by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jun 22, 2015 | Direct Action, Strategy & Analysis

By Will Falk / Deep Green Resistance

I went up to Mauna Kea’s summit a few days ago to pule (to pray) with some of the protectors on a ridge inside the Thirty Meter Telescope’s (TMT) proposed construction site. When we reached the site, we were confronted by half a dozen large men in orange vests and hard hats brandishing cameras, audio recorders, and notebooks.

The boss told us we were trespassing on an active construction site and subject to arrest. I looked around and saw nothing but a handful of back-hoes, the open sky at 14,000 feet above sea level, and a sublime, obsidian-colored cinder field stretching to the clouds. Of course, as I’m writing this, construction on Mauna Kea has been suspended for more than two months.

Kaho’okahi Kanuha explained that we were simply here to say some prayers. The boss told us again we were subject to arrest, mumbled into a hand-held radio, signaled to his men, and began recording us with a camera. The six men took up positions surrounding us as we held hands and faced the sky with Kaho’okahi leading some chants. Some of the men folded large arms across their chests glaring at us, others recorded us on camera, and one circled us nervously. I’ve been in a few fist fights in my life – needless, pointless expressions of a toxic masculinity – and I felt like these men were revving themselves up for some sort of scrap.

It was impossible for me to pray like this. Kaho’okahi seemed completely unnerved and when I asked him about it, he said this happens every time he comes to pray. I remember my experiences in Mass when I was younger. I imagine a priest at the altar leading his parish in the prayers that, for Catholics, turn bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ – all while strong men in hard hats patrol the pews and record the liturgy.

This, of course, would never happen. So, I ask: When Kanaka Maoli pray on a mountain exceedingly more beautiful than any basilica or cathedral I’ve ever been in, why are they being harassed like this?

I spent the first six essays in this Protecting Mauna Kea series trying to answer this question. The answers I came up with are validated after spending the last two weeks up here. The TMT project is based on the dominant culture’s sense of entitlement, historical amnesia, and pornification of Hawaiian culture. What could resemble a porn shoot more closely than men with cameras intruding on and recording acts of intimacy?

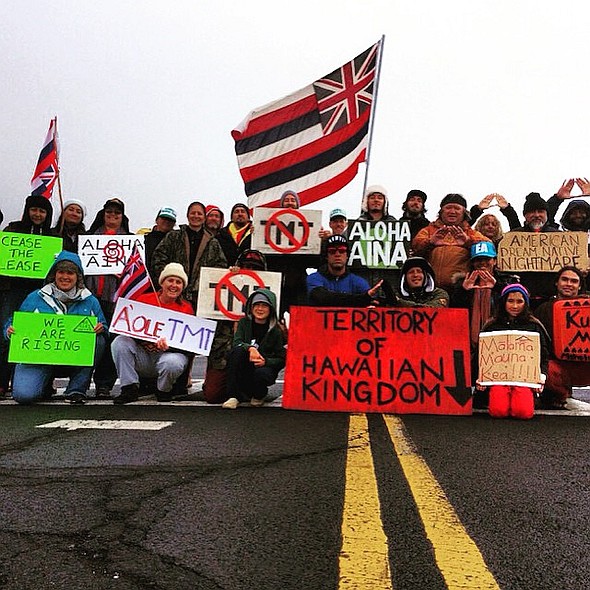

I think I’ve demonstrated that the TMT project is enabled by a problematic worldview and should not be allowed to proceed. After Governor David Ige’s announcement last week that he would support and enforce the TMT’s construction, the Mauna Kea protectors want the world to know we never expected the State to help us. We must stop the TMT project and we must do it ourselves. The question becomes: “How do we do it?”

The occupation on Mauna Kea is an expression that the protection of Mauna Kea is the people’s responsibility. We cannot trust the government to stop the TMT. We cannot trust the police. We cannot trust the courts. We have to do it ourselves. In other words, nothing has changed since the occupation began over two months ago. In many ways, the occupation on Mauna Kea reflects all of our environmental and social justice movements around the world.

The truth is – on the whole – environmental and social justice movements around the world have been getting their asses kicked. If they weren’t, 200 species a day wouldn’t be going extinct around the world. If they weren’t, we wouldn’t be losing indigenous languages at a rate relatively faster than species. If they weren’t, 95% of North America’s old growth forests wouldn’t have been clear cut. If they weren’t, every mother around the world wouldn’t have dioxin – a known carcinogen – in her breast milk. And, why are they getting our asses kicked? One reason is we’ve trusted those in power to do the right thing for far too long. The good news is – while construction on the Mountain is suspended – we have the opportunity to avoid mistakes other movements have made.

**********************

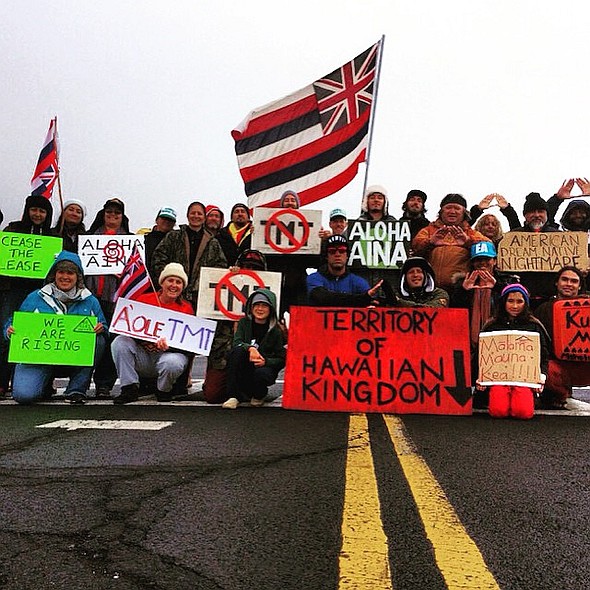

A couple days ago in a freezing cold, clinging mist, the Mauna Kea protectors called a 5:30 AM meeting in the now-famous crosswalk on the Mauna Kea Access Road to talk strategy in light of Governor Ige’s recent announcement. Some protectors lamented the announcement and were understandably scared about what was coming next. Others maintained that the TMT project was illegal anyway, and the courts would never let it proceed. Still others cited Kingdom of Hawai’i precedents and referred to the recent war crime charges filed with the Canadian government, to assure us the TMT was dead in the water. Finally. the boldest proudly proclaimed – with a hint of the false bravado that often accompanies anxious realizations – construction equipment would have to roll over their dead bodies to get to the construction site.

I stood silently in the circle listening. I am not Hawaiian and have no place arguing with those whose land I presently occupy. My mind was filling with memories of my experiences as a public defender. I recalled the cop in Kenosha, WI where I worked who put a gun to the temple of young Michael Bell’s head and murdered him as his mother and sister watched on for the crime of possibly breaking his bail conditions. I recalled that the cop was promoted and still on the force in Kenosha.

My stomach began churning as I felt that old feeling of helplessness sitting in a wooden chair in a courtroom next to another client being sentenced to prison while there wasn’t a damn thing I could do about it. There was no brilliant legal argument I could make, no impassioned plea the judge would listen to. The judge had power and armed men at his command, and I did not. It was as simple as that.

My heart was tugged back to Turtle Island, the so-called North American continent where the arrival of Europeans has meant the total extermination of dozens of aboriginal peoples. I think of the Taino who were annihilated within a few decades after Columbus’ contact with them. I can almost hear Tecumseh’s voice calling out from now-dead villages in present-day Ohio and Indiana asking what happened to the Pequods, the Narragansetts, and the Pocanokets. These peoples were wiped out by European colonizers while most of Tecumseh’s people, the Shawnee, were removed at gunpoint from their homelands in the Ohio valley hundreds of miles away to Oklahoma.

Some of the protectors here tease me, calling me “America’s ambassador to Hawai’i.” Listening to some of the protectors insist that the courts, the police, and the government would never let the TMT project happen, I wanted to explain that I understand the dominant culture we’re fighting against. I wanted to say I benefit from this culture. I was raised within in. I’ve lived amongst the type of people who run those courts, sit in their government, and become the police. I know what they are capable of and that many of them are sociopaths with no regard for the well-being of those who oppose them.

I didn’t say this, though, because I knew these feelings brought me too close to acting like the White Savior come to save aboriginal peoples from their ignorance. The truth is Kanaka Maoli understand very well – much better than I – the genocidal tendencies of the dominant culture occupying their lands. They do not need my reminder. I write about this now, only to narrate my relief when Kaho’okahi said, “I understand everyone’s concerns, but the way we’re going to win this struggle is pule plus action.”

**********************

Pule plus action. I agree with Kaho’okahi. Protecting Mauna Kea requires a strong spirituality, requires prayers, but it also means real, physical actions in the real, physical world. We need prayers, yes, just like we need those battling the TMT project in the courts, just like we need those signing petitions against the TMT project, just like we need those donating to the Mauna Kea protectors’ bail fund. But, at the end of the day, the surest way to stop the TMT project is to physically, actually stop the TMT project. This is what the encampment on Mauna Kea has always been about. The protectors are determined to place their bodies in between Mauna Kea’s summit and the construction equipment escorted by the police that will soon come to build the telescope.

I hope with all my heart that the courts will make the right decision and prohibit the TMT’s construction. I hope with all my heart that when the police receive their orders to pacify resistance on the Mountain that they will turn in their resignation papers. But, I’m not holding my breath. History has shown over and over again that the courts and the police will not help us.

Hope is not going to keep the destruction off Mauna Kea. It is much more likely that hope will bind us to ineffective strategies like trusting the government and hugging the police when they come to arrest us.

The Mauna Kea protectors insist on observing kapu aloha – a practice of love and respect – on the Mountain. I will not question this practice, but I will point out that our opponents do not observe kapu aloha. I fear that the more effective we become at stopping their project, the more violently they will respond.

I do not write this from a place of despair. I write this to give a clear-eyed vision of the effort it’s going to take. If we’re going to keep the TMT project from completion, we are going to have to do it ourselves. We’re going to have to show up in numbers large enough to overwhelm the police. We’re going to have to produce a mass of humanity thick enough to clog the Mauna Kea Access Road – and we may have to do it day in and day out for weeks. It will take a tremendous amount of bravery, shrewd strategic thinking, and a deep commitment from all of us. Or, in Kaho’okahi’s words, it’s going to take pule plus action. This is nothing new, though, and I believe we will win.

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Apr 25, 2015 | Agriculture, Building Alternatives, Strategy & Analysis

In 1993 Michael Carter was arrested and indicted for underground environmental activism. Since then he’s worked aboveground, fighting timber sales and oil and gas leasing, protecting endangered species, and more. Today, he’s a member of Deep Green Resistance Colorado Plateau, and author of the memoir Kingfishers’ Song: Memories Against Civilization.

Time is Short spoke with him about his actions, underground resistance, and the prospects and problems facing the environmental movement. The first part of this interview is available here, and the third part here.

Time is Short: Your actions weren’t linked to other issues or framed in a greater perspective. How important do you think having well-framed analysis is in regards to sabotage and other such actions?

Michael Carter: It is the most important thing. Issue framing is one of the ways that dissent gets defeated, as with abortion rights, where the issue is framed as murder versus convenience. Hunger is framed as a technical difficulty—how to get food to poor people—not as an inevitable consequence of agriculture and capitalism. Media consumers want tight little packages like that.

In the early ‘90s, wilderness and biodiversity preservation were framed as aesthetic issues, or as user-group and special interests conflict; between fishermen and loggers, say, or backpackers and ORVers. That’s how policy decisions and compromises were justified, especially legislatively. My biggest aboveground campaign of that time was against a Montana wilderness bill, because of the “release language” that allowed industrial development of roadless federal lands. Yet most of the public debate revolved around an oversimplified comparison of protected versus non-protected acreage numbers. It appeared reasonable—moderate—because the issue was trivialized from the start.

That sort of situation persists to this day, where compromises between industry, government, and corporate environmentalists are based on political framing rather than biological or physical reality—an area that industry or motorized recreationists would agree to protect might have no capacity for sustaining a threatened species, however reasonable the acreage numbers might look. Activists feel obliged to argue in a human-centered context—that the natural world is our possession, whether for amusement or industry—which is a weak psychological and political position to be in, especially for underground fighters.

Artwork by Stephanie McMillan

When I was one of them, I never felt I had a clear stance to work from. Was I risking a decade in prison for a backpacking trail? No. Well then what was I risking it for? I chose not to think that deeply, just to rampage onward. That was my next worst mistake after bad security. Without clear intentions and a solid understanding of the situation, actions can become uncoordinated, and potentially meaningless. No conscientious aboveground movement will support them. You can get entangled in your own uncertainty.

If I were now considering underground action—and of course I’m not, you must choose to be aboveground or underground and stick with it, another mistake I made—I would view it as part of a struggle against a larger power structure, against civilization as a whole. It’s important to understand that this is not the same thing as humanity.

TS: You called civilization a plan based on agriculture. Could you expand on that?

MC: Nothing else that the dominant culture does, industrial forestry and fishing, generating electricity, extracting fossil fuels, is as destructive as agriculture. None of it’s possible without agriculture. There’s some forty years of topsoil left, and agriculture is burning through it as if it will last forever, and it can’t. Topsoil is the sand in civilization’s hourglass, the same as fossil fuels and mineral ores; there is only so much of it. When it comes to physical limits, civilization has no rationality, or even a sense of its own ultimate self-interest; only a hidden-in-plain-sight secret that it’s going to consume everything. In a finite world it can never function for long, and all it’s doing now is grinding through the last frontiers. If civilization is still continuing twenty years from now, it won’t matter how many wilderness areas are designated; civilization is going to consume those wilderness areas.

TS: How is that analysis helpful? If civilization can never be sustained, doesn’t that remove any hope of success?

MC: If we’re serious about protecting life and promoting justice, we have to acknowledge that civilized humanity will never voluntarily take the steps needed for a sustainable way of life, because its history is entirely about war and occupation. That’s what civilization does: wage war and occupy land. It appears as though this is progress, that it’s humanity itself, but it’s not. Civilization will always make power and dominance its priority, and will never allow its priority to be challenged.

Artwork by Stephanie McMillan

For example, production of food could be fairly easily converted from annual grains to perennial grasses, producing milk, eggs, and meat. Polyface Farms in Virginia has demonstrated how eminently possible this is; on a large scale that would do enormous good, sequestering carbon and lowering diabetes, obesity, and pesticide and fertilizer use. But grass can’t be turned into a commodity; it can’t be stored and traded, so it can never serve capitalism’s needs. So that debate will never come up on CNN, because it falls so far outside the issue framing. Hardly anyone is discussing what’s really wrong, only which capitalist or nation state will get to the last remaining resources first and how technology might cope with the resulting crises.

Another example is the proposed copper mine at Oak Flat, near Superior, Arizona. The Eisenhower administration made the land off-limits to mining in 1955, and in December 2014 the US Senate reversed that with a rider to a defense authorization bill, and Obama signed it. Arizona Senator John McCain said, “To maintain the strength of the most technologically-advanced military in the world, America’s armed forces need stable supplies of copper for their equipment, ammunition, and electronics.” See how he justifies mining copper with military need? He’s closed the discussion with an unassailable warrant, since no one in power—and hardly anyone in the public at large—is going to question the military’s needs.

TS: Are you saying there’s no chance of voluntary reform?

MC: I’m saying that it’s going to be a fight. Significant social change is usually involuntary, contrary to popular notions about “being the change you want to see in the world” and “majority rules.” Most southern whites didn’t want the US Civil Rights Movement to exist, much less succeed. In the United States democracy is mostly a fictional theory anyway, because a tiny financial and political elite run the show.

For example, in the somewhat progressive state of Oregon, the agriculture lobby successfully defeated a measure to label foods containing genetically modified organisms. A majority of voters agreed they shouldn’t know what’s in their food, their most intimate need, because those in power had enough money to convince them. There’s little hope in trying to reason with the people who run civilization, or who are otherwise trapped by it, politically or financially or however. So long as the ruling class is able to extract wealth from the land and our labor, they will. If they’ve got the machinery and fuel to run their economy, they will eventually find the political bypasses to make it happen. It will consume lives and land until there’s nothing left to consume. When the soil is gone, that’s essentially it for the human species.

Oak Flat, Arizona

What’s the point of compromising with a political system that’s patently insane? A more sensible way of approaching the planet’s predicament would be to base tactical decisions on a strategy to strip power from those who are destroying the planet. This is the root, what we have to mean when we call it a radical—root-focused—struggle.

Picture a world with no food, rising temperatures, disease epidemics, drought, war. We see it unfolding now. This is what we’re fighting against. Or rather we’re fighting for a world that can live, a world of forests and prairies and free flowing rivers that build and stabilize soil and sustain biological diversity and abundance. Our love of the world must be what guides us.

TS: You’re suggesting a struggle that completely changes how humans have arranged themselves, the end of the capitalist economy, the eventual collapse of the nation-state model of society. That sounds impossibly difficult. How might resisters approach that?

MC: We can begin by building a movement that functions as a cultural replacement for the culture we’re stuck in now. Since civilized culture isn’t going to support anyone trying to take it apart, we need other systems of material, psychological, and emotional support.

This would be particularly important for an underground movement. Ideally they would have a community that knows their secrets and works alongside them, just as militaries do. Building that network will be difficult to do in secret, because if they’re observing tight security, how do they even find others who agree with them? But because there’s little one or two people can do by themselves, they’ll have to find ways to do it. That’s a problem of logistics, however, and it’s important to separate it from personal issues.

When I was doing illegal actions, I wanted people to notice me as a hardcore environmentalist, which under the circumstances was foolish and narcissistic to the point of madness. If you have issues like that—and lots of people do, in our bizarre and hurtful culture—you need to resolve them with self-reflection and therapy, not activism. The most elegant solution would be for your secret community to support and acknowledge you, to help you find the strength and solidarity you need to do hard and necessary work, but there are substitutes available all the same.

TS: You’ve been involved with aboveground environmental work in the years since your underground actions. What have you worked on, and what are you doing now?

MC: I first got involved with forestry issues—writing timber sale appeals and that sort of thing. Later I helped write petitions to protect species under the Endangered Species Act. I burned out on that, though, and it took me a long time to get drawn back in. Aboveground people need the support of a community, too—more than ever. Derrick Jensen’s book A Language Older Than Words clarified the global situation for me, answered many questions I had about why things are so difficult right now. It taught me to be aware that as civilized culture approaches its end, people are getting ever more self-absorbed, apathetic, and cruel. Those who are still able to feel need to stand by each other as well as they can.

When Deep Green Resistance came into being, it was a perfect fit, and I’ve been focused on helping build that movement. Susan Hyatt and I are doing an essay series on the psychology of civilization, and how to cultivate the mental health needed for resistance. I’m also interested in positive underground propaganda. Having stories to support what people are doing and thinking is important. It helps cultivate the confidence and courage that activists need. That’s why governments publish propaganda in wartime; it works.

TS: So you think propaganda can be helpful?

MC: Yes, I do. The word has a negative connotation for some good reasons, but I don’t think that attempting to influence thoughts and actions with media is necessarily bad, so long as it’s honest. Nazi Germany used propaganda, but so did George Orwell and John Steinbeck. If civilization is brought down—that is, if the systems responsible for social injustice and planetary destruction are permanently disabled—it will require a sustained effort for many years by people who choose to act against most everything they’ve been taught to believe, and a willingness to risk their freedom and lives to bring it about. Entirely new resistance cultures will be needed. They will require a lot of new stories to sustain a vision of who humans really are, and what our lives are for, how they relate to other living things. So far as I know there’s little in the way of writing, movies, any sort of media that attempts to do that.

Edward Abbey wrote some fun books, and they were all we had; so we went along hoping we’d have some of that fun and that everything might come out all right in the end. We no longer have that luxury for self-indulgence. I’m not saying humor doesn’t have its place—quite the opposite—but the situation of the planet and social situation of civilization is now far more dire than it was during Abbey’s time. Effective propaganda should reflect that—it should honestly appraise the circumstances and realistically compose a response, so would-be resisters can choose what their role is going to be.

This is important for everyone, but especially important for an underground. In World War II, the Allies distributed Steinbeck’s propaganda novel The Moon is Down throughout occupied Europe. It was a short, simple book about how a small town in Norway fought against the Nazis. It was so mild in tone that Steinbeck was accused by some in the US government of sympathizing with the enemy for his realistic portrayal of German soldiers as mere people in an awful situation, and not superhuman monsters. Yet the occupying forces would shoot anyone on the spot if they caught them with a copy of the book. Compare that to Abbey’s books, and you see how far short The Monkey Wrench Gang falls of the necessary task.

TS: Can you suggest any contemporary propaganda?

Derrick Jensen’s Endgame books are the best I can think of, and the book Deep Green Resistance. There’s some negative-example propaganda worth mentioning, too. The book A Friend of the Earth, by T.C. Boyle. The movies “The East” and “Night Moves” are both about underground activists, and they’re terrible movies, at least as propaganda for effective resistance. “The East” is about a private security firm that infiltrates a cell whose only goals are theater and revenge, and “Night Moves” is even worse, about two swaggering men and one unprepared woman who blow up a hydroelectric dam.

The message is, “Don’t mess with this stuff, or you’ll end up dead.” But these films do point out some common problems of groups with an anarchistic mindset: they tend to belittle women and they operate without a coherent strategy. They’re in it for the identity, for the adrenaline, for the hook-up prospects—all terrible reasons to engage. So I suppose they’re worth a look for how not to behave. So is the documentary film “If a Tree Falls,” about the Earth Liberation Front.

Social change movements can suffer from problems of immaturity and self-infatuation just like individuals can. Radical environmentalism, like so many leftist causes, is rife with it. Most of the Earth First!ers I knew back in the ‘90s were so proud of their partying prowess, you couldn’t spend any time with them without their getting wasted and droning on about it all the next day. One of the reasons I drifted away from that movement was it was so full of arrogant and judgmental people, who seemed to spend most of their time criticizing their colleagues for impure living because they use paper towels or drive an old pickup instead of a bicycle.

This can lead to ridiculous guilt-tripping pissing matches. It’s no wonder environmentalists have such a bad reputation among the working class, when they’re indulging in self-righteous nitpicking that’s really just a reflection of their own circumstantial advantages and lack of focus on effectively defending the land. Tell a working mother to mothball her dishwasher because you heard it’s inefficient, see how far you get. It’s one of the worst things you can say to anyone, especially because it reinforces the collective-burden notion of responsibility for environmental destruction. This is what those in power want us to think. Developers build new golf courses in the desert, and we pretend we’re making a difference by dry-brushing our teeth. Who cares who’s greener than thou? The world is being gutted in front of our eyes.

Interview continues here.

Time is Short: Reports, Reflections & Analysis on Underground Resistance is a bulletin dedicated to promoting and normalizing underground resistance, as well as dissecting and studying its forms and implementation, including essays and articles about underground resistance, surveys of current and historical resistance movements, militant theory and praxis, strategic analysis, and more. We welcome you to contact us with comments, questions, or other ideas at undergroundpromotion@deepgreenresistance.org

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Mar 8, 2015 | Property & Material Destruction, Repression at Home, Strategy & Analysis

In 1993 Michael Carter was arrested and indicted for underground environmental activism. Since then he’s worked aboveground, fighting timber sales and oil and gas leasing, protecting endangered species, and more. Today, he’s a member of Deep Green Resistance Colorado Plateau, and author of the memoir Kingfishers’ Song: Memories Against Civilization.

Time is Short spoke with him about his actions, underground resistance, and the prospects and problems facing the environmental movement. Due to the length of the interview, we’ve presented it in three installments; go to Part II here, and Part III here.

Time is Short: Can you give a brief description of what it was you did?

Michael Carter: The significant actions were tree spiking—where nails are driven into trees and the timber company warned against cutting them—and sabotaging of road building machinery. We cut down plenty of billboards too, and this got most of the media attention. We did this for about two years in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, about twenty actions. My brother Sean was also indicted. The FBI tried to round up a larger conspiracy, but that didn’t stick.

TS: How did you approach those actions? What was the context?

MC: We didn’t know a lot about environmental issues or political resistance, so we didn’t have much understanding of context. We had an instinctive dislike of clear cuts, and we had the book The Monkey Wrench Gang. Other people were monkeywrenching, that is, sabotaging industry to protect wilderness, so we had some vague ideas about tactics but no manual, no concrete theory. We knew what Earth First! was, although we weren’t members. It was a conspiracy only in the remotest sense. We had little strategy and the actions were impetuous. If we’d been robbing banks instead, we’d have been shot in the act.

Nor did we really understand how bad the problem was. We thought that deforestation was damaging to the land, but we didn’t get the depth of its implications and we didn’t link it to other atrocities. We just thought that we were on the extreme edge of the marginal issue of forestry. This was before many were talking about global warming or ocean acidification or mass extinction. It all seemed much less severe than now, and of course it was. The losses since then, of species and habitat and pollution, are terrible. No monkeywrenching I know of did anything significant to stop that. It was scattered, aimed at minor targets, and had no aboveground political movement behind it.

Clearcuts in the Swan Valley, MT near Loon Lake on the slope of Mission Mountains. Photo by George Wuerthner.

TS: What was the public response to your actions?

MC: They saw them as vandalism, mindlessly criminal, even if they were politically motivated. This was before 9/11, before the Oklahoma City bombing; the idea of terrorism wasn’t so powerful, so our actions weren’t taken nearly as seriously as they would be now.

We were charged by the state of Montana with criminal mischief and criminal endangerment. The state’s evidence was solid enough we thought we couldn’t win a trial, so we pled guilty on the chance the judge wouldn’t send us to prison. Our defense was to say, “We’re sorry we did it, it was motivated by sincerity but it was dumb.” And that was true. We were able to get our charges reduced from criminal endangerment to criminal mischief. I got a 19 year suspended prison sentence, Sean got 9 years suspended. We both had to pay a lot of money, some $40,000, but I only spent three months in county jail and Sean got out of a jail sentence altogether. We were lucky.

TS: As you said, this was before the obsessive fear of terrorism. How do you think that played into your trial and indictment, and how do you think it would be different today?

MC: Had it happened after any big terrorism event, they would have sent us to prison, there’s no doubt about that. States have to maintain a level of constant fear and prove themselves able to protect citizens.

The irony was, I’m not sure I wanted to be serious—there seemed to be something protective in not being all that effective, in being intentionally quixotic, in being a little cute about it. There was a particularly comical aspect to cutting down billboards, and that was helpful only when I was arrested. It made it look less like terrorism and more like reckless things I did when I was drunk, and a lot of people approved of it because they thought billboards were tacky. I want to emphasize that cutting down billboards is nothing I’d advise anyone to consider, only that a little bit of public approval made a surprising difference to my morale, and may have positively influenced sentencing. But the point, of course, is to be effective and not get caught in the first place. These days, if someone gets caught in underground actions, they will be in a lot more trouble than ever before.

TS: How did you get caught?

We left fingerprints and tire tracks, we rented equipment under our own names—like an acetylene torch used to cut down steel billboard posts—and we told people who didn’t need to know about it. We assumed we were safe if they didn’t catch us in the act and because our fingerprints weren’t on file, and we couldn’t have been more wrong. The cops can subpoena anyone’s fingerprints, and use that evidence for something in the past. The importance of security can’t be overstated—and we didn’t have any. Even with a couple rudimentary precautions, we might have saved ourselves the whole ordeal of getting caught. If we’d read the security chapter of Dave Foreman’s book Ecodefense, I don’t think we would have even come under suspicion. Anyone taking any action, above- or underground, needs to take the time to learn security well.

It’s not just saving yourself the anguish of arrest and prison time. If you’re rigorous about security, you might be able to have a real chance at changing how the future of the planet plays out. You can have no impact at all in a jail cell. In our case, we definitely could have stopped timber sales with tree spiking even though that tactic was extremely unpopular politically. It was seen as an act of violence against innocent lumber mill workers instead of a preventative measure to protect forests. The dilemma never got past that stage, though. We had little chance of having any reasoned tactical considerations—let alone making reasoned decisions—because we were always a little too afraid of being caught. With good reason, it turns out.

TS: What have you learned from your experience? Looking back on what you did all those years ago, what’s your perspective on your actions now? Is there anything you would have done differently?

MC: Well I definitely would have taken steps to not get caught. I would have picked my targets more carefully, and I would have entered into an understanding with myself that while my enemy is composed of people, it’s only a system, inhuman and relentless. It can’t be reasoned with; it has no sanity, no sense of morality, no love of anything. Its job is to consume. I would have tried to focus on that guiding fact, and not on the people running it or who were dependent on it. I would have tried to find the weaknesses in the system, and then attacked those.

I’d have tried not to allow my emotions to dictate my strategy or actions. Emotions might get me there in the first place—I don’t think you could get to such a desperate point without a strong emotional response—but once I arrived at the decision to act, I would have done everything I could to think like a soldier, find a competent group to join with, and pick expensive and hard-to-replace targets.

TS: I assume you didn’t just wake up one day and decide to attack bulldozers and billboards. What was your path from being apolitical to having the determination and the passion to do what you did?

MC: When I was struggling with high school, my brother loaned me a stack of Edward Abbey books, which presented the idea that wilderness is the real world, precious above all else. The other part was living in northwest Montana, where you see deforestation anywhere you look. You can’t not notice it, and there’s something about those scalped hills and skid trails and roads that triggers a visceral, angry response. It’s less abstract than atmospheric carbon or drift-net fishing. You don’t see those things the way you see denuded mountainsides. My family heated the house with wood, and we would sometimes get it out of slash piles in the middle of clearcuts. I had lots of firsthand exposure to deforested land. I wondered why the Sierra Club didn’t do something about it, how it could be allowed. We would occasionally go to Canada, and it was even worse up there. No one can feel despair like a teenager, and I had it in spades. If Greenpeace won’t stop this, I reasoned, well then I will.

I started building an identity around this, though, and that’s disastrous for a person choosing underground resistance. You naturally want others to know and appreciate your feelings and accomplishments, especially when you’re young, but the dilemma underground fighters face is that they must present another, blander identity to the world. That’s hard to do.

TS: You were fairly isolated in your actions, and you’ve emphasized the importance of a larger context. Do you see those two ideas connecting? Do you think saboteurs should be acting in a larger movement?

MC: I think saving the planet relies completely on the coordinated actions of underground cells coupled with an aboveground political movement that isn’t directly involved in underground actions. When I was underground, I had no hope of building a network, mostly because of a lack of emotional and political maturity. I also didn’t have the technological or strategic savvy, or a means of communicating with others. The actions themselves were mostly symbolic, and symbolic actions are a huge waste of risk. They’re a waste of political capital too. Most everyone is going to disagree with underground activism and it’s not going to change anyone’s mind about the policy issue—hardly anything will—so it has to count in the material realm. If people are ready and willing to risk their lives and their freedom then they should fight to win, not just to make some sort of abstract point.

TS: After you were arrested, what support—if any—did you receive from folks on the outside, and what support would you have wanted to receive?

MC: The most important support was financial, but there wasn’t a lot of it. Our plea bargain didn’t guarantee we wouldn’t go to prison. We were also worried that the feds would indict us for racketeering, an anti-Mafia charge with serious minimum sentencing. If we’d had more legal defense financing we’d of course have felt a lot more secure, but twenty years of reflection tells me we didn’t really deserve it considering how poorly we executed the actions, what little effect they caused.

That sounds like I’m being awfully hard on myself, and hindsight is always 20/20, but the point is that a legal crisis is exhausting and expensive. Your community will question whether your actions are worthy of the price they’ll have to pay if you’re caught. My actions were not.

Even so, I appreciated any sort of support. Hearing from the outside in jail is better than you’d believe. A lot of Earth First! Journal readers sent me anonymous letters. I wrote back and forth with one of the women who was jailed for noncooperation with a federal grand jury investigating the Animal Liberation Front in Washington. Seeing approving letters to the editor in the papers was also great. Just knowing that the whole world isn’t your enemy, that someone is thinking about you and appreciates what you did, is priceless.

Artwork by Stephanie McMillan

TS: Do you still think militant and illegal forms of direct action and sabotage are justified? Why?

MC: I do, yes. In an ideal world I don’t think violence is the best way to accomplish anything, but obviously this isn’t an ideal world. Our circumstances are getting worse and worse—overpopulation, pollution, oceanic dead zones, you name it—and any options for a decent and dignified future for humanity are dwindling day by day, so what choice does that leave us? Individual attempts at sustainable living won’t work so long as the industrial system is running. The dismantling of infrastructure is the most important missing piece right now. It’s where the system is most vulnerable, so it should be employed right away. It can be effective, but it has to be responsible, careful, and extraordinarily smart.

One of the reasons underground political actions are so unpopular is that they’re always presented as attacks on individuals, rather than on a system. I think it’s important to reframe sabotage as strikes on an unjust, destructive system, and that civilization is not us, and not the highest expression of human endeavor, but only an idea. Civilization is masquerading as humanity, but that’s not what it is. Civilization is only one sort of cultural plan, a way of creating unsustainably large human settlements, based entirely on agriculture which itself is completely unsustainable.

The argument that militant actions are counterproductive has a little bit of merit because the scale they’ve happened on hasn’t been large enough to have any impact. For example, the Earth Liberation Front burning SUV’s. You’re left with the political fallout, the mainstream activists distancing themselves and all the other bad stuff that comes with it, but you don’t have any measurable gain, in reducing carbon emissions, say. Sabotage needs to happen on a larger scale, against more expensive targets, to be impactful. Fighters need to think big. That’s how militaries accomplish their goals—by acting against systems. They blow up bridges, they take out buildings, they disable the enemy arsenal, they kill the enemy—that’s how they function. I agree activists don’t want to identify with militarism, but it’s foolhardy to not consider what’s actually going to get the job done, and militaries know how to do that. No moral code will matter if the biosphere collapses. Doctrinal non-violence isn’t going to have any relevance in a world that’s 20 degrees hotter than it is now.

I wish an effective movement could be nonviolent, but we just don’t have enough social cohesion to orchestrate that kind of thing. There’s so few of us who give a shit, and we’re scattered, isolated, and disenfranchised. We don’t have adequate numbers, influence, or power, and I don’t see that changing. Everywhere we look we’re losing, because we don’t have a movement that can say, “No. You’re not going to do that. We will stop this, whatever it takes,” and back that up. Aboveground activists need to advocate a lesser evil, to continually pose the question of what is worse: that some property was destroyed, or that sea shells are dissolving in acid oceans? Underground activists need to act that out. It’s not a rhetorical question.

We need to remember, too, that small numbers of people can engineer profound changes when their actions are wisely leveraged. Very few took part in the resistance movements of World War II, but they made all the difference to ultimately defeating the Axis.

Interview continues here.

Time is Short: Reports, Reflections & Analysis on Underground Resistance is a bulletin dedicated to promoting and normalizing underground resistance, as well as dissecting and studying its forms and implementation, including essays and articles about underground resistance, surveys of current and historical resistance movements, militant theory and praxis, strategic analysis, and more. We welcome you to contact us with comments, questions, or other ideas at undergroundpromotion@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 16, 2015 | Human Supremacy, Strategy & Analysis

By Lierre Keith and Derrick Jensen

Once, the environmental movement was about protecting the natural world from the insatiable demands of this extractive culture. Some of the movement still is: around the world grassroots activists and their organizations are fighting desperately to save this or that creature they love, this or that plant or fungi, this or that wild place.

Contrast this to what some activists are calling the conservation-industrial complex–big green organizations, huge “environmental” foundations, neo-environmentalists, some academics–which has co-opted too much of the movement into “sustainability,” with that word being devalued to mean “keeping this culture going as long as possible.” Instead of fighting to protect our one and only home, they are trying to “sustain” the very culture that is killing the planet. And they are often quite explicit about their priorities.

For example, the recent “An Open Letter to Environmentalists on Nuclear Energy,” signed by a number of academics, some conservation biologists, and other members of the conservation-industrial complex, labels nuclear energy as “sustainable” and argues that because of global warming, nuclear energy plays a “key role” in “global biodiversity conservation.” Their entire argument is based on the presumption that industrial energy usage is, like Dick Cheney said, not negotiable–it is taken as a given. And for what will this energy be used? To continue extraction and drawdown–to convert the last living creatures and their communities into the final dead commodities.

Their letter said we should let “objective evidence” be our guide. One sign of intelligence is the ability to recognize patterns: let’s lay out a pattern and see if we can recognize it in less than 10,000 years. When you think of Iraq, do you think of cedar forests so thick that sunlight never touches the ground? That’s how it was prior to the beginnings of this culture. The Near East was a forest. North Africa was a forest. Greece was a forest. All pulled down to support this culture. Forests precede us, while deserts dog our heels. There were so many whales in the Atlantic they were a hazard to ships. There were so many bison on the Great Plains you could watch for four days as a herd thundered by. There were so many salmon in the Pacific Northwest you could hear them coming for hours before they arrived. The evidence is not just “objective,” it’s overwhelming: this culture exsanguinates the world of water, of soil, of species, and of the process of life itself, until all that is left is dust.

Fossil fuels have accelerated this destruction, but they didn’t cause it, and switching from fossil fuels to nuclear energy (or windmills) won’t stop it. Maybe three generations of humans will experience this level of consumption, but a culture based on drawdown has no future. Of all people, conservation biologists should understand that drawdown cannot last, and should not be taken as a given when designing public policy–let alone a way of life.

It is long past time for those of us whose loyalties lie with wild plants and animals and places to take back our movement from those who use its rhetoric to foster accelerating ecocide. It is long past time we all faced the fact that an extractive way of life has never had a future, and can only end in biotic collapse. Every day this extractive culture continues, two hundred species slip into that longest night of extinction. We have very little time left to stop the destruction and to start the repair. And the repair might yet be done: grasslands, for example, are so good at sequestering carbon that restoring 75 percent of the planet’s prairies could bring atmospheric CO2 to under 330 ppm in fifteen years or less. This would also restore habitat for a near infinite number of creatures. We can make similar arguments about reforestation. Or consider that out of the more than 450 dead zones in the oceans, precisely one has repaired itself. How? The collapse of the Soviet Empire made agriculture unfeasible in the region near the Black Sea: with the destructive activity taken away, the dead zone disappeared, and life returned. It really is that simple.

You’d think that those who claim to care about biodiversity would cherish “objective evidence” like this. But instead the conservation-industrial complex promotes nuclear energy (or windmills). Why? Because restoring prairies and forests and ending empires doesn’t fit with the extractive agenda of the global overlords.

This and other attempts to rationalize increasingly desperate means to fuel this destructive culture are frankly insane. The fundamental problem we face as environmentalists and as human beings isn’t to try to find a way to power the destruction just a little bit longer: it’s to stop the destruction. The scale of this emergency defies meaning. Mountains are falling. The oceans are dying. The climate itself is bleeding out and it’s our children who will find out if it’s beyond hope. The only certainty is that our one and only home, once lush with life and the promise of more, will soon be a bare rock if we do nothing.

We the undersigned are not part of the conservation-industrial complex. Many of us are long-term environmental activists. Some of us are Indigenous people whose cultures have been living truly sustainably and respectfully with all our relations from long before the dominant culture began exploiting the planet. But all of us are human beings who recognize we are animals who like all others need livable habitat on a living earth. And we love salmon and prairie dogs and black terns and wild nature more than we love this way of life.

Environmentalism is not about insulating this culture from the effects of its world-destroying activities. Nor is it about trying to perpetuate these world-destroying activities. We are reclaiming environmentalism to mean protecting the natural world from this culture.

And more importantly, we are reclaiming this earth that is our only home, reclaiming it from this extractive culture. We love this earth, and we will defend our beloved.

You can sign on to this letter at: Open Letter to Reclaim Environmentalism

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 16, 2015 | Human Supremacy, Strategy & Analysis

By Anonymous / Deep Green Resistance UK

In retrospect, all revolutions seem inevitable. Beforehand, all revolutions seem impossible.

—Michael McFaul, U.S. National Security Council

When I talk to people about the Deep Green Resistance (DGR) Decisive Ecological Warfare (DEW) strategy to end the destructive culture we know as industrial civilisation, I get comments like “So you want a revolution.” Some include the word “armed” or “violent” before “revolution.” I explain that DGR is advocating for militant resistance to industrial civilisation that will involves sabotage of infrastructure. We we are not advocating for the harming of any human or non-human living beings.

There are a number of ways that groups can challenge those who rule: revolutions, coup d’etats, rebellions, terrorism, non-violent resistance, insurgency, guerrilla warfare and civil war. This article will explore what causes revolutions, the stages of revolutions, communist revolutions, anarchist revolutions, the automatic revolution theory, and if a revolution is likely now. In future articles, we will explore what we can learn from studying past and present insurgency, guerrilla warfare, and non-violent resistance.

Methods for Challenging Those Who Rule

In Coup d’etat: A Practical Handbook, Edward Luttwak describes a coup d’etats (coup) as a method that: “Operates in that area outside the government but within the state which is formed by the permanent and professional civil service, the armed forces and the police. The aim is to detach the permanent employees of the state from the political leadership, and this can not usually take place if the two are linked by political, ethnic or traditional loyalties.” [1] So it’s about separating the permanent bureaucrat machinery of the state from the political leadership. The top decision-making offices are seized without changing the system of their predecessors.

Luttwak makes a distinction between revolutions, civil wars, pronunciamiento (a form of military rebellion particular to Spain, Portugal and Latin America in the nineteenth century), putsch (led by high ranking military officers), and a war of national liberation/insurgency. He explains that coups use some elements of all of these, but unlike them may not necessarily be assisted by the masses or a military or armed force. Those attempting a coup will not be in charge of the armed forces at the start of the coup and will hope to win their support if the coup is going to be successful. They will also not initially control any tools of propaganda so can’t count on the support of the people. Luttwak is clear that coups are politically neutral, so the policies of the new government can’t be predicted to be “right”or “left.”

The political scientist Samuel P. Huntington identifies three classes of coup d’etat:

1. Breakthrough coup d’etat—a revolutionary army overthrows a traditional government and creates a new bureaucratic elite.

2. Guardian coup d’etat—The stated aim of such a coup is usually improving public order and efficiency, and ending corruption.

3. Veto coup d’etat—occurs when the army vetoes the people’s mass participation and social mobilisation in governing themselves.

A list of Coup d’etats from the present going back to BC 876 are listed here. Well known examples are the Nazis in Germany in 1933 and the Iranian Revolution, 1978-‘79.

A rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is any act by group that refuses to recognise, or seeks to overthrow, the authority of the existing government. They can use violent or non-violent methods. Any attempts that fails to change a regime are called rebellions. Uprisings are usually unarmed or minimally armed popular rebellions. Insurrections generally involve some degree of military training and organisation, and the use of military weapons and tactics by the rebels. [2]

DGR members would never consider carrying out or advocating for terrorism. Most governments conduct state terrorism on a daily basis via the police, army, and the prison system, and DGR members are working against this in our aboveground organising. In Insurgency & Terrorism: From Revolution to Apocalypse, Bard E. O’Neill defines terrorism as “the threat or use of physical coercion, primarily against noncombatants, especially civilians, to create fear in order to achieve various political objectives.” [3]

In Insurgency & Terrorism: From Revolution to Apocalypse, O’Neill defines Insurgency as a “struggle between a nonruling group and the ruling authorities in which the nonruling group consciously uses political resources (e.g. organisational expertise, propaganda, and demonstrations) and violence to destroy, reformulate, or sustain the basis of legitimacy of one or more aspects of politics.” Recent examples are in Iraq and Palestine. [4]

And guerrilla warfare is described by O’Neill as “highly mobile hit-and-run attacks by lightly to moderately armed groups that seek to harass the enemy and gradually erode his will and capability. Guerrillas place a premium on flexibility, speed and deception.” Examples include Umkhonto we Sizwe, the armed wing of the African National Congress (ANC) in South Africa, and the Zapatistas in Mexico. [5]

In War of the Flea: The Classic Study of Guerrilla Warfare, Robert Taber describes a guerrilla fighter:

When we speak of the guerrilla fighter, we are speaking of the political partisan, an armed civilian whose principle weapon is not his rifle or his machete, but his relationship to the community, the nation in and for which he fights. Insurgency, or guerrilla war, is the agency of radical social or political change, it is the face and the right arm of the revolution. [6]

In The Politics of Nonviolent Action, Gene Sharp defines nonviolent action as “the belief that the exercise of power depends on the consent of the ruled who, by withdrawing that consent, can control and even destroy the power of their opponent. In other words, nonviolent action is a technique used to control, combat and destroy the opponent’s power by nonviolent means of wielding power.” [7] Well known nonviolent campaigns include the Gandhi’s Salt March campaign in 1930 and the US Civil Rights Movement of 1954–68.

A civil war is a conventional war between organised groups in the same state, which can include conflict between elements in the national armed forces. Both sides aim to take control of the country or region.

What Causes Revolutions?

Each of these methods or a combination of all may lead to a revolution. I find the word “revolution” a tired and overused concept. Everyone has a slightly different understanding of what a revolution is. The online Oxford dictionary defines a revolution as: “A forcible overthrow of a government or social order, in favor of a new system,” a complete change to the existing political system.

In Revolutions: A Very Short Introduction, Jack A. Goldstone defines a revolution “in terms of both observed mass mobilization and the institutional change, and a driving ideology carrying a vision of social justice. Revolution is the forcible overthrow of a government through mass mobilization (whether military or civilian or both) in the name of social justice, to create new political institutions.” Goldstone describes two great visions of revolutions, the heroic uprising of the downtrodden masses guided by leaders to overthrow unjust rulers. The second vision is eruptions of popular anger that produce violence and chaos. He observes that the history of revolutions shows both visions are present and they are vary widely. [8]

Professor Crane Brinton’s 1938 book The Anatomy of Revolution compares the English Revolution/Civil War, the American Revolution, the French Revolution, and the Russian Revolution of 1917. He identified a number of conditions that are present as causes for major revolutions. Many of the conditions are present now, including: general discontent; hopeful people accepting less than they hoped for; growing bitterness between social classes; governments not responding to the needs of society, and not managing their finances effectively.

Goldstone identifies five elements that result in a stable society becoming unstable, where the conditions for revolution are then favorable. These are:

1. poor management of finances;

2. alienation and opposition among the elites;

3. revolutionary mobilisation builds around some form of popular anger at injustice;

4. an ideology develops that mobalises diverse groups and presents a shared narrative of resistance;

5. a revolution requires favorable international relations.

In industrialised countries governments are clearly mismanaging their finances. This is combined with a general feeling of inequality in our society and the need for social change.

There still needs to be an event or events to lead to a revolution. Goldstone describes structural and transient causes. Structural causes are long-term and large-scale trends that erode social structures and relationships. Transient causes are chance events, by individuals or groups, which highlight the impact of longer term trends and encourage further resistance.

Structural Causes

1. Demographic change is a common structural change. Rapid population growth can produce large numbers of youth cohorts, who struggle to find work and are easily attracted to new ideologies for social change.

2. A shift in the pattern of international relations. War and international economic competition can weaken governments and empower new groups. Both of these causes can result in a number of states in a regional becoming unstable. Then if an event in one state results in a revolution, it can result in revolutionary outbreaks in others. These are known as revolutionary waves.

3. Uneven economic development. If the poor and middles classes fall noticeably far behind the elite, this may create popular grievances.

4. A new pattern of exclusion or discrimination against particular groups develops. For example if up-and-coming groups are excluded from joining the elite, they may look at other options.

5. The evolution of “personalist regimes” where the rulers hang onto power, relying on a small circle of corrupt family members and cronies. This will weaken or alienate the professional military and business elites.

Transient Causes

Transient causes are sudden events that push a society to become unstable. These can include: spikes in inflation, especially in food prices; defeat in war; and riots and demonstrations that challenge state authority. If the state is then seen to be repressing ordinary members of society with just grievances, it can lead to popular perceptions of the regime as dangerous, illegitimate, and unjust.

Transient events occur regularly in many countries and do not result in revolutions. Structural causes are needed to create the underlying instability, which allows the transient event to cause people to turn against the state more openly and in large numbers. [9]

The Stages of Revolutions

Brinton identifies revolutions having four stages: the Old Order, the Rule of the Moderates, then the Reign of Terror, and finally the Thermidorian Reaction (return of stability).

Goldstone also identifies four similar different stages: state breakdown, post revolution power struggle, new government consolidation, and a second radical phase some years after. He observes that strong and skillful leaders are needed to take advantage of the structural and transient causes if a revolution is to be successful. He identifies visionary and organisational leaders. Visionary leaders are prolific writers and generally brilliant public speakers, who articulate the faults of the old society and make a powerful case for change. Organisational leaders are great organisers of revolutionary armies and/or bureaucracies. They work out how to put the visionary leaders’ idea into practice. In some cases individuals act as both the visionary and organisational leader. [10]

Communist Revolutions

Revolutionary socialism is a view that revolution is necessary to transition from capitalism to socialism. This is not necessarily a violent event, but instead it is the seizure of political power by mass movements of the working class so they control the state. Social/Proletarian revolutions are generally advocated by socialists, communists, and some anarchists. Revolutionary socialism includes a number of social and political movements that may define “revolution” differently from one another.

A communist revolution is a proletarian revolution, generally inspired by the ideas of Marxism to replace capitalism with communism, with socialism as an intermediate stage. Marx believed that proletarian revolutions will inevitably happen in all capitalist countries.

Chapters 22 and 23 of Robert B Asprey’s War in the Shadows: The Guerrilla in History give a very useful summary of the Russian Revolution from 1825 to the October Revolution in 1917, then up to the end of the Russian Civil War in 1922. The Russian people had suffered many years of terrible conditions resulting in protests, uprisings and then harsh repression by a number of Russian Czars. Following Russia’s disastrous involvement in World War One, a St. Petersburg army garrison mutinied, leading to February Revolution and the end of the monarchy. A Provisional Government formed that continued Russia’s involvement in the war. The people had no desire to keep fighting but the new government did not seem to understand this. The October Revolution followed when the Bolsheviks, led by Lenin and Trotsky, took over the government. A civil war followed until 1922, with Lenin’s Red Army fighting to regain control of Russia against the Imperialist White armies and regional guerrilla dissidents, who were supported with troops from Britain, America, France and Italy. By 1922 the allied forces had left Russia and the White armies had been defeated. Lenin was left with a devastated Russia, industry at a standstill, inflation, agriculture at an all-time low and large peasant revolts in 1920-‘21. Droughts caused widespread famine in 1921-‘22, and it’s estimated that five million people died from starvation. [11]

There is a clear pattern of communist revolutions resulting in authoritarian, repressive governments. And most communist states have eventually had to give into Capitalism. The World Revolution that Marx dreamed of looks very unlikely.

Anarchist Revolutions

Anarchism is a political philosophy that aims to create stateless societies often defined as self-governed voluntary institutions. The International Anarchist Federation (IFA) fights for “the abolition of all forms of authority whether economic, political, social, religious, cultural or sexual. The construction of a free society, without classes or States or frontiers, founded on anarchist federalism and mutual aid. The action of the IAF—IFA shall always be based on direct action, against parliamentarism and reformism, both on a theoretical and practical point of view.”

Insurrectionary Anarchism is based on belief that the state will not wither away: “Attack is the refusal of mediation, pacification, sacrifice, accommodation and compromise in struggle. It is through acting and learning to act, not propaganda, that we will open the path to insurrection—although obviously analysis and discussion have a role in clarifying how to act. Waiting only teaches waiting; in acting one learns to act. Yet it is important to note that the force of an insurrection is social, not military.” [12]

Michael Schmidt’s recent book The Cartography of Revolutionary Anarchism describes five waves of Anarchism. [13] He describes a number of Anarchist Revolutions: the Mexican Revolution 1910-‘20, the Anarchist uprising against the Bolsheviks 1917-‘21, Ukrainian Revolution and Free Territory/Makhnovia 1917-‘21, Manchurian Revolution in Northeast Asia 1929-‘31, Spanish Revolution 1936-‘39, and the Chiapas conflict/Zapatista uprising in southern Mexico 1994.

In 2007 a group calling itself the Invisible Committee released The Coming Insurrection. It describes the decline of capitalism and civilisation through seven circles of alienation: self, social relations, work, the economy, urbanity, the environment, and civilisation. It then goes on to describe how a revolutionary struggle may evolve through “communes” – a general term to mean any group of people coming together to take on a task – to form into an underground network out of sight and then carry out acts of sabotage and confrontation with the state.

Automatic Revolution Theory

Ted Trainer’s recent article [14] encourages the Transition movement to think more radically and describes the “automatic revolution” theory: “If more and more people join in gradually building up alternative systems, then eventually it will all somehow have added up to revolution and the existence of the new society we want to see.”

This sums up the majority of the liberal environmental movement very well; a sort of blind faith that if enough positive stuff is done and the movement gets enough people on board, it will lead to a sustainable society. It doesn’t seem to consider the ongoing, wholesale destruction happening to the natural world or that we are fast approaching—or may have passed—the point of no return for runaway climate change. Most liberal environmentalists want a new sustainable society with all the comforts and conveniences that they currently have. So, by default, they want to reform the current system, which is nonrevolutionary. Reformists aim to change policies that determine how economic, psychological, and political benefits of a society are distributed. That’s not going to work for the environmental crisis.

To have a truly sustainable society, industrial civilisation needs to end. Otherwise, it will consume all resources that can be extracted from the earth and result in a devastated world that can not support life. The wars, death and suffering in the medium term will be horrific. Also it’s not that it’s just going to get hot—and it is going to get hot, even if we stop emitting greenhouse gases now—but climate change is going to cause the seasons to become erratic, and that’s a serious problem for growing food.

Revolution now?

A number of writers, journalists and celebrities are now calling for revolt or revolution in response to the environmental crisis. Of course each has their own interpretation of what “revolution” means. Naomi Klein recently observed that how climate science is telling us all to revolt. Chris Hedges argues that the system is unreformable and our only choice is mass civil disobedience. Comedian Russell Brand is now talking about the need for a revolution.

Robert Steele, former Marine and ex-CIA case officer, believes that the preconditions for revolution exist in most western countries: “What revolution means in practical terms is that balance has been lost and the status quo ante is unsustainable. There are two ‘stops’ on greed to the nth degree: the first is the carrying capacity of Earth, and the second is human sensibility. We are now at a point where both stops are activating.”

DGR Strategy—Decisive Ecological Warfare (DEW)

Where does DGR’s Strategy Decisive Ecological Warfare fit into all this? First, are the preconditions for revolution present? Well it depends where you look. If we focus on the industrialised world and work from Brinton and Goldstone’s criteria, and Steele’s analysis, then yes, that’s where we’re heading. What form might it take—violent or nonviolent, mass movement or guerrilla warfare?

Noam Chomsky believes that if a revolution is going to be possible then “it has to have dedicated support by a large majority of the population. People who have come to realize that the just goals that they are trying to attain cannot be attained within the existing institutional structure because they will be beaten back by force. If a lot of people come to that realization then they might say well we’ll go beyond, what’s called reformism, the effort to introduce changes within the institutions that exist. At that point the questions at least arise. But we are so remote from that point that I don’t even see any point speculating about it and we may never get there.”

We in DGR would agree with Chomsky that in the West, we are far away from a large majority of people calling for a just, truly sustainable world and accepting the radical consequences of this. The environmental movement has been trying to tackle the issues using a range of nonviolent methods for decades and is failing. So we urgently need to look at what other methods could work.

Militant Resistance—Sabotage

In 1960 Nelson Mandela was tasked by the ANC in setting up its military wing called Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK). I find his thoughts on the direction MK could take very useful:

In planning the direction and form that MK would take, we considered four types of violent activities: sabotage, guerrilla warfare, terrorism and open revolution. For a small and fledgling army, open revolution was inconceivable. Terrorism inevitably reflected poorly on those who used it, undermining any public support it might otherwise garner. Guerrilla warfare was a possibility, but since the ANC had been reluctant to embrace violence at all, it made sense to start with the form of violence that inflicted the least harm against individuals: sabotage.

Because Sabotage did not involve loss of life, it offered the best hope for reconciliation among the races afterwards… Sabotage had the added virtue of requiring the least manpower.

[15]

If we look at today’s situation in industrialised countries, guerrilla warfare and open revolution are not possible and terrorism is not acceptable, which leaves sabotage. The DEW strategy is made up of four phases, with an aboveground movement and underground network working in tandem. The aboveground groups indirectly support the underground network, although there is no direct contact between the two. The aboveground movement is made up from many groups working on land restoration, ending oppression, legally working to stop environmental destruction, community resilience including meeting basic needs and alternative institutions. An underground network would be made up of a variety of autonomous cells to carry out acts of sabotage against destructive infrastructure. The fossil fuels need to be left in the ground and the destruction of the natural world needs to stop. (include stuff about veterans saying DEW could work).

We do not believe there is any way to reform this insane culture. DGR is calling for revolutionary, systemic change. We would prefer a nonviolent transition to a truly sustainable society, but because this looks unlikely industrial civilisation needs to end and the most effective way to do this is through the sabotage of infrastructure by an underground network. If successful, DGR’s devolutionary strategy will indirectly result in a complete change to the existing political system, a reset. It is indirect because we are not advocating for armed militancy to overthrow any governments like past revolutions or for a strategy of attrition. But instead for underground cells to strategically target infrastructure weak points to cause system disruption and cascading system failures, resulting in the collapse of industrial activity and civilisation. It’s time for all environmentalists to decide if they want systemic change or to keep trying to reform the unreformable.

Finally, I’d like to quote Frank Coughlin’s description of the Zapatistas idea of revolution:

It is based in the “radical” idea that the poor of the world should be allowed to live, and to live in a way that fits their needs. They fight for their right to healthy food, clean water, and a life in commune with their land. It is an ideal filled with love, but a specific love of their land, of themselves, and of their larger community. They fight for their land not based in some abstract rejection of destruction of beautiful places, but from a sense of connectedness. They are part of the land they live on, and to allow its destruction is to concede their destruction. They have shown that they are willing to sacrifice, be it the little comforts of life they have, their liberty, or their life itself.

Endnotes

1. P19 – Luttwak, Edward. (1988) Coup d’etat: A Practical Handbook. Cambridge, USA. Harvard University Press.

2. P8 – Goldstone, Jack A. (2014) Revolutions: A Very Short Introduction, New York, Oxford University Press

3. P33 – O’Neill, Bard E. (2005) Insurgency & Terrorism: From Revolution to Apocalypse. 2nd Ed. Washington, D.C. Potomac Books.

4. P15 – O’Neill, Bard E. (2005) Insurgency & Terrorism: From Revolution to Apocalypse. 2nd Ed. Washington, D.C. Potomac Books.

5. P35 – O’Neill, Bard E. (2005) Insurgency & Terrorism: From Revolution to Apocalypse. 2nd Ed. Washington, D.C. Potomac Books.

6. P10 – Taber, Robert. (2002) War of the Flea: The Classic Study of Guerrilla Warfare. Washington, D.C. Potomac Books.

7. P4 – Sharp, Gene. (1973) The Politics of Nonviolent Action. Boston. Porter Sargent Publisher.

8. P1 – Goldstone, Jack A. (2014) Revolutions: A Very Short Introduction, New York, Oxford University Press

9. P20 – Goldstone, Jack A. (2014) Revolutions: A Very Short Introduction, New York, Oxford University Press

10. P26 – Goldstone, Jack A. (2014) Revolutions: A Very Short Introduction, New York, Oxford University Press

11. P284 Asprey, Robert B. (1975) War in the Shadows: The Guerrilla in History. New York. Doubledday & Company, Inc.

12. From Do or Die Issue 10. http://www.eco-action.org/dod/no10/anarchy.htm. Also read more about Insurrectionary Anarchism here: http://www.ainfos.ca/06/jul/ainfos00232.html).

13. Schmidt, Michael. (2013) Cartography of Revolutionary Anarchism. Oakland. AK Press. Anarchist Revolutionary Waves. The First Wave 1868-1894, Second Wave 1895-1923, Third Wave 1924-1949, Fourth Wave 1950-1989 and the Fifth Wave 1989 to the Present

14. Ted Trainer article – Transition Townspeople, We Need To Think About Transition: Just Doing Stuff Is Far From Enough! http://blog.postwachstum.de/transition-townspeople-we-need-to-think-about-transition-just-doing-stuff-is-far-from-enough-20140801

15. Mandela, Nelson. (1995) Long Walk to Freedom: The Autobiography of Nelson Mandela. London. Abacus.

Time is Short: Reports, Reflections & Analysis on Underground Resistance is a biweekly bulletin dedicated to promoting and normalizing underground resistance, as well as dissecting and studying its forms and implementation, including essays and articles about underground resistance, surveys of current and historical resistance movements, militant theory and praxis, strategic analysis, and more. We welcome you to contact us with comments, questions, or other ideas at undergroundpromotion@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 7, 2015 | Climate Change, Strategy & Analysis

By Kim Hill / Deep Green Resistance Australia

Naomi Klein’s latest book, This Changes Everything, is based on the premise that capitalism is the cause of the climate crisis, and to avert catastrophe, capitalism must go. The proposed solution is a mass movement that will win with arguments that undermine the capitalist system by making it morally unacceptable.

This premise has many flaws. It fails to acknowledge the roots of capitalism and climate change, seeing them as independent issues that can be transformed without taking action to address the underlying causes. Climate change cannot be avoided by building more infrastructure and reforming the economy, as is suggested in the book. The climate crisis is merely a symptom of a deeper crisis, and superficial solutions that act on the symptoms will only make the situation worse. Human-induced climate change started thousands of years ago with the advent of land clearing and agriculture, long before capitalism came into being. The root cause—a culture that values domination of people and land, and the social and physical structures created by this culture—needs to be addressed for any action on capitalism or climate to be effective.

I’ve long been baffled by the climate movement. When 200 species a day are being made extinct, oceans and rivers being drained of fish and all life, unpolluted drinking water being largely a thing of the past, and nutritious food being almost inaccessible, is climate really where we should focus our attention? It seems a distraction, a ‘look, what’s that in the sky?’ from those that seek to profit from taking away everything that sustains life on the only planet we have. By directing our thoughts, discussions and actions towards gases in the upper atmosphere and hotly debated theories, rather than immediate needs for basic survival of all living beings, those in power are leading us astray from forming a resistance movement that could ensure the continuation of life on Earth.

This book is a tangle of contradictions. An attempt to unravel the contradictions and understand the thinking behind these arguments is what drew me in to reading it, but in the end I was left confused, with a jumble of mismatched ideas, vague goals, and proposals to continue with the same disjointed tactics that have never worked in the past.