by DGR News Service | Feb 15, 2019 | Strategy & Analysis

by John Steppling / Counterpunch

“Utilizing the power of celebrity (an unprecedented phenomenon for the expansion of capital in the west), today’s global influencers such as Thunberg, are fully utilized to create a sense of urgency in regard to the climate crisis. The unspoken reality is, they are the very marketing strategy to save capitalism. This is a very “inconvenient truth”.”

– Cory Morningstar & Forest Palmer

“And we will move forward to our work, not howling out regrets like slaves whipped to their burdens, but with gratitude for a task worthy of our strength, and thanksgiving to Almighty God that He has marked us as His chosen people, henceforth to lead in the regeneration of the world.”

– Albert T. Beveridge (Speech in the Senate. “Congressional Record”, Senate, 56th Congress, 1st session,1900)

“The old Lakota was wise. He knew that man’s heart away from nature becomes hard…”

– Luther Standing Bear

I want to try to tie together several societal and cultural trends that have been developing beneath the surface (or at least beneath the surface most of the time) for several years. One thing that the Trump presidency seems undeniably to embody is a kind of seismic shift into open fascism — a shift that is global in nature. This is not to suggest that Trump is anything other than a continuation of what came before, but that the very forces that brought the Donald to the Presidency have also made visible the tendencies toward fascism globally.

This is the age of marketing. Only that age began forty years ago, more or less, so this is now the age of hyper marketing or ultra marketing. And that all topics and concerns, literally everything, from education to policing to surveillance to nuclear disarmament, to green or ecological concerns, to politics (sic) to gender and race are all in service to further a total indoctrination of the populace (meaning mostly, but not exclusively the West) and a way to protect capital and solidify the power of the ruling elite. And perhaps it’s not exactly to protect Capital so much as to set the stage for a post capitalist new feudalism.

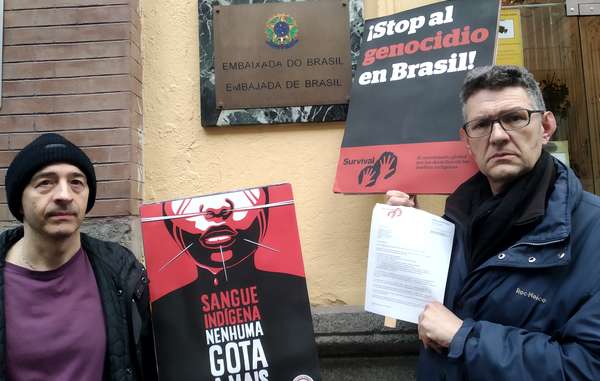

The global landscape now features in Brazil (5th most populous country on earth) a new openly fascist president in Jair Bolsonaro. This is a man who openly admires Hitler, and suggests he’d kill a son if he found out he was gay. Not to mention his adoration of Israel and bromance with Bibi Netanyahu. (contradiction you say?.. on the surface yes, but perhaps not if one examines all this more closely). Bolsonaro wants to sell off the rain forest, and has all but issued a mass death warrant to indigenous tribes and activists protesting the denuding of the Amazon basin. In India, the second most populous nation on earth, Modi has defined himself and his party the BJP as a nativist neo fascist authoritarianism.

“…while we don’t have a fascist nationalism which was in Germany, what we are witnessing is semi-fascist nationalism along religious sentiments. “

– Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd (The Hindu, June 2017)

In Hungary there is Victor Orban, and across Europe are a host of nativist ultra reactionary racist politicans; Geert Wilders in Holland, Matteo Salvini in Italy, or AfD political leader Alexander Gauland in Germany who dismissed Nazi era rule as mere “bird poo” in an otherwise spotless history of German triumph. Or Jimmy Akesson of the Swedish Democrats, or Jussi Hallo Aho of the Finns Party in Finland, or the crack pot religious fanatics of the Law and Justice party in Poland (close with Orban’s party) or, in some ways, the most pernicious of the new reactionary neo fascists is Kristian Thulesen Dahl, head of the Danish People’s Party, a svelte well tailored and hip new fascism growing in legitimacy in the formally tolerant Scandinavian country. Dahl, a Knight of the Danneborog, likes to call his party “an anti Muslim party”. Prime Minister Lars Løkke Rasmussen, from the ostensively center right Venstre Party (its not, its full on reactionary) is almost equal to Dahl in his xenophobia. The previous Prime Minister (Anders Fogh Rasmussen) left the post in 2009 to head up NATO. (!) A position that then was taken by former Norwegian PM Jens Stoltenberg (Labor Party). So here we have these supposedly liberal politicians eagerly rolling over and piddling themselves, on command, from the US joint chiefs.

Running beneath all of these “anti immigration” parties is a revanchist colonial mentality. And that’s the point. The corporate media provides cover by stressing that immigration is a ‘real’ concern. The very framing of this question is just another tactic in the rehabilitation of fascism. Never is any mention of made of *why* there is an immigration *problem*. And if an aside is voiced it never targets US.and NATO Imperialist wars but rather suggests this is a clash of civilizations thing, echoing the seemingly forever durable Samuel Huntington meme. The fact that all that post 9/11 anti Islamic mythology has been debunked matters not at all. It doesn’t matter because people in the West WANTED to believe it — it reinforced a fantasy that they had clutched to their psychic bosoms long ago. The infidel, the barbarian hordes, and the uncivilizable tribes that threaten that bastion of civilization, white Europe. None of the anti immigration parties now on the ascendent in Europe has voiced opposition to US and NATO military affairs. Victor Orban (Fidesz Party) is rapidly coming to seem Europe’s answer to Donald Trump, or perhaps the new Berlusconi.

90% of all newspapers and media in Hungary is owned by Fidesz party loyalists. And Orban has drastically rewritten the constitution to allow himself enlarged powers. Not for no reason has Steve Bannon called Orban the most exciting politician in Europe. Also note, the Fidesz Party began as an anti-Communist youth group.

But the point is that those lurid drawings of the caves in Tora Bora or videos of dogs being gassed…as practice….or the yellow cake in Niger…were lapped up like milk in the U.S. The photos of Abu Ghraib came and went.

In the U.S. there is now a shifting away from the acute individualism of the ‘snowflake’ privileged and a reforming in the guise of a nostalgia laden colonialist or slave owner. And if you think that an exaggeration then just remember Bill Maher’s tirade last week where he referred very approvingly to the Monroe Doctrine and mentioned Venezuela as part of “our back yard”. I mean it is stunning, it really is. The new colonial is replicated in another guise by the Israeli military. As I have noted before the IDF no longer bothers much with the ‘most moral army in the world’ argument and just cuts straight to hyper efficient killing machine and overlords of their region. They are applauded as such, too.

In my anecdotal experience the last few weeks I have had countess social media interactions in which my interlocatur was young(ish) white and reasonably well off financially. And two things have emerged as through lines: one was an indelible and core racism. Especially anti black racism, and a clear tendency toward antisemitism. And second, a refusal to surrender privilege. The white privilege is more protected than ever, psychologically. And with that comes an outright refusal to criticize US policy — unless it is viewed as Trump’s policy. And often these two things are buried. They are deeply entrenched, though. I would wager that a vast majority of white america is unmoved by the achievements of the Innocence Project. Freeing black men is simply not something white people can get behind. But it is also the return of the mid 20th century hagiographic adoration of cowboys, the frontier, and rugged individualism. And with hunting. Now there is also a growing anger. I mean people are losing their lives. Families live under freeway overpasses. There are no jobs. And a new desperation is gripping the nation.

So intersecting then, are this new material desperation and a nostalgic self definition that includes Billy the Kid and Wyatt Earp, as well as an open embrace of teen symbolism and a kitsch nostalgia for the past as created by Hollywood — 70s styles, or 80s styles, etc. Anything but the present. For there is no style to the present. There is only escape from it. And the ruling elite are not unaware of all this either. Both major parties have the same identical goals. Both protect their privilege and both strategise ways or campaigns to capitalize on the discontent they see around them. (Enter Alexandria Ocasio Cortez. And not to beat this drum again, but the woman is a cretin. The examples are countless. But she remains telegenic and so desperate are people, liberals, to find a new standard bearer, that her gaffes are simply ignored.). The marketing of new candidates meant to suggest “change” is less effective than it was for Obama in his initial run. But it still works. But something else is behind all this. And that is touched on most acutely and brilliantly by Cory Moorningstar in her exhaustive 4 part series The Wrong Kind of Green.

And this is really, for me, something that has been nagging at me during those insomnia hours before dawn. Nagged at me while taking long walks ….and that is how the Ecological and Environmental Crisis is being marketed. And from that, how to process or trust the various conflicting alarms that are a constant now. And for many on the left to even say this much is dangerous. When I wrote that piece on Green Shaming I had started to touch on the outer husk of this, but Cory Morningstar and Forest Palmer did simply extraordinary work in researching the mechanisms of exploitation involved in the construction of a new grammar and style for this false Green awareness. The environmental crisis, all too real, is viewed as just another business opportunity. Only its more than that, too.

Now when I say its an age of hyper marketing, it is useful to really remember that almost everyone who is visible in media is being handled. Or “handled”. Everyone. EVERYONE. And nothing is ever what it seems, if it is visible to the mass public. It is an age in which the very idea of trust has been so eroded as to be almost anachronistic.

Fifty years ago Adorno warned of empty activism. And today that warning has migrated to green actions. It is worth bring in Venezuela here, as another kind of example. Max Blumenthal wrote in an exhaustive piece on Juan Guaido, that…

” While Guaidó seemed to have materialized out of nowhere, he was, in fact, the product of more than a decade of assiduous grooming by the US government’s elite regime change factories. Alongside a cadre of right-wing student activists, Guaidó was cultivated to undermine Venezuela’s socialist-oriented government, destabilize the country, and one day seize power. Though he has been a minor figure in Venezuelan politics, he had spent years quietly demonstrating his worthiness in Washington’s halls of power.”

– Max Blumenthal (Grayzone, Jan 29, 2019)

He was manufactured, much as Goldman Sachs and the IMF and other establishment banking entities manufactured Macron. In fact, its the way, on a larger denser and more complex level, Barak Obama was manufactured. Its the same structural composite that results in the marketing of Pussy Riot or pick any of a half dozen (at least) child victims of US/NATO wars. In fact much of the persuasion of public opinion comes out of invented narratives that either are starkly revisionist or simply never happened. Jessica Lynch was a branch of how that works. But the US and UK (in fact this is something of a UK specialty) produce just oodles of eye witnesses or “real” Syrians, or Libyans or Haitians or Iraqis or Venezuelans. Much as at one time the manufacturing of eye witnesses to Milosevic’s cruelty were all over the place. And the fact that nearly always these fake “authentic” voices cant keep their stories or facts straight doesnt matter –for exactly the same reason it didn’t matter OBL wasn’t in those Tora Bora caves, the ones that didn’t exist.

This brings me back to the Cory Morningstar & Forest Palmer in depth article. The link is here.

But one of the key targets for Western green business has been the global south, and in particular Africa. Not surprising that the US military also “pivoted” to Africa (sic) under Obama.

“Gore, with a net worth of approx. 350 million dollars, pays much lip service to subjects of inequality, wealth disparity and poverty. Thus, it is useful to actually take a look at what the much hyped green energy revolution actually looks like, when played out in real life and exactly who is being served by the so-called “green revolution”. M-Kopa Solar – “Power for Everyone” is a pay-per-use solar power provider (in the form of solar kits) created for impoverished African countries by white uber rich capitalists. The countries thus far include rural Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda. M-Kopa is the brainchild of Jesse Moore (CEO), Chad Larson and Nick Hughes —who helped develop M-Pesa, which has more than 19 million users in Kenya. { } Included on the M-Kopa board of advisors is Colin Le Duc, a founding partner of Generation Investment Management and the Co-CIO of Generation’s growth equity Climate Solutions Funds. Other investors/lenders/partners include Shell Foundation and Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. At this juncture, before we continue, it is vital to note that in 2015, M-Kopa estimated that eighty percent of its customers lived on less than $2 (USD) per day. By 2015, M-Kopa had reached over $40 million of revenue.”

Naomi Wolf wrote not too long ago..“When citizens can’t tell real news from fake, they give up their demands for accountability bit by bit.” But I think that is, actually, almost too optimistic. People want to believe mythologies that sanctify their own privilege. And this identity based thought structure, one dimensional by its very nature, then promotes what amounts to a 21st century kitsch mythos. Or as Margaret Rosler said, “people want the fake”.

I am suggesting, in short form, that history matters. And it matters on several levels. Which is why it is being erased. This was a slave owning country in which 12 presidents owned and worked slaves. It was built by slaves and by indentured Chinese workers and it produced Manifest Destiny, a belief in American territorial expansion regardless of the cost. It was at least party driven by Christian zealotry, and partly by greed. But also by a violence and cruelty which seems to have been the fusion of a variety of factors both historical and cultural. The public wants to find stories that flatter them and provide some, however fleeting, sense of their own significance and power. No country on earth produces men as insecure as the United States. And today, amid the waste of a destroyed union culture, and dead manfacturing base and loss of steel and auto makers…the U.S. worker is forced further and further into a fantasy laden infantilism. This is the world of that goes to celebrate the life of sniper Chris Kyle, an unbalanced borderline sociopath and serial liar, at the Houston Astro Dome. This is much of the culture of the flyover states. It is racist at its core, it is aggressive, driven on by deep lacerating insecurities, and it is despises and distrusts intellect and education. The other large group is the city dwelling white liberal, college educated, and today, confused, alienated, suffering serious fertility failures and increasingly medicated with psychotropic drugs and anti depressants. This is the much of the target audience for new green marketers.

One might think that if someone were conscious enough to recognise that global ecology was compromised and that pollutants were destroying fresh water, and the land, and that global warming was quite possibly going to make huge swatches of land non arable — you might think that person would look for solutions in a political frame. After all it was global capital that had brought mankind to this historic precipice. But instead, many if not nearly all the people I speak with, frame things in terms of personal responsibility. Stop driving big diesel SUVs, stop flying to Cabo for vacation, stop eating meat, etc-. But these same people tend to not criticize capitalism. Or, rather, they ask for a small non crony green capitalism. I guess this would mean green exploitation and green wars? For war is the engine of global capitalism today. Cutting across this are the various threads of the overpopulation theme. A convenient ideological adjustment that shifts blame to the poorest inhabitants of the planet. And here you find Bill Gates and other NGOs working to “help” the developing (sic) nations through population control (see Depa Provera and other reproductive health services).

Jacob Levich writes…“The Rockefeller Foundation organized the Population Council in 1953, predicting a “Malthusian crisis” in the developing world and financing extensive experiments in population control. These interventions were enthusiastically embraced by US government policymakers, who agreed that “the demographic problems of the developing countries, especially in areas of non-Western culture, make these nations more vulnerable to Communism.” (Aspects of India’s Economy, No 57 2014)

And this raises yet another question. The wrong kind of green, to put it in Morningstar’s term, is one that is all about the protection of capitalism. Green anti communism. There are links here between AVAAZ, and Otpor, and the USAID and National Endowment for Democracy and Freedom House et al. The world of NGOs has grown in both size and power.

“…the evil empire Buffett, Gates and Rockefeller built in the private sector is mirrored in the evil networks of NGOs they — along with Clinton — have constructed to provide cover for widespread environmental devastation, ethnic cleansing and Indigenous genocide committed by their corporate investments. Using bagmen like Tides Foundation in cahoots with magicians like Bill McKibben at 350 dot org, and sleight-of-hand artists like Tzeporah Berman at Tar Sands Solutions Network, Buffett, Gates, Rockefeller and Clinton have become thick as thieves in producing political theatre to distract us from the parade of refugees in their caravan of doom.”

– Jay Taber (Wrong Kind of Green, Oct 2013)

“Hollywood acts as an arm to this media intoxication when it comes to the military. Watch virtually any action, sci-fi or suspense movie these days and notice how militarism is seamlessly laced through most of the plot lines. Military hardware is easily available for these productions. Soldiers are almost always cast as virtuous. And this also demonstrates the strain of pernicious authoritarianism within American culture. FBI and CIA agents, detectives, prosecutors, all of them are portrayed with an air of troubled, perhaps flawed, but intact unassailable nobility.”

– Kenn Orphan (Counterpunch, 2019)

There has been a rightward shift in nearly every field one can find or think of. Recently in Norway I read this…

“A majority in Parliament asked the government in 2015 to replace its appeals court jury system with a combination of professional and lay judges. Now the historic reform has taken shape, reports newspaper Aftenposten. Instead of having a 10-member jury decide on guilt or innocence in Norway’s most serious criminal cases, they’ll now be heard in Norwegian appeals courts by two professional judges and five lay judges chosen from the public. The reform changes the way cases have been decided for 130 years.”

– News in English Norway, Aftenposten

In other words, this is a shift toward a bias for conviction. Two judges will simply determine the case and manipulate or bully if need be, the citizen jurors. The change was made because juries were increasingly found to be unable to follow the complexity of many cases. Lay another gold star on the destruction of public education in Europe and North America.

The racism of most Americans can be tracked, too, in how they digest mainstream propaganda about Venezuela. Many feel kinship with Maher’s position. This is OUR backyard. How dare that uppity “dead communist dictator”(to use Bernie Sanders description) Chavez deign to GIVE us free heating fuel and gas. The presumption. For many this was like the help talking back. Americans by and large are quite indifferent to the accuracy or not of the demonizing of official US enemies. From Castro to Milosevic to Aristide to Assad and Qadaffi …to the DPRK or Mao or Hugo Chavez. As the national front used to say in England…’the wogs start at Calais’. For white America there is always a residual racism and Puritanism at work in their thinking.

Also, one sees the confusion in anti nuke protests. Dennis Riches has done great work in compiling info and arguing the case. He wrote…

“If this recent anti-nuclear drive actually succeeded in getting the nuclear powers to ratify an international treaty declaring nuclear weapons illegal, the world would be left with the United States undeterred with a vastly predominant power in conventional weaponry. Intercontinental ballistic missiles would be refitted with precision conventional bombs capable of putting any nation on earth back in the Stone Age within a matter of weeks. This was already achieved with the attacks in attacks on Serbia (1999), Iraq (1991, 2003~) and Libya (2011). All of these were illegal under international law, which raises the question of how the international community would enforce compliance with a new international law banning nuclear weapons. In addition to the fact that international law is ignored continually during so-called peacetime, Russell and Einstein pointed out in their 1955 manifesto that treaties banning nuclear weapons would be abrogated the minute world war breaks.”

– Dennis Riches (Lit by Imagination, a blog of Dennis Riches)

In other words, nuclear disarmament is seen through the lens of American exceptionalism. Nothing happens in a vacuum.

“Secondly, insofar as it breeds in itself tendencies which— and here too we must differ—directly converge with fascism. I name as symptomatic of this the technique of calling for a discussion, only to then make one impossible; the barbaric inhumanity of a mode of behaviour that is regressive and even confuses regression with revolution; the blind primacy of action; the formalism which is indifferent to the content and shape of that against which one revolts, namely our theory. Here in Frankfurt, and certainly in Berlin as well, the word ‘professor’ is used condescendingly to dismiss people, or as they so nicely put it ‘to put them down’, just as the Nazis used the word Jew in their day. “

– Adorno (Letter to Marcuse, 1969)

Adorno was wrong in much of what he did in that later period (calling in the cops for one). But there is a seed of truth in his complaint, too (the Ocasio Cortez phenomenon is evidence of this, I’d say). Much of today’s green left seems profoundly uncritical of the US state department apparatus for propaganda and its infiltration (or creation) of NGOs and activists groups. Or just the predatory capitalists of Al Gore’s Generation Investment…

“At this juncture, seeing as we are being led to believe that “sustainable investments” are the pathway to solving our planetary crisis, it might be wise to ask in what sustainable corporations Generation Investment is investing. Generation Investment has created a focus list of some 125 companies around the world in which it invests not based on how sustainable the business is, but rather, “on the quality of their business and management.”

Generation Investment’s portfolio and investments include multinational corporations with horrendous records of malfeasance, such as Amazon, Nike, Colgate, MasterCard, and the Chipotle, restaurant chain, with heavy investments in health and technology. And as all of these corporations are heavily invested and/or dependent on fossil fuels, how an investment firm can justify investing in these companies is anyone’s guess. { } Generation Investment board members include eco-luminaries such as Mary Robinson, a former president of Ireland and the founder of nonprofit Mary Robinson Foundation. Robinson serves as president to Richard Branson’s B Team, which is managed by Purpose – the public relations arm of Avaaz.”

– Cory Morningstar (The Wrong Kind of Green)

The problem with discussions of global warming and the destruction of the planet is that so much of that discussion has been coopted by Capital. And its often very difficult to quickly know who to trust. One response I get a lot is, well, YOU have to change. This I take it means doing all kinds of feel good greeny things. And yet none of what I can do is going to matter to Bolsonaro as he burns down the Amazon. For that is political. And he is a fascist. And when Bernie Sanders and Ocasio Cortez, or Elizabeth Warren or Kamala Harris sign off on the coup in Venezuela, this is not and cannot be separated from the occupation of Afghanistan or the slaughter in Yemen, or mass incarceration and a violent militarized domestic police. The deep colonial Orientalism of American culture is tied to how one must start to talk about the environment. They are not separate issues. Sanders, besides slandering Maduro and the Bolivarian Revolution, also trashes the BDS movement. What is one to make of this, excatly? And yet his popularity stays in tact.

Any green change starts with the overthrow of capital. And that means that it rejects all military activity by the U.S. and NATO. Global warming drove the apocalyptic California wild fires last summer. But thirty or forty years of urban building, of the wrong shrubbery being planted, and crowded subdivisions intensified the fires. And, the practices of fire prevention.. paradoxically made those fires much worse.

“Building in or near fire-prone forests has also led to fire prevention land management practices that paradoxically increase fire risk. For instance, policies for preventing wildfires have in some areas led to an accumulation of the dry vegetation that would ordinarily burn away in smaller natural blazes. “The thing that gets missed in all of this is that fires are a natural part of many of these systems,” said Matthew Hurteau, an associate professor at the University of New Mexico studying climate impacts on forests. “We have suppressed fires for decades actively. That’s caused larger fires.”

– Umair Irfan (Vox, Dec 2017)

The frame is not to protect nature but to protect property, and that leads to problems.

The short equation then is this: if its a business opportunity, its not going to help anything. And if you find yourself on the same page as the US state department and Pentagon you might have to step back and take a breath. The supreme irony is Democrats in particular, who continue to drive the Russia-gate story, having no problem with getting rid of Maduro and replacing him with — for the moment — Juan Guaido. But the real purpose behind the attack on Venezuela is to get rid of socialism in ‘our back yard’. Getting massive oil reserves is nice bonus but the priority is to turn back the so called Pink Tide. Much as Yugoslavia had to go, so does Venezuela. With Bolsonaro, and Macri in Argentina, and Ivan Duque in Colombia, the forces of reaction are being put in place. (It is worth noting that while Trump’s cabinet is stocked with Domionists, the Supreme Court has had a heavy influence of Opus Dei members and that in Brazil Opus Dei rules the third largest bank…fascism and religion are always intwined). And for white America, this feels almost nostalgic. Adding Elliot Abrams to the mix only heightens that nostalgic feeling. For this suddenly feels like Reagan’s America again. Cowboys and the frontier — and the shining light on the hill. Only now, it all takes place, this kitsch B western, in the shadow of global ecological crises. Crises caused by Capital. By Wall Street and an elite class of 2% that owns more than the bottom 50% of the planet. By a system of exploitation in which human suffering is a foundational component. Its just like Reagan’s Norman Rockwell fantasy, except now with an all child cast. The political spectacle is now narrated by ten year olds. Bana Al-Abed is only the latest in this line of manufactured wag the dog props for the Western spin machine. The White Helmets are another branch of the fake. Absolutely invented, only in their case of a particularly grave robber morbidity. The aforementioned Pussy Riot, and AOC is in a sense another version of this. Young lithe and almost (!) childlike. Certainly not fecund and maternal. For that is a threat. Americans see the world as a Hollywood period film. Bring back the Casinos in Havana, that’s so romantic. Same as the Romanoff balls were romantic. Same as colonial salons from Calcutta to Singapore were romantic. An afternoon tea on the verandah at the Raffles Hotel, now those were the days. Nostalgia is a safe psychic retreat now. Even if its all make believe. In fact, there is a strange psychic disposition that desires the fake. That wants the artificial. I think it is perhaps fake is associated with fantasy, with the world as if it is a children’s book.

American’s idea of politics is also shaped in large measure by Aaron Sorkin’s West Wing. This is probably not even a tiny exaggeration. This is the vision and fantasy of the educated liberal class in America. But for all their self described tolerance and progressiveness, they will still vote for those Democrats who want a coup in Venezuela and who signed off on all of Trump’s defense spending increases. For the bourgeoisie always side with fascism. That’s simply a fact. In the end they will side with the authoritarian and far right wing, and protect their small corner of the sandbox. And even if one tries to explain that sandbox may well become a sweatshop — they seem undeterred. In the end the liberal press will embrace Bolsonaro, too. As they now do Bush Jr, and well, Elliott Abrams. Negroponte can’t be far behind. The plan is clearly to rehabilitate fascism. Globally. The School of the Americas are due a feature film, no doubt.

John Steppling is an original founding member of the Padua Hills Playwrights Festival, a two-time NEA recipient, Rockefeller Fellow in theatre, and PEN-West winner for playwriting. Plays produced in LA, NYC, SF, Louisville, and at universities across the US, as well in Warsaw, Lodz, Paris, London and Krakow. Taught screenwriting and curated the cinematheque for five years at the Polish National Film School in Lodz, Poland. A collection of plays, Sea of Cortez & Other Plays was published in 1999, and his book on aesthetics, Aesthetic Resistance and Dis-Interest was published by Mimesis International in 2016.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 27, 2019 | Strategy & Analysis

Featured image: The successful Sobibór uprising, 1943. Prisoners at the Nazi Sobibór extermination camp in Poland revolted against the Germans. About 300 of the camp’s 600 prisoners escaped, and about 50 of these survived the war.

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Decisive Ecological Warfare” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

There is one final argument that resisters in this scenario made for actions against the economy as a whole, rather than engaging in piecemeal or tentative actions: the element of surprise. They recognized that sporadic sabotage would sacrifice the element of surprise and allow their enemy to regroup and develop ways of coping with future actions. They recognized that sometimes those methods of coping would be desirable for the resistance (for example, a shift toward less intensive local supplies of energy) and sometimes they would be undesirable (for example, deployment of rapid repair teams, aerial monitoring by remotely piloted drones, martial law, etc.). Resisters recognized that they could compensate for exposing some of their tactics by carrying out a series of decisive surprise operations within a larger progressive struggle.

On the other hand, in this scenario resisters understand that DEW depended on relatively simple “appropriate technology” tactics (both aboveground and underground). It depended on small groups and was relatively simple rather than complex. There was not a lot of secret tactical information to give away. In fact, escalating actions with straightforward tactics were beneficial to their resistance movement. Analyst John Robb has discussed this point while studying insurgencies in countries like Iraq. Most insurgent tactics are not very complex, but resistance groups can continually learn from the examples, successes, and failures of other groups in the “bazaar” of insurgency. Decentralized cells are able to see the successes of cells they have no direct communication with, and because the tactics are relatively simple, they can quickly mimic successful tactics and adapt them to their own resources and circumstances. In this way, successful tactics rapidly proliferate to new groups even with minimal underground communication.

Hypothetical historians looking back might note another potential shortcoming of DEW: that it required perhaps too many people involved in risky tactics, and that resistance organizations lacked the numbers and logistical persistence required for prolonged struggle. That was a valid concern, and was dealt with proactively by developing effective support networks early on. Of course, other suggested strategies—such as a mass movement of any kind—required far more people and far larger support networks engaging in resistance. Many underground networks operated on a small budget, and although they required more specialized equipment, they generally required far fewer resources than mass movements.

Continuing this scenario a bit further, historians asked: how well did Decisive Ecological Warfare rate on the checklist of strategic criteria we provided at the end of the Introduction to Strategy.

Objective: This strategy had a clear, well-defined, and attainable objective.

Feasibility: This strategy had a clear A to B path from the then-current context to the desired objective, as well as contingencies to deal with setbacks and upsets. Many believed it was a more coherent and feasible strategy than any other they’d seen proposed to deal with these problems.

Resource Limitations: How many people are required for a serious and successful resistance movement? Can we get a ballpark number from historical resistance movements and insurgencies of all kinds?

- The French Resistance. Success indeterminate. As we noted in the “The Psychology of Resistance” chapter: The French Resistance at most comprised perhaps 1 percent of the adult population, or about 200,000 people.26 The postwar French government officially recognized 220,000 people27 (though one historian estimates that the number of active resisters could have been as many as 400,00028). In addition to active resisters, there were perhaps another 300,000 with substantial involvement.29 If you include all of those people who were willing to take the risk of reading the underground newspapers, the pool of sympathizers grows to about 10 percent of the adult population, or two million people.30 The total population of France in 1940 was about forty-two million, so recognized resisters made up one out of every 200 people.

- The Irish Republican Army. Successful. At the peak of Irish resistance to British rule, the Irish War of Independence (which built on 700 years of resistance culture), the IRA had about 100,000 members (or just over 2 percent of the population of 4.5 million), about 15,000 of whom participated in the guerrilla war, and 3,000 of whom were fighters at any one time. Some of the most critical and decisive militants were in the “Twelve Disciples,” a tiny number of people who swung the course of the war. The population of occupying England at the time was about twenty-five million, with another 7.5 million in Scotland and Wales. So the IRA membership comprised one out of every forty Irish people, and one out of every 365 people in the UK. Collins’s Twelve Disciples were one out of 300,000 in the Irish population.31

- The antioccupation Iraqi insurgency. Indeterminate success. How many insurgents are operating in Iraq? Estimates vary widely and are often politically motivated, either to make the occupation seem successful or to justify further military crackdowns, and so on. US military estimates circa 2006 claim 8,000–20,000 people.31 Iraqi intelligence estimates are higher. The total population is thirty-one million, with a land area about 438,000 square kilometers. If there are 20,000 insurgents, then that is one insurgent for every 1,550 people.

- The African National Congress. Successful. How many ANC members were there? Circa 1979, the “formal political underground” consisted of 300 to 500 individuals, mostly in larger urban centers.33 The South African population was about twenty-eight million at the time, but census data for the period is notoriously unreliable due to noncooperation. That means the number of formal underground ANC members in 1979 was one out of every 56,000.

- The Weather Underground. Unsuccessful. Several hundred initially, gradually dwindling over time. In 1970 the US population was 179 million, so they were literally one in a million.

- The Black Panthers. Indeterminate success. Peak membership was in late 1960s with over 2,000 members in multiple cities.34 That’s about one in 100,000.

- North Vietnamese Communist alliance during Second Indochina War. Successful. Strength of about half a million in 1968, versus 1.2 million anti-Communist soldiers. One figure puts the size of the Vietcong army in 1964 at 1 million.35 It’s difficult to get a clear figure for total of combatants and noncombatants because of the widespread logistical support in many areas. Population in late 1960s was around forty million (both North and South), so in 1968, about one of every eighty Vietnamese people was fighting for the Communists.

- Spanish Revolutionaries in the Spanish Civil War. Both successful and unsuccessful. The National Confederation of Labor (CNT) in Spain had a membership of about three million at its height. A major driving force within the CNT was the anarchist FAI, a loose alliance of militant affinity groups. The Iberian Anarchist Federation (FAI) had a membership of perhaps 5,000 to 30,000 just prior to revolution, a number which increased significantly with the onset of war. The CNT and FAI were successful in bringing about a revolution in part of Spain, but were later defeated on a national scale by the Fascists. The Spanish population was about 26 million. So about one in nine Spaniards were CNT members, and (assuming the higher figure) about one in 870 Spaniards was FAI members.

- Poll tax resistance against Margaret Thatcher circa 1990. Successful. About fourteen million people were mobilized. In a population of about fifty-seven million, that’s about one in four (although most of those people participated mostly by refusing to pay a new tax).

- British suffragists. Successful. It’s hard to find absolute numbers for all suffragists. However, there were about 600 nonmilitant women’s suffrage societies. There were also militants, of whom over a thousand went to jail. The militants made all suffrage groups—even the nonmilitant ones—swell in numbers. Based on the British population at the time, the militants were perhaps one in 15,000 women, and there was a nonmilitant suffrage society for every 25,000 women.36

- Sobibór uprising. Successful. Less than a dozen core organizers and conspirators. Majority of people broke out of the camp and the camp was shut down. Up to that point perhaps a quarter of a million people had been killed at the camp. The core organizers made up perhaps one in sixty of the Jewish occupants of the camp at the time, and perhaps one in 25,000 of those who had passed through the camp on the way to their deaths.

It’s clear that a small group of intelligent, dedicated, and daring people can be extremely effective, even if they only number one in 1,000, or one in 10,000, or even one in 100,000. But they are effective in large part through an ability to mobilize larger forces, whether those forces are social movements (perhaps through noncooperation campaigns like the poll tax) or industrial bottlenecks.

Furthermore, it’s clear that if that core group can be maintained, it’s possible for it to eventually enlarge itself and become victorious.

All that said, future historians discussing this scenario will comment that DEW was designed to make maximum use of small numbers, rather than assuming that large numbers of people would materialize for timely action. If more people had been available, the strategy would have become even more effective. Furthermore, they might comment that this strategy attempted to mobilize people from a wide variety of backgrounds in ways that were feasible for them; it didn’t rely solely on militancy (which would have excluded large numbers of people) or on symbolic approaches (which would have provoked cynicism through failure).

Tactics: The tactics required for DEW were relatively simple and accessible, and many of them were low risk. They were appropriate to the scale and seriousness of the objective and the problem. Before the beginnings of DEW, the required tactics were not being implemented because of a lack of overall strategy and of organizational development both above- and underground. However, that strategy and organization were not technically difficult to develop—the main obstacles were ideological.

Risk: In evaluating risk, members of the resistance and future historians considered both the risks of acting and the risks of not acting: the risks of implementing a given strategy and the risks of not implementing it. In their case, the failure to carry out an effective strategy would have resulted in a destroyed planet and the loss of centuries of social justice efforts. The failure to carry out an effective strategy (or a failure to act at all) would have killed billions of humans and countless nonhumans. There were substantial risks for taking decisive action, risks that caused most people to stick to safer symbolic forms of action. But the risks of inaction were far greater and more permanent.

Timeliness: Properly implemented, Decisive Ecological Warfare was able to accomplish its objective within a suitable time frame, and in a reasonable sequence. Under DEW, decisive action was scaled up as rapidly as it could be based on the underlying support infrastructure. The exact point of no return for catastrophic climate change was unclear, but if there are historians or anyone else alive in the future, DEW and other measures were able to head off that level of climate change. Most other proposed measures in the beginning weren’t even trying to do so.

Simplicity and Consistency: Although a fair amount of context and knowledge was required to carry out this strategy, at its core it was very simple and consistent. It was robust enough to deal with unexpected events, and it could be explained in a simple and clear manner without jargon. The strategy was adaptable enough to be employed in many different local contexts.

Consequences: Action and inaction both have serious consequences. A serious collapse—which could involve large-scale human suffering—was frightening to many. Resisters in this alternate future believed first and foremost that a terrible outcome was not inevitable, and that they could make real changes to the way the future unfolded.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 19, 2019 | Strategy & Analysis

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Decisive Ecological Warfare” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

It’s important to note that, as in the case of protracted popular warfare, Decisive Ecological Warfare is not necessarily a linear progression. In this scenario resisters fall back on previous phases as necessary. After major setbacks, resistance organizations focus on survival and networking as they regroup and prepare for more serious action. Also, resistance movements progress through each of the phases, and then recede in reverse order. That is, if global industrial infrastructure has been successfully disrupted or fragmented (phase IV) resisters return to systems disruption on a local or regional scale (phase III). And if that is successful, resisters move back down to phase II, focusing their efforts on the worst remaining targets.

And provided that humans don’t go extinct, even this scenario will require some people to stay at phase I indefinitely, maintaining a culture of resistance and passing on the basic knowledge and skills necessary to fight back for centuries and millennia.

The progression of Decisive Ecological Warfare could be compared to ecological succession. A few months ago I visited an abandoned quarry, where the topsoil and several layers of bedrock had been stripped and blasted away, leaving a cubic cavity several stories deep in the limestone. But a little bit of gravel or dust had piled up in one corner, and some mosses had taken hold. The mosses were small, but they required very little in the way of water or nutrients (like many of the shoestring affinity groups I’ve worked with). Once the mosses had grown for a few seasons, they retained enough soil for grasses to grow.

Quick to establish, hardy grasses are often among the first species to reinhabit any disturbed land. In much the same way, early resistance organizations are generalists, not specialists. They are robust and rapidly spread and reproduce, either spreading their seeds aboveground or creating underground networks of rhizomes.

The grasses at the quarry built the soil quickly, and soon there was soil for wildflowers and more complex organisms. In much the same way, large numbers of simple resistance organizations help to establish communities of resistance, cultures of resistance, that can give rise to more complex and more effective resistance organizations.

The hypothetical actionists who put this strategy into place are able to intelligently move from one phase to the next: identifying when the correct elements are in place, when resistance networks are sufficiently mobilized and trained, and when external pressures dictate change. In the US Army’s field manual on operations, General Eric Shinseki argues that the rules of strategy “require commanders to master transitions, to be adaptive. Transitions—deployments, the interval between initial operation and sequels, consolidation on the objective, forward passage of lines—sap operational momentum. Mastering transitions is the key to maintaining momentum and winning decisively.”

This is particularly difficult to do when resistance does not have a central command. In this scenario, there is no central means of dispersing operational or tactical orders, or effectively gathering precise information about resistance forces and allies. Shinseki continues: “This places a high premium on readiness—well trained Soldiers; adaptive leaders who understand our doctrine; and versatile, agile, and lethal formations.” People resisting civilization in this scenario are not concerned with “lethality” so much as effectiveness, but the general point stands.

Resistance to civilization is inherently decentralized. That goes double for underground groups which have minimal contact with others. To compensate for the lack of command structure, a general grand strategy in this scenario becomes widely known and accepted. Furthermore, loosely allied groups are ready to take action whenever the strategic situation called for it. These groups are prepared to take advantage of crises like economic collapses.

Under this alternate scenario, underground organizing in small cells has major implications for applying the principles of war. The ideal entity for taking on industrial civilization would have been a large, hierarchal paramilitary network. Such a network could have engaged in the training, discipline, and coordinated action required to implement decisive militant action on a continental scale. However, for practical reasons, a single such network never arises. Similar arrangements in the history of resistance struggle, such as the IRA or various territory-controlling insurgent groups, happened in the absence of the modern surveillance state and in the presence of a well-developed culture of resistance and extensive opposition to the occupier.

Although underground cells can still form out of trusted peers along kinship lines, larger paramilitary networks are more difficult to form in a contemporary anticivilization context. First of all, the proportion of potential recruits in the general population is smaller than in any anticolonial or antioccupation resistance movements in history. So it takes longer and is more difficult to expand existing underground networks. The option used by some resistance groups in Occupied France was to ally and connect existing cells. But this is inherently difficult and dangerous. Any underground group with proper cover would be invisible to another group looking for allies (there are plenty of stories from the end of the war of resisters living across the hall from each other without having realized each other’s affiliation). And in a panopticon, exposing yourself to unproven allies is a risky undertaking.

A more plausible underground arrangement in this scenario is for there to have been a composite of organizations of different sizes, a few larger networks with a number of smaller autonomous cells that aren’t directly connected through command lines. There are indirect connections or communications via cutouts, but those methods are rarely consistent or reliable enough to permit coordinated simultaneous actions on short notice.

Individual cells rarely have the numbers or logistics to engage in multiple simultaneous actions at different locations. That job falls to the paramilitary groups, with cells in multiple locations, who have the command structure and the discipline to properly carry out network disruption. However, autonomous cells maintain readiness to engage in opportunistic action by identifying in advance a selection of appropriate local targets and tactics. Then once a larger simultaneous action happened (causing, say, a blackout), autonomous cells take advantage of the opportunity to undertake their own actions, within a few hours. In this way unrelated cells engage in something close to simultaneous attacks, maximizing their effectiveness. Of course, if decentralized groups frequently stage attacks in the wake of larger “trigger actions,” the corporate media may stop broadcasting news of attacks to avoid triggering more. So, such an approach has its limits, although large-scale effects like national blackouts can’t be suppressed in the news (and in systems disruption, it doesn’t really matter what caused a blackout in the first place, because it’s still an opportunity for further action).

When we look at some struggle or war in history, we have the benefit of hindsight to identify flaws and successes. This is how we judge strategic decisions made in World War II, for example, or any of those who have tried (or not) to intervene in historical holocausts. Perhaps it would be beneficial to imagine some historians in the distant future—assuming humanity survives—looking back on the alternate future just described. Assuming it was generally successful, how might they analyze its strengths and weaknesses?

For these historians, phase IV is controversial, and they know it had been controversial among resisters at the time. Even resisters who agreed with militant actions against industrial infrastructure hesitated when contemplating actions with possible civilian consequences. That comes as no surprise, because members of this resistance were driven by a deep respect and care for all life. The problem is, of course, that members of this group knew that if they failed to stop this culture from killing the planet, there would be far more gruesome civilian consequences.

A related moral conundrum confronted the Allies early in World War II, as discussed by Eric Markusen and David Kopf in their book The Holocaust and Strategic Bombing: Genocide and Total War in the Twentieth Century. Markusen and Kopf write that: “At the beginning of World War II, British bombing policy was rigorously discriminating—even to the point of putting British aircrews at great risk. Only obvious military targets removed from population centers were attacked, and bomber crews were instructed to jettison their bombs over water when weather conditions made target identification questionable. Several factors were cited to explain this policy, including a desire to avoid provoking Germany into retaliating against non-military targets in Britain with its then numerically superior air force.”19

Other factors included concerns about public support, moral considerations in avoiding civilian casualties, the practice of the “Phoney War” (a declared war on Germany with little real combat), and a small air force which required time to build up. The parallels between the actions of the British bombers and the actions of leftist militants from the Weather Underground to the ELF are obvious.

The problem with this British policy was that it simply didn’t work. Germany showed no such moral restraint, and British bombing crews were taking greater risks to attack less valuable targets. By February of 1942, bombing policy changed substantially. In fact, Bomber Command began to deliberately target enemy civilians and civilian morale—particularly that of industrial workers—especially by destroying homes around target factories in order to “dehouse” workers. British strategists believed that in doing so they could sap Germany’s will to fight. In fact, some of the attacks on civilians were intended to “punish” the German populace for supporting Hitler, and some strategists believed that, after sufficient punishment, the population would rise up and depose Hitler to save themselves. Of course, this did not work; it almost never does.

So, this was one of the dilemmas faced by resistance members in this alternate future scenario: while the resistance abhorred the notion of actions affecting civilians—even more than the British did in early World War II—it was clear to them that in an industrial nation the “civilians” and the state are so deeply enmeshed that any impact on one will have some impact on the other.

Historians now believe that Allied reluctance to attack early in the war may have cost many millions of civilian lives. By failing to stop Germany early, they made a prolonged and bloody conflict inevitable. General Alfred Jodl, the German Chief of the Operations Staff of the Armed Forces High Command, said as much during his war crimes trial at Nuremburg: “[I]f we did not collapse already in the year 1939 that was due only to the fact that during the Polish campaign, the approximately 110 French and British divisions in the West were held completely inactive against the 23 German divisions.”20

Many military strategists have warned against piecemeal or half measures when only total war will do the job. In his book Grand Strategy: Principles and Practices, John M. Collins argues that timid attacks may strengthen the resolve of the enemy, because they constitute a provocation but don’t significantly damage the physical capability or morale of the occupier. “Destroying the enemy’s resolution to resist is far more important than crippling his material capabilities … studies of cause and effect tend to confirm that violence short of total devastation may amplify rather than erode a people’s determination.”21 Consider, though, that in this 1973 book Collins may underestimate the importance of technological infrastructure and decisive strikes on them. (He advises elsewhere in the book that computers “are of limited utility.”22)

Other strategists have prioritized the material destruction over the adversary’s “will to fight.” Robert Anthony Pape discusses the issue in Bombing to Win, in which he analyzes the effectiveness of strategic bombing in various wars. We can wonder in this alternate future scenario if the resisters attended to Pape’s analysis as they weighed the benefits of phase III (selective actions against particular networks and systems) vs. phase IV (attempting to destroy as much of the industrial infrastructure as possible).

Specifically, Pape argues that targeting an entire economy may be more effective than simply going after individual factories or facilities:

Strategic interdiction can undermine attrition strategies, either by attacking weapons plants or by smashing the industrial base as a whole, which in turn reduces military production. Of the two, attacking weapons plants is the less effective. Given the substitution capacities of modern industrial economies, “war” production is highly fungible over a period of months. Production can be maintained in the short term by running down stockpiles and in the medium term by conservation and substitution of alternative materials or processes. In addition to economic adjustment, states can often make doctrinal adjustments.23

This analysis is poignant, but it also demonstrates a way in which the goals of this alternate scenario’s strategy differed from the goals of strategic bombing in historical conflicts. In the Allied bombing campaign (and in other wars where strategic bombing was used), the strategic bombing coincided with conventional ground, air, and naval battles. Bombing strategists were most concerned with choking off enemy supplies to the battlefield. Strategic bombing alone was not meant to win the war; it was meant to support conventional forces in battle. In contrast, in this alternate future, a significant decrease in industrial production would itself be a great success.

The hypothetical future historians perhaps ask, “Why not simply go after the worst factories, the worst industries, and leave the rest of the economy alone?” Earlier stages of Decisive Ecological Warfare did involve targeting particular factories or industries. However, the resisters knew that the modern industrial economy was so thoroughly integrated that anything short of general economic distruption was unlikely to have lasting effect.

This, too, is shown by historical attempts to disrupt economies. Pape continues, “Even when production of an important weapon system is seriously undermined, tactical and operational adjustments may allow other weapon systems to substitute for it.… As a result, efforts to remove the critical component in war production generally fail.” For example, Pape explains, the Allies carried out a bombing campaign on German aircraft engine plants. But this was not a decisive factor in the struggle for air superiority. Mostly, the Allies defeated the Luftwaffe because they shot down and killed so many of Germany’s best pilots.

Another example of compensation is the Allied bombing of German ball bearing plants. The Allies were able to reduce the German production of ball bearings by about 70 percent. But this did not force a corresponding decrease in German tank forces. The Germans were able to compensate in part by designing equipment that required fewer bearings. They also increased their production of infantry antitank weapons. Early in the war, Germany was able to compensate for the destruction of factories in part because many factories were running only one shift. They were not using their existing industrial capacity to its fullest. By switching to double or triple shifts, they were able to (temporarily) maintain production.

Hence, Pape argues that war economies have no particular point of collapse when faced with increasing attacks, but can adjust incrementally to decreasing supplies. “Modern war economies are not brittle. Although individual plants can be destroyed, the opponent can reduce the effects by dispersing production of important items and stockpiling key raw materials and machinery. Attackers never anticipate all the adjustments and work-arounds defenders can devise, partly because they often rely on analysis of peacetime economies and partly because intelligence of the detailed structure of the target economy is always incomplete.”24 This is a valid caution against overconfidence, but the resisters in this scenario recognized that his argument was not fully applicable to their situation, in part for the reasons we discussed earlier, and in part because of reasons that follow.

Military strategists studying economic and industrial disruption are usually concerned specifically with the production of war materiel and its distribution to enemy armed forces. Modern war economies are economies of total warin which all parts of society are mobilized and engaged in supporting war. So, of course, military leaders can compensate for significant disruption; they can divert materiel or rations from civilian use or enlist civilians and civilian infrastructure for military purposes as they please. This does not mean that overall production is unaffected (far from it), simply that military production does not decline as much as one might expect under a given onslaught.

Resisters in this scenario had a different perspective on compensation measures than military strategists. To understand the contrast, pretend that a military strategist and a militant ecological strategist both want to blow up a fuel pipeline that services a major industrial area. Let’s say the pipeline is destroyed and the fuel supply to industry is drastically cut. Let’s say that the industrial area undertakes a variety of typical measures to compensate—conservation, recycling, efficiency measures, and so on. Let’s say they are able to keep on producing insulation or refrigerators or clothing or whatever it is they make, in diminished numbers and using less fuel. They also extend the lifespan of their existing refrigerators or clothing by repairing them. From the point of view of the military strategist, this attack has been a failure—it has a negligible effect on materiel availability for the military. But from the perspective of the militant ecologist, this is a victory. Ecological damage is reduced, and with very few negative effects on civilians. (Indeed, some effects would be directly beneficial.)

And modern economies in general are brittle. Military economies mobilize resources and production by any means necessary, whether that means printing money or commandeering factories. They are economies of crude necessity. Industrial economies, in contrast, are economies of luxury. They mostly produce things that people don’t need. Industrial capitalism thrives on manufacturing desire as much as on manufacturing products, on selling people disposable plastic garbage, extra cars, and junk food. When capitalist economies hit hard times, as they did in the Great Depression, or as they did in Argentina a decade ago, or as they have in many places in many times, people fall back on necessities, and often on barter systems and webs of mutual aid. They fall back on community and household economies, economies of necessity that are far more resilient than industrial capitalism, and even more robust than war economies.

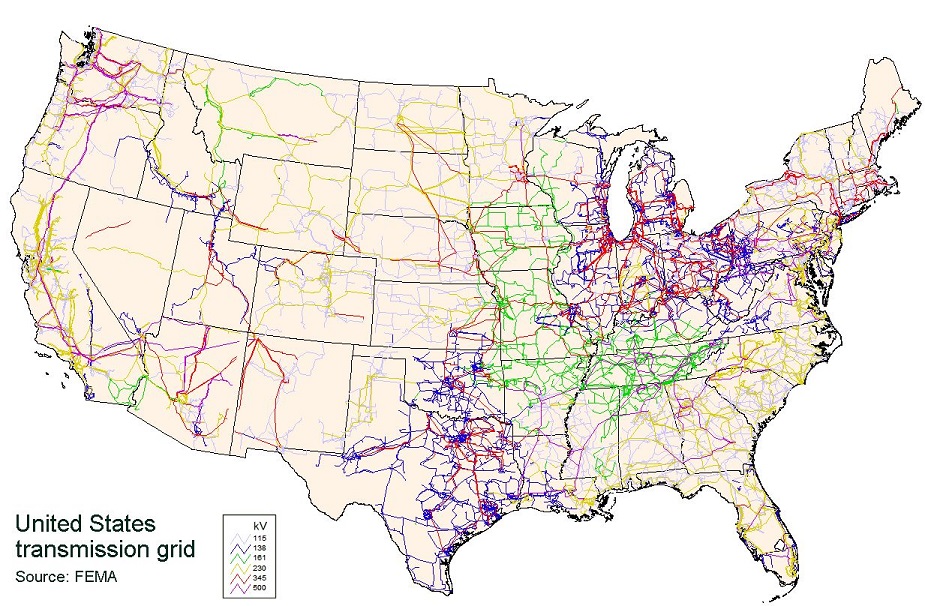

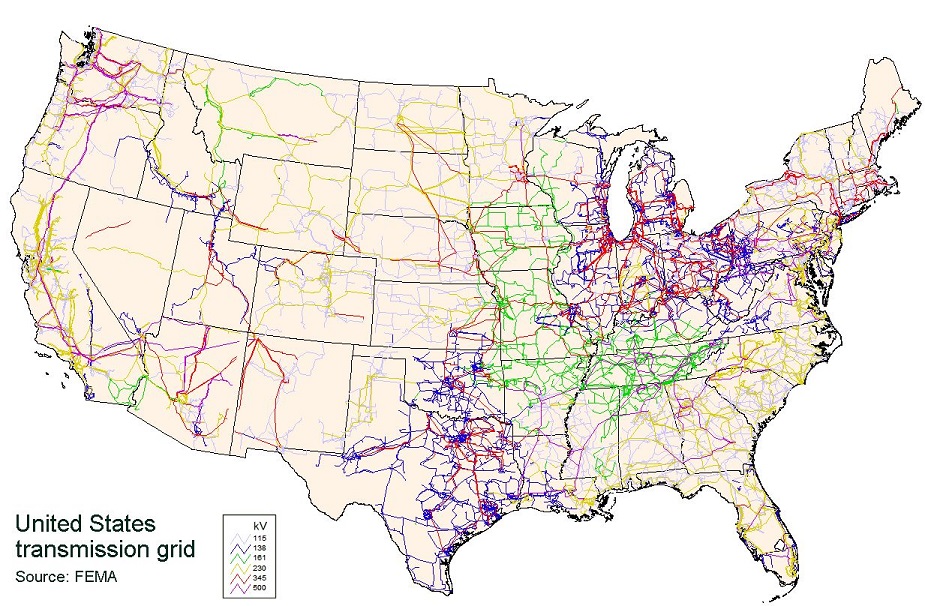

Nonetheless, Pape makes an important point when he argues, “Strategic interdiction is most effective when attacks are against the economy as a whole. The most effective plan is to destroy the transportation network that brings raw materials and primary goods to manufacturing centers and often redistributes subcomponents among various industries. Attacking national electric power grids is not effective because industrial facilities commonly have their own backup power generation. Attacking national oil refineries to reduce backup power generators typically ignores the ability of states to reduce consumption through conservation and rationing.” Pape’s analysis is insightful, but again it’s important to understand the differences between his premises and goals, and the premises and goals of Decisive Ecological Warfare.

The resisters in the DEW scenario had the goals of reducing consumption and reducing industrial activity, so it didn’t matter to them that some industrial facilities had backup generators or that states engaged in conservation and rationing. They believed it was a profound ecological victory to cause factories to run on reduced power or for nationwide oil conservation to have taken place. They remembered that in the whole of its history, the mainstream environmental movement was never even able to stop the growth of fossil fuel consumption. To actually reduce it was unprecedented.25

No matter whether we are talking about some completely hypothetical future situation or the real world right now, the progress of peak oil will also have an effect on the relative importance of different transportation networks. In some areas, the importance of shipping imports will increase because of factors like the local exhaustion of oil. In others, declining international trade and reduced economic activity will make shipping less important. Highway systems may have reduced usage because of increasing fuel costs and decreasing trade. This reduced traffic will leave more spare capacity and make highways less vulnerable to disruption. Rail traffic—a very energy-efficient form of transport—is likely to increase in importance. Furthermore, in many areas, railroads have been removed over a period of several decades, so that remaining lines are even now very crowded and close to maximum capacity.

Back to the alternative future scenario: In most cases, transportation networks were not the best targets. Road transportation (by far the most important form in most countries) is highly redundant. Even rural parts of well-populated areas are crisscrossed by grids of county roads, which are slower than highways, but allow for detours.

In contrast, targeting energy networks was a higher priority to them because the effect of disrupting them was greater. Many electrical grids were already operating near capacity, and were expensive to expand. They became more important as highly portable forms of energy like fossil fuels were partially replaced by less portable forms of energy, specifically electricity generated from coal-burning and nuclear plants, and to a lesser extent by wind and solar energy. This meant that electrical grids carried as much or more energy as they do now, and certainly a larger percentage of all energy consumed. Furthermore, they recognized that energy networks often depend on a few major continent-spanning trunks, which were very vulnerable to disruption.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Dec 29, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

Featured image: Alison mackeyDiscover, based on NASA Earth Observatory image by Robert Simmon, using Suomi NPP VIIRS data provided by Chris Elvidge/NOAA National Geophysical Data Center

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Decisive Ecological Warfare” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

In this alternate future scenario, Decisive Ecological Warfare has four phases that progress from the near future through the fall of industrial civilization. The first phase is Networking & Mobilization. The second phase is Sabotage & Asymmetric Action. The third phase is Systems Disruption. And the fourth and final phase is Decisive Dismantling of Infrastructure.

Each phase has its own objectives, operational approaches, and organizational requirements. There’s no distinct dividing line between the phases, and different regions progress through the phases at different times. These phases emphasize the role of militant resistance networks. The aboveground building of alternatives and revitalization of human communities happen at the same time. But this does not require the same strategic rigor; rebuilding healthy human communities with a subsistence base must simply happen as fast as possible, everywhere, with timetables and methods suited to the region. This scenario’s militant resisters, on the other hand, need to share some grand strategy to succeed.

PHASE I: NETWORKING & MOBILIZATION

Preamble: In phase one, resisters focus on organizing themselves into networks and building cultures of resistance to sustain those networks. Many sympathizers or potential recruits are unfamiliar with serious resistance strategy and action, so efforts are taken to spread that information. But key in this phase is actually forming the above- and underground organizations (or at least nuclei) that will carry out organizational recruitment and decisive action. Security culture and resistance culture are not very well developed at this point, so extra efforts are made to avoid sloppy mistakes that would lead to arrests, and to dissuade informers from gathering or passing on information.

Training of activists is key in this phase, especially through low-risk (but effective) actions. New recruits will become the combatants, cadres, and leaders of later phases. New activists are enculturated into the resistance ethos, and existing activists drop bad or counterproductive habits. This is a time when the resistance movement gets organized and gets serious. People are putting their individual needs and conflicts aside in order to form a movement that can fight to win.

In this phase, isolated people come together to form a vision and strategy for the future, and to establish the nuclei of future organizations. Of course, networking occurs with resistance-oriented organizations that already exist, but most mainstream organizations are not willing to adopt positions of militancy or intransigence with regard to those in power or the crises they face. If possible, they should be encouraged to take positions more in line with the scale of the problems at hand.

This phase is already underway, but a great deal of work remains to be done.

Objectives:

- To build a culture of resistance, with all that entails.

- To build aboveground and underground resistance networks, and to ensure the survival of those networks.

Operations:

- Operations are generally lower-risk actions, so that people can be trained and screened, and support networks put in place. These will fall primarily into the sustaining and shaping categories.

- Maximal recruitment and training is very important at this point. The earlier people are recruited, the more likely they are to be trustworthy and the longer time is available to screen them for their competency for more serious action.

- Communications and propaganda operations are also required for outreach and to spread information about useful tactics and strategies, and on the necessity for organized action.

Organization:

- Most resistance organizations in this scenario are still diffuse networks, but they begin to extend and coalesce. This phase aims to build organization.

PHASE II: SABOTAGE & ASYMMETRIC ACTION

Preamble: In this phase, the resisters might attempt to disrupt or disable particular targets on an opportunistic basis. For the most part, the required underground networks and skills do not yet exist to take on multiple larger targets. Resisters may go after particularly egregious targets—coal-fired power plants or exploitative banks. At this phase, the resistance focus is on practice, probing enemy networks and security, and increasing support while building organizational networks. In this possible future, underground cells do not attempt to provoke overwhelming repression beyond the ability of what their nascent networks can cope with. Furthermore, when serious repression and setbacks do occur, they retreat toward the earlier phase with its emphasis on organization and survival. Indeed, major setbacks probably do happen at this phase, indicating a lack of basic rules and structure and signaling the need to fall back on some of the priorities of the first phase.

The resistance movement in this scenario understands the importance of decisive action. Their emphasis in the first two phases has not been on direct action, but not because they are holding back. It’s because they are working as well as they damned well can, but doing so while putting one foot in front of the other. They know that the planet (and the future) need their action, but understand that it won’t benefit from foolish and hasty action, or from creating problems for which they are not yet prepared. That only leads to a morale whiplash and disappointment. So their movement acts as seriously and swiftly and decisively as it can, but makes sure that it lays the foundation it needs to be truly effective.

The more people join that movement, the harder they work, and the more driven they are, the faster they can progress from one phase to the next.

In this alternate future, aboveground activists in particular take on several important tasks. They push for acceptance and normalization of more militant and radical tactics where appropriate. They vocally support sabotage when it occurs. More moderate advocacy groups use the occurrence of sabotage to criticize those in power for failing to take action on critical issues like climate change (rather than criticizing the saboteurs). They argue that sabotage would not be necessary if civil society would make a reasonable response to social and ecological problems, and use the opportunity and publicity to push solutions to the problems. They do not side with those in power against the saboteurs, but argue that the situation is serious enough to make such action legitimate, even though they have personally chosen a different course.

At this point in the scenario, more radical and grassroots groups continue to establish a community of resistance, but also establish discrete organizations and parallel institutions. These institutions establish themselves and their legitimacy, make community connections, and particularly take steps to found relationships outside of the traditional “activist bubble.” These institutions also focus on emergency and disaster preparedness, and helping people cope with impending collapse.

Simultaneously, aboveground activists organize people for civil disobedience, mass confrontation, and other forms of direct action where appropriate.

Something else begins to happen: aboveground organizations establish coalitions, confederations, and regional networks, knowing that there will be greater obstacles to these later on. These confederations maximize the potential of aboveground organizing by sharing materials, knowledge, skills, learning curricula, and so on. They also plan strategically themselves, engaging in persistent planned campaigns instead of reactive or crisis-to-crisis organizing.

Objectives:

- Identify and engage high-priority individual targets. These targets are chosen by these resisters because they are especially attainable or for other reasons of target selection.

- Give training and real-world experience to cadres necessary to take on bigger targets and systems. Even decisive actions are limited in scope and impact at this phase, although good target selection and timing allows for significant gains.

- These operations also expose weak points in the system, demonstrate the feasibility of material resistance, and inspire other resisters.

- Publically establish the rationale for material resistance and confrontation with power.

- Establish concrete aboveground organizations and parallel institutions.

Operations:

- Limited but increasing decisive operations, combined with growing sustaining operations (to support larger and more logistically demanding organizations) and continued shaping operations.

- In decisive and supporting operations, these hypothetical resisters are cautious and smart. New and unseasoned cadres have a tendency to be overconfident, so to compensate they pick only operations with certain outcomes; they know that in this stage they are still building toward the bigger actions that are yet to come.

Organization:

- Requires underground cells, but benefits from larger underground networks. There is still an emphasis on recruitment at this point. Aboveground networks and movements are proliferating as much as they can, especially since the work to come requires significant lead time for developing skills, communities, and so on.

PHASE III: SYSTEMS DISRUPTION

Preamble: In this phase resisters step up from individual targets to address entire industrial, political, and economic systems. Industrial systems disruption requires underground networks organized in a hierarchal or paramilitary fashion. These larger networks emerge out of the previous phases with the ability to carry out multiple simultaneous actions.

Systems disruption is aimed at identifying key points and bottlenecks in the adversary’s systems (electrical, transport, financial, and so on) and engaging them to collapse those systems or reduce their functionality. This is not a one-shot deal. Industrial systems are big and can be fragile, but they are sprawling rather than monolithic. Repairs are attempted. The resistance members understand that. Effective systems disruption requires planning for continued and coordinated actions over time.

In this scenario, the aboveground doesn’t truly gain traction as long as there is business as usual. On the other hand, as global industrial and economic systems are increasingly disrupted (because of capitalist-induced economic collapse, global climate disasters, peak oil, peak soil, peak water, or for other reasons) support for resilient local communities increases. Failures in the delivery of electricity and manufactured goods increases interest in local food, energy, and the like. These disruptions also make it easier for people to cope with full collapse in the long term—short-term loss, long-term gain, even where humans are concerned.

Dimitry Orlov, a major analyst of the Soviet collapse, explains that the dysfunctional nature of the Soviet system prepared people for its eventual disintegration. In contrast, a smoothly functioning industrial economy causes a false sense of security so that people are unprepared, worsening the impact. “After collapse, you regret not having an unreliable retail segment, with shortages and long bread lines, because then people would have been forced to learn to shift for themselves instead of standing around waiting for somebody to come and feed them.”18