by DGR News Service | Feb 5, 2022 | ANALYSIS, Reclamation & Expropriation

Editor’s note: This piece details the history of the enclosure movement, focusing on western civilization. Enclosure is an ongoing process by which land that was previously seen as collective, belonging to everyone or purely to nature, is privatized. Enclosure has long been a tenet of capitalism, and more broadly of civilization. Exploitation and destruction of land follows.

by Ian Angus

In 1542, Henry VIII gave his friend and privy councilor Sir William Herbert a gift: the buildings and lands of a dissolved monastery, Wilton Abbey near Salisbury. Herbert didn’t need farmland, so he had the buildings torn down, expelled the monastery’s tenants, and physically destroyed an entire village. In their place he built a large mansion, and fenced off the surrounding lands as a private park for hunting.

In May 1549, officials reported that people who had long used that land as common pasture were tearing down Herbert’s fences.

“There is a great number of the commons up about Salisbury in Wiltshire, and they have plucked down Sir William Herbert’s park that is about his new house, and diverse other parks and commons that be enclosed in that county, but harm they do to [nobody]. They say they will obey the King’s master and my lord Protector with all the counsel, but they say they will not have their commons and their grounds to be enclosed and so taken from them.”

Herbert responded by organizing an armed gang of 200 men, “who by his order attacked the commons and slaughtered them like wolves among sheep.”[1]

The attack on Wilton Abbey was one of many enclosure riots in the late 1540s that culminated in the mass uprising known as Kett’s Rebellion, discussed in Part Two. There had been peasant rebellions in England in the Middle Ages, most notably in 1381, but they were rare. As Engels wrote of the German peasantry, their conditions of life militated against rebellion. “They were scattered over large areas, and this made every agreement between them extremely difficult; the old habit of submission inherited by generation from generation, lack of practice In the use of arms in many regions, and the varying degree of exploitation depending on the personality of the lord, all combined to keep the peasant quiet.”[2]

Enclosure, a direct assault on the peasants’ centuries-old way of life, upset the old habit of submission. Protests against enclosure were reported as early as 1480, and became frequent after 1530. “Hundreds of riots protesting enclosures of commons and wastes, drainage of fens and disafforestation … reverberated across the century or so between 1530 and 1640.”[3]

Elizabethan authorities used the word “riot” for any public protest, and the label is often misleading. Most were actually disciplined community actions to prevent or reverse enclosure, often by pulling down fences or uprooting the hawthorn hedges that landlords planted to separate enclosed land.

“The point in breaking hedges was to allow cattle to graze on the land, but by filling in the ditches and digging up roots those involved in enclosure protest made it difficult and costly for enclosers to re-enclose quickly. That hedges were not only dug up but also burnt and buried draws attention to both the considerable time and effort which was invested in hedge-breaking and to the symbolic or ritualistic aspects of enclosure opposition. … Other forms of direct action against enclosure included impounding or rescuing livestock, the continued gathering of previously common resources such as firewood, trespassing in parks and warrens, and even ploughing up land which had been converted to pasture or warrens.”[4]

The forms of anti-enclosure action varied, from midnight raids to public confrontations “with the participants, often including a high proportion of women, marching to drums, singing, parading or burning effigies of their enemies, and celebrating with cakes and ale.”[5] (I’m reminded of Lenin’s description of revolutions as festivals of the oppressed and exploited.) Villagers were very aware of their rights — it was joked that some farmers read Thomas de Lyttleton’s Treatise on Tenures while ploughing — so physical assaults on fences and hedges were often accompanied by petitions and legal action.

Many accounts of what’s called the enclosure movement focus on the consolidation of dispersed strips of leased land into compact farms, but most enclosure riots actually targeted the privatization of the unallocated land that provided pasture, wood, peat, game and more. For cottagers who had no more than a small house and an acre or two of poor quality land, access to those resources was a matter of life and death. “Commons and common rights, so far from being merely a luxury or a convenience, were really an integral and indispensable part of the system of agriculture, a lynch pin, the removal of which brought the whole structure of village society tumbling down.”[6]

Coal wars

In the last decades of the 1500s, farmers in northern England faced a new threat to their livelihoods, the rapid expansion of coal mining, which many landlords found was more profitable than renting farmland. Thousands who were made landless by enclosure ultimately found work in the new mines, but the very creation of those mines required the dispossession of farmers and farmworkers. The search for coal seams left pits and waste that endangered livestock; actual mines destroyed pasture and arable land and polluted streams, making farming impossible.

The prospect of mining profits produced a new kind of enclosure — expropriation of mineral rights under common land. “Wherever coal-mining became important, it stimulated the movement towards curtailing the rights of customary tenants and even of small freeholders, and towards the enclosure of portions of the wastes.” In the landlords’ view, it wasn’t enough just to fence off the mining area, “not only must the tenants be prevented from digging themselves, they must be stripped of their power to refuse access to minerals under their holdings, or to demand excessive compensation.”[7]

As a result, historian John Nef writes, tenant farmers “lived in constant fear of the discovery of coal under their land,” and attempts to establish new mines were often met by sabotage and violence. “Many were the obscure battles fought with pitchfork against pick and shovel to prevent what all tenants united in branding as a mighty abuse.” Fences were torn down, pits filled in, buildings burned, and coal was carried off. In Lancashire, the enclosures surrounding one large mine were torn down sixteen times by freeholders who claimed “freedom of pasture.” In Derbyshire in 1606, a landlord complained that twenty-three men “armed with pitchforks, bows and arrows, guns and other weapons,” had threatened to kill everyone involved if mining continued on the manor.[8]

In these and many other battles, commoners heroically fought to preserve their land and rights, but they were unable to stop the growth of a highly-profitable industry that was supported physically by the state and legally by the courts. As elsewhere, capital defeated the commons.

Turning point

In the early 1500s, capitalist agriculture was new, and the landowning classes were generally critical of the minority who enclosed common land and evicted tenants. The commonwealth men whose sermons defended traditional village society and condemned enclosure were expressing, in somewhat exaggerated form, views that were widely held in the aristocracy and gentry. While anti-enclosure laws were drafted and introduced by the royal government, they were invariably approved by the House of Commons, which “almost by definition, represented the prospering section of the gentry.”[9]

As the century progressed, however, growing numbers of landowners sought to break free from customary and state restrictions in order to “improve” their holdings. In 1601, when Sir Walter Raleigh argued that the government should “let every man use his ground to that which it is most fit for, and therein use his own discretion,”[10] a large minority in the House of Commons agreed.

As Christopher Hill writes, “we can trace the triumph of capitalism in agriculture by following the Commons’ attitude towards enclosure.”

“The famine year 1597 saw the last acts against depopulation; 1608 the first (limited) pro-enclosure act. … In 1621, in the depths of the depression, came the first general enclosure bill — opposed by some M.P.s who feared agrarian disturbances. In 1624 the statutes against enclosure were repealed. … the Long Parliament was a turning point. No government after 1640 seriously tried either to prevent enclosures, or even to make money by fining enclosers.”[11]

The early Stuart kings — James I (1603-1625) and Charles I (1625-1649) — played a contradictory role, reflecting their position as feudal monarchs in an increasingly capitalist country. They revived feudal taxes and prosecuted enclosing landlords in the name of preventing depopulation, but at the same time they raised their tenants’ rents and initiated large enclosure projects that dispossessed thousands of commoners.

Enclosure accelerated in the first half of the 1600s — to cite just three examples, 40% of Leicestershire manors, 18% of Durham’s land area, and 90% of the Welsh lowlands were enclosed in those decades.[12] Even without formal enclosure, many small farmers lost their farms because they couldn’t pay fast rising rents. “Rent rolls on estate after estate doubled, trebled, and quadrupled in a matter of decades,” contributing to “a massive redistribution of income in favour of the landed class.”

It was a golden age for landowners, but for small farmers and cottagers, “the third, fourth, and fifth decades of the seventeenth century witnessed extreme hardship in England, and were probably among the most terrible years through which the country has ever passed.[13]

Fighting back

Increased enclosure was met by increased resistance. Seventeenth century enclosure riots were generally larger, more frequent, and more organized than in previous years. Most were local and lasted only a few days, but several were large enough to be considered regional uprisings — “the result of social and economic grievances of such intensity that they took expression in violent outbreaks of what can only be called class hatred for the wealthy.”[14]

The Midland Revolt broke out in April 1607 and continued into June. The rebels described themselves as “diggers” and “levelers,” labels later used by radicals during the civil war, and they claimed to be led by “Captain Pouch,” a probably mythical figure whose magical powers would protect them.[15] Martin Empson describes the revolt in his history of rural class struggle, Kill all the Gentlemen:

“Events in 1607 involved thousands of peasants beginning in Northamptonshire at the very start of May and spreading to Warwickshire and Leicestershire. Mass protests took place, involving 3,000 at Hilmorton in Warwickshire and 5,000 at Cotesback in Leicestershire. In a declaration produced during the revolt, The Diggers of Warwickshire to all other Diggers, the authors write that they would prefer to ‘manfully die, then hereafter to be pined to death for want of that which those devouring, encroachers do serve their fat hogs and sheep withal.’”[16]

These were well-planned actions, not spontaneous riots. Cottagers from multiple villages met in advance to discuss where and when to assemble, arranged transportation, and provided tools, meals and places to sleep for the rebels who would spend days tearing down fences, uprooting hedges and filling in ditches. Local militias could not stop them — indeed, “many members of the militia themselves became involved in the rising, either actively or by voting with their feet and failing to attend the muster.”[17]

The movement was only stopped when mounted vigilantes, hired by local landlords, attacked protestors near the town of Newton, massacring more than 50 and injuring many more. The supposed leaders of the rising were publicly hanged and quartered, and their bodies were displayed in towns throughout the region.

The Western Rising was less organized, but it lasted much longer, from 1626 to 1632. Here the focus was “disafforestation” — Charles I’s privatization of the extensive royal forests in which thousands of farmers and cottagers had long exercised common rights. The government appointed commissions to survey the land, propose how to divide it up, and negotiate compensation for tenants. The largest portions were leased to investors, mainly the king’s friends and supporters, who in turn rented enclosed parcels to large farmers.”[18]

Generally speaking, the forest enclosures seem to have been fair to freeholders and copyholders who could prove that they had common rights, but not to those who had never had formal leases, or couldn’t prove that they had. The formally landless were excluded from the negotiations and from the land they had worked on all their lives.

For at least six years, landless workers and cottagers fought to prevent or reverse enclosures in Dorset, Wiltshire, Gloucestershire, and other areas where the crown was selling off public forests.

“The response of the inhabitants of each forest was to riot almost as soon as the post-disafforestation enclosure had begun. These riots were broadly similar in aim and character, directed toward the restoration of the open forest and involving destruction of the enclosing hedges, ditches, and fences and, in a few cases, pulling down houses inhabited by the agents of the enclosers, and assaults on their workmen.”[19]

Declaring “here were we born and here we will die,” as many as 3,000 men and women took part in each action against forest enclosures. Buchanan Sharp’s study of court records shows that the majority of those arrested for anti-enclosure rioting identified themselves not as husbandmen (farmers) but as artisans, particularly weavers and other clothworkers, who depended on the commons to supplement their wages. “It could be argued that there were two types of forest inhabitants, those with land who went to law to protect their rights, and those with little or no land who rioted to protect their interests.”[20]

The longest continuing fight against enclosure took place in eastern England, in the fens. From the 1620s to the end to the century, thousands of farmers and cottagers resisted large-scale projects to drain and enclose the vast wetlands that covered over 1400 square miles in Lincolnshire and adjacent counties. Aiming to create “new land” that could be sold to investors and rented to large tenant farmers, the drainage projects would dispossess thousands of peasants whose lives depended on the region’s rich natural resources.

The result was almost constant conflict. Historian James Boyce describes what happened in 1632, when constables tried to arrest opponents of draining a 10,000 acre common marsh, in the Cambridgeshire village of Soham:

“The constables charged with arresting the four Soham resistance leaders so delayed entering the village that they were later charged for not putting the warrant into effect. When they finally sought to do so, an estimated 200 people poured onto the streets armed with forks, staves and stones. The next day a justice ordered 60 men to support the constables in executing the warrant but over 100 townspeople still stood defiant, warning ‘that if any laid hands of any of them, they would kill or be killed’. When one of the four was finally arrested, the constables were attacked and several people were injured. A justice arrived in Soham on 11 June with about 120 men and made a further arrest before the justice’s men were again ‘beaten off, the rest never offering to aid them’. Another of the four leaders, Anne Dobbs, was eventually caught and imprisoned in Cambridge Castle but on 14 June 1633, the fight was resumed when about 70 people filled in six division ditches meant to form part of an enclosure. Twenty offenders were identified, of whom fourteen were women.”[21]

Militant and often violent protests challenged every drainage project. As elsewhere in England, fenland rioters uprooted hedges, filled ditches and destroyed fences, but here they also destroyed pumping equipment, broke open dykes, and attacked drainage workers, many of whom had been brought from the Netherlands. “By the time of the civil war the whole fenland was in a state of open rebellion.”[22]

Revolution in the revolution

For eleven years, from 1629 to 1640, Charles I tried to rule as an absolute monarch, refusing to call Parliament and unilaterally imposing taxes that were widely viewed as oppressive and illegal. When his need for more money finally forced him to call Parliament, the House of Commons refused to approve new taxes unless he agreed to restrictions on his powers. The king refused and civil war broke out in 1642, leading to Charles’s defeat and execution in 1649. From then until 1660, England was a republic.

Many histories of the civil was treat it as purely a conflict within the ruling elite: it often seems, Brian Manning writes, “as if the other 97 per cent of the population did not exist or did not matter.”[23] In fact, as Manning shows in The English People and the English Revolution, poor peasants, wage laborers and small producers were not just followers and foot soldiers — they were conscious participants whose actions influenced and often determined the course of events. The fight for the commons was an important part of the English Revolution.

“Between the assembling of the Long Parliament in·1640 and the outbreak of the civil war in 1642 there was a rising tide of protest and riot in the countryside. This was directed chiefly against the enclosures of commons, wastes and fens, and the invasions of common rights by the king, members of the royal family, courtiers, bishops and great aristocrats.”[24]

Between 1640 and 1644 there were anti-enclosure riots in more than half of England’s counties, especially in the midlands and north: “in some cases not only the fences but the houses of the gentry were attacked.”[25]

The wealthiest landowners were outraged. In July 1641, the House of Lords complained that “violent breaking into Possessions and Inclosures, in riotous and tumultuous Manner, in several Parts of this Kingdom,” was happening “more frequently … since this Parliament began than formerly.” They ordered local authorities to ensure “that no Inclosure or Possession shall be violently, and in a tumultuous Manner, disturbed or taken away from any Man,”[26] but their orders had little effect. “Constables not only repeatedly failed to perform their duties against neighbours engaged in the forcible recovery of their commons, but were also sometimes to be found in the ranks of the rioters themselves.”[27]

The rioters hated the landowners’ government and weren’t reluctant to say so. When an order against anti-enclosure riots was read in a church in Wiltshire in April 1643, for example, one parishioner stood and “most contemptuously and in dishonor of the Parliament and their authority said that he cared not for their orders and the Parliament might have kept them and wiped their arses with them.”[28]

In 1645, anti-enclosure protestors in Epworth, Lincolnshire, replied to a similar order that ‘”They did not care a Fart for the Order which was made by the Lords in Parliament and published in the Churches, and, that notwithstanding that Order, they would pull down all the rest of the Houses in the Level that were built upon those Improvements which were drained, and destroy all the Enclosures.”[29]

The most intense conflicts took place in the fens. To cite just one case, in February 1643, in Axholme, Lincolnshire, commoners armed with muskets opened floodgates at high tide, drowning over six thousand acres of recently drained and enclosed land, and then closed the gates to prevent the water from flowing out at low tide. Armed guards then held the position for ten weeks, threatening to shoot anyone who attempted to let the water out.[30]

Many more examples could be cited. The years 1640 to 1660 weren’t just a time of revolutionary civil war, they were decades of anti-enclosure rebellion.

Defeat

Two centuries later, in The Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels wrote that “all previous historical movements were movements of minorities, or in the interests of minorities.” That was certainly true of the English Revolution — Parliament could not have overthrown the monarchy without the support of small producers, peasants and wage-workers, but the plebeians got little from the victory. As Digger leader Gerard Winstanley wrote to the “powers of England” in 1649: “though thou hast promised to make this people a free people, yet thou hast so handled the matter, through thy self-seeking humour, that thou has wrapped us up more in bondage, and oppression lies heavier upon us.”[31]

Since the king was one of the largest and most hated enclosers, many anti-enclosure protesters expected Parliament to support their cause, but their hopes were disappointed — no surprise, since almost all MPs were substantial landowners. Both houses of Parliament repeatedly condemned anti-enclosure riots, and no anti-enclosure measures were adopted during the civil war or by the republican regime in the 1650s. The last attempt to regulate (not prevent) enclosure occurred in 1656, when a Bill to do that was rejected on first reading: the Speaker said “he never liked any Bill that touched upon property,” and another MP called it “the most mischievous Bill that ever was offered to this House.”[32]

Like the royal government it replaced, the republican government in the 1650s raised revenue by selling off royal forests and supported the drainage and enclosure of the fens. It passed laws that eliminated all remaining feudal restrictions and charges on landowners, but made no changes to the tenures of farmers and cottagers. “Thus landlords secured their own estates in absolute ownership, and ensured that copyholders remained evictable.”[33]

In Christopher Hill’s words, in the seventeenth century struggle for land, “the common people were defeated no less decisively than the crown.”[34]

The last wave

There were sporadic anti-enclosure protests in the last years of the seventeenth century, especially in the fens, but for all practical purposes, the uprisings of 1640 to 1660 were the last of their kind. In the early 1700s, peasant resistance mostly involved illegally hunting deer or gathering wood on enclosed land, not tearing down fences. Long memories of brutal defeats, reinforced by fear of ruling class forces that were now even stronger, discouraged any return to mass action.

Until the mid-1700s, the large landlords who owned most of English farmland seem to have been more interested in reaping the rewards of previous victories than in enclosing the remaining open fields and commons. About a quarter of the country’s farmland was still worked in open fields in 1700, but so long as rents covered costs, with a substantial surplus, few landlords chose to make changes.

When a new wave of enclosures began about 1755, spurred first by falling grain prices and then by rising prices during Napoleonic wars, the social and economic context was very different. English capitalist society, we might say, had become more “civilized.” In place of the rough methods of earlier years, enclosure became a structured bureaucratic process, subject to political oversight and regulation. Enclosure required detailed surveys and plans prepared by lawyers and professional enclosure commissioners, all accepted by the owners and tenants of three-quarters of the land involved (which was often a small minority of the people affected), then written into a Bill which had to be approved by a Parliamentary committee and both houses of Parliament.

Marx referred to the resulting Enclosure Acts as “decrees by which the landowners grant themselves the peoples’ land as private property, decrees of expropriation of the people.”[35]

Most Parliamentary enclosures seem to have carefully followed the law, including fairly allocating land or compensation to leaseholders large and small, but the law did not recognize customary common rights. Just as with the cruder methods of previous centuries, Parliamentary enclosure didn’t just consolidate land: it eliminated common rights and dispossessed the landless commoners who depended on them. When a 20th century historian called this “perfectly proper,” because the law was obeyed and property rights protected, Edward Thompson replied:

“Enclosure (when all the sophistications are allowed for) was a plain enough case of class robbery, played according to fair rules of property and law laid down by a parliament of property-owners and lawyers. …

“What was ‘perfectly proper’ in terms of capitalist property-relations involved, none the less, a rupture of the traditional integument of village custom and of right: and the social violence of enclosure consisted precisely in the drastic, total imposition upon the village of capitalist property-definitions.”[36]

There were some local riots after enclosure was approved, often in the form of stealing or burning fence posts and rails, but as J.M. Neeson has shown, most resistance took the form of “stubborn non-compliance, foot-dragging and mischief,” before an enclosure Bill went to London. Villagers refused to speak to surveyors or gave them inaccurate information, sent threatening letters, stole record books and field plans, and in general tried to force delays or drive up the landlords’ costs. In some cases, villagers petitioned Parliament to reject the proposed bill, but that was expensive and rarely successful.[37]

Ultimately, however, the game was rigged. Sabotage might slow things down or win better terms, but landlords and large tenants who wanted to impose enclosure could always do so, and there was no right of appeal. Between 1750 and 1820 nearly 4,000 Enclosure Acts were passed, affecting roughly 6.8 million acres. Only a handful of open-field villages remained. Despite centuries of resistance, the power of capital prevailed: “the commons in England were gradually driven out of existence, the small farms engrossed, the land enclosed, and the commoners forcibly removed.”[38]

Continuing enclosure

As Marx wrote, “the expropriation of the mass of the people from the soil forms the basis of the capitalist mode of production.” People who can produce all or most of their own subsistence are independent in ways that are alien to capitalism — they are under no economic compulsion to work for wages. As an advocate of enclosure wrote in 1800, “when a labourer becomes possessed of more land than he and his family can cultivate in the evenings … the farmer can no longer depend on him for constant work.”[39]

This series of articles has focused on England, where the expropriation involved a centuries-long war against the commons. It was the classic case of primitive accumulation, the “two transformations” by which “the social means of subsistence and production are turned into capital, and the immediate producers are turned into wage-laborers,”[40] but of course this is not the whole story. In other places, capitalism’s growth by dispossession occurred at different speeds and in different ways.

In Scotland, for example, enclosure didn’t begin until the mid-1700s, but then the drive to catch up with England ensured that it was much faster and particularly brutal. As Neil Davidson writes, the horrendous 19th century Highland Clearances that Marx so eloquently condemned in Capital involved not primitive accumulation by new capitalists, but the consolidation of “an existing, and thoroughly rapacious, capitalist landowning class … whose disregard for human life (and, indeed, ‘development’) marked it as having long passed the stage of contributing to social progress.”[41]

And, of course, the growth of the British Empire, from Ireland to the Americas to India and Africa, was predicated on enclosure of colonized land and dispossession of indigenous peoples. As Rosa Luxemburg wrote, extending the “blight of capitalist civilization” required

“the systematic destruction and annihilation of all the non-capitalist social units which obstruct its development .… Each new colonial expansion is accompanied, as a matter of course, by a relentless battle of capital against the social and economic ties of the natives, who are also forcibly robbed of their means of production and labour power.”[42]

That remains true today, when one percent of the world’s population has 45% of all personal wealth and nearly three billion people own nothing at all. Every year, the rich enclose ever more of the world’s riches, and their corporations destroy more of the life support systems that should be our common heritage. Enclosures continue, strengthening an ever-richer ruling class and an ever-larger global working class.

In the seventeenth century, an unknown poet summarized the hypocrisy and brutality of enclosure in four brief lines:

The law locks up the man or woman

Who steals the goose from off the common

But leaves the greater villain loose

Who steals the common from the goose.

We should also recall the fourth verse of that poem, which urges us to move from indignation to action.

The law locks up the man or woman

Who steals the goose from off the common

And geese will still a common lack

Till they go and steal it back.

Editor’s note: The Commoner’s Catalog for Changemaking

This article originally appeared in Climate & Capitalism.

Articles in this series:

Commons and classes before capitalism

‘Systematic theft of communal property’

Against Enclosure: The Commonwealth Men

Dispossessed: Origins of the Working Class

Against Enclosure: The Commoners Fight Back

Notes

[1] Quotations in Andy Wood, The 1549 Rebellions and the Making of Early Modern England (Cambridge University Press, 2007), 49.

[2] Frederick Engels, “The Peasant War in Germany” (1850) in Marx-Engels Collected Works, vol. 10 (International Publishers, 1978), 410.

[3] Roger B. Manning, Village Revolts: Social Protest and Popular Disturbances in England, 1509-1640 (Clarendon Press, 1988), 3.

[4] Briony Mcdonagh and Stephen Daniels, “Enclosure Stories: Narratives from Northamptonshire,” Cultural Geographies 19, no. 1 (January 2012), 113.

[5] Norah Carlin, The Causes of the English Civil War (Blackwell, 1999), 129.

[6] R. H. Tawney, The Agrarian Problem in the Sixteenth Century (Lector House, 2021 [1912]), 76.

[7] John U. Nef, The Rise of the British Coal Industry, vol. 1 (Frank Cass, 1966), 342-3, 310.

[8] John U. Nef, The Rise of the British Coal Industry, vol. 1 (Frank Cass, 1966), 312, 316-7, 291-2. See also Andreas Malm, Fossil Capital: The Rise of Steam Power and the Roots of Global Warming (London: Verso, 2016), 320-24.

[9] Christopher Hill, Reformation to Industrial Revolution (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1968), 51.

[10] Proceedings in the Commons, 1601: November 2–5.

[11] Hill, Reformation to Industrial Revolution, 51.

[12] Keith Wrightson, Earthly Necessities: Economic Lives in Early Modern Britain (Yale University Press, 2000), 162.

[13] Peter Bowden, “Agricultural Prices, Farm Profits, and Rents,” in The Agrarian History of England and Wales, ed. Joan Thirsk, vol. IV (Cambridge University Press, 1967), 695, 690, 621.

[14] Buchanan Sharp, In Contempt of All Authority: Rural Artisans and Riot in the West of England, 1586-1660 (University of California, 1980), 264.

[15] Such figures appeared frequently in rural uprisings in England: later examples included Lady Skimmington, Ned Ludd and Captain Swing.

[16] Martin Empson, ‘Kill All the Gentlemen’: Class Struggle and Change in the English Countryside (Bookmarks, 2018), 165.

[17] John E. Martin, Feudalism to Capitalism: Peasant and Landlord in English Agrarian Development (Macmillan, 1986), 173.

[18] Sharp, In Contempt of All Authority, 84-5.

[19] Sharp, In Contempt of All Authority, 86.

[20] Sharp, In Contempt of All Authority, 144.

[21] James Boyce, Imperial Mud: The Fight for the Fens (Icon Books, 2021), Kindle edition, loc. 840.

[22] Brian Manning, The English People and the English Revolution (Bookmarks, 1991), 194.

[23] Brian Manning, Aristocrats, Plebeians and Revolution in England 1640-1660 (Pluto Press, 1996), 1.

[24] Manning, English People, 195.

[25] John S. Morrill, The Revolt of the Provinces: Conservatives And Radicals In The English Civil War, 1630 1650 (Longman, 1987) 34.

[26] “General Order for Possessions, to secure them from Riots and Tumults,” House of Lords Journal vol. 4, July 13, 1641.

[27] Lindley, Fenland Riots, 68.

[28] Sharp, In Contempt of All Authority, 228.

[29] Quoted in Lindley, Fenland Riots, 149.

[30] Lindley, Fenland Riots, 147.

[31] Gerard Winstanley, The Law of Freedom, and Other Writings, ed. Christopher Hill (Penguin Books, 1973), 82.

[32] Christopher Hill and Edmund Dell, eds., The Good Old Cause, 2nd ed. (Routledge, 2012), 424.

[33] Christopher Hill, Puritanism and Revolution: Studies in Interpretation of the English Revolution of the 17th Century (Schocken Books, 1964), 191.

[34] Christopher Hill, God’s Englishman: Oliver Cromwell and the English Revolution (Harper, 1972), 260.

[35] Marx, Capital Volume, 1, 885.

[36] E. P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class (Penguin Books, 1991), 237-8.

[37] The best account of resistance to enclosure in the 18th century is chapter 9 of J. M. Neeson, Commoners: Common Right, Enclosure and Social Change in England, 1700-1820 (Cambridge University Press, 1993).

[38] John Bellamy Foster, Brett Clark, and Hannah Holleman, “Marx and the Commons,” Social Research (Spring 2021), 5.

[39] Commercial and Agricultural Magazine, October 1800, quoted in E. P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class (Penguin Books, 1991), 243.

[40] Karl Marx, Capital Volume, 1, 874.

[41] Neil Davidson, “The Scottish Path to Capitalist Agriculture 1,” Journal of Agrarian Change (July 2004), 229.

[42] Rosa Luxemburg, The Accumulation of Capital, (Routledge, 2003), 352, 350.

by DGR News Service | Sep 19, 2021 | Agriculture, Repression at Home, Strategy & Analysis

This article originally appeared in Climate & Capitalism. It is part 2 of a series, read part 1 here.

Featured image: Tenants harvest the landlord’s grain

“The expropriation of the mass of the people from the soil forms the basis of the capitalist mode of production.” (Karl Marx)

by Ian Angus

“The ground of the parish is gotten up into a few men’s hands, yea sometimes into the tenure of one or two or three, whereby the rest are compelled either to be hired servants unto the other or else to beg their bread in misery from door to door.” (William Harrison, 1577)[1]

In 1549, tens of thousands of English peasants fought — and thousands died — to halt and reverse the spread of capitalist farming that was destroying their way of life. The largest action, known as Kett’s Rebellion, has been called “the greatest practical utopian project of Tudor England and the greatest anticapitalist rising in English history.”[2]

On July 6, peasants from Wymondham, a market town in Norfolk, set out across country to tear down hedges and fences that divided formerly common land into private farms and pastures. By the time they reached Norwich, the second-largest city in England, they had been joined by farmers, farmworkers and artisans from many other towns and villages. On July 12, as many as 16,000 rebels set up camp on Mousehold Heath, near the city. They established a governing council with representatives from each community, requisitioned food and other supplies from nearby landowners, and drew up a list of demands addressed to the king.

Over the next six weeks, they twice invaded and captured Norwich, repeatedly rejected Royal pardons on the grounds that they had done nothing wrong, and defeated a force of 1,500 men sent from London to suppress them. They held out until late August, when they were attacked by some 4,000 professional soldiers, mostly German and Italian mercenaries, who were ordered by the Duke of Warwick to “take the company of rebels which they saw, not for men, but for brute beasts imbued with all cruelty.”[3] Over 3,500 rebels were massacred, and their leaders were tortured and beheaded.

The Norwich uprising is the best documented and lasted longest, but what contemporaries called the Rebellions of Commonwealth involved camps, petitions and mass assemblies in at least 25 counties, showing “unmistakable signs of coordination and planning right across lowland England.”[4] The best surviving statement of their objectives is the 29 articles adopted at Mousehold Heath. They were listed in no particular order, but, as historian Andy Wood writes, “a strong logic underlay them.”

“The demands drawn up at the Mousehold camp articulated a desire to limit the power of the gentry, exclude them from the world of the village, constrain rapid economic change, prevent the over-exploitation of communal resources, and remodel the values of the clergy. … Lords were to be excluded from common land and prevented from dealing in land. The Crown was asked to take over some of the powers exercised by lords, and to act as a neutral arbiter between lord and commoner. Rents were to be fixed at their 1485 level. In the most evocative phrase of the Norfolk complaints, the rebels required that the servile bondmen who still performed humiliating services upon the estates of the Duchy of Lancaster and the former estates of the Duke of Norfolk be freed: ‘We pray that all bonde men may be made Free, for god made all Free with his precious blode sheddyng’.”[5]

The scope and power of the rebellions of 1549 demonstrate, as nothing else can, the devastating impact of capitalism on the lives of the people who worked the land in early modern England. The radical changes known to history by the innocuous label enclosure peaked in two long waves: during the rise of agrarian capitalism in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and during the consolidation of agrarian capitalism in the eighteenth and nineteenth.

This article discusses the sixteenth century origins of what Marx called “the systematic theft of communal property.”[6]

Sheep devour people

In part one we saw that organized resistance and reduced population allowed English peasants to win lower rents and greater freedom in the 1400s. But they didn’t win every fight — rather than cutting rents and easing conditions to attract tenants, some landlords forcibly evicted their smaller tenants and leased larger farms, at increased rents, to well-off farmers or commercial sheep graziers. Caring for sheep required far less labor than growing grain, and the growing Flemish cloth industry was eager to buy English wool.

Local populations declined as a result, and many villages disappeared entirely. As Sir Thomas More famously wrote in 1516, sheep had “become so greedy and fierce that they devour human beings themselves. They devastate and depopulate fields, houses and towns.”[7]

For more than a century, enclosure and depopulation — the words were almost always used together — were major social and political concerns for England’s rulers. As early as 1483, Edward V’s Lord Chancellor, John Russell, criticized “enclosures and emparking … [for] driving away of tenants and letting down of tenantries.”[8] In the same decade, the priest and historian John Rous condemned enclosure and depopulation, and identified 62 villages and hamlets within 12 miles of his home in Warwickshire that were “either destroyed or shrunken,” because “lovers or inducers of avarice” had “ignominiously and violently driven out the inhabitants.” He called for “justice under heavy penalties” against the landlords responsible.[9]

Thirty years later, Henry VIII’s advisor Sir Thomas More condemned the same activity, in more detail.

“The tenants are ejected; and some are stripped of their belongings by trickery or brute force, or, wearied by constant harassment, are driven to sell them. One way or another, these wretched people — men, women, husbands, wives, orphans, widows, parents with little children and entire families (poor but numerous, since farming requires many hands) — are forced to move out. They leave the only homes familiar to them, and can find no place to go. Since they must have at once without waiting for a proper buyer, they sell for a pittance all their household goods, which would not bring much in any case. When that little money is gone (and it’s soon spent in wandering from place to place), what finally remains for them but to steal, and so be hanged — justly, no doubt — or to wander and beg? And yet if they go tramping, they are jailed as idle vagrants. They would be glad to work, but they can find no one who will hire them. There is no need for farm labor, in which they have been trained, when there is no land left to be planted. One herdsman or shepherd can look after a flock of beasts large enough to stock an area at used to require many hands to make it grow crops.”[10]

Many accounts of the destruction of commons-based agriculture assume that that enclosure simply meant the consolidation of open-field strips into compact farms, and planting hedges or building fences to demark the now-private property. In fact, as the great social historian R.H. Tawney pointed out in his classic study of The Agrarian Problem in the Sixteenth Century, in medieval and early modern England the word enclosure “covered many different kinds of action and has a somewhat delusive appearance of simplicity.”[11] Enclosure might refer to farmers trading strips of manor land to create more compact farms, or to a landlord unilaterally adding common land to his demesne, or to the violent expulsion of an entire village from land their families had worked for centuries.

Even in the middle ages, tenant farmers had traded or combined strips of land for local or personal reasons. That was called enclosure, but the spatial rearrangement of property as such didn’t affect common rights or alter the local economy.[12] In the sixteenth century, opponents of enclosure were careful to exempt such activity from criticism. For example, the commissioners appointed to investigate illegal enclosure in 1549 received this instruction:

“You shall enquire what towns, villages, and hamlets have been decayed and laid down by enclosures into pastures, within the shire contained in your instructions …

“But first, to declare unto you what is meant by the word enclosure. It is not taken where a man encloses and hedges his own proper ground, where no man has commons, for such enclosure is very beneficial to the commonwealth; it is a cause of great increase of wood: but it is meant thereby, when any man has taken away and enclosed any other men’s commons, or has pulled down houses of husbandry, and converted the lands from tillage to pasture. This is the meaning of this word, and so we pray you to remember it.”[13]

As R.H. Tawney wrote, “What damaged the smaller tenants, and produced the popular revolts against enclosure, was not merely enclosing, but enclosing accompanied by either eviction and conversion to pasture, or by the monopolizing of common rights. … It is over the absorption of commons and the eviction of tenants that agrarian warfare — the expression is not too modern or too strong — is waged in the sixteenth century.”[14]

An unsuccessful crusade

Tudor Monarchs

| Henry VII |

1485–1509 |

| Henry VIII |

1509–1547 |

| Edward VI |

1547–1553 |

| Mary I |

1553–1558 |

| Elizabeth I |

1558–1603 |

The Tudor monarchs who ruled England from 1485 to 1603 were unable to halt the destruction of the commons and the spread of agrarian capitalism, but they didn’t fail for lack of trying. A general Act Against Pulling Down of Towns was enacted in 1489, just four years after Henry VII came to power. Declaring that “in some towns two hundred persons were occupied and lived by their lawful labours [but] now two or three herdsmen work there and the rest are fallen in idleness,”[15] the Act forbade conversion of farms of 20 acres or more to pasture, and ordered landlords to maintain the existing houses and buildings on all such farms.

Further anti-enclosure laws were enacted in 1515, 1516, 1517, 1519, 1526, 1534, 1536, 1548, 1552, 1555, 1563, 1589, 1593, and 1597. In the same period, commissions were repeatedly appointed to investigate and punish violators of those laws. The fact that so many anti-enclosure laws were enacted shows that while the Tudor government wanted to prevent depopulating enclosure, it was consistently unable to do so. From the beginning, landlords simply disobeyed the laws. The first Commission of Enquiry, appointed in 1517 by Henry VIII’s chief advisor Thomas Wolsey, identified 1,361 illegal enclosures that occurred after the 1489 Act was passed.[16] Undoubtedly more were hidden from the investigators, and even more were omitted because landlords successfully argued that they were formally legal.[17]

The central government had multiple reasons for opposing depopulating enclosure. Paternalist feudal ideology played a role — those whose wealth and position depended on the labor of the poor were supposed to protect the poor in return. More practically, England had no standing army, so the king’s wars were fought by peasant soldiers assembled and led by the nobility, but evicted tenants would not be available to fight. At the most basic level, fewer people working the land meant less money collected in taxes and tithes. And, as we’ll discuss in Part Three, enclosures caused social unrest, which the Tudors were determined to prevent.

Important as those issues were, for a growing number of landlords they were outweighed by their desire to maintain their income in a time of unprecedented inflation, driven by debasement of the currency and the influx of plundered new world silver. “During the price revolution of the period 1500-1640, in which agricultural prices rose by over 600 per cent, the only way for landlords to protect their income was to introduce new forms of tenure and rent and to invest in production for the market.”[18]

Smaller gentry and well-off tenant farmers did the same, in many cases more quickly than the large landlords. The changes they made shifted income from small farmers and farmworkers to capitalist farmers, and deepened class divisions in the countryside.

“Throughout the sixteenth century the number of smaller lessees shrank, while large leaseholding, for which accumulated capital was a prerequisite, became increasingly important. The sixteenth century also saw the rise of the capitalist lessee who was prepared to invest capital in land and stock. The increasing divergence of agricultural prices and wages resulted in a ‘profit inflation’ for capitalist farmers prepared and able to respond to market trends and who hired agricultural labor.”[19]

As we’ve seen, the Tudor government repeatedly outlawed enclosures that removed tenant farmers from the land. The laws failed because enforcement depended on justices of the peace, typically local gentry who, even if they weren’t enclosers themselves, wouldn’t betray neighbors and friends who were. Occasional Commissions of Enquiry were more effective — and so were hated by landlords — but their orders to remove enclosures and reinstate former tenants were rarely obeyed, and fines could be treated as a cost of doing business.

From monks to investors

The Tudors didn’t just fail to halt the advance of capitalist agriculture, they unintentionally gave it a major boost. As Marx wrote, “the process of forcible expropriation of the people received a new and terrible impulse in the sixteenth century from the Reformation, and the consequent colossal spoliation of church property.”[20]

Between 1536 and 1541, seeking to reform religious practice and increase royal income, Henry VIII and his chief minister Thomas Cromwell disbanded nearly 900 monasteries and related institutions, retired their occupants, and confiscated their lands and income.

This was no small matter — together, the monasteries’ estates comprised between a quarter and a third of all cultivated land in England and Wales. If he had kept it, the existing rents and tithes would have tripled the king’s annual income. But in 1543 Henry, a small-country king who wanted to be a European emperor, launched a pointless and very expensive war against Scotland and France, and paid for it by selling off the properties he had just acquired. When Henry died in 1547, only a third of the confiscated monastery property remained in royal hands; almost all that remained was sold later in the century, to finance Elizabeth’s wars with Spain.[21]

The sale of so much land in a short time transformed the land market and reshaped classes. As Christopher Hill writes, “In the century and a quarter after 1530, more land was bought and sold in England than ever before.”

“There was relatively cheap land to be bought by anyone who had capital to invest and social aspirations to satisfy…. By 1600 gentlemen, new and old, owned a far greater proportion of the land of England than in 1530 — to the disadvantage of crown, aristocracy and peasantry alike.

“Those who acquired land in significant quantity became gentlemen, if they were not such already … Gentlemen leased land — from the king, from bishops, from deans and chapters, from Oxford and Cambridge colleges — often in order to sub-let at a profit. Leases and reversions sometimes lay two deep. It was a form of investment…. The smaller gentry gained where big landlords lost, gained as tenants what others lost as lords.”[22]

As early as 1515, there were complaints that farmland was being acquired by men not from the traditional landowning classes — “merchant adventurers, clothmakers, goldsmiths, butchers, tanners and other artificers who held sometimes ten to sixteen farms apiece.”[23] When monastery land came available, owning or leasing multiple farms, known as engrossing, became even more attractive to urban businessmen with capital to spare. Some no doubt just wanted the prestige of a country estate, but others, used to profiting from their investments, moved to impose shorter leases and higher rents, and to make private profit from common land.

A popular ballad of the time expressed the change concisely:

“We have shut away all cloisters,

But still we keep extortioners.

We have taken their land for their abuse,

But we have converted them to a worse use.”[24]

Hysterical exaggeration?

Early in the 1900s, conservative economist E.F. Gay — later the first president of the Harvard Business School — wrote that 16th century accounts of enclosure were wildly exaggerated. Under the influence of “contemporary hysterics” and “the excited sixteenth century imagination,” a small number of depopulating enclosures were “magnified into a menacing social evil, a national calamity responsible for dearth and distress, and calling for drastic legislative remedy.” Popular opposition reflected not widespread hardship, but “the ignorance and hide-bound conservatism of the English peasant,” who combined “sturdy, admirable qualities with a large admixture of suspicion, cunning and deceit.” [25]

Gay argued that the reports produced by two major commissions to investigate enclosures show that the percentage of enclosed land in the counties investigated was just 1.72% in 1517 and 2.46% in 1607. Those small numbers “warn against exaggeration of the actual extent of the movement, against an uncritical acceptance of the contemporary estimate both of the greatness and the evil of the first century and a half of the ‘Agrarian Revolution.’”[26]

Ever since, Gay’s argument has been accepted and repeated by right-wing historians eager to debunk anything resembling a materialist, class-struggle analysis of capitalism. The most prominent was Cambridge University professor Sir Geoffrey Elton, whose bestselling book England Under the Tudors dismissed critics of enclosure as “moralists and amateur economists” for whom landlords were convenient scapegoats. Despite the complaints of such “false prophets,” enclosers were just good businessmen who “succeeded in sharing the advantages which the inflation offered to the enterprising and lucky.” And even then, “the whole amount of enclosure was astonishingly small.”[27]

The claim that enclosure was an imaginary problem is improbable, to say the least. R.H. Tawney’s 1912 response to Gay applies with full force to Elton and his conservative co-thinkers.

“To suppose that contemporaries were mistaken as to the general nature of the movement is to accuse them of an imbecility which is really incredible. Governments do not go out of their way to offend powerful classes out of mere lightheartedness, nor do large bodies of men revolt because they have mistaken a ploughed field for a sheep pasture.”[28]

The reports that Gay analyzed were important, but far from complete. They didn’t cover the whole country (only six counties in 1607), and their information came from local “jurors” who were easily intimidated by their landlords. Despite the dedication of the commissioners, it is virtually certain that their reports understated the number and extent of illegal enclosures.

And, as Tawney pointed out, enclosure as a percentage of all land doesn’t tell us much about its economic and social impact — the real issue is how much farmed land was enclosed.

In 1979, John Martin reanalysed Gay’s figures for the most intensely farmed areas of England, the ten Midlands counties where 80% of all enclosures took place. He concluded that in those counties over a fifth of cultivated land had been enclosed by 1607, and that in two counties enclosure exceeded 40%. Contrary to Elton’s claim, those are not “astonishingly small” figures — they support Martin’s conclusion that “the enclosure movement must have had a fundamental impact upon the agrarian organization of the Midlands peasantry in this period.” [29]

It’s important to bear in mind that enclosure, as narrowly defined by Tudor legislation and Inquiry commissions, was only part of the restructuring that was transforming rural life. W.G, Hoskins emphasizes that in The Age of Plunder:

“The importance of engrossing of farms by bigger men was possibly a greater social problem than the much more noisy controversy over enclosures, if only because it was more general. The enclosure problem was largely confined to the Midlands … but the engrossing of farms was going on all the time all over the country.”[30]

George Yerby elaborates.

“Enclosure was one manifestation of a broader and less formal development that was working in exactly the same direction. The essential basis of the change, and of the new economic balance, was the consolidation of larger individual farms, and this could take place with or without the technical enclosure of the fields. This also serves to underline the force of commercialization as the leading trend in changes in the use and occupation of the land during this period, for the achievement of a substantial marketable surplus was the incentive to consolidate, and it did not always require the considerable expense of hedging.”[31]

More large farms meant fewer small farms, and more people who had no choice but to work for others. The twin transformations of primitive accumulation — stolen land becoming capital and landless producers becoming wage workers — were well underway.

Notes

[1] William Harrison, The Description of England: The Classic Contemporary Account of Tudor Social Life, ed. Georges Edelen (Folger Shakespeare Library, 1994), 217.

[2] Jim Holstun, “Utopia Pre-Empted: Ketts Rebellion, Commoning, and the Hysterical Sublime,” Historical Materialism 16, no. 3 (2008), 5.

[3] Quoted in Martin Empson, Kill All the Gentlemen: Class Struggle and Change in the English Countryside (Bookmarks Publications, 2018), 162.

[4] Diarmaid MacCulloch and Anthony Fletcher, Tudor Rebellions, 6th ed. (Routledge, 2016), 70.

[5] Andy Wood, Riot, Rebellion and Popular Politics in Early Modern England (Palgrave, 2002), 66-7.

[6] Karl Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, (Penguin Books, 1976), 886.

[7] Thomas More, Utopia, trans. Robert M. Adams, ed. George M. Logan, 3rd ed. (Cambridge University Press, 2016), 19.

[8] A. R. Myers, ed., English Historical Documents, 1327-1485, vol. 4 (Routledge, 1996), 1031. “Emparking” meant converting farmland into private forests or parks, where landlords could hunt.

[9] Ibid., 1029.

[10] More, Utopia, 19-20.

[11] R. H. Tawney, The Agrarian Problem in the Sixteenth Century (Lector House, 2021 [1912]), 7.

[12] Tawney, Agrarian Problem, 110.

[13] R. H. Tawney and E. E. Power, eds., Tudor Economic Documents, Vol. 1. (Longmans, Green, 1924), 39, 41. Spelling modernized.

[14] Tawney, Agrarian Problem, 124, 175.

[15] Quoted in M. W. Beresford, “The Lost Villages of Medieval England,” The Geographical Journal 117, no. 2 (June 1951), 132. Spelling modernized.

[16] Spencer Dimmock, “Expropriation and the Political Origins of Agrarian Capitalism in England,” in Case Studies in the Origins of Capitalism, ed. Xavier Lafrance and Charles Post (Palgrave MacMillan, 2019), 52.

[17] The Statute of Merton, enacted in 1235, allowed landlords to take possession of and enclose common land, so long as sufficient remained to meet customary tenants’ rights. In the 1500s that long-disused law provided a loophole for enclosing landlords who defined “sufficient” as narrowly as possible.

[18] Martin, Feudalism to Capitalism, 131.

[19] Martin, Feudalism to Capitalism, 133.

[20] Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, 883.

[21] Perry Anderson, Lineages of the Absolutist State (Verso, 1979), 124-5.

[22] Christopher Hill, Reformation to Industrial Revolution: A Social and Economic History of Britain, 1530-1780 (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1967), 47-8.

[23] Joan Thirsk, “Enclosing and Engrossing, 1500-1640,” in Agricultural Change: Policy and Practice 1500-1750, ed. Joan Thirsk (Cambridge University Press, 1990), 69.

[24] Quoted in Thomas Edward Scruton, Commons and Common Fields (Batoche Books, 2003 [1887]), 73.

[25] Edwin F. Gay, “Inclosures in England in the Sixteenth Century,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 17, no. 4 (August 1903), 576-97; “The Inclosure Movement in England,” Publications of the American Economic Association 6, no. 2 (May 1905), 146-159.

[26] Edwin F. Gay, “The Midland Revolt and the Inquisitions of Depopulation of 1607,” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 18 (1904), 234, 237.

[27] G. R. Elton, England under the Tudors (Methuen, 1962), 78-80.

[28] Tawney, Agrarian Problem, 166.

[29] John E. Martin, Feudalism to Capitalism: Peasant and Landlord in English Agrarian Development (Macmillan Press, 1986), 132-38.

[30] W. G. Hoskins, The Age of Plunder: The England of Henry VIII 1500-1547, Kindle ed. (Sapere Books, 2020 [1976]), loc. 1256.

[31] George Yerby, The Economic Causes of the English Civil War (Routledge, 2020), 48.

by DGR News Service | Jan 15, 2020 | Culture of Resistance

This excerpt from Chapter 4 of the book Deep Green Resistance: Strategy to Save the Planet was written by Lierre Keith. Click the link above to purchase the book or read online for free. This is part 3 of this chapter. Part 1 is here, part 2 is here.

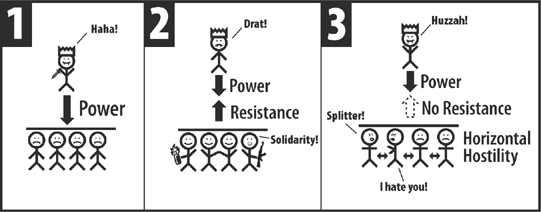

Radical groups have their own particular pitfalls. The first is in dealing with hierarchy, both conceptually and practically. The rejection of authority is another hallmark of adolescence, and this knee-jerk reactivity filters into many political groups. All hierarchy is a tool of The Man, the patriarchy, the Nazis. This approach leads to an insistence on consensus at any cost and often a constant metadiscussion of group power dynamics. It also unleashes “critiques” of anyone who achieves public acclaim or leadership status. These critiques are usually nothing more than jealousy camouflaged by political righteousness. “Bourgeois” is a perennial favorite, as well as whatever flavor of “sell-out” matches the group’s criteria. It’s often accompanied by a hyperanalysis of the victim’s language use or personal lifestyle choices. There is a reason that the phrase “politically correct” was invented on the left.51

There’s a name for this trashing. As noted, Florynce Kennedy called it “horizontal hostility.”52 And if it feels like junior high school by another name, that’s because it is. It can reach a feeding frenzy of ugly gossip and character assassination. In more militant groups, it may take the form of paranoid accusations. In the worst instances of the groups that encourage macho posturing, it ends with men shooting each other. Ultimately, it’s caused by fighting horizontally rather than vertically (see Figure 3-1, p. 85). If the only thing we can change is ourselves or if the best tactics for social change are lifestyle choices, then, indeed, examining and critiquing the minutiae of people’s personal lives will be cast as righteous activity. And if you’re not going to fight the people in power, the only people left to fight are each other. Writes Denise Thompson,

Horizontal hostility can involve bullying into submission someone who is no more privileged in the hierarchy of male supremacist social relations than the bully herself. It can involve attempts to destroy the good reputation of someone who has no more access to the upper levels of power than the one who is spreading the scandal. It can involve holding someone responsible for one’s own oppression, even though she too is oppressed. It can involve envious demands that another woman stop using her own abilities, because the success of someone no better placed than you yourself “makes” you feel inadequate and worthless. Or it can involve attempts to silence criticism by attacking the one perceived to be doing the criticising. In general terms, it involves misperceptions of the source of domination, locating it with women who are not behaving oppressively.53

This behavior leaves friendships, activist circles, and movements in shreds. The people subject to attack are often traumatized until they permanently withdraw. The bystanders may find the culture so unpleasant and even abusive that they leave as well. And many of the worst aggressors burn out on their own adrenaline, to drop out of the movement and into mainstream lives. In military conflicts, more soldiers may be killed by “friendly fire” than the enemy, an apt parallel to how radical groups often self-destruct.

To be viable, a serious movement needs a supportive culture. It takes time to witness the same behaviors coalescing into the destructive patterns that repeat across radical movements, to name them, and to learn to stop them. Successful cultures of resistance are able to develop healthy norms of behavior and corresponding processes to handle conflict. But a youth culture by definition doesn’t have that cache of experience, and it never will.

A culture of resistance also needs the ability to think long-term. One study of student activists from the Berkeley Free Speech Movement interviewed participants five years after their sit-in. Many of them felt that the movement—and hence political action—was unsuccessful.54 Five years? Try five generations. Movements for serious social change take a long time. But a youth movement will be forever delinked from generations.

Contrast the (mostly white) ex-protestors’ attitude with the history of the Pullman porters, the black men who worked as sleeping car attendants on the railroad. The porters were both the generational and political link between slavery and the civil rights movement, accumulating income, self-respect, and the political experience they would need to wage the protracted struggle to end segregation. The very first Pullman porters were in fact formerly enslaved men. George Pullman hired them because they were people who, tragically, could act subserviently enough to make the white passengers happy. (When Pullman tried hiring black college kids from the North for summer jobs as porters, the results were often disastrous.) Yet the jobs offered two things in exchange for the subservience: economic stability (despite the gruesomely long hours) and a broadening outlook. Writes historian Larry Tye:

The importance of education was drilled into porters on the sleepers, where they got an up-close look at America’s elite that few black men were afforded, helping demystify the white race at the same time it made its advantages seem even more unfair and enticing. That was why they worked so hard for tips, took on second jobs at home, and bore the indignities of the race-conscious sleeping cars. . . . It was an accepted wisdom that they turned out more college graduates than anyone else. And those kids, whether or not they made lists of the most famous, grew up believing they could do anything. The result . . . was that Pullman porters helped give birth to the African-American professional classes.55

The porters knew that in their own lives they would only get so far. But their children were raised to carry the struggle forward. The list of black luminaries with Pullman porters in their families is impressive, from John O’Bryant (San Francisco’s first black mayor) to Florynce Kennedy to Justice Thurgood Marshall. Civil rights lawyer Elaine Jones, whose father worked as a porter to put his three kids through prestigious universities, has this to say: “All he expected in return was that we had a duty to succeed and give back. Dad said, ‘I’m doing this so they can change things.’ He won through us.”56

One reason the civil rights struggle was successful was that there was a strong linkage between the generations, an unbroken line of determination, character, and courage, that kept the movement pushing onward as it accumulated political wisdom.

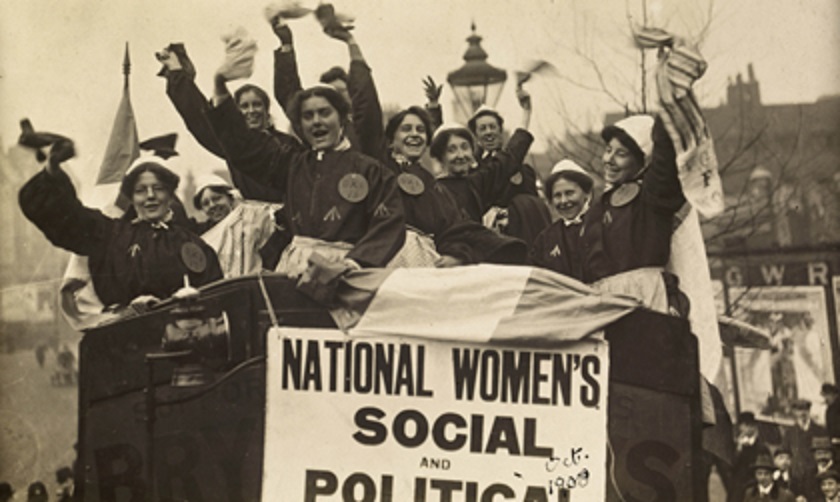

The gift of youth is its idealism and courage. That courage may veer into the foolhardy due to the young brain’s inability to foresee consequences, but the courage of the young has been a prime force in social movements across history. For instance, Sylvia Pankhurst describes what happened when the suffragist Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) embraced arson as a tactic:

In July 1912, secret arson began to be organized under the direction of Christabel Pankhurst. When the policy was fully under way, certain officials of the Union were given, as their main work, the task of advising incendiaries, and arranging for the supply of such inflammable material, house-breaking tools, and other matters as they might require. A certain exceedingly feminine-looking young lady was strolling about London, meeting militants in all sorts of public and unexpected places to arrange for perilous expeditions. Women, most of them very young, toiled through the night across unfamiliar country, carrying heavy cases of petrol and paraffin. Sometimes they failed, sometimes succeeded in setting fire to an untenanted building—all the better if it were the residence of a notability—or a church, or other place of historic interest.57 (emphasis added)

Add to this that they performed these activities—including scaling buildings, climbing hedges, and running from the police—while wearing corsets and encumbered by pounds of skirting. It’s overwhelmingly the young who are willing and able to undertake these kinds of physical risks.

A great example of a working relationship between youth and elders is portrayed in the film Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance.58 The movie documents the Oka crisis (mentioned in Chapter 6), in which Mohawk people protected their burial ground from being turned into a golf course. The conflict escalated as the defenders barricaded roads and the local police were replaced by the army. Alanis Obomsawin was behind the barricades, so her film is not a fictional replay, but actual footage of the events. Of note here is the number of times she captured the elders—with their fully functioning prefrontal cortexes—stepping between the youth and trouble, telling them to calm down and back away. Without the warriors, the blockade never would have happened; without the elders, it’s likely there would have been a massacre.

Youth’s moral fervor and intolerance of hypocrisy often results in either/or thinking and drawing too many lines in the sand, but serious movements need the steady supply of idealism that the young provide. The psychological task of middle age is to remember that idealism helps protect against the rough wear of disappointment. Adulthood also brings responsibilities that the young can’t always understand. Having children, for instance, will put serious constraints on activism. Aging parents who need care and support cannot be abandoned. And then there’s the activist’s own basic survival needs, the demands of shelter, food, health care. The older people need the young to bring idealism and courage to the movement.

The women’s suffrage movement started with a generation of women who asked nicely. In an age when women had no right to ask for anything, they did the best they could. The struggle, like that of the Pullman porters and the succeeding civil rights movement, was handed down to the next generation. Emmeline Pankhurst recalls a childhood of fund raisers to help newly freed blacks in the US, attending her first women’s suffrage meeting at age fourteen, and bedtime stories from Uncle Tom’s Cabin. She wrote,

Those men and women are fortunate who are born at a time when a great struggle for human freedom is in progress. It is an added good fortune to have parents who take a personal part in the great movements of their time. . . . Young as I was—I could not have been older than five years—I knew perfectly well the meaning of the words “slavery” and “emancipation.”59

Emmeline married Dr. Richard Pankhurst, who drafted the first women’s suffrage bill and the Married Women’s Property Act, which, when it passed in 1882, gave women control over their own wages and property. Up until then, women did not even own the clothes on their backs—men did. (The next time you buy your own shirt with your own money, remember to thank all Pankhursts great and small.) Emmeline and Richard’s daughters, Sylvia and Christabel, were the third generation of Pankhursts born to be activists. It was in large part the infusion of their youthful idealism and courage that fueled the battle for women’s suffrage. Emmeline wrote,

All their lives they had been interested in women’s suffrage. Christabel and Sylvia, as little girls, had cried to be taken to meetings. They had helped in our drawing-room meetings in every way that children can help. As they grew older we used to talk together about the suffrage, and I was sometimes rather frightened by their youthful confidence in the prospect, which they considered certain, of the success of the movement. One day Christabel startled me with the remark: “How long you women have been trying for the vote. For my part, I mean to get it.”

Was there, I reflected, any difference between trying for the vote and getting it? There is an old French proverb, “If youth could know; if age could do.” It occurred to me that if the older suffrage workers could in some way join hands with the young, unwearied, and resourceful suffragists, the movement might wake up to new life and new possibilities. After that I and my daughters together sought a way to bring about that union of young and old which would find new methods, blaze new trails.60

Emmeline raised her girls in a serious culture of resistance. As a strategist, she wisely understood that the moment was ripe for the young to push the movement on to new tactics. Thus was formed the WSPU. “We resolved to . . . be satisfied with nothing but action on our question. ‘Deeds, not Words’ was to be our permanent motto.”61 Those deeds would run to harassing government officials, civil disobedience, hunger strikes, and arson. They would also be successful.

The transition from one generation to the next, and an increase in confrontational tactics, is rarely smooth. The older activists may try to obstruct the young. It often splits movements. When the WSPU embraced more militance, women who had been crucial to its founding had to leave the organization. Wrote Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence,

Mrs. Pankhurst met us with the announcement that she and Christabel had determined on a new kind of campaign. Henceforward she said there was to be a widespread attack upon public and private property, secretly carried out by Suffragettes who would not offer themselves for arrest, but wherever possible would make good their escape. As our minds had been moving in quite another direction, this project came as a shock to us both. We considered it sheer madness . . . Although we had been at one with Mrs. Pankhurst in her objective of women’s political emancipation, and for six years had pursued the same path, there had always been an underlying difference between us that had not come into the open, mainly because of the close union of mind and purpose . . . we found ourselves for the first time in something that resembled a family quarrel.62

These are painful moments inside organizations and across movements. But it is more or less inevitable. The overall pattern is one we should be aware of so we can work with it rather than struggling against it. This transition is likely to be linked with the ethical issues around nonviolence. As with those disagreements, we have to find a way to build a serious movement despite our differences.

Building radical movements has been harder since the creation of a youth culture. Breaking the natural bonds (could there be a deeper bond than the cross generational one between mother and child?) between young and old means that the political wisdom never accumulates. It also means that the young are never socialized into a true culture of resistance. The values of a youth culture—an adolescent stance rejecting all constraints—prevent both the “culture” and the “resistance” from really developing. No culture can exist without community norms based on responsibility to each other and some accepted ways to enforce those norms. And the “resistance” will never amount to more than a few smashed windows, the low-hanging tactical fruit for an adolescent strategy of emotional intensity.

Currently there are young people emboldened by a desperate fearlessness, ready to take up militance. I get notes from them all the time; each one both revives and drains my hope. Because, though they burn for action, they have no guidance and no support. This is the deep irony of history: the countercultures of the Romantics, the Wandervogel, the hippies—created by youth—have stranded our young.

This chapter will be continued next week. For references, visit this link to read the book Deep Green Resistance: Strategy to Save the Planet online or to purchase a copy.

Featured image via Truthout flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.