by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Dec 8, 2016 | Human Supremacy, Strategy & Analysis

by Alex Jensen / Local Futures

In 2015, a major study of 24 indicators of human activity and environmental decline titled “The Great Acceleration” concluded that, “The last 60 years have without doubt seen the most profound transformation of the human relationship with the natural world in the history of humankind”.[1] We have all seen aspects of these trends, but to look at the study’s 24 graphs together is to apprehend, at a glance, the totality of the monstrous scale and speed of modern economic activity. According to lead author W. Steffen, “It is difficult to overestimate the scale and speed of change. In a single lifetime humanity has become a planetary-scale geological force.”[2]

Every indicator of intensity and scale of economic activity — from global trade and investment to water and fertilizer use, from pollution of every sort to destruction of environments and biodiversity — has shot up, precipitously, beginning around 1950. The graphs for every such trend point skyward still.

The Great Acceleration is manifest everywhere, including many areas not covered in the study. It is impossible to directly, humanly appreciate the ghastly scale of change. Only statistics can do that. For example:

- Humans now extract and move more physical material than all natural processes combined. Global material extraction has grown by more than 90 percent over the past 30 years, reaching almost 70 billion tons today.[3]

- In this century “global economic output expanded roughly 20-fold, resulting in a jump in demand for different resources of anywhere between 600 and 2,000 percent”.[4]

- For more than 50 years, global production of plastic has continued to rise.[5] Today, around 300 million tons of plastic are produced globally each year. “About two thirds of this is for packaging; globally, this translates to 170 million tons of plastic largely created to be disposed of after one use.”[6]

- The global sale of packaged foods has jumped more than 90 percent over the last decade, with 2012 sales topping $2.2 trillion.[7]

- “In the last 50 years, a staggering 140 million hectares… has been taken over by four industrial crops: soya bean, oil palm, rapeseed and sugar cane. These crops don’t feed people. They are grown to feed the agro-industrial complex.”[8]

Not only are the scale and speed of materials extraction, production, consumption and waste ballooning, but so too the scale and pace of the movement of materials through global trade. For instance, trade volumes in physical terms have increased by a factor of 2.5 over the past 30 years. In 2009, 2.3 billion tons of raw materials and products were traded around the globe.[9] Maritime traffic on the world’s oceans has increased four-fold over the past 20 years, causing more water, air and noise pollution on the open seas.[10]

Not only are the scale and speed of materials extraction, production, consumption and waste ballooning, but so too the scale and pace of the movement of materials through global trade. For instance, trade volumes in physical terms have increased by a factor of 2.5 over the past 30 years. In 2009, 2.3 billion tons of raw materials and products were traded around the globe.[9] Maritime traffic on the world’s oceans has increased four-fold over the past 20 years, causing more water, air and noise pollution on the open seas.[10]

While it may be correct, generically, to ascribe all these signs of the Great Acceleration to “humanity” or “human activity” as a whole, this ascription is also flawed. Indeed, the study concludes that the global economic system in particular has been a primary driver of the Great Acceleration. The graphs of economic activity (such as the amount of foreign direct investment or the number of McDonald’s restaurants) and environmental decline (such as biodiversity loss, forest loss, percentage of fisheries “fully exploited,” etc.) look identical from a distance — both shooting dizzyingly upward since 1950. The resemblance is not coincidental. The latter are a consequence of the former.

This expansion of global economic activity has been driven forward by the dynamics of capitalism and the pursuit of endless profits: by marketing and advertising; by subsidies and sops to industry of every stripe; and by the concomitant destruction of local, self-reliant communities around the world. In the process, much of “humanity” has been swept into the jetsam of the overall economic system. While this system may be the product of some human designs, to confuse it with humanity at large is to get the story backward.

One incontrovertible conclusion of all this, it seems to me, is that it is precisely the increasing scale of economic activity – of “the economy” – that is the heart of the multiple interlocking crises that beset societies and the earth today. The relentlessly expansionist logic of the system is inimical to life, to the world, even to genuine well-being. If we wish to instead honor, defend, and respect life and the world, we must upend that logic, and begin the urgent task of down-scaling economic activity and the system that drives it. We must embark upon the “Great Deceleration.”

Nevertheless, from every organ of the establishment, where the commercial mind reigns, we hear that the challenge before us is not deceleration, but making the great acceleration even greater by ramping up production and consumption still further. Even as governments expound solemnly on the need to arrest climate change and promote Sustainable Development Goals, they are handing over nearly boundless subsidies to industry, pushing for the expansion of global trade, and otherwise facilitating the acceleration of the acceleration.

Projections based on the assumption that the great acceleration will continue ad infinitum show, for example, that the number of cars will nearly double from 1.1 billion today, to 2 billion by 2040; that seaborne trade will increase from 54 to 286 trillion ton-miles; that global GDP will climb from $69 trillion to $164 trillion; and so on. As a news article reporting the projections declares, “If there’s a common theme, it’s that there’s going to be more of everything in the years ahead”.[11] By 2025, the output of solid waste is expected to grow 70 percent, from 3.5 to more than 6 million tons per day.[12] Leaving aside the actual feasibility of such growth – given biophysical limits that are already well-surpassed – the very fact that the political and economic establishment takes such growth for granted and will continue to pursue it heedlessly is cause for grave concern.

In India, chemical and physical pollution occasioned by the frenzied rush of industrial development has become so treacherous that it is deforming air and water into poisons to be avoided at the risk of health and life itself. Mephitic mountains of plastic waste choke every town and city, clog drains, suffocate rivers and shores, fill the stomachs of animals. Pesticides have killed soil and farmers alike across the country. Despite these and so many other manifestations of ecocide, industry and the government — central and state-level alike — clamor for more of it, faster. Because it is a ‘developing’ country, we are told, the average Indian vastly underconsumes plastic, energy, cars, et al. Cultural traditions of thrift and sharing, wherever they still hang on, are seen as nettlesome but surmountable barriers to keeping the growth machine growing, faster. Replacing each and every one of those traditional practices with packaged, often disposable, commodities is an explicit goal of industry. Relentlessly generating novel needs is another. The current government’s “Make In India” program, marketed to attract foreign investors and businesses, is the latest campaign to fuel this process.[13]

In India, chemical and physical pollution occasioned by the frenzied rush of industrial development has become so treacherous that it is deforming air and water into poisons to be avoided at the risk of health and life itself. Mephitic mountains of plastic waste choke every town and city, clog drains, suffocate rivers and shores, fill the stomachs of animals. Pesticides have killed soil and farmers alike across the country. Despite these and so many other manifestations of ecocide, industry and the government — central and state-level alike — clamor for more of it, faster. Because it is a ‘developing’ country, we are told, the average Indian vastly underconsumes plastic, energy, cars, et al. Cultural traditions of thrift and sharing, wherever they still hang on, are seen as nettlesome but surmountable barriers to keeping the growth machine growing, faster. Replacing each and every one of those traditional practices with packaged, often disposable, commodities is an explicit goal of industry. Relentlessly generating novel needs is another. The current government’s “Make In India” program, marketed to attract foreign investors and businesses, is the latest campaign to fuel this process.[13]

No matter how polluting, how much land and water are required, how many communities will be displaced and livelihoods destroyed, the formula is basically the same: more mines, more coal and power plants, more tourism. More and more of everything. For every industry, every product, every process that has swelled to become a planetary-scale abscess, the normal prescription that should obtain — “stop the swelling!” — is inverted. The out-of-control global economic system needs more and more growth just to feed and maintain itself.

In defense of this system one may hear some version of the refrain: “These are the unfortunate costs we must pay to alleviate poverty, improve human well-being, and provide enough for all.” This argument has become embarrassingly spurious. It is now widely known that not only has the great up-scaling bequeathed the planet and its inhabitants a legacy of destruction, ugliness, and waste, but its prodigious production and profit has failed to make a dent in the hunger and privation suffered by hundreds of millions. At the same time, it has unleashed a storm of junk food and diet-related diseases across the planet, which has persecuted the poor the worst. The menacing pollution attendant to the great acceleration also harms the poor the worst. It exacerbates poverty even as it churns the planet into money. Meanwhile, those most enriched in the process amount to a conference-room-sized group of individuals. The statistics will likely have grown even more outlandish by the time this is read: the world’s 62 richest people own as much wealth as the poorest half of humanity.[14]

This system of plunder and inequality has, unsurprisingly, left in its wake demoralized human souls. The great acceleration and loneliness, depression, anxiety and estrangement are two sides of the same sinister coin; paralyzed and tyrannized by a surfeit of superficial ‘choice’, by loss of meaning and connection, even the supposed beneficiaries of this system have been made miserable by it.[15]

So the increasing scale and speed of the economy is, for the vast majority, the enemy of prosperity. This fact offers some hope, for reducing the scale and speed of the economy provides the possibility of relief and reclamation of contentment for those afflicted by affluence, while at the same time providing not “growth” — which the poor have never and will never be able to eat — but the actual material needs that are being trampled beneath the very stampede of growth that is supposed to deliver those needs. The great up-scaling is a sybaritic saturnalia for an infinitesimally small and incomprehensibly moneyed elite. It is everyone else’s curse.

Downscaling the economy, therefore, is not only necessary to save and perhaps enable regeneration of our beleaguered earthly home; it is also a genuinely humane, anti-poverty agenda. This may sound counter-intuitive to those marinading in trickle-down theory.

Upsetting the great acceleration juggernaut will require innumerable, profound systemic shifts. Since the regnant system is not the consequence but rather the cause of consumerism, acquisitiveness, separation, alienation, etc., it will require first and foremost resistance to the forces that relentlessly propagate it — stopping corporate plunder of all sorts (from mines to minds); stopping and revoking neoliberal ‘free trade’ agreements; breaking up and dismantling corporate-state power and the legal frameworks that underpin it; and, challenging the fundamentalist logic of unlimited growth. It will simultaneously require the (re)construction of radical alternative systems, rooted in environmental ethics, ecological integrity, social justice, decentralization and deep democracy, beauty, simplicity, cooperation, sharing, slowness, and a constellation of related eco-social-ethical values.

But where will the motive to act either in resistance or in regeneration come from, if the values of commercialized growth societies — competition, individualism, narcissism, nihilism, avarice — are so deeply indoctrinated? How can the opposite values be resuscitated after decades or centuries of anesthetization and repression? The fact is that all over the world, there has always been and continues to be tremendous push-back against the system, along with nurturance of countless alternatives. This is testament not only to human resilience and common sense, but to the utter asynchrony of this system with the genuine well-being of people.

To acknowledge and celebrate this spirited and widespread push-back is not to be complacent or naïve about the terrifying hegemony and momentum of the great acceleration. It is, rather, precisely to disrupt the complacency and debilitation of “inevitablism.”

Thankfully, all over the world, vibrant movements of resistance-(re)construction both new and ancient are saying loudly, “we are ready to stop being trickled-down upon.” The Degrowth movement is assailing the status quo assumption of a cozy positive relationship between economic growth and well-being and even (weirdly) environmental “improvement.” Its many exponents and activists are broadcasting the reality of the obvious-to-all-but-economists inverse relationship between growth and well-being. Given that the economy today is vastly exceeding what the planet and its denizens can give and take, degrowth — as its name announces — promotes not merely slowing and stopping growth, but reversing it.

At centers like Can Decreix on the Mediterranean coast, the main argument of degrowth – that well-being improves and life becomes richer through sufficiency, commoning and technological-material downscaling – is practiced, demonstrated and shared. Human muscle and craft skill reclaim from machines simple, pleasurable subsistence work, done communally. Heat energy of the sun is used to bake bread and warm water. Music and fun become not something that must purchased on weekends, but part of the fabric of everyday. But it is not merely an escapist, “live your values while the world burns” sort of experiment; on the contrary, its members are deeply involved in the broader political struggles (e.g. against “free trade” treaties) that are a necessary corollary to living alternatively.

There are also many sister concepts and movements to degrowth, that, despite their differences, share some basic, fundamental values and perspectives. There is Buen Vivir/Sumak Kawsay emerging out of indigenous, eco-centric Andean cosmovisions, calling not for alternative development but alternatives to development, for affirmation and strengthening of traditional practices, knowledge systems, processes and relationships (human and non-human alike) that since time immemorial have embodied many of the qualities that movements (like degrowth) in industrialized locales are striving to re-create.[16]

There are also many sister concepts and movements to degrowth, that, despite their differences, share some basic, fundamental values and perspectives. There is Buen Vivir/Sumak Kawsay emerging out of indigenous, eco-centric Andean cosmovisions, calling not for alternative development but alternatives to development, for affirmation and strengthening of traditional practices, knowledge systems, processes and relationships (human and non-human alike) that since time immemorial have embodied many of the qualities that movements (like degrowth) in industrialized locales are striving to re-create.[16]

On the Andean altiplano, most Aymara and Quechua farming families still nurture, process and eat a spectacular varietal diversity of tubers, grains, legumes and other foods. One farmer I stayed with near Lake Titicaca grew 109 varieties of potato, plus dozens more of oca, olluco, mashua, quinoa, edible lupine, fava, wheat, barley, maize, and much more. He and his family, like the majority of other farming families there, provide most of their own milk, cheese, meat and wool from livestock like cows, alpacas, goats and sheep. They live in houses fashioned from adobe bricks of local clay, roofed with local grass thatch. Their young children know dozens of wild medicinal plants. They do all this not as heroic, isolated survivalists, but in webs of community and earthly relationships of community, mutual aid, sharing and care. These communities have met their needs through local-regional economies – many based in barter – for centuries.[17] Are they thus perfect and free of all troubles? Of course not. But many of their worst troubles are imposed by capitalist industrialism and other forces of “progress.”

Perhaps the signal movement synthesizing resistance and (re)construction, ancient and contemporary, South and North, is the food sovereignty movement. This movement turns on its head 500 years of colonialist food policy, which would have everyone give up their food autonomy and diverse traditions and have peasants moved off the land into cities to become factory proletarians or, if remaining in the countryside, to become plantation proletarians exporting food calories, water and labor power – receiving in exchange paltry wages with which to shop for packaged “food-like stuff” in a global agribusiness supermarket. The movement inveighs against the political-economic forces that continue the war against peasants and subsistence economies, and demonstrates again and again the superiority (health, nutrition, productivity, ecological, social) of diverse, small, localized, cooperatively-worked, integrated polycultures of the sort that characterized food systems before the logic of the factory was imposed onto the land.[18]

These and many other movements are pointing the way back from the abyss into which the great acceleration has hurled us, directing us towards the Great Deceleration necessary to live again with affection and beauty on this earth.

This essay originally appeared in In Praise of Downscaling: 21st Century Conversations on How Small is Still Beautiful.

Photo credits: Indian trash heap: Juan del Rio; Andes grain winnowing: Alex Jensen.

Endnotes:

[1] Steffen, W., Broadgate, W., Deutsch, L., Gaffney, O., and Ludwig, C. (2015) ‘The trajectory of the Anthropocene: The Great Acceleration’, The Anthropocene Review, 16 January. http://anr.sagepub.com/content/early/2015/01/08/2053019614564785.abstract.

[2] http://www.stockholmresilience.org/research/research-news/2015-01-15-new-planetary-dashboard-shows-increasing-human-impact.html

[3] Giljum, S., Dittrich, M., Lieber, M., and Lutter, S. (2014) ‘Global Patterns of Material Flows and their Socio-Economic and Environmental Implications: A MFA Study on All Countries World-Wide from 1980 to 2009’, Resources 3, 319-339. www.mdpi.com/2079-9276/3/1/319/pdf.

[4] Dobbs, R., Oppenheim, J., Thompson, F., Brinkman, M., and Zornes, M. (2011) ‘Resource Revolution: Meeting the world’s energy, materials, food, and water needs’, McKinsey Global Institute.

[5] Worldwatch, 2015.

[6] Jowit, J. (2011) ‘Global hunger for plastic packaging leaves waste solution a long way off’, The Guardian, 29 December.http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2011/dec/29/plastic-packaging-waste-solution.

[7] Norris, J. (2013) ‘Make Them Eat Cake: How America is Exporting Its Obesity Epidemic’, Foreign Policy, 3 September. http://foreignpolicy.com/2013/09/03/make-them-eat-cake/.

[8] GRAIN (2014) ‘Hungry for Land: Small farmers feed the world with less than a quarter of all farmland’, GRAIN 28 May. http://www.grain.org/article/entries/4929-hungry-for-land-small-farmers-feed-the-world-with-less-than-a-quarter-of-all-farmland

[9] Giljum, S. et al, op. cit.

[10] American Geophysical Union (2014) ‘Worldwide ship traffic up 300 percent since 1992’, ScienceDaily, 17 November. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2014/11/141117130826.htm.

[11] Scutt, D. (2016) ‘This chart shows an insane forecast for worldwide growth of ships, cars, and people’, Business Insider Australia, 19 April.http://www.businessinsider.com.au/global-crude-oil-demand-emerging-markets-india-china-april-bernstein-2016-4.

[12] Hoornweg, D., and Bhada-Tata, P. (2012) ‘What a waste? A global review of solid waste management’, Urban development series knowledge papers; no. 15, Washington, DC: World Bank Group.http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/302341468126264791/What-a-waste-a-global-review-of-solid-waste-management.

[13] Make In India

[14] Oxfam (2016) ‘An economy for the 1%’, Oxfam Briefing Paper 210, 18 January.https://www.oxfam.org/sites/www.oxfam.org/files/file_attachments/bp210-economy-one-percent-tax-havens-180116-en_0.pdf.

[15] Monbiot, G. (2013) ‘One Rolex Short of Contentment’, The Guardian, 10 December. http://www.monbiot.com/2013/12/09/one-rolex-short-of-contentment/.

[16] Gudynas, E. (2011) ‘Buen Vivir: Today’s Tomorrow’, Development 54(4).http://www.gudynas.com/publicaciones/GudynasBuenVivirTomorrowDevelopment11.pdf.

[17] cf. Marti, N. and Pimbert, M. (2006) ‘Barter Markets: Sustaining people and nature in the Andes’, IIED. http://pubs.iied.org/14518IIED/, and Argumedo, A. and Pimbert, M. (2010) ‘Bypassing Globalization: Barter markets as a new indigenous economy in Peru’, Development 53(3). http://link.springer.com/article/10.1057%2Fdev.2010.43.

[18] Fitzgerald, D. (2003) Every Farm a Factory: The Industrial Ideal in American Agriculture, New Haven CT: Yale University Press.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | May 14, 2016 | Colonialism & Conquest, Indigenous Autonomy

By Jake Ling / Intercontinental Cry

This is the third installment of “The Guardians of Mother Earth,” an exclusive four-part series by Intercontinental Cry examining the Indigenous U’wa struggle for peace in Colombia.

Featured image: U’wa children are now taught their native language in the resguardo’s bilingual schools, as well as lessons in Natural Law: how to protect, care and safeguard Mother Earth. Photo: Jake Ling

In the cloud forests on the eastern cordillera of the Colombian Andes there is no internet, and phone reception is limited to a few lookouts on the craggy cliffs above the tree line. As news from the U’wa mobilization in the paramos surrounding the sacred Mount Zizuma filter down to the base of the mountain range in the Boyacá Frontier District on the Venezuelan border, Berito rests in his wooden shack recovering from tuberculosis. As he slowly convalesces, the indigenous leader has time to reflect on the struggle that has defined much of his life and can take pride in this next generation of pacifist U’wa warriors who have taken up the fight to save Mother Earth in his absence.

“When we start to educate, we need to educate two worlds,” Berito told IC. “One is of the west through its books, then there is the harmonious civilization of the spiritual, our own culture, which teaches peace with the environment and the house of nature.”

Education has been a key strategy to the U’wa leadership to ensure the tribe’s survival into the 21st century. Berito learned the importance of educating U’wa children about Natural Law, which predates and takes precedent over the laws of men, as the result of a childhood trauma: as a young boy, he was kidnapped by Catholic missionaries and forced to live in a convent until, after several years, his mother rescued him. The missionaries named him Roberto Cobaria, after the Cobaria river that ran past the mission. This arbitrary name followed him for most of his life as it was the name officially recognized by the Colombian government.

The 450 meter bridge that crosses the Cobaria River is what separates Berito’s house on the eastern border of the resguardo and the now reformed Catholic mission that once held him against his will. Photo: Jake Ling

The massive wooden convent that held the young Berito had enough rooms to house priests, nuns, cooks, cleaners, and at least 80 other abducted U’wa children. Today, however, this place that once perpetuated the cultural genocide of the U’wa has been transformed into a school that teaches their native language inside its classrooms with murals depicting their ancient mythology decorated along the walls. In the playground the unruly grass and patches of moss and lichens cover the cracked base of a neglected statue of the Virgin Mary, but the intergenerational scars left by the missionaries are evident in the survivors and their families.

“They took my mother when she was 6 or 7 years old and kept her there for about 16 years,” Luis Eduardo Caballero, the Fiscal (legal representative) of the U’wa Peoples, told IC. According to Caballero, the Catholic Church invaded from opposite ends of U’wa territory in the late 1940’s via the Andean plateaus of Boyacá as well as the lowlands beside the Cobaria and Arauca rivers. A rival evangelical organization called the Summer Institute of Linguistics, located a short drive outside of U’wa territory, was also involved in the systematic kidnapping of indigenous children.

“They prohibited our rituals, our fasts, our celebrations called the dance,” said Caballero, adding that the missionaries lured the children away under the guise of providing free education. Those inside the convent who spoke their native language were punished. “They weren’t able to make my mother stop speaking U’wa, but many others, yes.”

The Catholic mission that once perpetuated the cultural genocide of the U’wa has been transformed into a school that teaches the U’wa native language. Photo: Jake Ling

Murals depicting their ancient mythology are now decorated along the walls of the reformed Catholic mission. Photo: Jake Ling

As Berito grew to adulthood, he served as the governor of the U’wa and became a spiritual authority or Werjayá in the U’wa tongue, a shamanic healer in charge of communicating with the superior powers that inhabit nature: the rivers, the plants, the sun, and the stars. His childhood experience in the convent galvanized him to take the fight for his people’s rights outside the isolated cloud forests to the capital Bogotá and then beyond Colombia’s borders. It was only until December of last year, that Berito traveled to a judicial office in the capital to officially change his name from Roberto Cobaria, that which was placed on him by the Catholics, to Berito KuwarU’wa KuwarU’wa, the name used by his people.

The leaders significance as an influential elder statesmen for Colombia’s Indigenous Peoples has not gone unremarked. “Berito taught Colombia’s indigenous people and the world the importance of the globalization of resistance, how to defend the beloved Earth and how to fight against climate change.” said Luis Fernando Arias, the Chief Councilor of the National Indigenous Organization of Colombia (ONIC).

“Internationally, Berito is the most well-recognized face of the U’wa struggle.” said Andrew Miller, who accompanied the U’wa leader with Amazon Watch to meet Avatar director James Cameron in his Los Angeles living room. “Especially in the late 1990’s, Berito was a global ambassador of the U’wa’s beautifully poetic cosmology that captured many people’s imaginations. He struck up a bond with Terry Freitas, the young activist who helped galvanize the international movement in support of the U’wa, as well as people like Atossa Soltani, Amazon Watch’s founder.”

Terence Freitas was the co-creator and coordinator of the U’wa Defense Working Group that was essential in drumming up international support for the U’wa. The young activist transformed his bedroom at his mother’s house into the de-facto HQ for the U’wa’s international campaign against Occidental Petroleum in the late 1990’s. Even his mother was unaware of the extent of her son’s involvement until one morning she found Berito, the leader of 7,000 indigenous people from the isolated paramos and cloud forests of eastern Colombia, sleeping on the living room floor of her suburban Los Angeles home.

“I noticed that he immediately bonded with Roberto, there was a link between them,” said Francois Mazure from the EarthWays Foundation that hosted Berito during his visit to Los Angeles. “Roberto was the father and Terry was the son.”

In 1997, after meeting with the directors of Occidental Petroleum in Los Angeles, Berito was kidnapped on his return to Colombia by gunmen who tried to force him to sign a drilling agreement. He refused and they beat him. In 1998, Freitas accompanied Berito to Al Gore’s office to meet the environmentalist vice president after the U’wa leader was awarded the Goldman Environmental Prize. Unfortunately Al Gore, whose father sat on the board of Occidental Petroleum and owned a small fortune in the company’s shares, never pressured Oxy publicly.

A year later Berito invited Freitas and two native American activists, Lahe’enda’e Gay and Ingrid Washinawatok, to help set up schools to protect the U’wa language and culture and defend their way of life from the oil industry. Washinawatok was a world-renowned 41-year-old indigenous activist known as Flying Eagle Woman of the Menominee Nation of Wisconsin and a rising leader in the struggle for indigenous rights. She also directed the Fund for the Four Directions, which promoted the revitalization of indigenous languages and cultures. Lahe’ena’e Gay was a 39-year-old member of Hawaii’s Kanaka Maoli Nation, as well as the founder and director of the Pacific Cultural Conservancy International, which works to preserve cultural and biological diversity.

Freitas knew the risks. On a trip to U’wa territory a year earlier he reported being observed and followed on various occasions by individuals he believed were paramilitaries. During that same trip he was stopped by the Colombian military and forced to sign a declaration that absolved the army of any responsibility for his security. He interpreted the act as a threat. The shared vision of Berito, Freitas, Gay and Washinawatok to develop schools to teach the next generation of U’wa children a non-colonial curriculum; alongside lessons on Natural Law, which was set down by the divine spirit Sira entrusting the U’wa with the guardianship of Mother Earth, outweighed the risks.

As Berito guided the three activists on their way to the airport to leave Colombia, they were kidnapped by masked gunmen. While the U’wa leader was immediately released, the bodies of the activists were found a week later bound and blindfolded with multiple gunshot wounds in a Venezuelan cow field over the Arauca river.

Because the FARC was then in preliminary peace talks in the late 1990’s, presaging more recent events, the guerrilla group appeared to have little to gain and much to lose from the kidnapping and executions. Indeed, the FARC high command was quick to deny complicity, in order to protect those fragile peace talks.

The armed men at the road block where the group were kidnapped also did not fit the profile of the local FARC – they were allegedly much younger, not dressed in fatigues, and had their faces covered – leading some to wonder if they were a rogue group opposed to the peace accords. The stretch of highway through Arauca province where the group had been traveling was dominated by the paramilitaries, who at the time had been waging a campaign of extermination against trade union leaders, human rights activists and suspected guerrilla collaborators. Eventually, however, a rebel commander from the guerrillas acknowledged: “Commander Gildardo of the FARC’s 10th Front found that strangers had entered the U’wa Indian region and did not have authorization from the guerrillas. He improvised an investigation, captured and executed them without consulting his superiors.”

Washinawatok’s Menominee Nation and various other U.S. indigenous rights groups accused the U.S. State Department of destabilizing their own negotiations with the FARC for the release of the activists, which they had believed would be imminent. During the failed peace talks of the 1990’s, the US State Department had released $230 million in military aid to the Colombian army, and fighting in the north between the army and their right wing paramilitary allies against the FARC had left 70 people dead on both sides.

Meanwhile, Occidental Petroleum wasn’t just spending millions to lobby the U.S. government to increase military aid to Colombia – it was providing direct financial and logistical support to the Colombian military. The oil giant was also funding private security firms like Air-Scan, which carried out the cluster-bombing massacre of Santo Domingo on Occidental’s behalf, as well as the paramilitary death squads involved in kidnapping, torture, extrajudicial killings and massacres of civilians across the region.

Most surprisingly, however, was the U.S. multinationals’ links with Colombia’s marxist guerrillas, confirmed when Oxy Vice-President Lawrence Meriage gave testimony before the U.S. House of Representatives in 2000. He admitted that Occidental employees regularly made payments to members of the FARC and ELN. Meriage’s acknowledgement of Oxy’s work relationship with the guerillas came three years after the ELN and FARC were declared “Foreign Terrorist Organizations” in 1997, making it a crime to provide material support to these groups.

Meriage’s testimony was also consistent with the actions and admissions by long-time Occidental leader Armand Hammer, who reports in his biography how Occidental’s Latin American security chief, former FBI employee James Sutton, was fired when he spoke out against the company’s payments to the ELN. “We are giving jobs to the guerrillas…” Hammer told the Wall Street Journal in 1985 “…and they in turn protect us from other guerrillas.”

An investigation by the LA Times found that Occidental Petroleum was funneling millions of dollars to the ELN guerillas as well as jobs and food for their members. “The rebels used the money to gain new recruits and weaponry,” the LA times stated, claiming the ELN were on the verge of being wiped out by the Colombian military in the early 80’s before receiving Oxy’s financial backing. “In effect, Occidental rescued the group that later turned against it.”

After his passing, Freita’s former girlfriend lashed out at Oxy in a letter to Vice President Al Gore, referring to the company’s friendly links with the guerrillas. Berito later testified to Amnesty International and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights to complain about the incident that took the life of three of the U’wa People’s greatest friends and allies. An article in the LA Weekly eulogizing the young activist after his death stated: “In May 1997, Freitas met the man who would change the course of his life: U’wa leader Roberto Cobaria.” Terry Freitas was 24 years old when he was executed.

The international campaign against Occidental Petroleum soon hit critical-mass. With many still reeling over the death of the three activists, protests against the oil giant were launched in London, Hamburg, Lima, Nairobi and several cities across the United States. The U’wa leader Berito Cobaria once again traveled from the cloud forests of eastern Colombia to the west coast of California where he planned to challenge Oxy CEO Ray Irani at the company’s annual shareholder meeting. Meanwhile as Occidental Petroleum funded all sides of Colombia’s brutal civil war, the flow of hundreds of millions of dollars of crude oil to the Caribbean coast continued.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 10, 2016 | Agriculture, Colonialism & Conquest

By Mary Louisa Cappelli, PhD, JD / Globalmother.org

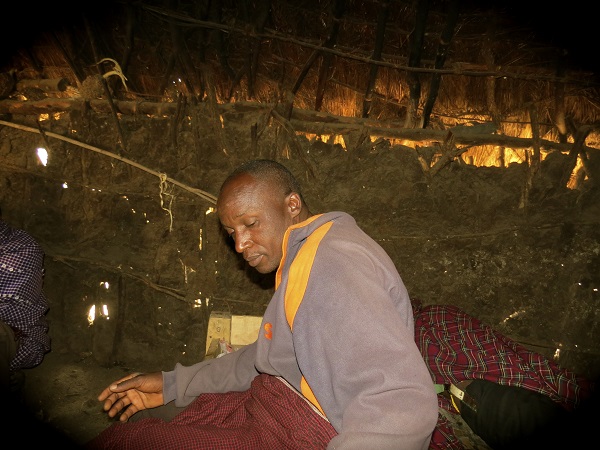

Featured image: Barabaig pastoralist

Katesh — After a fifty-year struggle against land grabbing by foreign agribusiness corporations, nomadic pastoralists in the Hanang District of Eastern Tanzania have finally won Certificates of Customary Right of Occupancy pursuant to the 1999 Land Act No. 5. With legal assistance from The Ujamaa Community Resource Team, The Barabaig and Masai in the villages of Mureru, Mogitu, Dirma, Gehandu and Miyng’enyi now have much needed access to approximately 5,500 hectares of grazing land for their cattle.

While several villages have benefited from the decision to enforce the 1990 Land Act No. 5, the Barabaig of the Basuto Plains have not been recognized in the latest issuance of Certificates of Customary Right of Occupancy. The Barabaig have been engaged in a fifty-year struggle to maintain their cultural integrity against the jurisprudent land policies of privatization and villagization, which have systematically suspended their constitutional rights and legal protections. The powerful infiltration of neoliberal forces culminating in land and resource grabbing has fashioned a geographical landscape of displaced indigenous peoples struggling to restructure their lives in uninhabitable terrain that supports relatively few life forms. While recording mythohistories amongst the Barabaig women, I have had the opportunity to witness first hand how the Barabaig have resisted globalizing forces that have pushed them to the farthest regions of the Basuto Plains.

Barabaig drinking from what remains of sole water source

Land Policy

The restructuring of socio-geographic areas in the interest of globalization has been most visible in the legal system in regards to land policy jurisprudence and administration, demonstrating how global discourse circulates in such a powerful system as to suspend constitutional rights and protections of the Barabaig Peoples. For many years, first President of the United Mwalimu Julius K. Nyerere’s philosophy on land holdings has shaped Tanzanian land policy. Rejecting the commoditization of land, Nyerere believed land was God’s gift to humanity and therefore could not be privatized. In his discussion of land holdings, he argues:

This land is not mine, but the efforts made by me in clearing that land enable me to lay claim of ownership over the cleared piece of ground. But it is not really the land itself that belongs to me but only the cleared ground, which will remain mine as long as I continue to work on it. By clearing that ground I have actually added to its value and have enabled it to be used to satisfy a human need. Whoever then takes this piece of ground must pay me for adding value to it through clearing it by my own labour. (Nyerere 1966)

This philosophy treats land as a fundamental right of human needs and not as commodity. This sentiment is further expressed in “The Nyerere Doctrine of Land Value” in the case of Attorney- General v. Lohay Akonaay and Another (Sabine 1964). [i] Accordingly, it is the public who possess land rights and an individual has a right to occupancy to use the common land belonging to the public. The duration of the Right to Occupancy can last from anywhere between 33 to 99 years depending on location and usage. The 1923 Land Ordinance of 1923 to 1999 referred to this title as a Deemed Right of Occupancy, based on occupation to confer ownership. “The majority of the people living in the rural areas—and who form more that 80% of the population of Tanzania hold their land under this system” (Peter 2007).

Today, President John Magufuli is the trustee of Tanzanian public lands and it is Magufuli who has the power and authority to decide what is in the public’s interest in terms of land decisions. Magufuli holds the power to “repossess land on behalf of the public for construction of roads, schools, hospitals etc.” (Peter 2007). Land can and has been taken from indigenous peoples without compensation for the land. In return the occupier is compensated for unexhausted improvements to the land, including houses, structures, crops; however, the occupier is not compensated for the land itself.

Legal Decisions Support Agribusiness Ventures

The implementation of the commoditization of land and resources can be seen in the 1960 decision to cultivate wheat in the Arusha Region of Hanang District. The United Republic of Tanzania along with the Canadian Food Aid Programme launched the Basotu Wheat Complex securing ten thousand acres of Barabaig land for wheat farming. In 1970, the National Agriculture and Food Corporation (NAFCO) expanded the project developing several large scale wheat farms securing 120,000 hectares of Barabaig pasture land, including homesteads, water sources, sacred burial grounds, and wild life.

Sadly, many Barabaig were unaware of the legal maneuvering for their land and first found out about it when tractors ploughed through their homesteads. According to reports and interviews, NAFCO failed to give due process to people living on their land at the time and were deemed to be trespassers on their own property. Chief Daniel recalls how he was jostled from sleep and ordered to leave. “We were forced off our own land by gunpoint,” he said.

A girgwagedgademga (council of women) with Chief Daniel

In the 1981 Case of National Agricultural and Food Corporation v. Mulbadaw Village Council and Others, the Barabaig sought legal protection and sued the National Agricultural and Food Corporation (NAFCO) for trespass on their land at the High Court of Tanzania in Arusha. While the High Court of Tanzania (D`Souza, Ag. J.) ruled in favor of the Barabaig Plaintiffs, stating that the Barabaig occupied land under customary title, the Court of Appeal of Tanzania overturned the decision and ruled in favor of NAFCO stating that, “The Plaintiffs/Respondents – Mulbadaw Village Council did not own the land in dispute or part of it because they did not produce any evidence to the effect of any allocation of the said land in dispute by the District Development Council as required by the Villages and Ujamaa Villages Act of 1975” (Peter 2007). In effect, the Village Council had trespassed by entering their own traditional lands, the Court of Appeals ruling that the villagers failed to meet the burden of proof that they were natives within the meaning of the law.

Legal analysis of case precedence is evidence that the Tanzanian government discounted Barabaig collective customary rights, discounted Barabaig tripartite land holding practices, ignored detrimental ecological effects derived from alienation of pastoral lands, and moreover privileged the privatization and commodification of land and foreign and national interests over local indigenous rights. Political power backed by powerful interest groups proved in this case study that power is not the same as law and that in the world of nation-states, placelessness and dispossession is a political byproduct of globalization.

In 1987, Tanzania, submitting to pressure to follow “global norms of behaviour,” decreed the Extinction of Customary Land Right Order. This extinguished land occupation under customary law, precluding Barabaig from exercising customary land rights protection (Larson and Aminzade 2009). Subsequently, when the Barabaig migrated during dry seasons, they left their lands with little evidence of occupancy, resulting in encroachment by external forces. The government began the process of Villagization, whereby the Barabaig were given portions of unused land deemed unsuitable for commercial purposes with little water resources. The Barabaig were subsequently settled (land-locked) in villages. The Villagization of the Barabaig drastically interfered with customary land practices, nomadic land use patterns, and livestock herding traditions.

According to Shivjii Chairman of the Presidential Commission of Enquiry into Land Matters, the movement of people into villages was achieved with “little regard to existing land tenure systems and the culture and custom in which they are rooted” (2007). The Barabaig surrendered their traditional migratory herding strategies and were forced to graze their cattle in a migratory cycle marked by a restricted one-day distance from their homestead. The concentration of livestock on this pattern of limited grazing has adversely impacted its ecosystems resulting in a “decline of levels of pastoral production and welfare” (Peter 2007).

Mama Paulina and widow

The Land Tenure reform is based on the premise that indigenous land tenure systems act as an obstruction to development and that more formal registered land title will encourage rural land users to make investments to improve their land investments through the provision of credit. The Tanzanian administrative structure grants each village a statutory title to land and further argues that granting titles and providing credit for land improvements will thwart encroachment by external forces; however, under the Customary Land Ordinance this has led to the holding of double titles leading to further complications of legality of ownership. The Barabaig case provides contrary evidence demonstrating that both objectives have failed to ward off encroachment by outsiders to enclose land for crop cultivation.

In addition, Land Use Appropriation by Foreign interests have interfered with traditional migratory patterns to water sources, denying Barabaig access to water during the dry seasons. Traditionally, Barabaig herders migrated eastward out of the village in the dry season to gain access to permanent water sources on the shores of Lake Balangda Lelu. The land allocation plans fail to recognize the indigenous needs of water sources; moreover, these allocations do not take into account the complexity of the traditional land use patterns in and beyond village boundaries. Because the Barabaig follow an animistic belief system that recognizes the interdependency and reverence of all life forms, displacement from their land and ancestral gravesites disrupts their sacred patterns of worship and traditional ways of being and living in the world.

The Barabaig were unaware of the Land Use Planning Provisions at the time and hence did not object to them because they did not realize how it would limit their migratory grazing patterns and obstruct their traditional livelihoods. According to Barabaig Chief Leader Daniel, plans were purposefully “ambiguous” and unclear with little account taken of their pastoral economy. Facing starvation, many pastoralists experienced a sense of cultural, spiritual and economic placelessness, and have been forced to give up their livelihood and migrate to squatter settlement areas in Arusha or Dar es Salam. “They fill the perio-urban shanties to eke out a living as best they can in the informal economy or become burdens of the state as the industrial and commercial sectors have no capacity to absorb more workers” (Lane 1990).

The issuance of Certificates of Customary Right of Occupancy provides a temporary legal tourniquet against the inhumane assault on indigenous livelihoods. According to Attorney Edward Ole Lekaita from The Ujamaa Community Resource Team in the Arusha District, efforts have begun once again to take up the legal gamut to secure customary title deeds for the Barabaig of the Basuto plains.

About the author: An interdisciplinary ethnographer, Mary Louisa Cappelli is a graduate of USC, UCLA, and Loyola Law School whose research focuses on how indigenous peoples of the global South struggle to hold onto their cultural traditions and ways of life amidst encroaching capital and globalizing forces. She previously taught in the Interdisciplinary Program at Emerson College and is the director of Globalmother.org, a Tanzanian WNGO, which engages in participatory action research and legislative advocacy in Africa and Central America.

References:

Aminzade, R. and Larson, E. “Nation-building in post-colonial nation-states: the cases of Tanzania and Fiji.” International Social Science Journal Vl. 59: (2009):1468-2451.

Lane, R. Charles. “Barabaig Natural Resource Management: Sustainable Land use under Threat of Destruction.” United Nations Research Institute for Social Development Discussion. Discussion Paper (1990): No 12.

Nyerere, J. K. Freedom and Unity: A Selection from Writings and Speeches

1952-1965. London: Oxford University Press, 1966.

Peter, Maina, Chris. “Human Rights of Indigenous Minorities in Tanzania and the Court of Law.” Journal of Group and Minority Rights, 2007.

Sabine, G. H. A History of Political Theory, London: George G. Harrap & Co. Ltd, (1964): 527-528.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jun 27, 2013 | Agriculture, Building Alternatives

By Cherine Akkari / Deep Green Resistance

Over the past few decades, our food system has become increasingly globalized [10]. With the rise of agribusiness, the ability to transport food cheaply over long distances and the development of food preservation techniques have enabled the distance between farm and market to increase dramatically.

Recently, such practices have been questioned for the damage they cause to the natural environment, their high energy consumption, and their contribution to climate change. In addition, the quality of the food available to residents is subject to increasing concern.

In fact, the trend toward increasing distances between producers and consumers has prompted many to question the environmental and social sustainability of our food choices [10]. The question of how to feed the urban population, particularly during crisis, is becoming urgent every day. Concerns about health and the loss of tradition and culture that began to take hold in post-modern society, the spread of the ‘food desert’, especially in poor urban areas [4], where there is no easy access to affordable food, food banks and soup kitchens, demonstrated that the urgency of access to food and food security for everyone must be confronted.

To note here, the modern movement for LFS (local food systems) as an alternative to the conventional agricultural system is not new. It started in Japan in the 1970s with the teikei, which means ‘putting the producer’s face on the product’ [10]. The teikei were organized around consumer cooperatives, whose members would link up with producers and even helped with the work on the farm [13]. A similar model was also adopted in Québec by Équiterre in 1995 where consumers, organized into groups, pay up front at the beginning of the season and receive deliveries of food baskets each week, thereby sharing the risk inherent in agricultural production [1].

Agriculture is a major driver of human-caused climate change, contributing an estimated 25 to 30% of global greenhouse gas emissions. However, when done sustainably it can be an important key to mitigating climate change [12]. The sustainable use of agricultural biodiversity is likely to be particularly beneficial for small-scale farmers, who need to optimize the limited resources that are available to them and for whom the access to external inputs is lacking due to financial or infrastructural constraints [19].

Benefits on a large-scale can also be achieved by focusing on improvements relevant to large commercial farmers and conservation agriculture has already been effective in this respect. Inevitably, there is considerable skepticism over the practicality of the widespread adoption of agricultural production practices that embody a greater use of biodiversity for food and agriculture and a greater emphasis on ecosystem functions [19].

Two major geopolitical realities have a constraining effect on peoples’ thinking. Firstly, modern, intensive farming in developed countries receives very large levels of financial support and all sectors of the agricultural and food industries are linked to this highly subsidized system. Secondly, there is a continuing commitment to ensuring that food prices remain low and that basic foodstuffs are affordable by all sectors of society including the poorest. These both tend to lead to a disinterest in the nature of agricultural production systems and present a very real barrier to the development of new approaches to production [19]. However, it is increasingly recognized that an appropriate policy framework can largely overcome these constraints and, indeed, must be developed .

In the last few years, more localized food supply chains have been proposed as a vehicle for sustainable development [5]; [6]; [9]; [15] and [21]. We can note here that the term ‘local’ is still contested and its definition varies from one local market development organization to the next. Literally, the term ‘local’ indicates a relation to a particular place, a geographic entity.

However, as our literature review has uncovered, most organizations have a more elaborate definition of what is local, often incorporating specific goals and objectives that an LFS ought to deliver into the definition itself.

There are three aspects of LFS, which are proximity (geographic distance, temporal distance, political and administrative boundaries, bio-regions, and social distance), objectives of local food systems (economic, environmental and social objectives), and distribution mechanisms in local food systems (farm shops, farmer’s markets, box schemes, community-supported agriculture, institutional procurement policy, and urban agriculture).

Besides the non-governmental organizations (NGOs), there is a growing interest by the public sector for local food, which is mainly linked to the idea of food sovereignty – a global movement that aims to transform food systems into engines of sustainable development and social justice. To note here is La Via Campesina [21], which was the first organization to develop the concept of food sovereignty in 1993 in Belgium [13].

Thus, the pursuit of food sovereignty implies that work should be done in international treaty negotiations and human rights conventions in order to allow state sovereignty over food policy—that is, to prevent interference from foreign powers in the policy-making process, lift restrictions placed by international trade agreements, and eliminate dumping practices [1].

In 2007 in Montreal, a definition of food sovereignty was developed by a Québec-based coalition for food sovereignty that included producer organizations, civil society groups, food distributors, and development organizations. The definition states that “food sovereignty means the right of people to develop their own food and agricultural policy; to protect and regulate national food production and trade in order to attain sustainable development goals, to determine their degree of food autonomy, and to eliminate dumping on their markets. Food sovereignty does not contradict trade in the sense that it is subordinated to the right of people to local food production, healthy and ecological, realized in equitable conditions that respect the right of every partner to decent working conditions and incomes” [1].

Over the last 60 years, Canada‘s overall food system has become more geared to large-scale systems of production, distribution and retail. In Quebec, the agricultural, food processing, and retail sectors account for 6.8% of GDP and 12.5% of all jobs. The province produces fresh and processed food worth $19.2 billion, while only consuming $15.4 billion (a 25% surplus), and retailers imported $6.9 billion worth of fresh and processed foods last year. About 44% of Quebec’s raw and processed food production finds its way into Quebeckers’ plates, the rest being exported to other Canadian provinces (30%) and overseas (245) [20].

We can note here that since 1941, the evolution of Quebec’s agricultural landscape is characterized by the decrease in the number of farms and a market concentration dominated by few producers. And this is very similar to what we see in other Canadian provinces and other industrialized countries [8].

As it was already mentioned in this report, local food systems are proliferating in Quebec [8]. There is now a growing interest in the production, processing, and buying of local food. New “local food systems” are being set up to organize the various components that will meet the needs of all the stakeholders in the community or region [7].

The initiatives that are helping in this process in Quebec are: organic and other specialized agriculture ((316 certified organic livestock production units, 341 organic maple syrup producers, and 585 certified farms [18]), farmer’s markets (network of 82 open markets, seasonal or permanent, daily or occasional), community- supported agriculture (CSA) and solidarity markets (a new phenomenon, solidarity markets allow consumers to order through a web portal) [8].

Despite the growth of these initiatives, there remain several obstacles inhibiting their expansion. The three main obstacles are: lack of financing (for example, banks are not willing to issue micro-loans at competitive rates), economic power (in fact, the food retail sector is marked by high rates of market concentration; supermarkets have been able to achieve economies of scale because they do not have to pay for the social and environmental costs of their business practices), and knowledge (the lack of demand for local food attributed to a lack of information about where to procure it, and a lack of information about prices).

Now, identifying every obstacle, policy and existing initiative related to the nodes in the value chain in the literature of [1], we notice there is a dilemma between land protection and land access. This is mostly attributed to the case of zoning policy.

In 1978, and in the context of rapid economic development, speculation on land, fragmentation of the land, and non-agricultural use, the government of Quebec passed agricultural land protection legislation, the second in Canada. This law reflected a desire to plan and regulate in this area and an overseeing agency was also created – the Commission de protection du territiore agricole du Quebec (CPTAQ). This law effectively organized the use of agricultural land over the years. However, today with greater concentration of ownership and fewer people in the business of food production, the zoning law is causing problems since it acts as barrier for entry for smaller and more value-added producers who need smaller plots [8].

In fact, the zoning law is one of the laws that facilitates industrial long-distance agriculture at the expense of small-scale sustainable agriculture and short supply chains (e.g. zoning laws that favor big farms, subsidy systems that favor big retailers, funding schemes targeted at large producers, and so on) [1]. At the same time, we can see this on an international level – the pressure for city expansion, speculation and non-agricultural use is still strong.

Moreover, beyond the provincial level, municipalities have authority over certain zoning laws and by-laws that can facilitate or inhibit the development of LFS, particularly regulations concerning the use of agricultural zones for commercial purposes [1]. Though aimed at protecting agricultural zones from industrial development and other forms of encroachment, such by-laws effectively prevent on-farm direct sales or the use of farmland for farmers’ markets or farm shops [17] and organizers of such initiatives typically have to negotiate with municipal authorities for special permits or designated spaces [3].

However, agricultural zoning per se (designations for tax purposes) falls within provincial government jurisdiction or a land management agency, such as the Agricultural Land Reserve in British Columbia or the Commission pour la protection des terres agricoles du Québec [1].

To conclude, to achieve this vision of food sovereignty, LFS have to go beyond the distance traveled by food products before they reach the final consumers (food miles) and integrate social, economic and environmental benefits. Also, Farmers’ markets, CSAs and other initiatives are becoming increasingly present in industrial countries in recent years, but they still only represent a very small part of the food market [1].

For example, in Quebec, Équiterre’s CSA went from 1 to 102 farms between 1995 and 2006. It contributes to 73% of the average turnover of the farms, and yields an average annual profit of $3,582 annually when conventional agricultural produces an average annual loss of $6,255 [2] . In addition, regarding the zoning law, there are some good possibilities.

In fact, within the existing law, new initiatives are emerging elsewhere and new possibilities can be developed in other provinces. These include cooperative land trusts and the collective buying of land and green belts [8]. However, other aspects require reform. CPTAQ should be more flexible to LFS needs.

For example, in one case, the CPTAQ has agreed to allow municipal authorities in Ste-Camille to take management over a large farm that was for sale in order to help new young families establish small farms. In order to do this, the CPTAQ de-zoned the land, thus technically empowering municipal authorities to develop it however they chose; however, there was an understanding that the municipality would keep the land for agricultural use.

If this case is inspiring, there should be a formal way to make such arrangements without necessarily de-zoning the land and placing it at risk. The main and remaining question is how to allow the creation of small farms without endangering land protection for the future of agriculture in Quebec, especially in the context of rising non-agricultural activities in farming areas (e.g. shale gas exploitation) [8]. Even though there is no national policy to promote LFS, provincial governments have been active with various programs in this area.

There is much variations from one provinces to another, but the existing programs tend to cluster on the demand side, focusing on consumer education and marketing projects, even running some themselves (the origin labeling and promotion programs). To a lesser extent, there are some programs to support organic farming (transition programs) but very few focusing on processing and distribution. Moreover, it is important to provide knowledge for policy action on food sovereignty given the gap which exists in understanding the impact of existing public policy initiatives [1].

Agriculture is a globally occurring activity which relates directly and powerfully to the present and future condition of environments, economies, and societies. While agriculture has provided for basic social and economic needs of people, it has also caused environmental degradation which has prompted a burgeoning interest in its sustainability [17].

Moreover, like the concept of ‘sustainable development’, the term ‘sustainable agriculture’ has been interpreted and applied in numerous ways. At the broadest level there is some consistency in definition [17]. Most analysts and practitioners would probably accept that sustainable agriculture has something to do with the use of resources to produce food and fiber in such a way that the natural resource base is not damaged, and that the basic needs of producers and consumers can be met over the long term [17].

Despite this, it seems that there is little agreement on the meaning of ‘sustainable agriculture’. There is a little agreement on the meaning of ‘agriculture’, let alone the stickiness of a word like ‘sustainable’ [17].

References:

[1] Blouin et al. (September, 2009). LOCAL FOOD SYSTEMS AND PUBLIC POLICY: A REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE. Équiterre &The Centre for Trade Policy and Law, Carleton University.

[2] Chinnakonda, D., and Telford, L. (2007). Les économies alimentaires locales et régionales au Canada: rapport sur la situation. Ottawa: Agriculture et Agroalimentaire Canada.

[3] Connell, D.J., Borsato, R., & Gareau, L.( 2007). Farmers, Farmers Markets, and Land Use Planning: Case Studies in Prince George and Quesnel. University of Northern British Columbia.

[4] Cummins, S. and Macintyre, S. (2002). Food Deserts – Evidence and Assumption in Health Policy Making.” British Medical Journal Vol. 325, No. 7361: 436-438.

[5] Desmarais, A. (2007). La Vía Campesina: Globalization and the Power of Peasants. Halifax, London, and Ann Arbor, Michigan: Fernwood Pub. Pluto Press.

[6] Halweil, B. & Worldwatch Institute. (2002). Home Grown: The Case for Local Food in a Global Market. Washington, D.C.: Worldwatch Institute.

[7] Irshard, H. (2009). Local Food – A Rural Opportunity. Government of Alberta. Agriculture and Rural Development. Retrieved from http://www1.agric.gov.ab.ca/$Department/deptdocs.nsf/all/csi13484/$FILE/Local-Food-A-Rural-Opp.pdf

[8] Lemay J-F. (2009). Local Food Systems and Public Policy: The Case of Zoning Laws in Quebec. Retrieved from

[9] Lyson, T.A. 2004. Civic Agriculture. UPNE. Available at:

[10] MacLeod, M., and Scott, J. (May, 2007). Local Food Procurement Policies:A Literature Review. Ecology Action Centre For the Nova Scotia Department of Energy. Retrieved from

[11 ] Mundler, P. (2007). Les Associations pour le maintien de l’agriculture paysanne (AMAP) en Rhône-Alpes, entre marché et solidarité. Ruralia 2007-20. Available at: http://ruralia.revues.org/document1702.html [Accessed July 15, 2009].

[12] Nierenberg, D., and Reynolds, L. (December 4, 2012). Supporting Climate-Friendly Food Production. WorldWatch Institute. Retrieved from http://www.worldwatch.org/supporting-climate-friendly-food-production

[13] Pimbert, M. (2008). Towards Food Sovereignty: Reclaiming Autonomous Food Systems. London: International Institute for Environment and Development.

[14] Pretty, J. (1998). The Living Land: Agriculture, Food, and Community Regeneration in Rural Europe. London: Earthscan.

[15] Rosset, P. & Land Research Action Network. (2006). Promised Land: Competing Visions of Agrarian Reform. Oakland, California & New York: Food First Books.

[16] Smit, B., and Smithers, J. (Autumn, 1993). Sustainable Agriculture: Interpretations, Analyses and Prospects. Department of Geography, and Land Evaluation Group,

University of Guelph. Canadian Journal of Regional Science/Revue canadienne des sciences régionales, XVI:3), 499-524. ISSN: 0705-4580

[17] Wormsbecker, C.L. (2007). Moving Towards the Local: The Barriers and Opportunities for Localizing Food Systems in Canada. Master of Environmental Studies in Environment and Resource Studies. University of Waterloo.

[18] CARTV, (2009). Statistiques pour l’appelation biologique. Retrieved from

[19] FAO. (2011). Biodiversity for Food and Agriculture: Contributing to food security and sustainability in a changing world. Platform for Agrobiodiversity Research (PAR). Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/biodiversity_paia/PAR-FAO-book_lr.pdf

[20] MAPAQ. (2009). Statistiques economiques de l’industrie bioalimentaire. Retrieved from http://mapaq.gouv.qc.ca/fr/md/statistiques/Pages/statistiques.aspx

[21] Vía Campesina. La Vía Campesina: International Peasant Movement—Small Scale Sustainable Farmers are Cooling Down the Earth. Available at: [Accessed June 13, 2009].

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 4, 2013 | People of Color & Anti-racism, White Supremacy

By Lorenzo Kom’boa Ervin / Memphis Black Autonomy Federation

To grasp what happened at the March 30, 2013 Klan demonstration, you need to understand what led up to everything. The Klan said it came to Memphis to protest the renaming of the racist Memphis Confederate Parks system. Of course, all police preparations and media reporting claimed that the cops “had” to create a downtown police security zone of 10-12 square blocks to “keep the peace”, and not repeat the so-called anti-Klan “riot” of 1998, which was blamed on protesters then, but actually was a police riot as a result of an order by then-Mayor Willie Herenton to gas and beat protesters because they were approaching the Klan through breaks in the police line.

So, using that mantra of “preventing a riot”, and also the media propaganda that this was a “new” Klan group, in response to critics who asked why the Klan was being allowed to protest at all, they put together a police army of 600 cops, 4 military armored cars with machine guns, a chain link fence to separate protesters from Klan, and confined the residents of Memphis behind a line of paramilitary riot police to “protect” the Klan from the people. Of course, the obvious reflection was that this happened over 15 years ago and that the anti-Klan protest movement was “new” as well, did not penetrate the prevailing myth circulated by the cops and the lapdog media.

Our movement, the Memphis Black Autonomy Federation, had created a broad-based group called the Ida B. Wells Coalition Against Racism and Police Brutality to bring out Memphis residents, but also anti-fascist activists from throughout the Southern and Midwestern regions. We tried at first to have a meeting at city hall, but this was refused by a groups of businessmen, then the city permit office refused a permit for the same area as the Klan, which was at the courthouse itself, just a few hours before. Then, the cops wanted to not allow any more than 100 people from the community come to the event, but we fought that, and they apparently allowed everyone to go in, including white supremacist supporters and anti-Klan activists. This latter decision was a recipe for disaster, we felt, and we did not initially feel that it would be safe to go inside. If someone got to fighting a Klan supporter, they could be shot and we all would have been in danger. We decided to press on anyway.

If we had not applied for the city parade permit, no one would have been allowed to protest at all, and we would not have even known of their security plans at all. Only because we kept prodding the city to back off on at least some of its security precautions, did they agree to allow the protest. They then issued the permit at the last minute, and the lapdog media dutifully reported it, including the city’s denial that it had ever denied our permits. This little media report would prove to be the undoing of the city’s plans for total denial of the event, and its plans of discouraging any protest through media saturation by the Mayor and government officials who time and again tried to frighten, scold, and intimidate people from coming down to an anti-Klan event. Just the fact that people knew that there was going to be a protest made them come down to the event, even if they were totally unfamiliar with our movement.

The day before the event we were concerned about being pushed into a “protest pit” as was done at many other events in other cities and was used to crush the anti-globalization movement, and because the original plan called for us all to be shoved into a small space on the side of the courthouse itself, we decided that it would be a threat to our security to go in that space, and we called for an activist General Assembly at a nearby park, which was outside the police protest zone, to discuss options. So about 150 of us met at Court Square park, and talked about going to the Forrest Park and attacking the statute itself, but then the cops came up and told us that we “had” to go to the “security zone”, and we feigned going there, but in fact we had prepared a number of signs saying “Cops Stifle Free Speech!” and about 150 of us marched down to police lines and protested the police state methods of controlling the protest.

The cops were perplexed, and a small number of them tried to chase us around or steer us into the barbed wire area, but we refused to go. It was a standoff, but they did not arrest anybody or beat us up. It was clear that they did not want to break their ranks to try to arrest all of us, so we took advantage of the moment and kept protesting. Then we moved towards the park, but there was a split between those who wanted to go inside the police lines, and those who did not. The group started splintering. After much soul searching, we decided we would go inside. So we headed for the entrance, and many followed us. The cops had everybody head through TSA style metal detectors, empty our pockets, and searched us. They seized all papers, pamphlets, protest signs, and denied you entry if you were wearing “radical” t-shirts of Che Guevara or Huey Newton, but also Jefferson Davis or N.B. Forrest attire. They seized our bullhorns, but returned one of them as we were entering the event.

When we got inside, everyone seemed subdued, and there was no chanting or screaming, everyone was just looking for signs of the Klan to show. The Klan was kept 2-3 football fields away from us, who were behind barbed wire. There was a long line of riot police inside arrayed as a gauntlet we had to pass, then there were police snipers on the roof, and a line of police standing across from us, about five deep and then others on horseback. They never moved for five hours, just stared ahead at us in military formation.

What made us feel good about going inside is that there was in fact a large number of people already inside waiting on us. They kept streaming in. These were not the usual white middle class activists or the old civil rights deadheads, these were working class Black people of every age. They were angry as hell because the Mayor had brought these “Ku Klux Kowards” to town, and had put us behind barbed wire and coddled the Klan. The Klan came on special city buses, only about 60 of them, which contained riot police and a special security wing of Memphis police and Shelby County Sheriffs.

Not only are the scale and speed of materials extraction, production, consumption and waste ballooning, but so too the scale and pace of the movement of materials through global trade. For instance, trade volumes in physical terms have increased by a factor of 2.5 over the past 30 years. In 2009, 2.3 billion tons of raw materials and products were traded around the globe.[9] Maritime traffic on the world’s oceans has increased four-fold over the past 20 years, causing more water, air and noise pollution on the open seas.[10]

Not only are the scale and speed of materials extraction, production, consumption and waste ballooning, but so too the scale and pace of the movement of materials through global trade. For instance, trade volumes in physical terms have increased by a factor of 2.5 over the past 30 years. In 2009, 2.3 billion tons of raw materials and products were traded around the globe.[9] Maritime traffic on the world’s oceans has increased four-fold over the past 20 years, causing more water, air and noise pollution on the open seas.[10] In India, chemical and physical pollution occasioned by the frenzied rush of industrial development has become so treacherous that it is deforming air and water into poisons to be avoided at the risk of health and life itself. Mephitic mountains of plastic waste choke every town and city, clog drains, suffocate rivers and shores, fill the stomachs of animals. Pesticides have killed soil and farmers alike across the country. Despite these and so many other manifestations of ecocide, industry and the government — central and state-level alike — clamor for more of it, faster. Because it is a ‘developing’ country, we are told, the average Indian vastly underconsumes plastic, energy, cars, et al. Cultural traditions of thrift and sharing, wherever they still hang on, are seen as nettlesome but surmountable barriers to keeping the growth machine growing, faster. Replacing each and every one of those traditional practices with packaged, often disposable, commodities is an explicit goal of industry. Relentlessly generating novel needs is another. The current government’s “Make In India” program, marketed to attract foreign investors and businesses, is the latest campaign to fuel this process.[13]

In India, chemical and physical pollution occasioned by the frenzied rush of industrial development has become so treacherous that it is deforming air and water into poisons to be avoided at the risk of health and life itself. Mephitic mountains of plastic waste choke every town and city, clog drains, suffocate rivers and shores, fill the stomachs of animals. Pesticides have killed soil and farmers alike across the country. Despite these and so many other manifestations of ecocide, industry and the government — central and state-level alike — clamor for more of it, faster. Because it is a ‘developing’ country, we are told, the average Indian vastly underconsumes plastic, energy, cars, et al. Cultural traditions of thrift and sharing, wherever they still hang on, are seen as nettlesome but surmountable barriers to keeping the growth machine growing, faster. Replacing each and every one of those traditional practices with packaged, often disposable, commodities is an explicit goal of industry. Relentlessly generating novel needs is another. The current government’s “Make In India” program, marketed to attract foreign investors and businesses, is the latest campaign to fuel this process.[13] There are also many sister concepts and movements to degrowth, that, despite their differences, share some basic, fundamental values and perspectives. There is Buen Vivir/Sumak Kawsay emerging out of indigenous, eco-centric Andean cosmovisions, calling not for alternative development but alternatives to development, for affirmation and strengthening of traditional practices, knowledge systems, processes and relationships (human and non-human alike) that since time immemorial have embodied many of the qualities that movements (like degrowth) in industrialized locales are striving to re-create.[16]

There are also many sister concepts and movements to degrowth, that, despite their differences, share some basic, fundamental values and perspectives. There is Buen Vivir/Sumak Kawsay emerging out of indigenous, eco-centric Andean cosmovisions, calling not for alternative development but alternatives to development, for affirmation and strengthening of traditional practices, knowledge systems, processes and relationships (human and non-human alike) that since time immemorial have embodied many of the qualities that movements (like degrowth) in industrialized locales are striving to re-create.[16]