by DGR Colorado Plateau | Nov 4, 2015 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Mining & Drilling

By Apoorva Joshi / Mongabay

This is the first in a two-part series on gold mining in Suriname. Read the second part.

- High gold prices are leading to an increase in mining activity.

- Mining activities threaten Suriname’s primary forests, some of the most-intact in South America.

- Mercury released from the mining process can be toxic, and is showing up in human population centers far downstream.

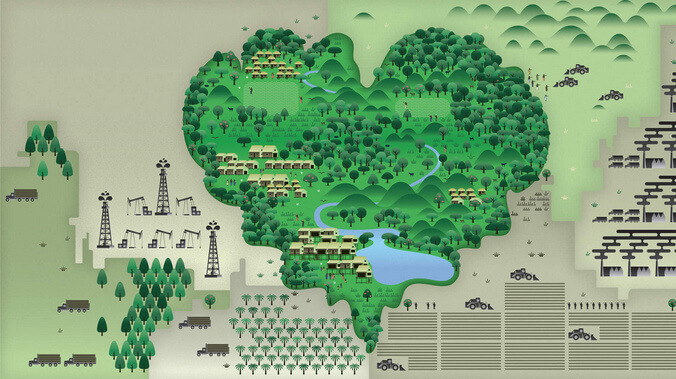

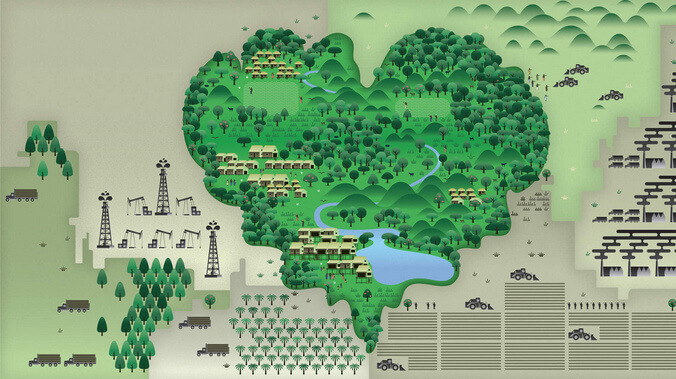

Record high gold prices over much of the past decade have triggered a massive gold rush across much of the Amazon basin, resulting in the destruction of thousands of hectares of pristine rainforest and the contamination of major rivers with toxic heavy metals. A newly released report published by the Amazon Conservation Team titled “Amazon Gold Rush: Gold Mining in Suriname” explores the rapid expansion and impacts of gold mining in Suriname through cartography and digital storytelling.

It finds that from 2000 to 2014, the extent of gold mining in the South American country increased by 893 percent.

While the Amazon rainforests of Brazil and Peru are well-known, Suriname’s vast and ancient rainforests remain one of the world’s best-kept natural secrets, according to the online report. But demand for the age-old elemental metal threatens to destroy them.

“According to our calculations, deforestation caused by gold mining has been growing steadily since the turn of the century and rapidly in the past five years,” GIS and Web Development Coordinator at the Amazon Conservation Team, Rudo Kemper told mongabay.com. The average rate of deforestation since 2000 is close to 3,000 hectares per year, but in 2014 an estimated 5,712 hectares of forest cover was lost to gold mining, he said. The REDD+ for the Guiana Shield regional collaborative study on gold mining shows similar trends, reporting a near-doubling (97 percent increase) of deforestation from 2008 to 2014 and attributing a total of 53,668 hectares of deforestation to gold mining in 2014.

Compared to many other South American countries, Suriname still holds much of its forest cover. According to Global Forest Watch, Suriname lost 0.7 percent of its tree cover from 2001 through 2014 – a small proportion compared to Brazil’s 6.9 percent. However, Suriname’s intact forest landscapes – large, continuous areas of primary forest – do show degradation since 2000.

The Guiana Shield, as Kemper puts it, is one of three cratons of the South American tectonic plate. “It is a tropical rainforest region covered with unique table-top mountains called tepuis,” he said. “It has the largest expanse of undisturbed tropical rainforest in the world, and one of the highest rates of biodiversity.” Suriname is among the most forested countries in the world, as the report highlights. In 2012, 95 percent of the country’s entire area was classified as forest. Globally surpassed only by its neighbor French Guiana, Suriname’s pristine rainforest harbors numerous unique species of fauna like the Guianan cock-of-the-rock (Rupicola rupicola), the famous blue poison dart frog (Dendrobates tinctorius), the red-faced spider monkey (Ateles paniscus), and the pale-throated sloth (Bradypus tridactylus). Jaguars, tapirs, and giant anteaters also call the region home. The mineral-rich Greenstone Belt region, where most of the gold mining in Suriname takes place, is primarily composed of the forested highlands of the Guiana Shield. Conservationists worry that deforestation caused by rapidly expanding gold mining activities is negatively impacting the habitat of many unique species.

Suriname rainforest. Photo courtesy of the Amazon Conservation Team.

Since the 1960s, development and resource extraction incursions into the country’s interior have become commonplace. These encroachments have taken the form of dam-building, logging, bauxite mining, and as of the turn of the century, small-scale and industrial gold mining, the report says. Given that it is one of the world’s smallest countries, Suriname’s annual rate of gold production might not compare to that of larger countries like South Africa, China, Russia or Peru. But relative to its land area, Suriname actually ranks tenth in global gold production.

Partially republished with permission of Mongabay. Read the full article, Gold mining explodes in Suriname, puts forests and people at risk.

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Oct 21, 2015 | Indigenous Autonomy, Lobbying, Mining & Drilling

CASE ON INDIGENOUS LAND RIGHTS AND EXTRACTIVE PROJECTS MOVES FORWARD AT INTER-AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS

Washington, DC – The U’wa Nation has received an admissibility report by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights allowing its case against Colombia to move forward, recognizing that the indigenous group can seek the Commission’s help in defending its traditional territory. Although the U’wa have successfully defeated multiple oil and gas projects in the nearly two decades since they first filed their complaint with the Commission, the report recognizes that winning these battles does not end the overall complaint with the Colombian government, which does not fully recognize the U’wa people’s rights to their territory.

In a statement released [on Oct. 16], The U’wa organization Asou’wa said: “Our U’wa Nation has been heard by the natural law, our ancestors and gods that guide and govern our thinking to safeguard, protect and care for our mother earth; While there are U’wa people, we will continue resisting in defense of our ancient rights.” EarthRights International (ERI) has been supporting Aura Tegria Cristancho, an U’wa lawyer who has been working on the case since 2013 from its offices in Lima, Peru, and Washington, DC.

Asou’wa, supported by the National Indigenous Organization of Colombia and the Coalition for Amazonian Peoples and Their Environment, first filed their complaint with the Commission in 1997. At the time, US-based Occidental Petroleum (Oxy) was threatening to drill for oil in their lands. The U’wa, supported by a global campaign against Oxy led by groups such as Amazon Watch and the Rainforest Action Network, secured Oxy’s withdrawal in 2001. More recently, Colombia’s Ecopetrol tried to move forward with a gas project on U’wa land, but pulled out earlier this year. However, U’wa’s title over their ancestral lands have not been yet recognized.

The Commission’s decision comes after the U’wa and their supporters made it clear that, despite these victories, the root of the problem is the government’s lack of recognition and protection of the indigenous group’s ancestral territory.

“With this decision, the Commission recognized that even though Oxy and Ecopetrol pulled out, the U’wa remain threatened by the failure to fully protect their homeland,” said Camila Mariño, a Colombian lawyer and legal fellow with EarthRights International. “We are proud to stand with the U’wa.”

In the decision, dated July 22 but only released [now], the Commission formally accepts the U’wa petition as “admissible.” According to the Commission’s website, only twelve cases have been accepted as admissible so far this year. Following this decision, the case will move to the “merits” stage, in which the Commission will rule on the rights violations at issue.

– 30 –

Contact:

Valentina Stackl

+1 (202) 466 5188 x 100

valentina@earthrights.org

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Oct 9, 2015 | Indigenous Autonomy, Lobbying, Mining & Drilling

By Hannibal Rhoades / Intercontinental Cry

After five years of legal contests and uncertainty, the Colombian Constitutional Court has confirmed that Yaigojé Apaporis, an indigenous resguardo (a legally recognized, collectively owned territory), also has legitimate status as a national park.

The decision is cause for celebration for Indigenous Peoples who call the region home. But it is less welcome news for Canadian multinational mining corporation Cosigo Resources, the company contesting the area’s national park status. The court’s ruling immediately and indefinitely suspends all mining activities in the park, including Cosigo’s license to mine gold from one of Yaigojé’s most sacred areas.

In the broader context of Colombia’s push to expand mining activities in the name of development, the court’s decision is seen as a significant precedent.

Since the 1980s, Colombia has protected more than 24 million hectares of the Amazon, placing an area the size of Britain back in the hands of its traditional owners. By choosing the rights of Indigenous Peoples and a new national park over multinational mining interests, the court’s decision safeguards Colombia’s achievements rather than undermining them.

THE BATTLE FOR YUISI’S GOLDEN LENS

Straddling Amazonas and Vaupés states, comprising a million hectares of the Northwestern Colombian Amazon, the pristine forest region of Yaigojé Apaporis is rich in both biological and cultural diversity.

The area hosts endangered mammals such as the giant anteater, jaguar, manatee and pink river dolphin. It is also home to the Makuna, Tanimuka, Letuama, Barasano, Cabiyari, Yahuna and Yujup-Maku Indigenous Peoples, who share a common cosmological system and rich shamanistic traditions. Together these populations act as Yaigojé’s guardians, a role that was strengthened in 1988 when, with the assistance of Colombian NGO Gaia Amazonas, they successfully established the Yaigojé Apaporis resguardo over their traditional territory. But this status has recently been tested.

Under Colombian law, a resguardo recognition grants its inhabitants collective ownership of and rights to the soil, but the subsoil remains in the control of the state and vulnerable to prospecting. With companies seeking to exploit this loophole, the Colombian Amazon has seen a tidal wave of mining interest since the mid-2000s, with the government declaring mining an “engine for development.”

Riding at the crest of this wave, in the late 2000s Canadian mining multinational Cosigo Resources made clear to local communities in Yaigojé its intention to mine for gold at a site within the resguardo known as La Libertad or Yuisi.

Local indigenous leaders say Cosigo became known to them when company representatives visited their malocas (traditional riverside houses). The indigenous leaders allege that officials offered them money in return for assurance of support the company to mine in Yuisi. These offers were rejected.

At Yuisi, a wide stretch of the Apaporis river cascades over rocks, forming roaring rapids. To the people of Yaigojé it is a vital sacred site, inextricably tied to their story of origin, identity and ability to care for the territory and the planet as a whole. Elders say “Yuisi is the crib of our way of thinking, of life and power. Everything is born here in thought: nature, the crops, trees, fruits, everything that exists, exists before in thought.”

Local shaman describe the gold and other minerals that form the bedrock of their territory as ‘lenses’ that allow them to see into the Earth, divine or diagnose any problems and correct them through rituals, prayer and thought. If gold were to be removed from Yuisi, they would lose their ability to cure and manage their territory as they have done for millennia. This is because an integral part of the territory itself would be lost. The notion that territory stops at the soil “as deep as the manioc’s root” is alien.

With negotiation with Cosigo out of the question, the traditional authorities in Yaigojé called an urgent congress of the Asociación de Capitanes Indígenas del Yaigojé Apaporis (ACIYA), an indigenous organization formed of groups living along the Apaporis River, in the area of Yaigojé that lies in Amazonas State. Having discussed the dangers posed by Cosigo’s presence and plans, ACIYA agreed that they must seek help from outside sources to further protect their territory.

“The best way to shield the territory was to call upon the state. In other words: Western disease is cured by Western medicine. If all mining licenses are given by the state, it is necessary to call on the state to defend the territory,” says Gerardo Macuna, a representative of ACIYA.

Advised that achieving national park status would extend protection to the subsoil, ACIYA and its supporters formally requested that the Colombian Government create a national park over their resguardo and traditional territory.

The people’s effort to add a third layer of protection for their territory was successful. In October 2009, Yaigojé Apaporis became Colombia’s 55th national protected area, but celebrations were short lived. Just two days after the area was awarded national park status, Cosigo Resources was granted a mining title for the Yuisi area, catalysing an epic struggle between Colombia’s will to protect the Amazon, with the help of indigenous inhabitants, or exploit it at their expense by prioritizing mining.

DEEP IN THE AMAZON, A SMOKING GUN

Despite having been granted a license, Yaigojé’s new status as a national park remained an obstacle to Cosigo. The national park status, and its accompanying legal protections for the subsoil, would need to be revoked before mining could begin.

Facing stiff opposition from both ACIYA and the Colombian National Parks authorities just as Cosigo appeared to be fighting an uphill battle, the company got what seemed an almost impossible stroke of luck. A few months after Yaigojé was declared a national park, members of indigenous organization ACITAVA from the region of Yaigojé lying in Vaupés State launched a legal challenge to Yaigojé’s status at the Colombian Constitutional Court. Led by a local settler named Benigno Perilla, the challengers said that they had not been fully or adequately consulted in the process of creating the national park and it therefore violated their right to Free Prior and Informed Consent.

With an apparently complex conflict unfolding between Yaigojé’s Indigenous Peoples and the area’s national park status–its ecological and social integrity held in the balance–a legal deadlock ensued. This situation persisted for three years, until January 2014, when in an unprecedented move, three judges from Colombia’s Constitutional Court made the decision to travel to the heart of the Colombian Amazon to hold a hearing and consult with communities first hand.

Jorge Iván Palacio, president of the court, explained the court’s decision to make the journey by stating that “there is no justice unless we know what they think in the communities.” The ensuing hearing thoroughly vindicated his observation.

Before 160 indigenous inhabitants from along the Apaporis River and the judges, Benigno Perilla publicly admitted that his and ACITAVA’s legal strategy was encouraged, organized and paid for by Cosigo Resources. In what would prove the critical turning point in the case, the indigenous members of ACITAVA who had supported the challenge made a public apology, said they had been misled and declared their support for the creation of the national park.

A NEW DAWN FOR INDIGENOUS-LED CONSERVATION

Although it has been more than another year coming, the Colombian Constitutional Court has ousted Cosigo and legitimized the declaration of Yaigojé Apaporis as a national park. The decision recognizes the authority of the area’s Indigenous Peoples and protects their fundamental rights to culture, identity and consultation.

The decision is regarded as a significantly positive precedent for future conflicts between mining operations, protected areas and their indigenous inhabitants, at a time when Colombia has declared mining to be in the national interest.

The judges found sufficient evidence of wrongdoing by Cosigo to ask Colombia’s Justice Minister to open an investigation into the company’s consultation processes and interactions with communities in the Yaigojé area. Recently published revisions to Colombia’s projects of national interest have seen Cosigo’s project removed from the list. The company is said to be reviewing its legal options.

Confirming the compatibility of indigenous resguardos and national parks, the court has also opened up the possibility for others to follow Yaigojé’s example and enhance the protection of their territories from destructive or unwanted “development.”

Since Yaigojé was declared a national park, and in spite of the legal wrangle over its future, ACIYA and local indigenous youths have been pioneering a powerful new conservation paradigm that values indigenous knowledge and places it at the root of national park management.

ACIYA’s work to find a method of conservation that both works for them and allows for close collaboration with Colombia’s national park authorities is the subject of a recent film and won the group the prestigious UNDP Equator Prize in 2014. Their approach stands in stark contrast to technocratic, neo-colonialist conservation norms founded on a misplaced belief in pristine, unmanaged wilderness. These have been criticized by Indigenous Peoples and rights groups for excluding and forcibly displacing indigenous communities, fencing them out of their own lands and so obstructing their right to practice their cultures.

As part of their program, 27 young indigenous leaders from nine communities in Yaigojé have engaged in a deep process of cultural research. Advised by their elders, they have documented, mapped and recorded their peoples’ traditional practices for safeguarding and conserving the forest. In the words of one researcher, the aim has been to “transmit traditional knowledge to the younger generations and protect our ancestral territory.” So far, they have succeeded in doing both.

The research produced by ACIYA will now be used to define the management of the Yaigojé Apaporis National Park, further legitimizing local indigenous knowledge systems that have protected the life-support capacities of this rainforest region for generation after generation.

“Indigenous people are the natural allies of the rainforest and the whole environmental movement,” says former director of Gaia Amazonas Martin Von Hildebrand. “They have the traditional knowledge, they are organized. We just need to support them with what they need to run their own territories.”

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Oct 7, 2015 | Indigenous Autonomy, The Solution: Resistance

By Intercontinental Cry

Territories of Life is a video toolkit with a purpose. It’s aim: to bring stories of resistance, resilience and hope to indigenous communities on the frontline of the global rush for land.

Produced by our friends at LifeMosaic, a non-profit based in Scotland, the Territories of Life toolkit consists of ten stories that were filmed in communities across Indonesia, Philippines, Guatemala, Ecuador, Colombia, Paraguay, Tanzania and Cameroon.

“The videos in the Territories of Life toolkit share inspirational stories of communities that are successfully organizing to defend their territories and their futures,” reads a press release from LifeMosaic. They include “The story of Maasai indigenous women in Tanzania who used awareness raising, protests and political pressure to lead a movement in defense of their territory; and the Misak indigenous people in Colombia who have developed and are carrying out their Plan de Vida, a long‐term vision for self-determined development.”

The toolkit also includes a few primers on land rights, land grabs, and common tactics that companies use to convince communities to accept and support their projects.

LifeMosaic goes on to say that, “The video toolkit and accompanying facilitators’ guide are intended to support indigenous peoples as they exercise their right to free, prior and informed consent; advocate for their rights; participate more actively in local spatial planning; and draw up village action plans for self‐determined development and for protecting their territories, forests and resources.”

It’s more than mere lip service. LifeMosaic is actively working with hundreds of local partners to facilitate the free distribution of Territories of Life to indigenous communities and supporting organizations around the world.

To order a copy of the toolkit, visit www.lifemosaic.net. If other groups request a DVD, LifeMosaic recommends a donation of $11 (£10). The videos can also be downloaded online at their website.

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Sep 18, 2015 | Indigenous Autonomy

By Robin Llewellyn / Intercontinental Cry

Children of the Wounaan People easily find diversion in the abandoned basketball stadium of Buenaventura, the largest city on Colombia’s Pacific coast. Some chase pigeons that try to settle around the highest rows of seats, casually resting to look out over the surrounding rooftops to the islands of mangrove and forest that bar the view to the sea. Others jump skipping ropes as two siblings ride brightly-coloured toy ponies past the plastic sheeting beneath the bleachers that grant each family their privacy.

Displacement from their territory has exacted a cruel cost. Two children have died since their community of Unión Aguas Claras was forced to flee ten months ago: one year-old Neiber Cárdenas Pirza died while suffering diarrhoea and vomiting last December, then in June the community lost a two day-old baby.

According to one of the displaced Wounaan it is “all the chemicals” in their new life that are to blame, coupled with the inadequate diet provided by Colombian authorities that leave them vulnerable to sickness. The concrete structure of the basketball stadium is also less hygienic than the wooden homes in the territory they were forced to abandon, she said.

But to another Wounaan there lies a deeper cause:

It is not just the illnesses of the Occident that have made us so ill. It is because of spiritual sickness; because of the loss of our spirituality.

He claimed that the deadly sickness in June was foreseen by their shaman, who had been unable to predict whether it would kill an adult or a child.

The community was preparing for a ceremony the following day in which they would use their spirits to “see” how affairs stood in their territory that has lain abandoned for nine months.

The pressures against them had been manifesting for years, the Wounaan told IC, through the armed conflict, petrol exploration, and narco-trafficking.

“The area is very strategic: the river marks the frontier of the FARC and the paramilitaries, and is also the means by which the Army moves,” One Wounaan explained. “Now all of the Rio San Juan has become militarized.”

In 2008 there was a massacre of six indigenous people in our territory. By 2014 we realized that we couldn’t resist any longer; we couldn’t move in our territory for all the armed groups passing through, we had to stay in our houses.

By November 2014, the harassment was no longer confined to their wider territory. A Wounaan woman explained that, one day, “Six paramilitaries arrived and asked to sleep in the settlement but the community replied that they could not; we said that we reserve the right to say no to all armed groups.”

That evening the local head of the paramilitaries arrived to threaten the assembled community, warning them that their attitude could only work to turn over their territory to other armed groups. Fearful for their safety, the people of Unión Aguas Claras resolved to leave together. A total of 344 people–63 families–boarded boats before dawn and descended the San Juan River to where it joins the lower Calima River. From there, they reached the estuary and followed the coast to Buenaventura, where Colombian authorities placed them in a stadium that only recently became vacant. Shortly before the Wounaan’s arrival, it sheltered Afro-Colombian and campesino families displaced by clashes in Bajo Calima between the Armed Forces and BACRIM (“bandas criminales” – armed criminal bands mostly born out of officially disbanded right-wing paramilitary groups).

Not a single person from the community stayed back. Describing how the community fished and grew “yucca, bananas, pineapples… everything”, one Wounaan lamented, “Now there will be nothing left of our farms; back there in our territory everything will be destroyed.”

When they were in their territory, all the women would gather every two months to prepare and weave threads extracted from the Werregue Palm into baskets and handicrafts that they would sell. The community would hold meetings to arrange days of minga, collective communal work that could involve tidying the territory or arranging the sewing of seeds in their farms. They also said that they carefully guarded their culture, one person stating unequivocally that, “He who does not speak Wounaan is not a Wounaan.”

The Wounaan language is now spoken in many of Colombia’s biggest cities, including Bogota, Medellin and Cali, where many Wounaan end up after being cleared from their homelands in the Pacific regions of the Valle del Cauca and Choco departments. Throughout 2014, Colombia’s National Victims’ Unit recorded 97,453 cases of forced displacement, with the Pacific region among the most impacted.

Wellington Carneiro of Buenaventura’s UNHCR office says there have been “several displacements of indigenous Wounaan communities [including] Balsalito, Chachajo, Chamapuro, Buenavista, Tio Cirilio, and Agua Clara, and recently the Papayo community. In total more than 1000 people have been displaced from the Lower San Juan River.”

The identity of the groups fighting for control of the San Juan and Calima waterways is unclear. The local authorities in Buenaventura initially responded to the community’s arrival by claiming there had been no need for the Wounaan’s displacement, and their territory was safe for their return.

However, according to Carneiro,

The Lower San Juan river is strategic to armed groups due to the access to the sea and for the trafficking of weapons and drugs. Also, with the tighter security implemented around the port of Buenaventura, the routes through the San Juan delta became more attractive. There are several groups disputing the control of the area apart from the Colombian Navy. This…puts the population under the pressure of armed groups for information and through restrictions to their mobility and other threats in the context of a disputed military control over the area.

Colombia has been wracked by a conflict between two competing drug-trafficking networks – the rising Urabeños and the declining Rastrojos – who each seek to monopolize the transport of cocaine via the Pacific coast. Confronted by a stubborn Rastrojos presence in Cali and Buenaventura, the Calima and San Juan rivers have become more strategic as the San Juan is fed by the Capomá river that provides a route into the Colombian interior.

The area has also seen BACRIM and guerrilla groups diversify their enterprises through illegal mining, timber, and agriculture. According to one of the displaced Wounaan, such activities of illegal armed groups are only one aspect of a broader war against indigenous territories across Colombia. He also warned that this broader conflict will not cease with the possible signing of a peace accord between the government and FARC guerrillas.

We will continue to face war. It may be a war without lead against the indigenous – a psychological war, a cultural war, or possibly also a physical war… We know that the peace process will open the way for megaprojects that will bring international investments into our territory, therefore we know that true peace will not come. For indigenous peoples the violence will not end with the peace process. The peace process will not resolve anything for us.

The peace negotiations have been proceeding in Havana, Cuba, despite the intense opposition of former president Alvaro Uribe and his powerful Centro Democratico party. An agreement is expected to be announced in the coming months, to be followed by a reworking of the country’s 1991 Constitution.

Another Wounaan commented,

Uribe has proposed that constitutional reform should proceed and constitutional reform will likely follow a peace accord. Indigenous people are totally unprepared and un-mobilized to participate in the process of rewriting the Constitution: we need to organize ourselves to shape this process.

The aims of the Centro Democratico are clear in the Septima Dia broadcasts of Caracol, which are so aggressive against indigenous people, because Centro Democratico wants to exterminate the indigenous movement.

Earlier this year, Caracol, one of Colombia’s leading private TV channels, broadcast a series under its Septima Dia weekly format on Colombia’s Indigenous Peoples, called Disharmonization: the Arrow of the Conflict. The controversial series attacked indigenous justice systems and claimed that indigenous authorities took massacre compensation from their intended recipients, an allegation that was debunked. The series also insinuated that indigenous institutions were supportive of FARC guerrillas, something that Colombian journalist Cesar Gaviria described as but one falsehood in a series “plagued by investigative and journalistic failures”.

Indigenous Nasa activists seeking to recover the La Emperatriz sugar plantation “from its rightful owners” were among those targeted by the series which also served as a platform for Centro Democratico’s Paloma Valencia, who advocates dividing the department of Cauca into two: “One for the indigenous for them to do their strikes, their demonstrations, and their invasions. And one directed towards development where we can have roads, promote investment and where there are dignified jobs for the Caucanos.”

Henry Caballero Fula of the Peace Commission of the Regional Indigenous Council of Cauca (CRIC) has written that the four aims of the Septima Dia broadcasts were to spread the views that:

Indigenous autonomy is something negative; it only helps to corruptly enrich some members, while harming the community in general and the non-indigenous sectors.

It was a mistake for the right to prior consultation to be integrated into the Colombian Constitution since it harms national development.

The indigenous justice system is another mistake in the Colombian Constitution: it is applied against the community and is the base of impunity and immunity for indigenous criminals.

Indigenous people receive many benefits and these are generating breakdown and corruption.

The trajectory of such arguments in Colombia’s current political climate are a pressing danger to Indigenous Peoples, according to the displaced Wounaan who are politically active through the Regional Indigenous Organization of Valle del Cauca (ORIVAC).

On Sept. 15, Feliciano Valencia of Cauca’s Nasa people, one of the most visible indigenous leaders in Colombia, who had addressed delegates of the displaced Wounaan at an ORIVAC conference, was abruptly arrested and imprisoned on charges that were previously dismissed in 2011. The charges stemmed from a 2008 controversy in which an undercover soldier–who had been exposed infiltrating a peaceful protest–was held subject to indigenous justice mechanisms. The CRIC argues that indigenous jurisdiction forms part of the 1991 Constitution, and that the imprisonment of Valencia is a “coup by the state against our Constitutional rights, and revokes the peace treaty that the Constitution of ’91 represents in our history.”

These developments hadn’t yet occurred when IC spoke to the Wounaan in Buenaventura, however, one person concluded that “Indigenous people face an emergency situation throughout the country, not just in the Rio San Juan.”

The Wounaan are now changing their strategy over how to return to their territory, turning away from the municipal and departmental authorities and towards the Ministry of the Interior, the Ombudsman, and the international community.

The municipal authorities are not cooperating with the indigenous people; they always tell lies – they always say they will do something ‘mañana.’ We present our willingness to return but we need guarantees of security and dignity in our territory. Because the local level has not achieved anything we go to the national and international level, including to NGOs and the UN.

The UNHCR’s Wellington Carneiro cautions that the government ministries in Bogota lack a presence in the region and don’t have “a clear picture on the problems of the Wounaan,” however, “there is also a very negative stigmatization of the indigenous communities by the local authorities.”

Photo: Robin Llewellyn

One of the Wounaan observed that local officials “always come and talk, and then afterwards [do] nothing.” She said that her emphasis was on maintaining and developing the cultural and political activities of the group: “We need to strengthen our community so we can defend our territory”.