by DGR News Service | Sep 19, 2021 | Agriculture, Repression at Home, Strategy & Analysis

This article originally appeared in Climate & Capitalism. It is part 2 of a series, read part 1 here.

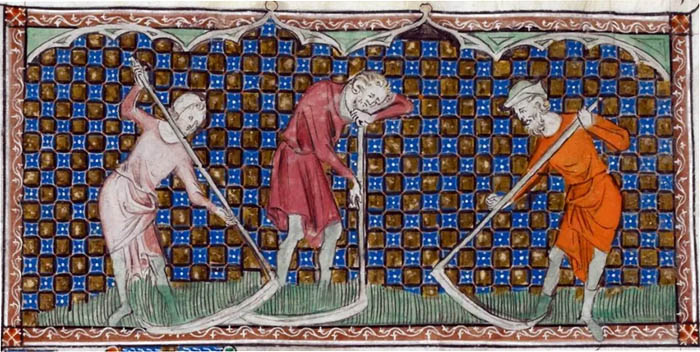

Featured image: Tenants harvest the landlord’s grain

“The expropriation of the mass of the people from the soil forms the basis of the capitalist mode of production.” (Karl Marx)

by Ian Angus

“The ground of the parish is gotten up into a few men’s hands, yea sometimes into the tenure of one or two or three, whereby the rest are compelled either to be hired servants unto the other or else to beg their bread in misery from door to door.” (William Harrison, 1577)[1]

In 1549, tens of thousands of English peasants fought — and thousands died — to halt and reverse the spread of capitalist farming that was destroying their way of life. The largest action, known as Kett’s Rebellion, has been called “the greatest practical utopian project of Tudor England and the greatest anticapitalist rising in English history.”[2]

On July 6, peasants from Wymondham, a market town in Norfolk, set out across country to tear down hedges and fences that divided formerly common land into private farms and pastures. By the time they reached Norwich, the second-largest city in England, they had been joined by farmers, farmworkers and artisans from many other towns and villages. On July 12, as many as 16,000 rebels set up camp on Mousehold Heath, near the city. They established a governing council with representatives from each community, requisitioned food and other supplies from nearby landowners, and drew up a list of demands addressed to the king.

Over the next six weeks, they twice invaded and captured Norwich, repeatedly rejected Royal pardons on the grounds that they had done nothing wrong, and defeated a force of 1,500 men sent from London to suppress them. They held out until late August, when they were attacked by some 4,000 professional soldiers, mostly German and Italian mercenaries, who were ordered by the Duke of Warwick to “take the company of rebels which they saw, not for men, but for brute beasts imbued with all cruelty.”[3] Over 3,500 rebels were massacred, and their leaders were tortured and beheaded.

The Norwich uprising is the best documented and lasted longest, but what contemporaries called the Rebellions of Commonwealth involved camps, petitions and mass assemblies in at least 25 counties, showing “unmistakable signs of coordination and planning right across lowland England.”[4] The best surviving statement of their objectives is the 29 articles adopted at Mousehold Heath. They were listed in no particular order, but, as historian Andy Wood writes, “a strong logic underlay them.”

“The demands drawn up at the Mousehold camp articulated a desire to limit the power of the gentry, exclude them from the world of the village, constrain rapid economic change, prevent the over-exploitation of communal resources, and remodel the values of the clergy. … Lords were to be excluded from common land and prevented from dealing in land. The Crown was asked to take over some of the powers exercised by lords, and to act as a neutral arbiter between lord and commoner. Rents were to be fixed at their 1485 level. In the most evocative phrase of the Norfolk complaints, the rebels required that the servile bondmen who still performed humiliating services upon the estates of the Duchy of Lancaster and the former estates of the Duke of Norfolk be freed: ‘We pray that all bonde men may be made Free, for god made all Free with his precious blode sheddyng’.”[5]

The scope and power of the rebellions of 1549 demonstrate, as nothing else can, the devastating impact of capitalism on the lives of the people who worked the land in early modern England. The radical changes known to history by the innocuous label enclosure peaked in two long waves: during the rise of agrarian capitalism in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and during the consolidation of agrarian capitalism in the eighteenth and nineteenth.

This article discusses the sixteenth century origins of what Marx called “the systematic theft of communal property.”[6]

Sheep devour people

In part one we saw that organized resistance and reduced population allowed English peasants to win lower rents and greater freedom in the 1400s. But they didn’t win every fight — rather than cutting rents and easing conditions to attract tenants, some landlords forcibly evicted their smaller tenants and leased larger farms, at increased rents, to well-off farmers or commercial sheep graziers. Caring for sheep required far less labor than growing grain, and the growing Flemish cloth industry was eager to buy English wool.

Local populations declined as a result, and many villages disappeared entirely. As Sir Thomas More famously wrote in 1516, sheep had “become so greedy and fierce that they devour human beings themselves. They devastate and depopulate fields, houses and towns.”[7]

For more than a century, enclosure and depopulation — the words were almost always used together — were major social and political concerns for England’s rulers. As early as 1483, Edward V’s Lord Chancellor, John Russell, criticized “enclosures and emparking … [for] driving away of tenants and letting down of tenantries.”[8] In the same decade, the priest and historian John Rous condemned enclosure and depopulation, and identified 62 villages and hamlets within 12 miles of his home in Warwickshire that were “either destroyed or shrunken,” because “lovers or inducers of avarice” had “ignominiously and violently driven out the inhabitants.” He called for “justice under heavy penalties” against the landlords responsible.[9]

Thirty years later, Henry VIII’s advisor Sir Thomas More condemned the same activity, in more detail.

“The tenants are ejected; and some are stripped of their belongings by trickery or brute force, or, wearied by constant harassment, are driven to sell them. One way or another, these wretched people — men, women, husbands, wives, orphans, widows, parents with little children and entire families (poor but numerous, since farming requires many hands) — are forced to move out. They leave the only homes familiar to them, and can find no place to go. Since they must have at once without waiting for a proper buyer, they sell for a pittance all their household goods, which would not bring much in any case. When that little money is gone (and it’s soon spent in wandering from place to place), what finally remains for them but to steal, and so be hanged — justly, no doubt — or to wander and beg? And yet if they go tramping, they are jailed as idle vagrants. They would be glad to work, but they can find no one who will hire them. There is no need for farm labor, in which they have been trained, when there is no land left to be planted. One herdsman or shepherd can look after a flock of beasts large enough to stock an area at used to require many hands to make it grow crops.”[10]

Many accounts of the destruction of commons-based agriculture assume that that enclosure simply meant the consolidation of open-field strips into compact farms, and planting hedges or building fences to demark the now-private property. In fact, as the great social historian R.H. Tawney pointed out in his classic study of The Agrarian Problem in the Sixteenth Century, in medieval and early modern England the word enclosure “covered many different kinds of action and has a somewhat delusive appearance of simplicity.”[11] Enclosure might refer to farmers trading strips of manor land to create more compact farms, or to a landlord unilaterally adding common land to his demesne, or to the violent expulsion of an entire village from land their families had worked for centuries.

Even in the middle ages, tenant farmers had traded or combined strips of land for local or personal reasons. That was called enclosure, but the spatial rearrangement of property as such didn’t affect common rights or alter the local economy.[12] In the sixteenth century, opponents of enclosure were careful to exempt such activity from criticism. For example, the commissioners appointed to investigate illegal enclosure in 1549 received this instruction:

“You shall enquire what towns, villages, and hamlets have been decayed and laid down by enclosures into pastures, within the shire contained in your instructions …

“But first, to declare unto you what is meant by the word enclosure. It is not taken where a man encloses and hedges his own proper ground, where no man has commons, for such enclosure is very beneficial to the commonwealth; it is a cause of great increase of wood: but it is meant thereby, when any man has taken away and enclosed any other men’s commons, or has pulled down houses of husbandry, and converted the lands from tillage to pasture. This is the meaning of this word, and so we pray you to remember it.”[13]

As R.H. Tawney wrote, “What damaged the smaller tenants, and produced the popular revolts against enclosure, was not merely enclosing, but enclosing accompanied by either eviction and conversion to pasture, or by the monopolizing of common rights. … It is over the absorption of commons and the eviction of tenants that agrarian warfare — the expression is not too modern or too strong — is waged in the sixteenth century.”[14]

An unsuccessful crusade

Tudor Monarchs

| Henry VII |

1485–1509 |

| Henry VIII |

1509–1547 |

| Edward VI |

1547–1553 |

| Mary I |

1553–1558 |

| Elizabeth I |

1558–1603 |

The Tudor monarchs who ruled England from 1485 to 1603 were unable to halt the destruction of the commons and the spread of agrarian capitalism, but they didn’t fail for lack of trying. A general Act Against Pulling Down of Towns was enacted in 1489, just four years after Henry VII came to power. Declaring that “in some towns two hundred persons were occupied and lived by their lawful labours [but] now two or three herdsmen work there and the rest are fallen in idleness,”[15] the Act forbade conversion of farms of 20 acres or more to pasture, and ordered landlords to maintain the existing houses and buildings on all such farms.

Further anti-enclosure laws were enacted in 1515, 1516, 1517, 1519, 1526, 1534, 1536, 1548, 1552, 1555, 1563, 1589, 1593, and 1597. In the same period, commissions were repeatedly appointed to investigate and punish violators of those laws. The fact that so many anti-enclosure laws were enacted shows that while the Tudor government wanted to prevent depopulating enclosure, it was consistently unable to do so. From the beginning, landlords simply disobeyed the laws. The first Commission of Enquiry, appointed in 1517 by Henry VIII’s chief advisor Thomas Wolsey, identified 1,361 illegal enclosures that occurred after the 1489 Act was passed.[16] Undoubtedly more were hidden from the investigators, and even more were omitted because landlords successfully argued that they were formally legal.[17]

The central government had multiple reasons for opposing depopulating enclosure. Paternalist feudal ideology played a role — those whose wealth and position depended on the labor of the poor were supposed to protect the poor in return. More practically, England had no standing army, so the king’s wars were fought by peasant soldiers assembled and led by the nobility, but evicted tenants would not be available to fight. At the most basic level, fewer people working the land meant less money collected in taxes and tithes. And, as we’ll discuss in Part Three, enclosures caused social unrest, which the Tudors were determined to prevent.

Important as those issues were, for a growing number of landlords they were outweighed by their desire to maintain their income in a time of unprecedented inflation, driven by debasement of the currency and the influx of plundered new world silver. “During the price revolution of the period 1500-1640, in which agricultural prices rose by over 600 per cent, the only way for landlords to protect their income was to introduce new forms of tenure and rent and to invest in production for the market.”[18]

Smaller gentry and well-off tenant farmers did the same, in many cases more quickly than the large landlords. The changes they made shifted income from small farmers and farmworkers to capitalist farmers, and deepened class divisions in the countryside.

“Throughout the sixteenth century the number of smaller lessees shrank, while large leaseholding, for which accumulated capital was a prerequisite, became increasingly important. The sixteenth century also saw the rise of the capitalist lessee who was prepared to invest capital in land and stock. The increasing divergence of agricultural prices and wages resulted in a ‘profit inflation’ for capitalist farmers prepared and able to respond to market trends and who hired agricultural labor.”[19]

As we’ve seen, the Tudor government repeatedly outlawed enclosures that removed tenant farmers from the land. The laws failed because enforcement depended on justices of the peace, typically local gentry who, even if they weren’t enclosers themselves, wouldn’t betray neighbors and friends who were. Occasional Commissions of Enquiry were more effective — and so were hated by landlords — but their orders to remove enclosures and reinstate former tenants were rarely obeyed, and fines could be treated as a cost of doing business.

From monks to investors

The Tudors didn’t just fail to halt the advance of capitalist agriculture, they unintentionally gave it a major boost. As Marx wrote, “the process of forcible expropriation of the people received a new and terrible impulse in the sixteenth century from the Reformation, and the consequent colossal spoliation of church property.”[20]

Between 1536 and 1541, seeking to reform religious practice and increase royal income, Henry VIII and his chief minister Thomas Cromwell disbanded nearly 900 monasteries and related institutions, retired their occupants, and confiscated their lands and income.

This was no small matter — together, the monasteries’ estates comprised between a quarter and a third of all cultivated land in England and Wales. If he had kept it, the existing rents and tithes would have tripled the king’s annual income. But in 1543 Henry, a small-country king who wanted to be a European emperor, launched a pointless and very expensive war against Scotland and France, and paid for it by selling off the properties he had just acquired. When Henry died in 1547, only a third of the confiscated monastery property remained in royal hands; almost all that remained was sold later in the century, to finance Elizabeth’s wars with Spain.[21]

The sale of so much land in a short time transformed the land market and reshaped classes. As Christopher Hill writes, “In the century and a quarter after 1530, more land was bought and sold in England than ever before.”

“There was relatively cheap land to be bought by anyone who had capital to invest and social aspirations to satisfy…. By 1600 gentlemen, new and old, owned a far greater proportion of the land of England than in 1530 — to the disadvantage of crown, aristocracy and peasantry alike.

“Those who acquired land in significant quantity became gentlemen, if they were not such already … Gentlemen leased land — from the king, from bishops, from deans and chapters, from Oxford and Cambridge colleges — often in order to sub-let at a profit. Leases and reversions sometimes lay two deep. It was a form of investment…. The smaller gentry gained where big landlords lost, gained as tenants what others lost as lords.”[22]

As early as 1515, there were complaints that farmland was being acquired by men not from the traditional landowning classes — “merchant adventurers, clothmakers, goldsmiths, butchers, tanners and other artificers who held sometimes ten to sixteen farms apiece.”[23] When monastery land came available, owning or leasing multiple farms, known as engrossing, became even more attractive to urban businessmen with capital to spare. Some no doubt just wanted the prestige of a country estate, but others, used to profiting from their investments, moved to impose shorter leases and higher rents, and to make private profit from common land.

A popular ballad of the time expressed the change concisely:

“We have shut away all cloisters,

But still we keep extortioners.

We have taken their land for their abuse,

But we have converted them to a worse use.”[24]

Hysterical exaggeration?

Early in the 1900s, conservative economist E.F. Gay — later the first president of the Harvard Business School — wrote that 16th century accounts of enclosure were wildly exaggerated. Under the influence of “contemporary hysterics” and “the excited sixteenth century imagination,” a small number of depopulating enclosures were “magnified into a menacing social evil, a national calamity responsible for dearth and distress, and calling for drastic legislative remedy.” Popular opposition reflected not widespread hardship, but “the ignorance and hide-bound conservatism of the English peasant,” who combined “sturdy, admirable qualities with a large admixture of suspicion, cunning and deceit.” [25]

Gay argued that the reports produced by two major commissions to investigate enclosures show that the percentage of enclosed land in the counties investigated was just 1.72% in 1517 and 2.46% in 1607. Those small numbers “warn against exaggeration of the actual extent of the movement, against an uncritical acceptance of the contemporary estimate both of the greatness and the evil of the first century and a half of the ‘Agrarian Revolution.’”[26]

Ever since, Gay’s argument has been accepted and repeated by right-wing historians eager to debunk anything resembling a materialist, class-struggle analysis of capitalism. The most prominent was Cambridge University professor Sir Geoffrey Elton, whose bestselling book England Under the Tudors dismissed critics of enclosure as “moralists and amateur economists” for whom landlords were convenient scapegoats. Despite the complaints of such “false prophets,” enclosers were just good businessmen who “succeeded in sharing the advantages which the inflation offered to the enterprising and lucky.” And even then, “the whole amount of enclosure was astonishingly small.”[27]

The claim that enclosure was an imaginary problem is improbable, to say the least. R.H. Tawney’s 1912 response to Gay applies with full force to Elton and his conservative co-thinkers.

“To suppose that contemporaries were mistaken as to the general nature of the movement is to accuse them of an imbecility which is really incredible. Governments do not go out of their way to offend powerful classes out of mere lightheartedness, nor do large bodies of men revolt because they have mistaken a ploughed field for a sheep pasture.”[28]

The reports that Gay analyzed were important, but far from complete. They didn’t cover the whole country (only six counties in 1607), and their information came from local “jurors” who were easily intimidated by their landlords. Despite the dedication of the commissioners, it is virtually certain that their reports understated the number and extent of illegal enclosures.

And, as Tawney pointed out, enclosure as a percentage of all land doesn’t tell us much about its economic and social impact — the real issue is how much farmed land was enclosed.

In 1979, John Martin reanalysed Gay’s figures for the most intensely farmed areas of England, the ten Midlands counties where 80% of all enclosures took place. He concluded that in those counties over a fifth of cultivated land had been enclosed by 1607, and that in two counties enclosure exceeded 40%. Contrary to Elton’s claim, those are not “astonishingly small” figures — they support Martin’s conclusion that “the enclosure movement must have had a fundamental impact upon the agrarian organization of the Midlands peasantry in this period.” [29]

It’s important to bear in mind that enclosure, as narrowly defined by Tudor legislation and Inquiry commissions, was only part of the restructuring that was transforming rural life. W.G, Hoskins emphasizes that in The Age of Plunder:

“The importance of engrossing of farms by bigger men was possibly a greater social problem than the much more noisy controversy over enclosures, if only because it was more general. The enclosure problem was largely confined to the Midlands … but the engrossing of farms was going on all the time all over the country.”[30]

George Yerby elaborates.

“Enclosure was one manifestation of a broader and less formal development that was working in exactly the same direction. The essential basis of the change, and of the new economic balance, was the consolidation of larger individual farms, and this could take place with or without the technical enclosure of the fields. This also serves to underline the force of commercialization as the leading trend in changes in the use and occupation of the land during this period, for the achievement of a substantial marketable surplus was the incentive to consolidate, and it did not always require the considerable expense of hedging.”[31]

More large farms meant fewer small farms, and more people who had no choice but to work for others. The twin transformations of primitive accumulation — stolen land becoming capital and landless producers becoming wage workers — were well underway.

Notes

[1] William Harrison, The Description of England: The Classic Contemporary Account of Tudor Social Life, ed. Georges Edelen (Folger Shakespeare Library, 1994), 217.

[2] Jim Holstun, “Utopia Pre-Empted: Ketts Rebellion, Commoning, and the Hysterical Sublime,” Historical Materialism 16, no. 3 (2008), 5.

[3] Quoted in Martin Empson, Kill All the Gentlemen: Class Struggle and Change in the English Countryside (Bookmarks Publications, 2018), 162.

[4] Diarmaid MacCulloch and Anthony Fletcher, Tudor Rebellions, 6th ed. (Routledge, 2016), 70.

[5] Andy Wood, Riot, Rebellion and Popular Politics in Early Modern England (Palgrave, 2002), 66-7.

[6] Karl Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, (Penguin Books, 1976), 886.

[7] Thomas More, Utopia, trans. Robert M. Adams, ed. George M. Logan, 3rd ed. (Cambridge University Press, 2016), 19.

[8] A. R. Myers, ed., English Historical Documents, 1327-1485, vol. 4 (Routledge, 1996), 1031. “Emparking” meant converting farmland into private forests or parks, where landlords could hunt.

[9] Ibid., 1029.

[10] More, Utopia, 19-20.

[11] R. H. Tawney, The Agrarian Problem in the Sixteenth Century (Lector House, 2021 [1912]), 7.

[12] Tawney, Agrarian Problem, 110.

[13] R. H. Tawney and E. E. Power, eds., Tudor Economic Documents, Vol. 1. (Longmans, Green, 1924), 39, 41. Spelling modernized.

[14] Tawney, Agrarian Problem, 124, 175.

[15] Quoted in M. W. Beresford, “The Lost Villages of Medieval England,” The Geographical Journal 117, no. 2 (June 1951), 132. Spelling modernized.

[16] Spencer Dimmock, “Expropriation and the Political Origins of Agrarian Capitalism in England,” in Case Studies in the Origins of Capitalism, ed. Xavier Lafrance and Charles Post (Palgrave MacMillan, 2019), 52.

[17] The Statute of Merton, enacted in 1235, allowed landlords to take possession of and enclose common land, so long as sufficient remained to meet customary tenants’ rights. In the 1500s that long-disused law provided a loophole for enclosing landlords who defined “sufficient” as narrowly as possible.

[18] Martin, Feudalism to Capitalism, 131.

[19] Martin, Feudalism to Capitalism, 133.

[20] Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, 883.

[21] Perry Anderson, Lineages of the Absolutist State (Verso, 1979), 124-5.

[22] Christopher Hill, Reformation to Industrial Revolution: A Social and Economic History of Britain, 1530-1780 (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1967), 47-8.

[23] Joan Thirsk, “Enclosing and Engrossing, 1500-1640,” in Agricultural Change: Policy and Practice 1500-1750, ed. Joan Thirsk (Cambridge University Press, 1990), 69.

[24] Quoted in Thomas Edward Scruton, Commons and Common Fields (Batoche Books, 2003 [1887]), 73.

[25] Edwin F. Gay, “Inclosures in England in the Sixteenth Century,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 17, no. 4 (August 1903), 576-97; “The Inclosure Movement in England,” Publications of the American Economic Association 6, no. 2 (May 1905), 146-159.

[26] Edwin F. Gay, “The Midland Revolt and the Inquisitions of Depopulation of 1607,” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 18 (1904), 234, 237.

[27] G. R. Elton, England under the Tudors (Methuen, 1962), 78-80.

[28] Tawney, Agrarian Problem, 166.

[29] John E. Martin, Feudalism to Capitalism: Peasant and Landlord in English Agrarian Development (Macmillan Press, 1986), 132-38.

[30] W. G. Hoskins, The Age of Plunder: The England of Henry VIII 1500-1547, Kindle ed. (Sapere Books, 2020 [1976]), loc. 1256.

[31] George Yerby, The Economic Causes of the English Civil War (Routledge, 2020), 48.

by DGR News Service | Sep 18, 2021 | Agriculture, Repression at Home, Strategy & Analysis, Worker Exploitation

This article originally appeared in Climate & Capitalism.

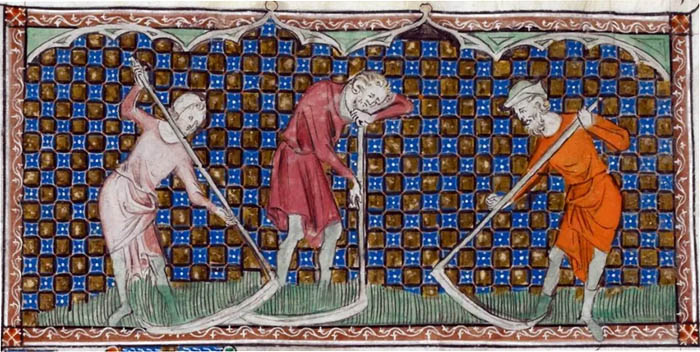

Featured image: Harvesting grain in the 1400s

Editor’s note: We are no Marxists, but we find it important to look at history from the perspective of the usual people, the peasants, and the poor, since liberal historians tend to follow the narrative of endless progress and neglect all the violence and injustice this “progress” was and is based on. Garrett Hardin’s annoying but very influential essay “The Tragedy of the Commons” is a good example, and we are thankful to the author for debunking it.

“All progress in capitalist agriculture is a progress in the art, not only of robbing the worker, but of robbing the soil.” (Karl Marx)

Articles in this series:

Commons and classes before capitalism

‘Systematic theft of communal property’

Against Enclosure: The Commonwealth Men

Dispossessed: Origins of the Working Class

Against Enclosure: The Commoners Fight Back

by Ian Angus

To live, humans must eat, and more than 90% of our food comes directly or indirectly from soil. As philosopher Wendell Berry says, “The soil is the great connector of lives…. Without proper care for it we can have no community, because without proper care for it we can have no life.”[1]

Preventing soil degradation and preserving soil fertility ought to be a global priority, but it isn’t. According to the United Nations, a third of the world’s land is now severely degraded, and we lose 24 billion tonnes of fertile soil every year. More than 1.3 billion people depend on food from degraded or degrading agricultural land.[2] Even in the richest countries, almost all food production depends on massive applications of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides that further degrade the soil and poison the environment.

In Karl Marx’s words, “a rational agriculture is incompatible with the capitalist system.”[3] To understand why that is, we need to understand how capitalist agriculture emerged from a very different system.

****

For almost all of human history, almost all of us lived and worked on the land. Today, most of us live in cities.

It is hard to overstate how radical that change is, or how quickly it happened. Two hundred years ago, 90% of the world’s population was rural. Britain became the world’s first majority-urban country in 1851. As recently as 1960, two-thirds of the world’s people still lived in rural areas. Now it’s less than half, and only half of those are farmers.

Between the decline of feudalism and the rise of industrial capitalism, rural society was transformed by the complex of processes that are collectively known as enclosure. The separation of most people from the land, and the concentration of land ownership in the hands of a tiny minority, were revolutionary changes in the ways that humans lived and work. It happened in different ways and at different times in different parts of the world, and is still going on today.

Our starting point is England, where what Marx labelled “so-called primitive accumulation” first occurred.

Common Fields, Common Rights

In medieval and early-modern England, most people were poor, but they were also self-provisioning — they obtained their essential needs directly from the land, which was a common resource, not private property as we understand the concept.

No one actually knows when or how English common farming systems began. Most likely they were brought to England by Anglo-Saxon settlers after Roman rule ended. What we know for sure is that common field agriculture was widespread, in various forms, when English feudalism was at its peak in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

The land itself was held by landlords, directly or indirectly from the king. A minor gentry family might hold and live on just one manor — roughly equivalent to a township — while a top aristocrat, bishop or monastery could hold dozens. The people who actually worked the land, often including a mix of unfree serfs and free peasants, paid rent and other fees in labor, produce or (later) cash, and had, in addition to the use of arable land, a variety of legal and traditional rights to use the manor’s resources, such as grazing animals on common pasture, gathering firewood, berries and nuts in the manor forest, and collecting (gleaning) grain that remained in the fields after harvest.

“Common rights were managed, divided, and redivided by the communities. These rights were predicated on maintaining relations and activities that contributed to the collective reproduction. No feudal lord had rights to the land exclusive of such customary rights of the commoners. Nor did they have the right to seize or engross the common fields as their own domain.”[4]

Field systems varied a great deal, but usually a manor or township included both the landlord’s farm (demesne) and land that was farmed by tenants who had life-long rights to use it. Most accounts only discuss open field systems, in which each tenant cultivated multiple strips of land that were scattered through the arable fields so no one family had all the best soil, but there were other arrangements. In parts of southwestern England and Scotland, for example, farms on common arable land were often compact, not in strips, and were periodically redistributed among members of the commons community. This was called runrig; a similar arrangement in Ireland was called rundale.

Most manors also had shared pasture for feeding cattle, sheep and other animals, and in some cases forest, wetlands and waterways.

Though cooperative, these were not communities of equals. Originally, all of the holdings may have been about the same size but in time considerable economic differentiation took place.[5] A few well-to-do tenants held land that produced enough to sell in local markets; others (probably a majority in most villages) had enough land to sustain their families with a small surplus in good years; others with much less land probably worked part-time for their better-off neighbors or for the landlord. “We can see this stratification right across the English counties in Domesday Book of 1086, where at least one-third of the peasant population were smallholders. By the end of the thirteenth century this proportion, in parts of southeastern England, was over a half.”[6]

As Marxist historian Rodney Hilton explains, the economic differences among medieval peasants were not yet class differences. “Poor smallholders and richer peasants were, in spite of the differences in their incomes, still part of the same social group, with a similar style of life, and differed from one to the other in the abundance rather than the quality of their possessions.”[7] It wasn’t until after the dissolution of feudalism in the fifteenth century that a layer of capitalist farmers developed.

Self-Management

If we were to believe an influential article published in 1968, commons-based agriculture ought to have disappeared shortly after it was born. In “The Tragedy of the Commons,” Garrett Hardin argued that commoners would inevitably overuse resources, causing ecological collapse. In particular, in order to maximize his income, “each herdsman will try to keep as many cattle as possible on the commons,” until overgrazing destroys the pasture, and it supports no animals at all. “Freedom in a commons brings ruin to all.”[8]

Since its publication in 1968, Hardin’s account has been widely adopted by academics and policy makers, and used to justify stealing indigenous peoples’ lands, privatizing health care and other social services, giving corporations ‘tradable permits’ to pollute the air and water, and more. Remarkably, few of those who have accepted Hardin’s views as authoritative notice that he provided no evidence to support his sweeping conclusions. He claimed that “tragedy” was inevitable, but he didn’t show that it had happened even once.[9]

Scholars who have actually studied commons-based agriculture have drawn very different conclusions. “What existed in fact was not a ‘tragedy of the commons’ but rather a triumph: that for hundreds of years — and perhaps thousands, although written records do not exist to prove the longer era — land was managed successfully by communities.”[10]

The most important account of how common-field agriculture in England actually worked is Jeanette Neeson’s award-winning book, Commoners: Common Right, Enclosure and Social Change in England, 1700-1820. Her study of surviving manorial records from the 1700s showed that the common-field villagers, who met two or three times a year to decide matters of common interest, were fully aware of the need to regulate the metabolism between livestock, crops and soil.

“The effective regulation of common pasture was as significant for productivity levels as the introduction of fodder crops and the turning of tilled land back to pasture, perhaps more significant. Careful control allowed livestock numbers to grow, and, with them, the production of manure. … Field orders make it very clear that common-field villagers tried both to maintain the value of common of pasture and also to feed the land.”[11]

Village meetings selected “juries” of experienced farmers to investigate problems, and introduce permanent or temporary by-laws. Particular attention was paid to “stints” — limits on the number of animals allowed on the pasture, waste, and other common land. “Introducing a stint protected the common by ensuring that it remained large enough to accommodate the number of beasts the tenants were entitled to. It also protected lesser commoners from the commercial activities of graziers and butchers.”[12]

Juries also set rules for moving sheep around to ensure even distribution of manure, and organized the planting of turnips and other fodder plants in fallow fields, so that more animals could be fed and more manure produced. The jury in one of the manors that Neeson studied allowed tenants to pasture additional sheep if they sowed clover on their arable land — long before scientists discovered nitrogen and nitrogen-fixing, these farmers knew that clover enriched the soil.[13]

And, given present-day concerns about the spread of disease in large animal feeding facilities, it is instructive to learn that eighteenth century commoners adopted regulations to isolate sick animals, stop hogs from fouling horse ponds, and prevent outside horses and cows from mixing with the villagers’ herds. There were also strict controls on when bulls and rams could enter the commons for breeding, and juries “carefully regulated or forbade entry to the commons of inferior animals capable of inseminating sheep, cows or horses.”[14]

Neeson concludes, “the common-field system was an effective, flexible and proven way to organize village agriculture. The common pastures were well governed, the value of a common right was well maintained.”[15]

Commons-based agriculture survived for centuries precisely because it was organized and managed democratically by people who were intimately involved with the land, the crops and the community. Although it was not an egalitarian society, in some ways it prefigured what Karl Marx, referring to a socialist future, described as “the associated producers, govern[ing] the human metabolism with nature in a rational way.”[16]

Class Struggles

That’s not to say that agrarian society was tension free. There were almost constant struggles over how the wealth that peasants produced was distributed in the social hierarchy. The nobility and other landlords sought higher rents, lower taxes and limits on the king’s powers, while peasants resisted landlord encroachments on their rights, and fought for lower rents. Most such conflicts were resolved by negotiation or appeals to courts, but some led to pitched battles, as they did in 1215 when the barons forced King John to sign Magna Carta, and in 1381 when thousands of peasants marched on London to demand an end to serfdom and the execution of unpopular officials.

Historians have long debated the causes of feudalism’s decline: I won’t attempt to resolve or even summarize those complex discussions here.[17] Suffice it to say that by the early 1400s in England, the feudal aristocracy was much weakened. Peasant resistance had effectively ended hereditary serfdom and forced landlords to replace labor-service with fixed rents, while leaving common field agriculture and many common rights in place. Marx described the 1400s and early 1500s, when peasants in England were winning greater freedom and lower rents, as “a golden age for labor in the process of becoming emancipated.”[18]

But that was also a period when longstanding economic divisions within the peasantry were increasing. W.G. Hoskins described the process in his classic history of life in a Midland village.

“During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries there emerged at Wigston what may be called a peasant aristocracy, or, if this is too strong a phrase as yet, a class of capitalist peasants who owned substantially larger farms and capital resources than the general run of village farmers. This process was going on all over the Midlands during these years …”[19]

Capitalist peasants were a small minority. Agricultural historian Mark Overton estimates that “in the early sixteenth century, around 80 per cent of farmers were only growing enough food for the needs of their family household.” Of the remaining 20%, only a few were actual capitalists who employed laborers and accumulated ever more land and wealth. Nevertheless, by the 1500s two very different approaches to the land co-existed in many commons communities.

“The attitudes and behavior of farmers producing exclusively for their own needs were very different from those farmers trying to make a profit. They valued their produce in terms of what use it was to them rather than for its value for exchange in the market. … Larger, profit orientated, farmers were still constrained by soils and climate, and by local customs and traditions, but also had an eye to the market as to which crop and livestock combinations would make them most money.”[20]

As we’ll see, that division eventually led to the overthrow of the commons.

Primitive Accumulation

For Marx, the key to understanding the long transition from agrarian feudalism to industrial capitalism was “the process which divorces the worker from the ownership of the conditions of his own labor,” which itself involved “two transformations … the social means of subsistence and production are turned into capital, and the immediate producers are turned into wage-laborers.”[21]

“Nature does not produce on the one hand owners of money or commodities, and on the other hand men possessing nothing but their own labor-power. This relation has no basis in natural history, nor does it have a social basis common to all periods of human history. It is clearly the result of a past historical development, the product of many economic revolutions, of the extinction of a whole series of older formations of social production.”[22]

A decade before Capital was published, Marx summarized that historical development in an early draft.

“It is … precisely in the development of landed property that the gradual victory and formation of capital can be studied. … The history of landed property, which would demonstrate the gradual transformation of the feudal landlord into the landowner, of the hereditary, semi-tributary and often unfree tenant for life into the modern farmer, and of the resident serfs, bondsmen and villeins who belonged to the property into agricultural day laborers, would indeed be the history of the formation of modern capital.”[23]

In Section VIII of Capital Volume 1, titled “The So-Called Primitive Accumulation of Capital,” he expanded that paragraph into a powerful and moving account of the historical process by which the dispossession of peasants created the working class, while the land they had worked for millennia became the capitalist wealth that exploited them. It is the most explicitly historical part of Capital, and by far the most readable. No one before Marx had researched the subject so thoroughly — Harry Magdoff once commented that on re-reading it, he was immediately impressed by the depth of Marx’s scholarship, by “the amount of sheer digging, hard work, and enormous energy in the accumulated facts that show up in his sentences.”[24]

Since Marx wrote Capital, historians have published a vast amount of research on the history of English agriculture and land tenure — so much that a few decades ago, it was fashionable for academic historians to claim that Marx got it all wrong, that the privatization of common land was a beneficial process for all concerned. That view has little support today. Of course it would be very surprising if subsequent research didn’t contradict Marx in some ways, but while his account requires some modification, especially in regard to regional differences and the tempo of change, Marx’s history and analysis of the commons remains essential reading.[25]

*****

The next installments in this series will discuss how, in two great waves of social change, landlords and capitalist farmers “conquered the field for capitalist agriculture, incorporated the soil into capital, and created for the urban industries the necessary supplies of free and rightless proletarians.”[26]

To be continued ….

[1] Wendell Berry, Wendell Berry: Essays 1969-1990, ed. Jack Shoemaker (Library of America, 2019), 317.

[2] https://www.unccd.int/news-events/better-land-use-and-management-critical-achieving-agenda-2030-says-new-report

[3] Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, trans. David Fernbach, vol. 3, (Penguin Books, 1981), 216

[4] John Bellamy Foster, Brett Clark, and Hannah Holleman, “Marx and the Commons,” Social Research (Spring 2021), 2-3.

[5] See “Reasons for Inequality Among Medieval Peasants,” in Rodney Hilton, Class Conflict and the Crisis of Feudalism: Essays in Medieval Social History (Hambledon Press, 1985), 139-151.

[6] Rodney Hilton, Bond Men Made Free: Medieval Peasant Movements and the English Rising of 1381 (Routledge, 2003 [1973]), 32.

[7] Rodney Hilton, Bond Men Made Free, 34.

[8] Garrett Hardin, The Tragedy of the Commons, Science, December 13, 1968.

[9] Ian Angus, The Myth of the Tragedy of the Commons, Climate & Capitalism, August 25, 2008; Ian Angus, Once Again: ‘The Myth of the Tragedy of the Commons’, Climate & Capitalism, November 3, 2008.

[10] Susan Jane Buck Cox, No Tragedy of the Commons, Environmental Ethics 7, no. 1 (1985), 60.

[11] J. M. Neeson, Commoners: Common Right, Enclosure and Social Change in England, 1700-1820 (Cambridge University Press, 1993), 113.

[12] J. M. Neeson, Commoners, 117.

[13] J. M. Neeson, Commoners, 118-20.

[14] J. M. Neeson, Commoners, 132.

[15] J. M. Neeson, Commoners, 157.

[16] Karl Marx, Capital Volume 3, trans. David Fernbach, (Penguin Books, 1981), 959.

[17] For an insightful summary and critique of the major positions in those debates, see Henry Heller, The Birth of Capitalism: A Twenty-First Century Perspective (Pluto Press, 2011).

[18] Karl Marx, Grundrisse, trans. Martin Nicolaus (Penguin Books, 1973), 510.

[19] W. G. Hoskins, The Midland Peasant: The Economic and Social History of a Leicestershire Village (Macmillan., 1965), 141.

[20] Mark Overton, Agricultural Revolution in England: The Transformation of the Agrarian Economy, 1500-1850 (Cambridge University Press, 1996), 8, 21.

[21] Karl Marx, Capital Volume, 1, 874.

[22] Karl Marx, Capital Volume 1, 273.

[23] Karl Marx, Grundrisse, 252-3.

[24] Harry Magdoff, “Primitive Accumulation and Imperialism,” Monthly Review (October 2013), 14.

[25] “The So-Called Primitive Accumulation” — Chapters 26 through 33 of Capital Volume 1 — can be read on the Marxist Internet Archive, beginning here. The somewhat better translation by Ben Fowkes occupies pages 873 to 940 of the Penguin edition.

[26] Karl Marx, Capital Volume 1, 895.

by DGR News Service | Sep 14, 2021 | Alienation & Mental Health, Education, Strategy & Analysis

This article is from the blog buildingarevolutionarymovement.

This post lists and challenges, debunks, pulls apart the following myths of capitalism:

- there is no alternative to capitalism

- capitalism is the only system that provides individual and economic freedom

- everything is better under capitalism

- as capitalism increases the size of the economy, everyone benefits

- free-market capitalism is the best way to run the global economy

- capitalist economic theory is the best

- capitalism maintains low taxes, which is good for workers and businesses

- capitalism promotes equality, work hard and you’ll get rich

- capitalism fits well with human nature

- capitalism and democracy work well together

- capitalism gradually balances differences across countries through free markets and free trade.

There is a liberal capitalist myth about progress. A determinist (set path forwards) view that things will continue to get better. I completely disagree with this perspective and it is clearly wrong if you look at history, esp the last 40 years. I will describe and challenge this myth in a future post.

I would like to start with a quote from 23 Things They Dont Tell You About Capitalism by Ha-Joon Chang:

“Most countries have introduced free-market policies over the last three decades – privatization of state-owned industrial and financial firms, deregulation of finance and industry, liberalization of international trade and investment, and reduction in income taxes and welfare payments. These policies, their advocates admitted, may temporarily create some problems, such as rising inequality, but ultimately they will make everyone better off by creating a more dynamic and wealthier society. The rising tide lifts all boats together, was the metaphor.

The result of these policies has been the polar opposite of what was promised. Forget for a moment the financial meltdown, which will scar the world for decades to come. Prior to that, and unbeknown to most people, free-market policies had resulted in slower growth, rising inequality and heightened instability in most countries. In many rich countries, these problems were masked by huge credit expansion; thus the fact that US wages had remained stagnant and working hours increased since the 1970s was conveniently fogged over by the heady brew of credit-fuelled consumer boom. The problems were bad enough in the rich countries, but they were even more serious for the developing world. Living standards in Sub-Saharan Africa have stagnated for the last three decades, while Latin America has seen its per capita growth rate fall by two-thirds during the period. There were some developing countries that grew fast (although with rapidly rising inequality) during this period, such as China and India, but these are precisely the countries that, while partially liberalizing, have refused to introduce full-blown free-market policies.

Thus, what we were told by the free-marketeers – or, as they are often called, neo-liberal economists – was at best only partially true and at worst plain wrong…the ‘truths’ peddled by free-market ideologues are based on lazy assumptions and blinkered visions, if not necessarily self-serving notions.”[1]

Myth – there is no alternative to capitalism

The argument goes that there is no viable alternative economic system. Centrally controlled governments have been tried and failed. Capitalism isn’t perfect but it’s all we’ve got. [2]

Simplistically this is an argument against planned economies which I will deal with in the free market capitalism section below. The main two examples of communist planned economies are the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China. There are many different forms of communism and these are authoritarian examples. They only came to exist and survive in the violent 20th century because they had strong leadership and then used military force to defend themselves against capitalist nations that attempted to destroy them. There is of course more to their survival than this but that is for another post. I’m not in the slightest defending the horrific violence they directed to their citizens. Critics of these experiments do not acknowledge all the positive things that we can learn from the Soviet Union – self-management, collectivisation, new housing processes, increases in literacy. [3]

What I want to focus on here is that if capitalism is genuinely the only naturally existing economic system, then why do capitalists have to constantly crush any alternatives. Because, capitalists see these embryonic alternatives as a threat to their wealth, dominance and control. This is done either through extreme media manipulation and propaganda or with violence and killings. This post gives three examples of capitalists crushing alternatives: the Copenhagen squatting movement, New Age Travellers in the UK, and the US-backed 1973 military coup of the socialist government of Salvador Allende in Chile. Other examples are the tens of thousands killed after the defeat of the Paris Commune in 1871 [4], German Revolution 1918-19, the EU drastic threats against the Syriza Greek government in 2015, and the demonisation of Jeremy Corbyn.

Myth – capitalism is the only system that provides individual and economic freedom

The moral argument for capitalism is based on individual freedom being a natural right that pre-exists society. Capitalist society is valued and justified because it benefits humans and enhances economic freedom, instead of limiting it.

This individual and economic freedom is a limited form of freedom. In the #ACFM episode – Trip 10 How It Feels to Be Free, several forms of freedom are discussed. These include comparing the liberal, conservative, radical and authoritarian traditions and their relationship to freedom [5]. They also discussed Isaiah Berlin’s Two Concepts of Liberty – positive and negative [6]. The negative concept is freedom from constraint to do what you want. This is described as the ‘Jeremy Clarkson concept of freedom’ or the ‘anti-woke concept of freedom [7] The positive idea is a freedom to do something and for many, this means that the material conditions have to be created, which resulted in the post-war welfare state. [8]

Myth – everything is better under capitalism

The arguement goes that capitalism has resulted in improved basic standards of living, reduction in poverty and increased life expectancy. There is also the argument that Western capitalist countries have the happiest populations because they can consume whatever products and services they like.

The truth behind this myth is that capitalism results in economic growth, which has come at huge costs – see the economic growth myths below. The myth is that capitalism intentionally results in better living standards for workers and the general population. This relates to the liberal myth about liberal progress (see a future post on this). Any reform or improvement in the living standards of workers and the general population has to be fought for by people and groups (trade unions, social movements or in parliament) who want these improvements. Historically movements challenged capitalism for higher wages which resulted in longer life expectancy and a decline in infectious diseases. The capitalists certainly don’t want these reforms if it means improved rights for workers and limits their ability to increase their profits. The capitalists are of course more than happy to use these reforms as examples of how good capitalism is, when in fact they resisted them and work to undo them. Some capitalists practice a form of Victoria philanthropy but still want to exploit their workers. In recent years life expectancy in Britain and the US has started to decline due to austerity and other reasons. [9]

And to quote Ha-Joon Chang:

“The average US citizen does have greater command over goods and services than his counterpart in any other country in the world except Luxemburg. However, given the country’s high inequality, this average is less accurate in representing how people live than the averages for other countries with a more equal income distribution. Higher inequality is also behind the poorer health indicators and worse crime statistics of the US. Moreover, the same dollar buys more things in the US than in most other rich countries mainly because it has cheaper services than in other comparable countries, thanks to higher immigration and poorer employment conditions. Furthermore, Americans work considerably longer than Europeans. Per hour worked, their command over goods and services is smaller than that of several European countries. While we can debate which is a better lifestyle – more material goods with less leisure time (as in the US) or fewer material goods with more leisure time (as in Europe) – this suggests that the US does not have an unambiguously higher living standard than comparable countries.” [10]

In terms of happiness, people are not stupid. They understand that they don’t have any influence on the direction of society, that things are going to be worse for future generations but there isn’t anything they can do about it. Buying more stuff and going on more holidays is a consolation prize that stops people looking for real change. Also, the number of antidepressant prescriptions doubled between 2008 and 2018, not a sign that people are happy.

Myth – as capitalism increases the size of the economy, everyone benefits

Capitalism results in exponential economic growth, so the arguement goes that this allows companies and individuals to benefit. This relates to the idea of, ‘A rising tide lifts all boats’ and ‘trickle-down economics‘ , where if the rich get richer, then this will benefit everyone.

And to quote Ha-Joon Chang:

“The above idea, known as ‘trickle-down economics’, stumbles on its first hurdle. Despite the usual dichotomy of ‘growth-enhancing pro-rich policy’ and ‘growth-reducing pro- poor policy’, pro-rich policies have failed to accelerate growth in the last three decades. So the first step in this argument – that is, the view that giving a bigger slice of pie to the rich will make the pie bigger – does not hold. The second part of the argument – the view that greater wealth created at the top will eventually trickle down to the poor – does not work either. Trickle down does happen, but usually its impact is meagre if we leave it to the market.” [11]

Myth – free-market capitalism is the best way to run the global economy

Capitalism produces a wide range of goods and services based on what is wanted or can solve a problem. It is argued that capitalism is economically efficient because it creates incentives to provide goods and services efficiently. The competitive market forces companies to improve how they are organised and use resources efficiently. [12]

This needs to be broken down into several arguments: the instability of capitalism, free-market vs state planning, free-market economics has only been applied in non-Western countries, corporations need to be regulated, where technology innovation happens, the impact of unlimited economic growth on the environment/planet.

Instability

Since the 1970s government have focused on ensuring price stability by managing inflation. This has not resulted in the stability of the world economy as the 2008 financial crisis shows. [13] Instability and crisis are part of the capitalist economic system. It is a cycle that starts when the memory of past economic crises fade and financial institutions figure out ways to circumvent the regulations that were put in place to stop them happening again. Rising asset prices reduce the cost of borrowing, resulting in market euphoria and risks being underestimated. Lots of money is being made and everyone wants their share of the growing economic boom (Richard Wolff Financial Panics, then and now in Capitalism Hits the Fan). Capitalism also needs crises so that businesses and wealth are destroyed, which lays the foundations for the next cycle of economic growth to start. This is known as ‘creative destruction‘.

There is also the argument that financial markets need to become more efficient so they can respond to changing opportunities and grow faster. Basically that there should not be any state restrictions on financial markets.

And to quote Ha-Joon Chang in 23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism:

“The problem with financial markets today is that they are too efficient. With recent financial ‘innovations’ that have produced so many new financial instruments, the financial sector has become more efficient in generating profits for itself in the short run. However, as seen in the 2008 global crisis, these new financial assets have made the overall economy, as well as the financial system itself, much more unstable. Moreover, given the liquidity of their assets, the holders of financial assets are too quick to respond to change, which makes it difficult for real-sector companies to secure the ‘patient capital’ that they need for long-term development. The speed gap between the financial sector and the real sector needs to be reduced, which means that the financial market needs to be deliberately made less efficient.” [14]

free-market vs state planning

This myth is best dealt with by Ha-Joon Chang. He explains that there is no such thing as a free market. First, he describes the capitalist free market argument:

“Markets need to be free. When the government interferes to dictate what market participants can or cannot do, resources cannot flow to their most efficient use. If people cannot do the things that they find most profitable, they lose the incentive to invest and innovate. Thus, if the government puts a cap on house rents, landlords lose the incentive to maintain their properties or build new ones. Or, if the government restricts the kinds of financial products that can be sold, two contracting parties that may both have benefited from innovative transactions that fulfil their idiosyncratic needs cannot reap the potential gains of free contract. People must be left ‘free to choose’, as the title of free-market visionary Milton Friedman’s famous book goes.”

His response is:

“The free market doesn’t exist. Every market has some rules and boundaries that restrict freedom of choice. A market looks free only because we so unconditionally accept its underlying restrictions that we fail to see them. How ‘free’ a market is cannot be objectively defined. It is a political definition. The usual claim by free-market economists that they are trying to defend the market from politically motivated interference by the government is false. Government is always involved and those free-marketeers are as politically motivated as anyone. Overcoming the myth that there is such a thing as an objectively defined ‘free market’ is the first step towards understanding capitalism.” [15]

Robert Reich in Saving Capitalism: For The Many, Not The Few explains how the free market idea has poisoned peoples minds so that they think the negative impacts of the free market are simply unfortunate but impersonal outcomes of market forces. When in fact these outcomes benefit governing class and wealthy interests. [16]

Another challenge to the free market myth is that: “in order to secure profits, and to maintain their position of privilege against potential rivals, capitalists (both individuals and institutions) will frequently work to secure monopoly control of particular economic sectors, limiting invention and production within those sectors.” [17]

Capitalists argue against market regulation and claim that governments can’t pick winners. States construct markets, they enforce contracts, provide basic services and support the monetary system that is required for economic activity to take place. Importantly, they do this in a way that favours certain interests over others. [18]

The 2008 and 2020 economic crises have shown how capitalists advocate the free market as the only way to run the economy until a crisis comes along. At that point, they want state support and bailouts. This is known as “socialism for the rich and capitalism for the poor”, “Socialize Costs, Privatize Profits” and ‘lemon socialism‘. This is a good video of Richard Wolff on how American capitalism is just socialism for the rich.

We are told that we are not smart enough to leave things to the market. Ha-Joon Chang summarises this argument:

“We should leave markets alone, because, essentially, market participants know what they are doing – that is, they are rational. Since individuals (and firms as collections of individuals who share the same interests) have their own best interests in mind and since they know their own circumstances best, attempts by outsiders, especially the government, to restrict the freedom of their actions can only produce inferior results. It is presumptuous of any government to prevent market agents from doing things they find profitable or to force them to do things they do not want to do, when it possesses inferior information.”

His response to this myth:

“People do not necessarily know what they are doing, because our ability to comprehend even matters that concern us directly is limited – or, in the jargon, we have ‘bounded rationality’. The world is very complex and our ability to deal with it is severely limited. Therefore, we need to, and usually do, deliberately restrict our freedom of choice in order to reduce the complexity of problems we have to face. Often, government regulation works, especially in complex areas like the modern financial market, not because the government has superior knowledge but because it restricts choices and thus the complexity of the problems at hand, thereby reducing the possibility that things may go wrong.” [19]

Leigh Phillips and Michal Rozworski state that: “perhaps the strongest argument ever mounted against the left by the right is that the calculation and coordination involved in running a complex economy to satisfy disparate human needs and desires simply could not be consciously carried out. Only decentralised price signals operating through the market, miraculously aggregating an infinitude of disparate information, could guide an economy without dramatic failures, misallocations, and ultimately, authoritarian disasters.” They describe how the Second World War saw governments solve complex coordination problems. [20] In their book, People’s Republic of Walmart: How the World’s Biggest Corporations are Laying the Foundation for Socialism, they explain how most Western economies are centrally planned.

Ha-Joon Chang explains that despite the fall of communism, we are still living in planned economies. The capitalist argument goes:

“The limits of economic planning have been resoundingly demonstrated by the fall of communism. In complex modern economies, planning is neither possible nor desirable. Only decentralized decisions through the market mechanism, based on individuals and firms being always on the lookout for a profitable opportunity, are capable of sustaining a complex modern economy. We should do away with the delusion that we can plan anything in this complex and ever- changing world. The less planning there is, the better.”

Ha-Joon Chang response is:

“Capitalist economies are in large part planned. Governments in capitalist economies practise planning too, albeit on a more limited basis than under communist central planning. All of them finance a significant share of investment in R&D and infrastructure. Most of them plan a significant chunk of the economy through the planning of the activities of state-owned enterprises. Many capitalist governments plan the future shape of individual industrial sectors through sectoral industrial policy or even that of the national economy through indicative planning. More importantly, modern capitalist economies are made up of large, hierarchical corporations that plan their activities in great detail, even across national borders. Therefore, the question is not whether you plan or not. It is about planning the right things at the right levels.” [21]

Free market economics has only been applied in non-Western countries

Noam Chomsky explains that pure free-market economics (he calls it Laissez-faire principles) has only been applied to non-Western countries. Attempts by Western governments to try it have gone badly and been reversed.

Corporations need to be regulated

We are told that a strong economy needs corporations to do well. Ha-Joon Chang explains the argument:

“At the heart of the capitalist system is the corporate sector. This is where things are produced, jobs created and new technologies invented. Without a vibrant corporate sector, there is no economic dynamism. What is good for business, therefore, is good for the national economy. Especially given the increasing international competition in a globalizing world, countries that make opening and running businesses difficult or make firms do unwanted things will lose investment and jobs, eventually falling behind. Government needs to give the maximum degree of freedom to business.”

His response:

“Despite the importance of the corporate sector, allowing firms the maximum degree of freedom may not even be good for the firms themselves, let alone the national economy. In fact, not all regulations are bad for business. Sometimes, it is in the long-run interest of the business sector to restrict the freedom of individual firms so that they do not destroy the common pool of resources that all of them need, such as natural resources or the labour force. Regulations can also help businesses by making them do things that may be costly to them individually in the short run but raise their collective productivity in the long run – such as the provision of worker training. In the end, what matters is not the quantity but the quality of business regulation.” [22]

There is also the myth about the need to maximise shareholder value over the performance of the company. This results in managers focusing on increasing the share value instead of business performance. They are of course related but this approach results in managers making decisions that have negative effects on the company performance. [23]

Innovation

The capitalist argument is made by conservative MP Chris (failing) Grayling:

“If you believe in capitalism and free enterprise, then you believe that by allowing people to pursue success for themselves you create a culture of innovation and competition which benefits the whole of society. Free enterprise, business innovating in products and services, benefits the whole of our society.”

Although technological dynamism has been a strong argument for capitalism, investing in research and development it is too risky and takes too long for most capitalists to fund. The majority is publicly funded. [24]

Jeremy Gilbert argues that the creativity that leads to artistic, scientific or utilitarian inventions is not created by capitalism but instead from human interaction on the edges of capital. Then capital feeds on this creativity and transforms it into products to sell. This is why capital must locate itself near great centres of collective exchange and creativity such as London and Paris in the 19th century, New York and California in the 20th century. [25]

the impact of unlimited economic growth on the environment

It’s not possible to have infinite economic growth on a finite planet. [26] Capitalism requires that the economy grows each year. This requires that this year more things need to be made, more energy needs to be used and more people need to be born than last year. Then next year, more of all this is needed than this year.

Myth – capitalist economic theory is the best

Richard Wolff and Stephen Resnick summarise neoclassical theory’s contribution as:

“The originality of neoclassical theory lies in its notion that innate human nature determines economic outcomes. According to this notion, human beings naturally possess the inherent rational and productive abilities to produce the maximum wealth possible in a society. What they need and have historically sought is a kind of optimal social organization—a set of particular social institutions—that will free and enable this inner human essence to realize its potential, namely the greatest possible well-being of the greatest number. Neoclassical economic theory defines each individual’s well-being in terms of his or her consumption of goods and services: maximum consumption equals maximum well-being.

Capitalism is thought to be that optimum society. Its defining institutions (individual freedom, private property, a market system of exchange, etc.) are believed to yield an economy that achieves the maximum, technically feasible output and level of consumption. Capitalist society is also harmonious: its members’ different desires—for maximum enterprise profits and for maximum individual consumption—are brought into equilibrium or balance with one another.” [27]

Economics as a subject is based only on the theories of those who support it. University courses in economics are only taught by those that support capitalism. They do not teach the significant problems with capitalism or the viable alternatives. [28]

Ha-Joon Chang in 23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism explains that good economic policy does not require good economists. That the most successful economic bureaucrats are not normally economists, giving examples of Japan, Korea, China and Taiwan. [29]

The author of Capitalism 4.0: The Birth of a New Economy, Anatole Kaletsky recommends Beyond Mechanical Markets: Asset Price Swings, Risk, and the Role of the State by Roman Frydman and Michael D. Goldberg, which unpacks the economic assumptions mainstream economics is based on. Markets are not predictably rational or irrational. They argue instead that price swings are driven by individuals’ ever-imperfect interpretations of the significance of economic fundamentals for future prices and risk. [30]

Myth – capitalism maintains low taxes, which is good for workers and businesses

The arguement goes that low business taxes encourage companies to stay in a country and provide more jobs by reinvesting the money they would pay in tax into the company. Some also argue that low business tax generates more tax for the government. [31]

Some capitalists would prefer to pay no taxes at all. But the capitalists need the things that taxes pay for: police, schools, healthcare, transport systems. These public goods support capitalist society so there are workers to employ (exploit). [32] They also need the welfare state and public services to ensure capitalism’s survival and people do not become so desperate that they rise up and revolt.

The argument goes that low business tax (corporation tax) result in more business starting up so more jobs. Also, the advocates of low corporation tax state that low tax means businesses will reinvest to make it more competitive, [33] instead of giving shareholders a dividend. For this reinvestment argument to add up then the UK would not have the lowest worker productivity rates in the last 250 years or compared to other countries in Europe. The first article puts the drop in productivity down to: the lasting effect of the 2008 crisis for the financial system; weaker gains from computer technologies in recent years after a boom in the late 1990s and early 2000s; and intense uncertainty over post-Brexit trading relationships sapping business investment. The second article explains the decline is due to: less investment in equipment and infrastructure within the business; less spent on research and development; poor national infrastructure (roads and rail networks); and a lack of trade skills, basic literacy and numeracy skills, and lack of managerial competence.

These companies should be reinvesting in there business with more equipment, infrastructure and training. Add to this that the other issues listed in these articles can be resolved by the government but they choose not to because capitalists do not want highly skilled and well-paid workers, only working four days a week because that would give people time to start thinking and organising for how to make society better. [34] This article argues that reducing the corporate tax rate does not increase worker wages or business reinvestment.

There is also the myth/argument that if you increase taxes then the rich and businesses will relocate abroad. This article shows that the rich do not leave if you increase taxes. Also if businesses are going to relocate this will be to reduce the worker wages costs or where environmental regulations are less strict.

This telegraph article [35] from 2015 explains that corporation tax received by the government was up by 12% compared to 2014, even though the corporation tax percentage had dropped. The article does explain that company profits were up, partly because there was little wage growth. Corporation tax is based on the amount of profits a company takes. So while workers are struggling on low wages, UK company shareholders are taking more profits. It also explains that the UK has a lot more start-up companies that in the past. This is just what capitalists want, loads of small business owners who are more conservative, risk-averse and want the status quo to be maintained. This article does drone on about how unfair it is to say that companies don’t pay their fair share. Most people know that most companies pay their taxes. That complaint is directed at Amazon, Apple and the other tax-dodging big players. This article makes the case that cutting corporation tax costs the government billions.

Ha-Joon Chang challenges the capitalist myth that big government is bad for the economy. He explains that “A well-designed welfare state can actually encourage people to take chances with their jobs and be more, not less, open to changes.” [36]

Myth – capitalism promotes equality, work hard and you’ll get rich

This is the ‘American Dream’ idea that you may start poor but if you work hard, you can be successful and rich. This is also known as meritocracy. [37]

The equality that this refers to is the equality of opportunity. Ha-Joon Chang describes the capitalist argument:

“Many people get upset by inequality. However, there is equality and there is equality. When you reward people the same way regardless of their efforts and achievements, the more talented and the harder-working lose the incentive to perform. This is equality of outcome. It’s a bad idea, as proven by the fall of communism. The equality we seek should be the equality of opportunity. For example, it was not only unjust but also inefficient for a black student in apartheid South Africa not to be able to go to better, ‘white’, universities, even if he was a better student. People should be given equal opportunities. However, it is equally unjust and inefficient to introduce affirmative action and begin to admit students of lower quality simply because they are black or from a deprived background. In trying to equalize outcomes, we not only misallocate talents but also penalize those who have the best talent and make the greatest efforts.”

His response:

“Equality of opportunity is the starting point for a fair society.

But it’s not enough. Of course, individuals should be rewarded for better performance, but the question is whether they are actually competing under the same conditions as their competitors. If a child does not perform well in school because he is hungry and cannot concentrate in class, it cannot be said that the child does not do well because he is inherently less capable. Fair competition can be achieved only when the child is given enough food – at home through family income support and at school through a free school meals programme. Unless there is some equality of outcome (i.e., the incomes of all the parents are above a certain minimum threshold, allowing their children not to go hungry), equal opportunities (i.e., free schooling) are not truly meaningful.” [38]

Economic equality is really what we need to be concerned about. Danny Dorling describes how “The gap between the very rich and the rest is wider in Britain than in any other large country in Europe, and society is the most unequal it has been since shortly after the First World War.” [39]

The benefits for this myth for the capitalists is that it gives workers some hope that things can be better if they work that bit harder to chase the material benefits. It rewards some to keep the dream alive. It is also a cover for the business owners, managers and shareholders to justify their wealthy position. They can say they earned their money through hard work. Of course many inherited their wealth. [40]

There is also the capitalist myth that low worker wages mean lower prices for consumers. This has some truth in it but it is mainly a justification for low worker wages and high business managers wages. By this logic, higher manager wages result in higher consumer prices but there is generally lower investment in production costs (equipment and infrastructure). This results in low worker wages and fewer jobs [41]