by DGR News Service | Sep 11, 2023 | ACTION, The Problem: Civilization

Wednesday, September 6, 2023

“Violence on the Land is Violence on our Bodies”: Appalachian Frontline Women’s Divestment Delegation Highlights Dangers of Mountain Valley Pipeline in Meeting with UBS Bank

Joint press release with Divest Invest Protect and The Women’s Earth and Climate Action Network (WECAN) International

SAN FRANCISCO BAY AREA, California— On September 6, a delegation of frontline women leaders from Appalachia and advocates met with UBS Bank to highlight concerns of human rights violations along the Mountain Valley Pipeline, as well as environmental harms in the Appalachian region as a result of the pipeline.

During the meeting, the Appalachian Frontline Women’s Divestment Delegation provided testimony and shared stories, data and research on the multiple ways that the Mountain Valley Pipeline (MVP) and its construction pose a serious threat to communities, water, air quality and the global climate.

Originally expected to be completed in 2018, the MVP Mainline now runs five years behind schedule and $3 billion over budget. UBS Bank is one of the banks financing MVP, and during the meeting, delegates highlighted that since the project’s inception, the joint owners of Mountain Valley Pipeline have sustained financial losses. In May, 2022, RGC Resources, parent company of Roanoke Gas, disclosed a $29.6 million impairment charge on MVP. Similarly, NextEra announced an $800 million loss in February, 2022, and stated that it was reevaluating its investment in MVP. Additionally, Mountain Valley LLC has incurred millions in fines and settlements for environmental violations and billions of dollars’ worth of expenses in legal battles, permit negotiations, and costly construction delays.

Delegation members provided eye witness accounts and detailed information about specific impacts Indigenous communities and communities of color face in regards to the construction and operation of MVP. The pipeline route will go through Black, Indigenous, Latino, and low-income communities across Appalachia who would experience the brunt of environmental injustice. According to the company’s own 2017 Final Environmental Impact Statement, elderly, disabled, poor, and medically underserved residents are over-represented in the path of the project. Pollution caused by pipelines and methane gas infrastructure has been linked to several adverse health effects, including respiratory diseases, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer. The racial inequities that will ensue from the MVP construction route are so indisputable that the Virginia Air Pollution Control Board denied an air permit on environmental justice grounds. Additionally, construction of MVP has already damaged sacred sites on the homeland of the Monacan Indian Nation, Occaneechi, Saponi, and Tutelo tribes, including a burial mound near Roanoke, Virginia, which dates back several thousand years.

In June 2023, a provision in the Fiscal Responsibility Act approved all remaining permits for the Mountain Valley Pipeline. Another provision stripped the judiciary of any authority to assess the legality of the permits, and therefore opportunity for challenges and input from local communities, forcing the U.S. 4th Circuit Court of Appeals to dismiss two long-standing legal challenges against the MVP that had been staving off construction for years. Construction is now moving forward on the MVP Mainline following Congressional intervention deemed unconstitutional by well-regarded legal scholars.

Delegates shared research on how MVP can negatively impact local ecosystems and the global climate. Experts state that MVP will emit over 89 million metric tons of greenhouse gas pollution annually, equivalent to the pollution from 24 average US coal plants. The pipeline route will cut across over 1,000 waterways and harm the ecosystems of multiple species of concern, including six federally endangered or threatened species and an additional four state listed species. The pipeline will also run over terrain susceptible to landslides in an active seismic zone, raising concerns over pipeline ruptures and explosions. Delegates highlighted the August 2023 Notice of Proposed Safety Order by the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) stating that conditions along the MVP may “pose a pipeline integrity risk to public safety, property, or the environment.”

The Appalachian Frontline Women’s Divestment Delegation, organized by the Women’s Earth and Climate Action Network (WECAN) and Divest Invest Protect (DIP) includes: Dr. Crystal A Cavalier, Ed.D, MPA (Occaneechi Band of the Saponi Nation), Adjunct Professor and Co-Founder, 7 Directions of Service; Dr. Emily Satterwhite, Professor and Director of Appalachian Studies (Appalachian Resident); Crystal Mello, Community Organizer, POWHR (Appalachian Resident); Michelle Cook (Diné), Founder of Divest Invest Protect; with Osprey Orielle Lake, Founder and Executive Director of Women’s Earth and Climate Action Network (WECAN).

“Violence on the land is violence on our bodies. MVP is literally a death sentence for many in our communities and region, threatening our health and livelihoods. Our communities are disproportionately burdened with health hazards through policies and practices that force us to live near sources of toxic waste, such as pipelines, sewage works, mines, landfills, power stations, compressor stations, major roads, and emitters of airborne particulate matter. As a result, our communities suffer higher rates of health problems attendant on hazardous pollutants.” Dr. Crystal A Cavalier, Ed.D, MPA (Occaneechi Band of the Saponi Nation), Adjunct Professor and Co-Founder, 7 Directions of Service

“Mountain Valley Pipeline, a fly-by-night LLC is incapable of construction in compliance with environmental laws. MVP’s leadership clearly has no idea what they’re doing— but that hasn’t stopped them from rushing to place corroded and defective pipes in our land and water before PHMSA’s Notice of Proposed Safety Order can take effect. MVP is putting our lives at risk and then prosecuting us in the courts for trying to protect ourselves.” – Dr. Emily Satterwhite, Professor and Director of Appalachian Studies (Appalachian Resident)

“We’ve been devastated by the forward progress of the Mountain Valley Pipeline. We’re being sacrificed and it’s hard to imagine at times that this is even real. We’re literally in the fight for our lives – The struggle for my home, the struggle for clean air and water, the struggle for the planet, it’s a constant stresser in my life and in the lives of others in my community. We’ll never give up on protecting our home.” Crystal Mello, Community Organizer, POWHR (Appalachian Resident)

“The Appalachian Mountains, the oldest mountains in the world, her peoples, and countless other species, are under an urgent threat from the Mountain Valley Pipeline (MVP). We call for everyone to listen to the Mountains; the river’s babbling brook; the Fish; the Black Bear; the Hell Bender; and Falcon, and even the stones. Life itself cries out for urgent intervention against risks of fire and catastrophic explosions; their siren song sings screaming, Stop the Mountain Valley Pipeline. Our peoples of Appalachia were not created to be sacrificed to their altars of money and profit. Our peoples of Appalachia were not created to serve corporate extractivists agendas that destroy our bodies, health, water, and lands. We will protect our Mother the Mountain and we will protect one another. Our Mother the Mountain, she who is worthy of adoration and defense. The berry jewels of her forests, her glittering crystal silver waters, her golden harvests of grain and corn. She provides all we need for eternity and only requires respect for this opulence. UBS in this historic moment needs to do their due diligence to prevent risks relating to their financing; to respect internationally recognized human rights obligations to both people, planet, and the earth’s biodiversity.” – Michelle Cook (Diné), Founder of Divest Invest Protect

“The Mountain Valley Pipeline will have disastrous impacts for frontline communities who will experience the worst of fossil fuel pollution, for biodiverse species whose very habitats will be destroyed, and for our global climate which cannot take another pipeline project. It is time to end the era of fossil fuels for the health of our communities and planet. We must stop the very worst of the climate crisis before it is too late. We are calling for financial institutions to listen to communities and science, conduct thorough due diligence, and stop the harms of fossil fuel extraction. UBS and other banks have an opportunity to be leaders in the just transition by divesting from fossil fuels and instead financing projects that support the well-being of communities, ecosystems, and our planet. Now is the time for financial institutions to firmly respect international human rights standards and climate agreements as we collectively move towards a clean, just, and healthy future for all. There is no time to lose!” – Osprey Orielle Lake, Founder and Executive Director of Women’s Earth and Climate Action Network (WECAN)

MEDIA CONTACT

Katherine Quaid, WECAN International, katherine@wecaninternational.org

Michelle Cook, Divest Invest Protect, divestinvestprotect@gmail.com

This press release is also available online.

Photo by Elijah Mears on Unsplash

by DGR News Service | Jul 4, 2021 | Direct Action, Property & Material Destruction, Repression at Home

For Immediate Release Thursday, July 1st, 2021

Editor’s note: If anyone should still have any doubts that we are living in CORPORATE FASCISM, this is imminent proof.

From the statement by Jessica and Ruby when they openly admitted and took full credit for carrying out eco-sabotage:

“Some may view these actions as violent, but be not mistaken. We acted from our hearts and never threatened human life nor personal property,” Montoya said. “What we did do was fight a private corporation that has run rampant across our country, seizing land and polluting our nation’s water supply. You may not agree with our tactics, but you can clearly see their necessity in light of the broken federal government and the corporations they represent.”

Contact: freejessicareznicek@gmail.com

Des Moines, IA –On Wednesday Federal Judge Rebecca Goodgame Ebinger sentenced Jessica Reznicek to 8 years in prison, followed by 3 years supervised probation, and a restitution of $3,198,512.70 paid to Energy Transfer LLC for the actions she took in 2016 to stop the Dakota Access Pipeline.

“I am saddened to be preparing for prison following today’s sentencing hearing. My spirit remains strong, however, as I feel held in love, support and prayer by so many near and far. Regardless of my sentence I am hopeful that movements to protect the water live on in the struggles against Line 3 and the Mountain Valley Pipelines.”

Jessica Reznicek

The judge sided with the Federal prosecutors and applied a domestic terrorism enhancement to Jessica’s case. The enhancement originated in the Bush era Patriot Act, which expanded the definition of terrorism to cover “domestic,” as opposed to international, terrorism. Theprosecutor requested the enhancement claiming that Jessica’s acts of resistance were “violent”, “dangerous”, and sought to “intimidate the government”. The judge decided that this argument provided enough evidence to substantiate the enhancement, saying it was necessary to discourage others from taking similar actions.

The enhancement increases Jessica’s sentence, but also has far reaching implications for broader social justice movements. This use of this enhancement interprets non-violent actions that challenge corporate profit as acts of terror against the government.

On today’s decision one of Jessica’s attorneys Bill Quigley stated, “Unfortunately, actions to protect our human right to water were found to be less important than the profit and property of corporations which are destroying our lands and waters. For a country which was founded by the rebellion of the Boston Tea Party this is extremely disappointing. But the community of resistance will no doubt carry on. And history will judge if Jessica Reznicek is a criminal or a prophet. Many of us are betting she’s a prophet.”

In her statement to the court Jessica highlighted how the water system for her hometown of Des Moines is on the verge of collapse. The city water department has admitted that both the Des Moines and Racoon rivers are so polluted and low that in the upcoming weeks they might not be able to continue to use them to supply the capital with drinking water. Meanwhile “victim” in this case Energy Transfer Partners and its subsidiaries are responsible for 313 reported spills since 2012 on liquid lines, 35 caused water contamination. In the last 5 years the company had more accidents harming people or the environment than any other operator.

Jessica will remain on house arrest until she has to self-report for her sentence and plans to file an appeal within the 14 day window allowed by the court.

###

#FreeJessica #WaterIsLife #NoDAPL

Frank Cordaro

cell 515 490 2490

DMCW You Tube beg ( 2 min 40 sec).

https://youtu.be/1Yb-wWYtjrM

Link to DMCW Paypal

https://paypal.me/dmcatholicworker?locale.x=en_US

1976-2020 via pacis archives

https://viapacis.wordpress.com/

Frank Cordaro’s Writings and Archives by yr 1976 – 2020

https://frankcordaro.wordpress.com/

FC’s FB page

https://www.facebook.com/frank.cordaro

by DGR News Service | May 4, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Climate Change, Listening to the Land, Mining & Drilling, Movement Building & Support, Toxification

In this article Rebecca Wildbear talks about how civilization is wasting our planet’s scarce water sources for mining in its desperate effort to continue this devastating way of life.

By Rebecca Wildbear

Nearly a third of the world lacks safe drinking water, though I have rarely been without. In a red rock canyon in Utah, backpacking on a week-long wilderness training in my mid-twenties, it was challenging to find water. Eight of us often scouted for hours. Some days all we could find to drink was muddy water. We collected rain water and were grateful when we found a spring.

Now water is scarce, and the demand for it is growing. Globally, water use has risen at more than twice the rate of population growth and is still increasing. Ninety percent of water used by humans is used by industry and agriculture, and when groundwater is overused, lakes, streams and rivers dry up, destroying ecosystems and species, harming human health, and impacting food security. Life on Earth will not survive without water.

In the Navajo Nation in Arizona, Utah, and New Mexico, a third of houses lack running water, and in some towns, it is ninety percent. Peabody Energy Corporation, the largest coal producer and a Fortune 500 company, pulled so much water from the Navajo aquifer before closing its mining operation that many wells and springs have run dry. Residents now have to drive 17 miles to wait in line for an hour at a communal well, just to get their drinking water.

Worldwide, the majority of drinkable water comes from underground reservoirs called aquifers. Aquifers feed streams, lakes, and rivers, but their waters are finite. Large aquifers exist beneath deserts, but these were created eons ago in wetter times. Expert hydrologists say that like oil, once the “fossil” waters of ancient reservoirs are mined, they are gone forever.

Peabody’s Black Mesa Mine extracted, pulverized, and mixed coal with water drawn from the Navajo aquifer to form a slurry. This was sent along a 273-mile-long pipeline to the Mojave Generating Station in Laughlin, Nevada, to power Los Angeles. Every year, the mine extracted 1.4 billion gallons (4,000+ acre feet) of water from the aquifer, an estimated 45 billion gallons (130,000+ acre feet) in all.

Pumping out an aquifer draws down the water level and empties it forever. Water quality deteriorates and springs and soil dry out. Agricultural irrigation and oil and coal extraction are the biggest users of waters from aquifers in the U.S. Some predict that the Ogallala aquifer, once stretching beneath five mid-western states, may be able to replenish after six thousand years of rainfall.

Rain is the most accurate measure of available water in a region, yet over-pumping water beyond its capacity to refill is widespread in the western U.S. and around the world. The Middle East ran out of water years ago—it was the first major region in the world to do so. Studies predict that two thirds of the world’s population are at risk of water shortages by 2025. As ground water levels fall, lakes, rivers, and streams are depleted, and the land, fish, trees, and animals die, leaving a barren desert.

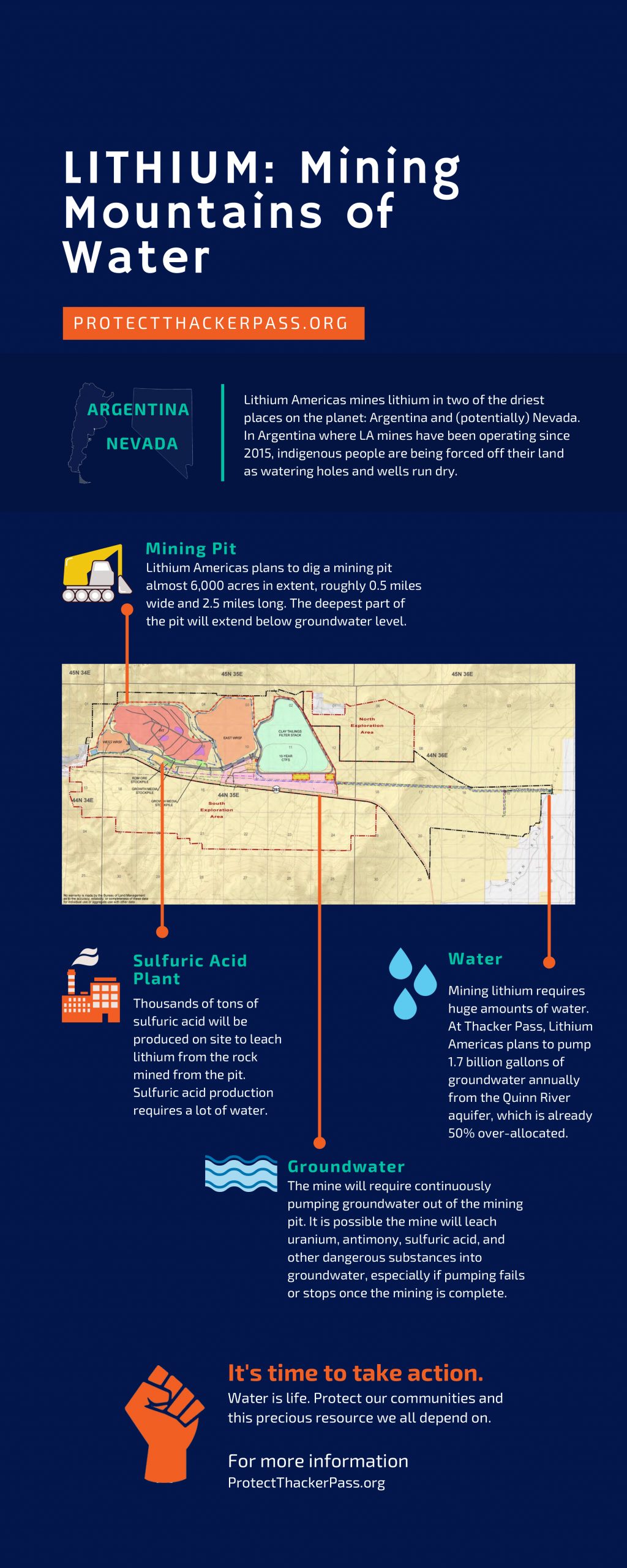

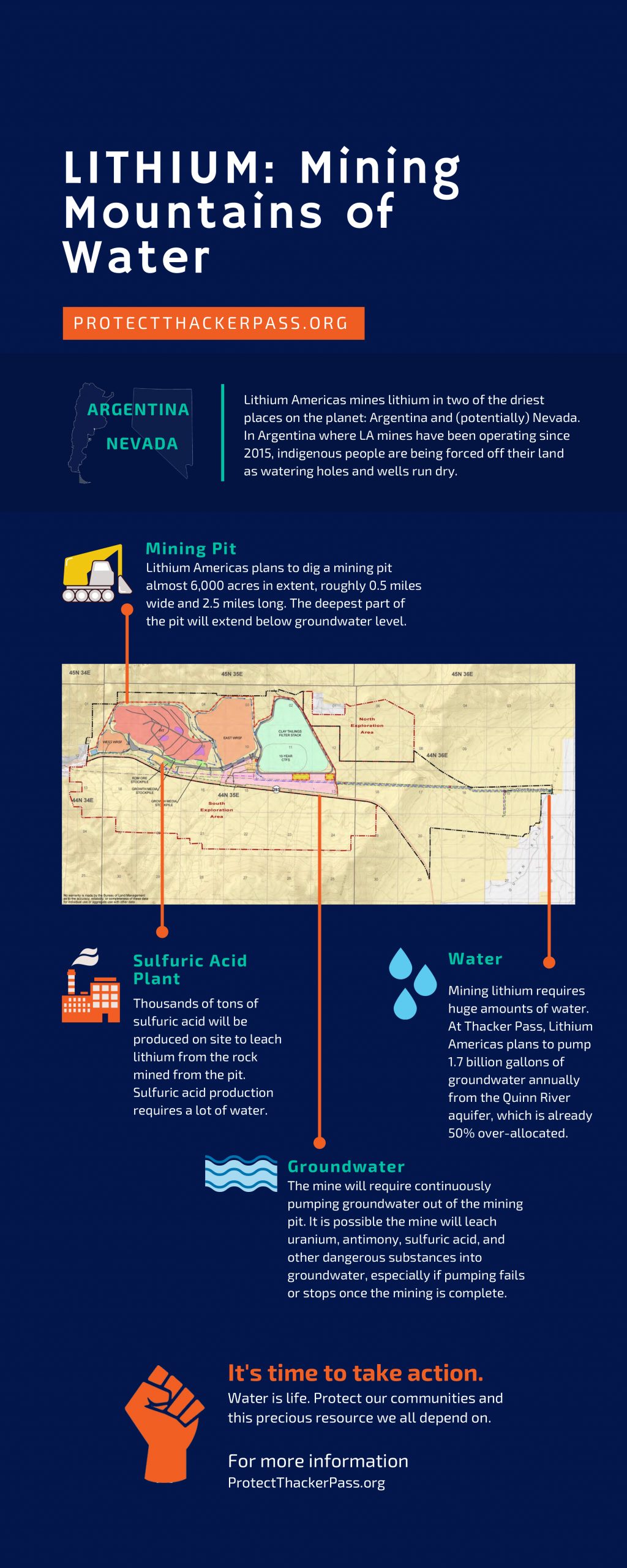

Mining in the Great Basin

The skyrocketing demand for lithium, one of the minerals needed for the production of electric cars, is based on the misperception that green technology helps the planet. Yet, as Argentine professor of thermodynamics and lithium mining expert Dr. Daniel Galli said at a scientific meeting, lithium mining is “really mining mountains of water.” Lithium Americas plans to pump massive amounts of water—up to 1.7 billion gallons (5,200 acre feet) annually—from an aquifer in the Quinn River Valley in Nevada’s Great Basin, the largest desert in the United States.

Thacker Pass, the site of the proposed 1.3 billion dollar open-pit lithium mine, would pump 1,200 acre feet more water per year than Peabody Energy Corporation extracted from the Navajo aquifer. Yet, the Quinn River aquifer is already over-allocated by fifty percent, and more than 10 billion gallons (30,000 acre feet) per year. Nevada is one of the driest states in the nation, and Thacker Pass is only the first of many proposed lithium mines in the state. Multiple active placer claims (7,996) have been located in 18 different hydrographic basins.

Deceit about water fuels these mines. Lithium Americas’ environmental impact assessment is grossly inaccurate, according to hydrologist Dr. Erick Powell. By classifying year-round creeks as “ephemeral” and underreporting the flow rate of 14 springs, Lithium Americas is claiming there is less water in the area than there actually is. This masks the real effects the mine would have—drying up hundreds of square miles of land, drawing down the groundwater level, sucking water from neighboring aquifers—all while claiming its operations would have no effect.

Peabody Energy Corporation’s impact assessment similarly misrepresented how their withdrawals would harm the Navajo aquifer. Peabody Energy used a flawed method to measure the withdrawals, according to former National Science Research Fellow Daniel Higgins. Now Navajo Nation wells require drilling down 2,000–3,000 feet, and the water is depressurized and slow to flow to the surface.

Thacker Pass lithium mine would pump groundwater at a disturbing rate, up to 3,250 gallons per minute. Once used, wastewater would contaminate local groundwater with dangerous heavy metals, including a “plume” of antimony that would last at least 300 years. Lithium Americas plans to dig the mine deeper than the groundwater level and keep it dry by continuously pumping water out, but when the pumping stops, groundwater would seep back in, picking up the toxins.

It hurts me to think about this. I imagine water being rapidly extracted from my own body, my bloodstream poisoned. The best tasting water rises to the surface when it is ready, after gestating as long as it likes in the dark Earth. Springs are sacred. When I feel welcome, I place my lips on the earthy surface and fill my mouth with their sweet flavor and vibrant texture.

Mining in the Atacama Desert

Thirteen thousand feet above sea level, the indigenous Atacamas people live in the Atacama Desert, the most arid desert in the world and the driest place on Earth. For millennia, they have used their scarce supply of water and sparse terrain carefully. Their laws and spirituality have always been intertwined with the health and well-being of the land and water. Living in mud-brick homes, pack animals, llama and alpaca, provide them with meat, hide, and wool.

But lithium lies beneath their ancestral land. Since 1980, mining companies have made billions in the Salar de Atacama region in Chile, where lithium mining now consumes sixty-five percent of the water. Some local communities need to have water driven in, and other villagers have been forced to abandon their settlements. There is no longer enough water to graze their animals. Beautiful lagoons hundreds of flamingos call home have gone dry. The birds have disappeared, and the ground is hard and cracked.

In addition to the Thacker Pass mine proposal, Lithium Americas has a mine in the Atacama Desert, a joint Canadian-Chilean venture named Minera Exar in the Cauchari-Olaroz basin in Jujuy, Argentina. Digging for lithium began in Jujuy in 2015, and there is already irreversible damage, according to a 2018 hydrology report. Watering holes have gone dry, and indigenous leaders are scared that soon there will be nothing left.

Even more water is needed to mine the traces of lithium found in brine than in an open-pit mine. At the Sales de Jujuy plant, the wells pump at a rate of more than two million gallons per day, even though this region receives less than four inches of rain a year. Pumping water from brine aquifers decreases the amount of fresh groundwater. Freshwater refills the spaces emptied by brine pumping and is irreversibly mixed with brine and salinized.

The Sanctity of Water

As a river guide, I live close to water. Swallowed by its wild beauty, I am restored to a healthier existence. Far from roads, cars, and cities, I watch water swirl around rocks or ripple over sand. I merge with its generous flow, floating through mountains, forest, or canyon. Rivers teach me how to listen to the currents—whether they cascade in a playful bubble, swell in a loud rush, or ebb in a gentle silence—for clues about what lies ahead.

The indigenous Atacamas peoples understand that water is sacred and have purposefully protected it for centuries. Rather than looking at how nature can be used, our culture needs to emulate the Atacamas peoples and develop the capacity to consider its obligations around water. Instead of electric cars, what we need is an ethical approach to our relationship with the land. Honoring the rights of water, species, and ecosystems is the foundation of a sustainable society. Decisions can be made based on knowledge of the land, weather patterns, and messages from nature.

For millennia, indigenous peoples have perceived water, animals, and mountains as sentient. If humans today could recognize their intelligence, perhaps they would understand that underground reservoirs have a value and purpose, beyond humans. When I enter a cave, I am walking into a living being. My eyes adjust to the dark. Pressing my hand against the wall, I steady myself on the uneven ground, hidden by varying amounts of water. Pausing, I listen to a soft dripping noise, echoing like a heartbeat as dew slides off the rocks. I can almost hear the cave breathing.

The life-giving waters of aquifers keep everything alive, but live unseen under the ground. As a soul guide, I invite people to be nourished by the visions of their dreams, a parallel world that is also seemingly invisible. Our dominant culture dismisses the value of these perceptions, just as it usurps water by disregarding natural cycles. Yet to create a sustainable world, humans need to be able to listen to nature and their dreams. The depths of our souls are inextricably linked to the ancient waters that flow underground. Dreams arise like springs from an aquifer, seeding our visionary potential, expanding our consciousness, and revealing other ways to live, radically different than empire.

Water Bearers

I set my backpack down on a high sandstone cliff overlooking a large watering hole. Ten feet below the hole, the red rock canyon drops into a much larger pool. My friend hikes down to it, filling her cookpot with water. She balances it atop her head on the way up, moving her hips to keep the pot steady. Arriving back, she pours the water into the smaller hole from which we drink and returns to the large pool to gather more.

Women in all societies have carried water throughout history. In many rural communities, they still spend much of the day gathering it. Sherri Mitchell of the Penobscot Nation calls women “the water bearers of the Universe.” The cycles in a woman’s body move in relation with the Earth’s tides, guiding them to nourish and protect the waters of Earth. We all need to become water bearers now.

Indigenous peoples, who have always been the Earth’s greatest defenders, protect eighty percent of global diversity, even though they comprise less than five percent of the world’s population. They understand water is sacred, and the world’s groundwater systems must be defended. For six years, indigenous peoples have been fighting to prevent lithium mining in the Salinas Grandes salt flats, in Jujuy, Argentina. Five hundred indigenous people camped on the land with signs: “No to lithium. Yes, to water and life in our territories.”

In February 2021, President Biden signed executive orders supporting the domestic mining of “critical” minerals like lithium, but two lawsuits, one by five Nevada-based conservation groups, have been filed against the Bureau of Land Management for approving the Thacker Pass lithium mine. Environmentalists Max Wilbert and Will Falk are organizing a protest to protect Thacker Pass. Local residents, including Northern Paiute and Western Shoshone peoples, are speaking out, fighting to protect their land and water.

We can see when a river runs dry, but most people are not aware of the invisible, slow-burning disaster happening under the ground. Some say those who oppose lithium mining should give up cell phones. If that is true, perhaps those who favor mines should give up drinking water. Protecting water needs to be at the center of any plan for a sustainable future.

The “fossil water” found in deserts should be used only in emergency, certainly not for mining. Sickened by corporate water grabbing, I support those trying to stop Thacker Pass Lithium mine and aim to join them. The aquifers there have nurtured so many for so long—eagles, pronghorn antelope, mule deer, old-growth sagebrush, hawks, falcons, sage-grouse, and Lahontan cutthroat trout. I pray these sacred wombs of the Earth can live on to nourish all of life.

For more on the issue:

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jun 17, 2013 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Colonialism & Conquest, Indigenous Autonomy, Strategy & Analysis

nBy Michael Carter, Deep Green Resistance Colorado Plateau

The Pipeline Proposal

The Great Basin stretches from Utah’s Great Salt Lake to the Sierra Nevada Mountains and from southern Idaho to southern California. About seven inches of rain falls in Nevada a year, and some areas receive less than five. The Great Basin is a cold desert, and in eastern Nevada and western Utah, it has been getting drier for a decade. [1]

The Southern Nevada Water Authority (SNWA), the water agency for Las Vegas, Henderson, and North Las Vegas, proposes pumping up to 200,000 acre-feet annually from eastern to southern Nevada through 300 miles of pipeline. An acre-foot is enough water to cover an acre of land a foot deep, or about 325,850 US gallons. Cost estimates vary from $3.5 billion (what SNWA tells the public) to $15 billion dollars (what SNWA was required by law to tell the State Engineer). This project is seen as a threat by several Indian tribes and rural communities, and is expected to do immense damage to many rare endemic species, desert vegetation, and the land itself, much of which is open range. [2]

Basin and Range

Life in the Great Basin’s valleys, human and otherwise, depends on shallow groundwater, springs, and creeks, which in turn depend on groundwater flows from rain and snow in mountain ranges. 200,000 acre-feet is about 65 billion gallons of water, equivalent to the average flow of Nevada’s Humboldt River. SNWA claims that it can pump this water from the Spring, Delamar, Dry Lake, and Cave Valleys without harm; though it’s clear to those who live in the Great Basin that if most of the water flowing in from the mountains is drawn away, eventually most everything in the valleys will die.

The Bureau of Land Management’s final decision on the right-of-way for the project [3] allows for the pumping of 150,000 annual acre-feet. [4] A drawdown projection commissioned by the Goshute Tribe [5] (and other analyses) reflect a far more destructive outcome than the SNWA claims. Access to Snake Valley (much of which is in Utah) groundwater is still in dispute, but the US Geological Survey has concluded the multiple valleys’ aquifers are connected, so it’s likely that Utah’s groundwater would be impacted anyway. [6]

According to the Great Basin Water Network, “Independent hydrologists dispute it is possible to pump and export so much water without causing major environmental degradation and destroying the livelihoods of rural residents in eastern Nevada and western Utah. The area targeted for the massive pumping proposal is home to National Wildlife Refuges… Great Basin National Park is surrounded by the proposed groundwater pump and export project. The proposed pumping scheme would bring two hundred or more wells with power lines, roads, and linked buried pipelines to cover the valleys on both sides of the National Park—some right on the border of the park.

Communities like Baker, Nevada on the Utah border would have large production wells in their backyard sending local water to a city 300 miles away.” [7] As pipeline foe Rick Spilsbury puts it, “This would mean the end of any economic development anywhere near the drained areas. The likely result would be a mass emigration and the eventual transformation of the area into a national toxic dump site.” Impacts to land, water, and air could extend as far as Salt Lake City and its surrounding urban areas (which already have some of the worst air pollution in the US). Physicians for Social Responsibility predicts a dewatered basin-and-range country could increase downwind particulate pollution from dust storms, including the toxic mineral erionite. [8] In textbook fashion, the city of Las Vegas is exporting suffering and violence to import resources that it cannot acquire in its immediate landbase.

Overdrawn River

Author Marc Reisner wrote, “To some conservationists the Colorado River is the preeminent symbol of everything mankind has done wrong—a harbinger of a squalid and deserved fate. To its preeminent impounder, the US Bureau of Reclamation, it is the perfection of an ideal.” [9] In 2013, American Rivers announced the Colorado as the US’s most endangered river, and that “over-allocation and drought have placed significant stress on water supplies, river health, and fish and wildlife. To underscore the immediacy of the problem, the basin is facing another drought this summer. The Bureau of Reclamation’s report released in December stresses that there is not enough water to meet current demands across the basin, let alone support future demand increases.” [10]

Under the interstate Colorado River Compact of 1922, the entire state of Nevada was allowed 300,000 acre feet per year (AFY) of Colorado River water. One AFY is approximately 3380 liters per day, “the planned water usage of a suburban family household, annually. In some areas of the desert Southwest, where water conservation is followed and often enforced, a typical family uses only about 0.25 [AFY].” [11] The Imperial Irrigation District, whose water rights predate the 1922 Compact, owns approximately three million acre feet (MAF) per year, and the entire city of Los Angeles uses about one MAF per year. Though laws controlling the use of water are typically state, not federal, and vary widely from state to state (in Arizona, for instance, there is little legally recognized relationship between ground and surface water), the 1922 Compact is a binding agreement between states. The Upper Basin must deliver a total of 7.5 MAF per year to the Lower Basin (the dividing line is at Lee’s Ferry in Glen Canyon, in Utah), and the US must deliver one MAF a year to Mexico. [12] Across the entire Colorado River basin, nearly all climate models predict an increase in both aridity and flooding. [13]

As increasing temperatures force the jet stream further north and more water evaporate from soil and reservoirs like Lake Powell (where an average 860,000 acre-feet of water—about 8 percent of the Colorado River’s annual flow—is lost every year) [14], overall water availability will decrease even if summer storms and spring runoff paradoxically become more intense. 2012 was the first recorded year the Colorado River flow peaked in April. [15] Though the water level in Lake Mead (where Las Vegas siphons its water from) has priority over Lake Powell’s (upstream), Las Vegas has little water from the river’s apportionment overall because in 1922, when the Compact was made, there were very few people in Nevada and no guess at what Las Vegas might become.

Southern Nevada at one point had the highest growth rate in the US, but following the economic recession Nevada had the highest national rate of foreclosures, bankruptcies, and unemployment. In 2010, there were 167,564 empty houses in Nevada—one in seven. In Las Vegas, residential property prices have fallen by 50 percent on average from 2008 to 2011, when Nevada homes changed hands for an average of $115,000. [16] As one SNWA pipeline opponent remarked, “My house in Las Vegas dropped from $307,500 to be foreclosed, and then resold at $190,000.”

When the SNWA groundwater pipeline was first conceived, the water agency was planning for growth on a much higher trajectory, and this momentum has carried through the recession to the present day. So while southern Nevada’s water future in general is threatened by drought and Nevada’s small original apportionment, the groundwater pipeline is driven by hopes for future growth, not immediate need. [16]

Indigenous Human Rights

The Confederated Tribes of the Goshute, or CTGR (the name “Goshute” derives from the native word Ku’tsip or Gu’tsip, people of ashes, desert, or dry earth), [17] “reside in an isolated oasis in the foothills of the majestic Deep Creek Mountains on what is now the Utah/ Nevada state line,” according to their web page Protect Goshute Water. There are 539 enrolled tribal members, and about 200 of them live in Deep Creek Valley. “Our reservation lies in one of the most sparsely populated regions of the United States, and it has always been our home. Resulting from this isolation, we have benefited by retaining strong cultural ties to Goshute land, our traditions, and a resolute determination to protect our ways.

Ironically, water, the most elemental resource in our basin, is the very thing developers now seek to extract and send 300 miles away for Las Vegas suburbs. The Southern Nevada Water Authority’s pipeline proposal would draw 150,000 acre feet per year from the Great Salt Lake Watershed Basin lowering the water table, drying up our springs, and fundamentally changing access to water over this vast region for plants, wildlife, and people.” They go on to say that “SNWA’s groundwater development application is the biggest threat to the Goshute way of life since European settlers first arrived on Goshute lands more than 150 years ago.” [18]

In Spring Valley in eastern Nevada, a narrow band of swamp cedar trees mark the site of 1863 and 1897 US military massacres of Goshute and Shoshone peoples, and here is where the Goshute and Duckwater and Ely Shoshone tribes grieve and hold spiritual ceremonies. Goshute tribal chairman Ed Naranjo says that “Swamp Cedars is important to many tribes, certainly to CTGR, Ely, and Duckwater, but also to many Paiute, Shoshone, and Ute Tribes.” The Swamp Cedars Massacre is relatively obscure, compared to well-known massacres at Bear River [19] and Wounded Knee.

Goshute elders believe that murder victims physically and spiritually fed the swamp-cedar trees; according to former Goshute council chairman Rupert Steele, “Otherwise you’d never see swamp cedar grow this tall and strong.” In a 2011 Nevada State Engineer hearing, an SNWA attorney likened the Goshute beliefs to children fearing the bogeyman. The Spring Valley swamp cedar grove is one of many sites that could be drained by the SNWA pipeline. [20] A “Cultural Property and Cultural Landscape” report on Spring Valley, Nevada, prepared by an independent ethnographer for Goshute and Ely and Duckwater Shoshone tribes was ignored by the BLM in their environmental analysis. [21]

Rick Spilsbury, a Shoshone Indian, says that “As far as the Native Americans of Nevada and Utah are concerned, this is just a continuation of the land and resource grab that has existed since the authoring of the Bill of Rights. Those who take have been writing the rules. The Colorado River Compact was organized specifically to exclude Native Americans and Mexicans from having any water rights. And the omission of Federal water protections for Native Americans from State water affairs was obviously not an oversight, or it would have been fixed by now. Native Americans don’t have the legal ability to stop their exploitation. [22]

“The Western Shoshone still hunt and gather here—right where the worst of the environmental damage will be. The mass killing of life in this area will not only be the final blow to Western Shoshone culture, it will be a serious threat to their long-term sustainability—and even viability. Water is life. And SNWA intends to take it.”

Opposition

Not surprisingly, a water appropriation on this scale has been hard fought by those whose livelihoods will be affected, as well as indigenous communities and environmental groups. Even within southern Nevada there’s some rate-payer opposition [23]—the project’s costs will be added to water bills—and Utah’s governor Gary Herbert recently rejected a proposed agreement with the SNWA for Snake Valley groundwater. [24] Litigation on various aspects of this project may well proceed to the US Supreme Court.

(Though Herbert’s decision was widely praised by both West Desert ranchers and environmentalists, not everyone in Utah concurred. Ron Thompson, of the Washington County, Utah, Water Conservancy District, criticized the move as “hypocritical for us to tell Nevada not to develop a water project. Ultimately they will figure out how to do it.” [25] Washington County wants to build its own expensive water pipeline from Lake Powell to the St. George area, and Thompson thinks Governor Herbert is sacrificing a “positive tradition of bi-state cooperation” in turning the SNWA down. A Lake Powell pipeline opponent observed that “It’s imperative that opposition to both projects stays active and coordinated.” [26])

Deep Green Resistance’s Southwest Coalition proposes this strategy:

Though we’re too recently involved to have any legal standing, our emphasis on indigenous solidarity has drawn us to ally ourselves with the affected indigenous groups. Though their governments haven’t agreed to any formal affiliation, we offer them support through:

1. Organizing opposition in communities outside the reservations.

2. Fundraising for efforts to fight the pipeline, whatever that might be. Donations are tax-deductible and can be made by PayPal to deepgreenfertileground@gmail.com. Please put “SNWA” in the comments section. The Great Basin Water Network also accepts donations, at or Great Basin Water Network, P O Box 75, Baker, NV 89311 (Nevada non-profit #35-2278153).

3. Influencing public opinion and promoting taxpayer opposition to the pipeline.

4. Sponsoring educational events and outreach. This might include inviting indigenous people (and supporting travel costs) to events we can organize in Salt Lake City and Las Vegas to speak against the pipeline.

5. Organizing protests and rallies. We can help redefine this issue as one of human rights violation, not only environmental destruction.

6. Encouraging negative press coverage of the SNWA and pipeline proposal. Encouraging positive press coverage of the Great Basin’s unique beauty, and the long indigenous people’s relationship with it.

7. Discouraging project investors/lenders.

8. We can also organize and train for nonviolent civil disobedience to fight the pipeline construction, should legal or administrative efforts fail. This is a tactical tool that’s aimed at physically stopping construction. It’s not symbolic, it’s strategic; there are ways of minimizing the expense and suffering to activists and maximizing expense and delay of the enemy, and we feel it’s best to plan for the unfortunate possibility that this struggle may well arrive at this point. We believe it’s our responsibility as privileged members of the dominant culture to put our bodies between the bulldozers and indigenous peoples and lands.

Miscellaneous Articles

- “Goshutes blast BLM study on Las Vegas water pipeline,” Las Vegas Review-Journal, August 5, 2012, http://www.lvrj.com/news/goshutes-blast-blm-study-on-las-vegas-water-pipeline-165082706.html

- Joe Schoenmann, “Water Authority gets state agency’s backing for pipeline to transport water from Lincoln, White Pine counties,” Las Vegas Sun, September 12, 2012, http://www.lasvegassun.com/news/2012/sep/12/water-authority-gets-state-agencys-backing-pipelin/

- Cy Ryan, “Environmental impact statement issued for proposed water pipeline,” Las Vegas Sun, August 3, 2012, http://www.lasvegassun.com/news/2012/aug/03/environmental-impact-statement-issued-proposed-wat/

- David McGrath Schwartz, “Nevada leaders largely silent on pipeline controversy,” Las Vegas Sun, October 14, 2011, http://www.lasvegassun.com/news/2011/oct/14/nevada-leaders-largely-silent-pipeline-controversy/

- Tara Lohan, “Las Vegas Accused of Engineering Massive Water Grab: Is This the Future of the West?” AlterNet, January 25, 2013, http://www.alternet.org/environment/las-vegas-accused-engineering-massive-water-grab-future-west-photo-slideshow?image-1=11&paging=off

Endnotes

[1] “Great Basin Water Issues,” Great Basin Water Network, accessed December 26, 2012, http://www.greatbasinwater.net/issues/index.php This page offers a good overview of Great Basin water issues, including the SNWA proposed pipeline.

See the U.S. Drought Monitor for current data: The U.S. Drought Monitor. National Drought Mitigation Center at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, United States Department of Agriculture, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. http://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/

[3] Sandra Chereb, “BLM approves Las Vegas water pipeline project,” Las Vegas Review-Journal, December 27, 2012, http://www.lvrj.com/news/blm–approves–las–vegas–water–pipeline–project-184948361.html

“Clark, Lincoln, and White Pine Counties Groundwater Development Project Final EIS,” US DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT, August 3, 2012, http://www.blm.gov/nv/st/en/prog/planning/groundwater_projects/snwa_groundwater_project/final_eis.html

“Clark, Lincoln, and White Pine Counties Groundwater Development Project EIS Record of Decision,” U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT, December 27, 2012, http://www.blm.gov/nv/st/en/prog/planning/groundwater_projects/snwa_groundwater_project/record_of_decision.html

[4] “SNWA appears as if it’s planning on Snake Valley water, said Rob Mrowka of the Tucson-based Center for Biological Diversity.

Despite the fact that the Nevada engineer approved water rights of 84,000 acre feet, he said, the BLM is set to approve a pipeline capable of carrying 117,000 acre feet.” Christopher Smart, “BLM poised to OK Las Vegas plan to pump and pipe desert groundwater,” Salt Lake Tribune, August 6, 2012, http://www.sltrib.com/sltrib/politics/54624691-90/blm–eis–final–las.html.csp

Brian Maffly, “BLM’s decision on Nevada-Utah pipeline called ‘pure folly’; Right of way helps southern Nevada, but Utah’s Snake Valley water not in play—yet,” Salt Lake Tribune, December 28, 2012, http://www.sltrib.com/sltrib/news/55538357-78/nevada–blm–decision–groundwater.html.csp

[5] “Ancestral Lands/Drawdown Scenario Map,” Protect Goshute Water, accessed May 10, 2013

[6] “While the BLM’s final EIS spares Snake Valley along the Utah-Nevada border from groundwater pumping, critics say drilling in nearby valleys will draw down the aquifer beneath Snake Valley,” “Goshutes blast BLM study on Las Vegas water pipeline,” Las Vegas Review-Journal, August 5, 2012, http://www.lvrj.com/news/goshutes–blast–blm–study–on–las–vegas–water–pipeline-165082706.html

[7] “Great Basin Water Issues,” Great Basin Water Network, accessed May 11, 2013, http://www.greatbasinwater.net/issues/index.php

[8]“Dr. Jeff Patterson, president of PSR [Physicians for Social Responsibility], said Westerners should be worried because there is no evidence of any serious attempt to determine if erionite exists in the same areas that would be ‘de-watered by the proposed Las Vegas pipeline and would be kicked up in the particulate pollution. Erionite can cause serious lung disease and a highly lethal cancer called mesothelioma,’” Brian Moench, “No end to Nevada’s quest for water,” Salt Lake Tribune, April 6, 2013, http://www.sltrib.com/sltrib/opinion/56107724-82/utah–nevada–erionite–las.html.csp

[9] Reisner, Marc. Cadillac Desert. New York: Viking Penguin, 1986, 121.

[10] Amy Souers Kober, “Announcing America’s Most Endangered Rivers of 2013,” American Rivers, April 17, 2013, https://web.archive.org/web/20130531040706/http://www.americanrivers.org/newsroom/blog/akober-20130417-announcing-americas-most-endangered-rivers-2013.html

[11] Acre-foot,” Wikipedia, accessed May 14, 2013, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Acre–foot

[12] The Colorado River is managed and operated under numerous compacts, federal laws, court decisions and decrees, contracts, and regulatory guidelines collectively known as ‘The Law of the River,’” “Colorado River Compact,” Wikipedia, accessed May 14, 2013, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colorado_River_Compact

[13] Melanie Lenart, “Precipitation Changes,” Southwest Climate Change Network, September 18, 2008, http://www.southwestclimatechange.org/node/790#references

Gregory J. McCabe, David M. Wolock, “Warming may create substantial water supply shortages in the Colorado River basin,” Geophysical Research Letters, Volume 34, Issue 22, November 27, 2007, http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2007GL031764/abstract;jsessionid=400E4E84287315178759E2F3CEDCB107.d02t03

[14] “Glen Canyon Dam,” Wikipedia, accessed December 10, 2012, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glen_Canyon_Dam

[15] COLORADO BASIN RIVER FORECAST CENTER , NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE / NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION, accessed May 11, 2013, http://www.cbrfc.noaa.gov/rmap/peak/peakpoint.php?id=CCUC2

[16] Nick Allen, “Las Vegas: how the recession has hit Sin City,” The Telegraph, May 16, 2011, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/northamerica/usa/8517423/Las-Vegas-how-the-recession-has-hit-Sin-City.html

[17] The Confederated Tribe of the Goshute. Pia Toya: A Goshute Indian Legend. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2000.

[18] “The Confederated Tribes of the Goshute Reservation,” Protect Goshute Water, accessed May 15, 2013

[19] Kristen Moulton, “At Bear River Massacre site, the names of the dead ring out,” Salt Lake Tribune, January 30, 2013, http://www.sltrib.com/sltrib/news/55727028-78/bear–massacre–river–shoshone.html.csp

[20] Stephen Dark, “Last Stand: Goshutes battle to save their sacred water,” Salt Lake City Weekly, May 9, 2012, http://www.cityweekly.net/utah/article-35-15894-last–stand.html?current_page=all

[21] Sylvester L. Lahren, Jr. Ph.D., “A Shoshone/Goshute Traditional Cultural Property and Cultural Landscape, Spring Valley, Nevada. Confidential and Proprietary Report for the Goshute Tribal Council,” Confederated Tribes of the Goshute Reservation, August 9, 2010.

[22] Christopher Smart, “Snake Valley water could land in U.S. Supreme Court,” The Salt Lake Tribune, August 7, 2012, http://www.sltrib.com/sltrib/politics/54642624-90/snake–valley–nevada–rights.html.csp

“Nevada Groundwater Conservation: The Problem,” Center for Biological Diversity, accessed December 26, 2012, http://www.biologicaldiversity.org/programs/public_lands/deserts/nevada/groundwater.html

Rob Mrowka, “Groups join together to confront water rights issue,” Desert Report, Center for Biological Diversity/Great Basin Water Network, June, 2011, accessed December 26, 2012, http://www.biologicaldiversity.org/programs/public_lands/deserts/nevada/pdfs/DR_Summer2011_Mrowka.pdf

George Knapp and Matt Adams, “I-Team: Court Ruling Emboldens Water Grab Opponents,” October 31, 2011,

[23] “Water pipeline hits opposition even in thirsty Vegas,” Salt Lake Tribune, August 16, 2011, http://www.sltrib.com/sltrib/news/52398491-78/vegas–las–nevada–utah.html.csp

[24] Christopher Smart, Judy Fahys and Brian Maffly, “Herbert rejects Snake Valley water pact with Nevada,” Salt Lake Tribune, April 3, 2013, http://www.sltrib.com/sltrib/news/56090274-78/valley–agreement–snake–utah.html.csp

[25] Brian Maffly, “Rejecting Nevada water deal hurts Utah, critics say,” Salt Lake Tribune, May 25, 2013,

[26] “Lake Powell Pipeline,” Citizens for Dixie’s Future, accessed May 27, 2013, http://citizensfordixie.org/lake–powell–pipeline/