by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Mar 27, 2019 | Strategy & Analysis

Featured image: Vemork hydroelectric plant, Norway

by Max Wilbert / Deep Green Resistance

“The tough gangster type of detective fiction was of little use [in underground operations], and, in fact, likely to be a danger. Help and support to the Norwegian resistance could only be provided by [people] of character, who were prepared to adapt themselves and their views—even their orders at times—to other people and other considerations, once they saw that change was necessary. Common sense and adaptability are the two main virtues required in anyone who is to work underground, assuming a deep and broad sense of loyalty, which is the basic essential.” —Colonel John S. Wilson, leader of the Norwegian Section of the Special Operations Executive in British Exile during WWII

Thomas Gallagher’s 1975 book “Assault in Norway: Sabotaging the Nazi Nuclear Program” details a Norwegian-British covert operation carried out over the winter of 1942-43. I recommend this book for revolutionaries and serious activists, as it contains many details of how serious clandestine operations should be carried out, how to utilize intelligence and scouting, secure communications, subterfuge, proper use of terrain and other tactical advantages, and more.

The story revolves around the nuclear arms race. By 1942, U.S. and British nuclear physicists had discovered that creating an atomic bomb was a scientific possibility. This frightened them to no end, since they knew well that Germany had the most advanced nuclear research program on the planet.

Assuming that Germany had at least a 2-year research advantage, they began to look for vulnerabilities in the Nazi research program that could slow their progress toward a bomb.

A key element in this early nuclear research was “heavy water”—an isotope of standard water that can only be isolated and concentrated through the use of vast amounts of electricity. At the time, the only plant in Europe capable of creating significant amounts of heavy water was at the Norsk Hydro plant at Vemork, in Nazi-occupied Norway.

Hoping to stop the flow of heavy water in Germany, British and Norwegian-exile military intelligence hatched a plan to sabotage the Vemork plant and destroy the stockpiles of heavy water held there.

Vemork was situated in a natural fortress, located in a steep mountain valley perched on a ledge on a nearly sheer cliffside. Aerial bombing would almost certainly fail, so the plan they devised was to be carried out on foot.

In October 1942, four Norwegians tasked with reconnaissance and preparation parachuted onto the Hardanger Plateau, at the time 3500-square miles of wild, virtually inhabited land. They survived there for five frigid months, eating reindeer moss and the reindeer themselves, scouting the Vemork site, detailing the habits of guards and workers, and assessing approaches to the plant. Aided by a sympathetic local population, including workers at the plant, they gathered detailed intelligence on the location.

In February, six more men parachuted into the region. They connected with the original team and created a detailed sabotage plan, which they then carried out. I won’t share any more details here, as the harrowing story is worth reading in full.

Unlike many other World War II narratives, this is not a run-and-gun firefight story. It is a story of minute planning, survival and travel in a harsh environment, and precision action carried out using terrain advantages and intelligence-driven decision making.

As such, it is an ideal story for those of us engaged in asymmetric struggle to study.

Max Wilbert is a third-generation organizer who grew up in Seattle’s post-WTO anti-globalization and undoing racism movement, and works with Deep Green Resistance. He is the author of two books.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Mar 7, 2019 | White Supremacy

by Max Wilbert / Counterpunch

In his book Capitalism and Slavery, Trinidadian historian Dr. Eric Williams writes that “Slavery was not born of racism: rather, racism was the consequence of slavery.”

Williams, like many others, argues that racism was created by the powerful to justify subjugation that was already in progress. In other words, the desire to exploit came first, and racism was developed as a moral system to justify the exploitation.

This has profound implications for how we approach the topic of dismantling racism and white supremacy.

Most people today know that race and racism are not “natural.” Scientifically, there is no such thing as “race.” Of course, there are differences in skin color between different groups of people. And it is possible to lump people into rough geographic groups based on their heritage and specific physical characteristics. But the concept of race is a vast oversimplification of this natural variation.

The fact that race is an artificial construct becomes clear when you study how “mixed-race” people are perceived in society today. In general, society considers a person who is half white and half black to be… black. In these sorts of examples, race is exposed as a set of stereotypes, a shorthand that people use to categorize people into a set of expectations and social boxes.

This, of course, isn’t to say that race isn’t “socially real.” In our culture, race is a material reality. But it’s a fuzzy one, a constructed one. This becomes obvious when we study the history of race and racism, and when we examine how these concepts have evolved over time to better serve the (fractured, not unitary) ruling class.

For another example of how race functions as a system of power, we can look at how various ethnic groups have shifted in and out of the privileged class “white” over time. The book How the Irish Became White traces this phenomenon, examining how mostly dirt-poor Irish immigrants to the US were treated as a sub-human race of lesser innate worth and intelligence, and how over time, the Irish became accepted as “white” in return for their largely collective agreement to oppress blacks and other non-white peoples.

Racism functions today, as it has historically, as a system used to justify the oppression and exploitation of billions of people of color worldwide. In his pioneering book The Nazi Doctors, Dr. Robert Jay Lifton writes that people cannot continue to commit atrocities without having them fully rationalized. He calls these justifications a “claim to virtue.” For the Nazis Lifton studied in particular, the mass murder of Jews was justifiable to create Lebensraum (“living space”) for the Aryan race.

Similarly, racism allows white supremacists (both overt and covert) to claim virtue as they brutally exploit people. The ideology of slavery and colonization relies on the idea that Black and indigenous peoples are “sub-human” and need to be “civilized.” Early white historians of slavery such as Ulrich B. Phillips wrote that slavery lifted the African people from barbarism, protected them, and benefited them.

From claiming that non-white people were separate species, to racist IQ tests, to Trump claiming Central American refugees are disease-ridden rapists, these campaigns of virtue have continued for hundreds of years.

If racism was born primarily out of political necessity to justify exploitation—this changes the way that we approach dismantling racism. Instead of a cultural attitude or idea that can educated away, this understanding has us see racism as fundamentally linked to a material system of exploitation. In fact, we could say that racism IS material exploitation.

Today, this system of racist exploitation takes many forms.

It takes the form of a massive private prison system that profits from the enslavement of the largest prison population in the world, a population that is disproportionately black, Latino, and indigenous. There are more black people in prison today than were in prison at the height of slavery, and these people are forced to work for free or slave wages (often $1 per hour or less) for private profit.

It takes the form of a complicit educational system that dehumanizes black and brown children from birth while railroading them on the school-to-prison pipeline.

It takes the form of an economic system that uses redlining, payday loans, and other predatory financial practices to steal from the poor black and brown people of this country, leaving people destitute and facing homelessness, disease, cold, and hunger.

It takes the form of the war on drugs, which originated in the crack cocaine epidemic in black inner cities started in the 1980’s. In 1996, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Gary Webb, who worked for The Mercury News newspaper in San Rose, launched his “Dark Alliance” series of articles with this: “For the better part of a decade, a San Francisco Bay Area drug ring sold tons of cocaine to the Crips and Bloods street gangs of Los Angeles and funneled millions in drug profits to a Latin American guerrilla army run by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency.” This drug ring “opened the first pipeline between Colombia’s cocaine cartels and the black neighborhoods of Los Angeles” and, as a result, “helped spark a crack explosion in urban America.” This helped fuel the drug war, a key pillar of US internal counterinsurgency strategy, and led to massively profitable asset forfeiture programs, internal security business, and a booming private prison system. After this report, Webb was attacked by the three largest newspapers in the country, run out of his job, went bankrupt, and eventually ‘killed himself’ with two self-inflicted gunshots.

It takes the form of a fossil fuel and real-estate boom making billions of dollars while bulldozing through indigenous lands and building on top of burial grounds and sacred sites, and more broadly of environmental racism through which toxic and radioactive industries, waste, and facilities are offloaded onto communities of color.

It takes the form of a US and western foreign policy that backs right-wing coups and wars in places like Honduras, Afghanistan, Iraq, Yemen, Libya, The Philippines, and elsewhere for the sake of geopolitical and financial power, then demonizes refugees fleeing from this violence who can then be exploited for low wage jobs, prostitution, and practical slavery while they live in fear.

It takes the form of global trade agreements like NAFTA which impoverish millions of poor people of color globally and make it even more profitable and easy for corporations to make billions on the exploitation of cheap labor in sweatshops, maquiladoras, and electronics factories.

These are just a few examples.

***

Feminist author Marilyn Frye described oppression as being similar to a birdcage. Examine any one bar of the cage, and it appears to be no obstacle. After all, a bird can simply fly around it. Only when you consider the inter-relationship between the different bars do you get a sense of how the cage works to immobilize and confine the occupant.

Racism works in a similar way. Education, prisons, mass media, banks, war, politicians, non-profits, developers, drugs and alcohol, entertainment, and various other institutions and forces combined form a cage that is locked tightly around people of color.

This brutal system is responsible for the deaths of millions and an obscene amount of suffering.

The routine public executions of black and brown people conducted by the police are a terrorist tactic no different from the lashing of slaves. For both white and black and brown community, these displays clearly teach and enforce the power hierarchy. Body cameras have only made these dominance displays more public, and thus more effective.

***

When we understand how racism functions, we are better able to plan our attack against it.

If racism is a system of power set up to benefit the ruling class, education (the favorite method of liberals) can never be enough. Fundamentally, racism is not based on ignorance; it’s based on power and exploitation. That doesn’t mean education is worthless, but it does mean that ending racism is primarily a power struggle, not a matter of changing minds. Education is necessary, but not sufficient.

A radical approach to dismantling racism requires dismantling the material institutions that uphold and benefit from white supremacy.

To call this understanding of racism “economic” is an oversimplification. Systems of oppression function mostly to steal from the poor and reward the rich, but they are not purely rational. And this approach doesn’t mean subordinating racism to class struggle. Racism is not “less important” than class struggle, and arguments that it is (mainly from white people) have rightly drawn a lot of criticism from people of color activists.

That said, radical people of color have long understood that racism is one key pillar in a system of domination and exploitation that is much broader than racism alone. Fred Hampton’s Rainbow Coalition in Chicago is a key example, bringing together black, Puerto Rican, working class white, and socialist groups, not to subordinate their struggles to a larger goal, but to coordinate their fight against the ruling class as a united front.

***

Modern white supremacy has its foundation in ideas and in culture, but it expresses itself primarily through economic power, military power, police power, media power, and so on. These are all concrete institutions that can be destroyed. I believe that too little attention is paid to vulnerabilities in the global system of white supremacist empire.

This line of thought has not been explored much by radical leftists. Revolutionary traditions have been dominated by strains of Marxism, which focus on seizing state and corporate power and institutions, not on destroying or incapacitating them.

The revolutionary strategy “Decisive Ecological Warfare” (DEW) was originally described in 2011 as an emergency measure to address the environmental crisis. However, this strategy has implications for the fight against racism as well.

The DEW strategy calls for underground guerilla cells to target key nodes in global industrial infrastructure, such as energy systems, communications, finance, trade hubs, and so on. The goal is to cause “cascading systems failure” in the global capitalist economy while minimizing civilian casualties. If successful, this strategy could fatally damage capitalism and deal a major blow to the power of white supremacy.

The first objection most people in the global north have to this strategy is reflexive: we are dependent on capitalist systems for survival. This is the depraved genius of any abusive system; white supremacist capitalism systematically exterminates alternative ways to live, and thus makes us dependent upon the same system that exploits and murders us. It’s the exact same method used by abusive men to control and coerce their wives and girlfriends.

Capitalism does not care about us. The state does not care about us. In the face of global ecological collapse, these institutions will leave us to die while the rich retreat to gated communities with armed guards. They make us dependent on their system then profit from our misery and death. We need to build alternative grassroots institutions, food systems, self-defense groups, and communities outside of capitalism. This is essential whether we pursue DEW or not. But without DEW and other forms of offensive struggle, the corporate-state will destroy alternative communities whenever possible. Defending these spaces will be a losing battle without larger changes.

No war is won through defense alone.

No one strategy is a magic bullet. But Decisive Ecological Warfare offers revolutionaries a weapon that could strike decisive blows against white supremacist, capitalist power structures, and create opportunities for new types of communities based on justice to exist and flourish.

Max Wilbert is a writer, activist, and organizer with the group Deep Green Resistance. He lives on occupied Kalapuya Territory in Oregon.

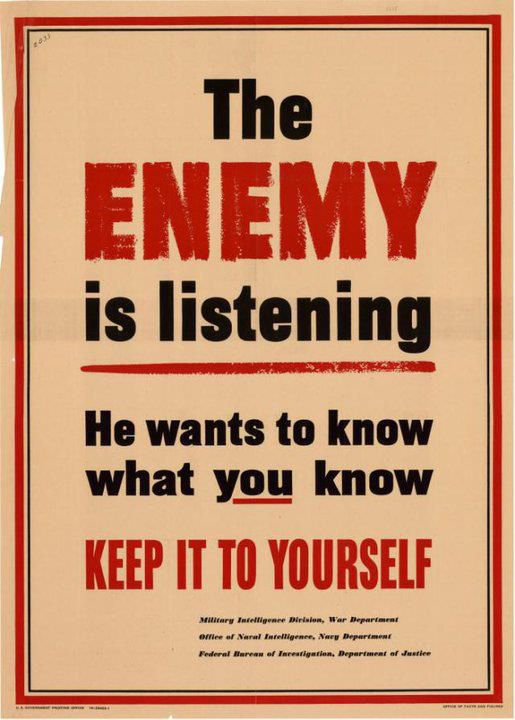

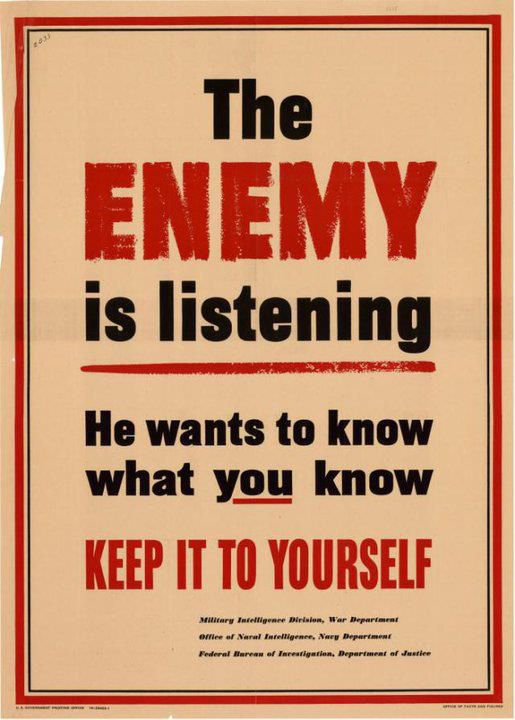

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Mar 3, 2019 | Movement Building & Support

by Max Wilbert / Deep Green Resistance

Those in power do not hesitate to assault, imprison, torture, and sometimes murder those who fight capitalism, patriarchy, racism, the murder of the planet, and other elements of global empire.

In order to do this, they need information. State agencies, private military corporations, investigators, and far-right reactionaries want to gather as much information on revolutionaries as possible. The information they want includes where you live, who you associate with, where you go, where you work, and more.

Protection of information is therefore critical to survival and effectiveness of resistance movements. This becomes even more important when you’re engaged in high-risk revolutionary work and direct action.

Militaries around the world use a procedure called operational security (OPSEC) to protect important information. While I am opposed to all imperialist militaries, we can and should learn from our adversaries. Therefore, I am writing this article to help keep you safe and make you more effective.

What is OPSEC?

OPSEC is defined as “the protection of information that, if available to an adversary, would be detrimental to you/your mission.” Implementing OPSEC is essential for revolutionaries and activists, and can also be valuable for many other people, including:

- Women facing stalking, sexual violence, or abuse

- Immigrants seeking to avoid persecution, detention, and deportation

- People of color threatened by racist persecution and violence

- Prominent individuals facing doxing and harassment

The 5-step OPSEC process

In Army Regulation 530-1, the US military defines a 5-step process for operational security. This procedure should be studied and implemented by all activists and revolutionaries. In fact, we should practice OPSEC at all times, in all situations. Rather than fostering paranoia, this allows us to ensure maximum safety based on a realistic assessment of threats and vulnerabilities.

Step 1: Identify the information you want to protect

The first step in the OPSEC procedure is the simplest. Determine which information you want to protect. This may include:

- Plans

- Procedures

- Relationships

- Locations

- Timing

- Communications

- Purchases

Step 2: Analysis of threats

The second step is to develop a “threat model.” In other words, determine who you need to protect this information from, and what their capabilities are. Then assess how these capabilities may impact you in the particular situation at hand.

In this stage, you should also ask yourself “what information does the adversary already know? Is it too late to protect sensitive information?” If so, determine what course of action you need to take to mitigate the issue, plan for ramifications, and prevent it from happening again.

You can learn about the capabilities of state agencies and private intelligence companies from the following sources:

Step 3: Analysis of vulnerabilities

Now that you know what you need to protect, and what the threats are, you can identify specific vulnerabilities.

For example, if you are trying to protect location information from state agencies and corporations, carrying a cell phone with you is a specific vulnerability, because a cell phone triangulates your location and logs this information with the service provider each time it connects to cell towers. If this phone is linked to you, your location will be regularly recorded anytime your cell phone is connected to cell towers. This process can be repeated to identify multiple vulnerabilities.

Once you have determined these vulnerabilities, you can begin to draft OPSEC measures to mitigate or eliminate the vulnerability. There are three types of measures you can take.

- Action controls eliminate the potential vulnerability itself. EXAMPLE: get rid of your cell phone completely.

- Countermeasures attack the enemy data collection using camouflage, concealment, jamming, or physical destruction. EXAMPLE: use a faraday bag to store your phone, and only remove it from the bag in specific non-vulnerable locations that you are not concerned about having recorded. NB: This method may not eliminate all dangerous data tracking, as smartphones are capable of tracking and recording location and movement data using their built-in compass and accelerometer, even when they have no access to GPS, cellular networks, or other radio frequencies.

- Counter analysis confuses the enemy via deception and cover. EXAMPLE: give your phone to a trusted friend who is moving to a different location so that your tracked location appears different than your real location during a given period.

Step 4: Assessment of risk and countermeasures

Step four is to conduct an in-depth analysis of which OPSEC countermeasures are appropriate to protect which pieces of information. Decide on the cost-benefit ratio of each countermeasure. You want to ensure that your security measures are strong and adequate, but ideally, they should not hamper the mission itself. Determine which factors are most important and make a judgement call about your course of action.

Step 5: Apply your OPSEC countermeasures

The final step is to put the plan into action. Implement your chosen action controls, countermeasures, or counter analysis methods.

Once the operation is complete, or on an ongoing basis, you should also reassess effectiveness. Conduct research, analyze any mistakes you have made, and plan for the ramifications of these mistakes. Then improve your techniques and repeat the process.

Creating a “security culture”

Operational security does not make sense for everyone. It is designed to protect groups of people engaged in high-risk activities. Therefore, OPSEC is not a hobby or something to be practiced occasionally. The OPSEC procedure should be habitual and regular, because it only takes a short period of inattention to accidentally disclose information that can have dangerous consequences.

The lessons in this article need to be combined with general activist “security culture.” and basic forensic countermeasures (a topic I will cover in another article) to protect us from threats.

It is important that we begin to shift our culture of activism towards revolutionary confrontation. This requires a serious shift in attitude. We need to look at ourselves as warriors in a life-and-death war for the future of the planet. OPSEC provides us with a procedure for increasing our safety and reminds us to treat this struggle as seriously as it really is.

—

Max Wilbert is a third-generation organizer who grew up in Seattle’s post-WTO anti-globalization and undoing racism movement, and works with Deep Green Resistance. He is the author of two books.

by DGR News Service | Feb 18, 2019 | The Problem: Civilization

Part 2

This is an excerpt from the book Deep Green Resistance – Strategy to save the planet

by Lierre Keith

Most people, or at least most people with a beating heart, have already done the math, added up the arrogance, sadism, stupidity, and denial, and reached the bottom line: a dead planet. Some of us carry that final sum like the weight of a corpse. For others, that conclusion turns the heart to a smoldering coal. But despair and rage have been declared unevolved and unclean, beneath the “spiritual warriors” who insist they will save the planet by “healing” themselves. How this activity will stop the release of carbon and the felling of forests is never actually explained. The answer lies vaguely between being the change we wish to see and a 100th monkey of hope, a monkey that is frankly more Christmas pony than actual possibility.

Given that the culture of America is founded on individualism and awash in privilege, it’s no surprise that narcissism is the end result. The social upheavals of the ’60s split along fault lines of responsibility and hedonism, of justice and selfishness, of sacrifice and entitlement. What we are left with is an alternative culture, a small, separate world of the converted, content to coexist alongside a virulent mainstream. Here, one can find workshops on “scarcity consciousness,” as if poverty were a state of mind and not a structural support of capitalism. This culture leaves us ill-prepared to face the crisis of planetary biocide that greets us daily with its own grim dawn. The facts are not conducive to an open-hearted state of wonder. To confront the truth as adults, not as faux children, requires an adult fortitude and courage, grounded in our adult responsibilities to the world. It requires those things because the situation is horrific and living with that knowledge will hurt. Meanwhile, I have been to workshops where global warming was treated as an opportunity for personal growth, and no one there but me saw a problem with that.

The word sustainable—the “Praise, Jesus!” of the eco-earnest—serves as an example of the worst tendencies of the alternative culture. It’s a word that perfectly meshes corporate marketers’ carefully calculated upswell of green sentiment with the relentless denial of the privileged. It’s a word I can barely stand to use because it has been so exsanguinated by cheerleaders for a technotopic, consumer kingdom come. To doubt the vague promise now firmly embedded in the word—that we can have our cars, our corporations, our consumption, and our planet, too—is both treason and heresy to the emotional well-being of most progressives. But here’s the question: Do we want to feel better or do we want to be effective? Are we sentimentalists or are we warriors?

For “sustainable” to mean anything, we must embrace and then defend the bare truth: the planet is primary. The life-producing work of a million species is literally the earth, air, and water that we depend on. No human activity—not the vacuous, not the sublime—is worth more than that matrix. Neither, in the end, is any human life. If we use the word “sustainable” and don’t mean that, then we are liars of the worst sort: the kind who let atrocities happen while we stand by and do nothing.

Even if it were possible to reach narcissists, we are out of time. Admitting we have to move forward without them, we step away from the cloying childishness and optimistic white-lite denial of so much of the left and embrace our adult knowledge. With all apologies to Yeats, in knowledge begins responsibilities. It’s to you grown-ups, the grieving and the raging, that we address this book.

The vast majority of the population will do nothing unless they are led, cajoled, or forced. If the structural determinants are in place for people to live their lives without doing damage—for example, if they’re hunter-gatherers with respected elders—then that’s what happens. If, on the other hand, the environment has been arranged for cars, industrial schooling is mandatory, resisting war taxes will land you in jail, food is only available through giant corporate enterprises selling giant corporate degradation, and misogynist pornography is only a click away 24/7—well, welcome to the nightmare. This culture is basically conducting a massive Milgram experiment on us, only the electric shocks aren’t fake—they’re killing off the planet, species by species.

But wherever there is oppression there is resistance. That is true everywhere, and has been forever. The resistance is built body by body from a tiny few, from the stalwart, the brave, the determined, who are willing to stand against both power and social censure. It is our prediction that there will be no mass movement, not in time to save this planet, our home. That tiny percent—Margaret Mead’s small group of thoughtful, committed citizens—has been able to shift both the cultural consciousness and the power structures toward justice in times past. It is valid to long for a mass movement, however, no matter how much we rationally know that we’re wishing on a star. Theoretically, the human race as a whole could face our situation and make some decisions—tough decisions, but fair ones, that include an equitable distribution of both resources and justice, that respect and embrace the limits of our planet. But none of the institutions that govern our lives, from the economic to the religious, are on the side of justice or sustainability. Theoretically, these institutions could be forced to change. The history of every human rights struggle bears witness to how courage and sacrifice can dismantle power and injustice. But again, it takes time. If we had a thousand years, even a hundred years, building a movement to transform the dominant institutions around the globe would be the task before us. But the Western black rhinoceros is out of time. So is the golden toad, the pygmy rabbit. No one is going to save this planet except us.

So what are our options? The usual approach of long, slow institutional change has been foreclosed, and many of us know that. The default setting for environmentalists has become personal lifestyle “choices.” This should have been predictable as it merges perfectly into the demands of capitalism, especially the condensed corporate version mediating our every impulse into their profit. But we can’t consume our way out of environmental collapse; consumption is the problem. We might be forgiven for initially accepting an exhortation to “simple living” as a solution to that consumption, especially as the major environmental organizations and the media have declared lifestyle change our First Commandment. Have you accepted compact fluorescents as your personal savior? But lifestyle change is not a solution as it doesn’t address the root of the problem.

We have believed such ridiculous solutions because our perception has been blunted by some portion of denial and despair. And those are legitimate reactions. I’m not persuading anyone out of them. But do we want to develop a strategy to manage our emotional state or to save the planet?

And we’ve believed in these lifestyle solutions because everyone around us insists they’re workable, a collective repeating mantra of “renewables, recycling” that has dulled us into belief. Like Eichmann, no one has told us that it’s wrong.

Until now. So this is the moment when you will have to decide. Do you want to be part of a serious effort to save this planet? Not a serious effort at collective delusion, not a serious effort to feel better, not a serious effort to save you and yours, but an actual strategy to stop the destruction of everything worth loving. If your answer feels as imperative as instinct, read on.

Image: copyright free via Unsplash