by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 8, 2017 | Strategy & Analysis

This is the fifteenth installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

via Deep Green Resistance UK

This post will look at if nonviolence is effective and why it has become the default tactic of activists in industrialised countries. I’ll then conclude this run of posts on the problems of pacifism and nonviolence.

Is Nonviolence Effective?

Nonviolent resistance dominates most activist groups and campaigns in industrialised countries. If it were effective as a tactic, wouldn’t things be better than they are? Perhaps many nonviolent campaigns and movements do not adequately plan out their strategy and tactics. A number of nonviolence fundamentalists do state that nonviolence is powerless against extreme violence, [1] which is perhaps a good description of the society we live in.

Ward Churchill is clear that revolutionary strategy and tactics need to be tested to see if they’re able to achieve the goal of liberation. [2] If a critical assessment is not done, then there is a risk that the dogma of nonviolence takes precedence over achieving the goals that have been collectively set. [3]

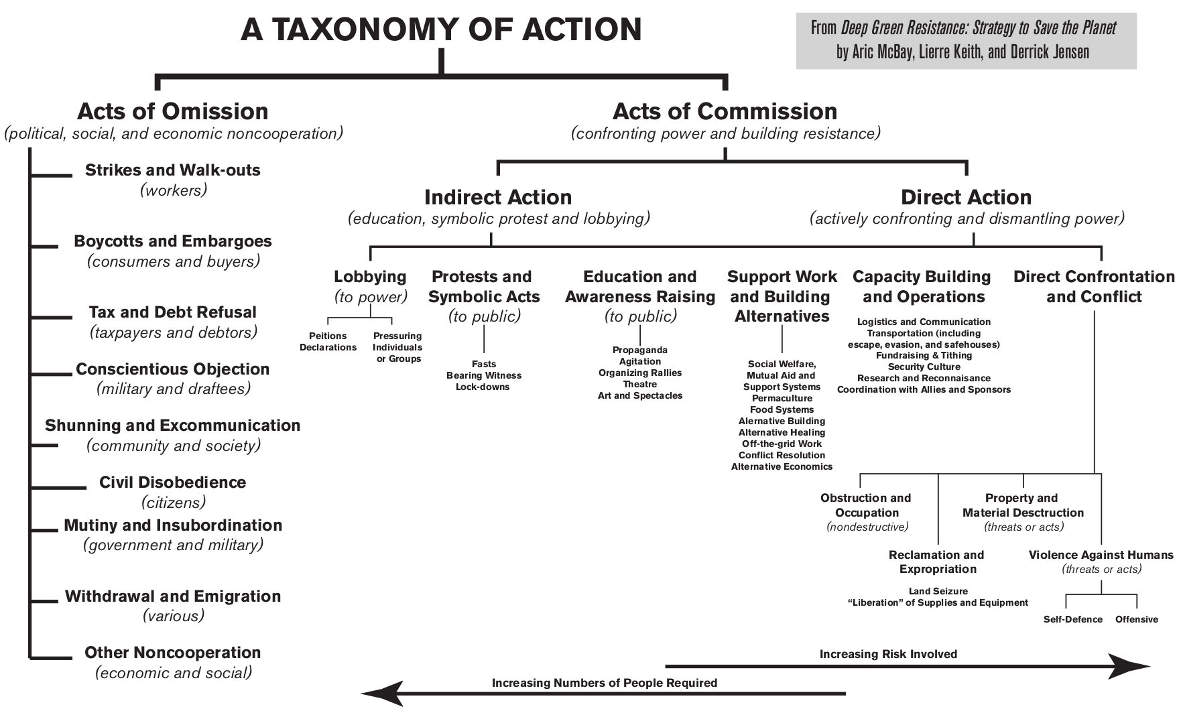

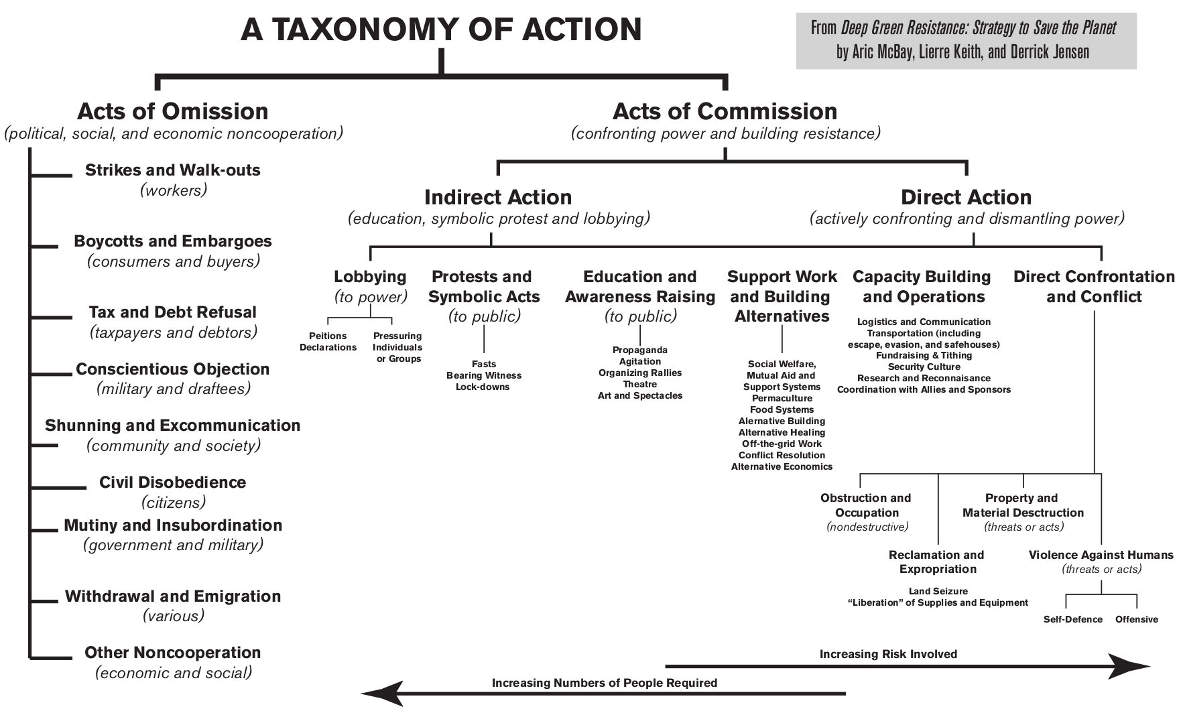

Using pacifist and nonviolent methods self-restricts activists to a limited number of tactics and gives little chance of surprise. Their responses become predictable to the state. Those advocating force are not doing so because they want violence, but because our options are so limited that at times it’s necessary. [4] We need to use nonviolent tactics to resist but it’s not enough. We need the whole range of tactics to be available to us if we’re going have a chance of a livable planet (see the Taxonomy of Action image below, and a full page version here).

Why Has Nonviolence Become the Default Tactic of Activists in Industrialised Countries?

Nonviolence became popular during the civil rights and anti-war movements, and has now become the accepted method of challenging the state. Many radical activists have internalised the taboo around the use of force and go along with the generally accepted view that the use of force is wrong under any circumstances.

There has been little intellectual or practical effort to examine the nature of revolutions and what’s required to ensure they happen in industrialised countries. This has created a vacuum, which has been filled with the most convenient and readily available set of assumptions – pacifism or nonviolent resistance. [5] Gelderloos puts this shift down to the disappearance or institutionalisation of the social movements of the past. [6] The heavy involvement of NGOs, mass media, universities, wealthy benefactors, and governments has made a move towards “civil” resistance all but assured. [7]

Another very important factor that has caused nonviolence to become the most common tactic in mainstream activism is that it allows people to protest and campaign without too much risk to themselves. They can feel that they are doing something to alleviate their guilt about the way the world is run and the amount of suffering taking place. They can bear moral witness, posturing as decent people but actually being complicit in the crimes that they purport to oppose by not doing what it takes to win. This is also known as the “Good German Syndrome.” [8]

According to Derrick Jensen, claims that militant actions will threaten one’s own resistance are similar to death camp inmates employing different approaches to survival. In these camps, some want to make things more comfortable, and perceive those that want to escape as threats to those who want a bit more soap or food. This causes a “constriction in initiative and planning” in those inmates who have not been completely broken and approach the daily tasks of survival with ingenuity. Indirectly, their field of initiative is constantly narrowed by those in control. This relates to the lack of effectiveness of our current resistance to the state; many are captives of this culture who have not been completely “broken,” but have been traumatised to the point that their “field of initiative” has been consistently narrowed by the state. Prolonged trauma results in a reduction in active engagement in the world because the victim learns that they are being watched, that their actions will be thwarted, and that they will pay dearly for them. [9]

Churchill outlines a process of radical therapy with five phases to work through the pacifist problem.

- Values clarification, where the need for revolutionary social change is explained. The difference between needs based on reality or feeling is explored. The goal of this phase is to determine if the person’s values are consistent with revolutionary change or reform.

- Reality therapy, which involves direct and extended exposure to the lives of oppressed people in industralised and less industralised countries. Those undergoing therapy would live in these communities for extended periods of time, eating the food and getting by on an average income for that community.

- Evaluation, which is a period of guided and independent reflection upon the observation and experiences in “the real world.”

- Demystification, at this point participants will argue that militant resistance is necessary but may not want to engage in it themselves. They may have never handled weapons, so are scared of them. In this phase, they are trained how to use weapons. This stage is not about training guerrilla fighters, but rather showing the participants that they can learn these skills—that a weapon is simply a tool, although a powerful and dangerous one—and therefore that the decision to use force is a tactical one.

- Reevaluation, in this phase participants will be helped to articulate their overall perspective on the nature and process of “revolutionary social transformation,” which includes their understanding of what specific roles they might take in the process. [10]

Where does this leave us? Jeriah Bowser argues:

[There is an] incredible amount of misunderstanding, narrow-minded dogmatism, and animosity that I obverse with many resistance communities. No matter what the social issue at hand, I have almost always found the parties involved to be rigidly polarized on the issue of violence: is it an acceptable tool to use for resisting oppression or not?

I believe both camps have much to offer the other, but we must first look at ourselves and examine our own positions critically, seeing the ways in which we might limit our own cause through hypocrisy, ignorance, privilege, personal fears and insecurities, and a misunderstanding of historical events. Then we can begin to understand the other side of the position, see the reasons that many people have chosen the alternative option, and ultimately try to find truths within their position that we can echo and sympathize with. To fail to consider and understand the other is to consciously remain ignorant. [11]

I completely agree with Bowser that those advocating force and those advocating nonviolence need to learn from each other, work together in solidarity where we have the same aims. It is achieving our collective goals that is important, not the tactics we employ—assuming these tactics aim to defend life.

Nonviolence fundamentalists paint those who think it might be necessary to use force as evil; but they all want the same thing: a just, sustainable world. The choice between using non-violence or force is a tactical decision. Those who advocate for the use of force are not arguing for blind unthinking violence, but against blind unthinking nonviolence. [12]

People who care about living in that just, sustainable world need to truly commit to their passion and act in whatever way makes sense to them. It is up to each individual and community to decide how to resist. The ultimate arbiter should be effectiveness. It is not right for others to judge those who choose to use force in service of revolution, especially if they are white, male and privileged.

Ultimately, the choice is not between nonviolence or violence, but between action and inaction .

This is the fifteenth installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

Endnotes

- Global Warming: Militarism and Nonviolence,The Art of Active Resistance, Marty Branagan, 2013, page 59

- Pacifism as Pathology, Ward Churchill, 1998, page 93/4

- Pacifism as Pathology, page 137

- Pacifism as Pathology, page 92-4

- Pacifism as Pathology, page 89

- e.g. anti-war movement, environmental movement

- Failure of Nonviolence, Peter Gelderloos, 2013, page 13-14

- Pacifism as Pathology, page 14

- Derrick Jensen is referencing trauma expert Judith Herman in Endgame Volume 2, Derrick Jensen, 2006 page 724-6

- Pacifism as Pathology, page 95-102

- Elements of Resistance: Violence, Nonviolence, and the State Paperback, Jeriah Bowser, 2015, page 38, read here

- Pacifism as Pathology, page 4

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 1, 2017 | Strategy & Analysis

This is the fourteenth installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

via Deep Green Resistance UK

Nobody in the world, nobody in history, has ever gotten their freedom by appealing to the moral sense of the people who were oppressing them. Once you study and really get a good understanding of the way the system…works, then you see, without a doubt, that the civil rights movement never had a chance of succeeding.

—Assata Shakur, founding member of the Black Liberation Army

Problem five with Pacifism and Nonviolence: No Real Threat to the State

Pacifists of the past have suffered greatly for their convictions. However, modern pacifists in rich nations seem to be thinking “What sort of politics might I engage in which will both allow me to posture as a progressive and allow me to avoid incurring harm to myself?” [1] Lierre Keith describes how civil disobedience used to be the practice of using passive bodies to shut something down, whereas now we see mostly symbolic actions. Civil disobedience was originally developed to obstruct a destructive action or process, to put bodies in the way of a harm that is happening. Nonviolent resistance can be a very effective political technique, but in many cases it has been watered down to a bizarre symbolic act across most of the left.

Some pacifists seem to look at protest as a catharsis to relieve the guilt they experience due to their privilege. This leads to a theater of pseudoresistance where the time, place, and form of resistance is booked with the police. A few arrests are made, which is often a form of nonviolent machismo worn as a badge of honour. [2]

Why do nonviolence fundamentalists preach their ideology primarily to social change groups instead of to the military, police, capitalists and other violent and oppressive groups? Why don’t they insist that these groups—those who use violence in the worst, most organized fashion—disarm first? Often, it seems they target the groups that are already nonviolent with a set of rules that further restricts their already limited power.

There is also some question around the strategic and tactical advantages of nonviolence. Peter Gelderloos dedicates a chapter to this in Nonviolence Protects the State where he critiques the four types of pacifist strategy: the morality play, the lobbying approach, the creation of alternatives, and generalized disobedience. [3]

When pacifism and nonviolence are your primary tactics, it’s often impossible to negotiate the terms of struggle with the state. [4] Those in power will only use their time and resources on campaigns and groups that they view as a threat, and will tolerate or even support harmless activities. [5].This is a much-needed pressure valve to stop campaign groups becoming militant or effective. It also supports the pretense that democracy is alive and well. Think how violently repressive the British state was in Ireland and India to crush resistance movements. This only radicalised the population more. Now the repression is much more subtle.

Reformism can actually strengthen the oppressive systems we face. It seeks to change a harmful system, while attempting to make the conditions more tolerable for the population. Systems only change when power is destroyed or fundamentally redistributed. In many cases, reformist work may actually be counterproductive. [6]

Democracy is generally held up as the ideal social structure. Gelderloos argues that in reality, the difference between democracy and dictatorship is often smaller than you would think, or even fictitious. In practice, any difference is based on ritual. The two forms of government are interchangeable, and when a government goes from a dictatorship to democracy, many of the same people stay in charge. Wolff makes a similar point that a modern industrial democracy is no different than a dictatorship—“it is only superstition and the myth of legitimacy that invests the judge, the policeman, or the official with an exclusive right to the exercise of certain kinds of force.”

Gelderloos makes a further point that nonviolence revolution is technically anti-democratic as it requires a small minority to go against the will of the masses, at least initially. [7]

Gelderloos describes Gene Sharp’s book, From Dictatorship to Democracy, not as a strategy but as a template to be reproduced, and many have tried. He observes that this approach has created success on its own terms but that this has occurred in a vacuum, with the absence of competing methods of social change. [8]

For example, Gelderloos identifies the number of issues with the Colour Revolutions:

If nonviolent regime change is best suited to achieving democracy, how can it be that the same method also tramples basic democratic principles like due process? If it is democratic to oust fraudulently elected dictators using mass protests and obstruction, but a “de facto coup” to oust an unpopular, corrupt but elected and impeachable president using those same methods, what is the line between dictatorship and democracy? If due process can be twisted or stacked by dictators, but respect for due process is the elemental characteristic of democracy, then are mass protest and disobedience fundamentally democratic or anti-democratic?

Gelderloos describes how the Colour Revolutions also lacked social critique and instead focused on a simple message of opposition. The strategic decisions came from the top of the movement and needed the support of the elite. The military and police had already been convinced to support the “revolution” from the start. This results in the nonviolent protesters being spectators in their own movement. It’s telling that each Colour Revolution resulted in a government that wanted a close relationship with the West rather than Russia. [9]

The outcome of a nonviolent revolution is hard to predict. For example, look at the Arab Spring uprisings in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, Syria and a number of other countries. The first two resulted in a relatively non-violent transition to “democratic” governments. Libya, however, is unstable and violent with a struggling parliament after its civil war. The uprising in Syria resulted in a civil war and the worst refugee crisis, still ongoing, since the second world war.

Some nonviolence fundamentalists argue that to be successful, a campaign needs to champion a cause that everyone supports. [10] Unfortunately that doesn’t appear possible in most industrialised countries. Most of their citizens think they are happy and comfortable with their lifestyle and don’t want to give it up.

Problem Six with Pacifism and Nonviolence: Nonviolence Increases Repression

One of the complaints that nonviolence fundamentalists have about using force is that is will cause the state to repress the movement more than if nonviolence is used.

The state will use physical force to defend itself against unwanted threats to its existence. Any real threat, using force or nonviolent direct action will provoke a response. Why would the immoral state act morally in an instance when nonviolence is used? [11]

Repression always increases as movements become larger, stronger or more effective. Generally, governments take advantage of weakness or limited resistance to increase repression. In relation to repression, governments are proactive, not reactive, and will take advantage of peaceful social resistance to intensify their implementation of social control compared to when there is militant resistance. In this regard, European countries with radical movements that use combative tactics such as Greece, Spain and France can be contrasted with countries with less resistance and high levels of pacifism and surveillance, such as the UK and Holland. [12]

So that concludes the list. I do not necessarily agree with every point, but I think they raise important questions that have not been satisfactorily dealt with by nonviolence advocates.

This is the fourteenth installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

Endnotes

- Pacifism as Pathology, Ward Churchill, 1998, page 61

- Mike Ryan write about the Canadian peace movement in Pacifism as Pathology, page 139/40, takku.net/mediagallery/mediaobjects/orig/f/f_ward_churchill_-_pacifism_as_pathology.pdf

- Nonviolence Protects the State, Peter Gelderloos, 2005, page 55-75

- Pacifism as Pathology, page 47

- Drinking Molotov Cocktails with Gandhi, Mark Boyle, 2015, page 137

- Drinking Molotov Cocktails with Gandhi, page 9

- Failure of Nonviolence, Peter Gelderloos, 2013, page 106

- Failure of Nonviolence, page 98

- Failure of Nonviolence, page 98-104

- Blueprint for Revolution: How to Use Rice Pudding, Lego Men, and Other Non-Violent Techniques to Galvanise Communities, Overthrow Dictators, or Simply Change the World, Srdja Popovic, Matthew Miller, 2015

- Pacifism as Pathology, page 59

- Failure of Nonviolence, page 288-9

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 30, 2017 | Strategy & Analysis

by Derrick Jensen

When I find myself in times of trouble, I’m less interested in Mother Mary’s wisdom than I am in Joe Hill’s: Don’t mourn; organize.

There’s a sense in which Trump’s election is a surprise, similar to how we somehow seem to be continually surprised when easily predictable negative consequences of this way of life come to pass. So we’re surprised when bathing the world in insecticides somehow causes crashes in insect populations, when covering the world in endocrine disrupters somehow leads to the disruption of endocrine systems, when damming and dewatering rivers somehow kills the rivers, when murdering oceans somehow murders oceans, when colonialism somehow destroys the lives of the colonized, when capitalism somehow destroys communities and the natural word, when rape culture somehow leads to rape, and so on. And we’re surprised when a racist, woman-hating culture elects a racist man who hates women.

But there are also many senses in which the rise of Trump or someone very like him was entirely predictable.

An empire in decay leads to a desperate push to the fore of values manifested by Trump: woman-hatred, racism, the scapegoating of those who impede empire, and a willingness to do whatever it takes to maintain that empire, to “make America [Greece, Rome, Britain, China] great again.”

When those who have been able to exploit others with impunity find their way of life (and more to the point, the exploitation and entitlement upon which their way of life is based) crumbling, what do they do?

We’ve seen this before. Why did lynchings of African-Americans go up soon after the Civil War and the end of chattel slavery? Why did the KKK rise again in the 1910s and 1920s? What is the relationship between Germany’s economic collapse in the 1920s and the rise of Nazi fascism?

Nietzsche provides one answer: “One does not hate when one can despise.”

So long as one’s exploitation of others proceeds relatively smoothly, one can merely despise those one exploits (despise, from the root de-specere, meaning to look down upon). So long as I have unfettered access to the lives and labor of, say, African-Americans, everything is, from my perspective, A-Okay. But impinge in any way on my ability to exploit, and watch the lynchings begin. The same is true for my access to other so-called resources as well, whether these “resources” are “timber resources,” “fisheries resources,” cheap plastic crap from China, or sexual and reproductive access to women. So long as the rhetoric of superiority works to maintain the entitlement, hatred and direct physical force remain underground. But when that rhetoric begins to fail, force and hatred waits in the wings, ready to explode.

Oh, but we wouldn’t do that, would we? Well, what if someone told you that no matter how much you paid to purchase title to some piece of land, the land itself does not belong to you. No longer may you do whatever you wish with it. You may not cut the trees on it. You may not build on it. You may not run a bulldozer over it to put in a driveway. Would you get pissed? How if these outsiders took away your computer because the process of manufacturing the hard drive killed women in Thailand. They took your clothes because they were made in sweatshops, your meat because it was factory-farmed, your cheap vegetables because the agricorporations that provided them drove family farmers out of business, and your coffee because its production destroyed rain forests, decimated migratory songbird populations, and drove African, Asian, and South and Central American subsistence farmers off their land. They took your car because of global warming, and your wedding ring because mining exploits workers and destroys landscapes and communities. Imagine if you began losing all of these parts of your life that you have seen as fundamental. I’d imagine you’d be pretty pissed. Maybe you’d start to hate the assholes doing this to you, and maybe if enough other people who were pissed off had already formed an organization to fight these people who were trying to destroy your life—I could easily see you asking, “What do these people have against me anyway?”—maybe you’d even put on white robes and funny hats, and maybe you’d even get a little rough with a few of them, if that was what it took to stop them from destroying your way of life. Or maybe you would vote for anyone who promised to make your life great again, even if you didn’t really believe the promises.

The American Empire is failing. Real wages have been declining for decades, for the entire lifetime of most people living today in the U.S. Indeed if real wages peaked in 1973, the last of those who entered the workforce in a time of universally increasing expectations are retiring. Sure, some sectors of the economy have done well, but what of those left behind? What of those whose livelihoods have been destroyed by a globalized economy, by the shifting of jobs to China, Vietnam, Bangladesh?

What happens to people in a time of declining expectations? What is the relationship between these declining expectations and the rise of fascism?

Two decades ago now a long-time activist said to me that Walmart and its cheap plastic crap was the only thing standing between the United States and a fascist revolution.

But cheap plastic crap can only put off fascism for so long.

There’s a difference between the ends of previous empires and the end of the current empire. That difference is global ecological collapse. Empires are always based not only on the exploitation of the poor but on the existence of new frontiers. Any expanding economy–and all empires are by definition expanding economies—need to continue expanding or collapse. America grew because there was always another ridge to cross with another forest to cut on the far side, always another river to dam, another school of fish to find and net. And the forests are gone. The rivers are gone. The fish are gone. The pyramid scheme upon which both civilization and more recently capitalism are based has reached its endgame.

And rather than honestly and effectively addressing the predicament into which not only we ourselves but the world has been pushed, it’s far easier to lie to ourselves and to each other. For some—and Democrats generally choose this lie—the lie can be that despite all evidence, capitalism need not be destructive of the poor and of the natural world, that the “invisible hand of Adam Smith” can, as Bill Clinton put it, “have a green thumb.” We just have to do capitalism nicely. And another lie—this one more favored by Republicans and manifested by Trump—is that the sources of our misery do not inhere in capitalism but rather come from Mexicans “stealing our jobs” and not remembering their proper place, from women no longer remembering their proper place, from African Americans no longer remembering their proper place. Their proper place of course being in service to us. And of course those damn environmentalists—“Enviro-Meddlers,” as some call them—are to blame for denying us access to that last one percent of old growth forest, that last one percent of fish. This lie blames anyone and anything other than the end of empire.

All of which brings us to the Democrats’ responsibility for Trump’s election. There has not been a time in my adult life—I’m 55—when Democrats have maintained more than the barest pretense of representing people over corporations. Through this time Democrats have functionally played good cop to the Republicans’ bad cop, as Democrats have betrayed constituency after constituency to serve the corporations that we all know really run the show. For generations now Democrats have known and taken for granted that those of us who care more for the earth or for justice or sanity than we do increased corporate control will not jump ship and support the often open fascists on “the other side of the aisle,” so these Democrats have calmly sidled further and further to the right.

Bad cop George Bush the First threatened to gut the Endangered Species Act. Once he had us good and scared, in came good cop Bill Clinton, who did far more harm to the natural world than Bush ever did by talking a good game while gutting the agencies tasked with overseeing the Act. Clinton, like any good cop in this farcical play, claimed to “feel our pain” as he rammed NAFTA down our throats.

What were we going to do? Vote for Bob Dole? Not bloody likely.

Obama made a big deal of delaying the Keystone XL as he pushed to build other pipeline after other pipeline, and as he opened up ever more areas to drilling. He pretended to “wage a war on coal” while expanding coal extraction for export.

What were we going to do? Vote for Mitt Romney?

For too long the primary and often sole argument Democrats have used in election after election is, “Vote for me. At least I’m not a Republican.” And as terrifying as I find Trump, Giuliani, Gingrich, Ryan, et al, this Democratic argument is not sustainable. Fool me five, six, seven, eight times, and maybe at long last I won’t get fooled again.

What we must finally realize is that the good cop act is, too, simply an act, and that neither the good cops nor the bad cops have ever had our interests at heart.

The primary function of Democrats and Republicans alike is to take care of business. The primary function is not to take care of communities. The primary function is not to take care of the planet. The primary function is to serve the interests of the owning class, by which I mean the owners of capital, the owners of society, the owners of the politicians.

We have seen over the last couple of generations a consistent ratcheting of American politics to the right, until by now our political choices have been reduced to on the one hand a moderately conservative Republican calling herself a Democrat, and on the other a strutting fascist calling himself a Republican. If we define “left” as being at minimum against capitalism, there is no functional left in this country.

For all of these reasons the election of Trump is no surprise.

But there’s another reason, too. The US is profoundly and functionally racist and woman-hating, nature hating, poor hating, and based on exploiting humans and nonhumans the world over. So why should it surprise us when someone who manifests these values is elected? He is not the first. Andrew Jackson anyone?

If that activist was right so many years ago, that cheap plastic crap from Walmart was the only thing standing between us and fascist revolution (and of course this cheap plastic crap merely pushed this social and natural destructiveness elsewhere) then he had to know also that cheap plastic crap is not a long term bulwark against fascism. It can only keep those chickens at bay for so long before they come home to roost.

The good cop/bad cop game is a classic tool used by abusers. You can do what I say, or I can beat you. You can sell me your cotton for 50 cents on the dollar, or I can hang you on a tree next to the last black man who refused my offer. Germans offered Jews the choices of different colored ID cards, and many Jews spent a lot of energy trying to figure out which color was better. But the whole point was to keep them busy while convincing them they held some responsibility for their own victimization.

I’ve long been guided by the words of Meir Berliner, who died fighting the SS at Treblinka, “When the oppressors give me two choices, I always take the third.”

By choosing the third I don’t mean simply choosing a third party candidate and perceiving yourself as pure and above the fray, as capitalism still continues to kill the planet.

I mean recognizing the truths about this whole exploitative, unsustainable, racist, woman-hating system. Recognizing that the function of politicians in a capitalist system is to act very much like human beings as they enact what is good for capital, as they facilitate, rationalize, put in place, and enforce a socio-pathological system. Recognizing that capital—including the functionaries of capitalism called “politicians”—will not act in opposition to capital because it is the right thing to do. These functionaries will not act in opposition to capital because we ask nicely. They will not act in opposition to capital because capitalism impoverishes the poor worldwide. They will not act in opposition to capital because capitalism is killing the planet. They will not act in opposition to capital. Period.

The power they wield, and the way they wield it, is not a mistake. It is what capitalism does.

Which brings us to Joe Hill. Don’t simply complain about Trump. Don’t simply throw up your hands in despair. Don’t fall into the magical thinking that the good cops would, if just unhindered by those bad cops, do the right thing or act in your best interests. Don’t fall into the magical thinking that capitalists will act other than they do. And certainly don’t take for granted that somehow magically we and the world will get out of this predicament, that somehow magically an anti-capitalist movement will spontaneously generate, or an anti-racist movement, a pro-woman movement, a movement to stop this culture from killing the planet. These movements emerge only through organized struggle. And someone has to do the organizing. Someone has to do the struggling. And it has to be you, and it has to be me.

A doctor friend of mine always says that the first step toward cure is proper diagnosis. Diagnose the problems, and then you become the cure.

You make it right.

So what I want you to do in response to the election of Donald Trump is to get off your butt and start working for the sort of world you want. Don’t mourn the election of Trump, organize to resist his reign, and organize to destroy the stranglehold that the Capitalist Party has over political processes, the stranglehold that capitalists and racists and woman-haters have over the planet and over all of our lives.

For more of Derrick Jensen’s analysis of racism, hatred, and the violence of civilization, see his book The Culture of Make Believe

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 20, 2017 | Strategy & Analysis

This is the thirteenth installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

Problem Two with Pacifism and Nonviolence: Nonviolence and pacifism as a Religion

Nonviolence fundamentalists do not deal well with the criticisms of their ideology and seem unphased by logical and practical critiques. Ward Churchill argues that it is delusional, racist, and suicidal to maintain that pacifism is always the most effective and most ethical approach. [1] He maintains that dogmatic pacifists (nonviolence fundamentalists) tend to deal with criticisms of their ideology by simply holding fast to their beliefs and reiterating pacifist principles. [2]

Pacifism and nonviolence originate from and share deep-seated ties to major religions. [3]

Derrick Jensen describes how pacifists put their self conception of moral purity above stopping injustice. [4] When he advocates for the use force in the fight to stop the destruction of the plant, liberal environmental activists and peace and justice activists often react with what Jensen calls the “Gandhi shield.” The Gandhi shield à la Jensen consists of repeating Gandhi’s name and invoking an inaccurate history to support dogmatic pacifism.

Peter Gelderloos in Nonviolence Protects the State dedicates a chapter to how nonviolence is deluded. This appears to be a trend noticed by many who must deal with the cult of dogmatic pacifism. Nonviolence fundamentalists are often caught up with principles, rather than focusing on what is needed to be effective. [5]

Nonviolence fundamentalists often base their worldview on a good-versus-evil dichotomy, and believe that they are good and positive for being peaceful and the state is bad and negative for using violence. This dichotomy results in a social conflict being framed as a morality play, with no material outcome. [6] I can see why some find the violence/nonviolence binary appealing; it’s straightforward but it doesn’t help us understand or act in the complex reality we all live in, especially if fighting for a better world.

Derrick Jensen states that for many pacifists, morality is abstracted from circumstance, meaning that direct violence is always wrong, under any circumstances, even if it might stop even more violence. [7] Does this mean the Jews that took up arms at the Nazi death camps were evil and wrong? Of course not. [8]

Problem Three with Pacifism and Nonviolence: Privileged and the Politics of the Comfort Zone

In Nonviolence Protects the State, Peter Gelderloos describes how nonviolence fundamentalists do not deal with oppression because of their often privileged position, and argues that nonviolence is often rooted in racist, statist, and patriarchal ideologies. Jeriah Bowser describes the typical “privileged pacifist”, who criticises those using violence and often does not see their own privilege. [9] Churchill describes the hypocrisy of pacifists supporting armed movements in colonized countries but being absolutely committed to nonviolence in the West. [10] It is not the place of pacifists or anyone in the West to tell oppressed people in colonial or neocolonial countries how to resist the oppression they face. [11]

Ward Churchill states that if you’re comfortable compared to others in your culture, this is a privileged position in society:

There is not a petition campaign that you can construct that is going to cause the power and the status quo to dissipate. There is not a legal action that you can take; you can’t go into the court of the conqueror and have the conqueror announce the conquest illegitimate and told to be repealed; you cannot vote in an alternative, you cannot hold a prayer vigil, you cannot burn the right scented candle at the prayer vigil, you cannot have the right folk song, you cannot have the right fashion statement, you cannot adopt a different diet, build a better bike path. You have to say it squarely: the fact that this power, this force, this entity, this monstrosity called the state maintains itself by physical force, and can be countered only in terms that it itself dictates and therefore understands.

It will not be a painless process, but, hey, newsflash: It’s not a process that is painless now. If you feel a relative absence of pain, that is testimony only to your position of privilege within the Statist structure. Those who are on the receiving end, whether they are in Iraq, they are in Palestine, they are in Haiti, they are in American Indian reserves inside the United States, whether they are in the migrant stream or the inner city, those who are “othered” and of color, in particular but poor more generally, known the difference between the painlessness of acquiescence on the one hand and the painfulness of maintaining the existing order on the other. Ultimately, there is no alternative that has found itself in reform there is only an alternative that founds itself — not in that fanciful word of revolution—- but in the devolution, that is to say the dismantlement of Empire from the Inside out. [12]

Problem Four with Pacifism and Nonviolence: Nonviolence Fundamentalists Complicity with the State

Another problem related to the last critique is nonviolence fundamentalists’ complicity with the state, when existing power structures aren’t challenged and the nonviolent activists “play the role of dissent,” which ultimately empowers and legitimises the state. Churchill describes how pacifism pretends to be revolutionary, with the “rules of the game” having been already agreed by both sides – demonstrations of “resistance” to state policies will be permitted as long as they don’t interfere with the actual implementation of those policies. [13]

Of course, not all nonviolence is so false, but the majority of pacifistic resistance could be described as a “performance.” The outcome is never in any doubt.

Nonviolence fundamentalist also criticise those who call for the use of force or violence, but will ignore the state violence happening every day. [14]

Bill Meyer makes the point in his essay that, contrary to expectations:

Nonviolence encourages violence by the state and corporations. The ideology of nonviolence creates effects opposite to what it promises. As a result nonviolence ideologists cooperate in the ongoing destruction of the environment, in continued repression of powerless, and in U.S./corporate attacks on people in foreign nations.”

Anarchist writer Peter Gelderloos has serious issues with nonviolent activists working with the police by giving them information (snitching); removing masks, which is effectively snitching; using cameras to take photos of militants; and planning march routes in cooperation with the police. [15] Of course, there is a legitimate place for creating “family friendly” resistance spaces and marches, but resistance must extend well beyond this.

Gelderloos describes how nonviolence fundamentalists often operate as “peace police” to control protests. Examples include policing resistance to the I-69 in the US midwest in the 1990’s and 2000’s, protests against the police murder of Oscar Grant in 2009 in San Francisco, and the protest march against the police murder of homeless man Jack Collins in Portland in 2010. [16]

Derrick Jensen describes how nonviolent protesters have turned on Black Bloc Anarchists for smashing shop windows. [17] Ward Churchill describes how pacifists have reported militants to the police and have worked to tone down actions to make them more symbolic. [18] It’s important to ask why white support for the Black Panthers disappeared when they responded to violent state repression with armed resistance. [19]

Nonviolence fundamentalists are very open about working with the police to inform on militants that might “ruin” their protest. Srdja Popovic in Blueprint for a Revolution promotes taking pictures of anarchists and uploading them to social media. Marty Branagan in Global Warming, Militarism and Nonviolence: The Art of Active Resistance, suggests forging links with the police to try to get them to defect to the protest movement.

For me, I can see why there might be resistance to Black Bloc activities at a nonviolent protest as described in post seven. I can also completely understand why individuals want to use Black Bloc tactics at another ineffective protest. But what is appropriate very much depends on the circumstances of each protest event. The use of militant resistance at a nonviolent protest can dilute and disempower the message and reduce the movement building potential.

With regard to talking or working with the police: I think that trying to convince police to join resistance movements is a good thing to do where the opportunity presents itself, of course being aware that the police may simply be trying to gather information from you. It’s a fine line to walk, and not for everyone. I do not think it is acceptable to work (or suggest working) with the police to inform on other activists.

This is the thirteenth installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

Endnotes

- Pacifism as Pathology, Ward Churchill, 1998, page 84-86

- Pacifism as Pathology, page 83

- Pacifism as Pathology, page 83/4. Endgame Vol.1: The Problem of Civilization, Derrick Jensen, 2006, page 295 and 300

- Engame, page 298/9

- How Nonviolence Protects the State, Peter Gelderloos, 2007, chapter on nonviolence being deluded, Read online here

- Pacifism as Pathology, page 52

- Endgame, page 296

- Pacifism as Pathology, page 53

- Elements of Resistance: Violence, Nonviolence, and the State, page 111, Read online here

- Pacifism as Pathology, page 70

- How Nonviolence Protects the State, page 22/23

- Pacifism as Pathology, page 27/8

- Pacifism as Pathology, page 71-3

- Elements of Resistance: Violence, Nonviolence, and the State, page 40-5, Read online here

- Failure of Nonviolence, Peter Gelderloos, 2013, page 261-3

- Failure of Nonviolence, page 137/8 and page 126-9

- Engame, page 81-84

- Pacifism as Pathology, page 67

- Pacifism as Pathology, page 69

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 13, 2017 | Strategy & Analysis

This is the twelfth installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

Pacifism is objectively pro-Fascist. This is elementary common sense. If you hamper the war effort of one side you automatically help that of the other. Nor is there any real way of remaining outside such a war as the present one. . . . others imagine that one can somehow ‘overcome’ the German army by lying on one’s back, let them go on imagining it, but let them also wonder occasionally whether this is not an illusion due to security, too much money and a simple ignorance of the way in which things actually happen. . . . Despotic governments can stand “moral force” till the cows come home; what they fear is physical force.

—George Orwell, author and journalist

via Deep Green Resistance UK

Nonviolence has an important part to play in our resistance. That said, there are a number issues with how it is promoted. Also the advocates of nonviolence have not adequately responded to the arguments made against it.

The next four posts will explore the issues with nonviolence; the effectiveness of nonviolence; and why nonviolence has become the default tactic of western activists. Nonviolent action is a very important tool in our resistance against industrial civilisation. So is using force or self defense. When, and in what circumstance, a particular method should be used is dependent upon a number of factors.

Most activists do not hear any arguments against nonviolence; it’s generally accepted by liberal activists, and within liberal communities in general, that the use of “violence” or force is wrong and self-defeating. The state, mainstream media, and nonviolence fundamentalists have been very successful at demonising the use of force. As a result, many activists have internalised the fear and criticism directed at those willing to advocate for or use militant tactics to resist capitalism and the destruction of the natural world. [1]

Problem one with Pacifism and Nonviolence: Rewriting history to make nonviolence look more effective

Nonviolence fundamentalists have often reframed historic examples by (1) excluding important contributions made by groups using force or militant resistance and (2) overstating/exaggerating the (material) success of nonviolent movements and actions. Examples of these historical omissions and rewritings include the Indian Independence Movement, the US Civil Rights Movement and the African National Congress’ struggle to end Apartheid. [2]

Gandhi’s nonviolence movement would not have had the limited success it did without the insurrectional acts of Bhagat Singh [3] and Chandra Bose. [4] The Indian Independence movement was also assisted by the decline in British power after fighting two world wars in thirty years. [5]

The US Civil Rights Movement was largely nonviolent, but it is doubtful that participants would have been successful without the more militant strategies and tactics of Malcolm X and the Black Panthers. Groups like the Deacons for Defense provided critical armed protection from violent KKK groups and other white supremacists in the south, in many cases engaging in pitched shootouts. In other cases, their armed presence at rallies and houses where organisers lived prevented violence from taking place.

Faced with both militants and pacifists, the US government had a choice to work with Dr. King or to allow Malcolm X to gain more support. The US state ultimately chose to work with Dr King to reform civil rights laws. [6] Charles Cobb and Gabriel Carlyle argue that “although nonviolence was crucial to the gains made by the freedom struggle of the 1950s and ’60s, those gains could not have been achieved without the complementary – and under-appreciated – practice of armed self-defence.”

When Nelson Mandela was compared to Gandhi and King, Mandela’s responses was “I was not like them. For them, nonviolence was a principle. For me, it was a tactic. And when the tactic wasn’t working, I reversed it and started over.” [7]

While Mandela began by practicing only nonviolence, he realised that he could not effectively win the struggle against the South African Apartheid Government through nonviolent means alone. After this realisation, he helped to found the militant wing of the ANC, the Umkhonto we Sizwe (Spear of the Nation). The combination of nonviolent and violent strategies and tactics is what ultimately brought the South African state to the negotiating table in 1990 [8].

Ward Churchill argues that there has never been a successful revolution or social reorganisation based solely on pacifism ; some form of “violence” or force has been essential in every case. [9]

In many cases of “successful” nonviolent resistance movements, change has been decidedly partial. “Take, for example, the issue of colonization in India and South Africa. Although many sources credit nonviolent campaigns and practices with the “end” of colonization in these regions (and others), in reality both India and South Africa exist under neocolonialist rule and hierarchies; rather than an “end” to colonialist practices, nonviolent movements have perpetuated the oppressive colonialist structures of power by placing power in the hands of indigenous elites while imperial powers still maintain control of the banks.” [10]

Contrary to what nonviolent advocates and pacifists often maintain, neither Gandhi nor King were completely opposed to the use of force. On this point, Gandhi affirmed that “I do believe that, where there is only a choice between cowardice and violence, I would advise violence. I would rather have India resort to arms in order to defend her honor than that she should, in a cowardly manner, become or remain a helpless witness to her own dishonor,” and “it is better to be violent if there is violence in our hearts than to put on the cloak of nonviolence to cover impotence.” [11]

In response to accusations of pacifism, King said “I am no doctrinaire pacifist. I have tried to embrace a realistic pacifism…violence exercised in self-defense, which all societies, from the most primitive to the most cultured and civilized, accept as moral and legal…the principle of self-defense, even involving weapons and bloodshed, has never been condemned, even by Gandhi, who sanctioned it for those unable to master pure nonviolence.” [12]

Thus, the real views of these icons have been distorted into an dishonest, unhelpful lie.

Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephan recently conducted a statistical analysis of the effectiveness of nonviolence. They compiled a list of 323 major nonviolent campaigns and violent conflicts from 1900 to 2006 and rated them as “successful,” “partially successful” or “failed.” [13]

On the whole, Chenoweth and Stephan utilize vague statistics to obscure more complex truths. They do not define violence in their analysis. They do not use a revolutionary criteria, and as a result the “Color Revolutions” and other reformist movements are classified as successful. They credit nonviolent movements with victory when international peacekeeping forces, i.e. armies, had to be called in to protect peaceful protesters. They have not published the list of campaigns and conflicts used in their original study. They explain that the list of major nonviolent campaigns was provided by “experts in nonviolence conflict,” who are likely to be biased toward promoting the efficacy of nonviolent campaigns and strategies. The “violent” conflicts they do include in their analysis are armed conflicts with over 1,000 combatant deaths: in others words, wars. Social movements and full-on wars are not comparable in this way; they do not occur under similar circumstances and factors beyond the participants’ choices influencing what sort of conflict occurs.

Chenoweth and Stephan state that they elected to include only “major” nonviolent campaigns, so weeded out ineffective nonviolent campaigns that only involved small numbers of people and yielded insignificant results. Chenoweth and Stephan took a number of measures to try to correct this bias in their study but none of these would of had a significant affect. [14]

This is the twelfth installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

Endnotes

- How Nonviolence Protects the State, Peter Gelderloos, 2007, page 5, Read online here

- Chapter six of Elements of Resistance: Violence, Nonviolence, and the State, Jeriah Bowser, 2015, looks at these three examples in detail, Read online here

- See the Resistance Profile for Hindustan Socialist Republican Association on the DGR website

- How Nonviolence Protects the State, page 8-10, Read online here

- Pacifism as Pathology, Ward Churchill, 1998, page 55

- Deep Green Resistance, Lierre Keith, Aric McBay, and Derrick Jensen, 2011, page 396. Pacifism as Pathology, page 142-3

- https://www.jacobinmag.com/2013/12/bob-herbert-on-nelson-mandela-1918-2013/, http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2013/12/06/anger-at-the-heart-of-nelson-mandela-s-violent-struggle.html, http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2013/12/05/don-t-sanitize-nelson-mandela-he-s-honored-now-but-was-hated-then.html, http://thegrio.com/2013/12/06/why-we-have-to-celebrate-nelson-mandelas-revolutionary-past/

- Elements of Resistance: Violence, Nonviolence, and the State, page 75-81, Read online here. See my article on Mandela’s path to militant resistance

- Pacifism as Pathology, page 57 and page 137

- How Nonviolence Protects the State, page 8-10. Counterpower: Making Change Happen, Tim Gee, 2011 page 127. Elements of Resistance: Violence, Nonviolence, and the State, page 68-96, Read online here

- Elements of Resistance: Violence, Nonviolence, and the State, page 74

- Elements of Resistance: Violence, Nonviolence, and the State, page 92

- Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict, Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephan, 2012

- Failure of Nonviolence, Peter Gelderloos, 2013, page 43-46

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 8, 2017 | Lobbying, Strategy & Analysis

Featured image: Cofan Indigenous leader Emergildo Criollo looks over an oil contaminated river hear his home in northern Ecuador. Photo by Caroline Bennett / Rainforest Action Network (flickr). Some rights reserved.

by Kiana Herold / Intercontinental Cry

Indigenous battles to defend nature have taken to the streets, leading to powerful mobilizations like the gathering at Standing Rock. They have also taken to the courts, through the development of innovative legal ways of protecting nature. In Ecuador, Bolivia and New Zealand, indigenous activism has helped spur the creation of a novel legal phenomenon—the idea that nature itself can have rights.

The 2008 constitution of Ecuador was the first national constitution to establish rights of nature. In this legal paradigm shift, nature changed from being held as property to a rights-bearing entity.

Rights are typically given to actors who can claim them—humans—but they have expanded especially in recent years to non-human entities such as corporations, animals and the natural environment.

The notion that nature has rights is a huge conceptual advance in protecting the Earth. Prior to this framework, an environmental lawsuit could only be filed if a personal human injury was proven in connection to the environment. This can be quite difficult. Under Ecuadorian law, people can now sue on the ecosystem’s behalf, without it being connected to a direct human injury.

The Kichwa notion of “Sumak Kawsay” or “buen vivir” in Spanish translates roughly to good living in English. It expresses the idea of harmonious, balanced living among people and nature. The idea centers on living “well” rather than “better” and thus rejects the capitalist logic of increasing accumulation and material improvement. In that sense, this model provides an alternative to the model of development, by instead prioritizing living sustainably with Pachamama, the Andean goddess of mother earth. Nature is conceived as part of the social fabric of life, rather than a resource to be exploited or as a tool of production.

The Preamble of the Ecuadorian Constitution reads:

“We women and men, the sovereign people of Ecuador recognizing our age-old roots, wrought by women and men from various peoples, Celebrating nature, the Pacha Mama (Mother Earth), of which we are a part and which is vital to our existence…. Hereby decide to build a new form of public coexistence, in diversity and in harmony with nature, to achieve the good way of living, the sumac kawsay.”

The traditional Quechua relation to the natural world is firmly rooted in the Constitution. The interchangeable use of nature and Pacha Mama testifies to the indigenous influence on the Constitution.

The concept and the praxis

In the 1970s, Christopher Stone, an American environmental legal scholar, articulated the legal notion of the rights of nature in his widely read essay Should Trees Have Standing? Stone envisioned a new way of conceptualizing nature through law that broke with the existing paradigm of the commodification of nature, often established through law.

Property rights are a primary example of commodifying the natural world. When treated as property, nature incurs damages that often go unrecognized. Stone writes that an argument for “personifying” nature can best be considered from a welfare economics perspective. Under capitalist economic logic, many externalities that negatively impact the environment are not registered when calculating the cost of an action. Transforming nature legally from mere property to a rights-holding entity would force byproduct environmental effects of production to factor into cost calculations. Under this framework, nature would be better protected.

Incorporating rights of nature into a national constitution is a powerful paradigm shift, but may seem hypocritical and idealistic given states’ continuing dependence on extractive industries. In Ecuador, 14.8 percent of the GDP comes from profits from natural resources as of 2014.

Moreover, under Ecuadorian law, the rights of nature are subject to principles of so-called national development. Article 408 of the constitution stipulates that all natural resources are the property of the state, and that the state can decide to exploit them if deemed to be of national importance, as long as it “consults” the affected communities. However, there is no state obligation to abide to the result of the consultation to these communities– a gaping hole in full protection of these environments and the people living within them.

Nonetheless, Ecuador’s Constitution was a significant step in changing the legal paradigm of rights to one that is inclusive of nature.

Bolivia follows

Bolivia followed in Ecuador’s footsteps. Evo Morales, the first indigenous head of state in Latin America, was elected in 2005 and called for a constitutional reform that ultimately established rights to nature in 2009.

Again, indigenous philosophies were instrumental in the formulation of Bolivia’s new Constitution. The constitution’s preamble states that Bolivia is founded anew “with the strength of our Pachamama,” placing the indigenous understanding of nature as central to the very creation of the revised political state. Like in Ecuador, the Bolivian Constitution allows anyone to legally defend environmental rights.

Bolivia’s government soon instituted the Law of Mother Earth in 2010, later re-coining it as the Framework Law of Mother Earth and Integral Development to Live Well. The law lays out a number of rights for nature, such as the right to life and to exist, to pure water, clean air, to be free from toxic and radioactive pollution, a ban on genetic modification, and freedom from interference by mega-infrastructure and development projects that disturb the balance of ecosystems and local communities.

Part of the rationale behind the law is the hope of helping the environment through reducing causes of climate change, which is directly in Bolivia’s interests. Increasing temperatures in Bolivia pose problems to the nation’s farming sector and water supply.

Again, however, this legal concept does not match economic realities. The rights of nature are directly at odds with extractive industries that are intimately tied to Bolivia’s model of economic development. Despite legal frameworks defending the rights of nature, Bolivia’s profits from natural resources comprise 12.6 percent of the GDP as of 2014.

But there are alternatives to the Andean experience. Across the Pacific, New Zealand has also granted a legal status of personhood to specific rivers and forest, thus enabling the environment itself to have rights.

The New Zealand Take on Rights of Nature

Unlike Ecuador and Bolivia, New Zealand’s rights of nature are not embedded in its constitutional law, but rather protect specific natural entities. Native communities in New Zealand were instrumental in creating new legal frameworks that give legal personhood, and thus rights, to land and rivers.

New Zealand has bestowed legal personhood on the 821-square mile Te Urewara Park, and the Whanganui River, the nation’s third-largest river. This was part of the government’s reparation efforts for the historical injustice at the foundation of New Zealand’s state: colonial conquest of land from native peoples.

The Tuhoe tribe’s ancestral homeland is currently the Te Urewara Park. With the imposition of colonial governance, most of their land was taken from them without consultation, resulting in great spiritual and socio-economic losses. The land was designated a national park in 1954.

The Tuhoe tribe never signed the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi with the British Crown, which stripped the tribe of their sovereign right over their land. They have since contested the British assertion of sovereignty that undergirds the formation of the modern New Zealand state.

Their centuries-long struggle finally yielded results. As part of New Zealand’s reparation process towards Indigenous Peoples, the national government negotiated with the Tuhoe tribe regarding their historic land. In 2012 the Tuhoe tribe accepted the Crown’s offer of financial reparations, a historical account and apology and co-governance of Te Urewera lands. The national government renounced ownership of the land, giving the land its own personhood.

Under this framework, the land is now a legal entity in itself, owned neither by the government nor the Tuhoe tribe. The land is no longer property. It is its own untamed natural presence in and of itself, with, as per native understanding, its own life force and identity.

The land is now co-governed by the Tuhoe people and the New Zealand government.

The 2014 Te Urewara Act declares the park “a place of spiritual value.” The Act acknowledges that it is the sacred home of the Tuhoe people, integral to their “culture, language, customs and identity,” while also being of intrinsic value to all New Zealanders.

In a similar process of granting legal personhood, the local Maori tribe, the Iwi, helped the Whanganui River earn legal personhood status in 2014 after winning a long-fought court case.

This was part of a centuries-long struggle that the Whanganui tribes undertook to protect the river. Since the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, the river has been subject to gravel extraction, water diversion for hydro-electric plans, and river bed works to better navigability, under protest from local tribes.

The Maori fought to protect the river through a series of court cases beginning in 1938, defending their claim to the management of the river as its rightful guardian. Throughout the court cases, negotiations were undergirded by the native saying “Ko au te awa, ko te awa ko au,” which translates to “I am the river and the river is me.” This reflects native philsophies of reciprocal and equal relations between people and nature.

New Zealand’s attorney general Chris Finlayson was quoted in the New York Times as acknowledging the Maori perspective as formative in the granting of rights to these natural entities, saying “In their worldview, ‘I am the river and the river is me,’” he said. “Their geographic region is part and parcel of who they are.”

Expanding Legal Horizons?

The legal concept of rights of nature signal the influence of Indigenous Peoples as political actors in state-making, fundamentally reimagining law and how the natural world is conceived. These ideas present a revolutionary rupture in the conventional anthropocentric understanding of sovereignty, and a realignment of how the natural world is valued. In fact, they could chart the path forward for a new understanding of mankind’s relation to the natural world, even if they operate within the legal structures that are not conducive to indigenous philosophies.

It is true that the rights of nature as they currently stand have deep limitations, particularly given the ongoing extraction of non-renewable natural resources in Ecuador and Bolivia. Problems of corruption, environmental inequality and economic dependence on extractive industries are major challenges to the full realization of the rights of nature.

Yet small acts can lead to lasting change. This shift in the way we relate to and legally protect nature, however small and plagued by obstacles, could be an incremental step toward a more sustainable relation to the planet that could allow us to preserve the earth for future generations.