by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Sep 7, 2018 | Listening to the Land

Featured image: Glen Canyon Dam on the Colorado River. © Michelle McCarron

by Will Falk / Voices for Biodiversity

I need to come clean. When I joined Colorado River Ecosystem v. Colorado, the first-ever federal lawsuit to seek personhood and the rights of nature for a major ecosystem, my intentions were not completely sincere. The truth is, I never thought we had a chance in hell. I saw the lawsuit as an opportunity to guide concerned people through a process that would shatter their false hopes, replace them with experiential knowledge of the vast difficulties inherent in working for change within the legal system and catalyze more effective action.

The lawsuit failed, of course. The Colorado Attorney General privately threatened the attorney representing us, Jason Flores-Williams, with sanctions if he did not withdraw the case. When he refused, the Attorney General formally filed a request for sanctions with the court and a motion to dismiss in the same afternoon. Flores-Williams, afraid that he could not respond adequately to both the sanctions and the motion to dismiss, voluntarily withdrew the case.

When filing a lawsuit, however, it’s best not to proclaim publicly that you expect the case to fail. Judges jealously guard their calendars from anything they perceive to be a waste of time. Corporate and government lawyers vigilantly monitor individuals involved in cases filed against them for any opportunity to argue that novel legal theories like the rights of nature are frivolous, to label them as attempts to harass corporations or government, and to demand that they be punished with sanctions. Media pundits search for audio clips and social media posts to take out of context while accusing grassroots groups of filing lawsuits as a backhanded fundraising ploy.

At the same time, and in order to shatter as many hopes as possible, it was necessary to attract attention. No one likes a loser. If our supporters caught so much as a whiff of my true disbeliefs, when the case failed, they could mistake the failure as the result of the half-assed efforts of activists who weren’t truly committed, instead of the result of a legal system designed to protect exploitation of the natural world.

So I suspended my disbelief and dove zealously into the work. For four months, the lawsuit was my full-time job. I sifted through case law for opinions supporting our position. I wrote a portion of the document, called the “complaint,” that signaled the official filing of the lawsuit. I wrote a series of articles describing the need for the rights of nature. I gave interviews to journalists, radio hosts and members of Comedy Central’s The Opposition production team.

And I bit my tongue over and over again.

In the five weeks before the case was dismissed, I put 4,000 miles on my 2004 Jeep Grand Cherokee traveling with photographer Michelle McCarron around the Colorado River Basin. After all that stress, my poor Jeep’s transmission blew up yesterday, so I have nowhere to go and nothing to do but reflect. With time so short and the need for effective action so great, I wonder if I wasted my time appealing to a legal system that exists to protect those destroying the natural world. I wonder if I betrayed the trust of the good people rooting so hard for the lawsuit to succeed. Worst of all, I wonder if I betrayed the river.

***

I bit my tongue on the steps of the Alfred A. Arraj Federal Courthouse in Denver, for example. I stood before a crowd gathered to hear me speak about the lawsuit. We were supposed to have a hearing, but the court had postponed it at the last minute. With so many of us traveling to Denver from across the Colorado River Basin, we decided to proceed with the press conference anyway.

© Michelle McCarron

It wasn’t the anxiety that public speaking can induce that produced the tremor in my hand, the acid in my gut and the quiver in my voice. It was a simple question, unresolved: Is it dishonest to speak of hope when you feel none?

I began my speech explaining that I had arrived there after spending three weeks with the river. I recounted the violence I witnessed in La Poudre Pass, where the Grand Ditch lies in wait to steal the Colorado River’s water moments after the union of snowpack, sunshine and gravity gives her birth. I reported the energy expended in pumping the river’s water uphill from Lake Granby reservoir to Shadow Mountain reservoir and then into Grand Lake before the Alva B. Adams tunnel drags the water 13 miles across the Continental Divide and beneath Rocky Mountain National Park to meet Front Range demands. I described the view from Palisade, Colorado, where peaches are grown in the middle of the desert and crisscrossing canals, seen from the mountains, appear as vast, mechanical tattoos sewn into the flesh of the land.

I paused at this point, knowing that after presenting my audience with this series of distressing images, I was supposed to leave them with a positive message. While I reflected on what I had seen and said, however, I felt the river’s truth spill over me.

For weeks, I thought I had been listening to the Colorado River. But she isn’t a river anymore. Not truly. She has been so diverted and dammed, experienced so much extraction and exploitation, that the best way to describe her is not as a river, but as an industrial project, as a series of tunnels, concrete channels and canals, as another tortured corpse stretched across civilization’s rack.

While this realization washed over me, I considered our lawsuit and the rights of nature. I wondered if it is possible to grant rights to a ghost. I questioned whether the Colorado River could ever recover from what’s been done to her. Grief threatened to overwhelm me, to silence me in despair. If I had been by myself, caught in the flow of these emotions in private, or if I was simply being honest, I would have fallen to the concrete and wept. I steadied myself and as the despair trickled away, rage rushed in to take its place. That rage burned with the heat of the desert sun reflected in the Colorado’s face and I knew that, ghost or not, she who haunts is not dead.

But, again, I said nothing of her rage, of her attempts to knock down dams, of her furious floods. I said nothing to acknowledge her ghost. Instead, in calm, reasonably legal tones, I urged the crowd to support the rights of nature.

***

The case is now finished. I can stop biting my tongue and spit the blood out. I can be honest. If I betrayed you, I am sorry. If I betrayed the river, I beg forgiveness. As an act of penance, I offer the stories that follow. These stories are what I really think. These stories are what I wish I said when the journalists were scribbling down my words, when I sat, live and on air, at the radio microphones, and when the cameras were recording. These stories are the truth.

We listed the river as the only plaintiff, so it could be properly said that the Colorado River herselfwas suing the State of Colorado. Major ecosystems are not currently considered capable of bearing rights or filing their own lawsuits under American law, so I agreed, with four others, to serve as a “next friend” of the Colorado River. Similar to guardians ad litem, next friends represent the interests of those deemed legally incompetent, such as children, the mentally disabled and rivers.

Simply put, next friends speak for those who can’t speak for themselves.

On a general level, it’s not difficult to understand the Colorado River’s interests. A simple Google search will tell you that pollution kills the river’s inhabitants, climate change threatens the snowpack that provides much of the river’s water, and dams prevent the river from flowing to the sea in the Gulf of California. But, friendship, even legal “next friendship,” entails an intimate and personal relationship. To best represent the Colorado River’s interests, to be her friend, I wanted to build this intimate, personal relationship with her. To build a relationship with someone is to speak with her, to spend time with her, to listen to her. And that’s what I did.

My trip with Michelle around the Colorado River Basin was guided by two questions. Everywhere we went, I asked the Colorado River: “Who are you? And, what do you need?” I asked these questions out loud, so she could hear them. I will not apologize for talking with a river.

© Michelle McCarron

The Colorado River speaks, but apparently not in a language many humans understand. Water is one of life’s original vernaculars, and the Colorado River speaks an ancient dialect. Snowpack murmurs in the melting sun. Rare desert rain drops off willow branches to ring across lazy pools. Streams, running over dappled stones, sing treble while distant falls take the bass.

I am human, so I am an animal. Even though the colonization of generations of my ancestors, personal trauma and cultural conditioning threaten to deafen me, I am still capable, through my animal body, of hearing the languages of life. And I believe you are capable, too. If you’ll only try.

Though the lawsuit failed, I made a friend. When your friend is in grave danger, you do everything in your power to protect her. If you don’t, you cannot call yourself her friend. The Colorado River is in grave danger and as her friend, I know I must do everything I can to protect her. If my animality gives me the ears to listen, friendship requires that I find the tongue to translate the languages of life.

Human, animal, friend…these three existences combine and compel me to translate her voice from the languages of life into English.

***

To truly understand someone, you must begin at her birth. So, Michelle and I spent two days looking for the Colorado River’s headwaters in the cold and snow above La Poudre Pass on the north edge of Rocky Mountain National Park. The pass was accessible by an unpaved, winding, pot-holed trek named Long Draw Road. It took us fourteen miles through pine and fir forests and past the frigid Long Draw Reservoir before ending abruptly in a flat where the red trunks and brown branches of winter willows braced themselves against the breeze.

The road was covered in an inch of frosty mud that required slow speeds to avoid sliding into roadside ditches. The road’s ruggedness and incessant bumps combined with sub-freezing temperatures to ask us if we were serious about seeing the river’s headwaters. I was worried that Michelle’s ’91 Toyota Previa might struggle up the pass, but the van continued to live up to the Previa model’s cult status.

Long Draw Road foreshadowed the violence we would find at the river’s headwaters. Swathes of clearcut forests escorted us along the road to the pass. The Forest Service must have been too lazy to remove any single trees that fell on the road because their employees had simply chainsawed every tree within fifty yards of the road. About three miles from the road’s end, we ran into a long, low dam trapping mountain runoff into Long Draw Reservoir. We had been expecting to find wilderness in La Poudre Pass, so encountering the dam felt like running into a wall in the dark.

The clearcuts, dam and reservoir were grievous wounds, but none of them were as bad as the Grand Ditch. We walked a quarter-mile from the end of Long Draw Road and found a sign marking the location of the river’s headwaters. On our way to the sign, we crossed over a 30-foot deep and 30-foot wide ditch pushing water from west to east. We were on the west side of the Continental Divide, where water naturally flows west, so we contemplated what black magic engineers had employed to achieve this feat. The ditch was as conspicuous in La Poudre Pass as a scarred-over gouge on a child’s face.

© Michelle McCarron

The Grand Ditch was begun in the late 1880s, dug by exploited crews armed with hand tools and risky dynamite. It was built to carry water, diverted from the Colorado River’s headwaters, east to growing cities on Colorado’s Front Range. About two feet of swift water ran through the ditch. Even before melting snowpack forms the tiny mountain streams identifiable as the Colorado River’s origins, water is stolen from her. Pausing in a half-foot of powder, I wondered whether the water stored here would end up on a Fort Collins golf course or stirred by the fins of a vaquita porpoise in the Gulf of California.

I asked theColorado Riverfor the tale of her nativity. She described her birth from a wild womb formed by the oceans, the sun’s consistency, heavy winter clouds, tall mountain peaks and snowpack. She rues that heremergence from this womb led immediately to her exploitation. And the young Colorado River hates the violence that will follow her the rest of her life.

***

In most places, life protects themodern human’s fragile sense of self-importance by veiling the weight of time in the soft accumulation of soil, by disguising the vastness of the universe in the reassuring consistency of an undisturbed horizon and by salving existential angst with a diversity of nonhuman companions. There are places, however, where life refuses to disguise herself and human self-importance disintegrates.

The red rock deserts and canyon lands of southeastern Utah, where we followed the Colorado River, are some of these places. The reality of time, frozen and piled where the land was rent into mesas and plateaus, crashes down on human consciousness where human bones shiver in the shadows and foreshadows are whispered by stones, boulders and the bones of the land.

© Michelle McCarron

She beckoned us south through these lands. She fled through the sheer red rock walls that she sculpted as monuments to her power. She paused, at times, in warm pools, to let the colors of stone reflect from her face and to rejoice in her own beauty. To interpret her work as vanity is to misunderstand; only her creations are worthy of her celebration. The waters flowing through our bodies coursed against our skin and tugged on our veins, yearning to mingle with their kin. We ached with regret for the moment life would necessarily drag us from her banks.

Mesmerized and seeking the confluence of the Green and Colorado Rivers, we got lost in Canyonlands National Park. We failed to reach the confluence, and thus failed to speak with the two rivers. At first, we were angry with ourselves. We ended up hiking close to fourteen miles in seven hours, up canyon walls abruptly rising six or seven hundred feet, through a rainstorm and across canyon floors covered in several inches of loose sand using muscles we forgot we had. We thought we had done it all for nothing. Worst of all, feeling a responsibility to tell the Colorado River’s story, we thought that we had let the river down.

© Michelle McCarron

But the deeper I think about it, the clearer an image of the river, waving through the orange sunshine of a desert dusk, becomes. She seems to smile with the compassionate gleam of a wise elder. “You should have known,” she says. And now I do: We did not simply miss the cairns, lose the trail, and end up five miles south of the confluence and six miles from our cars after sunset. No, we lost more than the trail. We lost our self-importance. And only humility remained.

***

Water is life. But water is also death. Water brings a pleasant taste to the parched tongue, but water also brings stinging numbness to the warm-blooded. Water taken through the esophagus brings hydration. Water taken through the lungs brings suffocation. Water may be disrespected for a time, but the longer the passage of water is hampered, the angrier water becomes. Water has a long memory and, where others forget, water carries pollutants and poisons for decades.

When I think about what it would mean to fully recognize the rights of the Colorado River to exist, flourish, regenerate and naturally evolve, I know the river will demand a reckoning. I know this lyrically and I know this ecologically. Lyrically, the river is full of righteous rage. Ecologically, too many humans have come to depend on the exploitation of the river and the rest of the natural world. The balance that must be achieved will come with profound pain. Humans will die, their lifestyles will be dramatically changed and those who require the gifts of civilization will see those gifts taken.

The black waters of the dammed Blue and Colorado Rivers stroked the Dillon Reservoir walls with their dark thoughts and taught me these lessons. It was several hours after sunset and well below freezing. A certain morbidity rose from the artificial lake and crystallized to hang in the air. Somewhere out of sight, but perilously near, I could feel the stirrings of anger. I sensed that the anger was slow to swell, but irresistible when fully aroused. I was mesmerized by the stars spilling over ripples and by the crescent moon’s silver threads, two nights from new, dancing across the water. In the town of Dillon below, harsh electric lights sparked and crackled with a troubled tension.

The images came unbidden. The first faint crevice appeared in the earth-filled wall. Water hissed as it pushed through. Rivulets appeared as tears rolling down the dam’s face. Then, a series of sharp cracks rang out like the reports of heavy ordnance announcing the onset of battle. Earth and stone blasted away to fall into the valley. Water rushed into Dillon. Poles holding power lines snapped like toothpicks. Chunks of asphalt were ripped up. Automobiles flipped and tumbled like pebbles on a creek bed. Factory outlet stores, gas stations and multistory hotels were washed away.

© Michelle McCarron

The white torrents that cascaded from the broken dam were flecked with joy. The waters retook the Blue River’s original path. The waters from the Colorado, knowing they would never rejoin their mother, were gladly adopted by the Blue. It was all over in a matter of minutes. This sudden demonstration of natural power passed and a quiet peace settled where Dillon once stood. The peace wasn’t without pain. Human bodies floated facedown among the wreckage. The water regretted the deaths, but knew the human bodies would be broken down and used to heal the wounds humanity had created.

As the vividness of the images faded, I was left with the echo of a warning. I recalled all the dams in the Colorado River Basin, all dams everywhere, and I prayed that a peace could be made with the dammed waters of the world.

© Michelle McCarron

***

I have seen the silver sparks of minnows playing under brown stones. I have watched the wind shower gray pools with gold cottonwood leaves. I have been washed away in the vertigo caused by the river’s speed conflicting with the primordial stillness of canyon walls. Arundhati Roy wrote, “Once you see it, you can’t unsee it. And once you’ve seen it, keeping quiet, saying nothing, becomes as political an act as speaking out. There’s no innocence. Either way, you’re accountable.”

I’ll never be able to drive past a dam in the Colorado River Basin and ignore the highly endangered bonytail chub who can no longer visit most of their traditional spawning beds. I’ll never be able to read the billboards praising the peaches of Palisade, Colorado, or the melons of Green River, Utah, without remembering dried up willow forests where the songs of nimble southwestern willow flycatchers have fallen silent. And whenever I close my eyes to recall the Colorado River, that blue ribbon twisting through rocky mountains and red rock canyons, I won’t be able to unsee her suffering.

© Michelle McCarron

As I process the last four months, I’m left with Roy’s brilliant words: I am no longer innocent and it is time to be accountable. Disbeliefs may only be suspended for so long before they slither through slits in the veil separating consciousness and subconsciousness as anxieties. Anxieties, similarly, may only be silenced for so long before they push through lips and teeth as words.

Disbeliefs, anxieties and words, when true, spawn in reality. The reality is that the loss of life on Earth currently outpaces our various resistance movements’ responses. Those in power enforce infinite growth on a finite planet. The planet’s life-support systems are resilient, but they can be pushed beyond their ability to recover. This means there is a deadline. While it is unclear when that deadline will pass, the deadline exists. If we do not stop the assaults on the planet’s life-support systems like the Colorado River, life on Earth may be impossible for a very long time, if not forever. We have little time to waste on ineffective tactics.

Hear the white crash of her torrents on the boulders she drags through the desert, feel the unyielding red rock she pushes through, lose your balance in the impatience of her swift streams, and you’ll know: The Colorado River needs to provide her waters and yearns for her home in the sea.

© Michelle McCarron

In all my time spent listening, I did not hear her speak of a judge’s gavel, of evidentiary proceedings or of the State of Colorado’s motion to dismiss. She cited no precedent, no binding legal authority and no argument made by silver-tongued attorneys. She did not fear questions of jurisdiction or the threat of sanctions.

No, her fears are physical and real. She fears poisonous mercury and too much selenium. She fears climate change causing less and less snow to fall and depriving her of replenishment. She fears dams.

If I could start the lawsuit all over again, maybe I would refuse the interviews, refuse to write the complaint, refuse to write anything at all. Instead, I would insist that you sit on the river’s banks, listening. And if you hear the Colorado River’s rage as she slaps the face of a dam, you’ll know that court orders aren’t the only way dams fall.

© Michelle McCarron

This article and the photos therein are the sole property of Will Falk and © Michelle McCarron and may not be reproduced or republished elsewhere without the explicit permission of the author or photographer.

This article originally appeared at Voices For Biodiversity. VFB is grateful to the Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund (CELDF) for introducing us to Will Falk and Michelle McCarron. CELDF is doing excellent work helping communities fight for nature’s rights and we are honored to collaborate with their team.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Aug 12, 2018 | Human Supremacy

by Boris Forkel / Deep Green Resistance Germany

Dear J.,

Congratulations on your new job!

To be honest, I’ve never understood how people like you can do practically anything for their job, while the whole world around us is burning.

This is not a criticism of your person, but only my attempt to better understand your way of life.

I know you do have some understanding that our entire culture is based on violence and exploitation and destroys all life on the planet. Nevertheless, you do everything to be a functioning part of the machine and to live a “normal” western life.

It must be because we have been socialized in completely different ways. You belong to the wealthy middle class, and they are doing everything to maintain the status quo. They’ll still take the SUV to drive to work when the Baltic Sea is near Bonn.

It must be because they are more separated from the physical world, from the real world, than I am. They have something I never had, namely a world of their own.

It is this bubble of their middle class status that still guarantees them many privileges.

They can afford flights and holidays, they have the power and status to travel to many places in the world, and they always have enough money. The bubble gives them a false sense of security through privileges I’ve never known. They live within this bubble and do not perceive themselves as part of the real physical world around them.

For me, it always was about whether we could afford another pack of noodles or potatoes at the end of the month, or whether we could pay the rent so we wouldn’t get kicked out of the apartment. The apartment that was owned by someone from the middle class, to whom this entitlement and the rent he exploited from us gave exactly this deceptive security.

Because they live in their own bubble of privileges and “security” and not in the real physical world, the destruction, which frightens me terribly, doesn’t frighten them as much, or at least can be accepted much better, because in their perception, it somehow happens outside their own sphere.

I’ve been an outsider from the beginning, I’ve always lived on the edge. The narratives and symbols of this culture have never made any sense to me, because I have seen and experienced relative poverty, oppression and exploitation from the beginning. The pictures of slaughtered whales and the sea of blood I saw in Greenpeace magazines at the age of six stuck in my head forever.

For me, there has never been a status of comfortable “normality.” I‘ve tried for a while to adapt, to become “normal,” but I just could‘t.

I know by now that normality can never exist within this culture based on violence and exploitation.

At least not for me.

But strangely enough – and this is exactly what I find so difficult to understand – the narratives and symbols of this culture still make sense to you affluent middle class, even though you are educated and know that the world is on fire. Somehow you still manage to stay within the system and serve it. And somehow you guys are doing pretty well.

I wonder what it takes to break your “normality,” to get you out of your comfort zone and do things that are not “normal.”

The fact that 90% of fish stocks have disappeared in the oceans is not enough.

The biggest mass extinction in the history of the planet is not enough.

The imminent threat of climate change to all life on planet earth is not enough.

I can‘t help myself, but it keeps me thinking of our recent history, when the good German citizens did everything to preserve “normality.” About 1000 concentration camps in the German Reich and the occupied areas, in which millions of people were systematically industrially slaughtered, were not enough to get the middle class out of their comfort zone.

The (presumably middle class) SS commander in the concentration camp was a loving family man in his spare time.

But the thing is, if the planet is destroyed, it will affect you, too. You too will lose your privileges, because when the planet is destroyed, all of us lose everything.

You too are dependent on clean air, clean drinking water and halfway decent food. This is the absolute truth, even if all other “truths” around us (propaganda, ideology, you name it…) are extremely flexible and can be adapted to the prevailing political system.

I wish you all the best and a good life inside your bubble.

Perhaps we’ll meet some day in hell, when the dystopian nightmare I already live in has destroyed your privileges and your lives, too.

Love & Rage,

Bo

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jul 27, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Introduction to Strategy” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

Despite the limitations created by their smaller numbers, resistance movements do have real strategic choices, from the loftiest overarching strategy to the most detailed tactical level. Let’s explore beyond the default palette of actions. Resisters can and must do far better than the strategy of the status quo.

There is a finite number of possible actions, and a finite amount of time, and resisters have finite resources. There are no perfect actions. Prevailing dogma puts the onus on dissenters to be “creative” enough to find a “win-win” solution that pleases those in power and those who disagree, that stops the destruction of the planet but permits the continuation of business as usual and lifestyles of conspicuous consumption. If resisters fall prey to this belief, if they accept its absurd and contradictory premises, they are engineering their own defeat before the fact. If resisters believe this, they are accepting all blame for the actions of those in power, accepting that the problems they face are theirfault for not being “innovative” enough, rather than the fault of those in power for deliberately destroying the world to enrich themselves.

At the highest strategic level, any resistance movement has several general templates from which to choose. It may choose a war of containment, in which it attempts to slow or stop the spread of the opponent. It may choose a war of disruption, in which it targets systems to undermine their power. It may choose a war of public opinion, by which to win the populace over to their side. But the main strategy of the left, and of associated movements, has been a kind of war of attrition, a war in which the strategists hope to win by slowly eroding away the personnel and supplies of the other side, thus wearing down the omnicidal power structures and public opposition to change more quickly than those forces can destroy our communities, more quickly than they can gobble up biodiversity, more quickly than they can burn the remaining fossil fuels. Of course, this strategy has been an abysmal failure.

A strategy of attrition only works when there is an indefinite amount of time to maneuver, to prolong or delay conflict. Obviously that’s not the case in the current situation, which is urgent and worsening. Furthermore, to achieve success in a war of attrition, the resistance must be able to wear down the enemy more quickly than it gets worn down; again, in the present case, those in power are not being worn down at all (except in the degree to which they are so rapidly consuming the commodities required for their own reign to continue).

Furthermore, a resistance movement fighting a war of attrition must reasonably expect that it will be in a better strategic position in the future than it is at the current time. But who genuinely believes that we—however you would define “we”—are moving toward a better strategic position? And in order to get ahead in a war of attrition, resisters would have to have more disposable resources than their opponent.

Another crucial element in a war of attrition is reliable recruitment and growth. It doesn’t matter how many enemy bridges a group takes out if the adversary can build them faster than they can be destroyed. And on every level, civilization is recruiting and growing faster than resistance forces. To keep pace, resistance fighters would have to destroy dams more quickly than they are built, get people to hate capitalism faster than children are inculcated to love it, and so on. So far, at least, that’s not happening.

Of course, we are not in a two-sided war of attrition. Those in power aren’t holding back, but have been actively attacking. And those in the resistance haven’t even been fighting a comprehensive war of attrition; it’s more like a moral war of attrition. Rather than trying to erode the material basis of power, we’ve been hoping that eventually they’ll run out of bad things to do, and perhaps then they’ll come around to our way of thinking.

A movement that wanted to win would be smarter and more strategic than that. It would abandon the strategy of moral attrition. It would identify the most vulnerable targets those in power possess. It would strike directly and decisively at their infrastructure—physical, economic, political—and do it while there is still a planet left.

Strategy and tactics form a continuum; there’s no clear dividing line between them. So the tactics available, which will be discussed in the next chapter, Tactics and Targets, guide strategy, and vice versa. But strategy forms the base. If resistance action is a tree, the tactics are spreading branches and leaves, finely divided and numerous, while the strategy is the trunk, providing stability, cohesion, and rootedness. If resisters ignore the necessity and value of strategy, as many would-be resistance groups do—they are all tactics, no strategy—then they don’t have a tree, they have loose branches, tumbleweeds blowing this way and that with changing winds.

Conceptually, strategy is simple. First understand the context: where are we, what are our problems? Then, develop the goal(s): where do we want to be? Identify the priorities. Now figure out what actions are needed to get from point A to point B. Finally, identify the resources, people, and specific operations needed to carry out those activities.

Here’s an example. Let’s say you love salmon. Here’s the context: salmon have been all but wiped out in North America, because of dams, industrial logging, industrial fishing, industrial agriculture, the murder of the oceans, and global warming. The goal is for the salmon population not only to stop declining, but to increase. The difference between a world in which salmon are being wiped out, and one in which they are thriving, comes down to those six obstacles. Overcoming them would be the priority in any successful strategy to save the salmon.

What actions must be taken to honor this priority? Remove the dams. Stop industrial forms of logging, fishing, and agriculture. Stop the massive production and dumping of plastics. Stop global warming, which means stop the burning of fossil fuels. In all these cases, existing structures and practices have to be demolished for salmon to survive, for the goal to be accomplished.4

Now it’s time to proceed to the operational and tactical side of this strategy. According to the US Army field manual, all operations fit into one of three “all encompassing” categories: decisive, sustaining, or shaping.

Decisive operations “are those that directly accomplish the task” or objective at hand. In our salmon example, a decisive operation might be taking out a dam or preventing a clear-cut above a salmon spawning stream. Decisive operations are the centerpiece of strategy.

Sustaining operations “are operations at any echelon that enable shaping and decisive operations” by offering direct support to those other operations. These supporting operations might include funding or logistical support, communications, security, or other aid and services. In the salmon example, this might mean providing transportation to people taking out a dam, bringing food to tree-sitters, or helping to research timber sale appeals. It might mean running an escape line or safehouse, or providing prisoner support.

Shaping operations “create and preserve conditions for the success of the decisive operation.” They alter the circumstances of the conflict and help bring about the conditions required for victory. Shaping operations could include carrying out a campaign on the importance of removing dams, undermining a particular logging company, or helping to develop a culture of resistance that values effective action and refuses to collaborate. However, shaping operations are not necessarily broad-based or indirect. If an allied underground cell were to attack a nearby pipeline as a distraction, allowing the main group to take out a dam, that diversionary measure would be considered a shaping operation. The lobby effort that created the Clean Water Act could even be considered a shaping operation, because it helps to preserve the conditions necessary for victory.

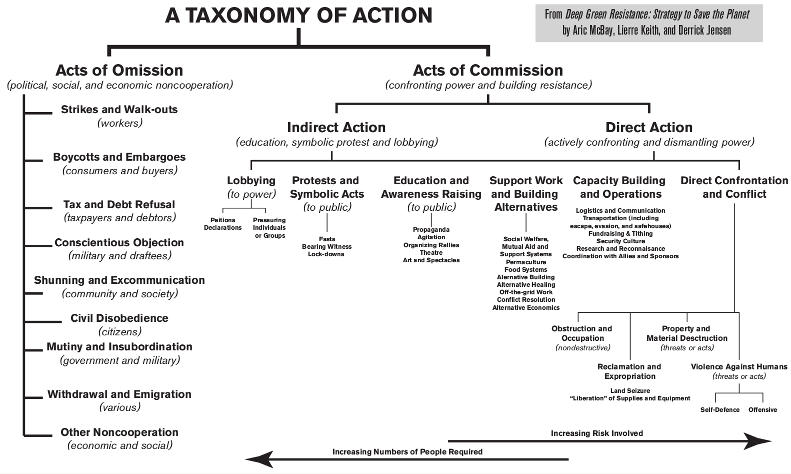

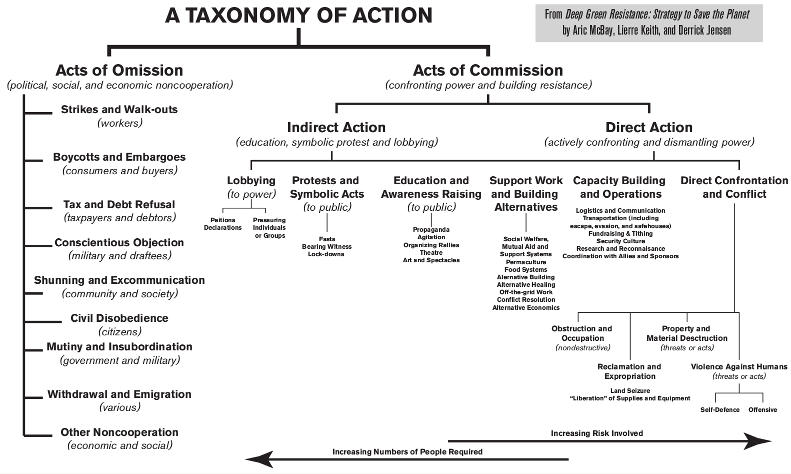

If you review the taxonomy of action chart, you’ll see that the actions on the left consist mostly of shaping operations, the actions along the center-right consist mostly of sustaining operations, and the right-most actions are generally decisive.

Click for larger image

These categories are used for a reason. Every effective operation—and hence every effective tactic—must fall into one or more of these categories. It must do one of those things. If it doesn’t—if that operation’s or tactic’s contribution to the end goal is undefined or inexpressible—then successful resisters don’t waste time on that tactic.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jun 11, 2018 | The Problem: Civilization

Editor’s note: This is the second part of an edited transcript of a talk given at the 2017 Public Interest Environmental Law Conference. Read Part One here. Watch the video here.

by Erin Moberg, Ph.D., and Max Wilbert / Deep Green Resistance Eugene

A question that a lot of radical environmentalists ask ourselves is, “where is your threshold for resistance?” Particularly given the recent U.S. presidential election, people in so many communities with a lot at stake, with a lot to lose, and not a lot of choice, have been doing much of the harder and riskier work as front-line activists.

Latinos are taking action in courts, schools, and town halls. Women of color are taking action, black and brown people are taking action, and indigenous people are taking action. Since the U.S Presidential election it has been good to see other people with less to lose take steps, and sometimes leaps, out of the spaces of privilege they occupy in order to stand up and speak up against injustice–against violations of people of color, of women and girls, of Spanish-speakers, of immigrants, of undocumented people, and so many others.

In Eugene, Oregon, I’ve also seen many people new to activism come out to learn about direct action and community organizing, because they want to defend the land they love, but a lot of times don’t know how.

This gives me brief moments of hope and yet I’m still terrified, and still very certain that nothing short of a unified global movement of all kinds of people ready to resist and fight back, to protect the land they love, the air we breathe, the water we need, and all of the animals on the planet, will be enough to give us any say at all in how and when this culture collapses.

Some of the ramifications of environmental activists and movements dedicating themselves to promoting energy efficiency include strengthening the existing culture, i.e., industrial civilization, by correcting contradictions that stand out between ideals and practices, or policy and practices, within the dominant culture.

This also provides an unproductive outlet for activist revolutionary anger that only serves to pacify us and detract us from more materially impactful work that we could be doing as activists. Thinking about the global crises that we are currently facing, including deforestation, peak oil, water drawdown, soil loss, food crises, overfishing, desertification are often framed in the media and in popular and academic discourse as disparate or coincidental issues.

We know, however, that all of these crises are interrelated. These are some of the ways in which we can collectively characterize these crises:

- They are progressive – they are rapid, but not instant, which can lead to what is called “shifting baseline syndrome.” That is, we get accustomed to a new norm, a new kind of way of living, and we lose sight of a previous issue like destruction of forests or water drawdown.

- These crises are non-linear, runaway or self-sustaining, they have long lead and lag-times, which really impedes any kind of activism that’s focused on long-term solutions or long-term planning.

- They have a deeply rooted momentum and they are industrially-driven, and they benefit the powerful, and cost the powerless.

- They often yield temporary victories, but permanent losses, particularly losses to the planet.

The proposed solutions to these crises often make things worse, as in the case of energy efficiency measures. Here is quote by Aric McBay that really resonates with me. In the book “Deep Green Resistance” he writes:

Even though analysts who look at the big picture globally may use large amounts of data, they often refuse to ask deeper or more uncomfortable questions. The hasty enthusiasm for industrial biofuels is one manifestation of this. Biofuels have been embraced by some as a perfect ecological replacement for petroleum. The problems with this are many, but chief among them is the simple fact that growing plants for vehicle fuel takes land the planet simply can’t spare. Soy, palm, and sugar cane plantations for oil and ethanol are now driving the destruction of tropical rainforest in the Amazon and Southeast Asia…This so-called solution to the catastrophe of petroleum ends up being just as bad—if not worse—than petroleum.

Let’s look at some traits of ineffective solutions:

- Ineffective solutions tend to reinforce existing power disparities. These solutions tend to be based on capitalism as a guiding principle and goal. Anything that has as its primary goal to increase productivity, to make more money, is necessarily going to be an ineffective solution when it comes to the health of the planet.

- These solutions suppress autonomy or sustainability that impede profit. For example, suggestions of voluntary changes for corporations to undertake are not going to be carried out, because it doesn’t serve their best interest, which is to increase their profit, to make more money.

- They rely on techno-fixes, or technological and political elites. For example, photovoltaic solar panels, which in the process of creating them uses more energy and causes further environmental harm.

- They encourage consumption and increasing consumption and population growth.

- They attempt to solve one problem without regard to the interconnected problems. “Solving” the energy crisis with corn-derived ethanol destroys more land and causes water drawdown, with a very low yield of ethanol.

- They involve great delay and postpone action. A good example of this is the Paris Climate Accords. Every day, the gap between human population and the earth’s carrying capacity increases. The goals are set for 2025 or 2050–by the time we even get there, that gap will be exponentially greater.

- They tend to focus on changing individual lifestyles, such as buying more efficient light bulbs. This consumer deception: if you buy more of the right things, you can save the planet.

- They tend to be based on token, symbolic, or trivial actions. For example, an activist group acknowledges the problem of industrial civilization, but then the only action they take is to sign a petition, or to grow their own food. Those things might be great things for individuals for consciousness-raising, finding community, and expressing ourselves, but they are very disconnected from the material impact of civilization on the planet.

- They tend to be focused on superficial or secondary causes, like overpopulation instead of over-consumption. For this particular point, it also tends to be a very racist approach in looking at how to save the planet, because the blame tends to be put on indigenous and brown and black communities who have the most to lose, and the least control over this system of empire.

- Finally, these ineffective solutions tend to not be consonant with the severity of the problem, the window of time available to act, or the number of people expected to act.

Let’s talk a little bit about what effective solutions could look like. Effective solutions need to address root problems with global understanding. We need to acknowledge the interconnected aspect of all of these crises that are occurring around the planet.

Effective solutions involve a higher level of strategic rigor. But they also enable many different people to address the problem and ask themselves what they’re able to risk, what they can offer. Can you risk your body, can you risk your family, can you risk your job? Or not? It is necessary to locate our position on that spectrum and figure out how we can best use our skills to end the crisis.

Effective solutions are suitable to the scale of the problem, the lead time for action, and the number of people expected to act. If you know you need 25 people to pull off a blockade of a coal train and you don’t have 25 people, then plan a different action. Be realistic.

Effective solutions tend to involve immediate action and long-term action planning, make maximum use of available levers and fulcrums (planned to make as big of an impact as possible), playing to the strengths of the people involved, and targeting the weaknesses of the system.

Finally, they must work directly and indirectly to take down civilization, which is the overall goal. This leads to a discussion of another obstacle to effective solutions: the conflict between reformist and revolutionary perspectives.

Reformists, those who advocate for change through reform, tend to consider the existing system as functional but flawed, and believe it can be modified to address the issue at hand.

Reformists tend to be willing to employ legal and socio-politically sanctioned approaches to changing the system or addressing the problem, like legislations, petitions, grassroots organizing. Reformists also tend to focus on separate issues.

There are some limitations to this. A reformist focuses on correcting contradictions within the system, and thus redirects revolutionary anger to less materially-impactful solutions. On the other hand, both revolution and reform can have a place in the type of activism that leads to effective solutions.

Revolutionists consider the existing system to be the root of the problem, and believe that it must be dismantled and replaced. Revolutionists are willing to employ resistance strategies through whatever means are most effective. Rather than working within a particular legal framework, revolutionists are willing to employ strategies that may or may not be legal toward the goal of saving the planet.

Revolutionists see this system, this culture as the primary issue. We advocate that those working toward reform and those working toward revolution, or anywhere within that spectrum, identify points of overlap in their goals and strategies, in order to better work together.

This might look like activists who utilize legislative channels to prevent the shipment of fossil fuels through their municipality, while front-line activists block coal trains and offer direct action training for others to do those same actions.

What do we mean by fighting back? We mean thinking and feeling for ourselves, finding who and what we love, figuring out how to defend what we love, and using any means necessary and appropriate. This involves calling out the problem, in this case the dire circumstances caused by industrial civilization for life on the planet; identifying the goal, for example, depriving the rich and powerful of the ability to destroy the planet, and defending and rebuilding just and sustainable human communities within repaired and restored landbases.

In our communities and around the world, great people are doing great work in the name of saving the planet. More people are marching in protest than before, more people are writing letters, signing petitions, making calls, and organizing at the grassroots level. More people are seeing clearly, and more people are learning the language to speak about what they see.

And yet, more animals go extinct every day, and more areas of the earth become uninhabitable for so many animals, including humans. The salmon are dying, the forests are dying, the rivers are dying, the oceans are dying, and people are dying, all around the world, because of industrial civilization.

Since the last US presidential election, more people are speaking out about the climate crisis through social media, in town halls, in their homes, in neighborhoods and schools. And yet, the earth’s temperature rose again last year, and the Bramble Cays Melomys went extinct due to climate change last year. So did the San Cristobal Vermillion flycatcher.

San Cristobal Vermillion flycatcher

The Rabb’s Treefrog went extinct. And the Stephan’s Riffle Beetle. And the Tatum Cave Beetle. And the Barbados Racer Snake. And 13 more bird species went extinct. And the list goes on.

As environmental activists, we know what is at stake: all life on the planet. We know, too, that an environmental and cultural movement grounded in energy efficiency is, simply put, not enough, and often incites further planetary harm. I’d like to read a quote by one of my favorite writers and thinkers, Rebecca Solnit, a writer, feminist, philosopher and activist:

Our country is now headed by white supremacist nativist misogynist climate-denying nature-hating authoritarians who want to destroy whatever was ever democratic and generous-spirited in this country, meaning that it’s a good time to not let the perfect be the enemy of the good, to keep your eyes on the prize, and to commit to the long term process of taking it all back. Because even after Trump topples, which could happen soon, remaking the stories and the structures is a long term project that matters. It is not ever going to finish, so you can pace yourself, celebrate milestones and victories, and get over any idea of arrival and going home. Most of the change will be incremental, and the lives of most great changemakers show us people who persisted for decades, whether or not the way forward looked clear, easy, or even possible.

This is also a remarkable moment in which many people you and I might have disagreed with in safer times are also horrified, are allies in some of the important work to be done, and worth reaching out to to find what we have in common. “The word emergency comes from emerge, to rise out of, the opposite of merge, which comes from mergere: to be within or under a liquid, immersed, submerged. An emergency is a separation from the familiar, a sudden emergence into a new atmosphere, one that often demands we ourselves rise to the occasion.” This is an emergency. How will you emerge?

We will leave you with a brief analysis of a poem by Adrienne Rich, the poet, essayist, and radical feminist who died just a few years ago. This poem is called “North American Time” and it’s taken from a collection published in 1986, in which she argues for a kind of ethical imagination, that I think applies to our argument for moving beyond energy efficiency, towards the end of halting climate change and the destruction of the planet.

The poem begins as the speaker, a woman of color, reflects on her growing realization of having been systematically silenced and pacified by the culture of empire:

When my dreams showed signs

of becoming

politically correct

no unruly images

escaping beyond border

when walking in the street I found my

themes cut out for me

knew what I would not report

for fear of enemies’ usage

then I began to wonder…

She goes on to describe the power and permanency of written words, and of the verbal privilege in being able to write, or to act, in a public, enduring way. In the third section, she challenges the reader to do the impossible: to imagine herself outside the context of history, of planetary life, of accountability.

try telling yourself

you are not accountable

to the life of your tribe

the breath of your planet

It doesn’t matter what you think.

Words are found responsible

all you can do is choose them

or choose

to remain silent. Or, you never had a choice,

which is why the words that do stand

are responsible

and this is verbal privilege.

Here and throughout the poem, Rich calls out the silent bystander, the privileged witness who sees and knows that great injustice is being perpetrated, and yet doesn’t speak, doesn’t act, doesn’t intervene. Central to this poem is Rich’s profound understanding that words, rather than thoughts, are ultimately found responsible. I think the same holds true for actions in the context of environmental activism.

Our actions will be what endure, not the thoughts we had, or the plans we made, or the feelings we had about the destruction of the planet. Also central to this poem is Rich’s compelling portrayal of the disjuncture between those who have a choice, the more privileged, and those who don’t.

As activists, we need to first understand our own relative privileges and then acknowledge that being male; being white; being an English-speaker; being a citizen; being wealthy, are not innate. They are a direct result of the culture of empire, of a culture grounded in institutionalized racism, misogyny, and omnicide.

The salmon, who have all but disappeared, didn’t have a choice. The Kalapuya, whose land we occupy here today, didn’t have a choice. The forests don’t have a choice, nor the bees, nor the rivers.

What choices do you all have? We encourage all of you to reflect on these words as a call to action, as a call to re-evaluate the words we use, and the stances we take, to assess whether or not they truly coincide with our deepest, most intimate hope for the future of ourselves, of the planet, and of this world.

We ask all of you to think long and hard about how you would like to emerge, and then we ask you to act, in a way that feels intentional and possible, and significant to you, and most importantly, for all life on this planet.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | May 4, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

by Boris Forkel / Deep Green Resistance Germany

Capitalism reaches fulfillment when it sells communism as a commodity. Communism as a commodity spells the end of revolution.

—Byung-Chul Han

I’m a permaculturalist. And I became a permie in the first place because I wanted to break free from this culture.

To me, permaculture was and still is highly political. “Permaculture is revolution disguised as gardening” is one of my favorite Bill Mollison quotes.

After all, what freedom can we have without subsistence, without having control over our most basic resources, our own food? “There is no sovereignty without food sovereignty,” said Native American activist John Mohawk.

I’ve been so ardent and naive. I thought that the permaculture-approach is so ingenious that it would become a mass-movement, indeed a quiet and peaceful revolution. It would free us from being dependent on the digital food they sell us in grocery stores nowadays, and from the wage economy at the same time, because we would build small, local food cooperatives that would all be sharing the surplus.

Unfortunately, time and experience shows that it’s not that easy.

One of my permaculture teachers, who taught me the concept of the food forest, often said: “I don’t understand what’s the problem for all these critical people. Nowadays, we have all the freedoms we want.” He also articulated a very strange notion about the future: “Once we have reached the number of 10 billion, human population growth will come to a halt. Thanks to Internet technology, humans will then all be connected and serve as the consciousness of planet earth.” Attendants hung on his lips when he said that, and while everybody else was amazed by this perspective of a golden future, I sat quietly, stunned.

I knew in my heart that he was wrong, but couldn’t articulate a sufficient answer to his statements back then.

It made me angry. How can one say that “we have all the freedoms we want,” while the air we need to breathe is being polluted, the greatest mass extinction in planetary history is happening, the climate is being destroyed, the oceans are vacuumed and filled with toxic garbage? In short: when the most basic functions of our planet to support life are being destroyed?

What about the freedom of having breathable air? What about the freedom of having a livable planet? What about the freedom of having a future?

I’ve given a lot of thought to his statements ever since, because they seem so appealing to many people. The Earth never supported more than 2 billion humans until Fritz Haber and Robert Bosch indeed broke the planetary boundaries with the invention of the Haber-Bosch process. Nowadays, we are hopelessly overpopulated. So the number of 10 billion is purely random and nothing but magical thinking. The notion of Internet technology and humans as the consciousness of the planet is nothing more than a new fashion of the good old ideology of humans as the crown of creation. What about nature in this fantasy? With 10 billion (industrial) humans, there will hardly be anything left.

Everybody with a sane mind and a little understanding—especially a permie—should know that the trees, the fungi, the soil, the air, the water, the animals and so on, in short what we call nature, indeed is the consciousness of planet earth. Apparently, the manifest destiny of the technocrats is to eradicate what they perceive as primitive, raw, red in tooth and claw, wild and uncontrollable, and to replace nature with a “better” system of human technology.

Deconstructing that was the easy part. The hard part is his statement about freedom. With all this in mind, the primary question is: what does freedom mean for someone like him?

A friend of mine, who was lucky enough to hear Noam Chomsky speak live, told me that in the discussion after somebody asked the usual question: “What can we do about it?” Chomsky responded that he thinks this is a strange question. People from so-called developing countries would never ask such a question, only westerners, he stated. Apparently, third-world-people still have a clearer sense for suppression and cultures of resistance. “We should rather ask what we can’t do,” Chomsky said.

When I attended a talk by Rainer Mausfeld, of course someone asked the very same question. Mausfeld stated that this question shows how well the soft power techniques he’d been describing work. We can’t even imagine any form of resistance.

For more than a century, the political left’s analysis has been very clear: The suppression and exploitation of the poor (working class) by the rich (owning class), that is the very basis of capitalism, can only be solved by organized class struggle to come from the working class. This concept isn’t hard to understand. It is classic Marxism. But somehow, the ruling class has managed to completely eradicate it from the proletarian minds.

I’ve come across a lot more of what I like to call liberal lifestyle-activists. I understood that most permies chose permaculture not because they want a revolution (like I did), but because they want a more sustainable lifestyle for themselves. They believe that they are free, because they perceive their individualism and their freedom of choice as the greatest freedom, the greatest achievement of modernity. Being part of any group, class or movement is perceived as regressive. The notion of class struggle is so yesterday.

At the same time, they’re usually educated people, and they know that a lot of things are going badly wrong. But as liberals who are taking power out of the equation, and individualists lacking any concept of social group our class, they must take it all on themselves. “It is all of us who are causing the destruction,” they’d say.

As a result, the only thinkable form of political action are personal consumer choices. Buy organic soap and feel better.

A great example of this are vegans. No doubt that factory farming is horrible and has to stop. But as a lifestyle-activist, all you can do about it is to stop consuming meat. In your worldview, the problem can only be solved by everybody stopping eating meat.

For liberal lifestyle-activists, “having all the freedoms we want” can only mean the freedom to consume (or not consume) whatever we want, whenever we want, in any quality and quantity we want. This is the kind of “freedom” with which capitalism has hijacked us. If we can afford it, of course. But within neoliberal capitalist ideology, there is no such thing as a suppressed class. The poor are poor because they don’t work hard enough, or they are simply to stupid to sell themselves well enough.

“Neoliberalism turns the oppressed worker into a free contractor, an entrepreneur of the self. Today, everyone is a self-exploiting worker in their own enterprise. Every individual is master and slave in one. This also means that class struggle has become an internal struggle with oneself. Today, anyone who fails to succeed blames themselves and feels ashamed. People see themselves, not society, as the problem.”

Byung-Chul Han

For radicals, the question remains: Without the possibility of mass movements, how do we stop the destruction of the planet that is our only home?

For a new generation of serious activists who are tired of all that shit and ready to take action, DGR has the Decisive Ecological Warfare strategy.