by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Sep 21, 2017 | Lobbying

Featured image: The 2015 Gold King Mine waste water spill in the Animas River, in southwest Colorado. The Animas is a tributary to the Colorado River.

Editor’s note: The first Rights of Nature lawsuit in the US was filed on September 25, 2017, in Denver, Colorado. The full text of the complaint can be found here.

“Contemporary public concern for protecting nature’s ecological equilibrium should lead to the conferral of standing upon environmental objects to sue for their own preservation.” Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, Sierra Club v. Morton (1972)

Denver, Colorado–In a first-in-the-nation lawsuit filed in federal court, the Colorado River is asking for judicial recognition of itself as a “person,” with rights of its own to exist and flourish. The lawsuit, filed against the Governor of Colorado, seeks a recognition that the State of Colorado can be held liable for violating those rights held by the River.

The Plaintiff in the lawsuit is the Colorado River itself, with the organization Deep Green Resistance – an international organization committed to protecting the planet through direct action – filing as a “next friend” on behalf of the River. The River and the organization are represented in the lawsuit by Jason Flores Williams, a noted civil rights lawyer and lead attorney in a recent class-action case filed on behalf of Denver’s homeless population.

While this is the first action brought in the United States which seeks such recognition for an ecosystem, such actions and laws are becoming more common in other countries. In 2008, the country of Ecuador adopted the world’s first national constitution which recognized rights for ecosystems and nature; over three dozen U.S. municipalities, including the City of Pittsburgh, have adopted similar laws; and courts in India and Colombia have recently recognized that rivers, glaciers, and other ecosystems may be treated as “persons” under those legal systems.

Serving as an advisor to the lawsuit is the Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund (CELDF), a nonprofit public interest law firm which has previously assisted U.S. municipalities and the Ecuadorian government to codify legally enforceable rights for ecosystems and nature into law.

Attorney Flores-Williams explained that “current environmental law is simply incapable of stopping the widescale environmental destruction that we’re experiencing. We’re bringing this lawsuit to even the odds – corporations today claim rights and powers that routinely overwhelm the efforts of people to protect the environment. Our judicial system recognizes corporations as “persons,” so why shouldn’t it recognize the natural systems upon which we all depend as having rights as well? I believe that future generations will look back at this lawsuit as the first wave of a series of efforts to free nature and our communities from a system of law which currently guarantees their destruction.”

Deanna Meyer, a member of Deep Green Resistance and one of the “next friends” in the lawsuit, affirmed Flores-Williams’ sentiments, declaring that “without the recognition that the Colorado River possesses certain rights of its own, it will always be subject to widescale exploitation without any real consequences. I’m proud to stand with the other “next friends” in this lawsuit to enforce and defend the rights of the Colorado, and we’re calling on groups across the country to do the same to protect the last remaining wild places in this country and beyond.”

The lawsuit seeks recognition by the Court that the Colorado River Ecosystem possesses the rights to exist, flourish, regenerate, and restoration, and to recognize that the State of Colorado may be held liable for violating those rights in a future action. The complaint will be filed in the US District Court of Colorado on Tuesday.

Media inquiries:

Law Office of Jason Flores-Williams

303-514-4524

Thomas Linzey, Executive Director, CELDF

717-977-6823

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Sep 6, 2017 | Lobbying

Featured image: This Baka woman and her husband are among many tribal people in Cameroon who have been beaten by WWF-funded wildlife guards. They were attacked and had their belongings taken from them while they were collecting wild mangoes. © Survival International

by Survival International

The landmark mediation talks between Survival and the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) over breaches of Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) guidelines for multinational corporations have broken down over the issue of tribal peoples’ consent.

Survival had asked WWF to agree to secure the Baka “Pygmies’” consent for how the conservation zones on their lands in Cameroon were managed in the future, in line with the organization’s own indigenous peoples policy.

WWF refused, at which point Survival decided there was no purpose continuing the talks.

Survival lodged the complaint in 2016, citing the creation of conservation zones on Baka land without their consent, and WWF’s repeated failure to take action over serious human rights abuses by wildlife guards it trains and equips.

It is the first time a conservation organization has been the subject of a complaint under the OECD guidelines. The resulting mediation was held in Switzerland, where WWF is headquartered.

WWF has been instrumental in the creation of several national parks and other protected areas in Cameroon on the land of the Baka and other rainforest tribes. Its own policy states that any such projects must have the free, prior and informed consent of those affected.

A Baka man told Survival in 2016: “[The anti-poaching squad] beat the children as well as an elderly woman with machetes. My daughter is still unwell. They made her crouch down and they beat her everywhere – on her back, on her bottom, everywhere, with a machete.”

Another man said: “They told me to carry my father on my back. I walked, they beat me, they beat my father. For three hours. Every time I cried they would beat me, until I fainted and fell to the ground.”

Conservation has been used as a justification for forcibly denying Baka access to their land, but the destruction of the rainforest by logging companies – some of whom are WWF partners – has continued. © Margaret Wilson/Survival

Background briefing

– Survival first raised its concerns about WWF’s projects on Baka land in 1991. Since then, Baka and other local people have repeatedly testified to arrest and beatings, torture and even death at the hands of WWF-funded wildlife guards.

– The OECD is the Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development. It publishes guidelines on corporate responsibility for multinationals, and provides a complaint mechanism where the guidelines have been violated.

– The complaint was lodged with the Swiss national contact point for the OECD, as WWF has its international headquarters in Switzerland. Talks took place in the Swiss capital, Bern, between representatives of WWF and Survival.

– The principle of Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) is the bedrock of international law on indigenous peoples’ rights. It has significant implications for big conservation organizations, which often operate on tribal peoples’ land without having secured their consent.

Tribes like the Baka have lived by hunting and gathering in the rainforests of central Africa for generations, but their lives are under threat. © Selcen Kucukustel/Atlas

Tribal peoples like the Baka have been dependent on and managed their environments for millennia. Contrary to popular belief, their lands are not wilderness. Evidence proves that tribal peoples are better at looking after their environment than anyone else. Despite this, WWF has alienated them from its conservation efforts in the Congo Basin.

The Baka, like many tribal peoples across Africa, are accused of “poaching” because they hunt to feed their families. They are denied access to large parts of their ancestral land for hunting, gathering, and sacred rituals. Many are forced to live in makeshift encampments on roadsides where health standards are very poor and alcoholism is rife.

Meanwhile, WWF has partnered with logging corporations such as Rougier, although these companies do not have the Baka’s consent to log the forest, and the logging is unsustainable.

Survival’s Director Stephen Corry said: “The outcome of these talks is dismaying but not really surprising. Conservation organizations are supposed to ensure that the ‘free, prior and informed consent’ of those whose lands they want to control has been obtained. It’s been WWF’s official policy for the last twenty years.

“But such consent is never obtained in practice, and WWF would not commit to securing it for their work in the future.

“It’s now clear that WWF has no intention of seeking, leave alone securing, the proper consent of those whose lands it colludes with governments in stealing. We’ll have to try other ways to get WWF to abide by the law, and its own policy.”

Watch: Baka father speaks out against horrific abuse

“Pygmy” is an umbrella term commonly used to refer to the hunter-gatherer peoples of the Congo Basin and elsewhere in Central Africa. The word is considered pejorative and avoided by some tribespeople, but used by others as a convenient and easily recognized way of describing themselves.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Aug 23, 2017 | Lobbying

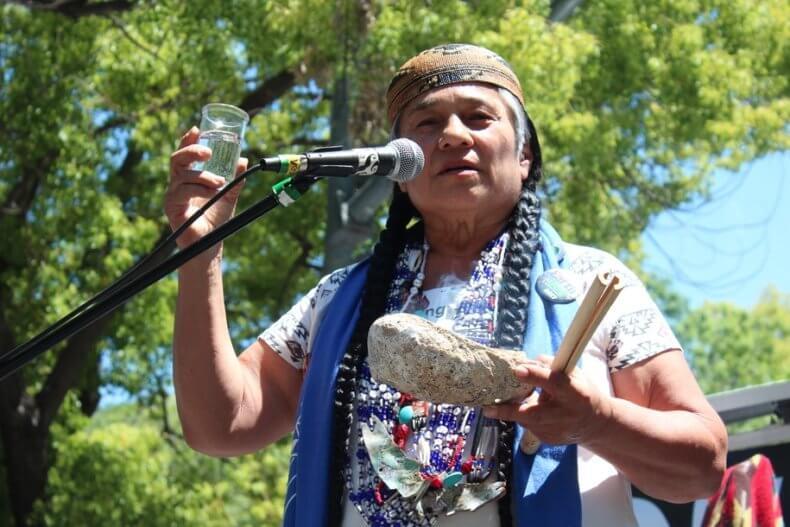

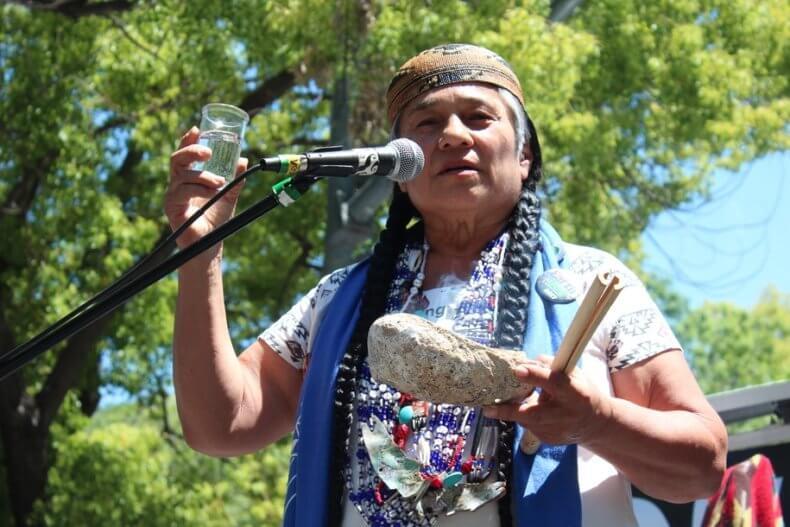

Featured image: Caleen Sisk, Chief and Spiritual Leader of the Winnemem Wintu Tribe, speaks at the Oil Money Out, People Power In rally in Sacramento on May 20. Photo by Dan Bacher.

by Dan Bacher / Intercontinental Cry

On August 17, a California Indian Tribe, two fishing groups, and two environmental organizations joined a growing number of organizations, cities and counties suing the Jerry Brown and Donald Trump administrations to block the construction of the Delta Tunnels.

The Winnemem Wintu Tribe, North Coast Rivers Alliance (NCRA), Institute for Fisheries Resources (IFR), Pacific Coast Federation of Fishermen’s Associations (PCFFA) and the San Francisco Crab Boat Owners Association filed suit against the California Department of Water Resources (DWR) in Sacramento Superior Court to overturn DWR’s approval of the Twin Tunnels, also know as the California WaterFix Project, on July 21, 2017

”The Winnemem Wintu Tribe has lived on the banks of the McCloud River for thousands of years and our culture is centered on protection and careful, sustainable use of its salmon,” said Caleen Sisk, Chief of the Winnemem Wintu Tribe near Mt. Shasta. “Our salmon were stolen from us when Shasta Dam was built in 1944. “

”Since that dark time, we have worked tirelessly to restore this vital salmon run through construction of a fishway around Shasta Dam connecting the Sacramento River to its upper tributaries including the McCloud River. The Twin Tunnels and its companion proposal to raise Shasta Dam by 18 feet would push the remaining salmon runs toward extinction and inundate our ancestral and sacred homeland along the McCloud River,” Chief Sisk stated.

The Trump and Brown administrations and project proponents claim the tunnels would fulfill the “coequal goals” of water supply reliability and ecosystem restoration, but opponents point out that project would create no new water while hastening the extinction of winter-run Chinook salmon, Central Valley steelhead, Delta and longfin smelt, green sturgeon and other imperiled fish species

The project would also imperil the salmon and steelhead populations on the Trinity and Klamath rivers that have played a central role in the culture, religion and livelihood of the Yurok, Karuk and Hoopa Valley Tribes for thousands of years.

The tunnels would divert 9,000 cubic feet per second of water from the Sacramento River near Clarksburg and transport it 35 miles via two tunnels 40-feet in diameter for export to San Joaquin Valley agribusiness interests and Southern California, according to lawsuit documents. The project would divert approximately 6.5 million acre-feet of water per year, a quantity sufficient to flood the entire state of Rhode Island under nearly 7 feet of water.

The groups pointed out that this “staggering” quantity of water – equal to most of the Sacramento River’s flow during the summer and fall – would “exacerbate the Delta’s severe ecological decline,” pushing several imperiled species of salmon and steelhead closer to extinction.

Stephan Volker, attorney for the Tribe and organizations, filed the suit. The suit alleges that DWR’s approval of the California WaterFix Project and certification of its Environmental Impact Report violates the California Environmental Quality Act (“CEQA”), the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta Reform Act of 2009, and the Public Trust Doctrine.

“The Public Trust Doctrine protects the Delta’s imperiled fish and wildlife from avoidable harm whenever it is feasible to do so,” according to lawsuit documents. “Contrary to this mandate, the Project proposes unsustainable increases in Delta exports that will needlessly harm public trust resources, and its FEIR dismisses from consideration feasible alternatives and mitigation measures that would protect and restore the Delta’s ecological functions. Because the Project sacrifices rather than saves the Delta’s fish and wildlife, it violates the Public Trust Doctrine.”

Representatives of the fishing and environmental groups explained their reasons for filing the lawsuit.

“The…Twin Tunnels is a hugely expensive boondoggle that could pound the final nail in the coffin of Northern California’s salmon and steelhead fishery,” stated Noah Oppenheim, Executive Director of the Pacific Coast Federation of Fishermen’s Associations (PCFFA). “There is still time to protect these declining stocks from extinction, but taking more water from their habitat will make matters far worse.”

Larry Collins, President of the San Francisco Crab Boat Owners Association, stated, “Our organization of small, family-owned fishing boats has been engaged in the sustainable harvest of salmon and other commercial fisheries for over 100 years. By diverting most of the Sacramento River’s flow away from the Delta and San Francisco Bay, the Twin Tunnels would deliver a mortal blow to our industry and way of life.”

Frank Egger, President of the North Coast Rivers Alliance, stated that “the imperiled salmon and steelhead of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers are one of Northern California’s most precious natural resources. They must not be squandered so that Southern California can avoid taking the water conservation measures that many of us adopted decades ago.”

Chief Sisk summed up the folly of Brown’s “legacy project,” the Delta Tunnels, at her speech at the “March for Science” on Earth Day 2017 before a crowd of 15,000 people at the State Capitol in Sacramento.

“The California Water Fix is the biggest water problem, the most devastating project, that Californians have ever faced,” said Chief Sisk. “Just ask the people in the farmworker communities of Seville and Alpaugh, where they can’t drink clean water from the tap.”

“The twin tunnels won’t fix this problem. All this project does is channel Delta water to water brokers at prices the people in the towns can’t afford,” she stated.

To read the full story, go to: www.sandersinstitute.com/…

The lawsuit filed by Volkers joins an avalanche of lawsuits against the Delta Tunnels. Sacramento, San Joaquin and Butte Counties have already filed lawsuits against the California WaterFix — and more lawsuits are expected to join these on Monday, August 21.

On June 29, fishing and environmental groups filed two lawsuits challenging the Trump administration’s biological opinions permitting the construction of the controversial Delta Tunnels.

Four groups — the Golden Gate Salmon Association (GGSA), the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), Defenders of Wildlife, and the Bay Institute — charged the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and National Marine Fisheries Service for violating the Endangered Species (ESA), a landmark federal law that projects endangered salmon, steelhead, Delta and longfin smelt and other fish species. The lawsuits said the biological opinions are “arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion.”

On June 26, the Trump administration released a no-jeopardy finding in their biological opinions regarding the construction of the Delta Tunnels, claiming that the California WaterFix “will not jeopardize threatened or endangered species or adversely modify their critical habitat.” The biological opinions are available here: www.fws.gov/…

Over the past few weeks, the Brown administration has incurred the wrath of environmental justice advocates, conservationists and increasing numbers of Californians by ramrodding Big Oil’s environmentally unjust cap-and-trade bill, AB 398, through the legislature; approving the reopening of the dangerous SoCalGas natural gas storage facility at Porter Ranch; green lighting the flawed EIS/EIR documents permitting the construction of the California WaterFix; and issuing a “take” permit to kill endangered salmon and Delta smelt in the Delta Tunnels.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Aug 17, 2017 | Lobbying

Featured image: Brazilian Indians have been protesting in Brasilia against the government’s anti-indigenous proposals. © APIB

by Survival International

Indigenous activists and human rights campaigners around the world yesterday celebrated Brazil’s Supreme Court ruling unanimously in favor of indigenous land rights.

In two land rights cases, all eight of the judges present voted for indigenous land rights and against the government of Mato Grosso state, in the Amazon, which was demanding compensation for lands mapped out as indigenous territories decades ago.

Although ruling on one further case was postponed, this outcome has been seen as a significant victory for indigenous land rights in the country.

An international campaign was launched earlier this month after President Temer attempted to have a controversial legal opinion on tribal land recognition adopted as policy.

The proposal stated that indigenous peoples who were not occupying their ancestral lands on October 5, 1988, when the country’s current constitution came into force, would no longer have the right to live there. This new proposal was referred to as the “marco temporal” or “time frame” by activists and legal experts.

If the judges had accepted this, it would have set indigenous rights in the country back decades, and risked destroying dozens of tribes. The theft of tribal land destroys self-sufficient peoples and their diverse ways of life. It causes disease, destitution and suicide.

The new policy would have massively undermined the Guarani’s attempts to regain their ancestral land, most of which has been taken over by agribusiness. © Anon/Survival

In response to the ruling, Luiz Henrique Eloy, a Terena Indian lawyer, said: “This is an important victory for the indigenous peoples of these territories. The Supreme Court recognised their original [land] rights and this has national repercussions, because the Supreme Court indicated that it was against the concept of the time frame.”

APIB, Brazil’s pan-indigenous organization, led a protest movement, under the slogan “our history didn’t start in 1988.”

The measure is being opposed by Indians across Brazil. Eliseu Guarani from the Guarani Kaiowá people in the southwest of the country said: “If the time frame is enforced, there will be no more legal recognition of indigenous territories… there is violence, we all face it, attacks by paramilitaries, criminalization, racism.”

Survival International led an international outcry against the proposal, calling on supporters around the globe to petition Brazil’s leaders and high court to reject the opinion. Over 4,000 emails were sent directly to senior judicial figures and other key targets.

While the ruling does not end the possibility of further attacks on tribal land rights in Brazil, it is a significant victory against the country’s notorious agribusiness lobby, who have very close ties to the Temer government.

Survival’s Director Stephen Corry said: “If the judges had accepted this proposal it would have set back indigenous rights in the country by decades. Brazil’s indigenous peoples are already battling a comprehensive assault on their lands and identity – a continuation of the invasion and genocide which characterized the European colonization of the Americas. We’re hugely grateful for the energy and enthusiasm of our supporters in helping the Indians fight back against this disastrous proposal.”

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jul 3, 2017 | Lobbying, Protests & Symbolic Acts

by Michael Bucci / Deep Green Resistance New York

Honorable Daniel F. McCarthy, Town Justice

Town of Cortlandt Justice Court

One Heady Street, Cortlandt Manor, New York 10567

Re: Order to Appear at Violation of Conditional Discharge Hearing-June 29, 2017, Docket # 15110186

Dear Judge McCarthy,

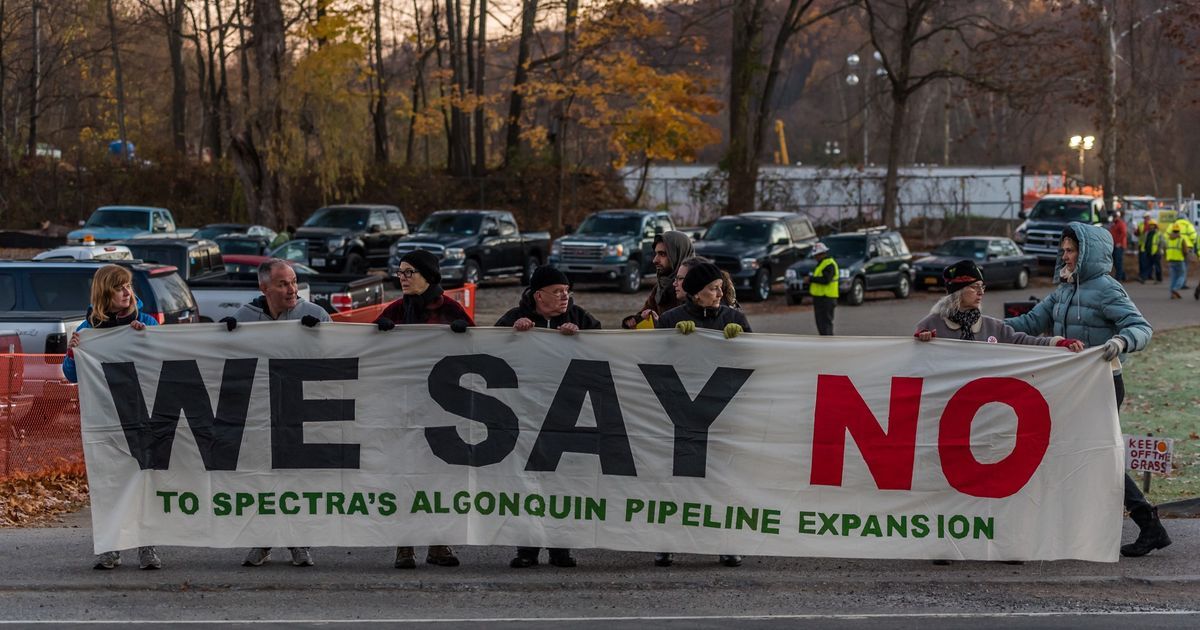

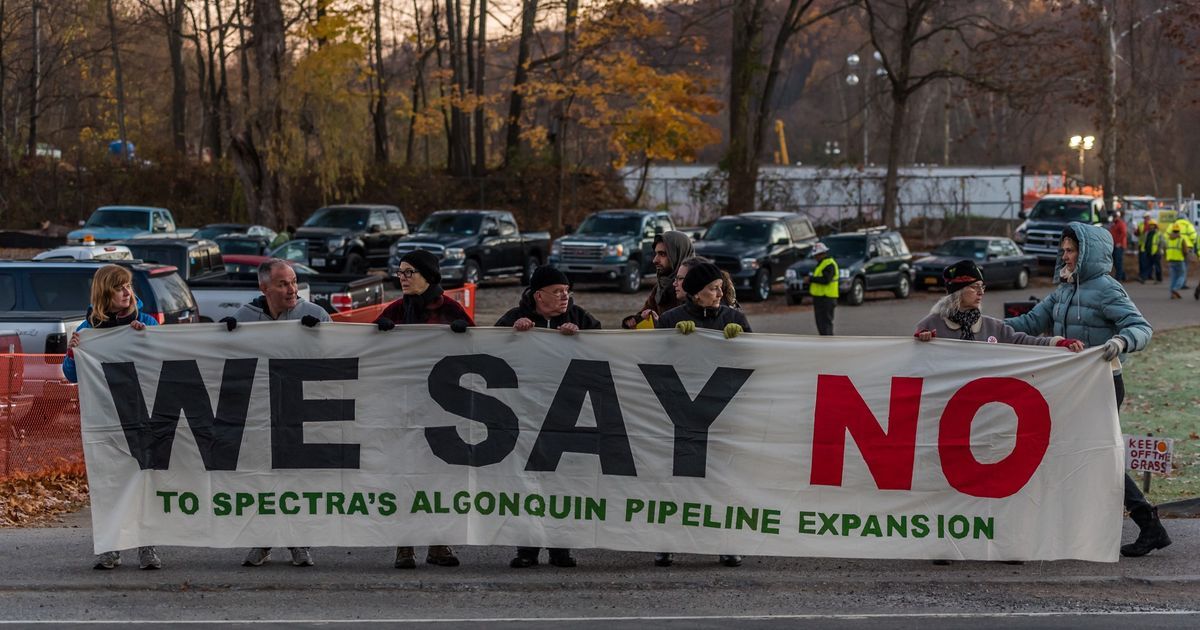

Thank you for the opportunity to present our necessity defense during our trial and to explain why we were, on that chilly morning in November, 2015, blockading the construction of Spectra Energy’s Algonquin Incremental Market Project pipeline that runs 400 feet from elementary schools and homes, and 105 feet from critical safety infrastructure at the failed Indian Point nuclear power plant on the Hudson River in Westchester County, NY.

I accept full responsibility for my action. We were all prepared for jail-time. I do realize that the sentence you imposed on us is an attempt to keep us out of jail. And I appreciate that.

I cannot, however, comply with certain provisions of your sentence which includes a 12-month conditional discharge, community service requirements, and fines/fees of $350.00. I cannot comply because the sentence imposed on us Montrose 9 resisters, who oppose the construction of this 42 inch, high-pressure, fracked methane-gas pipeline in our community, is actually a form of punishment meant to keep activists like us fearful, quiet and acquiescent. The sentence seems very harsh to me, especially as an alternative to incarceration, and for just a violation: a non-criminal infraction virtually equivalent to a traffic ticket! The sentence imposed is an attempt to break our will and bully us into submission.

In all honesty, I cannot abide by your conditional discharge requirement not to be arrested over the next year fighting this pipeline. This is a form of judicial repression meant to keep us from freely exercising our first amendment, constitutional rights to protest and resist, in this case, the much greater harm that fossil fuels and greenhouse gasses are wreaking on communities. Our necessity defense at trial, in a very real way, coupled with the dire environmental crises we face and injustices worldwide, require us to continue our resistance efforts in an even more concerted way — disrupting the fossil fuel industry, and perhaps breaking the law whenever necessary, to prevent or diminish the much greater harms of global heating, climate catastrophe and eventual systemic environmental collapse.

I cannot agree to not fighting for justice, alongside my friends, for fear of being arrested when so many injustices must be made right, especially these days, when we need to act powerfully and intelligently to dismantle entrenched systems of oppression. We will even need to directly break some unjust laws, like the unconstitutional and mean Muslim ban, for example. Given the enormous environmental harm being done to our living planet, and the efforts to divide us from one another, we will need to be smarter and even more militant, not less so, in keeping the powerful from harming humans and the living planet, while we build diverse and strong communities of love, support and resistance, like we are doing.

Moreover, we did no harm to the community. In fact, we alerted the community to impending crises. Requiring us to perform community service for fighting on behalf of our neighbors, for trying to protect our community, the water and the land base, from devastation and degradation, I consider wrong-headed and almost insulting, given the way I have tried to live my life in service to the betterment of our communities. (Please see details of my work and “community service” activities, attached.) *

You know that I also disagree with your verdict of guilty both on the merits of the case and with respect to our necessity defense. Regarding who was responsible for the traffic blockage on Route 9A, I do not think that the prosecution actually proved their case, that we were the cause of the traffic jam. There was sufficient doubt given the obvious failure of the State Police to control traffic, which would have taken minimal effort on their part. I also believe we proved the elements of our necessity defense. The harm of burning fossil fuels, especially methane, 80 times more harmful than CO2, is overwhelming and imminent, locally and globally. Threatening our community and destroying the environment for profit with impunity is what is wrong. I doubt that a jury would have found us guilty.

Admittedly, the Montrose 9 was not successful in our efforts to stop this segment of Spectra’s pipeline. We now need to stop the next segment, Atlantic Bridge Project, and all pipelines, and end the entire fossil fuel industry (and ultimately industrial capitalism, male domination and institutionalized racism) from destroying lives. I realize that from now on we will need to organize better and become more effective in our resistance to the extraction, storage and burning of fossil fuels, the massive infrastructure build out, as well as climate injustice against the poor, people of color and front-line indigenous peoples around the world.

As you know from our individual testimonies, we tried just about every avenue to stop the pipeline construction. In fact, many of our elected officials even agreed with us, but they were virtually powerless and/or chose not to effectively help us. Moreover, regulators continually ignored the calls of citizens and elected officials for independent health and safety assessments of this massive pipeline expansion project. Clearly, government and laws are on the side of the corporations, the rich and powerful, all of whom prioritize profits over the well-being of citizens. The law and the courts should be protecting communities from the abuses of corporations and government. The completed segment of pipeline we unsuccessfully resisted is a symptom of the failed political & economic system, a failed democracy & collapsing institutions that do not represent the interests of people or life on our planet. Indeed, we all must go way beyond our comfort zones and do everything necessary to make our world safer, to the degree that each of us can.

These days, we need the help of an independent judiciary, and judicial heroes like Constance Baker Motley and Thurgood Marshall, jurists remembered for their understanding of how citizens and communities need special legal protections from longstanding oppressive institutions, and how important it is to safeguard the civil rights of groups who are systematically targeted by oppression, especially when existing law and precedent are not on their side. They took bold, extraordinary steps, and were successful on behalf of the civil and human rights of communities of color, and all communities, against enormous odds.

I am hopeful that we both love this beautiful community on the Hudson River and want to see it thrive, and be a safe and healthy place to live. Yes, we were hoping that you would side with us against Spectra (now Enbridge) Energy and agree that their harm to this community, and destruction of the living environment for profit, would be what is considered unlawful and should be stopped. I am still hopeful that on a deeply human level, we both want the very best for our community.

Therefore, Judge McCarthy, I am asking you for your help in our efforts to stop this pipeline. If I may be so audacious, we really could use your help in this long, hard fight on behalf of our communities. We need your help and assistance from the judicial branch of government for relief, protection and support, especially since some laws may need to be challenged for the greater good to prevent greater harm. Yes, I invite you to consider joining our efforts. Together, we could definitely keep our community safer.

If you cannot yet support us and our efforts, I ask you simply to consider, at least – to think about – what we and the science and the experts have been saying about the dangers of this pipeline, methane gas leakage in our already vulnerable community, the harm of greenhouse gas emissions, and our responsibility to protect our homes and the earth. Please consider this an invitation and an opportunity to continue our year-and-a-half-long conversation about community health and safety and protection from the harms of the fossil fuel industry. While we continue our efforts to stop the construction of this pipeline with our neighbors, and fight to make our community safer, I hope we will continue this important conversation.

I appreciate your respecting my constitutional right to defend myself, & speak on my own behalf, pro se.

Sincerely,

Michael G. Bucci

Deep Green Resistance

Montrose 9 Defendant

* “Community Service” Activities

Catholic Interracial Council, Pittsburgh, PA 1964-66 – volunteer member.

Little Sisters of the Poor (homes for the elderly), Balt., MD & Wash., D.C. 1966-68 – volunteer.

Co-Founder, Storefront Soup Kitchen/Peace Center, Bronx, NY 1970-73, – volunteer.

Resistance activities/organizing to stop the Vietnam war 1969-74.

So Others Might Eat – SOME Soup Kitchen, Wash., DC 1974-75, – volunteer director.

American Red Cross in Greater New York Disaster Relief Services 1975-1977.

Clinton Housing Development Company – community organizer 1978-1981.

Co-Founded Union of City Tenants 1979-83, – volunteer.

Volunteer – New York Women Against Pornography 1984-85.

Co-founder, Men Against Pornography 1985? – volunteer.

Co-founder, New York Men Against Sexism 1989 – volunteer.

Resistance to South African apartheid 1989-1994.

Co-founder, Whites Against Racism Network (WARN) 1990-1993 – volunteer

Bowery Residents Committee – Director of Housing and Development 1981-1997.

ANHD – Affordable Housing Training to 95 under-resourced NYC community groups 2010-17.

American Red Cross in Greater New York Disaster Relief Services 9/11 volunteer.

We Are Seneca Lake – Fossil Fuel Storage Resistance – volunteer 2014-17.

Compressor Free Franklin – volunteer 2014-Present.

Deep Green Resistance – volunteer 2014-Present.

Resist Spectra – volunteer 2015-Present.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jun 23, 2017 | Lobbying

by Center for Biological Diversity

SAN FRANCISCO— Conservationists sued the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Wildlife Services program today over its outdated wildlife-killing plan for Northern California.

The lawsuit, filed in San Francisco federal court, seeks an updated environmental analysis of the program’s killing of native wildlife including coyotes, bobcats and foxes.

“Wildlife Services’ cruel killing practices are ineffective, environmentally harmful and totally out of touch with science,” said Collette Adkins, a Center for Biological Diversity attorney representing the conservation groups involved in the lawsuit. “It’s long past time that Wildlife Services joined the 21st century and updated its practices to stop the mass extermination of animals. Nonlethal methods for dealing with human-wildlife conflicts have been shown to work. We have no choice but to sue the agency and force a closer look at those alternatives.”

Wildlife Services is a multimillion-dollar federal program that uses painful leghold traps, strangulation snares, poisons and aerial gunning to kill wolves, coyotes, cougars, birds and other wild animals — primarily to benefit the agriculture industry.

Last year the program reported that it killed 1.6 million native animals nationwide, including 3,893 coyotes,142 foxes, 83 black bears, 18 bobcats and thousands of other creatures in California. Nontarget animals — including protected wildlife like wolves, Pacific fisher and eagles — are also at risk from Wildlife Services’ indiscriminate methods.

“Killing native wildlife at the behest of the ranching industry is morally unconscionable and scientifically unsound,” said Erik Molvar of Western Watersheds Project. “Carnivores play an important ecological role, and exterminating them upsets the balance of nature. We should leave the wildlife alone and change ranching practices instead.”

“Wildlife Services is acting in clear violation of the law,” said Tara Zuardo, Animal Welfare Institute wildlife attorney. “The agency cannot be allowed to continue haphazardly and cruelly kill thousands of wild animals in Northern California each year without weighing more humane alternatives.”

The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) requires Wildlife Services to rigorously examine the environmental effects of killing wildlife and to consider alternatives that rely on proven nonlethal methods to avoid wildlife conflicts. But the wildlife-killing program’s environmental analysis for Northern California is more than 20 years old. According to the complaint filed today, Wildlife Services must use recent information to analyze the impacts of its wildlife-killing program on the environment and California’s unique wild places.

“NEPA requires that federal agencies use the best available science in analyzing the impacts of their programs, and we believe Wildlife Services has failed to do this and has in fact cherry-picked their science to meet their goals,” stated Camilla Fox, founder and executive director of Project Coyote. “Moreover, they must consider alternatives to indiscriminate killing and analyze the site-specific and cumulative impacts that killing large numbers of wild animals has on the diversity and integrity of healthy ecosystems.”

Today’s lawsuit is brought by the Center for Biological Diversity, Western Watersheds Project, the Animal Legal Defense Fund, Project Coyote, the Animal Welfare Institute and WildEarth Guardians. It targets Wildlife Services’ program in California’s North District, which includes Butte, Humboldt, Lassen, Mendocino, Modoc, Nevada, Plumas, Sierra, Shasta, Siskiyou, Sutter, Trinity and Yuba counties.