by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Oct 7, 2018 | Lobbying

Featured image: an eviction of Maasai in Loliondo. Photo: tourismobserver.com

by Oakland Institute

Oakland, CA—On September 25, 2018, the East African Court of Justice (EACJ) awarded a major victory to four Maasai villages fighting for their rights to their land in northern Tanzania. The case revolves around violent government-led evictions of Maasai villagers in Loliondo – which included burning their homes, arbitrary arrest, forced eviction from their villages, and confiscating their livestock – that took place in August 2017, as well as the ongoing harassment and arrest of villagers involved in the case by the Tanzanian police. The four villages named in the case are legally registered owners of their land.

The Court’s ruling grants an injunction that prohibits the Tanzanian government from evicting the Maasai communities from a vital 1,500km2 parcel of land. Furthermore, it prohibits the destruction of Maasai homesteads and the confiscation of livestock on said land, and bans the office of the Inspector General of Police from harassing and intimidating the plaintiffs, pending the full determination of their case. The injunction remains in effect until a ruling on the full case concerning the August 2017 evictions can be heard.

“IN THE RESULT, HAVING HELD AS WE HAVE IN THIS RULING ABOVE, WE DO HEREBY ALLOW THE SUBSISTING APPLICATION WITH THE FOLLOWING ORDERS:

A. AN INTERIM ORDER DOTH ISSUE RESTRAINING THE RESPONDENT, AND ANY PERSONS OR OFFICES ACTING ON HIS BEHALF, FROM EVICTING THE APPLICANTS’ RESIDENTS FROM THE DISPUTED LAND, BEING THE LAND COMPRISED IN THE 1,500 SQ KM OF LAND IN THE WILDLIFE CONSERVATION AREA BORDERING SERENGETI NATIONAL PARK; DESTROYING THEIR HOMESTEADS OR CONFISCATING THEIR LIVESTOCK ON THAT LAND, UNTIL THE DETERMINATION OF REFERENCE NO. 10 OF 2017.

B. AN INTERIM ORDER DOTH ISSUE AGAINST THE RESPONDENT, RESTRAINING THE OFFICE OF THE INSPECTOR GENERAL OF POLICE FROM HARASSING OR INTIMIDATING THE APPLICANTS IN RELATION TO REFERENCE NO. 10 OF 2017 PENDING THE DETERMINATION THEREOF.

C. THE COSTS HEREOF SHALL ABIDE THE OUTCOME OF THE REFERENCE. WE DIRECT THAT IT BE FIXED FOR HEARING FORTHWITH.”

In their ruling, Justices Monica K. Mugenyi, Faustin Ntezilyayo, and Fakihi A. Jundu noted that the interim order and corresponding affidavit filed by the Maasai “paint[ed] a picture of widespread social upheaval in Ololosokwan village and an attempt to stifle village representatives’ and/or the affected persons’ access to justice.” They further ruled that the government’s argument that the evictions were in service of the protection of the local ecosystem “pales in the face of the social disruption and human suffering that would inevitably flow from the continued eviction of the Applicants’ residents.”

The Oakland Institute’s research has exposed internationally the ongoing plight and human rights violations of the Maasai villagers as their land rights are denied in the name of conservation and to the benefit of safari companies, such as Boston-based Thomson Safaris and the UAE-based Ortello Business Corporation, which runs hunting excursions for the Emirati royal family.

“The Court’s decision is a major win for the communities of Ololosokwan, Oloirien, Kirtalo, and Arash, particularly in light of the ongoing harassment and intimidation by the police and the recent wrongful arrests of local secondary school teacher Clinton Kairung and Belgian citizen Ingrid de Draeve, who was mistaken for a Swedish blogger who has written extensively on the issues facing the Maasai in the region,” said Anuradha Mittal, Executive Director of the Oakland Institute.

“It is now vital for both the East African Court and the international community to ensure that the Tanzanian government abides by this ruling and immediately halts the harassment, intimidation, and violence it has waged against the villages involved in this case as well as the broader Maasai community in Loliondo. It is time for the Tanzanian government to stop colluding with game parks and safari companies and finally recognize the land rights of its Maasai population as well as their longstanding role as environmental stewards of the land,” she continued.

###

For more information on this case and larger issues regarding the Maasai’s struggles for their land and livelihoods in the region, please see Losing the Serengeti: The Maasai Land that Was to Run Forever.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Oct 4, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Introduction to Strategy” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

Resistance is not one-sided. For any strategy resisters can come up with, those in power will do whatever they can to disrupt and undermine it. Any strategic process—for either side—will change the context of the strategy. A strategic objective is a moving target, and there is an intrinsic delay in implementing any strategy. The way to hit a moving target is by “leading” it—by looking slightly ahead of the target. Don’t aim for where the target is; aim for where it’s going to be.

Too often we as activists of whatever stripe don’t do this. We often follow the target, and end up missing badly. This is especially clear when dealing with issues of global ecology, which often involve tremendous lag time. We’re worried about the global warming that’s happening now, but to avert current climate change, we should have acted thirty years ago. Mainstream environmentalism in particular is decades behind the target, and the movement’s priorities show it. The most serious mainstream environmental efforts are for tiny changes that don’t reflect the seriousness of our current situation, let alone the situation thirty years from now. They’ve got us worried about hybrid cars and changing lightbulbs, when we should be trying to head off runaway global warming, cascading ecological collapses, the creation of hundreds of millions of ecological refugees or billions of human casualties, and the social justice disasters that accompany such phenomena. If we can’t avert global ecological collapse, then centuries of social justice gains will go down the toilet.

It’s worth spelling this out. There have been substantial improvements in humans rights in recent decades, along with major social justice concessions in many parts of the world. Much of this progress can be rightly attributed to the tireless work of social justice advocates and extensive organized resistance. But look at, for example, the worsening ratio between the income of the average employee and the average CEO. The economy has become less equitable, even though the middle rungs of income now have a higher “standard of living.” And all of this is based on a system that systematically destroys natural biomes and rapidly draws down finite resources. It’s not that everyone is getting an equal slice of the pie, or even that the pie is bigger now. If we’re getting more pie, it’s largely because we’re eating tomorrow’s pie today. And next week’s pie, and next month’s pie.

For example, the only reason large-scale agriculture even functions is because of cheap oil; without that, large-scale agriculture goes back to depending on slavery and serfdom, as in most of the history of civilization. In the year 1800, at the dawn of the industrial revolution, close to 80 percent of the human population of this planet was in some form of serfdom or slavery.51 And that was with a fraction of the current human population of seven billion. That was with oceans still relatively full of fish, global forests still relatively intact, with prairie and agricultural lands in far better condition than they are now, with water tables practically brimming by modern standards. What do you think is going to happen to social justice concessions when cheap oil—and hence, almost everything else—runs out? Without a broad-based and militant resistance movement that can focus on these urgent threats, the year 1800 is going to look downright cheerful.

If we want to be effective strategists, we must be capable of planning for the long term. We must anticipate changes and trends that affect our struggle. We must plan and prepare for the changing nature of our fight six months down the road, two years down the road, ten years down the road, and beyond.

We need to look ahead of the target, but we also need to plan for setbacks and disruptions. That’s one of the reasons that the strategy of protracted popular warfare was so effective for revolutionaries in China and Vietnam. That strategy consisted of three stages: the first was based on survival and the expansion of revolutionary networks; the second was guerrilla warfare; and the third was a transition to conventional engagements to decisively destroy enemy forces. The intrinsic flexibility of this strategy meant that revolutionaries could seamlessly move along that continuum as necessary to deal with a changing balance of power. It was almost impossible to derail the strategy, since even if the revolutionaries faced massive setbacks, they could simply return to a strategy of survival.

How does anyone evaluate a particular strategy? There are several key characteristics to check, based on everything we’ve covered in this chapter.

Objective. Does the strategy have a well-defined and attainable objective? If there is no clear objective there is no strategy. The objective doesn’t have to be a static end point—it can be a progressive change or a process. However, it should not be a “blank or unrepresentable utopia.”

Feasibility. Can the organization get from A to B? Does the strategy have a clear path from the current context to the desired objective? Does the plan include contingencies to deal with setbacks or upsets? Does the strategy make use of appropriate strategic precepts like the nine principles of war? Is the strategy consonant with the nature of asymmetric conflict?

Resource Limitations. Does the movement or organization have the number of people with adequate skills and competencies required to carry out the strategy? Does it have the organizational capacity? If not, can it scale up in a reasonable time?

Tactics. Are the required tactics available? Are the tactics and operations called for by the plan adequate to the scale, scope, and seriousness of the objective? If the required tactics are not available or not being implemented currently, why not? Is the obstacle organizational or ideological in nature? What would need to happen to make the required tactics available, and how feasible are those requirements?

Risk. Is the level of risk required to carry out the plan acceptable given the importance of the objective? Remember, this goes both ways. It is important to ask, what is the risk of acting? as well as what is the risk of not acting? A strategy that overreaches based on available resources and tactics might be risky. And, although it may seem counterintuitive at first, a strategy that is too hesitant or conservative may be even more risky, because it may be unable to achieve the objective. If the objective of the strategy is to prevent catastrophic global warming, taking serious action may indeed seem risky—but the consequences of insufficient action are far more severe.

Timeliness. Can the plan accomplish its objective within a suitable time frame? Are events to happen in a reasonable sequence? A strategy that takes too long may be completely useless. Indeed, it may be worse than useless, and become actively harmful by drawing people or resources from more effective and timely strategic alternatives.

Simplicity and Consistency. Is the plan simple and consistent? The plan should not depend on a large number of prerequisites or complex chains of events. Only simple plans work in emergencies. The plan itself must be explained in a straightforward manner without the use of weasel words or vague or mystical concepts. The plan must also be internally consistent—it must make sense and be free of serious internal contradictions.

Consequences. What are the other consequences or effects of this strategy beyond the immediate objective and operations? Might there be unintended consequences, reprisals, or effects on bystanders? Can such undesirable effects be limited by adjusting the strategy? Does the value of the objective outweigh the cost of those consequences?

A solid grand strategy is essential, but it’s not enough. Any strategy is made out of smaller tactical building blocks. In the next chapter, “Tactics and Targets,” I outline the tactics that an effective resistance movement to stop this culture from killing the planet might use, and discuss how such a movement might select targets and plan effective actions.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Sep 25, 2018 | Lobbying

Featured image: A grizzly bear in Yellowstone National Park. Jim Peaco / National Park Service

by Olivia Rosane / Ecowatch

A federal judge restored endangered species protections for grizzly bears in and around Yellowstone National Park on Monday, The Huffington Post reported, putting a permanent halt to plans by Wyoming and Idaho to launch the first Yellowstone-area grizzly hunt in four decades.

U.S. District Judge Dana Christensen had already placed a temporary restraining order on the hunts, which would have started Sept. 1 and allowed for the killing of up to 23 bears, while he considered the larger question of whether Endangered Species Act protections should be restored. The bears’ management will now return to the federal government.

Christensen wrote in his ruling that his decision was “not about the ethics of hunting.” Rather, he agreed with environmental and tribal groups that the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) had not considered the genetic health of other lower-48 grizzly populations when it delisted the Yellowstone area bears in 2017.

“By delisting the Greater Yellowstone grizzly without analyzing how delisting would affect the remaining members of the lower-48 grizzly designation, the Service failed to consider how reduced protections in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem would impact the other grizzly populations,” Christensen wrote, according to The Huffington Post. “Thus, the Service ‘entirely failed to consider an important aspect of the problem.'”

Bear advocates said the Yellowstone population was growing large enough to merge with other populations, which would be a win-win for the genetic diversity of all bears involved.

“The Service appropriately recognized that the population’s genetic health is a significant factor demanding consideration,” Christensen wrote. “However, it misread the scientific studies it relied upon, failing to recognize that all evidence suggests that the long-term viability of the Greater Yellowstone grizzly is far less certain absent new genetic material.”

Native American and environmental groups applauded the decision.

“We have a responsibility to speak for the bears, who cannot speak for themselves,” Northern Cheyenne Nation President Lawrence Killsback said in a statement Monday reported by The Huffington Post. “Today we celebrate this victory and will continue to advocate on behalf of the Yellowstone grizzly bears until the population is recovered, including within the Tribe’s ancestral homeland in Montana and other states.”

The FWS told The Washington Post it was reviewing the ruling.

“We stand behind our finding that the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem grizzly bear is biologically recovered and no longer requires protection. . . . Our determination was based on our rigorous interpretation of the law and is supported by the best available science and a comprehensive conservation strategy developed with our federal, state, and tribal partners,” the FWS told The Washington Post.

The FWS first attempted to delist the bears in 2007, but that move was also blocked in federal court over concerns that one of the bears’ food sources, whitebark pine seeds, were threatened by climate change.

In its 2017 ruling, the FWS said that it had reviewed the case and found the decline of the whitebark pine seeds did not pose a major threat.

Grizzlies in the lower 48 states were first listed as endangered in 1975, when their historic range had been reduced by 98 percent.

The Yellowstone grizzlies numbered fewer than 140 at the time. The population has since rebounded to about 700, according to The Washington Post.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Sep 23, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Introduction to Strategy” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

This shift toward more militant defiance of slavery was all wonderful, of course. And it certainly increased the success of the Underground Railroad if a slave catcher knew that a trip into strongly abolitionist areas might end with a bullet in his chest. But, again, there was a problem. Even this rapidly growing and increasingly defiant abolitionist movement had not been able to successfully challenge the institution of slavery itself. The situation continued to get worse. Writes Stewart, “More than two decades of peacefully preaching against the sin of slavery had yielded not emancipation but several new slave states and an increase of over half a million held in bondage, trends that seemingly secured a death grip by the ‘slave power’ on American life.”41 Cotton agriculture in the South often destroyed the landbase, and that, combined with a growing slave population, meant that it was profitable—according to some historians, even imperative—that slaveholders expand westward in order to maintain the slave economy. Each new slave state shifted the balance of political power in the Union even more toward slavery.

Enter John Brown, an ardent abolitionist and deeply moral man who had clashed with proslavery militants on several occasions before. Brown, a wool grower by trade, had fought in the struggle to make the new state of Kansas an antislavery state. He was apparently not much interested in making speeches, and thought little of rhetoric alone given the seriousness of the situation. Brown was frustrated with mainstream abolitionists, reportedly exclaiming, “These men are all talk. What we need is action—action!”

And action was exactly what he had in mind. In 1858, Brown ran a series of small raids from Kansas into Missouri, liberating slaves and stealing horses and wagons. He helped bring the liberated slaves to Canada, but his main plan was much more daring. Secretly raising funds from wealthy abolitionist donors, buying arms, and training a small group of paramilitary recruits, Brown planned a raid on the armory at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. The plan was simple. Brown and his troops would raid the armory, which contained tens of thousands of small arms. They would steal as many arms as they could, then liberate and arm the slaves in the area. They would head south, operating as guerrillas, liberating and arming slaves and fighting only in self-defense. Brown hoped for a movement that would grow exponentially as they moved into the Deep South, a cascade of action that would unravel and destroy the institution of slavery itself.

Although some historians—especially those impugning Brown—have considered him an insurrectionist, that’s not an accurate reflection of his intended strategy. Brown’s biographer, Louis A. DeCaro, has discussed this very fact: “Brown nowhere planned insurrection, which is essentially an armed uprising with the intention of eliminating slave masters. Brown planned an armed defensive campaign. His intention was to lead enslaved people away from slavery, arm them to fight defensively while they liberated still more people, fighting in small groups in the mountains, until the economy of slavery collapsed. Brown did not believe in killing unless it was absolutely necessary.”42

Tragically, things were not to go as planned. Part of the problem was numbers. While a draft plan for the Harpers Ferry raid called for thousands of men, on the day of the raid Brown had only twenty-one, both white and black. In an unusual situation for resistance fighters, Brown had far more guns than men. From Northern abolition societies, Brown had received about ten carbines (short rifles) for each fighter available. Nonetheless, Brown, deeply driven, decided to proceed.

At first the raid went smoothly. They easily entered the town of Harpers Ferry, cut the telegraph wires, and captured the armory. But Brown made a tactical error—the worst tactical error a guerrilla can make—by failing to seize the arms and move on as soon as possible. As a result, local militia were soon firing on the armory from the town while the militants remained inside. After continuing exchanges of fire and several deaths, US Marines under the command of Robert E. Lee arrived, surrounding and then storming the armory. Five of Brown’s fighters escaped, ten were killed, and the rest captured. Those captured were imprisoned and stood trial. John Brown and five others were subsequently hanged.

It’s extremely important to understand why the raid failed. The problem was tactical, rather than strategic in nature. Although he was unsuccessful, even his enemies at the time said that “it was among the best planned and executed conspiracies that ever failed.”43 In fact, even on the tactical level Brown’s planning was excellent. But instead of employing the hit-and-run tactics asymmetric forces depend on, Brown got bogged down in the armory. According to biographer Louis A. DeCaro, “The reason the raid did not succeed was because he paid too much concern to his hostages, including some whining slave masters, and undermined himself in trying to negotiate with them.” Furthermore, rather astonishingly, DeCaro notes that Brown even allowed “his prisoners to go home and see their families under guard and send out for their breakfast.”44 Indeed, Brown was in Harpers Ferry for almost two days before the marines arrived. According to DeCaro: “Had he kept to his own plan and schedule, he and his fugitive allies would have almost walked away from Harper’s Ferry without facing any significant opposition, and could have easily retreated to the mountains as planned. Contrary to the notion that he was a crazy man and a killer, it seems that John Brown was actually too tender-hearted and still hoped to resolve some of the issue by negotiation. This was his greatest error.”45

News of the raid spread swiftly. The knee-jerk response among many abolitionists and their sympathizers was one of contempt for Brown’s actions. Even Lincoln (perhaps afraid of offending the South) called him a “misguided fanatic.” Henry David Thoreau, notably, was one of the few who immediately sprang to Brown’s defense. He begged his fellow citizens to listen: “I hear many condemn these men because they were so few. When were the good and the brave ever in a majority?”46 (Now is a good time to ask that question of ourselves and our allies, especially if we are waiting for someone else to act.)

DeCaro notes that Brown’s reputation in history has been consistently attacked and “the ‘facts’ of his case have been mediated from slave masters, pro-slavery people, and pacifists.”47 (Those in the latter category will hopefully find it relevant, if embarrassing, that they are lumped in with such dreadful company.) But not everyone has been so easily convinced that Brown was wrongheaded. Malcolm X, not surprisingly, had great respect for John Brown and little patience for white liberals who criticized his methods. “John Brown … was a white man who went to war against white people to help free slaves. And any white man who is ready and willing to shed blood for your freedom—in the sight of other whites, he’s nuts.” In other words, those who hate Brown do so in large part because he was a “race traitor.”

The raid on Harpers Ferry increased tensions between the North and South. Some historians rank it among the proximal causes of the Civil War. This is ironic, as Brown despised unnecessary bloodshed, and, like many at the time, was aware that a war between North and South was very likely looming. It was his hope that his strategy of guerrilla warfare would end the slave economy while averting a civil war, which could be even bloodier. It’s possible that, had he been more ruthless, he might have succeeded. His hesitation to be ruthless, then, may have resulted in a much greater number of deaths. Brown’s problem, as with many of those who fight injustice, was that he was simply too nice, even when dealing with vicious oppressors. Brown himself realized this too late. On the day he was hanged he wrote the following: “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood. I had, as I now think, vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed it might be done.”48

Outright Civil War

Brown’s failed attack was a flashpoint for the rising strain between North and South, and outright Civil War shortly followed. This is not the place to discuss the full history of the Civil War or all its causes, but there are a few points that are relevant to understanding how outright Civil War impacted resistance. Many people have been taught that the Civil War was “fought to end slavery,” but this is not true. Social justice was not a main driving force behind the Civil War, and prior to the outbreak of hostilities, Abraham Lincoln insisted that slavery was a choice for each state to make. It might be more accurate to say that the Civil War was precipitated by the growth of “slave power” (that is, the power of slaving-holding states) and by the tensions between conflicting economic and political institutions. The immediate cause of the Civil War was the secession of slave-holding states into the Confederacy, which Abraham Lincoln would not allow.

The outbreak of Civil War (and especially the invasion of the Confederacy by Union forces) resulted in two distinct changes for abolitionists. First, slave resistance in the South was vastly increased, and second, many Northerners who were not abolitionists were forced to come face to face with slavery.

The impact of the Civil War on slave resistance was extensive even where armed conflict was not yet occurring. Many slaves attempted escape to get across Union lines where they would be ostensibly free, and many of those escapees joined the Union army to fight for the end of the Confederacy and the end of slavery. But even those slaves who did not run were roused to active resistance—or at least withdrawal of their labor. As in France in 1943, more and more slaves began to resist when it became clear that the slave owners might lose.

Historian Bruce Levine notes that:

The wartime breakdown of slavery became apparent beyond those Southern districts actually penetrated by Union troops. In still-unoccupied parts of the Confederacy, masters, army officers, and government officials clashed repeatedly over which of them had the greater need for and claim to the labor of remaining slaves. This process eroded the real power of Rebel masters—and emboldened those still under their formal control. A South Carolina overseer bemoaned the “goodeal of obstanetry” he faced among “Some of the Peopl” working on his plantation, “mostly amongst the Woman a goodeal of Quarling and disputing and telling lies.” James Alcorn, a Mississippi planter, found that Union raids in his area had “thoroughly demoralized” his slaves. (This phrase was common planter parlance for saying that power over a slave—and a slave’s fear of a master—had faded.) That change, moaned Alcorn, had rendered his human property “no longer of any practical value.” Even among those field laborers who had not fled, a Louisiana overseer reported to his employer, “but very few are faithful—Some of those who remain are worse than those who have gone.” In one district after another, bondspeople began to call for improvements in their conditions as well as implicit but no less momentous alterations in their status—and they withheld their labor until such demands were met.… “Their condition is one of perfect anarchy and rebellion,” Georgia plantation mistress Mary Jones confided in her journal. “They have placed themselves in perfect antagonism to their owners and to all government and control. We dare not predict the end of all this.”49

The nature of slave resistance changed as well, with organizers shifting from the survival-orientated operations of the Underground Railroad to decisive military operations. Many former slaves worked with the Union forces, including Harriet Tubman, who worked as a scout and led raids and mass liberations of slaves.

The war also forced nonabolitionist northerners to confront the nature of slavery head-on. Writes Levine, “The wartime crisis of slavery left a deep imprint not only on southern whites but also on Union troops. As Lincoln and others had feared, and as the 1862 elections made clear, the decision to add the destruction of slavery to the North’s war aims at first provoked fierce opposition in parts of the Union. Few Union soldiers had gone to war committed to abolition … the Union soldier’s firsthand exposure to the real nature of slavery did much, however, to change minds and soften hearts.”50

When a destructive system is deeply entrenched, and when average people are isolated from the costs of that system, real change doesn’t come just from speeches. Real change happens—and only can happen—when that system is broken down by force. Then the oppressed gain the breathing room needed to fight back, and the apathetic can get their first look at that system’s real face.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Sep 19, 2018 | Protests & Symbolic Acts

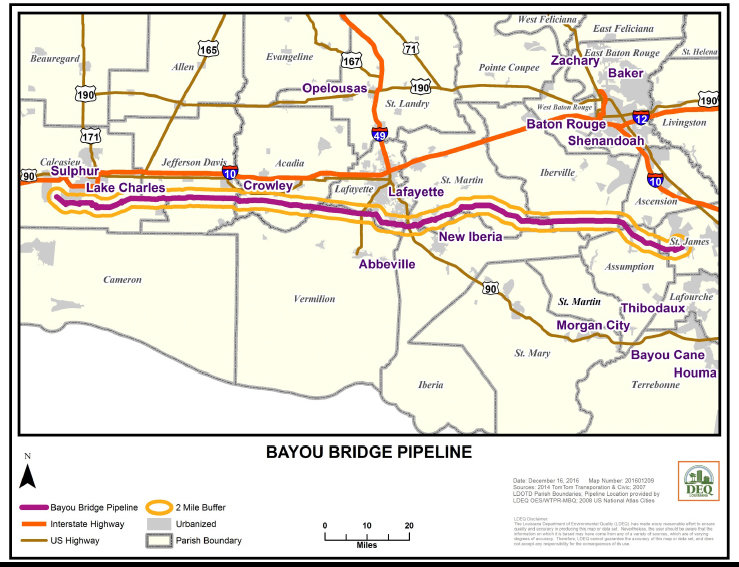

In Solidarity with #NoBayouBridgePipeline National Day of Action

by Ginew

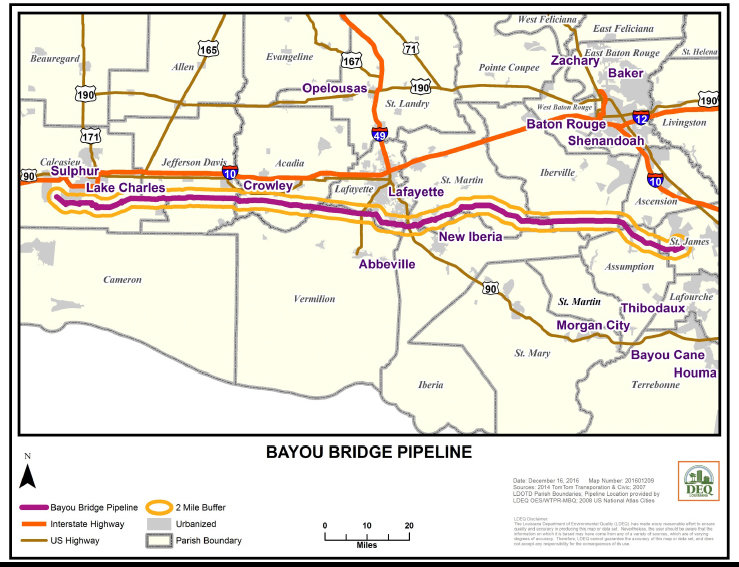

BEMIDJI, Minnesota—Early Tuesday morning, September 18th, a group of indigenous water protectors from the Ginew Collective, raised a tipi and blocked a bridge south of Bemidji, halting work at a construction site for the recently permitted line 3 pipeline. Ginew (Golden Eagle) is a grassroots, frontlines effort led by indigenous women to protect Anishinaabe territory from the destruction of Enbridge’s Line 3 tar sands project.

While the tipi blockade prevented bulldozers and street paving machines from laying down new asphalt over the Mississippi, a local Anishinaabe woman held a water ceremony on the bank of the river offering medicine, prayers and songs. The action took place just miles from 3000 year old Dakota village sites near Lake LaSalle where Clearwater county road 230 crosses the headwaters of the Mississippi River.

One member of Ginew declared “We’re here today protecting our water, our burial sites and standing in solidarity with our brothers and sisters down south who are fighting the Bayou Bridge Pipeline. The Mississippi River begins here in the headwaters, where we are standing right now, and it ends in the Gulf of Mexico, in the bayous, where folks have been fighting against Energy Transfer Partners (ETP) for months, putting their bodies on the line for clean water and safer communities. We’re fighting Enbridge here, a different company that is also invested in ETP. Enbridge wants to cross over 200 water ways and drill under the Mississippi River multiple times to construct Line 3. Enbridge wants to put this new poisonous black snake where the river begins and turn this area into an industrial corridor. They want to poison our seed of hope for clean water and turn us into another alley of cancer.”

Many of the work trucks bore out of state plates, one indigenous woman pointed to the out of state plates and explained that “Extractive industry impacts indigenous peoples first and worst – the men come into our communities to build these destructive projects and we women face increased risks of violence, harassment, and potentially life-threatening assaults while our native communities are jurisdictionally limited in the right to prosecute offenders.”

Another water protector put it simply. “We will make it clear that indigenous territories are not sacrifice zones, and the tar sands machine must stop. Line 3 is Enbridge’s single largest project in the company’s history, and with the cancellation of Energy East and uncertain financial backing of Kinder Morgan and Keystone XL, this has become a fight that could cripple the industry while changing the narrative of indigenous peoples within mainstream society. Standing Rock planted seeds across Turtle Island and the world, we Anishinaabe in what is now known as Minnesota are prepared to fight and to stand side by side with indigenous and non-indigenous peoples alike in our work.”

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Sep 13, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

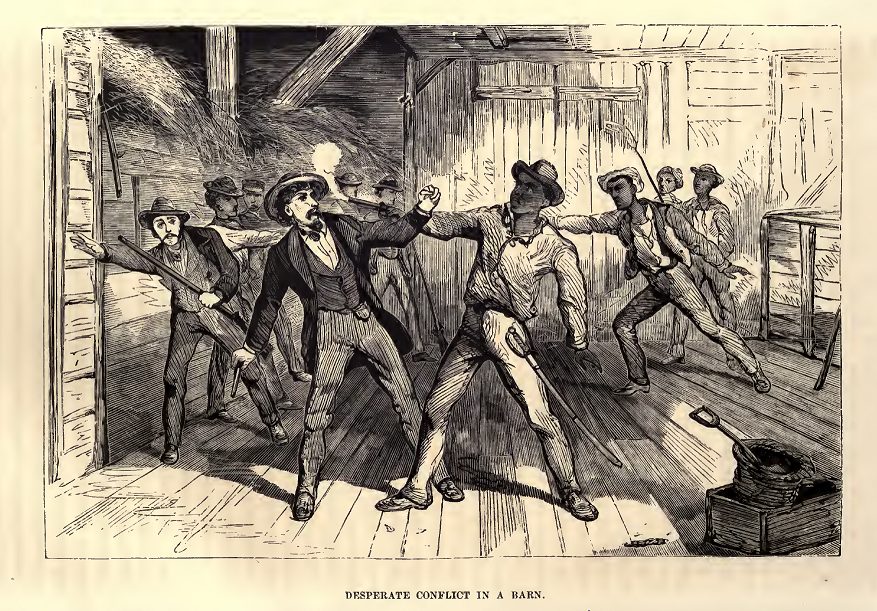

Featured image: Struggle for freedom in a Maryland barn. Engraving from William Still’s The Underground Rail Road

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Introduction to Strategy” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

The Weather Underground was far from the only group that had difficulty implementing necessary tactics. The story of abolitionists prior to the Civil War gives us one of the best examples of this, in part because of the length and breadth of their struggle. Starting from a marginalized position in society, the struggle over slavery eventually inflamed an entire culture and provoked the bloodiest war in American history.

We’ll begin the story in the 1830s when several different currents of antislavery activism were growing rapidly. One of these currents was the Underground Railroad, run by both black and white people. Another current consisted of what you might call liberal abolitionists, predominantly white with a few black participants as well.

The general story of the Underground Railroad has become well-known, but there are many common misconceptions. Black slave escapes date back to the 1500s (when escapes south to Spanish Florida were rather more common), although some aspects of the nineteenth century Railroad were more systematically organized. One common but incorrect belief about the Underground Railroad is that it was run by magnanimous whites in order to aid black people otherwise unable to help themselves. In fact, this revisionist mythology is quite far from the truth.32 Until the 1840s, it was primarily run by and for black people who distrusted the involvement of whites. Escaped blacks were always in much greater danger than whites, and had to possess a great deal of skill, knowledge, and bravery in order to escape. The great majority of escapes were orchestrated by the slaves themselves, who spent months or years planning and reconnoitering escape routes and hiding places. Indeed, some historians have calculated that by the 1850s about 95 percent of escaping slaves were alone or with one or two companions.33

Furthermore, although the Underground Railroad is now recognized as a heroic and important part of the history of slave resistance, not all abolitionists of the time participated. In fact, some actually opposed the Underground Railroad. According to one history, “Abolitionists were divided over strategy and tactics, but they were very active and very visible. Many of them were part of the organized Underground Railroad that flourished between 1830 and 1861. Not all abolitionists favored aiding fugitive slaves, and some believed that money and energy should go to political action.”34

There’s no question that those who participated in the Underground Railroad were very brave, regardless of the color of their skin, and the importance of the Railroad to escaped slaves and their families cannot be overstated. The problem was that the Railroad just wasn’t enough to pose a threat to the institution of slavery itself. In 1830, there were around two million slaves in the United States. But at its peak, the Underground Railroad freed fewer than 2,000 slaves each year, less than one in one thousand. This escape rate was much lower than the rate of increase of the enslaved population through birth. Of course, many fugitive slaves worked to save money and buy their families out of slavery, which meant that the Railroad freed more people than just those who physically travelled it.

Tactical Development: From Moral Suasion to Political Confrontation35

While the Underground Railroad was growing in the 1830s, another antislavery current was growing as well. This one consisted mostly of white abolitionists, driven by Christian principles and a desire to convince slave owners to stop sinning and release their slaves. These early white Christian abolitionists recognized the horrors of slavery, but adopted an approach of pacifist moral exhortation. Historian James Brewer Stewart discusses their approach: “Calling this strategy ‘moral suasion,’ these neophyte abolitionists believed that theirs was a message of healing and reconciliation best delivered by Christian peacemakers, not by divisive insurgents.… They appealed directly to the (presumably) guilty and therefore receptive consciences of slaveholders with cries for immediate emancipation.” They believed, as liberals usually do, that the oppressive horrors perpetrated by those in power were mostly a misunderstanding (rather than an interlocking system of power that rewarded the oppressors for evil). So, of course, they believed that they could correct the mistake by politely arguing their case.

Stewart continues: “This would inspire masters to release their slaves voluntarily and thereby lead the nation into a redemptive new era of Christian reconciliation and moral harmony.… immediate abolitionists saw themselves as harmonizers, not insurgents, because the vast majority of them forswore violent resistance.… ‘Immediatists,’ in short, saw themselves not as resisting slavery by responding to it reactively, but instead as uprooting it by spiritually revolutionizing the corrupted values of its practitioners and supporters.” In other words, they fell prey to four of the strategic failings we’ve discussed so far. They didn’t use asymmetric strategic principles, largely because they weren’t using a resistance strategy at all. They were essentially lobbying, and their “morally superior” approach meant that, as a minority faction, they had no political force to bring to bear on those whom they lobbied. Furthermore, they were hopelessly naïve (or to state the problem more precisely, they were hopefully naïve) about the nature of power and the slave economy. As a result, they were unable to concoct a reasonable A to B strategy. Their so-called strategy, though well-meaning and moral, was more akin to a collective fantasy that overlooked the nature and extent of violence that slave culture would bring to bear on its adversaries.

Stewart recognizes this problem as well. “By adopting Christian pacifism and regarding themselves as revolutionary peacemakers, these earliest white immediatists woefully underestimated the power of the forces opposing them. Well before they launched their crusade, slavery had secured formidable dominance in the nation’s economy and political culture. To challenge so deeply entrenched and powerful an institution meant adopting postures of intransigence for which these abolitionists were, initially, wholly unprepared.”36

Need I spell out the parallels to our current situation? Pick any liberal or mainstream environmental or social justice movement. Mainstream environmentalism has been particularly naïve in this regard, largely ignoring the deeply entrenched nature of ecocidal activities in the capitalist economy, in industry, in daily life, and in the psychology of the civilized. Furthermore, mainstream environmentalists—who often do not come out of a long tradition of resistance—utterly ignore the force that those in power will bring to bear on any threat to that power. By assuming that society will adopt a sustainable way of life if only individual people can be persuaded, mainstream environmentalists ignore the rewards offered for unsustainability, and too often ignore those who pay the costs for such rewards.

Of course, mainstream environmentalism is hardly unique in this. Indeed, this basic trajectory is so common that it is nearly archetypal. Again and again, whenever privileged people have tried to ally themselves with oppressed people, we have seen this phenomenon at work. Seemingly ignorant of the daily violence perpetrated by the dominant culture, many people of privilege have wandered off into a strategic and tactical Neverland, which is based on their own personal wishes about how resistance ought to be, rather than a hard strategy that is designed to be effective and that draws on the experience of oppressed peoples and their long history of resistance. Sometimes the people of privilege listen and learn, and sometimes they don’t.

Of course, these early white abolitionists were on the right side, and, of course, their response to slavery was, morally speaking, far above that of the majority of white people’s. But, writes Stewart: “With the nation’s most powerful institutions so tightly aligned in support of slavery and white supremacy, it is clear that young white abolitionists were profoundly self-deceived when they characterized their work as ‘the destruction of error by the potency of truth—the overthrow of prejudice by the power of love—the abolition of slavery by the spirit of repentance.’ When so contending, they were deeply sincere and grievously wrong. To crusade for slavery’s rapid obliteration was, in truth, to stimulate not ‘the power of love’ and ‘repentance,’ but instead to promote the opposition of not only an overwhelming number of powerful enemies—the entire political system—but also the nation’s most potent economic interests—society’s most influential elites—and a popular political culture in the North that was more deeply suffused with racial bigotry than at previous times in the nation’s history.” This is a lesson we must remember.

They were highly optimistic about their chances. After increasing racial tensions and a series of violent uprisings in the early 1830s, one immediatist predicted that “the whole system of slavery will fall to pieces with a rapidity that will astonish.”37 This attitude is again reminiscent of the excess of hope we discussed earlier.

We should note that it was not just white abolitionists who were opposed to serious resistance at this stage, but some people of color as well. Historian Lois E. Horton writes that one black editor of a newspaper “penned an article addressed ‘To the Thoughtless part of our Colored Citizens,’ in which he admonished readers to act with more dignity and self-restraint when fugitive slaves were captured. [The editor] urged African Americans to leave the defense of fugitives to the lawyers … Public protest, even public assembly, [he] warned, would risk the loss of support from respectable allies. He was especially shocked by the involvement of Black women in this protest, singling them out for ‘everlasting shame’ and charging that they ‘degraded’ themselves by their participation.”38

But more militant abolitionists continued to gain prominence. Former fugitive slave Henry Highland Garnet rejected the pacifism of both white and black abolitionists, saying “There is not much hope of Redemption without the shedding of blood.”

Many white abolitionists retained their pacifist beliefs and practices, but as the abolition movement grew, it was increasingly perceived as a threat by slaveholders and those in power. An escalating wave of violent repression occurred, in which abolitionists and their allies were attacked, and their mailings and offices were burned. Many white abolitionists abandoned pacifism after white newspaper editor and abolitionist Elijah Lovejoy was gunned down in his office by proslavery thugs. William Lloyd Garrison, publisher of the foundational abolitionist paper the Liberator, wrote: “When we first unfurled the banner of the Liberator … we did not anticipate that, in order to protect southern slavery, the free states would voluntarily trample under foot all law and order, and government, or brand the advocates of universal liberty as incendiaries and outlaws.… It did not occur to us that almost every religious sect, and every political party would side with the oppressor.”39 Of course, they did not consider and dismiss the idea—it simply didn’t occur to them. This repression did, however, induce increasing numbers of Northerners to join with the abolitionists out of concern for the violations of law by the government and antiabolitionists.

The good news was that by the 1850s, more and more abolitionists were defying fugitive slave laws and even taking up arms to aid escaped slaves inside and outside of the Underground Railroad. Violent confrontations began to occur in a scattershot fashion or, to be more precise, defensive violence carried out by abolitionists became more common, since slavery had been based on violent confrontations since the beginning, and none of that was new to black people. It was soon not unheard of in the North for slaveholders or slave catchers to be shot—on one occasion in Boston in 1854, a crowd even stormed a courthouse where a fugitive slave was being held and overpowered the guards. Writes Stewart, “And even when physical violence did not result … oratorical militants increasingly urged their audiences to resort to physical destruction if more peaceable methods failed to stop federal slave catchers. On several occasions well-organized groups of abolitionists overwhelmed the marshals and spirited fugitives to safety. At other times they stored weapons, planned harassing manoeuvres, and massed as intimidating mobs.”40 Though only a decade earlier they were taking oaths never to use force, white abolitionists came to agree that use of lethal force against slave catchers, in self-defense, was morally justified. Armed defiance of slave catchers was a long tradition for black activists at that time, but a considerable change for white abolitionists. Many Christian abolitionists changed their tactics, arguing that not only was pacifism not required by God, but that it was a Christian’s duty and the “Law of God” to shoot a slave catcher.