Editor’s note: This is an edited transcript of a presentation given at the 2016 Public Interest Environmental Law Conference by DGR’s Dillon Thomson and Jonah Mix on the failure of the contemporary environmental movement to meaningfully stop the destruction of the planet. Using examples from past and current resistance movements, Mix and Thomson chart a more serious, strategic path forward that takes into account the urgency of the ecological crises we face. Part 1 can be found here, and a video of the presentation can be found here.

If you want to make a decisive strike against the industrial system, you need two things: a target and a strategy. Many organizations use the CARVER matrix as the gold standard for target selection. The United States Military has used the CARVER matrix to identify targets in every war since Vietnam. Police agencies use CARVER to target organized crime. Even CEOs use it when they are trying to buy another company. Since the American military, the police, and CEOs are kicking our asses in this struggle, we should look at what’s made them so effective.

CARVER is an acronym. It stands for Criticality, Accessibility, Recuperability, Vulnerability, Effect, and Recognizability. Criticality means, how important is the target? Accessibility: how easy is it to get to the target? Recuperability: how long will it take the system to replace or repair the target? Vulnerability: how easy is it to damage the target? Effect: how will losing the target hurt the system? Recognizability: how easy is the target to identify?

Some of these things tend to group together and others don’t. Plenty of targets may be recognizable, vulnerable, and easily accessible. Those targets aren’t usually critical, though, and they can usually be repaired easily. Examples include a Starbucks windows or a police station. Other targets are critical, almost impossible to repair, and have a massive effect, but they are hard to identify, access, and damage. These include oil refineries and hydroelectric dams.

The purpose of CARVER is to identify which target hits the most categories with the greatest impact. You will never find a target that is critical, accessible, not recuperable, vulnerable, highly effective, and recognizable, but with CARVER, you can figure out which target is most likely to succeed. The matrix is simple: you sit down with a list of targets and assign each one a score from 1 to 10 in every category. You then add up or average the scores. There are arguments about adding versus averaging, but you can do either one. You then look for which target has the highest score.

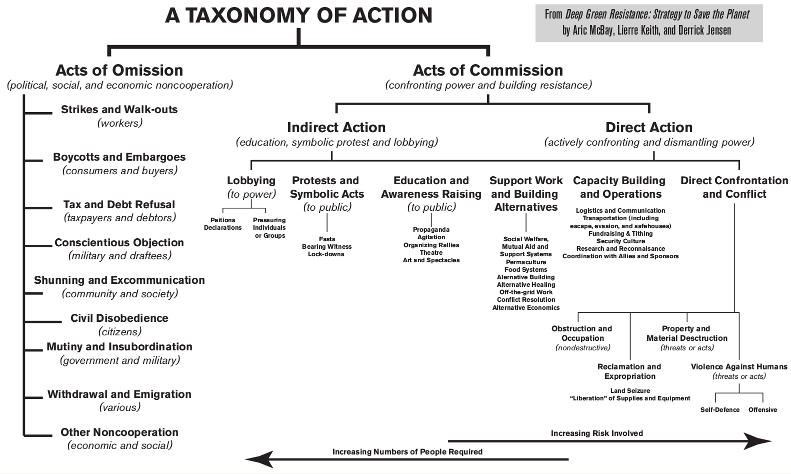

Let’s say you’ve decided on a target using CARVER. Now you need to decide what to do. DGR uses a chart called the Taxonomy of Action. The Taxonomy of Action organizes a variety of strategies and approaches that activists can against any system but especially against industrial civilization. We divided them into two categories: acts of omission (not doing something) and are acts of commission (doing something). Acts of omission are usually low-risk but require a lot of people. These include strikes, boycotts, and protests. Acts of commission require fewer people but come with greater risk.

To be clear, when DGR talks about the need for offensive and underground action, the intent is not to disparage acts of omission. All of it is needed: we need boycotts, strikes, protests, workers’ cooperatives, permaculture groups, songs and plays, and more. Our movement isn’t inherently ineffective; it’s just incomplete. Many other organizations happily focus on the lower-risk acts of omission, and they are valuable. However, there is a lack of discussion about the higher-risk offensive actions. This does not mean that defensive actions aren’t valuable or that the people who do them are somehow lazy or traitorous.

There are four major categories of offensive action:

1) Obstruction and occupation;

2) Reclamation and expropriation;

3) Property and material destruction; and

4) Violence against humans.

Obstruction and occupation mean seizing a node of infrastructure and holding it, which prevents the system from using that node to extract or process resources. Reclamation and expropriation mean seizing resources from the system and putting them to our use. Property and material destruction is exactly what it sounds like: damaging the system so that it cannot be used. Defensive and offensive violence against humans is a last resort.

These four tactics work together. For example, a hypothetical underground could seize a mining outpost and reclaim explosives that are later used for material destruction. A group of aboveground activists could occupy an oil pipeline checkpoint while underground actors take the opportunity to strike at the pipeline down the road. Again, this is all strictly hypothetical. The point is that just as our movement needs both offense and defense, it also needs different kinds of offense done together in strategic pursuit of a larger goal.

This is a lot of information and it is a little abstract. The need for security culture can make it even more difficult to talk about these things as concretely as we would like. We’ve often found that the best method is to look to history to see which struggles have succeeded through the use of these tactics and how. Historical struggles have used these tactics and come out victorious. I’m going to describe two historical movements and one ongoing movement in more detail. All of these movements have utilized a broad range of tactics described in the Taxonomy of Action.

The first example is the African National Congress. The goal of the ANC was equal rights for all South Africans regardless of their ethnicity. It put pressure on the South African apartheid government to implement constitutional reform and return the freedoms denied under the apartheid regime.

From 1912 to 1960, the ANC existed as an aboveground organization. It organized strikes, boycotts, protests, demonstrations, and alternative political education. These actions were all aboveground because the ANC figured it could achieve its goals by making its activities visible to the public and the government. In 1960, though, the government enacted the Pass Laws, which required blacks to carry identification cards. The ANC had protested similar oppression before, but the Pass Laws were much more stringent.

The opposition came to a head in a town called Sharpeville, where police killed 69 protesters and injured 180 more. After the Sharpeville massacre, the ANC was deemed illegal and driven underground. In response, the militant wing of the ANC formed in 1961. It was called the Umkhonto we Sizwe or “Spear of the Nation.”

Umkhonto we Sizwe had the same goal as the ANC but a different strategy. The situation was more desperate and the ANC’s aboveground strategies hadn’t worked. Umkhonto we Sizwe decided to use guerrilla warfare to bring the South African government to the bargaining table. In the early stages, the ANC underground did most of the organization and strategy for Umkhonto we Sizwe, but Umkhonto we Sizwe later broke off and developed its own command structure.

In the early 1960s it began sabotaging government installations, police stations, electric pylons, pass offices, and other symbols of apartheid rule. In the mid-1960s through the mid-70s, Phase 2 focused on political mobilization and developing underground structures. The Revolutionary Council was established in 1969 to train military cadres as part of a long-term plan to build a robust underground network. Most of this training took place in neighboring countries. In Phase 3, from the mid-1970s to 1983, Umkhonto we Sizwe engaged in large-scale guerrilla warfare and armed attacks. It sabotaged railway lines, administrative offices, police stations, oil refineries, fuel depots, the COVRA nuclear plant, military targets, and military personnel.

When it began Phase 4 in 1983, Umkhonto we Sizwe wanted to take the war into the white areas and make it a people’s war. The Revolutionary Council was replaced by the Political Military Council, which controlled and integrated the activities of the now-numerous sections of the organization. It continued attacks on economic, strategic, and military installations in white suburbs.

The ANC and Umkhonto we Sizwe simultaneously rejected the values of the system and attacked the structure, which successfully ended apartheid. ANC’s work to promote mass political struggle combined with Umkhonto we Sizwe’s armed struggle succeeded in pressuring the apartheid government to legitimize the ANC in 1990, and South Africa held its first multiracial elections in April, 1994. Nelson Mandela became South Africa’s first black president.

Despite Nelson Mandela’s fame, his specific actions are largely unacknowledged. He had an integral role in creating Umkhonto we Sizwe. He himself organized sabotage and assassinations. Concerning these actions, Mandela himself said, “I do not deny that I planned sabotage. I did not plan it in a spirit of recklessness, nor because I have any love of violence. I planned it as a result of a calm and sober assessment of the political situation that had arisen after many years of tyranny, exploitation, and oppression of my people by the Whites.”

The next example is the Irish Republican Army. Its goal was the end of British rule to form a free, independent republic. Despite Irish resistance, Great Britain had colonized and oppressed the Irish people for 500 years. The IRA developed a new strategy to make the occupation impossible: guerrilla warfare.

The Irish Republican Army was the underground wing of the aboveground Sinn Féin or Irish Republican Party. The Sinn Féin formed a breakaway government and declared independence from Britain. The British government declared Sinn Féin illegal in 1919, and the need for new strategy led to the creation of the IRA, just as Umkhonto we Sizwe grew out of the ANC in South Africa. Heavy repression led to broad support for the IRA within Ireland.

The IRA operated in “flying columns” of 15 to 30 people who trained in guerrilla warfare, often up in the hills with sticks as substitutes for rifles. Its tactics included hit-and-run raids, ambushes, and assassinations. It blew up police and military bases, destroyed coast guard stations, burnt courthouses and tax collector’s offices, and killed police and military personnel.

The IRA understood that an independent Irish republic was only achievable through confrontation with the British. It chose tactics based on the available resources and training. This was an asymmetrical conflict. The IRA was an underdog against the British military, but its broad base of support provided the necessary food, supplies, safe houses, and medical aid.

Military historians have concluded that the IRA waged a highly successful campaign against the British because the British military determined that the IRA could not be defeated militarily.

The final example of a successful movement that uses the full spectrum described by the Taxonomy of Action is the contemporary Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta or MEND. Since Nigeria’s independence from British colonial rule, multinational oil companies like Chevron and Royal Dutch Shell have enjoyed the support of successive dictators to appropriate oil from the Niger Delta. The people living in the delta have seen their way of life destroyed. Most are fishing people, but the rivers are full of oil. People have been dispossessed in favor of foreign interests and rarely see any revenue from the oil.

Here we see the same pattern that we saw in South Africa and Ireland. Over the past 20 years, the Ogoni people have led a large nonviolent civil disobedience movement in the Niger Delta. Ken Saro-Wiwa was a poet turned activist who protested the collusion between the government and the oil companies. He and eight others were executed in 1995 under what many believe were falsified charges designed to silence his opposition to the oil interests in Nigeria. In his footsteps came people who saw the government’s reaction to nonviolent activism and advocated using force to resist what they saw as the enslavement of their people.

MEND’s goals are the control of oil production/revenue for the Ogoni people and the withdrawal of the Nigerian military from the Niger Delta. It intends to reach them by destroying the capacity of the Nigerian government to export oil from the Niger Delta, which would force the multinational companies to discontinue operations and likely precipitate a national budgetary and economic crisis. Its tactic: sabotage.

MEND sabotages oil infrastructure with very few people and resources. It has resorted to bombings, theft, guerrilla warfare, and kidnapping foreign oil workers for ransom. It is organized into underground cells with a few spokespeople who communicate with international media. Leaders are always on the move and extremely cautious. They do not take telephone calls personally, knowing that soldiers hunting for them have electronic devices capable of pinpointing mobile phone signals. Fighters wear masks to protect their identities during raids, use aliases, and rely on clandestine recruitment.

MEND’s organizational structure has proven effective, and despite its small numbers and hodge-podge networking, it has been quite successful. Between 2006 and 2009, it made a cut of more than 28% in Nigerian oil output. In total, it has reduced oil output in the Niger Delta by 40%. This is an incredible number given its lack of resources.

These are just a few examples of movements that have used a broad spectrum of actions on the Taxonomy of Action chart. They demonstrate that the precedent for full-spectrum resistance has been set many times; many more groups have utilized force because they understand that those in power understand the language of force best. They tried nonviolence, asking nicely, and making concessions, but it doesn’t always work – and when it doesn’t work, this does.

This is a message that MEND sent to the Shell Oil Company: “It must be clear that the Nigerian government cannot protect your workers or assets. Leave our land while you can or die in it.” You have heard about people building bombs, picking up guns, and committing sabotage. These types of resistance are necessary if an environmental movement is to succeed like the IRA, ANC, or MEND succeeded, but this doesn’t mean that the only role in a militant struggle is either blowing something up or staying home and keeping quiet. As Lierre Keith said, “For those of us who can’t be active on the front lines – and this will be most of us – our job is to create a culture that will encourage and promote political resistance. The main tasks will be loyalty and material support.”

During the armed struggle against the British, only about 2% of people involved with the Irish Republican Army ever took up arms. For every MEND soldier, there were hundreds or even thousands of Nigerians who would help them in any way they could. The first role of an aboveground activist is underground promotion.

Underground promotion is anything that creates the conditions for an underground to develop and work effectively. There are, broadly speaking, two types of underground promotion. The first is passive promotion, which describes after-the-fact or roundabout promotion. This is all some people can safely do. You might talk about failures in the modern environmental movement, and even if you don’t suggest a militant solution, frank discussion of our situation may inspire people to look further. You can shift the culture slowly toward resistance values, and if sabotage does occur, you can support it – or if that’s not safe for you, you can at least take the opportunity to criticize the system and not those who struck against it.

If you are in a position to be more vocal, you can explicitly critique traditional environmentalist ideology. This includes critiquing pacifism or a defense-focused movement, arguing in public and among comrades for the necessity of revolutionary violence or strategic militancy, and promoting or encouraging such acts whenever possible. This is especially important after acts of sabotage or militancy do occur.

If you are an aboveground activist who takes on the project of underground promotion, or, hypothetically, an underground activist, you need to have good security culture. Security culture is a set of customs in a community that people adopt to make sure that anyone who performs illegal or sensitive action has their risks minimized and their safety supported. You are practicing security culture when you consider what you say or do in light of its potential effects on the people around you.

Security culture can be broken down into simple “dos and don’ts.” The first “do” is to keep all sensitive information on a strict need-to-know basis. This includes names, plans, past actions, and even loose ideas. Unless there is a tangible material benefit to sharing information and it can be done safely, you need to keep quiet. People bragging to their friends or getting drunk and letting a name slip have undone more radical movements than all the bullets, bombs, and prisons combined. A good way to make sure you follow this rule is to assume that you are always being monitored.

I wrote this assuming that FBI agents or police may read it. I don’t know if they will or not; they very well may not. The decision to take surveillance as a given reminds us not to say anything in public that they shouldn’t hear. That doesn’t mean we should be paranoid or always worry about who is an infiltrator or a plant, because if we are following security culture well, it shouldn’t matter. When you practice security culture well, it doesn’t make you paranoid; it frees you from paranoia.

Security culture boils down to respecting people’s boundaries and learning to establish your own. Feminism is essential to the radical struggle because patriarchy celebrates boundary breaking. Masculinity demands that men don’t respect “no” and blow past anyone who says, “I don’t want to do that” or “I don’t want to talk about that.” True security culture means that we develop the skills to say no and the skills to say nothing at all if we don’t feel safe or think that speaking will be valuable.

There’s a great article called “Misogynists Make Great Informants: How Gender Violence on the Left Enables State Violence in Radical Movements.” It’s about the role that masculine culture and macho posture can play in wrecking our movements. Boundary setting is the end-all and be-all of security culture. The best way to cultivate boundary setting in a community is to adopt a strict and central role for feminism in your movement.

“Don’ts” are even simpler: don’t ask questions that could endanger people involved in direct action. This is the flipside of need-to-know: if you don’t need to know it, don’t ask it. Even if you do need to know it, considering waiting for someone to bring it to you. If they bring it to you in a way that isn’t safe, you also need to say no.

You need to make sure that your underground promotion doesn’t cross the line into incitement. If you tell a crowd of people, “go out and blow up this dam,” or “that bridge,” you’ve crossed the line from promotion to incitement. Incitement has serious legal consequences for you or other people in the movement. You should talk to a lawyer or another experienced activist if you want to know where the line is, as it does vary state by state.

Finally, of course, don’t speak to the police or the FBI. They are not your friends. They can lie to you. If they come to you and say, “We know that someone is doing this and you need to tell us about it,” don’t trust them. You will never lose anything by asking for a lawyer and you will never gain anything by talking to the cops.

We also encourage people to avoid drugs, alcohol, and other non-political illegal activities that might compromise their ability to follow these rules. Good activists who fell into addiction or became otherwise compromised have hurt our movement.

None of us have come to our positions lightly. Most of us in the environmental movement started out as liberals. We bought the right soap, went to the right marches, and some of us even put our bodies on the line in protests and direct actions. Each one of us, for whatever reason, has come to the conclusion that this isn’t enough. We love the planet too much not to consider every option. We respectfully ask that you sit with whatever feelings you have, whether moral uncertainty, anger, or something else, and if you don’t feel in your heart that the next step needs to be taken, we don’t judge or condemn you. We need you. The struggle needs you to do one of the million other jobs that a nonviolent activist can do for this movement.

But we’d ask that you do one thing before you decide: go down to a riverbank, watch the salmon spawn, watch bison roam, look up at the sky, listen to songbirds and crickets, and ask yourself, if these people could talk, what would they ask of me? What would the pine tree cry out over the hum of the chainsaw blades? The starfish mother who is watching her babies cook to death in an acid ocean – if she could speak, what would she ask you to do? These people matter. Their lives matter, every bit as much as our lives matter to you and me. And they need us. They need us to be smart, strong, strategic, and effective.

We welcome everyone, supporters, promoters, and warriors, to move past fifty years of frustration and insufficient action toward a strategic environmental movement that will do what it takes.

I often hear people say, “I can’t handle violence, I can’t stand violence.” And I say, “I can’t stand violence either.” I can’t stand violence against indigenous people, against bison and wolves, against centipedes and snails, and against women. I can’t stand violence against the people whose lives are fodder for this system. We in DGR don’t like violence any more than you do.

If you are a human being in civilization, especially an American or a white man like me, you can’t choose between violence and nonviolence. That question was decided for me long ago; my life is based on violence. Our lives as human beings in civilization are based on violence. The question is whether we will use that violence to keep killing the world or use it to bring about something new. I encourage you to remember that there is violence out there already. It is happening to people who can’t tell us what’s going on. It happens to people whose screams we don’t hear because we aren’t listening. If you read this and say, “I just can’t handle violence,” I say welcome aboard, because we can’t handle it either.

I really enjoyed reading this article! Now I’ll have to find my copy of Deep Green Resistance and re-read it. I’m really annoyed at myself that I didn’t remember a lot of what is written in this article. The CARVER matrix is very handy and I’m glad I know this acronym now.