Review of the Film Bright Green Lies

Editor’s note: Civilization is in free fall, and most people do not accept that. Humans will have to use a lot less energy. That future is hard for people to grasp. They will need to adjust their expectations of how reality is going to look. This will require going through the stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining(excuses), depression, and acceptance. We can still create social relations that can improve the world through policy and interactions. Remember the win is always in the movements struggling together with others toward those victories, the fighting against the fascism of industrial civilization.

By Paul Mobbs, The ‘Meta-Blog’, issue no.14, 7th May 2020

Being ‘well known’ in eco-circles, you sometimes get strange, often unsolicited stuff arriving in your inbox. This, however, was something I’d been hoping for: A chance to view, and thus review, ‘Bright Green Lies’ – Julia Barnes’ new documentary about the environmental movement and its support for renewable energy.

‘Planet of the Humans’ (PotH) was entertaining. At a general level, it was factual, albeit a polemic expression of those points. But its protracted period of production meant that it lacked coherence, and thus left itself open to easy criticism.

Those criticisms when they came, however, fell directly into the lap of the central argument of the film: That mainstream environmentalists distort facts to promote an erroneous vision of the measures necessary to ‘save the planet’.

It wasn’t just Josh Fox, backed by green entrepreneurs, engaging in a cavalier reshaping of facts and quotations to blacken the name of the film. Our own George Monbiot engaged in his own well-honed distortion of fact and quotation via The Guardian (symbolic of a number of their recent failures) in order to try and prevent people from watching the film on this side of the pond.

‘Bright Green Lies’ is very different: Like PotH, once again it presents the personal viewpoint of the director, Julia Barnes. Unlike PotH, though, it has a very different tone, building upon the immediacy and well-researched content of the eponymous book by Derrick Jensen, Lierre Keith, and Max Wilbert – all of whom appear in the film.

You get the core of the film’s argument over the first five minutes, as the four main protagonists set out their respective take on the ‘bright green’ position [time index in the film is shown in brackets]:

Barnes: “People rarely question the solutions they are taught to embrace, but with all the world at stake we must start asking the right questions. There is a push for a 100% renewable world, and after the research I’ve done for this documentary, I want no part of it. I did not become an environmentalist to protect my way of life or the civilization in which I live. I did it because I am in love with life on this planet and because the world I love is under assault. This film is for those whose allegiance is with the living world. Those who would do whatever it takes to defend it.”[02:26]

Jensen: “You will have hundreds of thousands of people marching in the streets of Washington, or New York, or Paris; and, if you ask those individuals ‘why are you marching?’, they will say, ‘we wanna save the planet’. And if you ask them for their demands they will say, ‘We want subsidies for the wind and solar industry’. That’s extraordinary. I can’t think of any time in history when any mass movement has been so completely captured and turned into lobbyists for an industry.”[03:49]

Keith: “The environmental movement used to be a very impassioned group of people who cared very deeply about the places we loved and the creatures we loved. What happened, though, in my lifetime, was that this movement which was so honorable and impassioned, it turned into something completely different. And now it’s about protecting a destructive way of life, while it destroys the creatures and the places we love. It’s all become, ‘how do we continue to fuel this destruction?’ as if the only problem was that we were using oil and gas.”[03:16]

Wilbert: “The natural world isn’t really part of the conversation anymore. Kumi Naidoo, the former head of Greenpeace, I was watching him being interviewed the other day. He was saying, ‘The planet’s going to survive, the oceans are going to survive, the forests are going to survive, it’s really about can we save ourselves or not’. And I just saw that and I’m thinking, what the hell are you saying? … This is someone who’s considered to be one of the top environmentalists in the world and he’s say- ing we don’t have to worry about the forests or the oceans? I mean, that just betrays a complete lack of empathy and connection to the natural world. I don’t know how you could possibly say that when we’re in the midst of the Sixth Great Mass Extinction, and it’s being caused by industrial culture. It’s being caused by the same institutions, the same economies, the same systems, the same raw materials, the same extractive mindset, that is being used for these renewable energy technologies.”[04:36]

Environmentalism is a ‘class’ issue

My introduction to ‘environmentalism’ started before I’d seriously heard the word; growing up in a semi-rural working-class family who grew their own food, kept chickens, and foraged. Likewise, coming into contact with ‘mainstream’ environmentalism in the mid-1980s introduced me to the concept of ‘bright green’ before I’d heard that term either.

If there’s one general criticism I have (in part because the book, too, glosses over it), it is the failure to explore the class bias of environmentalism. It is dominated by the middle class (and in the UK, led by the upper-middle class); and so the economically ‘aspirational’ middle-class values suffuse its agenda. That’s overlooked in the film.

That this movement should innately favor individualist materialist values, over communal or spiritual ones, should therefore be of no surprise. That does not condemn these groups, or render them incapable of change. What it makes them do is reflect a narrow focus on both concerns and solutions. More importantly, in a mass political society, it makes it difficult for them to have empathy with a large majority of the public – and that hampers their ability to make change.

That bias towards affluence informs their ideological values, which in turn have come to dominate contemporary environmentalism. As said in the film:

“Bright Green Environmentalism is founded on the notion that technology will solve environmental problems; and that you can, through 100% recycling, through wind and solar power, have an industrial economy that does not harm the planet. Deep ecology is the belief that we need to radically change the way society functions in order to be sustainable.”[05:30]

The spectre of this early ideological differentiation has haunted the movement. Just as Keith outlines, for me it became evident around 1988 to 1990. Figures such as Jonathon Porritt and Sara Parkin sought to divest the movement of its ‘hairshirt’ image and put it on a ‘professional’ footing. As a self-acknowledged ‘fundo’ (the pejorative term used for deep green ‘fundamentalists’ in the Green Party at that time) that didn’t enthuse me one bit.

That ‘professionalised’ approach (for which, read compromise with neoliberal values) would slowly percolate through the movement over the next decade. And with it, the compromise that has stalled more radical responses to ecological issues ever since. That failure has, in part, only escalated these historic internal tensions – tensions that this film, almost certainly, will inflame.

First ‘green consumerism’, and then ‘sustainability’, foundered on the reality that the movement’s role as a ‘stakeholder’ in government and industry programs produced little change. Today, the issue at the heart of this internecine contention is renewable energy – and whether it is a realistic response to the Climate Emergency or just another distracting ruse.

I think this film is a good contribution to that contemporary debate. If only to make many people aware that this debate exists, and so cause people to look at the academic research in more detail.

As Barnes succinctly put it: “We are told that we can have our cake and eat it too.”[01:59] And yes, this really is all about cutting the ‘cake’ of affluence. But the film’s criticism of consumerism was couched in a generic “we”, and therein lies its failing.

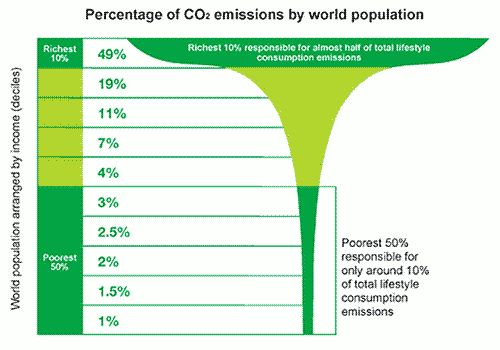

When it comes to consumption it is not an issue of ‘we’. It is about how an extremely narrow social and economic elite exploit the majority by giving them the ‘illusion of affluence’. Albeit one that is today precariously founded upon deepening debt and doubtful economics (a ‘deep’ issue in-and-of itself).

By not making the case that it is a highly privileged minority causing/benefiting from ecological destruction (see graph below), the film and book miss the opportunity to state arguments such as:

- The most affluent 10% of the global population (OK, that’s mostly us!) cause half the pollution;

- But even within these most affluent states, national inequality means wealthy households emit far more pollution than the poorest;

- Hence pollution is absolutely associated with economic inequality and consumption; and,

- That this skew means the most affluent states must reduce consumption by perhaps 90%!

“The ocean is the foundation of life on this planet. The fact that we’re losing it at the rate we are is alarming. I think part of the reason we’re failing is that we ask what is politically possible more often than we ask what is necessary.”[41:37]

Simple logic demands that this minority urgently change their lifestyle, lest the majority, threatened by ecological breakdown, seek to rest it from them. It is how they do this which is another live issue. Frankly, that’s not going too well right now:

Currently, Western states are seeking to repress protests against the climate emergency, to forestall calls for more radical change; While at the same time, billionaires create bunkers in remote locations to survive any future backlash from the dispossessed majority. This creates a powerful incentive for the ‘impoverished majority’ to rest control away from the economic elite driving ecological breakdown. The reality is, though, neither Greenpeace, WWF, nor even Extinction Rebellion, are likely to pick up that banner any time soon. Their failure to recognise affluence as a driver for ecological destruction negates their ability to act to stop it. Instead tokenis- tic measures, like renewable energy, supplant calls for meaningful systemic change.

Economics versus ecological limits

About halfway through, Max Wilbert elucidates a truth that doesn’t get nearly enough exposure:

“When people talk about 100% renewable energy transition to save the planet, to save civilization, what they’re actually talking about is sustaining modern high-energy ways of life, at the expense of the natural world.”[26:38]

I’m sure a number will recognise that from many of my previous workshops. In fact, I’ve just had a Facebook post blocked for, ‘violating community standards’. The offense? It linked to a summary of the research making this same point, and it’s not the first time that’s happened. It’s a touchy subject!

In 2005, my own book, ‘Energy Beyond Oil’, visited many of the issues explored in the film/book. In far less detail though, as there was nowhere near the quantity of research evidence available back then. What that also highlights, though, is how over the interim: ‘Bright green’ environmentalism has been unable to comprehend the message from this new research; while at the same time deliberately deflecting people’s attention towards points of view which have a questionable basis for support.

On that point, I think Max Wilbert gives a most eloquent view for how mainstream environmental- ism sold itself on the altar of green consumerism:

“They want us to believe that consumer choices are the only way we can change things. But if we accept that then it means that they’ve won because we’re defining ourselves as consumers…I have to buy things within this culture to survive, and that is not something that defines me or my power as an actor in this world. I would say much more fundamentally I am an animal. I have hands. I have feet. And I can walk places. And I can do things. And I have a voice. And I have the ability to speak with people and build a relationship with people. And I have the ability to organise. And I have the ability to fight if need be. These are all much more important than my ability to buy or not buy something.”[48:28]

Since ‘Planet of the Humans’, many on the ‘bright green’ side of the aisle have learned a lesson. Their hysterical condemnation of the film, to the point of calling for it to be banned, only served to feed it greater publicity, ensuring more would see it.

Their lack of response this time is perhaps also due to how well the film exposes the fragility of their arguments. One of the bright points in the film was the way in which ‘deep green’ criticisms were dove-tailed alongside interviews with those they criticised – amplifying the substance of the disagreement be- tween each side.

I think my favorite was the segment on Richard York’s research, showing that growing renewable energy actually displaces a very minimal level of fossil fuels. When York’s point was put to David Suzuki, his reply, which I too have often received, was, ”So what is the conclusion from an analysis like that, we shouldn’t do anything?”[24:08]

The film brilliantly explodes this false dilemma. When pushed, about needing to tackle things systemically rather than just trying to influence behavior, Suzuki’s response was, “Yeah, there’s no question our major impact on the planet now, not just in terms of energy, is consumption. And that was a deliberate program…”[24:26]

When it comes to the ‘liberal’ solutions to the climate crisis generally, I think Lierre Keith gives the most perceptive criticism of the simplistic, ‘bright green’ arguments for change[1:03:23]:

“[Capitalism] takes living communities, it converts those into dead commodities, and then those dead commodities are turned into private wealth. And a lot of people think, well, if we just make that into public wealth, we all could get an equal piece of the pie, that’s the solution. The problem is that’s not go- ing to be a solution because you’ve still got the first two parts of that equation. Why are we taking the living planet and turning it into dead commodities? That’s the problem…It’s the fact that rivers, and grasslands, and forests, and fish, have been turned into those dead commodities, that’s the problem.”

Jensen then bookends Keith’s point with another, straightforward invalidation of the basic premise of the bright green approach[1:04:33]:

“What do all the so-called, ‘solutions’, to global warming have in common? They all take industrial capitalism as a given, and so conform to industrial capitalism. They’ve switched the dependent and the independent variables. The world has to be primary, and the health of the world has to be primary because without a world you don’t have any economy whatsoever. And the bright greens are very explicit about this. What they’re trying to save is industrial capitalism, industrial civilization. And that’s my fundamental beef because what I’m trying to save is the real world.”

Climate inequality meets decolonialism

Jensen makes an interesting observation towards the end of the film:

“The thing that blows me away is the lengths that people will go to avoid looking at the problem. That they will create all these extraordinary fantasies in order to do something that’s not going to help the planet so they can avoid looking at the real issue. Which is that industrial civilization itself is what’s killing the planet.”[59:40]

Likewise, Barnes astutely characterises the basic block to progress toward the near end:

“Bright green environmentalism has gained popularity because it tells a lot of people what they want to hear. That you can have industrial civilization and a planet too. It allows people to feel good about maintaining this destructive way of living and to avoid asking hard questions about the depth of what must be changed.”[1:05:04]

For me, though, it was Keith’s discussion about what it is ‘civilization’ is based upon[1:00:02] which brought a long overdue argument into circulation: Criticism of the ‘resource island’ model for the modern city, and its inherent link to the global expropriation and exploitation of land. Driven by the wealthiest ‘city’ state’s need to maintain consumption, the inherent ‘neocolonial’ aspects of international climate negotiations are something the climate lobby too often overlook. Especially in relation to issues such as carbon offsets, the global allocation of carbon budgets, and their inherent global inequality.

At some point environmental groups must call ‘bullshit’ on these whole neocolonial proceedings, and start giving equal value to all humans, irrespective of their present-day privilege. More importantly, we have to give ecological capacity, currently occupied by human societies, back to natural organisms to allow them sufficient space to live too.

Before ‘Bright Green Lies’ turned up, I had just seen Raoul Peck’s excellent, ‘Exterminate All The Brutes’. Coming to the end of ‘Bright Green Lies’, what startled me was how the two films arrived at a very similar place. Both showed similar blocks toward acceptance of the radical change required, around both ecological change and decolonialism.

To understand Peck’s film it helps to have read, ‘Heart of Darkness’. In structuring the film around the characters in that book, and contrasting it to The Holocaust, Peck shows how indifference to European and US colonialism enabled The Holocaust to take place [Episode 4, 46:57 to 54:11]:

“It is not knowledge that is lacking… The educated general public has always largely known what atrocities have been committed and are being committed in the name of progress, civilization, socialism, democracy, and the market…At all times, it has also been profitable to deny or suppress such knowledge… And when what had been done in the heart of darkness was repeated in the heart of Europe, no one recognized it. No one wished to admit what everyone knew.

Everywhere in the world, this knowledge is being suppressed. Knowledge that, if it were made known, would shatter our image of the world and force us to question ourselves. Everywhere there, Heart of Darkness is being enacted…Black Elk, holy man of the Oglala Lakota people, said after the Wounded Knee Massacre, ‘I didn’t know then how much was ended… A people’s dream died there. It was a beautiful dream. The nation’s circle is broken and scattered. There is no centre any longer, and the sacred tree is dead.’”

There are uncomfortable parallels between Peck’s insights into Holocaust denial, the denial of the crimes of colonialism, and the everyday denial of the damage that affluence and material consumption are causing to the entire planet. From the horrors of resource mining to the devastation of the oceans by plastics, such evidence represents a constant ‘background noise’ in the modern media. A noise people have learned to ignore, in order to keep functioning amidst the cognitive dissonance of their everyday, disconnected lives.

As Peck says, “It is not knowledge that is lacking”. People are aware. The fact that they will not engage with the issue, as outlined in ‘Bright Green Lies’, is that people innately know the extent of their own complicity. To do so, ‘would shatter our image of the world and force us to question ourselves’.

We do not need more ‘evidence’. The block to ecological change is not simply a lack of ‘knowledge’. It is that many all too well understand the reality of what stopping the ecological crisis would entail. Trapped by their subconscious fear of what that would mean personally, they cannot see a solution to the psychological dependency engendered by consumerism and industrial society.

Mainstream environmentalism, as the film outlines, is its own worst enemy. In advocating ephemeral, consumer-based solutions to tackling ecological breakdown, it creates its own certain failure. Unfortunately, unless the counter-point to that, the ‘deep green’ argument, is able to give people the confidence to accept and let go of industrial society, it will not make progress either. I think this film almost gets there; but we need to focus far more on the workable, existing examples of people living outside of that system to give people the confidence to make that internal, ‘leap of faith’. For those who want to follow this road, and perhaps provide those examples, this film is a good starting point to build from.

Released under the Creative Commons ‘BY-NC-SA’ 4.0 International License

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed above are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Deep Green Resistance, the News Service, or its staff.