by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 27, 2016 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Strategy & Analysis

By Zoe Blunt / WildCoast.ca

“I’m in love. With salmon, with trees outside my window, with baby lampreys living in sandy streambottoms, with slender salamanders crawling through the duff. And if you love, you act to defend your beloved.” — Derrick Jensen

Pacific Coast people have always defended the places we love. Most of British Columbia is unceded indigenous land; native peoples have never abandoned, sold, or traded their land away. Many fought fiercely against the power of the British Empire. Cannonballs are sometimes still found embedded in centuries-old trees along the shore – leftovers from the gunboats that tried to suppress indigenous uprisings in the late 1800s.

Nuu-chah-nulth war canoes (Edward Curtis, BC Historical Society)

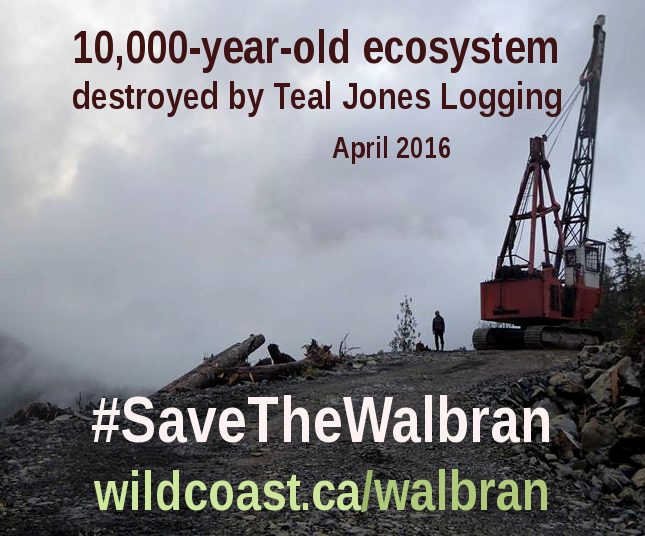

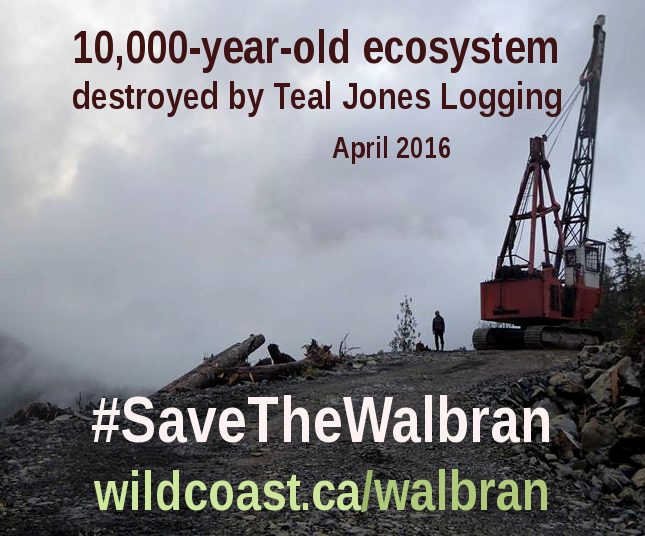

A century later, descendants of the settlers have joined forces to battle corporate raiders. In the 1980s and 1990s, a groundswell of eco-organizing brought thousands of people together to stop clearcut logging in the cathedral forests of Vancouver Island’s Pacific coast, where timber companies were busy converting ten-thousand-year-old ecosystems into barren stumpfields and pulp for paper.

During those years, police arrested hundreds in Clayoquot Sound and the Walbran Valley at mass civil disobedience protests. Young and old alike sat in the middle of the logging roads and linked arms. The resistance went far beyond the peaceful and symbolic: unknown individuals spiked thousands of trees to make the timber dangerous to sawmills. Shadowy figures burned logging bridges and vandalized equipment. The skirmishes went on for over a decade.

Clayoquot Sound, 1993

We won a few battles. Several coastal valleys are protected as parks. But many of them have been logged. And now the logging companies are coming back for the valleys that remain unprotected.

One of the worst corporate offenders is Teal Jones, the company currently bulldozing the majestic Walbran Valley, two hours west of Victoria, BC. They are laying waste to a vibrant rainforest for short-term profit, without the consent of the Pacheedaht First Nation, the Qwa-ba-diwa people, or anyone else outside of government and industry. Teal Jones does not even own the land; it was taken from indigenous people in the name of the BC government sixty years ago.

Pacheedaht territory, Vancouver Island BC

This year, the elected leadership of the Pacheedaht First Nation threw its support behind building a longhouse in the contested valley, on the land that has sustained them for countless generations. At the same time, locals are pushing back against the logging by occupying roads and logging sites. This in spite of the company’s court order telling police to arrest anyone who blocks their work. Forest defenders are regrouping, but the destruction continues.

Women for the Walbran and Forest Action Network are ramping up to break the deadlock. We’re hosting direct action trainings to share skills and develop strategies for defending ecosystems. The agenda includes tactics like non-violent civil disobedience, occupying tree-tops, and backcountry stealth. We’ll have info on legal rights, indigenous solidarity, and more.

Tree-sit occupation, Langford BC. (Photo: Ingmar Lee)

Our adversary, Teal Jones, is a relatively small company. Its owners are relying on the police to protect their “right” to strip public forests on Pacheedaht traditional territory. Profit margins are slim, and lawyers are expensive. The forest defenders are poor, but we have community support and a wide array of strategies for beating Teal Jones at its own game. Every tool in the box: we can launch a mass civil disobedience campaign, carry out hit-and-run raids on costly machines, coordinate a knockout legal strategy, or deliver the tried-and-true “death by a thousand cuts” with a combination of tactics.

However it plays out, Teal Jones is on borrowed time in the Walbran. But that’s cold comfort when the machines are mowing down thousand-year-old forests like grass.

Photo: Walbran Central

The forest defenders do have certain advantages. On the practical side, we’re investing in the gear and training that will provide the leverage to win. We have a legal defense fund that’s both a war chest for litigation and a safety net for those who risk their freedom on the front lines. But our best defense is the thousands of people who love this land like life itself. Many live nearby and visit every chance they get, others came once and fell in love, and untold numbers have yet to see the Walbran’s wildlife firsthand, but they hold it in their hearts.

Photo: Walbran Central

Those who love the land are a community. We are the organizers, sponsors, and volunteers who drive this movement forward. Everyone who shares these values can be a part of it; no contribution is too small. We’re going all-out to defend the forests, rivers, bears, cougars, otters, and eagles of the Walbran Valley. They sustain us and we give back by fighting to protect them.

Walbran River, the heart of the Walbran Valley, spring 2016. (Photo: Walbran Central)

Remember: Forest Defenders Are Heroes!

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 9, 2016 | Culture of Resistance, The Solution: Resistance

By Zoe Blunt / Deep Green Resistance

Featured Image via the Speak Truth the Power Project.

The more we challenge the status quo, the more those with power attack us. Fortunately, social change is not a popularity contest.

Activism is a path to healing from trauma. It’s taking back our power to protect ourselves and our future.

From a spoken-word presentation in Victoria BC, 2009

Thank you for the opportunity to launch my speaking career. Some of you may know me as a writer and an advocate for social and environmental justice. Others may know me as a cat-sitter, odd-jobber, and temp slave. (Laughter)

I knew when I started out as an activist that I would never be a millionaire and I was right. But I have a certain freedom and flexibility that your average millionaire might envy.

The market demand for social justice advocates is huge right now. It’s a growth industry. And the job security is fantastic – there is no shortage of urgent issues demanding our attention. Experience is not necessary, people come to activism at every age and stage in their lives. It’s that easy!

OK, it’s not actually that easy. (Laughter) But it is a fascinating time to be a “radical.”

There is a great tradition of courage and action here on Vancouver Island. There is potential for even greater future action, so we are doing everything we can to nurture that potential. Building community, linking up networks, teaching, learning, coming together, healing – this is all part of the movement.

For most of my adult life, I suffered from social phobia. I was afraid of authority, filled with self-doubt, paralyzed by anxiety. Getting interviewed live on national TV doesn’t make that go away. But hiding under the covers doesn’t cure it either. So my insecurities and I just have to get out there and do our best.

What compels me is the knowledge that we’re rewriting the script – the one that says, “You don’t make a difference. It is what it is, you can’t fight city hall, the big guys always win.” We can remember that we are not powerless. And when we choose to stand up, it is a huge adrenaline rush – bigger than national TV or swinging from a tree top. That’s the reward – that flood of excitement that comes from taking back our power and using it effectively, for the collective good.

It helps to get love letters from friends and strangers who want to thank me for standing up for what’s important, and who get inspired to take action themselves.

But it’s not all warm fuzzies and celebratory toasts. We face backlash and punishment and threats to our lives and safety.

I led a workshop for new activists this year, and I asked them, “Who are your heroes?”

They named a dozen. Gandhi. Martin Luther King. Tommy Douglas. Rosa Parks. These folks led amazing, heroic movements, but our discussion focused on the ferocious backlash they faced. British media reports on Gandhi when he was challenging the monarchy had the same tone as white Southerners responding to Rosa Parks refusing to give up her seat on the bus. It was vicious. “Uppity and no-good” were some of the polite terms. They were targeted with hate speech and death threats. We hear the same now about whistleblowers. And feminists and environmentalists. It can be terrifying.

The more we challenge the status quo, the more the entrenched powers attack us. The more effective we are, the more they attack us. As Gandhi said: “First the ignore you, then they ridicule you, then they fight you, then you win.”

The fight for justice and liberation won’t be won by popularity contests.

Every campaigner finds their own way of dealing with the counter-attacks. Some laugh it off. Some pray, some cry on their friends’ shoulders. Some go on the counter-offensive, some compose songs, some write long academic papers deconstructing their opponents’ logic. The important thing is, they deal with it, and they don’t give up.

We take care of each other as a community. Because we are all so fragile. Because there is so much trauma and despair everywhere and it affects everyone. But inside that despair, in all of us, there is a solid core of love for the earth and the knowledge that we can act in self-defense. That’s where we find strength.

It’s humbling to note that the economic downturn has done more to preserve habitat and stop climate change than all of our conservation efforts of the past years combined. We take responsibility for recycling and turning down the thermostat, but who is responsible for the scale of destruction from the Tar Sands? That project is the equivalent of burning all of Vancouver Island to the ground. It negates everything we could hope to do as individuals to fight climate change.

How do we deal with that horrible reality? I couldn’t, for the first year of the campaign. I didn’t want to look at the pictures and hear the news stories about the water and air pollution and the rates of illness among the Lubicon Cree people. The scale and the horror of it were too great.

I’ve worked on toxics campaigns and I dread them. Old-growth campaigns are inspiring, because where the action is, the forest is still standing – it’s beautiful and magical and we’re defending nature’s cathedral from the bulldozers and chainsaws. The good earth is here, and the evil destructive forces are over there. It’s clearcut, so to speak. But when a toxics campaign is underway, the damage has been done. The landscape is poisoned and people have cancer and spontaneous abortions, and the birds, the fish, the animals, are dead and dying. It is a scene of despair.

If it sounds traumatizing, it is. And we are all traumatized.

Look at this landscape – concrete, pavement, bricks and mortar, toxic chemicals, but underneath, the earth is still there. We have whole ecosystems slashed and burned without so much as a by-your-leave. We’ve lost whole communities of spruce, marmots, murrelets, arbutus, sea otters, and geoducks. These are terrible losses.

And we humans suffer on every level. Is there anyone here who doesn’t know someone who’s had cancer? Who hasn’t seen the damage caused by diseases of civilization? Who here hasn’t been forced to do without for lack of money? Are there any women here who have never been sexually harassed or raped or assaulted?

(Silence)

Something fundamental has been taken from us here. How do we deal with these losses?

I consider myself fortunate because after a lifetime of abuse from my family and male partners, I participated in six months of Trauma Recovery and Empowerment at the Battered Women’s Support Centre in Vancouver.

And I got to know the stages of trauma recovery:

Acknowledge the loss, understand the loss, grieve the loss.

And the stages of grief:

Denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.

These steps are a natural and necessary response to the loss of a loved one, and also to the loss of our humanity and the places we love.

There are people living in national sacrifice zones, people who burn with determination to make change. They are angry, and they have a right to be. I am angry because I’m not dead inside, in spite of all they’ve done to me. Anger is part of the process of grief, and it’s useful. It grabs us by the heart when people are hurting the ones we love.

For me, part of the process is taking action – rejecting helplessness and taking back power. Stopping the bleeding and comforting the wounded.

I fall in love with places and I want to protect them. I fell in love with the Elaho Valley and some of the world’s biggest Douglas Firs in 1997. That forest campaign was a pitched battle, far from the urban centers, against one of the biggest logging companies on the coast at that time.

In the third year of the campaign, I walked into my favourite campsite shaded by majestic cedars. I saw the flagging tape and the clearcut boundaries laid out, and I realized it was all doomed. I could see the end result in my mind’s eye: stumps and slash piles as far as the eye could see, muddy wrecked creeks, a smoldering ruin.

I realized no one was going to come and save this place – not Greenpeace or the Sierra Club, no MP’s private member’s bill, or whatever petition or rally was being planned back in the city. It was as good as gone. All we had to do was stand aside and do nothing, and this incredible, irreplaceable forest would be just a sad memory.

But after that realization, and after the despair that followed, I had a profound sense of liberation. If it is all doomed, then anything we do to resist is positive, right? Anything that stops the logging, even for a minute, or slows it down, or costs the company money, or exposes it to public embarrassment and hurts its market share, is positive – it keeps the future alive for that one more minute, one more hour, one more day. It was a revelation.

Acceptance, for me, meant being able to act to defend the place I loved. It meant standing up to the bullies and refusing to let them take anything more from me.

In the third year of the Elaho campaign, it was just a handful of people rebuilding the blockades, defying the court orders and continuing the resistance. We didn’t quit when the police came, or when we were called “terrorists” and “enemies of BC.” We didn’t quit even after 100 loggers came and burned our camp to the ground and put three people in the hospital.

The attack was a horror show. People were in shock. But a crew was back with a new camp five days later. By then, the raid was national news. And our enemies had nothing left to throw at us. The loggers didn’t know what to do next. Short of killing us, what more could they do?

We had called their bluff.

We didn’t know about the negotiations going on behind the scenes. We didn’t realize that we had already cost the loggers more than they could hope to recoup by logging the entire rest of the valley. (They were operating on very slim profit margins.) We found out when the announcement came that the logging would stop. And it never started again. We won. Now the Elaho Valley is protected by the Squamish Nation — and by provincial legislation — as a Wild Spirit Place.

The violence of the mob showed the level of fear and desperation of the losing side. It was their weapon of last resort and it didn’t work. And they lost.

In the fourth year of the stand for SPAET – the campaign to stop the development and protect the caves, the garry oaks, and the wetlands on Skirt Mountain – we faced the same tactics. We were called “terrorists,” and in 2007, the developers sent 100 goons to rough up people at a small rally. And again, most of our comrades are still in shock. There’s only a handful of us still bashing away at the next phase of development.

We are winning. The other side has thrown everything they have at us and they have nothing left.

There are still sacred sites on SPAET. The cave is still there, buried under concrete.

Meanwhile, the developer’s little empire fell apart, either because of our boycott campaign, bad karma, or because it was operating on the slimmest of shady margins. We took the next phase of development to court. Our campaign, and the economic downturn, turned out to be enough to scare off investors and cancel the project, at least for now.

This work is difficult, painful, and traumatic. So the first step to courage is to acknowledge that pain and loss. We need to name what has been taken from us. Then we can cry, and rage, and grieve. We can name the ones who are doing the damage. We can reach down inside and find our core strength and our truth, and use it. That’s where courage comes from.

Martin Luther King said, “Justice shall roll down like waters, righteousness like a mighty stream.” But I’m impatient. I want to see that mighty stream now – what’s the hold-up? What’s holding us back, when there’s so much to do?

We’re not heroes, actually – none of us is smart enough, or tough enough, or connected enough, to take this on alone. We don’t have superpowers. We are only human, we struggle and suffer and sometimes, we win.

Some folks assume I have some vision, some over-arching game plan, some magic power that gives me an edge. Nope. Most of the time I am just flailing around on the political landscape, taking potshots when I see an opening. Sometimes it’s intuition, and it pays off. When we are right, it is amazing. When we win, it sets a precedent for the future.

In order for evil to prevail, all that’s required is for good people to do nothing. Don’t be one of those good people.

Activism is part of the healing. It’s taking action to protect ourselves and our future.

Thank you for the opportunity to tell these stories today.

(Applause)

Also read how Zoe Blunt moved from “flailing around on the political landscape” to strategic activism: Deep Green Resistance: Words as tactical weapons

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Nov 28, 2015 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Lobbying

Editor’s Note: This letter, published at Vancouver Island Community Forest Action Network, is addressed to Canadian timber company Teal Jones Group in regards to the planned logging of Walbran Valley. You can read more about this at Renewed Defense of British Columbia’s Central Walbran Ancient Forest. Featured image of freshly cut cedar tree courtesy of Walbran Central.

By Zoe Blunt / Vancouver Island Community Forest Action Network

To Teal Jones’ executives, contractors, foresters, geologists, staff, and stakeholders:

I’m writing as a director of Vancouver Island Community Forest Action Network in Port Renfrew, BC. As forest watchdogs, we share Teal Jones’ goal of achieving the best environmental stewardship possible. I’m pleased to announce we are doubling down on our commitment to that goal.

There is a growing perception that Teal Jones’ operations in the Walbran Valley – logging an ancient forest that’s part of a beloved recreation area, on public land next to a park – is illegal, or ought to be. The public has a strong interest in ensuring that Teal Jones is not breaking any laws, statutes, or regulations.

In this spirit, we are recruiting volunteers to monitor every inch of area designated for timber harvesting, including proposed clearcuts, special management zones, wildlife habitat, leave trees, slash piles, streams, log dumps, roads, helipads, culverts, and ditches. We will check signage and radio frequencies, and visually inspect logging trucks. We will make sure the stumpage and grade-setting for the area are correct. A team of eager researchers is preparing for these tasks.

Of special concern are the karst features in the area – sensitive limestone formations underground, or in this case, on the surface. This is one of our areas of expertise, and we look forward to seeing the reports from the geologist responsible for signing off on logging those cutblocks. We plan to prepare our own reports and take all appropriate steps to ensure everyone involved is aware of the provisions of the law and fully complies with the requirements of the Forest District’s order for protection of karst.

There’s more. We will continue to follow up and document the area long after the trees are felled, to monitor reforestation, slope stabilization, road decommissioning, landslides, and habitat restoration.

We welcome the opportunity to use every legal means to achieve the goal of environmental sustainability.

We are aware of the history of violence by loggers in BC, including unprovoked attacks on peaceful protesters. We are concerned about potential hotheads on the logging crew, and for that reason we will take steps to keep our volunteers safe and give them the ability to respond appropriately, including documenting any violence or threats.

We note that rather than working with the community to find a way to preserve recreation sites and wildlife habitat, Teal Jones has taken the extreme step of suing people to get them out of the way.

Speaking for Forest Action Network, we have no intention of violating the court order. We employ strictly legal means to achieve our forest stewardship goals. Since the logging is taking place in a place designated as Crown land, we have the right and the responsibility as stakeholders to monitor and bear witness to Teal Jones’ operations.

Thrush egg, Walbran Valley. Photo courtesy Ellen Atkin.

As a non-profit society, we don’t counsel anyone to commit illegal action. We don’t condone activities like sabotage, vandalizing equipment, or spiking trees, which is the practice of hammering oversized nails into trees to threaten chainsaws and mill blades. But we remember history: two thousand trees spiked in the Walbran Valley in 1992, for example. That kind of response is not what we advocate, but we recognize the potential is out of our control.

Teal Jones’ reckless pursuit of the ancient Walbran forest has brought us to this conflict in an effort to keep the peace. The company is aggressively logging up to the park boundary, disregarding community input, and failing to obtain social license for its operations in the Central Walbran. They are operating in a rapidly changing climate, using discredited practices from the last century. They have lost sight of the goal shared by millions around the world: preserving this dwindling, irreplaceable ecosystem. We will do everything in our power to sustain these living communities.

We’re looking forward to seeing you soon.

Sincerely,

Zoe Blunt

Vancouver Island Community Forest Action Network

#Walbran

Read Teal Jones’ lawsuit against environmentalists.

Read Teal Jones notice of application for an injunction.

Background info here.

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Oct 12, 2015 | Strategy & Analysis

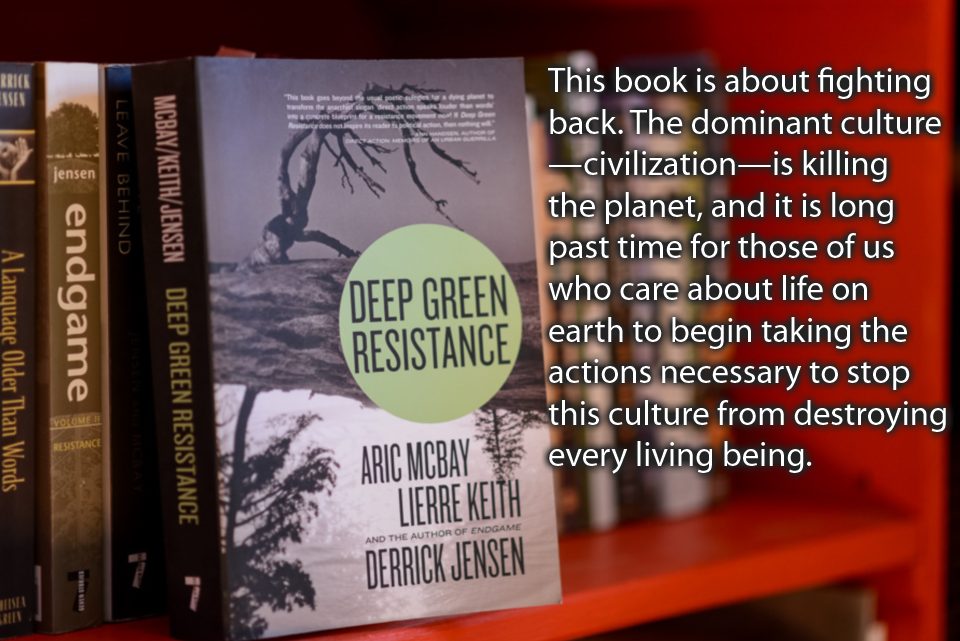

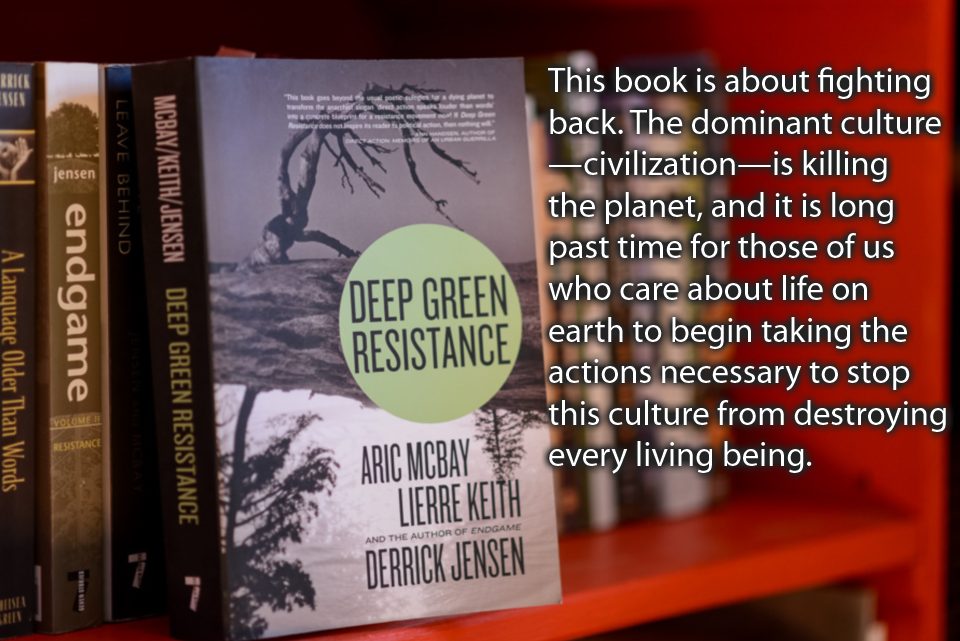

Book Review of Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet

By Zoe Blunt

I first heard about Deep Green Resistance in the middle of a grassroots fight to stop a huge vacation-home subdivision at a wilderness park on Vancouver Island. Back then, it hadn’t really occurred to me that a book on environmental strategy was needed. Now I can tell you, it’s urgent.

Deep Green Resistance (DGR) made me a better strategist. If you’re an activist, then this book is for you. But be warned: at 520 pages (plus endnotes), it’s not light reading. Quite the opposite — DGR dares environmental groups to focus on decisive tactics rather than mindless lobbying and silly stunts.

“This book is about fighting back. And this book is about winning,” author Derrick Jensen declares in the preface to this three-way collaboration with Lierre Keith and Aric McBay.

Keith, author of The Vegetarian Myth, opens the discussion with an analysis of why “traditional” environmental action is self-defeating. For those who’ve read Jensen’s Endgame, or who have experienced the frustration of born-to-lose activism, Keith’s analysis hits the nerve.

The DGR philosophy was born from failure. In a recent interview, Jensen recounts a 2007 conversation with fellow activists who asked, “Why is it that we’re doing so much activism, and the world is being killed at an increasing rate?” “This suggests our work is a failure,” Jensen concludes. “The only measure of success is the health of the planet.”

If we keep to this course, as Keith points out, the outcome is extinction: the death of species, of people, and the planet itself. Environmental “solutions” are by now predictable, and totally out of scale with the threat we’re facing. Cloth bags, eco-branded travel mugs, hemp shirts, and recycled flip-flops won’t change the world. Wishful thinking aside, they can’t, because they don’t challenge the industrial machine. It just keeps grinding out tons of waste for every human on the earth, whether they are vegan hempsters who eat local or not. So these “solutions” amount to fiddling while the world burns.

Aric McBay, organic farmer and co-author of What We Leave Behind, says Deep Green Resistance “is about making the environmental movement effective.”

“Up to this point, you know, environmental movements have relied mostly on things like petitions, lobbying, and letter-writing,” McBay says. “That hasn’t worked. That hasn’t stopped the destruction of the planet, that hasn’t stopped the destruction of our future. So the point is if we want to be effective, we have to look at what other social movements, what other resistance movements have done in the past.”

Keith notes that a given tactic can be reformist or radical, depending on how it’s used. For example, we don’t often think of legal strategies as radical, but if it’s a mass campaign with an “or else” component that empowers people and brings a decisive outcome, then it creates fundamental change.

“Don’t be afraid to be radical,” Keith advises in a recent interview. “It’s emotional, yes; this is difficult for people, but we are going to have to name these power structures and fight them. The first step is naming them, then we’ve got to figure out what their weak points are, and then organize where they are weak and we are strong.”

Powerful words. But by then I was desperate for a blueprint, a guidebook, some signposts to help break the deadlock in our campaign to save the park. Two hundred pages into DGR, we get down to brass tacks, and find out what strategic resistance looks like.

I don’t know what I was expecting, but it wasn’t a guerrilla uprising.

To be clear, Deep Green Resistance is an aboveground, nonviolent movement, but with a twist: it calls for the creation of an underground, militant movement. The gift of this book is the revelation that strategies used by successful insurgencies can be used just as successfully by nonviolent campaigns.

McBay argues convincingly that it’s the combination of peaceful and militant action that wins. He emphasizes that people must choose between aboveground tactics and underground tactics, because trying to do both at once will get you caught.

“The cases of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X exemplify how a strong militant faction can enhance the effectiveness of less militant tactics,” McBay writes. “Some presume that Malcolm X’s ‘anger’ was ineffective compared to King’s more ‘reasonable’ and conciliatory position. That couldn’t be further from the truth. It was Malxolm X who made King’s demands seem eminently reasonable, by pushing the boundaries of what the status quo would consider extreme.”

What McBay calls “decisive ecological warfare” starts with guerrilla movements and the Art of War. Guerrilla fighting is all about asymmetric warfare. One side is well-armed, well-funded, and highly disciplined, and the other side is a much smaller group of irregulars. And yet sometimes the underdog wins. It’s not by accident, and it’s not because they are all nonviolent and pure of heart, but because they use their strengths effectively. They hit where it counts. The rebels win the hearts and minds and, crucially, the hands-on support of the civilian populace. That’s what turns the tide.

McBay notes, for example, that land reclamation has proven to be a decisive strategy. He argues that “aboveground organizers [should] learn from groups like the Landless Workers’ Movement in Latin America.” This ongoing movement “has been highly successful at reclaiming ‘underutilized’ land, and political and legal frameworks in Brazil enable their strategy,” McBay adds.

Imagine two million people occupying the Tar Sands. Imagine blocking or disrupting crucial supply lines. Imagine profits nose-diving, investors bailing out, brokers panic-selling, and the whole top-heavy edifice crashing to a halt.

The Landless Workers’ Movement operates openly. Another group, the Underground Railroad, was completely secret. Members risked their lives to help slaves escape to Canada. A similar network could help future resisters flee state persecution. Those underground networks need to form now, McBay says, before the aboveground resistance gets serious, and before the inevitable crackdown comes.

DGR categorizes effective actions as either shaping, sustaining, or decisive. If a given tactic doesn’t fit one of those categories, it is not effective, McBay says. He emphasizes, however, that all good strategies must be adaptable.

To paraphrase a few nuggets of wisdom:

Stay mobile.

Get there first with the most.

Select targets carefully.

Strike and get away.

Use multiple attacks.

Don’t get pinned down.

Keep plans simple.

Seize opportunities.

Play your strengths to their weakness.

Set reachable goals.

Follow through.

Protect each other.

And never give up.

Guerrilla warfare is not a metaphor for what’s happening to the planet. The forests, the oceans, and the rivers are victims of bloody battles that start fresh every day. Here in North America, it’s low-intensity conflict. Tactics to keep the populace in line are usually limited to threats, intimidation, arrests, and so on.

But the “war in the woods” gets real here, too. I’ve been shot at by loggers. In 1999, they burned our forest camp to the ground and put three people in the hospital. In 2008, two dozen of us faced a hundred coked-up construction workers bent on beating our asses.

Elsewhere, it’s a shooting war. Canadian mining companies kill people as well as ecosystems. We are responsible for stopping them. We know what’s happening. Failing to take effective action is criminal collusion.

Wherever we are, whatever we do, they’re murdering us. They’re poisoning us. Enbridge, Deepwater Horizon, Exxon, Shell, Suncor and all their corporate buddies are poisoning the air, the water, and the land. We know it and they know it. Animals are dying and disappearing. There will be no end to the destruction as long as there is profit in it.

This work is scary as hell. That’s why we need to be really brave, really smart and really strategic.

We have strengths our opponents will never match. We’re smarter and more flexible than they are, and we’re compelled by an overwhelming motivation: to save the planet. We’re fighting for our survival and the survival of everyone we love. They just want more money, and the only power they know is force.

As Jensen says, ask a ten-year-old what we should do to stop environmental disasters that are caused in large part by the use of fossil fuels, and you’ll get a straightforward answer: stop using fossil fuels. But what if the companies don’t want to stop? Then make them stop.

Ask a North American climate-justice campaigner, and you’re likely to hear about media stunts, Facebook apps, or people stripping and smearing each other with molasses. Not to diss hard-working activists, but unless they are building strength and unity on the ground, these tactics won’t work. They’re not decisive. They’re just silly.

Of course, if the media stunts are the lead-in to mass, no-compromise, nonviolent action to shut down polluters, I’ll see you there. I’ll even do a striptease to celebrate.

© 2012 Zoe Blunt

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Sep 26, 2015 | Direct Action, Strategy & Analysis

By Zoe Blunt, Vancouver Island Community Forest Action Network

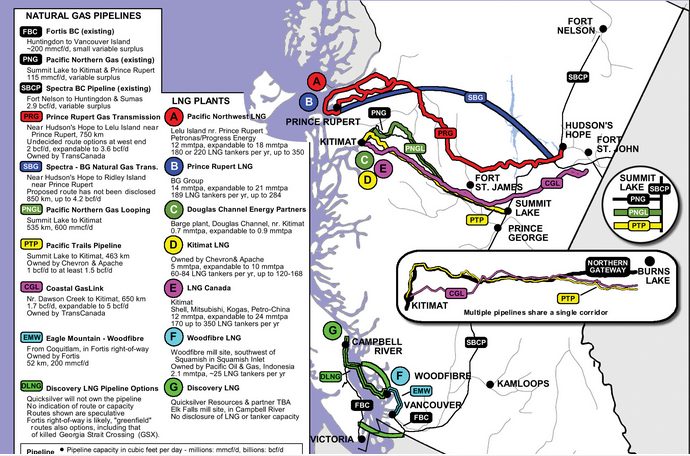

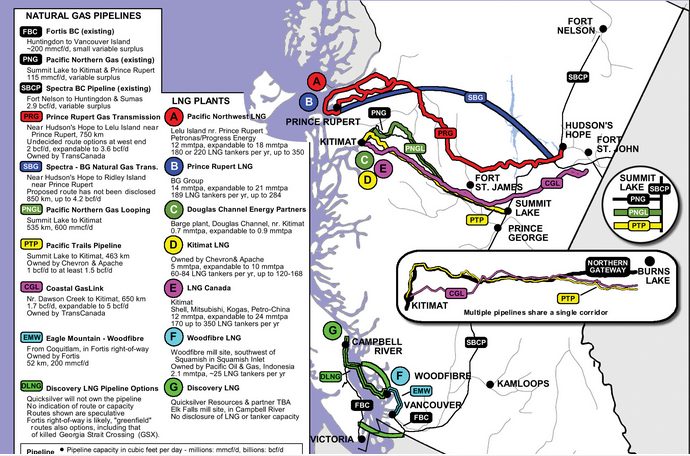

In every part of the province, industry is laying waste to huge areas of wilderness – unceded indigenous land – for mining, fracking, oil, and hydroelectric projects. This frenzy of extraction is funneling down to the port cities of the Pacific and west to China.

Prime Minister Harper has stripped away legal options to stop this pillaging by signing a new resource trade agreement with China that trumps Canadian and local laws and indigenous rights. Not even a new government has the power to change this agreement for 31 years.

For mainstream environmental groups (and my lawyers, who were in the middle of a Supreme Court challenge to the trade agreement when Harper pre-empted them), it is a total rout. We are used to losing, but not like this.

The only light on the horizon is the rise of direct resistance. BC’s long history of large-scale grassroots action (and effective covert sabotage) is the foundation of this radical resurgence.

This time it’s different. This time we can write off the Big Greens. Tzeporah Berman, once the face of the Clayoquot Sound civil disobedience protests and now head of the Tar Sands Solutions Project, is publicly proposing that enviros capitulate in the hopes of a slightly greener pipeline apocalypse.

As usual, Berman and her kind are far behind the people they pretend to lead. Public opinion is hardening against pipelines and resource extraction.

But the question hangs over us like smoke from an approaching wildfire. How to stop it? The courts are hogtied. The law has no power. The people have no agency. This government simply brushes them aside and carries on. We get it. We’ve had our faces rubbed in it.

This is activist failure. The phase of the movement when most of the public is already on side, when we have filed all the lawsuits, taken to the streets in every city, overflowed every public hearing, and uttered every threat we can muster – and the end result is they are bulldozing this province from the tarsands straight to the coast.

This is the moment when we can expect activists, especially mainstream enviros, to become demoralized and quit or capitulate. Or delude themselves. Green groups are casting about for a strategy that will allow their donors to maintain false hope in a democratic solution. Some are still trying to raise money for legal challenges that can simply be overruled by the treaty with China.

But small cadres are preparing the second phase of the resistance. Indigenous groups are reclaiming territory and blocking development at remote river crossings, on strategic access roads, and in crucial mountain passes. Urban cells are locking down to gates, vandalizing corporate offices, and organizing street takeovers.

It’s a good start. But now we have to look at how to be effective against powerful adversaries with the full weight of the law and the police on their side. How will we protect the land and each other, when push comes to shove?

The new rules don’t change our strategy to bring down the enemy: kick them in the bottom line. The resource sector will wind tighter as competition to feed China intensifies. Profits are slim enough to start with – made up in volume – and investors are jittery already.

We urge our allies to heed the lessons of history. We don’t win by giving up. Tenacity, flexibility, and diversity of tactics turn back the invaders.

Celebrate the warriors. Raise that banner now, and we’ll find out soon enough who’s with us, and who’s looking to appease our new dictators.