by DGR News Service | Jun 14, 2019 | Strategy & Analysis

Editor’s Note: Revolutionaries must study each revolutionary tradition and learn from it. We don’t believe that PPW is a “magic bullet” for current pre-revolutionary conditions, but it is worth studying.

By JP

Protracted People’s War (PPW) is a military theory developed by Mao Zedong during the Chinese Civil War and the war against the Japanese in China. What Mao puts forward is that a guerrilla movement must be able to maintain the support of the people for long enough to wage a long war against an enemy, hence protracted. Mao said also that by moving into the countryside, the people’s army could stretch the supply-lines of the enemy thin and break their will to fight. This is a very broad definition and we will go into a more detailed one later on. PPW has moved beyond being a military theory for a revolution in China since Mao conceived of it. It’s principles have been used in numerous countries from Vietnam and Cuba to India and the Philippines today. It has also become a fundamental tenet of the modern ideology of Marxism-Leninism-Maoism which proclaims its universality. There are also those who decry it as a theory solely for the conditions of China. Both of these claims are right and wrong in their own ways as they are both ideological arguments. They both ignore critical analysis of military theory and material conditions. One must remember that war is complex and different, especially in the context of revolutionary warfare. All military theories need to be analysed and adapted to material conditions or they cease to be effective. Warfare develops as fast as technology does and that sometimes makes it difficult to study. Keep this in mind.

What is Protracted People’s War?

As stated earlier, protracted people’s war is a theory of revolutionary warfare centred on the building up of popular support for a long and drawn out war against an enemy. It is, like most Marxist military theories, rooted in politics. That does not detract from it, however. In fact, it makes it a smarter theory in that it accounts for such things. Mao divided the protracted war into three basic stages:

- The Strategic Defensive

- The Strategic Stalemate

- The Strategic Offensive

During the strategic defensive, the army will go into the countryside with difficult terrain and establish revolutionary base areas. From these base areas, the army will carry out attacks on the enemy through guerilla means. This mostly includes attacking patrols, crippling supply lines, and destroying key military infrastructure. During this period the army also begins to gain strength from in and around the revolutionary base areas. Once enough strength is gained, the second stage can begin. In the strategic stalemate, the army begins to spread from its initial bases and establishes new ones. The army also begins to strategically engage the enemy in more conventional warfare. The assumption is that by this time the army is strong enough, and the enemy is weak enough to begin strategic confrontation on a larger scale. During this, the army gains a sizeable amount of territory but, the enemy does not lose much of value, hence a stalemate. Following another period of building strength, the army enters the third and final stage of the war; the strategic offensive. This is when the army goes into high gear against a weak and tired enemy. It first drives them out of the countryside and encircles the cities. From there is routs them and takes major population centres. It then proceeds to defeat the enemy obliterating the will of the enemy or destroying them. From there is victory for the army.

While it can be easy to describe this process in a relatively condensed manner, PPW is anything but short. It is a long and ruthless conflict. The amount of time an army spends in any of the stages depends on the conditions and ability of the army. Mao was aware of this and in his work “On Protracted War” (1938), gives a summation of the nature of protracted war:

“It is thus obvious that the war is protracted and consequently ruthless in nature. The enemy will not be able to gobble up the whole of China but will be able to occupy many places for a considerable time. China will not be able to oust the Japanese quickly, but the greater part of her territory will remain in her hands. Ultimately the enemy will lose and we will win, but we shall have a hard stretch of road to travel”.

PPW is a long-term affair and Mao developed many theories as to how each stage would be carried out, specific tactical objectives for each stage, and the discipline of the army as a whole. What ties these all together is the role of politics. PPW is not just a war against an enemy, but also a war for the hearts and spirits of the people. One of the key goals of the army in PPW is establishing a democratic order in the areas it occupies. In China, this was done via land reform and the establishment of peasant councils in the countryside. Political education is also a must of the army (PPW assumes the army has a political force behind it). Political education in the Chinese context was the promoting of Marxism-Leninism and anti-reactionary views among the Chinese people. Mao also was working with a united front against the Japanese and accounted for the politics of that situation into his theory. He maintained that only through the united front of anti-reactionary groups could the war succeed in its final victory. This was important because the main base that PPW relies on is popular support. Such a long conflict and process can only succeed if the people are on board and are able to unite. This is not just true of the army but of the nation as well. The people must be willing to live through struggle and destruction in order to obtain victory. In Mao’s case, he was right. The Chinese people persevered and won their victory; both against the Japanese and the Kuomintang. It was from this victory that people across the world would take inspiration.

PPW would be taken by others across the world and used to wage revolutionary conflicts. Although, none of them would be exactly the same; all would be similar situations. Vietnam and Cuba both took aspects of PPW but morphed them with more conventional tactics. For Vietnam specifically, Vo Nguyen Giap wrote a book titled “People’s Army, People’s War” which outlines much of the strategy used by the Viet Minh and Viet Cong. In Cuba aspects of PPW were fused with Foco Theory by Che Guevara. More Maoist oriented people’s wars would be carried out by guerrillas in Nepal, India, Peru, Turkey, and the Philippines. Of these Maoist-based PPWs, only Nepal was a complete success with the establishment of democracy in Nepal. The Shining Path in Peru failed due to their reliance on and cult of personality surrounding Abimael Guzman (Presidente Gonzalo). The failures of many people’s wars are due mainly to mistakes within guerrilla organisations and the will of the enemy to crush them. However, in India, Turkey, and the Philippines the conflicts are still ongoing so, it would be unfair to judge them. In all three of these, the groups have been progressive forces for revolutionary change against reactionary governments. The NPA in the Philippines is especially successful and constantly gaining support.

On the Universality of Protracted People’s War

One of the central tenets of Marxism-Leninism-Maoism is the universality of PPW, claiming that it can be applied everywhere and be successful. This claim is ideological and not driven by concrete analysis of material conditions or military theory in general. In military theory and Marxism in general, there is no universal plan that works 100% of the time. There are things that will probably work most of the time depending on the conditions. This is true of most methods. PPW works in places dominated by a non-urban population with military infrastructure based within population centres with minor bases outside of them to maintain a presence. In China and most places back in the 20th Century, this worked because that was how militaries operated. Today one would be hard pressed to find a military that operated in this way, even outside of the imperialist centres in the Third World. That is because governments have developed around the threat of insurgencies and accommodated themselves to them or in the case of countries like the United States, the military never operated that way.

While the argument can be made that PPW could work successfully in the Third World is legitimate (for now), the argument of complete universality falls apart when one looks at the United States or any other Western country. The United States runs the largest military in the world in terms of budget. This has led to a completely monstrous military with a large international presence. The US military is also political in that most soldiers are devoted volunteers, different from the forced conscripts of Chiang Kai-shek. Other aspects such as level of training and experience also do not look good when applying PPW to the United States. The one primary problem, however, is the way the military operates domestically. US military bases are everywhere in almost every state and region of the country. The only place they are not is where there are no people. Needless to say, the United States does not look ideal for the establishment of revolutionary base areas. One other key issue is that of technology. Modern armies are technologically equipped almost to the point where soldiers are not always necessary. Drones, missiles, aircraft, and explosives make modern warfare different from the warfare of the past century. Unless a people’s army could adapt to or obtain that technology, it is almost impossible to win.

Now those who support the argument of the complete universality of PPW have many responses to the situation of modern warfare. One of the most prevalent is the idea that the revolution will not start in the imperialist centres and that the effects of revolutions in the Third World on the economies of Western countries will weaken them, making revolution and PPW possible. This argument assumes too much and is too dependent on the success of Third World revolutions. Also, revolutionaries in the Third World would not just be fighting one enemy but, a multitude of enemies if there were any possibility of success. The US empire is global and can move on any threat to its hegemony or economic situation. While the best hope is in the Third World, one must not be so arrogant and confident in that all hopes lead to success. Another thing people often try to do is change PPW to fit modern conditions without actually doing a material analysis. One proposed change for PPW in the West is for it to stem from cities. This still suffers the same difficulties as regular PPW in that the army would still be subject to the same problems, just in a city. Cities are also easy to close off and prevent movement from if need be. This threatens the need for mobility in a guerrilla war. Not that urban guerrilla warfare cannot work, look at the IRA, but, urban PPW seems farfetched.

Finally, the largest argument often made in support of the complete universality of PPW is that if the people’s army maintains popular support, it cannot be defeated. This is correct depending on what they mean by never be defeated. Ideas and causes, such as that of the workers, can never be defeated by brute force. Armies can be defeated by brute force. An army can be completely routed and obliterated as long as their enemy has the will and the ability to do so. This strikes at the main problem with PPW; it assumes it cannot lose. It assumes that an army will always be unable to cope with the effects of guerrilla warfare. This is simply not true, especially today. People’s wars worked because of the enemy’s inability to cope with the conditions. The army made it so the enemy could not adapt easily and with the level of technology available then, it was much easier to do that. Today we have modern armies fully equipped with modern technology ready and willing to obliterate their enemies. The sheer size and protection given to military infrastructure today make it nearly impossible to sabotage the enemy to the level of weakness needed to wage an effective war. Also, people’s wars depended on the enemy not having the will and means to crush them. If there is an army with the will and means to snuff out an insurgency, it will and that is all it would take. If the enemy went to the base areas and drone struck them all, that is the end of the war. There is no assurance of victory in any military strategy or theory, all are subject to material conditions. People need to remember this.

Conclusion

This essay is not meant to be pessimistic or discouraging of revolutionary action, on the contrary, it is meant to try and get people to think more about how a revolution would be conducted in certain settings. This also is not meant to put down Protracted People’s War as a concept either. It is a genius concept and Mao is a genius for formulating it. People just need to accept that revolution is different everywhere and there is never a method that is always successful. All this being said, revolutionary tactics should not be the main focus in the present time. Much of the world still has a long way to go. That does not mean ignore them but, there are more pressing issues. Something key to PPW and any revolution is unity. Maybe start there.

Republished from https://redsuninthesky.com/ under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

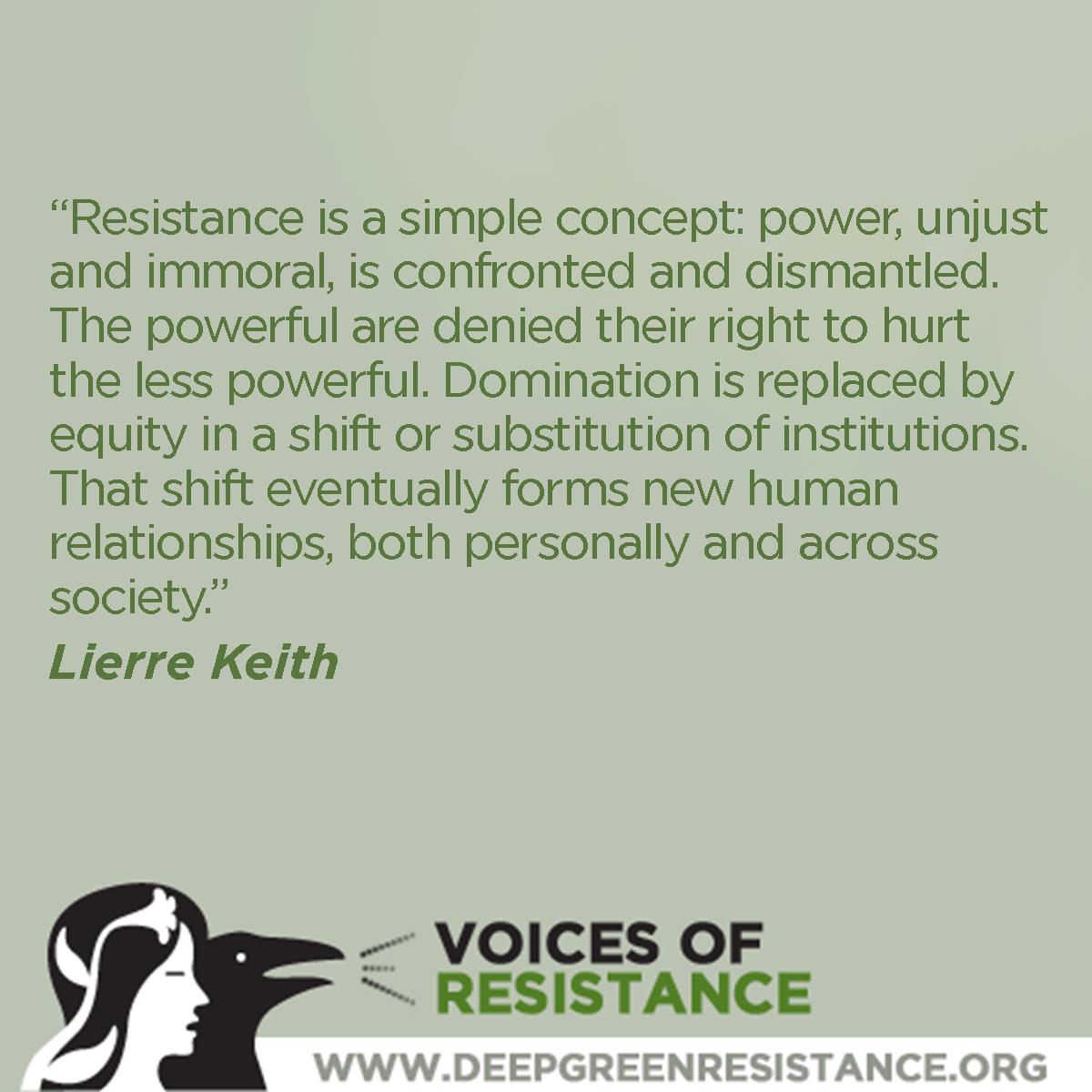

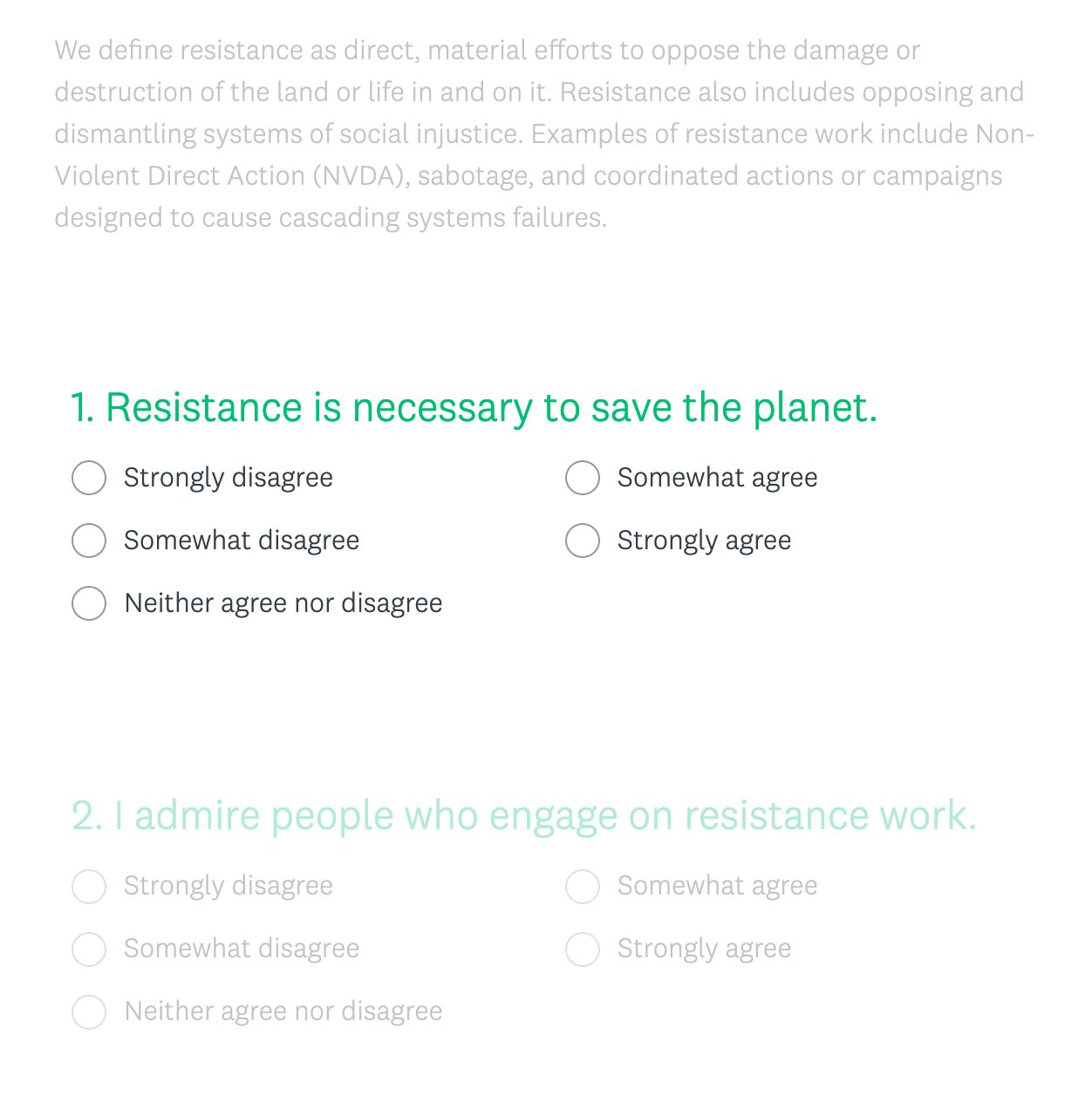

by DGR News Service | Jun 10, 2019 | The Solution: Resistance

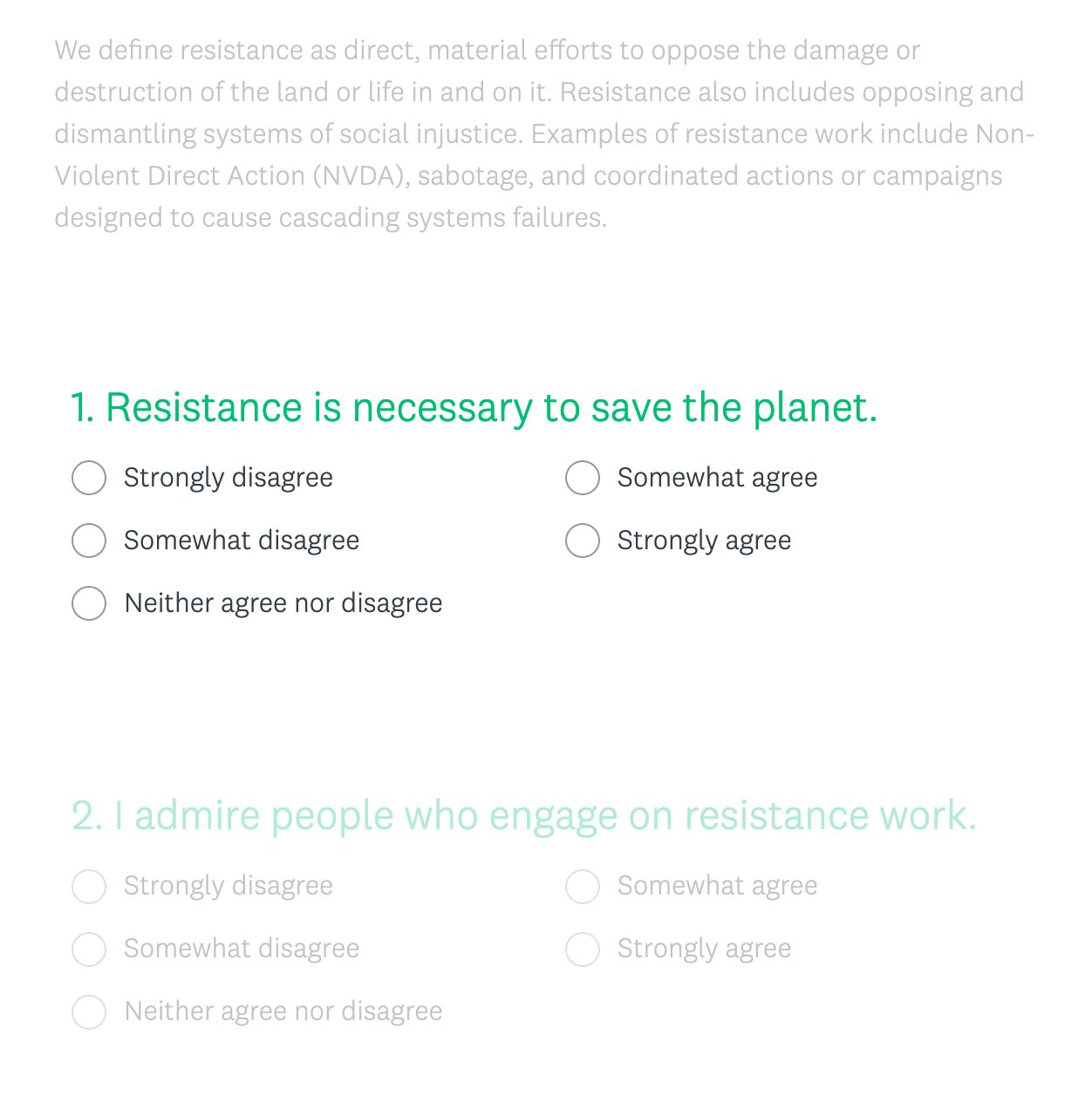

To effectively provide news, leadership, training, and more, we need to know more about our audience. With this goal, we are launching a survey asking our readers: how do you feel about resistance?

Filling out this survey will only take a few minutes of your time, but will provide us with valuable data to inform our work. All data is anonymous on our side. Thank you for your participation.

https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/CB22QC9

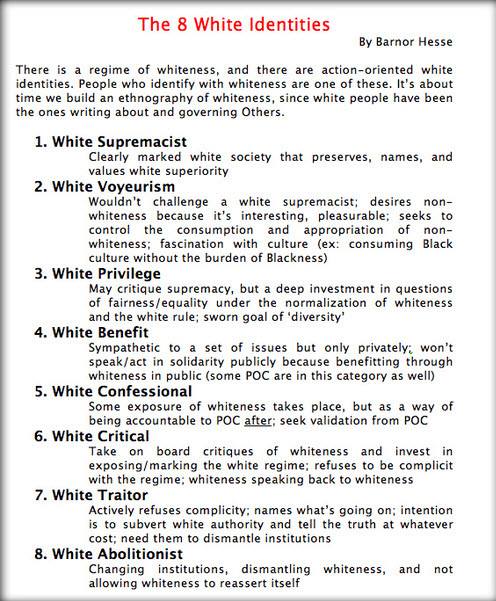

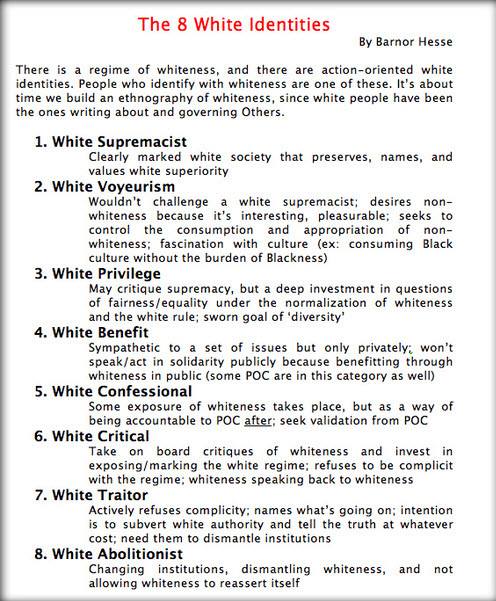

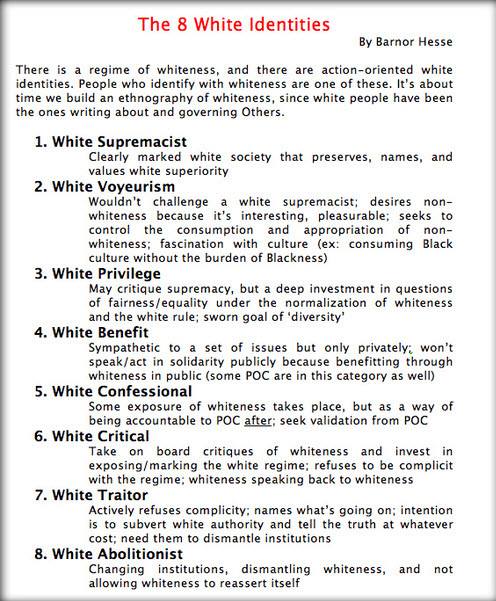

by DGR News Service | Jun 2, 2019 | The Solution: Resistance, White Supremacy

Developed by white Deep Green Resistance members, with guidance from the People of Color Caucus.

Introduction

White Supremacy is a system of power that is as active today as any time in this culture’s history. As white activists, we have been socialized into a culture of domination and often carry, practice, and reproduce racism in our own work. Racism is a threat to the health and continuation of all communities, including political ones. We therefore ask all white activists to commit themselves in every aspect of their lives, political or otherwise, to dismantling racism, personally and culturally. Communities of color alone cannot change white communities from the outside, nor is it their responsibility.

White Supremacy is a system of power that is as active today as any time in this culture’s history. As white activists, we have been socialized into a culture of domination and often carry, practice, and reproduce racism in our own work. Racism is a threat to the health and continuation of all communities, including political ones. We therefore ask all white activists to commit themselves in every aspect of their lives, political or otherwise, to dismantling racism, personally and culturally. Communities of color alone cannot change white communities from the outside, nor is it their responsibility.

As Stokely Carmichael said, “White people must start building those [anti-racist] institutions inside the white community, and that is the real question I think facing the white activists today: can they in fact begin to move into and tear down the institutions which have put us all in a trick-bag that we’ve been into for the last hundred years?” As allies to people and communities of color, this is our work. The following guidelines are to encourage white activists to eliminate racism from their behavior and language, and better ally themselves with people of color.

Guidelines

- We understand that, as white people raised in a white supremacist society, we are racists. It is impossible to work to end racism without acknowledging the deep-seated racism that is taught to us from a very young age. White activists need not feel guilty about this, but rather we should feel obligated to dismantle racism, both inside ourselves and externally.

- Among activists, racism doesn’t always show itself in outbursts of anger or violence; more often it is found in everyday language, interactions, and assumptions that ultimately silence and devalue people of color. Work to respect and listen to the voices and choices of people of color.

- Actively support, encourage, and respect the leadership of people of color.

- Offer support and assistance to activists working in communities of color. Acknowledge and respect the primary emergencies of these communities.

- Work to counter the efforts of white supremacist and fascist groups.

- Have the humility and courage to challenge oneself and learn from others about issues relating to race and white supremacy.

- Do not participate in or condone racist humor. Do not use derogatory labels based upon race. Do not speak in stereotyped racial dialects.

- Challenge racist behavior in your friends, family, associates, and political allies. When appropriate, end relationships with people who continue to encourage or practice racism.

- Discuss racism with young people in your life. Help them to identify and confront racism, become better allies to people of color, and engage in working towards the end of white supremacy.

- Commit to ongoing self-education on the history and theory of racial oppression. Do not speak as an authority on subjects that people of color directly experience and you do not. If you are to speak at all on such subjects, it should only be after people of color or if people of color ask you to do so.

- The power of white supremacy is maintained to a large degree by institutions (housing, education, criminal in-justice, banking, culture, media, extraction, and so on), rather than by individual racists. Our primary work to end racism goes beyond confronting particular racists; ultimately, it requires dismantling racist institutions and culture.

- Understand that when you choose to fight racism and imperialism, you are joining a protracted, centuries-old struggle which indigenous people and people of color have always been on the front lines of. As white people, we must allow those who have experienced these histories first hand to inform our resistance.

- The guidelines established above represent a baseline for acceptable behavior. Following them is not exceptional, and does not merit reward. Choosing to ignore racist behavior will be seen as an act of collaboration with the culture of white supremacy.

by DGR News Service | May 29, 2019 | The Solution: Resistance

Introduction

Building a successful culture of resistance to address modern environmental and social justice crises requires that we learn what has and hasn’t worked for other groups. The Resistance Profiles below provide an introduction, with references to further resources, to different approaches of many resistance group of the past and present, with a wide range of goals, strategies, tactics, ways of organizing and effectiveness.

To understand the difference between strategy and tactics, please read the Strategic Resistance excerpt from the Deep Green Resistance book. We’ve chosen the examples below for their illustrative and educational value. Inclusion of a group or campaign does not imply endorsement by Deep Green Resistance of their goals, strategies or tactics.

If you know of groups that we do not currently have a profile for, or want to suggest additional information or corrections for an existing profile, please email us at undergroundpromotion@deepgreenresistance.org

NOTE: We ONLY accept communications about groups or actions that are already publicly known. DO NOT send communiques directly to this email address. THIS IS NOT A SECURE MEANS OF COMMUNICATION. This is for the safety of all parties. This page is for RE-PUBLISHING information that is already in the public domain.

For news stories of recent attacks on infrastructure, visit our Underground Action Calendar.

by DGR News Service | May 25, 2019 | The Solution: Resistance

Appendix A of US Army FM 3-0, “Operations”, 2008 edition

The nine principles of war represent the most important nonphysical factors that affect the conduct of operations at the strategic, operational, and tactical levels. The Army published its original principles of war after World War I. In the following years, the Army adjusted the original principles modestly as they stood the tests of analysis, experimentation, and practice. The principles of war are not a checklist. While they are considered in all operations, they do not apply in the same way to every situation. Rather, they summarize characteristics of successful operations. Their greatest value lies in the education of the military professional. Applied to the study of past campaigns, major operations, battles, and engagements, the principles of war are powerful analysis tools. Joint doctrine adds three principles of operations to the traditional nine principles of war.

Objective

Direct every military operation toward a clearly defined, decisive, and attainable objective.

A-1. The principle of objective drives all military activity. At the operational and tactical levels, objective ensures all actions contribute to the higher commander’s end state. When undertaking any mission, commanders should clearly understand the expected outcome and its impact. Combat power is limited; commanders never have enough to address every aspect of the situation. Objectives allow commanders to focus combat power on the most important tasks. Clearly stated objectives also promote individual initiative. These objectives clarify what subordinates need to accomplish by emphasizing the outcome rather than the method. Commanders should avoid actions that do not contribute directly to achieving the objectives.

A-2. The purpose of military operations is to accomplish the military objectives that support achieving the conflict’s overall political goals. In offensive and defensive operations, this involves destroying the enemy and his will to fight. The objective of stability or civil support operations may be more difficult to define; nonetheless, it too must be clear from the beginning. Objectives must contribute to the operation’s purpose directly, quickly, and economically. Each tactical operation must contribute to achieving operational and strategic objectives.

A-3. Military leaders cannot dissociate objective from the related joint principles of restraint and legitimacy, particularly in stability operations. The amount of force used to obtain the objective must be prudent and appropriate to strategic aims. Means used to accomplish the military objective must not undermine the local population’s willing acceptance of a lawfully constituted government. Without restraint or legitimacy, support for military action deteriorates, and the objective becomes unobtainable.

Offensive

Seize, retain, and exploit the initiative.

A-4. As a principle of war, offensive is synonymous with initiative. The surest way to achieve decisive results is to seize, retain, and exploit the initiative. Seizing the initiative dictates the nature, scope, and tempo of an operation. Seizing the initiative compels an enemy to react. Commanders use initiative to impose their will on an enemy or adversary or to control a situation. Seizing, retaining, and exploiting the initiative are all essential to maintain the freedom of action necessary to achieve success and exploit vulnerabilities. It helps commanders respond effectively to rapidly changing situations and unexpected developments.

A-5. In combat operations, offensive action is the most effective and decisive way to achieve a clearly defined objective. Offensive operations are the means by which a military force seizes and holds the initiative while maintaining freedom of action and achieving decisive results. The importance of offensive action is fundamentally true across all levels of war. Defensive operations shape for offensive operations by economizing forces and creating conditions suitable for counterattacks.

Mass

Concentrate the effects of combat power at the decisive place and time.

A-6. Commanders mass the effects of combat power in time and space to achieve both destructive and constructive results. Massing in time applies the elements of combat power against multiple decisive points simultaneously. Massing in space concentrates the effects of combat power against a single decisive point. Both can overwhelm opponents or dominate a situation. Commanders select the method that best fits the circumstances. Massed effects overwhelm the entire enemy or adversary force before it can react effectively.

A-7. Army forces can mass lethal and nonlethal effects quickly and across large distances. This does not imply that they accomplish their missions with massed fires alone. Swift and fluid maneuver based on situational understanding complements fires. Often, this combination in a single operation accomplishes what formerly took an entire campaign.

A-8. In combat, commanders mass the effects of combat power against a combination of elements critical to the enemy force to shatter its coherence. Some effects may be concentrated and vulnerable to operations that mass in both time and space. Other effects may be spread throughout depth of the operational area, vulnerable only to massing effects in time.

A-9. Mass applies equally in operations characterized by civil support or stability. Massing in a stability or civil support operation includes providing the proper forces at the right time and place to alleviate suffering and provide security. Commanders determine priorities among the elements of full spectrum operations and allocate the majority of their available forces to the most important tasks. They focus combat power to produce significant results quickly in specific areas, sequentially if necessary, rather than dispersing capabilities across wide areas and accomplishing less.

Economy Of Force

Allocate minimum essential combat power to secondary efforts.

A-10. Economy of force is the reciprocal of mass. Commanders allocate only the minimum combat power necessary to shaping and sustaining operations so they can mass combat power for the decisive operation. This requires accepting prudent risk. Taking calculated risks is inherent in conflict. Commanders never leave any unit without a purpose. When the time comes to execute, all units should have tasks to perform.

Maneuver

Place the enemy in a disadvantageous position through the flexible application of combat power.

A-11. Maneuver concentrates and disperses combat power to keep the enemy at a disadvantage. It achieves results that would otherwise be more costly. Effective maneuver keeps enemy forces off balance by making them confront new problems and new dangers faster than they can counter them. Army forces gain and preserve freedom of action, reduce vulnerability, and exploit success through maneuver. Maneuver is more than just fire and movement. It includes the dynamic, flexible application of all the elements of combat power. It requires flexibility in thought, plans, and operations. In operations dominated by stability or civil support, commanders use maneuver to interpose Army forces between the population and threats to security and to concentrate capabilities through movement.

Unity Of Command

For every objective, ensure unity of effort under one responsible commander.

A-12. Applying a force’s full combat power requires unity of command. Unity of command means that a single commander directs and coordinates the actions of all forces toward a common objective. Cooperation may produce coordination, but giving a single commander the required authority is the most effective way to achieve unity of effort. A-13. The joint, interagency, intergovernmental, and multinational nature of unified action creates situations where the commander does not directly control all organizations in the operational area. In the absence of command authority, commanders cooperate, negotiate, and build consensus to achieve unity of effort.

Security

Never permit the enemy to acquire an unexpected advantage.

A-14. Security protects and preserves combat power. Security results from measures a command takes to protect itself from surprise, interference, sabotage, annoyance, and threat surveillance and reconnaissance. Military deception greatly enhances security.

Surprise

Strike the enemy at a time or place or in a manner for which he is unprepared.

A-15. Surprise is the reciprocal of security. It is a major contributor to achieving shock. It results from taking actions for which the enemy is unprepared. Surprise is a powerful but temporary combat multiplier. It is not essential to take enemy forces completely unaware; it is only necessary that they become aware too late to react effectively. Factors contributing to surprise include speed, operations security, and asymmetric capabilities.

Simplicity

Prepare clear, uncomplicated plans and clear, concise orders to ensure thorough understanding.

A-16. Plans and orders should be simple and direct. Simple plans and clear, concise orders reduce misunderstanding and confusion. The situation determines the degree of simplicity required. Simple plans executed on time are better than detailed plans executed late. Commanders at all levels weigh potential benefits of a complex concept of operations against the risk that subordinates will fail to understand or follow it. Orders use clearly defined terms and graphics. Doing this conveys specific instructions to subordinates with reduced chances for misinterpretation and confusion.

A-17. Multinational operations put a premium on simplicity. Differences in language, doctrine, and culture complicate them. Simple plans and orders minimize the confusion inherent in this complex environment. The same applies to operations involving interagency and nongovernmental organizations.

by DGR News Service | May 21, 2019 | Direct Action

Editor’s Note: This zine is an excellent read, and we encourage you to study it thoroughly. However, we’d also like to point out that the fossil fuel industry is not dying—it’s unfortunately very robust and growing. We say this only because our strategies must be based on realism, and our realism leads us past non-violent direct action to Decisive Ecological Warfare.

Intro to Swarm

The Earth is gasping for air and so are all the living beings on her. The tightest knots around our throats are black snakes, the pipe-lines that pulse out of the oil fields in Alberta carrying climate-killing carbon across land and water. The fights against these pipelines em-body a series of battles in the war for the future of life on this planet: The Tar Sands Blockade. Standing Rock. Unis’tot’en Camp. L’eau Est La Vie Camp. These are places we have made our stands against annihilation. But the battle goes beyond these camps. This is a fight for every one of our futures, and defeat is not an option.

Through hard fought struggle, we have forged and sharpened our tactics in order to adapt and win. This zine has been written and edited by a number of frontline veterans in the climate struggle, hoping to address new concepts around how we fight those who would drive us to extinction. Specifically, we wish to introduce the concept of swarming and the strategy of roving caravans, using the Mississippi Stand campaign as a case study.

Swarm tactics are the use of autonomously-acting cells on the battlefield, acting in coordination without a centralized or hierarchical command structure. This way of carrying out actions mimics swarms in nature, such as bees or piranhas. Humans have used swarm tactics for thousands of years, especially for guerrilla and insurgent forces facing better-funded occupying forces.

The mobile caravan tactic takes the analysis of the pipeline fight as an asymmetric, “guerrilla” struggle against an occupying force to its logical next step. Rather than relying solely on stationary camps set up to block a pipeline, the mobile caravan approach relies on disrupting production up and down the pipeline, stretching police and security forces thin and maximizing disruption.

We aim to bring these ideas into the consciousness of the broader movement for discussion, debate, and subsequent application in the field. This zine has been written in the context of the brewing Line 3 struggle across Ojibwe and Dakota lands and the watersheds of northern Minnesota. However, we believe that the lessons we explore here and the experiences we gain through struggle will find relevance well beyond this particular pipeline fight. We believe that if adopted, these tactics can significantly increase the effectiveness of our struggles against fossil fuel infrastructure.

Read the full zine here: https://conflictmnfiles.blackblogs.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/409/2019/04/Swarm-READ.pdf