In this essay, first presented in 1977, Audre Lorde argues for women’s solidarity.

The Transformation of Silence Into Language and Action

by Audre Lorde

I would like to preface my remarks on the transformation of silence into language and action with a poem. The title of it is “A Song For Many Movements” and this reading is dedicated to Winnie Mandela. Winnie Mandela is a South African freedom fighter who is in exile somewhere in South Africa. She had been in prison and had been released and was picked up again after she spoke out against the recent jailing of black school children who were singing freedom songs and who were charged with public violence… “A Song for Many Movements.”

Nobody wants to die on the way

and caught between ghosts of whiteness

and the real water

none of us wanted to leave

our bones

on the way to salvation

three planets to the left

a century of light years ago

our spices are separate and particular

but our skins sine in complimentary keys

at a quarter to eight mean time

we were telling the same stories

over and over and over.Broken down gods survive

in the crevasses and mudpots

of every beleaguered city

where it is obvious

there are too many bodies

to cart to the ovens

or gallows

and our uses have become

more important than our silence

after the fall

too many empty cases

of blood to bury or burn

there will be no body left

to listen

and our labor

has become more important

than our silenceOur labor has become

more important

than our silence.

I have come to believe over and over again that what is most important to me must be spoken, made verbal and shared, even at risk of having it bruised or misunderstood. That the speaking profits me, beyond any other effect.

I am standing here as a black lesbian poet, and the meaning of all that wait upon the fact that I am still alive, and might not have been. Less than two months ago I was told by two doctors, one female and one male that I would have to have breast surgery, and that there was a 60 to 80% chance that the tumour was malignant.

Between that telling and the actual surgery there was a three week period of the agony of an involuntary reorganization of my entire life. The surgery was completed, and the growth was benign.

But within those three weeks, I was forced to look upon myself and my living with a harsh and urgent clarity that has left me still shaken but much stronger. This is a situation faced by many women, by some of you here today. Some of what I experienced during that time has helped elucidate for me much of what I feel concerning the transformation of silence into language and action.

Confronting Mortality

In becoming forcibly and essentially aware of my mortality and of what I wished and wanted for my life, however short it might be, priorities and omissions became strongly edged in a merciless light, and what I most regretted with my silences.

Of what I had ever been afraid? To question or to speak as I believed could’ve meant pain, or death. But we all hurt in so many different ways, all the time, and pain will either change or end.

Death on the other hand is the final silence and that might be coming quickly, now, without regard for whether I had ever spoken what needed to be said, or had only betrayed myself into small silences, while I planned someday to speak, or waited for someone else’s words. And I began to recognize a source of power within myself that comes from the knowledge that while it is most desirable not to be afraid, learning to put fear into perspective gave me great strength.

I was going to die, if not sooner then later, whether or not I have ever spoken myself. My silence has not protected me. Your silence will not protect you. But for every real spoken word, for every attempt I have ever made to speak those truths for which I am still seeking, I had made contact with other women while we examined the words to fit a world in which we all believed, bridging our differences. And it was the concern and caring of all those women which gave me strength and enabled me to scrutinize the essentials of my living.

The women who sustained me throughout that period were black and white, old and young, lesbian, bisexual and heterosexual, and we all shared a war against the tyrannies of silence. They all gave me a strength and concern without which I could not have survived intact.

Casualty and Warrior

Within those weeks of acute fear came the knowledge – within the war we are all waging with the forces of death, subtle and otherwise, conscious or not – I am not only casualty, I am also a warrior.

What the words you do not yet have? What do you need to say? What are the tyrannies you swallow day by day and attempt to make your own, until you will sicken and die of them, still in silence?

Perhaps for some of you here today, I am the face of one of your fears. Because I am woman, because I am black, because I am lesbian, because I am myself – a black woman warrior poet doing my work and come to ask you, are you doing yours?

And of course I am afraid because the transformation of silence into language and action is an act of self revelation, and that always seems fraught with danger.

But my daughter when I told her of our topic and my difficulty with it, said, “tell them about how you’re never really a whole person if you remain silent, because there’s always one little piece inside you that wants to be spoken out and if you keep ignoring it, it gets madder and madder and hotter and hotter, and if you don’t speak it out one day it will just up and punch you in the mouth from the inside.”

Silence and Fear

In the cause of silence each of us draws the face of her own fear-fear of contempt, of censure, or some judgement or recognition, of challenge, of annihilation.

But most of all, I think we fear the visibility without which we cannot truly live. Within this country where racial difference creates constant, if unspoken, distortion of vision, black women have on one hand always been highly visible, and so, on the other hand, have been rendered invisible through the depersonalization of racism. Even within the women’s movement, we have had to fight, and still do, for that very visibility which also renders us most vulnerable, our blackness.

For to survive in the mouth of this dragon we call america we have had to learn this first and most vital lesson that we were never meant to survive. Not as human beings and neither were most of you here today, black or not. And that visibility which makes us most vulnerable is that which also is the source of our greatest strength because the machine will try to grind you into dust anyway, whether or not we speak.

We can sit in our corners mute forever while our sisters and ourselves are wasted, while our children are distorted and destroyed, while our Earth is poisoned; we can sit in our safe corners mute as bottles and we will still be no less afraid.

In my house this year we are celebrating the feast of Kwanzaa, The African-American Festival of harvest which begins the day after Christmas and lasts for seven days. There are seven principles, one for each day. The first principle is Umoja, which means unity, the decision to strive for and maintain unity in self and community. The principle for yesterday, the second day was Kujichagulia -self-determination – the decision to define ourselves, name ourselves, and speak for ourselves, instead of being defined and spoken for by others.

Today is the third day and the principle for today is Umija, collective work and responsibility-the decision to build and maintain ourselves and our communities together and to recognize and solve our problems together. Each of us is here now because in one way or another we share a commitment to language and the power of language, and to the reclaiming of that language which has been made to work against us.

The Transformation of Silence Into Action

In the transformation of silence into language and action, it is vitally necessary for each one of us to establish or examine her function in that transformation and to recognize her role as vital within that transformation.

For those of us who write, it is necessary to scrutinize not only the truth of what we speak, but the truth of that language by which we speak it. For others, it is to share and spread also those words that are meaningful to us but primarily for us all, it is necessary to teach by living and speaking those truths by which we believe and know beyond understanding. Because in this way alone we can survive, by taking part in a process of life that is creative and continuing, that is growth.

And it is never without fear – of visibility, of the harsh light of scrutiny and perhaps judgement, of pain, of death. But we have lived through all of those already in silence, except death. And I remind myself all the time now that if I were to have been born mute, or had maintained an oath of silence my whole life long for safety, I would still have suffered, and I would still die. It is very good for establishing perspective.

And where the words of women are crying to be heard we must each other’s recognize our responsibility to seek those words out, to read them and share them and examine them in their pertinent to our lives.

That we not hide behind the mockeries of separations that have been imposed upon us and which so often we accept as our own. For instance “I can’t possibly teach black women’s writing on their experience is so different from mine.” Yet how many years have you spent teaching Plato and Shakespeare and processed? Or another, “she is a white woman and what could she possibly have to say to me?“ Or, “she’s a lesbian, what would my husband say, or my chairman?“ Or again, “this woman writes of her sons and I have no children.“

And all the other endless ways in which we rob ourselves and each other we can learn to speak when we are afraid in the same way we have learnt to work and speak when we are tired. For we have been socialized to respect fear more than our own needs for language and definition, and while we wait in silence for that final luxury of fearlessness, the weight of that silence will choke us.

The fact that we are here and that I speak these words in an attempt to break that silence and bridge some of those differences between us, for it is not difference that which immobilizes us, but silence.

And there are so many silences to be broken.

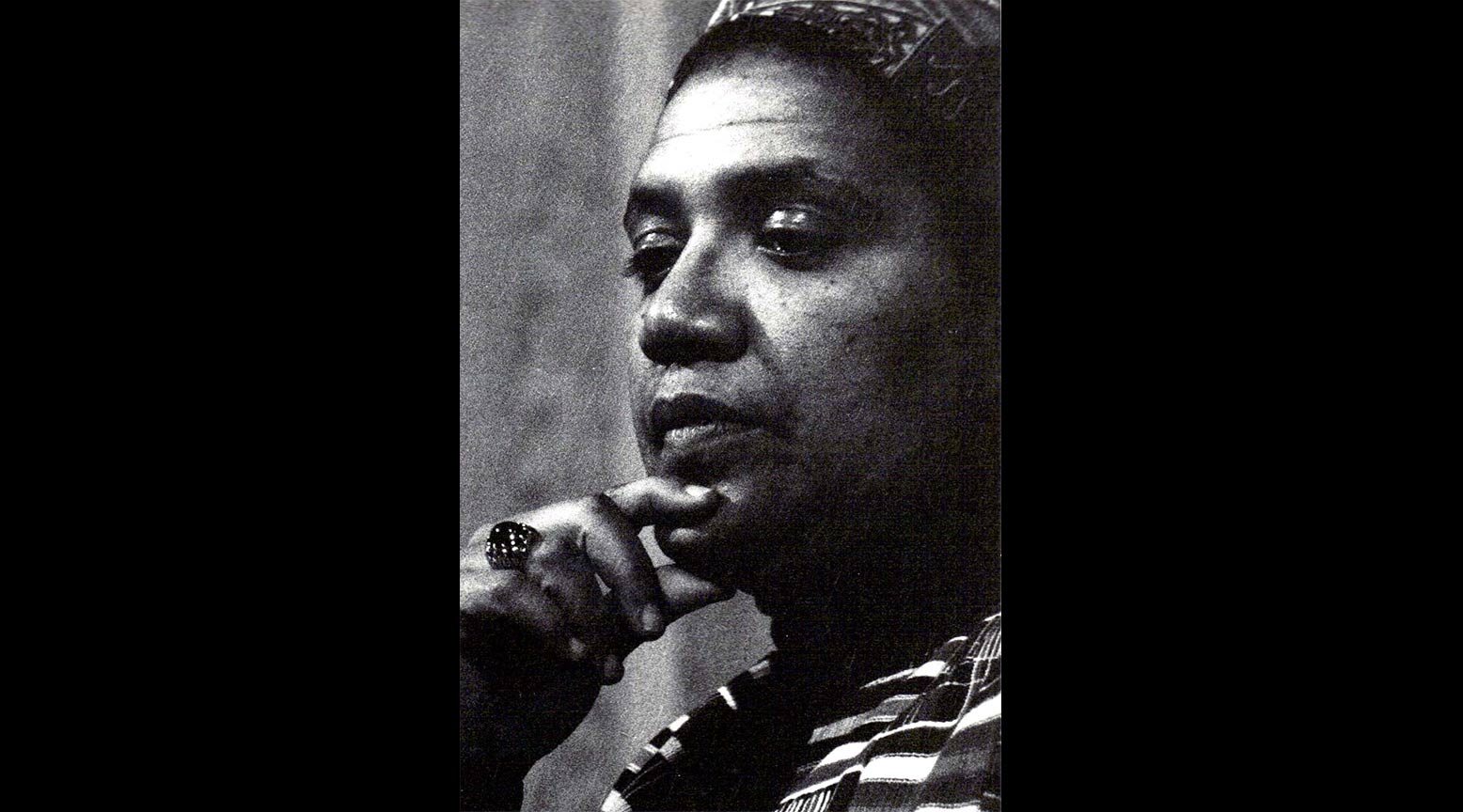

Audre Lorde (February 18, 1934 – November 17, 1992) was an American writer, feminist, womanist, librarian, and civil rights activist. She was a self-described “black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet,” who dedicated both her life and her creative talent to confronting and addressing injustices of racism, sexism, classism, heterosexism, and homophobia.

This essay is from “Audrey Lord, I am your sister: collected and unpublished writings of Audre Lorde,” 2009, Oxford University press. This essay was first delivered as a paper at the Modern Language Associations lesbian and literature panel in Chicago on December 28, 1977.

Featured image by K. Kendall, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic.