by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 26, 2013 | Mining & Drilling

By Max Wilbert / Deep Green Resistance Great Basin

The first Tar Sands mine in the United States is an open wound on the landscape: a three acre pit, the bottom puddled with water and streaked with black tar. Berms of broken earth a hundred feet tall stand on all sides. To the north and south, Seep Ridge Road – a narrow, rutted, dirt affair – is in the midst of a state-funded transfiguration into a 4-lane paved highway that may soon be clogged with afternoon traffic jams of oil tankers and construction equipment. Clearcuts and churned soil stretch to either side of the road, marking the steady march of progress.

This is the Uintah Basin of eastern Utah – a rural county, known for providing the best remaining habitat in the state for Rocky Mountain Elk, White Tailed Deer, Black Bear, and Cougar. In the last decade, it’s become the biggest oil-extraction region on the state, and in the last five years fracking has exploded. There are over 10,000 well pads in the region. And now, the Tar Sands are coming.

Thirty two thousand acres of state lands situated on the southern rim of the basin – some 50 square miles – have been leased for Tar Sands extraction. If all goes according to plan, the mine at PR Springs that I’m looking at would produce 2,000 barrels of oil per day by late this year, with planned increases to 50,000 barrels per day in the future.

Dozens of similar mines are planned across the whole region. Along with their friends in state and local governments, energy corporations are collaborating to turn this region into an energy colony – a sacrifice zone to the gods of progress, growth, and desecration.

Twelve to 19 billion barrels of recoverable tar sands oil is estimated to be located under the rocky bluffs of eastern Utah, mostly in the southern portion of Uintah County. It’s a drop in the bucket for global production, but it means total biotic cleansing for this land.

Crude oil, tar sands, oil shale, and fracking: these are the wages of a dying way of life, and the ozone pollution that is already reaching record levels in this remote, sparsely-populated region is evidence of the moral bankruptcy of this path. There is no claim to morality in this path. It leads only to death, for us and for all life.

Alongside the test pit and scattered throughout the landscape, drill pads for seismologic assessment and roads to the pads have already been cut through the forests and shrubs, leaving behind a patchwork of shattered sagebrush and mangled juniper – testament to the Earth-crushing consequences of this “development”.

Situated at 8,000 feet of elevation, this wild region is called the Tavaputs Plateau. Unmarked, often muddy dirt roads make travel dangerous, and deep valleys plunge thousands of feet to the rivers that drain the region – the White River to the north, and the Green to the west. Both flow into the Colorado River, which provides drinking water for more than 11 million people downstream.

Resistance to tar sands and oil shale projects in Utah dates at least back to the 1980’s, when David Brower and other alienated conservationists fought off the first round of energy projects in this region. Thirty years later, the fight is on again.

It is likely that the PR Springs mine will be the bellwether of Tar Sands mining in the United States. If the project is stopped, it will be a major blow to the hopes of the Tar Sands industry in this country, while if it goes ahead smoothly, it may open the floodgates for more projects in Utah, Colorado, and Wyoming.

That is why resistance to this project is so important. That resistance is building. Strong organizations based in Moab (Before it Starts and Living Rivers) and Salt Lake City (Utah Tar Sands Resistance and Peaceful Uprising) are working together to organize against the project, and individuals and allies have been scouting the site and preparing to take action this summer.

Campouts at PR Springs will take place in May and June with more gatherings likely throughout the summer. An action camp will take place the fourth week of July, with activists and concerned people from across the country gathering to support one another, prepare for action, and make plans. All are welcome.

Time is short. There is no time to waste, and we are few. If we are to succeed, we will need your help, your solidarity.

Looking out across a landscape that might soon be a wasteland, my gaze wanders across the juniper, scrub oak, and sagebrush that wrap gently over the hillsides and drop into the valleys. The setting sun casts waning light on the treetops, and a small herd of Elk climbs a ridge in the distance and disappears into the brush. Overhead, the few clouds in the broad sky fade from red to deep purple, then to darkness.

The last birds of the day sing their goodnight songs, and the stars begin to appear, thousands of them, lighting up the night sky and casting a dull glow across the countryside. I take a deep breath, tasting the cool night air spiced with the scents of the land.

The bats are out, flitting about snatching tasty morsels out of midair. I can hear their voices. They are calling to me. Tiny voices carrying across miles to whisper in your ear like the tickle of a warm breeze. “Fight back,” they say. “Please, fight back. This is our home. We need you to do what it takes to stop this. Whatever it takes to stop this. Whatever it takes.”

Whatever it takes.

_____________________________________________________

Companies involved in Tar Sands projects in the Utah include Red Leaf Resources (which also works in the Oil Shale business and is based in Salt Lake City), MCW Energy Group, Crown Asphalt Ridge LLC, and U.S. Oil Sands, a Calgary, Alberta based company.

Red Leaf Resources is currently working on a shale oil operation in the same region as the PR Springs mine, which could eventually produce 10,000 barrels of oil per day. Other large oil shale operations are planned for region by the Estonian company Enefit.

You can learn more about the resistance to Utah Tar Sands projects at the following websites:

http://www.tarsandsresist.org/

http://www.peacefuluprising.org/topic/current-campaigns/stop-tar-sands

Max Wilbert is a writer and community organizer living in occupied Goshute territory otherwise known as Salt Lake City, UT. He originally hails for occupied Duwamish territory known as Seattle, and organizes primarily with the Great Basin Chapter of Deep Green Resistance to fight injustice and promote strategies towards the dismantling of industrial civilization.

You can contact Max Wilbert at greatbasin@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | May 3, 2012 | Obstruction & Occupation

By Steve Lyttle / Charlotte Observer

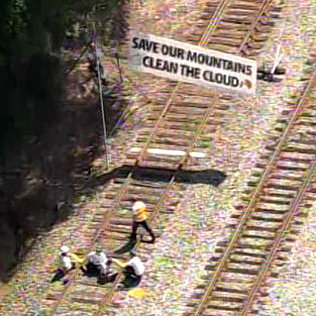

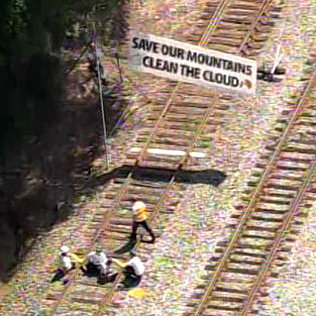

Six people were arrested Thursday morning in Catawba County after a group of protesters from Greenpeace and three other organizations blocked a train from entering Duke Energy’s steam-powered plant in Catawba County by chaining themselves to the tracks.

The group aimed the protest at Duke Energy, for its use of coal-powered plants, and at technology giant Apple. Leaders of the action said they are protesting Apple because it is using Duke Energy power for the expansion of its data center at Maiden in Catawba County.

“The group was able to stop the train from passing by,” said Molly Dorozenski, a Greenpeace spokesperson.

The Catawba County Sheriff’s Office confirmed that arrests were made. According to reports from the scene, four people who had chained themselves to the tracks were taken into custody, along with two others at the scene.

The action came at the same time as Greenpeace demonstrators were outside Duke Energy’s corporate headquarters in Charlotte’s uptown, protesting during the company’s shareholders meeting.

Dorozenski said the incident began Thursday morning when a train carrying coal arrived at the Marshall Steam Station. She said four activists chained themselves to the tracks, to prevent the train from delivering coal. She said other protesters put the Apple logo on train cars, to show the group’s belief that Apple is profiting by Duke Energy’s use of coal.

Greenpeace contends the use of coal is creating an environmental hazard, and that coal mining is damaging to the ecology of the Appalachia region.

Joining Greenpeace in blocking the train were members of Radical Action for Mountain People’s Survival (RAMPS), Katuah Earth First! and Keepers of the Mountains Foundation, according to Greenpeace.

“Duke is using data center expansion in North Carolina, like Apple’s, to justify reinvesting in old coal-fired power plants and even worse — as an excuse to build new coal and nuclear plants,” said Gabe Wisnieweski, Greenpeace’s USA Coal Campaign director.

“The climate and communities throughout Appalachia and North Carolina are paying the price for Apple and Duke’s short-sighted decisions,” he added.

Read more from The Charlotte Observer:

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 18, 2012 | Climate Change

By Fiona Harvey / The Guardian

Britons’ consumption of goods such as TVs and mobile phones made in China has “outsourced” the UK’s greenhouse-gas emissions, and is leading to a net increase in global emissions, according to a report from an influential committee of MPs.

While the UK’s own greenhouse-gas emissions have been tumbling, people and businesses have been buying an increasing proportion of manufactured products from overseas, where regulations on carbon emissions are often much weaker than within the EU. As a result, the increase in carbon emissions from goods produced overseas that are then used in Britain are now outstripping the gains made in cutting emissions here.

Tim Yeo, chairman of the energy and climate change committee, said: “Successive governments have claimed to be cutting climate-changing emissions, but in fact a lot of pollution has simply been outsourced overseas. We get through more consumer goods than ever before in the UK, and this is pushing up emissions in manufacturing countries like China.”

However, while China has become the world’s biggest producer of greenhouse-gas emissions, it has also become the world’s second biggest economy on the back of the enormous exports from its vast manufacturing sector. This means that, in effect, consumers from developed countries have paid China to take on responsibility for more greenhouse-gas emissions.

The Chinese government is reluctant to deal with the problem, insisting that China is taking on voluntary emissions-reduction targets, but is resistant to moves that would force Chinese manufacturers to obey stricter emissions limits.

This can put developed-world manufacturers at a disadvantage, which encourages the production of goods in areas with lax carbon controls, and thus pushes up emissions globally. Simon Harrison, chair of energy policy at the Institution of Engineering and Technology, said: “It’s about how you price imported goods – do you take account of the emissions involved in their production?”

When goods are manufactured in the UK and other European countries, the companies that make them are subject to strict emissions controls. For instance, they have to pay for the carbon they produce, and pay a surcharge on energy to subsidise renewable forms of generation. But overseas exporters in countries such as China and India are not subject to such stringent regulation, and often their manufacturing processes and energy generation are more carbon-intensive than the same processes here.

The government is in a quandary over what to do about the situation. Though importing carbon-intensive goods from overseas helps the UK to cut its overall emissions, it does not help to cut emissions globally, but just shifts the problem elsewhere. However, to slap import tariffs on goods from overseas that are produced in a carbon-intensive manner – which some UK manufacturers have said they would welcome – would be difficult under the World Trade Organisation’s rules.

Some green campaigners are urging the government to take responsibility for the emissions produced in the manufacture of imported goods. Andrew Pendleton, head of campaigns at Friends of the Earth, said: “One of the main reasons why nations such as China have soaring carbon emissions is because they are making goods to sell to rich western countries. This report highlights the UK’s role in creating this pollution. The government can’t continue to turn a blind eye to the damaging impact that our hunger for overseas products has on our climate. We need to tackle the problem, not shift it abroad.”

Read more from The Guardian: http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2012/apr/18/britain-outsourcing-carbon-emissions-china

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 9, 2012 | Mining & Drilling

By Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Wind turbines, one of the fastest-growing sources of emissions-free electricity, rely on magnets that use the rare earth element neodymium. And the element dysprosium is an essential ingredient in some electric vehicles’ motors. The supply of both elements — currently imported almost exclusively from China — could face significant shortages in coming years, the research found.

The study, led by a team of researchers at MIT’s Materials Systems Laboratory — postdoc Elisa Alonso PhD ’10, research scientist Richard Roth PhD ’92, senior research scientist Frank R. Field PhD ’85 and principal research scientist Randolph Kirchain PhD ’99 — has been published online in the journal Environmental Science & Technology, and will appear in print in a forthcoming issue. Three researchers from Ford Motor Company are co-authors.

The study looked at 10 so-called “rare earth metals,” a group of 17 elements that have similar properties and which — despite their name — are not particularly rare at all. All 10 elements studied have some uses in high-tech equipment, in many cases in technology related to low-carbon energy. Of those 10, two are likely to face serious supply challenges in the coming years.

The biggest challenge is likely to be for dysprosium: Demand could increase by 2,600 percent over the next 25 years, according to the study. Neodymium demand could increase by as much as 700 percent. Both materials have exceptional magnetic properties that make them especially well-suited to use in highly efficient, lightweight motors and batteries.

A single large wind turbine (rated at about 3.5 megawatts) typically contains 600 kilograms, or about 1,300 pounds, of rare earth metals. A conventional car uses a little more than one pound of rare earth materials — mostly in small motors, such as those that run the windshield wipers — but an electric car might use nearly 10 times as much of the material in its lightweight batteries and motors.

Currently, China produces 98 percent of the world’s rare earth metals, making those metals “the most geographically concentrated of any commercial-scale resource,” Kirchain says.

Historically, production of these metals has increased by only a few percent each year, with the greatest spurts reaching about 12 percent annually. But much higher increases in production will be needed to meet the expected new demand, the study shows.

China has about 50 percent of known reserves of rare earth metals; the United States also has significant deposits. Mining of these materials in the United States had ceased almost entirely — mostly because of environmental regulations that have increased the cost of production — but improved mining methods are making these sources usable again.

Rare earth elements are never found in isolation; instead, they’re mixed together in certain natural ores, and must be separated out through chemical processing. “They’re bundled together in these deposits,” Kirchain says, “and the ratio in the deposits doesn’t necessarily align with what we would desire” for the current manufacturing needs.

Neodymium and dysprosium are not the most widely used rare earth elements, but they are the ones expected to see the biggest “pinch” in supplies, Alonso explains, due to projected rapid growth in demand for high-performance permanent magnets.

Kirchain says that when they talk about a pinch in the supply, that doesn’t necessarily mean the materials are not available. Rather, it’s a matter of whether the price goes up to a point where certain uses are no longer economically viable.

The researchers stress that their study does not mean there will necessarily be a problem meeting demand, but say that it does mean that it will be important to investigate and develop new sources of these materials; to improve the efficiency of their use in devices; to identify substitute materials; or to develop the infrastructure to recycle the metals once devices reach the end of their useful life. The purpose of studies such as this one is to identify those resources for which these developments are most pressing.

While the raw materials exist in the ground in amounts that could meet many decades of increased demand, Kirchain says the challenge comes in scaling up supply at a rate that matches expected increases in demand. Developing a new mine, including prospecting, siting, permitting and construction, can take a decade or more.

“The bottom line is not that we’re going to ‘run out,’” Kirchain says, “but it’s an issue on which we need focus, to build the supply base and to improve those technologies which use and reuse these materials. It needs to be a focus of research and development.”

Barbara Reck, a senior research scientist at Yale University who was not involved in this work, says “the results highlight the serious supply challenges that some of the rare earths may face in a low-carbon society.” The study is “a reminder to material scientists to continue their search for substitutes,” she says, and “also a vivid reminder that the current practice of not recycling any rare earths at end-of-life is unsustainable and needs to be reversed.”

From PhysOrg: http://phys.org/news/2012-04-energy-scarce-materials.html

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Mar 11, 2012 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Colonialism & Conquest, Indigenous Autonomy

By Edward Helmore / The Guardian

Of the many projects commissioned by the Obama administration to showcase its commitment to renewable energy, few are as grandly futuristic as the multibillion-dollar solar power projects under construction across broad swaths of desert on the California-Arizona border.

But at least two developments, including the $1bn, 250-megawatt Genesis Solar near Blythe in the lower Colorado river valley and the Solar Millennium project, are beset with lengthy construction delays, while others are facing legal challenges lodged by environmental groups and Native American groups who fear damage to the desert ecology as well as to ancient rock art and other sacred heritage sites.

Out on the stony desert floor, Native Americans say, are sites of special spiritual significance, specifically involving the flat-tailed horned toad and the desert tortoise.

“This is where the horny toad lives,” explains Alfredo Figueroa, a small, energetic man and a solo figure of opposition who could have sprung from the pages of a Carlos Castaneda novel, pointing to several small burrows. Figueroa is standing several hundred metres into the site of Solar Millennium, a project backed by the Cologne-based Solar Millennium AG. The firm, which has solar projects stretching from Israel to the US, was last month placed in the hands of German administrators and its assets listed for disposal.

Figueroa is delighted with the news. “Of all the creatures, the horny toad is the most sacred to us because he’s at the centre of the Aztec sun calendar,” he says. “And the tortoise also, who represents Mother Earth. They can’t survive here if the developers level the land, because they need hills to burrow into.”

Figueroa, 78, a Chemehuevi Indian and historian with La Cuna de Aztlán Sacred Sites Protection Circle, has become one of the most vocal critics of the solar programme and expresses some unusually bold claims as to the significance of this valley: he claims it is the birthplace of the Aztec and Mayan systems of belief. He points out the depictions of a toad and a tortoise on a facsimile of the Codex Borgia, one of a handful of divinatory manuscripts written before the Spanish conquest.

On a survey of the 2,400-hectare site Figueroa points out a giant geoglyph, an earth carving he says represents Kokopelli, a fertility deity often depicted as a humpbacked flute player with antenna-like protrusions on his head. Kokopelli, he says, will surely be disturbed if the development here resumes.

The area is known for giant geoglyphs, believed by some to date back 10,000 years. Gesturing towards the mountains, he also describes Cihuacoatl – a pregnant serpent woman – he sees shaped in the rock formations. All of this, he says, amounts to why government-fast-tracked solar programmes in the valley, where temperatures can reach 54C, should be abandoned. It is a matter of their very survival.

“We are traditional people – the people of the cosmic tradition,” Figueroa explains. “The Europeans came and did a big number on us. They tried to destroy us. But they were not able to destroy our traditions, and it’s because of our traditions and our mythology that we’ve been able to survive. If we’d blended in with the Wasps – the white Anglo-Saxon Protestants – we’d have been lost long ago.”

At the Genesis Solar site, 20 miles west, Florida-based NextEra has begun to develop an 810-hectare site. The brackets that will hold the reflecting mirrors stand like sentinels. Backed by a $825m department of energy loan, Genesis Solar is planned as a centrepiece of the administration’s renewable energy programme, with enough generating capacity to power 187,500 homes.

But local Native American groups collectively known as the Colorado River Indian Tribes are demanding that 80 hectares of the development be abandoned after prehistoric grinding stones were found on a layer of ashes they say is evidence of a cremation site “too sacred to disturb”.

Read more from The Guardian: http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2012/mar/11/solar-power-mojave-desert-tribes