by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Aug 25, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

Editor’s note: This is an edited transcript of a presentation given at the 2016 Public Interest Environmental Law Conference by DGR’s Dillon Thomson and Jonah Mix on the failure of the contemporary environmental movement to meaningfully stop the destruction of the planet. Using examples from past and current resistance movements, Mix and Thomson chart a more serious, strategic path forward that takes into account the urgency of the ecological crises we face. Part 2 can be found here, and a video of the presentation can be found here.

For the past several thousand years, this beautiful planet has been the site of a dysfunctional relationship between civilization, the way of life characterized by the emergence and growth of cities, and the more-than-human communities that it exploits. For the vast majority of our time on earth, humans fit into the logic of whatever land base we happened to inhabit. We watched and listened, we felt, and we communicated with the land to maintain a mutually beneficial relationship. This created the conditions for our long-term survival.

Living examples of this older way of life still exist. Small-scale subsistence cultures have lived in place for thousands, if not hundreds of thousands of years. Among these are the Bushmen of the Kalahari Desert, the Kawahiva of the Brazilian Amazon, the Kogi of the Sierra Nevada Mountains of Columbia, and the people of the Nilgiri Hills in India. To this day, subsistence culture is the only time-tested mode of human sustainability on this planet. It is also the way of life that is being destroyed the fastest by civilization.

Civilization, which began just over ten thousand years ago in the Fertile Crescent, marks the beginning of a fundamentally different way of relating to the planet. The human element began to impose its own logic over the logic of the land. Before, human culture had been an extension of an ecosystem. Now we see our culture as separate from nature, a value system opposed to the principles and the workings of nature.

Ever since the emergence of civilization, life on earth has suffered. That’s how we know that the relationship is dysfunctional. Every living system on the planet is in decline, and the rate of decline is accelerating. Not a single peer-reviewed scientific article published in the last thirty years contradicts this statement. You shall know a tree by its fruit, and by its fruit, industrial civilization stands condemned. Or at least it should.

The fruits of civilization are the drawdown of living systems and natural vitality. We must analyze the values and behaviors that have oriented this culture against the planet.

Why should civilization stand condemned? First of all, it commits the cardinal sin: it does not benefit the land on which it is based. All beings and communities must benefit the land where they live in order to survive long-term. That is basic ecology. You have to give back as much or more than you take. Civilization is like a bad houseguest. It takes far more than its fair share and what it gives back is toxic and inedible. It values production over life. To civilization, the needs of the economic system outweigh the needs of the natural world.

The natural world can thrive without an industrial economy, but no human economy can exist without a healthy natural world. It’s embarrassing that this point must be made, but if you look at our culture’s behavior or listen to the talking heads on the radio or TV, you can quickly see we value our economic system above all else.

Our way of life requires widespread violence. This culture would quickly collapse without astounding violence against the earth, non-human communities, and members of our own species. How many people are aware that there are over 27 million human slaves today? The industrial supply chain enslaves more people today than any other period in human history.

You find slavery alive and well in the cotton in your shirt, the tantalum in your cellphone, and the beans in your cup of coffee. It is in the mines, the fields, and the raw materials processing that we don’t have to see because of our position in the supply chain. We are at the end, the “capital C” Consumers.

Professor Kevin Bales arrived at that 27 million number, which he calls the most conservative estimate for the number of slaves in the world today. It accounts for people who are forced into slavery at gunpoint and kept there by threat of direct violence to them or their families. It does not include millions more wage slaves, sweatshop laborers, and people coerced into slave-like conditions through economic hardship, usually at the hands of predatory multinational corporations.

Sweatshop, China

Our culture’s stories say that humans have the right to control and abuse the natural world. This is an issue of entitlement. Our culture feels that we are entitled to rip the tops off mountains, extract bauxite, turn it into aluminum, and make beer cans. Our culture thinks it is okay to torture animals in vivisection labs in order to make shampoo. Our culture thinks that we can exempt ourselves from the natural cycles of life and death. It believes in infinite growth on a finite planet. Our culture behaves as if it can destroy the planet and live on it too.

Violence is part of our culture and has been from the very beginning. It is part of the fabric of civilization and the fabric of our economy. Why? In part, this is due to the economic reward. Violence feeds the bottom line of business.

I have been calling the relationship between civilization and the planet dysfunctional, but it is more like a one-sided war. This goes far beyond disrespect. The behavior of this culture constitutes a form of hatred that is akin to hatred of one’s own flesh. Those who suffer the consequences of civilization are our kin, our family. How can a culture commit atrocity after atrocity against the earth and not hold a deep hatred of the natural world at its core?

In The Culture of Make Believe, Derrick Jensen writes, “Hatred felt long enough no longer feels like hatred, it feels like economics, it feels like religion, it feels like tradition.” This is hatred of our larger earth-body, our larger self, and our sense of self based upon this hatred is no more sustainable than our economy. The cultural stories that we inherit do not tell us that our flesh is continuous with the flesh of the world. Our stories don’t tell us that we are kin with the oak tree, the jaguar, and the soil.

Though scientists understand that everything is connected on a molecular level, most of their research is pressed into the service of extractive industry. Science’s stories have not led to a mutually beneficial relationship with the land. Most of the stories we receive are stories of separation. We can go back to Rene Descartes: “I think, therefore I am.” Descartes created an artificial division between mind and matter that persists today.

The stories we inherit are stories of human supremacy. They tell us that we are superior to all other life forms and that we have the right to act accordingly.

We are animals among animals. The beings and communities that we are pushing to extinction are not inferior. They are not resources and they do not exist for our use and exploitation. This is a message to the animal in all of you: this is war. Civilization has been at war with the earth for 12,000 years. This is a call to those who want to fight back strategically against civilization – and win.

The environmental movement was created to deal with the dysfunctional relationship between civilization and the natural world. It can be traced back to different starting points. Many people say that the contemporary environmental movement in the West has its roots in the Romantic movement of the 18th century. The conservation movement came in the 19th century. In the 20th century came Aldo Leopold’s land ethic, described in A Sand County Almanac. In 1962, Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring brought even greater visibility to the environmental movement.

Though it’s been more than fifty years since 1962, every living system on the planet is in decline. This decline is accelerating. Why? Many environmental groups have done good work here and there, but by and large, the environmental movement has remained a defensive movement. Our losses are permanent and our victories are often defensive and temporary. We may save a patch of forest for a few years or decades – until it gets cut down. We may save a river or watershed – until they are poisoned.

Rosa Durando lives in Florida, where she is a member of the Palm Beach Audubon Society, the County Land Use Advisory Board, the Citizens Task Force on Zoning, and the countywide Council on Beaches and Shores. She has been a full-time environmentalist worker-watchdog for the past ten years. She says, “Sometimes I feel like a total failure. Other times I tell myself I’ve done well by getting concessions. I don’t think any environmentalists are really successful. The other side is too powerful and too rich. The best we can hope for are safeguards to avoid total destruction next year.”

Durando is one of the honest few among us who speak about the uphill battle of land defense work. The one point I disagree with is that the best we can hope for is to avoid total destruction next year. DGR thinks that there is another path forward to stop the destruction entirely.

Strategies in war include both defense and offense. Defense is anything that prevents an opposing force from gaining territory, power, or resources. Maybe a developer wants to clear-cut one hundred acres of old-growth forest. You take him to court and fight to save half the land. That defensive action is valuable and good; we need everyone working as hard as they can to do things like that. In the end, though, the developer still gets fifty acres. The best possible outcome of a defensive action is that things stay the same. You cannot win a war through defense alone. This is where offensive action comes in.

Offensive action directly takes territory, resources, or power from the opposition. 99% of what industrial civilization does is offensive. It dams rivers and strip-mines mountains. It rounds up African Americans and throws them in jail. It rapes women and commits genocide. Every time the system acts it gains power, territory, or resources. With few exceptions, the system doesn’t act defensively. Without serious opposition, it doesn’t have to.

On the flipside, the environmental movement is too busy fighting defensive battles to focus on offensive gains. The contemporary environmental movement cannot conceive of an offensive campaign against ecocide. This isn’t a recipe for victory. Marjory Stoneman Douglas, one of my heroes, said, “When developers win a battle, it’s in concrete. When environmentalists with a battle, it’s only for thirty days.”

Marjory Stoneman Douglas, champion of the Florida Everglades

This quote captures the heart of the matter. The developers fight offensive battles. They are gaining territory and holding onto it. Environmentalists fight defensive battles. At best we are delaying their forward march. To be clear, we are not doing this because we are stupid, lazy, or unwilling to take risks. We’re doing it because we are up against a massive system with guns, bombs, and jails. It controls the nightly news, talk radio, schools, and everything else that prevents the environmental movement from doing more than slowing it down.

Most of us don’t have anything but a few bucks, some picket signs, our bodies, and a love for the living planet. There are strategies that not only address that inequality but also leverage it in an offensive and effective approach. One of my favorite quotations is from Malcolm X: “If you stick a knife in my back nine inches and pull it out six inches, there’s no progress. If you pull it all the way out, that’s not progress. Progress is healing the wound that the blow made.”

Malcolm X was speaking about the wound that white America and white people had inflicted on Africans, but his words also describe our violence against the earth. Slowing this violence isn’t progress; even stopping it isn’t progress. Progress would be healing the wound that the blow made. Our enemy is industrial civilization. It’s not capitalism, corporations, or even fossil fuels. These things must be done away with, but they are all expressions of a deeper problem. To end the destruction of the living world, we have to end industrial civilization itself.

Like every system, industrial civilization has two components: its structure and its values. “Structure” describes the real-world, material things that make up a system. “Values” describes the ideology invented to defend that system.

The structure of industrial civilization is clear. It includes the energy grid, extraction infrastructure, communications infrastructure, financial systems, and technology industry. All of these components work toward one of three goals: accessing resources, extracting resources, or processing resources to make them usable for industrial civilization. Everything from clear-cuts and strip-mines to police violence, genocide, and rape is about the control of resources.

Our resistance has to focus on stopping the control, extraction, and processing of resources by industrial civilization. At the center of these processes is the energy grid. Without the energy grid, you can’t spin the drills that kill mountains, run the computers that decide where the murdered mountains go, or keep the lights on in the buildings that take the murdered mountains and turn them into our cell phone batteries. Without power provided by an energy grid, industrial civilization has nothing.

Next is the extraction infrastructure, the part of the system that seizes resources. “Resources” refers to bodies, bones, and blood, living and breathing creatures – the living planet. Extraction infrastructure seizes them and grinds them up. Mining, logging, fracking, refining, and wind and solar energy are all are part of this infrastructure. Extraction infrastructure is organized by communications infrastructure, which includes phone lines, cell towers, and the internet.

Extraction and communications rely on the financial system that keeps capital flowing so that multinational corporations can invest in extraction processes. The technology industry makes extraction more efficient. The systems that enable industrial civilization are interconnected and codependent. The energy grid needs the technology industry, which needs communications. Extraction needs the energy grid and financial systems. Each system depends on the others.

In looking at this structural complexity, it is important to remember that it makes up only one component of industrial civilization. Civilization also relies on values, ideology, and stories to justify its actions. At the core of these stories is the value that industrial civilization prizes above all else: growth.

Endless expansion requires three conditions: hierarchy, stability, and efficiency. Hierarchy is the ranking of lives and communities. Industrial civilization needs hierarchy because a free and egalitarian social system would make endless expansion impossible. White supremacy, patriarchy, and human supremacy are myths central to industrial civilization because they justify the exploitation of Africans, indigenous people, Latinas and Latinos, women, and the more-than-human world.

Stability ensures a steady baseline upon which a system can expand. To cultivate stability, industrial civilization encourages comfort and ignorance. When people have refrigerated food and five hundred channels on TV, we don’t see the destruction around us – or care about it. That doesn’t mean that everyone inside industrial civilization is comfortable or ignorant. Largely, the people who are comfortable and ignorant are those at the top. Those at the bottom – the non-human world, people of color, and women – are largely aware of the violence that the system perpetrates in their lives. To stymie resistance, then, the system works to control all avenues for education and confrontation.

Finally, efficiency enables more expansion. The myth of consumerism teaches that as people buy more, the markets grow, production increases, and more production equals more growth.

The progress myth teaches that human beings arose in a state of primitivism, stupidity, and weakness – and that we are moving toward a grander design. We achieve that grander design by destroying the world around us.

Human beings aren’t moving toward a grander design any more than pigs, centipedes, or whales are moving toward a grander design. No one talks about the day when pigs or centipedes will seize control of the planet and make it better for pigs or centipedes. We like to believe the progress myth because without it, you can’t justify the destruction of the earth. This is where our culture’s love of science comes in. Advanced science is necessary to make superconductors, defoliants, and everything else that kills the planet.

Effective resistance to a system requires that you reject its values and attack its structures. It can never take place on the system’s terms. It can never leave the structure of the system in place. If there is one single flaw holding the modern environmental movement back, it’s our inability to stand firm against more than one aspect of the system at a time.

For example, I used to live in Bellingham, Washington. Bellingham is a major site of controversy over coal trains. Extraction infrastructure murders mountains across the country, packs them into trains, and carries them to the ports in Bellingham. From there they are shipped up to Vancouver and across the ocean to China to keep the lights on in factories where children sew our shoes. Smart, brave people fought back against the coal trains. But what would it talk to attack the entire extraction infrastructure?

Let’s say you defend the structure and retain the values. You call up the company that owns the port and say, “Hey, I only want union labor to unload the coal.” They probably wouldn’t listen to you, but let’s say you succeed. Unions are great, but you haven’t attacked the structure. The coal is still flowing. More importantly, you haven’t rejected the system’s values because you’ve adopted as a given that human beings have the right to ship coal at all.

Let’s say you want to attack the structure. You call up your congressperson or representative and demand that they replace coal trains with wind farms and solar panels. Again, they probably wouldn’t listen, but with enough pressure, you might slow down coal exports – and that’s great. You’ve made a hit against the structure – on the assumption that wind farms, solar panels, or electricity are justified. The system can pat you on the back and promise not to rely on coal so heavily. Then it can strip-mine a mountain, dam a river, kill just as many living creatures, and sell you a “renewable” product. The system took a hit, but with its values untouched, it recovered quickly.

If you want to reject the values of the system, you could sell your car, move into a smaller house, grow your own food, or sew your own clothes. You could condemn the entire system of industrial civilization. You could drop out and be very vocal about it – and that’s great. Even if you’ve rejected the values, though, the coal trains keep rolling. The structure remains intact.

How could one strike at coal trains in a way that rejects the concept of coal trains, wind farms, solar panels, or electricity itself? How could one do damage not only to the structure but also to the ideology that justifies it? You could take a blowtorch, crowbar, or some dynamite and destroy the rail line. Suddenly the coal trains aren’t going anywhere. More importantly, the system can’t recover on its own terms.

Loaded coal trains, Norfolk, VA, USA

Remember, industrial civilization values expansion, comfort, hierarchy, and efficiency. If you condemn coal trains because they’re wasteful and solar is more efficient, or because coal trains are noisy and solar is quiet, or because coal trains clog up transportation and solar power eliminates congestion, that’s great. The system wants efficiency. It wants comfort, so it will happily replace coal trains with something more efficient, quieter, less disruptive, and still fundamentally destructive to the earth.

But if you strike against coal trains because the very idea of a living planet is incompatible with electricity, coal trains, wind farms, or anything else that destroys the earth, you’ve given the system an ultimatum that it can’t easily escape. This is all hypothetical; I’m not telling you to blow up or destroy anything. The point isn’t that successful resistance requires bombs, it’s that it requires a hard stance against the system in its entirety. The values of industrial civilization and the values of a healthy culture that is capable of living in communion with the earth are incompatible. By pushing that contradiction instead of capitulating to the system’s values, we can strengthen our cause.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Aug 20, 2018 | Lobbying

Featured image: Wangan and Jagalingou cultural leader Adrian Burragubba visits Doongmabulla Springs in Australia. The Wangan and Jagalingou are fighting a proposed coal mine that would likely destroy the springs, which are sacred to the Indigenous Australian group.

by Noni Austin / Ecowatch

For tens of thousands of years, the Wangan and Jagalingou people have lived in the flat arid lands of central Queensland, Australia. But now they are fighting for their very existence. Earlier this month, they took their fight to the United Nations after years of Australia’s failure to protect their fundamental human rights.

A company called Adani Mining Pty Ltd, part of the Adani Group of companies founded by an Indian billionaire named Gautam Adani, is determined to build the massive Carmichael Coal Mine and Rail Project on the Wangan and Jagalingou’s ancestral homelands. If built, the Carmichael Coal Mine would be among the largest coal mines in the world, with six open-cut pits and five underground mines, as well as associated infrastructure like rail lines, waste rock dumps and an airstrip.

Coals mine are immensely destructive: The Carmichael mine would permanently destroy vast areas of the Wangan and Jagalingou’s ancestral homelands and waters, and everything on and in them—sacred sites, totems, plants and animals. It would also likely destroy the Wangan and Jagalingou’s most sacred site, Doongmabulla Springs, an oasis in the midst of a dry land. The development of the mine would also result in the permanent extinguishment under Australian law of the Wangan and Jagalingou’s rights in a part of their ancestral homelands.

The Wangan and Jagalingou’s lands and waters embody their culture and are the living source of their customs, laws and spiritual beliefs. Their spiritual ancestors—including the Mundunjudra (Rainbow Serpent), who travelled through Doongmabulla Springs to shape the land—live on their lands.

As Wangan and Jagalingou authorized spokesperson and cultural leader Adrian Burragubba said, “Our land is our life. It is the place we come from, and it is who we are. Plants, animals and waterholes all have a special place in our land and culture and are connected to it.”

Consequently, the destruction of the Wangan and Jagalingou’s lands and waters is the destruction of their culture. If their lands are destroyed, they will be unable to pass their culture on to their children and grandchildren, and their identity as Wangan and Jagalingou will be erased.

Murrawah Johnson, authorised youth spokesperson of the Wangan and Jagalingou, said, “In our tribe, women teach our stories to our young people. I want my children and their children to know who they are. And if this mine proceeds and destroys our land and waters, and with it our culture, our future generations will not know who they are. Our people and our culture have survived for thousands of years, and I cannot allow the Carmichael mine to destroy us. I will not allow myself to be the link in the chain that breaks.”

The Wangan and Jagalingou have consistently and vehemently opposed the Carmichael mine, rejecting an agreement with Adani Mining on four occasions since 2012. Throughout its dealings with the Wangan and Jagalingou, Adani Mining has used the coercive power of Australian legislation and acted in bad faith, holding fraudulent meetings and manipulating the Wangan and Jagalingou’s internal decision-making processes.

In these circumstances, the development of the Carmichael mine violates the Wangan and Jagalingou’s internationally protected human rights, including the right to continue practicing their culture and to use and control their ancestral homelands, as well as the right to be consulted in good faith and to give or withhold their consent to mining projects on their lands.

Despite the Wangan and Jagalingou’s persistent objections and their pleas to the Australian and Queensland governments to protect their human rights, both governments have approved the mine and publicly support it, and Adani Mining remains steadfastly determined to develop the project as soon as possible. The Wangan and Jagalingou have also brought litigation in Australia to protect their homelands, but have been unsuccessful to date because Australian law allows private companies and the government to override the Wangan and Jagalingou’s rights in their ancestral lands.

Now, to protect their fundamental human rights, the Wangan and Jagalingou have been forced to seek help from a United Nations human rights watchdog. Recently, the Wangan and Jagalingou asked the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination to urgently ensure Australia protects their homelands and culture. The committee is the enforcement body of the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, a treaty Australia has signed. The convention is one of the core international treaties among the world’s nations that protect our most basic human rights, including Indigenous peoples’ rights to culture and land.

If Australia will not listen to its own people, the Wangan and Jagalingou hope it will listen to international community and cease prioritizing the profits of a foreign company over the permanent loss of a people who have been connected to the land since time immemorial.

Earthjustice assisted the Wangan and Jagalingou to prepare their request for urgent action to the UN.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Aug 18, 2018 | Lobbying

Featured image: Great Basin National Park from Spring Valley, Nevada

by Great Basin Water Network

Ely, Nevada: A broad coalition of Nevadans committed to protecting the state’s water resources are declaring victory in their opposition to the SNWA groundwater pipeline. They applaud a ruling by the Nevada State Engineer denying all water rights applications for the project.

Great Basin Water Network and White Pine County say the decision is essentially a death-knell for the roughly 300-mile pipeline proposal. These groups oppose SNWA’s proposed groundwater export and pipeline project because it would cause catastrophic long term environmental harm to some of Nevada’s most pristine and treasured areas, and because it would cause long-term economic devastation to rural communities throughout eastern Nevada. Following favorable decisions in Nevada’s District and Supreme Courts, it appears that the Nevada State Engineer agrees.

“With the denial of these applications by the State Engineer, this ill-conceived multibillion dollar boondoggle is now dead in the water,” said Abigail Johnson of the Great Basin Water Network. “After a string of court victories, we have a decision showing that the water is not available for this project without hurting the area’s existing water rights and environment.”

“We welcome the State Engineer’s denial of SNWA’s applications, which clearly was required by Nevada water law, as the State District Court and Supreme Court have explained,” said the coalition’s attorney, Simeon Herskovits of Advocates for Community and Environment. “We do, however, disagree with the State Engineer’s gratuitous finding that SNWA’s monitoring, management and mitigation (or 3M) plan is adequate. Their slightly elaborated 3M plan remains as much of a sham as it always has been,” Herskovits added.

“White Pine County residents and rural Nevadans are glad that the limits of available groundwater resources have been acknowledged,” declared White Pine County Commissioner Gary Perea. “The denial of SNWA’s applications finally recognizes that, if allowed, the project would take more water than the system could bear, hurting existing water rights and the economies that depend on them.”

“We will continue to stand up and ensure that the State Engineer and SNWA follow the law, and protect our water rights and resources from overpumping and irreversible harm,” agreed another White Pine County Commissioner, Carol McKenzie, from Lund.

Kena Gloeckner, whose family has been ranching in Lincoln County’s Dry Lake Valley – a target of the project – for many generations, said “Not only would this groundwater project have jeopardized our family’s 150-year-old legacy and livelihood, but it would have also ended a way of life valued by local residents. Ranchers and farmers on the ground have long known that the aquifers in these rural valleys are interconnected and are at or near their limits – there is simply nowhere near the amount of water that SNWA wanted to take.”

Read more about the SNWA pipeline at DGR Southwest Coalition

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Aug 11, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Introduction to Strategy” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

It’s also worth looking at the principles that guide strategic nonviolence. Effective nonviolent organizing is not a pacifist attempt to convince the state of the error of its ways, but a vigorous, aggressive application of force that uses a subset of tactics different from those of military engagements.

Gene Sharp recognized this, and Peter Ackerman and Christopher Kruegler followed Sharp’s strategic tradition in their book Strategic Nonviolent Conflict: The Dynamics of People Power in the Twentieth Century. They understand that there is no dividing line between “violent” and “nonviolent” tactics, but rather a continuum of action. Furthermore, they also understand the need for tactical flexibility; sticking to only one tactic, such as mass demonstrations, gives those in power a chance to anticipate and neutralize the resistance strategy. In terms of strategy, they argue “that most mass nonviolent conflicts to date have been largely improvised” and could greatly benefit from greater preparation and planning.5 I would argue that the same applies to any resistance movement, regardless of the particular tactics it employs.

Having assessed the history of nonviolent resistance strategy in the twentieth century, Ackerman and Kruegler offer twelve strategic principles “designed to address the major factors that contribute to success or failure” in nonviolent resistance movements. They class these as principles of development, principles of engagement, and principles of conception.

Their principles of development are as follows:

Formulate functional objectives. The first principle is clearly important in any resistance movement using any tactics. “All competent strategy derives from objectives that are well chosen, defined, and understood. Yet it is surprising how many groups in conflict fail to articulate their objectives in anything but the most abstract terms.”6

Ackerman and Kruegler also observe that “[m]ost people will struggle and sacrifice only for goals that are concrete enough to be reasonably attainable.” As such, if the ultimate strategic goal is something that would require a prolonged and ongoing effort, the strategy should be subdivided into multiple intermediate goals. These goals help the resistance movement to evaluate its own success, grow support and improve morale, and keep the movement on course in terms of its overall strategy. This is especially important when the dominant power structure has been in control for a long time (as opposed to a recent occupier). “The tendency to view the dominant power as omnipotent can best be undermined by a steady stream of modest, concrete achievements.”7 This is especially relevant to groups that have very large, ambitious goals like abolishing capitalism, ending racism, or bringing down civilization.

Develop organizational strength. Ackerman and Kruegler write that “to create new groups or turn preexisting groups and institutions into efficient fighting organizations” is a key task for strategists.8 They also note that the “operational corps”—who we’ve been calling cadres—have to organize themselves effectively to deal with threats to organizational strength, specifically “opportunists, free-riders, collaborators, misguided enthusiasts who break ranks with the dominant strategy, and would-be peacemakers who may press for premature accommodation.”9 These threats damage morale and undermine the effectiveness of the strategy.

Secure access to critical material resources. They identify two main reasons for setting up effective logistical systems: for physical survival and operations of the resisters, and to enable the resistance movement to disentangle itself from the dominant culture so that various noncooperation activities can be undertaken. “Thought should be given, at an early stage, to controlling sufficient reserves of essential materials to see the struggle through to a successful conclusion. While basic goods and services are used primarily for defensive purposes, such other assets as communications infrastructure and transportation equipment form the underpinnings of offensive operations.”10 In particular, they suggest stockpiling communications equipment.

Cultivate external assistance. The benefits of cultivating external assistance and allies should be clear. Combating an enemy with global power requires as many allies and as much solidarity as resisters can rally.

Expand the repertoire of sanctions. The fifth principle is key because it is highly transferable. By “expand the repertoire of sanctions,” they simply mean to expand the diversity of tactics the movement is capable of carrying out effectively. They also encourage strategists to evaluate the risk versus return of various tactics. “Some sanctions can be very inexpensive to wield or can operate at very low risk. Unfortunately, such sanctions may also have a correspondingly low impact. A minute of silence at work to display resolve is a case in point. Other sanctions are grand in design, costly, and replete with risk. They also may have the greatest impact.”11

Their second group of principles consists of principles of engagement:

Attack the opponents’ strategy for consolidating control. This is specifically intended for mass movements, but essentially the authors mean to undermine the control structure of those in power, to generally subvert them, and to ensure that any repression or coercion those in power attempt to carry out is made difficult and expensive by the resistance.

Mute the impact of the opponents’ violent weapons. “The corps [or cadres] cannot prevent the adversaries’ deployment and use of violent methods, but it can implement a number of initiatives for muting their impact. We can see several ways of doing this: get out of harm’s way, take the sting out of the agents of violence, disable the weapons, prepare people for the worst effects of violence, and reduce the strategic importance of what may be lost to violence.”12 These options—mobility, the use of intelligence for maneuver, and so on—are basic resistance approaches to any attack by those in power, and not limited to nonviolent activists.

Alienate opponents from expected bases of support. Ackerman and Kruelger suggest using “political jiujitsu” so that the violent actions of those in power are used to undermine their support. Of course, we could extend this to generally undermining all kinds of support structures that those in power rely on—social, political, infrastructural, and so on.

Maintain nonviolent discipline. Interestingly, the key word in their discussion seems to be not “nonviolence,” but “discipline.” “Keeping nonviolent discipline is neither an arbitrary nor primarily a moralistic choice. It advances the conduct of strategy.”13 They compare this to soldiers in an army firing only when ordered to. Regardless of what tactics are used, it’s clear that they should be used only when appropriate in the larger strategy.

Their third and final group is the principles of conception:

Assess events and options in light of levels of strategic decision making. Planning should be done on the basis of context and the big picture to identify the strategy and tactics used. Often, as we have discussed, this is simply not done. The failure to have a long-term operational plan with clear steps makes it impossible to measure success. “Lack of persistence, a major cause of failure in nonviolent conflict, is often the product of a short-term perspective.”14

Adjust offensive and defensive operations according to the relative vulnerabilities of the protagonists. Strategists need to analyze and fluidly react to the changing tactical and strategic situation in order to shift to offensive or defensive postures as appropriate.

Sustain continuity between sanctions, mechanisms, and objectives. There must be a sensible continuum from the goals, to the strategy, to the tactics used.

There are clearly elements of this that are less appropriate for taking down civilization. For reasons we’ve already discussed—lack of numbers chief among them—a strategy of strict nonviolence isn’t going to succeed in stopping this culture from killing the planet. And there are many things about which I would disagree with Ackerman and Kruegler. But they aren’t dogmatic in their approach; they view the use of nonviolence (which for them includes sabotage) as a tactical and strategic measure rather than a purely moral or spiritual one. What I take away from their principles—and what I hope you’ll take away, too—is that effective strategy is guided by the same general principles regardless of the particular tactics it employs. Both require the aggressive use of a well-planned offensive. Strategy inevitably changes depending on the subset of tactics that are relevant and available, and a strategy that does not employ violent tactics is simply one example of that. The main strategic difference between resistance forces and military forces in history is not that military forces use violence and resistance forces don’t, but that military officers are trained to develop an effective strategy, while resistance forces too often simply stumble along toward a poorly defined objective.

How would a resistance movement expand from hampering to decisively dismantling industrial civilization’s systems of power? What can we learn from history?

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jul 27, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Introduction to Strategy” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

Despite the limitations created by their smaller numbers, resistance movements do have real strategic choices, from the loftiest overarching strategy to the most detailed tactical level. Let’s explore beyond the default palette of actions. Resisters can and must do far better than the strategy of the status quo.

There is a finite number of possible actions, and a finite amount of time, and resisters have finite resources. There are no perfect actions. Prevailing dogma puts the onus on dissenters to be “creative” enough to find a “win-win” solution that pleases those in power and those who disagree, that stops the destruction of the planet but permits the continuation of business as usual and lifestyles of conspicuous consumption. If resisters fall prey to this belief, if they accept its absurd and contradictory premises, they are engineering their own defeat before the fact. If resisters believe this, they are accepting all blame for the actions of those in power, accepting that the problems they face are theirfault for not being “innovative” enough, rather than the fault of those in power for deliberately destroying the world to enrich themselves.

At the highest strategic level, any resistance movement has several general templates from which to choose. It may choose a war of containment, in which it attempts to slow or stop the spread of the opponent. It may choose a war of disruption, in which it targets systems to undermine their power. It may choose a war of public opinion, by which to win the populace over to their side. But the main strategy of the left, and of associated movements, has been a kind of war of attrition, a war in which the strategists hope to win by slowly eroding away the personnel and supplies of the other side, thus wearing down the omnicidal power structures and public opposition to change more quickly than those forces can destroy our communities, more quickly than they can gobble up biodiversity, more quickly than they can burn the remaining fossil fuels. Of course, this strategy has been an abysmal failure.

A strategy of attrition only works when there is an indefinite amount of time to maneuver, to prolong or delay conflict. Obviously that’s not the case in the current situation, which is urgent and worsening. Furthermore, to achieve success in a war of attrition, the resistance must be able to wear down the enemy more quickly than it gets worn down; again, in the present case, those in power are not being worn down at all (except in the degree to which they are so rapidly consuming the commodities required for their own reign to continue).

Furthermore, a resistance movement fighting a war of attrition must reasonably expect that it will be in a better strategic position in the future than it is at the current time. But who genuinely believes that we—however you would define “we”—are moving toward a better strategic position? And in order to get ahead in a war of attrition, resisters would have to have more disposable resources than their opponent.

Another crucial element in a war of attrition is reliable recruitment and growth. It doesn’t matter how many enemy bridges a group takes out if the adversary can build them faster than they can be destroyed. And on every level, civilization is recruiting and growing faster than resistance forces. To keep pace, resistance fighters would have to destroy dams more quickly than they are built, get people to hate capitalism faster than children are inculcated to love it, and so on. So far, at least, that’s not happening.

Of course, we are not in a two-sided war of attrition. Those in power aren’t holding back, but have been actively attacking. And those in the resistance haven’t even been fighting a comprehensive war of attrition; it’s more like a moral war of attrition. Rather than trying to erode the material basis of power, we’ve been hoping that eventually they’ll run out of bad things to do, and perhaps then they’ll come around to our way of thinking.

A movement that wanted to win would be smarter and more strategic than that. It would abandon the strategy of moral attrition. It would identify the most vulnerable targets those in power possess. It would strike directly and decisively at their infrastructure—physical, economic, political—and do it while there is still a planet left.

Strategy and tactics form a continuum; there’s no clear dividing line between them. So the tactics available, which will be discussed in the next chapter, Tactics and Targets, guide strategy, and vice versa. But strategy forms the base. If resistance action is a tree, the tactics are spreading branches and leaves, finely divided and numerous, while the strategy is the trunk, providing stability, cohesion, and rootedness. If resisters ignore the necessity and value of strategy, as many would-be resistance groups do—they are all tactics, no strategy—then they don’t have a tree, they have loose branches, tumbleweeds blowing this way and that with changing winds.

Conceptually, strategy is simple. First understand the context: where are we, what are our problems? Then, develop the goal(s): where do we want to be? Identify the priorities. Now figure out what actions are needed to get from point A to point B. Finally, identify the resources, people, and specific operations needed to carry out those activities.

Here’s an example. Let’s say you love salmon. Here’s the context: salmon have been all but wiped out in North America, because of dams, industrial logging, industrial fishing, industrial agriculture, the murder of the oceans, and global warming. The goal is for the salmon population not only to stop declining, but to increase. The difference between a world in which salmon are being wiped out, and one in which they are thriving, comes down to those six obstacles. Overcoming them would be the priority in any successful strategy to save the salmon.

What actions must be taken to honor this priority? Remove the dams. Stop industrial forms of logging, fishing, and agriculture. Stop the massive production and dumping of plastics. Stop global warming, which means stop the burning of fossil fuels. In all these cases, existing structures and practices have to be demolished for salmon to survive, for the goal to be accomplished.4

Now it’s time to proceed to the operational and tactical side of this strategy. According to the US Army field manual, all operations fit into one of three “all encompassing” categories: decisive, sustaining, or shaping.

Decisive operations “are those that directly accomplish the task” or objective at hand. In our salmon example, a decisive operation might be taking out a dam or preventing a clear-cut above a salmon spawning stream. Decisive operations are the centerpiece of strategy.

Sustaining operations “are operations at any echelon that enable shaping and decisive operations” by offering direct support to those other operations. These supporting operations might include funding or logistical support, communications, security, or other aid and services. In the salmon example, this might mean providing transportation to people taking out a dam, bringing food to tree-sitters, or helping to research timber sale appeals. It might mean running an escape line or safehouse, or providing prisoner support.

Shaping operations “create and preserve conditions for the success of the decisive operation.” They alter the circumstances of the conflict and help bring about the conditions required for victory. Shaping operations could include carrying out a campaign on the importance of removing dams, undermining a particular logging company, or helping to develop a culture of resistance that values effective action and refuses to collaborate. However, shaping operations are not necessarily broad-based or indirect. If an allied underground cell were to attack a nearby pipeline as a distraction, allowing the main group to take out a dam, that diversionary measure would be considered a shaping operation. The lobby effort that created the Clean Water Act could even be considered a shaping operation, because it helps to preserve the conditions necessary for victory.

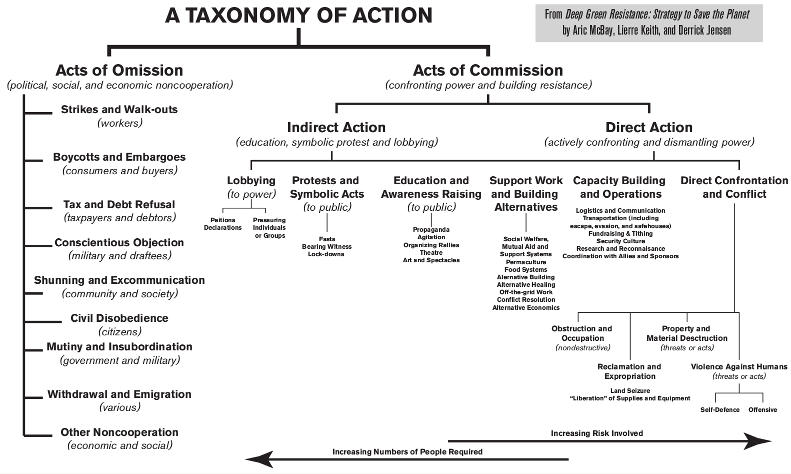

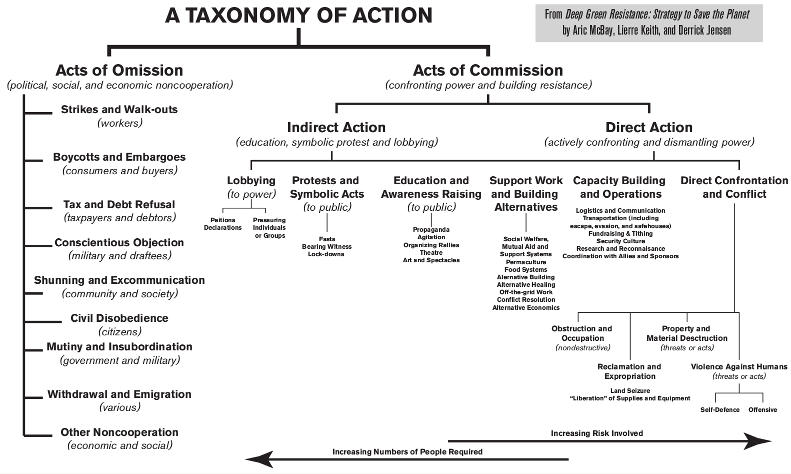

If you review the taxonomy of action chart, you’ll see that the actions on the left consist mostly of shaping operations, the actions along the center-right consist mostly of sustaining operations, and the right-most actions are generally decisive.

Click for larger image

These categories are used for a reason. Every effective operation—and hence every effective tactic—must fall into one or more of these categories. It must do one of those things. If it doesn’t—if that operation’s or tactic’s contribution to the end goal is undefined or inexpressible—then successful resisters don’t waste time on that tactic.