by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 21, 2016 | Indigenous Autonomy, Lobbying

NEW REPORT DOCUMENTS CHALLENGES OF DEFENDING INDIGENOUS LAND RIGHTS IN THE PARAGUAYAN CHACO

By Fionuala Cregan / Intercontinental Cry

Featured image: Members of the the Ayoreo community of Cuyabia. Photo: Iniciativa Amotocodie

“We don’t care if our struggle involves going to prison or even dying. Our struggle is about justice because the land is ours and our children’s.”

—Alejandro Servín

When Alejandro Servin and five others members of the Enxet Sur indigenous community Kelyenmagategma returned home after two days in the woods hunting and collecting honey, little did they expect to be showered with bullets.

“Three of us were walking ahead when we heard the shots, a bullet just missed me. We ran back into the forest to seek refuge but the employees of the estate managed to catch the youngest member of our group, Francisco, who was 14 years old at the time,” says Servín. “As a result all of us came out. Three hours later a contingent of police arrived, arrested us without a warrant and brought us – in the estate owner’s truck – to the nearest police station.”

Following their arrest, the six indigenous men were transferred to the capital Asuncion where they were held incommunicado for 48 hours without access to a lawyer or contact with their families. They were eventually charged with “theft of cattle” – a crime punishable by up to 10 years in prison under the Paraguayan Constitution. TierraViva – a human rights NGO that provides legal support and advocates for the land rights of indigenous communities in the Chaco region of Paraguay – eventually managed to get the charges dropped due to lack of evidence and the serious legal inconsistencies surrounding the arrest.

It is these as well as an array of other cases documented during more than 20 years of work in the Paraguayan Chaco that lead TierraViva to publish the first ever report on the situation of Human Rights Defenders. The report, released in December of last year, features case studies of illegitimate criminal charges, threats and acts of violence against 19 indigenous leaders and human rights lawyers working on land rights in the Chaco.

Paraguay is divided into strikingly different eastern and western regions by the Rio Paraguay. The southeastern Paranena region can be generally described as consisting of an area of highlands that slopes toward the Rio Paraguay. The Chaco in the nothwestern region is predominantly lowlands, also inclined toward the Rio Paraguay, that are alternately flooded and parched. Image by freeworldmaps.net.

This arid forested region represents just over 60 percent of Paraguayan territory. It is inhabited by indigenous communities who know it as their ancestral land and private landowners who began to purchase estates from the 1940s onwards, denying the existence of those indigenous communities. This was the case for Kelyenmagategma: the company El Algarrobal SA bought land in 2002 that was inhabited by this Enxet Sur community.

In the past decade, land in the more populated eastern part of the country has become scarce leading to an expansion of the agricultural frontier into the Chaco. The rate of deforestation over the past five years has averaged 500 hectares (equivalent to 500 football fields) per day. In response to this alarming trend, indigenous communities have begun to organize and unite to secure legal title to parts of their ancestral lands to protect what remains of the unique Chaco ecosystem.

Despite the fact that the constitution of Paraguay recognizes the rights of Indigenous Peoples to their ancestral lands, according to Rodrigo Villagra Carron of TierraViva:

“What we see is an undeniable pattern of Government support for the interests of private landowners and the repression of those who defend human rights and national and international legislation related to the rights of Indigenous People.”

This was echoed by Cristina Coronel at the launch of the report in Asuncion in December:

“What this report reveals is [a] world where things are upside down… where indigenous communities and lawyers are defending universal human rights, but instead of protecting them, the police, public prosecutors and other representatives of the government protect the cattle ranchers and agro-industrial companies responsible for illegal deforestation and evictions of Indigenous People from their ancestral lands.”

This can clearly be seen in the case of Unine Cutamurajna from the Ayoreo community of Cuyabia who denounced illegal deforestation by Brandenstein Agro-Forest Investment (BAFI). Cuyabia acquired legal title to 25,000 hectares of land in 1996; but since then it is estimated the community has lost at least 6000 hectares due to land grabs by cattle ranchers. On one occasion, in 2015, the community hijacked a bulldozer that had been clearing vast tracts of forest on land belonging to them. Instead of investigating the illegal actions of BAFI, the Government of Paraguay sent a contingent of police to recover the bulldozer.he community has subsequently suffered threats from heavily armed private security guards working for the company.

“The Government sides with the cattle ranchers because they have money. We Indigenous People don’t have money,” says Unine. “But we will keep defending our land, it doesn’t matter if they continue to threaten us. We will not give up one more single piece of our ancestral land.”

Other cases in the report include:

- Government employee Irma Torales who, while working at the Public Registrar’s Office, refused to become involved in a case of embezzlement of funds destined for the purchase of land for indigenous communities. Her actions lead to the arrest and imprisonment of the former Director of the National Indigenous Institute of Paraguay. Despite this, Irma was subsequently demoted to a more junior role with a significant reduction in her salary.

- Human Rights Lawyer and Director of TierraViva Julia Cabello who faced a possible one-year suspension from practicing law or disqualification from the Paraguay Bar Association for a criticism she made of a Supreme Court Decision to review the constitutionality of a law allowing the return of more than 14,404 hectares of traditional land to the Sawhoyamaxa indigenous community.

TierraViva intends to use the report to carry out continued advocacy and raise awareness of the grave situation of human rights defenders in the Chaco.

According to Villagra Carron:

“This report is a condemnation of the structural inequality in Paraguay and a call to action. The cases documented in it are by no means exhaustive but just a few examples of what is happening in a broader context of rights deprivation. We urgently need to bring this situation and the government’s complicity and/or role in perpetuating it to public attention or the situation risks becoming even more dangerous, serious and unjust.”

The report received support from the Gran Chaco Ecumenical Small Projects Fund which works to strengthen the capacity of civil society organizations, groups and communities in the South American Chaco to transform the conditions of poverty and inequality and promote human rights.

To see the full report in Spanish click here.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 18, 2016 | Indigenous Autonomy, Lobbying

By Glenn Scherer, Mongabay

Featured image: Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff visits the construction site of the Belo Monte Dam, 2014. Photo by Ichiro Guerra/Sala de Imprensa licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic license

The gigantic Belo Monte hydroelectric dam, located on the Xingu River in the heart of the Brazilian Amazon, stood just weeks away from beginning operation this week — but the controversial mega-dam, the third largest on earth, has now been blocked from generating electricity by the Brazilian court system until its builders and the government meet previous commitments made to the region’s indigenous people.

Federal court judge Maria Carolina Valente do Carmo in the city of Altamira, in the state of Pará where the dam is located, has suspended the dam’s operating license. It will not be reinstated, she decided, until the dam’s owner Norte Energia SA, along with Brazil’s government, meet a 2014 court-ordered licensing requirement to reorganize the regional office of Funai, the national agency that protects Brazil’s indigenous groups.

Judge Valente do Carmo has fined the government and company R$900,000 (US$225,000) for non-compliance with the Funai requirement, a provision included in the rules governing Belo Monte when the project was given its preliminary license in 2010.

This is the latest in a series of snafus that have plagued the dam’s construction. Licensing of the project was delayed last September by Brazil’s environmental agency IBAMA, due to a failure to complete agreed to provisions to mitigate the impacts of inundating thousands of acres of Amazon rain forest — flooding that could displace 20,000 people.

Indigenous village near the Xingu River in the Amazon. Indigenous lands could soon be flooded by the Belo Monte dam. Photo by Pedro Biondi/ABr licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Brazil license.

Earlier in 2015, federal prosecutors found that Norte Energia violated 55 different obligations it had agreed to in order to guarantee the survival of indigenous groups, farmers and fishermen whose homes and lands will be lost.In December, Brazil’s Public Federal Ministry, an independent state body started legal proceedings to have it recognized that the crime of “ethnocide” was committed against seven indigenous groups during the building of the Belo Monte dam.

Indigenous groups have fought the dam since its inception, saying that it will severely impair their water supply and impact fishing and hunting. They especially contend that it will reduce the river’s flow by 80 percent at the Volta Grande (“Big Bend”), where indigenous Juruna and Arara people and sixteen other ethnic groups live, according to the teleSUR television network.

Partially republished with permission of Mongabay. Read the full article at Brazilian court suspends operating license for Belo Monte dam

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Dec 27, 2015 | Colonialism & Conquest, Indigenous Autonomy

By Mary Cappelli

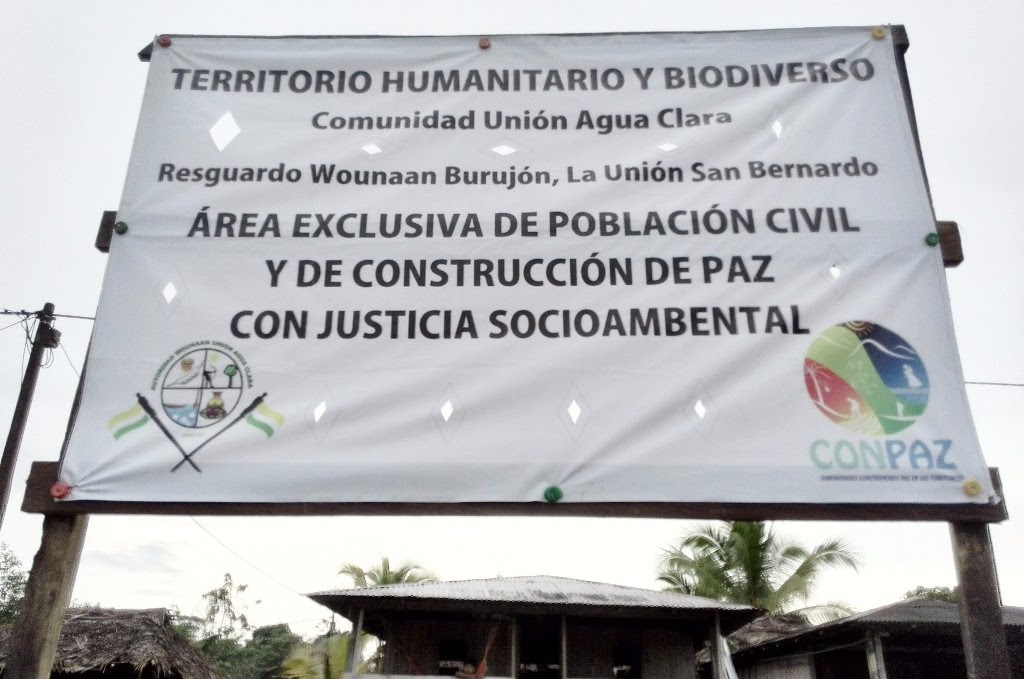

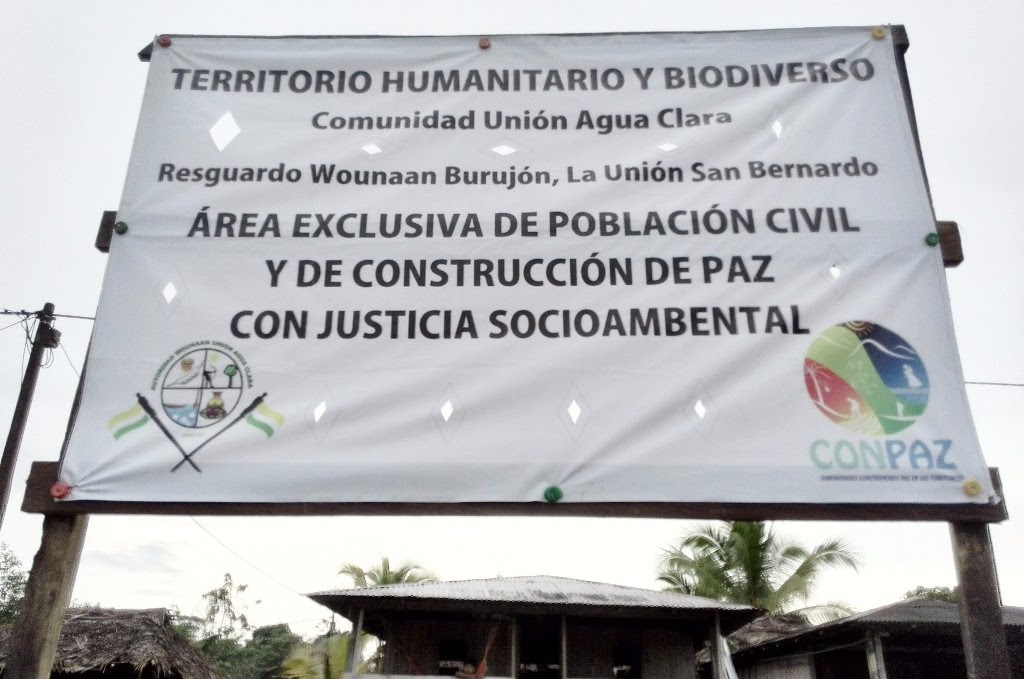

Featured image: Wounaan Banner, reading:

Humanitarian and biodiverse territory

Community of Union Aguas Claras

Reservation of Wounaan Burujon, La Union San Bernardo

An exclusive area of civilians and peacebuilding and justice

The Wounaan Tribe of Northwestern Colombia’s San Juan River is the latest casualty of a violent 25 year reign of terror hastened by the convergence of coca growers, gold miners, paramilitaries, guerillas, and government troops—all vying for control of the waterways and resources along the ancestral stretch of traditional Wounaan territories. Until the arrival of mono-crop production for export, Wounaan’s steadfast strategies have thwarted the bloodied battlefields of Spanish colonial impositions, nationalist armies, and Marxist guerrillas.

Occupying small thatched huts stilted on posts hovering up to eight feet high along the clearings on the riverbanks, the Wounaan kept to their subsistence livelihoods of hunting, fishing, Werregue Palm basket-weaving, and small-scale agriculture of bananas, pineapples, and yucca. That is until November 2014 when the Wounaan Tribe was forced to leave their village of Unión Aguas Claras along the San Juan river of the Cauca Valley and take up a 12-month residence in El Cristal Sports Arena in Buenaventura, Colombia.

According to Wounaan spokesman Crelo Obispo, “Paramilitaries kicked us out of land” and for twelve months they worked diligently to “find a peaceful way to recover our own indigenous land.” The Wounaan turned their occupation into a form of civil disobedience and refused to return to their lands without adequate protection and security from warring factions. Although on November 29, 2015, they returned home along the San Juan River, their cultural survival signals a critical humanitarian and environmental emergency in which indigenous people living sustainable lives have been caught in a resource war for coca cultivation, gold mining and control of key river tributaries.

Occupy El Cristal

For a full year, 343 Wounaan people, 63 families, occupied the cold hard floor of the basketball courts sleeping in multi-colored hand-woven hammocks strung beneath the stadium bleachers. One of them was a young wearied mother holding a shirtless 11 month-old infant suffering from a burning fever and bouts of diarrhea and vomiting. She recalled: “There wasn’t any medicine.” Herein lies the crisis. Not only were mothers unable to gain access to traditional herbal medicines, they were also unable to gain access to modern health care. Three somber mothers told me they were running out of adequate food and water sources. Buenaventura Officials confirmed the death of two young children, one year-old Neiber Cárdenas Pirza in December 2014 and a two day-old baby in June 2014. The Wounaan claimed the deaths were a result of inadequate health care and living conditions in the sports arena. “Our people practice culture, artistry, spirituality and traditional medicine. We need our lands to do so,” said Obispo.

The affirmative belief that the Wounaan were “occupying” the sports arena and taking a political stand against their dispossession by violence is key to understanding Wounaan resistance. “We arrived November 28, 2014 and since that time we had been in resistance,” Chama Puto said. Because the “the local government hardly did anything, and gave no guarantees of assistance,” he urgently called on international help and social advocacy networks to “get meetings with entities who could make change” and affirmed Wounaan ancestral ties to their lands. “Land doesn’t belong to the government or police. It belongs to the indigenous,” he added.

The occupation of El Cristal is an example of how Indigenous peoples enact visibly distinctive resistance tactics to draw political and social mobilization to defend their right to living in their native territories. Although Wounaan Leaders such as Chama Puto are well versed in Colombia’s constitutional law, they are fully aware of how constitutional decrees have remained rhetorical discourses because of the government’s failure to implement constitutional protections within its infrastructure—an absence of institutional support that has undermined the visionary purpose of the protections. In particular, Article 63 states: “Communal lands of ethnic groups and reservation lands cannot be taken away or attached”; Article 72 states: “Ethnic groups settled in areas of archeological treasures have special rights over that cultural heritage, which rights must be regulated by law”; Article 246 provides that “the authorities of the indigenous peoples may exercise jurisdictional functions within their territories, in accordance with their own standards and procedures, provided they do not conflict with the Constitution and laws of the Republic.”

While in some cases, legal maneuvering and mobilization within Colombian Courts have served to defend indigenous landholdings, the year-long Wounaan occupation of El Cristal is a blatant recognition of the ineffectiveness of Colombia’s legislation and juridical processes. Innovative forms of resistance appeal to wider socio-political networks capable of eliciting support across local, regional, national and global borders; however, it comes with a price.

Rhizomic World

El Cristal Sports Arena was a far cry from the Wounaan’s rhizomic world of heterogeneity and its interconnected relations of all plant, animal, ancestral and human life living within its ecosystems. This dynamic cartography of interconnected networks mapped across their ancestral rhizomic river systems and landscape moves beyond western metaphysical notions of duality to foster a cosmos of inter-being. Wounaan livelihood and well-being rely on their interaction with their landscape, an animistic ethno-geographic interaction grounded in rhizomic thought in which “any point of a rhizome can be connected to anything other, and must be” (Delueze and Guattari 1988).

These beliefs further their kinship networks across time and space in a continuous state of growth in which identities and relationships extend and merge through a web of intersecting relationships. Bill Ashcroft explains the rhizome in biological imagery as multiplying “root system which spreads across the ground” from varying points reaching out across the nomadic space “rather than a single tap root” (1999).

For the Wounaan, the San Juan River is an essential organizing principle of their rhizomic networking system, rich in its biodiversity in which their cosmology interconnects them to 8000-9000 vascular plants, 577 bird species, 52 snake species, 45 lizard and allied species and 127 amphibian species—all inter-being in an ecosystem without hierarchies. In addition to its cohesive social networks, the San Juan River is the true river (döchaar) and ancestral homeland and thus a material feature in the development of their worldview and their perceptions of themselves (Velásquez Runk 2005).

The fluvial systems crisscross over a three-dimensional topography, which includes portals underworld, the real world and the celestial world. In this way their river-dominated cosmos reflects the comings and goings on the river up (marag), down (badag), to (jerag), and from (durrag) in a world where spirits, beings, plants and animals in the visible and invisible world live in a balance of reciprocal equilibrium (Velásquez Runk 2005).

Because of their metaphysical approach which links native individualities, political strategies, and traditional subsistence practices they have been able to maintain their traditional livelihoods and ways of being against the onslaught of land dispossession and acculturation (Velasco 2011). Although their rhizomic community is resistant to rupture where it has fissured and peoples are deterritorialized, the river’s organic networking systems have been capable of reattaching the Wounaan to people, plants, animals within its extended network or creating new connections across its geographical space (Kamash 2008).

Since the 1990s, the San Juan River’s fluvial systems have become reconfigured spaces in which flows of capital, commodities and contraband have brought in a host of nonlocal actors vying for spatial control of its strategic geographies. These vital commercial river networks, which connect the Colombian interior with the Pacific Coast are needed for the production and transportation of gold mining excavation and cocoa cultivation turning the once-peaceful rhizomic ecosystem into a bloody battleground between narco traffickers, gold minders, the FARC, the ELN, the Urabeños, the Rastrojos, and other left wing, right wing, and neo-paramilitary forces.

The result is not only the displacement of indigenous peoples and the disruption of the natural equilibrium of the Wounaan subsistent lifestyle, but the destruction of the biodiverse habitat in which its diverse resources have been transformed to commercial assets and mobilized for monocrop and gold production of surplus value. Added to the actors competing for resources is the introduction of new players from the National Development Plan hoping to position the San Juan River as a key geographic territory for the neoliberal exploitation of resources for free trade agreements. Dispossession for capitalist production has more importantly led to the desecration of ancestral homelands in which families are increasingly intimidated, disappeared and butchered by a collusion of local and nonlocal actors to expedite commodity commerce.

“The government said we are something in the way of development,” said Crelo Obispo further noting, “We’ve been attacked by our conqueror.” Another Wounaan spokesman added, “They want to exterminate us.” Whether it is death by paramilitary, death by narco trafficker, or death in the crossfire between guerillas and the army, there is one certainty as Crelo Obispo declares: There return to their homeland is precarious and must be “met with protection and dignity.”

Amidst these conditions are ongoing negotiations for a bilateral ceasefire between the Government and FARC. Although the Colombian government and FARC rebels have moved towards a comprehensive plan to end an ongoing civil war which, since 1964 has killed 220,000 people, the Wounaan have still been left out in the cold (Rodzinsky). Chama Puto points out that while they are negotiating in Havana, Cuba, “we had been ignored in all negotiation processes.” He believes that conflict resolution can result only when “the government negotiates with all its people.”

As of today, this has not happened and the people the color of the soil who turned their displacement into a political strategy of indigenous resistance to the destruction of their traditional ecosystems still struggle for survival. Chama Puto wants a governmental guarantee of protection and safety in order to survive on their ancestral lands. “We are done negotiating,” he said.

Forceful dispossession underpins the plight of the Wounaan whose homeland has been drained by capital’s international reach for resources in which a “free market exchange relies on and takes advantage of the political and cultural dispossession of certain subjects” (Hennessey 2013). How do indigenous people who make up two percent of Colombia’s population coexist in a global world that renders them disposable, inhuman beings? In this scenario, the two percent making up the indigenous groups of Colombia become eight percent of the dispossessed, displaced, and destined to misery as a form of “human waste”; sadly, a myth narrated and played out in the many parts of the globe.

In El Cristal, the Wounaan were separated from their means of subsistence and vigorously resisted all paradigms of commercial expansion and regional control of their economies—a pattern in which, “more than 5.7 million people have been internally displaced in Colombia since the start of recording official cumulative registration figure” (UNHRC 2015). As of 2014, Colombia’s National Victims’ Unit documented 97,453 cases of forced displacement, mostly along the Pacific region. The El Cristal crisis exposed the systematic layers of political collusion that render Wounaan territories disposable sites of exploitation and economic casualties, which dispossess its peoples from their traditional livelihoods for the benefit of both regional, national, and global markets.

Wounaan Resistance Strategies

Wounaan resistance strategies date back to colonization and manifested in their traditional tactics they implemented to maintain their sense of cultural dignity during their resistance campaign. While living in the Sports Arena women practiced small-scale artesanías in the form of colorful bracelets, necklaces, earrings, and small-carved wooden bowls. The unbroken practice of these customs created communal solidarity and furthered their economic livelihoods, traditional knowledge, and cultural sustainability (Velasco 2012). Although these courageous women were proud to sell their artisans to sports arena visitors, the transactions were soured by the reality of their dispossession. “Collectively and physically the living conditions” were “inadequate, the food inadequate.”

Wounaan resilience to reattach itself to its rhizomic rivers network is precarious and subject to intra-institutional support of regional and national control. It is yet to be seen if this latest mobilization strategy will provide any safeguards and protections for their community. “Promises have been unfulfilled and we have become strangers to ourselves,” sighed a wearied Obispo.

For more information, see CONPAZ.

References

Ashcroft, Bill (1999). “The Rhizome of Post-colonial Discourse” in Roger Luckhurst and Peter Marks (eds.) Literature and the Contemporary: Fictions and Theories of the Present, London: Longman pp. 111-125.

Deleuze, Giles, and Felix Guattarri (2007). A Thousand Plateus: Capitalism and Schizophreina. Brian Massumi, trans. Minneapolis; University of Minnesota Press.

Colombia, Información sobre Derechos Humanos y Libertades Fundamentales de la Poblaciones Indígenas presentada por el Gobierno. (Published in UN.E/CN.4/ Sub.2/AC.4/1991/4).

Hennessy, Rosemary. Fires on the Border. Hennessy, Rosemary. Fires on the Border: The Passionate Politics of Labor Organizing on the Mexican Frontera. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013. Print.

Kamash, Zena (2008). What Lies Beneath? Perceptions of the Ontological Paradox of Water, World Archeology 40 (2) 224-237).

Velasco, Marcela (2011). “Contested Territoriality: Ethnic Challenges to Colombia’s Territorial Regimes.” Bulletin of Latin American Research 30 (2): 213–228.

Brodzinsky, Sibylla. “ Colombia’s government and Farc rebels reach agreement in step to end civil war.” The Guardian. 15 Dec. 2015.

Runk, Julie Valasquez. (2005). And the Creator Began to Carve Us of Cocobolo: Culture, History, Forest Ecology, and Conservation among Wounaan in Eastern Panama. PhD dissertation, Department of Anthropology and the School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, Yale University and the New York Botanical Garden.

__________. (2009). Social and River Networks for the Trees: Wounaan’s Riverine Rhizomic Cosmos and Arboreal Conservation. American Anthopologist 111(4).

2015 UNRCR Country Operations Profile-Colombia. The UN Refugee Agency.

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Dec 5, 2015 | Indigenous Autonomy

By Fionuala Cregan / Intercontinental Cry

Image by Toni Fish/flckr. Some Rights Reserved.

For most Peruvians it was a Sunday like any other; but in the Wampis community of Soledad, it was a historic day. On November 29, the Wampis nation declared the formation of the first Autonomous Indigenous Government in Peru.

Spanning a 1.3 million hectare territory – a region the size of the State of Connecticut – the newly elected government brings together 100 Wampis communities representing some 10,613 people who continue to live a traditional subsistence way of life through hunting, fishing and small scale agriculture.

While the newly-formed government does not seek independence from Peru, its main role is to protect Wampis ancestral territory and promote a sustainable way of life that prioritizes well-being, food security and a healthy harmonious existence with the natural world.

This is no small task in today’s world; but it is nonetheless a necessary one, as Andres Noningo Sesen, Waimaku (Wampis Visionary), explains in a recent email to the New Internationalist. Due to the advance of mining and oil companies, illegal logging and palm oil plantations, the Wampis have found their livelihoods increasingly under threat.

We will still be Peruvian citizens but now we will have our own government responsible for our own territory. This will allow us to defend our forests from the threats of logging, mining, oil and gas and mega dams. As every year goes by these threats grow bigger.

This unity will bring us the political strength we need to explain our vision to the world and to the governments and companies who only see the gold and oil in our rivers and forests. For them, too often we are like a small insect who they want to squash. Any activity planned in our territory that will affect us will now have to be decided by our own government which represents all our communities.

The new Government consists of a President, Vice-President and an 80-member parliament with members elected by each Wampis community through their own local assemblies. Eventually, it will have 102 members. The basis for governance is the Statute of the Autonomous Territorial Government of the Wampis Nation, the result of a long process that took place over several years with the Wampis nation holding over 50 community meetings and 15 general assemblies to develop and debate the Statute which lays out their vision for the future in all areas of life including religion, spirituality, education, language and recovery of ancestral place names.

The Statute places special emphasis on the rights of women stating,

The Wampis nation will work to achieve true gender equality. The Government will work at all levels to promote a campaign to end all forms of violence against Wampis women… respect for women and unity takes precedence over cultural practices, specifically polygamy which took places in other historical contexts and which today can lead to social conflicts… The Wampis Government will prioritize access to third level education for women in different universities throughout the country.

The Statute also emphasizes the obligations of the Peruvian state to respect the rights and autonomy of indigenous peoples and nations. Amongst other principles, the Statute requires that any activity that could affect Wampis territory must secure the Free, Prior and Informed Consent of the Wampis nation. Specifically, this means that the Government of Peru cannot give out any further concessions that allow oil or mining companies to enter Wampis territory without a prior consultation process.

Currently, the Wampis are in the process of resisting such a concession that was granted, amongst others, to Afrodita S.A. for gold mining activities in a bi-national protected area along the border area with Ecuador. Since 2001, Afrodita has maintained a presence in this part of the Peruvian Amazon and in 2010 had its license suspended in the region of Cordillera del Cóndor due to the sustained resistance of indigenous communities living along the Cenpea and Maraño rivers. Both rivers suffered from severe mercury and cyanide stemming from mining activities in the region.

This, according to the newly elected Pamuk (first President) Wrays Pérez Ramirez, will be the largest challenge for the Autonomous Territorial Government of the Wampis Nation. The new president told Intercontinental Cry by phone:

We know that it will be difficult to get the National Government to support us and recognize our territory. It will seem unacceptable to the Government to have to consult us regarding any activity that could affect our territory. We know that it is going to be hard work but we are prepared. We are not going to stay silent not least when we have legal backing from national and international legislation regarding our right to self-determination and free, prior and informed consent. It will be difficult, but not impossible.

“The election has not taken place behind the Government’s back,” he adds. “The Governors of Amazonas and Loreto Province were invited to the summit as well as the Minister for Environment, Energy and Mining and the Minister for Culture but none attended. At the local level we have support and will work closely with, amongst others, the mayors of Rio Santiago and Morona who agree with our decision.”

The historic decision of the Wampis nation will be a source of inspiration for indigenous nations throughout Latin America. As a model for sustainable development and the preservation of some of our last remaining forests, it should also inspire world leaders as they meet at the COP21 Climate Summit in Paris this week.

“While the Peruvian government and other governments are in Paris talking about how to protect tropical forests and reduce contamination, we are taking concrete actions in our territory to contribute to this global goal,” says the newly elected Pamuk.