed resistance we are willing to engage in freedom’s name.

Randal Maurice Jelks is an awarding winning Professor of American Studies and African and African American Studies at the University of Kansas. His most recent book is Faith and Struggle in the Lives of Four African Americans: Ethel Waters, Mary Lou Williams, Eldridge Cleaver, and Muhammad Ali. This piece has been republished here with permission.

by DGR News Service | Aug 23, 2019 | Direct Action, People of Color & Anti-racism, Strategy & Analysis, White Supremacy

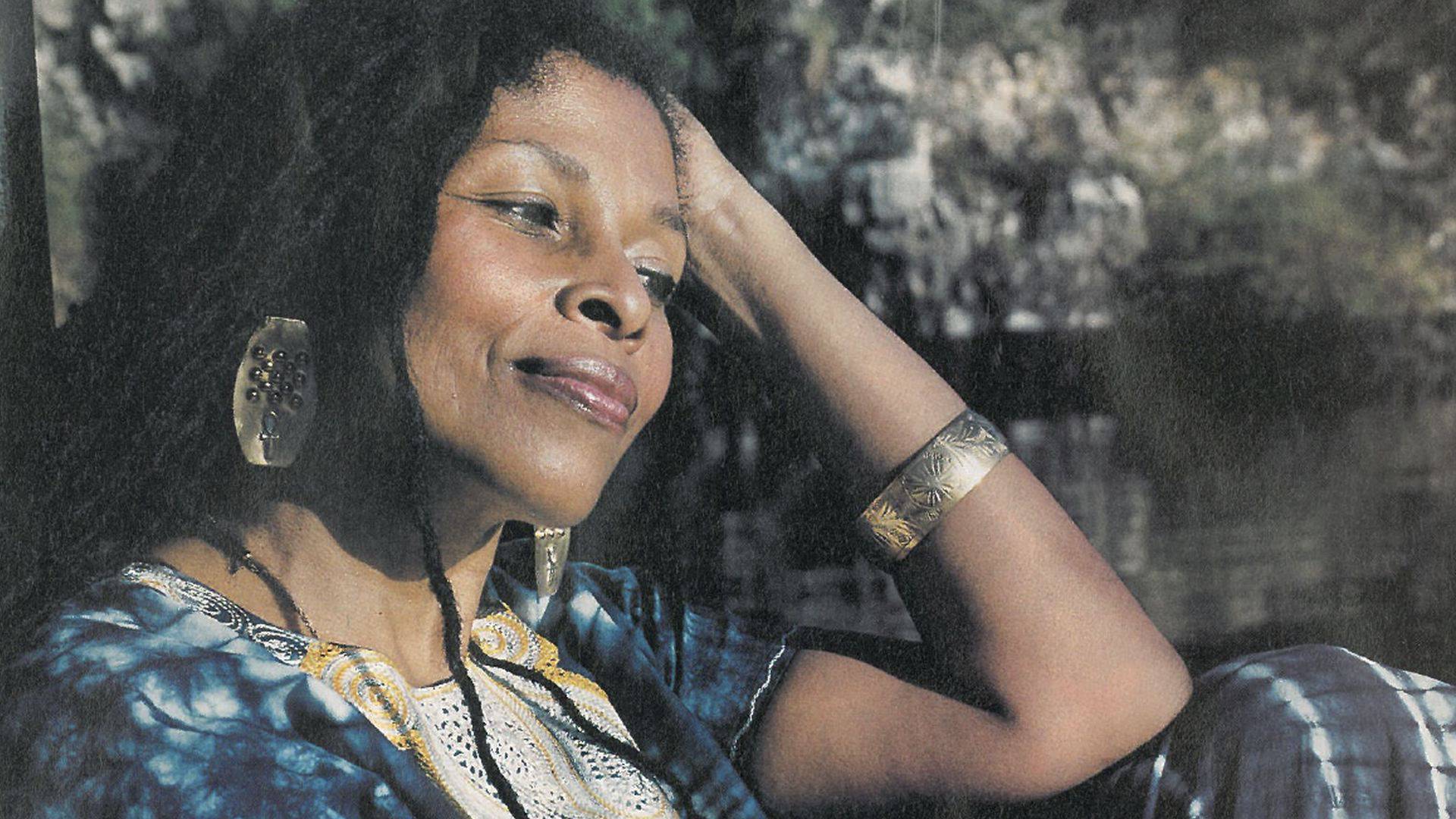

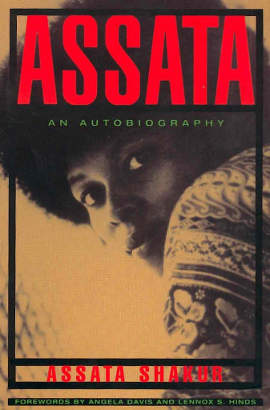

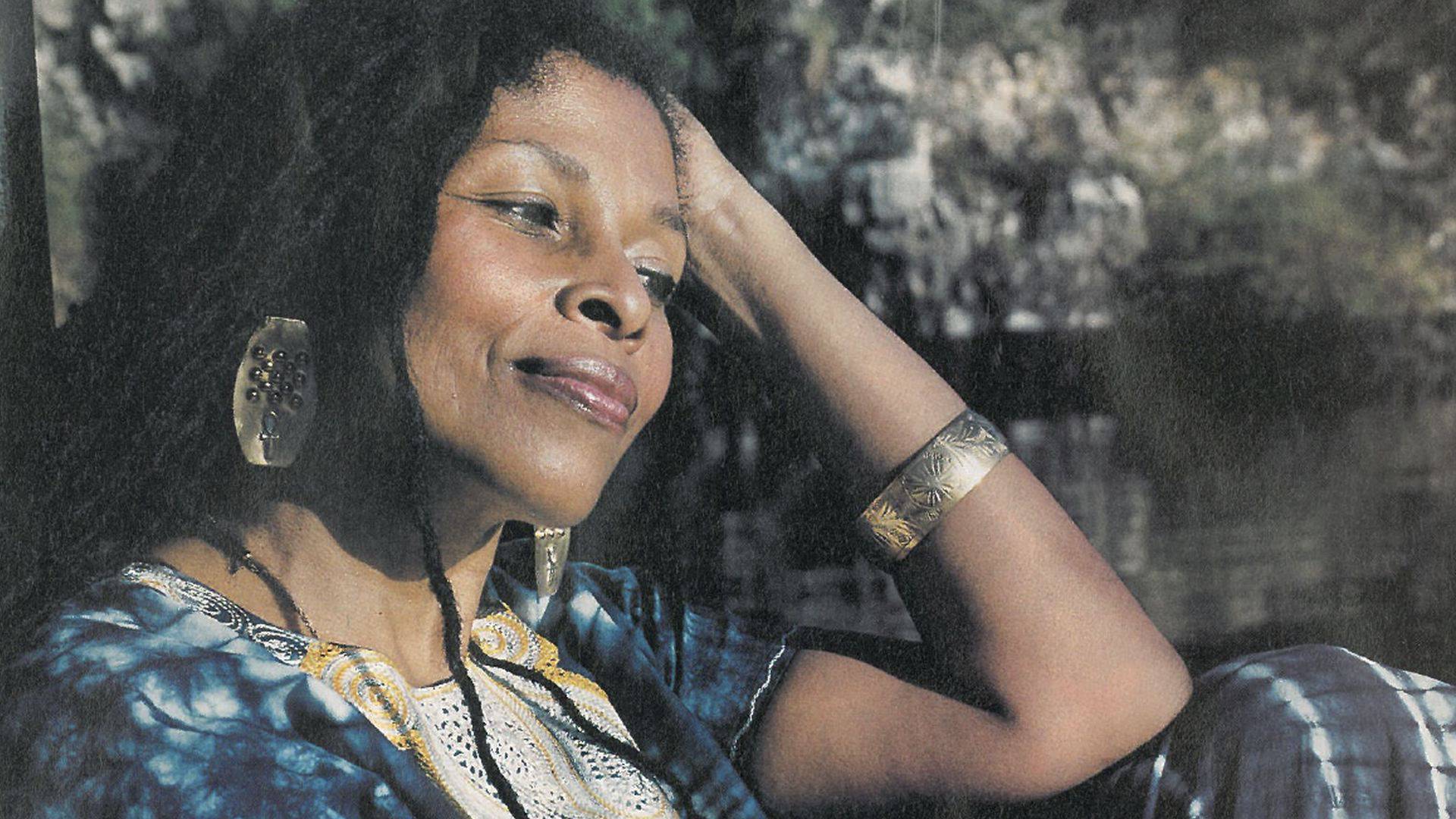

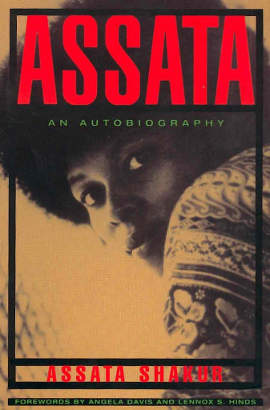

By Norris Thomlinson / Originally published on DGR Hawaii / Featured image by Angela Davis, CC BY 4.0

Once you understand something about the history of a people, their heroes, their hardships and their sacrifices, it’s easier to struggle with them, to support their struggle. For a lot of people in this country, people who live in other places have no faces.”

–Assata Shakur

A World Apart

I grew up in the same country as Assata Shakur, but as a poor black woman, her autobiography reveals an experience a world apart from my own middle class, white male upbringing. She ably captures these differences in a series of anecdotes revealing that she did in fact grow up in a different country: “amerika”, while I enjoyed the facades of democracy, peace, and justice in America. I’ve been aware of the shocking statistics of incarceration rates of people of color, disproportionate distribution of wealth, heartbreaking inequity in education systems, increased exposure to toxins, decreased lifespans, and on and on. But I haven’t read much by black authors about their personal experiences navigating these systems of oppression and injustice. Shakur’s autobiography is surprisingly easy to read and even enjoyable, despite and because of its humorous tragedy, and makes an excellent introduction to a different reality for those of us born into white and/or male privilege.

Beyond her personal insights into the impacts of class, race, and gender, Shakur shares her astute political analysis, and draws a logical line from her childhood acceptance of the systems of America to her adult revolutionary struggle against amerika. Based on voracious reading, observation of the world around her, and careful thinking, she developed a radical analysis of structures of power and how to fight them. She understands that “What we are taught in the public school system is usually inaccurate, disorted, and packed full of outright lies” and that “Belief in these myths can cause us to make serious mistakes in analyzing our current situation and in planning future action.” She links the “interventions” and invasions of the US abroad to its theft of indigenous land and oppression of people of color at home.

Shakur knows none of this is an accident, fixable by asking those in power to change their ways. The people need to fight back, using violence if necessary:

“…the police in the Black communities were nothing but a foreign, occupying army, beating, torturing, and murdering people at whim and without restraint. I despise violence, but i despise it even more when it’s one-sided and used to oppress and repress poor people.”

Horizontal Hostility

Shakur explains that while those in power use schooling, media, the police, and COINTELPRO to divide and conquer those who might oppose them, the solution is simple (though not necessarily easy):

“The first thing the enemy tries to do is isolate revolutionaries from the masses of people, making us horrible and hideous monsters so that our people will hate us.”

“It’s got to be one of the most basic principles of living: always decide who your enemies are for yourself, and never let your enemies choose your enemies for you.”

“Some of the laws of revolution are so simple they seem impossible. People think that in order for something to work, it has to be complicated, but a lot of times the opposite is true. We usually reach success by putting the simple truths that we know into practice. The basis of any struggle is people coming together to fight against a common enemy.”

“Arrogance was one of the key factors that kept the white left so factionalized. I felt that instead of fighting together against a common enemy, they wasted time quarreling with each other about who had the right line.”

Parallels with Deep Green Resistance

It seems many of Shakur’s insights directly informed the Deep Green Resistance book, or the authors came to the same conclusions after studying similar history. For example, Shakur clearly states the need for a firewall between an aboveground and a belowground:

“An aboveground political organization can’t wage guerrilla war anymore than an underground army can do aboveground political work. Although the two must work together, they must have completely separate structures, and any links between the two must remain secret.”

She sees one of the main flaws of the Black Panther Party as having mixed aboveground political work with a militancy more appropriate for a belowground, especially in attempting to defend their offices at all costs against police raids. While understandable as symbolic of their pride and a willingness to fight for what was theirs, the simple reality was that the Panthers weren’t ready to go up against the military might of the state, and it was suicide to attempt to hold this symbolic territory. In asymmetric warfare, you must give way where the enemy is strong, and strike where the enemy is weak.

Perhaps most importantly, Shakur emphasizes several times the necessity of discipline and of careful, logical, long-term planning. She recounts an embarassing situation where she and some friends smoke marijuana in a public park while carrying radical literature, risking beatings or arrest by relinquishing full control of their faculties. After another revolutionary group helps them out of their precarious situation, a dazed Shakur resolves to take the struggle more seriously. This contrasts sharply with the drug- and sex-fueled Weathermen and their contemporaneous white radicals, whose self-indulgence in machismo and rebelliousness resulted in a strategy of instigating fistfights and rioting in the streets.

It reassures me that so many of Shakur’s hard-won lessons are foundational to Deep Green Resistance, as it reinforces my confidence in DGR as a well-researched analysis of historical movements and a solid guide to proceeding from here:

“There were sisters and brothers who had been so victimized by amerika that they were willing to fight to the death against their oppressors. They were intelligient, courageous and dedicated, willing to make any sacrifice. But we were to find out quickly that courage and dedication were not enough. To win any struggle for liberation, you have to have the way as well as the will, an overall ideology and strategy that stem from a scientific analysis of history and present conditions.

[…]

Every group fighting for freedom is bound to make mistakes, but unless you study the common, fundamental laws of armed revolutionary struggle you are bound to make unnecessary mistakes. Revolutionary war is protracted warfare. It is impossible for us to win quickly. […] One of the hardest lessons we had to learn is that revolutionary struggle is scientific rather than emotional. I’m not saying that we shouldn’t feel anything, but decisions can’t be based on love or on anger. They have to be based on the objective conditions and on what is the rational, unemotional thing to do.”

Read This Book

If you want to better understand racism, read this book. If you enjoy a well-told story of a unique and fascinating life, read this book. If you’re interested in historical revolutionary movements, read this book. If you’re interested in a modern revolutionary movement, read this book, read Deep Green Resistance, and let’s start putting the theory into practice.

“It crosses my mind: i want to win. i don’t want to rebel, i want to win.”

–Assata Shakur

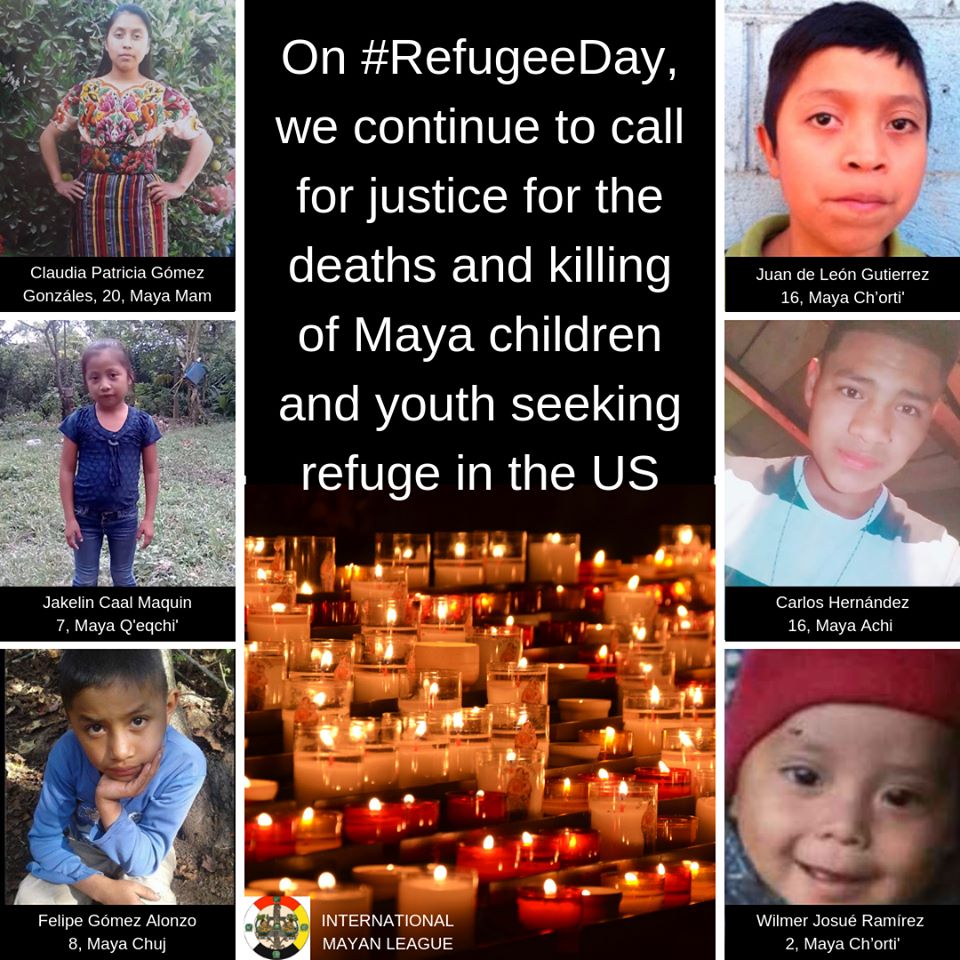

by DGR News Service | Jun 27, 2019 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Colonialism & Conquest, People of Color & Anti-racism, Repression at Home

Editors Note: the international refugee crisis is driven by war, imperialism, and destruction of the planet. In other words, it is driven by civilization, or “the culture of empire.” DGR is opposed to empire and we see the refugee crisis as a humanitarian emergency. We believe that the best way to fight this crisis is to fight it’s underlying cause, by dismantling civilization. Learn more on the DGR website.

By the International Mayan League

www.mayanleague.org

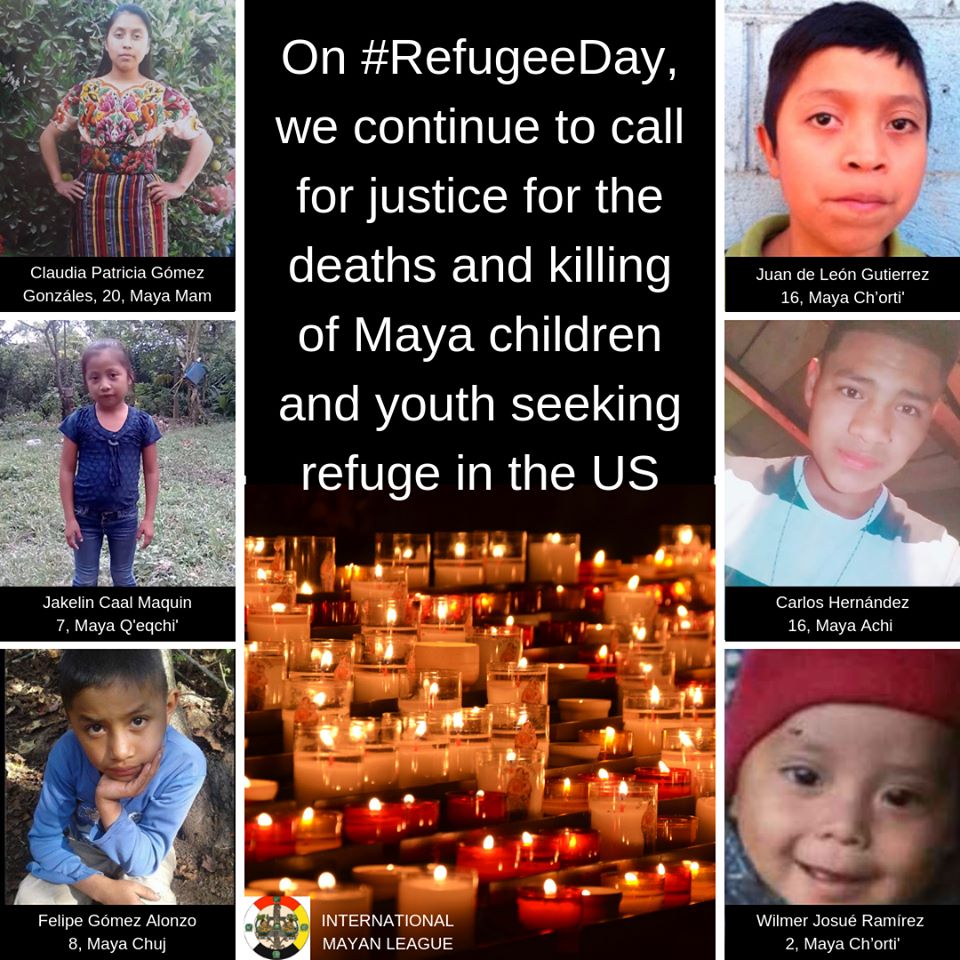

Washington, D.C. – May 16, 2019 – Today, the International Mayan League denounces the latest victim of death and murder at the U.S/Mexico border, a 2 ½ year-old toddler, a boy from Chiquimula, Guatemala. This tragic loss comes on the heels of the death of 16-year-old Juan de León Gutiérrez of the Maya Ch’orti’ people – also from Chiquimula. For the last year our people have been under constant attacks at the border. Since May 2018 we have lost five lives from Guatemala. First, Claudia Patricia Gómez González (Maya Mam) 20 years old who was shot in the head by a Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) Agent; then 7-year-old Jakelin Caal (Maya Q’eqchi’), and 8-year-old boy Felipe Gomez Alonzo (Maya Chuj) both died in December while in CBP custody. Now, we have lost two more lives. How many more children must die before there is collective outrage, actions, denouncements? How many more times do we need to say this is a crisis specifically affecting indigenous children and youth?

We, indigenous peoples, are the majority in Guatemala and continue to be disproportionately impacted because our basic human rights are denied by the Guatemalan government and all sectors of society. We are forced to flee only to encounter inhumane treatment and human rights violations at the U.S./Mexico border in violation of international law. The Guatemalan and the United States governments must be held accountable for the deaths of our children. Impunity for their deaths is not an option and we demand justice and peace for their families.

Children, explicitly indigenous children, are some of the most victimized. In fiscal year 2019 alone, 19,991[1] Guatemalan unaccompanied children have been apprehended at the border. The number of Guatemalan family units has soared to 114,778, the highest for all the Central American countries[2]. Considering indigenous peoples are the majority in Guatemala, contrary to government admission, we strongly believe that these statistics reflect that thousands of Maya children and families are seeking refuge. Their indigenous identities must be acknowledged and documented.

Each indigenous child whose life has been stolen was forced to migrate because they are the most affected by centuries of structural inequality and discrimination in Guatemala. They often have no future in their rural and extremely impoverished communities. Many have little access to formal education and likely only speak their native language, an additional barrier that hinders their communication with authorities or service providers when migrating. We are outraged by these tragedies and demand the following from the government of the United States. There must be exhaustive, fair and transparent investigations by the Office of the Inspector General, Department of Homeland Security into all the deaths at the border; a dialogue with leaders of the Guatemalan Maya diaspora for the development of humane immigration policies; and recognition and implementation of the U.N. Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and the American Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples as the bare minimum standard for the respect and protection of indigenous peoples’ rights in forced migration.

Almost exactly at the 1-year anniversary of the murder of Claudia Patricia Gómez González of the Maya Mam Nation, we are reliving another nightmare, the death of a toddler. We are tired of being treated as if our lives do not matter. We will not stand idly by as our children are murdered by inhumane policies and practices rooted in hatred, fear, and racism.

[1] https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/sw-border-migration/usbp-sw-border-apprehensions

[2] Ibid.

The International Mayan League has been working in defense of indigenous human rights for many years, and since last year, trying to raise awareness that most of the children, youth, and families coming from Guatemala are indigenous. They are a Mayan women-led grassroots organization working directly with and for their people, and are entirely volunteer-based.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 15, 2018 | People of Color & Anti-racism

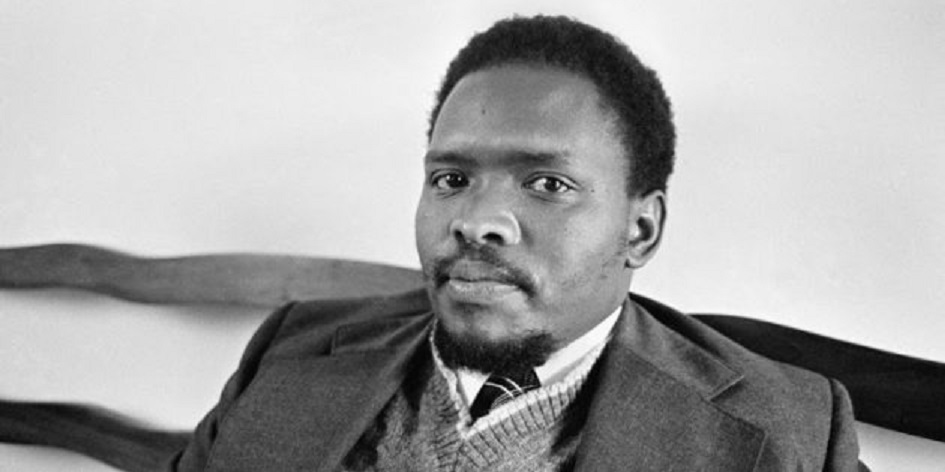

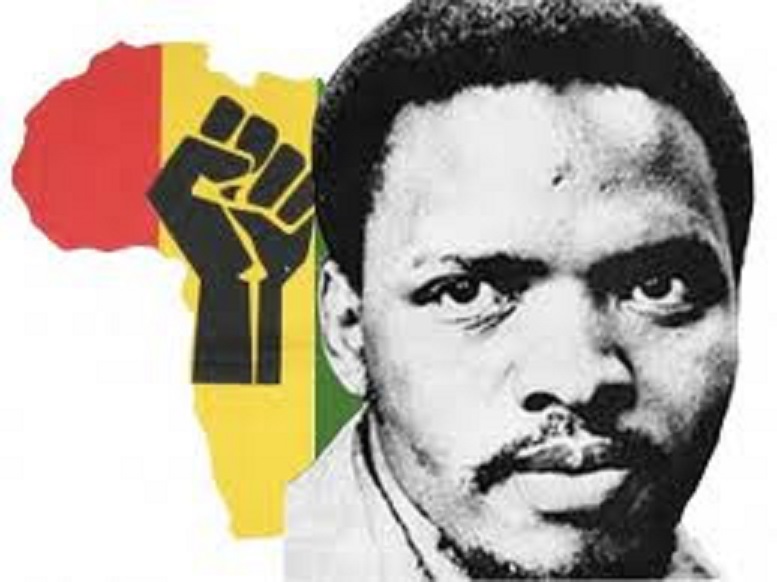

Editor’s note: This is the paper produced for a South African Student Organisation Leadership Training Course in December 1971.

by Steve Biko

We have defined blacks as those who are by law or tradition politically, economically and socially discriminated against as a group in the South African society and identifying themselves as a unit in the struggle towards the realization of their aspirations.

This definition illustrates to us a number of things:

- Being black is not a matter of pigmentation–being black is a reflection of a mental attitude.

- Merely by describing yourself as black you have started on a road towards emancipation, you have committed yourself to fight against all forces that seek to use your blackness as a stamp that marks you out as a subservient being.

From the above observations therefore, we can see that the term black is not necessarily all-inclusive, i.e. the fact that we are all not white does not necessarily mean that we are all black. Non-whites do exist and will continue to exist for quite a long time. If one’s aspiration is whiteness but his pigmentation makes attainment of this impossible, then that person is a non-white. Any man who calls a white man “baas,” any man who serves in the police force or security branch is ipso facto a non-white. Black people–real black people–are those who can manage to hold their heads high in defiance rather than willingly surrender their souls to the white man.

Briefly defined therefore, Black Consciousness is in essence the realization by the black man of the need to rally together with his brothers around the cause of their oppression–the blackness of their skin–and to operate as a group in order to rid themselves of the shackles that bind them to perpetual servitude. It seeks to demonstrate the lie that black is an aberration from the “normal” which is white. It is a manifestation of a new realization that by seeking to run away from themselves and to emulate the white man, black are insulting the intelligence of whoever created them black. Black Consciousness, therefore takes cognizance of the deliberateness of the God’s plan in creating black people black.

It seeks to infuse the black community with a new-found pride in themselves, their efforts, their value systems, their culture, their religion and their outlook to life. The interrelationship between the consciousness of the self and the emancipatory programme is of a paramount importance. Blacks no longer seek to reform the system because so doing implies acceptance of the major points around which the system revolves. Blacks are out to completely transform the system and to make of it what they wish. Such a major undertaking can only be realized in an atmosphere where people are convinced of the truth inherent in their stand. Liberation therefore is of paramount importance in the concept of Black Consciousness, for we cannot be conscious of ourselves and yet remain in bondage. We want to attain the envisioned self which is a free self.

The surge towards Black Consciousness is a phenomenon that has manifested itself throughout the so-called Third World. There is no doubt that discrimination against the black man the word over fetches its origin from the exploitative attitude of the white man. Colonization of white countries by whites has throughout history resulted in nothing more than sinister than mere cultural or geographical fusion at worst, or language bastardization at best.

It is true that the history of weaker nations is shaped by bigger nations, but nowhere in the world today do we see whites exploiting whites on scale even remotely similar to what is happening in South Africa. Hence, one is forced to conclude that it is not coincidence that black people are exploited. It was a deliberate plan which has culminated in even so-called black independent countries not attaining any real independence.

With this background in mind we are forced, therefore, to believe that it is a case of haves against have-nots where whites have been deliberately made haves and black have-nots.

There is for instance no worker in the classical sense among whites in South Africa, for even the most downtrodden white worker still has a lot lose if the system is changed. He is protected by several laws against competition at work from the majority. He has a vote and he uses it to return the Nationalist Government to power because he sees them as the only people who, through job reservation laws, are bent on looking after his interests against competition with the “Natives.”

It should therefore be accepted that analysis of our situation in terms of one’s colour at once takes care of the greatest single determinant for political action–i.e. colour–while also validly describing the blacks as the only real workers in South Africa. It immediately kills all suggestions that there could ever be effective rapport between the real workers, i.e. blacks, and the privileged white workers, since we have shown that the latter are the greatest supporters of the system.

True enough, the system has allowed so dangerous an anti-black attitude to build up amongst whites, who are economically nearest to the blacks, demonstrate the distance between themselves and the blacks by an exaggerated reactionary attitude towards blacks. Hence the greatest anti-black feeling is to be found amongst the very poor whites whom the Class Theory calls upon to be with black workers in the struggle for emancipation. This is the kind of twisted logic that Black Consciousness approach seeks to eradicate.

In terms of the Black Consciousness approach we recognize the existence of one major force in South Africa. This is White Racism. It is the one force against which all of us are pitted. It works with unnerving totality, featuring both on the offensive and in our defence. Its greatest ally to date has been the refusal by us to progressively lose ourselves in a world of colourlessness and amorphous common humanity, whites are deriving pleasure and security in entrenching white racism and further exploiting the minds and bodies of the unsuspecting black masses. Their agents are ever present amongst us, telling that it is immoral to withdraw into a cocoon, that dialogue is the answer to our problem and that it is unfortunate that there is white racism in some quarters but you must that things are changing.

These in fact are the greatest racists for they refuse to credit us any intelligence to know what we want. Their intentions are obvious; they want to be barometers by which the rest of the white society can measure feelings in the black world. This then is what makes us believe that white power presents itself as a totality not only provoking us but also controlling our response to the provocation. This is an important point to note because it is often missed by those who believe that there are a few good whites. Sure there are few good whites just as much as there are a few bad blacks.

However what we are concerned here with is group attitudes and group politics. The exception does not make a lie of a rule–it merely substantiates it. The overall analysis therefore, based on the Hegelian theory of dialectic materialism, is as follows. That since the thesis is a white racism there can only be one valid antithesis, i.e. a solid black unity, to counterbalance the scale. If South Africa is to be a land where black and white live together in harmony without fear of group exploitation, it is only when these two opposites have interplayed and produced a viable synthesis of ideas and modus vivendi. We can never wage any struggle without offering a strong counterpoint to the white racism that permeate our society so effectively.

One must immediately dispel the thought that Black Consciousness is merely a methodology or a means towards an end. What Black Consciousness seeks to do is to produce at the output end of the process real black people who do not regard themselves as the appendages to white society. This truth cannot be reserved.

We do not need to apologize for this because it is true that the white systems have produced throughout the world a number of people who are not aware that they too are people. Our adherence to values that we set for ourselves can also not be reversed because it will always be a lie to accept white values as necessarily the best. The fact that a synthesis may be attained only relates to adherence to power politics. Someone somewhere along the line will be forced to accept the truth and here we believe that ours is the truth.

The future of South Africa in the case where blacks adopt Black Consciousness is the subject for concern especially among initiates. What do we do when have attained our Consciousness ? Do we propose to kick whites out ? I believe personally that the answers to these questions ought to be found in the SASO Policy Manifesto and in our analysis of the situation in South Africa. We have defined what we mean by true integration and the very fact that such a definition exists does illustrate what our standpoint is. In any case we are much more concerned about what is happening now, than will happen in the future. The future will always be shaped by the sequence of present-day events.

The importance of black solidarity to the various segments of the black community must not be understated. There have been in the past a lot of suggestions that there can be no viable unity amongst blacks because they hold each other in contempt. Coloureds despise Africans because they (the former), by their proximity to the Africans, may lose the chances of assimilation into the white world. Africans despise the Coloureds and Indians for a variety of reasons. Indians not only despise Africans but in many instances also exploit the Africans in job and shop situations.

All these stereotype attitudes have led to mountainous inter-group suspicions amongst the blacks.

What we should at all times look at is the fact that:

- We are all oppressed by the same system.

- That we are oppressed to varying degrees is a deliberate design to stratify us not only socially but also in terms of the enemy’s aspirations.

- Therefore it is to be expected that in terms of the enemy’s plan there must be this suspicion and that if we are committed to the problem of emancipation to the same degree it is part of our duty to bring to the black people the deliberateness of the enemy’s subjugation scheme.

- That we should go on with our programme, attracting to it only committed people and not just those eager to see an equitable distribution of groups amongst our ranks. This is a game common amongst liberals. The one criterion that must govern all our action is commitment.

Further implications of Black Consciousness are to do with correcting false images of ourselves in terms of culture, Education, Religion, Economics. The importance of this also must not be understated. There is always an interplay between the history of people i.e. the past, their faith in themselves and hopes for their future. We are aware of the terrible role played by our education and religion in creating amongst us a false understanding of ourselves. We must therefore work out schemes not only to correct this, but further to be our own authorities rather than wait to be interpreted by others.

Whites can only see us from the outside and as such can never extract and analyze the ethos in the black community. In summary therefore one need only refer this house to the South African Student Organisation Policy Manifesto which carries most of the salient points in the definition of the Black Consciousness. I wish to stress again the need for us to know very clearly what we mean by certain terms and what our understanding is when we talk of Black Consciousness.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 13, 2018 | People of Color & Anti-racism

Siwatu-Salama Ra Sentenced to Two Years in Prison During High-Risk Pregnancy

by Sierra Club

Detroit, MI — Earlier this month, Siwatu-Salama Ra, Co-Director of the East Michigan Environmental Action Council (EMEAC), was sentenced to two years in prison for defending herself and her young child from an attacker. Siwatu is a member of the Sierra Club family, the daughter of Rhonda Anderson, a Sierra Club organizing manager in Detroit with nearly twenty years experience. Siwatu’s leadership at EMEAC has helped build community power through environmental justice education, youth development, and collaborative relationship building — and Siwatu has emerged as a national and international environmental justice leader, participating in numerous conferences like COP21 in Paris.

Siwatu is 26, the mother of a 3 year old, and is 7 months pregnant. She came into contact with the criminal justice system because of an incident in which an attacker threatened to strike Siwatu, her three-year-old daughter and her mother with a car. Siwatu showed her legal, permitted, unloaded handgun in an attempt to scare off the attacker, as allowed by Michigan’s Stand Your Ground law. She did not fire the unloaded gun and no one was harmed.

Siwatu was unjustly arrested, tried and convicted of felony gun charges and sentenced to two years in prison. She is now experiencing a high-risk pregnancy in prison, and could be forced to deliver her child while incarcerated.

Support Siwatu Salama Ra at the Siwatu Freedom Fund

Get involved in the Siwatu Freedom Team and write her letters

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 11, 2018 | People of Color & Anti-racism

by Steve Biko

One of the most difficult things to do these days is to talk with authority on anything to do with African Culture. Somehow Africans are not expected to have any deep understanding of their own culture or even of themselves. Other people have become authorities on all aspects of the African life or to be more accurate on Bantu life. Thus we have the thickest of volumes on some of the strangest subjects – even “the feeding habits of the Urban Africans,” a publication by a fairly “liberal” group, Institute of Race Relations.

In my opinion, it is not necessary to talk with Africans about African culture. However, in the light of the above statements one realises that there is so much confusion sown, not only amongst casual non-African readers, but even amongst Africans themselves, that perhaps sincere attempt should be made emphasising the authentic cultural aspects of the African people by Africans themselves.

Since that unfortunate date – 1652 – we have been experiencing a process of acculturation. It is perhaps presumptuous to call it “acculturation” because this term implies a fusion of different cultures.

In our case this fusion has been extremely one-sided. The two major cultures that met and “fused” were the African Culture and the Anglo-Boer Culture.

Whereas the African culture was unsophisticated and simple, the Anglo-Boer culture had all the trappings of a colonialist culture and therefore was heavily equipped for conquest.

Where they could, they conquered by persuasion, using a highly exclusive religion that denounced all other Gods and demanded a strict code of behaviour with respect to clothing, education ritual and custom. Where it was impossible to convert, fire-arms were readily available and used to advantage. Hence the Anglo-Boer culture was the more powerful culture in almost all facets. This is where the African began to lose a grip on himself and his surroundings.

Thus in taking a look at cultural aspects of the African people one inevitably finds himself having to compare. This is primarily because of the contempt that the “superior” culture shows towards the indigenous culture. To justify its exploitative basis, the Anglo Boer culture has at all times been directed at bestowing an inferior status to all cultural aspects of the indigenous people.

I am against the belief that African culture is time-bound, the notion that with the conquest of the African all his culture was obliterated. I am also against the belief that when one talks of African culture one is necessarily talking of the pre-Van Riebeeck culture. Obviously the African has had to sustain severe blows and may have been battered nearly out of shape by the belligerent cultures it collided with, yet in essence even today, one can easily find the fundamental aspects of the pure African culture in the present day African. Hence in taking a look at African culture, I am going to refer as well to what I have termed the modern African culture.

One of the most fundamental aspect of our culture is the importance we attach to Man. Ours has always been a Man-centred society. Westerners have in many occasions been surprised at the capacity we have for talking to each other – not for the sake of arriving at a particular conclusion but merely to enjoy the communication for its own sake. Intimacy is a term not exclusive for particular friends but to a whole group of people who find themselves either through work or through residential requirements.

In fact, in the traditional African culture, there is no such thing as two friends. Conversation groups were more or less naturally boys whose job was to look after cattle periodically meeting at popular spots to engage in conversation about their cattle, girlfriends, parents, heroes, etc. All commonly shared their secrets, joys and woes. No one felt unnecessarily an intruder into someone else’s business. The curiosity manifested was welcome. It came out of a desire to share. This pattern one would find in all age groups. House visiting was always a feature of the elderly folk’s way of life. No reason was needed as a basis for visits. It was always part of our deep concern for each other.

These are things never done in the Westerner’s culture. A visitor to someone’s house, with the exception of friends, is always met with the question “what can I do for you?” This attitude to see people not as themselves but as agents for some particular function either to one’s disadvantage or advantage is foreign to us. We are not a suspicious race. We believe in the inherent goodness of man. We enjoy man for himself. We regard our living together not as an unfortunate mishap warranting endless competition among us but as a deliberate act of God to make us a community of brothers and sisters jointly involved in the quest for a composite answer to the varied problems of life. Hence in all we do we always place Man first and hence all our action is usually jointly community oriented action rather than the individualism which is the hallmark of the capitalist approach. We always refrain from using people as stepping stones. Instead we are prepared to have a much slower progress in an effort to make sure that all of us are marching to the same tune.

Nothing dramatises the eagerness of the African to communicate with each other more than their love for song and rhythm. Music in the African culture features in all emotional states. When we go to work, we share the burdens and pleasures of the work we are doing through music. This particular facet strangely enough has filtered through the present day. Tourists always watch with amazement the synchrony of music and action as African working at a road side use their picks and shovels with well-timed precision to the accompaniment of a background song. Battle songs were a feature of the long march to war in the olden days. Girls and boys never played any games without using music and rhythm as its basis. in other words with Africans, music and rhythm were a not luxuries but part and parcel of our way of communication. Any suffering we experienced was made much more real by song and rhythm. There is no doubt that the so called “Negro spirituals” sung by Black slaves in the States as they toiled under oppression were indicative of their African heritage…

Attitudes of Africans to property again show just how un-individualistic the African is. As everybody here knows, Africans always believe in having many villages with a controllable number of people in each rather than the reverse. This obviously was a requirement to suit the needs of a community-based and man-centred society. Hence most things where jointly owned by the group, for instance there was no such thing as individual land ownership. The land belonged to the people and was under the control of the local chief on behalf of the people. When cattle went to graze it was on an open veld and not on anybody’s specific farm.

Farming and agriculture, though on individualistic family basis, had many characteristics of joint efforts. Each person could by a simple request and holding a special ceremony, invite neighbours to come and work on his plots. This service was returned in kind and no remuneration was ever given.

Poverty was a foreign concept. This could only be really brought about to the entire community by an adverse climate during a particular season. It never was considered repugnant to ask one’s neighbours for help if one was struggling. In almost all instances there was help between individuals, tribe and tribe, chief and chief, etc. even in spite of war.

Another important aspect of the African culture is our mental attitude to problems presented by life in general. Whereas the Westerner is geared to use a problem-solving approach following very trenchant analyses, our approach is that of situation-experiencing. I will quote from Dr. Kaunda to illustrate this point:

“The westerner has an aggressive mentality. When he sees a problem he will not rest until he has formulated some solution to it. He cannot live with contradictory ideas in his mind; he must settle for one or the other or else evolve a third idea in his mind, which harmonises or reconciles the other two. And he is vigorously scientific in rejecting solutions for which there is no basis in logic. He draws a sharp line between the natural and the supernatural, the rational and non-rational, and more often than not, he dismissed the supernatural and non-rational as superstition…

“Africans, being a pre-scientific people do not recognise any conceptual cleavage between the natural and supernatural. They experience a situation rather than face a problem. By this I mean they allow both the rational and non-rational elements to make an impact upon them and any action they may take could be described more as a response of the total personality of the situation than the result of some mental exercise.”

This I find a most apt analysis of the essential difference in the approach to life of these two groups. We as a community are prepared to accept that nature will have its enigmas which are beyond our powers to solve. Many people have interpreted this attitude as lack of initiative and drive yet in spite of my belief in the strong need for scientific experimentation, I cannot help feeling that more time also should be spent in teaching man and man to live together and that perhaps the African personality with its attitude of laying less stress on power and more stress on man is well on the way to solving our confrontation problems.

All people are agreed that Africans are a deeply religious race. In the various forms of worship that one found throughout the Southern part of our continent, there was at least a common basis. We all accepted without any doubt the existence of a God. We had our own community of saints. We believed – and this was consistent with our views of life – that all people who died had a special place next to God. We felt that communication with God, could only be through these people. We never knew anything about hell – we do not believe that God can create people only to punish them eternally after a short period on earth.

Another aspect of religious practices was the occasion of worship. Again we did not believe that religion could be featured as a separate part of our existence on earth. It was manifest in our daily lives. We thanked God through our ancestors before we drank beer, married, worked, etc. we would obviously find it artificial to create special occasions for worship. Neither did we see it logical to have a particular building in which all worship would be conducted. We believed that God was always in communication with us and therefore merited attention everywhere and anywhere.

It was the missionaries who confused our people with their new religion. By some strange logic, they argued that theirs was a scientific religion and ours was mere superstition in spite of the biological discrepancies so obvious in the basis of their religion. They further went on to preach a theology of existence of hell, scaring our fathers and mothers with stories about burning in eternal flames and gnashing of teeth and grinding of bone. The cold cruel religion was strange to us but our fore-fathers were sufficiently scared of the unknown impending anger to believe that it was worth a try. Down went our cultural values!

Yet it is difficult to kill the African heritage. There remains, in spite of the superficial cultural similarities between the detribalised and Westerner, a number of cultural characteristics that mark out the detribalised as an African…

The advent of the Western culture had changed our outlook almost drastically. No more could we run our own affairs. We were required to fit in as people tolerated with great restraint in a western type society. We were tolerated simply because our cheap labour is needed. Hence we are judged in terms of standards we are not responsible for. Whenever colonisation sets in with its dominant culture, it devours the native culture and leaves behind a bastardised culture. This is what has happened to the African culture. It is called a sub-culture purely because the African people in the urban complexes are mimicking the white man rather unashamedly.

In rejecting Western values therefore, we are rejecting those things that are not only foreign to us but that seek to destroy the most cherished of our beliefs – that the coner-stone of society is man himself – not just his welfare. Not his material well being but just man himself with all his ramifications. We reject the power-based society of the Westerner that seems to be ever concerned with perfecting their technological know-how while losing out on their spiritual dimension. We believe that in the long run the special contribution to the world by Africa will be in this field of human relationship. The great powers of the world may have done wonders in giving an industrial and military look, but the greatest gift still has to come from Africa – giving the world a more human face.