by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 10, 2016 | Indigenous Autonomy

Featured Image: Like Cheran, Michoacán, and the Zapatista Caracoles of Chiapas, the Ñätho community of Huitzizilapan have exercised their sovereignty and voted to form their own communal assembly. Photo: Más de 131.

By Mas de 131 / Global Voices

Translated by Glenn Bower

Huitzizilapan, whose old name is N’dete, which means “big town”, currently encompasses 12 indigenous Otomí-Ñätho communities living in the area between the two large cities of Mexico City and Toluca.

A year ago, its people organized themselves to defend their forests, a movement that ultimately led them to elect their own representatives free from the influence of any political party on 7 December 2015.

That day, the indigenous people waited for the arrival of the Agrarian Ombudsman, the authority which can give power to assemblies formed on communally owned lands in Mexico.

However, the ombudsman never arrived, citing an accident as the reason.

Meanwhile, members of the National Human Rights Commission, who were invited by the comuneros (a Mexican term for members of an agrarian community) to document the assembly, left without warning.

This did not stop the indigenous community members from exercising their rights in line with convention 169 of the International Labour Organization, the Mexican Constitution and agrarian legislation.

During the assembly, by a show of hands, they unanimously choose the “candidates of the people.”

The Ñätho, however, say that they were forced to confront a new assembly convened by the Agrarian Ombudsman without legal grounds on 18 January 2016.

The Ñätho worried that the local government and the pro-government Institutional Revolutionary Party would impose another parallel authority instead of the authority which the people already had elected.

They therefore decided to make efforts to reinforce their vote.

“We are getting organised and visiting all the comuneros so we can win again,” said Abundio Rivera, one of the local leaders.

In a statement released on 12 January, the comuneros criticised the town’s former authorities, who had links to the Institutional Revolutionary Party, for handing out 2,000 Mexican pesos to each person to persuade them not to support the chosen “candidates of the people.”

“We are working on increasing awareness,” stressed Rivera. And they did, on 18 January 2016 they won again.

Since 2003, the federal government has set up registers of comuneros in agrarian and communal centres around the country.

In Huitzizilapan, there are 904 comuneros who make decisions involving the land. Since then, all kinds of projects have been imposed by the communal authorities, without any prior consultation with the people.

The idea behind the 2014 movement and the formation of a group of candidates from open assemblies held in the town was to reverse the environmental destruction and protect the integrity of the Huitzizilapan people’s lands.

Once elected on 7 December, the first words of the new commissariat were:

We all know the great difficulties facing the community, we must care for our land, our water and our forest as well as deal with other issues. To me it seems we must keep those citizens of San Lorenzo whether they be at home or away, in mind. Let us give them the chance to voice their vote.

Another comunero went even further in saying:

I will fight for the autonomy of the people, not just the chance to vote. I will open the doors to the people and recover the autonomy we had 15 years ago, because our children have the right to decide what happens to their land and forest, independent of the Agrarian Ombudsman.

The president’s order

Along with its neighbours, Xochicuautla and Ayotuxco, Huitzizilapan faces the construction of the Toluca-Naucalpan highway, which was contracted to a corporation owned by Juan Armando Hinojosa, one of the businessmen most favored by Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto’s government.

At the beginning of 2015, the former town commissioner and member of the Institutional Revolutionary Party, Luis Enrique Dorantes, passed a supposed “forest exploitation plan” without notifying the people.

A few months later, on the morning of 5 July, young men and women from Huitzizilapan set themselves up at the community council offices, lighting campfires to watch an assembly in which Dorantes had planned to hand over part of the peoples’ land to the local government of Lerma, though a process called “disincorporation”.

That morning the church bells rang next to the council offices, and hundreds of residents answered the call to expel around a thousand police from their town.

Women, young people and children of Huitzizilapan have met with indigenous people from all over the country, as well as with some of the families of the 43 students from the Ayotzinapa teachers’ college in the state of Guerrero who remain missing.

Their case has led them to file protection orders against an expropriation decree on their land ordered by Peña Nieto in March 2014, as well as to create a community newspaper and paint messages such as: “We are all comuneros” and “Here the people are in charge” on walls around the town.

Precious forest

The forests defended by Xochicuautla and Huitzizilapan are recognised by Mexico’s government as the Tributary Sub-basin Forestry and Water Sanctuary.

The 105,844 hectare area is classified as the Zempoala La Bufa Ecological, Recreational Tourist Park, and is known as the Otomí-Mexica Park.

Peña Nieto and Governor Eruviel Ávila insist on constructing a highway for 39 kilometres through this forest, which would practically divide it in two. Avila declared in December that the project will be completed in 2016.

When elected on 7 December, the new commissariat of the people asked, “Why do we care for the forest?”

He then answered the question saying, “Because it is the lungs of both the Valley of Toluca and the Valley of Mexico. It is a matter of preserving it for future generations, let’s raise awareness.”

This article by Mas de 131 originally appeared on Global Voices on February 7, 2016.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 21, 2016 | Indigenous Autonomy, Lobbying

NEW REPORT DOCUMENTS CHALLENGES OF DEFENDING INDIGENOUS LAND RIGHTS IN THE PARAGUAYAN CHACO

By Fionuala Cregan / Intercontinental Cry

Featured image: Members of the the Ayoreo community of Cuyabia. Photo: Iniciativa Amotocodie

“We don’t care if our struggle involves going to prison or even dying. Our struggle is about justice because the land is ours and our children’s.”

—Alejandro Servín

When Alejandro Servin and five others members of the Enxet Sur indigenous community Kelyenmagategma returned home after two days in the woods hunting and collecting honey, little did they expect to be showered with bullets.

“Three of us were walking ahead when we heard the shots, a bullet just missed me. We ran back into the forest to seek refuge but the employees of the estate managed to catch the youngest member of our group, Francisco, who was 14 years old at the time,” says Servín. “As a result all of us came out. Three hours later a contingent of police arrived, arrested us without a warrant and brought us – in the estate owner’s truck – to the nearest police station.”

Following their arrest, the six indigenous men were transferred to the capital Asuncion where they were held incommunicado for 48 hours without access to a lawyer or contact with their families. They were eventually charged with “theft of cattle” – a crime punishable by up to 10 years in prison under the Paraguayan Constitution. TierraViva – a human rights NGO that provides legal support and advocates for the land rights of indigenous communities in the Chaco region of Paraguay – eventually managed to get the charges dropped due to lack of evidence and the serious legal inconsistencies surrounding the arrest.

It is these as well as an array of other cases documented during more than 20 years of work in the Paraguayan Chaco that lead TierraViva to publish the first ever report on the situation of Human Rights Defenders. The report, released in December of last year, features case studies of illegitimate criminal charges, threats and acts of violence against 19 indigenous leaders and human rights lawyers working on land rights in the Chaco.

Paraguay is divided into strikingly different eastern and western regions by the Rio Paraguay. The southeastern Paranena region can be generally described as consisting of an area of highlands that slopes toward the Rio Paraguay. The Chaco in the nothwestern region is predominantly lowlands, also inclined toward the Rio Paraguay, that are alternately flooded and parched. Image by freeworldmaps.net.

This arid forested region represents just over 60 percent of Paraguayan territory. It is inhabited by indigenous communities who know it as their ancestral land and private landowners who began to purchase estates from the 1940s onwards, denying the existence of those indigenous communities. This was the case for Kelyenmagategma: the company El Algarrobal SA bought land in 2002 that was inhabited by this Enxet Sur community.

In the past decade, land in the more populated eastern part of the country has become scarce leading to an expansion of the agricultural frontier into the Chaco. The rate of deforestation over the past five years has averaged 500 hectares (equivalent to 500 football fields) per day. In response to this alarming trend, indigenous communities have begun to organize and unite to secure legal title to parts of their ancestral lands to protect what remains of the unique Chaco ecosystem.

Despite the fact that the constitution of Paraguay recognizes the rights of Indigenous Peoples to their ancestral lands, according to Rodrigo Villagra Carron of TierraViva:

“What we see is an undeniable pattern of Government support for the interests of private landowners and the repression of those who defend human rights and national and international legislation related to the rights of Indigenous People.”

This was echoed by Cristina Coronel at the launch of the report in Asuncion in December:

“What this report reveals is [a] world where things are upside down… where indigenous communities and lawyers are defending universal human rights, but instead of protecting them, the police, public prosecutors and other representatives of the government protect the cattle ranchers and agro-industrial companies responsible for illegal deforestation and evictions of Indigenous People from their ancestral lands.”

This can clearly be seen in the case of Unine Cutamurajna from the Ayoreo community of Cuyabia who denounced illegal deforestation by Brandenstein Agro-Forest Investment (BAFI). Cuyabia acquired legal title to 25,000 hectares of land in 1996; but since then it is estimated the community has lost at least 6000 hectares due to land grabs by cattle ranchers. On one occasion, in 2015, the community hijacked a bulldozer that had been clearing vast tracts of forest on land belonging to them. Instead of investigating the illegal actions of BAFI, the Government of Paraguay sent a contingent of police to recover the bulldozer.he community has subsequently suffered threats from heavily armed private security guards working for the company.

“The Government sides with the cattle ranchers because they have money. We Indigenous People don’t have money,” says Unine. “But we will keep defending our land, it doesn’t matter if they continue to threaten us. We will not give up one more single piece of our ancestral land.”

Other cases in the report include:

- Government employee Irma Torales who, while working at the Public Registrar’s Office, refused to become involved in a case of embezzlement of funds destined for the purchase of land for indigenous communities. Her actions lead to the arrest and imprisonment of the former Director of the National Indigenous Institute of Paraguay. Despite this, Irma was subsequently demoted to a more junior role with a significant reduction in her salary.

- Human Rights Lawyer and Director of TierraViva Julia Cabello who faced a possible one-year suspension from practicing law or disqualification from the Paraguay Bar Association for a criticism she made of a Supreme Court Decision to review the constitutionality of a law allowing the return of more than 14,404 hectares of traditional land to the Sawhoyamaxa indigenous community.

TierraViva intends to use the report to carry out continued advocacy and raise awareness of the grave situation of human rights defenders in the Chaco.

According to Villagra Carron:

“This report is a condemnation of the structural inequality in Paraguay and a call to action. The cases documented in it are by no means exhaustive but just a few examples of what is happening in a broader context of rights deprivation. We urgently need to bring this situation and the government’s complicity and/or role in perpetuating it to public attention or the situation risks becoming even more dangerous, serious and unjust.”

The report received support from the Gran Chaco Ecumenical Small Projects Fund which works to strengthen the capacity of civil society organizations, groups and communities in the South American Chaco to transform the conditions of poverty and inequality and promote human rights.

To see the full report in Spanish click here.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 18, 2016 | Indigenous Autonomy, Lobbying

By Glenn Scherer, Mongabay

Featured image: Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff visits the construction site of the Belo Monte Dam, 2014. Photo by Ichiro Guerra/Sala de Imprensa licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic license

The gigantic Belo Monte hydroelectric dam, located on the Xingu River in the heart of the Brazilian Amazon, stood just weeks away from beginning operation this week — but the controversial mega-dam, the third largest on earth, has now been blocked from generating electricity by the Brazilian court system until its builders and the government meet previous commitments made to the region’s indigenous people.

Federal court judge Maria Carolina Valente do Carmo in the city of Altamira, in the state of Pará where the dam is located, has suspended the dam’s operating license. It will not be reinstated, she decided, until the dam’s owner Norte Energia SA, along with Brazil’s government, meet a 2014 court-ordered licensing requirement to reorganize the regional office of Funai, the national agency that protects Brazil’s indigenous groups.

Judge Valente do Carmo has fined the government and company R$900,000 (US$225,000) for non-compliance with the Funai requirement, a provision included in the rules governing Belo Monte when the project was given its preliminary license in 2010.

This is the latest in a series of snafus that have plagued the dam’s construction. Licensing of the project was delayed last September by Brazil’s environmental agency IBAMA, due to a failure to complete agreed to provisions to mitigate the impacts of inundating thousands of acres of Amazon rain forest — flooding that could displace 20,000 people.

Indigenous village near the Xingu River in the Amazon. Indigenous lands could soon be flooded by the Belo Monte dam. Photo by Pedro Biondi/ABr licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Brazil license.

Earlier in 2015, federal prosecutors found that Norte Energia violated 55 different obligations it had agreed to in order to guarantee the survival of indigenous groups, farmers and fishermen whose homes and lands will be lost.In December, Brazil’s Public Federal Ministry, an independent state body started legal proceedings to have it recognized that the crime of “ethnocide” was committed against seven indigenous groups during the building of the Belo Monte dam.

Indigenous groups have fought the dam since its inception, saying that it will severely impair their water supply and impact fishing and hunting. They especially contend that it will reduce the river’s flow by 80 percent at the Volta Grande (“Big Bend”), where indigenous Juruna and Arara people and sixteen other ethnic groups live, according to the teleSUR television network.

Partially republished with permission of Mongabay. Read the full article at Brazilian court suspends operating license for Belo Monte dam

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 12, 2016 | Colonialism & Conquest, Indigenous Autonomy

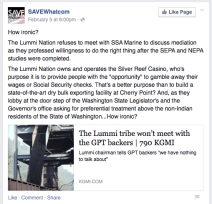

Featured image: September 21, 2012: Members of the Lummi Nation protest the proposed coal export terminal at Cherry Point by burning a large check stamped “Non-Negotiable.” The tribe says they want to protect the natural and cultural heritage of the site. Photo by Indian Country Today Media Network.

By Sandy Robson / Coal Stop

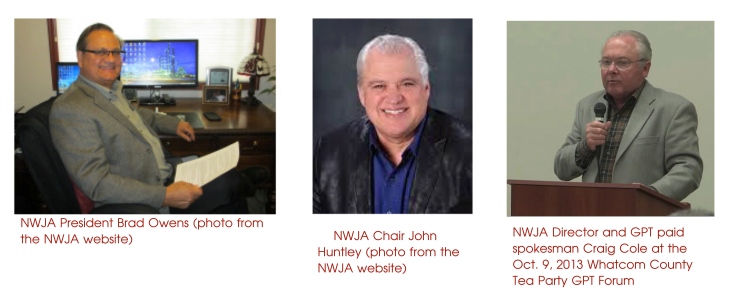

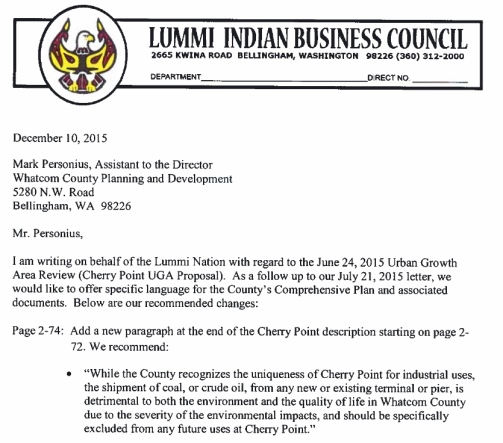

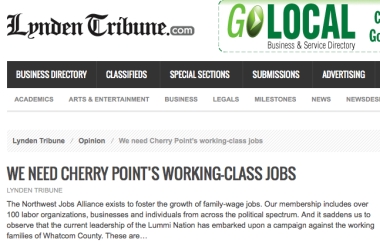

The Lynden Tribune newspaper made the decision to publish a December 23, 2015 opinion piece submitted by Chair John Huntley and President Brad Owens of the Northwest Jobs Alliance (NWJA). The NWJA advocates for the proposed Gateway Pacific Terminal (GPT) project. Their op-ed leveled unsubstantiated, defamatory allegations at unnamed “leadership” of the Lummi Nation, a self-governing Indian Nation, and those allegations could easily be perceived as having been leveled at Lummi Nation as a whole.

Canoe and murals in the Lummi Administrative Building

The Lummi, a Coast Salish people, are the original inhabitants of Washington state’s northernmost coast and southern British Columbia. The Lummi Reservation is located in western Whatcom County, and it is governed by the Lummi Indian Business Council (LIBC), an eleven member tribal council.

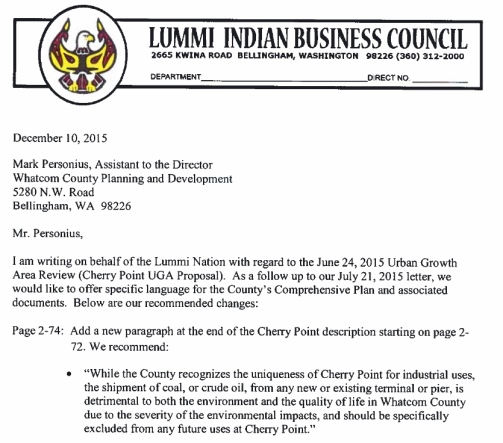

NWJA’s December 23, 2015 Lynden Tribune op-ed claimed that “the current leadership of the Lummi Nation has embarked upon a campaign against the working families of Whatcom County.” In an attempt to support that inflammatory claim, NWJA pointed to a December 10, 2015 letter from Kirk Vinish of the Lummi Nation’s Planning Department. However, a review of that 2-page letter produced no evidence to support such a claim.

NWJA’s December 23, 2015 Lynden Tribune op-ed claimed that “the current leadership of the Lummi Nation has embarked upon a campaign against the working families of Whatcom County.” In an attempt to support that inflammatory claim, NWJA pointed to a December 10, 2015 letter from Kirk Vinish of the Lummi Nation’s Planning Department. However, a review of that 2-page letter produced no evidence to support such a claim.

In contrast, NWJA has left a trail of evidence demonstrating its continued pattern of negative messaging to raise resentment about, and discredit, the Lummi Nation’s opposition to GPT by sending accusatory letters to the Army Corps and Whatcom County, and by disseminating similar accusatory messaging to the public, via the NWJA email list and a press release sent to local media.

In NWJA’s opinion piece, Huntley and Owens also alleged that Lummi Nation leaders are proposing the elimination of existing Cherry Point industry jobs. They provided no evidence whatsoever to support such a claim.

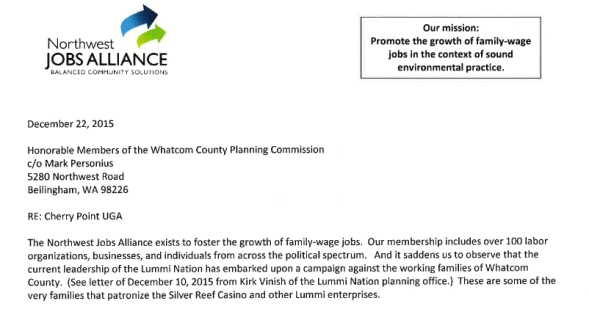

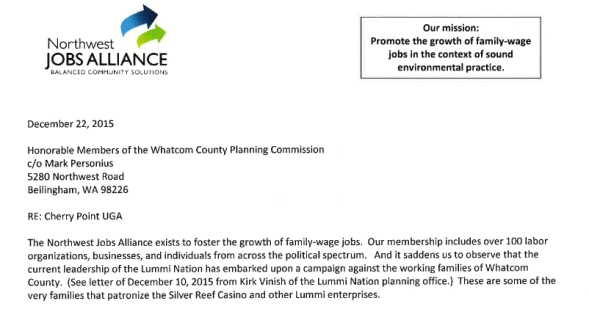

Excerpt from NWJA’s December 22 comment letter to the Whatcom County Planning Commission

As if it weren’t bad enough that NWJA submitted its defamatory op-ed for publication in a local newspaper, the Alliance launched a second strike aimed at Lummi Nation leadership the day before, by submitting a December 22 comment letter to the Whatcom County Planning Commission, on the currently ongoing Whatcom County Comprehensive Plan Update.

The comment letter was a slightly revised version of NWJA’s op-ed published in the Lynden Tribune, containing the same unsubstantiated accusations. NWJA’s inflammatory comment letter is now part of the official public comment record for the County Comprehensive Plan Update which the Whatcom County Council will review prior to voting on the final language to be included in the plan update. The fact that the Council is also one of the decision makers on permits needed by PIT for its GPT project makes NWJA’s comment letter “comprehensively” reprehensible.

GPT threatens Lummi treaty rights

GPT would be sited along the Salish Sea shoreline, at Xwe’chi’eXen, part of the Lummi Nation’s traditional fishing area. Xwe’chi’eXen is the Lummi peoples’ ancestral name for Cherry Point, an area which has a deep cultural, historic and spiritual significance to the Lummi people, as it was a village site for their ancestors for over 175 generations.

The projected coal export terminal threatens Lummi treaty rights, the salmon they depend on, their Schelangen (“Way of Life”), and the cultural integrity of Xwe’chi’eXen. LIBC Chairman Tim Ballew II sent a January 5, 2015 letter to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Seattle District Commander, Colonel John G. Buck, asking the agency to take immediate action to deny the GPT permit application.

In that letter, Chairman Ballew stated that the GPT project “will directly result in a substantial impairment of the treaty rights of the Lummi Nation throughout the Nation’s ‘usual and accustomed’ fishing areas.” Ballew also wrote that “The Lummi Nation is opposed to this project due to the cultural and spiritual significance of Xwe’chi’eXen, and intends to use all means necessary to protect it.” He added that the Lummi Nation has a sacred obligation to protect Xwe’chi’eXen based on that significance.

Page excerpt from “Protecting Treaty Rights, Sacred Places, and Lifeways: Coal vs. Communites,” presented by Jewell James, Lummi Tribal Member and Head Carver, Lummi Tribe’s House of Tears Carvers

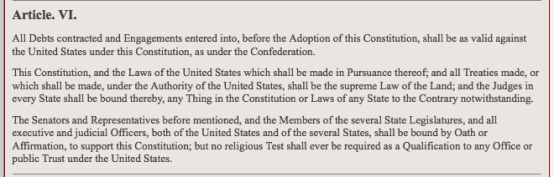

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (“the Corps”) is the federal agency tasked with coordinating and handling the environmental review for the GPT project, and it is legally obligated to ensure that the Lummi Nation’s treaty rights are protected, and are not violated. Currently, the Corps is in the process of making a determination as to whether impacts to any tribes’ U&A (usual and accustomed) treaty fishing rights are more than de minimis, meaning too small or trivial to warrant legal review.

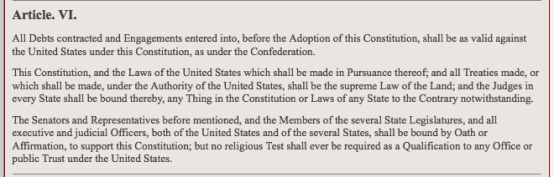

Article VI of the U.S. Constitution which includes the clause that establishes treaties made under its authority, are the supreme law of the land

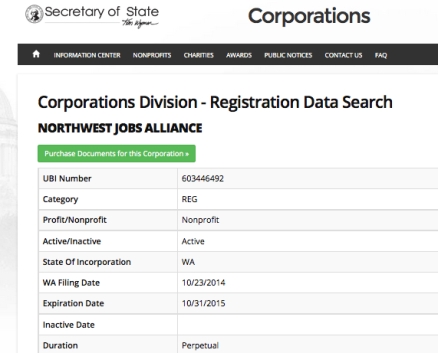

SSA Marine consultant Craig Cole, Director for NWJA

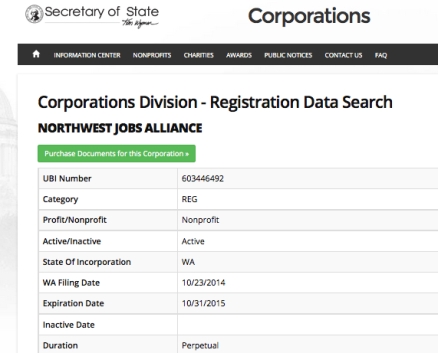

The Northwest Jobs Alliance (NWJA) was created to promote and advocate for the GPT project. For the first few years, NWJA consisted solely of a Facebook page, after that page had been created in May of 2011. NWJA’s original mission statement that had been displayed for years on its Facebook page read: “The Alliance focuses their efforts on supporting the Gateway Pacific Terminal. . .” For almost three years, NWJA’s Facebook page showed “www.gatewaypacificterminal.com” as its website address, and the phone number displayed had been a non-working number.

Several articles appeared in Whatcom County citizen-based publications during the summer and fall of 2014, criticizing the legitimacy of the NWJA and likening it to a front group, as it did not have a working phone number or a website other than the official GPT website. Subsequently, NWJA made some changes. In fall of 2014, the NWJA added a working phone number, created a website for its online presence, and changed its listed website address on its Facebook page from “gatewaypacificterminal.com” to “NWJA.org.”

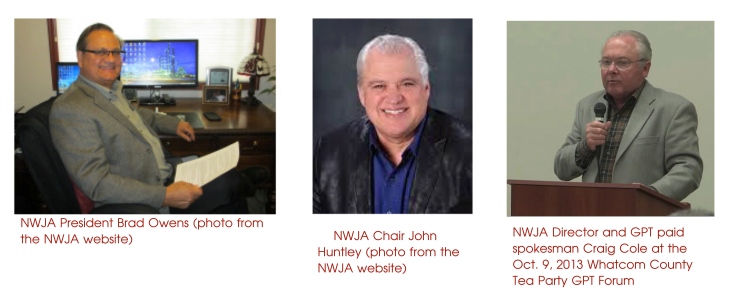

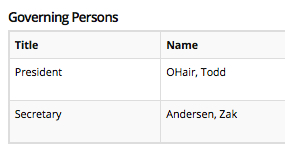

Presently, the NWJA website states the following as its mission: “The Northwest Jobs Alliance (NWJA) promotes the growth of family-wage jobs in the context of sound environmental practice.” Also, there is no mention of GPT on the NWJA website’s Home page where the organization’s mission and focus are explained. Instead the general term “Cherry Point industrial area” is used. On October 23, 2014, NWJA was filed as a non-profit corporation, according to the Washington Secretary of State website. SSA Marine’s paid local consultant for the GPT project, Bellingham resident Craig Cole, is the listed Director for NWJA.

On October 23, 2014, NWJA was filed as a non-profit corporation, according to the Washington Secretary of State website. SSA Marine’s paid local consultant for the GPT project, Bellingham resident Craig Cole, is the listed Director for NWJA.

Since its inception, NWJA has had a steady turnover of co-chairs, all of whom have been very public advocates for the GPT project. Presently, Brad Owens is listed as NWJA President and John Huntley is listed as NWJA Chair. Huntley owns Mills Electric, a Bellingham electrical contracting company. Owens, a Bellingham resident, is the past President of the NW Washington Building & Construction Trades Council.

Since its inception, NWJA has had a steady turnover of co-chairs, all of whom have been very public advocates for the GPT project. Presently, Brad Owens is listed as NWJA President and John Huntley is listed as NWJA Chair. Huntley owns Mills Electric, a Bellingham electrical contracting company. Owens, a Bellingham resident, is the past President of the NW Washington Building & Construction Trades Council.

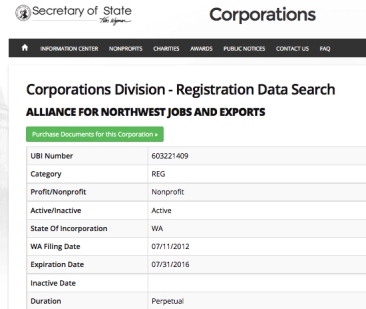

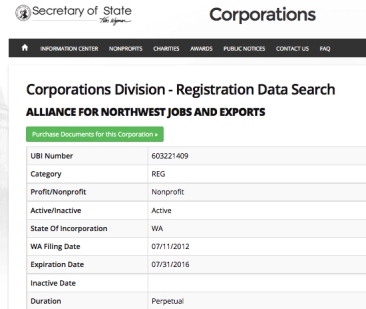

Some people confuse the “Northwest Jobs Alliance” for another similarly titled GPT advocacy organization called the “Alliance for Northwest Jobs and Exports.” It’s worthwhile to distinguish between the two, although promoting the GPT project has been the central intended purpose of both groups.

Cloud Peak Energy and BNSF govern Alliance for NW Jobs & Exports

The Alliance for Northwest Jobs and Exports (ANWJE) was first presented to the public as a grass-roots organization, when it was actually created in 2012, by Edelman, the world’s largest public relations firm, which was hired by SSA Marine to do public relations work for the proposed GPT project.

According to the Washington Secretary of State website, ANWJE was filed as a non-profit corporationin July 2012. The “Governing Persons” listed are Todd O’Hair and Zak Andersen. Todd O’Hair is currently Senior Manager, Government Affairs for Cloud Peak Energy Inc. which has a 49% stake in SSA Marine/PIT’s GPT project. Zak Andersen is presently Assistant Vice President, Community and Public Affairs for BNSF Railway.

According to the Washington Secretary of State website, ANWJE was filed as a non-profit corporationin July 2012. The “Governing Persons” listed are Todd O’Hair and Zak Andersen. Todd O’Hair is currently Senior Manager, Government Affairs for Cloud Peak Energy Inc. which has a 49% stake in SSA Marine/PIT’s GPT project. Zak Andersen is presently Assistant Vice President, Community and Public Affairs for BNSF Railway.  BNSF is the applicant for GPT’s interrelated Custer Spur project and would be the railway transporting coal mined in Montana and Wyoming to GPT. ANWJE’s website describes its group as a “non-profit trade organization that supports new export projects in Oregon and Washington State…”

BNSF is the applicant for GPT’s interrelated Custer Spur project and would be the railway transporting coal mined in Montana and Wyoming to GPT. ANWJE’s website describes its group as a “non-profit trade organization that supports new export projects in Oregon and Washington State…”

BNSF Railway, SSA Marine, and Cloud Peak Energy are listed on the ANWJE’s membership list, which is comprised of companies and other entities which stand to benefit financially from the coal export terminal. So, this “non-profit trade organization” was created by the public relations firm hired by the GPT applicant, and it is governed by an employee of BNSF, the applicant for the interrelated Custer Spur project, and by an employee of Cloud Peak Energy, which has a 49% stake in SSA Marine/PIT’s GPT project.

NWJA’s attempt to drive public opinion against Lummi opposition to GPT

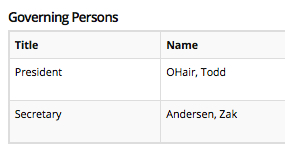

Whatcom Tea Party board member Kris Halterman hosts a local Whatcom County KGMI talk radio show, “Saturday Morning Live” (SML). On her September 12, 2015 SML show, Halterman hosted NWJA President Brad Owens, and together, they advanced an unsubstantiated, defamatory assertion that NWJA (the entity behind the Lynden Tribune op-ed) had previously purported in its August 20, 2015 letter to the Corps—that there is “an apparent motive behind the Lummi Nation’s opposition to the Gateway Pacific Terminal project (and completion of the EIS process)not connected with treaty rights.” [italicized emphasis theirs]

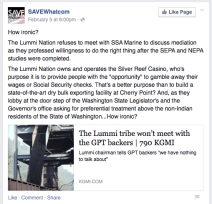

Joining in those activities against Lummi opposition to GPT, was the Political Action Committee SAVEWhatcom, headed up by Halterman, whose name pops up in most everything GPT-related. The SAVEWhatcom PAC was the vehicle for Gateway Pacific coal terminal interests to fund 2013 and 2014 local Whatcom County election political campaigns with over $160,000, which, if successful, would benefit those interests.

February 5, 2015 post from the SAVEWhatcom Facebook page

One month after the LIBC’s January 5, 2015 letter to the Corps, Halterman’s SAVEWhatcom placed a February 5 post on its Facebook page which disparaged the Lummi Nation and its Silver Reef Casino in what appeared to be an attempt to drive public opinion against the Lummi Nation’s strong oppositional stance to GPT.

Then, in an August 12, 2015 comment letter to the Whatcom County Planning Commission, NWJA seemed to pit “working families” who were characterized in the letter as “some of the very people who patronize Lummi enterprises”— against what was described as “tribal aspirations.” Echoing that previous tack of drawing attention to the Lummi Nation’s enterprises while at the same time denigrating the Nation with groundless claims, the NWJA referenced the Lummi Nation’s Silver Reef Casino in their December 23, 2015 Lynden Tribune op-ed. That excerpt read:

“And it saddens us to observe that the current leadership of the Lummi Nation has embarked upon a campaign against the working families of Whatcom County. These are some of the very families that patronize the Silver Reef Casino and other Lummi enterprises. Some thanks.”

Those specific repeated references to the Lummi Nation’s Silver Reef Casino and enterprises by SAVEWhatcom and the SSA Marine consultant-led NWJA, could be viewed as attempts to drive public opinion against the Lummi Nation’s Silver Reef enterprises—trying to change the minds of the Silver Reef’s loyal patrons who enjoy the hotel, spa, casino, entertainment/shows, multiple restaurants, convention and event venue, and more.

NWJA omits important statistics

NWJA’s December 23 opinion piece failed to mention that the Lummi Nation’s Silver Reef Hotel Casino & Spa employs 675 people. It also failed to mention any of the significant contributions from the Lummi Nation to Whatcom County’s community at large, which certainly have a positive impact on countless families and individuals in Whatcom County. For example, LIBC Chairman Tim Ballew stated in a May 2015 piece in The Bellingham Herald, that Lummi Nation was “humbled and honored to be able to give back to the people who work so hard to make our community thrive,” when referring to its Nation’s donations of over $600,000 awarded to 43 organizations. Some of those organizations include the Bellingham Food Bank, the Whatcom Literacy Council, and Whatcom County Fire District 8, to name a few.

NWJA stated in its December 23 op-ed and its December 22 comment letter to the County Planning Commission, that “Whatcom County ranks 30th out of 39 counties for personal income growth [Bellingham Herald 11/19/15].” In reading The Bellingham Herald article cited as a source for that statistic, NWJA did not bother to inform readers that while the per capita personal income average in Whatcom County increased 3.2% from 2013 to 2014, placing it 30th out of 39 counties in the state, Whatcom County’s 2014 per capita income total ranks 16th highest out of Washington’s 39 counties.

Excerpt from December 10, 2015 comment letter submitted to Whatcom County Planning and Development by the Lummi Nation Planning Department

In its December 23 op-ed, and in its December 22 comment letter NWJA sent to the Planning Commission, Huntley and Owens referenced specific language from the December 10, 2015 comment letter from Lummi Nation’s Planning Department submitted to Whatcom County Planning and Development. The specific language was a new policy that Lummi Nation recommended be added to the County Comprehensive Plan:

“The shipment of coal, or crude oil, from any new shipping terminal or pier, or any existing terminal or pier, is prohibited.” Huntley and Owens said they were troubled by the Lummi Nation’s recommendation and wrote:

“This echoes previous requests that the Lummi have made to the County to begin phasing out the Cherry Point heavy industrial zone.” No evidence, however, was provided by the NWJA to show any previous, or even current, requests from Lummi Nation to begin phasing out the Cherry Point heavy industrial zone.

The underbelly of their reasoning

One particular statement NWJA made in its August 12, 2015 comment letter to the County Planning Commission revealed the underbelly of their reasoning:

“The Lummi occupy an important and unique role in our community, but they are just 1.5% of the County’s population.”

NWJA repeated similar statements in its August 27, 2015 email advertisement disseminated via its mailing list, and in its September 10, 2015 press release, potentially indicating to their audiences a reason to marginalize and dismiss Lummi Nation’s voice based on the Lummi’s minority population status.

Just as “Manifest Destiny” mandated that it was supposedly God’s providence that the U.S. should exercise hegemony over its neighbors—seeing North America as the new Promised Land, NWJA and the GPT corporate interests they advocate for, seem to believe that it’s their economic providence to exercise hegemony over the Lummi Nation—seeing Xwe’chi’eXen (Cherry Point) and its naturally occurring deep-water contours which allow for huge Capesize vessels stuffed with U.S. coal bound for Asia, as their new Promised Land.

The Lummi Nation, however, and countless people in the Pacific Northwest region, have a very different view of their destiny, and that view does not include the transporting, handling, and shipping of 48 million metric tons per year of coal to Asia, which is the plan for GPT.

Raising resentment of tribal treaty rights; encouraging the public and government officials to ignore tribal treaty rights; calling into question the motivation behind an Indian Nation’s exercising of its tribal treaty rights; interfering with the federal regulatory review process and the government to government relationship between a U.S. federal agency and Indian Tribes and Indian Nations; and making disparaging and unsubstantiated accusations against an Indian Nation and its leaders, are some of the various ways in which the Lummi Nation is being attacked as powerful corporations endeavor to realize their perceived manifest destinies, in pursuit of a coal export terminal at Xwe’chi’eXen.

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Dec 29, 2015 | Indigenous Autonomy

By Dan Bacher / Intercontinental Cry

Featured image: Salmon Barbecue at the 53rd Klamath Salmon Festival (photo: Yurok Tribe/Facebook)

The Yurok Tribe, the largest Indian Tribe in California with over 6,000 members, has banned genetically engineered salmon and all Genetically Engineered Organisms (GEOs) on their reservation on the Klamath River in the state’s northwest region. The Yurok ban comes in the wake of the federal Food and Drug Administration (FDA) decision on November 19 to approve genetically engineered salmon, dubbed “Frankenfish,” as being fit for human consumption, in spite of massive public opposition to the decision by fishermen, Tribes, environmental organizations and public interest organizations.

On December 10, 2015, the Yurok Tribal Council unanimously voted to enact the Yurok Tribe Genetically Engineered Organism (“GEO”) Ordinance. The vote took place after several months of committee drafting and opportunity for public comment, according to a news release from the Tribe and Northern California Tribal Court Coalition (NCTCC). This ordinance is apparently the first of its kind in the U.S. to address the FDA’s approval of AquaBounty Technologies’ application for AquAdvantage Salmon, an Atlantic salmon that reaches market size more quickly than non-GE farm-raised Atlantic salmon, as well as all GMOs.

“The Tribal GEO Ordinance prohibits the propagation, raising, growing, spawning, incubating, or releasing genetically engineered organisms (such as growing GMO crops or releasing genetically engineered salmon) within the Tribe’s territory and declares the Yurok Reservation to be a GMO-free zone. While other Tribes, such as the Dine’ (Navajo) Nation, have declared GMO-free zones by resolution, this ordinance appears to be the first of its kind in the nation,” the Tribe said.

“On April 11, 2013, the Yurok Tribe enacted a resolution opposing genetically engineered salmon, and then secured a grant from the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) to support the Tribe’s work in continuing to protect its ancestral lands, including: waters, traditional learning and teaching systems, seeds, animal-based foods, medicinal plants, salmon, sacred places, and the health and well-being of the Tribe’s families and villages. GMO farms, whether they are cultivating fish or for fresh produce, have a huge, negative impact on watersheds the world over,” the Tribe stated.

“The Yurok People have managed and relied upon the abundance of salmon on the Klamath River since time immemorial. The Tribe has a vital interest in the viability and survival of the wild, native Klamath River salmon species and all other traditional food resources,” the release said.

James Dunlap, Chairman of the Yurok Tribe, said, “The Yurok People have the responsibility to care for our natural world, including the plants and animals we use for our foods and medicines. This Ordinance is a necessary step to protect our food sovereignty and to ensure the spiritual, cultural and physical health of the Yurok People. GMO food production systems, which are inherently dependent on the overuse of herbicides, pesticides and antibiotics, are not our best interest.”

The Ordinance allows for enforcement of violations through the Yurok Tribal Court. Yurok Chief Judge Abby Abinanti stated, “It is the inherent sovereign right of the Yurok People to grow plants from natural traditional seeds and to sustainably harvest plants, salmon and other fish, animals, and other life-giving foods and medicines, in order to sustain our families and communities as we have successfully done since time immemorial; our Court will enforce any violations of these inherent, and now codified, rights.”

The Yurok Tribe is working with other Tribes in a regional collaborative as part of the Northern California Tribal Court Coalition (NCTCC), and the Tribe and NCTCC are co-hosting an Indigenous Food Sovereignty Summit in Klamath in the spring of 2016. A signed copy of the ordinance can be found on NCTCC’s website.

The Tribal Council passed the ordinance at a critical time for West Coast salmon and steelhead. The Klamath River, located on the Tribe’s homeland, is plagued by massive algal blooms, exacerbated by agricultural runoff and antiquated hydroelectric dams, that turn the river toxic each summer. The Tribe is working with other Tribes, environmentalists, fishing groups and elected officials to remove four dams on the Klamath River to restore the river’s salmon, steelhead and other fish populations. The Tribe in September withdrew from the controversial Klamath Agreements and in December announced it “strongly opposes” draft legislation from US Representative Greg Walden of Oregon to address Klamath River Basin water issues.

The Klamath’s salmon and other fish populations are also threatened by Jerry Brown’s California Water Fix to build the Delta Tunnels. The massive tunnels proposed for construction under the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta, the largest estuary on the West Coast of the Americas, would export water to corporate agribusiness interests, Southern California water agencies and oil companies conducting fracking and other extreme oil extraction methods in Kern County.

A large proportion of the water of the Trinity River, the Klamath’s largest tributary, is diverted from Trinity Reservoir to the Sacramento River basin via Whiskeytown Reservoir to irrigate almonds, pistachios and other crops on drainage impaired land in the Westlands Water District on the west side of the San Joaquin Valley. The giant tunnels would imperil Chinook salmon, coho salmon, steelhead and lamprey populations on the Trinity and Klamath rivers, as well as hastening the extinction of Sacramento River winter-run Chinook salmon, Central Valley steelhead, Delta and longfin smelt, Sacramento splittail and green sturgeon populations.

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Dec 27, 2015 | Colonialism & Conquest, Indigenous Autonomy

By Mary Cappelli

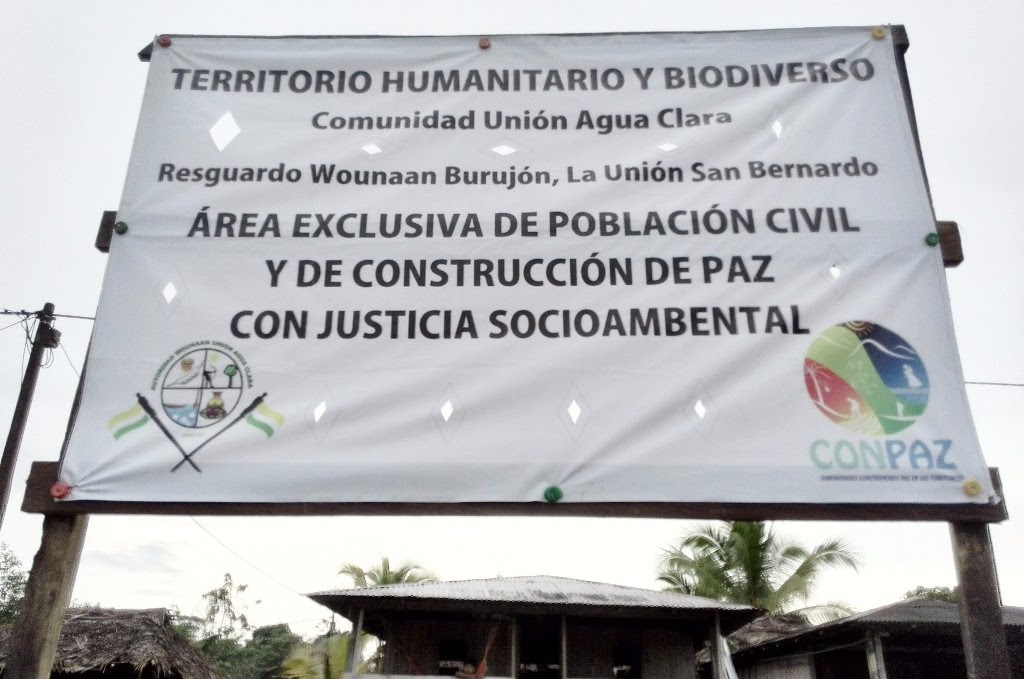

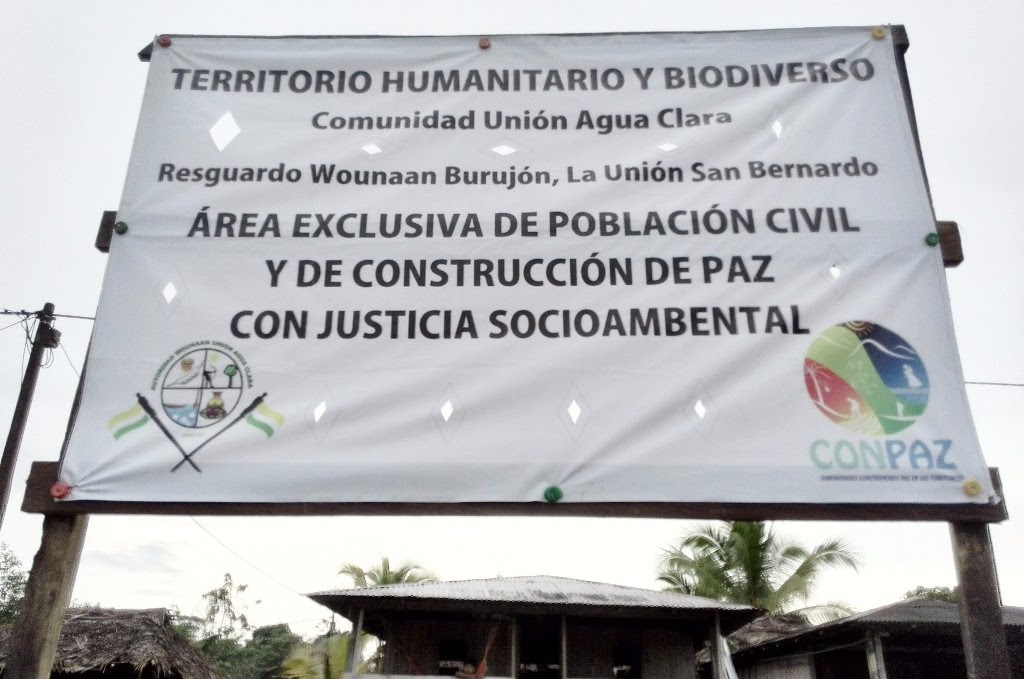

Featured image: Wounaan Banner, reading:

Humanitarian and biodiverse territory

Community of Union Aguas Claras

Reservation of Wounaan Burujon, La Union San Bernardo

An exclusive area of civilians and peacebuilding and justice

The Wounaan Tribe of Northwestern Colombia’s San Juan River is the latest casualty of a violent 25 year reign of terror hastened by the convergence of coca growers, gold miners, paramilitaries, guerillas, and government troops—all vying for control of the waterways and resources along the ancestral stretch of traditional Wounaan territories. Until the arrival of mono-crop production for export, Wounaan’s steadfast strategies have thwarted the bloodied battlefields of Spanish colonial impositions, nationalist armies, and Marxist guerrillas.

Occupying small thatched huts stilted on posts hovering up to eight feet high along the clearings on the riverbanks, the Wounaan kept to their subsistence livelihoods of hunting, fishing, Werregue Palm basket-weaving, and small-scale agriculture of bananas, pineapples, and yucca. That is until November 2014 when the Wounaan Tribe was forced to leave their village of Unión Aguas Claras along the San Juan river of the Cauca Valley and take up a 12-month residence in El Cristal Sports Arena in Buenaventura, Colombia.

According to Wounaan spokesman Crelo Obispo, “Paramilitaries kicked us out of land” and for twelve months they worked diligently to “find a peaceful way to recover our own indigenous land.” The Wounaan turned their occupation into a form of civil disobedience and refused to return to their lands without adequate protection and security from warring factions. Although on November 29, 2015, they returned home along the San Juan River, their cultural survival signals a critical humanitarian and environmental emergency in which indigenous people living sustainable lives have been caught in a resource war for coca cultivation, gold mining and control of key river tributaries.

Occupy El Cristal

For a full year, 343 Wounaan people, 63 families, occupied the cold hard floor of the basketball courts sleeping in multi-colored hand-woven hammocks strung beneath the stadium bleachers. One of them was a young wearied mother holding a shirtless 11 month-old infant suffering from a burning fever and bouts of diarrhea and vomiting. She recalled: “There wasn’t any medicine.” Herein lies the crisis. Not only were mothers unable to gain access to traditional herbal medicines, they were also unable to gain access to modern health care. Three somber mothers told me they were running out of adequate food and water sources. Buenaventura Officials confirmed the death of two young children, one year-old Neiber Cárdenas Pirza in December 2014 and a two day-old baby in June 2014. The Wounaan claimed the deaths were a result of inadequate health care and living conditions in the sports arena. “Our people practice culture, artistry, spirituality and traditional medicine. We need our lands to do so,” said Obispo.

The affirmative belief that the Wounaan were “occupying” the sports arena and taking a political stand against their dispossession by violence is key to understanding Wounaan resistance. “We arrived November 28, 2014 and since that time we had been in resistance,” Chama Puto said. Because the “the local government hardly did anything, and gave no guarantees of assistance,” he urgently called on international help and social advocacy networks to “get meetings with entities who could make change” and affirmed Wounaan ancestral ties to their lands. “Land doesn’t belong to the government or police. It belongs to the indigenous,” he added.

The occupation of El Cristal is an example of how Indigenous peoples enact visibly distinctive resistance tactics to draw political and social mobilization to defend their right to living in their native territories. Although Wounaan Leaders such as Chama Puto are well versed in Colombia’s constitutional law, they are fully aware of how constitutional decrees have remained rhetorical discourses because of the government’s failure to implement constitutional protections within its infrastructure—an absence of institutional support that has undermined the visionary purpose of the protections. In particular, Article 63 states: “Communal lands of ethnic groups and reservation lands cannot be taken away or attached”; Article 72 states: “Ethnic groups settled in areas of archeological treasures have special rights over that cultural heritage, which rights must be regulated by law”; Article 246 provides that “the authorities of the indigenous peoples may exercise jurisdictional functions within their territories, in accordance with their own standards and procedures, provided they do not conflict with the Constitution and laws of the Republic.”

While in some cases, legal maneuvering and mobilization within Colombian Courts have served to defend indigenous landholdings, the year-long Wounaan occupation of El Cristal is a blatant recognition of the ineffectiveness of Colombia’s legislation and juridical processes. Innovative forms of resistance appeal to wider socio-political networks capable of eliciting support across local, regional, national and global borders; however, it comes with a price.

Rhizomic World

El Cristal Sports Arena was a far cry from the Wounaan’s rhizomic world of heterogeneity and its interconnected relations of all plant, animal, ancestral and human life living within its ecosystems. This dynamic cartography of interconnected networks mapped across their ancestral rhizomic river systems and landscape moves beyond western metaphysical notions of duality to foster a cosmos of inter-being. Wounaan livelihood and well-being rely on their interaction with their landscape, an animistic ethno-geographic interaction grounded in rhizomic thought in which “any point of a rhizome can be connected to anything other, and must be” (Delueze and Guattari 1988).

These beliefs further their kinship networks across time and space in a continuous state of growth in which identities and relationships extend and merge through a web of intersecting relationships. Bill Ashcroft explains the rhizome in biological imagery as multiplying “root system which spreads across the ground” from varying points reaching out across the nomadic space “rather than a single tap root” (1999).

For the Wounaan, the San Juan River is an essential organizing principle of their rhizomic networking system, rich in its biodiversity in which their cosmology interconnects them to 8000-9000 vascular plants, 577 bird species, 52 snake species, 45 lizard and allied species and 127 amphibian species—all inter-being in an ecosystem without hierarchies. In addition to its cohesive social networks, the San Juan River is the true river (döchaar) and ancestral homeland and thus a material feature in the development of their worldview and their perceptions of themselves (Velásquez Runk 2005).

The fluvial systems crisscross over a three-dimensional topography, which includes portals underworld, the real world and the celestial world. In this way their river-dominated cosmos reflects the comings and goings on the river up (marag), down (badag), to (jerag), and from (durrag) in a world where spirits, beings, plants and animals in the visible and invisible world live in a balance of reciprocal equilibrium (Velásquez Runk 2005).

Because of their metaphysical approach which links native individualities, political strategies, and traditional subsistence practices they have been able to maintain their traditional livelihoods and ways of being against the onslaught of land dispossession and acculturation (Velasco 2011). Although their rhizomic community is resistant to rupture where it has fissured and peoples are deterritorialized, the river’s organic networking systems have been capable of reattaching the Wounaan to people, plants, animals within its extended network or creating new connections across its geographical space (Kamash 2008).

Since the 1990s, the San Juan River’s fluvial systems have become reconfigured spaces in which flows of capital, commodities and contraband have brought in a host of nonlocal actors vying for spatial control of its strategic geographies. These vital commercial river networks, which connect the Colombian interior with the Pacific Coast are needed for the production and transportation of gold mining excavation and cocoa cultivation turning the once-peaceful rhizomic ecosystem into a bloody battleground between narco traffickers, gold minders, the FARC, the ELN, the Urabeños, the Rastrojos, and other left wing, right wing, and neo-paramilitary forces.

The result is not only the displacement of indigenous peoples and the disruption of the natural equilibrium of the Wounaan subsistent lifestyle, but the destruction of the biodiverse habitat in which its diverse resources have been transformed to commercial assets and mobilized for monocrop and gold production of surplus value. Added to the actors competing for resources is the introduction of new players from the National Development Plan hoping to position the San Juan River as a key geographic territory for the neoliberal exploitation of resources for free trade agreements. Dispossession for capitalist production has more importantly led to the desecration of ancestral homelands in which families are increasingly intimidated, disappeared and butchered by a collusion of local and nonlocal actors to expedite commodity commerce.

“The government said we are something in the way of development,” said Crelo Obispo further noting, “We’ve been attacked by our conqueror.” Another Wounaan spokesman added, “They want to exterminate us.” Whether it is death by paramilitary, death by narco trafficker, or death in the crossfire between guerillas and the army, there is one certainty as Crelo Obispo declares: There return to their homeland is precarious and must be “met with protection and dignity.”

Amidst these conditions are ongoing negotiations for a bilateral ceasefire between the Government and FARC. Although the Colombian government and FARC rebels have moved towards a comprehensive plan to end an ongoing civil war which, since 1964 has killed 220,000 people, the Wounaan have still been left out in the cold (Rodzinsky). Chama Puto points out that while they are negotiating in Havana, Cuba, “we had been ignored in all negotiation processes.” He believes that conflict resolution can result only when “the government negotiates with all its people.”

As of today, this has not happened and the people the color of the soil who turned their displacement into a political strategy of indigenous resistance to the destruction of their traditional ecosystems still struggle for survival. Chama Puto wants a governmental guarantee of protection and safety in order to survive on their ancestral lands. “We are done negotiating,” he said.

Forceful dispossession underpins the plight of the Wounaan whose homeland has been drained by capital’s international reach for resources in which a “free market exchange relies on and takes advantage of the political and cultural dispossession of certain subjects” (Hennessey 2013). How do indigenous people who make up two percent of Colombia’s population coexist in a global world that renders them disposable, inhuman beings? In this scenario, the two percent making up the indigenous groups of Colombia become eight percent of the dispossessed, displaced, and destined to misery as a form of “human waste”; sadly, a myth narrated and played out in the many parts of the globe.

In El Cristal, the Wounaan were separated from their means of subsistence and vigorously resisted all paradigms of commercial expansion and regional control of their economies—a pattern in which, “more than 5.7 million people have been internally displaced in Colombia since the start of recording official cumulative registration figure” (UNHRC 2015). As of 2014, Colombia’s National Victims’ Unit documented 97,453 cases of forced displacement, mostly along the Pacific region. The El Cristal crisis exposed the systematic layers of political collusion that render Wounaan territories disposable sites of exploitation and economic casualties, which dispossess its peoples from their traditional livelihoods for the benefit of both regional, national, and global markets.

Wounaan Resistance Strategies

Wounaan resistance strategies date back to colonization and manifested in their traditional tactics they implemented to maintain their sense of cultural dignity during their resistance campaign. While living in the Sports Arena women practiced small-scale artesanías in the form of colorful bracelets, necklaces, earrings, and small-carved wooden bowls. The unbroken practice of these customs created communal solidarity and furthered their economic livelihoods, traditional knowledge, and cultural sustainability (Velasco 2012). Although these courageous women were proud to sell their artisans to sports arena visitors, the transactions were soured by the reality of their dispossession. “Collectively and physically the living conditions” were “inadequate, the food inadequate.”

Wounaan resilience to reattach itself to its rhizomic rivers network is precarious and subject to intra-institutional support of regional and national control. It is yet to be seen if this latest mobilization strategy will provide any safeguards and protections for their community. “Promises have been unfulfilled and we have become strangers to ourselves,” sighed a wearied Obispo.

For more information, see CONPAZ.

References

Ashcroft, Bill (1999). “The Rhizome of Post-colonial Discourse” in Roger Luckhurst and Peter Marks (eds.) Literature and the Contemporary: Fictions and Theories of the Present, London: Longman pp. 111-125.

Deleuze, Giles, and Felix Guattarri (2007). A Thousand Plateus: Capitalism and Schizophreina. Brian Massumi, trans. Minneapolis; University of Minnesota Press.

Colombia, Información sobre Derechos Humanos y Libertades Fundamentales de la Poblaciones Indígenas presentada por el Gobierno. (Published in UN.E/CN.4/ Sub.2/AC.4/1991/4).

Hennessy, Rosemary. Fires on the Border. Hennessy, Rosemary. Fires on the Border: The Passionate Politics of Labor Organizing on the Mexican Frontera. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013. Print.

Kamash, Zena (2008). What Lies Beneath? Perceptions of the Ontological Paradox of Water, World Archeology 40 (2) 224-237).

Velasco, Marcela (2011). “Contested Territoriality: Ethnic Challenges to Colombia’s Territorial Regimes.” Bulletin of Latin American Research 30 (2): 213–228.

Brodzinsky, Sibylla. “ Colombia’s government and Farc rebels reach agreement in step to end civil war.” The Guardian. 15 Dec. 2015.

Runk, Julie Valasquez. (2005). And the Creator Began to Carve Us of Cocobolo: Culture, History, Forest Ecology, and Conservation among Wounaan in Eastern Panama. PhD dissertation, Department of Anthropology and the School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, Yale University and the New York Botanical Garden.

__________. (2009). Social and River Networks for the Trees: Wounaan’s Riverine Rhizomic Cosmos and Arboreal Conservation. American Anthopologist 111(4).

2015 UNRCR Country Operations Profile-Colombia. The UN Refugee Agency.