by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 17, 2016 | Colonialism & Conquest, Mining & Drilling

by Jen Moore / Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives

Stories of bloody, degrading violence associated with Canadian mining operations abroad sporadically land on Canadian news pages. HudBay Minerals, Goldcorp, Barrick Gold, Nevsun and Tahoe Resources are some of the bigger corporate names associated with this activity. Sometimes our attention is held for a moment, sometimes at a stretch. It usually depends on what solidarity networks and under-resourced support groups can sustain in their attempts to raise the issues and amplify the voices of those affected by one of Canada’s most globalized industries. But even they only tell us part of the story, as Todd Gordon and Jeffery Webber make painfully clear in their new book, The Blood of Extraction: Canadian Imperialism in Latin America (Fernwood Publishing, November 2016).

“Rather than a series of isolated incidents carried out by a few bad apples,” they write, “the extraordinary violence and social injustice accompanying the activities of Canadian capital in Latin America are systemic features of Canadian imperialism in the twenty-first century.” While not completely focused on mining, The Blood of Extraction examines a considerable range of mining conflicts in Central America and the northern Andes. Together with a careful review of government documents obtained under access to information requests, Gorden and Webber manage to provide a clear account of Canadian foreign policy at work to “ensure the expansion and protection of Canadian capital at the expense of local populations.”

Fortunately, the book is careful, as it must be in a region rich with creative community resistance and social movement organizing, not to present people as mere victims. Rather, by providing important context to the political economy in each country studied, and illustrating the truly vigorous social organization that this destructive development model has awoken, the authors are able to demonstrate the “dialectic of expansion and resistance.” With care, they also show how Canadian tactics become differentiated to capitalize on relations with governing regimes considered friendly to Canadian interests or to try to contain changes taking place in countries where the model of “militarized neoliberalism” is in dispute.

The spectacular expansion of “Canadian interests” in Latin America

We are frequently told Canadian mining investment is necessary to improve living standards in other countries. Gordon and Webber take a moment to spell out which “Canadian interests” are really at stake in Latin America—the principal region for Canadian direct investment abroad (CDIA) in the mining sector—and what it has looked like for at least two decades: “liberalization of capital flows, the rewriting of natural resource and financial sector rules, the privatization of public assets, and so on.”

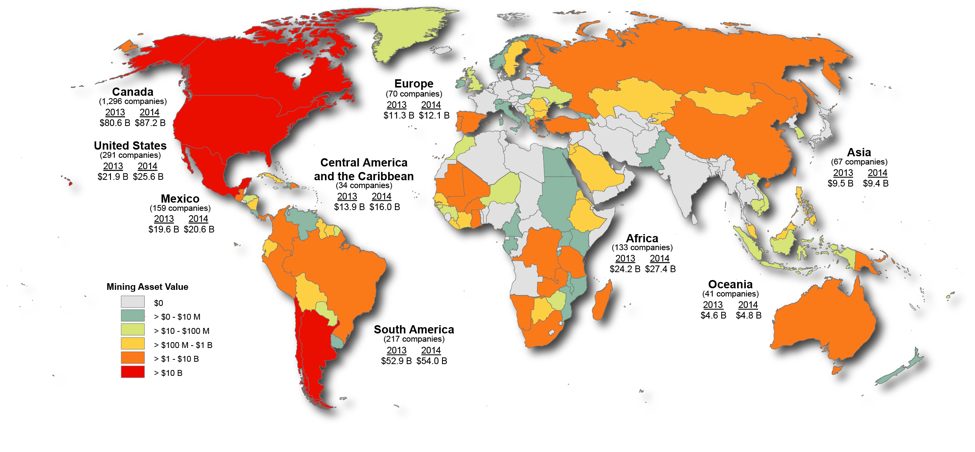

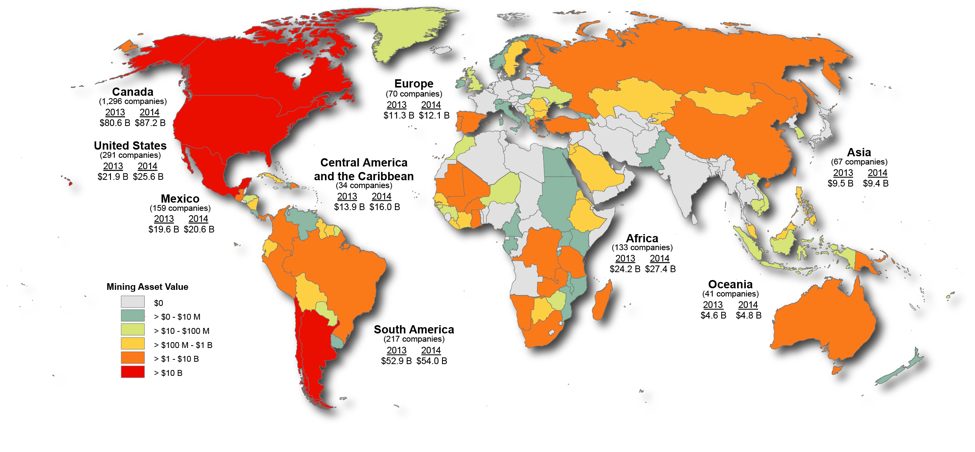

Cumulative CDIA in the region jumped from $2.58 billion in stock in 1990 to $59.4 billion in 2013. These numbers are considerably underestimated, the authors note, since they do not include Canadian capital routed through tax havens. In comparison, U.S. direct investment in the region increased proportionately about a quarter as much over the same period. Despite having an economy one-tenth the size of the U.S., Canadian investment in Latin America and the Caribbean is about a quarter the value of U.S. investment, and most of it is in mining and banking.

Canadian mining investment abroad

To cite a few of the statistics from Gordon and Webber’s book, Latin America and the Caribbean now account for over half of Canadian mining assets abroad (worth $72.4 billion in 2014). Whereas Canadian companies operated two mines in the region in 1990, as of 2012 there were 80, with 48 more in stages of advanced development. In 2014, Northern Miner claimed that 62% of all producing mines in the region were owned by a company headquartered in Canada. This does not take into consideration that 90% of the mining companies listed on Canadian stock exchanges do not actually operate any mine, but rather focus their efforts on speculating on possible mineral finds. This means that, even if a mine is eventually controlled by another source of private capital, Canadian companies are very frequently the first face a community will see in the early stages of a mining project.

The results have been phenomenal “super-profits” for private companies like Barrick Gold, Goldcorp and Yamana, who netted a combined $2.8-billion windfall in 2012 from their operating mines, according to the authors. (Canadian mining companies earned a total of $19.3 billion that year.) Between 1998 and 2013, the authors calculate that these three companies averaged a 45% rate of profit on their operating mines when the Canadian economy’s average rate of profit was 11.8%.

Compare this to Canada’s miserly Latin American development aid expenditures of $187.7 million in in 2012—a good portion of this destined for training, infrastructure and legislative reform programs intended to support the Canadian mining sector. Or consider that the same year $2.8 billion was taken out of Latin America by three Canadian mining firms, remittances back to the region from migrants living in Canada totalled only $798 million (much more than Canadian aid).

Without spelling out the long-term social and environmental costs of these operations—costs that are externalized onto affected communities—or going into the problematic ways that private investment and Canadian aid can be used to condition local support for a mine project, Gordon and Webber posit that “super-profits” may be precisely the “Canadian interests” the government’s foreign policy apparatus is set up to defend—not authentic community development, lasting quality jobs or a reliable macroeconomic model.

State support for “militarized neoliberalism”

The argument that the role of the Canadian state is “to create the best possible conditions for the accumulation of profit” is central to Gordon and Webber’s book. From the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) down, Canadian agencies and foreign policy have been harnessed to justify “Canadian plunder of the wealth and resources of poorer and weaker countries.” Furthermore, they write, Canada has actively supported the advancement of “militarized neoliberalism” in the region, as country after country has returned to extractive industry, and export-driven and commodity-fuelled economic growth, which comes with high costs for affected-communities and other macroeconomic risks:

The extractive model of capitalism maturing in the Latin American context today does not only involve the imposition of a logic of accumulation by dispossession, pollution of the environment, reassertion of power of the region by multinational capital, and new forms of dependency. It also, necessarily and systematically involved what we call militarized neoliberalism: violence, fraud, corruption, and authoritarian practices on the part of militaries and security forces. In Latin America, this has involved murder, death threats, assaults and arbitrary detention against opponents of resource extraction.

The rapid and widespread granting of mining concessions across large swaths of territory (20% of landmass in some countries), regardless of who lives there or how they might value different lands, water or territory, has provoked hundreds of conflicts and powerful resistance from the community level upward. In reaction, and in order to guarantee foreign investment, in many parts of the region states have intensified the demonization and criminalization of land- and environment-defenders, while state armed forces have increased their powers, and para-state armed forces expanded their territorial control.

Far from being a countervailing force to this trend, the Canadian state has focused its aid, trade and diplomacy on those countries most aligned with its economic interests. It is not unusual to see public gestures of friendship or allegiance toward governments “that share [Canada’s] flexible attitude towards the protection of human rights,” such as Mexico, post-coup Honduras, Guatemala and Colombia. Meanwhile, Canada has used diverse tactics (in Venezuela and Ecuador, for example) to contain resistance and influence even modest reforms.

Canada’s ‘whole-of-government’ approach in Honduras

One of the more detailed examples in Blood of Extraction of Canadian imperialism in Central America covers Canada’s role in Honduras following the military-backed coup in June 2009. Documents obtained from access to information requests provide new revelations and new clarity into how Canadian authorities tried to take advantage of the political opportunities afforded by the coup to push forward measures that favour big business. Once again, though other economic sectors are discussed, mining takes centre stage.

After the terrible experience of affected communities with Goldcorp’s San Martin mine (from the year 2000 onward), Hondurans successfully put a moratorium on all new mining permits pending legal reforms promised by former president José Manuel Zelaya. On the eve of the 2009 coup, a legislative proposal was awaiting debate that would have banned open-pit mining and the use of certain toxic substances in mineral processing, while also making community consent binding on whether or not mining could take place at all. The debate never happened.

Instead, shortly after the coup, and once a president more friendly to “Canadian interests” was in place following a questionable election, the Canadian lobby for a new mining law went into high gear. A key goal for the Canadian government, according to an embassy memo, was “[to facilitate] private sector discussions with the new government in order to promote a comprehensive mining code to give clarity and certainty to our investments.” Another embassy record said that mining executives were happy to assist with the writing of a new mining law that would be “comparable to what is working in other jurisdictions” and developed with a resource person with whom their “ideologies aligned.”

In a highly authoritarian and repressive context, and under the deceptive banner of corporate social responsibility, the Canadian Embassy—with support from Canadian ministerial visits, a Honduran delegation to the annual meeting of the Prospectors & Developers Association of Canada (PDAC), and overseas development aid to pay for technical support—managed to get the desired law passed in early 2013, lifting the moratorium. Then, in June 2014, with full support from Liberals and Conservatives in the House of Commons and the Senate, Canada ratified a free trade agreement with Honduras, effectively declaring that “Honduras, despite its political problems, is a legitimate destination for foreign capital,” write Gordon and Webber.

Contrary to the prevailing theory in Canada that sustaining and increasing economic and political engagement with such a country will lead to improved human rights, the social and economic indicators in Honduras have gotten worse. Since 2010, the authors note, Honduras has the worst income distribution of any country in Latin America (it is the most unequal region in the world). Poverty and extreme poverty rates are up by 13.2% and 26.3%, respectively, after having fallen under Zelaya by 7.7% and 20.9%. Compounding this, Honduras is now the deadliest place to fight for Indigenous autonomy, land, the environment, the rule of law, or just about any other social good.

A strategy of containment in Correa’s Ecuador

In contrast to how Canada has more strongly aligned itself with Latin American regimes openly supportive of militarized neoliberalism, the experience in Ecuador under the administration of President Rafael Correa illustrates how Canada considers “any government that does not conform to the norms of neoliberal policy, and which stretches, however modestly, the narrow structures of liberal democracy…a threat to democracy as such.”

In the chapter on Ecuador, Gordon and Webber provide a detailed account of Canada’s “whole-of-government” approach to containing modest reforms advanced by Correa and undermining the opposition of affected communities and social movements to opening the country to large-scale mining. A critical moment in this process occurred in mid-2008, when a constitutional-level decree was issued in response to local and national mobilizations against mining. The Mining Mandate would have extinguished most or all of the mining concessions that had been granted in the country without prior consultation with affected communities, or that overlapped with water supplies or protected areas, among other criteria. It also set in place a short timeline for the development of a new mining law.

The Canadian embassy immediately went to work. Meetings between Canadian industry and Ecuadorian officials, including the president, were set up to ensure a privileged seat at talks over the new mining law. Gordon and Webber’s review of documents obtained under access to information requests further reveals that the embassy even helped organize pro-mining demonstrations together with industry and the Ecuadorian government. Embassy records describe their intention “to create sympathy and support from the people” as part of a “a pro-image campaign,” which included “an aggressive advertisement campaign, in favour of the development of mining in Ecuador.” Meanwhile, behind closed doors, industry threatened to bring international arbitration against Ecuador under a Canada–Ecuador investor protection agreement (which a couple of investors eventually did).

Ultimately, the authors conclude, Canadian diplomacy “played no small part” in ensuring that the Mining Mandate was never applied to most Canadian-owned projects, and that a relatively acceptable new mining law was passed in early 2009. While embassy documents show the Canadian government considered the law useful enough to “open the sector to commercial mining,” it was still not business-friendly enough, particularly because of the higher rents the state hoped to reap from the sector. As a result, the embassy kept up the pressure, including using the threat of withholding badly needed funds for infrastructure projects until mining company concerns were addressed and dialogue opened up with all Canadian companies.

Not discussed in The Blood of Extraction, we also know the pressure from Canadian industry continued for many more years, eventually achieving reforms, in 2013, that weakened environmental requirements and the tax and royalty regime in Ecuador. Meanwhile, as the door opened to the mining industry, mining-affected communities and supporting organizations were feeling the walls of political and social organizing space cave in, as they faced persistent legal persecution and demonization from the state itself, while the serious negative impacts of the country’s first open-pit copper mine started to be felt.

Canada’s “cruel hypocrisy”

The Blood of Extraction is a helpful portrait of “the drivers behind Canadian foreign policy.” Gordon and Webber lay bear “a systematic, predictable, and repeated pattern of behaviour on the part of Canadian capital and the Canadian state in the region,” along with its systemic and almost predictable harms to the lives, wellbeing and desired futures of Indigenous peoples, communities and even whole populations. They call it Canada’s “cruel hypocrisy.”

The problem is not Goldcorp or HudBay Minerals, Tahoe Resources or Nevsun. These companies are all symptoms of a system on overdrive, fuelling the overexploitation of land, communities, workers and nature to fill the pockets of a small transnational elite based principally in the Global North. If we cannot see how deeply enmeshed Canadian capital is with the Canadian state—how “Canadian interests” are considered met when Canadian-based companies are making super-profits, even through violent destruction—we cannot get a sense of how thoroughly things need to change.

Jen Moore is the Latin America Program Coordinator at Mining Watch Canada, working to support communities, organizations and networks in the region struggling with mining conflicts.

This article was published in the November/December 2016 issue of The Monitor. Click here for more or to download the whole issue.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jun 18, 2016 | Colonialism & Conquest

By Laura Hobson Herlihy / Cultural Survival

The Miskitu people (pop. 185,000) live in Muskitia, a rainforest region that stretches along the Central American Caribbean coast from Black River, Honduras to just south of Bluefields, Nicaragua. Two-thirds of Muskitia and the Miskitu people reside in Nicaragua. The Miskitu people in Nicaragua today are in a crisis situation. Armed mestizo colonists are attacking their communities, pillaging and confiscating their rainforest lands. This article is a cry for help.

The Miskitu people have legal ownership of their lands guaranteed by Nicaraguan Law 445, the ILO Convention 169, and the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People. Yet, mestizo colonists (called, colonos) from the interior and Pacific coast have invaded, and now illegally occupy, nearly half of their lands. In September 2015, violence over land conflicts erupted in the Miskitu territories of Wangki Twi-Tasba Raya and Li Aubra. These territories are located near the Coco or Wangki River, the international border between Nicaragua and Honduras.

Since September, mestizo colonists with automatic weapons have killed, injured, and kidnapped more than 80 Miskitu men with impunity. In fear for their lives, between 1-2,000 Miskitu refugees have fled to Waspam and Puerto Cabezas-Bilwi and Honduran border communities. The refugees–mainly women, children, and elders–are suffering from starvation and lack medical supplies. Children have not attended school for six months. Meanwhile, periodic attacks continue on Miskitu communities in Wangki Twi-Tasba Raya.

Much of the violence now occurring revolves around article 59 of the Communal Property Law (law 445). Article 59 requires the Nicaraguan state to complete saneamiento, the cleansing or the removal of colonists and industries from Indigenous and Afro-descendant territories. The current Nicaraguan government publically agreed to saneamiento but has not responded. Similarly, the government still has not provided protection to the Miskitu communities under attack or assistance to the refugees. As a result of the government’s delayed reaction to the crisis, the Miskitu people now suspect the Sandinista (FSLN) state to be complicit with the colonists’ invasion of their Indigenous territories.

In a separate but related issue, the FSLN government passed the Canal Law (Act 840) that approved the Chinese-backed (HKND) inter-oceanic canal to cut through the ancestral homeland of the Indigenous and Afro-descendant peoples along the Nicaraguan Caribbean coast. Tensions are rising over Indigenous territoriality and land rights, especially between the Miskitu people and President Daniel Ortega’s Sandinista government. The tense situation over land rights today bares eerie similarities to the war-torn years of the 1980s in Nicaragua, when Ortega first served as President (1985-1990) and the Miskitu fought as counter-revolutionary warriors in the Contra war within the Sandinista revolution (1979-1990).

As a US anthropologist who has worked for over twenty years with the Honduran and Nicaraguan Miskitu people, I had the opportunity to attend the 2016 United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (May 9-20). On Thursday, May 12, I recorded Miskitu leader Brooklyn Rivera’s intervention in the session, “Dialogue with Indigenous Peoples.” Rivera has served as the Líder Máximo (literally, Highest Leader) of the Nicaraguan Miskitu people for over 30 years; after rising to power as a military leader in the revolution and war, Rivera in 1987 founded and became the long-term director of the Indigenous organization Yatama (Yapti Tasba Masraka Nanih Aslatakanka/Sons of Mother Earth). Special thanks to Costa Rican anthropologist Fernando Montero (ABD, Columbia) for transcribing Rivera’s United Nations intervention in Spanish and translating it to the English below.

English Version

My name is Brooklyn Rivera. I am both a son and the highest leader of the Miskitu people of the Nicaraguan Muskitia. As we know, the rights of Indigenous peoples are essentially human rights. According to Article 1 of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Indigenous people have the right, both as peoples and as individuals, to the full enjoyment of their human rights and fundamental liberties. In my country of Nicaragua, the rights of Indigenous people have suffered severe setbacks in the last several years. Indeed, the current Sandinista government–contrary to its rhetoric in international forums and in flagrant violation of the rights of Indigenous peoples–freely acts against Indigenous peoples, advancing a consistent policy of aggression and internal colonialism.

Consider the following within the specific sphere of Indigenous peoples’ rights: the government imposes violence against our communities by means of settlers who invade ancestral territories, carrying out armed attacks, murders, kidnappings, rape, and displacement, producing refugees, most of whom are women, children, and people of old age. All this occurs in the face of governmental and institutional passivity, even complicity. Moreover, the Nicaraguan government is currently implementing a policy of militarization in our communities and fishing territories, committing murders such as that of our brother and leader Mario Lehman last September. In like manner, the government is overtly trampling on our communities’ right to ancestral autonomy by interfering with the election of their leaders according to their own practices and customs, devoting itself to destroying the structure and traditional procedures of our communities with the aim of replacing them with the so-called Sandinista Leadership Committees, part of their party structure. In this way they create and impose a spurious and noxious structure parallel to Indigenous authorities. You will understand that, by applying this policy, the government and the ruling party are fomenting division within families and communities, destroying their social fabric, cultural values and [imposing] heightened suffering and poverty. In addition, in open violation of the right to work, the Sandinista government denies jobs and government positions to Indigenous professionals and technicians, demanding that they become members of their party before considering them for these positions.

With regard to the sphere of the environment of our peoples in Nicaragua, I must first point out the dispossession of lands and territories suffered by Miskitu communities perpetrated by cattle ranchers, mining companies, and wealthy sectors linked to the government and the ruling party, who use settlers as spearheads. In this invasion, armed settlers arrive in our lands, advance the agricultural frontier, occupy extensions of territory, and destroy the habitats and ecosystems of Indigenous peoples, preying on their fauna, flora, and marine ecology. Needless to say, this extractivist policy involves the looting of ancestral communal resources such as forests, flora, mineral resources, water resources, and land itself with the illegal land sales in which settlers participate. I must also mention the promotion of megaprojects such as the interoceanic canal and the Tumarin hydroelectric dam in Awaltara, both of which violate Indigenous peoples’ right to prior, free, and informed consent. These megaprojects render entire communities vulnerable to disappearing along with their culture and language. This is the case of the Rama people, a small, vulnerable people in danger of extinction who reside in the Southern Moskitia. In the face of this crude reality and despite its demonstrated lack of political will and its disrespect for international laws and institutions—not to mention my own arbitrary, illegal expulsion from the National Parliament—once again we demand from the Nicaraguan government:

1. The immediate application of the recommendations issued last December by the UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, in reference to the cleansing [“saneamiento”] of Indigenous territories and the protection of our communities in the face of settler invasion;

2. The immediate enactment of the precautionary measures suggested by the OAS’ Human Rights Commission on behalf of the Indigenous communities in the regions of Tasba Raya and Wangki Li Auhbra (location in the municipality of Waspam), approved in October 2015 and expanded in January 2016;

3. The immediate launch of a process of genuine dialogue and negotiation with Indigenous peoples via their organizations and leaders to reach real solutions based on respect for Indigenous peoples and the recognition of their dignity, as outlined in existing frameworks;

4. Finally, the immediate restitution of the undersigned as legislator, in accordance with his status as a popularly elected official put in power thanks to the votes of Indigenous peoples, whose constitutional and legal rights were violated with my arbitrary and illegal expulsion from Parliament.

I end my intervention by asking all participants, especially the Indigenous peoples in this forum, to engage in active solidarity with the Indigenous peoples of Nicaragua and their organizations as they resist and demand dignity, rights, and justice from the Sandinista government in Nicaragua.

Thank you, Mr. President.

En Espanol

Soy Brooklyn Rivera, hijo del pueblo mískitu de la Mosquitia nicaragüense y su dirigente principal. Como sabemos, los derechos de los pueblos indígenas son esencialmente derechos humanos. Como se establece en el artículo 1 de la Declaración de la ONU sobre los Pueblos Indígenas, los indígenas tienen derecho como pueblos o como individuos al disfrute pleno de todos sus derechos humanos y las libertades fundamentales. El país de donde vengo yo, Nicaragua, en los últimos años ha experimentado un grave retroceso en el ejercicio de los derechos de nuestros pueblos indígenas, recogido en el marco legal interno y externo del país. En efecto, el actual gobierno sandinista, contrario a su retórica en los foros internacionales y en abierta violación de los derechos de los pueblos indígenas reconocidos en la Constitución Política y en las demás leyes y los instrumentos internacionales suscritos, se dedica a actuar libremente en su contra impulsando toda una política de agresión y colonialismo interno.

Veamos: en el ámbito específico de los derechos humanos de nuestros pueblos indígenas, a través de los colonos invasores de los territorios ancestrales, impone una situación de violencia en contra de nuestras comunidades mediante ataques armados, cometiendo asesinatos, secuestros, violaciones y desplazamentos, produciendo refugiados, mayormente niños, mujeres y ancianos. Todo esto ocurre ante la pasividad y aun la complicidad del gobierno y sus instituciones. Más aún, el gobierno nicaragüense implementa una política de militarización de las comunidades y las áreas de pesca, en las que cometen asesinatos como en el caso del crimen del hermano dirigente Mario Lehman ocurrido en el mes de septiembre pasado. De la misma forma, el gobierno aplica un abierto atropello al derecho de autonomía ancestral de nuestras comunidades en la elección de sus autoridades basada en los usos y costumbres, cuando a través de sus turbas partidarias y con el acompañamiento de sus policías y hasta de militares, aún así sin el mínimo respeto a las leyes y formas organizativas propias, se empecina en destruir la estructura y los procedimientos tradicionales de nuestras comunidades con el fin de sustituirlos con los llamados Comités de Liderazgo Sandinista, una estructura de su partido en el poder, creando e imponiendo así una estructura espuria y nociva, paralela a las autoridades indígenas. Como comprenderán, aplicando esta política el gobierno y su partido crean división entre las familias y comunidades, destruyendo sus tejidos sociales, valores culturales y mayor sufrimiento y pobreza. Además, el gobierno sandinista en abierta discriminación al derecho al trabajo, niega a los profesionales y técnicos de los pueblos indígenas el derecho al trabajo cuando exige que debe convertir a ser miembro de su partido para ocupar cargos o empleo en el país.

En relación al ámbito del medio ambiente de nuestros pueblos en Nicaragua, debo iniciar señalando el despojo de las tierras y territorios que sufren las comunidades en la Mosquitia de parte de los terratenientes ganaderos, empresas mineras y grupos adinerados vinculados al gobierno y a su partido, utilizando a los colonos como punta de lanza. En la invasión, los colonos armados llegan a nuestras tierras, aplican un avance agropecuario, ocupan extensiones de territorio y destruyen los hábitats y los ecosistemas de los pueblos indígenas, cometiendo depredaciones ambientales en su fauna, flora y entorno marino. Lógicamente, con esta política extractivista pasa por el saqueo de los bienes comunales ancestrales tales como los bosques, la flora, los recursos mineros, los recursos hídricos y la misma tierra con el tráfico ilegal de parte de los colonos. También aquí debo mencionar el impulso de los megaproyectos tales como el canal interocéanico y el hidroeléctrico Tumarín en Awaltara, en ambos casos violentando el derecho al consentimiento previo, libre e informado de los pueblos, impulsan sus megaproyectos en los que exponen la desaparición de comunidades enteras junto con su cultura y su idioma. Tal es el caso del pueblo Rama, pueblo pequeño, vulnerable y en proceso de extinción, ubicado en la Mosquitia Sur. Ante esta cruda realidad y a pesar de su falta de voluntad política demostrada y de su irrespeto a las leyes y las instituciones internacionales, así como de mi expulsión arbitrario e ilegal del Parlamento Nacional, como un esfuerzo de solución al conflicto impuesto, una vez más exigimos al gobierno nicaragüense:

- La inmediata aplicación de las recomendaciones de la Relatora Especial de las Naciones Unidas sobre los Derechos de los Pueblos Indígenas, emitidas en el mes de diciembre pasado, referentes al cumplimiento de la etapa de saneamiento de los territorios y de la protección de nuestras comunidades ante la invasión de los colonos;

- El inmediato cumplimiento de las medidas cautelares presentadas de parte de la Comisión de Derechos Humanos de la OEA a favor de las comunidades indígenas de la zona de Tasba Raya y de Wangki Li Auhbra en el municipio de Waspam, y abrobadas en el mes de octubre 2015 y ampliadas en enero de 2016;

- La inmediata apertura de un proceso genuino de diálogo y negociaciones con los pueblos indígenas a través de sus organizaciones y líderes que conduzcan a unas soluciones reales basadas en el respeto y el reconocimiento de la dignidad y los derechos de nuestros pueblos reconocidos en las normativas;

- Finalmente, la restitución inmediata del suscrito como legislador electo popularmente con los votos de sus pueblos indígenas, violentando mis derechos constitucionales y legales con el despojo arbitrario e ilegal cometido durante mi expulsión del Parlamento.

Termino mi intervención requiriendo a todas y todos los participantes, mayormente a los pueblos indígenas de este foro, una solidaridad activa con los pueblos indígenas y sus organizaciones en Nicaragua en el marco de su resistencia y demanda de dignidad, derecho y justicia ante el gobierno sandinista en Nicaragua.

Gracias, Presidente.

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Dec 12, 2015 | Male Supremacy, Mining & Drilling

By teleSUR

Women from various Guatemalan communities struggling against resource extraction projects often face repression, criminalization, and violence. Mining projects and resource extraction in Guatemala exacerbate the discrimination and violence that women face in all areas of Guatemalan society, Rights Action Director Grahame Russell told teleSUR English Thursday.

“Repression and human rights violations caused by global mining operations in Guatemala have added negative effects on women in general and indigenous women in particular,” Russell told teleSUR English.

Russell’s comments come after human rights defenders slammed Guatemala’s widespread resource extraction on Wednesday for violating human rights, especially the rights of women, who often face attacks, sexual violence, and social and political repression for their work defending land and natural resources.

“Participants in the ‘We are Rights Defenders’ Forum.”

Women from various communities struggling against unwanted resource extraction projects throughout the country gathered in the capital Guatemala City to discuss the repression, criminalization, and violence disproportionately faced by women rights defenders, especially indigenous women, Prensa Latina reported.

Among the representatives were women from the community of La Puya, in central Guatemala, where they are key leaders in the blockade against the construction of a gold mine and central to the movement’s strategy of nonviolent resistance.

ANALYSIS: Facing Violence, Resistance Is Survival for Indigenous Women

The women called attention to the links between violence against women and the development model in Guatemala based on privatization, mining extraction, and exploitation of natural resources.

“When repression is committed by mining company security guards, soldiers, and police, rape and sexualized violence have also been used against women and girls,” said Russell. “When communities suffer health harm due to mining contaminated water sources, women and children suffer the consequences most.”

Forced displacement can also disproportionately impact women, Russell explained, as men sometimes accept low-paying mining jobs in exchange for their land behind the backs of women.

“For the rights of each one of the 58 million rural women in Latin America.”

According to women’s organizations present at the event, a femicide is committed in Guatemala every 10 hours, and one in every 10 women experience some form of gender violence. Guatemala, along with neighboring Central American countries El Salvador and Honduras, are among the worst countries in the world for gender violence and femicide.

Guatemalan activist, feminist artist, and politician Sandra Moran explained that women rights defenders regard women’s bodies, land, nature, history, and memory as all “territories in dispute,” Prensa Latina reported.

ANALYSIS: Femicide in Mesoamerica Persists as Systemic Gender Violence

According to Moran, violence against women “is a mechanism and effect of structural, patriarchal, capitalist system,” and this violence is used by the state to “control resistance, alternative proposals, and to maintain control over the bodies, sexualities, and lives of women,” she told teleSUR English earlier this year.

The activists’ message echoed the findings of a recent report by the Mesoamerican Initiative of Women Humans Rights Defenders, which found that women defending land and territory in the face of mining operations and other projects between 2012 and 2014 were the most vulnerable among all women rights defenders in Central America and Mexico to gender violence, including harassment, abuse, assassination attempts, and other attacks.

“Thirty-two women human rights defenders were murdered between 2012 and 2014. We do not forget them nor will we stop asking for justice.”

“It is extremely difficult to hold mining companies or government authorities, including police and soldiers, accountable — both in Guatemala and in Canada and the U.S. where most companies are based — when they carry out mining-related repression in general, let alone when it has doubly negative impacts on women and girls. Mining companies operating in Guatemala benefit from and contribute directly to the reigning impunity and corruption,” said Russell, referencing the precedent-setting case attempting to hold Canada’s Hudbay Minerals accountable in Canadian court for the rape of 11 indigenous women.

IN DEPTH: Women Resist

The call for more attention to be paid to the plight of women rights defenders comes ahead of the conclusion of the COP21 climate summit in Paris, where organizations and activists have slammed the draft deal for being weak on human rights protection and the recognition of indigenous communities in the context of climate change.

According to Global Witness, Guatemala is one of the 10 most dangerous countries in world for land and environmental defenders.

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Dec 5, 2015 | Indigenous Autonomy

By Fionuala Cregan / Intercontinental Cry

Image by Toni Fish/flckr. Some Rights Reserved.

For most Peruvians it was a Sunday like any other; but in the Wampis community of Soledad, it was a historic day. On November 29, the Wampis nation declared the formation of the first Autonomous Indigenous Government in Peru.

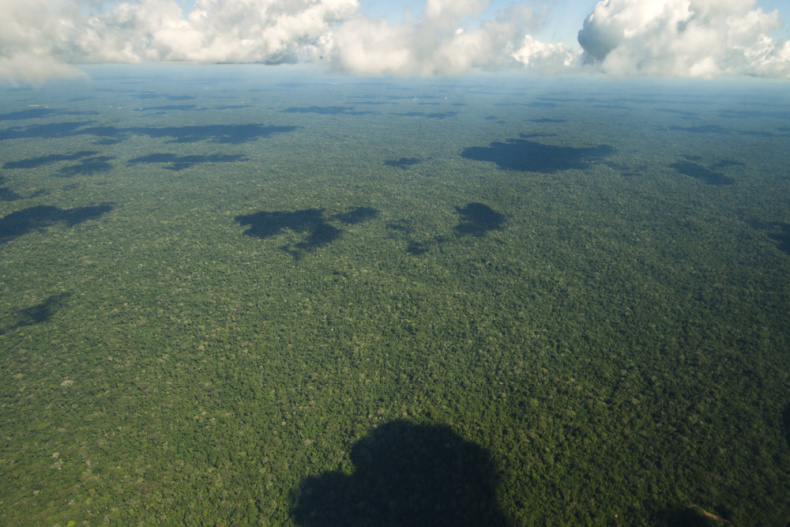

Spanning a 1.3 million hectare territory – a region the size of the State of Connecticut – the newly elected government brings together 100 Wampis communities representing some 10,613 people who continue to live a traditional subsistence way of life through hunting, fishing and small scale agriculture.

While the newly-formed government does not seek independence from Peru, its main role is to protect Wampis ancestral territory and promote a sustainable way of life that prioritizes well-being, food security and a healthy harmonious existence with the natural world.

This is no small task in today’s world; but it is nonetheless a necessary one, as Andres Noningo Sesen, Waimaku (Wampis Visionary), explains in a recent email to the New Internationalist. Due to the advance of mining and oil companies, illegal logging and palm oil plantations, the Wampis have found their livelihoods increasingly under threat.

We will still be Peruvian citizens but now we will have our own government responsible for our own territory. This will allow us to defend our forests from the threats of logging, mining, oil and gas and mega dams. As every year goes by these threats grow bigger.

This unity will bring us the political strength we need to explain our vision to the world and to the governments and companies who only see the gold and oil in our rivers and forests. For them, too often we are like a small insect who they want to squash. Any activity planned in our territory that will affect us will now have to be decided by our own government which represents all our communities.

The new Government consists of a President, Vice-President and an 80-member parliament with members elected by each Wampis community through their own local assemblies. Eventually, it will have 102 members. The basis for governance is the Statute of the Autonomous Territorial Government of the Wampis Nation, the result of a long process that took place over several years with the Wampis nation holding over 50 community meetings and 15 general assemblies to develop and debate the Statute which lays out their vision for the future in all areas of life including religion, spirituality, education, language and recovery of ancestral place names.

The Statute places special emphasis on the rights of women stating,

The Wampis nation will work to achieve true gender equality. The Government will work at all levels to promote a campaign to end all forms of violence against Wampis women… respect for women and unity takes precedence over cultural practices, specifically polygamy which took places in other historical contexts and which today can lead to social conflicts… The Wampis Government will prioritize access to third level education for women in different universities throughout the country.

The Statute also emphasizes the obligations of the Peruvian state to respect the rights and autonomy of indigenous peoples and nations. Amongst other principles, the Statute requires that any activity that could affect Wampis territory must secure the Free, Prior and Informed Consent of the Wampis nation. Specifically, this means that the Government of Peru cannot give out any further concessions that allow oil or mining companies to enter Wampis territory without a prior consultation process.

Currently, the Wampis are in the process of resisting such a concession that was granted, amongst others, to Afrodita S.A. for gold mining activities in a bi-national protected area along the border area with Ecuador. Since 2001, Afrodita has maintained a presence in this part of the Peruvian Amazon and in 2010 had its license suspended in the region of Cordillera del Cóndor due to the sustained resistance of indigenous communities living along the Cenpea and Maraño rivers. Both rivers suffered from severe mercury and cyanide stemming from mining activities in the region.

This, according to the newly elected Pamuk (first President) Wrays Pérez Ramirez, will be the largest challenge for the Autonomous Territorial Government of the Wampis Nation. The new president told Intercontinental Cry by phone:

We know that it will be difficult to get the National Government to support us and recognize our territory. It will seem unacceptable to the Government to have to consult us regarding any activity that could affect our territory. We know that it is going to be hard work but we are prepared. We are not going to stay silent not least when we have legal backing from national and international legislation regarding our right to self-determination and free, prior and informed consent. It will be difficult, but not impossible.

“The election has not taken place behind the Government’s back,” he adds. “The Governors of Amazonas and Loreto Province were invited to the summit as well as the Minister for Environment, Energy and Mining and the Minister for Culture but none attended. At the local level we have support and will work closely with, amongst others, the mayors of Rio Santiago and Morona who agree with our decision.”

The historic decision of the Wampis nation will be a source of inspiration for indigenous nations throughout Latin America. As a model for sustainable development and the preservation of some of our last remaining forests, it should also inspire world leaders as they meet at the COP21 Climate Summit in Paris this week.

“While the Peruvian government and other governments are in Paris talking about how to protect tropical forests and reduce contamination, we are taking concrete actions in our territory to contribute to this global goal,” says the newly elected Pamuk.

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Dec 3, 2015 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Indigenous Autonomy

by Marcela Belchior / Adital via Intercontinental Cry

What would initially appear to be the end of the line for the culture and survival of the Krenak indigenous people, impacted by the pollution of the Rio Doce, from the Mariana tragedy, in southeastern Brazil [state of Minas Gerais], could rekindle a 25 year struggle. After being left unable to live without the water of the river, the Krenak population is mobilized around a possible solution for the continuity of the community: to expand the demarcated area of the indigenous territory in the region and to migrate to a new location.

In an interview with Adital, Eduardo Cerqueira, member of the Indigenist Missionary Council (CIMI), Eastern Regional office, which comprises the states of Minas Gerais, Espírito Santo and the extreme south of Bahia, affirms that, as a way to resist the tragedy, the Krenak community [is calling] on the federal government to expand the demarcated area into 12,000 adjacent hectares, embracing the region where the State Park of Sete Salões, one of the Units of Conservation of nature belonging to the Government of Minas Gerais, is currently located.

“We find the strategy interesting, given that the existing area no longer provides conditions for survival. Something must be done”, attests Cerqueira. At present, the demarcated area of Krenak territory covers 4700 hectares. In this zone, extending more than three kilometers along the Doce River have been impacted and rendered unfit for drinking, fishing, bathing and irrigating vegetation in the vicinity, in the municipality of Resplendor, where 126 Krenak families live.

The State Park Parque de Sete Salões was created in 1998, and includes the municipalities of Conselheiro Pena, Itueta and Santa Rita do Itueto, corresponding to one of the largest remnants of Atlantic Forest in eastern Minas Gerais, with mountains, forests and waterfalls. Besides this, the area demanded has potential for indigenous community tourism, receiving visitors and marketing crafts, without damage to the environment.

The territory of the Krenak population, in Minas Gerais, was demarcated in the 1990s, but the entire length of the park was excluded, which today could once again be placed on the agenda. In the early 2000s, the Indigenous people filed a claim with the National Indian Foundation (Funai) and the federal government conducted a technical study on the matter, which to date has not been published. In the opinion of the Krenak, now, the situation is more than appropriate to fulfill the historical demand of the population.

“Various indigenous leaders are concerned about the territorial question. Now, it is a matter of necessity for this concern to be the focus of discussion. (…) This part of the region was not affected by the tailings [pollution],” defends the indigenous advocate. According to the CIMI counselor, since the socioenvironmental tragedy, the indigenous peoples affected have been assisted with emergency support, by means of tank trucks supplying water, transfer of basic food baskets and financial support for the families, which would ensure the community’s survival only in the short term.

“This tragedy was intensified by a period of severe drought. For over a year there has been no rain in the region. Because of this, the tributaries of the Rio Doce are dry. (…) The terrain is not favorable to agriculture. Livestock would be the most common form of indigenous survival, but it is not possible, without water,” explains Cerqueira.

Geovani Krenak laments the death of the Rio Doce: “we are one, people and nature, only one,” he says. Photo: Reproduction.

UNDERSTANDING THE CASE

A torrent of mud composed of mining tailings (residual waste, impurities and [chemical] material used for flushing out minerals) has been flooding the 800 kilometer length of the Rio Doce since November 5, after the rupture of the Fundão dam, of the Samarco mining company. This is controlled by Vale, responsible for innumerable and grave socioenvironmental damages in Brazil, and the multinational Anglo-Australian BHP Billiton, two of the largest mining companies in the world.

In addition to burying an entire district, impacting several others and polluting the Rio Doce, extending through the states of Minas Gerais, Espírito Santo and Bahia, the mud reached the sea over the weekend, even further amplifying the environmental damage, which could take more than two decades before signs of recovery even begin to present. In addition to the destruction of fauna and flora, seven deaths and 17 disappearances have so far been recorded.

KRENAK PEOPLE CLOSE ROAD IN PROTEST

Early last week, representatives of the Krenak indigenous people, whose tribe is situated on the banks of the Rio Doce, interrupted, in protest, the Vitória-Minas Railroad. Without water for more than a week, they said they would leave only when those responsible for the tragedy talk with them. “They destroyed our lives, they razed our culture and ignore us. This we do not accept,” asserted Aiah Krenak to the press.

Considered sacred, in a culture whose cosmological worldview is based on the interconnection between all beings – humans, plants, animals, etc., the river that flows through the tribe was utilized by 350 Indians, for consumption, bathing and cleansing. “With the people, this is not separate from us, the river, trees, the creatures. We are one, people and nature, only one”, says Geovani Krenak.

Krenak people protest on the Vitória-Minas Railroad. Photo: Reproduction.

Seated along the tracks, under a 41C. degree sun, Indians chanted music in gratitude to the river, in the Krenak language. “The river is beautiful. Thank you, God, for the river that feeds and bathes us. “The river is beautiful. Thank you, God, for our river, the river of all of us,” the words of shaman Ernani Krenak, 105 years of age, translated for the press.

His sister, Dekanira Krenak, 65 years old, is attentive to the impact of the death of the river affecting not only the indigenous peoples, being a source of resources for many communities. “It is not ‘us alone’, the whites who live on the riverbank are also in great need of this water, they coexist with this water, many fishermen [feed their] family with the fishes,” she points out.

Camped on site in tarpaulin shacks and sleeping mats in the open air, the Indians, now, must also face an unbearable swarm of insects. “It was never like this,” says Geovani Krenak. “These mosquitoes came with the polluted water, with fish that once fed us and that are now descending the river, dead, he reports.

Article originally published in Portuguese at

Adital. Translated to English for Intercontinental Cry by M.A. Kidd. Republished with permission of Intercontinental Cry.