by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 28, 2018 | Culture of Resistance

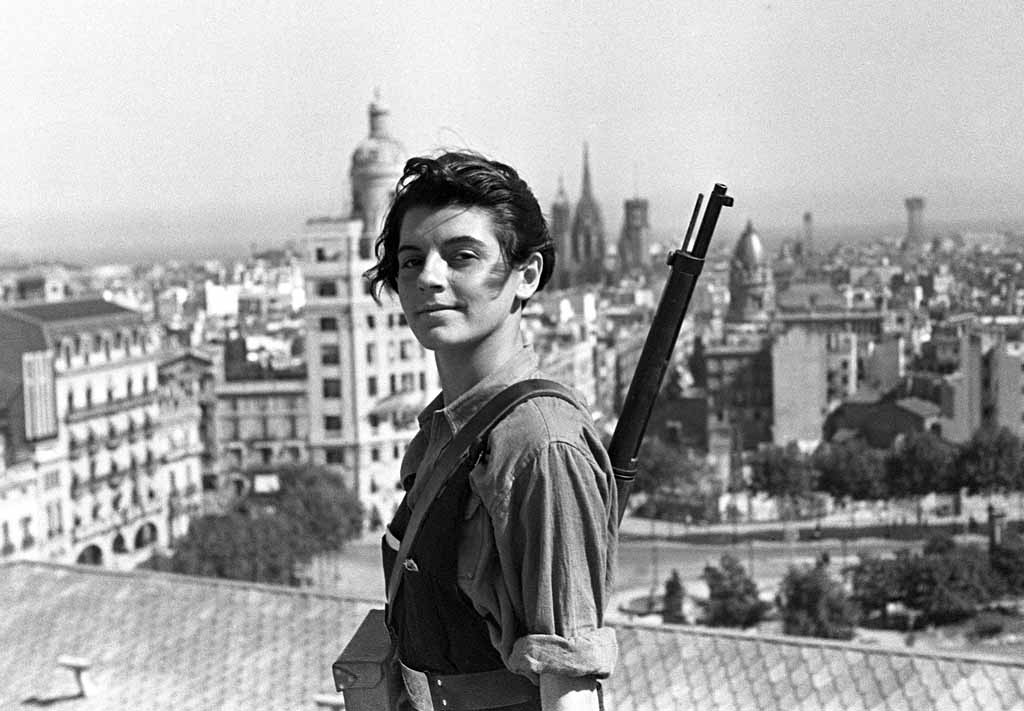

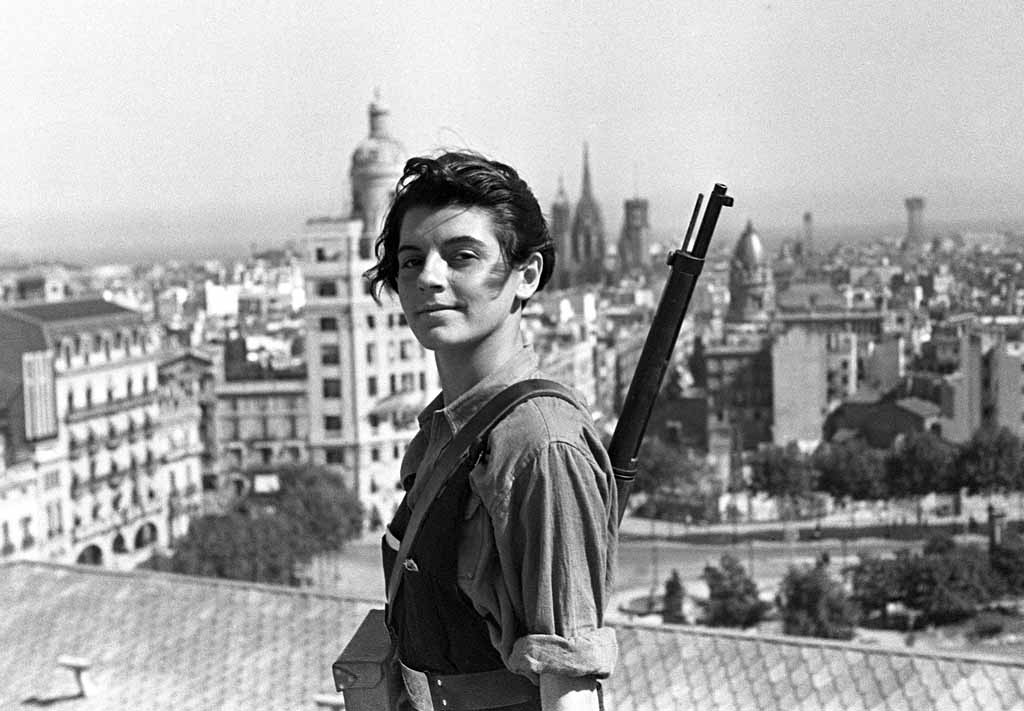

Featured image: Marina Ginestà i Coloma, 17-year old communist militant, on top of the Hotel Colón in anarchist Barcelona during the Spanish Civil War

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Culture of Resistance” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Lierre Keith / Deep Green Resistance

Past movements for social justice insisted on character in their recruits, in honor, loyalty, and integrity. The culture of resistance created by the Spanish Anarchists valued ethical personal behavior. Writes Murray Bookchin, “They were working men and women, obrera consciente, who abjured smoking and drinking, avoided brothels and the bloody bull ring, purged their talk of ‘foul’ language, and by their probity, dignity, respect for knowledge, and militancy, tried to set a moral example for their entire class.”82 We could do worse. The right will continue to successfully blame the left for the destruction of culture and community as long as the left can’t or won’t stand firmly in defense of our values.

This is probably the right time to defend the concept of a work ethic. The alternative culture of the ’60s was in part a reaction against the conformity of the ’50s and its obedience to authority. In 1959, my mother and her friends decided to start an underground newspaper at their school. Their first step? Asking permission from the principal. He said no. They dropped the idea. No wonder the ’60s happened.

The alternative culture was based on the premise that essentially nobody had to do anything they didn’t feel like doing. A major part of their rebellion was the rejection of a work ethic, always cast as Protestant. But taken to its logical end, this is the position of a parasite. The dropouts either got money from their parents, from friends who got it from parents, or from the state. Eventually, each life has to be supported with resources from somewhere. I have seen a few too many protests and alternative communities surviving on the Mooch Ethic. I have sat on couches that housed rats, eaten off dishes that gave me gastroenteritis, and learned (secondhand, thankfully) that an itchy butt at sundown means pinworms. I’ve watched incredible resources go to waste—houses fall to ruin, land repossessed—for refusal to do basic adult tasks like paying the taxes. I don’t know which is worse: the general ethos’s entitlement, or the stupidity; the smell of the outhouses, the unwashed bodies, or the marijuana.

The rebellion against a work ethic is another characteristic of youth culture. The ventral striatal circuit, which is the seat of motivation in the human brain, doesn’t function well during adolescence, which is why teens are often accused of being lazy. This means that the norms of youth culture will gravitate toward structureless days with no expectations or goals. It also means that the youth culture and marijuana aren’t a good match.

The war on drugs is appalling. It has a corrosive effect on communities of color especially and has also made it difficult for those with legitimate need to get pain relief from drugs like marijuana.83 Medical cannabis is a legitimate treatment for a number of conditions, some of which, like autoimmune disorders, are life-threatening. People who need it should be able to get it, and society as a whole would probably be better off if cannabis was legalized.

But drugs and alcohol have been a terrible detriment to both activist cultures and oppressed communities. I have watched people that I love erode with addiction, a slow death I’m powerless to stop. I am very sympathetic to the straight-edge punks. It was obvious to me at age fourteen that there were two weapons I would need for the fight: a mind that could think and the heart of a warrior. Drugs would destroy the one and numb the other. I swore away from drugs and I’ve never regretted that decision.

Drug and alcohol addiction has had terrible effects on both oppressed communities and cultures of resistance. Such effects are broad and deep: the self-absorption, lack of motivation, and broken synapses create a population in semipermanent “couch lock.” Drugs and alcohol will not help us when we need commitment, hard work, and sacrifice, which are the foundation of all cultures of resistance. Addicts have no place on the front lines of resistance because an addict will always put their addiction first. Always.

I came of age in a post-Stonewall lesbian community that recognized the role that alcohol had played in destroying gay and lesbian lives. Our events specifically avoided bars as venues, and were often labeled “chem-free.” These were and are acts of communal self-care that were linked to survival and resistance. It was an important ethic, and it was understood and embraced. There are parallel calls for a chem-free ethic in some Native American activist groups, and for the same reason: drugs and alcohol have been damaging enough to name them genocidal. The radical left would do well to model itself on these recent examples and to consider an ethic of sobriety as both collective self-care and resistance. We need everyone’s brain. If our goal is a serious movement, then we also need focus, dependability, and commitment. On the front lines, we need to know our comrades are rock solid. In our culture, we need a set of ethics and behavioral norms that can build a functioning community. Basic awareness of addiction—its symptoms, its treatment options—is important both to help the afflicted and to keep our groups safe and strong.

A related issue is the general lassitude caused by poor nutrition exacerbated by vegetarian and vegan diets. One investigator of alternative communities writes, “… for many of the rural groups, common activity is limited to part-time farming. In their permissive climate, there is often a debilitating, low-thyroid do-nothingness that looks like nothing so much as the reverse image of the compulsive busyness of their parents.”84

The diet that holds sway across the left will produce that state exactly. A food ethic stripped of protein and fat may meet ideological needs, but it will not meet the biological needs of the human template. Our neurotransmitters—the brain chemicals that make us happy and calm—are made from amino acids; amino acids are protein. Serotonin, for instance, is produced from the amino acid tryptophan. We cannot produce tryptophan; we can only eat it. Likewise endorphins and catecholamines. We must eat protein to have brains that work. We need fat, too, and you’ll notice that in nature, protein and fat come packaged together. In order for your neurotransmitters to actually transmit, dietary fat is crucial. This is why people on low-fat diets are twice as likely to suffer from depression or die from suicide or violent death. If you need more reason to eat real food, your sex hormones are all made from dietary cholesterol: please eat some. A steady diet of carbohydrates, on the other hand, will produce depressed, anxious, irritable people too exhausted to do much beyond attend to the psychodramas created by their blood sugar swings, which about sums up the emotional ambiance of my youth. And the author’s inclusion of “low-thyroid” in his description is right on the mark. Soy is often the only acceptable protein on the menu. Besides its poor quality—plant protein comes wrapped in cellulose, which humans cannot digest—soy is a known goitrogen. In large enough quantities, like when eaten not as a condiment but as a protein source, it can suppress and even destroy the thyroid.

I’ve been to a few too many potlucks with brown rice, dumpster-dived mangoes, and the ubiquitous chips and hummus. I feel my grandmother’s horror from the grave: why are we feeding each other poverty food? This is the only time I feel sorry for men, watching them repeatedly—and I mean four and five times—approach my pot of (pasture-raised) beef-and-leek chili for more. They’re desperate. They may be getting enough bulk calories every day, but they’re starving. Men tend to crave protein because their protein needs are higher—testosterone means men have more muscle than women, and muscle is built from protein. Women tend to crave fat because our bodies are designed to store fat for pregnancy and lactation.85 The current anorexic beauty standards, besides being a very effective tool of patriarchy and capitalism, also point to a profound death wish embedded in this culture. Humans have been celebrating female fat—a veneration both aesthetic and spiritual—since we created art and religion. Our first two art projects reverenced the lives that made ours possible: the large ruminants we ate and the large women who birthed us.

We must stop hating the animals that we are. Only ideological fanatics (I was the most extreme version—vegan—for almost twenty years, so I’m allowed to say that) will be able to stick to such body-punishing fare for any length of time. Everyone else will “cheat” and feel guilty over moral or even spiritual failings without understanding why they failed. The answer is simple: we have paleolithic bodies, we need paleolithic food. If you’re fighting evolution, you are not going to win. There is a reason you feel hungry without fat and protein, a reason for the exhaustion that aches in your muscles and surrounds you like fog, a reason for the gray weight of depression. A plant-based diet is not adequate for long-term maintenance and repair of the human brain or body, and it has been taking a heavy toll on the left for several generations.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 19, 2018 | ANALYSIS, Movement Building & Support

Featured image: Ercan Ayboğa

by Sean Keller / Local Futures

The Mesopotamian Ecology Movement (MEM) has been at the heart of Rojava’s democratic revolution since its inception. The Movement grew out of single-issue campaigns against dam construction, climate change, and deforestation, and in 2015 went from being a small collection of local ecological groups to a full-fledged network of “ecology councils” that are active in every canton of Rojava, and in neighboring Turkey as well. Its mission, as one of its most prominent founding members, Ercan Ayboğa, says, is to “strengthen the ecological character of the Kurdish freedom movement [and] the Kurdish women’s movement.”

It’s not an easy process. Neoliberal policies, war, and climate change have made for an impressive roster of challenges. Crop diversity has been undermined due to longstanding subsidies for monocultures. Stocks of native seeds are declining. The region has been hit by trade embargoes from Turkey, Iraq, and the central Syrian government, and villages have been subject to forced displacement and depopulation. Groundwater reserves are diminishing, and climate change is reducing rainfall. Many wells and farms were destroyed by the self-described Islamic State (ISIS), and many farmers have been killed by mines. Much of the region is without electricity. And there has been an influx of refugees from the rest of Syria, fleeing civil war.

As MEM sees it, the solutions to these overlapping problems must be holistic and systemic. Ercan gives an impressive rundown of MEM’s priorities: Decreasing Rojava’s dependence on imports, returning to traditional water-conserving cultivation techniques, advocating for ecological policy-making at the municipal level, promoting local crops and livestock and traditional construction methods, organizing educational activities, working against destructive and exploitative “investment” and infrastructure projects such as dams and mines — in short, “the mobilization of an ecological resistance” towards anything guilty of “commercializing the waters, commodifying the land, controlling nature and people, and promoting the consumption of fossil fuels.”

In 2016, MEM published a declaration of its social and ecological aims, and it is a thing of beauty. “We must defend,” it says, “the democratic nation against the nation-state; the communal economy against capitalism, with its quick-profit-seeking logic and monopolism and large industries; organic agriculture, ecological villages and cities, ecological industry, and alternative energy and technology against the agricultural and energy policies imposed by capitalist modernity.”

Getting children involved in all of this is critical. Schools in Rojava teach ecology as a fundamental principle. In 2016, with the support of Slow Food International and the Rojava Ministry of Water and Agriculture, MEM helped build a series of school gardens in villages around the city of Kobane, in order to provide a “laboratory” for children to learn about the region’s biodiversity and how to care for it. These gardens are growing fruit trees, figs, and pomegranates, instead of corn and wheat monocultures. Some have been planted on land that was once virtually destroyed by ISIS. In Rojava, even cultivation comes inherently infused with a spirit of resistance. “We grew up on this land and we haven’t abandoned it,” says Mustafa, a teacher whose school was one of those to receive a new garden in 2016. “As a people of farmers and livestock breeders, we have always tended the crops using our own techniques, which are thousands of years old.” As the MEM declaration says, “Bringing ecological consciousness and sensibility to the organized social sphere and to educational institutions is as vital as organizing our own assemblies.”

The spirit of resistance is as alive in the realm of society and economics as it is on the land. The cooperative economy in Rojava is booming. Michel Knapp, a longtime activist in the Kurdish freedom movement and co-author of the book Revolution in Rojava, observes that most cooperatives in Rojava are “small, with some five to ten members producing textiles, agricultural products and groceries, but there are some bigger cooperatives too, like a cooperative near Amûde that guarantees most of the subsistence for over 2,000 households and is even able to sell on the market.”

The government of Rojava is democratic and decentralized, with residential communes and local councils giving people autonomy and control over decisions that affect their lives. Municipal-level government bodies are systematically integrated into the operations of MEM, in a one-of-a-kind partnership between the public and nonprofit spheres. And the prison system is being radically reformed, with local “peace committees” paying attention to the social and political dimensions of crime in passing judgment. Most cities contain no more than one or two dozen prisoners, according to Ercan.

And to top it all, women have taken a leading role in every facet of the revolution. Women’s cooperatives are a common sight in Rojava, as are women’s councils, women’s committees, and women’s security forces. Women’s ecovillages have been built both in Rojava and across the border in Turkish Kurdistan, aimed at helping victims of domestic violence and trauma. Patriarchy is just one more aspect of the neoliberal program being cast aside in Rojava, on the road towards building what MEM describes as “a radical democratic, communal, ecological, women-liberated society.”

This piece was originally published on Medium as part of Local Futures’ Planet Local webseries.

Read about other holistic ecological initiatives from around the world on our Planet Local: Ecology page.

Dig deeper into Rojava and the Mesopotamian Ecology Movement on the following pages (the source material for much of this piece):

Sean Keller is Local Futures’ Media and Outreach Coordinator, and editor of Planet Local, an online ‘library’ showcasing grassroots localization projects around the world. He studied Anthropology and Russian at Vassar College, and spends his free time reading and writing speculative fiction.

Photo by Markus Spiske on Unsplash

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 13, 2018 | Movement Building & Support

by Corine Fairbanks / Oglala Lakota American Indian Movement Southeastern Ohio

“Revolutionary struggles cannot achieve collective liberation for all people without addressing patriarchy, nor can women’s freedom be disentangled from racial, economic, & social justice.” -Victoria Law

The Zapatista women will host the First International Gathering of Politics, Art, Sport, and Culture for Women in Struggle in Chiapas, Mexico from March 7-11, 2018. A delegation of women from all walks of life, racial, social-economic, and cultural backgrounds strongly feel that we could learn much from our Zapatista sisters. Their indigenous perspectives and willingness to decolonize and reshape the political landscape into something that works for all people speaks to us as we look at the challenges we face in the US and Canada.

Here is an updated notice that the women of the Zapatista Movement put out.

The desire to go to this gathering and to form this delegation came after much discussion regarding women’s liberation and women voices after the January 20th, 2018 Cincinnati Women’s March. The national theme and platform for Women’s Marches across the United States was “Hear Our Vote”. Many of us were disappointed with this because we felt that it marginalized women that could not vote, or chose not to participate in voting. In response, Black Lives Matter Cincinnati (not affiliated with National BLM) organized an open forum discussion about how to effectively fight for women’s liberation. The dialogue about women’s liberation, was to be approached from several different angles, ideas, and points of view, and addressing the problems of believing that voting is the greatest and most important power as oppressed and exploited people.

There were many subjects touched on, and not everyone in the audience was comfortable with it, yet the forum was a huge success with almost 300 people in attendance, many of whom were standing. Featured panelists included were from Black Lives Matter Cincinnati, American Indian Movement of Southeastern Ohio, Concerned Citizens for Justice, Cincinnati Revolutionary Students, and Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) Metro Cincinnati. Video footage of this panel can be found at Black Lives Matter Cincinnati Facebook group page. The final thoughts concluded that there needs to be more discussion on Women’s liberation, community empowerment, and teaching our young and old people to learn how to organize around these issues.

Then in the first part of January, a few of us within the radical justice community in Cincinnati, saw a call out for the Women’s gathering by the Zapatista Women. Knowing what we know about the Zapatista Army, women play an equal role in leading armed resistance and use the “Revolutionary Law of Women”. This document gives an overview of the combination of social and political struggles that the Zapatista women identified as needing to change. Some of these factors included; Poverty, Rape, Domestic Violence, Access to Health care, Medicine and Treatment, Alcoholism, issues of sovereignty over bodies and land, and to be treated fairly and with equal political voice at home, in the community, and in the Zapatista Army.

The women I spoke with about going to this gathering in Chiapas, agreed that our work in our own communities largely encompasses the same issues with that of the Zapatista women. An Anishinaabe Elder that lives in a rural area of Canada commented that these are the same issues she deals with in working with Residential Boarding School survivors. A Dineh young woman living in Los Angeles, working as a Social Worker for Los Angeles County, said the same thing. As the delegation started quickly forming, it became obvious that in order to continue discussion on women’s liberation, we had to also go to this gathering to get some more “tools” and bring them back to share with our communities to analyze and have critical discussion.

This delegation is led by Native women. We are fundraising for 12 women to attend this gathering in March, Some Native, some not. Some of the Elders and Native women identify with “Indigenous feminism”, some do not. Some of the non-Native women identify as feminists. Yet all of us are working in our communities to better it; to keep our air clean, our waters protected, our lands from being raped by fuel extractions, and collaborating with various grassroots radical and revolutionary organizations on rural and urban landscapes with all of this and with social justice issues too. As activists and organizers, we are women, and we too are fighting to destroy patriarchal systems and structures- even within our own movements and within our Nations/Tribal structures. We believe that what we can learn from the experiences of the Zapatista women can be applied to our everyday struggles and within the current movements in our communities. In addition, we will be having fundraisers with a table set up to encourage attendees to write messages that they want us to take and share with the Zapatista people. We are not just limiting it to fundraising events to gather these messages, but also, we have made this request and offer on social media.

“We women attending the gathering would like to bring our Zapatista Relatives offerings from our homes. If you have any words of solidarity you would like us to share with our Zapatista sisters, please let us know. Upon our return, we hope to have community meetings and discussions to share what we have learned & our Zapatista Relatives responses to your messages as a way to provide a connection to them through us. “

If you are reading this before March 7th, and would like us to include your message, please send me an email at corine68@yahoo.com to be included in our presentation in Chiapas.

This conference is fast approaching and we are making a call out for help. We have fundraisers planned throughout the month of February to meet our goal of $8,000 for travel expenses. Please invest in our communities. Invest in us. Our Delegation is small but our women are from various areas of the US and Canada: represented:

American Indian Movement

Big Mountain Dineh Nation

Black Lives Matter Cincinnati

Biindigen Healing & Arts

Feminactivist

Idle No More Canada

Idle No More Detroit

Women of All Red Nations (WARN)

Water Protectors North/South Dakota

Any dollar amount that you can spare to help us reach this goal would be appreciated. Any effort to spread this message far and wide is greatly appreciated. Here is a link to our go fund me request.

Perhaps this endeavor of getting 12 women to Chiapas for this gathering is a bit ambitious. Perhaps the main purpose is to also role model to other communities that it takes a spark from an idea, and collectively working together, we can make it happen. Either way, we were not going to be intimidated by costs or pessimism to achieve this goal. Our Native Elders have taken this to ceremony and prayer and we feel that the women that are meant to go on this trip, will go. We believe that the 2 most important components to this mission is to first show solidarity because our Struggles are similar. Secondly, to bring back what we learn from our Zapatista Sisters, and share with our families and communities.

As diverse as this delegation is, we all agree that when women are free, communities are empowered, and everyone is free.

WOPILA TANKA /MIIGWECH/ AHEHEE’ / ANUSHIIK / GRACIAS/ THANK YOU

Yours in Solidarity

Corine Fairbanks, Oglala Lakota

American Indian Movement Southeastern Ohio

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 11, 2018 | Movement Building & Support

by Internationalist Commune of Rojava

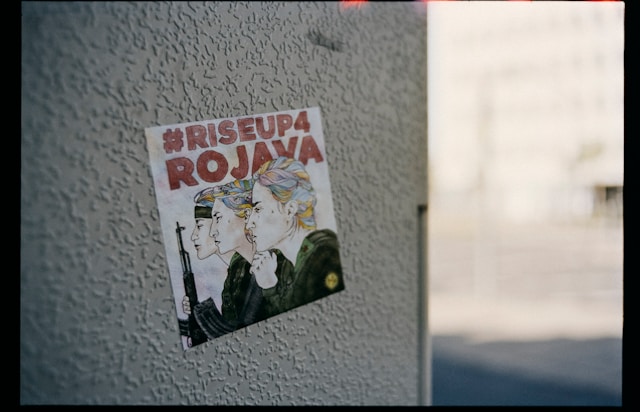

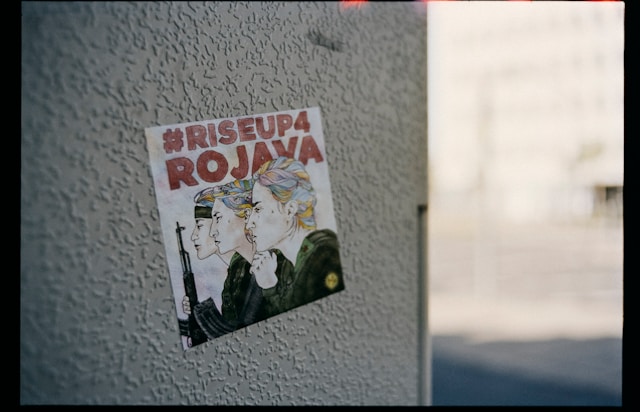

Presentation of the campaign in cooperation with the Democratic Self-governance of Northern Syria

Introduction

Five years have passed since the beginning of the Rojava Revolution. Beginning with the heroic resistance of Kobani, the YPG/YPJ have pushed the reactionary gangs of ISIS back again and again. At the same time, the people of Rojava have successfully resisted all hegemonical attempts to corrupt the revolution. Inspired and shaped by the ideas of Abdullah Öcalan and the struggle of the Kurdish freedom movement, Rojava is a revolutionary project with the aim of challenging capitalist modernity through women’s liberation, ecology, and radical democracy. Despite the ongoing success of the Rojava Revolution, the people remain under pressure; the war against ISIS, the daily terror attacks by the Turkish state and the economic embargo, are obstacles for building up a new society. In this situation, Rojava needs worldwide support more than ever.

Internationalist Commune – learn, support, organize

For many years, we, internationalists from all over the world, have been working on many facets of the Rojava Revolution. Inspired by the revolutionary perspective of the Kurdish freedom movement, we are here to learn, and to support and help develop existing projects. It is our aim to organize a new generation of internationalists to challenge capitalist modernity. Supported by the youth movement in Rojava (YCR/YJC), we established the Internationalist Commune of Rojava in early 2017. To date, our projects have include organizing educational activities, delegations, language courses, and the construction of the first civilian academy for internationalists in Rojava.

A pillar of the revolution: ecology

People who are alienated from nature are alienated from themselves, and are self-destructive. No system has shown this relationship more clearly than capitalist modernity; environmental destruction and ecological crises go hand in hand with oppression and exploitation of people. The feckless mentality of maximum profit has brought our planet close to the edge of the abyss, and left humanity in a whirlwind of war, hunger, and social crisis. Because of this, developing an ecological society is a pillar of the Rojava Revolution, alongside women’s liberation and a total democratization of all parts of life. This is about more than just protecting nature by limiting damage to it; it is about recreating the balance between people and nature. It is about a “renewed, conscious and enlighted unification towards a natural, organic society” (Abdullah Öcalan).

Monoculture, water shortage and air pollution: colonialism against humanity and nature

The results of the capitalist mentality and state violence against society and the environment are clearly visible in Rojava; the Baath regime was and remains uninterested in an ecological society throughout all of Syria. The regime always focused on maximum resource exploitation and high agricultural production rate at the expense of environmental protection, especially in colonized West Kurdistan. Systematic deforestation made monoculture possible: wheat in Cizire Canton, olives in Afrin, and a mixture of both in Kobani have altered the landscape of Rojava. For several decades it was forbidden to plant trees and vegetables, and the population was encouraged by repressive politics and deliberate underdeveloppment of the region to migrate as cheap labour to nearby cities like Aleppo, Raqqa and Homs. Energy production and use (fossil fuels), senseless waste management policies, and careless over-reliance on chemicals in agriculture, damaged the ground, air and water. But the Rojava Revolution and the Rojavan people struggle not only with the ecopolitical heritage of the Baath regime, but also with the ever-present and grave threat of the hostile policies of Turkish State. Beside military attacks, the constant threat of an invasion, and an economic embargo, we also face the problems caused results by Turkish goverment dam construction in occupied North Kurdistan, and the consequent uncontrolled use of groundwater by Turkey for its agriculture. This aggressive siphoning reduces the flow into Rojavan rivers and lowers the whole region’s groundwater level. We are witnessing how Turkish State is systematically closing Rojava’s water tap.

Between war and embargo – ecological works in Rojava

The attempts of the Turkish and Syrian regimes to strangle the revolution in Rojava by military, political and economic attacks, the war against ISIS, and the embargo, supported by the South Kurdish KDP, are creating difficult circumstances for ecological projects in Rojava. Although there are many current projects, including reforestation, creation of natural reserves and environmentally-friendly waste disposal facilities, the infrastructure of the Democratic Self-Administration is still in a difficult material situation, making these goals harder to achieve. The projects of most regional committees are either just beginning or in the planning stage. The ecological revolution, within the larger revolution, is still in its infancy. It lacks environmental consciousness among the population, expert knowledge, necessary technology, and a connection to solidarity from abroad.

Our contribution to the ecological revolution: Make Rojava Green Again

We, the Internationalist Commune of Rojava, want to contribute to the ecological revolution in Northern Syria. To this end, we have started the campaign “Make Rojava Green Again”, campaign in cooperation with the Ecology Committee of the Cizire Canton. The campaign has three aspects:

- Building up the Internationalist Academy with an ecological ethos, to serve as a working example for comparable projects and concepts for the entire society. The academy will facilitate education for internationalists and for the general population of Rojava, to strengthen awareness and environmental consciousness, pushing to build up an ecological society.

- Joining the work of ecological projects for reforestation, and building up a cooperative tree nursery as part of the Internationalist Academy.

- Material support for existing and future ecological projects of the Democratic Self-administration, including sharing of knowledge between activists, scientists and experts with committees and structures in Rojava, developing a long-term perspective for an ecological Northern Syria Federation.

The first two concrete projects of the “Make Rojava Green Again” campaign are:

- Realization of the concepts of an ecological life and work in the Internationalist Academy, partly with the building up a nursery as a part of the Academy. In the spring of 2018, we will plant 2,000 trees in the area of the academy, and 50,000 shoots in the nursery.

- Practical and financial support for the Committee for Natural Conservation in the reforestation of the Hayaka natural reserve, near the city of Derik, in Cizire Canton. Over the next five years, we plan to plant more then 50,000 trees along the shores of Sefan Lake.

The collective work in the nursery will also be a part of the education in the internationalist academy, as well as a concrete expression of solidarity with the communes, institutions, and structures of the population.

‘Make Rojava Green Again’ as a bridge for internationalist solidarity

These are some of the ways people can support the the campaign ‘Make Rojava Green Again’, the ecological work in Rojava, and revolution in Northern Syria.

- Share this campaign with activists, scientists, and experts from fields such as ecological agriculture, forestry, water supply, and sustainable energy production.

- Contact and liaise with activists, journalists, politicians and others who would be interested in this campaign.

- Write, publish and share articles and interviews about the campaign.

- Share information with friends and family. Spread the word about the growing ecological revolution in Rojava.

- Establish contacts between persons/groups/organizations and the Internationalist Commune of Rojava.

- Work in Rojava itself.

- Support the work financially.

Contact: Mail: makerojavagreenagain@riseup.net Web: www.internationalistcommune.com Facebook: facebook.com/CommuneInt Twiter: twitter.com/CommuneInt

Donations to: Rote Hilfe IBAN: CH82 0900 0000 8555 9939 2 BIC: POFICHBEXXX Post Finance Reference: “Make Rojava Green Again”

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 5, 2018 | Movement Building & Support

Editor’s note: This article was roughly transcribed from the video found here.

by Max Wilbert / Deep Green Resistance

Many of you have probably experienced this phenomenon.

You’re at a protest or a direct action or a rally, and people are out in force. The police show up, and they are highly prepared compared to the activists. They are wearing specialized boots and equipment belts with encrypted communication radio devices, handcuffs, pepper spray, flashlights, handguns. They may have specialized gloves, high-performance clothing, and are wearing body armor. Most of them have face protection or at least sunglasses, and sometimes they may have shields as well.

They also have the skills to use this equipment, to do “crowd control,” first aid, and other things that are useful in the conflict setting.

They are ready to move and react in any direction.

In contrast, most activists, organizers, and everyday people who show up to conflict zones don’t have similar equipment or skills. Most people are out there in cotton t-shirts, jeans, impractical shoes, and so on. We’re not prepared to take action, and as a result the outcomes are predictable. Often, law enforcement literally herds us like sheep.

This reflects the different mindset that activists tend to have. We don’t approach these conflicts as if they are as serious as we should.

We are living in a war. This culture is waging a war on the planet, it’s waging a war on the poor, a war on women, a war on people of color, indigenous communities, nonhumans, and so on. It’s a war for control of resources, and it’s been a slaughter for 500 years and more.

One of the reasons it has been a slaughter is this lack of preparation, skills, materials, equipment, and training.

Some of you may be familiar with the work of Sakej Ward, an indigenous warrior from the Mi’kmaq Nation. He has been involved in providing trainings to resistance groups for years, and one of the things that is excellent about his work is the focus on skills and equipment.

We underestimate the importance of this at our own peril.

Right now, most of us don’t know what we are capable of. Without the rights skills and equipment, even the possibility of conducting more serious, risky—and effective—actions seems like a fantasy. We can barely even consider these possibilities.

When a member of the resistance has skills and equipment, a whole range of new possibilities opens up. We need to be prepared to use stealth, to move through rough terrain, to take care of our comrades when they are injured, to evade searches.

We also need to make ourselves less dependent on the system. This includes simple things like carrying water and food with you in your daily life, and especially at actions. We need to be prepared to take care of ourselves and be independent. This enables us to take advantage of fleeting opportunities, navigate emergencies, and to be more effective than we are now.

In short, it gives us freedom to act.

Unfortunately, our best examples of this type of mentality come from the military and police. However, they’re winning. Perhaps we can learn something from them.

We need to be thinking:

- How can we get more independent from the system?

- How can we get the skills that we need to be effective in taking action?

- What equipment do I need?

- How can I always be prepared?

Every activist should consider these questions and begin to answer them in their own context to be able to navigate conflicts now and in the future.

Deep Green Resistance members are working to provide skills and training to our members and to the broader community of activists, eco-warriors, and revolutionaries via outreach and a series of trainings. The next such training takes place in June 2018 at Yellowstone National Park. More information here.

by DGR News Service | Feb 2, 2018 | Culture of Resistance, Direct Action, Movement Building & Support, The Solution: Resistance

Activists, save these dates:

Deep Green Resistance will conduct advanced training in direct action, revolutionary strategy, tactics, and organizing June 22 – 24. This workshop is aimed at providing practical skills and networking to activists, organizers, and revolutionaries interested in saving the planet.

Environmental and social justice activists realize we are losing. Our tactics are failing and things are getting worse. This training will focus on escalation and creative, advanced tactics to increase our effectiveness.

Topics include the use and deployment of soft and hard blockades; hit and run tactics; police interactions; legal repercussions of resistance work; operational security; terrain advantages; strategy; escalation, and more.

The training will be conducted by experienced Deep Green Resistance activists / organizers as well as noted guest speakers (to be announced).

Sessions will be held next to Yellowstone National Park, providing a perfect setting to immerse ourselves in the natural world and activism.

Space is Limited and priority will be given to front-line activists, marginalized communities, and women. And save money with Early Bird Tickets – available for a limited time.

Click this link to apply now: https://deepgreenresistance.org/en/resistance-training-2018

Fitness enthusiasts know that resistance training leads to greater strength. Enhance the effectiveness of your resistance with us this June.