by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 17, 2018 | Gender

“Trans*: A Quick and Quirky Account of Gender Variability” aims to clarify, but succeeds only in highlighting the lack of clarity which dominates transgender theory.

“Let me define the terms, and I’ll win any debate,” a friend told me years ago, an insight I’ve seen confirmed many times in intellectual and political arenas.

But after reading Jack Halberstam’s new book, Trans*: A Quick and Quirky Account of Gender Variability, I would amend that observation: Debates also can be won by making sure a term is never clearly defined. The transgender movement has yet to offer coherent explanations of the concepts on which its policy proposals are based, yet support is nearly universal in left/liberal circles. Whether or not it was the author’s intention, Trans* feels like an attempt at an outline of such explanation, but I’m sorry to report that the book offers neither clarity nor coherence.

I say sorry, because I came to the book hoping to gain greater understanding of the claims of the transgender movement, which I have not found elsewhere. Halberstam — a professor in Department of English and Comparative Literature and the Institute for Research on Women, Gender, and Sexuality at Columbia University — has been writing about this subject for more than two decades and is one of the most prominent U.S. trans* intellectuals. The table of contents looked promising, but the book only deepened my belief that a radical feminist and ecological critique of the transgender movement’s ideology is necessary.

Rather than be defensive about the ambiguity of the transgender argument, Halberstam celebrates the lack of definition as a strength of the movement, an indication that trans* offers deep insights for everyone. If we shift our focus from “the housing of the body” and embrace “perpetual transition” then “we can commit to a horizon of possibility where the future is not male or female but transgender,” he writes. Instead of “male-ish” and “female-ish” bodies we can realize “the body is always under construction” and “consider whether the foundational binary of male-female may possibly have run its course.”

The very act of naming and categorizing imposes limits that constrain the imagination, according to Halberstam, hence the use of the asterisk:

“I have selected the term ‘trans*’ for this book precisely to open the term up to unfolding categories of being organized around but not confined to forms of gender variance. As we will see, the asterisk modifies the meaning of transitivity by refusing to situate transition in relation to a destination, a final form, a specific shape, or an established configuration of desire and identity. The asterisk holds off the certainty of diagnosis; it keeps at bay any sense of knowing in advance what the meaning of this or that gender variant form may be, and perhaps most importantly, it makes trans* people the authors of their own categorizations. As this book will show, trans* can be a name for expansive forms of difference, haptic [relating to the sense of touch] relations to knowing, uncertain modes of being, and the disaggregation of identity politics predicated upon the separating out of many kinds of experience that actually blend together, intersect, and mix. This terminology, trans*, stands at odds with the history of gender variance, which has been collapsed into concise definitions, sure medical pronouncements, and fierce exclusions.”

I quote at length to demonstrate that in using shorter excerpts from the book I am not cherry-picking a few particularly abstruse phrases to poke fun at a certain form of postmodern academic writing. My concern is not stylistic but about the arguments being presented. After reading that passage a couple of times, I think I can figure out what Halberstam’s trying to say. The problem is that it doesn’t say anything very helpful.

To be fair, Halberstam is correct in pointing out that the instinct to categorize all the world’s life, human and otherwise — “the mania for the godlike function of naming” — went hand in hand with colonialism, part of the overreach of a certain mix of politics and science in attempting to control the world. But like it or not, humans make sense of the world by naming, which need not go forward with claims of imperial domination or divine insight. We define the terms we use in trying to explain the world so that we can meaningfully communicate about that world; when a term means nothing specific, or means everything, or means nothing and everything at the same time, it is of no value unless one wants to obfuscate.

But, if Halberstam is to be believed, this criticism is irrelevant, because transgenderism “has never been simply a new identity among many others competing for space under the rainbow umbrella. Rather, it constitutes radically new knowledge about the experience of being in a body and can be the basis for very different ways of seeing the world.” So, if I don’t get it, the problem apparently is the limits of my imagination — I don’t grasp the radically new knowledge — not because the explanation is lacking.

After reading the book, I continue to believe that the intellectual project of the transgender movement isn’t so much wrong as it is incoherent, and the political project is not liberatory but regressive. What this book “keeps at bay” is a reasonable, honest request: What does any of this mean?

In other writing — here in 2014 and again in 2016, along with a chapter in my 2017 book The End of Patriarchy: Radical Feminism for Men — I’ve asked how we should understand transgenderism if the movement’s claim is that a male human can actually be female (or vice versa) in biological terms. If transgender signals a dissatisfaction with the culturally constructed gender norms of patriarchy — which are rigid, repressive, and reactionary — I’ve suggested it would be more effective to embrace the longstanding radical feminist critique of patriarchy.

Rather than repeat those arguments here, I want to try another approach, stating simply that I have good reason to believe I’m real, that the human species of which I am a member is real, and that the ecosphere of which we are a part is real. That is, there is a material reality to the world within which I, and all other carbon-based life forms, operate. I cannot know everything there is to know about that material world, of course, but I can trust that it is real.

The cultural/political/economic systems that shape human societies make living in the real world complex and confusing, and the ways those systems distribute wealth and power are often morally unacceptable. But to challenge that injustice, it’s necessary to understand that real world and communicate my understanding to others in clear fashion.

In left/liberal circles, especially on college campuses, “trans*” increasingly is where the action is for those concerned with social justice. It offers — for everyone, whether transgender-identified or not — the appearance of serious intellectual work and progressive politics. Endorsing the transgender project is a way to signal one is on the cutting edge, and work like Halberstam’s is embraced in these circles, where support for the transgender movement is required to be truly intersectional.

My challenge to those whose goal is liberation is simple: How does this help us understand the real world we are trying to change? How does it help us understand patriarchy, the system of institutionalized male dominance out of which so much injustice emerges?

Halberstam likely would put me in the category of “transphobic feminism” for “refusing to seriously engage” with transfeminism, but I am not transphobic (if, by that term, we mean one who is afraid of, or hateful toward, people who identify as transgender). Nor do I refuse to seriously engage other views (unless we describe a critique of another intellectual position as de facto evidence of a lack of serious engagement). I am rooted in radical feminism, one of those “versions of feminism that still insist on the centrality of female-bodied women,” according to Halberstam.

On that point, Halberstam is accurate: radical feminists argue that patriarchy is rooted in men’s claim to own or control women’s reproductive power and sexuality. Radical feminists distinguish between sex (male XY and female XX, a matter of biology) and gender (masculinity and femininity, a matter of culture and power), which means that there is no way to understand the rigid gender norms of patriarchy without recognizing the relevance of the category of “female-bodied women.” It’s hard to imagine how the binary of male-female could “run its course” given the reality of sexual reproduction.

This is where an ecological perspective, alongside and consistent with a radical feminist critique, reminds us that the world is real and we are living beings, not machines. In discussing his own top surgery (the removal of breasts), Halberstam speaks of working with the doctor:

“Together we were building something in flesh, changing the architecture of my body forever. The procedure was not about building maleness into my body; it was about editing some part of the femaleness that currently defined me. I did not think I would awake as a new self, only that some of my bodily contours would shift in ways that gave me a different bodily abode.”

We all have a right to understand ourselves as we please, and so here’s my response: My body is not a house that was constructed by an architect but rather — like all other life on the planet — is a product of evolution. I resist the suggestion I can “build” myself and recognize that a sustainable human presence on the planet is more likely if we accept that we are part of a larger living world, which has been profoundly damaged when humans treat it as our property to dominate and control.

This is the irony of Halberstam’s book and the transgender project more generally. After labeling the project of categorizing/defining as imperialist and critiquing the “mania for the godlike function of naming,” he has no problem endorsing the “godlike function” of reshaping bodies as if they were construction materials. There’s a deepening ecological sensibility in progressive politics, an awareness of what happens when humans convince ourselves that we can remake the world and ignore the biophysical limits of the ecosphere. While compassionately recognizing the reasons people who identify as transgender may seek surgery and hormone/drug treatments, we shouldn’t suppress concerns about the movement’s embrace of extreme high-tech intervention into the body, including the surgical destruction of healthy tissue and long-term health issues due to cross-sex hormones and hormone-like drugs.

I have long tried to observe what in rhetoric is sometimes called “the principle of charity,” a commitment in debate to formulating an opponent’s argument in the strongest possible version so that one’s critique is on firm footing. I have tried to do that in this review, though I concede that I’m not always sure what Halberstam is arguing, and so I may not be doing his arguments justice. But that is one of my central points: When I read this book — and many other arguments from transgender people and their allies — I routinely find myself confused, unable to understand just what is being proposed. So, again, I’ll quote at length in the hopes of being fair in my assessment, this time the book’s closing paragraph:

“Trans* bodies, in their fragmented, unfinished, broken-beyond-repair forms, remind all of us that the body is always under construction. Whether trans* bodies are policed in bathrooms or seen as killers and loners, as thwarted, lonely, violent, or tormented, they are also a site for invention, imagination, fabulous projection. Trans* bodies represent the art of becoming, the necessity of imagining, and the fleshy insistence of transitivity.”

Once again, after reading that passage a couple of times, I think I understand, sort of, the point. But, once again, I don’t see how it advances our understanding of sex and gender, of patriarchy and power. I am not alone in this assessment; people I know, including some who are sympathetic to the transgender movement’s political project, have shared similar concerns, though they often mute themselves in public to avoid being labeled transphobic.

I’m not asking of the transgender movement some grand theory to explain all the complexity of sex and gender. I just need a clear and coherent place to start. Asking questions is not transphobic, nor is observing that such clarity and coherence are lacking.

Trans*: A Quick and Quirky Account of Gender Variability was published in January 2018 by University of California Press.

Robert Jensen is a professor in the School of Journalism at the University of Texas at Austin and the author of The End of Patriarchy: Radical Feminism for Men. He can be reached atrjensen@austin.utexas.edu.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 14, 2018 | Movement Building & Support

Featured image: Army personnel assigned to Bravo Company, 121st Combat Support Hospital, based out of Camp. When one cannot go to support an action directly, how can one still support that action?

Editor’s note: This is an edited transcript of Derrick Jensen’s talk, which you can view on Deep Green Video.

by Derrick Jensen / Deep Green Resistance

Napoleon, or maybe it was Frederick the Great, famously commented that an army marches on its stomach. The quartermasters are just as important as the soldiers. In World War II battles, only about 10% of the soldiers ever fired the gun in battle. Most soldiers were clerks, truck drivers, people who delivered munitions, medics, or cooks. That is a pretty common figure: about 10%, often less. Only about 3% of the IRA ever picked up weapons.

Consider a professional basketball or baseball team. You not only have the players; you’ve got all the minor leaguers, coaches, trainers, dietitians, people who sell tickets, and groundskeepers.

A movie does not just consist of Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman. There are gaffers and best boys and stunt people and editors and caterers. There are very few accomplishments that people actually do solo.

Most of us require support in whatever we are doing, and that support work is just as important as the more glorious aspects. My friend Lierre Keith often says that an activist movement needs two things: loyalty and material support.

For example, right now there are indigenous people and some non-indigenous supporters opposing a pipeline going across their land (of course every pipeline goes across indigenous land, but we’ll leave that aside for a moment). For those who, for any number of reasons, cannot be there physically, there are a near-infinite number of things they can do. They can write letters to the editor locally, they can advocate in one way or another for them, they can send them supplies. The people on the front lines still need to eat and they are going to have shoes that fall apart; they’re going to tear a hole in their jeans or they’re going to get sick.

When we were attempting to stop timber sales, we would sometimes have to work very hard to meet a deadline. We would have until midnight to finish our appeal. We would oftentimes be working as hard as we could for hours and hours on this thing; we’d only have two hours left to go and we were really hungry, so somebody had to go get some food. That‘s just as important as the person who drives to the post office, just as important as the person who writes it. Physical, material support is very important. You need to develop support among the people in order to have a guerrilla army. That’s also true of activism. We need to raise public support for our positions.

In “Second Person Experiment” researchers had a bunch of people sitting in a room and then have a couple of people come in. One person would, for example, say something very racist. (They wouldn’t believe it, they would just say it as part of the experiment.) They found that the response of everybody else in the room was very heavily influenced by the response of the second person.

Let’s say the first person says something really racist and the second person says, “Hey yeah, it’s pretty funny, that’s great.” Everybody else in the room is much more likely to respond positively, than if the second person says, “That’s not really very cool.” That just came up in a very small way this past week.

I’m on a neighborhood watch email list where they announce when somebody gets their house burgled or something. That’s pretty handy. But another thing that the people running the list do, which kind of annoys me, is they will complain every time anybody in the neighborhood sees a mountain lion or a bear. They will say, “We need to call Fish and Game and get rid of the animals, because the mountain lion was seen carrying a gray kitty.” They’ve been doing this a lot and I kept silent, but finally I just couldn’t take it anymore and wrote a very nice note: “We need to remember that we’re in their homes, and if you have a cat and you let the cat outside, that’s the risk you’re taking. The mountain lion or the bear should not be harmed because of a risk that you took and that your cat took (never mind that cats kill birds, we’ll leave that aside).” This is a very nice note, but it had to be said.

It‘s the same on the larger scale. The line by Gandhi, “First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win” is awfully simplified, but it is really true that somebody has to go out and say something. And then somebody else has to repeat it again and again until it starts gaining a cultural currency.

In terms of the attempts to support the indigenous people opposing the pipeline, if they had 50,000 people show up, that would be great—but if that 50,000 people showed up and they had nobody show up with food, this 50,000-people-thing would last about six hours and leave a mess. You need the support in order to have a long-term campaign. That’s just as crucial as anything else.

I have a friend who is an accountant. As part of her activist work, she does accounting for various organizations. That’s something you have to do too, especially if you’re having a non-profit. You have to have somebody who can navigate that territory. I don’t care what your skills are. If you’re a good writer, they need writers; if you’re a good cook, they need good cooks; if you’re a good accountant, they need good accountants. I get so tired of being called the“violence guy” because I talk about resistance, but the truth is: We need everything. We need school teachers, we need accountants, we need cooks. We need everything.

I want to challenge everybody who’s reading this to take at least one hour every week and do some form of activism or support for somebody else’s activism. This is how I got started as an activist. When I was about 24, 25 or 26, I realized I wasn’t paying enough for gasoline. I wasn’t covering the social and economic costs. So every time I would buy gas, I was going to donate a dollar for every dollar I spent on gas to a local environmental organization. But I didn’t have any money because I was unemployed. So what I would do instead is give myself a choice: either pay a dollar for every dollar of gas, or pay myself five bucks an hour to do activism. If I spent ten bucks on gas, I would either give ten bucks to a local organization, or I would do two hours of activism.

I challenge everybody to do that: take some amount and either tithe $10 a week to some local organization, or do two hours of work for a local organization. I don’t care how busy you are, everybody can take one hour away from their life. Write a letter, go to a protest, help start assembling a package. You can do just that much to start. It’s a wonderful start.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 10, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

by Max Wilbert / Deep Green Resistance

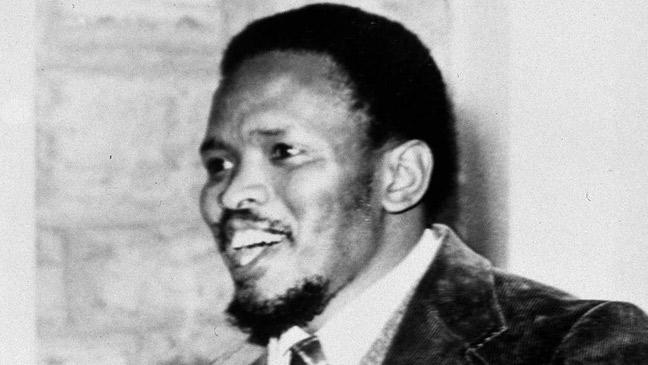

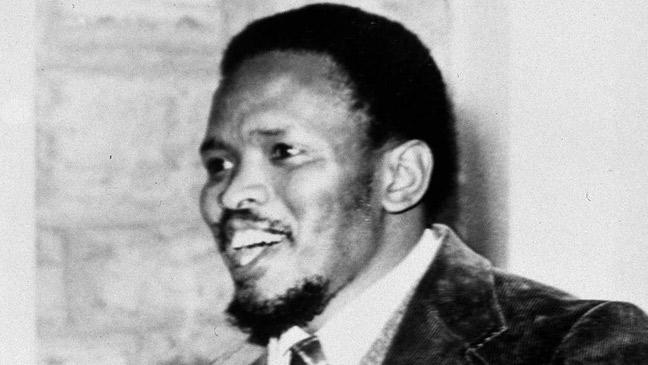

“Deep down, every liberationist is an optimist.” – Steve Biko

Steve Biko was a South African anti-apartheid activist and organizer who was murdered by the secret police in 1978. He was 32 years old when he was tortured and beaten, resulting in his death. “I Write What I Like” is a collection of writing by Biko and includes some commentary.

The collection is defined by radicalism. Biko was a believer in the mantra that freedom cannot be given, only taken. In this idea lies the core of why the liberal solution to South African apartheid remained incomplete, resulting in a highly unequal, racialized capitalist society. This is the difference between “equality” under the law and true liberation.

Biko understood that racism and apartheid were not simply technical problems. “One needs to understand the basics before setting up a remedy,” he writes. “A number of organizations now currently ‘fighting against apartheid’ are working on an oversimplified premise. They have taken a brief look at what is, and have diagnosed the problem incorrectly. They have almost completely forgotten about the side effects and have not even considered the root cause. Hence whatever is improved as a remedy will hardly cure the condition.”

Biko’s philosophy of Black Consciousness was built on undermining both the political structures that upheld apartheid as well as the internalized inferiority and superiority that still characterize race relations in many locations worldwide. He rejected integration for its own sake, recognizing that mainstream integration ideas are “white man’s integration—an integration based on exploitative values. It is an integration in which black will compete with black, using each other as rungs up a step ladder leading them to white values… these are the concepts which the Black Consciousness approach wishes to eradicate from the black man’s [sic] mind before our society is driven to chaos by irresponsible people from Coca-Cola and hamburger cultural backgrounds.”

He aimed to uphold African cultural values as important, writing “The easiness with which Africans communicate with each other is not forced by authority but is inherent in the make-up of African people… this is a manifestation of the interrelationship between man and man [sic] in the black world as opposed to the highly impersonal world in which Whitey lives.”

He understood that oppressive systems maintain their power primarily by the consent of the oppressed, which is gained via coercion, psychological tricks, propaganda, fear, and so on.

This is the reason that Biko was confident in the ability of non-violent aboveground political organizing to liberate South Africa. He was not a pacifist, and spoke in favor of the militant organizations (ANC and the PAC) that operated underground during his most active years.

These organizations had limited effectiveness in that context, but Biko strove to forge multi-generational alliances regardless, recognizing the primacy of shared goals. His approach to other groups was “tough, even aggressive language” tempered “with a basically friendly underlying spirit.”

Biko was a leader, but not an authoritarian. He promoted initiative rather than centralization. This proved to be key when many figures within various resistance movements were banned from participation in public life or sent to prison on the remote Robben Island.

He was a highly effective organizer, as one passage from his friend Aelred Stubbs C.R. makes clear. “Although Steve could hold no office in BPC because of his banning order he was constantly being consulted. It was amazing how much he knew… more than once he warned me not to get too close to certain people, white or black, whose contacts were less than desirable. He was always right. He never spoke against anyone if he could possibly help it. Even when he did, it was always in a particular context… There was this fierce integrity about them all. If you were with them you were in, and everything was given and taken. If in any way you were furthering your own ends, or trying to run with the hare and hunt with the hounds, you were out.”

Biko, like all historical figures, was no saint. His behavior was frequently sexist, and he derided feminism as an irrelevance—not an uncommon attitude at the time (or today), but inexcusable in someone fighting for justice. Like with other historical figures, we can learn from his weaknesses as well as his strength. In 2018, those lessons are still as relevant as ever.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 9, 2018 | Lobbying

Featured image: Dan From Indiana on flickr. Some Rights Reserved. The Rights of Nature Movement continues to advance through lawmaking and court decisions.

by The Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund (CELDF) via Intercontinental Cry

MERCERSBURG, PA, USA: Today, the Colombia Supreme Court of Justice issued a decision declaring that the Amazon region in Colombia possesses legal rights.

The Court declared that the “Colombian Amazon is recognized as an entity, a subject of rights” which include the right to “legal protection, preservation, maintenance and restoration.”

The Supreme Court’s decision builds on the precedent set in November 2016, when Colombia’s Constitutional Court ruled that the Atrato River possessed legal rights to “protection, conservation, maintenance, and restoration.” The Supreme Court refers to the 2016 decision in its ruling.

The Colombia Supreme Court ruling focused on the devastating impacts of deforestation and climate change on the Amazon, and the need to make significant change in how the region is protected.

In making its finding that the Amazon has rights, the Court cited the Constitutional Court’s 2016 opinion, in which that court wrote that it was “necessary to take a step forward in jurisprudence” to change the relationship of humankind with nature before “before it is too late or the damage is irreversible.”

The Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund (CELDF) – with its International Center for the Rights of Nature – has been at the forefront of the movement to secure legal rights of nature, partnering with communities, indigenous peoples, and governments in developing the world’s first Rights of Nature laws.

Transforming nature from being treated as property under the law, to be considered as rights-bearing – and thus in possession of legally enforceable rights – is the focus of the growing Rights of Nature movement.

Throughout history, women, indigenous peoples, and slaves have been treated as property under the law, without legal rights. Legal systems around the world today treat nature as property, and thus right-less. Under these systems, environmental laws regulate human use of nature, resulting in the decline of species and ecosystems worldwide, and the acceleration of climate change.

The first law was passed in Tamaqua Borough, Pennsylvania, in the United States, in 2006. Today, dozens of communities in more than 10 states in the U.S. have enacted Rights of Nature laws. CELDF assisted in drafting the first Rights of Nature constitutional provisions, which are part of the Ecuador Constitution of 2008.

Mari Margil, CELDF’s Associate Director who heads the organization’s International Center for the Rights of Nature explained, “The Court’s decision is an important step forward in moving to legal systems which protect the rights of nature.”

She added, “The collapse of ecosystems and species, as well as the acceleration of climate change, are clear indications that a fundamental change in the relationship between humankind and the natural world is necessary. We must secure the highest legal protections for nature through the recognition of rights.”

About the Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund (CELDF) & the International Center for the Rights of Nature

The Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund’s mission is to build sustainable communities by assisting people to assert their right to local self-government and the rights of nature. CELDF’s International Center for the Rights of Nature is partnering with communities and organizations in countries around the world to advance the rights of nature.

Today, CELDF is partnering with communities, indigenous peoples, and organizations across the United States, as well as in Nepal, India, Australia, and other countries to advance rights of nature legal frameworks.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 6, 2018 | Listening to the Land

Featured image: salmon eggs

Editor’s note: This is an edited transcript of Derrick Jensen’s talk, which you can view on Deep Green Video.

by Derrick Jensen / Deep Green Resistance

There are hundreds of ways to kneel and kiss the ground.

There are hundreds of ways to pray. You can walk through a forest. You can sit by a pond. You can watch the air turn into clouds and then slowly dissipate. You can lie on your back and look at the stars.

Those are crucial acts of prayer and sanity.

But with the world being killed, the prayers we really need today are actions.

We need people to not merely walk through the forest, but to defend it from being cut. And we need people to not merely look at the pond, but to make sure that those who live in the pond can survive this culture.

A prayer without actions to work toward protecting whomever you love is not a prayer. It’s not even a wish, but it’s almost a blasphemy.

I often said that I don’t hope that salmon survive, but I’ll do whatever it takes to make sure that salmon survive.

An Anishinaabe woman wrote to me and said: “I hear what you’re saying, and it is an obscenity to hope that salmon survive, or pray that salmon survive, when you’re not doing anything in the real world to help them survive. But after you have taken out the dam, you have to pray that the river accepts your offering of the dam removal, and does its own work then.”

I completely agree.

So we have to do everything that we can, and then we have to pray that the earth accepts our offering and accepts our prayer and that the salmon come home.

“Endangered Redfish Lake sockeye salmon eggs” by NOAA Fisheries West Coast is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.