by Deep Green Resistance News Service | May 5, 2018 | Lobbying

by Center for Biological Diversity

WASHINGTON— Defenders of Wildlife, along with the Center for Biological Diversity and Patagonia Area Resource Alliance, today filed a notice of intent to sue the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to protect the Patagonia eyed silkmoth under the Endangered Species Act.

The rare Patagonia eyed silkmoth is clinging to survival in only three isolated locations in Arizona and Mexico. The groups previously petitioned the Fish and Wildlife Service to list the moth under the Endangered Species Act and designate critical habitat for the species.

“The Patagonia eyed silkmoth is hanging by a thread. With the only U.S. population existing in an Arizona cemetery, where its only remaining food source could be wiped out by cattle, this species clearly needs federal protection to save it from extinction,” said Lindsay Dofelmier, legal fellow at Defenders of Wildlife. “The Fish and Wildlife Service’s decision to dismiss evidence supporting listing the Patagonia eyed silkmoth was arbitrary. By failing to provide adequate explanation for the decision and not allowing for a 12-month status review, the Fish and Wildlife Service put the species at risk. Listing the silkmoth and designating critical habitat provides the best chance for recovery.”

The Patagonia eyed silkmoth exists in a single U.S. location, in an Arizona cemetery less than half an acre in size. In Sonora, Mexico, it lives on two sky islands, higher elevation areas that are ecologically different from the lowlands surrounding them.

“The Patagonia eyed silkmoth needs endangered species protection now, so we can start the work of recovering this beautiful animal,” said Brian Segee, a senior attorney at the Center for Biological Diversity. “The Endangered Species Act has saved more than 99 percent of plants and animals with its protection from extinction, and it can do the same for this rare moth.”

Cattle grazing was the primary historic cause of habitat loss for the moth and continues to play a major role in the precarious situation of the species. Mining and climate change also threaten to destroy the last vestiges of potential silkmoth habitat on both sides of the border. A catastrophic fire at critical times of the year, when the adults, eggs or larvae are out, could completely erase the moth from any of these remaining localities. Listing the silkmoth and designating critical habitat for the species offers its best chance of survival and recovery.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | May 4, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

by Boris Forkel / Deep Green Resistance Germany

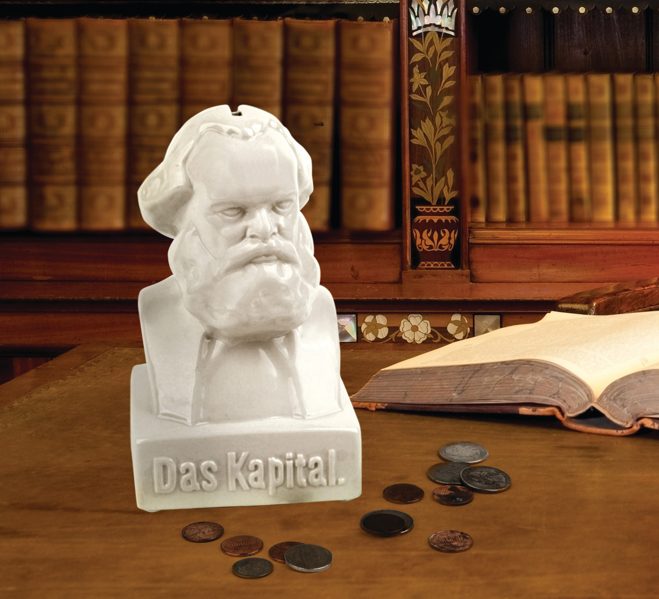

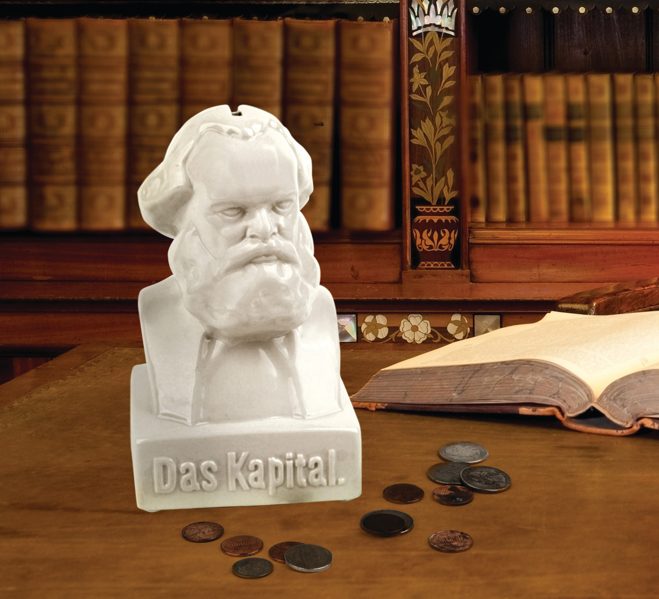

Capitalism reaches fulfillment when it sells communism as a commodity. Communism as a commodity spells the end of revolution.

—Byung-Chul Han

I’m a permaculturalist. And I became a permie in the first place because I wanted to break free from this culture.

To me, permaculture was and still is highly political. “Permaculture is revolution disguised as gardening” is one of my favorite Bill Mollison quotes.

After all, what freedom can we have without subsistence, without having control over our most basic resources, our own food? “There is no sovereignty without food sovereignty,” said Native American activist John Mohawk.

I’ve been so ardent and naive. I thought that the permaculture-approach is so ingenious that it would become a mass-movement, indeed a quiet and peaceful revolution. It would free us from being dependent on the digital food they sell us in grocery stores nowadays, and from the wage economy at the same time, because we would build small, local food cooperatives that would all be sharing the surplus.

Unfortunately, time and experience shows that it’s not that easy.

One of my permaculture teachers, who taught me the concept of the food forest, often said: “I don’t understand what’s the problem for all these critical people. Nowadays, we have all the freedoms we want.” He also articulated a very strange notion about the future: “Once we have reached the number of 10 billion, human population growth will come to a halt. Thanks to Internet technology, humans will then all be connected and serve as the consciousness of planet earth.” Attendants hung on his lips when he said that, and while everybody else was amazed by this perspective of a golden future, I sat quietly, stunned.

I knew in my heart that he was wrong, but couldn’t articulate a sufficient answer to his statements back then.

It made me angry. How can one say that “we have all the freedoms we want,” while the air we need to breathe is being polluted, the greatest mass extinction in planetary history is happening, the climate is being destroyed, the oceans are vacuumed and filled with toxic garbage? In short: when the most basic functions of our planet to support life are being destroyed?

What about the freedom of having breathable air? What about the freedom of having a livable planet? What about the freedom of having a future?

I’ve given a lot of thought to his statements ever since, because they seem so appealing to many people. The Earth never supported more than 2 billion humans until Fritz Haber and Robert Bosch indeed broke the planetary boundaries with the invention of the Haber-Bosch process. Nowadays, we are hopelessly overpopulated. So the number of 10 billion is purely random and nothing but magical thinking. The notion of Internet technology and humans as the consciousness of the planet is nothing more than a new fashion of the good old ideology of humans as the crown of creation. What about nature in this fantasy? With 10 billion (industrial) humans, there will hardly be anything left.

Everybody with a sane mind and a little understanding—especially a permie—should know that the trees, the fungi, the soil, the air, the water, the animals and so on, in short what we call nature, indeed is the consciousness of planet earth. Apparently, the manifest destiny of the technocrats is to eradicate what they perceive as primitive, raw, red in tooth and claw, wild and uncontrollable, and to replace nature with a “better” system of human technology.

Deconstructing that was the easy part. The hard part is his statement about freedom. With all this in mind, the primary question is: what does freedom mean for someone like him?

A friend of mine, who was lucky enough to hear Noam Chomsky speak live, told me that in the discussion after somebody asked the usual question: “What can we do about it?” Chomsky responded that he thinks this is a strange question. People from so-called developing countries would never ask such a question, only westerners, he stated. Apparently, third-world-people still have a clearer sense for suppression and cultures of resistance. “We should rather ask what we can’t do,” Chomsky said.

When I attended a talk by Rainer Mausfeld, of course someone asked the very same question. Mausfeld stated that this question shows how well the soft power techniques he’d been describing work. We can’t even imagine any form of resistance.

For more than a century, the political left’s analysis has been very clear: The suppression and exploitation of the poor (working class) by the rich (owning class), that is the very basis of capitalism, can only be solved by organized class struggle to come from the working class. This concept isn’t hard to understand. It is classic Marxism. But somehow, the ruling class has managed to completely eradicate it from the proletarian minds.

I’ve come across a lot more of what I like to call liberal lifestyle-activists. I understood that most permies chose permaculture not because they want a revolution (like I did), but because they want a more sustainable lifestyle for themselves. They believe that they are free, because they perceive their individualism and their freedom of choice as the greatest freedom, the greatest achievement of modernity. Being part of any group, class or movement is perceived as regressive. The notion of class struggle is so yesterday.

At the same time, they’re usually educated people, and they know that a lot of things are going badly wrong. But as liberals who are taking power out of the equation, and individualists lacking any concept of social group our class, they must take it all on themselves. “It is all of us who are causing the destruction,” they’d say.

As a result, the only thinkable form of political action are personal consumer choices. Buy organic soap and feel better.

A great example of this are vegans. No doubt that factory farming is horrible and has to stop. But as a lifestyle-activist, all you can do about it is to stop consuming meat. In your worldview, the problem can only be solved by everybody stopping eating meat.

For liberal lifestyle-activists, “having all the freedoms we want” can only mean the freedom to consume (or not consume) whatever we want, whenever we want, in any quality and quantity we want. This is the kind of “freedom” with which capitalism has hijacked us. If we can afford it, of course. But within neoliberal capitalist ideology, there is no such thing as a suppressed class. The poor are poor because they don’t work hard enough, or they are simply to stupid to sell themselves well enough.

“Neoliberalism turns the oppressed worker into a free contractor, an entrepreneur of the self. Today, everyone is a self-exploiting worker in their own enterprise. Every individual is master and slave in one. This also means that class struggle has become an internal struggle with oneself. Today, anyone who fails to succeed blames themselves and feels ashamed. People see themselves, not society, as the problem.”

Byung-Chul Han

For radicals, the question remains: Without the possibility of mass movements, how do we stop the destruction of the planet that is our only home?

For a new generation of serious activists who are tired of all that shit and ready to take action, DGR has the Decisive Ecological Warfare strategy.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 30, 2018 | Protests & Symbolic Acts

by Survival International

Thousands of indigenous people gathered in Brazil’s capital this week, to protest against plans to destroy their lands and lives.

The Indians, from tribes across the country, painted the streets with “blood,” marched through the city, demonstrated at government buildings, and called for their rights to be respected.

Sonia Guajajara, an indigenous leader and candidate for the Vice-Presidency in Brazil’s upcoming general election, said: “We are denouncing the genocide of our people…This is the most suffering we’ve experienced since the dictatorship. By staining the streets red, we are showing how much blood has been shed in our fight for the protection of indigenous lands… The fight goes on!”

The protest marks Brazil’s “Indigenous April” and follows the annual “Day of the Indian,” 19 April, when the country’s President often announces some progress in the protection of indigenous peoples’ ancestral lands. This year, no such announcements were made. Instead, it was reported that the head of the government’s Indigenous Affairs Department would be replaced, as he was not fulfilling the demands of anti-indigenous politicians and ranchers.

Politicians linked to the powerful agribusiness lobby are pushing through a series of laws and proposals which would make it easier for outsiders to steal indigenous peoples’ lands and exploit their resources.

This would be disastrous for tribes across the country, including the Guarani, who suffer one of the highest suicide rates in the world, as most of their land has been stolen for cattle ranching and soya, corn and sugarcane plantations.

Adalto Guarani told Survival International of the politicians’ plan: “Please help us destroy this! It’s like a bomb waiting to explode, and if it explodes, it will put an end to our very existence. Please give us a chance to survive.”

And uncontacted tribes, the most vulnerable peoples on the planet, could be wiped out if their lands are opened up. Tribes like the uncontacted Kawahiva and Awá are on the brink of extinction as they live on the run, fleeing violence from outsiders. But if their land is protected, they can thrive.

Survival International and its supporters in over 100 countries are working in partnership with tribes across Brazil to prevent their annihilation and the extinction of their uncontacted relatives.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 29, 2018 | Property & Material Destruction

Editor’s note: this is an anonymous communiqué previously published on Philly Anti-Capitalist. The featured image is unrelated to this action.

Early last week, we made the two tractors that Energy Transfer Partners was using to construct the Mariner East 2 pipeline near Exton, PA inoperative by cutting their hoses and electrical wires, cutting off valve stems to deflate the tires, introducing sand into their systems, putting potatoes in the exhaust pipes, using contact cement to close off the machines’ panels and fuel tanks, and a variety of other mischievous improvised sabotage techniques.

We feel called to fight for the natural world and would be lazy to submit to the demise of the earth, animal and self by not fighting against its destruction by machines and corporations who seek to kill it for capitalist growth. It was surprisingly easy and brought us so much joy. We’ve read since that ETP has had to acknowledge the damage, which they are usually careful to cover up, and see that this wreck of a project could be seriously compromised by the proliferation of more actions like these.

For those restless, angry warriors out there, we hope you find similar happiness in destroying little by little the tools of this capitalist settler-colonial nation. Death to colonization and capitalism… Shout out to everyone out there still attacking in spite of repression and grief.

by DGR News Service | Apr 28, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

Featured image: Activists March Against Nestlé On Bridge of The Gods

Land defense and social justice work are necessary for healthy human and non-human communities, but any victories will be irrelevant if industrial civilization makes the planet literally unlivable. The system must be stopped before it triggers irreversible runaway climate change and ecological collapse, and only strategic underground attacks against critical infrastructure will stop it. There are many hard working activists in the aboveground struggle, though we can always use more. Unfortunately, as far as we can tell, vanishingly few people are carrying out the necessary attacks against industrial bottlenecks and weak points in infrastructure. Underground promotion remains the most important work for those of us in the aboveground.

To help us better understand the barriers to formation of an underground, we’re surveying those who have committed to aboveground work. If you’ve joined a radical aboveground group, publicly stated your support of ecosabotage, engaged in environmental civil disobedience, or otherwise drawn attention to your strong enviro-political beliefs, we want to learn the reasons behind your decision.

Please take a few minutes to let us know why you chose an aboveground path, rather than underground work. You can fill out the short anonymous survey below, email us, or leave a comment. Thanks!

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 28, 2018 | Protests & Symbolic Acts

Featured image: Destruction in León. Source anonymous. The official death toll from explosions of state violence has risen to 63.

by Laura Blume / Intercontinental Cry

Over the past week, Nicaragua has erupted in protests. While this current crisis started over pension reform, its development has revealed far greater rifts. It appears Nicaraguans have finally had enough of the Ortega regime. They are demanding that the corruption and oppression end. For many, it may seem shocking that a country that re-elected President Daniel Ortega for his third consecutive term in November 2016, with a reported 72 percent of the national vote could now, less than two years later, have taken to the streets en masse demanding his immediate removal from office.

I first visited Nicaragua in 2012, and have spent extensive time in the country over the past two years undertaking ethnographic fieldwork as part of my PhD dissertation. Each time I arrived in Nicaragua, I heard more and more people express mounting levels of frustration with the political situation. Yet, it was a frustration that the majority internalized and kept mainly to themselves, mentioning it to me only in private spaces and usually when other Nicaraguans were not around. As someone explained to me on one of my first trips to the country, “On the street, we’re all Sandinistas. We have to be if we want to work and have our kids go to school. But in private… well, there you may hear another story.”

I began hearing people who had fought in the 1978-79 Sandinista Revolution and 1981-90 Contra War lament that the current government now resembled the Somoza dynasty they had fought so hard and sacrificed so much to overthrow. Many people told me they were still a Sandinista, just not a Danielista, highlighting their commitment to the ideals of the historic fight against dictatorship and the Sandinista Revolution, but fundamental disagreement with the current regime.

Hearing about corruption and repression is one thing, but witnessing it is another. In November 2017, in Bilwi, the capital city of the North Caribbean Coast Autonomous Region of Nicaragua, I watched the Ortega Administration steal a local election. As I felt the burn of tear gas deployed against peaceful protestors and watched National Police – trucked in from the capitol – fire live rounds at the crowds, perspective on Nicaraguan politics changed, permanently.

In the 2017 municipal elections in Bilwi, the primary match-up was between two parties: the FSLN (Frente Sandinista de Liberacion Nacional, Sandinista National Liberation Front) and the indigenous Miskitu party YATAMA (Yatama Aslatakanka Masrika Nani/Sons of the Mother Earth). I decided I would try and divide my time between the contacts I had from each party, hoping to remain impartial. On election day, I spent the morning with a contact who supported the FSLN. I accompanied them as they drove FSLN voters to the polls. At one point, they admitted to me that certain claims of the opposition were valid: Nicaragua was a dictatorship. But they countered that not all dictatorships were bad, exclaiming, “just look at all the progress in Cuba!”

Around 4 pm that afternoon, I arrived at a voting center with a YATAMA contact. Although the official closing time for the center was 6pm, elections officials were shutting its doors. People became angry that they were not being allowed to vote. The situation grew tense as a crowd formed. People reported facing harassment from authorities – including two women who told me about threats of sexual violence – when they tried to demand their right to vote. I remember thinking how my FSLN contacts had stressed to me that they would be voting early in the day, and making sure other FSLN supporters did the same. Did they know this would occur in the afternoon? Reports of similar problems soon emerged from other voting centers around Bilwi.

A few hours later, waiting outside the same voting center in a crowd of YATAMA supporters as they observed a contested re-count of votes, I noticed a new group of people arriving – all young and male. They began encircling the YATAMA supporters and jeering at them. One of the young men tossed a handful of dirt towards them, clearly trying to instigate a fight. Thankfully, the YATAMA supporters did not take the bait. But in that moment, I got a glimpse of the nature of the Sandinista turbas, the same groups of youths who are now terrorizing various parts of the Pacific coast and the capital city of Managua.

Once the FSLN victory was announced, YATAMA supporters took to the streets to protest what they perceived as a fraudulent outcome. While I had tried to remain politically neutral, I certainly empathized with their frustration. The irregularities at the voting centers seemed far too widespread to consider the FSLN win a fair one. Moreover, those who did vote for the FSLN often did so because they felt obliged to do so. As one young woman told me, she had wanted to support YATAMA, but voted for the FSLN since she was fearful of losing her university scholarship.

FSLN-controlled media outlets declared that the YATAMA supporters were causing mayhem in the city, but they were certainly not alone on the streets. Groups of the FSLN youth were out in force, fighting against the YATAMA supporters and vandalizing properties. The YATAMA house and radio station (which serves as one of the few Miskitu-language services in the region) and famous defiant Indian statue were all destroyed, which some audacious Sandinista sources blamed on YATAMA supporters. Through all of this, the protesters faced violent government suppression, including tear gas and even gunfire. Adding to the disarray, groups of criminals who claimed no political loyalties took advantage of the chaos to loot local businesses. One jokingly asked me if I wanted any new electro-domestic appliances from Gallo Más Gallo.

Injured protesters taking refuge in the YATAMA house, before it was burned to the ground. Photo by author.

After a day and a half of the protests, the local airport was shut down and rumors circulated that troops would soon blockade the road. I decided it was time for me to leave town.

Unbeknownst to me, a fight at the bus station broke out 15 minutes prior to my departure time. When I arrived, it was full of police and special forces from Managua, antimotines. As I approached the bus, eager to leave, an official stopped me. He claimed that he had seen me the day before at the protests and ordered that nearby police search my luggage as he closely examined my passport. He demanded my name, which he wrote down. Without my permission, he took a photo of my face with his phone to send to “central.” He also insisted that I hand over my cellphone and delete any protest photos.

The official also accused me of supporting YATAMA and of even working for the CIA – a potentially grave accusation in a country still reeling from the U.S. infringements of the 1980s. I insisted I was a poor graduate student incapable of backing any foreign political party and that I did not work for any government agency. (I was tempted to point out that a CIA agent would have nicer transportation than the local 18-hour “chicken” bus from Bilwi to Managua I was taking, but decided that snark would not help in this situation.) Finally, the official let me go and I boarded the bus. I have never been so relieved to take a seat and settle in for the grueling ride to the capital as I was at the moment the bus finally puttered out of the tiny Bilwi bus depot.

Upon arrival on the Pacific side of the country, a few of my friends joked that I needed to go buy some pro-FSLN swag to help improve my image in the eyes of the government. The Pacific side of Nicaragua was mostly calm after the municipal elections, and most of the people I spoke with dismissed the chaos in Bilwi as something unique to the dynamics on the indigenous-dominated and long-fractious Miskitu Coast. Yet, no Nicaraguan I spoke with was surprised by my tale of police harassment and voter suppression. The most common response to my depiction of the ways the FSLN had strategically manipulated the election outcome was laughter; this was all very old news to Nicaraguans.

Now, in April 2018, the protests are not specific to an election, led by an opposition party, or isolated in a remote part of the country. The protests are occurring all across the heartland of supposed FSLN support. The below photo is from Friday night in León, where the FSLN won the 2017 municipal elections with over 80 percent of the vote. While the government says right wing-backed criminals are responsible for the vandalism, witnesses say it was the Sandinista turbas who were, quite literally in this case, pouring gasoline on the fire.

Some Nicaraguans tell me that the situation has started to calm down. Others say it is just the calm before the storm. Regardless, even if things settle down this time, the mask of democracy has been torn off the Ortega regime. So far, during less than a week of protests, at least 63 people have been killed*, and many more are injured or missing. Nicaraguans are now publicly speaking out against their repressive government, and hundreds of thousands are taking to the streets. Yet, dictators rarely cede power in response to protest, and so this struggle is unlikely to be a fast or an easy one.

I initially wanted to write about what I witnessed in Bilwi, but I decided to stay silent, for the same reason that Nicaraguans do not like to talk about politics on the street: speaking out against the Ortega regime almost always has consequences in Nicaragua. This government has expelled several researchers and academics before me, threatening them along the way. But, now, like so many of my friends in Nicaragua and on their behalf, I am enraged by what is happening. It is hard to silently watch the videos of a journalist being shot in the head in a city that I have come to consider a second home, or of students and protestors being beaten, abducted, and even killed by government forces along streets I have walked too many times to count. As a friend in Managua recently told me, “it is difficult to feel so impotent, but you know what is beautiful? To be next to someone who you do not know but you help and you defend because they believe in the same thing you do.” I cannot be on the streets of Managua marching with the protestors right now, but I can provide a voice that amplifies the calls of those protesters – and as an academic, further evidence that supports their cause.